ABSTRACT

The purpose of the study was to develop new knowledge about the everyday realities when implementing periodised training programmes in professional soccer Academies. Specifically, this project enhances understanding in relation to 1) those stakeholders involved in periodised training programmes in professional soccer Academies, 2) factors that facilitate and constrain the design, implementation, and monitoring of periodised programmes, 3) the extent to which practitioners perceive that education programmes adequately prepared them for this aspect of their work. Academy managers, coaches and sport science support staff were approached to complete an online survey, with 30 individuals (33.6 ± 9.5 years old) agreeing to do so. Findings highlight that practitioners “have” to adapt their practices accordingly in response to contextually constraining factors. Here, the importance of developing richer insights into the social aspects of work in applied settings, greater recognition of facilitating and constraining factors, and an improved awareness and development of the educational interventions that can prepare practitioners in applied practice is emphasised.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

A primary aim of any professional soccer Academy is to provide long-term athlete development periodised programmes that prepare youth players for the demands of competition (Unnithan et al., Citation2012; Williams & Reilly, Citation2000). Indeed, appropriate periodised training programmes should form predetermined sequential chains of targeted training periods, across a short (micro), medium (meso) and long (macro) term focus, for optimal development (Kiely, Citation2018). In England, for example, the Premier League’s Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP) has transformed the ways in which talented young players are identified, recruited, developed, and evaluated (Premier League, Citation2011). The EPPP provides a multi-disciplinary long-term player development framework in which the technical, tactical, physical, psychological and social aspects are emphasised (Premier League, Citation2011). Given the development of the modern game and increasing sporting demands, the importance of optimising the long-term development of youth soccer Academy players, in respect to the multi-faceted demands of soccer match-play, is widely recognised as being an important feature of preparing youth soccer players (Lloyd et al., Citation2016). Classified as optimum development models, Category 1 Academies receive most funding, provide up to 8500 h of coaching hours for players, a wider range of sport science support, and are licenced to recruit and develop players from 5 to 21 years of age. In contrast, Category 4 Academies are classified as late development models, receive least funding, provide fewer coaching hours, and are restricted to recruiting and developing players in the 16–21 years’ age range (Webb et al., Citation2020).

The development of youth soccer players has received considerable scholarly attention, with regards to physical, technical, and tactical development (Till et al., Citation2021; Williams & Reilly, Citation2000). Published research has resulted in evidence-based and detailed long-term athlete development programmes, which can act as a framework for those working in practice, particularly with regards to the physical development of youth athletes (Lloyd et al., Citation2016). While academic texts and educational programmes provide recommendations for designing (inclusive of macro, meso and micro cycles) as well as monitoring training, there remains limited consideration of the “doing” of these activities by practitioners in real-world youth soccer coaching environments, especially in consideration of the multi-faceted demands of soccer (Beaudoin et al., Citation2015). This would appear somewhat problematic as the design, implementation, and monitoring of periodised training programmes does not occur in a social vacuum (Pass et al., Citation2022). Rather, these processes are generated and influenced by social interactions that occur between interconnected stakeholders (e.g., Academy managers, coaches, sport scientists) in organisational and sporting subcultures, and need to be researched as such (Thomas et al., Citation2022). In the context of youth soccer Academies, practitioners are subject to more and, at times, competing demands (e.g., the educational requirements and physical development of youth athletes, alongside the usual need for injury prevention as well as technical and tactical development) from those working within the wider organisation, in which the everyday realities of these underpinning relations will impact upon the design, implementation and monitoring of a holistic youth development programme.

