Abstract

Background: There is a pressing need for effective treatments for major depressive disorder (MDD).

Objective

To examine the feasibility of an integrated mind-body MDD treatment combining cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and whole-body hyperthermia (WBH).

Methods

In this single-arm trial, 16 adults with MDD initially received 8 weekly CBT sessions and 8 weekly WBH sessions. Outcomes included WBH sessions completed (primary), self-report depression assessments completed (secondary), and pre-post intervention changes in depression symptoms (secondary). We also explored changes in mood and cognitive processes and assessed changes in mood as predictors of overall treatment response.

Results

Thirteen participants (81.3%) completed ≥ 4 WBH sessions (primary outcome); midway through the trial, we reduced from 8 weekly to 4 bi-weekly WBH sessions to increase feasibility. The n = 12 participants who attended the final assessment visit completed 100% of administered self-report depression assessments; all enrolled participants (n = 16) completed 89% of these assessments. Among the n = 12 who attended the final assessment visit, the average pre-post-intervention BDI-II reduction was 15.8 points (95% CI: −22.0, −9.70), p = 0.0001, with 11 no longer meeting MDD criteria (secondary outcomes). Pre-post intervention improvements in negative automatic thinking, but not cognitive flexibility, achieved statistical significance. Improved mood from pre-post the initial WBH session predicted pre-post treatment BDI-II change (36.2%; rho = 0.60, p = 0.038); mood changes pre-post the first CBT session did not.

Limitations

Small sample size and single-arm design limit generalizability.

Conclusion

An integrated mind-body intervention comprising weekly CBT sessions and bi-weekly WBH sessions was feasible. Results warrant future larger controlled clinical trials.

Clinivaltrials.gov Registration: NCT05708976

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), major depressive disorder (MDD) afflicts more than 280 million people worldwide and is a leading cause of life-years lost to disability [Citation1]. Part of this burden derives from the fact that currently available pharmacologic modalities have important shortcomings, including limited efficacy, delayed onset of action, and significant side effects that impair quality of life and promote treatment non-adherence and/or discontinuation [Citation2–4]. Only 30% of participants achieve symptomatic remission following initial pharmacologic treatment [Citation5]. Although using additional antidepressant medications in people who do not respond to initial therapy can increase overall response rates, the incremental chances of success decline with each additional therapy tried [Citation2]. The limitations of currently available treatments for MDD [Citation3] have stoked interest in treatments with novel mechanisms of action, in particular, non-pharmacologic approaches. There is therefore a strong need for additional safe and effective treatment options that may augment existing treatment options by addressing novel treatment targets.

Growing evidence suggests that body temperature may be a meaningful treatment target in depression. Observational and experimental studies show intriguing links between body temperature and depression. These studies suggest possible mechanistic pathways that may link WBH to improvements in depressed mood by altering mood-related elements of body temperature regulation. Observational human studies have shown that compared to healthy controls, persons with affective disorders have dysregulated thermoregulatory processes that manifest in elevated body temperature [Citation6–8]. For example, in a sample of adults with hypertension, body temperature (relative to dozens of other candidate variables) best differentiated individuals with versus without depression; individuals with depression had an average temperature that was 0.16 °C higher than did those without depression [Citation8]. In addition to elevated body temperature, patients with depression have altered discriminative responses to heat, perceive heat stimuli as more unpleasant, and have elevated nighttime body temperatures without corresponding increases in nocturnal sweating, relative to healthy controls [Citation7,Citation9,Citation10]. Increased body temperature at night, a time when thermoregulatory cooling responses are critical for sleep onset and quality, is arguably the most consistently observed circadian abnormality in depression [Citation6,Citation11,Citation12]. This elevated nighttime body temperature, however, regularizes upon clinical improvement in depression, such as following electroshock convulsive therapy, efficacious pharmacotherapy, or spontaneous reductions in depressive symptoms [Citation6,Citation9,Citation13]. Thus, there is evidence for a potentially mechanistic role of body temperature in depression.

Whole-body hyperthermia (WBH) is a treatment modality that targets thermoregulatory processes by acutely raising body temperature (which induces sweating and subsequent cooling) [Citation14–16]. WBH is rooted in traditional and integrative health practices, such as sauna, sweat lodges, and hot yoga, that have been reputed to have beneficial effects on mood [Citation17]. The wide variability of heat sources, durations, ceremonies, social factors, and other components of these indigenous practices underscore their independent development in multiple societies. Although differences across these practices make it difficult to draw on a single “traditional protocol,” their unifying commonalities (applying heat to an extent that is likely to increase body temperature and reputed to improve mood) point to an underlying recognition of potential benefit that has received little scientific attention. To date, WBH, delivered using infrared heating devices, hyperthermic baths, and hot yoga, has shown promise in improving mood in people with depression [Citation14,Citation15,Citation18,Citation19]. Notably, individuals have experienced improvements in depressed mood after single WBH treatments: Two small clinical trials reported statistically significant decreases in depressive symptoms among individuals with clinical depression following a single WBH treatment using an infrared heating source [Citation14,Citation18]. Although promising, the longer of these two trials followed participants for merely 6 weeks, and participants did not receive any additional treatment.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a manualized, highly disseminable and efficacious treatment for depression that targets psychological processes, such as negative automatic thinking and cognitive distortions, which can underpin depressive symptoms [Citation20]. CBT can be delivered in a time-limited fashion (e.g. an eight-session protocol) by a diverse range of mental health clinicians. Marriage and family therapists (MFTs), clinical social workers (CSWs), and other masters and doctoral level behavioral health clinicians can provide this manualized treatment, for which dozens of manuals, workbooks, and therapist guides are available [Citation21,Citation22]. In many areas, services provided by MFTs and CSWs are more readily available and affordable than those of clinical psychologists. The fact that there are validated methods for ensuring clinician fidelity to CBT [Citation23,Citation24] further strengthens its potential for dissemination. Despite these strengths, a substantial proportion of people with major depression do not reach remission with CBT alone, or are left with residual depressive symptoms [Citation25].

