Abstract

Purpose

To explore the association of demographic characteristics, clinical symptoms and the fear of the disease progression factors with the physical and mental summary components of the health-related of life (HRQoL) of the papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Methods

123 PTMC survivors undergoing RFA were enrolled in this study from October 2019 to March 2020. Demographic, clinical symptoms and the fear of the disease progression data were collected. SF-36, THYCA-QoL and FoP-Q-SF were used to evaluate the HRQoL of patients, clinical symptoms and the fear of disease progression. A multivariate regression model was performed to evaluate the association between the independent variable and the HRQoL variable.

Results

The average self-reported HRQoL score was 81.17 ± 15.48 for the PCS and 73.40 ± 18.03 for the MCS. The multivariate linear regression model shows that the factors related to a poorer PCS were dependent for the female patients, the symptoms of neuromuscular and the throat/mouth, the fear of disease progression; the psychological disorder, symptoms of throat/mouth, inability to concentrate were related to worse scores for the MCS. The condition that was most strongly related to a poorer HRQoL (in both PCS and MCS) was the fear of their physical health.

Conclusions

The factors related to significantly worse HRQoL scores across PCS and MCS for PTMC survivors include the female gender, the symptoms of neuromuscular and the throat/mouth, the psychological disorder, inability to concentrate, and the fear of their own physical health. Identification, management, and prevention of these factors are critical to improving the HRQoL of patients.

Introduction

The incidence of thyroid cancer has been increasing worldwide over the past few decades, and the main variant is papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) [Citation1–3]. With the improvement of the ultrasound (US) screening and fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) [Citation4], the detection rate of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) whose maximum diameter is less than 1 cm has been increasing [Citation5,Citation6]. However, PTMC has an excellent prognosis and low mortality rate, with a 10-year survival rate of over 90% [Citation7].

At present, a surgical operation is still the main therapeutic measure for PTMC. However, it may bring some complications, which has a negative impact on patients’ quality of life [Citation8]. The 2015 American Thyroid Association (ATA) management guidelines recommend active surveillance (AS) for PTMC [Citation5]; however, since few PTMC may still have a risk of metastasis, most patients have great psychological stress and would not accept AS. Image-guided minimally invasive treatment including percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), percutaneous laser ablation (PLA), microwave ablation (MWA) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) [Citation9–11], which have been proposed as a first-line treatment for solid nonfunctioning thyroid nodule [Citation12], may solve the anxiety of patients and it may be a way to compensate for image deriving cancer overdiagnosis [Citation13]. Ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is an important therapeutic measure for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [Citation14,Citation15] and has yielded good results not only in the treatment of benign thyroid nodule [Citation16,Citation17] but also in the treatment of low-risk PTMC, which have been confirmed by several studies. In addition, our 5-year follow-up results showed that PTMC patients undergoing RFA have a good lesion reduction rate, few postoperative complications, quite a few recurrence/metastasis rates [Citation18].

Since PTMC patients undergoing RFA have good long-term efficacy, it is not sufficient to use survival as a measure for prognosis outcome. With the development of the modern bio-psycho-social medical model [Citation19], health-related quality of life (HRQoL) evaluation is an important part of the bio-psycho-social medical model, which pays more attention to individual subjective feelings and has been widely used as a measure of health care in clinical research and health economics evaluation [Citation20]. The 2015 ATA guidelines emphasized the importance of physicians taking the HRQoL into account when formulating treatment plans for patients [Citation5]. HRQoL is defined as the subjective perception that an individual’s important activities are affected by the current status of health, which reflects the individual’s satisfaction and happiness with life [Citation21]. Our previous studies have demonstrated that the HRQoL of PTMC patients undergoing RFA is better than that of patients undergoing surgery [Citation18,Citation22]. Nevertheless, HRQoL of PTMC survivors after RFA is affected by a variety of factors, such as disease-specific symptoms, fear of disease progression, social interaction. HRQoL assessment can help clinicians identify the needs of patients with PTMC after RFA and optimize treatment decisions. Therefore, we think it is important to identify the factors that affect HRQoL in order to take appropriate interventions. However, there have been no studies to identify the factors that influence HRQoL of PTMC survivors after RFA. In this study, we hypothesized that there are many adverse factors that affect the physical and mental components of survivors in different ways and degrees. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to identify those factors that influence HRQoL of PTMC survivors after RFA.

