Abstract

Objective

The aim of this retrospective study was to investigate the short-term and long-term efficacy of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) therapy for abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) and explore its potential influencing factors.

Materials and methods

A total of 80 patients with AWE who underwent HIFU therapy were retrospectively analyzed. Follow-ups were also conducted to evaluate the changes in lesion size and pain relief. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was applied to investigate factors influencing HIFU therapy for AWE.

Results

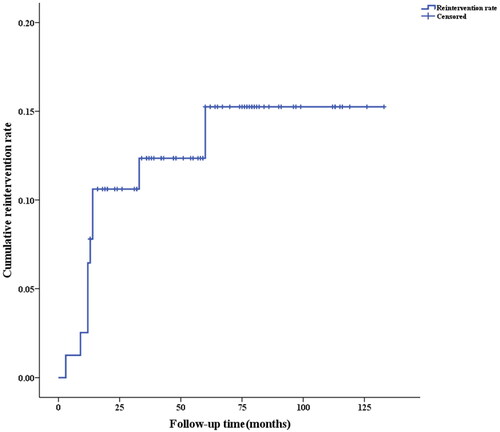

Among the 80 patients with AWE who received HIFU therapy, the effective rates were 76.3%, 80.5%, and 90.5% after 3, 12 and 24 months of follow-up, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that the AWE lesion diameter and sonication intensity had statistically significant effects on the 3-month and 12-month efficacy of HIFU therapy for AWE, while age, BMI, disease duration, average sonication power and grey-scale changes did not have statistically significant effects. Four patients with AWE experienced recurrence after HIFU therapy, for a three-year cumulative recurrence rate of 6.3%. Furthermore, ten patients required reintervention after treatment, for a five-year cumulative reintervention rate of 13.9%.

Conclusions

This study further confirmed the safety and effectiveness of HIFU therapy for AWE. Factors such as AWE lesion diameter and sonication intensity have been identified as key influencers affecting the short-term and long-term efficacy of HIFU therapy for AWE. The first two years following HIFU therapy constitute crucial periods for observation, and judiciously extending follow-up intervals during this timeframe is advised.

Introduction

Abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) refers to the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity within the abdominal wall layers between the peritoneum and the skin. It is the most common form of extrapelvic endometriosis [Citation1] and was first reported by Meyer in 1903 [Citation2]. The primary clinical manifestation of AWE is the presence of abdominal wall nodules with characteristic menstrual pain in the scar tissue following cesarean section, which often progresses over time [Citation3]. AWE can cause significant psychological distress and interfere with daily life. The treatment goals for AWE are to alleviate symptoms, reduce recurrence risk, and prevent malignant transformation. The primary treatment approach for AWE involves surgical excision. However, this procedure is invasive, leading to an extended recovery period, substantial pain, and potential complications such as tissue defects, subcutaneous hematoma, impaired wound healing, and incisional hernia [Citation4]. Pharmaceutical treatment for AWE is suboptimal and is mainly used to alleviate short-term pain symptoms, as it does not induce lesion shrinkage, and is easy recurrence after drug withdrawal [Citation5]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify a noninvasive, safe and effective treatment option.

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) therapy utilizes the physical properties of ultrasound waves, such as good penetration, focalization, and directionality, to focus multiple low-energy ultrasound beams from outside the body onto the target lesion within the body, generating high-energy effects, including thermal, mechanical, and acoustic cavitation effects [Citation6]. This leads to protein denaturation, coagulative necrosis of tissues, and destruction of the target lesion but spares surrounding tissues. Since its initial application, HIFU has been widely used for the noninvasive treatment of uterine fibroids [Citation7], adenomyosis [Citation8], cesarean scar pregnancies [Citation9], and placental implantation [Citation10,Citation11], and significant therapeutic effects have been observed in preliminary clinical studies. Luo et al. [Citation12] conducted a retrospective analysis of the clinical data of 32 AWE patients, and the follow-up results showed a significant reduction in the average volume of the AWE lesions and patient pain scores at 6 months after HIFU therapy. Zhu et al. [Citation13] compared the efficacy of HIFU therapy and surgery for AWE and found no significant difference in pain relief rates between the two methods. However, HIFU therapy has more advantages than surgery, such as no bleeding, no new scars, and lower pain scores immediately after treatment. Currently, reports analyzing the efficacy of HIFU therapy for AWE are based on small sample sizes [Citation12–16], and there is a lack of literature investigating the efficacy of HIFU therapy for AWE and its influencing factors.

