ABSTRACT

Architecture and planning projects dominated Finnish-Tanzanian development cooperation in the 1970s. While few previous connections between Finland and sub-Saharan Africa existed, the adoption of international aid operations in Finnish foreign policy provided a pathway for architects and planners to partake in the nation-building endeavours of socialist Tanzania. Through archival analysis, this paper provides a comprehensive perspective into how a Finnish development cooperation agency and development employees (architects included) worked for the benefit of the implementation of Tanzanian socialist policy and aimed to advance regional development as well as to serve the purposes of ujamaa and the authoritarian one-party governance system. The Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan (1975–1978) that followed became the first attempt at large-scale regional planning in Tanzania and attempted to establish regional planning as a solid part of state management. The paper suggests that within the framework of national planning, the difference between a development cooperation project and a planning project is obscure, and it demonstrates that basing research on the conceptual likenesses between planning and development can provide fruitful approaches to planning history.

Introduction

The post-independence era in sub-Saharan Africa from the late 1950s onwards and the strengthening of the political significance of international development cooperation operations opened new pathways for architectural co-operations within and outside the African continent. Finnish architects and planners arrived at the scene of nation-building endeavours in sub-Saharan Africa relatively late, an unexplored area of research on the planning history of Scandinavian countries.Footnote1 Amidst the turmoil of the Cold War era, Finland experienced a rapid transformation from a net receiver of foreign aid to a net donor of aid. While declining Marshall Plan aid from the US, the ambivalent position of Finland between the Eastern and Western spheres of political influence allowed it to accept reconstruction funding from the World Bank, among others, and only do away with developing country status in 1967.Footnote2 Consistently, Finland was one of the last Western countries to experience urbanization and industrialization. Before the first joint Scandinavian project in Tanzania in 1962, most Finnish experiences in Africa took place within the framework of missionary work in what is known today as Namibia. Finnish development cooperation was motivated by the will to join the arenas of international politics surrounding development cooperation and become a nation among nations. Socialist Tanzania held a special place within Finnish development cooperation relations until the late 1980s,Footnote3 and therefore, it represents the main stage of Finnish planning history in the so-called developing countries. During the 1970s, these two non-aligned countries joined forces in building a socialist nation following the guidelines set by Tanzanian ujamaa policy.

A comprehensive look into the cooperation that followed reveals that in addition to the arranging of infrastructural, industrial and social projects, town planning and regional planning constituted a core component in aligning development cooperation with Tanzanian national development objectives. This article combines quantitative and qualitative methods to collect data from Finnish development cooperation yearbooks from 1972 to 1980 in order to provide a comprehensive description of Finnish-Tanzanian planning collaboration. In addition, its uses archival methods to sharpen the results gained from the yearbooks. By introducing a sample of planning projects implemented in the intersection of development cooperation and Tanzanian national planning objectives, the paper discusses the mutual entanglement of the ideas of development and national planning. The paper suggests that the fields of planning and development mutually rely on the modernist belief that social realities can be defined, affected and altered through carefully administered, reasonable, expert-led interventions. In development studies, researchers have been expressing serious concerns about this approach to development cooperation for several decades, allowing for new approaches that stress participation, empowerment and ownership. This criticism is important to keep in mind when studying planning history within the framework of development cooperation.

Undertaking the process of rethinking post-war planning history, a need indicated by Rosemary Wakeman (2014), requires a closer look at the structures of development cooperation and technical assistance that ‘diffused Western planning processes and practices’ and ‘co-produced modern spatiality’ across the globe.Footnote4 Growing interest in international planning networks within the framework of development cooperation has emerged in recent years,Footnote5 and some previous research has placed programmatic development cooperation and the influence of national aid policies in the Global South at the centre of their studies.Footnote6 However, the contributions made by Finnish policies, planners and development cooperation workers in this field of research has remained unexplored until now. By evaluating planning collaboration within a framework in which the International Development Agency (Finnida), as the Department for Development Cooperation within the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs (MFA) was called at the time, served as the main counterpart to the Tanzanian authorities, this article contributes to scholarship on how national development policies have influenced planning in post-colonial Africa. The article shows that during the 1970s, planning and construction projects accounted for the majority of Finnish development cooperation projects. The article makes use of the relative paucity of Finnish-Tanzanian planning projects in order to analyse them as a whole, but it complements this analysis with a close reading of certain select projects. Through extensive research into historical archival sources, this article aims to answer the following questions: How did Finnish development cooperation projects contribute to the establishment of the Tanzanian planning system in the post-independence era? How did the frameworks and ideas of development cooperation affect this relationship? Finally, in what ways was Finnish planning connected with Tanzanian state development objectives? Finnida had the leading role in making possible the presence of Finnish planning professionals in the Tanzanian planning system. Especially the ‘country programs’, e.g. the strategic negotiations surrounding Finnish-Tanzanian development cooperation in general, had a significant role in setting the guidelines for planning cooperation, thus creating a demand for planning professionals to enter the aid industry in growing numbers.

Planning and development as pathways to futures of nation space

Although some scholars trace the origins of development thought to the era of Enlightenment and the economic thinking of Adam Smith (1723–1790), the development movement gained momentum during the era immediately following the end of the Second World War in 1945. The model of technical and economic assistance was first harnessed for the reconstruction of Europe through the Marshall Plan and calming of the independence turmoil within existing colonies. Along with the changes in the political climate embodied in Truman’s Point Four Program (1949), aid operations were extended outside of Europe and became an instrument of influence during the Cold War. The decades of development that followed saw a shifting emphasis from William Rostow’s (1960) ‘stages of economic growth’ theory to modernization theory, to poverty alleviation, to the basic needs approach, and finally, to gender and environmentalism.Footnote7 According to Juhani Koponen’s research on the history of Finnish development cooperation, the ‘idea of the feasibility and desirability of a well-meaning, rationalistically constructed development intervention as the major means to produce social processes ideologically understood as “development”’ has endured through the paradigm changes’.Footnote8

Modernization theory has been especially influential in the development paradigm since the 1950s, and it remained the leading development theory in Finnish development cooperation throughout the 1960s and 1970s. While Third World countries such as non-aligned Tanzania became competing zones of influence for the global superpowers during the global Cold War era – a situation often taken advantage of by the receivers of aid – both East and the West shared an interest in infrastructure and industry as the road to modernization. A case in point is the Uhuru Corridor, an economic zone in Tanzania that simultaneously saw the building of a railroad with the help of the Chinese and a freeway network with the help of Americans in the early 1970s.Footnote9 The railway project triggered a Finnish technical assistance project in the railway area a few years later called the Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan 1975–1978 (explained in more detail below).