Patients and methods

Patients

This study was approved by the local Ethics Review Committee (registry number S2019-211-01). Informed consent was obtained from all patients before treatment procedures. From October 2019 to March 2020, 123 patients who had undergone RFA in our hospital were enrolled in our study.

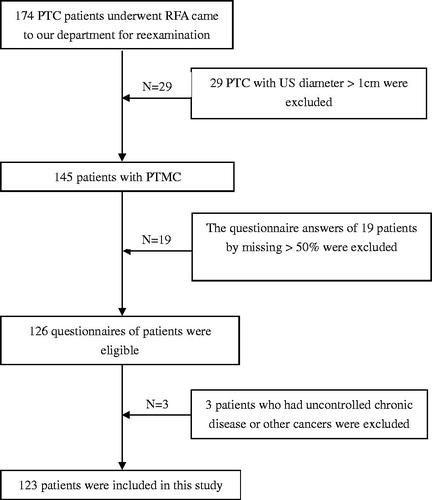

The inclusion criteria for the patients were: (1) solitary PTMC confirmed by CNB; (2) RFA therapy for PTMC was performed in our hospital; (3) more than 1 month’s follow-up. Patients with the following conditions will be excluded: (1) uncontrolled chronic diseases (such as heart failure, respiratory failure, liver failure or kidney failure) or other cancer; (2) unable to understand or complete the questionnaires; (3) preoperative clinical diagnosis of mental illness (such as depression, infantile autism, etc.) ().

Ablation procedure

In our study, all patients underwent a routine ultrasound and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) examination before ablation by using a 15L8W linear array transducer and a real-time US System (Siemens Acuson Sequoia 512, Siemens, Mountain View, CA) or an L12-5 linear array transducer and a real-time US System (Philips EPIQ7, Philips Healthcare, Bothell, WA) or an L12-4 linear array transducer and a real-time US System (Mindray M9, Mindray, Shenzhen, China). All RFA procedures were performed by the same sonographer (K.Y.L.) with clinical experience for 20 years in routine and interventional US.

Patients lay in the supine position with their necks extended. Skin sterilization was performed and 1% lidocaine was used for local anesthesia at the intended puncture site. The hydro-dissection technique was used with a mixture of 1% lidocaine injected into the anterior capsule space and normal saline injected into the posterior capsule space to protect vital structures (cervical artery, trachea, esophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerve) to prevent thermal injury when the distance between the lesion and the surrounding vital structures was less than 5 mm. The moving-shot technique was used to perform RFA [Citation23]. The RFA extends beyond the edge of the lesion to prevent local residue and recurrence. When all the target areas become transient hyperechoic zone, the ablation stops. During the procedure, more attention would be paid to protecting the surrounding vital structures to prevent major complications which are regarded as an unexpected event that leads to substantial morbidity and disability, which also increases the level of care [Citation24]. After RFA, all patients were observed for 1–2 h and were evaluated for and complication during or immediately after RFA.

