Abstract

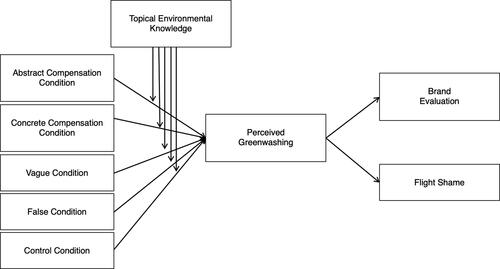

Drawing on information process theories, this study investigated whether consumers have the ability to perceive greenwashing in vague and false greenwashing claims, as well as in abstract and concrete compensation greenwashing claims. Moreover, we examined the moderating role of topical environmental knowledge. We also looked at the effects of perceived greenwashing on brand evaluation and flight shame. Findings of an experimental study with a quota-based sample (N = 658) indicate that only concrete compensation claims do not significantly enhance greenwashing perceptions. However, when consumers have a high topical environmental knowledge, they are able to discover greenwashing in concrete compensation claims as well. Once greenwashing perceptions are triggered, they harm brand evaluations and foster flight shame. Implications for research on greenwashing and conclusions for practitioners are discussed.

As one of the leading figures, the Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg is stressing the moral responsibility of each individual to approach climate change. Especially, she empathizes the need to restrain from air travel as an individuals’ moral duty (Gössling, Humpe, and Bausch Citation2020). However, consumers may see part of this responsibility also on the side of big companies. Especially companies offering environmentally inherently unfriendly products or services like airlines have noticed the normative pressure in society, and as a consequence, they have reacted with green advertising (Mayer, Ryley, and Gillingwater Citation2014). Among various companies offering green products or services, the airline sector represents a special case for advertising due to the ‘flyers’ dilemma’ (Young, Higham, and Reis Citation2014). Although consumers are becoming more environmentally conscious, flying still remains very desirable (Hibbert et al. Citation2013). Green airline advertising alludes directly to the dilemma by suggesting that it can be solved.

At the same time, misleading green advertising strategies, so called greenwashing strategies, are increasingly used by airline companies (e.g., Naderer, Schmuck, and Matthes Citation2017), for instance, when communicating their pro-environmental performance while camouflaging the harmful environmental character of flying (De Freitas Netto et al. Citation2020). Generally, greenwashing may prevent social change in society that is needed to avert the environmental crisis (Kilbourne et al. Citation1995). Although consumers are willing to turn to more environmentally friendly consumption behaviors, they have difficulties to identify sustainable products or services because of unclear information (BEUC Citation2020). Hence, greenwashing could impede true green consumerism (Carlson et al. Citation1996, 57).

Knowledge about the effects of greenwashing in advertising is limited (Matthes Citation2019; Naderer, Schmuck, and Matthes Citation2017). Previous research has shown that consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing vary depending on the advertising claim as well as on consumers’ environmental knowledge (e.g., Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015; Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). So far, studies have only examined false claims, vague claims, and executional greenwashing (e.g., Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). Recently, an increasing number of airlines use omission claims. This is done by advertising green compensation measures for flying leaving out important information that is needed for consumers to ‘evaluate its truthfulness or reasonableness’ of the compensation (Kangun, Carlson, and Grove Citation1991, 51). Compensation claims could be very persuasive as they may evoke or confirm consumers’ compensatory green beliefs (Hope et al. Citation2018). As a consequence, such claims may confuse consumers as to whether the offered measures can actually compensate for flying (Polonsky, Grau, and Garma Citation2010, 51).

There are three key research gaps. First, research on compensation claims in the greenwashing context has been neglected so far (Matthes Citation2019). Second, we generally lack experimental research on greenwashing when it comes to inherently environmentally harmful products and services such as airlines. Third, emotions caused by perceived greenwashing have been largely ignored until now (Koenig-Lewis et al. Citation2014; but see Szabo and Webster Citation2021). Thus, in this paper, we experimentally examine consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing in response to vague and false greenwashing claims, as well as in abstract and concrete compensation claims. Moreover, we look at the moderating role of topical environmental knowledge.

Green advertising and greenwashing claims

Greenwashing is defined as a process in which companies stress the environmental friendliness of a service or product, while withholding environmentally unfriendly aspects (e.g., Naderer, Schmuck, and Matthes Citation2017). While some content analyses have shown that the majority of companies’ green claims contain greenwashing elements (Carlson et al. Citation1996; Carlson, Grove, and Kangun Citation1993; Kangun, Carlson, and Grove Citation1991), others have reported that only less of the half of green ads in magazines and newspapers can be categorized as greenwashing (e.g., Segev, Fernandes, and Hong Citation2016). However, there is agreement that greenwashing is not uncommon.

According to Carlson, Grove, and Kangun (Citation1993) there are five types of green ads: (1) product, (2) process, (3) image, (4) environmental fact, and a (5) combination. A content analysis showed that claims endorsing a green image of the company were the most used claims followed by claims promoting green attributes of a product or service. Regarding claim deceptiveness, Kangun, Carlson, and Grove (Citation1991) distinguished (1) acceptable claims, (2) vague claims, (3) false claims, (4) claims possessing omissions, and (5) a combination of these claims. Acceptable claims represent substantial advertising messages which are true, do not mislead, and do not deceive. Vague claims are perceived as overly ambiguous and as too unspecific in order to make a well-informed conclusion about the green character of a product or service. Whereas false claims include an outright lie, claims possessing omissions are defined as claims that exclude important information that is needed by consumers to draw conclusions about the ‘truthfulness or reasonableness’ of the claim (Carlson, Grove, and Kangun Citation1993, 31).

As green airline advertising focuses simultaneously on both, environmentally friendly attributes of the service of flying and an eco-image of the airline, a combination of product and image claims is investigated in this study (e.g., Carlson, Grove, and Kangun Citation1993). Regarding deceptiveness, vague claims promoting flying as a way to protect the planet (e.g., VietJet Citation2020), and as ‘the greenest flight’ (e.g., Frontier Airlines Citation2019) without giving a reason or proposing measures are often used in airline advertising (Carlson, Grove, and Kangun Citation1993, 31). Further, claims promoting an airline as the company with the lowest carbon emissions, when in reality, this is not correct, or offering a full elimination of flight emissions when flying with the promoted airline, are common examples for false claims (e.g., Ryan Air Citation2020). Lastly, omission claims promoting environmental protection measures as compensation for the environmentally harmful services they are offering are increasingly used by airlines (e.g., Air New Zealand Citation2019). In this paper, we refer to these claims as compensation claims (Polonsky, Garma, and Grau Citation2011). Typically, compensation claims are signaling consumers that the CO2 produced by flying can be compensated by other environmentally friendly measures. However, information about how much carbon one flight produce and how much carbon can be compensated with the promoted measures is not disclosed in these ads. Moreover, information about what the carbon compensation measures cover is often omitted. As a consequence, it is difficult for consumers to make a responsible consumption decision (e.g., Polonsky, Grau, and Garma Citation2010).