Paradoxically, the technological solutions implied by modernization theory reduced what were often political questions to matters of technical knowhow, resulting in the conception of development as the ‘anti-politics machine’.Footnote10 The label of cultural insensitivity more recently applied to many aid operations informed by modernization theory has recently been analysed through the dichotomy of import/exportFootnote11 and raised the issue of whether overly simplistic notions of centre and periphery should be completely abandoned.Footnote12 Critical voices have noted that development cooperation is actually a core reason for, instead of solution to, the problems experienced within the Global South.Footnote13

While acknowledging such a critical approach, this paper seeks to delve into the reasoning behind the trend that characterized Finnish-Tanzanian development cooperation in the 1970s. A crucial theoretical framework can be found in the way Arturo Escobar (1992) discusses development planning:

Planning techniques and practices have been central to development since its inception. As the application of scientific and technical knowledge to the public domain, planning lent legitimacy to, and fueled hopes about, the development enterprise. Generally speaking, the concept of planning embodies the belief that social change can be engineered and directed, produced at will.Footnote14

Development cooperation as an enabler and disabler of planning collaboration

Tanzanian political climate, ujamaa and regional policy

During the post-World War II era, the bulk of regional and holistic planning was directed by state intervention.Footnote16 The planning spree that took place in many parts of Africa after independence has been interpreted quite literally as ‘building the nation’.Footnote17 Tanzania became independent from British rule in 1961. The initial emphasis placed on industrialization as the instrument of development during the period 1961–1967 took a dramatic turn with the Arusha Declaration of 1967. For a decade thereafter, Tanzanian policy focused on rural development, rural socialism (ujamaa) and the promotion of social equality instead of rapid economic growth.Footnote18 These policy changes culminated in the concept of the ujamaa village.Footnote19 Ujamaa policy led to an extensive resettlement plan that has been called one of the most ‘significant “alternative visions” of urbanism and human settlement that has emerged from postcolonial Africa’.Footnote20 The radical rural policy resulted in the registration of thousands of new ujamaa villages within the next decade (1967–1976) and the implementation of the largest mass villagization programme on the continent before or since, one that affected roughly 13 million people.Footnote21

What started as ideological policy implementation in 1967–1972 became an endeavour to implement a rational economic policy in 1972–1976.Footnote22 In 1973, villagization became mandatory for all citizens (Operation Vijiji). This change in policy has been traced back to the trade deficit of 1970, to the poor harvest of 1972 (necessitating food imports on an unprecedented level) and to the global doubling of oil prices between 1969 and 1973.Footnote23 The 1972 decentralization policy that followed was the culmination of the administrative transition during the previous years. The political changes of 1972 and 1973 were enacted as extensions of state control over rural areas and led to the replacing of locally elected leaders with representatives of the ruling party (TANU). As Jennings summarizes: ‘The Ujamaa village policy had culminated not in the establishment of a nation run on socialist and democratic lines, but in a society based on rigid control from an authoritarian centralized regime.’Footnote24 Maintaining the ujamaa rhetoric, however, was enough to secure the willingness of development cooperation agencies and organizations to participate in ‘the effort to extend government authority in the rural sector, believing they were participating in a program of rural development’.Footnote25

Nonetheless, the Arusha Declaration became the greatest hope of the global liberal left in its pursuit of finding alternatives to both the capitalist policies of the West and the industrial communism of the Soviet bloc.Footnote26 Regardless of the socialist underpinnings of ujamaa policy, Western countries were the main providers of aid in continental Tanzania. Zanzibar in contrast sought partnerships with Eastern Bloc countries. Small-scale aid donors were sometimes assisted by international agencies such as the United Nations.Footnote27

TANU believed that industrial and infrastructural development in rural areas would discourage migration to cities and therefore advance the aspirations for rural development. Although infrastructural and industrial development were crucial parts of developmental thinking both in TANU’s official policies and in the international development paradigm in general, Nyerere wrote that it is dangerous to rely on them too much. Tanzania did not have the means, funds or skills to develop those sectors independently. In his essay The Arusha Declaration Ten Years After (1977), Nyerere commented on the pursuit of modernization at all costs, saying that it had led to ‘large capital-intensive factories when a number of small labour-intensive plants could have given the same service at lower financial cost and with less use of external technical expertise’.Footnote28

Tanzania’s ambitious regional reform and decentralization programme created a need for foreign professionals’ output and technical assistance from foreign donors becoming a central part of Tanzania’s planning objectives. The University of Dar es Salaam only produced its first engineering graduates in the mid-1970s.Footnote29 With the commencing of bilateral development cooperation, Finland directed increasing funds towards Tanzanian development from the early 1970s onwards. Measured in terms of allocated funds, Tanzania was the largest receiver of Finnish development cooperation funding between 1970 and 1985, with Finland providing almost one-third of its total official development assistance (ODA) to Tanzania during this time.Footnote30

Nevertheless, the year 1985 saw the demise of the ujamaa programme and the villagization utopia. The failing of ujamaa was affected by, among other things, financial issues stemming from the Ugandan War in 1978–1979, the breakup of the trade-oriented East African Community in 1977 and the global oil crises. In the early 1980s, international financial organizations like the World Bank put pressure on Tanzania to execute a structural adjustment programme, which meant the degradation of socialist principles.

Finnish development cooperation policy

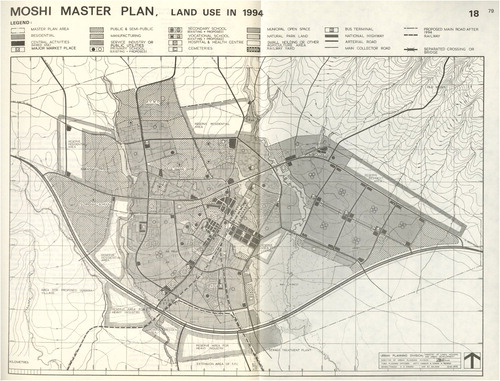

Lauri Siitonen (2005) divides the history of Finnish development cooperation into three major phases. It began with the formative phase (1961–1973), which he also calls the Scandinavian phase due to the cooperation of the Scandinavian countries in joint projects. During the era of Scandinavian cooperation, three joint projects were implemented in Tanzania (see ). Tanzanian officials had had their first experiences with Finnish collaboration in 1962 with the launching of the Scandinavian co-operation project known as the Kibaha Education Centre.Footnote31 A department of international development cooperation was founded within the MFA in 1972. During the second phase of institution and policy building (1974–1991), the imperative of Finnish aid was embedded in the official non-aligned policy. The third and final phase of development cooperation policy (1992–2000) gave rise to some major changes in aid policy away from modernization and more to empowering themes such as gender and the environment. The political framework for Finnish development cooperation circulated within the sphere of Cold War politics and the Scandinavian model. Siitonen argues that during the early years of Finnish development cooperation, the primary motive for partaking in the aid industry was the building of a Western identity rather than development cooperation per se. This was not, however, articulated in the official justification of development cooperation and ‘developmentalism’. The aim of being categorized as a Scandinavian country resulted in imitation of principally Swedish but also Norwegian and Danish development cooperation policies and the adoption of Tanzania as the principle recipient of aid during the 1970s. Multilateral development cooperation projects had another useful function. They relieved the Finnish development agency from full responsibility concerning decisions on development cooperation policy during the heated Cold War years. The 1970s development cooperation policy reflected the idealized identity of a Nordic, non-aligned country balancing between the East and West.Footnote32 Finnish development cooperation policy followed guidelines set by international development organizations and fellow donor nations, and in that sense it was not a thoroughly ‘Finnish’ aid policy.

Table 1. Architecture, construction and planning projects as part of Finnish-Tanzanian development cooperation, 1962–1988.

The Finnish contribution to international development cooperation was marginal when compared to countries from Western Europe or Scandinavia. In several sub-sectors of development, Finnish development cooperation built on the expertise of development aid professionals working for Finnida, consultants working in Finnish companies or volunteers sent to developing countries through church-related organizations or NGOs. A study on Finns involved in development cooperation from 1966 to 1995 shows that the number of Finns engaged in bilateral development cooperation grew from 140 in 1972 to 221 in 1981, and started to diminish after 1982 partly due to changes in development policies that emphasized the agency of local people instead of foreign professionals.Footnote33 The number of personnel in architecture and planning increased from 11 experts in 1972 to 16 in 1975, the third largest sub-sector of development cooperation during this time period and only outweighed by the sub-sectors of ‘technology’ and ‘consumer cooperatives’. In 1976, the emphasis placed on architecture and planning gave way also to greater numbers of persons involved in ‘business economics’ and ‘higher education’.Footnote34 This data suggests that architecture and planning held a solid place at the core of Finnish development cooperation practices during the course of the 1970s while reflecting changes in development cooperation policy.

