ABSTRACT

In Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union, housing estates are often associated with inhumane architecture and unwelcoming public space, an outcome that can be attributed to strict design requirements in a rigid centralized system. Due to the uniformity of residential housing produced during socialist times, both the design process and its master – the architect – are believed to have played only minor roles in shaping townscapes. This study, situated in the large housing estates of Tallinn, Estonia, challenges these assumptions using analyses of archival material (relating to planning procedures during state socialism) and articles in specialized magazines. The study also explains – through first-hand interviews with senior architects who were key players in building socialist cities – the relations between Soviet regulations and vital elements of the city-building process, including creativity, power, and artistry. Analysis of primary source materials highlights an oversimplification of socialist modernism, which suggests more nuanced explanations for town planning outcomes. Findings suggest that regulations issued in Moscow for Union of Soviet Socialist Republic-wide planning played a less important role than previously assumed in town planning outcomes in Estonia. International modernist city planning ideals, combined with local expertise, strongly influenced town planning practice in the Soviet ‘West’.

Introduction

State socialism provided unique opportunities to experiment with new models of city planning. Centrally planned systems – and government ownership of all land and industry – permitted a grand-scale approach to urbanization and a mechanism for promoting rational use of human and industrial assets, improving life quality, and reducing costs. Through central planning, state socialist governments sought to re-order society and plan new urban territory during rapid urbanization, industrialization, employment-driven migration, and military consolidation.Footnote1 Much power resided in central government decision-making. With land in state ownership, the development process occurred under central authority, and a powerful single-party system had great control over land development decisions to promote the expansion of industrial strength and military might.

Vast housing estates – residential complexes dominated by high-rise block apartment buildings – were established between the 1960s and the 1990s to respond to crushing demand for urban housing due to employment-based migration triggered by expansions of industry and military that were critical to the ideology of the Soviet regime. They were critical components of modern, planned cities for housing socialist lives in industrial-utopian centres.Footnote2 Architects charged with planning new housing estates had great power to shape cities, demonstrating that city planning was a centrepiece of central economic planning.

The peculiarities of town planning (and resulting urban form) during state socialism have intrigued scholars for decades. When the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was in operation, the spatial structures of socialist cities – and the social politics that supported the system – were of interest to both western and eastern researchers.Footnote3 A number of contemporary studies have retrospectively critiqued socialist urban systems, particularly policies leading to the formation of mikrorayons, or comprehensively planned residential districts composed of standardized buildings.Footnote4 While previous research has highlighted the role of central planning and socialist principles in shaping modernist housing estates that are prevalent throughout Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and the Former Soviet Union (FSU), this article, drawing upon on first-hand information gained from interviews with planners from the socialist period, reconsiders several dogmatic notions about urban planning under socialism. We argue that positioning local architects as mere executors of higher political commands controlling city planning oversimplifies the formation of modernist housing estates in socialist cities. Our findings suggest more powerful western influences on large housing estate design than previously assumed and demonstrate the existence of independent architectural thought in the Baltic republics.

The article is organized as follows. The following sections describe the socialist framework for city planning that produced the mikrorayon as a novel urban form; we also synthesize the contemporaneous urban planning system and the role of socialist architects. Next, our research strategy is presented, followed by a detailed empirical analysis of three residential districts in a capital city in the former Soviet space. We distil from the analysis key themes related to: contact that facilitated knowledge acquisition about international modernism; contemporary critical discourse about city planning in the Soviet Union, and the role of architects in the Soviet city-building process. Our concluding thoughts emphasize how, contrary to conventional wisdom, architects had more power than the Soviet system suggests and were able to embrace opportunities to create unique building environments.

Mikrorayon: centrepiece of socialist urban form

In Soviet times, city planning was part of the production process – a ‘construction job for the government’Footnote5 generally believed to lack artistry. Egalitarianism and a lack of differentiation across urban space were driving objectives; no residential area should be more appealing than any other because of style, size, or location.Footnote6 Equality, a key ideological feature of socialist residential planning, was vigorously expressed in Soviet housing estates and mikrorayons through pre-defined and universal maximum (walking) distances to schools, bus stops, shops, and parks. Everyone was, in theory, meant to have comparable access to comparable assets and amenities:

within the city there should be no particular areas that attract or repel people; they should all be of standard design with equal space (per person) and amenities so that it makes no difference to people whether they live in one neighbourhood or another. The socialist neighbourhood will be characterised by equality and classlessness.Footnote7

The architectural ensemblesFootnote8 composing mikrorayons and residential housing estates were meant to be socialist–modernist and, owing to influences from Le Corbusier,Footnote9 free from historical references.Footnote10 As a result, many projects denied their immediate context,Footnote11 instead relying on serial implementation of pre-determined standardized forms.

The first apartment houses built using pre-fabricated panel walls, established in the early 1960s, took advantage of industrial production to orchestrate residential building more cheaply. This was followed by improved standard designs, introduced in the Soviet Union in the mid-1970s and used widely by the 1980s.Footnote12 Each housing unit included ‘modern’ conveniences – kitchens, washrooms and toilets, central heating, large windows – that were available to only a limited degree in the pre-Second World War housing. As the design process matured and mechanisms within it advanced during subsequent iterations, the height of residential buildings increased and the size of individual dwelling units expanded.Footnote13

Considered to be a highlight of modern city planning, enormous housing estates included apartments (at high density, in standardized high-rise blocks) with modern conveniences in mixed-use settings containing schools, everyday services, day-care, and recreational and socialization opportunities. Usually, one housing estate consisted of several mikrorayons, which were designated by central authority according to housing requirements that were calculated proportional to the needs for workers in enterprises. Site selection for large housing estates was usually designated in general town plans prepared for up to 25-year horizons.

Within new residential districts, site planning was conducted at the district or mikrorayon level with detailed planning projects that were magnificent in size and comprehensive in scope,Footnote14 covering street networks, architectural elements, access and transport, and greenery, as well as infrastructural considerations including heating, water, and sewage. Strict norms dictated the living space that was allowable for each family, and housing units were allocated according to need (based on family size) with rent computed proportional to income (with large state subsidies).

The role of socialist architects in city planning

Important decisions about urban growth and housing policy occurred at high levels in the USSR, and local authorities were involved in mundane decisions, primarily in site selection for new housing districts that were prescribed by Soviet administrators.Footnote15 Local architects’ contributions to city planning occurred as follows:

… the role of Soviet urban planners was to translate the detailed instructions of a state developer into a finished design of either a complex of settlements, a particular city, or a part of a city. Since the national priority was production for collective needs, urban plans normally focused on servicing industrial enterprises. Social infrastructure, including housing, services and green spaces was allocated according to the standard norms of minimum individual needs.Footnote16

City planning in USSR republics – and especially the addition of vast residential housing estates – was firmly based on administrative norms and instructions issued by supervising authority and directed by the communist party. Trained architects undertook all city planning duties. General plans and detailed plans for mikrorayons were, as a rule, prepared by professional teams whose members possessed various backgrounds (engineers, traffic specialists, landscape architects, etc.). Such teams were always led by a chief architect.

Soviet density norms became instruments of town planning and pre-defined access to workplaces, services, and recreational facilitiesFootnote17 and the distribution of funds for construction. Standard high-rise apartment block designs developed in Moscow were adapted locallyFootnote18 in state design institutes (interview with J. Lass, 2016). Through site design in particular, architects created an ensemble – composed of residential buildings, service structures, pathways and roads, and open space – that form the long-lasting effect of mikrorayons on urbanization. Local governments were only partly in charge of the location and site design of housing estates (the level of control differed depending on the city or the sister republic) (interview with J. Lass, 2016). Such weak contributions to city planning have often been described in scholarly literature as follows: ‘the majority of the housing units were prefabricated apartment blocks, and the architect’s role was reduced to site planning for a limited number of housing types’.Footnote19 Given the large number of inarguable directives to be followed in city planning under socialism, it was suggested that ‘the discipline of urban planning has abolished itself in favor of fulfilling guidelines’.Footnote20 It is likewise argued that, throughout the Soviet Union, ‘since the building forms of the standard designs were pre-determined, this meant that the urban design concept was greatly diminished to the extent of fulfilling guidelines’.Footnote21

The actual power resting within the hands of local architects is consequently debatable, since the state suggested the location for residential space, dictated its volume, and furnished land and financing.Footnote22 This notion has been periodically captured in scholarly literature:

architects, as employees in mammoth state design offices, had no say in the actual design and were reduced to draftspeople whose role was to draw site plans of the predesigned blocks of slabs and point towers to house a maximum number of residents picked from long waiting lists and crowded into a cookie-cutter housing estate.Footnote23

Second- and third-generation standardized apartment towers were designed to be sectional and interchangeable and could be assembled in various forms but always in large quantities;Footnote24 the requirements for standardization and prescribed repetition itself implies modest emphasis on artistry and individuality. However, with a fast-paced and vast expansion of housing supplies in cities of CEE and FSU, the architects who planned modernist housing estates had great power to shape city form, and their effects have been long lasting, since few residential districts have been demolished or significantly changed and most are fully occupied.

