Abstract

Background: Surgery constitutes the standard approach for abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE), but is invasive. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation is effective and safe for the treatment of AWE, but no study has compared HIFU and surgery.

Objective: To report our experience about the benefits and adverse events of surgery compared to HIFU for the treatment of AWE.

Methods: This was a retrospective study of 54 consecutive Chinese women with AWE after cesarean section treated at the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (China) between January 2012 and December 2014. The patients underwent surgery (n = 29) or HIFU (n = 25). The technical success rate, adverse events, and recurrence were assessed.

Results: The technical success rate was 100% in both groups. The complete remission rate was 92.0% (23/25) in the HIFU group, and 100% (29/29) in the surgery group. Numeric rating scale (NRS) scores after HIFU were significantly improved from 6.9 to 0.3.During the median follow-up period of 32 months (range, 19–46 months), the durations of pain relief were 29.7 ± 12.6 months and 25.0 ± 13.5 months in the surgery and HIFU groups, respectively (p = .337). Three patients (10.7%) experienced pain recurrence in the surgery group, and two (8.0%) in the HIFU group. Major adverse events occurred in four (13.8%) and one (4.0%) patients in the surgery and HIFU groups, respectively (p > .05).

Conclusions: HIFU appears to be beneficial for the treatment of AWE, and may reduce adverse events. Compared with surgery, HIFU does not induce blood loss or tissue defects.

Introduction

Currently, surgery is the first choice for the management of abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) [Citation1,Citation2]. Medical therapy remains controversial because of its short recurrence-free survival after drug withdrawal. Surgical resection has an effective cure rate of 95% but usually requires radical resection that includes the lesions and surrounding fibrous tissues with a negative margin of at least 5 mm [Citation3]. For large lesion defects of the abdominal wall or fascia, meshes or flap transplantation may be needed to strengthen the abdominal wall [Citation1,Citation2]. Because of its invasive nature, some women are reluctant to choose surgery. Therefore, an effective therapy with minimal invasiveness may be of value for the management of AWE.

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation is a conformal thermal ablation technique that causes coagulation necrosis of the target tissues, without damaging the surrounding tissues and those in the acoustic pathway. Several studies have shown that HIFU ablation therapy is safe and effective for the treatment of uterine myoma, adenomyosis, and placenta accreta [Citation4–6]. In 2011, Wang et al. [Citation7] showed that HIFU is effective and safe for the treatment of AWE, and suggested HIFU as a new and effective therapeutic tool for AWE.

Nevertheless, the comparative benefits of surgery and HIFU in the treatment of AWE at the cesarean section scar have not been previously reported. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to report our experience about the benefits and adverse events of surgery compared to HIFU for the treatment of AWE.

Subjects and methods

Study design and patients

This was a retrospective cohort study of consecutive Chinese women with cesarean section and subsequent AWE, treated at the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (China) between January 2012 and December 2014. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University, and was carried out in accordance with approved ethical guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to treatment.

According to the treatment received, the patients were divided into the surgery and HIFU groups. The diagnostic criteria for AWE were [Citation2,Citation7]: (1) women of reproductive age with a history of abdominal surgery such as cesarean section, endometriosis, etc.; (2) masses or nodules around the abdominal incision; (3) masses or nodules accompanied with pain and/or tenderness during menstrual cycles; (4) mass size varying with the menstrual cycle, often large before menstruation and reduced thereafter; and (5) ultrasound showing hypoechoic irregular nodules near the scar. In the surgery group, the diagnosis was confirmed by postoperative pathology. In the HIFU group, hypoechoic nodules on the abdominal wall under or close to the incision scar were detected using the guiding ultrasound of the HIFU system, and the acoustic pathway was safe in the preoperative simulation location. For the surgery group, patients with hypertension, heart disease and other systemic diseases were excluded. For the HIFU group, patients unable to communicate with the physicians were excluded. Baseline characteristics were collected from medical records.