Along with architects and planners, the transnational mobility of Finnish construction companies and workers accelerated in the 1970s. Laakso and Tamminen (2014) have called this era the golden era of Finnish construction export.Footnote35 The volume of construction export grew more intense during the late 1960s and early 1970s as a result of growing interest by engineering and architecture companies in the business potential of the Global South.Footnote36 According to Hakkarainen et al., ‘in the 1960s and 1970s there was a strong belief in the possibility of social planning, and the key people were engineers and statisticians who analysed development quantitatively’.Footnote37 The development policy’s course of conduct in 1974 defined four major fields in Finnish aid: forestry, water, the mining industry and construction.Footnote38 Planning was a central concept in not just Finnish but also Nordic-Tanzanian cooperation in the late 1960s and in the 1970s, from whence Finnish architects and planners drew inspiration.Footnote39

Some of the bravest young planners were attracted to the challenge of doing what Swedish, Norwegian and Danish planners had already started: planning development cooperation projects in ‘underdeveloped’ Africa. What perhaps distinguished Finnish professional development planners from their Nordic – or British – colleagues was the fact that many Finns still had living memories of poverty, for example during the World War. Footnote40

Nevertheless, a certain amount of research concerning the colonial past of the Nordic countries provides a challenging viewpoint. Vuolajärvi points out the role of colonial complicity by examining global trade networks as an example of the ways in which Finland was on the receiving end of the imperial world order.Footnote48 Koponen respectively challenges the conception of ‘ideological love’ as a meaningful factor within the forging of Finnish-Tanzanian relations. He argues that Tanzanian political stability, among other factors, was more valuable a base for development cooperation than any shared interest in socialism.Footnote49 Koponen states, however, that the country selection process was a politicized debate that was interlinked with Finnish domestic policy.Footnote50

Following the commencement of the institution and policy building phase (1974–1991) in Finnish development cooperation policy, Finnida and the Tanzanian government created the first country programme to direct the alignments of cooperation in 1975.Footnote51 The country programme was a forum for development cooperation negotiations between Finland and Tanzania, and it was based on the development plans and aspirations of the aid receiving country.Footnote52 The strategic nature of country programme negotiations highlights the role of public servants in planning. The negotiations offer a clear example of the power of the bureaucrat in the shaping of the African built environment. During the 1970s, Finnish development cooperation was still under the influence of modernization theory. The so-called ‘hard’ engineering projects in areas such as infrastructure and industry formed a significant part of Finnish-Tanzanian development cooperation in the 1970s and 1980s.Footnote53 By approaching Finnish-Tanzanian planning collaboration as a unified entity, as the result of official negotiations and the collision of political ideologies with ideas about planning and development, it is possible to sketch the underlying ideas about progress, governance and social order as well as future aspirations that would soon follow.

Simultaneously with the collapse of the ujamaa policy and the structural adjustments required by the World Bank and the IMF in the 1980s, Finnish development cooperation policy saw a shift towards the themes of gender and the environment, meaning that the modernizing approach to development through infrastructural and industrial projects gradually started to lose its position at the core of Finnish development cooperation policy and led to the decreasing of the number of planning projects. This also meant the reorganization of architectural networks in developing countries.

Rise and descent of Finnish-Tanzanian planning collaboration: a quantitative analysis

The compilation of Finnish-Tanzanian planning collaboration can be read as the result of a negotiation between Finnish development cooperation policy and Tanzanian domestic development objectives. Both were affected by the larger framework on internationally influential development cooperation policies and organizations. displays a compilation of Finnish-Tanzanian cooperation projects in architecture and planning between the years 1962 and 1988. It draws from the Finnish development cooperation yearbooks for the years 1972–1980, published by Finnida, but it is complemented by results from archival work at the MFA. The first yearbook was published in 1972. After 1980, the way in which data was presented changed. The yearbooks include information about Finnish development cooperation in general, statistics, descriptions of the aid-receiving countries and cooperation projects. In addition, they discussed the more important policies in Finland and abroad that guided the development of aid policy. The early decades of Finnish development cooperation were not documented as thoroughly as they are today. The yearbooks only provided information about what Finnida considered the ‘most important’ projects, but they are nevertheless the only available record of the development cooperation projects before more advanced data management practices. In 1984, the MFA started collecting data on ‘basic statistics of Finnish development cooperation’, which it then published yearly. No official listings of development cooperation projects are available between 1981 and 1983. reveals that 27 planning projects were implemented between 1962 and 1988, out of which 22 commenced in the 1970s. The year 1972 appears as a peak in the statistics, with 15 projects being launched that year. An interest in urban and regional planning predominated between the years 1972 and 1988. The 1970s and early 1980s have been titled the ‘golden era’ of Finnish construction export by Laakso and Tamminen (2014), which the findings presented in this paper support.Footnote54 Raimo Määttä’s seminar paper (1979) on Finnish construction export within the framework of development cooperation proposes parallel results, although with a methodology that makes his results somewhat disproportionate in comparison with the results presented here (see ).Footnote55

Table 2. Number of Finnish professionals in construction business working in bilateral development cooperation in Tanzania, 1970–1978, depicted both in terms of number of persons (above) and labour input in working months (below).

Whether an individual project is or is not included in is based on descriptive information provided in the yearbooks and archival material as well as an estimation of whether or not the project resulted in planning or construction practices. The results include some industrial and infrastructural projects as well as plans for health centres, schools and other educational facilities. Considering the nature of development cooperation, wherein projects can change or be discontinued in the middle of implementation, this listing should not be taken as a solid collection of suitable projects, but as a rough description of the field.

indicates that planning and construction projects cover approximately half of all development projects implemented in Tanzania in 1972–1980, reaching a peak in 1975. It compares the number of ongoing planning and construction projects against all bilateral projects mentioned in the yearbooks, regardless of statistical sector, between Finland and Tanzania on a year-by-year basis, excluding projects with a focus on professional training. is compiled based on yearbooks alone in order to provide a basis for comparison. The total number jumps from eight to 14 projects per year.

Table 3. This table compares the number of all Finnish-Tanzanian bilateral development cooperation projects with the proportion of architecture and planning projects quantified by year, following the categorization system in the Finnish development cooperation yearbooks.

provides another viewpoint to the compilation depicted in , but it presents the data in a way that highlights the years from 1972 to 1974 as a significant peak in cooperation efforts. It brings forth the peak’s correlation with and dependency on historical events, most clearly those within the spheres of Finnish cooperation policy and Tanzanian domestic issues discussed above. The Tanzanian need for technical assistance in planning grew stronger together with the decentralization programme of 1972 as well as its repercussions, and it coincided with the organization of Finnida and the commencing of Finnish bilateral development cooperation in 1971, most of which was targeted at Tanzania. The descending curve for projects launched in the early 1980s illustrates changes in development thinking, its shifting points of focus and the growing criticism of modernization theory.

Table 4. Number of ongoing planning projects per each year implemented as part of Finnish-Tanzanian development cooperation in 1962–1988 following the categorization system in .

