Abstract

Objective: Despite a high response rate to first-line therapy, prognosis of epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) remains poor. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the frequency of long-term survivors and to identify the prognostic factors associated with long-term survival in a French cohort of 566 patients.

Methods: Patients treated with cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for EOC in 13 French centers between 1991 and 2010 were included. Long-term survivors were defined as patients who survived more than 5 years after HIPEC and CRS, irrespective of relapse.

Results: Seventy-eight long-term survivors were analyzed. The median follow-up was 74 months. Median age at the time of first HIPEC was 55.4 years (range [22.6–77.6]. Seven patients had advanced EOC and 71 patients had recurrent EOC (37 patients had platinum-resistant EOC and 32 had platinum-sensitive disease). More than half of the long-term survivors had high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC). In univariate analysis, age ≥50 years (p = .004), peritoneal cancer index (PCI) ≤ 8 (p = .049) and CA-125 < 100 (p = .02) were associated with long-term survival. There was a trend towards an association between higher CC-score and long-term survival (p = .057).

Conclusion: Age ≥50 years, PCI ≤8 and CA125 < 100 were associated with long-term survival in univariate analysis. There was a trend towards the significance of CC-score. Platinum-status was not associated with long-term survival.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecological cancer in Western Europe [Citation1]. Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) has a poor outcome, mainly because it is often diagnosed at an advanced stage (70.0%) [Citation2]. For such patients, cytoreductive surgery (CRS) followed by platinum-based chemotherapy is considered the standard therapy [Citation3]. However, despite high initial response rates, most ovarian cancer patients will eventually relapse and require further treatment. Those who relapse more than six months after completion of a platinum-based chemotherapy are considered ‘platinum-sensitive’ and those who relapse before are considered ‘platinum-resistant’ [Citation4]; the latter have poor prognosis (6.7 months progression-free survival, PFS, in the Aurelia trial) [Citation5].

Encouraging survival results in recurrent EOC were reported in a retrospective French multicenter cohort of consecutive patients treated with CRS and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) [Citation6]. The median overall survival (OS) for recurrent EOC was 45.7 months and, among patients with completeness of cytoreduction score of zero (CC-0) there was no significant difference in OS between those with platinum-resistant (51.6 months) and platinum-sensitive recurrence (47.2 months) [Citation6].

Limited data is available regarding long-term survivors, especially in recurrent EOC, mainly because such patients are rare. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the frequency of long-term survival and to identify the prognostic factors associated with long-term survival in a French cohort of 566 patients.

Patients and methods

Patient population

The population analyzed herein has been previously reported [Citation6]. Briefly, patients treated with CRS and HIPEC for EOC in 13 French centers between 1991 and 2010 were included. Inclusion criteria were: age from 18 to 75 years with incident advanced EOC or with recurrent EOC (either platinum-resistant or platinum-sensitive) considered fit for surgery. Herein, long-term survivors were defined as patients who survived more than 5 years after HIPEC and CRS, irrespective of relapse [Citation7].

Study design

The data collected in the study included details of the patient’s status before CRS and HIPEC, including age, extent of peritoneal carcinomatosis and previous treatment with systemic chemotherapy. Information collected regarding the combined procedure included date, peritoneal cancer index (PCI), completeness of cancer resection score (CC-score), simultaneous resection of primary tumour or liver metastasis, number of organ resections, presence or absence of lymph node metastases, modalities of HIPEC (duration, drugs, closed or open procedures, temperatures) and treatment with adjuvant systemic chemotherapy. Follow-up data included the status of the patient (alive with disease, alive without disease, dead with disease, dead without disease), the site and date of initial relapse and all other sites of relapse.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was a retrospective post-trial ad-hoc analysis. Descriptive analyses of long-term survivor initial characteristics and first procedure were performed. Categorical variables were described in terms of frequency and percentages. The distributions of continuous variables were described with median and range.

