Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to analyze the survival outcomes and prognostic factors of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for liver metastases from gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs).

Methods

Between March 2011 and November 2022, 34 patients (16 males; age range, 25–72 [median age, 52.5] years) who underwent RFA for liver metastasis from GISTs were included. The mean maximum diameter of metastatic lesions was 2.4 ± 1.0 (range, 1.1–5.2) cm. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate analyses were performed using a Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

For 79 lesions among 34 patients, all targeted lesions were completely ablated. The mean hepatic progression-free survival (HPFS) period was 28.4 ± 3.8 (range, 1.0–45.7) months. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year HPFS rates were 67.2%, 60.5%, and 20.2%, respectively. Based on the univariate analysis, the number of metastatic tumors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors(TKI) therapy before RFA were prognostic factors for HPFS. Multivariate analysis showed that pre-RFA TKI therapy was associated with a better HPFS(p = 0.030). The mean overall survival (OS) period was 100.5 ± 14.1 (range, 3.8–159.5) months and the 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 96.9%, 77.1%, and 58.7%, respectively. Both univariate and multivariate analysis indicated that extrahepatic metastasis before RFA (p = 0.044) was a significant prognostic factor for OS.

Conclusions

Liver metastases from GIST exhibit relatively mild biological behavior. RFA is safe and effective, particularly in patients without pre-RFA extrahepatic metastases. Patients received targeted therapy before RFA can obtain an extended HPFS.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GISTs) are the most frequent soft tissue sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract and are mostly derived from precursors of interstitial cells of Cajal [Citation1]. In China, the annual incidence rate of GISTs is approximately be 0.42 per 100,000 [Citation2]. GIST metastases occur most often in the liver and peritoneum. Currently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as imatinib as the first-line treatment for metastatic GISTs [Citation3]. However, most of patients cannot reach a complete response, and half of the patients develop resistance to imatinib after 2–3 years of therapy through new gene mutations [Citation4]. Therefore liver resection, ablation procedures, and other liver therapies are recommended for hepatic metastatic disease to prolong survival [Citation3,Citation5].

Metastatic GISTs of the liver are generally not sensitive to chemoembolization [Citation6], and most patients are not candidates for partial hepatectomy because of anatomic limitations, multiple liver metastases, and expected poor functional liver reserve. Therefore, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has become an alternative strategy for primary and metastatic liver tumor [Citation7]. However, few reports have focused on the safety and long-term efficacy of RFA for treating liver metastases from GIST. Accordingly, in this single-center study, we aimed to focused on these rare cases and retrospectively investigated the survival outcomes and prognostic factors of RFA for liver metastases from GISTs during the era of TKI therapy in China. Among them, majority cases (88.2%) underwent TKI treatment.

Materials and methods

Patients

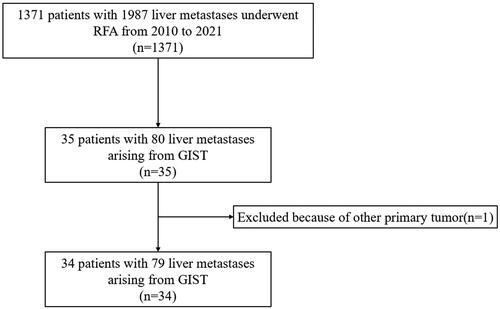

We retrospectively analyzed 34 patients with liver metastases from GISTs who underwent percutaneous RFA at our center between March 2011 and November 2022. All patients met the following criteria for RFA: (1) liver metastasis visible on ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, (2) liver function classification of Child-Pugh A or B, (3) an international normalized ratio <1.6 and platelet count >50 000/μL, (4) absence of significant tumor invasion of portal vein or bile ducts on imaging, (5) without other primary tumor, and (6) willingness to receive local therapy for liver metastases. The patient selection flow chart was shown in .

Figure 1. Patient selection flow chart. RFA: radiofrequency ablation, GIST: gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of our institute (2018KT35), and the requirement to obtain informed written consent was waived.