The process of categorization demonstrated above raises many issues regarding the subtle overlapping nature of the histories of development cooperation and planning. Fields such as infrastructure and industry are inseparable from planning (and often from development issues as well). They do not, however, necessarily contain the work of architects per se, but are implemented by engineers, technicians and other professionals. The expansion of the field of architecture towards the fields of finance, demographics and community development and the emergence of a need for a new type of expert in both development and planning in decolonizing nations, erases the possibility of any clear categorization between the two fields. The compilation of Finnish-Tanzanian planning collaboration efforts demonstrates what Arturo Escobar referred to as the inextricably linked nature of planning and development.Footnote56 It is necessary to recognize, therefore, that crafting a comprehensive listing, such as the one at hand, requires the drawing of artificial boundaries and definitions that cannot always account for the volatility of the relationship between development and planning. Nonetheless, this paper suggests that recognizing this volatility itself opens a path to future reflections and research.

Stages of cooperation: master planning, regional integrated development planning and regional physical planning

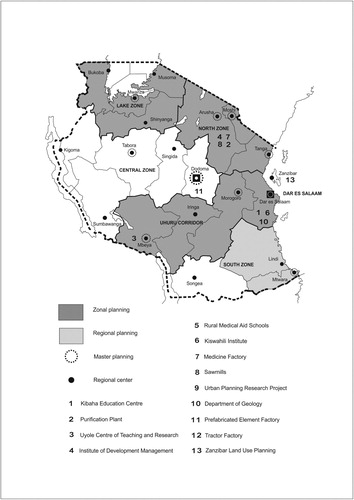

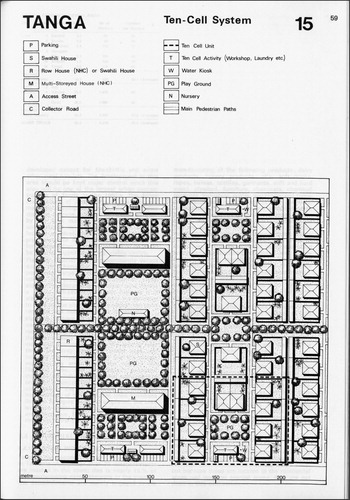

Growth-Pole strategy: Tanga, Mbeya, Moshi and Tabora master plans (1972–1974)

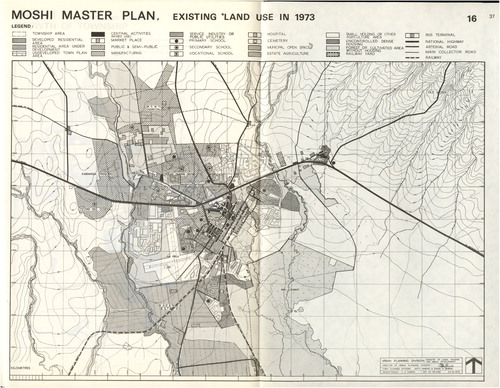

The year 1971 marked the starting point to a decade of continuous Finnish planning co-operation projects in Tanzania. In 1971, the MFA commissioned architect Jaakko Kaikkonen to investigate the potential to contribute towards Tanzanian planning objectives. Kaikkonen undertook a study trip to Tanzania, after which, based on his recommendations, a team of Finnish architects were recruited to the service of MFA and sent to Tanzania. This team included the architects Antti Hankkio, Rainer Nordberg, Mårten Bondenstam and Bo Mallander as well as an engineer and a researcher. Their recruitment stemmed from the Tanzanian government’s attempt at implementing a growth-pole strategy as a part of the process of creating a national framework for regional decision-making.Footnote57 The growth-pole strategy followed the ujamaa vision of directing future industrial investments away from Dar es Salaam.Footnote58 Aligned with the regional reform and the nation-building endeavour, the capital city status was transferred from Dar es Salaam to Dodoma in 1974 so that the capital would be more accessible and centrally located.Footnote59 In 1972, the team started to work on four master plans in the towns of Tanga, Mbeya, Moshi and Tabora ( and ). Nine master plans had been intended, but only four were enacted. These master plans were an attempt to reduce migration into cities that in recent years had reached an annual growth average of 6 per cent. Especially the exponential population growth in Dar es Salaam had raised concerns among Tanzanian officials. To reduce the social problems and squatter areas growing on city borders, Tanzanian officials founded the Sites and Services Program. The fifth member of the team of Finnish architects, Kyösti Venermo – joined later by architect Outi Berghäll – worked within the Housing Division of the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development (Ardhi).Footnote60 Venermo worked as a lecturer at the Ardhi Institute in Dar es Salaam from 1972 to 1976.Footnote61 The Sites and Services Program aimed at defining proper areas suitable for residential settlement and providing them with municipal infrastructure. Houses were to be built by the residents themselves.Footnote62

Rural development: Mtwara and Lindi regional integrated development plans (1974–1975)

In 1972, the Tanzanian decentralization policy directed the interests of the planning bureaucracy into regional planning, with specific interest on comprehensive economic development of rural areas (). The so-called Integrated Regional Development Programs (IRDPs) that were being implemented around the world at the time were known in Tanzania as Regional Integrated Development Plans (RIDEPs). Previous attempts at institutionalizing regional planning had not been successful ‘due to low levels of participation, administrative capacity, and finance’.Footnote63 According to a critical inquiry by Idzz Kleemeier, without solving these issues Tanzania’s capacity to make use of foreign investment capital would be extremely low.Footnote64 The consulting companies Finnplanco and Finnconsult undertook the task of planning projects for the remote regions of Mtwara and Lindi in southern Tanzania in 1974 and 1975. Finnplanco and Finnconsult coordinated their work closely with Finnida and the Finnish embassy in Tanzania. RIDEPs were expected to provide an extension to Tanzania’s Second Five Year Plan and focused on integrating such economic sectors as agriculture, fisheries, forestry and mining on a regional scale.Footnote65

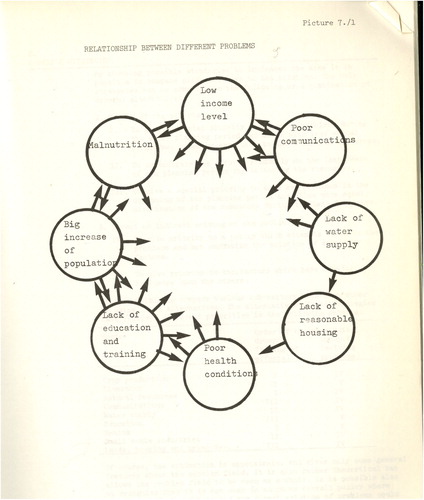

Figure 3. Relationship between Different Problems. Source: Lindi Regional Integrated Development Plan 1975.

RIDEPs were the first attempt at regional planning, even if not a very successful one.Footnote66 One major issue with them concerned their lack of attention to physical planning. Following the guidelines set by Tanzania’s ujamaa policy, they prioritized rural development and paid little attention to the already-existing problems in urban areas. In August 1974, Jaakko Kaikkonen sent a preliminary programme outline to Finnida, suggesting that they implement a pilot project as part of Tanzania’s regional physical planning efforts. What separated such plans from RIDEPs was that the planning area consisted of a large economic ‘zone’ that normally included three to four regions. This was the first time that a plan of this scale was implemented in Tanzania. The Finnish pilot project was expected to become a model for extending regional physical planning throughout the whole country and proceeding towards holistic national planning.Footnote67

shows that Finnish technical assistance projects in Tanzania were widely spread throughout the country. There were three stages of planning during the period of cooperation, all of which gained their original motivation from the nation-building endeavours of the Tanzanian government. Starting from the master planning stage, the scope shifted to regional planning and further to zonal planning, meaning that the ambitiousness as well as the geographical sphere grew from stage to stage. Following the thoughts of Idzz Kleemeier, being planned means being governed.Footnote68 Developing rural areas was one of the main goals of ujamaa policy, but critics such as Kleemeier saw it as a centralization of state power and extending state power to rural hinterlands at the expense of local socio-cultural organization. Reaching the population was vital to the nation-building process of the ujamaa policy, although the attempt lead to what Hydén calls an uncaptured peasantry.Footnote69 Nation building entails the shared imagery of a unified nation,Footnote70 and a built environment is not incapable of carrying such imagery.Footnote71 With respect to the built environment, imageries of national futures especially carry specific significance. As displayed in , the contribution of Finnish technical assistance partook in the spreading of national imageries across both geographical and conceptual distances.

