ABSTRACT

Background

How mother’s recall their experience of childbirth, their concerns about body image, their sense of competence in parenting, and their combined sense of self-esteem are all factors with the potential to impact on mental well-being.

Method

A total of 234 women, who had given birth within the past 3 years, completed a survey comprised of the Birth Memories and Recall Questionnaire, the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale, the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire and the Body Shape Questionnaire.

Results

Mothers who have higher body dissatisfaction show significantly lower well-being, self-esteem and perceived parenting competence. Mothers who experienced higher levels of mental well-being were found to have higher levels of perceived parenting competence and self-esteem, and those who experienced higher levels of self-esteem were also found to have higher levels of perceived parenting competence.

Conclusion

Memories of the birth experience, perceived postpartum body image, parenting sense of competence and self-esteem have a combined and complex relationship with mental well-being. Health care professionals should inform mothers about the body changes which may occur throughout the postpartum period, to encourage mothers not to be deceived by media images and to stress the importance of realistic expectations following giving birth.

Introduction

Childbirth is a life-changing experience for everyone involved and probably one of the most life-changing for the woman giving birth (Brunton et al., Citation2011; McKelvin et al., Citation2020; Nilvér et al., Citation2017). A negative birth experience can have long-term emotional and health consequences (Bell & Andersson, Citation2016). It is an experience central to a woman’s identity and some women report that they feel a loss of identity as the process into motherhood, while others find the experience just strengthens their identity as a woman (Laney et al., Citation2015). In terms of Csikszentmihalyi’s (Citation1990) concept of flow, Humenick (Citation2006) suggested that the experience can involve exhilaration and the joy of feeling in control and having a peak experience. On the other hand, for some women, it can be distressing and even traumatic (Ayers et al., Citation2016; Creedy et al., Citation2000), and the long-term impact has been linked to memories of the birth experience (Foley et al., Citation2014). These authors found that mothers with depressed symptoms scored higher on reliving emotional memories of birth.

Preparing a woman for childbirth is a big part of antenatal care given the life-changing nature of the event (Solnes Miltenburg et al., Citation2015). Yet many women do not engage with or have access to such preparatory care and there is a general myth that childbirth and motherhood come naturally to all women. Important in the process of adjustment to motherhood is a woman’s relative evaluation of herself as a mother and her confidence in her ability to care for her baby, operationally defined as parenting sense of competence (Reisz et al., Citation2015). Parental sense of competence and satisfaction are key to adjustment following birth for all first-time mothers, particularly those who are still very young (Leerkes & Crockenberg, Citation2002; Vance & Brandon, Citation2017; Yang et al., Citation2020). This sense of competence and satisfaction in parenting has been linked to well-being in mothers generally (Carlsson et al., Citation2015). The terms parenting sense of competence, parenting self-efficacy and parenting confidence are used interchangeably in the literature to describe an underlying sense of personal belief in one’s ability to be a good parent (Vance & Brandon, Citation2017). These concepts are operationally defined by the measures used to assess them and the evidence indicates that they all assess the same underlying construct and as long as this is distinguished from actual parenting competence there is no problem (Vance & Brandon, Citation2017). The current study looks at parenting sense of confidence and made no attempt to assess actual competence.

Pregnancy is a time when a woman’s figure changes shape and size rapidly in a short period of time (Clark et al., Citation2009; Sabuncuoglu & Basgul, Citation2014), and many women gain more weight during pregnancy than is recommended (Brown et al., Citation2010; Calfas & Marcus, Citation2007; Mehta et al., Citation2011; Shloim et al., Citation2014; Silveira et al., Citation2015). Media images depicting the thin-ideal has been found to be related to body image concerns for women (Grabe et al., Citation2008) as is especially problematic when non-celebrity mothers engage in social comparison with celebrity mothers through the media (Chae, Citation2014). Changes in body shape may lead to negative body image and high levels of body dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem, which can be attributed to social pressures regarding thinness (Krisjanous et al., Citation2014; Loth et al., Citation2011). One review concluded that many women have an unrealistic expectation about their body shape around and after birth, and for the majority, this leads to body dissatisfaction and lower well-being (Hodgkinson et al., Citation2014).