Radiofrequency ablation

Two radiologists with >10-year experience in ultrasound-guided interventional procedures performed all RFAs. A thorough explanation of the ablation process was provided [Citation8,Citation9]. Before RFA, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was conducted within 1 month as a reference for ablation. When percutaneous RFA was performed, the patients were under conscious sedation and were administered 2.5–5.0 mg of midazolam (Roche; Basel, Switzerland) and 50–100 lg fentanyl (Fentaini; Renfu, Yichang, China). Ultrasonography was used as the guidance modality in all patients. If the tumor was poorly visualized on ultrasonography, contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) was used to identify the ablation zone. The ablation zone aimed to cover a distance of at least 0.5 cm (ideally 1 cm) beyond the target tumor except for tumors adjacent to major structures such as big vessels, the gallbladder or bowels. In those cases (safety margin less than 0.5 cm), individualized protocols, including artificial pleural or ascites, design of the electrode’s placements were established to reduce thermal injury as previously described [Citation10].

The patients’ vital signs were monitored during the entire operation period, including blood pressure, and oxygen saturation etc. During the entire RFA process, ultrasonography was used to real time monitor the position of electrode, the echogenicity range of ablation and the relationship of electrode tip between nearby structures. After the procedure, treatment effectiveness was evaluated using ultrasonography and CEUS. Supplementary ablation was immediately performed if any residual tumor was detected. The patients were admitted on the day of RFA and stayed in the hospital overnight after RFA in case any operation-related complications occurred.

Efficacy evaluation and follow-up

Complete ablation (technical efficacy) was defined as the ablation area displaying no enhancement on enhanced CT or MRI 1 month after RFA. Technique efficacy refers to the prospectively defined time point at which complete ablation of the macroscopic tumor is achieved, as evidenced by follow-up imaging [Citation11]. In our study, enhanced CT or MRI performed 1 month after RFA was used to evaluate the efficacy of this technique. During follow-up, patients underwent repeat ultrasonography and CECT/MRI every 3-4 months. Local tumor progression (LTP) was defined as the appearance of new lesions within 1 cm or enlargement along the ablation zone for at least 1 month after RFA treatment. New tumor development referred as new metastasis, appeared far from the ablation zone.

Hepatic progression-free survival (HPFS) was defined as the interval, between the initial RFA treatment and any follow-up imaging showing the development of new hepatic tumors or mortality in patients who achieved complete ablation of all intrahepatic lesions. The overall patient survival period was defined as the period between the initial RFA and patients’ death. Complications were assessed with the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) Standards of Practice Committee classification [Citation12]. A major complication refers to an event that requires therapy or minor hospitalization (<48 h), requires major therapy, unplanned increases in level of care or prolonged hospitalization (>48 h), permanent adverse sequelae and death. Other complications were considered minor.

Statistical analyses

Survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method. The following 11 potential prognostic factors were analyzed: age, sex, primary GIST location, size of the largest metastatic tumor, number of metastatic tumors, location of metastatic tumors, distribution of metastatic tumors, extrahepatic metastasis before RFA, timing of liver metastasis, hepatic resection, and TKI therapy before RFA. The log-rank test was used for univariate analyses. A Cox proportional hazards model was developed to include all variables to determine the association between each variable and survival. The IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) was used for statistical analyses, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient recruitment began in March 2011 and ended in November 2022. We recruited 34 patients, of whom 34 (79 lesions) were eligible for inclusion. All 79 lesions achieved technical efficacy at the RFA sites. The median follow-up period for surviving patients was 33.1 (range, 3.8–159.5) months after RFA. During the final follow-up assessment,10 patients died. The average age was 52.7 ± 12.8 (range, 25–72) years. The average diameter of metastases was 2.4 ± 1.0 (range, 1.1–5.2) cm. Nine patients had solitary liver metastases (9/34, 26.4%), and 25 patients had multiple liver metastases (25/34, 73.6%). Five (5/34, 14.7%) patients had extrahepatic metastases before RFA. The initiation of genetic testing at our institution occurred in 2015, consequently rendering a subset of patients ineligible for such analysis. Among the 34 patients enrolled in this study, 22 underwent genetic testing. Among 22 patients who underwent mutational analysis, only one had no mutations in KIT, PDGFRA, or BRAF. The basic characteristics of all enrolled patients are listed in .

