Abstract

Stress in patients and pre-clinical research animals plays a critical role in disease progression Activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) by stress results in secretion of the catecholamines epinephrine (Epi) and norepinephrine (NE) from the adrenal gland and sympathetic nerve endings. Adrenergic receptors for catecholamines are present on immune cells and their activity is affected by stress and the accompanying changes in levels of these neurotransmitters. In this short review, we discuss how this adrenergic stress impacts two categories of immune responses, infections and autoimmune diseases. Catecholamines signal primarily through the β2-adrenergic receptors present on innate and adaptive immune cells which are critical in responding to infections caused by pathogens. In general, this adrenergic input, particularly chronic stimulation, suppresses lymphocytes and allows infections to progress. On the other hand, insufficient adrenergic control of immune responses allows progression of several autoimmune diseases.

Introduction

Stress is an inclusive term referring to the physiological response of an organism to any one of a number of factors that disturb some aspect of homeostasis. Stress has undoubtedly been a part of human life since the very beginning of animal existence arising from, for example, pain, fear of predators or exposure to temperature extremes. “Psychological stress” has become highly prevalent in the twenty-first century and almost everyone experiences the negative impacts of being stressed. Increased chronic stress has been predominantly associated the exacerbation of many diseases. For example, it has been shown that cancer patients experience increased psychological stress and that those patients with increased stress levels have faster disease progression and higher mortality rates [Citation1]. Although acute stress is often required for survival, if present over long periods of time, chronic stress often leads to negative consequences [Citation2].

Two major pathways can be activated in response to stress, either alone or together: (1) the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis (HPA) and (2) the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). On the other hand, stress can activate the SNS which innervates the adrenal medulla to secrete epinephrine (Epi) and norepinephrine (NE) or release of NE by sympathetic nerves which innervate nearly every organ in the body [Citation3,Citation4].

The mandated housing temperatures for mice in animal facilities (22–26 °C) is a constant source source of chronic cold stress and our lab has discovered that this induces a degree of immunosuppression which is sufficient to accelerate tumour growth and metastasis. When compared to mice housed at their preferred thermoneutral ambient temperature of 30 °C, these chronically cold stressed mice show elevated levels of NE, which they use to generate heat [Citation5,Citation6]. Pharmacologic blockade of the beta-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs), which are activated by NE, reduces tumour growth rates in chronically stressed mice compared to growth rates seen in mice housed at thermoneutral temperatures. Furthermore, loss of this effect in SCID mice indicates that adrenergic signalling inhibits the anti-tumour efficacy of lymphocytes and that this suppression is reversed by β-AR antagonists (β-blockers) [Citation5].

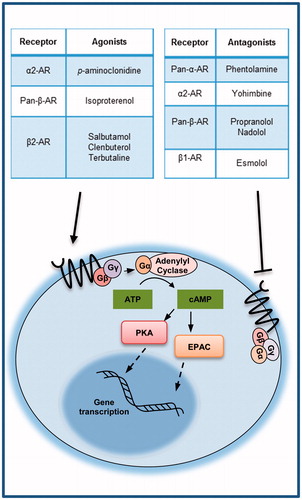

The adrenergic receptors (ARs) are a class of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) which respond primarily to catecholamines released in response to stress. They are classified into two types: the α and the β AR’s. The α and β-ARs have further subclasses which are present on different cells of the body. Lymphocytes primarily express the β2-AR. In disease conditions, changes in either the levels of receptor expression or the type of receptor on the cell play a role in regulating lymphocyte activity. The β-ARs signal via the cyclic AMP (cAMP) pathway to active gene transcription. Catecholamine binding to one of the ARs activates GPCR signalling which activates adenylyl cyclase which converts ATP to cyclic AMP. cAMP can activate downstream signalling through protein kinase A (PKA) or exchange proteins activated by adenylyl cyclase (EPAC) to activate specific transcription factors [Citation7]. Several agonists and antagonists of ARs have been developed and used in the studies described in this review (see . This brief review highlights research which demonstrates an important role of AR signalling in the risk and progression of various infections and autoimmune diseases.

Figure 1. Agonists and antagonists used in the studies described in this review (adrenergic signalling diagram modified from Cole and Sood, Clin Canc Res, 2012).

Bacterial infections

Listeria monocytogenes

Emeny et al. [Citation7] sought to determine the role of β1- and β2-AR signaling in immune responses in mice which were under physiological and psychological stress imposed by a combination of exposure to cold and restraint (acute cold restraint stress, ACRS) stress. Using both wild type (WT) and mice deficient in β1-AR (Adrb1−/−) or β2-AR (Adrb2−/−), they found that the livers and spleens of Adrb1−/− mice had a decreased burden of Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) compared to WT and Adrb2−/−. Systemic corticosterone (CORT) levels increased similarly in all mouse models after cold restraint stress (CRS), indicating that the improved response of Adrb1−/− mice was not due to altered CORT levels. They confirmed that the result was due to decreased signaling in immune cells using bone marrow chimeras. They concluded that Adrb2−/− mice showed an increased humoral-mediated immune response whereas Adrb2−/− mice showed a more robust cell-mediated immune response as evidenced by elevated footpad swelling, together indicating a role for β2-AR in suppression of cell mediated immune responses.

