ABSTRACT

Genuine engagement about how best to achieve liveable urban futures should be part of planning’s raison-d’etre but it has a chequered history of delivery. Exhibitions harnessing the communicative power of mixed media and linked to a progressive and responsive programme of focused discussion and debate remain relevant to community consultation and civic engagement. Terry Farrell’s concept of the ‘urban room’ to involve citizens in engaging with the past, present, and future of towns and cities offers a contemporary refreshment of the approach propounded by Patrick Geddes from the early 1900s. The possibilities of creating novel and compelling opportunities for civic discourse in this guise are explored in this review article though the Newcastle City Futures pop-up exhibition and events held in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK in 2014. This event carries lessons for imagining how planners, developers, governments, and community groups may come together to critically and creatively forge future propositions for the urban condition.

Introduction

Genuinely engaging communities at higher rungs than the manipulative tokenism recognized in Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation remains an enduring imperative in urban planning processes.Footnote1 In the twenty-first century, as cities become more complex, how do citizens make sense of change and the role of planning in shaping that change?Footnote2 Recent measures to stimulate economic growth, growing disparities in housing provision, controversial infrastructure projects and proposals, the introduction of smart technology, and rising awareness of the environmental costs of extreme weather events, have created uncertainties for urban communities and businesses. At the same time, the ways in which governments and researchers engage and interact with citizens to create effective dialogues are being stretched and challenged.Footnote3 Even where more innovative consultative approaches are rolled out, there is scepticism as to whether anything will change.Footnote4

Adoption of new futures methods that embrace questions of long-term urban trends and innovative democratic participation has been advocated.Footnote5 Many of the challenges facing cities today are not necessarily new; previous decades have seen collective efforts to cope with immense structural changes and rapid urbanization.Footnote6 Making sense of city-wide urban changes, and communicating those changes to wider audiences recall the early twentieth-century efforts by Patrick Geddes to empower civic society through outlook towers, city museums, and civic exhibitions. The continuing relevance of Geddesian thought to contemporary urban planning is periodically reaffirmed and reinterpreted, most recently in commemorating the centenary of his classic text, Cities in Evolution.Footnote7 Moreover, there are direct links with the calls by the recent Farrell Review in Britain to bring about new processes of public participation through the establishment of Geddes-like ‘urban rooms’.Footnote8 This is the specific lens of this paper.

Our paper considers the long-term prospects for cities in the guise of an initiative aimed at creating opportunities for informed public engagement in considering and deliberating urban futures. The aim of the paper is to explore a specific initiative, the Newcastle City Futures exhibition, to engage the public in a debate on urban change utilizing imagery and more creative means, rather than strategies, plans, and traditional consultation methods. Although this approach may seem novel and exploratory in the context of what the British planning system has become in the early twenty-first century,Footnote9 the Newcastle initiative bears some resemblance to past forms of urban engagement that have all but disappeared from the planning landscape. Accordingly, this analysis of the Newcastle City Futures exploratory approach is contextualized by analysis of both historical (Geddes) and future (Farrell) forms, comparing and contrasting the three models of exhibition-based participation. The intent is to identify whether the features embodied in the Newcastle approach relate to the other two exhibition forms, and whether they offer suggestions for the future.

The City Futures initiative, held in Newcastle, UK, in mid-2014 and initiated by Newcastle University, was based around a pop-up planning exhibition and a related series of public events intended to stimulate awareness and discussion of urban change both historically and futuristically. The initiative was intended to demonstrate the communicative power of an inclusive curatorial process with an emphasis on the visual and the participatory as a way to engage people in debate about change in their own city. It was a response to the circumstances and opportunities presented by a particular place, but for a more critical analysis it is necessary to frame the assessment in terms of both Geddes’ and Farrell’s common goal of empowering civic society through spaces of exhibitions and dialogue. The paper thus has five main sections:

the first part recapitulates the animation of civic society in planning knowledge and action by Geddes through city institutions which anticipate the Newcastle initiative;

the second part discusses Farrell’s restatement of Geddes’ ideas as a way of inviting residents into the heart of discussions about change;

the third part describes the Newcastle initiative that captures the spirit and potential of both agendas;

the fourth part considers immediate and foundational impacts across three heads of consideration: the renaissance of the planning exhibition; collaboration; and citizen engagement;

the fifth part compares and contrasts three models of exhibition-based participation: Newcastle City Futures, Geddes’ city museum, and Farrell’s urban room.

The paper concludes by assessing the future prospects for instilling effective discourse into debates over future scenarios for urban communities by embedding such initiatives into mainstream planning and governmental processes.

Patrick Geddes, planning exhibitions and city museums

During the first half of the twentieth century, exhibitions were common in introducing new architecture, planning and design strategies to communities.Footnote10 They helped codify a whole culture of visual and interactive techniques intrinsic to the planning gaze.Footnote11 Prosaic early displays of materials pinned up on walls had evolved by the 1930s into curated events utilizing innovative exhibition techniques intended to stimulate the public imagination. The 1940s represented a peak as national sentiment, progressive professional thinking and public opinion began to converge around the grand challenge of better organizing for peacetime prosperity. These exhibitions showcased beneficent expert knowledge often in highly technical ways but experimented with multi-media. Their major intent was to solicit community support, with political intent, for often far-reaching interventions intended to enhance the efficiency and liveability of urban regions. While the communicative intent often seemed one-way – witness the role of somewhat supercilious ‘planning wizards’Footnote12 in postwar planning exhibitions and filmsFootnote13 – these events successfully brought thinking about urban futures into the public domain at a critical historical juncture.Footnote14 However, by the 1950s, with the planning system thoroughly bureaucratized, there was a general retreat from the idealism of major exhibitions toward more mechanical and desultory forms of public information.

Had it taken hold, an alternate tradition of planning exhibition conceptualized by Sir Patrick Geddes (1854–1932) may have bequeathed a different legacy. Geddes was the great exhibitionist of his day, and spent much of his life lugging an itinerant Cities and Town Planning Exhibition through Great Britain, Ireland, France, and India.Footnote15 Inspired in part by the great industrial expositions of the nineteenth century, this peripatetic showcase was the zenith of his commitment to a universal visualization of the epic trajectories and challenges of urban civilization through the ages.Footnote16 Geddes’ goal was not to never-endingly add to this set-piece large-scale display for public amusement around the world, but rather promote it as an exemplar for the kinds of exhibitions that every city should develop.