While research has increasingly recognised how workplace relations variously facilitate and constrain the decisions and actions of practitioners working within sports performance settings (Gibson & Groom, Citation2021; Huggan et al., Citation2015; Jones et al., Citation2004; Thompson et al., Citation2015), to date there has been limited examination of how negotiating these social relations impact upon the design, implementation, and monitoring of periodised training programmes. One notable exception is the work of Pass et al. (Citation2022) which demonstrated how the delivery of a periodised training programme in one soccer Academy deviated significantly from the original plan because of the workplace relations and constraining contextual factors. Specifically, their interview data revealed how the strength and conditioning coach faced numerous barriers when working alongside Academy coaching colleagues who constrained their preferred approach to the implementation of training (Pass et al., Citation2022). While this study certainly provided interesting initial insights, much research is needed to advance our understanding of applied practice and how key stakeholders seek to implement their expert knowledge when working as part of multi-disciplinary teams (MDT) (Thomas et al., Citation2022). Such research needs to be extended to a broader range of clubs and youth age groups, considering a more diverse range of practitioners who are directly involved with the design, implementation, and monitoring of youth development training programmes in Academy soccer. If we are to better understand how the social relations and interactions between MDTs facilitate and constrain the practice of periodisation in performance coaching environments, the views of those involved needs further consideration and exploration. Investigations should also explore in greater detail how the educational backgrounds, occupational roles and responsibilities, individual and organisational preferences, organisational hierarchies, in addition to external factors, variously impact on periodised training and its monitoring in applied settings (Thomas et al., Citation2022). Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine how practitioners perceive their workplace relations and contextual arrangements, considering how these facilitate and constrain the design, implementation, and monitoring of periodised training programmes in professional youth soccer. The development of such knowledge is of paramount importance if we are to better prepare practitioners to navigate such aspects of their work. In doing so, this study makes a significant and original contribution not only to developing an improved awareness of the social processes when designing, implementing, and monitoring periodised training in youth soccer Academies, but also extending our critical and relational understanding of sports work in a youth soccer development environment (Gibson & Groom, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Potrac & Jones, Citation2009).

Methods

Survey development & pilot testing

To develop rich insights into the social processes of designing, implementing, and monitoring periodised training programmes in professional soccer Academies, a survey, comprised of Likert scale questions, followed by open ended questions was developed. As noted by Braun et al. (Citation2021) surveys are a flexible and viable method with numerous applications and advantages for researchers and participants. Prior to distributing the final survey, the first iteration of the (pilot) survey was completed by two coaches and a sports scientist, all of which had experience of working within professional soccer Academies. Following feedback and analysis of survey responses, the clarity and terminology of questions was revised, which resulted in the development of a second iteration of the survey. The second iteration was then sent out to an additional group of practitioners, which comprised of a coach, a strength and conditioning coach and a sports scientist. Feedback and analysis of this iteration confirmed that the survey was appropriately structured and designed to address the purpose of the study, but also led to minor amendments regarding the collection of demographic information.

Within the final survey, Likert scale questions asked respondents to consider whether they strongly agreed (5), agreed (4), neutral (3), disagreed (2) or strongly disagreed (1) to specific statements. This approach provided a broad overview of respondents’ views in relation to the key areas of inquiry. After each of the Likert scale questions, open-ended questions were then asked to gain further insight and more detailed qualitative responses (i.e., “Why”). Following an initial section that focused on the demographics and experience of practitioners, questions subsequently focused on 1) how practitioners sought to interact with others when designing, implementing and monitoring periodised training programmes, 2) to what extent working with others constrained and/or facilitated their preferred approaches to designing, monitoring and implementing periodised training programmes, 3) if adjustments to periodised training programmes regularly occurred, and 4) the extent to which continuous professional development courses completed had adequately prepared them to effectively negotiate the design, implementation, and monitoring of periodised training programmes, with others, in an applied setting (see for a copy of the final survey sent to respondents). Prior to data collection ethical approval was granted by the respective University’s Departmental Research and Ethics Committee (ETH2223–0070).

Table 1. Copy of the final survey provided to respondents.