Research strategy

We use multiple methods to illustrate the making of socialist cities and explain the relations between strict Soviet regulations and creativity, powers and artistry. Our aim is to address an oversimplification of socialist modernism and search for more nuanced explanations for town planning outcomes that differ from what adherence to strict Soviet guidelines would produce. We explore whether local architects possessed power to design and shape vast urban territories and sought opportunities, regardless of the regulations and standards, to introduce originality (we refer to local architects as trained professionals working in State Design Institutes, city governments, and state institutions of republics of the USSR. Our aim is to differentiate local architects from the central architectural system in Moscow in which designs were produced for generic buildings and housing that could be constructed in any of the 14 republics.). We also gauge the degree of creativity in the design of housing estates and analyse the extent to which local architects could propose original solutions and unique designs. Lastly, we analyse whether influences from international modernism played a role in the design of Soviet large housing estates.

Within the body of research about Soviet-era urbanization, however, few studies return to original research material. Therefore, to explore the role of architects in practice, we turn to primary sources from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s to gather key decision-making information about the formation of residential districts in Tallinn, Estonia. We use official planning documents and, importantly, semi-structured interviews with critical informants. Personal interviews carried out in Tallinn and Tartu with senior architects (D. Bruns, Tallinn Chief Architect, 1960–1980; I. Raud, Eesti Projekt, 1969–1989 and Tallinn Chief Architect 1989–1991; O. Zhemchugov, Eesti Projekt, 1970–1977; J. Lass, Estonian State Building Committee, 1982–1990; R. Kivi, Eesti Projekt, 1969–1972 and Tartu Chief Architect 1972–1991; P. Männiksaar, Architect, Tartu District Executive Committee, 1981–1993), now at the end of their professional careers, give us access to their observations which seldom appear in written form because of censorship during Soviet times. Because of the respectable age of the architects who were active during the socialist period, it is vital to include their knowledge in studying the nuances of socialist planning practice. Primary source interviews and review of archival documents – plans and planning documents, including original protocols and memos and contemporaneous newspaper and magazine articles – allows us to assemble a meaningful picture of planning practice related to large socialist housing estates. We also review various materials published in Estonian Socialist Republic newspapers and weekly magazines.

An ensemble of mid-twentieth century of housing estates in Tallinn, Estonia

The socialist industrialization process was accompanied by fast urbanization throughout the USSR and particularly in communism’s western periphery in the Baltic states. Due to various factors shaping socialist urbanization,Footnote25 cities in the Baltic States are uniquely preserved. Apart from certain scholarship about Lithuania,Footnote26 a lack of reliable written material exists about state socialist residential planning theory as implemented in planned developments in the Baltic States.

As a site for our empirical inquiry, we select Estonia, the smallest of the three the Baltic States, where there is comparatively less literature on residential housing formation than in other parts of Europe.Footnote27 During the Soviet occupation, several hundred thousand Russian-speakers emigrated to or were settled in Estonia, and all Estonian cities experienced population growth between 1944 and 1991.Footnote28 In the 1950s and subsequent decades, there was strong demand for new housing in Estonia, especially in the capital city Tallinn, as Estonians moved from the countryside to townsFootnote29 and Russian-speaking immigrants arrived to support various enterprises of the Soviet Union. During Soviet times, approximately 76% of housing units in Tallinn were state-subsidized rental units (a higher share than elsewhere in CEE) and by the end of Soviet occupation, about two-thirds of the population lived in large pre-fabricated housing estates.Footnote30 Each city in Estonia had a master plan, which reserved space for future detailed site planning (interview with R. Kivi, 2013; P. Männiksaar, 2013).Footnote31

Today, housing estates in Tallinn offer bold visual symbols of the socialist past. Pre-fabricated panel buildings do not suffer from a bad reputation and have not experienced ghettoizationFootnote32 predicted following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.Footnote33 However, official policy within the housing sector sometimes reinforced social separation and exclusion. Housing in mikrorayons is often unpopular, and many families are driven by a desire to escape the drab environments of Soviet-era housing estates and relocate when possible to new or renovated upscale dwellings or detached homes in the growing suburbs.Footnote34

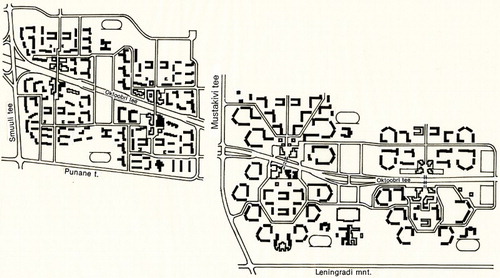

In the capital city of Estonia, Tallinn, three large mikrorayon-based residential districts – Mustamäe, Väike-Õismäe, and Lasnamäe – were constructed successively and at comparable distances from the city centre (see and ). The districts depict an evolution of town planning ideology during the Soviet decades and reflect a maturation of the mikrorayon concept and a requirement for larger per person living space improved design standards experienced throughout the Soviet Union.Footnote35

Table 1. Characteristics of large housing estates in Tallinn, Estonia.

In the following passages, we provide a detailed analysis of the three Tallinn housing estates – including their conception, design, and implementation – which we use to explore the role of architects in city planning. Subsequently, an overview of the criticism and debates about the new housing estates in Estonia is given. Based on the findings of the analysis of the establishment of large housing estates in Tallinn we discuss the inspirations and role of Soviet architects.

Mustamäe: a cautious test of socialist residential planning principles

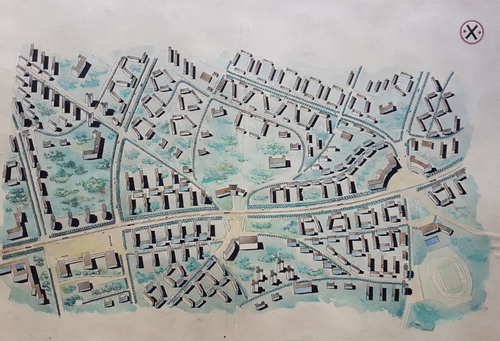

To liquidate the housing shortage in an optimistic period of 10–12 years,Footnote36 the communist party launched an ambitious housing construction programme in the USSR in 1957. Following directives from Moscow, site selection for the first large housing estate in Tallinn was immediately initiated, since the Tallinn General Plan of 1946 did not foresee the need for a massive new residential district. The Estonian Soviet Republic Council of Ministers issued the initial task for planning Mustamäe;Footnote37 an official planning process was launched in 1958 with an architectural competition, organized by the Executive Committee of Tallinn City, the State Architectural Board, and the Architects Union, in which 11 prospective architectural teams envisaged the structure, layout, and composition of the new residential district. Archived entries of the competition demonstrate mostly timid attempts at modernist city-building, with some architects displaying a lingering enthusiasm for Stalinist neo-classicism (see ).

Figure 2. Mustamäe architectural competition entry by Group X. Original drawing, 1958. Source: Museum of Estonian Architecture, used with permission.

The winning design by T. Kallas, M. Port, and V. Tippel was approved by the State Council of Ministers as a guiding conceptual plan for Mustamäe.Footnote38 In 1959, the plan was elaborated in a detailed planning project in which key planning principles – mikrorayon composed of large residential building blocks and schools, kindergartens, shops within walking distance – were for the first time in Estonia expansively applied (see ). Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, additional detailed planning projects were compiled to provide additional residential space in Mustamäe for Tallinn’s rapidly increasing population. Reports about the gradual construction of Mustamäe were continuously published in local newspapers and Estonia’s weekly cultural magazines like Sirp ja Vasar.