Surgery

Before surgery, lesion number, size, and location were evaluated by B-mode ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Surgery was performed under general anesthesia or continuous epidural anesthesia, with the patient in the supine position. The original cesarean scar was usually selected for a fusiform or transverse incision. If the mass was >5 cm away from the scar, a new incision was made at the location of the mass. The lesions and 5–10 mm of the surrounding normal tissue were removed. The wound was sutured layer by layer. If the tissue defect was too important, meshes were used for repair, based on the surgeon’s experience. The amounts of intraoperative bleeding and all adverse events were recorded. All surgeries were performed in the non-menstrual period by the same team of attending physicians, each with at least 5 years of experience.

HIFU

Before HIFU, lesion number, size and location were evaluated by B-mode ultrasound and MRI, as well as the distance from lesion margin to skin surface. The distances from the superficial and deep areas of the lesion to skin surface were at least 5 mm and 15 mm, respectively. Hair in the acoustic pathway was removed and the skin was degreased and degassed. The day before the procedure, the patients took a liquid diet and cleansing enema in the morning. A urinary catheter was placed before HIFU. A single session of HIFU ablation was performed using the model JC Focused Ultrasound Therapeutic Unit (Chongqing Haifu Medical Technology Co., Ltd. Chongqing, China) with a therapy transducer focal region of 1.5 × 1.5 × 8 mm, under intravenous conscious sedation with fentanyl (0.8–1 μg/kg) and midazolam hydrochloride (0.02–0.03 mg/kg). The patients were in the prone position with the lower abdomen in a water bag filled with 10–15 °C degassed water. The target areas were located on the top of the ultrasound transducer in the water bag. Ultrasound guiding was used to orientate the probe on the AWE. The ablation coverage planning was based on 3-mm interlayer spacing. Power was set at 100 W and 1-s sonication was used to assess patient tolerance. Then, the power was increased gradually to 200 W. During the treatment, the focus position was monitored through intraoperative real-time imaging, with energy control employed to ensure the safety of incision scar tissues. Sonication covered the lesions according to a point-to-point and slice-to-slice pattern. After the guiding ultrasound showed that the treated area covered the planned ablation area, sonication was considered completed. After HIFU, the patients were maintained in the therapeutic position for 30 min, which allowed to effectively cool the topical region with 10–15 °C circulating degassed water to avoid delayed thermal injury. Contrast enhanced ultrasound was used to determine the non-perfusion region in the lesions. All adverse events were recorded. All HIFU treatments were performed in the non-menstrual period by two attending physicians, each with at least 5 years of experience.

Success assessment

For surgery, the lesions and 5–10 mm of the surrounding normal tissue were removed. Technical success was considered when postoperative pathological examination revealed surgical margins free from implanted lesions.

For HIFU, technical success was defined as the guiding ultrasound showing that the treated area (increased gray scale signal) covered the planned ablation area, and in the presence of non-perfusion volume covering >80% of the lesions according to contrast-enhanced ultrasound or MRI.

Clinical evaluation

Complete remission was defined as the complete relief of pain and disappearance/shrinking of the masses. Clinical effectiveness was defined as relief of cyclic pain. The pain degree was assessed with numerical rating scales (NRS). Recurrence was defined as appearance or aggravation of cyclic pain, and/or new masses, and/or primary masses once reduced but now enlarged again in the original treatment region. Patients with recurrence would be enrolled in recurrence and re-intervention analysis. For example, HIFU group patients who underwent additional surgery or HIFU after recurrence would be included in recurrence and re-intervention analysis rather than the surgery or HIFU group. Follow-up was conducted by telephone and censored in July 2016.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and analyzed by Student-t test. The chi-square test or the Fisher exact test was used to assess categorical variables, which were expressed as frequency and percentage. p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Fifty-four patients were included: 29 in the surgery group and 25 in the HIFU group. The mean age was 32.0 ± 4.1 years. All patients had a history of cesarean section prior to the onset of AWE. The duration from the last surgery to clinical symptoms of AWE ranged from 1 month to 14 years (mean of 35.3 ± 31.0 months). Fourteen patients had received treatment before this procedure, including GnRHa, gestrinone, and surgery. All patients had masses around the previous cesarean section scars. The mean size of the masses was 3.0 ± 1.1 cm. Pain in the mass area was reported by 50 (92.6%) patients, and 48 of them (96%) had cyclic pain associated with menstruation. No significant differences were observed between the two groups(all p > .05) ().

