ABSTRACT

The period between 1980 and 2022 has seen the most radical reforms of education in England since the 1944 Education Act. This article explores those changes and their impact upon the conception and execution of pastoral care in schools. The argument is that these reforms have narrowed the thinking and practice and that what is needed now is a radical reform if we are to be able to engage with all students, enable them to learn and live in the world of today. Specific topics discussed are engagement and inclusion in school, school exclusions, behaviour policies, and mental health.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

In Citation1950 the physicist Max Planck remarked, ‘A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.’ This is definitely true for many scientific debates such as those about fat and sugar in our diets. However, I want to argue in this short paper that the same is also true of the current conception and view of the role of pastoral care in schools, which have undergone a sea change in my time in education, albeit a long one of 40 + years! The sea change may also not have been made explicit and its impact illuminated. I hope to highlight the key moments and significant changes that have occurred and end by proposing some necessary new directions.

My association with NAPCE has also been over this time of massive change. I was privileged as a young teacher, who had recently completed a Master’s degree in Pastoral Care with Douglas Hamblin, to attend the inaugural NAPCE conference chaired by Michael Marland with an organising committee of luminaries in pastoral care – Keith Blackburn, Michael Marland, Ron Best, Peter Lang and Peter Ribbins. The conference was a large one and it was full of passionate discussions about the importance of pastoral care, clear visions for its role and recent research on the topic. NAPCE was formed and became a focal point for national, international and local discussions and research about education and the nature and purpose of pastoral care.

Fast forward to 2022. I read this recent advertisement for a pastoral care post (see )

The shifts in thinking about pastoral care are embodied in many ways in this advertisement: the language used to describe the roles, the status of the post, the non-teaching nature of the post holder and the accountability to a ‘Progress’ manager. This view of the role has pastoral care in the servant role to the master of academic progress, even though the advertisement does mention personal development. It also seems to have an individualistic problem centred view of the work to be done. I want to expand on these points, chart the significant moments that brought us to this point, the consequences and therefore the challenges we now face.

Vision and values

The advertisement above stands in stark opposition to the early thinking about pastoral care. An article by Best (Citation2014) on the writings of Michael Marland demonstrates this point well . Marland was a key figure shaping early serious debates and his 1974 book Pastoral Care was a seminal piece. He saw the task of pastoral care as ‘the central task of the school (p. 10),’ indeed fundamental to comprehensive education. He warns against the danger of reducing it by seeing it ‘merely as a way of supporting the academic work of the school’ (Marland, Citation1974). He argues that educators must never lose sight of the essential unity of the ‘pastoral’ and the ‘academic’ and that the danger of splitting the pastoral and academic tasks of the school must be avoided. Best (Citation2014) summarises the position which set the framework for the next twenty years and which Marland played a key role in framing.

Pastoral care in secondary schools is about facilitating the adolescent’s search for identity in a changing world, and is therefore central to, if not co-terminate with, the school’s entire mission; that it must be planned and institutionalised in systems which begin with the needs and lives of the pupils, and which have at their core the role of the tutor, supported and facilitated by a rational structure of senior and middle-management; that it must never lose sight of the essential unity of the ‘pastoral’ and the ‘academic’, and that it has a curriculum dimension (the ‘pastoral curriculum’) without which the school’s pastoral task cannot be fully accomplished; and that at its heart is love of the child, a commitment to the well-being of the pupil and the effective functioning of the teacher. (p. 183)

My first key point is that we have reduced pastoral care to the role of servant, that the pastoral/academic split is now embedded in school processes and decision making, and that it has caused some serious problems, which I expand upon later. All the dangers Marland warned against are now accepted modes of practice and management.

This is partly a question of values, and this is not hidden. The debates about the 1988 Education Reform Act and personal, social and health education (PSHE) clearly show the battle ground of values and the war that was fought at that time.