His own multi-storey Outlook Tower in Edinburgh was the iconic urban observatory for the modern age.Footnote17 A literal hierarchy of codified knowledge at different geographical scales, it was both museum and laboratory, ‘scientific but practical’,Footnote18 historic whilst forward-looking, intentional yet offering opportunities for reflection. Alongside the displays and surveys was a designated ‘Civic Business-room’ as a discussion hub for ‘practical civic work’.Footnote19 His life-long ideal was to replicate his Edinburgh complex through the proliferation of inclusive ‘city museums’. A year before his death he reiterated this vision of ‘an educational museum in every city and village for social cohesion and public betterment’ to the anarchist Paul Reclus.Footnote20

The mission of these local museums was unambiguously educational as dedicated community-based spaces for enhancing citizen engagement in the narrative of civic life of individual towns and cities. In Cities in Evolution published over a century ago he envisaged such spaces ‘as familiar an incident of the city’s life as is at present its exhibition of paintings’ and ‘veritable powerhouse[s] of civic thought and action’. All of this was in line with his commitment to a town and gown engagement extending and exposing interdisciplinary academic studies to the broader community.Footnote21

Geddes outlined this dream in numerous fora, but notably in an address at the University of London even before the modern town planning movement had come about.Footnote22 His local museums were conceived as agents of citizenship and tools to promote civic consciousness. Their foundational resource would be the documentation generated by wide-ranging civic surveys, such as Charles Booth’s detailed mapping of social classes in London from the 1880s. They would be dedicated to detailed historical and geographical analyses. Their flavour would be interdisciplinary in deference to urban complexity and applied in acknowledging the practical problems to be solved. One of his acolytes fleshed out the idea into a composite of ‘teaching centre’, ‘thought exchange’, ‘bureau of municipal information’, ‘academy of civic art’, and ‘office for suggestions’.Footnote23

Geddes’ preoccupation was that ‘the ordinary citizen should have a vision and a comprehension of the possibilities of his [sic] own city’ and a ‘permanent centre for Civic Studies’ was the best means to this end.Footnote24 His family and disciples sought to keep that dream alive into the post-1945 period, long after his death.Footnote25 Driven by historic preservation, cultural tourism, and architectural studies, after the 1980s, city museums did gain a foothold in some cities, especially in continental Europe.Footnote26 The city planning exhibition hall phenomenon in many Chinese cities has some similarities but its drivers are rooted more in top-down state power and city marketing.Footnote27 Privately funded centres promoting sustainable urban development such as Siemens’ The Crystal in London Docklands have imaginative displays but the ultimate message trends to corporate salvation.Footnote28 The Geddesian spirit is more evident where museums have proactively engaged with public opinion in futures thinking addressing pressing contemporary challenges. For example, the Museum of Modern Art in New York has showcased the work of creative professionals in response to urban crises such as climate change.Footnote29

The critical museum studies literature has discussed issues related to the selection of material for exhibitions, and the potential wielding of power of curators in the selection and display of artefacts, and the construction of particular values that then might accrue.Footnote30 Karp and Lavine have argued that all exhibitions are necessarily selections and the portrayal of arguments of one kind or another, but that it is important not to claim a total comprehensive approach in any exhibition staged.Footnote31 Curators are advised to leave space to allow visitor constructions of material and interpretations.Footnote32 This is intended to develop a neutral space of trust in the exhibition space.Footnote33 This has included the possibility of developing aspects of co-produced or co-designed exhibitions where the physical space becomes more of a host for multiple features and values.Footnote34

Terry Farrell’s urban rooms

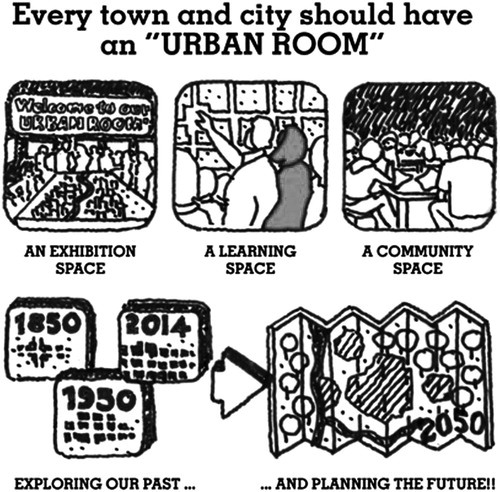

The Farrell Review of Architecture and the Built Environment, commissioned by the UK Government, sought to highlight the importance of governments, professionals, and others engaging positively with citizens on large-scale changes in the built environment.Footnote35 Amongst various recommendations, it sought to bring the diverse range of engagement processes currently in vogue in different urban areas to a physical intersection. Lamenting current inadequate methods of engaging citizens in discussions about broad urban change rather than planning policy or development proposal, Sir Terry Farrell proposes a new type of place-based venue: ‘an urban room where the past, present and future of that place can be inspected’Footnote36 (). The suggested design is based on international city galleries and is characterized by the integration of a learning environment, a community space and an exhibition area centred on a physical or virtual city model to be produced and maintained by local technical colleges or universities. The central presence of a model recalls a staple format of traditional planning exhibitions in the mid-twentieth century, intended to highlight and create discussion about planned developments. The Farrell Review recommends that urban rooms should be branded with the name of the location and be jointly funded by the public and private sector, so they are not exclusively owned.

Figure 1. The idea of an urban room outlined in the Farrell Review report of 2014. Source: The Farrell Review.

Although elsewhere Farrell has referred to Patrick Geddes’ ‘leadership and vision in urbanism’,Footnote37 his wide-ranging non-partisan review of architecture and the built environment makes no reference to him. Yet the urban room recommendation channels his spirit. There are striking parallels between the Farrell concept of a joint exhibition, learning and community spaceFootnote38 and Geddes’ earlier proposition for a composite, interdisciplinary venue used variously for teaching, information exchange, and promoting good civic design.Footnote39 Geddes’ ideal of including a ‘Civic Business-room’, mentioned above, as a meeting space for discussing ‘various endeavours towards city betterment’ reinforces the connection.Footnote40 The urban room is envisaged as an all-of-community outreach activity supported by regionally based professional bodies with professional interests in planning, landscape, architecture, conservation, and engineering.

Farrell’s ideas were taken forward initially by the establishment of a network group called Place Alliance, led by UCL, that set up specifically an Urban Rooms Network (URN) to encourage that part of Farrell’s ideas.Footnote41 Surveying the initial responses to the call for urban rooms through the URN reveals a diverse response to the new agenda, characterized by a realignment and rebranding of existing operations, a need to reconcile community appetite for participation with budgetary constraints, varied participation methods contingent on available expertise and funding preferences, discussions about the relative value of digital and physical modelling, and appropriate means of engaging rural and urban communities.Footnote42 Reflecting these concerns, the URN developed a new definition for the urban room around a stated shared mission:

Every town and city should have a physical space where people can go to understand, debate and get involved in the past, present and future of where they live, work and play. The purpose of these Urban Rooms is to foster meaningful connections between people and place, using creative methods of engagement to encourage active participation in the future of our buildings, streets and neighbourhoods.Footnote43

By August 2016, a total of 15 urban rooms had been or were being established, mostly as pop-up spaces and events programmes across England.Footnote44 The new definition retains reference to longitudinal time, but emphasizes creative methods of public and business engagement centred on a physical space, minus the permanent presence of a city model. This in part reflects constraints on physical accommodation and the convenience offered by digital analytics or online platforms, but potentially also preferences for forms of participation that occur at the building or neighbourhood scale as opposed to those attempting comprehensive engagement with the entire city.