The aim of this study was to address this gap by conducting a retrospective study and exploring the efficacy of HIFU therapy for AWE and its influencing factors, providing clinical evidence to possibly improve the effectiveness of HIFU therapy for AWE and reduce the rate of reintervention after HIFU therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients

The ethics committee of the Third Xiangya Hospital approved this study. From October 2012 to December 2022, 80 patients with AWE treated with HIFU therapy at Xiangya Third Hospital of Central South University were enrolled in our study. All patients signed an informed consent form at enrollment.

The inclusion criteria for patients with AWE were as follows: reproductive-aged woman (1) who had AWE lesions after uterine surgery, (2) who had cyclic abdominal pain symptoms related to the menstrual cycle, and (3) whose AWE lesion size and location were confirmed by ultrasound. Exclusion criteria included (1) pregnancy or lactation and (2) skin inflammation or ulceration within or near the lesion.

Ultrasound-guided HIFU treatment

HIFU therapy was performed with a JC200 focused ultrasound tumor therapeutic system (Chongqing Haifu Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China). This system includes both an ultrasound ablation treatment system and a real-time ultrasound-guided monitoring system. During HIFU treatment, a Mylab 70 color Doppler ultrasound machine with a probe frequency of 1–8 MHz was used.

Prior to HIFU treatment, all patients were required to undergo a three-day bowel preparation, and a urinary catheter was then inserted to control the bladder volume. Patients assumed a prone position on the treatment bed, with the abdominal skin in contact with the degassed water. Patients were monitored via continuous electrocardiography and received fentanyl citrate for analgesia [(0.8–1) μg/kg] and midazolam for sedation [(0.02–0.03) mg/kg]. Patients were instructed to report any discomfort during the HIFU treatment process. HIFU treatment was performed under real-time ultrasound guidance, ablating the abdominal wall nodules in a ‘point-line-plane-volume’ manner, gradually covering the target area. Generally, an output power of 50 W was used initially; if the grey-scale did not change obviously at the treated spot on ultrasound after energy exposure, the output power was increased at an increment of 10 W until the treated spot became hyperechoic on ultrasound. Treatment termination was determined based on the grey-scale changes observed in color Doppler ultrasound images [Citation16,Citation17].

Clinical analysis

Clinical data, including (1) general information and medical history, including age, body mass index (BMI), duration of symptoms before HIFU treatment, history of previous surgical excision of AWE lesions, and clinical symptoms; (2) ultrasonographic data collection, including measurement of AWE lesion diameter, number of lesions and lesion location; (3) intraoperative details, including average power of HIFU treatment, treatment time, sonication time, sonication intensity and grey-scale changes; and (4) follow-up data concerning clinical symptom improvement and reintervention, including the pain score after treatment evaluated by the visual analogue scale(VAS), occurrence of reintervention and reasons for reintervention, were collected from the Xiangya Third Hospital. The efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE and its influencing factors were statistically analyzed. Follow-up continued until December 1, 2023.

The VAS score [Citation18] was utilized to assess pain intensity at each follow-up time point. The reduction in pain intensity was calculated as (pretreatment VAS − posttreatment VAS)/posttreatment VAS × 100%. We defined ‘cure’ as a reduction in pain intensity exceeding 75%, ‘improvement’ as a reduction between 25% and 75%, and ‘ineffective’ as a reduction less than 25%, referring to the Clinical Practice Guidelines in Pain Medicine issued by the Chinese Medical Association [Citation19]. Recurrence was defined as a pain return of at least 80% of that experienced before treatment. The efficacy rates were calculated using the following formula: efficacy rate = (cure + improvement)/total number of patients × 100%.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 25.0. The normally distributed data were reported as the means ± standard deviations, whereas the skewed distribution data were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to statistically analyze factors that may affect the efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE. Missing data were not included in the statistical analysis. p < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Factors with odds ratios (ORs)> 1 were considered risk factors, and factors with ORs < 1 were considered protective factors at the test level α = 0.05.