In contrast to vague claims, compensation claims are proposing environmental measures and thus, give reason for airlines to claim to be environmentally friendly. Further, whereas false claims present wrong knowledge such as ouright lies, compensation claims are not per se wrong or outright lies. Instead, they omit important information that is needed for consumers to see the true environmental benefit. To sum it up, compensation claims are neither vague, nor false, rather they are contextualized as omission claims (see Appendix A, ).

Derived from the green airline advertising practice, we distinguish between abstract and concrete compensation claims. Abstract compensation claims are proposing future environmental compensation for the environmental impact of flying, without consumers being able to directly observe the trade-off. For instance, various airlines (e.g., Air New Zealand Citation2019) offer to invest in tree planting, environmental projects, or environmental research. As the compensation measure is not observable directly on board, but in the future, there exists only an abstract and non-verifiable evidence for the green compensation. Concrete compensation claims are promoting an immediate compensation for the environmental impact of flying. The compensation measure can be directly experienced by consumers and ‘seen’ while using the product or service. Various airlines (e.g., HiFly 2019) state that they are fully plastic free on board or that they recycle all of the used cutlery on bord by recollecting it. This is an observable and verifiable evidence of green compensation, clearly visible to consumers.

Although these claims may be literally true, they could imply a false impression of the possibility of overall sustainable flying and could be easily misunderstood by consumers (Majoras Citation2008). Compensation claims may not only lead to consumers’ overestimation of an environmental benefit, they also neglect important information. They solely focus on the ecological benefits of flying and thus, may distract consumers from the negative environmental consequences. Therefore, they can be categorized as omission claims and thus, as potentially greenwashing (Majoras Citation2008; Polonsky, Grau, and Garma Citation2010).

Additionally, Kangun, Carlson, and Grove (Citation1991) showed that there is also a combination of deceptive claims. Transferred to the flight context, this would mean that airlines make statements that consist of various deceptive elements (e.g., KLM Citation2019). Finally, image-based emotional appeals, such as pleasant nature imagery, are used to create an environmentally friendly image. This strategy is called executional greenwashing and is widely used in the airline context by showing nature from a bird’s eye view (e.g., KLM Citation2019).

A rising body of literature has investigated the effects of greenwashing (e.g., Nyilasy, Gangadharbatla, and Paladino Citation2014; Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015). These studies, mostly experiments, have shown that the perception of greenwashing is higher when a false claim was presented in comparison to a substantial claim, a vague claim, or an executional greenwashing claim (e.g., Nyilasy, Gangadharbatla, and Paladino Citation2014; Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015, Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). However, previous research has focused only on a few greenwashing strategies, neglecting other prominent types like omission claims in form of widely used compensation claims (Matthes Citation2019).

Perceived schema incongruity in green advertising claims for airlines

Schema Incongruity Processing Theory (Mandler Citation1982) suggests that if new information does not fit in existing mental schemata, attention is directed toward it and the intensity of information processing is heightened (Baker and Petty Citation1994; Homer and Kahle Citation1986). For example, independently of individuals’ cognitive effort, their characteristics, and situational influences, unexpected combinations of unrelated objects in advertising motivate individuals to more attentive information processing. Because such ads do not fit into existing mental schemata of consumers, more cognitive effort is used to understand the paradox information (Homer and Kahle Citation1986).

Due to a change in moral and social norms over the past decades, nowadays, flying is seen as environmentally harmful and socially undesirable (Gössling, Humpe, and Bausch Citation2020). Hence, when individuals see airline advertising, the environmentally harmful character of flying may be immediately salient. Thus, based on Schema Incongruity Processing Theory, airline advertising promoting the environmental friendliness may be perceived by consumers as unexpected, out-of-context, and inadequate, because it is not congruent with their existing mental structures. Thus, attention is increased and individuals allocate more cognitive resources to the ad. As has been shown, cognitive effort is one of the key preconditions to detect greenwashing (Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). Hence, individuals may perceive the companies’ ‘twofolded behavior’ to promote an environmentally friendly image for an inherently environmentally unfriendly service (De Freitas Netto et al. Citation2020, 6). This mechanism can be theorized to occur for all types of greenwashing claims, because for all claims, the twofolded behavior is clearly apparent. This leads to our first hypothesis:

H1: If (a) an abstract compensation, (b) a concrete compensation, (c) a vague, and (d) a false greenwashing claim is presented in an airline ad, perceived greenwashing will be higher compared to an ad presenting no green claims.

H2: When (a) a vague or (b) a false claim is presented in an airline ad, perceived greenwashing will be higher compared to abstract and concrete compensation claims.

H3: When an abstract compensation claim is presented in an airline ad, perceived greenwashing will be higher compared to an ad presenting a concrete compensation claim.

The moderating role of environmental knowledge

According to the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM; Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986), involvement, that is the degree of ‘personal relevance of the topic’, determines the motivation to engage in elaboration of media content (O’Keefe Citation2013, 1). Further, the ELM suggests that attitudes can be formed either via the ‘central route’ in case of high involvement, or, for low involved consumers, via the ‘peripheral route’ (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986, 125). When information is processed via the central route, the quality of the arguments used in a persuasive message are closely scrutinized by individuals and other relevant material is included in the assessment of the messages’ credibility. In contrast, when information is processed via the peripheral route, individuals rather focus on peripheral cues.

When it comes to green advertising, the major indicator for consumer involvement is topical environmental knowledge (Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015). Based on the ELM, topical environmental knowledge about the harmful consequences of flying increases involvement with environmental topics (O’Keefe Citation2013). Consequently, the motivation to engage in issue-relevant, extensive thinking about green airline advertising claims also increases. In the case of greenwashing, consumers scrutiny due to topical environmental knowledge could uncover the misleading attempt. To sum it up, topical knowledge could help to judge the trustworthiness of advertising and hence could (negatively) affect the ‘persuasive success’ of the green advertising claim (O’Keefe Citation2013, 3). However, only a few experimental studies have investigated the role of topical environmental knowledge (e.g., Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015). They have found that topical environmental knowledge helps consumers to perceive greenwashing at least in false claims (Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). We therefore assume that consumers with high topical environmental knowledge are better able to detect greenwashing compared to consumers low in topical environmental knowledge. High topical knowledge leads to a ‘thoughtful’ evaluation of the claims (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986, 125). Such thoughtful elaboration can be argued to increase the perceived discrepancy between the claim and the fact that flying is environmentally unfriendly. Thus:

H4: When compared to an ad with no green claims, the effect of an (a) abstract compensation claim, (b) concrete compensation claim, (c) vague claim, and (d) false claim on perceived greenwashing is higher for respondents high in topical environmental knowledge as compared to less knowledgeable respondents.

