ABSTRACT

Objective: This study aimed to explore which topics intended parents who opt for donor sperm treatment find relevant to discuss in psychosocial counselling.

Background: The choice for donor sperm treatment has psychosocial implications for intended parents and therefore psychosocial counselling is advised as an integral part of DST. To date, little is known about which topics intended parents find relevant to discuss in psychosocial counselling.

Methods: We conducted 25 semi-structured in-depth interviews between 2015 and 2017 with heterosexual men and women, lesbian women and single women who opted for donor sperm treatment and had a counselling session as part of their intake. They were recruited through three Dutch fertility centres, three network organisations and by snowball sampling.

Results: Intended parents found it relevant to discuss the following seven topics in psychosocial counselling: the decision to opt for donor sperm treatment, choosing a sperm donor, coping with questions from family and friends, non-genetic parenthood, single motherhood, openness and disclosure, and future contact between the child and half-siblings.

Conclusion: We recommend that counsellors take a more active role in bringing up the topics found in our study and that a clear distinction is made between counselling with the aim to screen intended parents and counselling with the aim to offer guidance.

Introduction

Parenthood is a highly widespread desire and most people have a wish to build a family at some point in their lives (Lampic, Skoog Svanberg, Karlström, & Tydén, Citation2006). Heterosexual couples who cannot conceive because of, for example, untreatable male sterility, lesbian couples and single women who wish to become parents have the option of donor sperm treatment (DST). DST has complex psychosocial implications for intended parents of all family types (Bos & van Balen, Citation2010; Hargreaves, Citation2006; Hargreaves & Daniels, Citation2007; Harrigan, Priore, Wagner, & Palka, Citation2017). In heterosexual couples, men may experience damage to their self-esteem as they do not meet the reproductive characteristics or expectations which are features of prominent masculinities, and both men and women may fear the child not being able to relate to the non-genetic parent (Cousineau & Domar, Citation2007; Indekeu, Rober, et al., Citation2013). Some lesbian couples feel anxious about whether the child will acknowledge the non-genetic mother and some worry about the challenges of raising children within a culture that is unsupportive of non-traditional families (Bos & Gartrell, Citation2010; Gartrell et al., Citation1999). Most single women express concerns about the child missing out on a male role model and that they would have preferred to raise their child within a relationship (Jadva, Badger, Morrissette, & Golombok, Citation2009; Murray & Golombok, Citation2005).

Several authorities have recommended psychosocial counselling for men and women applying for DST to help them deal with these complex psychosocial challenges (ASRM, Citation2013; HFEA, Citation2017). More specifically, the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) has recommended psychosocial counselling for all intended parents regardless of marital status or sexual orientation (ASRM, Citation2013). In the UK, it is a statutory requirement that anyone contemplating DST is offered counselling by a professional with specific expertise in fertility problems (HFEA, Citation2017). Both the ASRM and the Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority recommend that counsellors inform intended parents about the implications of DST discuss how best to talk to children about their biological origins, how to handle the child’s reaction and how to inform family and friends about donor conception (ASRM, Citation2013; HFEA, Citation2017).

These guidelines, however, are based on clinical consensus and not upon assessment of the relevance of topics to be addressed in psychosocial counselling (Visser, Gerrits, van der Veen, & Mochtar, Citation2018). In view of this, we aimed to explore which topics intended parents found relevant to discuss in counselling. We did so by in-depth interviews in which we asked which topics Dutch-intended parents had wanted to discuss and what their actual experiences were in discussing or not discussing these topics.

Method

Ethical approval

This study was part of a broader research project on psychosocial counselling of intended parents who have opted for DST. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Centre of Amsterdam affirmed that the intended parents in the broader research project would not be subjected to any risks. The METC agreed that it would be unappropriated to send invitations by email or post as the risk was too high that others would find out that the couple or woman was opting for DST. The project is registered at the Dutch Trial Register (NTR5340).

