Abstract

Background and Aims

Many previous studies comparing liver resection versus thermal ablation for colorectal cancer liver metastases (CRCLM) are subject to severe selection bias. This study aimed to compare the long-term clinical efficacy of ultrasonography-guided percutaneous microwave ablation (PMWA) with resection for CRCLM using propensity score analysis to reduce confounding by indication.

Methods

This retrospective study included 184 patients with CRCLM from January 2012 to June 2017. Treatment effect was estimated after propensity score matching, Descriptive, regression and survival statistics were applied.

Results

A lower American Society of Anesthesiologists classification score and higher performance status were found positively associated with resection (p < 0.05). After propensity score matching, the 1-, 2-, and 3-year local tumor progression free survival rates were found to be 60.3%, 19.1%, and 17.6% in the PMWA group, and 72.1%, 35.3%, 26.5% in the resection group, respectively (p = 0.049). The 1-, 3-, 5-, and 7-year overall survival rates in two groups were similar (p = 0.943). In the PMWA group and resection group, the median hospital stay was 1 (0–12) days and 7 (1–27) days (p = 0.005), respectively; major complications occurred in two patients (2%) and 11 patients (12.9%) (p = 0.009), respectively.

Conclusions

After adjusting for factors known to affect treatment choice, no significant difference in overall survival rates was shown after ultrasound-guided PMWA versus resection for CRCLM. The LTPFS rate of the resection group were better than those of the ultrasound-guided PMWA group. However, the ultrasound-guided PMWA group had fewer complications and shorter hospital stay.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a malignant tumor with a high global incidence [Citation1]. Colorectal cancer accounts for approximately 10% of all annually diagnosed cancers and cancer-related deaths worldwide [Citation2]. It is the second most common cancer diagnosed in women and third most in men. With the changing physical activity levels, smoking, and diet, the incidence of colorectal cancer has been increasing annually. With continuing progress in developing countries, the incidence of colorectal cancer worldwide is predicted to increase to 2·5 million new cases in 2035 [Citation2]. The main cause of death in patients with colorectal cancer is distant metastasis, liver being the main target organ [Citation3], with approximately 50% of patients with colorectal cancer having colorectal cancer liver metastases (CRCLM) [Citation4].

The median survival time (MST) of patients with unresectable CRCLM is only 6.9 months, and the 5-year survival rate is almost 0 [Citation5]. In patients with CRCLM that could be radically removed, the MST is increased to 35 months, and the 5-year survival rate could reach 30–50% [Citation6,Citation7]. Radical surgery is the best curative treatment approach for CRCLM [Citation6,Citation7]. Although it is the first choice of treatment for CRCLM, surgery is feasible in only 10–20% of patients with CRCLM. The vast majority of these patients cannot undergo radical surgical resection due to old age, deeply located lesions, insufficient hepatic reserves, comorbidities, a history of extensive abdominal surgery, or the presence of extrahepatic disease.

In the past 10 years, another treatment that has been increasingly used, researched, and reviewed in the United States and other countries is microwave ablation (MWA), which utilizes electromagnetic methods to efficiently destroy tumor cells in CRCLM [Citation8]. The efficacy and safety of MWA as well as radiofrequency ablation have also been confirmed in the treatment of CRCLM and primary liver cancer [Citation5,Citation9,Citation10]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports comparing the long-term survival of patients undergoing ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation (PMWA) and surgical resection for CRCLM. Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the long-term efficacy of ultrasound-guided PMWA and compare it with surgical resection for the treatment of CRCLM.

Methods

Patient selection and data extraction

We conducted a retrospective cohort study on a consecutive series of patients with hepatic metastases at a single tertiary hospital. The study was approved by our institutional review board.

The diagnosis of CRCLM was confirmed by pathology after resection and biopsy before PMWA. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who underwent radical resection of colorectal tumor, which was pathologically confirmed as colorectal cancer with a negative surgical margin; (2) all patients who were confirmed to have metastasis to the liver by imaging, with no metastasis found in the abdominal cavity or distant organs during the ultrasound-guided PMWA/resection of CRCLM; (3) those with no contraindication for surgery or ultrasound-guided PMWA; (4) CRCLM lesion diameter ≤5 cm and CRCLM lesion number ≤3; (5) CRCLM treated for the first time, metastases treated with ultrasound-guided PMWA or liver resection alone, and no second CRCLM resection and/or ultrasound-guided PMWA (in order to exclude the impact of multiple resection or PMWA on the survival time of CRCLM patients).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who lacked follow-up; (2) patients who underwent ultrasound-guided PMWA and liver resection at the same time; (3) one or more ultrasound-guided PMWA or liver resections were conducted on the patient after the initial ultrasound-guided PMWA or liver resection; (4) the lesion size was >5 cm; (5) the patient had abdominal metastasis and/or distant metastasis.