Consumers’ cognitive and affective responses

Generally, green advertising has positive effects on ad attitude (e.g., Matthes, Wonneberger, and Schmuck Citation2014), brand evaluation (e.g., Hartmann, Apaolaza Ibáñez, and Forcada Sainz Citation2005), and purchase intention (e.g., Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). Therefore, we derive our fifth hypothesis:

H5: If (a) an abstract compensation, (b) a concretecompensation, (c) a vague, and (d) a false greenwashing claim is presented in an airline ad, brand evaluation will be increased compared to an ad presenting no green claims.

H6: If (a) an abstract compensation, (b) a concrete compensation, (c) a vague, and (d) a false greenwashing claim is presented in an airline ad, flight shame will be decreased compared to an ad presenting no green claims.

H7: Perceived greenwashing decreases brand evaluation for the advertised brands.

H8: Perceived greenwashing increases flight shame.

Material and methods

We conducted an online experiment with a 2 × 5 between-subject design manipulating topical environmental knowledge (i.e., environmental facts about flying vs. non environmental facts) and the type of greenwashing claim (i.e., abstract compensation vs. concrete compensation vs. vague vs. false vs. control) in green ads of three different airlines (e.g., multi message design). To manipulate knowledge, participants of the study (N = 658) were first randomly assigned to either the environmental facts condition or the non-environmental facts condition. In both groups, they viewed a journalistic article from an existing online newspaper. Second, they were randomly assigned to an experimental greenwashing claim condition where we showed them three ads from three existing airline-brands (HiFly, s7 airlines, and SprintAir) or to the control group (i.e., no green claim).

Participants, stimuli, and procedure

We recruited participants (N = 658) from the panel of a professional market research company in December 2019. We worked with a quota-based sample representing German consumers with regard to age (Mage = 41.49, SD = 13.21), gender (50.3% women), and education (29.2% no education or lower-secondary education, 46.4% complete secondary education, 24.5% complete university education).

To manipulate knowledge, participants saw either an article with environmental facts about flying (e.g., environmental consequences of the growing aviation sector) or an article with information about robotics in the working world (control group; e.g., consequences of robots on the job market). While the content of the articles varied across the two conditions, the articles’ length and sentence constellation, as well as the newspapers’ design was identical. In a second step, fifteen versions of an ad were presented in the form of Twitter postings of three different airlines. As a context, Twitter was chosen because it is a frequently used platform for brand communication (e.g., Walasek, Bhatia, and Brown Citation2018). For each airline, we created five ads and prepared them to fit to one of the four experimental conditions as well as the control group (i.e., non-green claim promoting relaxed holidays). We used a multi message design including three ad versions of three existing but rather unknown airline companies per condition (Reeves, Yeykelis, and Cummings Citation2016). Since we placed a ‘major emphasis on external validity’ when operationalizing the different greenwashing claims in airline advertising (Slater Citation1991, 416), we asked European senior scholars (N = 6) in the field of green advertising to assess the different ads and categorize them as abstract compensation, concrete compensation, vague and false claims. We provided scholars with definitions of the claims and asked them to match the 12 ads to these definitions. The ads were presented to them in a random order. Results supported our operationalization of the advertising claims. On average, 8.83 ads out of 12 ads were correctly identified by the experts, suggesting acceptable internal validity of our stimuli.

The abstract compensation condition contained three ads promoting future environmental compensation. The concrete compensation condition included three ads proposing immediate compensation for the environmental impact of flying. Participants in the vague condition viewed three ads with ambiguous or very broad environmental claims (see Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). The false condition comprised three ads based on an outright lie. Lastly, in the control condition, no references to environmental or green actions were made, the main focus of the ads was on holidays and relaxation, no green arguments were provided. We created the greenwashed ads drawing on existing ads that contained greenwashed elements. The ads’ layout, colors, and images were identical. In order to avoid strong prior attitudes, potential confounds, and to ensure high external validity, we decided to use small but real airline companies for our stimuli. The stimuli are shown in the Appendix A, .

Written informed consent was obtained, participants were randomly assigned to the conditions, and the ads were shown in random order followed by the questionnaire and debriefing.

Measures

We assessed topical environmental knowledge with six single-choice items. The items dealt with information about the environmental impact of flying, about flight statistics, and about the Paris climate agreement related to flying. All information to answer the questions correctly was mentioned in the environmental journalistic article. By summing up the correct answers, we created a seven-point scale (0 = no topical environmental knowledge, 6 = high topical environmental knowledge; M = 2.70, SD = 1.25). For all items, see Appendix A, .

We measured perceived greenwashing with three items adapted from Chen and Chang (Citation2013) on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ (Cronbach’s α = .79; M = 4.78; SD = 1.61).

For brand evaluation, we built on three adjective pairs for each airline (e.g., Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018) on a seven-point semantic differential scale. Since (1) there is no theoretical basis to investigate differences between the brands, (2) we are solely interested in the effect across the brands (i.e., the overall effect), (3) a factor analysis using all items yielded one general factor for ‘brand evaluation’ (see Appendix B, under OSF; https://osf.io/9wd7p/?view_only=c7afccc4586a469692c7ded6def85df2) and (4) all the brand evaluation variables were highly correlated (see Appendix B, under OSF), we created one index consisting of nine items (Cronbach’s α = .97; M = 3.57, SD = 1.42).

Flight shame was measured with seven items, three of them adapted from the Internalized Shame Scale (ISS; Cook Citation1996). The items were measured on a seven-point scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ (Cronbach’s α = .91; M = 2.63, SD = 1.49).

Randomization and manipulation check

Randomization and manipulation checks were successful. We detail these findings in Appendix B, and under OSF.

Statistical model

We used PROCESS 3.5, Model 8, involving 5.000 bootstrap samples (Hayes Citation2018). We treated advertising claim as our independent, multifactorial (multicategorial) variable and used the control condition as our reference condition for analyzing H1, H2, and H4, H5, and H6. To test H3, we used the concrete compensation condition as a reference category.

As mediator, we inserted perceived greenwashing and as moderator, topical environmental knowledge using the topical environmental knowledge control condition as a reference condition. The two dependent variables were examined in two separate models (both Model 8). For the first analysis, we used PROCESS Model 8 (Model 8a), where we defined X as advertising claim, M as perceived greenwashing, W as topical environmental knowledge (dummy-coded), and Y as brand evaluation. For the second analysis (Model 8b), we proceeded in the same way, with the exception that we inserted flight shame as Y. In both models we additionally included the following covariates: age, gender, education, and flying frequency. We included these control variables because, theoretically, these variables could also explain our hypothesized effects as they have been found to be related to various environmental attitudes (Becker et al. Citation2016; Buttel Citation1979; Haytko and Matulich Citation2008; Van Liere and Dunlap Citation1980; Wright and Lynch Citation1995).