Results

Basic clinical characteristics of patients

shows that the average age of the 80 patients was 32.98 ± 0.56 years (range: 23–46), with a median BMI of 21.77 kg/m2 (range: 20.04–24.57). The median duration of symptoms before HIFU treatment was 2 years (range: 1–4), and all patients with AWE had a history of previous cesarean section, with 5 patients (6.3%) having a history of previous AWE lesion excision. According to the clinical symptom analysis, 77 patients (96.3%) had palpable masses near the abdominal incision. Regarding the ultrasound parameters, the median lesion diameter was 25 mm (range: 17.25–34.75), 76 patients (95.0%) had a single AWE lesion, and 4 patients (5.0%) had two AWE lesions.

Table 1. Basic clinical Characteristics of AWE patients.

The median treatment time for HIFU was 64.5 min (range: 50.25–85.75), the median sonication time was 339 s (range: 225–507.5), and the median sonication power was 113.5 W (range: 96–143.75). The mean sonication intensity was 321.65 ± 10.096 s/h (range: 85–485). During treatment, 69 lesions (82.1%) exhibited agglomerative grey-scale changes, while 15 lesions (17.9%) exhibited overall grey-scale echogenicity changes (). All patients were satisfactorily sedated and administered analgesia during treatment, with no observed respiratory depression. One patient (1.25%) experienced immediate hematuria after treatment, 17 patients (21.25%) reported pain in the treatment area, and 10 patients (12.5%) reported skin burning sensations (). None of the patients experienced discomfort on the second day after treatment.

Table 2. Results of patients with AWE after HIFU treatment.

Table 3. Side effects or complications of patients with rectus abdominis endometriosis after HIFU treatment (n = 80).

Post-treatment efficacy and follow-up

A follow-up was conducted at 3, 12 and 24 months after HIFU treatment for the 80 AWE patients. Based on the reduction in abdominal wall nodule volume and improvement in clinical symptoms, the treatment efficacy rates were 76.3%, 80.5%, and 90.5% after 3, 12 and 24 months of follow-up, respectively (). Among the 5 patients with a history of AWE lesion excision, 3 were effective and 2 were ineffective after HIFU therapy, for an effective rate of 60%.

Table 4. The efficacy and follow-up of patients with AWE after treatment with HIFU ablation.

Among the 80 patients with AWE treated with HIFU, four patients (5.0%) experienced recurrence—three patients who underwent surgical excision of the lesions and one patient who had mild recurrent pain without treatment. The cumulative reintervention rate was 6.3% at three years.

Ten patients underwent reintervention after HIFU treatment for AWE. Among them, six patients underwent reintervention in the first 12 months, 2 patients at 13-24 months, and 2 patients after 24 months. Reinterventions mainly occurred within the first 2 years after treatment, with a 5-year cumulative reintervention rate of 13.9% (). Among the patients who underwent reintervention, 6 (60%) had ineffective HIFU treatment, 2 (20%) had recurrence, and 2 (20%) had concurrent cesarean section and excision of abdominal wall lesions.

Influencing factors of efficacy

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to analyze factors affecting the efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE by dividing patients into effective and ineffective groups. The results showed that lesion diameter (OR = 0.938, p = .022) and sonication intensity (OR = 1.009, p = .012) had statistically significant impacts on the 3-month efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE (p < .05), as shown in . Lesion diameter was a risk factor (OR = 0.952), while sonication intensity was a protective factor (OR = 1.010) in the analysis examining the 12-month efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE (). However, age, BMI, duration of illness, grey-scale changes, and number of lesions were not significantly correlated with treatment efficacy. There were no identified factors affecting the 24-month efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE (shown in Table 7 of the Supplement).

Table 5. Factors influencing 3-month efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE.

Table 6. Factors influencing 6-month efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE.

Discussion

AWE is a special type of endometriosis (EM) [Citation20] that occurs when endometrial tissue is scattered and implanted in the abdominal incision during abdominal uterine surgery, especially via cesarean section; this disease may progress to invade deeper tissue or even undergo malignant transformation [Citation21]. The clinical symptoms of AWE mainly include the presence of painful nodules near the abdominal wall incision, which are related to the menstrual cycle [Citation22]. Single or multiple indurated, irregular, immobile nodules can often be palpated during abdominal examination, accompanied by tenderness. The patients with AWE included in this study were of childbearing age, and ranged from 23 to 46 years. All of them had a history of cesarean section and exhibited typical clinical features of AWE, including abdominal wall pain and/or palpable abdominal wall masses. Zaraq Khan et al. [Citation23] conducted a case-control study showed that cyclic localized abdominal pain and previous laparotomy were independently associated with AWE. Therefore, for women of childbearing age with a history of cesarean section and painful nodules related to the menstrual cycle, AWE should be considered a plausible diagnosis.