OS was defined as the interval of time from the first HIPEC to the date of death or last follow-up, whichever came first. Disease-free survival was defined as the interval of time from first HIPEC to next relapse or last follow-up. Patients with CC-2 resections were considered as an immediate relapse and were not included in the disease-free survival analysis.

Median survival times and survival rates were computed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Hazard-ratios and p values were obtained using the Cox proportional hazards model. Influence of baseline risk factors was assessed using univariate Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for the institution.

Compliance with ethics

Since patient management was not modified, according to French law (n°2004–806, 9 August 2004) in force at the time of study initiation, this study did not require to be approved by a research ethics committee.

Results

Patient characteristics and treatment

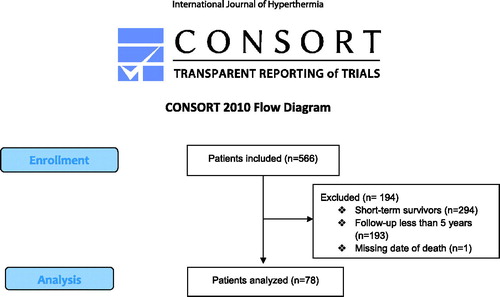

Overall, 566 patients were included between 1991 and 2010. There were 92 (16.3%) patients with advanced EOC who received first-line therapy and 474 (83.7%) with recurrent EOC – of whom 223 (47.4%) had platinum-resistant and 247 (52.6%) platinum-sensitive disease. For those with advanced EOC, median overall survival was 35.4 months (95%CI [29.7–42.7]); for recurrent platinum-resistant EOC median overall survival was 48.0 months (95%IC [38.6–56.0]), and for platinum-sensitive EOC this was 42.2 months (95%IC [37.6–52.1]). A total of 194 patients were excluded because of incomplete data (1 missing date of death, 193 follow-up <5 years). There were 78 long-term survivors (13.8%; ); median follow-up was 74 months. The characteristics of long-term survivors are presented in . Median age at the time of first HIPEC was 55.4 years [22.6–77.6]. Seven patients had advanced EOC and 71 patients had recurrent EOC (37 patients had platinum-resistant EOC and 32 had platinum-sensitive disease). Almost two-thirds of long-term survivors (62.8%) had high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC).

Table 1. Characteristics of long-term survivors.

Treatments and details of procedures are presented in . Previous CRS was performed on the majority of patients (n = 70, 89.7%). Cytoreduction was frequently incomplete (53.8%) or not performed (10.3%). When addressed to our center, CC-0 score was obtained by 76.9% of the patients.

Table 2. Treatments and detail of procedures for long-term survivors.

Survival and prognostic factors

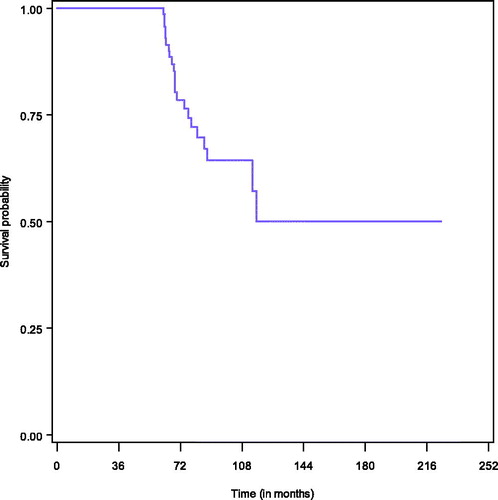

Survival among long-term survivors is presented in . Among long-term survivors, 22 died (28.2%) mainly because of disease progression (18/22, 81.8%). Median OS was not reached. For the estimation of progression-free survival, 8 patients were excluded because of suboptimal surgery (CC-2), and in total 50 patients relapsed within 5 years. Median PFS was 31.5 months (95%CI [17.5–44.4]). The PFS at 1 year was 77.5%, at 3 years it was 43.7%, and at 5 years it was 32.3%.

In univariate analysis, age ≥50 years (p = .004), peritoneal cancer index (PCI) ≤ 8 (p = .049), and CA-125 < 100 (p = .02) were associated with a long-term survival. There was a trend towards an association between higher CC-score and long-term survival (p = .057); platinum-status was not associated with long-term survival ().