As an initial step in assessing whether adding WBH to CBT improves depression outcomes, we developed a combined intervention using widely accessible components and tested its feasibility and acceptability. We provided adults with depression with WBH sessions in a commercially available infrared WBH device using a protocol we previously developed and tested [Citation26]. We also provided a manualized CBT protocol using an established treatment schedule [Citation22]. Whereas WBH targets thermoregulatory processes that may underpin depression [Citation16], CBT targets negative automatic thinking, cognitive distortions, and faulty core beliefs [Citation21,Citation22]; thus, these two treatments target distinct mechanistic pathways. As CBT for depression is well established as feasible and acceptable, our feasibility and acceptability outcomes were the number of WBH sessions completed and participant retention; our secondary outcomes included change in pre-post intervention depression symptoms and number of self-report depression assessments completed. Though this trial was primarily focused on feasibility and acceptability, our secondary outcomes also included pre-post-intervention changes in two key theoretical targets of CBT, specifically, cognitive flexibility and negative automatic thinking. We also examined changes in depression symptoms at different resolutions (e.g. daily, weekly) to explore when we might first observe improvements in depression (i.e. after the first WBH session) [Citation14,Citation18]. Finally, we explored whether early treatment response, specifically changes in mood from before to after the first of each of the study treatments (CBT and WBH), predicted overall pre-post-intervention changes in depression symptoms.

Methods

Participants

We enrolled participants in the San Francisco Bay Area between November 2021 and January 2023. We recruited participants via social media, posted flyers, UCSF email marketing, and MyChart messages/Dear Patient letters. Eligible participants were men and women aged 18 to 70 years with a primary diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) based on a clinician-administered Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5-RV) [Citation27] and a BDI-II score of 21 or greater (exclusive of the suicide item) that did not decrease by more than 30% between two screening assessments. Eligible participants were not using medications or drugs with known effects on thermoregulatory processes and met other inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Appendix A. Exclusion criteria were largely based upon feasibility and safety. Specifically, we excluded women who were pregnant or at risk of becoming pregnant, as WBH may negatively impact pregnant persons and/or fetal outcomes [Citation28]. Due to prior work suggesting lack of improvements in depression symptoms in individuals using antidepressant medications [Citation14], we excluded individuals using these medications.

Procedures

The University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all study procedures and all participants provided electronic consent for screening activities (IRB Approval# 21-34246) and written informed consent for study participation. The UCSF IRB designated the commercially available WBH device as posing non-significant risk (NSR), consistent with US Food and Drug Administration good guidance practices regulations (21 CFR 12). This research was performed in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. We registered this trial on Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05041361).

Online and phone screening

All participants completed an initial online screening to confirm eligibility, which began with participants providing electronic consent for study screening activities. The initial screening included questions to ensure eligibility, including the use of excluded medications and medical conditions (see Appendix A), as well as the BDI-II (without the suicide question #9). If eligible after completing this initial online screen, participants completed a telephone screening wherein study staff asked additional eligibility questions (e.g. ensured that participants provided a complete list of medications and medical conditions for the study medical monitor to review) and explained study procedures. After these discussions, eligible and willing participants scheduled their baseline visit. The day before their scheduled baseline visit, participants completed an online screening that included a second BDI-II (also without the suicide question #9). If a participant’s initial online screening was completed more than 21 days prior to their baseline visit, we administered an additional online BDI-II (also without the suicide question #9) 7-10 days before the participant’s scheduled baseline visit. To be eligible, participants’ BDI-II scores had to be 21 or greater at their final two online screenings and their score must not have fallen >30% between the two screenings.

In-person screening and baseline visit

At the baseline visit, participants completed further screening activities, including self-report measures, anthropometric assessments, and (if female) a urine pregnancy test. A study clinician completed a clinical interview to ensure eligibility (to be eligible, a participant’s primary diagnosis had to be MDD). If the participant was eligible after all screening procedures, study staff reviewed the full study consent form with the participant and answered any participant questions. Study staff also reviewed key study procedures including asking participants to refrain from: (a) using a sauna outside of the study during the 10-week study period; (b) using alcohol, nicotine, or psychoactive drugs for 24 h before and 24 h after each WBH session; and (c) doing vigorous exercise the day of each WBH session. If participants were eligible and agreed to these key study procedures, participants provided written consent. Beginning the morning after the baseline visit, participants received a daily text message that contained a link to a brief survey of depression symptoms.

Study interventions

Participants received eight weekly CBT sessions with a study therapist and eight weekly (or four bi-weekly) WBH sessions (see below for study intervention details). As the primary outcomes of this study were feasibility and acceptability, we reviewed participant and staff feedback after the first six participants had completed the intervention. After these six participants had completed their participation, we reduced the number of WBH sessions from eight weekly sessions to four bi-weekly (every other week) sessions based on participant feedback and scheduling challenges.

Study intervention: whole-body hyperthermia (WBH)

We administered WBH using the Clearlight Sauna Dome and ancillary equipment (Mindray iPM-9800) to assess core body temperature via continuous rectal measurement. The Clearlight Sauna Dome uses far-infrared heating elements made of carbon fiber sheets and ceramic. Sauna Dome ambient temperatures reached approximately 57.2 °C and we heated participants until they achieved a core (rectal) body temperature of 38.5 °C or until the maximum permitted WBH time had passed. The maximum permitted WBH time was originally 110 min (which included the first 25 WBH sessions, of which 10 were terminated because 110 min had passed). We received sponsor and IRB approval to extend this time to 140 min to allow for additional time to achieve target core body temperature for some participants (see Results for number of participants/sessions impacted by this change). After extending the allowable time to 140 min, only 4 of 54 WBH sessions surpassed 110 min, and the average length of these four sessions was 123.2 min (SD = 8.9 min). During WBH sessions, two study staff remained with the participant. One study staff sat on a chair near the participant’s head and applied cool cloths and ice to the participant’s head and neck and provided the participant with electrolyte beverages and/or water to drink as often as the participant requested it. A second study staff monitored the participant’s core body temperature on the Mindray iPM-9800 (yields one temperature reading every 60 s), which was attached to an indwelling rectal probe that participants inserted before the start of each WBH session. After participants reached a core body temperature of 38.5 °C for two consecutive minutes, we removed the WBH domes and cover the participant in warm towels, and on average participants’ body temperature increased to 38.63 °C (SD = 0.15 °C) and remained at or above 38.5 °C for 15.0 min (SD = 8.8 min) before decreasing.