All patients enrolled in the study underwent imaging studies, including ultrasonography (US), contrast-enhanced ultrasound, contrast-enhanced computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), physical examination, and laboratory tests prior to treatment. Data on sex, age, number and size of CRCLM, and baseline data, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, liver metastasis interval, and Dukes’ grade of primary colorectal cancer, World Health Organization performance status, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, length of hospital stay, rat sarcoma viral oncogene (RAS), Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) score [Citation11], and treatment with chemotherapy (yes/no) were also obtained. Major complications were defined as Clavien–Dindo grade ≥ IIIa.

Treatment

The decisions on treatment approaches for CRCLM were made at the multidisciplinary team conferences, following the international guidelines [Citation6]. Resection was offered as a first-line treatment to all patients with resectable tumor. Patients with metachronous hepatic colorectal metastases, who met defined inclusion criteria and had tumors that were determined unresectable by the consensus of a multidisciplinary team, were included in PMWA group.

Microwave ablation

PMWA was performed using a color Doppler ultrasound diagnostic apparatus (Aloka ProSound-α 7, Elli Aloka, Japan) with 3.5 C convex array probe (2 ∼ 6 MHz) and equipped with puncture guide device. The emission frequency of the microwave instrument was 2,450 MHz, and the output power was 60 W (Nanjing Qinghai Institute of Microwave Electronics, China, MTC-3C). The microwave ablation needle is a disposable microwave ablation needle with a cold circulation system, model ECO-100CI10, specification 2.0 × 200 mm, and the cold circulation liquid is frozen physiological saline. 30 min before PMWA, intramuscular injection of Meperidine 50 mg + atropine 0.5 mg. The needle entry route was strictly determined based on the imaging results (traditional ultrasound, contrast-enhanced ultrasound or fusion imaging), and 2% lidocaine was used for local anesthesia. Under US guidance, the microwave antennas were inserted into a predetermined position. The microwave instrument and the water circulation cooling device were then connected. The output power is 60 W and the ablation time is 6 min for treatment. Among them, the diameter of the lesion is ≤3 cm, and a single electrode is used for ablation; the diameter of the lesion is >3 cm, and two microwave electrodes are used for simultaneous ablation according to the specific conditions of the patient. The ideal ablation range requires the thermal field to cover all around the target tumor at least 5 mm and ideally 10 mm. No artificial ascites was used for ablation of all lesions.

Surgical resection

Patients in the resection group underwent conventional surgical treatment. The specific procedures were as follows: the patients underwent laparotomy/laparoscopic surgery after induction of general anesthesia, and the liver resection plan was formulated according to the tumor conditions. All tumors that were visible to the naked eye were removed during the process.

Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy

Some patients received systemic chemotherapy. The patients received systemic chemotherapy as determined by our medical oncologist (including decisions of timing, dose, and frequency of cycles). The Douillard chemotherapy regimen (irinotecan, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil) was most frequently used. Patients received four to six cycles of this regimen as adjuvant treatment. If there was any disease progression, irinotecan was replaced by the FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin) regimen. Except for a two-week cessation of drug administration around PMWA and resection, there were no specific modifications in chemotherapy administration. The number of patients receiving systemic chemotherapy in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group and resection group was recorded.