Participant recruitment & demographics

The practitioners used in the pilot testing, alongside social media platforms were used to distribute the online JISC survey, ensuring that those who worked within professional soccer Academies, as an Academy manager, coach or sport science support staff, were targeted. The survey was open for 3 months in which 30 individuals (29 male, 1 female) completed the survey. Average age of respondents was 33.6 ± 9.5 years old, with the number of years’ experience working in soccer averaging 12.7 ± 8.4 years and an average of 4.8 ± 6.9 years’ experience within their current roles. Thirteen (43.3%) respondents worked within a Category 1 soccer Academy, 9 (30%) within a Category 2 Academy, 6 (20%) within a Category 3 Academy, 1 (3.3%) a Category 4 Academy, and 1 within an Academy with no category status. Of the 30 respondents, 13 (43.3%) were Coaches, 9 (30%) were Sport Scientists, 4 (13.3%) were Strength & Conditioners, and 4 (13.3%) were Academy managers, with 29 (96.7%) stating they were on full-time contracts. In addition, 5 (16.7%) worked within the Professional Development Phase, 4 (13.3%) the Youth Development Phase, 6 (20%) worked within the Foundation Phase, and the remaining 15 (50%) working across “multiple phases” within their job role.

Data analysis

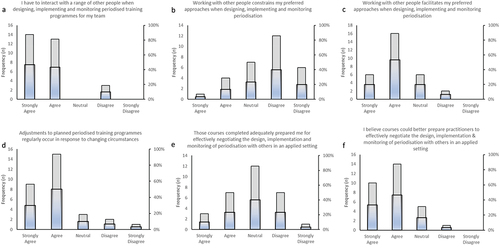

Likert scale questions from the survey were analysed using Microsoft Excel providing descriptive information regarding the frequency (and percentages) of participants' responses to these questions (). The responses to open-ended questions (i.e., qualitative data) were then thematically analysed. This thematic process comprised of deductive and inductive analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2022). Initially, questions and associated survey responses were deductively organised in relation to the following overarching themes: 1) those involved within the design, implementation and monitoring of periodised programmes, 2) how people and contextual factors facilitate and constrain the design, implementation and monitoring of periodised programmes, and 3) the education and preparation of practitioners for working in multi-disciplinary teams to design, implement and monitor periodised training programmes. This was followed by an inductive analysis of survey responses to the open-ended questions within each of the respective themes. This process entailed the application of codes to meaningful data extracts, grouping codes into overarching sub-themes, checking that sub-themes were consistently supported by participants’ responses, and reflecting upon how sub-themes might be ordered to narrate each of the overarching themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2022). Here, consideration was given towards the relationship between quantitative and qualitative survey data.

Results

Survey responses

Firstly, when asked about what aspects (Physical, Technical, Tactical and Psychological) of player development are included within their team’s periodised plan; 14 (46.6%) stated that all four aspects were considered, 10 (33.3%) said that physical, technical and tactical were included, 2 (6.6%) reported just physical, with 1 (3.3%) selecting physical, technical and psychological, 1 (3.3%) selecting technical, tactical and psychological, 1 (3.3%) selecting technical and tactical, and 1 (3.3%) selecting physical and technical.

Analysis of the qualitative survey responses resulted in the identification of three overarching themes. The first theme focused on the social and interactional nature of periodisation within an applied setting. The second theme explored how periodised training programmes can be constrained by contextual factors requiring adaptations to planned activities. The final theme highlighted a need to better prepare individuals for the applied realities of working within MDTs to design, implement and monitor periodised training programmes. Each of these will now be considered in turn.