Research methods

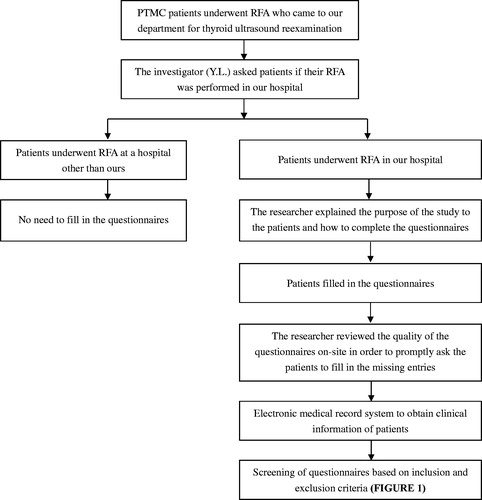

The aim of this study was explained to the patients orally and in writing. With the consent of the patients, all PTMC patients who came to our hospital for reexamination after RFA signed the informed consent form and filled in the questionnaires. Then the researcher checked whether the questionnaire was wrongly written or omitted and corrected in time. The questionnaires of the patients meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled in this study ().

Data collection and measures

To obtain data for analysis, we use a structured questionnaire to interview patients. The questionnaire was used to obtain detailed information on demographic characteristics, the disease-specific symptoms, fear of disease progression.

Demographic and clinical characteristics. The information of age, sex, height, weight, marital status, education level, employment status, source of medical expenses, the place to live, regarding levothyroxine (LT4) supplementation, comorbidity, and family history of thyroid cancer were collected.

Disease-specific symptoms. We use the Chinese version of the thyroid cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire (THYCA-QOL) to assess the symptoms of PTMC survivors after RFA [Citation25]. THYCA-QOL includes 24 items measure seven symptom domain (neuromuscular, voice, attention, sympathetic, throat/mouth, psychological, and sensory symptoms), as well as six single domains (scar, feeling a cold, tingling sensation, weight gain, headache, and reduced sexual interest) [Citation26,Citation27].

Fear of disease progression. Fear of disease progression is found in cancer survivors for a long time [Citation28].12-item Fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q-12) [Citation29] which is the short form of the 43-item Fear of Progression Questionnaire [Citation30] is used in our study. It includes two domains of fear of physical health and social family. The items of FoP-Q-12 are scored with Likert 1-5 scale ranging from 1(‘never’) to 5(‘often’). The scale is self-reported by patients with a total score of 12-60 points, a higher score indicates a greater level of anxiety about disease progression.

HRQoL assessment. The main outcome of this study was HRQoL assessed by the Chinese version of the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36) [Citation31]. The SF-36 is a multi-purpose short-form survey, a well-validated and standardized questionnaire measuring HRQoL that is used in many publications [Citation32,Citation33]. The SF-36 contains 36 questions and measures 8 domains: physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role emotional (RE), and mental health (MH). Two total scores of 36 items can be calculated: physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) representing the physical wellbeing and emotional wellbeing, respectively. PCS scores are the average score of PF, RP, BR and GH, similarly, MCS score is the average score of VT, SF, RE and MH. All scores of domains are transformed into scales of 0–100. The higher scores on the domains indicate the lower disability and better HRQoL.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are represented by mean and standard deviation, while category variables are represented by the number and percentage. One-way ANOVA or independent-sample t-test was used to analyze the influence of different levels of each demographic characteristic on PCS and MCS of quality of life, p < 0.05 was taken as the criterion of significant difference, and demographic variables with statistical significance were selected. Pearson correlation analysis was used to analyze the correlation between the symptoms scores of the thyroid cancer and the PCS and MCS scores in quality of life, and to screen out the symptoms’ variables with statistical significance. Multivariate linear regression analysis was conducted on the above screened demographic variables and symptom variables to evaluate the factors influencing the PCS and MCS score of HRQoL of patients. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 software (version 24.0; IBM, Inc., Chicago, IL), and all p-values were two-sided, p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics, the thyroid cancer-specific symptoms and the fear of disease progression the patients

The study sample was composed of 123 patients, with a mean age of 41.89 ± 9.66 years (range 21–64 years) and of whom 80.5% were female. Most patients had a BMI of less than 25 (64.23%), which is within the normal weight range. More than half of the patients had a bachelor’s degree or above (51.22%). Most patients were employed (69.92%). Almost all of them were married (90.24%) and did not have chronic comorbidity (90.24%). Most of the patients live in cities (84.55%) and have no family history of thyroid cancer (92.68%), they have to pay for medical treatment at their own expense (65.04%). Nearly half of the patients were followed for more than half a year (47.15%), and up to 90.24% did not need to supplement LT4, indicating that the thyroid function of patients after RFA was not affected ().