Self-esteem describes a person’s sense of self-worth and has been a popular construct in social science for many decades (Pyszczynski et al., Citation2004). It has been shown to be a consistent predictor of well-being (Du et al., Citation2017). There is also an extensive literature showing a consistent relationship between body image and self-esteem across all ages (Kékes Szabó, Citation2015; Lowery et al., Citation2005). One might argue that new mother’s perceived parenting competence and satisfaction would impact on their self-esteem, and there is some evidence pointing in that direction. Mother’s expectations about the transition to motherhood and expectations about the self as a mother have been linked to self-esteem (Lazarus & Rossouw, Citation2015). In another study, lack of knowledge about child rearing is related to low self-esteem as measured by levels of engagement and portrayal of self on social media in a study of Russian mothers (Djafarova & Trofimenko, Citation2017).

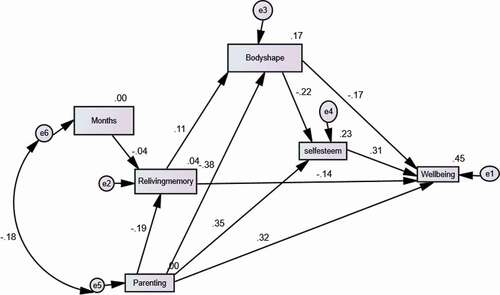

Based on the brief review above, it is argued that new mother’s experience and recall of giving birth, their sense of competence and satisfaction in parenting, their level of satisfaction with their body shape, would be linked to their self-esteem and their overall mental well-being. These relationships are hypothesised in .

This study therefore hypothesises that mothers with more positive birth experience memories, greater sense of parenting competence and greater body satisfaction might have greater self-esteem and better mental well-being.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Mothers were invited to participate in the study, via communication from the mother and baby group conveners, if they had a first child born within the previous 3 years. Mothers were provided with a link to the online survey and the sample was self-selecting. Once they opened the online survey, they were provided with an information section which they were asked to read, and this led on to a tick box consent form which they completed before proceeding to the questionnaire. A total of 234 women were recruited through contacting mother and toddler groups and children’s play centres and asking mothers to complete an online questionnaire. Inclusion criteria were that the women had their first experience of giving birth within the previous 3 years. Exclusion criteria were having currently or previously required treatment for emotional problems. G*Power 3.1 was used to calculate sample size with a power of .95 and a medium effect size resulting in an estimate of 160 participants. A minimum sample of 200 was set at the outset and recruitment eventually produce a sample of 234 participants. Potential participants were contacted via the mother and toddler groups, so the researchers had no direct contact with participants. Time since first birth experiences ranged from 6 to 24 months, and 84 had a second child since. Participants were asked to focus on the first birth experience in completing measures. The data were then used to test the model proposed in .

Measures

Demographic details concerning women’s age, number of children, months since last childbirth experience, marital status and employment status were obtained as well as responses to the following measures.

The Birth Memories and Recall Questionnaire (BirthMARQ; Foley et al., Citation2014). This questionnaire consists of 21 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale and which represented six aspects of birth memory recall (emotional memory, reliving, centrality of memory, sensory memory, involuntary recall and coherence). Emotional memory measures the valence of emotions both at the time and in remembering the birth. Reliving assesses how much the birth was re-experienced. Centrality of memory refers to how much the birth experience has been incorporated into the woman’s identity. Sensory memory taps how well the sensory experience of birth is recalled. Involuntary recall reflects experiences of recall that were unexpected and uncontrolled. Coherence reflects whether the recall is complete or fragmented. In the original study Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .74 to .84. In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .77 to .85.

The Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (PSOC; Johnston & Mash, Citation1989). This questionnaire consists of 16 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ (1) to ‘strongly disagree’ (6) with nine items measuring a satisfaction dimension (Cronbach’s alpha = .75) and seven items measuring an efficacy dimension (Cronbach’s alpha = .76). The overall scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .79. Higher scores reflect higher perceived parenting sense of competency. In the current study, the satisfaction scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .84, and the efficacy scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .82. The overall scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .88.

The Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS; Stewart-Brown & Janmohamed, Citation2008). The scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .91 in the original study. This questionnaire consists of 14 items which were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘none of the time’ (1) to ‘all of the time’ (5). The questionnaire is scored by summing the score for each of the 14 items. Scores range from 14 to 70 (Putz et al., Citation2012). The scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of .82 in the current data.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire (RSEQ; Rosenberg, Citation1965). This questionnaire consists of 10 items. Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale and five items were positively scored (items 1, 2, 4, 6 and 7) from 3 (strongly agree) to 0 (strongly disagree and five items were reverse scored (items 3, 5, 8, 9 and 10) from 0 (strongly agree) to 3 (strongly disagree). The scoring scale ranges from 0 to 30 and scores between 15 and 25 are within normal range, scores below 15 indicate low self-esteem. The measure has achieved Cronbach’s alphas between .77 and .82 in a range of studies (Rosenberg, Citation1986). In the current data, the scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of .85.

Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ-8d) (Pook et al., Citation2008). This questionnaire consists of 8 questions rated on a 6-point Likert scale (with ‘never’ being 1 and ‘always’ being 6). The scoring scale ranges from 6 to 48 and a higher score indicates higher levels of body shape satisfaction. This scale was chosen because it provides a short-form assessment of how satisfied or dissatisfied an individual has been with their body shape. Participants were asked to focus on how they felt in the weeks following the first birth. There are more complex measures of body image, but the current study required a simple measure to assess if satisfaction/dissatisfaction with body image was related to mental well-being. Pook et al. (Citation2008) reviewed several versions of the measure and concluded that the 8-item version was comparable to other versions and had a Cronbach’s alpha of .90. In the current data the scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .92.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained via the University Ethics Committee and permission sought and given by the convenors of Mother and Baby groups to distribute information about the study.

Analysis

Data were downloaded to SPSS and cleaned for analysis. SPSS25 with AMOS 25 was used to carry out all analysis. Initially, descriptive statistics and correlations were calculated to describe the data. The main analysis used Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis (HMRA) and Path Analysis with AMOS 25 to test the hypothetical model. The first HMRA explored the predictors of well-being using the enter method and with independent variables entered in separate steps as shown in . The second HMRA used the same procedure to explore the predictors of self-esteem as shown in . This analysis provided initial support for the model proposed in . Path analysis using the Structural Equation Modelling approach in AMOS 25 was then applied to test the full model.

Table 1. Profile characteristics.

Table 2. Summary table of all descriptive statistics and correlations.

Table 3. HMRA to identify the predictors of well-being.

Table 4. HMRA to identify the predictors of self-esteem.

Results

Sample

A total of 234 mothers (N = 234) completed the questionnaire. Ages ranged from 22 to 40 years with the majority of women in their thirties (60%) with a mean age of 31 years (SD = 4.47). Most were married (78%), in part-time employment (40%) and had two children (44%). Participant’s profile characteristics can be found in .

Descriptive statistics

The first stage in analysis was to calculate descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) and Pearsonbivariate correlationsfor the variables measured. See .

Body dissatisfaction was found to have a statistically significant inverse relationship with total perceived parent competence (r = −.38, p < .001), parent satisfaction (r = −.32, p < .01), parent efficacy (r = −.38, p < .001), mental well-being (r = −.44, p < .001) and self-esteem (r = −.36, p < .001). The data show that the mothers in this study who had higher levels of body dissatisfaction had lower perceived parenting competence, satisfaction and efficacy, lower mental well-being and lower self-esteem.

Mental well-being was found to have a strong statistically significant positive relationship with total perceived parent competence (r = .52, p < .001), parent satisfaction (r = .46, p < .001), parent efficacy (r = .52, p < .001) and self-esteem (r = .52, p < .001). Mothers who experienced higher levels of mental well-being were also found to have higher levels of perceived parenting competence (in both satisfaction and efficacy categories) and self-esteem. Self-esteem was found to have statistically significant correlations with well-being (r = .52, p < .001), perceived parent competence (r = .41, p < .001) and parent efficacy (r = .50, p < .001). Mothers who experienced higher levels of self-esteem were also found to have higher levels of perceived parenting competence (in both satisfaction and efficacy categories) and well-being.