Study intervention: cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

Two PhD-level clinicians provided eight weekly 50-min CBT sessions, following a standard CBT for depression protocol (). The investigators developed the CBT protocol based on Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond, 3rd Edition [Citation22]. CBT sessions focused on modifying behaviors (i.e. behavioral activation) and challenging dysfunctional cognitive processes [Citation21]. outlines the session-by-session agenda and the out-of-session homework that the clinician assigned the participant to complete between sessions. Participants chose to complete CBT sessions in-person or via remote video sessions using Zoom; they were able to complete as many sessions as they wished via either modality.

Table 1. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) session content and between-session homework.

Final visit

After completing all intervention visits, participants attended a final visit during which they completed self-report measures and a study clinician again administered a clinical interview (SCID-5-RV) to assess for a diagnosis of MDD.

Measures

Clinician-administered assessments

At the baseline visit, a study clinician administered a research version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5-RV) [Citation27] that included assessments for MDD and other mental health disorders (e.g. bipolar disorder, eating disorders) to ensure eligibility. The study clinician also verbally administered the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ) [Citation29]. A study clinician re-administered the SCID-5-RV at the final visit.

Self-report assessments

We administered all self-report measures (e.g. online screening questionnaires, in-person self-report measures) online using the Qualtrics platform [Citation30]; we administered in-person questionnaires on a dedicated study iPad.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [Citation31]

The BDI-II is a 21-item measure of depression symptoms. Respondents rate each item on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3; each item contains unique response options. The total score is computed as a sum of all items, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. A clinically meaningful reduction in BDI-II scores has been described as 3-9 points [Citation32] and as a 17.5% decrease from baseline [Citation33]. Participants completed the BDI-II as part of eligibility screening as well as the night before their baseline visit (however, participants completed the BDI-II suicide item during the baseline visit as a clinician was available to assess positive responses). Participants completed the full 21-item BDI-II at the beginning of each CBT study visit, and at the final assessment visit. Change in the BDI-II from baseline to final assessment visit was our a priori measure of change in depressive symptoms listed in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT NCT05041361).

Patient Reported Outcomes Measures (PROMIS) Profile-29 v2.1 [Citation34]

The PROMIS-29 Profile v2.1 includes 29 items that assess measures of depression (4 items), physical function (4 items), anxiety (4 items), fatigue (4 items), sleep disturbance (4 items), ability to participate in social roles and activities (4 items), pain interference (4 items), and pain intensity (1 item). Each 4-item measure is scored individually by computing raw summed scores and converting these scores to T-scores using published tables [Citation35]. Respondents rate all items on a 5-point scale, except for the single item for pain intensity, which respondents rate on an 11-point scale (0-10); the pain intensity item is used in a raw score form (without T-score conversion). Higher scores on the depression, anxiety, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and pain interference scales indicate worse function (e.g. greater depression, greater anxiety). Higher scores on physical function and ability to participate in social roles and activities indicate better function (e.g. greater physical function). A clinically meaningful reduction in a PROMIS measure is 3-4 points [Citation36]. We administered the PROMIS-29 at the baseline and final assessment visits.

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Short Form v1.0 Depression 8a [Citation34]

The PROMIS Depression 8a is an expanded measure of depressed mood; it includes the 4 depression items from the PROMIS-29 as well as 4 additional items. These items are specific to depressed mood (it does not include several of the less specific symptoms that can be associated with depression, such as disturbances in sleep, fatigue, sexual function, and appetite). We administered the PROMIS Depression 8a daily via SMS text message between participants’ baseline and final assessment visits. We used the Health Measures Scoring Service for PROMIS Depression 8a, which can accommodate missing items by using response pattern scoring [Citation34, Citation37]; due to a technical administration error, some surveys were missing 1 of the 8 items.

Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire-Revised (ATQ-R), negative automatic thoughts [Citation38]

The Negative Automatic Thoughts scale of the ATQ-R is a 30-item measure of negative automatic thinking, which is a cornerstone of the cognitive behavioral theory of depression [Citation39, Citation40]. Respondents rate all items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (all the time). The total Negative Automatic Thoughts score is computed as a sum of all items, with higher scores indicating greater negative automatic thinking. We administered the ATQ-R at the baseline and final assessment visits.

Cognitive Flexibility Inventory (CFI) [Citation41]

The CFI is a 20-item measure of cognitive flexibility, which researchers have theorized is necessary for individuals to successfully challenge and change maladaptive thoughts with more balanced and adaptive thoughts. Respondents rate all items on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Negatively worded items are reverse scored, and the total score is computed as a sum of all items, with higher scores indicating greater cognitive flexibility. We administered the CFI at the baseline and final assessment visits.

Brief Mood Introspection Scale (BMIS) [Citation42]

The BMIS is a 17-item measure that assesses mood states and yields multiple scores. We analyzed the total pleasant-unpleasant score, which is computed as a sum of 16 items that respondents rate on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (definitely do not feel) to 4 (definitely feel); with higher scores indicating more pleasant mood. We also analyzed the overall mood score, which is the value of respondents’ answer to a single item asking, “overall, my mood is…” which they rate on a visual analogue scale ranging from −10 (very unpleasant) to 10 (very pleasant). We administered the BMIS before and after each CBT and WBH session.

Whole-body hyperthermia (WBH) protocol adherence

At each WBH study visit, participants completed adherence questions on the study iPad. These questions queried participants about whether they had recently used nicotine or psychoactive drugs, if they had engaged in heat-related activities (e.g. saunas, hot tubs) outside of the study, if they had done any vigorous exercise prior to coming in for their WBH visit that day, and if they had used alcohol or marijuana in the prior 24 h. Participants were also asked to report if they had started any new medications.

Adverse events (AEs)

Before and after each WBH session, participants responded to several face-valid questions about health symptoms that may arise in response to heat therapies (i.e. lightheadedness, headache, nausea) using yes/no response options, and were also able to report on any additional symptoms. If participants endorsed any symptoms, staff asked participants for details on the time of onset (before the WBH visit, during the WBH session, during cooldown, or after a 30-min cooldown), and the current severity (none, mild, moderate, severe, or very severe) of the symptom.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) clinician fidelity

We audio recorded each CBT session, and a PhD level clinician with expertise in CBT for depression used the Cognitive Therapy Scale-Revised (CTS-R) [Citation23, Citation24] to code one randomly selected session for half of study participants. We used an average across all sessions to compute an overall fidelity score. CTS-R scores range from 0 to 72, with a minimum competence standard being a score of 36.