The primary diagnostic method for AWE is ultrasound, which can determine the number and location of lesions as well as the lesion blood supply, with a positive predictive rate of up to 92.0% [Citation24]. However, when malignant transformation is suspected, MRI should also be considered [Citation25]. In this study, all AWE lesions were assessed by ultrasound, and the diameter ranged from 10-63 mm. Most patients (77 patients, 96.3%) had a single AWE lesion. Interestingly, 45.2% of the total AWE lesions were located on the right side of the scar, which corresponds with the findings of published reports [Citation26,Citation27]. We assumed that the surgeon’s position on the patient’s right side, increased intraoperative manipulation, inadequate protection of the incision, and incomplete washing might lead to an increased risk of residual endometrial tissue implantation on the right side of the abdominal wall incision compared to other sites.

Surgical excision is generally the preferred treatment for AWE, with a success rate of up to 95% [Citation4]. During surgery, the lesions and surrounding fibrous tissues need to be excised, which can result in tissue defects, subcutaneous hematomas, poor wound healing, and abdominal wall incisional hernias, especially in patients with severe defects, where patching or flap transplantation may be needed [Citation5]. Repeated abdominal surgeries not only increase physical and psychological trauma and financial burdens on patients but also increase the risk of adhesions and organ damage [Citation26]. With the increasing incidence of AWE and the younger age of affected individuals, finding a noninvasive, effective, and safe treatment approach to improve menstrual abdominal wall pain and reduce the harm of repeated treatments is a challenge for clinical physicians. HIFU has emerged as a novel practical and noninvasive method widely used to treat malignant tumors and other solid tumors. Wang [Citation28] et al. conducted a retrospective study among 67 AWE patients with 82 lesions successfully ablated with HIFU, and the patients’ pain scores significantly decreased at the 1-year follow-up. The safety and effectiveness of HIFU in treating AWE have been confirmed by multiple studies [Citation4,Citation12–16], but there is still a lack of reports on the short-term and long-term efficacy and factors influencing HIFU treatment for AWE due to the small sample sizes.

Previous literature suggested that the disappearance of symptoms was indicative of the benign lesions being cured [Citation29]. In this study, among the 80 patients with AWE treated with HIFU, the efficacy rates at the 3-, 12-, and 24-month follow-ups were 76.3%, 80.5%, and 90.5%, respectively, indicating that HIFU treatment for AWE is safe and effective, with efficacy improving over time. Furthermore, the present study revealed that, in five patients with a history of AWE lesion excision, HIFU treatment had an efficacy rate of 60%, suggesting that HIFU treatment may be a noninvasive treatment option for patients with AWE who have undergone multiple abdominal surgeries, potentially reducing physical and psychological trauma and financial burden. However, the size of the group of postsurgical patients was limited; therefore, further investigations in large cohorts are needed.

HIFU treatment focuses energy on target lesions under the guidance of real-time ultrasound, causing the lesions to necrose without damaging surrounding tissues [Citation30]. During the whole process of treatment, patients remain conscious and can provide immediate feedback on their treatment experiences, reducing the occurrence of HIFU complications. Common HIFU complications include localized skin burns or pain, skin blistering, and bladder injury which can be improved with the use of sedatives and analgesics, ice compress, and bladder irrigation [Citation28]. In this study, 28 of 80 patients experienced postoperative complications, all of which were completely relieved on the second day after surgery. According to the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) classification of adverse reactions [Citation31], all 28 patients were classified as SIR-A or B, and no severe complications occurred during treatment or follow-up. The study suggested that HIFU treatment for AWE is not only significantly effective but also associated with milder postoperative complications, making it a safe and effective treatment modality.