The planFootnote39 offers the first attempt in Estonia at free-form planning, considered novel at the time, in which large residential buildings are distributed freely and do not follow traditional street rights-of-way, producing more sunlight and open space between buildings. A number of features in the planning concept can be identified as characteristic of Finnish and Swedish modernist residential planning, where building blocks are harmoniously attuned with surrounding landscapes. Foreign influences in city planning can be attributed to the Khrushchev thaw,Footnote40 which made possible organized study trips for Baltic professionals to capitalist countries and limited distribution of international city planning and architectural literature. More than half of the members of the Estonian Architects’ Union visited Finland during the1960s, following an inaugural trip in 1957,Footnote41 coinciding with the formation of ideas about Mustamäe. Architects who had the chance to visit capitalist countries openly popularized western ideas upon their return by writing articles and columns in newspapers.

Adhering to a density norm of 9.5 m2 per inhabitant, the total residential space in Mustamäe was 538,000 m2, embodied in 9 mikrorayons. A majority of buildings (88%) were five storeys high and a small share (4%) were high-rises. Within every mikrorayon, between four and six elementary schools and one high school (or gymnasium) were planned; in addition, two cinemas, a library, hospital, four canteens, a restaurant, and four saunas were required. Shops and service centres (hairdressers, laundry, etc.) within so-called ABC centres (the name ABC standing for Arbete-Bostad-Centrum/Labour-Housing-Centrum was originally used in Swedish post-war satellite towns like VällingbyFootnote42) were evenly distributed within a radius of 500 m of residences. Greenery was preserved in a surrounding forest park, and each mikrorayon included sports facilities and playgrounds. A network of pedestrian paths connecting major destinations was carefully planned. Public transport played an important role; in addition to trolleybuses and buses, a tram was planned, and the location of stops was integrated with the pedestrian network. Garages as well as shops were designed in the proximity of major thoroughfares to avoid heavy traffic in the mikrorayon interior. A commercial and community centre, with various attractions (including dance halls, fashion studios, and sports centres) were planned as an organizing focus in the southern part of the district at the intersection of major radial thoroughfares. The plan stresses unique designs – avoiding standard Soviet projects – for important community assets like a cultural centre, department store, market hall, and hotel.

The construction period of Mustamäe lasted from 1962 to 1973. Major shortcomings in the operation of the district appeared when certain features were not built, including a centrally located business and community centre and several 16- to 22-storey tower blocks. A lack of recreational facilities, greenery development, and landscaping was evident immediately after construction.Footnote43

Väike-Õismäe: aerial architecture in a 1970s makrorayon

Tallinn City officials requested a detailed planning project for Väike-Õismäe from the state-owned planning and building institute Eesti Projekt in 1967. A detailed planning project for Väike-Õismäe was completed in 1968, overseen by architects M. Port and M. Meelak. A redevelopment enhancement plan was subsequently issued in 1974, adding a library, church, additional supermarkets, service centres, and beach pavilions (but none were actually built).

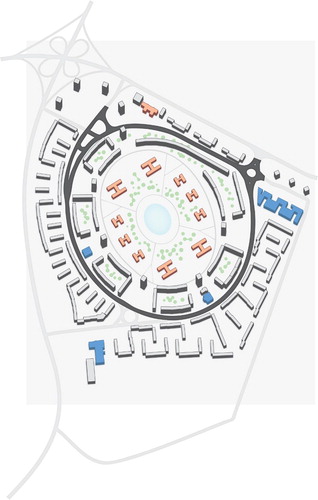

According to Soviet building regulations, the area should have originally been divided into three or four mikrorayons. However, during the detailed planning project, several alternative solutions were proposed (see ) which disregarded the central principles of mikrorayon formation and abolished the strict population normative. In the end, the architectural team courageously devised a novel macrorayon approach instead:

The makrorayon concept evolved quite unexpectedly when we tried to avoid the usual shortcomings of a traditional mikrorayon-based approach. There were four different solutions at work simultaneously. At first we were charmed by the aesthetic appeal of a single makrorayon, which was soon supported by its superiour technical specifications, functional details, and finally economic rationale. The main logic is quite simple: the street is fringed with buildings on both sides, radial avenues are unneeded, the traffic operation scheme is more simple, and the required street length is halved. To avoid monotony, the buildings are grouped in various combinations; 9-story buildings are interspersed with ‘freely placed’ 16–storey highrises.Footnote44

Figure 4. Original drawings for Väike-Õismäe detailed planning project, 1968. These process drawings represent alternative transportation network schemes; option 4, lower left-hand image, which configures the district as a single macrorayon, was the selected option. Source: Mart Port, Linnade Planeerimisest, permission not required.

During the planning process, a number of heated arguments took place between the chief architects – who fervently defended their novel ideas – and the city government and State Building Committee.Footnote45 Original documents and interview with D. Bruns conducted in 2013 demonstrate that although the makrorayon-approach did not adhere to official standards, it was supported, due to its creativity, by the chief architect of Tallinn and leading architects from the State Building Committee.

Compared to Mustamäe, the concept of Väike-Õismäe suggests a bold vision of imaginative architects inspired by pure modernist ideals.Footnote46 A fellow architect from Eesti Projekt describes the chief architect, Mart Port as a ‘shaker of ideas on paper and in words who did not let the others dispute his thoughts’.Footnote47

The district was planned as a makrorayon with a compositional focus on a broad encircling street, which was, characteristic to socialist–modernist urban form, impressive when viewed from above (see ).Footnote48 The outer parts of the oval contained mostly 5-storey buildings and the inner part mostly 9-story buildings (with occasional accenting with 16-storey high-rises) (see ).Footnote49 The circular layout is punctuated by an artificial lake at its core. Schools and child care centres are situated symmetrically around the centre. Due to natural circumstances (location on a limestone plateau), green space is restricted in size. According to the plan, the total residential space is 357,000 m2 for 37,750 occupants [adhering to a density norm of 9.5 m2 per resident (initially) and 12 m2 (after full implementation)]. Car parking spaces were planned for 5050 vehicles (norm of 170 cars per 1000 people). Following the normatives, 75 groceries and 12 shops for other goods were planned, as well as 3 canteens, 30 beauty salons, and community centres. Only 25% of these planned services were ultimately built.

Figure 5. Väike-Õismäe concept plan, 1968. Source: Drawing by S. Samuel (2016) based on original plans.

Figure 6. (a) A curving road in Väike-Õismäe, 1970s, Tallinn, Estonia. Photo by Johannes Külmet. Source: Museum of Estonian Architecture, used with permission. (b) A curving road in Väike-Õismäe, 2017, Tallinn, Estonia. Photo by Pille Metspalu.

Implementation of the Väike-Õismäe plan was scheduled to begin in 1972, immediately after construction of Mustamäe was complete. Unexpectedly, preparatory works took longer, and Mustamäe was instead spontaneously densified with new apartment buildings to avoid wasting ready-made building panels.Footnote50 Construction of the Väike-Õismäe macrorayon thus began one year later. Despite the fact that in Väike-Õismäe, USSR building regulations were creatively interpreted – for example, a single makrorayon instead of three mikrorayons, pedestrian crossings not separated from vehicles, etc. – the architectural team was awarded the Prize of Architecture of the USSR Council of Ministers in 1976.Footnote51 Some parts of the original plan were never implemented (such as large communal car parks between dwelling groups). Deficits in shops and services were severe: only three grocery shops were built, which resulted in constant queues, and only two of three planned community centres were constructed.

Lasnamäe: soviet megalomania, built to only half completion

The decision to create another new residential district to accommodate Tallinn’s growing population was made in 1968 by the Estonian Soviet Republic Council of Ministers. An all-union design competition for Lasnamäe, an enormous residential area, took place in 1969.Footnote52 The winning design (one of four submitted) produced by M. Port, M. Meelak, O. Zhemchugov, H. Karu, and R. Võrno, became the basis for the detailed planning project prepared in 1970 by the State Planning Institute Eesti Projekt (see ). M. Port, the chief architect, notes that the underlying idea of the final concept differs from earlier versions, although certain initial concepts were retained.Footnote53 In 1979, an updated general plan was issued to increase residential densities and provide better connections to neighbouring industrial zones.