Additionally, we carried out a variance analysis with repeated measures to check if type of brand has an influence on our findings. Results indicated there is no interaction effect of perceived greenwashing and brand type (F(1.937, 1261.218) = 2.61, p = .075).

Results

We checked the effects of the causal mediation analysis separately for our two models (Model 8a, Model 8b) using the mediation package in R (Tingley et al. Citation2019). Results showed significant average causal mediated effects (ab = −0.16, 95%CI = [-0.28, −0.07], p < .001; ab’ = 0.18, 95%CI = [0.08, 0.30], p < .001) and mixed total effects (c = .23, 95%CI = [-0.09, 0.57], p = .161; c’ = .45, 95%CI = [0.09, 0.80], p = .012). We continued our moderated mediation analysis with both models justified by Hayes (Citation2018), stating that ‘a single inferential test of the indirect effect is all that is needed’ (116). All effects of the causal mediation analysis can be found in the Appendix B, under OSF.

Moderated mediation path a: effect of advertising claim on perceived greenwashing

We found that concrete compensation claims did not lead to a higher level of perceived greenwashing compared to the control condition (b = 0.33, LLCI = −0.21, ULCI = 0.86, t = 1.23, p = .218). However, the abstract compensation claim (b = 1.10, LLCI = 0.56, ULCI = 1.65, t = 3.97, p < .001), the vague claim (b = 1.38, LLCI = 0.84, ULCI = 1.91, t = 5.06, p < .001), and the false claim (b = 1.24, LLCI = 0.71, ULCI = 1.76, t = 4.62, p < .001) had significantly higher levels of perceived greenwashing than the control condition, confirming hypotheses 1a, 1c, and 1d. We found no support for hypothesis 2: Results showed that vague claims (M = 5.25, SD = 1.45) did have a higher level of perceived greenwashing compared to concrete compensation claims (b = 1.04, LLCI = 0.53, ULCI = 1.55, t = 4.01, p < .001; M = 4.55, SD = 1.51), but not compared to abstract compensation claims (b = 0.27, LLCI = −0.25, ULCI = 0.80, t = 1.01, p = .311; M = 4.98, SD = 1.42). Similarly, false claims (b = 0.90, LLCI = 0.40, ULCI = 1.41, t = 3.52, p = .001; M = 5.23, SD = 1.50) did have a higher level of perceived greenwashing compared to concrete compensation (M = 4.55, SD = 1.51), but not compared to abstract compensation (b = 0.13, LLCI = −0.39, ULCI = 0.65, t = 0.50, p = .615; M = 4.98, SD = 1.42). By and large, vague and false claims did not generally lead to more perceived greenwashing compared to compensation claims. In line with H3, when using the concrete compensation condition as a reference category, findings indicated that the abstract compensation claim (M = 4.98, SD = 1.42) significantly increased perceived greenwashing compared to the concrete compensation claim (b = 0.77, LLCI = 0.25, ULCI = 1.29, t = 2.91, p = .004; M = 4.55, SD = 1.51) as well as to the control group (b = 1.10, LLCI = 0.56, ULCI = 1.65, t = 3.97, p < .001; M = 3.86; SD = 1.76). Therefore, H3 is strongly supported. For descriptive statistics, please see Appendix B, under OSF.

Moderated mediation path W*a: moderating effect of topical environmental knowledge

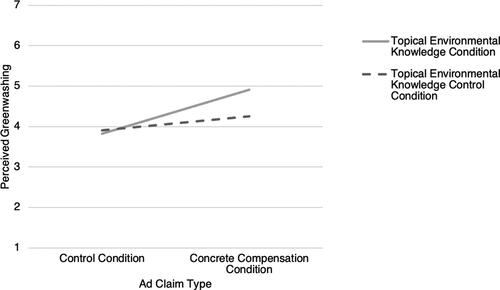

Only partly consistent with our assumption (H4), we found an interaction effect of topical environmental knowledge with the concrete compensation condition (b = 0.81, LLCI = 0.06, ULCI = 1.56, t = 2.12, p = .034; M = 4.91, SD = 1.45) on perceived greenwashing. That is, concrete compensation only increased perceived greenwashing when topical environmental knowledge was manipulated. For the other experimental conditions, neither an interaction effect (abstract compensation*topical environmental knowledge: b = 0.05, LLCI = −0.69, ULCI = 0.79, t = 0.14, p = .892; vague*topical environmental knowledge: b = 0.09, LLCI = −0.64, ULCI = 0.83, t = 0.24, p = .804; false*topical environmental knowledge: b = 0.41, LLCI = −0.33, ULCI = 1.16, t = 1.09, p = .277), nor a main effect of topical environmental knowledge on perceived greenwashing (b = −0.08, LLCI = −0.61, ULCI = 0.44, t = −0.31, p = .755) were found. Hence, while hypothesis 4b found support, hypothesis 4a, hypothesis 4c, and hypothesis 4d, did not. The interaction effect is shown in .

Figure 2. The interaction effect of the concrete compensation condition and topical environmental knowledge on perceived greenwashing in comparison to the control condition.

Note. Descriptive statistics for all four interaction groups: Concrete compensation condition*Topical environmental knowledge condition (M = 4.91, SD = 1.45); Concrete compensation condition*Topical environmental knowledge control condition (M = 4.25, SD = 1.51); Control condition*Topical environmental knowledge condition (M = 3.82, SD = 1.71); Control condition*Topical environmental knowledge control condition (M = 3.90, SD = 1.83). Interaction effect is significant at the p < .05 level (b = 0.81, LLCI = 0.06, ULCI = 1.56, t = 2.12, p = .034).

Moderated mediation path c: effect of green advertising on brand evaluation

Only partly in line with H5, we found a significant main effect of the concrete compensation condition on brand evaluation (b = 0.55, LLCI = 0.06, ULCI = 1.03, t = 2.23, p = .026) compared to the control group. The other conditions had no effects on brand evaluation (abstract compensation: b = 0.48, LLCI = −0.02, ULCI = 0.98, t = 1.89, p = .061; vague: b = 0.06, LLCI = −0.43, ULCI = 0.58, t = 0.26, p = .797; false: b = 0.39, LLCI = −0.09, ULCI = 0.88, t = 1.59, p = .112).