Cao et al. [Citation8] sought to determine the role of stress signalling by both CORT and NE in suppressing host resistance to L. monocytogenes also using a model of ACRS. Here, they report that ACRS increased serum CORT levels for 1 hour and resulted in an increased bacterial burden in the liver and spleen after intravenous (IV) L. monocytogene injection. They next inhibited the response to CORT using the inhibitor metyrapone or depleted peripheral NE using 6-OHDA (ablates sympathetic nerves) and again assessed the impact on L. monocytogenes burden. These studies revealed that peripheral NE depletion significantly improved the anti-bacterial response compared with the CORT depleted group as evidenced by a significant reduction in bacterial load in the spleen and liver in ACRS and control mice. They confirmed the role of NE-induced immune suppression by using the tricyclic anti-depressant and NE reuptake inhibitor desipramine which partially reversed the enhanced immune response in 6-OHDA treated mice.

Further studies by Cao et al. [Citation9] assessed which receptor(s) were responsible for NE induced immune suppression. Using propranolol, a pan-β-AR antagonist and phentolamine, a pan-α-AR antagonist, they showed that β-AR blockade reduced L. monocytogenes burden to levels similar to those observed in control mice, while α-AR blockade actually increased the bacterial load. They then assessed the role of β-AR signalling in the central nervous system (CNS) by comparing nadolol, a β-blocker that does not cross the blood–brain barrier to propranolol which does cross the blood–brain barrier. Here, they observed that nadolol had similar effects to propranolol indicating that the benefit of β-AR signalling was due to blockade in the periphery. They confirmed a role for the immune system by repeating these studies in SCID mice where β-blockade had no impact on bacterial load.

Miura et al. [Citation10] showed that ablating adrenergic nerves using 6-OHDA increased the production of Th1 polarizing cytokines IL-12 and TNF-α by dendritic cells, and IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion by T cells. However, they reported no impact on macrophage function, particularly phagocytosis and listericidal functions. They showed a dependence on IFN-γ for resisting L. monocytogenes infection by showing that 6-OHDA significantly improved overall survival compared with controls in WT mice but failed to provide any benefit to mice deficient in IFN-γ (IFNγ−/−) or TNF-α (TNFα−/−). They confirmed the immunosuppressive effects of adrenergic signalling by showing that adoptively transferring splenocytes from 6-OHDA treated WT mice which resisted L. monocytogenes infection conferred resistance to naive host mice.

Rice et al. [Citation11] investigated the role of β-AR signalling in the recruitment of innate immune cells to the site of a peritoneal L. monocytogenes infection. Consistent with previous work, they found that treatment with 6-OHDA reduced circulating levels of IFN-γ (an early systemic indicator of L. monocytogenes infection) correlating with reduced bacterial load in the liver. Examination of peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) from these mice revealed an increased number of activated macrophages (I-Ad+) with no change in production of protective cytokines including TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-12. However, PECs from 6-OHDA treated mice did have enhanced lytic function as evidenced by an increase in CD107b+ macrophages cells.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

This work, by Dimopoulos et al. [Citation12] investigated the role of esmolol, a β1-AR antagonist, in the progression and treatment of pyelonephritis in rabbits by multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) compared to or in conjunction with the potent antibiotic often used against antibiotic-resistant bacteria, amikacin. Treatments were started either at the time of or 90 min post infection. Following both treatment protocols, both amikacin and esmolol alone improved survival and decreased bacterial load, with an additive effect observed in the combination treatment group, indicating a role for β1-AR blockade in cases of drug-resistant P. aeruginosa infections.

The role of α-AR and β-AR signalling on cytokine production in response to P. aeruginosa infection was investigated by Straub et al. [Citation13]. Using NMRI mice which have low homeostatic levels of IL-6 and TNF-α, they determined that α-AR signalling (using p-aminoclonidine, an α-AR agonist) caused decreased IL-6 and TNF-α levels via cAMP inhibition. Further investigation into mice infected with P. aeruginosa revealed that infection caused an increase in splenic NE levels which further decreased IL-6 and TNF-α levels. However, in the case of infection, cytokine levels were mediated by β-AR blockade as opposed to α-AR blockade. Overall, this data suggests that in the presence of infection, IL-6 inhibition switches from being mediated by the α-AR to β-AR signalling pathways, whereas TNF-α was inhibited by β-AR signalling in both control and infected mice.

Salmonella typhimurium

Work by Gabanyi et al. [Citation14] studied macrophage populations residing in intestinal tissues. These authors compared the ability of lamina propria macrophages (LpMs) and muscularis macrophages (MMs), to stimulate inflammatory responses to infection. They observed dramatically different morphologies and cellular dynamics between the two macrophage populations at steady state, and this disparity increased after infection by various bacterial species. MMs were more static and had larger but less dynamic dendrite extensions than LpM. They also saw that MM populations expressed genes that were indicative of protective function while LpMs more readily expressed pro-inflammatory genes. This difference was again increased after infection with Salmonella typhimurium. MMs expressed β2-ARs to a far greater degree and were found in close proximity to extrinsic adrenergic nerves (nerve cell bodies outside of intestine). These nerves were determined to be the source of NE stimulation as opposed to myeloid cells or intrinsic neurons.

Mazloomi et al. [Citation15] investigated the potential of propranolol (pan-β-antagonist) in combination with the standard adjuvant alum, to improve vaccine responses to heat-treated Salmonella typhimurium (HTST). They observed dramatically increased levels of IFN-γ in the group that received both alum and propranolol with modest increases in IFN-γ levels in the propranolol only group. The combination therapy also improved lymphocyte proliferation, increased antibody titers (both IgG2a and IgG1 isotypes), and decreased the bacterial load in the spleen and liver. This combination of factors culminated in a drastically improved survival of animals challenged with Salmonella typhimurium that received the propranolol and alum combination compared to all other vaccination strategies.