Table 1. The basic characteristics of 34 patients with liver metastasis from GIST.

Technical efficacy, local tumor progression, and new tumor development

The technical efficacy rate was 100% (79/79 lesions) according to the 1-month enhanced CT/MRI after RFA. LTP was observed in two (2.5%, 2/79) lesions of two (5.8%, 2/34) patients 5–40 months after RFA. Among them, one patient had an unfavorable response to imatinib, and one patient developed resistance to imatinib and regorafenib after 2-year therapy. After disease progression, they received systemic therapy. New tumor development was detected in 17 (50%) patients 1–40.7 months after RFA. Among them, two patients underwent repeat RFA, 11 received systemic therapy, three underwent hepatectomy and one underwent transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

Survival outcomes and prognostic analysis

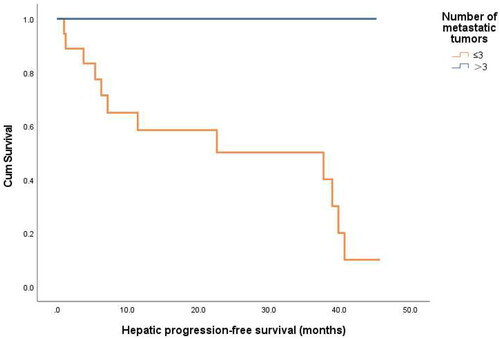

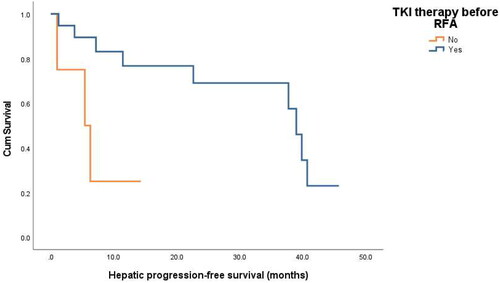

The mean overall survival (OS) period was 100.5 ± 14.1 (range, 3.8–159.5) months. The HPFS was analyzed in 23 patients who achieved successful ablation of all intrahepatic lesions. Among them, 11 showed development of new metastases in another part of the liver or local progression. The mean HPFS was 28.4 ± 3.8 (range, 1.0–45.7) months. The hepatic progression-free 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rate after RFA was 67.2%, 60.5%, 20.2%, respectively. Based on univariate analysis, the number of metastatic tumors (p = 0.045) and TKI therapy before RFA (p = 0.014) were identified as prognostic factors for HPFS ( and ). Multivariate Cox regression analyses showed that TKI therapy before RFA was associated with better HPFS (p = 0.030) ( and )

Figure 3. Hepatic progression-free survival curves for patients with or without TKI therapy before RFA (p = 0.014).

Table 2. Univariable and multivariable analyses of the risk factors for HPFS.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of HPFS factors with Cox proportional hazards in patients with liver metastasis from GIST after RFA.

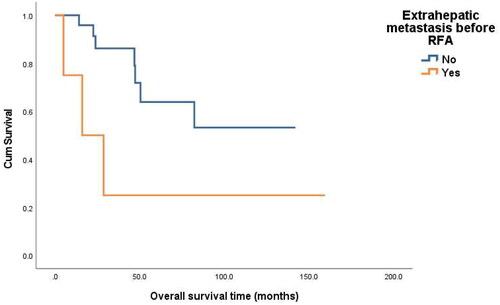

The overall 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 96.9%, 77.1%, and 58.7% respectively. Based on univariate analysis, extrahepatic metastasis before RFA (p = 0.044) was identified as a prognostic factors significantly related to OS ( and ). Multivariate Cox regression analyses showed that extrahepatic metastasis before RFA was associated with a worse OS(p = 0.044) ( and ).

Figure 4. Overall survival curves for patients with or without extrahepatic metastasis before RFA (p = 0.044).