As one early initiative ascribing to the title urban room, Blackburn is Open is an arts-led regeneration centre working closely with Blackburn with Darwen Council and linked to planning objectives to revitalize Blackburn Town Centre. It hosts an ongoing series of community-organized events related to placemaking and city branding within under-used spaces and empty shops in the town centre. It coordinates exhibitions, talks, and workshops contributed by willing participants and its most recent temporary urban room was presented as an arts, architecture, and public space festival with an emphasis on placemaking.Footnote45 Despite such imaginative responses here and elsewhere, dwindling local authority funding and a reliance on cyclical grant applications presents a barrier to the long-term, sustainable civic participation envisaged by the Farrell Review.

Designing innovative urban engagement in Newcastle

While the Farrell Review was underway, in winter 2013–2014, a group at Newcastle University’s School of Architecture Planning and Landscape independently decided to initiate their own innovative city-wide participatory method. The inspiration lay mainly in assessing whether urban change could be interrogated and communicated through more visual means such as models, photography, and film than current planning and localism agendas permitted.

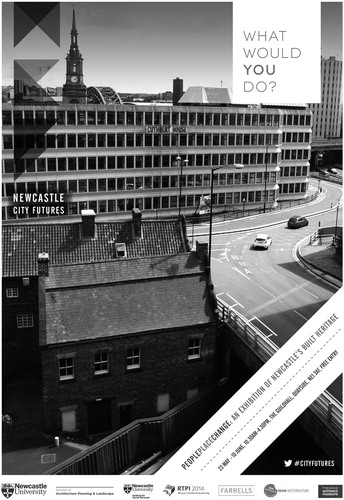

The project teamFootnote46 decided that the initiative would not form part of any formal planning consultation, nor would it be an instrumental exercise to produce a plan. The project would not be owned by the city council, or by any one group of professional planners, architects or developers. Rather, it would be led independently and resourced by the university but the contents would be forged from a partnership of the public, private, community, and voluntary sectors. The university’s main partners comprised representative groups from all sectors: the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI); Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA); Farrells; Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums; Newcastle City Council; Newcastle Science City; Newcastle Libraries; Nexus (metro); Newcastle Airport; Ryder Architecture; Byker Lives; Archive for Change; and Amber Collective. Each partner organization would support the initiative by loaning material and expertise, selecting themes and exhibits and event topics, rather than through a traditional top-down curatorial exercise ().

Figure 2. One of the four posters designed to advertise the exhibition, produced also as a postcard for distribution.

The original idea for an exhibition celebrating architectural and planning achievements in Newcastle and Gateshead since 1945 became a much larger exhibition as a backdrop to a rich programme of events over several weeks.Footnote47 The venue was the disused Grade I listed Guildhall, prominently located on the Quayside adjacent to the iconic Tyne Bridge. The event was opened by the late Professor Sir Peter Hall in late May 2014 and ran for three weeks, opening seven days a week between 10.00 and 18.00 as a free initiative, supervised by half a dozen student volunteers from Newcastle University and the project team.

The exhibition displayed information and artefacts to describe instances of past, present, and future urban change, through diverse media including exhibition boards with explanatory text and graphics, historic films, community oral histories, unseen photography of the city between 1945 and 2005, and architectural models depicting unbuilt, built, replaced and future developments (). The exhibition did not shy away from the often-criticised 1960s planning solutions enacted by the then city council leader T. Dan Smith and chief planner Wilfred Burns.Footnote48

Figure 3. Perspective on part of the exhibition urban room area showing models, photo and story boards, and general layout. Source: authors.

The focus of the exhibition was on the city, both Newcastle and Gateshead on either side of the River Tyne, rather than differentiated by administrative boundaries. Among specific developments featured were the planning of housing in the 1960s including the Byker Estate, community life in Shields Road, the conservation of Grainger Town, the building of Eldon Square shopping centre in the 1970s, the pedestrianization of the city centre, the redevelopment of St James’ Park, the Central Motorway construction, the transformation of the international airport, the building and opening of the Metro network, and the creation of the regenerated Quayside from the 1990s. Several radical development proposals of the past that were never built were included to show how plans sometimes do not come to fruition, including plans for a city centre subterranean urban motorway, a ‘Tyne Deck’ concrete platform over the river from 1969, and a joint Newcastle United FC/Sunderland AFC stadium proposal from the early 1990s.

Decisions relating to exhibition design reflected an inclusive, participatory ethos, with display boards and publicity material dispensing with planning syntax, legalese, and policy terminology, to encourage more open dialogue. Material from diverse sources was arranged into a series of distinct spaces. For example, the exhibition included the original architects’ model of the infamous brutalist Trinity Square development of 1967 (also known as the ‘Get Carter’ car park after the 1971 Michael Caine film in which it was featured; ). An old street sign was displayed from one of the demolished terraced streets in old Byker, contrasting with the now-celebrated Ralph Erskine 1970s public housing scheme on the site. An original iron manhole cover from another brutalist product, the now demolished 1960s Killingworth Estate, that uniquely displayed the plan of the housing layout and installed at the time of construction to assist residents to navigate their way through their new ‘alien’ surroundings, was displayed. A 25-minute film from 1980 showing the planning, design, construction and opening of the Tyne and Wear Metro was screened on a loop and attracted significant interest. Other short archive film clips showing Newcastle’s communities in the 1950s and 1960s were played on monitors, and historic sound recordings of residents of Byker talking about moving from their old terraced housing into new housing estates could be listened to on iPods. Items were selected by the initiative’s partner organizations and the project team and members of the public volunteered material after requests were issued through social media. All exhibition materials were intended to prompt visitors into thinking about urban change: what has been lost and what has been gained, noting that for every intervention there are at least two different perspectives.

Figure 4. The original Owen Luder Architects’ model of Trinity Square car park of 1967, on display in the exhibition. The model attracted the interest on members of the public and professionals and became a star centrepiece with visitors posing for ‘selfies’ next to the model. Source: author.

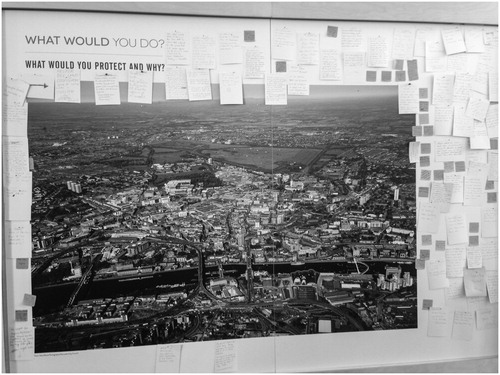

To capture public perspectives on the contemporary city, the exhibition purposefully integrated interactive elements within displays. For example, a large oblique aerial photograph of the city was displayed under the heading: ‘What would you protect?’. Participants were invited to identify places they valued by marking them using coloured pins and writing postcard thoughts on existing and planned development (). Over 100 separate comment cards were pinned to the exhibition wall and over 200 coloured pins attached to the aerial photo baseboard. Although there was little surprise that the public had identified some of the city’s more well-known buildings and features for protection, such as St James’ Park football stadium, the Town Moor, St Nicholas’ Cathedral, and the Quayside, the process also uncovered an affection for some of the city’s late twentieth-century buildings, including the Newcastle Civic Centre (1968), Swan House roundabout (1973), and the Centre for Life (2000).