Klebsiella pneumoniae

The role of NE signalling in the immune response to the gram-negative bacteria Klebsiella pneumoniae in a model of peritoneal infection that progressed to sepsis was examined by Seeley et al. [Citation16]. Here, 6-OHDA ablation of adrenergic nerves improved survival more than 2-fold (27% to 67%) when mice were challenged by intraperitoneal (IP) injection 4 d post 6-OHDA treatment. A role for NE was confirmed by showing that treatment with desipramine (a NE uptake inhibitor) negated the effect of 6-OHDA treatment. This change in survival was not seen when sepsis was elicited by an IV injection of LPS, indicating that 6-OHDA improved survival by enhancing the host immune response as opposed to other physiologic changes. 6-OHDA treatment increased monocyte recruitment to the infection and decreased bacterial loads throughout the mouse. All cytokines assessed remained unchanged between naive and infected mice with the exception of IL-6, which was increased. They concluded that the increased IL-6 production was likely dependent on CCL2 production which was directly suppressed by NE. NE depletion enhanced the recruitment of both Ly-6 C+ and Ly-6 C− monocytes from the spleen.

Escherichia coli

Cytokines and microorganisms are typically unable to cross the blood–brain barrier, yet their presence in the periphery correlates with the release of cytokines in the brain. How a peripheral infection causes production of cytokines in the brain is not well understood. Johnson et al. [Citation17] asked whether β-AR signalling in the brain was involved with cytokine release during peripheral Escherichia coli (E. coli) infection. In this study, isoproterenol (ISO, a β-AR agonist) and propranolol (pan-β-antagonist) were administered directly into the cisterna magna of the CNS while nadolol (a non-selective β-blocker), which does not cross the blood–brain barrier, was injected IP. Following E. coli infection, they determined that propranolol treatment of infected mice decreased IL-1β in the brain and TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β in circulation to levels similar to those observed in non-infected mice. In contrast, ISO treatment increased both central and peripheral cytokine levels in non-infected mice to levels similar to those of infected mice. They further explored the significance of β-blockade in the CNS by using the β-blocker. Surprisingly, in contrast to propranolol, nadolol actually increased cytokine levels to those achieved by direct ISO treatment to the CNS. In addition to highlighting the importance of β-blockade in clearing bacterial infection, it also provides data showing that β-blockade in the CNS can attenuate IL-1β induction.

Other bacterial infections

Recently, a study by Merli et al. [Citation18] compared the outcomes of patients admitted to a hospital for cirrhosis that was treated with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and/or β-blockers. They found that patients treated with β-blockers had a significant reduction in rates of infection compared with controls. In contrast, PPIs actually increased the risk of infection compared with controls. In addition, sepsis and infection rates were lowest in the β-blocker cohort and highest in the PPI cohort further supporting these claims. This work also showed a decrease in mortality and morbidity in those chronically treated with β-blockers, although β-blockers in this setting are typically prescribed to prevent variceal bleeding. This study shows that β-blockers could potentially improve outcomes of patients with cirrhosis by reducing the occurrence of potential life-threatening infections.

Adrenergic signalling is also involved in the development and severity of bacterial periodontal disease [Citation19]. Mice were treated with 6-OHDA and ligatures were added around a tooth to force bacterial colonisation and LPS was injected prior to collecting blood samples to stimulate the immune response. Here, 6-OHDA treatment significantly reduced bacterial damage as evidenced by a significant preservation of bone density in sympathectomised mice compared to controls. TGF-β, IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α were all increased in 6-OHDA treated mice.

Viral infections

Cytomegalovirus

CMV specific CD4+ T-cells have been shown by microarray to express high levels of β2-AR in addition to CXCR3 (indicating an effector phenotype) [Citation20]. While stress can prompt reactivation of a latent virus, possibly by Epi binding to the promoter region of CMV, β2-AR activation in antigen-specific CD4+ T cells draws them into circulation where CXCR3 expression then induces homing towards the infected site where they can kill infected endothelial cells and recruit additional immune cells. Furthermore, this study concludes that with age, cytotoxic orientation increases, while PD-1 surface expression decreases.

Herpes simplex virus

It has been reported that β2-AR signalling drives a Th2 response and suppresses the Th1 cytotoxic cell-mediated response [Citation21]. Kim et al. [Citation22] assessed the potential for salbutamol (SAL, a specific β2-AR agonist) to augment vaccines against HSV. Treatment with SAL significantly improved the survival in HSV challenged mice and dramatically drove a Th2 immune response as evidenced by high levels of HSV-specific IgG1 antibodies compared with IgG2a. SAL adjuvant also increased IgA antibodies providing additional protection against mucosal infection. Both splenocytes and lymphocytes taken from the draining nodes and spleen of mice treated with SAL plus vaccine had superior proliferative capacity in response to HSV stimulation as opposed to those receiving vaccine alone.

While generally considered immune suppressive, Kohut et al. [Citation23] provide evidence that a certain degree of adrenergic signalling by catecholamines is required to mount an anti-viral immune response. They have previously reported that extreme exercise impairs the immune response and increases susceptibility and mortality as a result of viral infection. Here, they show here that β-blockade using nadolol can induce further deleterious effects. For example the HSV-induced production of both the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and Th2 cytokine IL-10 were both further reduced by nadolol; β-blockade also reduced TNF-α secretion by alveolar cells after LPS exposure.

Emotional stress can also elicit sympathetic responses and Logan et al. [Citation24] conducted a prospective study that assessed stress and recurrence of oral HSV lesions in women. They found that Epi levels and the number of NK cells in circulation were elevated 1 week prior to oral lesion recurrence and both dropped during the week of recurrence. This was the first study to assess patterns in mood and stress and provide an explanation for the stress-induced reactivation of HSV.