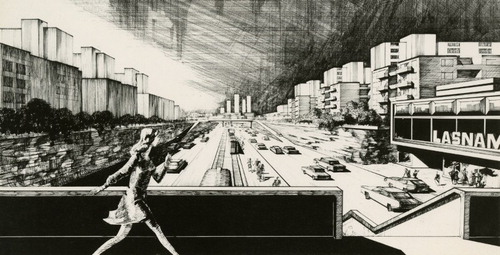

The guidelines issued by Tallinn City officials and prepared by the city architect’s office in 1970 established additional principles for detailed planning: the general structure should be based on makrorayons (25,000–30,000 inhabitants) with administrative and business centres; residential buildings arrangements should form inner courtyards for wind protection; expressive exterior ‘gateways’ should be composed; buildings of citywide importance should be included; and a pedestrian esplanade should top the limestone cliff (see ).Footnote54 The backbone of the detailed plan included two key east–west thoroughfares, one of them sunken (7 m deep), making possible fly-over bridges and permitting higher traffic speeds below while enhancing safety by removing vehicular traffic from pedestrian space.Footnote55 Pedestrian precincts were planned as landscaped boulevards planted with trees, running parallel to the motorways and crossing the traffic lanes via footbridges near community centres and parking lots (see ). All community centres adjoin pedestrian streets. In addition to five large sports halls, a cultural-memorial centre was planned on the edge of the limestone cliff. Housing is concentrated around the centres within a radius of 500 m. Each mikrorayon has a population of 12,000–16,000 inhabitants. The large-panel houses have mostly 5, 9, or 16 storeys. Two and three-storey rowhouses and 22- to 24-storey towers are included.Footnote56 The total planned residential area exceeded 3.9 million m2 (adhering to a density norm of 22.5 m2 per capita).

Figure 8. The plan for a housing estate at Lasnamäe (Tallinn, Estonia). Centres on four mikrorayons. Source: Museum of Estonian Architecture, used with permission.

Figure 9. A sketch of a pedestrian overpass providing access to the commercial centre of Lasnamäe, Tallinn. Source: Museum of Estonian Architecture, used with permission.

In our interviews, architects actively participating in designing Lasnamäe – O. Zhemchugov (interviewed in 2013) and I. Raud (interviewed in 2016) – pointed out parallels between Estonian housing estates and Finnish modernist residential districts (such as Tapiola and Pihlajamäki), consistent with observed similarities between socialist housing estates in the Baltic States (especially in Lithuania) and Finnish modernism.Footnote57 However, Scandinavian modernism and Finnish and Swedish orientation are not easily traceable in the Lasnamäe planning scheme. The cosiness characteristic of Scandinavian new towns that, according to one expert (interview with O. Zhemchugov, 2013), should have been expressed in Lasnamäe (through high-rise building blocks arranged to form inner courtyards) was lost due to the enormous scale of the housing estate. Poor growing conditions for trees (due to the location on the limestone cliff) did not help achieve the impression of apartment towers ‘melting’ into nature, which was to some extent achieved in Mustamäe.

One-third of the planned apartment houses in Lasnamäe (microrayons IX–XII) were not constructed; the spatial structure of the largest housing estate in Tallinn is functionally incomplete because the commercial centre of the district was never built (nor was the cultural-memorial centre). As usual, there were shortcomings in providing recreational facilities and shops, and greenery and parks are almost non-existent. The transport facilities essential for commuting are remarkably inadequate, as the high-speed light-rail originally planned in a sunken motorway was not built.

Contemporaneous perspectives of housing estates

A modernist-inspired socialist city planning strategy, for which an all-embracing goal was to create comprehensive urban space for a socialist populace, was imposed by the party leaders of the USSR. However, people were critical of new large housing estates as soon as the first buildings were erected. Debates occurred in professional circles and in public media, contrary to common belief that strict socialist censorship stifled meaningful discussion. First-hand accounts – acquired through interviews and memoirs of chief architects – demonstrate that the inspiration for critical views was often drawn from international architectural magazines available in limited numbers in the library of the Estonian Academy of Sciences.

Debates in the media were usually initiated by architects, who enjoyed great respect from both the public and officials, since they were highly trained and indispensable specialists. This attitude was especially evident in Estonia, a small nation proud of its architectural traditions developed during the first independence period in the early twentieth century.

The housing estates of Tallinn received varied reception from the public. In the 1960s and 1970s, coinciding with the construction of Mustamäe, critical viewpoints were expressed mainly by professionals, architects, and engineers. M. Port, a chief architect of the concept plan for Mustamäe (who was not involved in detailed planning projects), criticized the monotonous housing and sparse and confusing physical layout of the district. He notes that although each new mikrorayons in Tallinn displays visible advancements in urban planning techniques, the success of the layout of Mustamäe district is questionable.Footnote58 He was not directly involved in Mustamäe detailed planning projects, and he subsequently proposed an alternative spatial plan (see ) with fewer centres and a more efficient street network. Architect L. LapinFootnote59 vigorously denounced open-style planning method which placed people, buildings, and the environment in elementary technical schemes.

Figure 10. Alternative concept plan for Mustamäe by M. Port. Source: Mart Port, Linnade Planeerimisest, permission not required.

Criticism intensified by the late 1970s, when citizens bravely published their opinions in popular media. Although praised as a unified planning concept, Väike-Õismäe was denounced in numerous newspaper articles in which citizens lamented its incomplete construction and low quality living environments (that had looked promising on paper). For example, a citizen of Väike-Õismäe expresses his disappointment in the lack of recreational and cultural facilities and argues that otherwise efficiently designed urban space does not support ‘individual cultural and intellectual enrichment’ and does not ‘inspire social activity’,Footnote60 which should be the aim of comprehensive socialist planning; he further declares that providing an inadequate number of cultural facilities has an effect of confining people to their apartments and encouraging a petit bourgeois Footnote61 mentality. Comparing Väike-Õismäe with Mustamäe, SootnaFootnote62 acknowledges an improvement in standard building design but criticizes the mass of dense gray housing as depressing and monotonous.

Similarly, architect J. Kruusimägi denounces Väike-Õismäe and Mustamäe as ‘villages’ because of a lack of communal services, business, and recreational facilities.Footnote63 Contrary to the socialist spirit of collectivity, Kruusimägi suggests personal initiatives for improving the urban environment: ‘citizens are those who actually design the city, not one or two architects’.Footnote64 Well-known novelist L. Tungal asks rhetorically where children in Väike-Õismäe and Lasnamäe should play hide and seek amid an absence of trees and playgrounds.Footnote65 Economist E. Roose succinctly labels Soviet mikrorayons as aerial architecture – geometric shapes impressive from above but unsatisfactory for on-the-ground living.Footnote66 He suggests, among other things, that public involvement in early stages of planning processes – unheard of during Soviet times – could lead to improvements.Footnote67

The 1980s ushered in a new era – known as Gorbachev’s перестройка (perestroika) – of reformation within the Communist Party and society as a whole. Outspoken criticism towards the socialist system (as well as cities produced under socialism) slowly became part of everyday communication. This reformation period coincided with the end of the construction of Lasnamäe, which was by then roundly criticized. For Estonians, Lasnamäe transformed into a symbol of unwelcome Soviet occupation, with a song entitled ‘Stop Lasnamäe’ used as an unofficial national anthem during the Singing Revolution which led to Estonia’s 1991 re-independence.