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Technical success

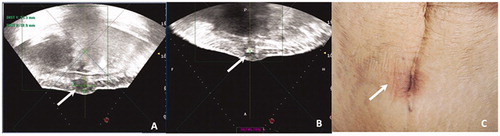

Treatment was successful in all 54 patients. In the surgery group, 12 patients (41.4%) had to be operated using new incisions and two received mesh support repair of a large tissue defect after excision. The mean operative time was 56 ± 46 min, with a bleeding volume of 49 ± 80 ml. In the HIFU group ( and ), the mean treatment time was 60 ± 64 min, including a sonication time of 287 ± 211 s. The mean hospital stay (including preoperative examinations, surgical treatment or HIFU, and postoperative recovery) was 6.7 ± 3.3 days in the surgery group, which was significantly longer than that of the HIFU group (4.4 ± 2.3 days, p = .007). The total direct medical cost (including examinations, treatments, drugs, etc.) in the surgery group averaged 2101 RMB, and were higher than those of the HIFU group, but the difference was not significant (p = .487) ().

Figure 1. Ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging (from the guiding ultrasound device of the high-intensity focussed ultrasound[HIFU] unit) in a 36-year old woman with abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE). (A) Before HIFU, a hypoechoic nodule (25 × 20 mm) between the subcutaneous fat layer and rectus abdominis (distance from skin surface, 5 mm) (white arrow). (B) Before HIFU, the nodule was enhanced oncontrast-enhanced ultrasoundafter contrast agent injection (white arrow). (C) One day after HIFU, the nodule was ablated with complete absence of perfusion (white arrow), and cyclic pain disappeared. The nodule disappeared and no recurrence occurred during the 3-year follow-up.

![Figure 1. Ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging (from the guiding ultrasound device of the high-intensity focussed ultrasound[HIFU] unit) in a 36-year old woman with abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE). (A) Before HIFU, a hypoechoic nodule (25 × 20 mm) between the subcutaneous fat layer and rectus abdominis (distance from skin surface, 5 mm) (white arrow). (B) Before HIFU, the nodule was enhanced oncontrast-enhanced ultrasoundafter contrast agent injection (white arrow). (C) One day after HIFU, the nodule was ablated with complete absence of perfusion (white arrow), and cyclic pain disappeared. The nodule disappeared and no recurrence occurred during the 3-year follow-up.](/cms/asset/2c392334-b7c6-41c7-b352-6515e6b27c21/ihyt_a_1511836_f0001_c.jpg)

Figure 2. Ultrasound and skin imaging in a 35-year old woman with endometriosis of the abdominal muscle layer. (A) Before HIFU, sagittal guided ultrasound showed a low echogenic nodule of approximately 33 mm in the right subcutaneous muscle layer of the abdominal wall incision. Distances from the superficial and deep areas of the lesion to skin surface were 6 mm and 29 mm, respectively. (B) The bladder was filled with 400 ml normal saline to push the intestine behind the lesion. During the operation, ultrasound energy of fixed-point emission was 12000 J, and the focus position showed a massive hyperechoic change. There was no significant echo change in the superficial tissue of the lesion. (C) After HIFU, skin surface was slightly swollen and the skin was intact.

Table 2. Technical success rates and medical cost.