Moderated mediation path c’: effects of green advertising on flight shame

Contrary to H6, we found no main effects of the experimental ad conditions compared to the ad control condition on flight shame (abstract compensation: b = 0.32, LLCI = −0.21, ULCI = 0.86, t = 1.19, p = .234; concrete compensation: b = 0.41, LLCI = −0.10, ULCI = 0.92, t = 1.58, p = .115; vague: b = 0.37, LLCI = −0.16, ULCI = 0.89, t = 1.37, p = .171; false: b = −0.04, LLCI = −0.55, ULCI = 0.48, t = −0.15, p = .880).

Moderated mediation path b: effects of perceived greenwashing on brand evaluation

In line with H7, there was a negative relation of perceived greenwashing with brand evaluation (b = −0.14, LLCI = −0.21, ULCI = −0.07, t = −4.04, p < .001). Formally, we observed a mediation effect of ad condition on brand evaluation via perceived greenwashing, independent of the topical environmental knowledge manipulation, with respect to the abstract compensation condition (topical environmental knowledge condition: b = −0.17, SE = 0.06, LLCI = −0.31, ULCI = −0.06; topical knowledge control condition; b = −0.17, SE = 0.06, LLCI = −0.30, ULCI = −0.06; index of moderated mediation = −0.01, SE = 0.06, LLCI = −0.13, ULCI = 0.12), the concrete compensation condition (topical environmental knowledge condition: b = −0.16, SE = 0.06, LLCI = −0.30, ULCI = −0.06; topical knowledge control condition; b = −0.05, SE = 0.05, LLCI = −0.15, ULCI = 0.04; index of moderated mediation = −0.12, SE = 0.07, LLCI = −0.27, ULCI = −0.00), the vague condition (topical environmental knowledge condition: b = −0.21, SE = 0.07, LLCI = −0.37, ULCI = −0.08; topical environmental knowledge control condition; b = −0.20, SE = 0.07, LLCI = −0.35, ULCI = −0.08; index of moderated mediation = −0.01, SE = 0.06, LLCI = −0.14, ULCI = −0.10), and the false condition (topical environmental knowledge condition: b = −0.24, SE = 0.08, LLCI = −0.39, ULCI = −0.10; topical environmental knowledge control condition; b = −0.18, SE = 0.07, LLCI = −0.33, ULCI = −0.07; index of moderated mediation = −0.06, SE = 0.06, LLCI = −0.19, ULCI = 0.06), in comparison to the control group.

Moderated mediation path b’: effects of perceived greenwashing on flight shame

In line with H8, we found that perceived greenwashing increases anticipated flight shame (b = 0.16, LLCI = 0.08, ULCI = 0.23, t = 4.17, p < .001). The mediation path via perceived greenwashing was insignificant for the abstract compensation condition (topical environmental knowledge condition: b = 0.18, SE = 0.06, LLCI = 0.08, ULCI = 0.31; topical environmental knowledge control condition; b = 0.18, SE = 0.07, LLCI = 0.06, ULCI = 0.32; index of moderated mediation = 0.01, SE = 0.07, LLCI = −0.12, ULCI = 0.14), the concrete compensation condition (topical environmental knowledge condition: b = 0.18, SE = 0.06, LLCI = 0.07, ULCI = 0.32; topical environmental knowledge control condition: b = 0.05, SE = 0.05, LLCI = −0.04, ULCI = 0.16; index of moderated mediation = 0.13, SE = 0.07, LLCI = −0.00, ULCI = 0.29), the vague condition (topical environmental knowledge condition: b = 0.23, SE = 0.07, LLCI = 0.11, ULCI = 0.39; topical environmental knowledge control condition; b = 0.22, SE = 0.07, LLCI = 0.09, ULCI = 0.38; index of moderated mediation = 0.01, SE = 0.07, LLCI = −0.12, ULCI = 0.14), and the false condition (topical environmental knowledge condition: b = 0.26, SE = 0.08, LLCI = 0.12, ULCI = 0.43; topical environmental knowledge control condition; b = 0.20, SE = 0.07, LLCI = 0.07, ULCI = 0.34; index of moderated mediation = 0.07, SE = 0.07, LLCI = −0.06, ULCI = 0.21), compared to the control group.

For all results, see . For an overview of the hypotheses and analysis, see Appendix A, .

Table 1. Summary of the moderated mediation model.

Discussion

We showed, for the first time, that while vague claims, false claims, and abstract compensation claims are perceived as greenwashing to a higher degree as non-green(washed) claims by consumers, concrete compensation claims are not. A possible explanation of this finding might be that consumers perceive green airline ads as incongruent with existing mental representations (i.e., flying is environmentally harmful). As a consequence, consumers’ cognitive attention toward the ad may increase, ultimately leading to perceptions of greenwashing. However, not all greenwashing claims may foster this perception. In fact, when we look at the results of H1, we found that consumers accept green claims offering concrete green compensations. This finding may be explained by the fact that, compared to the other greenwashing claims, theoretically speaking, the incongruence between the ad and existing mental representations could be lower. However, contrary to the assumed effects in H2, perceived greenwashing was not higher when a vague or a false claim was presented than when a compensation claim was shown. As hypothesized in H3, perceived greenwashing in concrete compensation claims was only higher compared to abstract compensation. This suggests that consumers may believe in the realization of concrete compensation measures due to smaller psychological distance (Trope and Liebermann Citation2010). Theoretically, concrete compensation can be immediately observed by consumers, leading to stronger green compensatory beliefs compared to abstract claims (Hope et al. Citation2018). Compensatory beliefs, in turn, may distract consumers from perceiving greenwashing (Hope et al. Citation2018). There are, however, other possible explanations.

Further, contrasting to our H4, results showed that the effects of vague, false, and abstract compensation claims were independent from topical environmental knowledge. That is, even consumers with low topical environmental knowledge perceive greenwashing in vague, false, and abstract compensation claims. This finding stands in contrast to prior research, which showed that knowledge can moderate the effects of greenwashed claims on greenwashing perceptions (Schmuck, Matthes, and Naderer Citation2018). However, we have to keep in mind that airlines offer inherently environmentally unfriendly services. For other services, such as food or convenience goods, knowledge may be necessary to create an incongruence between the ad and pre-existing beliefs, leading to greenwashing perceptions. Yet, our study showed, that when topical environmental knowledge was given, concrete compensation was perceived to a stronger degree as greenwashing than when topical environmental knowledge was not given. One may argue that topical knowledge is necessary to weight the compensation offered in the ad with the actual environmental harm done by flying. For low knowledgeable individuals, the compensation may be perceived as adequate; however, when there is high knowledge, the compensation may appear as a drop in the ocean, compared to the harm of flying. At this point, it needs to be stressed that we conceptualize greenwashing as a perception, not an objective attribute (Seele and Gatti Citation2017).