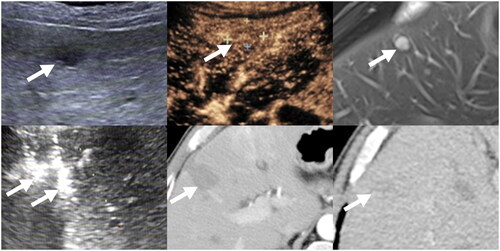

Figure 5. Images from a 60-year-old male with liver metastasis from GIST. (A) Ultrasound before RFA showed a 1.6 cm tumor in liver. (B) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound before RFA showed a 1.8 cm tumor with slight enhancement in liver. (C)MRI showed a 1.8 cm enhanced tumor (arrow) in liver. (D) with ultrasound guidance, two bipolar RFA electrodes (arrow) were inserted into the tumor (E)Contrast-enhanced CT one month after initial RFA showed ablation area showed ablation area had no viability. (F) Contrast-enhanced CT 6 months after initial RFA showed ablation area shrunk without local progression or new liver metastases.

Table 4. Univariable analyses of the risk factors for OS.

Table 5. Multivariate analysis of OS factors with Cox proportional hazards in patients with liver metastasis from GIST after RFA.

Among the 22 patients who underwent genetic testing, 21 narbored a KIT mutations. The median OS period for these patients with KIT mutations was 29.6 (range, 3.8–142) months, with survival rates of 100%, 91.7%, and 49.1% at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. Because of the low number of patients without mutations, survival analysis could not be performed to assess the effect of gene mutations on OS.

Complications

No major complications related to RFA. Minor complications occurred in 11.8% (4/34) of the patients. Among them, two patients experienced minor pleural effusion, one patient experienced fever, and one patient experienced peripheral biliary fistula (grade B according to ISGLS [Citation13] definition). Patient with biliary fistula was discharged two days after receiving catheter drainage treatment. All the patients recovered with conservative management.

Discussion

GIST metastases can be observed in the liver, peritoneum, lungs, bones, lymph nodes, and other locations, with liver being the most common site. Although imatinib is the standard of care for metastatic and advanced GISTs, achieving long-term complete remissions remains a challenge for clinicians. According to the NCCN guidelines, locoregional procedures, such as hepatectomy, ablation, and chemoembolization, are facultative approaches for liver metastases from GISTs [Citation3]. However, several patients with GIST liver metastases are not eligible for liver surgery because of multiple liver and extrahepatic metastases [Citation14]. Recognized as a minimally invasive and cost-effective treatment for liver tumors, RFA has demonstrated suitability as an option for individuals facing physical and financial challenges [Citation7]. Most liver metastases from GISTs display notably low echogenicity on routine ultrasound [Citation15,Citation16]. Therefore, further investigations into the long-term efficacy of ultrasound-guided RFA in patients with GIST liver metastases are warranted. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the long-term OS (>5 years) and prognosis of 34 patients with liver metastases from GISTs who underwent percutaneous RFA. Interestingly, we found that the prognostic factors for OS in patients with liver metastases from GIST after RFA was the presence of extrahepatic lesions prior to RFA, but conventional indicators of tumor prognosis, such as liver tumor size, tumor number, and TKI therapy, did not exhibit significant predictive value. This indicates that GIST liver metastases can be considered as a slow-progressing disease for the entire diagnostic and treatment process. Multimodalities treatments are required for long-term survival. Based on the available published reports [Citation15–20], our study has the longest follow-up study and largest ample size of patient sample of RFA in liver metastases from GISTs. This underscores the significance of our investigation for advancing the understanding and management of this condition.

Compared with the reported OS period (47.2–90.2 months) of patients with liver metastases from GISTs treated with RFA in previous studies [Citation6,Citation15,Citation16], our mean OS of 100.5 ± 14.1 months (range 3.8–159.5 months) was promising. This may be attributed to our large sample size (n = 34) and over 10-year follow-up period (range, 3.8–159.5 months) in our study. Chen et al. [Citation16] compared the prognosis of RFA (n = 10) and resection (n = 15) in patients with resectable liver metastases from GISTs after preoperative TKI treatment and suggested that there was no statistical difference in OS between RFA and hepatectomy (p = 0.413). Patterson et al. [Citation21] published the clinical results of locoregional treatments in 127 patients with metastatic GISTs and found that hazard ratio of OS between patients with metastases who underwent locoregional treatments, including RFA (n = 2) and MWA (n = 1), and those who did not remained significant at 0.46 (p = 0.01), indicating RFA qualifies to be included as part of multidisciplinary treatment. All these reports indicate that when ablation achieves technical success, RFA can produce the same survival benefits as surgery.