Postoperative follow-up

The initial postablation cross-sectional imaging study to assess the efficacy of PMWA and resection was performed with contrast-enhanced MRI within 4–6 weeks after the procedures. Minimal PMWA and resection margin evaluation on the three orthogonal planes was performed as previously described using the first cross-sectional contrast-enhanced MRI study following PMWA and resection [Citation12]. MR-enhanced scanning was performed by intravenous injection of 30 ml of the MR contrast agent, meglumine gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany), at a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg at a rate of 2 ml/s. The minimal PMWA and resection margin achieved in all three-dimensional axes was utilized to categorize as having <5 mm, 5–10 mm or >10 mm of minimal margin [Citation13]. All patients were followed-up with a contrast-enhanced MRI every 3 months in the first year after surgery, and every 6 months, thereafter, to establish a complete follow-up profile. The clinical pathological data of the patients were coded and entered into a computer system. Local tumor progression (LTP) was defined as the occurrence of new peripheral or nodular enhancement within 1 cm of the treated tumor, or an enlargement of the initial ablation zone at any follow-up examination performed more than 1 month after PMWA and resection. LTP-free survival (LTPFS) was defined as the time period between initial PMWA and resection and the first imaging evidence of LTP [Citation14]. The survival time was defined as the time from PMWA and resection to death and was calculated in months. The survival rate was based on death as the event endpoint.

Statistical methods

Propensity-score matching was applied in an attempt to create two comparable groups and thus reduce selection bias and confounding by indication. Each patient was given a propensity score defined as the patient's probability of being treated with either PMWA or resection (dependent variables), calculated based on the variables listed in (independent variables). The variables were selected based on their assumed ability to predict the choice of treatment approach. A one-to-one match between the resection and MWA groups was performed by the nearest neighbor-matching method. The caliper was set to 0.02 to minimize the loss of cases (PMWA treated) and increase the number of potential controls (resected) but preserve nonsignificant differences in all variables after matching. Standardized mean differences for continuous and categorical variables were calculated before and after propensity score matching. To avoid introduction of selection bias due to the propensity score matching itself, differences between matched patients and patients that remained nonmatched due to a lack of suitable controls were analyzed and compared within each treatment group. Continuous data were presented as medians and categorical variables as frequencies. Differences between groups were analyzed using Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Pearson's chi-squared test, or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. p < 0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference. Moreover, the Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate the overall survival rate of the two groups, and the Cox risk ratio model was employed for the multivariate analysis of prognosis. All statistical analyses were conducted using a commercial statistical software (SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23, SPSS Inc.).

Table 1. Baseline patient and tumor characteristics in MWA and resection groups before (a) and after (b) propensity score matching.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

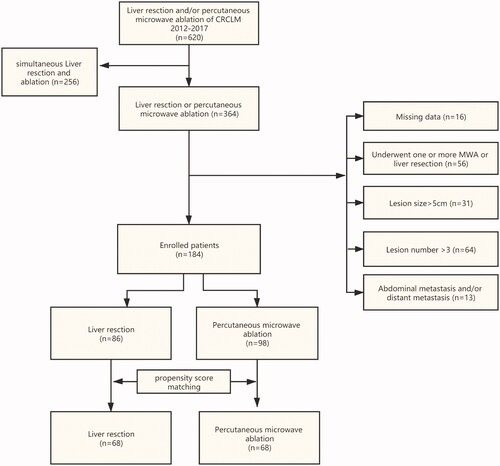

A total of 620 patients with CRCLM were treated from January 2012 to June 2017, of which 256 patients were excluded because they underwent ultrasound-guided PMWA and liver resection at the same time, 56 patients were excluded because they underwent one or more ultrasound-guided PMWA or liver resection after the initial ultrasound-guided PMWA or liver resection, 31 patients were excluded because their lesion size was >5 cm, 64 patients were excluded because their lesion number was >3, and 13 patients were excluded because of abdominal metastasis and/or distant metastasis. Follow-up was performed till November 1, 2020, and 16 patients were further excluded because of loss to follow-up (). A total of 184 patients (112 men and 72 women, aged 39–76 years [average age, 57 ± 9 years]) were included in the final analysis. The patients were divided into two groups: (1) ultrasound-guided PMWA group (n = 98, 56 men and 42 women, age 59 ± 11 years); these patients had not undergone resection of CRCLM, and second or multiple resections and/or ultrasound-guided PMWA had not been performed and (2) resection group (n = 86, 56 men and 30 women, age 56 ± 11 years); these patients had no history of ultrasound-guided PMWA of CRCLM before surgical resection, and a second or multiple liver resections and/or ultrasound-guided PMWA after surgery was not performed).

Patients in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group had a smaller lesion size, higher ASA score and a more severe comorbidity index than patients in resection group. No statistically significant differences in sex, age, number of metastases in the liver, CEA, liver metastasis interval, standard chemotherapy, RAS status, MSKCC score, and Dukes’ grade of primary colorectal cancer were found between the ultrasound-guided PMWA and resection groups (p > 0.05) (). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors affecting treatment choice, lower ASA class and higher performance status increased the possibility of choosing resection (p < 0.05).