Findings only partially support H5 and do not support H6. We found a positive direct effect of the concrete compensation claim on brand evaluation, which was not mediated by perceived greenwashing. This is consistent with findings of other studies suggesting that green advertising with concrete compensation claims has positive effects on brand evaluations. This result may be explained by the fact that concrete compensation may be generally interpreted as a positive, voluntary move of companies, triggering consumers’ positive attitudes. Further investigations are needed to shed light on this. Besides, this study was unable to demonstrate that green advertising reduces flight shame. It seems possible that these results are due to the fact, that the mere exposure to green advertising is too weak to reduce strong feelings like flight shame. Although Mazar and Zhong (Citation2010) showed that mere exposure to green services may trigger ‘social considerations’ (497), future studies that focus on real purchase behavior of green services instead of mere exposure to green advertising are suggested.

Finally, in line with H7 and H8, this study demonstrated that perceived greenwashing has negative consequences. That is, perceived greenwashing decreases consumers’ brand evaluations. Apart from that, we showed, for the first time, that perceived greenwashing evoked flight shame. As shame motivates avoidance tendencies, individuals may tend to avoid the shame-inducing behavior and feel morally responsible to behave more pro-environmentally in the future (e.g., Amatulli et al. Citation2019). In the context of inherently environmentally unfriendly services like flying, this result is striking. It shows that green airline advertising can lead to a boomerang effect eventually motivating consumers to avoid flying. Obviously, further research is needed to better understand the behavioral consequences of flight shame.

Limitations and future research

There are at least six limitations. First, we only examined greenwashing claims promoting inherently environmentally unfriendly services. Perceptions of greenwashing might be different for other products and services. Second, since we did not directly measure compensatory green beliefs, further research is needed to better understand the effects of compensatory green beliefs as a motivation to accept green claims. Third, we did not investigate long-term effects. Future research should apply non-experimental designs as well as behavioral measures. Fourth, we only measured topical environmental knowledge as a post-test measurement after the experimental knowledge manipulation. Although previous studies have proceeded in a very similar way (Fabrigar et al. Citation2006; Nelson, Wood, and Paek Citation2009; Ovrum et al. Citation2012) it would be methodically more precise to additionally measure pre-existing environmental knowledge of participants (Fernandes, Segev, and Leopold Citation2020). Fifth, methodically, we used a multi message design that is theoretically strongly guided by observations from advertising practice of airlines (Slater Citation1991). Although the experts rating of advertising claims suggested acceptable internal validity of our stimuli, we must note, that the results of the experts rating could have turned out more clearly in benefit of our claim categorization. Hence, caution must be applied when interpreting and generalizing the results of this study. Lastly, since there are currently no possibilities to fly sustainably (e.g., Snow Citation2021), it was not possible for us to create a substantial green claim that is extern valid and serves as a reference group for all our stimuli. In the future, an externally valid substantial green ad should be used as a reference group.

Theoretical, methodological, and practical implications

With regard to theoretical implications, Schema Incongruity Processing Theory (Mandler 1982) allows important predictions. First, greenwashing may be only perceived when existing mental structures do not align with the advertised claim. This means, greenwashing strategies may be detected in the case of airline ads, but could remain unrecognized for other services with less negative mental structures regarding sustainability. Second, the ELM (Petty and Cacioppo 1986) helps us to explain how topical environmental knowledge increases the ability to weight the environmental harms against the environmental benefits promoted in an ad. Third, our study showed for the first time, that consumers’ greenwashing perceptions of hitherto uninvestigated greenwashing claims, namely concrete compensation claims, differ from abstract compensation, vague, and false claims potentially based on different underlying theoretical mechanisms such as perceived psychological distance (Liberman and Trope Citation1998) or green compensatory beliefs (Hope et al. Citation2018). Lastly, our study contributes to a better understanding of how perceptions of greenwashing can trigger psychological reactance (Brehm 1966). Besides the negative influence of perceived greenwashing on consumers’ cognitions (brand evaluations), we also observed it on consumers’ affect (flight shame).

Considering methodological implications, no previous study in this context has manipulated topical environmental knowledge until now. We believe that a manipulation of knowledge usefully supplements and extends the previous literature by allowing us to directly test which chunks of knowledge are necessary in order to enhance greenwashing perceptions.

If we turn to practical implications for advertisers, we see several possibilities to avoid greenwashed advertising. First, we recommend that advertisers should focus on truthful, precise, and substantial green claims. Second, although industry guidelines for the use of environmental marketing claims already exist, we believe that they are incomplete. We call for regular updates of the green guides, including abstract and concrete compensation claims (FTC Citation2012). Third, since it is challenging to communicate complex environmental information concisely and understandable for consumers with different degrees of environmental knowledge, companies need to pay close attention to consumers’ understanding of compensation claims. Here, ‘a uniform, accepted standard’ could help advertisers to avoid greenwashing as well as consumers to get more clarity about the environmental benefit achieved through the compensation measure. Additionally, information about the scope of the compensation, the timing of the compensation, and the quality of the compensation should be mandatory to provide when environmental compensation is offered (Polonsky, Grau, and Garma Citation2010). Finally, tools that help consumers to detect misleading advertising claims should be implemented. Interactive tools like the technology of Quick Response (QR) codes and barcodes including a traffic light system could make it easier for consumers to interpret various green advertising claims (e.g., Parguel, Benoit-Moreau, and Russell Citation2015). Especially for compensation claims, carbon labels including ‘product or service footprints’ that provide precise information about the CO2 emissions of the products or services could not only educate, but also motivate consumers to reduce their CO2 emissions (European Commission Citation2014). Besides, advertising literacy campaigns may empower consumers to question the misleading messages.

Conclusion

Companies are increasingly interested to use green advertising claims to position themselves as environmentally active and friendly. Against this background, greenwashing may appear as an attractive strategy, especially for products and services that are inherently environmentally unfriendly. Our findings on airline ads clearly show that several types of greenwashing claims yield different effects. By and large, however, our study suggests that greenwashing is likely to harm the brand, directly and indirectly: directly, because perceived greenwashing leads to more negative brand evaluations, and indirectly, because greenwashing can foster flight shame, making future airline travel less likely. The only exception are concrete greenwashing claims paired with low consumer topical environmental knowledge. Since environmental knowledge can be expected to rise in the future due to a global increase in environmental concern, we conclude that greenwashing does not pay off for the airline industry. By contrast, it harms more than it benefits.

Notes on Contributors

Ariadne Neureiter is a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Communication at the University of Vienna. She studied communication science and psychology and focuses on research on strategic (sustainability) communication, effects of green advertising, and digital media. Jörg Matthes (Ph.D., University of Zurich) is a communication science professor and head of the Department of Communication at the University of Vienna. He focuses on research on advertising, digital media, political communication, and quantitative methods.