Criticism of Lasnamäe was openly expressed by even those responsible for the district’s general plan. For example, architect M. Port has acknowledged challenges during the planning process: ‘the designing of the housing estate of Lasnamäe caused a lot of problems and a lively discussion among architects and townsfolk’.Footnote68 Public criticism concentrated on the vast scale of the district and grandiose modernism of infrastructure, especially the sunken thoroughfare creating a 100 m-wide divide between buildings. Architects expressed grave concerns about budget cuts demanded by the pre-fabricated panel industry to achieve building efficiency, resulting in a grey and monotonous appearance (interview with I. Raud, 2016). Due to cuts in construction budgets, a number of important details like artificial ponds, green corridors, and even carparks were never built (interviews with D. Bruns, 2013; O. Zhemchugov, 2013; I. Raud, 2016). A synthesis of discussions in the State Architects Union, published in Sirp ja Vasar in 1980, notes that it is impossible to hide the functional and architectural drabness of the mammoth-sized Lasnamäe despite the district’s town planning innovation. Members of the Architects Union muse that city planning and design as a discipline had become a storage yard for a single pre-cast panel plant.Footnote69

Challenges and opportunities in large housing estates in Soviet Estonia

Three key themes emerge when we synthesize the findings of our detailed discussion of Tallinn’s three large socialist housing estates. First, we demonstrate how international modernist ideals inspired local architects – to a greater extent than previously recognized – and influenced the development of housing estates in Soviet Estonia. The second theme suggests a greater degree of open and candid discussion (than previously identified in scholarly literature) about Soviet-era town planning and especially housing estates, including opinions (written by the general public) and expert pieces (written by architects for broad consumption). Third, we explore the powerful role in Soviet Estonia – which perhaps departed from the norm in USSR republics – of local architects in town planning practice as revealed by first-hand accounts.

International knowledge inspires architects of large housing estates

Estonia’s geographic position on the western periphery of communism made possible the preservation of close relations with neighbouring capitalist countries. We find that Finnish and Swedish influences are consequently evident in city planning and architecture of the day in Estonia (references to Tapiola, Finland in interview with D. Bruns, 2013; I. Raud, 2016) and that international modernist ideas from the western world played an important role, too, in the design of large housing estates (interview with D. Bruns, 2013; O. Zhemzhugov, 2013). An adherence to modernist ideals can be detected in the ‘clean sweep’ urban development method – entailing the complete demolition of existing semi-urban space in order to build something new and boldly different – heretofore untested in Estonia.Footnote70

Our findings suggest that the city planning system in the Soviet Union was not as controlled as previously assumed. The 1950s Kruschchev thaw – often referred to in hindsight as a ‘brilliant failure’ – transformed certain aspects of the Soviet system (but not the system itselfFootnote71) and was highly significant for city planning. Liberalization of state and foreign politics in the USSR influenced all aspects of life, including cultural landscapes.Footnote72 In the Baltic countries (and other USSR republics, although due to proximity and similarities in language, Estonians were perhaps more likely to participate), official study trips to Finland and Sweden were the manifestation of fostering international connections (and for Estonians, perfectly timed with concept development for Mustamäe). The trips became more frequent when, in 1965, direct ferry connection between Tallinn and Helsinki was restored.Footnote73 Upon return from the study trips, Estonian architects published articles about their experiences and impressions (in both public media and in professional outlets) in surprisingly candid ways, frequently debating the possibilities for urban planning practice and critiquing the planning of large residential districts. During the Khrushchev period, social contacts with war-emigrant Estonians (mostly in Sweden and Germany) were enabled, permitting information from abroad to be easily delivered through family connections. An official slogan of the socialist system – ‘learning from the mistakes of capitalist countries’ – was given special meaning in the way professional architectural knowledge was openly developed from foreign books and magazines.Footnote74 While the atmosphere of censorship was strict in the USSR, inhabitants of the northern part of Estonia were able to receive Finnish television signals, due to physical proximity, readily granting them exposure to visual depictions of modern cities and residential spaces across the Baltic Sea. For these reasons, we argue that Estonia is distinctive among the sister republics for its outward connections and influence and offers an intriguing array of inter-related modernist residential planning approaches.

Orientation towards Estonia’s northern neighbours was a conceptual tendency in Estonian architecture and city planning that usurped the standard design models of the USSR.Footnote75 Compared to architectural design of individual buildings, the influence of Finnish and Swedish town planning innovation on site planning for large housing estates is more difficult to trace. The vast scale of socialist housing estates in Soviet Estonia amplified the drabness of the districts and at the same time diminished the comforting features of Scandinavian modernism, like natural terrain emphasis and use of existing trees to create ‘tower in the forest’ settings for new housing blocks.

However, parallels between the layout of housing estates in Estonia (from the Soviet years) and contemporaneous Nordic city planning can be easily detected from our analysis of original planning documents and statements made by chief architects of the plans (interviews with I. Bruns, 2013; I. Raud, 2016; O. Zhemchugov, 2013).Footnote76 This was unique in the USSR, although it was matched to a certain degree in Latvia (in Āgenskalna priedes in Riga)Footnote77 and Lithuania (in Lazdynai in Vlinius)Footnote78 and to some extent, in Russia. Both Estonian and Lithuanian housing districts received awards from all-Union architectural and planning competitionsFootnote79 and Estonia and Lithuania were the only republics that regularly fulfilled new housing construction quotas required by Soviet authorities in Moscow.Footnote80

The design of Lithuania’s Lazdynai, which, like the housing estates in Estonia, pushed the boundaries of Soviet design – and, in some senses, composed in opposition to a standard Soviet mass housing scheme – was later heralded by the communist party for its socialist design excellence.Footnote81

Local newspapers publish critical discussions about mikrorayons

Not surprisingly, the role of city planning as a pillar of the Soviet system was frequently discussed in local media. Various newspaper articles, especially editorials declaring progress in creating new and better cityscapes (see ), might at first appear to be typical socialist propaganda. However, closer inspection suggests that the authors often reflected sincere belief in modernist ideals and an aim to solve social problems through comprehensive city planning. What we find remarkable in published opinion articles and travelogues is an apparent neutrality of the discussion, with a lack of customary criticism of the West and absence of exaltation of the Soviet sphere of influence. For example, reflections of architects’ study trips to western countries in local newspapers and magazines were often quite positive, providing straightforward celebrations of modernist city planning with minimum socialist rhetoric. D. Bruns, chief architect of Tallinn, describing Tapiola, Finland in Arhitektuur (an Estonian architectural quarterly) as ‘one of the most successful and interesting example of Scandinavian urban developments’ and ‘vividly engrained in the memory’,Footnote82 provides a detailed overview of the projects’ details. Local cultural magazines, such as Estonia’s Ehituskunst and Sirp ja Vasar, functioned as forums for lively theoretical and ideological debates, frequently expanding upon foreign experiences with contemporary architecture and famous contemporaneous architects. International transfer of knowledge is also evident in the agendas of Architects’ Union activities; for example, lectures about outstanding French and American modernist architects were often advertised in local media.

Architects in Estonia maintain a consistently strong role in town planning practice

Since architectural education began in Estonia in the 1920s, local professional architects had gained several decades of experience prior to the socialist era. Estonia was one of the few republics in the FSU that preserved an independent site-planning design capability in its state planning and design apparatus (Eesti Projekt, EKE Projekt, Tööstusprojekt, Kommunaalprojekt), a practice that can be traced to a mature architectural tradition dating from the early twentieth century (interview with J. Lass, 2016). Professional self-awareness combined with institutional powers granted by the new regime encouraged Estonian architects to take an active role in city planning under state socialism. In other republics of the Soviet Union such as Belarus and Kazakhstan (interview with J. Lass, 2016), architectural and city planning were designed and implemented from central headquarters in Leningrad or Moscow (using only standard building and district designs), with virtually no involvement with local or national experts.Footnote83 Consequently, architects in Estonia maintained a considerable voice in shaping cityscapes. City planning practice in Estonia was thus not based solely on reproduction of centrally formulated urban design models or economically efficient engineering but was formulated locally, under the leadership of skilled Estonian architects. In municipal governance, an architectural department and architectural advisory board were important bodies, largely composed of architects, and architectural commissions reviewed plans and projects issued by state planning and design institutes.

A strong tradition of architectural competitions in Estonia, originating in the 1930s, continued throughout the Soviet occupation, generating unique designs for significant buildings and site planning for new residential districts.Footnote84 As a result, a non-Soviet international influence is highly apparent in Estonian plans for large housing estates, a phenomenon that can be attributed, at least in part, to western knowledge and information about city planning from international sources. Notably, foreign architectural magazines were used in universities as teaching materials. Similar phenomena are recognized in Lithuania, where Dremaitė argues that modernist aesthetics and western-oriented ambitions of Baltic architects were reflected during Soviet times in mass housing as architects sought to modernize cities and also declare their membership in an international cadre of modern architects.Footnote85 We thus find support for a ‘westward gaze’Footnote86 among architects in Estonia, matching a pattern in the Baltics, as an expression during Soviet times of national and cultural identity.