From neighbourhood unit to national planning: Uhuru Corridor (1975–1978) and Lake Zone (1978–1981) regional physical plans

The Uhuru Corridor is an economic zone in Tanzania that gained political significance within the intersecting frameworks of the Cold War and the heritage of colonialism. The Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan was implemented with the help of Finnish technical assistance between 1975 and 1978. A few years earlier Chinese engineers had contributed to the construction of the Tazara railway line (1970–1975), which extended all the way from Dar es Salaam to the Tanzanian-Zambian border and was the basis for regional economic development. Simultaneously, the United States was involved in constructing a road network in the same regions. Also known as the ‘Freedom Railway’, Tazara played a role in the Zambian pan-African pursuit of economic liberation. Before the construction of Tazara, Zambia was landlocked by Rhodesia, Angola and South Africa, three states still very much under the control of colonial powers. Tazara enabled the liberation of the Zambian economy via the infrastructural networks of socialist Tanzania.Footnote72 Other reasons for choosing the Uhuru Corridor as the pilot project area included its arable land reserves as well as its remarkable deposits of coal, iron ore and minerals.Footnote73 The Uhuru Corridor consisted of four administrative regions: the Coast Region, Morogoro, Iringa and Mbeya. According to the 1967 population census, 2.9 million people lived in the Uhuru Corridor, or 25 per cent of the country’s population at the time. The population was estimated to be 3.7 million by 1975.Footnote74 The majority of the population had been relocated to ujamaa villages by 1975.Footnote75

Ujamaa ideology steered regional planning in many ways. It identified exponential urbanization as a major issue to be solved by regional planning and, correspondingly, emphasized rural development as the solution. The Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development in Tanzania expected the planning project to contribute to the ‘aspirations of the Tanzanian society: building a socialist and egalitarian nation’.Footnote76 The regional policy objectives fit those of the third five-year plan (1976–1981), including the integration of economic and physical planning. As a response, the Finnish planning team pursued systematization and coherence of planning and also tried to integrate town planning with economic planning.Footnote77 The aim of the Uhuru Corridor regional planning initiative was to create optimal conditions for production, fostering technical, social and economic progress. In addition, regional physical planning was considered fundamental for the ‘rational spatial distribution of settlements’.Footnote78 Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan was supposed to be a pilot project that would eventually direct the zonal planning of all Tanzania.Footnote79

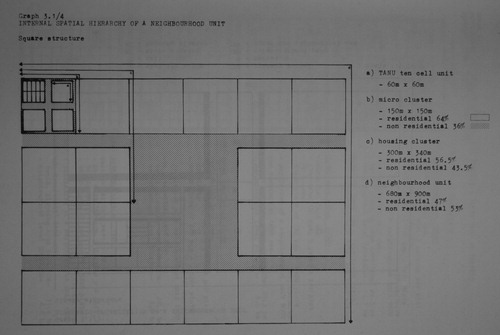

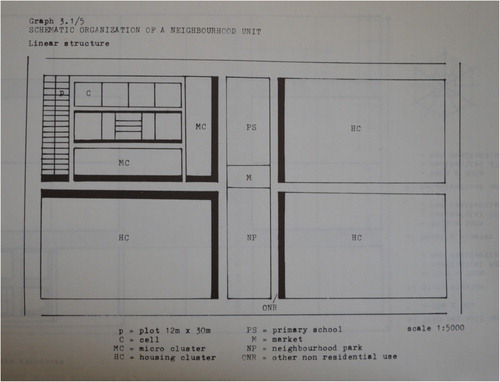

The main contribution of the Finnish planning team was to help even out the gap between Dar es Salaam and rural villages. The project report on urban settlement emphasized the need to create semi-urban settlements consisting of 3000–10,000 people. The main issue, in addition to uncontrolled urbanization, was the lack of commensuration and standardization within the Tanzanian planning system, which was partly due to the intersecting contributions of aid donors.Footnote80 In order to face the issues of uncontrolled urbanization, such as overly dense settlement and a lack of open spaces, the Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan introduced some model neighbourhood units based on the TANU ten cell unit ( and ). The neighbourhood unit is a planning tool from the early 1900s introduced by Clarence Perry and developed by Lewis Mumford and others. The advantage of the neighbourhood unit was its adaptability and reproducibility in contexts of rapid urbanization. It became a part of Finnish architectural education most notably through the efforts of Otto I. Meurman. Finnish technical assistance applied the concept to Tanzanian town planning efforts integrated with TANU’s ten-cell unit system (). According to the TANU cell system, every ten houses formed one cell. The aim of the cell system was to engage the tenants and serve as an instrument of governance and party organization. It was intended to function as a means of communication between the party and villagers and to further national security and consolidate unity among Tanzanians.Footnote81 Therefore, the ten-cell unit was a vital part of extending state power and party organization into the countryside at the village level throughout rural Tanzania. shows the suggested deployment of ten-cell units around a primary school, market and neighbourhood park.Footnote82

Figure 5. Internal Spatial Hierarchy of a Neighbourhood Unit Based on the TANU Ten Cell Unit. Source: Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan 1975–1978. Main Report III Urban Land Use.

Figure 6. Schematic Organization of a Neighbourhood Unit. Source: Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan 1975–1978. Main Report III Urban Land Use.

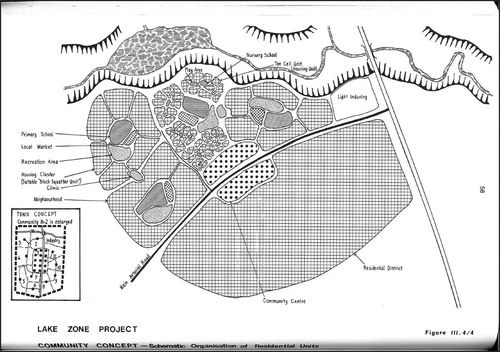

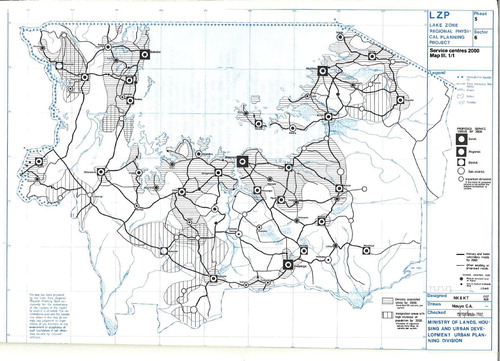

Despite the intention to extend the same regional planning model throughout the country, only one other regional plan was successfully prepared by a Finnish planning team. The Lake Zone Regional Physical Plan (1978–1981) was prepared according to the Uhuru Corridor model, covering the regions of Bukoba, Shinyanga, Mwanza, Musoma and Mara around Lake Victoria.Footnote83 In November 1982, the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development in Tanzania requested the commencing of a new regional physical plan. Nevertheless, the Northern Zone Regional Physical Plan was never realized.Footnote84

The Lake Zone Plan followed the trail set by the Uhuru Corridor Plan. Like the Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan, the Lake Zone Regional Physical Plan was intended to function as the basis for future zoning schemes, town planning and building plans.Footnote85 The project was led by Heikki Tegelman and Ardhi’s E. H. Berege. Compared to the Uhuru Corridor Plan, the Lake Zone Plan put more emphasis on town planning ().Footnote86

Figure 8. Community Concept – Schematic Organisation of Residential Units. Source: Lake Zone Regional Physical Plan, Main Report III: Urban Land Use.