Statistical analysis

Primary outcome

The primary study outcome was the number of planned WBH sessions completed. As the first 6 participants were offered 8 WBH sessions, and the final 10 participants were offered 4 WBH sessions, we computed completion rates separately for these two groups of participants. To assess the overall feasibility of the final protocol, we also assessed the total number of participants who completed at least 4 WBH sessions.

Secondary outcomes

One secondary outcome was the average number of planned self-report depression (BDI-II) assessments completed; to assess this we computed the number and percentage of BDI-II assessments completed by (1) individuals who attended the final assessment visit, (2) participants who discontinued participation prior to the final assessment visit, and (3) all study participants combined. Another secondary outcome was change in BDI-II scores from the baseline visit to the final visit (10-12 weeks later); to assess this we computed paired t-tests comparing BDI-II scores at baseline and at post-treatment. Additionally, to maximally include data from participants lost to follow-up, we computed linear mixed effects regression analyses with visit (baseline or final) predicting BDI-II scores.

Additional outcomes

In addition to the primary and secondary outcomes registered on clinicaltrials.gov, we report on participant characteristics, retention, CBT clinician fidelity, WBH protocol adherence, and adverse events (AEs). We tabulated all mild, moderate, and severe adverse events, and quantified the frequency of each type of reported event.

Changes in mood early in treatment

Given prior work showing rapid improvements in mood following WBH [Citation14, Citation18], we compared (1) daily level changes in depression symptoms (PROMIS Depression 8a) from immediately (one or two days, using the most proximal) before the first WBH session to immediately after the first WBH session (one or two days after, using the most proximal), (2) weekly level changes in depression symptoms (average of daily PROMIS Depression 8a) from the week before to the week after the first WBH session, (3) change in the BDI-II from approximately one week before to one week after the first WBH session, and (4) change in mood (BMIS [Citation42]) from immediately before to immediately after the first WBH session and from immediately before to immediately after the first CBT session. To compare the average change in BMIS mood scores from immediately before to immediately after each session (separately using the single mood item score and the total score), we used linear mixed models (separate models for WBH and for CBT). We also computed overall changes in mood from before to after all WBH and CBT sessions.

Overall treatment response

We explored overall treatment response by computing the number and percentage of participants no longer meeting DSM-5 criteria for MDD at post-treatment. We also computed the number of participants who achieved a minimal clinically important reduction in BDI-II scores (≥17.5%Citation33] as well as the number of participants who achieved a larger reduction in BDI-II scores (≥50%). We computed these values for participants who attended the final assessment visit (n = 12); we also computed these values for participants who completed at least one CBT session and at least one WBH session by using the last obtained BDI-II assessment (last observation carried forward; LOCF; n = 15). We also computed the difference between a one-week average of daily depression assessments at baseline (average of up to 7 morning PROMIS Depression 8a assessments between the baseline visit and the first study intervention visit), and a corresponding one-week average at post-intervention (the average of up to 7 morning PROMIS Depression 8a assessments between the last intervention visit and the final assessment visit).

Changes in mood early in treatment as a predictor of overall treatment response

To explore if early changes in mood in response to the first administration of each treatment component (WBH, CBT) predicted pre-post intervention changes in depression symptoms, we used linear regression to assess whether change in mood from before to after the first WBH and CBT sessions predicted treatment outcomes (i.e. change in BDI-II scores from baseline to post-treatment), and also calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for the correlation between (1) pre-post-session changes in mood (for each of: the first WBH session and the first CBT session) and (2) change in depressive symptoms from the baseline to post-treatment. Because this was a feasibility trial with only preliminary, exploratory estimates of other outcome measures, we did not control for multiple comparisons [Citation43].

Depression-related symptoms

We explored pre-post-treatment changes in other factors with known associations with depression, including sleep disturbance, anxiety, fatigue, social role function, and pain interference and intensity using paired t tests.

Automatic thoughts and cognitive flexibility

Given prior work showing that changes in cognitive flexibility and automatic thinking are key mechanistic targets of CBT for depression [Citation41, Citation44], we examined pre-post-treatment change in cognitive flexibility (CFI) and automatic thinking (ATQ-R).

Differences between participants offered 4 versus 8 WBH sessions

We recomputed the above analyses separately for participants who received 4 versus 8 WBH sessions.

Results

Primary outcome

Of the 6 participants offered 8 WBH sessions (37.5% of participants), 5 completed all 8 sessions and 1 completed 7 sessions. Of the 10 participants offered 4 WBH sessions (62.5% of participants), 7 completed all 4 sessions; 2 completed 2 sessions, and 1 completed 0 sessions. Thus, 12 of 16 participants (75.0%; binomial exact 95% CI: 47.6%, 92.7%) completed all assigned WBH sessions; 13 of 16 participants (81.3%; binomial exact 95% CI: 54.4%, 96.0%) completed at least 4 WBH sessions.

Secondary outcomes

Participants (n = 12) who completed baseline and final assessment visits completed 100% of administered self-report depression (BDI-II) assessments (of note, due to a technology error, one participant was administered 9 rather than 10 depression BDI-II assessments; they were not administered a single BDI-II assessment the week after their baseline assessment). Of the 4 participants who discontinued participation prior to the final assessment visit, 1 completed 8 BDI-II assessments, 1 completed 7 BDI-II assessments, 1 completed 6 BDI-II assessments, and 1 completed 2 BDI-II assessments. The n = 4 who did not complete the final assessment visit completed an average of 5.8 (SD = 2.6) BDI-II assessments. The entire enrolled sample (n = 16) completed an average of 8.9 (SD = 2.2) BDI-II assessments.