Table 3. Mortality risk factors, univariate analysis.

Discussion

This retrospective, multicenter study analyzed 78 patients with advanced and recurrent platinum-resistant or platinum-sensitive EOC with long-term survival (defined as OS >5 years). We found age ≥50 years, PCI ≤8, and CA125 < 100 to be significantly associated with long-term survival in univariate analysis, and a trend towards a significant association with increased CC-score. CA125 < 100 was found to be associated with long-term survival although there were many missing data, which suggests a strong association. Elevation of CA125 level and PCI correlate with advanced and aggressive disease. In the present study, initial aggressiveness of a tumor and its extent seem to be a more powerful predictive factor for long-term survival than aggressive surgical resection (CC-score) for which the association was not statistically significant. This is important because during the platinum era maximal cytoreduction is one of the most powerful determinants of cohort survival among patients with stage III or IV ovarian carcinoma [Citation3]. Indeed, complete cytoreduction after primary CRS [Citation8–10], complete response after first-line treatment [Citation11] and tumor debulking by experienced gynecological oncologic surgeons are associated with an improved OS in incident advanced EOC. However, in recurrent EOC which concerned the majority of long-term survivors, the importance of therapeutic success of CRS or HIPEC may have survival benefits but data is not as obvious as in first-line [Citation12–18]. The ongoing DESKTOP III trial will prospectively assess the role of secondary CRS in patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. This important trial should provide answers to several key questions regarding the management of recurrent EOC, notably if secondary CRS results in better outcomes than second-line chemotherapy; the results are expected in December 2019. Concerning HIPEC, two randomized trials are ongoing: one in France sponsored by the Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer (CHIPOR trial) and one in Rome [Citation19]. Recently, a multicenter, open-label, phase III trial randomly assigned 245 patients who had at least stable disease after three cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel to undergo interval cytoreductive surgery either with or without administration of HIPEC with cisplatin [Citation20]. Among patients with stage III epithelial ovarian cancer, the addition of HIPEC to interval cytoreductive surgery resulted in longer recurrence-free survival and overall survival than surgery alone and did not result in higher rates of side effects. Further investigations should be performed in order to determine whehter patient- or disease-related factors are associated with improved survival. This could be of clinical significance and help the therapeutic decision-making.

The most important finding herein is that there was no significant difference in overall survival between patients with platinum-resistant and platinum-sensitive status as the number of patients was well balanced among long-term survivors. Spiliotis et al. found the same result in a randomized phase III study evaluating HIPEC in advanced EOC (stages IIIC and IV) in the HIPEC group but not in the control group [Citation21]. Possible explanations include the antitumoral effect of hyperthermia through the activation of heat-shock proteins and of oncothermia through epigenetic alterations [Citation22,Citation23]. We should not therefore, underestimate the benefits of HIPEC. Moreover, the validity and clinical relevance of the definition adopted by the scientific community might be questioned. Maurie Markman, himself, criticized this definition of reporting three patients responding to platinum-based therapy while being classified as platinum-resistant. Yet, surgery was not performed on these three patients or at least was suboptimal. Persistent ovarian cancer could contribute to the heterogeneity of this platinum-resistant disease. To minimize this heterogeneity, classification of recurrent disease should take into account the quality of CRS.

The majority of reported data regarding long-term survivors are in the first-line setting. The factors reported to be associated with long-term survival are: grade, stage, primary mass size tumor [Citation24], the absence of ascites [Citation11], normal CA125 level before platinum therapy, negative Ki-67 expression, underexpression of p53 [Citation25], age <40 years [Citation26], performance status (PS), tumor histology [Citation27], and stage IIIC due to nodal involvement [Citation28] which is consistent with the results herein. At the molecular level, patterns of gene expression and genomic instability distinguish short- and long-term survivors [Citation29–32]. Some studies have demonstrated that BRCA mutation status is associated with improved long-term survival independently of primary platinum sensitivity in stage III-IV ovarian cancer, suggesting that underlying tumor biology contributes to disease outcome [Citation33–35]. However, this data was not available in the present study as the analysis was retrospective. In the recurrent setting, similar results were reported with age [Citation7] being associated with long-term survival. Another study of recurrent platinum-sensitive patients found a that over half of patients survived more than 5 years (52.8%) [Citation36]. Multimodal treatment was also associated with long-term survival in different studies [Citation7,Citation37,Citation38].