Periodised training: Relational and negotiated process

A key finding from the survey was that practitioners’ engagement in periodisation activities at their respective clubs required respondents to work within MDTs. Indeed, 46.7% (n = 14) strongly agreed and 43.3% (n = 13) agreed that they regularly interacted with a range of significant others when enacting this part of their job. Only 3 (10.0%) respondents disagreed . Respondents highlighted the variety of specialists that are often involved in the periodisation process including, Academy managers, phase leads, age group coaches, assistant coaches and goalkeeper coaches, sport scientists, strength and conditioners, physiotherapists, medical staff, psychologists, and performance analysts. Many of the participants identified that working as part of a multi-disciplinary team was a beneficial and collaborative process, with 20.0% (n = 6) strongly agreeing and 53.3% (n = 16) agreeing that working with colleagues facilitated the implementation of preferred approaches to the design, implementation, and monitoring of periodised training programmes, whilst 20.0% (n = 6) were neutral and 6.7% (n = 2) disagreed with this statement . Those that responded positively spoke of learning from others and how the expertise of diverse staff enhanced the quality of the periodised training that players received.

Having other professionals with knowledge and understanding of periodisation and load management allows for open discussions and collaboration with the decision-making process. (Sport Scientist, Cat 2)

Collaborating and hearing varied ideas in an open-minded environment ensures new ideas can be implemented within the training programme. There are many experts in our environment and it’s important to utilise this. (Coach, Cat 1)

Working with other professionals with greater experience than myself has helped to shape my approach to not only planning but also how to speak to and deal with other members of staff and how best to pitch various ideas and programmes (Strength and Conditioner, Cat 2)

While many of the respondents identified the benefits of working in multi-disciplinary teams, a smaller number of participants shared how working with others negatively impacted on their decisions and actions. Indeed, 5 (16.6%) respondents strongly agreed or agreed that working with other staff constrained their ability to design, implement, and monitor periodised training using their preferred approaches. A further 7 (23.3%) participants responded in a neutral way, thus acknowledging that others can present barriers to their desired ways of working ).

As we work in a MDT (multi-disciplinary team) manner, and this involves multiple people, there is always compromise somewhere, the main aim is that the players get what they need, sometimes its physical, sometimes its technical/tactical. (Sport Scientist, Cat 1)

Too many cooks! It’s important to have someone set the direction and people add to that as opposed to going in a different one. (Coach, Cat 1)

Due to being relatively new into the role. I feel it is a case of trying to “drip feed” information and change into the programme to generate “buy-in” rather than trying to change too much and pushing peoples noses out of place. (Strength and Conditioner, Cat 1)

The third of the above quotations is also indicative of a wider theme that was identifiable within the participants’ responses, namely that working as part of a multi-disciplinary team to periodise training often required practitioners to negotiate and influence the ideas and practices of significant others in preferred directions. Here, participants shared numerous strategies that they utilised to shape the thinking of their colleagues.

I have found that communication is key, as is listening to coaches and other department leads. Explaining and discussing thoughts and plans is how I try to influence. (Coach, Cat 1)

Leverage existing relationships built on shared empathy and the objectives each staff member is working towards. Negotiating, looking past positions to find solutions that suit the needs of the key stakeholders where possible. However, in certain situations, compromise is not tolerated, with desirable decisions backed by objective data as support. (Sport Scientist, Cat 2)

Utilise past research documenting the demands of the game, provide insights from in house research which has been performed previously. (Strength and Conditioner, Cat 1)

Periodised training: Requires adaptation to constraining factors

Survey responses revealed how practitioners also found themselves having to adapt their periodised training programmes to accommodate unscheduled developments. 30.0% (n = 9) of the participants strongly agreed and 50.0% (n = 15) agreed that adjustments to planned periodised training programmes occurred regularly in response to changing circumstances . Practitioners identified a range of internal factors that require adaptations to be made to their originally planned periodised training programmes. These included the availability of players due to 1st team requirements, movement of squad members between age groups, loan agreements and injuries. Adjustments were also needed in response to the availability of training facilities and equipment, adverse weather conditions, and staff availability. External factors included EPPP requirements, games being added or removed from the original fixture schedule, as well as players being selected for international duties, missing sessions due to school commitments or family holidays, and working with practitioners outside of their club while playing for other teams.