Figure 5. The large oblique aerial photograph posted on backboard of Newcastle and part of Gateshead inviting visitors to the exhibition to pinpoint areas and buildings they wished to protect and post comments on places they wished to see change. Source: authors.

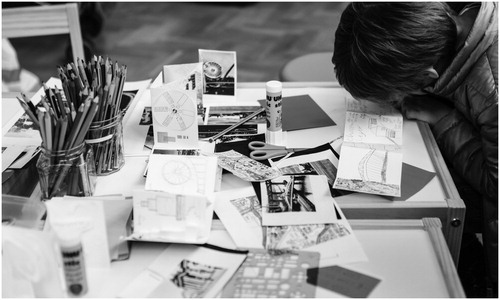

A complementary evening event series ran in concert to the daytime exhibition within a dedicated space called the City Forum for partner organizations to present their ideas for the future of Newcastle and the wider region; each event attracted an audience of up to 100 participants per session. They acted as a catalyst in stimulating a larger conversation that would endure beyond the life of the exhibition and enabled the public to interact comfortably with key decision makers and businesses. Recognizing the need to produce a convivial, accessible environment for all visitors, a dedicated family space was created to encourage engagement with younger generations (). These allowed the creation of new children’s and young people’s visions of their city, a musical city soundscape initiative for teenagers, and map making activities. In another dedicated area Lego, playmats and drawing opportunities enabled younger children to pursue less formalized fun. The unanticipated use of the exhibition by local schools for its education value and by local business investors to showcase change across the city were testimony to an appetite to consider urban change.

Figure 6. The family area of the exhibition proved popular with young people who could draw and design their own future city. Source: authors.

At its formal ceremonial close, the exhibition and events programme series had received 2400 visitors, held 27 events, received over 100 ideas about the future of the city, all largely through recommendations by word of mouth, and created city-based collaboration across more than 25 organizations.Footnote49

Evaluating Newcastle City Futures

The Newcastle City Futures exhibition and events programme certainly galvanized public interest in urban change. It had attempted to reach out to society and business in an open approach that chimed with the sentiments of both Patrick Geddes’ civic museums and Terry Farrell’s urban rooms, and yet was uncommon as a contemporary planning engagement style. Below we evaluate the achievements of the initiative in relation to three issues: as a renaissance of the planning exhibition form; as a style of exhibition collaboration; and as a method to engage citizens.

The planning exhibition reinterpreted

The links with past exhibitionary practices in planning were organic rather than didactic but happily underscored the continuing relevance of actively engaging with broader publics in promoting better understanding of urbanization and city-making as a guide to informed and consensus-based decision-making about the future.Footnote50 The exhibitionary practices employed in Newcastle were a mix of the traditional and the digital, old and new media, instructive and participatory, historical and forward-looking. Patrick Geddes was always more interlocutor than curator and would have understood immediately, along with the innovation and serendipity involved.

At an early stage, the project team decided to make the initiative more than just an exhibition in terms of what visitors could expect to find, and also in terms of how even conventional-looking displays were choreographed. The team recognized that there was a danger that they would impose pre-given historic perspectives through selection of exhibition materials and, because of their backgrounds, provide a narrowly professional view of planning’s role. This was avoided by allowing the public to curate their own material and handing over some responsibility for exhibit selection and speaking topics to partners. This approach broke with the more technocratic tradition of the exhibition as a platform for experts to impart knowledge. More in tune with the present day, it proved a successful move in permitting a shared approach to and ownership of the contents.

The decision to include the ‘unbuilt’ thematic was intended to communicate to wider audiences the notion of how planning and urban change sometimes does not happen or happen in the way originally intended. Rather than view developments in the city’s history as pre-given and everlasting, the exhibition took care to present change as the result of deliberative and, at times, controversial decisions. The demonstrable engagement of visitors indicated a positive response to the expectation of encouraging debate and enabling fresh ways of thinking. It created a chance to look at where the city had come from in order to generate debate on where it might be headed.

The self-conscious acts of positioning and framing the models and juxtaposing aerial photography against views of the contemporary city underpinned the key concept of linking past and present developments and experiences to support the reimagining of future urban development. Responses from participants record a positive reception. The re-exhibiting of Farrells’ 2004 ‘Geordie Ramblas’ scheme proposing new pedestrian routes through Newcastle city centre () reawakened interest in the ideas and prompted Farrells to relabel the model as ‘current work’. The manhole cover caused a flurry of attention, many older residents of Killingworth visiting the exhibition remembered these covers in-situ. A fragment of concrete from the demolished Trinity Square Car Park became a talking point to lament its loss from the skyline and also comment on the quality of the new development that replaced it. The unbuilt Tyne Deck exhibit was the subject of a BBC Radio Newcastle piece live from the exhibition.Footnote51 All these may seem like unorthodox planning or even museum exhibits, but in presenting these materials as legitimate contributions to a wider discussion, the exhibition allowed multiple voices and place memories.

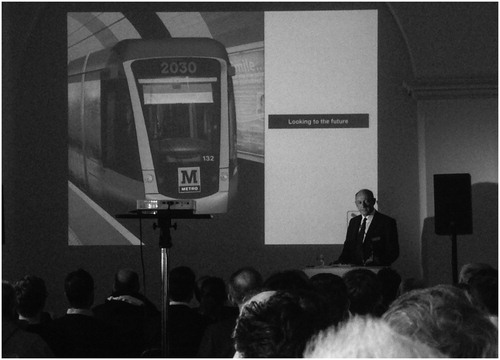

Figure 7. A partner event in the exhibition space: The Metro 2030 public presentation, one of 24 free events that occurred in the exhibition urban forum space that attracted a large audience to debate long-term expansion plans. Source: authors.

The key elements of the exhibition anticipated the concept of the urban room. The exhibition and event series choose to explore change through the lens of the past, present, and future of city places. Whereas physical models were central features, the initiative benefited from cross-sector support, the regional professional bodies made prominent contributions, but did not control the content, and the staging of the initiative within a neutral venue free from alignment with a particular local authority or consultancy agenda allowed the exhibition to reference, first and foremost, issues of place.