Emotional memory was found to have weak statistically significant inverse relationship with mental well-being (r = −.23, p < .05), coherence memory (r = −.40, p < .001) and age (r = −.31, p < .01) indicating that younger mothers had higher negative emotions, had lower mental well-being and lower coherent memories of the birth. It should also be noted that emotional memory was found to have an inverse relationship, though not statistically significant, with self-esteem (r = −.11, p = .33), perceived parent competence (r = −.11, p = .34), parent satisfaction (r = −.12, p = .28) and parent efficacy (r = −.14, p = .24).

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to identify the predictors of levels of well-being (see ). Preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity and homoscedasticity. Months, number of children, marital status, employment status, and age were entered at step 1, explaining 3% of the variance in well-being, though not significant (F (5, 228) = 1.54, p = .189). After entry of recall memory, centrality of memory, coherence memory, reliving memory, emotional memory and sensory memory at step 2 (and controlling for months, number of children and age), the additional variance explained by the model was 18%, (F (6, 222) = 8.55, p < .001). After entry of perceived parent competence at step 3 (and controlling for recall memory, centrality of memory, coherence memory, reliving memory, emotional memory, sensory memory, months, number of children and age), the additional variance explained by the model was 21%, F = (3, 219) = 25.74, p < .001. After entry of body dissatisfaction at step 3 (and controlling for recall memory, centrality of memory, coherence memory, reliving memory, emotional memory, sensory memory, perceived parent competence, months, number of children and age), the additional variance explained by the model was 4%, (F = (1, 218) = 18.06, p < .001). Self-esteem was entered on step 5 and explained an additional 5% of the variance (F = (1, 217) = 22.33, p < .001). The final model explained 48% of the variance in well-being.

Hierarchical multiple regression was repeated, this time with self-esteem as the dependent variable (see ). Months, number of children, marital status, employment status, and age were entered at step 1, explaining 3% of the variance in well-being, though not significant (F (5, 228) = 1.39, p = .231). After entry of recall memory, centrality of memory, coherence memory, reliving memory, emotional memory and sensory memory at step 2 (and controlling for months, number of children and age), the additional variance explained by the model was 10%, (F (6, 222) = 3.99, p < .001). After entry of perceived parent competence at step 3 (and controlling for recall memory, centrality of memory, coherence memory, reliving memory, emotional memory, sensory memory, months, number of children and age), the additional variance explained by the model was 21%, F = (3, 219) = 23.49, p < .001. After entry of body dissatisfaction at step 4 (and controlling for recall memory, centrality of memory, coherence memory, reliving memory, emotional memory, sensory memory, perceived parent competence, months, number of children and age), the additional variance explained by the model was 3%, (F = (1, 218) = 11.97, p < .001). The final model explained 33% of the variance in well-being.

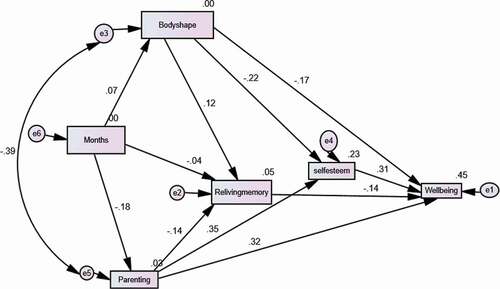

Based on the results above we tested the hypothesised path model of the relationships as shown in using AMOS software on SPSS. The model shown is a good fit for the data (χ2 (4) = 0.490, p = .97, CMin/DF = 0.123, IFI = 1.0, CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = .01, PClose = .99).

This was cross-sectional data, so direction of causality cannot be determined. Hence, a second possible model in which reliving birth experience was repositioned as a consequence of body image and perceived parenting competence. This model is also a good fit for the data (χ2 (3) = 0.488, p = .92, CMin/DF = 0.163, IFI = .99, CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = .01, PClose = .96).