Adverse events

Minor adverse events occurred in seven (28.0%) patients of the HIFU group, including two with hematuria and five with orange peel skin appearance. Haematuria was likely associated with injury of the urinary tract mucosa during the catheterization process. The symptoms were relived spontaneously after the patients were asked to drink more water for increased urination. In patients with orange peel skin appearance, the lesions were located within the fat layer. This condition might have been caused by local coagulative necrosis of endometriotic lesions after HIFU treatment, which results in obstructed subcutaneous lymph vessels, causing lymphostasis and dermal edema. This subsequently leads to orange peel skin appearance, which was improved after local cold compression therapy. Meanwhile, there was no minor adverse event in the surgery group. Major adverse events attributable to treatment occurred in one (4.0%) patient in the HIFU group and four (13.8%) in the surgery group. One patient in the HIFU group had skin burns. The four adverse events in the surgery group included lung infection and delayed incision healing ().

Table 3. Adverse events in the surgery and HIFU groups.

Clinical evaluation

The follow-up rate was 98.2% over a median of 32 (range, 19–46) months. Only one patient was eventually lost to follow-up in the surgery group, in which the complete remission rate was 100%, with pain completely relieved at the first menstruation after surgery. In the HIFU group, the complete remission rate was 92.0%. All patients showed cyclic pain relief within a median time of 30.6 months, and 23 patients achieved complete pain relief from first menstruation to 23 months after the procedure. NRS scores were reduced from 6.9 to 0.3 at the last follow-up. Partial response was observed in two patients, in whom NRS scores were reduced from 8 to 2 and from 7 to 5, respectively. The masses shrank or disappeared in 24 patients, but the mass size did not change in one patient after HIFU ().

Table 4. Clinical evaluation in the surgery and HIFU groups.

Recurrence and re-intervention

The recurrence rates in the surgery and HIFU groups were 10.7% and 8.0%, respectively (p = 1.000). In the surgery group, three patients had symptoms of recurrence at 3, 12, and 20 months after surgery, respectively, presenting cyclic and aggravating pain. In the HIFU group, two patients experienced symptoms of recurrence at 5 and 6 months after HIFU, respectively, presenting aggravating cyclic pain with increasing mass volume. One received HIFU re-treatment after 8 months, and no recurrence was found during the 18-month follow-up.

Four patients were not included in recurrence analysis because they only showed temporary cyclic pain in the treated areas, with symptoms alleviated spontaneously without re-intervention in the follow-up period. Specifically, three patients experienced cyclic pain at 7, 12, and 22 months after surgery, respectively, in the surgery group; pain was sustained for 3–4 months, with subsequent spontaneous relief. In the HIFU group, one patient experienced cyclic pain 6 months after treatment; pain was sustained for 7 months, with subsequent spontaneous relief.

Discussion

Surgery constitutes the standard approach for AWE, but is invasive [Citation1,Citation2]. HIFU ablation is effective and safe for the treatment of AWE [Citation7], but no previous study has compared HIFU and surgery. Therefore, this study aimed to report our experience about the benefits and adverse events of surgery compared to HIFU for the treatment of AWE. The results suggested that HIFU appears to be beneficial for the treatment of AWE, with few adverse events. Compared with surgery, HIFU does not induce blood loss or tissue damage.

Although AWE at the cesarean section scar is a benign disease, it has some neoplastic characteristics such as stromal invasion and lymphatic spread to distant organs [Citation8]. The repeated cyclic hemorrhage of the lesions causes localized fibrous tissue hyperplasia, and as the disease progresses, the lesions involve wider and deeper tissue areas, and even infiltrate the peritoneum. Furthermore, case reports about malignant endometriosis are not so rare, and its malignant transformation rate is about 0.75% [Citation9–11]. Therefore, endometriosis should be diagnosed and treated as soon as possible. Management tools include medication and ethanol injection under ultrasound guidance [Citation12], but surgery remains the first option [Citation1,Citation2]. Nevertheless, a study by Wang et al. [Citation7] showed that ultrasound-guided HIFU ablation appears to be safe and effective for the treatment of AWE. The high intensity ultrasound energy is focused on target tissues and induces coagulation necrosis by transient high temperature (60–100 °C) and cavitation [Citation13]. The target lesion is ablated, but the acoustic pathway is preserved.