The recurrence of oral HSV lesions most often occurs under conditions of immunosuppression in response to physical or psychological stressors. A study by Freeman et al. [Citation25] shows that latent HSV infections are held in check by HSV specific CD8+ T cells that reside in the trigeminal nerve (TGN). Depleting CD8+ T cells alone was sufficient to increase the HSV copy number. Using a model of restraint stress, they also observed an increased HSV copy number which was accompanied by a reduction in the number of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in the TGN. In addition, approximately 65% of CD8+ T cells in the TGN lost the ability to produce IFN-γ after restraint stress. Furthermore, exposure to stress significantly impaired the ability of virus-specific CD8+ T cells to proliferate in response to peptide exposure ex vivo.

On the other hand, Leo et al. [Citation26] indicate a role for adrenergic signalling in promoting anti-viral immunity in both the primary and memory responses to HSV infection. They show that chemical sympathectomy by 6-OHDA prior to initial inoculation with HSV suppresses the lytic functions of splenocytes. In addition, depletion of peripheral adrenergic nerves after the primary HSV infection, but before a secondary infection, also decreased the lytic function of memory cells in response to the second infection.

Influenza virus

A study by Grebe et al. [Citation27] showed that β2-AR signalling blunts CD8+ T-cell mediated anti-viral responses to influenza in vivo. Using 6-OHDA, this group showed that the frequency of effector (IFN-γ +) and viral-specific CD8+ T cells was significantly increased following loss of sympathetic, adrenergic signalling. Adoptively transferring antigen-specific CD8+ T cells from either control or sympathectomised mice into hosts showed that the suppressive effect of adrenergic signalling was not permanent in that both donors behaved the same. They confirmed the effect was CD8+ T cell-dependent using CD4+ T cell depleting strategies. Lastly, they determined that the phenomena they observed as a result of specifically blocking the β2-AR recapitulated the robust anti-viral response observed in sympathectomised mice.

Vesicular stomatitis virus

Estrada et al. [Citation28] studied the effect of β2-AR signalling on CD8+ T cell frequency and function against vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) in vivo using WT and Adrb2−/− mice. Here, they show that while there was no difference in the frequency of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells at the site of VSV infection in vivo, SAL treatment significantly reduced IFN-γ secretion by WT antigen-specific CD8+ T cells ex vivo compared to their Adrb2−/− counterparts.

Enterovirus 71

The impact of adrenergic signalling on enterovirus 71 (EV71) infection showed that patients with the most severe infections, including both autonomic dysregulation and pulmonary oedema, had significantly elevated levels of systemic catecholamines [Citation29]. Further studies showed that treatment of naive immune cells in vitro with catecholamines significantly increased their susceptibility to infection by EV7.1 In addition, infecting peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors with EV71 significantly increased their production of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β in response to NE, whereas NE had no effect on cytokine production in uninfected cells.

Parasitic infections

β-AR blockade can also improve immune responses to parasitic infections. Shahabi et al. [Citation30] sought to evaluate the potential of propranolol (pan-β-antagonist) to function as an adjuvant to a malaria vaccine targeting Plasmodium berghei (P. berghei), the protozoan causing malaria. The propranolol adjuvant was compared to the current standard adjuvant, alum, in response to vaccination. They found that propranolol increased splenocyte proliferation, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, as well as anti-P. berghei IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies indicating robust immune protection. This resulted in an increased survival of mice with minimal parasitemia in the propranolol adjuvant group compared to the alum group.

Garcia-Miss et al. [Citation31] assessed the potential role of adrenergic signalling in mounting an immune response to the protozoan Leishmania mexicana (L. mexicana). Using various drugs, such as propranolol (a pan β-AR antagonist), Clenbuterol (a β2-AR agonist), and the α2-AR antagonist yohimbine, they assessed how adrenergic signalling impacted L. mexicana infection when injected into the footpad. While none of the drugs had any effect when inoculations were done with high numbers of L. mexicana (1 × 106), propranolol showed significant efficacy in improving the immune response to lower inoculation numbers (1 × 103). More specifically, propranolol lowered footpad swelling and overall parasite burden compared with all other groups. This improved control of L. mexicana infection corresponded to increased IFN-γ expression by both splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells when compared with controls.

Machado et al. [Citation32] sought to determine the role of the autonomic nervous system in moderating the inflammatory immune response to Trypanosoma cruzi infections that ultimately manifest as Chagas disease. To do so, they carried out studies using Adrb2−/− mice and salbutamol (SAL – a β2-AR agonist). They found that survival was 100% in Adrb2−/− mice in response to infection compared to 73% in WT mice. Increased survival corresponded to decreased levels of parasites in the blood. Conversely, treating WT mice with the β-AR agonist SAL exacerbated conditions, increasing parasite burden in the blood and ultimately reducing survival compared to controls.

Interestingly, Trichinella spiralis infection in rats is was not found to be affected by β2-AR signalling [Citation33]. This study found that escalating dosage levels of SAL (2, 4, 6, 8, 10 mg/kg/d) did not impact any of the parameters measured, including tongue and muscle larva, inflammatory cytokines or specific antibody titers of various isotypes (IgM, IgA and IgE). However, while IgG titres were lower at the highest SAL dose, there was no correlation between this and infection severity.