Dutch context

This study was performed in the Netherlands where intended parents in some clinics can only opt for DST with donor sperm of Dutch donors and in other clinics have the option to select an identifiable Dutch donor or an identifiable donor from an international sperm bank. Since 2004 the Dutch law states that DST is only allowed with sperm from identifiable donors which means that donor-conceived offspring are allowed to obtain identifiable information about the donor from the age of 16 and have the possibility to receive non-identifiable information from the age of 12. In the Netherlands, counsellors have various backgrounds; some are psychologists, other social workers. They have no specific education or training on DST counselling and base their counselling on their clinical experience and the policy of the clinic (Visser et al., Citation2018). Dutch clinics follow a national protocol for infertility counselling on ‘possible moral contra-indications’ during the intake which also applies for intended parents who opt for DST (NVOG, Citation2010). This protocol states that screening intended parents is essential in view of the welfare of the future child, but does not offer any guidelines on how to counsel (Visser et al., Citation2018). For additional information on the practice of Dutch counsellors, see Visser et al. (Citation2018).

Recruitment

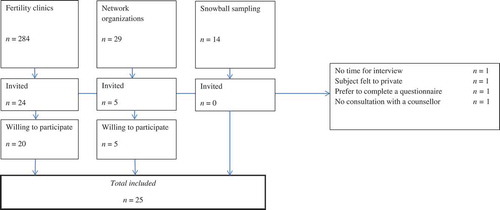

For the broader research project on psychosocial counselling of intended parents, between October 2015 and June 2017 we recruited men and women in a heterosexual relationship, women in a lesbian relationship and single women who had passed their intake procedure for DST. We recruited the intended parents through various channels. First, we handed out announcement letters and postcards in the waiting room of three fertility clinics. Second, four network organisations invited intended parents to participate in our study; two network organisations for single women posted a message in their newsletter with an announcement asking for participation in the study. An organisation for homosexual and lesbian (intended) parents spread postcards introducing the study to the visitors of their monthly meetings, and an association for men and women with fertility problems posted an announcement on their Twitter account. Third, all participating intended parents with a partner were asked whether their partner was also willing to participate (snowball sampling). Intended parents who were willing to participate contacted one of the researchers by email or telephone. All participants with a partner were asked whether we could contact him or her for invitation in the study. In total, 327 intended parents had contacted the researcher and affirmed that they were willing to participate in the broader research project. For this particular qualitative study, we used a purposive sampling method to select a subsample with an equal distribution of men and women in a heterosexual relationship, women in a lesbian relationship and single women (Etikan, Musa, & Alkassim, Citation2016). Specifically, we sought intended parents who had at least one consultation with a doctor and a counsellor at a Dutch fertility centre, who had not had a donor-child, and who were to start their first treatment with donor sperm. Twenty-nine of the 327 intended parents who were asked to participate in the qualitative study received a patient information letter and informed consent form. We informed these intended parents about the aim of the study and we explained that the interview would be audio-recorded, that identifiable information would be anonymised when spreading the results and that participants were allowed to stop participating in the study at any time without giving an explanation. We also informed them about the possibility to contact an independent counsellor – one who was not involved in the project – after the interview if they needed support. Four intended parents declined to participate: two declined because they had no time, one felt that this topic was too private to discuss face-to-face, and one woman did not have a consultation with the counsellor, so ultimately 25 intended parents were included ().

Data collection

We interviewed intended parents at their home, at the AMC Center for Reproductive Medicine, the University of Amsterdam, or by telephone or Skype, depending on their preference. The interviews were guided by a self-constructed topic list, based on clinical experience of several infertility counsellors and recent literature about support and counselling in donor sperm treatment (Crawshaw & Montuschi, Citation2013, Citation2014; Indekeu, Dierickx, et al., Citation2013; Visser, Gerrits, Kop, van der Veen, & Mochtar, Citation2016). Additional interviews were done until saturation occurred and no new information emerged. The interviews took 45–60 min and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The first author systematically analysed the interview transcripts using the constant comparative method (CCM) (Boeije, Citation2002). CCM is an iterative process of coding that makes constant comparison of the codes, both within and between the interviews, with the aim of conceptualising the content of the interviews into structured categories to develop a theory grounded in the data. We started data analysis after the first six interviews had been completed. First, the interviews were analysed by means of line-by-line coding, comparing the different segments within the interviews. Codes from subsequent interviews were continually compared with previous codes. To ensure consistency, discrepancies or disagreements were discussed until consensus was met. All analyses were performed with MaxQDA (Max Qualitative Data Analysis, version Citation2011). To help us describe the findings we have made our data ‘countable’ in places by using numbers with corresponding descriptors (Sandelowski, Citation2001), as follows: all intended parents (n = 25), almost all (n = 19–24), most (n = 13–18), a large minority (n = 9–12), some (n = 5–8) and a few (n = 1–4). We have added quotes to describe our findings; quotes followed by ♀♂ are derived from an interview with intended parents in a heterosexual relationship, quotes followed by ♀♀ are those from intended parents in a lesbian relationship, and those followed by ♀ are quotes from intended parents without a partner. The number after the quote is the number that corresponds with the participant.