Our research confirms significant roles for bold and daring local architects in the Baltic republics in planning and designing large socialist housing estates. In the FSU, town planning was recognized as a critical function since it ensured the propagation of socialist ideology by translating collectivism to urban built environments which would endure. Our interviews with key architects of socialist housing estates revealed that clever interpretation of the norms and guidelines was required for architects to achieve a specific vision, and that experience and confidence helped architects to perfect the practice of creative interpretation of Soviet dicta. Architectural and planning officers in State Building Committees were known to avoid the commands of power, when possible, while working earnestly to improve the social space of cities.Footnote87 Architects in Estonia – and perhaps no other USSR republic – were permitted to practice privately (in addition to their state employment), designing detached homes and smaller buildings (interviews with J. Lass, 2016; I. Raud, 2016).

Our detailed investigation of mikrorayon in Tallinn demonstrates that professional architects were represented in almost all levels of official decision-making in town planning processes that produced large housing estates. The State Building Committees in the USSR republics – often referred to as the ‘architectural KGB’Footnote88 – were traditionally led by a chief architect. The leader of the State Building Committee of Estonia from 1965 to 1988 has said that he accepted the position out of loyalty after being warned that if he did not assume it, a Russian would be imported to direct the institution. Undisturbed by voices of the public nor landowners, the chief architect of Soviet Tallinn was solely responsible for all decisions with spatial dimensions.

Conclusion

The massive scale of residential districts in socialist urban space required a comprehensive approach for an unprecedented scale of urban development. Chief architects, when designing mikrorayon, were tasked with designing myriad inter-related urban systems: proposing a road and traffic system, locating services and recreational areas, conducting mobility planning, establishing infrastructure, and orchestrating the compositional structure of new urban fabric. We synthesize our findings to conclude that, in undertaking these enormous challenges, architects in socialist Estonia (as well as Latvia and Lithuania) can be considered visionary city-builders who, when handed standard building designs for residential space, seized opportunities to innovate in site design and layout, embracing possibilities to create unique built environments in vast housing estates that influenced urban landscapes. We further find that architects appropriated the maximum authority they possibly could (and perhaps even overreached in certain cases) within the communist system, helping them to create state-of-the-art modernist living environments that shaped lives in important ways.

What resulted were distinctive modernist spaces that, although they contained standard Soviet residential buildings at their core (this could not be helped), were otherwise state-of-the-art. Apartments in new housing estates provided coveted conveniences (for example, modern kitchens, comfortable toilets and washrooms, central heating) that were superiour to amenities offered in the contemporaneous pre-Second World War housing and were thus quite prestigious.Footnote89 Individual apartments in new Estonian housing estates had grown larger during the Soviet years, and, by the late Soviet years, Estonians enjoyed the highest living space per capita at 11.7 m2 in the Soviet Union (the USSR average was 9.4 m2).Footnote90 Only budget constraints and notoriously cheap construction materials dampened the modernist vision that Soviet-era Estonian architects created for new residential space in Estonia’s capital city (interviews with I. Raud, 2016; D. Bruns, 2013; O. Zhemzhugov, 2013).

If the conditions in Estonia that allowed town planning innovation that we describe in this article had not existed, built environments in housing estates could be of much lesser quality than what endures today.

We also demonstrate a new perspective of Soviet-era city planning in Estonia by helping to correct inaccurate assumptions that architects’ contributions to city planning practice were generally weak and strongly controlled by the Soviet system through unchallengeable designs and plans from the USSR central party. Based on detailed analysis of original planning documents, we suggest that, regarding site planning for mikrorayons, the regulations issued in Moscow played a less important role in town planning outcomes in Estonia than previously assumed for USSR republics. While it was necessary for architects to strictly adhere to density norms, the physical structure and site planning of mikrorayons was, as a rule, the outcome of original design processes by local architects who were strongly inspired by modernist ideals popular at the time throughout the western world. We depict in this article a series of three large housing estates, built in the capital city during the Socialist years, showing the relatively powerful position of Estonian architects in socialist city-building processes and how, using more information from abroad than is often recognized, they gained expertise in modernist city planning techniques and produced original and state-of-the art designs. The process we describe in this article produced more desirable housing estates in Estonia than would result from strict adherence to system constraints, giving party leaders exemplary town planning ensembles to support residential expansion, while Estonian architects experienced a supportive atmosphere (contrary to common assumptions about the USSR) to pursue modernist ambitions that they hoped would be admired beyond the borders of the Soviet Union.

Acknowledgements

When this research was conducted, Daniel Baldwin Hess was a visiting scholar in the Centre for Migration and Urban Studies at the University of Tartu, Estonia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Pille Metspalu is a doctoral student in the Department of Geography at the University of Tartu, Estonia. In her scholarly work, she explores the complexities of urban planning practice under state socialism and the post-socialist transition. In private practice as an urban planner, her expertise lies in participatory planning and developing town and county plans, and she has created national guidelines for urban planning in Estonia. She teaches urban planning at the university level and is committed to advancing education for planning professionals in Estonia. She is former Chair of the Board of the Estonian Association of Spatial Planners.

Daniel B. Hess, PhD, is Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York. He is also Visiting Scholar and Director of the Centre for Migration and Urban Studies at the University of Tartu, Estonia, where his academic stay is funded by a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme. His research explores market-led urban transformation in post-socialist urban space by exploring how the legacy of town planning affects local and national planning systems.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Domański, Industrial Control; Ericson, Priority, Duality; Ofer, “Industrial Structure,” 219–244; and Shomina, “Enterprises and the Urban Environment,” 222–233.

2 Power, Estates on the Edge; Wassenberg, “Large Social,” 223–232; Gentile et al., “Heteropolitanization,” 291–299; and Kovács and Herfert, “Development Pathways,” 324–342.

3 Andrusz, “The Built Environment,” 478–598; Bater, The Soviet City; Bunkśe, “The Role,” 379–394; DiMaio, Soviet Urban Housing; French and Hamilton, The Socialist City; Frolic, “The Soviet Study,” 675–695; and Herman, “Urbanisation,” 203–220.

4 Hatherley, Landscapes; Lizon, “East,” 104–114; Stanilov, “Nine Housing Trends,” 173–190; Turkington et al., High-Rise; and Wassenberg, “Large Social,” 223–232.

5 Meuser and Zadorin, Toward a Typology, 13.

6 Hausladen, “Planning,” 108.

7 Ibid., 110.

8 Zhuravlyev and Fyodorov, “The Microdistrict,” 37–40.

9 Berman, All That Is Solid and Boyer, The City of Collective.

10 Charley, “The Concrete,” 195–214.

11 Choay, The Modern.

12 Andrusz, “The Built,” 478–598 and Meuser and Zadorin, Toward a Typology.

13 Lehmann and Ruble, “From ‘Soviet’ to ‘European’,” 1085–1107 and Smith, “The Socialist.”

14 Port, “Linnade.”

15 Tosics, “European,” 67–90.

16 Golubchikov, “Urban Planning,” 231.

17 Yanitsky, “Urbanization,” 265–287.

18 Bunkśe, “The Role.”

19 Lizon, “East Central Europe,”106.

20 Meuser and Zadorin, Toward a Typology, 145.

21 Ibid., 153.

22 Ibid.

23 Lizon, “East Central Europe,” 109.

24 Meuser and Zadorin, Toward a Typology.

25 Bater, The Soviet City; French, “Changing Spatial Patterns;” French, Plans, Pragmatism and People; and Lewin and Elliott, The Soviet Century.

26 Dremaitė, “Modern Housing in Lithuania;” Rimkutė, “Soviet Mass-housing in Vilnius;” and Maciuika, “East Bloc, West View.”

27 Kährik and Tammaru, “Soviet Prefabricated Panel Housing.”

28 Tammaru, “Suburban Growth” and Kulu, “Housing Differences.”

29 In 1951, the combined population of cities and towns in Estonia was 490,800; by 1979, the combined number of people living in urban areas was 10,168,000; Puur, “Eesti. Rahvastik.”