Fixtures popping up out of nowhere and then having to adjust the whole cycle due to a triple game week being arranged by coaches/tournaments. Fixtures getting cancelled so we have to chase a matched physical stimulus to games, so players don’t become de-conditioned. (Sport Scientist, Cat 1)

The fluid nature of Academy soccer continues to challenge coaches to be adaptable and flexible to some plans. Often this does not have major impact on the larger scope of work we do, however it can impact micro cycles. An example of addition to the games programme may take away from a pre-planned session outcome, therefore the topic we were looking to deliver is then not. There are other minor and infrequent changes in the programme such as pitch availability, players not attending training, staff coverage etc. (Coach, Cat 1)

School commitments are a big obstacle when trying to design training programmes. Players may miss multiple sessions which means plans have to be adapted. Also, other factors such as injuries and illness can cause alterations to periodised programmes. (Strength and Conditioner, Cat 2)

Periodised training: A need for ‘real world’ formal education

Analysis of Likert scale data identified that participants held contrasting views about whether their formal professional education had equipped them for this aspect of their work. Whereas 33.3% (n = 10) of participants strongly agreed or agreed that those courses they had completed adequately prepared them to negotiate periodised planning with others in applied settings, 26.6% (n = 8) disagreed or strongly disagreed, with the largest proportion of practitioners (40.0%, n = 12) providing a neutral response ). Analysis of those qualitative comments received identified that while courses provided practitioners with underpinning knowledge about periodised training, it was through applied practice that they had acquired most of their knowledge. For some of the respondents, courses had not devoted adequate time to preparing them to work alongside other staff and learn about the dynamic realities of coaching contexts.

Courses helped underpin scientific principles and critical thinking, however, I have learnt far more during my applied setting. (Sport Scientist, Cat 2)

My coaching badges and BSc degree in Soccer Coaching have very much taken an individual focus on my own practice as a coach so the extent to which they have explicitly prepared me to collaborate with other departments is limited. (Coach, Cat 2)

I believe degree courses provide you with a good level of theoretical knowledge. However, there is not enough “real-world” programming where students can work under constraints and problem solve under pressure (Strength and Conditioner, Cat 2)

When asked to comment on whether courses could better prepare practitioners to effectively negotiate with others to design, implement, and monitor periodised training programmes, most respondents strongly agreed (33.3%, n = 10) or agreed (46.7%. n = 14) with only 5 (16.7%) participants reporting neutral and 1 (3.3%) choosing to disagree . While a range of contrasting recommendations were presented by the respondents, importance was placed on providing examples and applied experience as well as educating practitioners to work as part of an MDT and learn to respond to factors that constrain periodised training.

There needs to be more emphasis on application. More case studies need to be used. Nothing will prepare you better for working within sport than internships. Not only do you get to learn from professionals in sport science. You get to learn what soccer club culture is like how to and how not to coach/deliver. (Sport Scientist, Cat 1)

I believe that suitable universities could deliver modules encompassing students from different courses (coaching, sports science, sports therapy, sports psychology, etc.) with the intent of fostering collaboration and replicating a multi-disciplinary approach. This could take the form of a group project with students from each course working together. (Coach, Cat 2)

A more realistic overview of implementing periodised models within professional settings and an understanding of the multiple and sometimes bizarre instances which influence your ability to implement programming. Also spending time on developing the inter-personal skills which are required to negotiate discussions and social situations with coaches and other MDT members. (Strength and Conditioner, Cat 2)

Discussion

This study presents new knowledge regarding the everyday realities of periodised training within youth soccer Academies. Whereas academic texts have largely focused on how to design and monitor periodised training programmes (e.g., Bompa & Haff, Citation2009; Gamble, Citation2010), findings of the present study highlight the importance of developing richer insights into the relational aspects of such work in applied settings. It was shown that periodised training in youth soccer environments involves a range of specialists collaborating as part of wider MDTs. Operating within these teams was found to predominantly facilitate but, in some cases, constrain the periodisation of training. Periodisation seemingly requires staff to consider the ideas and approaches of various individuals, while also encouraging colleagues to take onboard their own thoughts and preferences. That is, the periodisation of training is often a negotiated, social, and relational activity (Pass et al., Citation2022; Potrac & Jones, Citation2009), which is a key aspect of practice that is often overlooked. A diverse range of factors, internal and external to their respective club contexts, were also found to constrain the respondents’ ability to implement planned activities, resulting in regular adjustments being made to their periodised training programmes.