Role of β-adrenergic signalling in autoimmunity

In contrast to much of the work in infectious diseases where β2-AR signalling is immunosuppressive, β2-AR activation on immune cells in autoimmune diseases can be stimulatory, or receptor expression and signalling can be dysfunctional altering the suppressive role of the receptor.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Ulcerative colitis (UC), a specific pathology of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), is a chronic inflammatory condition that results from aberrant and autoreactive immune cell behaviour that can cause ulcer formation in the colon resulting in poor nutrient absorption. If left untreated, this condition can progress to cancer. Based on previous observations that stress was able to increase disease severity, Langhorst et al. [Citation34] sought to determine the role of psychological stress from a neuroendocrine and immunological perspective. They compared female patients with ulcerative colitis to healthy controls and determined that CORT, NE, and adrenal corticotropic hormone (ACTH) were all lower in UC patients. There were no differences in the in the combination of PBMCs in either group. However, PBMCs from UC patients secreted significantly less IL-10 after β2-AR activation with terbutaline ex vivo compared with controls, indicating a reduced ability of UC patients to produce the suppressive IL-10 cytokine in response to β2-AR activation which likely contributes to disease exacerbations be failing to suppress excessive or unnecessary immune cell behaviour.

Other work by Deng et al. [Citation35] assessed the impact of psychological stress (chronic unpredictable stress; CUS) and physical stress (chronic restraint stress; CRS) on the severity of colitis induced by DSS infused drinking water of mice. Mice experiencing CUS with IBD had higher histological scores indicative of increased disease severity. In addition, colons were shorter and had significantly higher neutrophil infiltration. Similar effects were observed in mice experiencing CRS when compared to CUS. Moreover, inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β and IL-17α, were all significantly elevated in mice experiencing stress and IBD compared to IBD alone. However, treating mice with IBD with propranolol prior to exposure to CRS and CUS was sufficient to prevent pro-inflammatory cytokine upregulation.

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system destroys myelin in the CNS resulting in physical and psychological complications. MS is typically modelled in laboratory rodents by inducing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) by injecting one of several myelin-derived peptides [Citation36]. Work by Simonini et al. [Citation37] assessed the role of adrenergic nerves in the CNS on EAE pathology in mice. They ablated adrenergic nerves in the CNS using the neurotoxin DSP4 prior to EAE induction and compared disease symptomology with controls. Here, they observed that depleting central adrenergic nerves lowered NE levels and significantly increased the severity of EAE compared with controls. The onset of symptoms was also accelerated in DSP4 treated mice. They also showed that treating mice with L-DOPA, a NE precursor that can cross the blood–brain barrier, in conjunction with non-tricyclic NE selective reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine, was sufficient to increase CNS NE levels and alleviate EAE symptoms whereas neither was very effective when used alone. At endpoint, analysis of brain tissue revealed excessive astrocyte activation in control mice compared to NE depleted mice. Taken together, these results indicate that increasing NE levels in the CNS using anti-depressants and L-DOPA is a viable strategy for suppressing the autoimmune response and thus limiting MS symptomology.

Another study by Haerter et al. [Citation38] assessed the frequency and functionality of PBMCs in the blood of MS patients as a potential biomarker. They report a key finding that circulating lymphocytes in MS patients have a high density of both β2-ARs as well as the high-affinity IL-2 R α-chain. They observed similar findings in splenocytes from rats experiencing EAE. They report that β-AR agonists have the potential to suppress the initial acute EAE attack in rats. However, the frequency of TNF-α producing cells in the CNS, spleen, and blood of EAE infected rats eventually increases. At early stages of disease, terbutaline (a β2-AR agonist) was sufficient to suppress TNF-α production by splenocytes and macrophages ex vivo. However, this finding did not hold true after repeat exacerbations after initial disease remission. They highlight a role for SNS and NE in the pathogenesis of MS by showing that 6-OHDA sympathectomy in mice prior to induction of EAE exacerbates disease severity. In addition, 6-OHDA treatment had no effect in IFNγ−/− mice indicating a role for SNS induced dysregulation of IFN-γ in models of EAE.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic autoimmune disease of unknown aetiology that affects nearly every organ system in the body, including but not limited to skin, lungs, heart, joints and kidneys [Citation39]. It has been shown that NE is able to induce lymphocyte apoptosis independent of Fas/Fas-L interactions using fasr−/− mice and that ablation of sympathetic nerves at birth resulted in early onset of SLE as evidenced by abnormal immune responses, decreased survival and a permanent decrease in IgM production [Citation40] assessed. In addition, these authors showed a strong negative correlation between NE levels and disease progression in adult mice. They also made a unique observation in which B cell populations clustered in parts of the spleen which are highly innervated by adrenergic nerves where they are generally absent.

Pawlak et al. [Citation41] performed a study on a cohort of 51 patients with SLE who were subjected to acute psychological stress (public speaking) to investigate why psychological stress can increase disease symptoms. Blood was drawn before, 10 min into the speech and 60 min afterward to measure levels of Epi, NE and lymphocyte numbers. Ten minutes after beginning the speech, Epi was increased while NE was decreased. The greatest changes were observed in healthy controls whereas minimal changes occurred in SLE patients. The lytic function of NK cells from healthy patients could be manipulated by β2-AR activation whereas that of cells from SLE patients could not. Evaluation of β2-AR surface expression was also measured on PBMCs after stress and they observed a significant increase in β2-AR expression on healthy PBMCs whereas no changes were observed in SLE patient PBMCs. However, despite having lower β2-AR expression, ex vivo culture of PBMCs from SLE patients had a much larger reduction in TNF-α production after LPS stimulation compared with healthy controls. Together, these results identify differences in the stress-induced immune responses between these two groups.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune condition of the joints which causes severe physical pain and discomfort in response to constant joint inflammation. Using a model of complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) induced arthritis, Lubahn et al. [Citation42] assessed the role of β2-AR signalling in disease pathology and symptomology. Here, they observed that activating β2-ARs with terbutaline increased inflammation resulting in severe bone loss in addition to increasing IL-2 and IFN-γ production but decreased the proliferative capacity of T cells in the draining lymph nodes. These data show that β2-AR activation uncouples proliferation which is decreased from IL-2 production which is increased in this RA model.