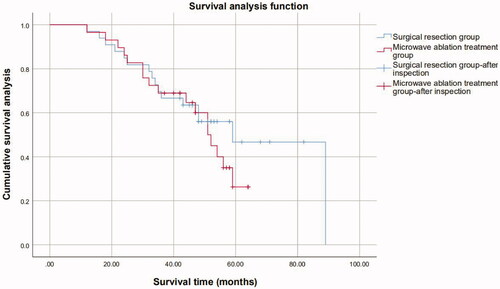

Factors associated LTPFS

After propensity score matching, during the follow-up process, a total of 109 patients presented with LTP (109/136, 80.1%), and 27 patients thus far have not shown LTP (27/136, 19.9%). The overall median LTPFS of all patients was 15 months (95%, CI, 9.7–17.6). The median LTPFS of patients in the ultrasound-guided PMWA and resection groups were 15 months and 17 months, respectively. The 1-, 2-, and 3-year LTPFS rates were 60.3%, 19.1%, 17.6%, and 72.1%, 35.3%, 26.5% in the ultrasound-guided PMWA and resection groups, respectively. The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.049). Intrahepatic distant recurrences occurred in two patients (2%) and one patient (1%) in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group and resection group, respectively (p = 0.559). Extrahepatic metastasis occurred in three patients (3%) and one patient (1%) in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group and resection group, respectively (p = 0.310).

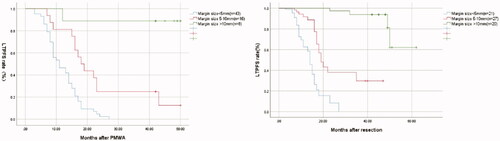

In the PMWA group, there were 43 cases with a margin size of <5 mm, 16 cases with a margin size of 5-10 mm, and eight cases with a margin size >10 mm. In the resection group, there were 21 cases with margin size <5 mm, 27 cases with margin size 5–10 mm, and 20 cases with margin size >10 mm (p < 0.001). Two-year LTPFS rates for tumors with <5, 5–10, >10 mm margin for PMWA and resection group were 2.3%, 25.0%, 88.9%, and 8.4%, 38.0%, 93.9% respectively (p < 0.001; ). Increased margin size was statistically significantly associated with LTPFS (p < 0.001). Univariate- and multivariate analysis indicated that the additional factors associated with increased local tumor control were tumor size (HR: 1.9, 95% CI:1.2–3.8, p = 0.030) and margin size (HR: 10.1, 95% CI:4.3–25.7, p < 0.001).

Overall survival

The follow-up was conducted until November 1, 2020, and the median follow-up time was 50 months. The loss to follow-up rate was 6.8% (16/234). After propensity score matching, the median follow-up period in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group was 47 (12–99) months and that in the resection group was 47.5 (12–103) months. At the final follow-up, 74 patients survived (74/136, 54.4%) and 62 patients died (62/136, 45.6%).

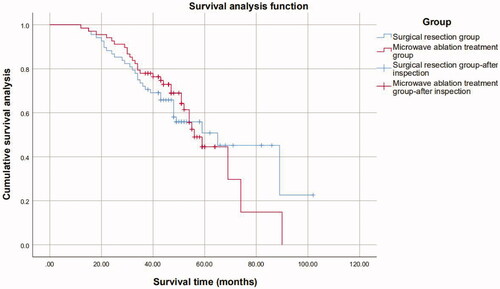

The 1-, 3-, 5-, and 7-year overall survival rates were, 98.5%, 77.9%, 44.5%, and 14.8% and 98.5%, 72.1%, 50.8%, and 45.2% in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group and resection group, respectively. No statistically significant difference in the overall survival rates was observed between the groups (p = 0.943) ().

Univariate analysis showed that the number and size of liver metastases, age ≥65 years, ASA class, margin size, RAS status, and high Charlson’s comorbidity index were risk factors affecting the survival time of patients (). Multivariate analysis showed that the size of CRCLM, margin size, RAS status, and age of patients were independent risk factors affecting patient prognosis ().