Table 1. The univariate analysis of quality of life after RFA in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma patients with different demographic characteristics.

On the THYCA-QoL scale, the most common symptoms (81.30%) patients complained of were psychological anxiety, characterized by a rapid heart rate and sudden physical fatigue. The second symptoms were the throat/mouth (78.86%). The patient has a dry mouth, difficulty swallowing, or a lump in the throat. Most patients also reported the symptoms of neuromuscular (70.73%), sympathetic (67.48%), sensory (69.11%), feeling cold (64.23%), tingling (75.61%), and headache (51.22%). The least common symptom patients complained of was scarring, indicating that RFA is minimally invasive, there is no obvious scarring associated with surgery ().

Table 2. The thyroid cancer-specific symptoms of PTMC survivors and fear of disease progression after RFA.

The fear of disease progression was found in most of PTMC survivors, including the fear of physical health and social family (93.50 vs 82.93%), especially of their own physical health.

Assessment of HRQoL and analysis of related factors

The patients’ perceptions of their HRQoL produced an average score of 81.17 ± 15.48 for the PCS and a somewhat lower one, 73.40 ± 18.03 for the MCS. shows the scores of PCS and MCS at different levels of demographic and clinical characteristics. Univariate analysis suggested that only sex was a factor affecting PCS, but not MCS. Males got higher scores than females in the PCS, with average values of 89.87 vs 79.56 (p < 0.05). Other variables, including age, BMI, education level, employment status, marital status, comorbidity, medical expenses, the place to live, family history of thyroid cancer, LT4 supplementation, follow-up duration, did not affect patients’ PCS and MCS scores.

The correlation analysis between symptoms scores and the scores of HRQoL showed that all the patients’ symptoms on the THYCA-QoL were associated with HRQoL of PTMC survivors after RFA except the symptoms of feeling cold, weight gain and less interest in sex (p < 0.05), the analysis also showed a negative correlation, that is, PCS and MCS scores declined as patients complained more about symptoms ().

Table 3. The correlation analysis between the scores of each domain on THYCA-QoL and the quality of life after RFA in PTMC patients.

To further examine the impact of the independent variables on the HRQoL, a multivariate linear regression analysis was conducted (). The multivariate linear regression model shows that sex, the symptoms of neuromuscular, throat/mouth and the fear of physical health were independent risk factors affecting the decreased PCS. The model fitting is good, the R2 = 0.472 which is >0.4, means that the results can reflect sex, the symptoms of neuromuscular, throat/mouth and the fear of physical health impact on the PCS scores in a real and reliable way. There is no multicollinearity between the four independent variables, variance inflation factor (VIF) is less than 5, all four independent variables can negatively affect patients’ HRQoL (beta <0), the regression equation between the independent variables and the PCS scores was: PCS = 115.513-8.025* sex-0.240* neuromuscular-0.242* throat/mouth-6.678* physical health; similarly, the regression equation between the independent variables and the MCS scores was: MCS = 99.961-0.262* psychology-0.341* throat/mouth-0.178* concentration-6.839* physical health. The condition that was most strongly related to a poorer HRQoL (in both PCS and MCS) was the fear of their own physical health.

Table 4. The multivariate stepwise regression analysis of the quality of life related factors in PTMC patients after RFA.

Discussion

HRQoL reflects an individual’s satisfaction and happiness to life. To some extent, it may affect the patient’s health or be affected by health-related factors. With the transformation of the traditional biomedical model to the bio-psycho-social modern medical model, the factors affecting the quality of life of patients include many aspects such as physical, emotional and social potential, rather than just the absence of disease [Citation34]. HRQoL has become an important indicator for assessing the health status of an individual. Recent ATA guidelines have also highlighted the importance of physicians considering the long-term quality of life when making treatment decisions for patients with thyroid cancer [Citation5].