Ahmed et al. [Citation43] using the pan-β-blocker carvedilol to study immune responses in CFA induced RA in female Wistar rats, found that blocking adrenergic signalling increased IL-10 levels while downregulating serum levels of TNF-α, IgG and the inflammatory C-reactive protein (CRP), all of which are typically upregulated in arthritic rats. While control animals had thickened articular cartilage, readout for arthritis induced destruction, upon histopathologic examination, β-blockade with carvedilol was sufficient to prevent tissue damage. In addition, arthritic rats showed atrophy of the spleen which was reversed with carvedilol. This data supports the idea that β-blockers can suppress inflammatory responses.

To assess the role of adrenergic signalling in a collagen type II-induced model of RA in mice, Straub et al. [Citation44] focussed on splenocytes and observed that NE caused these cells to produce high levels of TGF-β whereas IFN-γ and IL-6 levels were decreased. Conversely, β-AR blockade with propranolol prior to RA induction caused the opposite effects on cytokine production. This data shows that SNS activity in the spleen may play a critical role in controlling immune responses in the setting of RA, particularly at disease onset since there was a strong and negative correlation between splenic NE levels and disease severity.

Another study by Mao et al. [Citation45] assessed the role of restraint stress on CFA induced arthritis in both NE-competent and NE-deficient (6-OHDA treated) rats. Restraint stress increased NE levels while also exacerbating paw swelling in rats. In contrast, restraint stress did not alter paw swelling in 6-OHDA treated, NE-deficient rats. In conclusion, this study determined that NE plays a significant role in driving inflammation in RA rodent models and determined this was by induction of nitric oxide from activated macrophage, possibly explains why stress exacerbates symptoms of RA.

A second study by del Rey et al. [Citation40] assessed the ex vivo production of cytokines harvested from draining lymph nodes (dLNs) of rats with collagen type II-induced RA. They noted that cytokine levels varied with the stage of disease. IFN-γ and TNF-α progressively increased with disease severity while IL-10 levels sharply declined. They also discovered that both NE and Epi levels steadily increased with disease progression. Surprisingly, observation of the inflamed joints at day 28, the time when symptoms first appeared, revealed decreased sympathetic nerve innervation compared to earlier time points while CNS levels of NE were increased. This work suggests that NE from nerves likely plays a role in the initiation of RA.

The influence of adrenergic signalling in patients with RA was investigated by Baerwald et al. [Citation46] They assessed β2-AR expression on T cells collected from blood and synovial fluid of RA patients and that CD8 + T cells from RA patients have significantly lower β2-AR expression on their surface whereas no differences were observed on CD4 + T cells. Analysis of synovial T cells revealed even lower β2-AR expression compared to those found in blood. The authors conclude that dysregulated B2-AR expression and signalling likely contribute to RA pathogenesis.

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

In contrast to RA which typically appears first in adults, patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA; also referred to as juvenile idiopathic arthritis, JIA) are below 17 years of age. JRA fluctuates between active and inactive stages of disease. Work by Kuis et al. [Citation47] determined that NE levels were lower in JRA patients compared with controls but are higher during the activate phase of disease as evidenced by increased NE metabolites in urine. Ex vivo analysis of PBMCs from JRA patients treated with ISO (a pan-β-AR agonist) showed that β2-ARs were much less responsive in patients with active disease implying that β2-AR fails to suppress inflammation due to dysfunctional signalling. In addition, they propose that phosphodiesterase (PDE) is also likely higher in the cytoplasm of JRA patients causing rapid cAMP degradation and thus decreased PKA and CREB activity after β2-AR ligation.

Using a cold pressor test (CPT– placing hand in an ice bucket for 100 s), to assess differences between healthy and JRA patient blood at 5 and 60 min post CPT, Roupe et al. [Citation48] observed a spike in NE which quickly resolved whereas Epi levels were increased and remained elevated at all-time points. They discovered that PBMCs from JRA patients, but not healthy individuals, expressed high levels of α1-AR, especially monocytes. Ex vivo culture of monocytes from JRA patients caused significant IL-6 production compared to healthy control monocytes. They concluded that the chronic systemic inflammation experienced by JRA patients is likely due to activation of α1-AR on monocytes.

Conclusions

Stress plays a critical role in disease onset and progression. The immunosuppressive effects of the HPA axis are well established and administration of steroids is a standard therapy for a variety of indications to reduce inflammation. The role of the other arm of the stress response, the SNS, is less well understood, but it is becoming clear that catecholamines also have a potent regulatory effect on immune cells. In this short review, we have presented selected examples of how adrenergic stress impacts progression of infectious and autoimmune diseases. A robust immune response is required to clear pathogens responsible for bacterial, viral and parasitic infectious diseases. As discussed above, stress increases catecholamine release from sympathetic nerve endings, which suppresses cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells and other effector lymphocytes and thereby facilitates infectious disease progression and regulates autoimmune disease. On the other hand, suppression of β-adrenergic signalling increases immune responses, enhancing clearance of pathogens in infectious disease and exacerbating autoimmunity.

Our lab has recently examined the role of adrenergic stress in tumour growth and reported that adrenergic stress imposed by standard, moderately cool housing conditions supports tumour growth and metastasis, and suppresses the anti-tumour immune response [Citation49]. This thermal stress also elevates NE levels [Citation6] and NE elevation is responsible for suppression of the antitumor immune response [Citation5]. Treatment of tumour-bearing mice with the β-blocker propranolol reverses immunosuppression and slows tumour growth. We also showed that the resulting restoration of an ongoing anti-tumour immune response can be further enhanced by combining β-blockers with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy [Citation5]. This is similar to the situation in the infectious diseases discussed above.