Among participants who completed the baseline and final assessment visits (n = 12), there was an average decrease of 15.8 points in the BDI-II [95%CI: −22.0, −9.7]. These BDI-II decreases were clinically meaningful [Citation33, Citation45] and statistically significant regardless of whether participants were offered 8 WBH sessions [M=–16.8, 95% CI: −27.2, −6.4] or 4 WBH sessions [M= −15.1, 95% CI: −25.4, −4.9; Appendix B]. These participants (n = 12) completed all administered BDI-II assessments (no missing data).

Additional outcomes

Participant characteristics

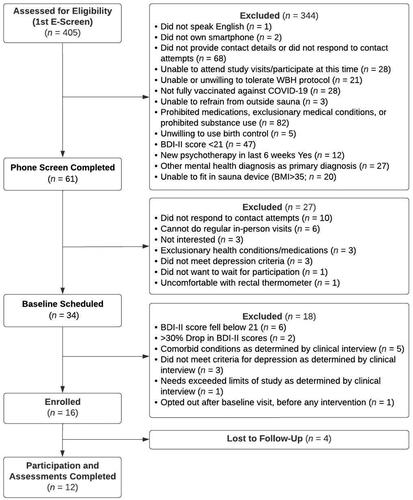

We enrolled 16 participants (). Participants were 62.5% (n = 10) white, 43.8% male, and were on average 41.9 years old (). Of the 16 enrolled participants, 12 participants completed participation through the final assessment visit, which was completed an average of 10.9 weeks (SD = 2.2 weeks) after the baseline assessment ().

Table 2. Participant characteristics.

Retention

Four participants did not complete participation. Of these, two participants discontinued participation citing difficulties with the time commitment: One participant withdrew at the beginning of their first CBT session and before beginning any WBH sessions, citing a lack of time to complete study procedures and insufficient participation fiscal compensation. A second participant discontinued participation after 7 CBT sessions and 2 WBH sessions (of 4 planned), having reported to the study therapist that the time commitment was no longer feasible (in particular, attending WBH sessions during the week) given their new employment. A third participant discontinued after completing 6 CBT sessions and 7 WBH sessions (of 8 planned), reporting that they no longer felt that they needed this treatment; of note, this participant had a significant pause (6 weeks) in their participation due to COVID-19 factors, which may have negatively impacted intervention engagement. The final BDI-II assessment we collected from this third participant showed a 12-point decrease from their baseline assessment, suggesting that they had made meaningful clinical improvements in depression [Citation33, Citation45]. A fourth participant discontinued participation after completing 6 CBT sessions and 2 WBH sessions (of 4 planned) because they wanted to begin a daily transcranial magnetic stimulation MDD treatment. Notably, between the baseline assessment and last obtained assessment, the changes in BDI-II scores for these four participants were −4, −12, −12, and −22; thus, all participants had reduced depression symptoms at the time of their discontinuation.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) clinician fidelity

Of the 16 enrolled participants, 15 participants completed at least one CBT session. The average total CTS-R score was 59.9 (SD = 6.39) indicating an average score on the border (60) of the proficient and expert categories of proficiency in delivering CBT per protocol (and well above the range of competent, which begins at an average score of 36).

Whole-body hyperthermia (WBH) protocol adherence

Of the 16 participants, 2 reported non-adherence to the WBH treatment protocol: 1 participant reported consuming alcohol within 24 h before 3 of their WBH sessions, and 1 participant reported consuming alcohol within 24 h before 1 WBH session and marijuana 24 h before 1 WBH session.

Adverse events (AEs)

No serious AEs occurred in the 79 WBH sessions administered. Participants experienced several mild adverse events that are expected in heat therapies (). The most common mild adverse event was lightheadedness, followed by headache, and nausea. Two participants stopped WBH sessions before they reached target temperature and before allotted time had elapsed; one participant stopped five WBH sessions and one stopped three early citing lightheadedness and jitteriness, and one participant stopped one WBH session due to a need to vomit, as they reported having overeaten prior to their WBH session. Of note, a few participants experienced frequent AEs; three participants experienced 8 or more AEs across all of their WBH sessions, whereas all other participants experienced 4 or fewer AEs across all of their WBH sessions.

Table 3. Adverse events (AEs).

Changes in mood early in treatment

Daily level changes in depression symptoms from pre-post the first WBH session

Among the 12 participants who completed a final assessment visit, the acute change in PROMIS Depression 8a T Scores (from 1-2 days before to 1-2 days after their first WBH session) was statistically significant and clinically meaningful [M Diff=–3.71, 95% CI (–6.96, −0.46), p = 0.029]; among all participants with available data (n = 15), this acute change was neither statistically significant nor clinically meaningful [M Diff=–1.81, 95% CI (–5.21, 1.58), p = 0.27].

Weekly level changes in depression symptoms from pre-post the first WBH session

Among all participants with available daily PROMIS Depression 8a data (n = 15), depression symptoms statistically significantly decreased from 1 week before to 1 week after their first WBH session, although the size of this decrease fell short of clinical meaningfulness [Citation36] [M Diff=–1.23, 95% CI (–2.35, −0.12), p = 0.032].

Change in the BDI-II from one week before to one week after the first WBH session

Among participants who completed a final assessment visit (n = 12), there was a statistically significant reduction in BDI-II scores from the assessment prior to the first WBH session to the assessment collected before the second WBH session, which was an average of 8.9 days (SD = 2.8 days) later [n = 12; M diff=–4.33, 95% CI (–7.27, −1.40), p = 0.0077]. We observed similar results among all participants with a BDI-II assessment before and after the first WBH session, which was an average of 8.6 days (SD = 2.7 days) later (n = 14; M diff=–4.00, 95% CI (–6.75, −1.25), p = 0.0077 (one participant was missing a BDI-II assessment between their first and second WBH sessions due to a technology failure, hence, including this person would have meant they had received two WBH sessions between assessments, we therefore excluded them).

Change in mood from pre-post the first WBH session

We observed improvements in overall mood from before to after the first WBH session as well as before to after all WBH sessions overall, both in terms of the BMIS single mood item and the total BMIS score (). Although we also observed improvements in the BMIS single mood item from before to after the first CBT session and before to after all CBT sessions overall, these improvements were smaller than those we observed from before to after the WBH sessions (). A standardized mean difference (SMD) for the single mood item from before to after the first WBH session was 2.22 (vs. 0.72 from before to after the first CBT session); the SMD for the total score from before to after the first WBH session was 1.46 (vs. 1.11 from before to after the first CBT session).