Since the disease-specific mortality of PTMC is low, patients undergo long-term surveillance for tumor recurrence. This issue is likely responsible for the increased complaints of psychological issues and anxiety [Citation35], which are associated with the HRQoL after treatment. As a new therapeutic measure for PTMC, the efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided RFA have been widely proven [Citation18,Citation36], but there are few studies on the quality of life of PTMC patients after RFA. In order to further improve the quality of PTMC patients after treatment, this study found through multivariate linear regression analysis that female gender, the symptoms of neuromuscular and throat/mouth, inattention, psychological anxiety and the fear of their own physical health were the main risk factors affecting the quality of life patients.

The PCS scores of female patients were lower than of males, which is consistent with the research results of Aschebrook-Kilfoy et al. based on demographic surveys [Citation37]. This gender difference may, on the one hand, be due to the large number of female patients enrolled in our study and the increased exposure problems; on the other hand, it may be due to the poor physical quality and postoperative recovery ability of female patients compared with male patients, thus affecting the quality of life-related to physical health. For MCS, the scores of females were lower than that of males, although the difference was not statistically significant. It is consistent with the findings reported by Wang et al. [Citation38]. This result can be explained by the fact that men and women have different responses to cancer and different coping strategies [Citation39].

The fear of physical health affects both the physical and mental health of patients. In particular, psychological anxiety affects the MCS scores of patients. Previous studies have shown that patients with thyroid cancer after treatment always pay attention to recurrence and metastasis in long-term follow-up [Citation40]. According to Hedman et al., only 7% of patients actually experience recurrence of the disease, but up to 48% of patients suffer from the pressure of worrying about recurrence [Citation41], which seriously affects their quality of life. This may be because thyroid cancer survivors’ perceptions of the disease are often subjective and emotional and may not be consistent with the actual severity of the disease. Studies have shown that by using Naikan therapy, patients can be guided into a state of Naikan insight, reexamine themselves and put aside the negative and unrealistic thoughts in the past so that patients can be in a relatively calm state of mind, which is conducive to building patients’ confidence in treatment, and thus improving the treatment effect and quality of life [Citation42,Citation43].

Cancer pain is caused by cancer patients’ suffering from disease and pain, which makes them prone to bad moods and leads to a decline in self-efficacy, thus affecting the quality of life [Citation44]. In this study, patients mainly reported neuromuscular pain. On the one hand, due to the anxiety of the patients, irregular rest and sleep quality, poor sleep quality, and symptoms of neuromuscular discomfort and inattention have occurred. On the other hand, due to the follow-up of patients enrolled in our study are shorter, the discomfort of neuromuscular may be due to the patients’ head and neck hyperextension during the ablation procedure, resulting in postoperative symptoms such as muscle soreness, which may gradually recover with the extension of follow-up time.

There may be two reasons for the patients’ throat/mouth symptoms. On the one hand, the patients’ excessive attention to the disease state leads to tension and neck discomfort. On the other hand, when performing ultrasound-guided thermal ablation for the treatment of PTMC, in order to prevent residual cancer from causing disease recurrence, the operating physician will choose a range larger than the lesion for expanded ablation, which makes the volume of the ablation lesion larger than that of the primary lesion in the short term. Therefore, the sensation of a foreign body and swelling in the throat of the patient may be more obvious than the preoperative symptoms. Over time, symptoms may subside until they disappear. If doctors will explain these possible uncomfortable symptoms to patients before RFA, so that patients can make adequate psychological preparation, it may reduce the tension of patients after RFA, so as to improve the quality of life patients after treatment.