During the 1980s, there was one more attempt at Finnish-Tanzanian planning collaboration. The Zanzibar Integrated Regional Economic Land Use Plan was to focus on the Zanzibar and Pemba islands during the years 1987 and 1988. The Tanzanian counterpart to Finnida was the Ministry of Water, Construction and Energy of Zanzibar, and the aim of the project was to respond to the long-term issues with land use concerning, for example, human settlement and economic development.Footnote87 The long-term perspective plan would consist of a targeted settlement pattern, a regional land use plan and an infrastructural programme. Like the Uhuru Corridor Plan, the Zanzibar Land Use projects would introduce a new physical dimension to present planning practices and would function at the initial stage as a planning and management tool for the Zanzibar planning authorities, a scope ‘which is not to be belittled’.Footnote88 The primary aim of the project was improving the living conditions in all sectors of life and the equity of inhabitants in all population groups.Footnote89 A preliminary project survey was prepared by town planner Raimo Jouhikainen, who had worked on the Uhuru Corridor Plan as a team-leader a decade earlier.Footnote90

According to Jennings, by the time Finnish-Tanzanian development cooperation and most planning projects had commenced in 1972, the ideals of ujamaa had already been transformed into an authoritarian state model based on rigid control of the population.Footnote91 A critical viewpoint offered by Idzz Kleemeier depicts the origins of policy changes in regional planning as an instrument for the central leadership to consolidate centralized state power in four stages. According to him, regional planning arose from the need to suppress popular participation, to channel participation into a controllable mode and to strengthen institutional power:

One has been the abolishment of local organizations which were under community rather than central control, e.g. primary cooperatives and district councils. The Second move has been to expand the role in local affairs of institutions controlled from the center, i.e. a strengthened political party with a single ideology, and a politically submissive bureaucracy charged with planning and implementation of party policy decisions. Third the government has disrupted indigenous social structures through villagization. Fourth the government has promised massive levels of rural social services investment in education, health, and water hoping these benefits will entice the local communities to accept the other changes.Footnote92

Undoubtedly the Uhuru Corridor Plan has substantially contributed to physical planning in Tanzania. It seems to have a clear impact upon those administrative procedures which evidently will establish physical planning as a permanent part of the overall planning system of the country.Footnote94

Not another laboratory?

In some cases, African terrain has been described as a location for experiments in development or as a ‘laboratory’ for European architects and planners to explore new ideas not yet implemented at home.Footnote95 In the Finnish-Tanzanian case, however, this was not necessarily true. On the contrary, contemporary evaluations of the Uhuru Corridor Regional Planning Project found that it had been executed similarly to regional plans in Finland. The latest case in Finnish regional planning had been finished in 1976, only two years before the finalization of the Uhuru Corridor Project. Heikki Ravila further expanded upon the similarities in his evaluation of the project: the population prediction for the Uhuru Corridor (5.393.339) was projected to be similar in 1995 as the Finnish national equivalent in 2000. The Uhuru Corridor zone area (224 000 km²) covers about two thirds of the Finnish state area (338 440 km²). According to Ravila’s analysis, the final outcome of the plan was based on Walter Christaller’s central place theory, which was widely applied in the 1960s (). According to central place theory, communities are divided into hierarchical categories according to the quality and amount of social services available in the region. Tanzanian planning organization at the time was divided into three levels. Regional centres had the most social facilities, whereas district and ward centres were smaller and had fewer social services. The Uhuru Corridor Regional Planning Project allowed for three regional centres, in Morogoro, Mbeya and Iringa. The smallest unit, the ward, would consist of 3–8 (ujamaa) villages and a population of 3000–5000.Footnote96 Similarly, the application of central place theory to the contemporary situation in Finland had reached its peak in 1967. According to Sami Moisio, central place theory made it possible to address nation space as a unified, hierarchical, governable entity, a goal not far from that of the Uhuru Corridor regional plan.Footnote97 The seemingly diverse similarities between Finnish and Tanzania planning trajectories and their possible impact on planning cooperation between the two nations require further research to be fully understood ().

Figure 9. Service Centres 2000. Source: Lake Zone Regional Physical Plan, Main Report III: Urban Land Use.

Kaikkonen’s own account of the potential of the Uhuru Corridor Project provides a differing viewpoint on the laboratory status of the zone. In the professional journal of Finnish architects, Arkkitehti, he noted that the Uhuru Corridor is ‘like a giant laboratory, where the rebirth of rural areas enables the development of synthetic communities – towns and villages – on nearly virgin land’.Footnote98 By synthetic communities, he probably optimistically meant the ujamaa villagization programme, although it never had the chance to be fully realized. Less than a decade later, Tanzanian socialism, and with it the dream of a reborn countryside, was put to rest.

Conclusion

The contemporary understanding of the Uhuru Corridor Plan was that it would play a role in establishing regional physical planning as a permanent part of the Tanzanian planning system. It was a pilot project intended to assist the Tanzanian government’s centralization of political power in remote rural regions. Although the original ambitious objectives were not met, the Uhuru Corridor Project became integrated into the evolution of the Tanzanian regional and town planning system due to its general principles and physical structure proposals. It provided a tool for establishing and strengthening regional control and contributed to socialist nation-building principals and efforts at regional development.

The structures and ideas of international development cooperation enabled the formation of Finnish-Tanzanian planning collaboration. Changes in Finnish development cooperation policy provided a channel for architectural mobilities but also influenced the decreasing of this collaboration. The promotion of architecture and planning was a significant feature of Finnish development cooperation in the 1970s, and for some time planning became an instrument of Finnish foreign policy. Measured in terms of the number of projects, the sub-sector of architecture and planning held a place as one of the major approaches to development in Finnish development cooperation in the 1970s and competed with such profound sectors as forestry. The analysis provided here suggests that Finnida considered architecture and planning to be a Finnish specialty and a valuable export product.

The holistic approach to Finnish-Tanzanian planning cooperation demonstrates the important influence of international development cooperation policy in planning history. This article suggests that within the framework of national planning the difference between a development cooperation project and a planning project is obscure, prompting the need to ask, to what extent can scholars of planning history base their research on the conceptual likenesses between planning and development? Nevertheless, there is a need for supplementary, interdisciplinary conceptual analysis of the nuanced relationship between planning and development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Essi Lamberg

Essi Lamberg is a Doctoral candidate in the Department of Cultures at the University of Helsinki. Her research interests include urban and regional planning in the framework of international development cooperation in post-colonial Africa.

Notes

1 See, however, Laakso and Tamminen, Rakentajat maailmalla; Berre, “Norwegian Expert Export”.

2 Kehitysyhteistyökomitea, Kehitysyhteistyökomitean mietintö 1978, 47–8.

3 Hirvonen, Basic Statistics, 13.

4 Wakeman, “Rethinking Postwar Planning,” 158.

5 Beeckmans, “French Planning”; Phokaides, “Rural Networks”; Avermaete, “Framing the Afropolis”; Ward, “Transnational Planners”; Stanek, “Miastoprojekt Goes Abroad”; Odendaal, Duminy and Inkoom, “Developmentalist Origins.”