Results

We achieved data saturation after 25 interviews. The characteristics of the participants are summarised in . All intended parents had one consultation with the counsellor of the fertility clinic and none of them had scheduled an additional consultation. Analysis of the transcripts revealed that the intended parents found it relevant to discuss the following seven topics in psychosocial counselling: the decision to opt for donor sperm treatment, choosing a sperm donor, coping with questions from family and friends, non-genetic parenthood (based on the interviews with heterosexual and lesbian couples), single motherhood (based on the interviews with single women), openness and disclosure, and future contact between the child and half-siblings.

Table 1. Characteristics of intended parents

The decision to opt for donor sperm treatment

Some intended parents (three♀♂, five♀♀) had wanted to talk about the implications of DST with the counsellor before they made their decision to opt for DST. Some of them (one♀♂, five♀♀) recalled discussing the difference between DST through a donor from the sperm bank as opposed to through a donor selected by themselves, because they had been in doubt about what was in the best interest of their future child. Three heterosexual men and women had wanted to reflect on the stressful period of fertility treatment and mentioned how counselling had helped them:

The consultation was helpful because it had provided new topics to discuss with my partner. (♀♂, 22)

The other (most) intended parents (seven♀♂, two♀♀, eight♀) said that the counsellor had asked about their motivation to opt for DST, but that they did not find it relevant to discuss this with the counsellor as support from others was enough:

I am blessed with many friends and family who supported me and helped me to reflect on my choices. (♀, 3)

Choosing a sperm donor

A large minority of intended parents (four♀♂, eight♀) had opted for DST in a clinic that only offered DST with Dutch donors instead of donor sperm purchased from international sperm banks. They had wanted to discuss men’s motivations to become a donor, how the clinic screened potential donors, and how the clinic matched the donors with the recipients. They felt satisfied with their discussions about this.

The other intended parents (six♀♂, seven♀♀) had to choose between a donor from a Dutch or an international sperm bank because the clinic offered both. Almost all of them had wanted to receive information about these options and they felt satisfied with the information that they had received. Nevertheless, two intended parents had wanted more support on this topic:

Yes, they [fertility clinic] use their own donors and donors from international sperm banks and there are probably differences, for example at what age the child is allowed to have contact with the donor, but she [counsellor] did not address this. It would have been more satisfying if she had addressed this in counselling so we could have made a more informed decision. (♀♀, 26)

I had asked about the chance of having a lot of half-brothers and sisters when we opt for a Danish donor. She [counsellor] said that this risk was relatively high and she told us something about the Dutch law but she could have told us that it is possible to retrieve more information from a Danish donor compared to a Dutch donor, which would have helped us make a good decision between these options. (♀♂, 25)

Coping with questions from family and friends

Most intended parents (ten♀♂, one♀♀, five♀) had wondered about how to inform friends and family about their decision to opt for DST, and some of them were afraid about negative reactions. Some intended parents (one♀♀, seven♀) felt that they had missed out on information about the experiences of other parents, while other intended parents (ten♀♂) felt satisfied:

We were doubting about who to inform about DST, but she [counsellor] said that she could not make that decision for us. So it is not a specific question with a simple answer, but talking about this with the counsellor had helped us in talking about this together. (♀♂, 19)

The other intended parents (six♀♀) did not mention this topic or (three♀) had discussed this with their own psychologist or coach and said that it had not been relevant for them to discuss it with the counsellor.