Collaboration

Although the exhibition and associated events were not intended to apply aspects of collaborative planning in practice or as a conceptual frame,Footnote52 there was an intention on the part of the organizers to create an inter-organizational collaboration platform of trust that could endure beyond the lifetime of the exhibition. This was partly intended as a response to public frustration at existing political and democratic fora and consultation methods, particularly within planning.Footnote53

The choice of a neutral venue, a new label and logo, the distance from local government and professional bodies, the plain English usage, and the opening up of the design and shaping of the event to a wide range of partners were all conscious decisions. They bear some resemblance to more open styles of collaborative democracy. They were viewed as necessary not only to generate engagement, but also pragmatically to secure the trust of organizations if the exhibition was going to become a platform upon which further dialogues could commence. For this, there was no timescale objective but rather expectation of a medium to long-term programme that would require commitment and support from partners.

When the exhibition opened, professional planners from the local authority acknowledged they were initially mystified as to why it had been organized; not only because the initiative was established by agencies other than the council, but also because there was no apparent instrumental reason to hold a public event not leading to the production of a plan or strategy: ‘I can’t see the point of doing it’, one commented. On the private sector side, there was also initial reluctance to engage with the public more openly in the exhibition space. One business leader was reluctant to step into the City Forum because, he said, ‘The public just complain about everything’. After some persuasion, he duly participated and was astonished to find a public brimming with innovative ideas that not only could shape the future city, but also contribute ideas for his own business. That single experience enabled a rethinking of his business engagement process and a realization on the part of the private sector that citizens can play not only a positive role in shaping the future of the business but also become advocates for investment to higher political authority. Real estate interests and business investors – unprompted – started organizing meetings in the exhibition space against the backdrop of visual features of the city’s dynamic urban change. The project team was more than happy for the space to be adopted by various groups in the city as this signposted an initiative successfully developing a life of its own ().

Engaging citizens

Recent debates have posited the case for enhancing the role of the non-expert in planning deliberations as part of a more concerted deliberative democratic effort. Inch argues that ‘ordinary citizens’ have a vital role to play in planning debates, which is often overlooked: ‘hidden dimensions of citizens’ experiences that have significant implications for understanding the political and democratic possibilities of political participation in contemporary planning’.Footnote54 The value of encompassing non-expert or non-mainstream knowledge into the creative problem-solving process of planning is particularly relevant during an era where the public are seeking out more technological and creative ways to channel their views.Footnote55

The Newcastle project team was apprehensive initially about whether the exhibition would fully capture the public’s imagination, particularly with its focus on late twentieth-century urban change. Partner organizations, particularly professional planners and developers, had half-expected the public to unleash a torrent of abuse. But in the event, there was negligible negativity, at least stated in public, and only two negative comments out of 100 were posted on the interactive display board during the entire exhibition. This positive attitude surprised everyone since it disrupted anecdotal and stereotyped views about the public’s role in planning.Footnote56 Large numbers of people really did want to engage directly with both the private and public sectors to talk about what they would like to see in Newcastle and Gateshead, and contribute positive, constructive and thoughtful comments about the future.

Issues raised by this interactive process included calls to fully pedestrianize Grey Street in central Newcastle, the introduction of cycle lanes, improving shopping, extending the Metro, greening the city, a new southern entrance to the railway station, and the provision of affordable housing in the city centre. The sceptical professional planners from the city council were amazed to discover the public able to engage with a range of city-wide strategic planning issues and make relevant contributions. As the exhibition and events progressed, they revisited the space during the daytime to pick up on participants’ conversations. An important feature in these contributions was their free-range quality: they were not constrained by the need to pigeonhole comments into particular categories or definitions, as is so often the case with planning consultations.

Comparative exhibition-based participation: Geddes, Farrell, Newcastle

In assessing ‘what worked’ in Newcastle, and what elements might offer ideas to shape more innovative methods for future planning in places, it is useful to benchmark the Newcastle approach against those advocated by Geddes and Farrell. provides a compare and contrast perspective of the three types of planning exhibition, arranged against a set of key attributes.

Table 1. Comparing and contrasting three models of exhibition-based participation.

The Newcastle City Futures exhibition was not intended to be a practical version of either Geddes’ civic museum or Farrell’s urban room, but there are some common features of all three approaches that are worth examining. Newcastle attributes that aligned with both Geddes and Farrell were a desire to focus on past, present, and future within the same room, and to encompass the use of multi-media and activity spaces alongside more static elements.

Farrell has written more recently of planning and design as rooted in ‘the interdependence and shared development of both city and citizen’.Footnote57 In all three models, the intention was to open up public debate although with the Farrell Room there is both a greater professional stewardship and the possibility to create a greater advocacy role. Given that the Newcastle approach was always intended to be temporary, advocacy was not something that could be achieved within the duration of the event. Geddes saw his model as a permanent museum to aid civic consciousness; for both Farrell and Newcastle, the content, role and location reflect the need for a more pragmatic multi-partnered response. Another feature of the civic museum was that it could embrace multi-scalar and comparative planning perspectives. Although neither Farrell nor Newcastle advocated such a prominent strategic intelligence and dissemination role, such roles could be created even in pop-up exhibition spaces through creative use of digital displays and live data feed with support of civic authorities and other agencies.

The features that are common to all three models and could work well when applied to most places are those that are: targeted to broad non-expert audiences; predominantly image-based; and are housed in neutral central venues.

Reflections and conclusions

In Cities in Evolution, Geddes reported optimistically on prospects for a new outlook tower in Newcastle upon Tyne where the City Council had gone as far as passing a resolution ‘that is desirable to establish a Civic Museum for the City, wherein may be illustrated among other things the history of the town, and the growth and development of the municipal, social, and industrial life of the City’.Footnote58 It would be a century before this notion was realized and in a quite different context. Although the Newcastle City Futures exhibition was not consciously initiated in emulation of Geddes’ ideas, it testifies to their continuing relevance. The spirit of the enterprise recalled his aspirations, as captured in staging his Cities and Town Planning Exhibition in Dublin in 1911, for leveraging ‘fuller social comprehension and warmer civic impulse’ towards ‘useful and constructive purposes’; the ‘arousal of the Citizen’ and ‘the needed revivance [sic] of the City’ went hand-in-hand.Footnote59

The initiative was also progressed in parallel with, but separate to, Terry Farrell’s design review and his recommendation for the creation of urban rooms. It further demonstrated, albeit fleetingly, the potential of the urban room as a space for facilitating improved civic discourse. Although visitors to the exhibition were able to take the display at face value and treat it as an exhibition of the city and as a snapshot of time, at another level this initiative was intended to be the start of a new big conversation across the city about Newcastle and Gateshead’s prospects for a long-term future, generated through open dialogue and partnership.

All exhibitions wield power, and have to balance the practicalities (available time, space, materials) against the implications (telling a certain kind of story, the bits missed out, the value constructed, etc.). The Newcastle exhibition attempted to balance these issues in the limited time available, and sought to include as many partners as possible and multiple perspectives and viewpoints, to open up discussions rather than attempt to provide an ‘authorised’ chronological story.