Author note

Ariadne Neureiter (MA, MSc; phd candidate; [email protected]), Jörg Matthes (Univ.-Prof. Dr; head of department; [email protected]), Advertising and Media Psychology Research Group, Department of Communication, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Vienna, Währingerstr. Str. 29, 1090 Austria.

Funding statement

To conduct this research, there was no funding involved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The research data used in this study is freely available in a public data repository of the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/9wd7p/?view_only=c7afccc4586a469692c7ded6def85df2).]

References

- Air New Zealand. 2019. Air New Zealand’s carbon offset programme. www.airnewzealand.co.nz/sustainability-customer-carbon-offset (accessed September 10, 2020).

- Amatulli, C., M. de Angelis, A.M. Peluso, I. Soscia, and G. Guido. 2019. The effect of negative message framing on green consumption: An investigation of the role of shame. Journal of Business Ethics 157, no. 4: 1111–32.

- Baker, S.M., and R.E. Petty. 1994. Majority and minority influence: Source-position imbalance as a determinant of message scrutiny. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67, no. 1: 5–19.

- Becker, T.E., G. Atinc, J.A. Breaugh, K.D. Carlson, J.R. Edwards, and P.E. Spector. 2016. Statistical control in correlational studies. 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. Journal of Organizational Behavior 37, no. 2: 157–67.

- BEUC. 2020. Getting rid of greenwashing. https://www.beuc.eu/publications/beuc-x-2020-116_getting_rid_of_green_washing.pdf (accessed July 6, 2021).

- Brehm, J.W. 1966. A theory of psychological reactance. New York: Academic Press.

- Buttel, F.H. 1979. Age and environmental concern. A multivariate analysis. Youth & Society 10, no. 3: 237–56.

- Carlson, L., S.J. Grove, and N. Kangun. 1993. A content analysis of environmental advertising claims: A matrix method approach. Journal of Advertising 22, no. 3: 27–39.

- Carlson, L., S.J. Grove, N. Kangun, and M.J. Polonsky. 1996. An international comparison of environmental advertising: Substantive versus associative claims. Journal of Macromarketing 16, no. 2: 57–68.

- Chen, Y.S., and C.-H. Chang. 2013. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects on green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. Journal of Business Ethics 114, no. 3: 489–500.

- Cook, D.R. 1996. Empirical studies of shame and guilt: The internalized shame scale. In Knowing feeling: Affect, scripts and psychotherapy, ed. Donald L. Nathanson, 132–165. New York: Norton & Company.

- De Freitas Netto, S.V., M.F.F. Sobral, A.R.B. Ribeiro, and G.R. da Luz Soares. 2020. Concepts and forms of greenwashing. A systematic review. Environmental Science Europe 32, no. 19: 1–12.

- Dillard, J.P., and L. Shen. 2005. On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Communication Monographs 72, no. 2: 144–68.

- European Commission. 2014. Product footprinting. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/research/newsalert/pdf/28si_en.pdf (accessed July 6, 2021).

- Fabrigar, L.R., R.E. Petty, S.M. Smith, and S.L. Crites. 2006. Understanding knowledge effects on attitude-behavior consistency: The role of relevance, complexity, and amount of knowledge. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90, no. 4: 556–77.

- Federal Trade Commission (FTC). 2012. Guides for the use of environmental marketing claims. https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/federal_register_notices/guides-use-environmental-marketing-claims-green-guides/greenguidesfrn.pdf (accessed September 15, 2020).

- Fernandes, J., S. Segev, and J.K. Leopold. 2020. When consumers learn to spot deception in advertising: Testing a literacy intervention to combat greenwashing. International Journal of Advertising 39, no. 7: 1115–49.

- Frontier Airlines. 2019. America’s greenest flight. https://twitter.com/flyfrontier/status/1159075524628623360 (accessed September 10, 2020).

- Gössling, S., A. Humpe, and T. Bausch. 2020. Does ‘flight shame’ affect social norms? Changing perspectives on the desirability of air travel in Germany. Journal of Cleaner Production 266: 122015–0.

- Han, N.R., T.H. Baek, S. Yoon, and Y. Kim. 2019. Is that coffee mug smiling at me? How anthropomorphism impacts the effectiveness of desirability vs. feasibility appeals in sustainability advertising. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 51, : 352–61.

- Hartmann, P., V. Apaolaza Ibáñez, and F.J. Forcada Sainz. 2005. Green branding effects on attitude: Functional versus emotional positioning strategies. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 23, no. 1: 9–29.

- Hayes, A.F. 2018. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. A regression-based approach. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

- Haytko, D.L., and E. Matulich. 2008. Green advertising and environmentally responsible consumer behaviors. Linkages examined. Journal of Management and Marketing Research 7, no. 1: 2–11.

- Hibbert, J.F., J.E. Dickinson, S. Gössling, and S. Curtin. 2013. Identity and tourism mobility: An exploration of the attitude–behaviour gap. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 21, no. 7: 999–1016.

- HiFly. 2019. End plastic pollution. www.hifly.aero/media-center/new-campaign-to-end-plastic-pollution/ (accessed September 10, 2020).

- Homer, P.M., and L.R. Kahle. 1986. A social adaptation explanation of the effects of surrealism on advertising. Journal of Advertising 15, no. 2: 50–60.

- Hope, A.L.B., C.R. Jones, T.L. Webb, M.T. Watson, and D. Kaklamanou. 2018. The role of compensatory beliefs in rationalizing environmentally detrimental behaviors. Environment and Behavior 50, no. 4: 401–25.

- Kangun, N., L. Carlson, and S.J. Grove. 1991. Environmental advertising claims – a preliminary investigation. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 10, no. 2: 47–58.

- Kilbourne, W.E., S. Banerjee, C.S. Gulas, and E. Iyer. 1995. Green advertising: Salvation or oxymoron? Journal of Advertising 24, no. 2: 7–18. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A17283095/AONE?u=43wien&sid=AONE&xid=44b67f09 (accessed July 6, 2021).

- KLM. 2019. Fly responsibly. https://flyresponsibly.klm.com/gb_en#home (accessed September 10, 2020).

- Koenig-Lewis, N., A. Palmer, J. Dermody, and A. Urbye. 2014. Consumers’ evaluations of ecological packaging: Rational and emotional approaches. Journal of Environmental Psychology 37: 94–105.

- Koslow, S. 2000. Can the truth hurt? How honest and persuasive advertising can unintentionally lead to increased consumer skepticism. Journal of Consumer Affairs 34, no. 2: 245–68.

- Liberman, N., and Y. Trope. 1998. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75, no. 1: 5–18.

- Majoras, Deborah Platt. 2008. Statement carbon offset workshop opening remarks. https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/public_statements/opening-remarks/080108carbonow.pdf (accessed July 6, 2021).