Non-genetic parenthood

A large minority of intended parents (ten♀♂, two♀♀) had wanted to discuss how it would feel to raise a child who is not genetically related to one of the parents:

What are the problems we might have to deal with? And will this child be able to bond with me? Are there any experiences of men who experience difficulties in bonding with their child? (♀♂, 14)

Among this group, some intended parents (eight♀♂) said that the counsellor had spoken about the experiences of parents and had explained the difference between nature and nurture, which was relevant for them and had reassured them. The other two couples had not received this information and felt left to their own devices:

The psychologist was interested in what was important for us, but we were just interested in what is important for the child. Well it is hard to explain, but my feeling is that she left it with us instead of taking initiative. (♀♀, 27)

The other intended parents (six♀♀) did not mention this topic.

Single motherhood

A few single women had expressed concerns about how they would practically combine raising a child with work and their financial position. They had not talked about this with the counsellor as they were afraid of being rejected for DST. On the other hand, they had discussed their concerns with friends and family:

I think that it is hard to be practically and financially responsible for 24 hours per day/ 7 days a week. Especially, when you are out of energy. But I have a good relationship with my mother and sister and I know that I can go to them when it is needed. I only decided to go for this because I know that they will always be there for me. (♀, 10)

In addition, a few single women had visited a coach specialised in coaching single women who wanted to have a child, because they felt more comfortable discussing their considerations with a coach rather than a counsellor.

Openness and disclosure

All intended parents (ten♀♂, seven♀♀, eight♀) had talked about disclosure to their future child with the counsellor but only some (four♀♂, four♀) had received tips about how and when they could tell their child that she or he is a child from a donor. The counsellor had recommended picture books to read to their child in explaining how they built their family. Most intended parents had not been given information about ways of disclosing to the child:

Of course it is important to explore our feelings about disclosure, but the perspective of the child is just as important and I have missed that. How can we deal with questions from our child and how can we name the donor? We have missed some guidance. (♀♀, 27)

It felt comforting to intended parents that all counsellors had mentioned the opportunity to come back when disclosure would become more pertinent. In addition, most intended parents had wanted to discuss their questions regarding disclosure with men and women who had become parents after DST:

There are questions which can better be answered by a parent with a donor-child. When talking about disclosure, the experiences of other parents are most important, maybe more important than how psychologists think about this. (♀♂, 25)

Future contact between the child and donor and half-siblings

A large minority of intended parents (four♀♂, five♀♀, three♀) had wanted to discuss the issue of a donor-child’s possible interest in contacting the donor and half-siblings. The single women had in particular been interested to know how many donor-children seek to contact the donor and whether donor-children are interested in making contact with half-siblings, and they took initiative in discussing this with the counsellor. One lesbian woman said that the counsellor had offered additional counselling in the future at the time when the child would be allowed to have contact with the donor, and felt satisfied about this. Some intended parents (four♀♂, four♀♀) said that this topic had not been discussed with them:

I can imagine that it is important to discuss [a child’s interest to contact the donor], but it will probably affect our feelings when our child meets the donor. How can we cope with this without giving our child the feeling that it is difficult for us? (♀♀, 27)

This topic was not mentioned by most of the intended parents.

Discussion

To gain insight into the topics or issues which intended parents find relevant to discuss in psychosocial counselling before DST, we explored the topics that they had wanted to discuss in consultations and their actual experiences with discussing these issues. In our interviews, intended parents talked about seven topics relevant for discussion in psychosocial counselling. Some had discussed their decision to opt for DST, but most found it not relevant to discuss their motivation for DST with the counsellor. Discussing the options of a Dutch donor, an international donor or an own donor was valued, but some had not been able to discuss this. Heterosexual couples and lesbian women had wanted to receive information about how parents would feel about or value non-genetic parenthood, but some felt that they had missed out on this. Single women emphasised the importance of support from friends, family and peers in preparing for single motherhood. A large minority of intended parents had wanted to discuss if donor-children would be interested in making contact with the donor, but this topic was not addressed in all consultations. With regard to disclosure, intended parents had wanted to receive practical advice and to hear the experiences of parents with a donor-child. They felt that they had not received this information as some counsellors had only explored their thoughts instead of offering advice and experiences. Moreover, some single women rather discussed difficult topics with a coach instead of a counsellor.

The strength of this study is that we performed in-depth interviews with intended parents who had a consultation with a counsellor: intended parents are the main group of people who can indicate the relevance of discussing certain topics, based upon their wishes and experiences. Another strength of this study is that we performed in-depth interviews with intended parents from all family types, extending the breadth and diversity of topics to be captured. The Dutch context on DST must be taken into account when interpreting our results. Intended parents in countries where donors are still anonymous, or where DST is surrounded by stigmatisation, might want to discuss other topics with the counsellor.