30 Kalm, “Saunapidu suvilas.”

31 Port, Architecture and Bruns, Tallinna peaarhitekti mälestusi.

32 Sild, “Modernist City Plans.”

33 Szelényi, “Cities under Socialism.”

34 Tammaru et al., “Temporal and Spatial Dynamics,” 423–439.

35 Andrusz, “The Built Environment,” 478–598.

36 Bruns, Tallinna peaarhitekti mälestusi.

37 Estonprojekt, “The Detailed Planning Project.”

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 McCauley, The Kruschev Era and Peirumaa, “Hruštšovi aja ‘sula’.”

41 Dremaitė, “Modern Housing in Lithuania” and Kalm, “Saunapidu suvilas.”

42 Lankots and Sooväli, ABC-keskused.

43 Port, “Linnade planeerimisest.”

44 Ibid., 35–37.

45 Eesti Projekt, “Väike-Õismäe makrorajooni detailplaneerimine.”

46 Ibid.

47 Stöör, Ühe arhitekti mälestused.

48 Hess, “Transport in Mikrorayons.”

49 See note 44.

50 See note 36.

51 Port, Arhitecture in the Estonian SSR.

52 Ibid., 12.

53 Ibid., 13.

54 Eesti Projekt, “Lasnamäe elurajooni generaalplaan.”

55 See note 48.

56 See note 49.

57 Dremaitė, “Modern Housing in Lithuania.”

58 Port, “Linnade planeerimisest,” 29.

59 Lapin, Arengujooni Eesti.

60 Sootna, “Mõranenud perspektiive,” 12.

61 Ibid.

62 Ibid.

63 Kruusimägi, “Meie kõigi jaoks,” 13.

64 Ibid.

65 Tungal, “Laste lihtaasta,” 7.

66 Roose, “Kilde linnamajandusest,” 4.

67 Ibid.

68 Port, Architecture in the Estonian SSR, 14.

69 Härmson, “Lasnamäest,” 8.

70 Hess and Hiob, “Preservation,” 29.

71 McCauley, The Kruschev Era.

72 Peirumaa, “Hruštšovi aja ‘sula’,” 107.

73 See note 30.

74 See note 46.

75 See note 30.

76 Bruns, “Tapiola,” 49 and Kalm, “An Apartment,” 189–202.

77 See note 30.

78 Dremaitė, “Modern Housing in Lithuania” and Rimkutė, “Soviet Mass-housing in Vilnius.”

79 Port, Architecture in the Estonian SSR; Bruns, Tallinna peaarhitekti mälestusi; and Dremaitė, “Modern Housing in Lithuania.”

80 Pesur, “Kuidas loodi Lasnamäe.”

81 Dremaitė, “The (Post-)Soviet,” 24.

82 Bruns, “Tapiola.”

83 Ruseckaite, “Sovietinu Mietu” and Rimkutė, “Soviet Mass-housing in Vilnius.”

84 Lapin, Arengujooni Eesti and Port, Arhitecture in the Estonian SSR.

85 Dremaitė, “The (Post-)Soviet,” 12.

86 Maciuika, “East Bloc, West View,” 23.

87 Oja, “Voldemar Herkel – oma aja.”

88 Ibid.

89 Kährik and Tammaru, “Soviet Prefabricated Panel Housing,” 204.

90 Bater, “The Soviet Scene.”

Bibliography

- Andrusz, G. “The Built Environment in Soviet Theory and Practice.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 11 (1987): 478–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.1987.tb00063.x

- Bater, J. H. The Soviet City: Ideal and Reality. London: Edward Arnold, 1980.

- Bater, J. H. The Soviet Scene: A Geographical Perspective. London: E. Arnold, 1989.

- Berman, M. All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982.

- Boyer, M. C. The City of Collective Memory: Its Historical Imagery and Architectural Entertainments. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994.

- Bruns, D. “Tapiola.” Arhitektuur, no. 4 (1961): 46–50.

- Bruns, D. Tallinna peaarhitekti mälestusi ja artikleid [The Memories of Tallinn Chief Architect]. Tartu: Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Greif OÜ, 2007.

- Bunkśe, E. V. “The Role of the Human Environment in Soviet Urban Planning.” The Geographical Review 69, no. 4 (1979): 379–394. doi: 10.2307/214802

- Charley, J. “The Concrete Memory of Modernity: Excerpts from a Moscow Diary.” In Tracing Modernity: Manifestations of the Modern in Architecture and the City, edited by Mari Hvattum and Christian Hermansen, 195–214. Londres: Routledge, 2004.

- Choay, F. The Modern City: Planning in the 19th Century. New York: G. Braziller, 1970.

- DiMaio, A. J. Soviet Urban Housing: Problems and Policies. New York: Praeger, 1974.

- Domański, B. Industrial Control over the Socialist Town: Benevolence or Exploitation? New York: Praeger, 1997.

- Dremaitė, M. “The (Post-)Soviet Built Environment: Soviet-Western Relations in the Industrialised Mass Housing and Its Reflections in Soviet Lithuania.” Lithuanian Historical Studies 15 (2010): 11–26.

- Dremaitė, M. “Modern Housing in Lithuania in the 1960s: Nordic Influences.” In DOCOMOMO: Survival of Modern. From Cultural Centres to Planned Suburbs, edited by C. Caldenby and P. O. Wedebrunn, 80–91. Copenhagen: Arkitektur B, 2013.

- Eesti Projekt. “Väike-Õismäe makrorajooni detailplaneerimine [The Detailed Planning Project for Väike-Õismäe].” Authors M. Port, M. Meelak, engineer L. Koemets, ordered by Tallinn City Proletariat Delegates Council Executive Committee Government for Architecture and Planning, 1968.

- Eesti Projekt. “Lasnamäe elurajooni generaalplaan [The General Plan for Lasnamäe].” Authors M. Port, M. Meelak, engineer L. Koemets, ordered by Tallinn City Proletariat Delegates Council Executive Committee Government for Architecture and Planning, 1970.

- Ericson, R. Priority, Duality, and Penetration in the Soviet Command Economy. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1988.

- Estonprojekt. “Mustamäe elurajooni detailplaneerimise projekt [The Detailed Planning Project for Mustamäe Residential District in Tallinn].” Authors Tihomirov, Ilves, Jansen, Tippel, Prahm, ordered by Tallinna linna TSN Täitevkomitee Kapitaalehituse Osakond, 1959.

- French, R. “Changing Spatial Patterns in Soviet Cities – Planning or Pragmatism?” Urban Geography 8, no. 4 (1987): 309–320. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.8.4.309

- French, R. A. Plans, Pragmatism, and People: The Legacy of Soviet Planning for Today’s Cities. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995.

- French, R. A., and F. E. I. Hamilton, eds. The Socialist City: Spatial Structure and Urban Policy. London: John Wiley, 1979.

- Frolic, B. M. “The Soviet Study of Soviet Cities.” The Journal of Politics 32 (1970): 675–695. doi: 10.2307/2128836

- Gentile, M., T. Tammaru, and R. van Kempen. “Heteropolitanization: Social and Spatial Change in Central and Eastern European Cities.” Cities 29, no. 5 (2012): 291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2012.05.005

- Golubchikov, O. “Urban Planning in Russia: Towards the Market.” European Planning Studies 12, no. 2 (2004): 229–247. doi: 10.1080/0965431042000183950

- Härmson, P. “Lasnamäest [About Lasnamäe].” Sirp ja Vasar, no. 9, 1980, 8.

- Hatherley, O. Landscapes of Communism: A History Through Buildings. London: Allen Lane, 2015.

- Hausladen, G. “Planning the Development of the Socialist City: The Case of Dubna New Town.” Geoforum 18, no. 1 (1987): 103–115. doi: 10.1016/0016-7185(87)90024-8

- Herman, L. M. “Urbanization and New Housing Construction in the Soviet Union.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 30, no. 2 (1971): 203–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1536-7150.1971.tb02959.x

- Hess, D. B. “Transport in Mikrorayons: Accessibility and Proximity in Centrally Planned Residential Districts During the Socialist Era, 1957–1989.” Journal of Planning History (forthcoming).