6 Stanek, Architecture in Global Socialism; Beeckmans, “Architecture of Nation Building”; De Raedt, “Between ‘true Believers’”, “Policies, People, Projects “; Beyer, “Building Institutions”.

7 Rist, History of Development; Kothari, Radical History; Van Bilzen, Development of Aid.

8 Koponen, Still Afloat, 2.

9 Monson, Africa’s Freedom Railway.

10 Ferguson, Anti-Politics Machine.

11 Nasr and Volait, Urbanism.

12 Stanek, “Architects from Socialist Countries”.

13 Escobar, Encountering Development; Kapoor, Postcolonial Politics.

14 Escobar, “Planning,” 132.

15 Odendaal, Duminy and Inkoom, “Developmentalist Origins,” 285–290.

16 Wakeman, “Rethinking Postwar Planning,” 159.

17 Hess, Art and Architecture; Beeckmans, “Architecture of Nation-building”.

18 Nyerere, Ujamaa.

19 Jennings, Surrogates of the State, 45.

20 Myers, African Cities, 65.

21 Jennings, Surrogates of the State, 48.

22 Havnevik, Limits to Development, 200.

23 Bryceson, “Household, Hoe, and Nation,” 42–44.

24 Jennings, Surrogates of the State, 60.

25 Ibid., 64.

26 Ibid., 37.

27 Ward, “Transnational Planners,” 59–60.

28 Nyerere, Arusha Declaration, 8.

29 Swantz, Transfer of Technology, 142

30 Hirvonen, Basic Statistics, 13.

31 “Suomen ja Tansanian kehitysyhteistyö”, Kehitysyhteistyö 2: (1972).

32 Siitonen, Aid and Identity Policy. See also Koponen, Still Afloat.

33 Leinikki, Finns in Development, 7, 14.

34 Development aid yearbooks 1972–1976.

35 Laakso and Tamminen, Rakentajat maailmalla.

36 Ibid., 24.

37 Hakkarainen, Toikka and Wallgren, Unelmia maailmasta, 79.

38 Koponen, Still Afloat, 21.

39 Seppälä and Koda, Making of a Periphery, 82.

40 Ibid., 82–83.

41 Siitonen, Aid and Identity Policy, 171.

42 Engh and Pharo, “Nordic cooperation,” 115.

43 Cooper, Africa since 1940; Beeckmans, “French Planning,” 59; see also Herz, New Domain, 11–12.

44 Palmberg, “Nordic Colonial Mind,” 36.

45 Soikkanen, Presidentin ministeriö, 406–7.

46 Nyerere, Arusha Declaration, 51. Ward, “Transnational Planners,” 63.

47 Porvali, Evaluation of the Development, iii.

48 Vuolajärvi “Rotu etnisten suhteiden,” 264–301.

49 Koponen, Oma suu ja.

50 Koponen, Some Trends, 17–18.

51 Porvali, Evaluation of the Development, iv.

52 Kehitysyhteistyön vuosikertomus 1978–79, 29.

53 Koponen, Some Trends, 17–18.

54 Laakso and Tamminen, Rakentajat maailmalla, 22.

55 Määttä, “Rakennusalan yritysten vienti,” 29.

56 Escobar, “Planning,” 1.

57 Kaikkonen, “Suomalaista yhdyskuntasuunnittelua”.

58 Kleemeier, “Foreign Assistance,” 12.

59 Hess, Art and Architecture, 114–126; Beeckmans, “Architecture of Nation-building.”

60 Kaikkonen, “Suomalaista yhdyskuntasuunnittelua”.

61 The Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland Archive (MFAA), Kyösti Venermo’s resumé.

62 Kaikkonen, “Suomalaista yhdyskuntasuunnittelua”.

63 Kleemeier, “Foreign Assistance,” 24.

64 Ibid.

65 MFA, Lindi regional integrated development plan 1974–1975; MFA, Mtwara Regional Integrated Development Plan 1975–1980.

66 Kleemeier, “Foreign Assistance”.

67 Kaikkonen, “Suomalaista yhdyskuntasuunnittelua”.

68 Kleemeier, “Foreign Assistance”.

69 Hydén, Beyond Ujamaa.

70 Anderson, Imagined Communities.

71 Beeckmans, “Architecture of Nation-building”.

72 Monson, Africa’s Freedom Railway, 1–3.

73 Kaikkonen, “Suomalaista yhdyskuntasuunnittelua”.

74 MFAA, Irma-Liisa Perttunen’s project description, 20th June 1977.

75 MFAA, Jaakko Kaikkonen’s project plan, 30th June 1975.

76 United Republic of Tanzania, Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan: Main Report 1, Preface (unpaginated).

77 MFAA, Tauno Kääriä’s letter, 9th May 1977.

78 United Republic of Tanzania, Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan: Sectoral Studies I, 1.21 General (unpaginated).

79 MFAA, I.J. Mtiro’s letter 19th August 1977.

80 United Republic of Tanzania, Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan: Main Report III.

81 Ingle, “Ten-house cell system”.

82 United Republic of Tanzania, Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan: Main Report III, 30.

83 MFA. Lake Zone Regional Physical Plan, Main Report I.

84 MFAA, Letter from the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development to Finnida, 6th November 1982

85 MFAA, Evaluation by architect Pekka Rantanen, 10th October 1983.

86 MFA, Lake Zone Regional Physical Plan, Main Report III.

87 MFAA, Zanzibar Integrated Regional Economic Land Use Plan, Project Proposal, October 1986.

88 Ibid., 15–17.

89 Ibid., 18.

90 MFAA, Consulting agreement, 30th July 1986.

91 Jennings, Surrogates of the State, 60.

92 Kleemeier, “Foreign Assistance”.

93 MFA, Tanzania, 14–17.

94 MFA, Tanzania, 19.

95 Wright, Politics of Design. See also Bonneuil, “Development As Experiment”.

96 MFAA, Heikki Ravila’s Summary and Evaluation of the Uhuru Corridor Plan, August 1978.

97 Moisio, Valtio, alue, politiikka.

98 Kaikkonen, “Suomalaista yhdyskuntasuunnittelua” (translation from Finnish by author).

Bibliography

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections On the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1983.

- Beeckmans, Luce. “French Planning in a Former Belgian Colony. A Critical Analysis of the French Urban Planning Missions in Post-independence Kinshasa.” OASE 82 (2010): 55–76.

- Beeckmans, Luce. “The Architecture of Nation-building in Africa As a Development Aid Project: Designing the Capital Cities of Kinshasa (Congo) and Dodoma (Tanzania) in the Post-independence Years.” Progress in Planning 122 (2018): 1–28.

- Berre, N. “Norwegian Expert Export to Independent Zambia.” OASE 95 (2015): 48–59.

- Beyer, Elke. “Building Institutions in Kabul in the 1960s. Sites, Spaces and Architectures of Development Cooperation.” The Journal of Architecture: Urban Planning and Architecture of Late Socialism 24, no. 5 (2019): 604–630.

- Bonneuil, C. “Development As Experiment: Science and State Building in Late Colonial and Postcolonial Africa, 1930–1970.” Osiris 15 (2000): 258–281.

- Bryceson, Deborah. “Household, Hoe, and Nation: Development Policies of the Nyerere Era.” In Tanzania After Nyerere, edited by Michael Hodd, 35–48. London: Pinter, 1988.

- Cooper, Frederick. Africa Since 1940: The Past of the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- De Raedt, Kim. “Between ‘True Believers’ and Operational Experts: UNESCO Architects and School Building in Post-colonial Africa.” The Journal of Architecture 19, no. 1 (2014): 1–24.