Reflecting on the process of exhibition design and curation alongside the emerging debate around implementation of Farrell’s recommendations and the apparent success of the Newcastle project has revealed what perhaps the planning community implicitly knows but rarely express today: the successful planner will be a good presenter, a synoptic thinker, an historian and a futurist, able to draw out the essence of a proposal and its design principles to inform community participation or support developer design iteration but, critically, also allow the space for ‘ordinary voices’ to co-design ideas. The legacy and spin-offs from the event constitute significant developments and opportunities for discussing, researching, planning and investing in the city. This has indeed happened with Newcastle City Futures that has developed from a one-off pop-up event into, sequentially, a policy advisory process, a research project, and more recently a project facilitation platform.Footnote60 Therefore, in many guises, Newcastle City Futures has continued beyond the exhibition and all of these pathways reflect the kind of dialogues and linkages which Geddes – and Farrell – envisaged as spinning off from their projected urban meeting spaces.

Internationally, publicly funded city galleries have achieved similar or superior resourcing for permanent and thematic exhibitions, virtual mapping and physical city models and linked to events series; for example, the planning focused city galleries of Hong Kong City Gallery and Singapore City Gallery. As these city galleries are affiliated and funded through governance structures linked to city planning authorities the model is unlikely to find advocates for direct translation to the UK context on grounds of lack of public finance, local authority institutional bias or public mistrust in the planning process. This instinct is clear in the Farrell Review’s recommendation that urban rooms should exist outside the local authority jurisdiction, for fear that association with a planning policy or political agenda could stifle public debate.Footnote61 The Newcastle project happened because the university was prepared to fund the project.Footnote62 This may be one model that could develop in the future with the academy owning or at least resourcing the initiatives.

While Farrell’s conception of the urban room and the Newcastle City Futures initiative find continuity with the programmatic and participatory practices of Geddes’ civic museum, emerging practices with the Urban Room Network elude neat programmatic comparisons with precedents from the established, historical typology of planning exhibitions.Footnote63 The Newcastle City Futures project team sought to effectively extend the planning exhibition by embracing new media and digital technology and shifting partnerships practices. By doing so, it provided an opportunity to explore, albeit for a limited time, the potentials and obstacles of encouraging city-wide participation within a format similar to the Farrell Review conception of urban room.

Taking a broad perspective of urban change, with a less cautious approach to engage citizens and businesses on aspects of urban living, rather than focused on planning-defined issues, also necessitates a critical rethink of how we educate future generations of planners, architects and designers that, in turn, has led to changes in the academy.Footnote64 Perhaps what is needed is a ‘futures infusion’ of education that is not constrained by current forms of planning or indeed by narrow definitions of activity.Footnote65 The long-term needs of cities that need managing, include a concern with resilience, economic viability, housing need, demographic trends, infrastructure renewal, smart disruptive technology, and liveability. These issues do not, by their very nature, fit into neat planning boxes and yet planning is critical to generate long-term and synoptic perspectives that harness knowledge, expertise, and methods from across disciplines within a fragmented landscape of responsible organizations addressing specific place-based needs.Footnote66 The skills associated with designing and staging a planning exhibition were an integral feature of modern town planning in the first half of the twentieth century. The Newcastle experiment and its downstream impact suggest that it is time that the city-wide exhibition returned as an extension to proactive civic participation, but a key question remains: who should resource and manage those spaces?

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Emma Coffield, David Mitchell, and Anne Fry for their active involvement in the exhibition, and to Mark Shucksmith, Tim Townshend, Charles Harvey, and Chris Brink in their support of staging the event. We would like to acknowledge the suggestions of John Gold and the critical and helpful comments of the referees in allowing us to shape revisions to the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Mark Tewdwr-Jones is Professor of Town Planning and Director of Newcastle City Futures, Global Urban Research Unit, School of Architecture Planning and Landscape, Newcastle University, UK. He is an internationally-recognised authority on urban and regional planning, governance and politics of the city, public participation in places, urban futures, and urban change and visual media.

Dhruv Sookhoo is an ESRC Doctoral candidate and Visiting Lecturer, Global Urban Research Unit, School of Architecture Planning and Landscape, Newcastle University, UK. He is a chartered architect, chartered town planner and has worked professionally in housing development and residential design. He has long promoted housing design quality within developing organisations, and design-led, participatory approaches for effective collaboration between practitioners and communities.

Robert Freestone is Professor of Planning, Faculty of the Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Australia. He is a renowned authority on urban policy and the development of planning, theory and practice, regional and metropolitan visions, heritage and conservation, infrastructure provision, and urban design.

ORCID

Robert Freestone http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4265-5059

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Arnstein, “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.”

2 Healey, Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies.

3 Fung, “Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance.”

4 Hay, Why We Hate Politics; Tewdwr-Jones and Thomas, “Collaborative Action in Local Plan-making.”

5 Daffara, “Rethinking Tomorrow’s Cities”; Freestone, “Futures Thinking in Planning Education and Research”; Ratcliffe and Krawczyk, “Imagineering City Futures”; Tewdwr-Jones and Goddard, “A Future for Cities?”

6 Hall, Cities of Tomorrow.

7 See the special issue of Landscape and Urban Planning, October 2017 including papers by Cerra, Muller, and Young, “A Transformative Outlook on the Twenty-First Century City”; Amati, Freestone, and Robertson, “Learning the City”; and Bromley, “Patrick Geddes and Applied Planning Practice.”

8 Farrell Review, Our Future in Place.

9 Tewdwr-Jones, Spatial Planning and Governance.

10 Freestone and Amati, Exhibitions and the Development of Modern Planning Culture.

11 Freestone, “The Exhibition as a Lens for Planning History.”

12 Gold and Ward, “Of Plans and Planners.”

13 Tewdwr-Jones, Urban Reflections.

14 Larkham and Lilley, “Exhibiting the City.”

15 Meller, Patrick Geddes.

16 Welter, Collecting Cities.

17 Welter, Biopolis.

18 Zueblin, “The World’s First Sociological Laboratory,” 588.

19 Geddes, Cities in Evolution, 326.

20 Ferretti, “Situated Knowledge and Visual Education,” 10.

21 Sutherland, “Education as an Agent of Social Evolution.”

22 Geddes, “A Suggested Plan for a Civic Museum.”

23 Ibid., 238–9.

24 Tyrwhitt, “Introduction,” xi.

25 Geddes, “An ‘Outlook Tower’ at Domme, Dordogne.”

26 Calabi, “City Museums.”

27 Fan, “Producing and Consuming Urban Planning Exhibition Halls.”

28 Söderström, Paasche, and Klauser, “Smart Cities as Corporate Storytelling.”

29 Bergdoll, “Rising Currents.”

30 Bennett, “The Exhibitionary Complex.”

31 Karp and Lavine, Exhibiting Culture.

32 Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge.