In a Chinese multicenter surgical study, Chen et al. [Citation14] studied the effects of hepatectomy (n = 43) in combination with TKIs for GIST liver metastases and showed that female sex, primary site of stomach, and liver surgery were influencing factors for long OS, and hepatectomy was the only prognostic factor for OS in multivariate analysis. However, these factors were not applicable in our study, possibly because patients with liver metastases unfavorable for surgical resection and extrahepatic metastases were excluded from their study, whereas patients in the present study were mostly treated with RFA as palliative care or supplemental treatment after exclusion from liver resection. In addition all patients in the present study underwent complete surgical resection of the primary lesions remarkably early, which might have decreased the effect of the primary sites on OS. Our study found that, although the patients in our study had worse physical condition than those in earlier researches, such as large tumor diameter (1.1–5.2 cm), extrahepatic metastasis, and multiple liver lesions (25/34 patients), 10 patient died during the 10-year follow-up period. Prior studies have also shown that patients with metastatic lesions < 3 cm have a higher rate of OS in cases of liver metastases from colorectal cancer [Citation22], breast cancer [Citation9], and lung cancer [Citation23]. However, in this study, the size of the metastatic lesions did not demonstrate a statistically significant correlation with OS (p = 0.333). This may be associated with the molecular and biological characteristics of GISTs. Small GISTs are characterized by benign biological behavior [Citation24], and ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS clinical practice guidelines suggest that patients can choose to undergo active surveillance as an alternative strategy, depending on their expected lifespan [Citation25]. However, the precise mechanisms underlying the invasion and development of liver metastases of GISTs remain unclear.

In the present study, we enrolled five patients with extrahepatic metastasis, and the results revealed that extrahepatic metastatic disease before RFA indicated worse OS in patients with GIST liver metastases. Previous studies [Citation8,Citation9] have also stated that RFA is a curative and locally efficient approach to treat breast cancer and pancreatic adenocarcinoma liver metastases, particularly in patients without extrahepatic metastasis (p < 0.001). Likely, a multicenter, randomized, international study (ENESTg1) indicated that patients with GISTs extrahepatic metastases had a significantly higher risk of progression and overall mortality [Citation26].

The prognostic analysis in our study also indicated that patients who received TKI treatment prior to RFA exhibited longer HPFS, which is consistent to Bauer et al. ’s [Citation27] finding that a short interval between imatinib treatment and surgery was a positive prognostic factor for PFS (p = 0.044). In our study, two patients developed LTP. One patient exhibited an unfavorable response to imatinib, while another developed resistance to both imatinib and regorafenib after a 2-year therapy. These findings suggest that patients with suboptimal responses to TKI treatment are more likely to experience LTP after RFA. Rapid tumor progression usually occurs after drug interruption [Citation25], and a previous study suggested that a continuous response to TKIs could lower the recurrence rate by increasing radiofrequency-induced coagulation in GIST metastases [Citation28]. These results were consistent with the guidelines that imatinib treatment should be indefinitely continued in the metastatic setting until clinically relevant disease progression or intolerance. Several studies [Citation29,Citation30] have demonstrated the relationship between micrometastases and poor outcomes, emphasizing the significance of this phenomenon in disease development. Based on the study of Chen et al. [Citation14], hepatic resection in conjunction with perioperative TKIs offers an advantage in terms of PFS compared with using postoperative TKIs alone because the presence of liver metastases in individuals with GISTs suggested that these tumors had spread from their primary site and might be accompanied by micrometastases. Hakime et al. [Citation18] reported that RFA should be performed at the time of best clinical response in patients maintained under TKI therapy after the procedure, which might be attributed to the extended duration between RFA and TKI treatment.