Discussion

The current investigation sought to expand understanding of the relationship between birth memories, perceived parenting competence, body satisfaction, self-esteem and mental well-being, of new mothers with children aged under 2 years. Based on a brief literature review a model () was developed and tested. The model was supported by the data, and an overall perspective shows that reliving memories of the birth, poorer body satisfaction and lower levels of perceived parenting competence were directly related to poorer well-being. More satisfaction with body shape and more perceived competence in parenting were related to more self-esteem. Self-esteem was positively related to well-being supporting a range of previous research (Du et al., Citation2017). As this is cross-sectional data we can only talk about relationships and not causality. The data also support an alternative path model confirming the relationships discussed aboveearlier but raising the possibility that body satisfaction and sense of parenting competence might influence reliving of birth memories rather than the other way around. It seems likely that reciprocal relations of causality exist between parenting sense of competence, body satisfaction and birth memories. However, whatever the direction of causality it seems reasonable to argue that these variables are precursors of self-esteem and well-being. This is supported by previous research which has found that birth memories are linked to well-being (Foley et al., Citation2014), body dissatisfaction is linked to lower well-being and self-esteem (Hodgkinson et al., Citation2014; Krisjanous et al., Citation2014), and parenting sense of competence is linked to positive well-being (Vance & Brandon, Citation2017; Yang et al., Citation2020). In turn, self-esteem is clearly linked to well-being (Du et al., Citation2017).

Based on the partial correlations, mothers who reported reliving birth memories and where memories were negative emotionally and who had lower body satisfaction reported poorer well-being. On the other hand, mothers where birth memories were central, who were more satisfied and had more self-efficacy in parenting, and who had higher self-esteem reported better well-being. Mothers who had less recall of memory, who had higher parenting self-efficacy and who had less body dissatisfaction had higher levels of self-esteem. Path analysis shows that the important memory factor in well-being is reliving the negative memories which confirms the findings from the only other study to look at this (Foley et al., Citation2014). Body satisfaction seems to play a central role in mediating the impact of relived memory and parenting satisfaction on both self-esteem and well-being. The only background variable that played a role in the path model were months since birth and the size of relationship was quite small. In essence, it seems that reliving memories reduces with time since birth as does body dissatisfaction, while self-esteem and well-being increase. Parenting satisfaction seems to have a positive relationship with self-esteem and well-being and is negatively indicated for body satisfaction.

These findings are consistent with previous studies in terms of body dissatisfaction and lower well-being and reduced self-esteem (Clark et al., Citation2009; Silveira et al., Citation2015). Similarly, the link between parenting sense of competence and positive self-esteem (Reisz et al., Citation2015) indicates that high maternal self-esteem can have a positive mediating impact on well-being during early interactions with the baby (Leerkes & Crockenberg, Citation2002). Previous research has stressed that mental well-being should be an explicit objective within parenting programmes and strategies in order to boost parenting sense of competence and confidence and the mental well-being of both the parent and child (Nilvér et al., Citation2017).

The novel finding from this study was the link between birth memories, self-esteem and well-being. In particular, the role of relived birth memories, which supports the findings of Foley et al. (Citation2014). This could have importance for mothers who have a negative birth experience and could indicate the potential development of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

This was a cross-sectional study using questionnaires with the limitations associated with such studies. Mothers were asked to focus on recalling their first birth experience and of course there are always issues with memory recall over time. However, what the mothers reported was important to them and did correlate with their reported well-being. This does also corroborate some previous research. One might argue that whether the recalled memories were an accurate record the fact that the experience was recalled is what is currently important to the mothers. Qualitative exploration would enhance this area of research and in hindsight other measures (such as social support and BMI) could have been used and some biomarkers recorded.

Despite limitations, the current study allows some recommendations for both research and practice. In terms of research, the obvious advances would be to carry out longitudinal analyses and add a qualitative element. More direct measures of BMI, changes in weight and actual effectiveness as a parent would be useful.