A limitation that should be noted is the small number of intended parents from each family type to participate in the qualitative study. Quantitative studies based on larger samples of subgroups are needed to gain insight into the proportions of intended parents with unmet needs for psychosocial counselling on each topic. Furthermore, it is plausible that intended parents in this study had a strong view and opinion – either positive or negative – about the counselling they had experienced and were therefore extra motivated to share their experiences with the interviewer. This might have led to selection bias and the data we obtained should be considered within this context. According to the generalisability of the study, it must be taken into account that the topics intended parents find relevant to discuss in counselling, might be shaped by the counselling they have had. In the Netherlands, counsellors had shaped their own counselling practice individually what might explain some variance in the participants experience with and views on counselling. It could be that intended parents’ experiences with counselling are different – and maybe more uniform – in countries such as Germany and the UK where psychosocial counselling is offered by counsellors who are part of a professional infertility counselling organisation for accredited counsellors specialised in gamete donation (HFEA, Citation2017; Thorn & Wischmann, Citation2013).

Our study provides insight into what counsellors actually need to address according to the intended parents themselves and shows that more topics should be discussed in psychosocial counselling than clinical guidelines currently recommend (Association Australian and New Zealand Infertility Counselling, Citation2018; ASRM, Citation2013; Crawshaw, Hunt, Monach, & Pike, Citation2013; HFEA, Citation2017). Besides ‘non-genetic parenthood’, ‘contact between the child and the donor’ and ‘openness and disclosure’ (Association Australian and New Zealand Infertility Counseling, Citation2018; Crawshaw et al., Citation2013), our results show that intended parents also prefer to discuss how they can cope with questions from family and friends, questions related to future contact with the donor and – in the case of single women – how they can cope with single motherhood. To improve counselling for intended parents, it is also relevant to take into account the needs for support of parents who already have built their family through donor conception as they might know which topics are relevant. As counsellors working in the field of donor conception are aware of issues and topics intended parents might not be aware of – such as the implications of “direct-to-consumer DNA testing” – it is also ultimately relevant to take their experiences and knowledge into account (Harper, Kennett, & Reisel, Citation2016).

Our findings show that intended parents emphasise the importance of their social network and value insight into the experiences of parents who have already had a child by donor conception. From infertile couples, it is known that social support and peer support are related to less distress and better mental health, but this relation has never been assessed in couples and single women who opt for DST (McConnell, Birkett, & Mustanski, Citation2016; Shehab et al., Citation2008). We, therefore, recommend studies on the role of social support and peer contact when improving health care for intended parents. A striking finding was that some intended parents felt that they were being screened instead of being guided, and therefore felt discouraged to address topics that were important for them. The underlying problem is probably that all counsellors follow the national protocol for infertility counselling, which stipulates that screening is recommended as part of the counselling before the actual start of treatment (NVOG, Citation2010). In light of this, it is advised that fertility clinics make a clear distinction between screening and guidance.

In view of our results, we recommend that counsellors take a more active role in bringing up the topics we found in our study, and that a clear distinction is made between counselling with the aim to screen intended parents and counselling with the aim to offer guidance.

Ethical approval

The Medical Ethics Committee of the Amsterdam UMC affirmed that the intended parents in this study would not be subjected to any risks [project number: 2015_102#B2015627].

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the fertility clinics and network organizations who contributed to the data collection. We would also like to thank all the men and women who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- ASRM. (2013). Recommendations for gamete and embryo donation: A committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility, 99(1), 47–62.

- Australian and New Zealand Infertility Counseling Association. (2018). Guidelines for professional standards of practice infertility counseling. Canberra: ANZICA.

- Boeije, H. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity, 36(4), 391–409.

- Bos, H., & Gartrell, N. (2010). Adolescents of the USA national longitudinal lesbian family study: Can family characteristics counteract the negative effects of stigmatization? Family Process, 49(4), 559–572.

- Bos, H., & van Balen, F. (2010). Children of the new reproductive technologies: Social and genetic parenthood. Patient Education and Counseling, 81(3), 429–435.