Table 2. Univariate and multivariable analysis of the prognosis of liver metastases from colorectal cancer.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of the Cox model affecting the survival and prognosis of colorectal cancer liver metastases.

In the ultrasound-guided PMWA group and resection group, the median hospital stay was 1 (0–12) days and 7 (1–27) days (p = 0.005), respectively; major complications occurred in two patients (2%) and 11 patients in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group and resection group, respectively (12.9%) (p = 0.009) ().

Table 4. Complications of PMWA and resection groups.

Size of metastatic lesions

Metastatic lesions were divided into <3 cm and ≥3 cm group. For the liver metastatic lesions with a diameter <3 cm, the 1-, 3-, 5-year overall survival rates were, respectively, 97.4%, 84.0% and 64.0% in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group and 97.1%, 77.1% and 55.6% in the resection group (p = 0.393). For the 63 patients who presented with lesions >3 cm (30 in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group, 33 in the resection group), lesions treated by ultrasound-guided PMWA recurred 1.3 times more often compared to those treated by surgery (100% versus 75.8%, p = 0.04). Time to recurrence was significantly shorter after treatment with ultrasound-guided PMWA (9 versus 14 months, p = 0.037). For the liver metastatic lesions with a diameter ≥3 cm, the 1-, 3-, 5-year overall survival rates were, respectively, 96.6%, 69.0%, 26.3% in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group and 97.0%, 66.7%, 42.7% in the resection group (p = 0.439) (). For patients with liver metastatic lesions with a diameter ≥3 cm, the 5-year and 6-year survival rate was higher in the resection group than in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group (p < 0.001) ().

Discussion

In our study, we compared the long-term efficacy of ultrasound-guided PMWA and surgical resection for CRCLM after adjusting for factors known to affect treatment choice. We found no statistically significant differences in the overall survival rates between the two groups. For CRCLM with a lesion diameter of ≥3 cm, the overall survival rates of the resection group were better than those of PMWA. And the LTPFS rate in the PMWA group was lower than that in the resection group. But PMWA has fewer complications and shorter hospital day. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that used long-term data and propensity score matching to compare ultrasound-guided PMWA with surgical resection for CRCLM.

Our results (77.9% in the resection group and 72.1% in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group) are similar to Pascale et al [Citation15]. However, our study differs from the previous study in two ways. First, our study enrolled patients who underwent only one treatment, whereas the previous study had multiple treatments that influenced the patients’ survival time. More importantly, in our study, 86.8% patients (118/136) underwent preoperative chemotherapy; in previous study, only 51.7% (140/271) underwent preoperative chemotherapy. While providing localized treatment, strengthening systemic chemotherapy or systemic treatment is also essential to further reduce the incidence of metastasis and recurrence.

Studies have reported that the size of metastatic lesions has little effect on the survival of patients with CRCLM [Citation16]. Our study found that for CRCLM lesions ≥3 cm in diameter, the long-term survival rate was higher in the resection group than in the ultrasound-guided PMWA group. This was because ensuring the ablation effect on lesions with a diameter of ≥3 cm is difficult [Citation17]. In addition, for lesions with a diameter of ≥3 cm, multiple overlapping ablation strategies are often required, and some residual tumor cells may persist. In our study, the proportion of patients with a margin size of <5 mm in the PMWA group was greater than that in the resection group (43/68 vs. 21/43), especially for tumors >3 cm (29/30 vs. 17/33). The LTPFS of the PMWA group was shorter, which is in line with previous research [Citation12,Citation18]. Thus, the therapeutic effect of ultrasound-guided PMWA is lower than that of surgical treatment. Furthermore, a large tumor volume is associated with greater tumor burden, higher probability of distant metastasis, and worse prognosis. Thus, hepatic artery embolization chemotherapy combined with ultrasound-guided PMWA therapy or multiple needle ablation may be considered. Bland embolization and radiofrequency thermal ablation within the same session have proven to be an effective and safe treatment [Citation19]. Expanding the range of ablation could further improve patient prognosis [Citation20].

Our research also found that the RAS status and the age of the patients were independent risk factors affecting patient prognosis. The observed age disparity in survival improvement among colon cancer patients was primarily explained by a slower improvement in adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines in elderly than younger patients. Many older adults were not receiving recommended therapies despite minimal comorbidities [Citation21]. Mutations in the rat sarcoma virus oncogene (RAS), a well-known downstream component of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling network, are related to resistance to EGFR antibody therapy, and colorectal cancer cells are more infiltrating or have more migrating tumor characteristics [Citation22].