Nevertheless, HIFU therapy for AWE remains in its preliminary stage. To avoid affecting the skin and underlying abdominal organs, the depth of invasion has to be evaluated by imaging, and complete ablation can then be achieved without serious complications. The two groups were comparable for age, BMI, preoperative pain, number and size of masses, adjuvant preoperative therapy, previous surgical history, and recurrence time after surgery. In the surgery group, lesions involving the anterior sheath occurred in all patients, while these lesions represented 76.0% in the HIFU group. In addition, 13.7% of lesions in the surgery group involved the peritoneum, compared with 0% in the HIFU group. As a traditional method, surgery can remove the mass under direct vision, and the technical success rate was high (100%), even for lesions involving the deep peritoneum, although patch repair was needed in some cases. Although the depth of invasion was different between the two groups, HIFU therapy was associated with less major adverse events compared with surgery. There was one case of skin burns. Nevertheless, lesion infiltration is an important factor for skin or deeper organ damage, and should be adequately verified during the pre-HIFU process.

Scars are sensitive to ultrasound, and those in the acoustic pathway of ultrasound ablation are likely to overheat or sustain damage due to the difference in absorbed energy. In most cases, scars even block acoustic beams from entering the body. Hence, it is important to protect scar tissues. In the treatment system and plan adopted in this study, strict attention was paid to protect scars from damage during patient screening, preoperative preparation, intraoperative monitoring and postoperative care. Protective measures for skin scars were as follows: (1) Preoperatively, the distance between the superficial area of the lesion and skin surface was measured by ultrasound and MRI, ensuring that it was not below 5 mm. It has been confirmed based on breast cancer treatment regimen using the therapeutic system in this study that a distance of 5 mm is safe under close monitoring. (2) Preoperative routine local skin preparation, degreasing, and degassing also help prevent local overheating due to increased reflective interface. (3) Circulating degassing water at low temperature (10–15 °C) is considered a coupling medium to lower skin temperature in time, to avoid overheating associated with heat accumulation. (4) In focused ultrasound ablation, radiation emission was controlled by a low-power (100–200W) and short-time sonication (1 s) scheme, and the extent of hyperechoic regions formed by heat-related necrotic tissues was closely monitored in real time, which enabled timely irradiation termination and effective prevention of scar overheat. (5) After HIFU, the patients were maintained in the therapeutic position for 30 min, which allowed to effectively cool the tropical region with low temperature water to avoid delayed thermal injury.

The main complaint associated with AWE is a mass and local cyclic pain. In the present study, surgery was superior to HIFU in terms of complete remission (100% versus 92.0%). Although 8.0% patients did not achieve complete remission in the HIFU group, clinical effectiveness was satisfactorily obtained in all patients. Regarding the length of hospital stay, the HIFU group was superior to the surgery group. Wang et al. [Citation7] reported that after ablation of the lesions and 1.0 cm of the surrounding tissue, the clinical symptoms of all cases were relieved during the 31-month follow-up, and the masses disappeared in all patients. The 90.0% ablation rate may be responsible for the two cases of incomplete pain relief in the present study. It is reasonable to assume that the therapeutic effects and safety could be gradually improved as case selection is further standardized, treatment parameters are gradually optimized, therapeutic experience accumulates, and the ablation range expands to the scope of surgical resection.

In the present study, the recurrence rates were 10.7% and 8.0% in the surgery and HIFU groups, respectively, during the 46 months of follow-up. Some patients experienced transient local cyclic pain for some months until spontaneous relief. Horton et al. [Citation3] reported in a systematic review a recurrence rate of 4.3% among 445 patients after surgery. Yan et al. [Citation9] reported a recurrence rate of 7.5% among 227 patients over a median follow-up of 35.2 months. These recurrence rates are lower than in the present study, which might be related to incomplete excision in some patients whose lesions were involved in rectus abdominis and even the peritoneum. For HIFU, Wang et al. [Citation7] reported that no patient experienced recurrence during a median follow-up of 18.7 months, which was better than that found in the present study over a 30.6-month follow-up. In order to reduce the possibility of recurrence and improve the curative rate, large-scale clinical trials and long-term follow-up are needed. In addition, a feasibility study of HIFU for relapses is necessary.