In surgical reports, the number of liver lesions was associated with poor local prognosis [Citation31,Citation32]. However, our findings diverge from this. All patients with >3 metastatic lesions received continuous targeted therapy in present study. Moreover, despite a higher number of metastatic lesions, their dimensions were all < 3 (range, 0.6–2.3) cm. The tumor burden was not heavy and we had successfully ablated all the liver lesions at initial RFA. To further investigate the relationship between tumor quantity and HPFS, future researchers will need to conduct studies with larger sample sizes. Genetic mutations play a crucial role in the selection of appropriate therapies for patients with metastatic GISTs [Citation33]. However, because of the limited number of mutation-negative patients in our study, survival analysis was not feasible to determine whether gene mutations influenced OS or HPFS after RFA treatment. In a surgical study, statistical analyses revealed no significant correlation between genetic mutations and prognosis [Citation27]. To further investigate the role of genetic mutations in RFA treatment, we plan to conduct a multicenter study with a larger sample size of patients with liver metastases from GISTs.

According to published studies [Citation15–20], most studies have enrolled no >20 patients with liver metastases from GISTs who underwent percutaneous or intraoperative RFA. In all documented patients with liver metastases from GISTs who underwent RFA, the reported incidence rate of complications was 14% (14/100). The major complication rate was 5% (5/100 patients), and the minor complication rate was 9% (9/100 patients). Our results are consistent with those of previous studies. RFA has a significant lower rate of complications and a shorter length of stay and improves the prospect multimodality treatment in cases of tumor recurrence.

This study has some limitations. First, most patients with GIST liver metastases received comprehensive treatments, including systemic therapy, liver resection, and RFA, therefore, the single potency of RFA for improving OS is difficult to completely distinguish. Second, as patients referred for ablative therapy for liver metastases from GIST often had multiple underlying comorbidities and poor physical condition, there might have been a potential selection bias in our study. Third, there was no set protocol for patients undergoing RFA in this study, except for a multidisciplinary discussion. Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, the present study had the largest study population focusing on RFA for liver metastases from GISTs. However, owing to its single-center and retrospective nature, further prospective studies are required.

In conclusion, our study reveals that pre-RFA liver metastasis is an independent detrimental prognostic factor in patients with liver metastases from GISTs undergoing RFA. Patients received targeted therapy before RFA can obtain extended HPFS. Despite the multifocal nature of GIST liver metastasis and the potential for post-RFA neogenesis, our study achieved an impressive 5-year OS rate of 58.7%. This suggests relatively slow-paced biological behavior. Consequently, RFA has emerged as a pivotal therapeutic modality for enhancing the quality of life and prolonging the OS for patients with liver metastases from GISTs.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Blay J-Y, Kang Y-K, Nishida T, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):22. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00254-5.

- Yang Z, Zheng R, Zhang S, et al. Incidence, distribution of histological subtypes and primary sites of soft tissue sarcoma in China. Cancer Biol Med. 2019;16(3):565–574. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2019.0041.

- von Mehren M, Kane JM, Riedel RF, et al. NCCN guidelines® insights: gastrointestinal stromal tumors, version 2.2022. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(11):1204–1214. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0058.

- Antonescu CR, DeMatteo RP. CCR 20th anniversary commentary: a genetic mechanism of imatinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumor-Where are We a decade later? Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(15):3363–3365. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3120.

- Fernández JÁ, Alconchel F, Gómez B, et al. Unresectable GIST liver metastases and liver transplantation: a review and theoretical basis for a new indication. Int J Surg. 2021;94:106126. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106126.

- Pawlik TM, Vauthey J-N, Abdalla EK, et al. Results of a single-center experience with resection and ablation for sarcoma metastatic to the liver. Arch Surg. 2006;141(6):537–543. discussion 543-544. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.6.537.

- Izzo F, Granata V, Grassi R, et al. Radiofrequency ablation and microwave ablation in liver tumors: an update. Oncologist. 2019;24(10):e990–e1005. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0337.

- Du Y-Q, Bai X-M, Yang W, et al. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation for patients with liver metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Hyperthermia. 2022;39(1):517–524. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2022.2048907.

- Bai X-M, Yang W, Zhang Z-Y, et al. Long-term outcomes and prognostic analysis of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation in liver metastasis from breast cancer. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;35(1):183–193. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2018.1488279.