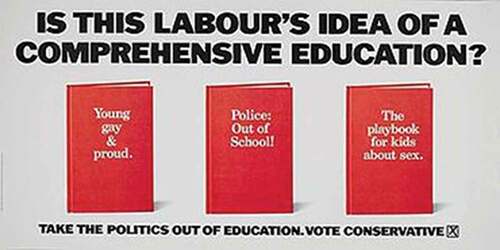

shows a very famous campaign poster designed by Saatchi and Saatchi for the 1987 general election campaign, which demonstrates the battle over values in education, as well as the politicisation of education. There had been huge social change in the twenty years prior to 1987. Marland alluded to it. The 1960s and 70s were a time of liberalisation and experimentation, described by Musgrove (Citation1974) as ‘the decline of dissent’. The New Right in British politics were intent on changing this and on taking control of education away from local authorities and giving it to the Department for Education. These battles show in the fight over two pieces of legislation: Clause 28 on the promotion of homosexuality in schools (the Guardian, Citation2022) and in the 1988 Education Reform Act, which was based on the principles of making schools more competitive, known as ‘marketisation’, and giving parents choice, known as ‘parentocracy’. A National Curriculum, standardised modes of assessment, the introduction of GCSEs and league tables were in this Act. It laid the foundations for our contemporary competitive education system.

Figure 2. Conservative Party Campaign poster for the 1987 general election (Conservative Party Archives Poster).

The Act represented a paradigm shift in British educational politics. Education Secretary Kenneth Baker destroyed the previous national political consensus based on a non- interventionist approach, embodied in the 1944 Education Act. The 1944 Act had set out a national system of education which was locally administered through local education authorities. The system had a high degree of local decision making, with professional teacher autonomy, including the control of the head teacher over the curriculum, and a liberal academic value system rooted in the almost wholly autonomous universities. (Fisher, Citation2008, p. 255)

The act was controversial then, and is now, but its central tenets have not been challenged since. It++ was probably the most significant moment in education policy in the last 60 years i.e. since the 1944 Education Act.

Washback from the 1988 Act

Washback is a technical term for the impact of tests and testing or other accountability measures on other pedagogic elements such as pedagogic methods as well as goals. (Ali & Hamid, Citation2022). I find it a useful image for looking at how the changes made in legislation and finance have had a profound impact on the practices and thinking in school. What were the key changes and what impact did they have and continue to have on pupils and the lives of schools?

Brighouse and Walters (Citation2021) have published a very comprehensive study of the years of education from 1970 to 2021 and they detail many changes in the educational climate during that time – some intended and some not. They distinguish between two clear periods of time: up to 1945–1976, ‘the first age of optimism and trust’ (Brighouse and Waters, Citation2021:13) and 1976–2021 ‘the second age of markets, centralisation and managerialism’ (Brighouse & Walters Citation2021). During this second age there was a momentous shift of the dominant values of society and in education, often referred to as ‘neo-liberalism’.Footnote1

The driving concepts of the second age, and embodied in the 1988 Education Act, were those of marketisation, choice, autonomy, and centralisation. Space does not allow for a full account of these (see, Brighouse & Walters, Citation2021) but I summarise them and then detail some of the consequences for education. There are also some clear paradoxes which arose. A marketplace in education was developed through the following measures in the act: competition among and between schools was stimulated by the publication of league tables and an increase in parental choice. The intention was also to increase the diversity of schools in the system. The impact has been increased managerialism and ironically centralisation and standardisation. Markets have shown themselves not to be self-regulating and so there is always a need for some intervention to moderate and control. This centralisation came from the Department for Education, and much is now directed from there, even if this was not the original intention. Examples of national strategies include the national literacy and numeracy strategies. give an example of the direction on data schools must publish. These tables demonstrate the extraordinarily detailed direction now being demanded and the managerialist burden imposed on schools.

Table 1. DFE guidance 2022 on what schools must publish – Headings only.

Table 2. Example of detailed guidance on exam results for key stages 2–4.

There is a strong argument for suggesting that it is the autonomy of schools that has suffered in this landscape, especially given the now extraordinary power exercised by the accountability measures devised at the same time through inspection and the publication of data. OFSTED and its framework drives practice and drives out innovation and the very diversity of practice sought by many of these earlier initiatives. This is not to imply that the use of data has not been a welcome development and useful. However, the balance has now tipped far too far into managerialism, standardisation and bureaucracy. It has had other effects which I now explore and most importantly ask, How have these changes impacted upon young people and pastoral care?

The need for radical change

There have been some excellent developments coming from recent changes. However, there is a now a need for the type of radical reform we saw in 1988 and this is due to the impact on equity, care practices, innovation and young people’s mental health. The whole nature and scope of education, especially the place of care within education, must be reimagined.