Table 4. Changes in self-report measures of mood and affect.

Overall treatment response

DSM-5 criteria for MDD (SCID-5-RV)

All participants (N = 16) met criteria for MDD at their baseline assessment. Only one participant out of 12 who attended the final assessment visit met criteria for MDD at the final assessment visit (this participant was offered and completed 4 WBH sessions). Thus, 11 of 12 participants (91.7%) completing the final assessment visit no longer met DSM-5 criteria for MDD (four participants, of whom one was offered 8 WBH sessions and of whom three were offered 4 WBH sessions, did not complete the final assessment visit).

Minimally clinically important reductions in BDI-II

When defining responders as those with pre-post intervention BDI-II score decreases that were ≥17.5%, which has been termed a minimum clinically meaningful difference [Citation33], from baseline to the final assessment visit, 10 of 12 participants (83.3%) who attended the final assessment visit were responders. Among all participants who completed at least one CBT session and at least one WBH session (n = 15) and using the last BDI-II collected from the 3 participants who did not complete the final assessment visit (LOCF), 12 of 15 participants (80.0%) were responders.

When defining responders as those with BDI-II score decreases that were ≥50%, from baseline to the final assessment visit, 7 of 12 participants (58.3%) who attended the final assessment visit were responders. Among all participants who completed at least one CBT session and at least one WBH session (n = 15), and using the last BDI-II collected from the 3 participants who did not complete the final assessment visit (LOCF), 9 of 15 participants (60.0%) were responders.

Weekly level changes in depression symptoms from the week before treatment to the week after final treatment

Among participants who completed a final assessment visit (n = 12), depression symptoms assessed by PROMIS Depression 8a statistically significantly decreased from the average score over 1 week at baseline to the average score over 1 week at post-treatment [M Diff=–8.08, 95% CI (–12.19, −3.98), p = 0.0012].

Changes in mood early in treatment as a predictor of overall treatment response

Among participants who completed a final assessment visit (n = 12), change in mood from pre-post the first WBH session predicted 36.2% of the pre-post-intervention change in BDI-II (final assessment–baseline assessment; rho=–0.60, p = 0.038). In contrast, change in mood from pre-post the first CBT session did not predict change in BDI-II (0.27%; rho = 0.02; p = 0.87).

Depression-related symptoms

We observed clinically meaningful [Citation36] and statistically significant improvement from baseline to final assessment visit in most subscales within the PROMIS29, including depression, anxiety, and sleep ().

Automatic thoughts and cognitive flexibility

Among participants who completed a final assessment visit (n = 12), we observed statistically significant improvements in automatic thinking. Although changes in cognitive flexibility suggested improvement, they were not statistically significant ().

Differences between participants offered 4 versus 8 WBH sessions

When analyzed separately, participants who completed the final visit and who were offered 8 WBH sessions (n = 6) and who were offered 4 WBH sessions (n = 10) showed the same direction of change and patterns of significance in study outcomes (Appendix B).

Discussion

The primary goal of this trial was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a novel, integrated mind-body intervention comprising WBH and CBT for the treatment of depression. A secondary goal was to evaluate preliminary efficacy of the integrated treatment. We found that the treatment was feasible and acceptable for most participants, as 13 of 16 participants completed at least 4 WBH sessions. We found that the time commitment was a meaningful factor for two of the four participants who discontinued participation. Participants who completed treatment completed all key depression assessments (BDI-II assessments and two clinical interviews) and achieved clinically meaningful and statistically significant reductions in depression symptoms. In nearly all (11 of 12) cases, participants who completed the treatment no longer met criteria for MDD at their post-intervention clinical interview. Negative automatic thinking and cognitive flexibility are primary targets of CBT, and although we observed reductions in negative automatic thinking, improvements in cognitive flexibility fell short of statistical significance. We also found that early treatment response, specifically improvements in mood from before to after the initial WBH session (but not before to after the initial CBT session), predicted longer-term treatment outcomes. Finally, we did not observe meaningful differences in outcomes across those who were offered 4 versus 8 WBH sessions.

These data add to a small but growing body of research suggesting that infrared WBH may be a feasible, acceptable, and efficacious body-based and non-pharmacologic approach for treating MDD [Citation14, Citation15, Citation18]. Prior trials have tested a single infrared WBH session and followed participants for as long as 6 weeks [Citation14, Citation18]; our trial expands upon these trials by ascertaining if participants would find completing multiple infrared WBH sessions feasible and acceptable. Our clinical trial also further extends this literature by integrating WBH with a first-line mind-based and non-pharmacologic manualized psychotherapy treatment (CBT). We hypothesize that this mind-body combination targets distinct mechanisms that may underpin MDD; specifically, CBT targets patterns of negative automatic thinking and cognitive distortions [Citation22, Citation44], whereas WBH targets thermoregulatory processes [Citation14, Citation16]. This integrated treatment may be of interest for individuals who are not able or interested in using antidepressant medications or in engagement with longer-term psychotherapy (beyond eight sessions).

This trial integrated two treatments that are now protocolized and manualized for future testing. The protocol uses components that can be widely disseminated in the future should future testing show that this protocol is efficacious in the treatment of MDD. We administered a WBH protocol using a commercially available WBH device and a standard continuous rectal thermometer. Additionally, this intervention included a manualized CBT protocol, and CBT sessions can be coded for fidelity using a validated adherence coding scale [Citation23, Citation24].

Completing this treatment may pose challenges for patients who are unable to attend WBH sessions during the week; WBH study visits lasted as long as 3-4 h including time spent preparing for, completing, and concluding, WBH sessions. Although 12 of 16 participants completed the intervention, 2 of the 4 participants who withdrew cited difficulties with the time commitment. One of these two participants never completed any study intervention visits, opting to withdraw at the start of their first CBT session, and another participant reported that completing further WBH sessions was not feasible given their new employment. Future research should take extra precautions during consenting processes to emphasize the time commitment needed to complete this integrated treatment. Although limited research suggests that the length of WBH session we used may be most clinically effective [Citation15], future research should consider whether shorter WBH sessions may be more feasible and acceptable while also efficacious. Completing 4 bi-weekly (every other week) sessions may; however, prove more feasible than other body-based treatments, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation, which is administered daily on weekdays for as long as six weeks [Citation46].