- Mandler, G. 1982. The structure of value: Accounting for taste. In Affect and cognition, ed. Margaret S. Clark and Susan T. Fiske, 3–36. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315802756

- Matthes, J. 2019. Uncharted territory in research on environmental advertising: Toward an organizing framework. Journal of Advertising 48, no. 1: 91–101.

- Matthes, J., A. Wonneberger, and D. Schmuck. 2014. Consumers’ green involvement and the persuasive effects of emotional versus functional ads. Journal of Business Research 67, no. 9: 1885–93.

- Mayer, R., T. Ryley, and D. Gillingwater. 2014. The role of green marketing: Insights from three airline case studies. Journal of Sustainable Mobility 1, no. 2: 1–19.

- Mazar, N., and C.-B. Zhong. 2010. Do green products make us better people? Psychological Science 21, no. 4: 494–8.

- Meijers, M.H.C., M.K. Noordewier, P.W.J. Verlegh, W. Willems, and E.G. Smit. 2019. Paradoxical side effects of green advertising: How purchasing green products may instigate licensing effects for consumers with a weak environmental identity. International Journal of Advertising 38, no. 8: 1202–23.

- Naderer, B., D. Schmuck, and J. Matthes. 2017. Greenwashing: Disinformation through green advertising. In Commercial communication in the digital age. Information or disinformation?, ed. Gabriele Siegert, Bjorn Von Rimscha, and Stephanie Grubenmann, 105–120. Berlin: De Gruyter Saur. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110416794-007

- Nelson, M.R., M.L.M. Wood, and H.-J. Paek. 2009. Increased persuasion knowledge of video news releases: Audience beliefs about news and support for source disclosure. Journal of Mass Media Ethics 24, no. 4: 220–37.

- Nyilasy, G., H. Gangadharbatla, and A. Paladino. 2014. Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. Journal of Business Ethics 125, no. 4: 693–707.

- O’Keefe, D.J. 2013. Elaboration likelihood model. In The international encyclopedia of communication. 1st ed. Wolfgang Donsbach, 1–7. New Jersey, United States: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiece011.pub2

- Ovrum, A., F. Alfnes, V.L. Almli, and K. Rickertsen. 2012. Health information and diet choices: Results from a cheese experiment. Food Policy 37, no. 5: 520–9.

- Parguel, B., F. Benoit-Moreau, and C.A. Russell. 2015. Can evoking nature in advertising mislead consumers? The power of ‘executional greenwashing. International Journal of Advertising 34, no. 1: 107–34.

- Petty, R.E., and J.T. Cacioppo. 1986. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 19: 123–205.

- Polonsky, M.J., R. Garma, and S. Grau. 2011. Western consumers’ understanding of carbon offsets and its relationship to behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 23, no. 5: 583–603.

- Polonsky, M.J., S.L. Grau, and R. Garma. 2010. The new greenwash? Potential marketing problems with carbon offsets. International Journal of Business Studies: A Publication of the Faculty of Business Administration, Edith Cowan University 18, no. 1: 49–54. http://dro.deakin.edu.au/eserv/DU:30033004/polonsky-thenewgreenwash-2010.pdf (accessed September 10, 2020).

- Rains, S.A. 2013. The nature of psychological reactance revisited: A meta-analytic review. Human Communication Research 39, no. 1: 47–73.

- Reeves, B., L. Yeykelis, and J.J. Cummings. 2016. The use of media in media psychology. Media Psychology 19, no. 1: 49–71.

- Ryan Air. 2020. Europe’s no. 1 airline for carbon efficiency. https://corporate.ryanair.com/environment/ (accessed September 10, 2020).

- Schmuck, D., J. Matthes, and B. Naderer. 2018. Misleading consumers with green advertising? An affect-reason-involvement account of greenwashing effects in environmental advertising. Journal of Advertising 47, no. 2: 127–45.

- Seele, P., and L. Gatti. 2017. Greenwashing revisited. In search of a typology and accusation-based definition incorporating legitimacy strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment 26, no. 2: 239–52.

- Segev, S., J. Fernandes, and C. Hong. 2016. Is your product really green? A content analysis to reassess green advertising. Journal of Advertising 45, no. 1: 85–93.

- Slater, M.D. 1991. Use of message stimuli in mass communication experiments. A methodological assessment and discussion. Journalism Quarterly 68, no. 3: 412–21.

- Snow, J. 2021. Greener air travel will depend on these emerging technologies. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/greener-air-travel-will-depend-on-these-emerging-technologies (accessed July 6, 2021).

- Szabo, S., and J. Webster. 2021. Perceived greenwashing. The effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics 171, no. 4: 719–39.

- Tingley, D., T. Yamamoto, K. Hirose, L. Keele, and K. Imai. 2019. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mediation/vignettes/mediation.pdf (accessed July 6, 2021).

- Trope, Y. and N. Liberman. 2010. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol Review 117, no. 2: 440–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

- Van Liere, K.D., and R.E. Dunlap. 1980. The social bases of environmental concern: A review of hypotheses, explanations and empirical evidence. Public Opinion Quarterly 44, no. 2: 181–97.

- VietJet. 2020. Protect our planet, fly with VietJet. https://www.vietjetair.com/Sites/Web/en-US/NewsDetail/hot-deals/4241/protect-our-planet-fly-with-vietjet (accessed September 10, 2020).

- Walasek, L., S. Bhatia, and G.D.A. Brown. 2018. Positional goods and the social rank hypothesis: Income inequality affects online chatter about high- and low-status brands on twitter. Journal of Consumer Psychology 28, no. 1: 138–48.

- Wright, A.A., and J.G. Lynch. 1995. Communication effects of advertising versus direct experience when both search and experience attributes are present. Journal of Consumer Research 21, no. 4: 708–18.

- Young, M., J.E.S. Higham, and A.C. Reis. 2014. ‘Up in the air’: A conceptual critique of flying addiction. Annals of Tourism Research 49: 51–64.

- Zhao, X., X. Nan, I.A. Iles, and B. Yang. 2015. Temporal framing and consideration of future consequences: Effects on smokers’ and at-risk nonsmokers’ responses to cigarette health warnings . Health Communication 30, no. 2: 175–85.

Appendix A

Table A1. Conceptualization of greenwashing claim types in airline advertising.

Table A2. Examples and description of the used stimuli in the conditions.

Table A3. Description of measures.

Table A4. Overview of the hypotheses and analyses.

Appendix B

(under OSF)

Table B1. Pattern matrix of a principal component analysis on mediator and dependent variables using oblimin rotation.

Table B2. Correlations between items measuring the dependent variable brand evaluation.

Table B3. Randomization check.

Table B4. Manipulation checks.

Table B5. Overview of effects of the moderated mediation model.

Table B6. Means and standard deviations of mediator and dependent variables.