Limitations of this study: (1) The small sample size of this study cannot represent the HRQoL of all PTMC survivors undergoing RFA; (2) We are not sure whether the investigator’s interpretation of the questionnaire affected the patients’ filling in the questionnaire; (3) Due to the nature of its cross-sectional design, our study could detect factors associated with HRQoL, but could not establish a causal relationship. Therefore, prospective large sample cohort studies are needed.

In conclusion, many factors may affect the physical and mental components of HRQoL of PTMC survivors after the RFA. For the PCS, the related factors were dependent for the female gender, the symptoms of neuromuscular and throat/mouth and the fear of physical health. The main factors associated with lower MCS scores were the presence of psychological anxiety, the symptoms of throat/mouth, inattention and the fear of physical health. Some factors may be preventable or modifiable, therefore, identification of these factors and optimization of response measures are critical to improving the quality of life of a growing population of PTMC survivors. Clearly and consistently, the factor that was most strongly associated with a poorer overall HRQoL was the fear of physical health. As doctors, we should understand the adverse effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment on patients’ emotions and psychology, psychological and behavior intervention in a suitable way are questions of major importance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Jung K, Won Y, Oh C, et al. Prediction of cancer incidence and mortality in Korea, 2017. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49(2):306–312.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: A Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30.

- Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA: A Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132.

- Jegerlehner S, Bulliard J, Aujesky D, et al. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of thyroid cancer: a population-based temporal trend study. Plos One. 2017;12(6):e179387.

- Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1–133.

- Jeon M, Kim W, Kwon H, et al. Clinical outcomes after delayed thyroid surgery in patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177(1):25–31.

- Gartland R, Lubitz C. Impact of extent of surgery on tumor recurrence and survival for papillary thyroid cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(9):2520–2525.

- Dobrinja C, Pastoricchio M, Troian M, et al. Partial thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: is completion total thyroidectomy indicated? Int J Surg. 2017;41(5):S34–S39.

- Carrafiello G, Laganà D, Mangini M, et al. Microwave tumors ablation: principles, clinical applications and review of preliminary experiences. Int J Surg. 2008;6(1):S65–S69.

- Monchik JM, Donatini G, Iannuccilli J, et al. Radiofrequency ablation and percutaneous ethanol injection treatment for recurrent local and distant well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;244(2):296–304.

- Papini E, Guglielmi R, Gharib H, et al. Ultrasound-guided laser ablation of incidental papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a potential therapeutic approach in patients at surgical risk. Thyroid. 2011;21(8):917–920.

- Papini E, Pacella CM, Solbiati LA, et al. Minimally-invasive treatments for benign thyroid nodules: a Delphi-based consensus statement from the Italian minimally-invasive treatments of the thyroid (MITT) group. Int J Hyperther. 2019;36(1):375–381.

- Mauri G, Sconfienza LM. Image-guided thermal ablation might be a way to compensate for image deriving cancer overdiagnosis. Int J Hyperthermia. 2017;33(4):489–490.

- Lee D, Lee J, Kang T, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Radiofrequency Ablation for Early Hypovascular HCC: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Radiology. 2018;286(1):338–349.

- Seror O, N’Kontchou G, Nault J-C, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma within milan criteria: no-touch multibipolar radiofrequency ablation for treatment-long-term results. Radiology. 2016;280(2):611–621.

- Lee G, You J, Kim H, et al. Successful radiofrequency ablation strategies for benign thyroid nodules. Endocrine. 2019;64(2):316–321.

- Lim H, Lee J, Ha E, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of benign non-functioning thyroid nodules: 4-year follow-up results for 111 patients. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(4):1044–1049.

- Zhang M, Tufano RP, Russell J, et al. Ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation versus surgery for low risk papillary thyroid micro-carcinoma: results of over 5 years follow-up. Thyroid. 2020;30(3):408–418.

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2012;40(3):377–396.

- Makai P, Brouwer W, Koopmanschap M, et al. Quality of life instruments for economic evaluations in health and social care for older people: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2014;102(2):83–93.