33 MacDonald, The Politics of Display; Britain Thinks, “Public Perceptions.”

34 Simon, “The Participatory Museum.”

35 Farrell Review, Our Future in Place.

36 Ibid., 56.

37 Farrell, “London Calling,” 44.

38 Ibid., 162.

39 Geddes, “A Suggested Plan for a Civic Museum,” 238–9.

40 Geddes, Cities in Evolution, 326.

41 For further information, see http://placealliance.org.uk.

42 Carmona, De Magalhaes, and Natarajan, Design Governance.

43 Place Alliance, “Urban Rooms.”

44 Ibid.

45 Butterworth and Graham, “Blackburn is Open.”

46 The project team of Newcastle City Futures exhibition and events comprised: Mark Tewdwr-Jones (director), Anne Fry (project manager), Emma Coffield (curator), Dhruv Sookhoo (design advisor) and David Mitchell (designer).

47 The period chosen was intended to contrast to the histories that can be found in other well-established museums and galleries in Newcastle that focus on Roman history, and the medieval and industrialization periods. The post-1945 period is rarely covered through exhibits.

48 Pendlebury, “Alas Smith and Burns.”

49 These covered all sectors and included RIBA, Newcastle International Airport, Nexus Passenger Transport Authority, Amber Photographic Collective, Tyne and Wear Archives, the Stephenson Quarter, Baltic Contemporary Art Gallery.

50 Freestone and Amati, Exhibitions and the Development of Modern Planning Culture.

51 BBC Radio Newcastle, 2017; 2014; Henderson, “How Will Newcastle Look in 2065?”; Henderson, “2,300 Visit Newcastle City of the Future Exhibition”; Evening Chronicle, “2,300 Visit Newcastle City of the Future Exhibition.”

52 Healey, Collaborative Planning.

53 Hay, Why We Hate Politics.

54 Inch, “Ordinary Citizens and the Political Cultures of Planning,” 405.

55 Brabham, “Crowdsourcing the Public Participation Process.”

56 Clifford and Tewdwr-Jones, The Collaborating Planner?

57 Farrell, “There is Only One Thing Worse,” 137.

58 Geddes, Cities in Evolution, 333–4.

59 Geddes and Mears, Cities and Town Planning Exhibition.

60 The legacy of the exhibition has occurred in numerous ways: in 2015 Newcastle City Council established a City Futures Development Group comprising representatives of public, private, community and academic sectors to discuss long term futures for the city. In 2014–2015, Newcastle University undertook a long term research study on the challenges and opportunities for the city, published in report form as Newcastle City Futures 2065. In 2016, Newcastle City Futures became an RCUK/Innovate UK urban living partnership pilot led by Newcastle University to broker new partnerships and facilitate the delivery of new cross-sectoral collaborative projects, some of these having been suggested by the public at the exhibition. Elements of the 2014 exhibition live on: some panels are now on permanent display at Newcastle Civic Centre. And in November 2018, Newcastle University and Sir Terry Farrell announced the launch of a permanent urban room, the Farrell Centre for Architecture and Cities, due to open in 2021. See: https://www.ncl.ac.uk/press/articles/latest/2018/10/world-renownedarchitectdonatesarchiveand1m/.

61 Farrells, Our Future in Place, 53.

62 The entire initiative cost £45,000.

63 Freestone and Amati, Exhibitions and the Development of Modern Planning Culture, 5.

64 Sookhoo, Tewdwr-Jones, and Houston, An Urban Room.

65 Freestone, “Futures Thinking in Planning Education and Research,” 8.

66 Tewdwr-Jones and Goddard, “A Future for Cities?”

Bibliography

- Amati, Marco, Robert Freestone, and Sarah Robertson. “‘Learning the City’: Patrick Geddes, Exhibitions, and Communicating Planning Ideas.” Landscape and Urban Planning 166 (2017): 97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.09.006

- Arnstein, Sherry. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35, no. 4 (1969): 216–224. doi: 10.1080/01944366908977225

- BBC Radio Newcastle, Newcastle upon Tyne, May 1, 2014, interview covering preparation for Newcastle City Futures exhibition.

- BBC Radio Newcastle, Newcastle upon Tyne, June 5, 2017, coverage from the Newcastle City Futures exhibition.

- Bennett, Tony. “The Exhibitionary Complex.” New Formations 4 (1988): 73–102.

- Bergdoll, Barry. “Rising Currents: Looking Back and Next Steps”. Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront. 2010. Accessed August 4, 2017. http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2010/11/01/risingcurrents-looking-back-and-next-steps.

- Brabham, D. C. “Crowdsourcing the Public Participation Process for Planning Projects.” Planning Theory 8, no. 3 (2009): 242–262. doi: 10.1177/1473095209104824

- Britain Thinks. “Public Perceptions of – And Attitudes to – The Purposes of Museums in Society.” 2013. Accessed August 8, 2017. http://www.museumsassociation.org/download?id=954916.

- Bromley, Roy. “Patrick Geddes and Applied Planning Practice.” Landscape and Urban Planning 166 (2017): 82–84. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.08.002

- Butterworth, Carolyn, and Emma Graham. Blackburn is Open. Blackburn ReMade: Revealing the Past Celebrating the Present and Proposing Futures for Your Town. Sheffield: Blackburn is Open and Sheffield University, 2014. Accessed May 27, 2018. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.548591!/file/BlackburnReMade40mb.pdf.

- Calabi, Donna. “City Museums: First Elements for a Debate.” Planning Perspectives 27, no. 3 (2012): 457–462. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2012.686576

- Carmona, Matthew, Claudio De Magalhaes, and Lucy Natarajan. Design Governance the CABE Experiment. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Cerra, Joshua F., Brook Weld Muller, and Robert F. Young. “A Transformative Outlook on the Twenty-First Century City: Patrick Geddes’ Outlook Tower Revisited.” Landscape and Urban Planning 166 (2017): 90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.05.015

- Clifford, Ben, and Mark Tewdwr-Jones. The Collaborating Planner? Practitioners in the Neoliberal Age. Bristol: Policy Press, 2013.

- Corburn, Jason. “Bringing Local Knowledge into Environmental Decision Making: Improving Urban Planning for Communities at Risk.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 22, no. 4 (2003): 420–433. doi: 10.1177/0739456X03022004008

- Daffara, Phillip. “Rethinking Tomorrow’s Cities: Emerging Issues on City Foresight.” Futures 43, no. 7 (2011): 680–689. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2011.05.009

- Evening Chronicle. “2,300 Visit Newcastle City of the Future Exhibition.” The Evening Chronicle, June 11, 2014. Accessed May 27, 2018. http://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/local-news/2300-visit-newcastle-city-future-7250203.

- Fan, Peilei. “Producing and Consuming Urban Planning Exhibition Halls in Contemporary China.” Urban Studies 52, no. 15 (2014): 2890–2905. doi: 10.1177/0042098014536627

- Farrell, Terry. “London Calling.” Architectural Review 222, no. 1327 (2007): 44–47.

- Farrell, Terry. “There is Only One Thing Worse for Urban Design Than a Recession, and That is a Boom.” Journal of Urban Design 22, no. 2 (2017): 137–139. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2017.1288871

- Farrell Review. Our Future in Place: The Farrell Review of Architecture and the Built Environment. London: Farrells, 2014.