There have been reports of recurrence rates after abdominal wall lesion excision surgery ranging from 0% to 29% [Citation32–34], while the recurrence rates after AWE lesion excision surgery were estimated to range from 1.5% to 9.9% in Chinese studies [Citation35]. In our study, the follow-up period ranged from 13 to 133 months, which is the longest follow-up period reported in the literature. During later follow-up, four patients mostly experienced recurrence within three years after HIFU treatment, resulting in a cumulative 3-year recurrence rate of 6.3%, which is consistent with the findings of previous reports. In the analysis of patients requiring reintervention, 10 patients were readmitted for surgical removal of abdominal wall lesions after HIFU treatment, mainly in the first two years after treatment. This finding suggested that the first two years after HIFU treatment are important follow-up periods, and extending the follow-up interval may be appropriate. Among the six patients who needed reintervention due to ineffective HIFU treatment, two had histories of AWE lesion excision, suggesting that these patients may have higher endometrial activity, wider lesion dissemination, stronger lesion implantation and more severe lesion invasion.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the factors affecting the short-term (3 months) and long-term (12 months) efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE. The results showed that age, BMI, disease duration, grey-scale changes in the lesion, and the number of lesions were not significantly correlated with treatment efficacy. However, lesion diameter and sonication intensity were found to be factors influencing the efficacy (at 6 months) of HIFU treatment for AWE. The lesion diameter was identified as a risk factor for the efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE, while the sonication intensity was a protective factor. We concluded that the larger the lesion is, the deeper it infiltrates into the surrounding tissue, and the more challenging it becomes to ablate with HIFU. Preoperative communication may be necessary when patients have larger lesions. Properly increasing the sonication intensity may improve effectiveness, but care should be taken to avoid complications associated with excessive treatment, such as skin burns and bowel and nerve damage. However, no factors affecting the 24-month efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE were identified, possibly due to the small sample size, necessitating further large-sample prospective studies for validation.

This study has certain limitations. Although this was a retrospective study, and the sample size was relatively large compared to that of previous studies on HIFU treatment for AWE, bias may still exist. Large-sample prospective studies from multiple centers are needed to provide more reliable evidence for the treatment of AWE patients. The long follow-up duration in this study led to the loss of patients to follow-up and missing data.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study further confirmed that HIFU treatment for AWE was a safe and effective option for AWE patients, the efficacy of which increased over time. HIFU treatment may be a noninvasive treatment option for patients with AWE with a history of multiple abdominal surgeries. The lesion diameter and treatment intensity were found to be factors influencing the short-term efficacy of HIFU treatment for AWE. Our findings also provide evidence for clinical guidance to possibly improve the effectiveness of HIFU therapy for AWE.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Third Hospital of Central South University in China (approval No.2023-S726). Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals.

Consent form

Data had been anonymized and written informed consent for publication was obtained from individuals described with personal details.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participating patients for their involvement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24412537.v3.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Foley CE, Ayers PG, Lee TT. Abdominal wall endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2022;49(2):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2022.02.013.

- Bergqvist A. Different types of extragenital endometriosis: a review. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1993;7(3):207–221. doi: 10.3109/09513599309152504.

- Benedetto C, Cacozza D, de Sousa CD, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: report of 83 cases. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;159(2):1–7. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14167.

- Zhao L, Deng Y, Wei Q, et al. Comparison of ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation and surgery for abdominal wall endometriosis. Int J Hyperthermia. 2018;35(1):528–533. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2018.1511836.

- Gunes M, Kayikcioglu F, Ozturkoglu E, et al. Incisional endometriosis after cesarean section, episiotomy and other gynecologic procedures. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2005;31(5):471–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2005.00322.x.

- Bachu VS, Kedda J, Suk IAN, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound: a review of mechanisms and clinical applications. Ann Biomed Eng. 2021;49(9):1975–1991. doi: 10.1007/s10439-021-02833-9.

- Liu L, Wang T, Lei B. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation versus surgical interventions for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(2):1195–1204. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08156-6.

- Huang YF, Deng J, Wei XL, et al. A comparison of reproductive outcomes of patients with adenomyosis and infertility treated with High-Intensity focused ultrasound and laparoscopic excision. Int J Hyperthermia. 2020;37(1):301–307. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2020.1742390.

- Wang W, Chen Y, Yang Y, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound compared with uterine artery chemoembolization with methotrexate for the management of cesarean scar pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;158(3):572–578. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14036.

- Abd Elazeem HAS, Saad MM, Ahmed IA, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound in management of placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;151(3):325–332. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13391.

- Lin Z, Gong C, Huang Q, et al. A comparison of results following the treatment of placenta accreta and placenta increta using high-intensity focused ultrasound followed by hysteroscopic resection. Int J Hyperthermia. 2021;38(1):576–581. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2021.1909149.