The data presented herein should be taken cautiously into consideration given the retrospective nature of the study. For instance, this led to many patients with missing data for certain variables, such as CA125 for instance. Furthermore, the study is also small, which could explain why complete cytoreduction was not the most important prognostic factor in this group of patients; the confidence intervals are also wide and thus less clinically significant. Another aspect to consider is the definition of long-term survival. In the literature, long-term survivors are not clearly defined, especially in the ovarian cancer setting. Long-term survivors are often defined as patients who have experienced a prolonged survival after serious disease. A 5-year cut-off after initiation of the therapy is usually used although a 7-year [Citation30], and 10-year cut off has also been used. However, for some cancers with very poor prognosis, such as small cell lung cancer, the agreed standard definition is 3 years [Citation39]. As in treated women with EOC the majority of relapses occur before 5 years [Citation40], we chose this as the cut-off to define long-term survival. Moreover, it would have been informative to have information on BRCA mutation status as its role in long-term survival is not clearly defined [Citation41].

In conclusion, we found that disease aggressiveness such as assessed with PCI ≤8 and CA125 < 100 is associated with long-term survival in univariate analysis and that there was a trend towards significance of CC-score.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29.

- Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, et al. Carcinoma of the ovary. FIGO 26th annual report on the results of treatment in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95:S161–S192.

- Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, et al. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. JCO. 2002;20:1248–1259.

- Cannistra SA. Cancer of the ovary. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1550–1559.

- Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: the AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. JCO. 2014;32:1302–1308.

- Bakrin N, Bereder JM, Decullier E, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for advanced ovarian carcinoma: a French multicentre retrospective cohort study of 566 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:1435–1443.

- Hilal Z, Schultheis B, Hartmann F, et al. What characterizes long-term survivors of recurrent ovarian cancer? case report and review of the literature. AR. 2016;36:5365–5371.

- Bertelsen K. Tumor reduction surgery and long-term survival in advanced ovarian cancer: a DACOVA study. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;38:203–209.

- Chang SJ, Bristow RE, Ryu HS. Impact of complete cytoreduction leaving no gross residual disease associated with radical cytoreductive surgical procedures on survival in advanced ovarian cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:4059–4067.

- Tentes AA, Mirelis CG, Markakidis SK, et al. Long-term survival in advanced ovarian carcinoma following cytoreductive surgery with standard peritonectomy procedures. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:490–495.

- Kaern J, Aghmesheh M, Nesland JM, et al. Prognostic factors in ovarian carcinoma stage III patients. Can biomarkers improve the prediction of short- and long-term survivors? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:1014–1022.

- Bristow RE, Puri I, Chi DS. Cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:265–274.

- Ceelen WP, Van Nieuwenhove Y, Van Belle S, et al. Cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion in women with heavily pretreated recurrent ovarian cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2352–2359.

- Cotte E, Glehen O, Mohamed F, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemo-hyperthermia for chemo-resistant and recurrent advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: prospective study of 81 patients. World J Surg. 2007;31:1813–1820.

- Galaal K, Naik R, Bristow RE, et al. Cytoreductive surgery plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):CD007822.

- Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Mizuno M, et al. Long-term clinical outcome of patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: is it the same for each histological type?. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:394–399.

- Mulier S, Claes JP, Dierieck V, et al. Survival benefit of adding Hyperthermic IntraPEritoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) at the different time-points of treatment of ovarian cancer: review of evidence. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:3793–3803.