This study, using propensity score matching allows adjustments for background bias and indication confusion, thus minimizing the main components and reducing the generality of previously published results. This study has some limitations. This was a retrospective study, and the number of patients was small. The type of chemotherapy administered to patients is also an important factor affecting patient prognosis. We still need to study the impact of the type of chemotherapy administered in more detail.

Conclusions

After adjusting for factors known to affect treatment choice, the overall survival rates of ultrasound-guided PMWA were similar to those of the resection group. For CRCLM with a lesion diameter of ≥3 cm, the overall survival rates of the resection group were better than those of the PMWA group. More importantly, less than 3 cm lesions the survival in the two groups is comparable. Additionally, the LTPFS rate in the PMWA group was lower than that in the resection group. However, the PMWA group had fewer complications and shorter hospital stay.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank HongChang Luo for providing English-language editing services.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34.

- Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels J, et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019;394(10207):1467–1480.

- Provenzale D, Ness RM, Llor X, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: colorectal cancer screening, version 2.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(10):1312–1320.

- Arru M, Aldrighetti L, Castoldi R, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors influencing long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2008;32(1):93–103.

- Wang J, Liang P, Yu J, et al. Clinical outcome of ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation on colorectal liver metastases. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(1):323–326.

- Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1386–1422.

- Khan K, Wale A, Brown G, et al. Colorectal cancer with liver metastases: neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection first or palliation alone? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(35):12391–12406.

- Poulou LS, Botsa E, Thanou I, et al. Percutaneous microwave ablation vs radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(8):1054–1063.

- Soliman AF, Abouelkhair MM, Hasab AM, et al. Efficacy and safety of microwave ablation (MWA) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in difficult anatomical sites in egyptian patients with liver cirrhosis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(1):295–301.

- Lee H, Heo JS, Cho YB, et al. Hepatectomy vs radiofrequency ablation for colorectal liver metastasis: a propensity score analysis. WJG. 2015;21(11):3300–3307.

- Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230(3):309–318, 318-21.

- Wang X, Sofocleous CT, Erinjeri JP, et al. Margin size is an independent predictor of local tumor progression after ablation of Colon cancer liver metastases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(1):166–175.

- Gillams A, Goldberg N, Ahmed M, et al. Thermal ablation of colorectal liver metastases: a position paper by an international panel of ablation experts, the interventional oncology sans frontières meeting 2013. Eur Radiol. 2015;25(12):3438–3454.

- Ahmed M, Solbiati L, Brace CL, Standard of Practice Committee of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe, et al. Image-guided tumor ablation: standardization of terminology and reporting criteria-a 10-year update. Radiology. 2014;273(1):241–260.

- Tinguely P, Dal G, Bottai M, et al. Microwave ablation versus resection for colorectal cancer liver metastases – A propensity score analysis from a population-based nationwide registry. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46(3):476–485.

- Choti MA, Sitzmann JV, Tiburi MF, et al. Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2002;235(6):759–766.

- Meijerink MR, Puijk RS, van Tilborg A, et al. Radiofrequency and microwave ablation compared to systemic chemotherapy and to partial hepatectomy in the treatment of colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41(8):1189–1204.

- Han K, Kim JH, Yang SG, et al. A Single-Center retrospective analysis of periprocedural variables affecting local tumor progression after radiofrequency ablation of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Radiology. 2021;298(1):212–218.

- Bonomo G, Della Vigna P, Monfardini L, et al. Combined therapies for the treatment of technically unresectable liver malignancies: bland embolization and radiofrequency thermal ablation within the same session. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35(6):1372–1379.

- Harari CM, Magagna M, Bedoya M, et al. Microwave ablation: comparison of simultaneous and sequential activation of multiple antennas in liver model systems. Radiology. 2016;278(1):95–103.

- Chen F, Wang F, Bailey CE, et al. Evaluation of determinants for age disparities in the survival improvement of colon cancer: results from a cohort of more than 486,000 patients in the United States. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10(10):3395–3405.

- Calandri M, Yamashita S, Gazzera C, et al. Ablation of colorectal liver metastasis: Interaction of ablation margins and RAS mutation profiling on local tumour progression-free survival. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(7):2727–2734.