In terms of recommendations for practice, the results of this study would indicate that mothers would benefit from receiving support from health care professionals early in the postpartum stages, especially for mothers reluctant to seek help. Interventions to enable expectant mothers to develop realistic expectations about the transition to motherhood and the changes in identity that would be encountered would be indicated. A focus on the extent to which the birth experience is embedded in memory, particularly if it were a negative experience, could indicate specific types of intervention. Reducing postpartum weight could have important benefits for long-term health. The risk of obesity becomes most problematic for women during the childbearing years, and research shows that that weight at 1-year postpartum strongly predicted whether an individual was overweight a decade or more later (Brown et al., Citation2010; Calfas & Marcus, Citation2007).

In conclusion, mental well-being, self-esteem and body satisfaction appear to be interlinking components which fluidly connect to one another and which can be affected by many of the life events and bodily changes which take place in the postpartum period such as recovery from the birth, learning new skills in parenting and dealing with a new identity as a mother. This study would propose that health care professionals in contact with mothers should offer advice about the realistic body changes which may occur throughout the postpartum period and should also encourage mothers not to be deceived by media images. Mothers should also be advised on the benefits of physical activity in terms of both physical and mental health. It would also be helpful to encourage women to seek professional help from their health visitor or GP if they feel their mental well-being or self-esteem has deteriorated greatly.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ayers, S., Bond, R., Bertuilles, S., & Wijma, K. (2016). The aetiology of post-traumatic stress following childbirth: A meta-analysis and theoretical framework. Psychological Medicine, 46(6), 1121–1134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002706

- Bell, A. F., & Andersson, E. (2016). The birth experience and women’s postnatal depression: A systematic review. Midwifery, 39, 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.04.014

- Brown, W. J., Hockey, R., & Dobson, A. J. (2010). Effects of having a baby on weight gain. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38(2), 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.044

- Brunton, G., Wiggins, M., & Oakley, A. 2011. Becoming a mother: A research synthesis of women’s views on the experience of first-time motherhood. EPPI Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

- Calfas, K. J., & Marcus, B. H. (2007). Postpartum weight retention: A mother’s weight to bear? American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(4), 356–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.008

- Carlsson, I.-M., Ziegert, K., & Nissen, E. (2015). The relationship between child birth self-efficacy and aspects of well-being, birth interventions and birth outcomes. Midwifery, 31(10), 1000–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.05.005

- Chae, J. (2014). Interest in celebrities’ post-baby bodies and Korean women’s body image disturbance after childbirth. Sex Roles, 71(11–12), 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0421-5

- Clark, A., Skouteris, H., Wertheim, E. H., Paxton, S. J., & Milgrom, J. (2009). My baby body: A qualitative insight into women’s body-related experiences and mood during pregnancy and the postpartum. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 27(4), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830903190904

- Creedy, D. K., Shochet, I., & Horsfall, J. (2000). Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: Incidence and contributing factors. Birth, 27(2), 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00104.x

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

- Djafarova, E., & Trofimenko, O. (2017). Exploring the relationships between self-presentation and self-esteem of mothers in social media in Russia. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.021

- Du, H., King, R. B., & Chi, P. (2017). Self-esteem and subjective well-being revisited: The roles of personal, relational, and collective self-esteem. PLoS ONE, 12(8), e0183958. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183958

- Foley, S., Crawley, R., Wilkie, S., & Ayers, S. (2014). The birth memories and recall questionnaire (BirthMARQ): Development and evaluation. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, 211. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-211

- Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 460–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460

- Hodgkinson, E. L., Smith, D. M., & Wittkowski, A. (2014). Women’s experiences of their pregnancy and postpartum body image: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1), 330. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-330

- Humenick, S. (2006). The life changing significance of normal birth. Journal of Perinatal Education, 15(4), 1–3.