- Tian WJ, Jiang R, Cheng X, et al. Surgery in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: benefits on survival for patients with residual disease of 0.1-1 cm after secondary cytoreduction. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:244–250.

- Fagotti A, Costantini B, Vizzielli G, et al. HIPEC in recurrent ovarian cancer patients: morbidity-related treatment and long-term analysis of clinical outcome. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:221–225.

- van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:230–240.

- Spiliotis J, Halkia E, Lianos E, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: a prospective randomized phase III study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1570–1575.

- Didelot C, Lanneau D, Brunet M, et al. Anti-cancer therapeutic approaches based on intracellular and extracellular heat shock proteins. CMC. 2007;14:2839–2847.

- Hegyi G, Szigeti GP, Szasz A. Hyperthermia versus oncothermia: cellular effects in complementary cancer therapy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:1.

- Krag KJ, Canellos GP, Griffiths CT, et al. Predictive factors for long-term survival in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;34:88–93.

- Goff BA, Muntz HG, Greer BE, et al. Oncogene expression: long-term compared with short-term survival in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:88–93.

- Fleisch MC, Pantke P, Beckmann MW, et al. Predictors for long-term survival after interdisciplinary salvage surgery for advanced or recurrent gynecologic cancers. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:476–484.

- Winter WE, 3rd, Maxwell GL, Tian C, et al. Prognostic factors for stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. JCO. 2007;25:3621–3627.

- Grossi E, Noli S, Scarfone G, et al. Ten years survival of FIGO stage IIIC epithelial ovarian cancer cases due to lymph node metastases only. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2012;33:615–616.

- Barlin JN, Jelinic P, Olvera N, et al. Validated gene targets associated with curatively treated advanced serous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128:512–517.

- Berchuck A, Iversen ES, Lancaster JM, et al. Patterns of gene expression that characterize long-term survival in advanced stage serous ovarian cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3686–3696.

- Partheen K, Levan K, Osterberg L, et al. Expression analysis of stage III serous ovarian adenocarcinoma distinguishes a sub-group of survivors. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2846–2854.

- Stalberg K, Crona J, Razmara M, et al. An integrative genomic analysis of formalin fixed paraffin-embedded archived serous ovarian carcinoma comparing long-term and short-term survivors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:1027–1032.

- Chetrit A, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, Ben-David Y, et al. Effect of BRCA1/2 mutations on long-term survival of patients with invasive ovarian cancer: the national Israeli study of ovarian cancer. JCO. 2008;26:20–25.

- Gallagher DJ, Konner JA, Bell-McGuinn KM, et al. Survival in epithelial ovarian cancer: a multivariate analysis incorporating BRCA mutation status and platinum sensitivity. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1127–1132.

- Tan DS, Rothermundt C, Thomas K, et al. “BRCAness” syndrome in ovarian cancer: a case-control study describing the clinical features and outcome of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. JCO. 2008;26:5530–5536.

- Petrillo M, De Iaco P, Cianci S, et al. Long-term survival for platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer patients treated with secondary cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1660–1665.

- Iwase H, Takada T, Iitsuka C, et al. Clinical features of long-term survivors of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:143–149.

- Albuquerque K, Patel M, Liotta M, et al. Long-term benefit of tumor volume-directed involved field radiation therapy in the management of recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:655–660.

- Stephens RJ, Bailey AJ, Machin D. Long-term survival in small cell lung cancer: the case for a standard definition. Medical Research Council Lung Cancer Working Party. Lung Cancer. 1996;15:297–309.

- Rubin SC, Randall TC, Armstrong KA, et al. Ten-year follow-up of ovarian cancer patients after second-look laparotomy with negative findings. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:21–24.

- Hoppenot C, Eckert MA, Tienda SM, et al. Who are the long-term survivors of high grade serous ovarian cancer? Gynecol Oncol. 2017;148(1):204–212.

- Glehen O, Mithieux F, Osinsky D, et al. Surgery combined with peritonectomy procedures and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia in abdominal cancers with peritoneal carcinomatosis: a phase II study. JCO. 2003;21:799–806.