There is now strong evidence of a lack of engagement, and even attendance, of a significant group of young people in education and of a growing equity gap (Andrews et al, Citation2017). This seems to be related to policy approaches and care practices, and worsened by the Covid epidemic. There is a complicated connection between various elements at work here. These are the power of inspection and the high cost of failure, an increased emphasis on a particular approach to ‘behaviour’ and school exclusions. First, the policy framework. One of the unintended, but fairly predictable, outcomes of competition and publication of results is that some pupils become more desirable than others. Good schools are sought after and pupils who can attain well equally sought, for there are winners and losers in a market system. Places in good schools are limited and with over 75% of schools now academies, they can set their own entry criteria. There is evidence that some vulnerable and academically struggling students have become less desirable since they impact on the school’s league table position. The comprehensive ideal is thus severely diminished.

There has been a shift in tone in discussions about ‘behaviour’. Brighouse and Walters (Citation2021) chart a change in the approaches to managing behaviour in the last 30 years and comment on the shifts in tone and the increased use of ‘red lines’ and of exclusions as a tool. Policy seems to be at work. There are significant regional differences as displayed in the table below which suggest there may be practice differences that also matter.

There are also concerns about the number of pupils out of schools (Guardian, Citation2018 & Citation2022). See Early research (cf., Cooper et al., Citation2000) suggested that students from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds and with special needs are disproportionately excluded. There is a relationship to the systemic composition and practices in schools. The OECD’s Andreas Schleicher put it thus,

Exclusion is just one symptom in a system that is highly stratified. In my own country, Germany they do not have exclusions but have a highly tracked school system. It’s very easy for teachers to demote students with lower performance projections in school. If you aren’t doing very well, you are put into a vocational school. I think that sets the incentive to exasperate inequality in that society: exclusion is just the last element in the chain. (Brighouse & Walters, Citation2021, p. 376)

Table 3. Permanent exclusion rates 2018/9 in the UK.

Mental health

Since 1992 there have been increases in the incidence of mental health issues in young people. In 2015, the accepted figure for a psychiatric disorder was one in ten of 5–16 year olds, with a higher incidence of emotional and behavioural difficulties. The past 20 years from 2005 to 2015, for example, ‘has seen considerable increases in the diagnosis and treatment of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders’ (Collishaw, Citation2015:.370). This is a complex territory and Collishaw (Citation2015) posits a range of explanations for such trends, ‘including increased help-seeking by parents and young people, improved screening and clinical recognition in schools and primary care, medicalization of feelings and behaviours previously considered as normal … and a broadening of diagnostic classifications of psychiatric disorders. It is also possible that there have been real changes in the prevalence of childhood psychiatric conditions.’ (p. 370). There are connections between rates of mental ill health and physical health, issues of social equality and inequality, the social context and the national context. There was huge social change in the 1970s in the UK and this was mirrored in the rates of mental ill health.

There have also been big changes in the form, aims and practices in schooling as previously outlined. The connection between schooling and mental wellbeing or ill health is also interesting and complex. In terms of how schools relate to and engage with wellbeing and mental health there has been a further change. The medical model now dominates the field of mental health and schools. This was the situation in relation to disability twenty years ago. If we were to compare current thinking on mental health to the field of inclusion it would be the equivalent of saying that the problem is in the child and that it is dealt with on an individual remedial basis. This has been abandoned long ago for the social model of disability. The same needs to occur in education related to our thinking about mental health.There are some interesting research studies which suggest there is a relationship between the school context and wellbeing. I cite two key recent pieces of research to illustrate this. Soneson et al. (Citation2022) show that

One-third (33%) of CYP reported improved mental wellbeing during the first UK national lockdown. Compared with peers who reported no change or deterioration, a higher proportion of CYP with improved mental wellbeing reported improved relationships with friends and family, less loneliness and exclusion, reduced bullying, better management of school tasks, and more sleep and exercise during lockdown. In conclusion, a sizeable minority of CYP reported improved mental wellbeing during lockdown.