By responding to the call of Pass et al. (Citation2022) for more reality grounded accounts of periodised training practices in applied coaching contexts, this study challenges what have tended to be overly rationalistic accounts by demonstrating that the development and implementation of periodised training is a social process influenced by the opportunities and constraints of working relations and interactions (within MDTs). This goes beyond the common approach taken in formal educational courses which tends to take a narrower focus on developing its learners’ understanding of periodisation theory and its application to sporting contexts. Indeed, current findings would suggest that an improved understanding of the everyday, social realities and dynamic processes involved in the design, implementation and monitoring of periodised training is required by (soccer) practitioners, ensuring they are able to adapt their plans and activities to changing contextual circumstances frequently experienced within practice. In doing so, this study contributes to a growing body of scholarship detailing the social realities of coaching environments and provides suggestions for future research and practice in relation to the preparation and continual professional development of those working in professional soccer Academies (Gibson & Groom, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Potrac & Jones, Citation2009; Rowley et al., Citation2020; Thompson et al., Citation2015). This would enable practitioners, to work more effectively with others as part of MDTs to design, implement and monitor periodised training programmes, for the betterment of players’ long-term development.

While the present study extends and develops our understanding of periodised training programmes in applied settings, it is hoped that the findings of this investigation will serve to prompt further scholarship into this topic of investigation. Building on the present study, future inquiry might usefully explore how social relations between specialists variously facilitate and constrain periodised training at the design, implementation, and monitoring phases, including how social status and power influence these processes (cf. Thomas et al., Citation2022). While such factors are likely to be context dependent, consideration should be given towards investigating those reasons that help to explain effective collaboration between staff as well as any resulting relationship conflicts and how these are managed and repaired (cf. Gale et al., Citation2019; cf. Gale et al., Citation2023). Scholars are also encouraged to study in greater detail how practitioners seek to influence strategically and effectively those they work with, thus encouraging preferred approaches to periodised training practices (cf. Nelson et al., Citation2022; cf.; Potrac et al., Citation2022), including, how practitioners individually and collectively adapt their periodised training programmes in response to contextually constraining factors. While the research agenda outlined here could be usefully investigated in youth soccer Academies, we believe that such analysis should also be extended to adult professional (soccer) environments and applied across a diverse range of sports. Understandably, constraining and/or facilitating factors within Academy settings may not transcend into professional adult settings (and other sports), as the surrounding contexts, personnel and wider objectives are likely to substantially differ.

The findings presented in this article also have applied implications. Many of the participants in this study believed the formal education of youth soccer practitioners could better prepare them for the social, negotiated, dynamic and contextual realities associated with the design, implementation, and monitoring of periodised training programmes in applied settings. To achieve this end, those responsible for the education of sport scientists, coaches, and strength and conditioners (among other specialists not directly studied, but mentioned by the participants in this investigation) are encouraged to consider how they might develop modules, courses, materials and assessments aimed at providing neophytes with opportunities to work within MDTs, which should include learning how to collaborate with other specialists, to design, implement, and monitor periodised training programmes aimed at optimising athlete development (Doncaster, Citation2018). In line with Doncaster (Citation2018) and previous work from Potrac et al. (Citation2016) and Potrac et al. (Citation2017) we argue for and encourage the call for an improved understanding and appreciation of not only the cognitive but the relational demands of applied work, in which there is an increased recognition of the application of social theory beyond the classroom into applied settings. Such activities should be mindful of those contextual realities that facilitate and constrain practitioners as well as encourage learners to collectively respond and adjust to those contextually constraining factors (as outlined in this paper) that they are likely to face in practice. Alongside these studies neophyte practitioners would also be encouraged to gain applied work experience where they get to experience first-hand working as part of MDTs (Doncaster, Citation2018; Dorgo, Citation2009). Information regarding the benefits (Dorgo, Citation2009) and challenges (Le Meur & Torres-Ronda, Citation2019) of working in applied settings is available, however, the way such information translates to educational learning opportunities requires further consideration. It is hoped that these types of educational interventions might help prepare practitioners to be more familiar with the everyday realities of such work when out in industry.