- Group W, Study protocol for the World Health Organization Project to develop a quality of life assessment instrument (WHOQOL). Qual Life Res. 1993;2(2):153–159.

- Lan Y, Luo Y, Zhang M, et al. Quality of life in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation or surgery: a comparative study. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11(5):249.

- Jeong W, Baek J, Rhim H, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of benign thyroid nodules: safety and imaging follow-up in 236 patients. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(6):1244–1250.

- Mauri G, Pacella CM, Papini E, et al. Image-guided thyroid ablation: proposal for standardization of terminology and reporting criteria. Thyroid. 2019;29(5):611–618.

- Liu J, Gao J, Tang Y, et al. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Thyroid Cancer-specific Quality of Life (THYCA-QoL) questionnaire. Tumor. 2019;39(03):178–187.

- Husson O, Haak HR, Mols F, et al. Development of a disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire (THYCA-QoL) for thyroid cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):447–454.

- Husson O, Haak HR, Buffart LM, et al. Health-related quality of life and disease specific symptoms in long-term thyroid cancer survivors: a study from the population-based profiles registry. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):249–258.

- Koch L, Jansen L, Herrmann A, et al. Quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors - a 10-year longitudinal population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(6):1119–1128.

- Mehnert A, Berg P, Henrich G, et al. Fear of cancer progression and cancer-related intrusive cognitions in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2009;18(12):1273–1280.

- Thewes B, Butow P, Bell M, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in young women with a history of early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and association with health behaviours. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(11):2651–2659.

- Huang JK, Ma L, Song WH, et al. Quality of life and cosmetic result of single-port access endoscopic thyroidectomy via axillary approach in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9(7):4053–4059.

- Promberger RMD, Hermann MMD, Pallikunnel SJMD, et al. Quality of life after thyroid surgery in women with benign euthyroid goiter: influencing factors including Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Am J Surg. 2014;207(6):974–979.

- Yue W, Wang S, Lu F, et al. Quality of life and cost-effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation versus open surgery for benign thyroid nodules: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):37838.

- Wang R, Wu C, Zhao Y, et al. Health related quality of life measured by SF-36: a population-based study in Shanghai, China. Bmc Public Health. 2008;8(1):292.

- Lubitz CC, De Gregorio L, Fingeret AL, et al. Measurement and variation in estimation of quality of life effects of patients undergoing treatment for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2017;27(2):197–206.

- Zhang M, Luo Y, Zhang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation for treating low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a prospective study. Thyroid. 2016;26(11):1581–1587.

- Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, James B, Nagar S, et al. Risk factors for decreased quality of life in thyroid cancer survivors: initial findings from the North American Thyroid Cancer Survivorship Study. Thyroid. 2015;25(12):1313–1321.

- Wang T, Jiang M, Ren Y, et al. Health-related quality of life of community thyroid cancer survivors in Hangzhou, China. Thyroid. 2018;28(8):1013–1023.

- Crevenna R, Zettinig G, Keilani M, et al. Quality of life in patients with non-metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer under thyroxine supplementation therapy. Supp Care Cancer: Official J Multinational Assoc Supp Care Cancer. 2003;11(9):597–603.

- Bresner L, Banach R, Rodin G, et al. Cancer-related worry in Canadian thyroid cancer survivors. The J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2015;100(3):977–985.

- Hedman C, Djarv T, Strang P, et al. Determinants of long-term quality of life in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma - a population-based cohort study in Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(3):365–369.

- Sengoku M, Murata H, Kawahara T, et al. Does daily Naikan therapy maintain the efficacy of intensive Naikan therapy against depression? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64(1):44–51.

- Tashiro S, Hosoda S, Kawahara R. [Naikan therapy for prolonged depression: psychological changes and long-term efficacy of intensive Naikan therapy]. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2004;106(4):431–457. In Japanese.

- Crombez P, Bron D, Michiels S. Multicultural approaches of cancer pain. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31(4):268–274.