- Luo S, Zhang C, Huang JP, et al. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for abdominal wall endometriosis: a retrospective study. BJOG. 2017;124(S3):59–63. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14741.

- Zhu X, Chen L, Deng X, et al. A comparison between high-intensity focused ultrasound and surgical treatment for the management of abdominal wall endometriosis. BJOG. 2017;124(S3):53–58. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14737.

- Zhang L, Rao F, Setzen R. High intensity focused ultrasound for the treatment of adenomyosis: selection criteria, efficacy, safety and fertility. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):707–714. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13159.

- Xiao-Ying Z, Hua D, Jin-Juan W, et al. Clinical analysis of high-intensity focussed ultrasound ablation for abdominal wall endometriosis: a 4-year experience at a specialty gynecological institution. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36(1):87–94. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2018.1534276.

- Shi S, Ni G, Ling L, et al. High-Intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of abdominal wall endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(3):704–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.06.012.

- Wang Y, Wang W, Wang L, et al. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for abdominal wall endometriosis: preliminary results. Eur J Radiol. 2011;79(1):56–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.12.034.

- Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, et al. Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(6):1073–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.08.016.

- Chinese Medical Association. Clinical practice guidelines: Pain studies volume. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2007. Chinese.

- Arkoudis NA, Moschovaki-Zeiger O, Prountzos S, et al. Caesarean-section scar endometriosis (CSSE): clinical and imaging fundamentals of an underestimated entity. Clin Radiol. 2023;78(9):644–654. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2023.05.020.

- Carsote M, Terzea DC, Valea A, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis (a narrative review). Int J Med Sci. 2020;17(4):536–542. doi: 10.7150/ijms.38679.

- Kang J, Baek JH, Lee WS, et al. Clinical manifestations of abdominal wall endometriosis: a single center experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287(2):301–305. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2565-2.

- Khan Z, Zanfagnin V, El-Nashar SA, et al. Risk factors, clinical presentation, and outcomes for abdominal wall endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(3):478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.01.005.

- Zhao X, Lang J, Leng J, et al. Abdominal wall endometriomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;90(3):218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.05.007.

- Liu G, Wang Y, Chen Y, et al. Malignant transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis: a systematic review of the epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;264:363–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.08.006.

- Zhang P, Sun Y, Zhang C, et al. Cesarean scar endometriosis: presentation of 198 cases and literature review. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):14.

- Yang Q, Zhang X. Efficacy and safety of high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for rectus abdominis endometriosis: a 7-year follow-up clinical study. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2023;13(3):1417–1425. doi: 10.21037/qims-22-695.

- Wang S, Li BH, Wang JJ, et al. The safety of echo contrast-enhanced ultrasound in high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for abdominal wall endometriosis: a retrospective study. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2021;11(5):1751–1762. doi: 10.21037/qims-20-622.

- Ahmed M, Solbiati L, Brace CL, et al. Image-guided tumor ablation: standardization of terminology and reporting criteria—a 10-year update. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25(11):1691–1705.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.08.027.

- Dababou S, Marrocchio C, Scipione R, et al. High-Intensity focused ultrasound for pain management in patients with cancer. Radiographics. 2018;38(2):603–623. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170129.

- Marinova M, Huxold HC, Henseler J, et al. Clinical effectiveness and potential survival benefit of US-guided High-Intensity focused ultrasound therapy in patients with Advanced-Stage pancreatic cancer. Ultraschall Med. 2019;40(5):625–637. doi: 10.1055/a-0591-3386.

- Leite GK, Carvalho LF, Korkes H, et al. Scar endometrioma following obstetric surgical incisions: retrospective study on 33 cases and review of the literature. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127(5):270–277. doi: 10.1590/s1516-31802009000500005.

- Lopez-Soto A, Sanchez-Zapata MI, Martinez-Cendan JP, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: presentation of 33 cases and literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;221:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.11.024.

- Stehouwer BL, Braat MNG, Veersema S. Magnetic resonance Imaging-Guided High-Intensity focused ultrasound is a noninvasive treatment modality for patients with abdominal wall endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(7):1300–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.03.018.

- Nominato NS, Prates LF, Lauar I, et al. Caesarean section greatly increases risk of scar endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;152(1):83–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.05.001.