Other non-surgical treatment modalities have been tested for the treatment of AWE. Indeed, radiofrequency ablation [Citation14] and cryoablation [Citation15–17] have shown promising outcomes. Nevertheless, those modalities have to be compared with surgery and HIFU in order to determine the most optimal approach. Similar to HIFU in the present study, cryoablation leads to shorter hospital stay, lower rate of complications, and similar effectiveness compared with surgery [Citation16].

The present study is not without limitations. Sample size was relatively small, and all subjects were from a single center. There was no randomization, and HIFU was performed in selected cases. At our hospital, during the study period, only the patients undergoing surgery for AWE received a postoperative pathology diagnosis. The patients scheduled for HIFU were diagnosed according to the criteria presented in the manuscript and MRI examination, without pathological confirmation. Additional studies are necessary to examine the real value of HIFU compared with surgery for AWE at the cesarean scar.

Conclusions

For the treatment of AWE, compared with surgery, HIFU displays clinical benefits and may have less adverse events. As a new non-invasive treatment, HIFU could be more readily accepted by patients, but a prospective randomized controlled trial is needed to verify its efficacy and safety.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants for their time and commitment to this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ding Y, Zhu J. A retrospective review of abdominal wall endometriosis in Shanghai, China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121:41–44.

- Zhang J, Liu X. Clinicopathological features of endometriosis in abdominal wall-clinical analysis of 151 cases. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2016;43:379–383.

- Horton JD, Dezee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon's perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg. 2008;196:207–212.

- Chen J, Li Y, Wang Z, et al. Evaluation of HIFU Ablation for Uterine Fibroids: an IDEAL Prospective Exploration Study. BJOG. 2017;125:354–364.

- Zhou M, Chen JY, Tang LD, et al. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for adenomyosis: the clinical experience of a single center. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:900–905.

- Bai Y, Luo X, Li Q, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound treatment of placenta accreta after vaginal delivery: a preliminary study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:492–498.

- Wang Y, Wang W, Wang L, et al. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for abdominal wall endometriosis: preliminary results. Eur J Radiol. 2011;79:56–59.

- Siufi Neto J, Kho RM, Siufi DF, et al. Cellular, histologic, and molecular changes associated with endometriosis and ovarian cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:55–63.

- Yan Y, Li L, Guo J, et al. Malignant transformation of an endometriotic lesion derived from an abdominal wall scar. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115:202–203.

- Liu H, Leng J, Lang J, et al. Clear cell carcinoma arising from abdominal wall endometriosis: a unique case with bladder and lymph node metastasis. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:51.

- Ruiz MP, Wallace DL, Connell MT. Transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis to clear cell carcinoma. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2015;2015:123740.

- Bozkurt M, Cil AS, Bozkurt DK. Intramuscular abdominal wall endometriosis treated by ultrasound-guided ethanol injection. Clin Med Res. 2014;12:160–165.

- Hill CR, ter Haar GR. Review article: high intensity focused ultrasound-potential for cancer treatment. Br J Radiol. 1995;68:1296–1303.

- Carrafiello G, Fontana F, Pellegrino C, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of abdominal wall endometrioma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:1300–1303.

- Dibble EH, D'Amico KC, Bandera CA, et al. Cryoablation of Abdominal Wall Endometriosis: A Minimally Invasive Treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209:690–696.

- Maillot J, Brun JL, Dubuisson V, et al. Mid-term outcomes after percutaneous cryoablation of symptomatic abdominal wall endometriosis: comparison with surgery alone in a single institution. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:4298–4306.

- Cornelis F, Petitpierre F, Lasserre AS, et al. Percutaneous cryoablation of symptomatic abdominal scar endometrioma: initial reports. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37:1575–1579.