- Hess, D. B., and M. Hiob. “Preservation by Neglect in Soviet-era Town Planning in Tartu, Estonia.” Journal of Planning History 13, no. 1 (2014): 24–49. doi: 10.1177/1538513213512254

- Kährik, A., and T. Tammaru. “Soviet Prefabricated Panel Housing Estates: Areas of Continued Social Mix or Decline? The case of Tallinn.” Housing Studies 25, no. 2 (2010): 201–219. doi: 10.1080/02673030903561818

- Kalm, M. “Saunapidu suvilas. Nõukogude eestlased Soome järgi läänt mängimas [Sauna-party in a Summerhouse. Soviet Estonians Playing ‘West’ Following Finland].” In Kohandumise märgid. Collegium litterarum, edited by V. Sarapik, M. Kalda, and R. Veidemann, 16. Tallinn: Underi ja Tuglase Kirjanduskeskus, 2002.

- Kalm, M. “‘An Apartment with All the Conveniences’ Was No Panacea: Mass Housing and the Alternatives in the Soviet Period Tallinn.” Architektúra & Urbanizmus, Journal of Architectural and Town-Planning Theory 47 (2012): 189–202.

- Kovács, Z., and G. Herfert. “Development Pathways of Large Housing Estates in Post-socialist Cities: An International Comparison.” Housing Studies 27, no. 3 (2012): 324–342. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2012.651105

- Kruusimägi, J. “Meie kõigi jaoks [For Us All].” Sirp ja Vasar 30, no. 1805 (1978): 9.

- Kulu, H. “Housing Differences in the Late Soviet City: The Case of Tartu, Estonia.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27 (2003): 897–911. doi: 10.1111/j.0309-1317.2003.00490.x

- Lankots, E., and H. Sooväli. ABC-keskused ja Mustamäe mikrorajoonide identiteedid [The ABC-Centres and the Identities of Mustamäe Mikrorayon]. Tallinn: Kunstiteaduslikke uurimusi 2008/4. Eesti Kunstiteadlaste ja Kuraatorite Ühing, 2008.

- Lapin, L. Arengujooni Eesti seitsmekümndendate aastate arhitektuuris [The Development Paths of Estonian Architecture in 1970s]. Ehituskunst, Eesti NSV Arhitektide Liidu kogumik. Tallinn: Kunst, 1981.

- Lehmann, S. G., and B. A. Ruble. “From ‘Soviet’ to ‘European’ Yaroslavl: Changing Neighbourhood Structure in Post-Soviet Russian Cities.” Urban Studies 34, no. 7 (1997): 1085–1107. doi: 10.1080/0042098975745

- Lewin, M., and G. Elliott. The Soviet Century. London: Verso, 2005.

- Lizon, P. “East Central Europe: The Unhappy Heritage of Communist Mass Housing.” Journal of Architectural Education 50 (1996): 104–114. doi: 10.1080/10464883.1996.10734709

- Maciuika, J. V. “East Bloc, West View: Architecture and Lithuanian National Identity.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 11, no. 1 (FALL 1999): 23–35.

- McCauley, M. The Khruschev Era 1953–1964. London: Pearson Education, 1995.

- Meuser, P., and D. Zadorin. Toward a Typology of Soviet Mass Housing: Prefabrication in the USSR, 1995–1991. Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2016.

- Ofer, G. “Industrial Structure, Urbanization, and the Growth Strategy of Socialist Countries.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 90, no. 2 (1976): 219–244. doi: 10.2307/1884628

- Oja, U. 2009. “Voldemar Herkel – oma aja arhitekt [Voldemar Herkel – An Architect of His Time].” Eesti Ekspress, January 15. http://ekspress.delfi.ee/areen/voldemar-herkel-oma-aja-arhitekt?id=27685001.

- Peirumaa, R. “Hruštšovi aja ‘sula’ ning muudatused ENSV kunstipoliitikas ja –elus 1950.aastate teisel poolel [Kruschev’s Thaw and the Change in the Art Policy and Life in Soviet Estonia in 1950s].” Master’s thesis, University of Tartu, 2004.

- Port, M. “Linnade planeerimisest [About Urban Planning].” In Riiklik projekteerimise instituut Eesti Projekt 25-aastane, edited by Heino Parmas. Tallinn: Valgus, 1969.

- Port, M. Architecture in the Estonian SSR. Tallinn: Perioodika, 1983.

- Pesur, V. 2003. “Kuidas loodi Lasnamäe – intervjuu Mart Pordiga [How Lasnamäe Was Created – An Interview with Mart Port].” Eesti Päevaleht, September 30. http://www.epl.ee/news/tallinn/kuidas-loodi-lasnamae-intervjuumart-pordiga.d?id=50965394.

- Power, A. Estates on the Edge: The Social Consequences of Mass Housing in Europe. London: McMillan, 1997.

- Puur, A. “Eesti. Rahvastik [Estonia. Population].” In TEA Entsüklopeedia, edited by Ahti Tomingas, 30–34. Tallinn: TEA Kirjastus, 2011.

- Rimkutė, K. “Soviet Mass-housing in Vilnius: Exploring the Consequences of the 1955 Housing Reform and the Rebellion Against Architectural Homogenization.” Master’s thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, 2014.

- Roose, E. “Kilde linnamajandusest [Fractions of Urban Economy].” Sirp ja Vasar no. 31 (1961): 9.

- Ruseckaite, I. “Sovietiniu metu gyvenamieji rajonai Vilniuje: tipishkumo problema [Typical Problems in Soviet Residential Districts. The Case of Vilnius].” Urbanistika ir architektura [Town Planning and Architecture] 34, no. 5 (2010): 270–281.

- Shomina, E. “Enterprises and the Urban Environment in the USSR.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 16, no. 2 (1992): 222–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.1992.tb00170.x

- Sild, M. “Modernist City Plans and Their Importance Today, Planning of Pre-fabricated Panel Housing Estates During the Soviet Period: The Case of Lasnamäe, Tallinn and Annelinn, Tartu.” Master’s thesis, University of Tartu, Tartu, 2014.

- Smith, D. M. “The Socialist City.” In Cities after Socialism: Urban and Regional Change and Conflict in Post-socialist Societies, edited by G. Andrusz, M. Harloe, and I. Szelènyi, 71–99. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

- Sootna, R. “Mõranenud perspektiive Õismäe aknast [Cracked Perspectives from the Window in Õismäe].” Sirp ja Vasar no. 30 (1978): 12.

- Stanilov, K. “Nine Housing Trends in Central and Eastern European Cities During and After the Period of Transition.” In The Post Socialist City. Urban Form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism, edited by K. Stanilov, 173–190. GeoJournal Library. Heidelberg: Springer, 2007.

- Stöör, I. Ühe arhitekti mälestusi [The Memories of an Architect]. Tallinn: Ilmamaa, 2014.

- Szelényi, I. “Cities under Socialism – and after.” In Cities after Socialism: Urban and Regional Change and Conflict in Post-socialist Societies, edited by G. Andrusz, M. Harloe, and I. Szelènyi, 286–317. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

- Tammaru, T. “Suburban Growth and Suburbanisation Under Central Planning: The Case of Soviet Estonia.” Urban Studies 38 (2001): 1341–1357. doi: 10.1080/00420980120061061

- Tammaru, T., K. Leetmaa, S. Silm, and R. Ahas. “Temporal and Spatial Dynamics of the New Residential Areas Around Tallinn.” European Planning Studies 17, no. 3 (2009): 423–439. doi: 10.1080/09654310802618077

- Tosics, I. “European Urban Development: Sustainability and the Role of Housing.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 19 (2004): 67–90. doi: 10.1023/B:JOHO.0000017707.53782.90

- Tungal, L. “Laste lihtaasta mugavustega linnaosas [The Ordinary Year for Children in a District With Conveniences].” Sirp ja Vasar no. 3 (1980): 11.

- Turkington, R., R. van Kempen, and F. Wassenberg. High-rise Housing in Europe: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Delft: Delft University Press Science, 2004.

- Wassenberg, F. “Large Social Housing Estates: From Stigma to Demolition?” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 19 (2004): 223–232. doi: 10.1007/s10901-004-0691-2

- Yanitsky, O. “Urbanization in the USSR: Theory, Tendencies, and Policy.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 10, no. 2 (1986): 265–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.1986.tb00015.x

- Zhuravlyev, A., and M. Fyodorov. “The Microdistrict and New Living Conditions.” Russian Social Science Review 2, no. 4 (1961): 37–40.