- Cousineau, T. M., & Domar, A. D. (2007). Psychological impact of infertility. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 21(2), 293–308.

- Crawshaw, M., Hunt, J., Monach, J., & Pike, S. (2013). British infertility counselling association - guidelines for good practice in infertility counselling. Third edition 2012. Human Fertility, 16(1), 73–88.

- Crawshaw, M., & Montuschi, O. (2013). Participants’ views of attending parenthood preparation workshops for those contemplating donor conception parenthood. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 31(1), 58–71.

- Crawshaw, M., & Montuschi, O. (2014). It “did what it said on the tin” - Participant’s views of the content and process of donor conception parenthood preparation workshops. Human Fertility, 17(1), 11–20.

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1.

- Gartrell, N., Banks, A., Hamilton, J., Reed, N., Bishop, H., Rodas, C., & Deck, A. (1999). The national lesbian family study: 2. interviews with mothers of toddlers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 69, 362–369.

- Hargreaves, K. (2006). Constructing families and kinship through donor insemination. Sociology of Health and Illness, 28(3), 261–283.

- Hargreaves, K., & Daniels, K. (2007). Parents dilemmas in sharing donor insemination conception stories with their children. Children and Society, 21(6), 420–431.

- Harper, J. C., Kennett, D., & Reisel, D. (2016). The end of donor anonymity: How genetic testing is likely to drive anonymous gamete donation out of business. Human Reproduction, 30 (6), 1135–1140.

- Harrigan, M. M., Priore, A., Wagner, E., & Palka, K. (2017). Preventing face loss in donor-assisted families. Journal of Family Communication, 17(3), 273–287.

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. (2017). Code of Practice (8th ed.). London: HFEA.

- Indekeu, A., Dierickx, K., Schotsmans, P., Daniels, K. R., Rober, P., & D’Hooghe, T. (2013). Factors contributing to parental decision-making in disclosing donor conception: A systematic review. Human Reproduction Update, 19(6), 714–733.

- Indekeu, A., Rober, P., Schotsmans, P., Daniels, K. R., Dierickx, K., & D’Hooghe, T. (2013). How couples’ experiences prior to the start of infertility treatment with donor gametes influence the disclosure decision. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation, 76(2), 125–132.

- Jadva, V., Badger, S., Morrissette, M., & Golombok, S. (2009). “Mom by choice, single by life”s circumstance … ’ Findings from a large scale survey of the experiences of single mothers by choice. Human Fertility, 12(4), 175–184.

- Lampic, C., Skoog Svanberg, A., Karlström, P., & Tydén, T. (2006). Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes towards parenthood among female and male academics. Human Reproduction, 21(2), 558–564.

- MAXQDA. (2011). Software for qualitative data analysis. Berlin: VERBI Software - Consult Sozialforschung GmbH.

- McConnell, E. A., Birkett, M., & Mustanski, B. (2016). Families matter: Social support and mental health trajectories among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(6), 674–680.

- Murray, C., & Golombok, S. (2005). Solo mothers and their donor insemination infants: Follow-up at age 2 years. Human Reproduction, 20(6), 1655–1660.

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecologie. (2010). Modelprotocol: Mogelijke morele contra-indicaties bij vruchtbaarheidsbehandelingen. Utrecht: NVOG.

- Sandelowski, M. (2001). Focus on research methods real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health, 24(3), 230–240.

- Shehab, D., Duff, J., Pasch, L. A., Mac Dougall, K., Scheib, J. E., & Nachtigall, R. D. (2008). How parents whose children have been conceived with donor gametes make their disclosure decision: Contexts, influences, and couple dynamics. Fertility and Sterility, 89(1), 179–187.

- Thorn, P., & Wischmann, T. (2013). German guidelines for psychosocial counselling in the area of gamete donation. Human Fertility, 12(2), 73–80.

- Visser, M., Gerrits, T., Kop, F., van der Veen, F., & Mochtar, M. (2016). Exploring parents’ feelings about counseling in donor sperm treatment. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 37(4), 156–163.

- Visser, M., Gerrits, T., van der Veen, F., & Mochtar, M. (2018). Counsellors’ practices in donor sperm treatment. Human Fertility, 1–11. doi:10.1080/14647273.2018.1449970