On the other hand, we have also demonstrated that removal of this thermal stress by housing mice at thermoneutrality exacerbates the progression of graft vs. host disease (GVHD), a condition which is caused by undesirable activity of the immune response [Citation50]. In this case, we also found that when mice were housed at thermoneutrality, initiation of adrenergic signalling with the β2-agonist salbutamol suppressed the immune-mediated development of GVHD. These findings echo the situation observed in cases of autoimmunity.

In conclusion, it is becoming clear that adrenergic stress, by regulating the activity of immune cells, has significant potential to affect disease processes. In the future, it will be important to develop approaches for translating these findings into the clinic to regulate immune responses for the benefit of patients. Importantly, our results also highlight the fact that pre-clinical mouse models of human diseases (such as infections or autoimmunity) may be influenced by under-appreciated levels of baseline stress associated with housing conditions, such as ambient temperature.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Costanzo ES, Sood AK, Lutgendorf SK. (2011). Biobehavioral influences on cancer progression. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 31:109–32.

- Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD. (2005). Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 1:607–28.

- Brown EJ, Vosloo A. (2017). The involvement of the hypothalamopituitary-adrenocortical axis in stress physiology and its significance in the assessment of animal welfare in cattle. Onderstepoort J Vet Res 84:e1–9.

- Miller DB, O’Callaghan JP. (2002). Neuroendocrine aspects of the response to stress. Metabolism 51:5–10.

- Bucsek MJ, Qiao G, MacDonald CR, et al. (2017). Beta-adrenergic signaling in mice housed at standard temperatures suppresses an effector phenotype in CD8+ T cells and undermines checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Cancer Res 77:5639–51.

- Eng JW, Reed CB, Kokolus KM, et al. (2015). Housing temperature-induced stress drives therapeutic resistance in murine tumour models through beta-adrenergic receptor activation. Nat Commun 6:6426.

- Emeny RT, Gao D, Lawrence DA. (2007). β1-adrenergic receptors on immune cells impair innate defenses against Listeria. J Immunol 178:4876–84.

- Cao L, Filipov NM, Lawrence DA. (2002). Sympathetic nervous system plays a major role in acute cold/restraint stress inhibition of host resistance to Listeria monocytogenes. J Neuroimmunol 125:94–102.

- Cao L, Hudson CA, Lawrence DA. (2003). Acute cold/restraint stress inhibits host resistance to Listeria monocytogenes via β1-adrenergic receptors. Brain Behav Immun 17:121–33.

- Miura T, Kudo T, Matsuki A, et al. (2001). Effect of 6-hydroxydopamine on host resistance against Listeria monocytogenes infection. Infect Immun 69:7234–41.

- Rice PA, Boehm GW, Moynihan JA, et al. (2002). Chemical sympathectomy increases numbers of inflammatory cells in the peritoneum early in murine listeriosis. Brain Behav Immun 16:654–62.

- Dimopoulos G, Theodorakopoulou M, Armaganidis A, et al. (2015). Esmolol: immunomodulator in pyelonephritis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Surg Res 198:175–84.

- Straub RH, Linde HJ, Männel DN, et al. (2000). A bacteria-induced switch of sympathetic effector mechanisms augments local inhibition of TNF-α and IL-6 secretion in the spleen. FASEB J 14:1380–8.

- Gabanyi I, Muller Paul A, Feighery L, et al. (2016). Neuro-immune interactions drive tissue programming in intestinal macrophages. Cell 164:378–91.

- Mazloomi E, Jazani NH, Shahabi S. (2012). A novel adjuvant, mixture of alum and the beta-adrenergic receptor antagonist propranolol, elicits both humoral and cellular immune responses for heat-killed Salmonella typhimurium vaccine. Vaccine 30:2640–6.

- Seeley EJ, Barry SS, Narala S, et al. (2013). Noradrenergic neurons regulate monocyte trafficking and mortality during gram-negative peritonitis in mice. J Immunol 190:4717–24.

- Johnson JD, Cortez V, Kennedy SL, et al. (2008). Role of central β-adrenergic receptors in regulating proinflammatory cytokine responses to a peripheral bacterial challenge. Brain Behav Immun 22:1078–86.

- Merli M, Lucidi C, Di Gregorio V, et al. (2015). The chronic use of beta-blockers and proton pump inhibitors may affect the rate of bacterial infections in cirrhosis. Liver Int 35:362–9.

- Breivik T, Gundersen Y, Opstad PK, Fonnum F. (2005). Chemical sympathectomy inhibits periodontal disease in Fischer 344 rats. J Periodontal Res 40:325–30.

- Pachnio A, Ciaurriz M, Begum J, et al. (2016). Cytomegalovirus infection leads to development of high frequencies of cytotoxic virus-specific CD4+ T cells targeted to vascular endothelium. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005832.

- Sanders VM. (1998). The role of norepinephrine and beta-2-adrenergic receptor stimulation in the modulation of Th1, Th2, and B lymphocyte function. Adv Exp Med Biol 437:269–78.

- Kim SB, Han YW, Rahman MM, et al. (2009). Modulation of protective immunity against herpes simplex virus via mucosal genetic co-transfer of DNA vaccine with [beta]2-adrenergic agonist. Exp Mol Med 41:812–23.

- Kohut ML, Martin AE, Senchina DS, Lee W. (2005). Glucocorticoids produced during exercise may be necessary for optimal virus-induced IL-2 and cell proliferation whereas both catecholamines and glucocorticoids may be required for adequate immune defense to viral infection. Brain Behav Immun 19:423–35.