Conclusion

This study provides original data with regards to the everyday realities in professional soccer Academies, in which the extent to working within MDTs constrains and/or facilitates the design, implementation and monitoring of periodised training programmes. This provides novel insights into the complex social realities of periodisation, in which there is a clear acknowledgement and appreciation that practitioners 'have' to adapt their practices accordingly (i.e., negotiation and development of periodised training programmes) in response to contextually constraining factors. Whilst constraining and facilitating factors are dependent on the varying contexts, further consideration (in both research and practice) should be given towards the investigation and analysis of those reasons that help to enhance the effective collaboration between key stakeholders within youth soccer Academies. Here, future research should consider methodological approaches that seek to provide contextually rich data via the application of field observations and semi-structured interviews, thus providing a more detailed insight into the everyday realities of working in MDTS, within professional soccer Academies. Whilst the current study provides a broader (and initial) understanding which emphasises that practitioners 'have' to adapt their practices, future research should seek to adopt methodological approaches that can explore 'how' practitioners adapt their practices. Beyond this, current findings suggest that further thought and recognition should be given towards the development of (practical) educational learning opportunities that seek to prepare individuals for the practicalities of the cognitive and relational demands of applied work, in which there is an increased recognition of the application of social theory beyond the classroom into applied settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their time and efforts in the completion of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beaudoin, C., Callary, B., & Trudeau, F. (2015). Coaches’ adoption and implementation of sport Canada’s long-term athlete development model. SAGE Open, 5(3), 215824401559526. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015595269

- Bompa, T. O., & Haff, G. (2009). Periodization: Theory and methodology of training (5th ed.). Human Kinetics.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis a practical guide. Sage.

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Boulton, E., Davey, L., & McEvoy, C. (2021). The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(6), 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550

- Doncaster, G. (2018). From intern to practitioner to academic: The role of reflection in the development of a ‘sports scientist. Reflective Practice, 19(4), 543–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2018.1538951

- Dorgo, S. (2009). Unfolding the practical knowledge of an expert strength and conditioning coach. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 4(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.4.1.17

- Gale, L., Ives, B., Potrac, P., & Nelson, L. (2019). Trust and distrust in community sports work: Tales from the “shop floor”. Sociology of Sport Journal, 36(3), 244–253. ISSN 0741-1235 https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2018-0156

- Gale, L., Ives, B., Potrac, P., & Nelson, L. (2023). Repairing relationship conflict in community sport work: “offender” perspectives. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 15(3), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2022.2127861

- Gamble, P. (2010). Strength and conditioning for team sports. Routledge.

- Gibson, L., & Groom, R. (2018a). Ambiguity, manageability and the orchestration of organisational change: A case study of an English premier League Academy manager. Sports Coaching Review, 7(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2017.1317173

- Gibson, L., & Groom, R. (2018b). The micro-politics of organizational change in professional youth football: Towards an understanding of the “professional self”. Managing Sport & Leisure, 23(1–2), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2018.1497527

- Gibson, L., & Groom, R. (2021). Understanding ‘vulnerability’ and ‘political skill’ in academy middle management during organisational change in professional youth soccer. Journal of Change Management, 21(3), 358–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2020.1819860

- Huggan, R., Nelson, L., & Potrac, P. (2015). Developing micropolitical literacy in professional soccer: A performance analyst’s tale. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 7(4), 504–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2014.949832

- Jones, R., Armour, K., & Potrac, P. (2004). Sport coaching cultures: From practice to theory. Routledge.