- Yang W, Yan K, Wu G-X, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma in difficult locations: strategies and long-term outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(5):1554–1566. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i5.1554.

- Puijk RS, Ahmed M, Adam A, et al. Consensus guidelines for the definition of time-to-event end points in image-guided tumor ablation: results of the SIO and DATECAN initiative. Radiology. 2021;301(3):533–540. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203715.

- Sacks D, McClenny TE, Cardella JF, et al. Society of interventional radiology clinical practice guidelines. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14(9 Pt 2):S199–S202. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000094584.83406.3e.

- Koch M, Garden OJ, Padbury R, et al. Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the international study group of liver surgery. Surgery. 2011;149(5):680–688. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.12.002.

- Chen Q, Li C, Yang H, et al. Resection combined with TKI therapy for resectable liver metastases of gastrointestinal stromal tumours: results from three national centres in China. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(6):1330–1341. doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04278-x.

- Jung J-H, Won HJ, Shin YM, et al. Safety and efficacy of radiofrequency ablation for hepatic metastases from gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26(12):1797–1802. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.09.002.

- Chen Q, Li C, Yang H, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus resection for resectable liver metastases of gastrointestinal stromal tumours: results from three national centres in China. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2019;43(3):317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2018.10.012.

- Yamanaka T, Takaki H, Nakatsuka A, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for liver metastasis from gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(3):341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.11.021.

- Hakimé A, Le Cesne A, Deschamps F, et al. A role for adjuvant RFA in managing hepatic metastases from gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) after treatment with targeted systemic therapy using kinase inhibitors. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37(1):132–139. doi: 10.1007/s00270-013-0615-1.

- Jones RL, McCall J, Adam A, et al. Radiofrequency ablation is a feasible therapeutic option in the multi-modality management of sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36(5):477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.12.005.

- Yoon IS, Shin JH, Han K, et al. Ultrasound-Guided intraoperative radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection for liver metastasis from malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Korean J Radiol. 2018;19(1):54–62. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.19.1.54.

- Patterson T, Li H, Chai J, et al. Locoregional treatments for metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor in British Columbia: a retrospective cohort study from january 2008 to december 2017. Cancers. 2022;14(6):1477. doi: 10.3390/cancers14061477.

- Gillams AR, Lees WR. Five-year survival in 309 patients with colorectal liver metastases treated with radiofrequency ablation. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(5):1206–1213. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1258-5.

- Zhang Z-Y, Jiang A-N, Yang W, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation is an effective method for local control of liver metastases from lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:877273. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.877273.

- Fernández JÁ, Gómez-Ruiz ÁJ, Olivares V, et al. Clinical and pathological features of “small” GIST (≤2 cm). what is their prognostic value? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(5):580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.01.087.

- Casali PG, Blay JY, Abecassis N, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(1):20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.09.005.

- Blay J-Y, Shen L, Kang Y-K, et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib as first-line therapy for patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumours (ENESTg1): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(5):550–560. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70105-1.

- Bauer S, Rutkowski P, Hohenberger P, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with GIST undergoing metastasectomy in the era of imatinib – analysis of prognostic factors (EORTC-STBSG collaborative study). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(4):412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.12.020.

- Choi H. Response evaluation of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Oncologist. 2008;13 Suppl 2(S2):4–7. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.13-S2-4.

- Pantel K, Alix-Panabières C, Riethdorf S. Cancer micrometastases. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(6):339–351. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.44.

- Suh SW, Choi YS. Predictors of micrometastases in patients with barcelona clinic liver cancer classification B hepatocellular carcinoma. Yonsei Med J. 2017;58(4):737–742. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2017.58.4.737.

- Sutton TL, Walker BS, Billingsley KG, et al. Hepatic metastases in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: oncologic outcomes with curative-intent hepatectomy, resection of treatment-resistant disease, and tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy alone. HPB . 2022;24(6):986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2021.11.011.

- Xiao B, Peng J, Tang J, et al. Liver surgery prolongs the survival of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor liver metastasis: a retrospective study from a single center. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:6121–6127. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S187061.

- Kelly CM, Gutierrez Sainz L, Chi P. The management of metastatic GIST: current standard and investigational therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-01026-6.