- Johnston, C., & Mash, E. J. (1989). A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp1802_8

- Kékes Szabó, M. (2015). The relationship between body image and self-esteem. European Psychiatry, 30(1), 1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(15)32029-0

- Krisjanous, J., Richard, J. E., & Gazley, A. (2014). The perfect little bump: Does the media portrayal of pregnant celebrities influence prenatal attachment? Psychology & Marketing, 31(9), 758–773. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20732

- Laney, E. K., Hall, M. E. L., Anderson, T. L., & Willingham, M. M. (2015). Becoming a mother: The influence of motherhood on women’s identity development. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 15(2), 126–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2015.1023440

- Lazarus, K., & Rossouw, P. J. (2015). Mother’s expectations of parenthood: The impact of prenatal expectations on self-esteem, depression, anxiety, and stress post birth. International Journal of Neuropsychotherapy, 3(2), 102–123. https://doi.org/10.12744/ijnpt.2015.0102-0123

- Leerkes, E. M., & Crockenberg, S. C. (2002). The development of maternal self-efficacy and its impact on maternal behaviour. Infancy, 3(2), 227–247. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327078IN0302_7

- Loth, K. A., Bauer, K. W., Wall, M., Berge, J., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2011). Body satisfaction during pregnancy. Body Image, 8(3), 297–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.03.002

- Lowery, S. E., Robinson Kurpius, S. E., Befort, C., Hull Blanks, E., Sollenberger, S., Foley Nicpon, M., & Huser, L. (2005). Body image, self-esteem, and health-related behaviors among male and female first year college students. Journal of College Student Development, 46(6), 612–623. Project MUSE. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2005.0062

- McKelvin, G., Thomson, G., & Downe, S. (2020). The childbirth experience: A systematic review of predictors and outcomes. Women and Birth. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.021

- Mehta, U. J., Siega-Riz, A. M., & Herring, A. H. (2011). Effect of body image on pregnancy weight gain. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(3), 324–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0578-7

- Nilvér, H., Begley, C., & Berg, M. (2017). Measuring women’s childbirth experiences: A systematic review for identification and analysis of validated instruments. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 17, 203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1356-y

- Pook, M., Tuschen-Caffier, B., & Brähler, E. (2008). Evaluation and comparison of different versions of the body shape questionnaire. Psychiatry Research, 158(1), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2006.08.002

- Putz, R., O’Hara, K., Taggart, F., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2012). Using WEMWBS to measure the impact of your work on mental well-being: A practice-based user guide: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/med/research/platform/wemwbs/researchers/userguide/wemwem_practice_based_user_guide.pdf

- Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Arndt, J., & Schimel, J. (2004). Why do people need self-esteem: A theoretical and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 435–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.435

- Reisz, S., Jacobvitz, D., & George, C. (2015). Birth and motherhood: Childbirth experience and mothers’ perceptions of themselves and their babies. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21500

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton University Press.

- Rosenberg, M. (1986). Self-concept from middle childhood through adolescence. In J. Suls & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 3, pp. 107–135). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Sabuncuoglu, O., & Basgul, A. (2014). Pregnancy health problems and low birth weight associated with maternal insecure attachment style. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(6), 934–943. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314542819

- Shloim, N., Rudolf, M., Feltbower, R., & Hetherington, M. (2014). Adjusting to motherhood. The importance of BMI in predicting maternal well-being, eating behaviour and feeding practice within a cross cultural setting. Appetite, 81, 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.06.011

- Silveira, M. L., Ertel, K. A., Dole, N., & Chasan-Taber, L. (2015). The role of body image in prenatal and postpartum depression: A critical review of the literature. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 81(3), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-015-0525-0

- Solnes Miltenburg, A., Roggeveen, Y., Shields, L., Van Elteren, M., Van Roosmalen, J., Stekelenburg, J., & Portela, A. (2015). Impact of birth preparedness and complication readiness interventions on birth with a skilled attendant: A systematic review. Plos One, 10(11), e0143382. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143382

- Stewart-Brown, S., & Janmohamed, K. (2008). Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS) User Guide Version 1. http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/7551-WEMWBS%20User%20Guide%20Version%201%20June%202008.pdf

- Vance, A. J., & Brandon, D. H. (2017). Delineating among parenting confidence, parenting self-efficacy, and competence. Advances in Nursing Science;, 40(4), E18–E37. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000179

- Yang, X., Ke, S., & Gao, -L.-L. (2020). Social support, parental role competence and satisfaction among Chinese mothers and fathers in the early postpartum period: A cross-sectional study. Women and Birth, 33(3), e280–e285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2019.06.009