- Kiely, J. (2018). Periodization paradigms in the 21st century: Evidence-led or tradition-driven? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 7(3), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.7.3.242

- Le Meur, Y., & Torres-Ronda, L. (2019). 10 challenges facing today’s applied sport scientist. Science Performance and Science Reports, 57, 1–7. https://sportperfsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/SPSR62_LeMeur_190328_final.pdf

- Lloyd, R. S., Cronin, J., Faigenbaum, A. D., Haff, G., Howard, R., Kraemer, L., Micheli, L., Myer, G., & Oliver, J. (2016). National strength and conditioning association position statement on long-term athletic development. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 30(6), 1491–1509. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001387

- Nelson, L., Gale, L., Potrac, P., & Ives, B. (2022). Political skill in community sport coaching work. In B. Ives (Ed.), Community sports coaching (pp. 197–209). Routledge.

- Pass, J., Nelson, L., & Doncaster, G. (2022). Real world complexities of periodization in a youth soccer academy: An explanatory sequential mixed methods approach. Journal of Sports Sciences, 40(11), 1290–1298. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2022.2080035

- Potrac, P., Hall, E., McCutcheon, M., Morgan, C., Kelly, S., Horgan, P., Edwards, C., Corsby, C., & Nichol, A. (2022). Developing politically astute soccer coaches: An evolving framework for coach learning and coaching research. In Coach education in soccer (pp. 15–28). Routledge.

- Potrac, P., & Jones, R. (2009). Micropolitical workings in semi-professional soccer coaching. Sociology of Sport Journal, 26(4), 557–577. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.26.4.557

- Potrac, P., Jones, R., Purdy, L., Nelson, L., & Marshall, P. (2016). Towards an emotional understanding of coaching: A suggested research agenda. In P. Potrac, W. Gilbert, & J. Denison (Eds.), Routledge handbook of sports coaching (pp. 235–246). Routledge.

- Potrac, P., Smith, A., & Nelson, L. (2017). Emotions in sport coaching: An introductory essay. Sports Coaching Review, 6(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2017.1375187

- Premier League. (2011). Elite player performance plan.

- Rowley, C., Potrac, P., Knowles, Z., & Nelson, L. (2020). More than meets the (Rationalistic) eye: A neophyte sport psychology practitioner’s reflections on the micropolitics of everyday life within a Rugby league academy. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 32(3), 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1491906

- Thomas, R., Hall, E., Nelson, L., & Potrac, P. (2022). Actors, interactions, ties, and networks: The ‘doing’ of talent identification and development work in elite youth football academies. Soccer & Society, 23(4–5), 420–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2022.2059870

- Thompson, A., Potrac, P., & Jones, R. (2015). ‘I found out the hard way’: Micro-political workings in professional soccer. Sport, Education and Society, 20(8), 976–994. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2013.862786

- Till, K., Eisenmann, J., Emmonds, S., Jones, B., Mitchell, T., Cowburn, I. & Lloyd, R. S. (2021). A coaching session framework to facilitate long-term athletic development. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 43(3), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000558

- Unnithan, V., White, J., Georgiou, A., Iga, J., & Drust, B. (2012). Talent identification in youth soccer. Journal of Sport Sciences, 30(15), 1719–1726. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.731515

- Webb, T., Dicks, M., Brown, D. J., & O’Gorman, J. (2020). An exploration of young professional soccer players’ perceptions of the talent development process in England. Sport Management Review, 23(3), 536–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.04.007

- Williams, A. M., & Reilly, T. (2000). Talent identification and development in soccer. Journal of Sport Sciences, 18(9), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410050120041