- Logan HL, Lutgendorf S, Hartwig A, et al. (1998). Immune, stress, and mood markers related to recurrent oral herpes outbreaks. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 86:48–54.

- Freeman ML, Sheridan BS, Bonneau RH, Hendricks RL. (2007). Psychological stress compromises CD8(+) T cell control of latent herpes simplex virus type 1 infections. J Immunol 179:322–8.

- Leo NA, Bonneau RH. (2000). Mechanisms underlying chemical sympathectomy-induced suppression of herpes simplex virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation and function. J Neuroimmunol 110:45–56.

- Grebe KM, Hickman HD, Irvine KR, et al. (2009). Sympathetic nervous system control of anti-influenza CD8+ T cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:5300–5.

- Estrada LD, Ağaç D, Farrar JD. (2016). Sympathetic neural signaling via the β2-adrenergic receptor suppresses T-cell receptor-mediated human and mouse CD8+ T-cell effector function. Eur J Immunol 46:1948–58.

- Liao YT, Wang SM, Wang JR, et al. (2015). Norepinephrine and epinephrine enhanced the infectivity of enterovirus 71. PLoS One 10:e0135154.

- Shahabi S, Mohammadzadeh Hajipirloo H, Keramati A, et al. (2014). Evaluation of the adjuvant activity of propranolol, a Beta-adrenergic receptor antagonist, on efficacy of a malaria vaccine model in BALB/c mice. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 13:307–16.

- Garcia-Miss Mdel R, Mut-Martin MC, Gongora-Alfaro JL. (2015). Beta-Adrenergic blockade protects BALB/c mice against infection with a small inoculum of Leishmania mexicana mexicana (LV4). Int Immunopharmacol 24:59–67.

- Machado MPR, Rocha AM, Oliveira LFd, et al. (2012). Autonomic nervous system modulation affects the inflammatory immune response in mice with acute Chagas disease. Exp Physiol 97:1186–202.

- de Waal EJ, de Jong WH, van der Stappen AJ, et al. (1999). Effects of salmeterol on host resistance to Trichinella spiralis in rats. Int J Immunopharmacol 21:523–9.

- Langhorst J, Cobelens PM, Kavelaars A, et al. (2007). Stress-related peripheral neuroendocrine–immune interactions in women with ulcerative colitis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32:1086–96.

- Deng Q, Chen H, Liu Y, et al. (2016). Psychological stress promotes neutrophil infiltration in colon tissue through adrenergic signaling in DSS-induced colitis model. Brain Behav Immun 57:243–54.

- Muller DM, Pender MP, Greer JM. (2000). A neuropathological analysis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with predominant brain stem and cerebellar involvement and differences between active and passive induction. Acta Neuropathol 100:174–82.

- Simonini MV, Polak PE, Sharp A, et al. (2010). Increasing CNS noradrenaline reduces EAE severity. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 5:252–9.

- Haerter K, Vroon A, Kavelaars A, et al. (2004). In vitro adrenergic modulation of cellular immune functions in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 146:126–32.

- Del Rey A, Kabiersch A, Petzoldt S, Besedovsky HO. (2003). Sympathetic abnormalities during autoimmune processes: potential relevance of noradrenaline-induced apoptosis. Ann NY Acad Sci 992:158–67.

- del Rey A, Wolff C, Wildmann J, et al. (2008). Disrupted brain–immune system–joint communication during experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 58:3090–9.

- Pawlak CR, Jacobs R, Mikeska E, et al. (1999). Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus differ from healthy controls in their immunological response to acute psychological stress. Brain Behav Immun 13:287–302.

- Lubahn CL, Lorton D, Schaller JA, et al. (2014). Targeting alpha- and beta-Adrenergic receptors differentially shifts Th1, Th2, and inflammatory cytokine profiles in immune organs to attenuate adjuvant arthritis. Front Immunol 5:346.

- Ahmed YM, Messiha BAS, Abo-Saif AA. (2017). Granisetron and carvedilol can protect experimental rats against adjuvant-induced arthritis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 39:97–104.

- Straub RH, Rauch L, Rauh L, Pongratz G. (2011). Sympathetic inhibition of IL-6, IFN-γ, and KC/CXCL1 and sympathetic stimulation of TGF-β in spleen of early arthritic mice. Brain Behav Immun 25:1708–15.

- Mao YF, Zhang YL, Yu QH, et al. (2012). Chronic restraint stress aggravated arthritic joint swell of rats through regulating nitric oxide production. Nitric Oxide 27:137–42.

- Baerwald CG, Laufenberg M, Specht T, et al. (1997). Impaired sympathetic influence on the immune response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis due to lymphocyte subset-specific modulation of beta 2-adrenergic receptors. Br J Rheumatol 36:1262–9.

- Kuis W, de Jong-de Vos van Steenwijk CCE, Sinnema G, et al. (1996). The autonomic nervous system and the immune system in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Brain Behav Immun 10:387–98.

- Roupe van der Voort C, Heijnen CJ, Wulffraat N, et al. (2000). Stress induces increases in IL-6 production by leucocytes of patients with the chronic inflammatory disease juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a putative role for α1-adrenergic receptors. J Neuroimmunol 110:223–9.

- Kokolus KM, Capitano ML, Lee CT, et al. (2013). Baseline tumor growth and immune control in laboratory mice are significantly influenced by subthermoneutral housing temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:20176–81.

- Leigh ND, Kokolus KM, O’Neill RE, et al. (2015). Housing temperature-induced stress is suppressing murine graft-versus-host disease through beta2-Adrenergic receptor signaling. J Immunol 195:5045–54.