The second Danish study (Santini et al., Citation2021) concluded that

‘Our results add to a large evidence-base suggesting that mental health problems among adolescents may be prevented by promoting social connectedness at school. More specifically, fostering social connectedness at school may prevent loneliness, which in turn may promote mental well-being and prevent mental health problems during the developmental stages of adolescence. It is important to note that focusing on single indicators of school social connectedness/disconnectedness would appear to be insufficient. Implications for practices within school settings to enhance social connectedness are discussed. (p. 1)

These two substantial studies suggest that it is the environment of schooling which is not nurturing for our young people. Other studies have shown the unhappiness of our students and suggested a relationship to the high emphasis on testing and narrowing of educational aims. The 2018 PISA results (OECD, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2019c) show our young people are more unhappy than those in Europe and the rate of dissatisfaction with life has fallen fastest in the 37 countries surveyed. Space prevents a more complex discussion but there is a connection here that is worth thinking about. Marland’s assertion that ‘pastoral care in secondary schools is about facilitating the adolescent’s search for identity in a changing world, and is therefore central to, if not co- terminate with, the school’s entire mission’ (Marland, Citation1974) and his warning that losing aim this would affect education is apposite and should be heeded if we are to address young people’s care and social development in an increasingly complex personal, social and political world.

Pastoral care needs to reengage with the values debate about the purposes of education, return to a maximal rather than a minimal view of its role in schooling and develop new and innovative practices in care and curriculum that meet the needs of pupils and teachers today. There is a tidal wave of voices and evidence for change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Larner, L. (2003)’Guest Editorial’ Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 21, pp.509 − 512 for an account and view of neoliberalism.

References

- Ali, M., & Hamid, O. (2022). Teacher agency and washback: Insights from classrooms in rural Bangladesh. ELT Journal. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccac005

- Andrews, J., Robinson, D., & Hutchison, A. (2017). Closing the gap: Trends in educational attainment and disadvantage. Education Policy Unit.

- Best, R. (2014). Forty years of Pastoral care: An appraisal of Michael Marland’s seminal book and its significance for pastoral care in schools. Pastoral Care in Education, 32(3), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2014.951385

- Brighouse, T., & Walters, M. (2021). About Our Schools. Crown House Publishing.

- Collishaw, S. (2015). Annual research review: Secular trends in child and adolescent mental health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 370–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12372

- Conservative Party Archives (CPA), Bodeleian Oxford.

- Cooper, P., Drummond, M. J., Hart, S., Lovey, J., & McLaughlin, C. (2000). Positive Alternatives to Exclusion. Routledge.

- Department for Education (DFE). 2022. What maintained schools must publish. Accessed March 2, 2022 from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/what-maintained-schools-must-publish-online

- Fisher, T. (2008). The Era of Centralisation: The 1988 Education Reform Act and its consequences. FORUM, 50(2), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.2304/forum.2008.50.2.255

- Guardian. (2018). Section 28 protesters 30 years on: ‘We were arrested and put in a cell up by Big Ben. Retrieved February 22, 2022 from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/mar/27/section-28-protesters-30-years-on-we-were-arrested-and-put-in-a-cell-up-by-big-ben

- Guardian. (January 30, 2022) Up to 10,000 pupils in England missed whole autumn term last year, analysis finds. Retrieved February 23, 2022 https://www.theguardian.com/education/2022/jan/30/up-to-10000-pupils-in-england-missed-whole-autumn-term-last-year-analysis-finds

- Marland, M. (1974). Pastoral care. Heinemann.

- Musgrove, F. (1974). Generational consciousness and the decline of deference. Routledge.

- OECD. (2019a). PISA 2018 results (volume I): What students know and can do. PISA, https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en

- OECD. (2019b). PISA 2018 results (volume II): Where all students can succeed. PISA, https://doi.org/10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en

- OECD. (2019c). PISA 2018 Results (V).

- Planck, M. K. (1950). Scientific autobiography and other papers. Philosophical library.

- Santini, Z. I., Pisinger, V. S. C., Nielsen, L., Madsen, K. R., Nelausen, M. K., Koyanagi, A., Koushede, V., Roffey, S., Thygesen, L. C., & Meilstrup, C. (2021). Social disconnectedness, loneliness, and mental health among Adolescents in Danish high schools: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 15, 632906. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2021.632906

- Soneson, E., Puntis, S., Chapman, N., Mansfield, K. L., Jones, P. B., & Fazel, M. (2022). Happier during lockdown: A descriptive analysis of self‐reported wellbeing in 17,000 UK school students during Covid‐19 lockdown. In European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01934-z

- Vizard, T., Sadler, K., Ford, T., Newlove-Delgado, T., McManus, S., Marcheselli, F., Davis, J., Williams, T., Leach, C., Mandalia, D., & Cart- Wright, C. (2020). Mental health of children and young people in England. Health and Social Care Information Centre, 1–53. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/CB/C41981/mhcyp_2020_rep.pdf