- Ferretti, Federico. “Situated Knowledge and Visual Education: Patrick Geddes and Reclus’s Geography (1886–1932).” Journal of Geography 116, no. 1 (2017): 3–19. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2016.1204347

- Freestone, Robert. “The Exhibition as a Lens for Planning History.” Planning Perspectives 30, no. 3 (2015): 433–446. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2014.1002105

- Freestone, Robert. “Futures Thinking in Planning Education and Research.” Journal of Education in Built Environment 7, no. 1 (2012): 8–38. doi: 10.11120/jebe.2012.07010008

- Freestone, Robert, and Marco Amati, eds. Exhibitions and the Development of Modern Planning Culture. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014.

- Fung, Archon. “Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance.” Public Administration Review 66, no. s1 (2006): 66–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00667.x

- Geddes, Patrick. “Beginnings of a Survey of Edinburgh.” Scottish Geographical Magazine 35, no. 8 (1919): 281–298. doi: 10.1080/00369225.1919.10749978

- Geddes, Patrick. Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and the Study of Civics. London: Williams & Norgate, 1915.

- Geddes, Arthur. “An ‘Outlook Tower’ at Domme, Dordogne.” Geography 36, no. 2 (1951): 127–128.

- Geddes, Patrick. “A Suggested Plan for a Civic Museum and Its Associated Studies.” Sociological Papers 3 (1906): 197–240.

- Geddes, Patrick, and F. C. Mears. Cities and Town Planning Exhibition: Guide-Book and Outline Catalogue. Dublin: Browne and Nolan, 1911.

- Gold, John R., and Stephen V. Ward. “Of Plans and Planners: Documentary Film and the Challenge of the Urban Future, 1935–52.” In The Cinematic City, edited by David B. Clarke, 59–82. London: Routledge, 1997.

- Hall, Peter. Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880. 4th ed. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2014.

- Hay, Colin. Why We Hate Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007.

- Healey, Patsy. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

- Healey, Patsy. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies: Towards a new Relational Planning for our Times. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Henderson, Tony. “How Will Newcastle Look in 2065? New Exhibition Looks at How the City’s Past Will Shape Its Future: Tony Henderson Reports on a Venture Which Will Draw on Newcastle’s Past and Look to Decades Ahead.” The Journal, May 2, 2014. Accessed May 27, 2018. http://www.thejournal.co.uk/news/how-newcastle-look-2065-new-7064676.

- Henderson, Tony. “2,300 Visit Newcastle City of the Future Exhibition: Newcastle City Futures Exhibition at the Guildhall in Newcastle Explored Newcastle and Gateshead Have Altered Since 1945.” The Journal, June 10, 2014. Accessed May 27, 2018. http://www.thejournal.co.uk/news/north-east-news/2300-visit-newcastle-city-future-7246186.

- Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean. Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. London: Routledge, 1992.

- Inch, Andy. “Ordinary Citizens and the Political Cultures of Planning: In Search of the Subject of a new Democratic Ethos.” Planning Theory 14, no. 4 (2015): 404–424. doi: 10.1177/1473095214536172

- Jarron, Matthew. “Patrick Geddes and Museum Ideas in Dundee and Beyond.” Museum Management and Curatorship 21, no. 2 (2006): 88–94. doi: 10.1080/09647770600202102

- Karp, Ivan, and Steven D. Lavine. Exhibiting Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute, 1991.

- Larkham, Peter J., and Keith D. Lilley. “Exhibiting the City: Planning Ideas and Public Involvement in Wartime and Early Post-war Britain.” Town Planning Review 83, no. 6 (2012): 647–668. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2012.41

- MacDonald, Susan, ed. The Politics of Display: Museums, Science, Culture. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Meller, Helen. Patrick Geddes: Social Evolutionist and City Planner. London: Routledge, 1990.

- Pendlebury, John. “Alas Smith and Burns? Conservation in Newcastle upon Tyne City Centre 1959–68.” Planning Perspectives 16, no. 1 (2001): 115–141. doi: 10.1080/02665430010018239

- Place Alliance. “Urban Rooms.” 2016. Accessed September 11, 2016. http://placealliance.org.uk/working-groups/urban-rooms/.

- Ponte, Allesandra, and Jessica Levine. “Building the Stair Spiral of Evolution: The Index Museum of Sir Patrick Geddes.” Assemblage 10 (1989): 46–64. doi: 10.2307/3171142

- Ratcliffe, John, and Ela Krawczyk. “Imagineering City Futures: The use of Prospective Through Scenarios in Urban Planning.” Futures 43, no. 7 (2011): 642–653. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2011.05.005

- Simon, Nina. “The Participatory Museum.” 2010. Accessed August 8, 2017. http://www.participatorymuseum.org/chapter5/

- Söderström, Ola, Till Paasche, and Francisco Klauser. “Smart Cities as Corporate Storytelling.” City 18, no. 3 (2014): 307–320. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2014.906716

- Sookhoo, Dhruv Adam, Mark Tewdwr-Jones, and Catherine Houston. An Urban Room for Tyneside: an Undergraduate Design Response to the Farrell Review’s Call for Every City to Have an Urban Room. Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle Institute for Social Renewal, Newcastle University, 2015.

- Sutherland, Douglas. “Education as an Agent of Social Evolution: The Educational Projects of Patrick Geddes in Late-Victorian Scotland.” History of Education 38, no. 3 (2009): 349–365. doi: 10.1080/00467600902838120

- Tewdwr-Jones, Mark. Spatial Planning and Governance: Understanding UK Planning. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Tewdwr-Jones, Mark. Urban Reflections: Narratives of Place, Planning and Change. Bristol: Policy Press, 2011.

- Tewdwr-Jones, Mark, and John Goddard. “A Future for Cities? Building New Methodologies and Systems for Urban Foresight.” Town Planning Review 85, no. 6 (2014): 773–794. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2014.46

- Tewdwr-Jones, Mark, and Huw Thomas. “Collaborative Action in Local Plan-Making: Planners’ Perceptions of ‘Planning Through Debate’.” Environment and Planning B 25, no. 1 (1998): 127–144. doi: 10.1068/b250127

- Thomas, John L. “Coping with the Past: Patrick Geddes, Lewis Mumford and the Regional Museum.” Environment and History 3, no. 1 (1997): 97–116. doi: 10.3197/096734097779556006

- Tyrwhitt, Jacqueline. “Introduction.” In Cities in Evolution, edited by Patrick Geddes, ix–xxviii. London: Williams and Norgate, new and revised edition, 1949.

- Welter, Volker. Biopolis: Patrick Geddes and the City of Life. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002.

- Welter, Volker M. Collecting Cities: Images From Patrick Geddes’ Cities and Town Planning Exhibition. Glasgow: Collins Gallery, 1999.

- Zueblin, Charles. “The World’s First Sociological Laboratory.” American Journal of Sociology 4, no. 5 (1899): 577–592. doi: 10.1086/210832