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, this was a single-arm trial that lacked a control condition because our primary research question was whether the integrated intervention was feasible and acceptable. Second, we made a meaningful change in the design midway through the trial because our focus was in preparing the integrated intervention for future efficacy testing. Specifically, we reduced the intervention from 8 weekly WBH sessions to 4 bi-weekly WBH sessions after 6 participants. We did not, however, observe statistically significant or clinically meaningful differences in outcomes across participants offered 8 versus 4 WBH sessions, which offers preliminary data suggesting that 4 sessions may be a more feasible and acceptable approach that still achieves clinical benefit.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study was the first trial to integrate WBH with CBT for the treatment of MDD. We found that the integrated mind-body intervention using a commercially available WBH device and a manualized CBT protocol was feasible and acceptable for most participants and demonstrated clinically meaningful reductions in depression symptoms among those who completed treatment. Although this rate of pre-post-intervention resolution of MDD (11 of 12 participants who attended the final assessment visit) is substantially higher than we might expect from CBT alone [Citation20, Citation25], the lack of a randomized comparison group precludes reliable conclusions about efficacy. Results we report here underline the importance of conducting future controlled efficacy trials to further evaluate this integrated treatment. Given the global rates of MDD and the dearth of efficacious treatments, this integrated treatment holds promise as a fully protocolized and manualized non-pharmacologic treatment option that should undergo efficacy testing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sean B. Fender for his assistance in developing the WBH protocol.

Disclosure statement

CLR serves as a consultant for Usona Institute, Novartis, Emory Healthcare and Biogen/Sage. CAL is Cofounder, Board Member, and Chief Scientific Officer of Mycobacteria Therapeutics Corporation, and is a member of the faculty of the Integrative Psychiatry Institute, Boulder, Colorado, the Institute for Brain Potential, Los Banos, California, USA, and Intelligent Health Ltd, Reading, UK. AEM has received financial renumeration from Oura Ring, Inc. for consulting. RPP is cofounder of FoundMyFitness, LLC, and frequently lectures on the science of sauna as a potentially healthful modality through podcasts, videos, and articles published on foundmyfitness.com. JCN serves as a consultant to Biohaven, Johnson and Johnson, Novartis, and Otsuka, and receives royalties from UpToDate.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings will be available at OSF (https://osf.io/), together with a data dictionary, upon publication.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Health statistics and information systems: depression; 2021.

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR* D report. AJP. 2006;163(11):1–13. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.11.1905.

- Li X, Frye MA, Shelton RC. Review of pharmacological treatment in mood disorders and future directions for drug development. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):77–101. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.198.

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2018;16(4):420–429. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.16407.

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28.

- Avery DH, Wildschiødtz G, Rafaelsen OJ. Nocturnal temperature in affective disorder. J Affect Disord. 1982;4(1):61–71. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(82)90020-9.

- Rausch JL, Johnson ME, Corley KM, et al. Depressed patients have higher body temperature: 5-HT transporter long promoter region effects. Neuropsychobiology. 2003;47(3):120–127. doi: 10.1159/000070579.

- Song X, Zhang Z, Zhang R, et al. Predictive markers of depression in hypertension. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(32):e11768. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011768.

- Raison CL, Hale MW, Williams LE, et al. Somatic influences on subjective well-being and affective disorders: the convergence of thermosensory and Central serotonergic systems. Front Psychol. 2015;5:1580. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01580.

- Avery DH, Shah SH, Eder DN, et al. Nocturnal sweating and temperature in depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100(4):295–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10864.x.

- Souetre E, Salvati E, Wehr TA, et al. Twenty-four-hour profiles of body temperature and plasma TSH in bipolar patients during depression and during remission and in normal control subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(9):1133–1137. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.9.1133.

- Duncan WC.Jr, Circadian rhythms and the pharmacology of affective illness. Pharmacol Ther. 1996;71(3):253–312. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00092-7.

- Szuba MP, Guze BH, Baxter LR. Electroconvulsive therapy increases circadian amplitude and lowers core body temperature in depressed subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42(12):1130–1137. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00046-2.

- Hanusch K-U, Janssen CH, Billheimer D, et al. Whole-body hyperthermia for the treatment of major depression: associations with thermoregulatory cooling. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(7):802–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12111395.

- Hanusch K-U, Janssen CW. The impact of whole-body hyperthermia interventions on mood and depression – are we ready for recommendations for clinical application? Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36(1):573–581. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2019.1612103.

- Lowry C, Flux M, Raison C. Whole-body heating: an emerging therapeutic approach to treatment of major depressive disorder. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2018;16(3):259–265. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20180009.

- Aaland M. Sweat: the illustrated history and description of the Finnish sauna, Russian bania, Islamic hammam, Japanese mushi-buro, Mexican temescal, and American Indian & Eskimo sweat lodge. Santa Barbara (CA): Capra Press; 1978.

- Janssen CW, Lowry CA, Mehl MR, et al. Whole-body hyperthermia for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(8):789–795. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1031.

- Nyer M, Hopkins LB, Farabaugh A, et al. Community-delivered heated Hatha yoga as a treatment for depressive symptoms: an uncontrolled pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(8):814–823. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.0365.

- Cuijpers P, Cristea IA, Karyotaki E, et al. How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta-analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(3):245–258. doi: 10.1002/wps.20346.

- Cully JA, Dawson DB, Hamer J, et al. A provider’s guide to brief cognitive behavioral therapy. Houston (TX): Department of Veterans Affairs South Central MIRECC; 2020. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/visn16/docs/therapists_guide_to_brief_cbtmanual.pdf

- Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy: basics and beyond. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2020.

- Kazantzis N, Clayton X, Cronin TJ, et al. The cognitive therapy scale and cognitive therapy scale-revised as measures of therapist competence in cognitive behavior therapy for depression: relations with short and long term outcome. Cogn Ther Res. 2018;42(4):385–397. doi: 10.1007/s10608-018-9919-4.

- Blackburn I-M, James IA, Milne DL, et al. The revised cognitive therapy scale (CTS-R): psychometric properties. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2001;29(4):431–446. doi: 10.1017/S1352465801004040.

- Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Weitz E, et al. The effects of psychotherapies for major depression in adults on remission, recovery and improvement: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014;159:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.026.

- Mason AE, Fisher SM, Chowdhary A, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a whole-body hyperthermia (WBH) protocol. Int J Hyperthermia. 2021;38(1):1529–1535. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2021.1991010.

- First M, Williams J, Karg R, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM 5-research version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, research version; SCID-5-RV). Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2015.

- Chambers CD. Risks of hyperthermia associated with hot tub or spa use by pregnant women. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006;76(8):569–573. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20303.

- Chandler GM, Iosifescu DV, Pollack MH, et al. Validation of the Massachusetts general hospital antidepressant treatment history questionnaire (ATRQ). CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(5):322–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00102.x.

- Qualtrics XM - Experience Management Software. Qualtrics; 2022. https://www.qualtrics.com/

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8(1):77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5.

- Hengartner MP, Plöderl M. Estimates of the minimal important difference to evaluate the clinical significance of antidepressants in the acute treatment of moderate-to-severe depression. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2022;27(2):69–73. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111600.

- Button KS, Kounali D, Thomas L, et al. Minimal clinically important difference on the Beck Depression Inventory - II according to the patient’s perspective. Psychol Med. 2015;45(15):3269–3279. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001270.

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011.

- Healthmeasures. net. https://www.healthmeasures.net/.

- Kroenke K, Stump TE, Chen CX, et al. Minimally important differences and severity thresholds are estimated for the PROMIS depression scales from three randomized clinical trials. J Affect Disord. 2020;266:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.101.

- Cella D, Gershon R, Lai J-S, et al. The future of outcomes measurement: item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Qual Life Res. 2007;16 Suppl 1(S1):133–141. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9204-6.

- Kendall PC, Howard BL, Hays RC. Self-referent speech and psychopathology: the balance of positive and negative thinking. Cogn Ther Res. 1989;13(6):583–598. doi: 10.1007/BF01176069.

- Beck AT. The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(8):969–977. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050721.

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York (NY): Penguin; 1979.

- Dennis JP, Vander Wal JS. The cognitive flexibility inventory: instrument development and estimates of reliability and validity. Cogn Ther Res. 2010;34(3):241–253. doi: 10.1007/s10608-009-9276-4.

- Mayer JD, Gaschke YN. The experience and meta-experience of mood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55(1):102–111. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.55.1.102.

- Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing—when and how? J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(4):343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00314-0.

- Persons JB, Burns DD. Mechanisms of action of cognitive therapy: the relative contributions of technical and interpersonal interventions. Cogn Ther Res. 1985;9(5):539–551. doi: 10.1007/BF01173007.

- Health NCC, For M. Depression: management of depression in primary and secondary care. Lond Natl Inst Clin Excell. 2004;24.

- O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;62(11):1208–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.018.

Appendix A.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion Criteria:

Age of at least 18 years old.

Current major depressive episode of at least 2 weeks duration as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID) and a Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) score ≥ 21 at screening

Able to understand the nature of the study and able to provide written informed consent prior to conduct of any study procedures

Must have smartphone onto which they can download an app from Apple App or Google Play stores.

Ability to lie supine (on back) for 2 hours (required for sauna sessions)

Must be fully vaccinated against COVID-19

Exclusion Criteria:

>30% reduction in BDI-II score between final two screens (conducted ∼1 week apart)

Suicide attempt in the past 12 months defined using the SAMHSA suicidality question during the clinician-administered interview or active suicidal ideation as indexed by a score of 3 on the BDI-II suicidality item during the clinician-administered interview

Any of the following medical conditions: cardiovascular disease (other than controlled hypertension), seizure disorder, history of cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or other serious neurological condition (e.g. Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or dementia), current neoplasia, any active enclosed infection (e.g. dental abscess, joint infection), hemophilia or other cause for excessive bleeding (e.g. platelet disorder), or other medical condition that in the opinion of investigators may increase the risk of WBH

Comorbid psychiatric conditions or history of comorbid psychiatric conditions that might better explain depressive symptoms, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, Bipolar Disorder I, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, Alcohol Dependence, or Drug Dependence

Known hypersensitivity to hyperthermia and/or infrared exposure

Inability to fit into the WBH device

Breast implants

Pregnancy, active lactation or intention to become pregnant during the study period

Use of any medication that might impact thermoregulatory capacity, including:

diuretics, barbiturates

beta-blockers

antipsychotic agents

anti-cholinergic agents or chronic use of antihistamines

aspirin (other than low-dose aspirin for prophylactic purposes)

medication prescribed for the treatment of depression (antidepressant medication [ADM]) including but not limited to: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], monoamine oxidase inhibitors [MAOIs], tricyclics [TCAs], and atypical antipsychotic and antidepressant medications (participants must have been free of these medications for at least 4 weeks)

antibiotics (past 14 days), pain medication (opioids) due to procedure, e.g., dental procedure (past 14 days), emergency contraception pill (past 14 days)

any other medication that in the judgment of the PI would increase risk of study participation or introduce excessive variance into physiological or behavioral responses to WBH

recent use (multiple consecutive doses) of: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), systemic corticosteroids, cytokine antagonists

Regular use of any nicotine products, including cigarettes, vapes, chewing tobacco, or other forms of nicotine (if use is not regular, must be willing to refrain for 24 hours before and 24 hours after sauna session)

Unwilling to refrain from using marijuana products and alcohol for the 24 hours before and 24 hours after sauna sessions

Unwilling to refrain from heavy exercise on the day of sauna sessions

Unwilling to refrain from engaging with sauna, hot yoga, cold plunges, cryotherapy, and hot tub/jacuzzi outside of study (prospective participant must not have engaged with any of these activities for 30 days prior to their baseline study visit).

Has begun new psychotherapy treatment in the prior 6 weeks

*Note: The study’s medical monitor reviewed all medications reported by prospective participants. If a prospective participant reported medications that the medical monitor determined to not have meaningful impacts on bodily thermoregulatory processes and to not interact with WBH, the participant was not ineligible to participate.

Appendix B.

Changes in self-report measures among participants who completed the final visit, by number of WBH sessions offered.