- De Raedt, Kim. “Policies, People, Projects. School Building as Development Aid in Postcolonial Sub-Saharan Africa.” PhD thesis, Ghent University, 2017.

- Engh, Sunniva, and Helge Pharo. “Nordic Cooperation in Providing Development Aid.” In Regional Cooperation and International Organizations: The Nordic Model in Transnational Alignment, edited by Norbert Götz, and Heidi Haggrén, Routledge Advances in International Relations and Global Politics, 112–130. London: Routledge, 2009.

- Escobar, Arturo. “Planning.” In The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power, edited by Wolfgang Sachs, 132–145. London: Zed Books, 1992.

- Escobar, Arturo. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Ferguson, James. The Anti-Politics Machine: “Development,” Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

- Hakkarainen, Outi, Miia Toikka, and Thomas Wallgren. Unelmia maailmasta: suomalaisen kehitysmaaliikkeen juurilla [Dreams of the World: at the Roots of Finnish aid Movement]. Helsinki: Like, 2000.

- Hankkio, Antti, and Edgar H. Berege. Moshi Master Plan 1974-1994: 1, Main Report. Dar es Salaam: United republic of Tanzania: Ministry of lands, housing and urban development: Urban planning division, 1976.

- Havnevik, Kjell J. Tanzania: The Limits to Development From Above. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet: Mkuki na Noyta, 1993.

- Herz, Manuel. “The New Domain: Architecture at the Time of Liberation.” In African Modernism – Architecture of Independence, edited by Manuel Herz, 5–15. Zurich: Park Books, 2015.

- Hess, Janet Berry. Art and Architecture in Postcolonial Africa. Jefferson: McFarland, 2006.

- Hirvonen, Katja. Basic Statistics On Finnish Aid 1961–1997. Helsinki: Institute of Development Studies, 1998.

- Hydén, Göran. Beyond Ujamaa in Tanzania: Underdevelopment and an Uncaptured Peasantry. London: Heinemann, 1980.

- Ingle, Clyde R. “The Ten-House Cell System in Tanzania: A Consideration of an Emerging Village Institution.” The Journal of Developing Areas 6, no. 2 (1972): 211–226.

- Kaikkonen, Jaakko. “Suomalaista yhdyskuntasuunnittelua Tansaniassa.” [Finnish Community Planning in Tanzania]. Arkkitehti 6 (1976): 41–45. Helsinki: Suomen arkkitehtiliitto.

- Kapoor, Ilan. The Postcolonial Politics of Development. Milton Park: Routledge, 2008.

- Kehitysyhteistyökomitea. Kehitysyhteistyökomitean Mietintö [Development Cooperation Committee Report]. Hki: [Valtioneuvosto]: [Valtion painatuskeskus, jakaja], 1978.

- Kehitysyhteistyön vuosikertomus 1972–73 [Development Cooperation Yearbook 1972–73]. Helsinki: Ulkoasiainministeriö, Kehitysyhteistyöosasto, 1974.

- Kehitysyhteistyön vuosikertomus 1974 [Development Cooperation Yearbook 1974]. Helsinki: Ulkoasiainministeriö, Kehitysyhteistyöosasto, 1975.

- Kehitysyhteistyön vuosikertomus 1975 [Development Cooperation Yearbook 1975]. Helsinki: Ulkoasianministeriö, Kehitysyhteistyöosasto, 1976.

- Kehitysyhteistyön vuosikertomus 1976 [Development Cooperation Yearbook 1976]. Helsinki: Ulkoasiainministeriö, Kehitysyhteistyöosasto, 1977.

- Kehitysyhteistyön vuosikertomus 1977 [Development Cooperation Yearbook 1977]. Helsinki: Ulkoasiainministeriö, Kehitysyhteistyöosasto, 1978.

- Kehitysyhteistyön vuosikertomus 1978–79 [Development Cooperation Yearbook 1978–79]. Helsinki: Ulkoasiainministeriö, Kehitysyhteistyöosasto, 1980.

- Kehitysyhteistyön Vuosikertomus 1980 [Development Cooperation Yearbook 1980]. Helsinki: Ulkoasiainministeriö, Kehitysyhteistyöosasto, 1981.

- Kleemeier, Idzz. “Foreign Assistance Projects in Regional Planning, Tanzania 1972–1982” (seminar paper, Political Science Department, University of Dar es Salaam, 1982).

- Koda, Bertha, and Pekka Seppälä. The Making of a Periphery: Economic Development and Cultural Encounters in Southern Tanzania. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 1998.

- Koponen, Juhani. Some Trends in Quantity and Quality of Finnish Aid, With Particular Reference to Tanzania and Nepal. Helsinki: Institute of Development Studies, 1998.

- Koponen, Juhani. Finnish Aid to Tanzania: Still Afloat. Helsinki: University of Helsinki, Institute of Development Studies, 2001.

- Koponen, Juhani. Oma suu ja pussin suu: Suomen kehitysyhteistyön suppea historia [Own Mouth and Bag’s Mouth: a Short History of Finnish Development Cooperation]. Helsinki: J. Koponen, 2005.

- Kothari, Uma. A Radical History of Development Studies: Individuals, Institutions and Ideologies. Cape Town: Zed Books, 2005.

- Laakso, Mikko, and Seppo Tamminen. Rakentajat maailmalla: vientirakentamisen vuosikymmenet [Builders Abroad: Decades of Construction Export]. Helsinki: Suomen rakennusinsinöörien liitto, 2014.

- Leinikki, Sikke. Finns in Development Aid: An Overview. Helsinki: Institute of Development Studies, 1998.

- Määttä, Raimo. “Rakennusalan yritysten vienti ja asiantuntijatehtävät Suomen kehitysyhteistyön puitteissa vv. 1970-1978” [Construction Companies’ Export and Expert Commissions within the Framework of Finnish Development Cooperation in 1970–1978] (seminar paper, TKK, Rakennusinsinööriosasto. Rakennustuotantotekniikan seminaari, 1979).

- Moisio, Sami. Valtio, Alue, Politiikka: Suomen Tilasuhteiden Sääntely Toisesta Maailmansodasta Nykypäivään [State, region, policy: Regulation of Finland’s spatial relations from the Second World War to the present day]. Tampere: Vastapaino, 2012.

- Monson, Jamie. Africa's Freedom Railway: How a Chinese Development Project Changed Lives and Livelihoods in Tanzania. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

- Myers, Garth Andrew. African Cities: Alternative Visions of Urban Theory and Practice. New York: Zed Books Ltd, 2011.

- Nasr, Joe, and Mercedes Volait. Urbanism: Imported or Exported?: Native Aspirations and Foreign Plans. London: Wiley-Academy, 2003.

- Nordberg, Rainer, and Clement Mlindwa. Tanga Master Plan 1975-1995: Dar Es Salaam: United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development: Urban Planning Division 1976. 1, Main Report. Helsinki: 1975.

- Nyerere, Julius K. Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism. Repr. Dar es Salaam: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- Nyerere, Julius K. The Arusha Declaration Ten Years After. Dar es Salaam: Government Printer, 1977.

- Odendaal, Nancy, James Duminy, and Daniel K. B. Inkoom. “The Developmentalist Origins and Evolution of Planning Education in Sub-Saharan Africa, c. 1940 to 2010.” In Urban Planning in Sub-Saharan Africa: Colonial and Post-Colonial Planning Cultures, edited by Carlos Nunes Silva, 285–299. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Palmberg, Mai. “The Nordic Colonial Mind.” In Complying with Colonialism: Gender, Race and Ethnicity in the Nordic Region, edited by Sari Irni, Suvi Keskinen, Diana Mulinari, and Salla Tuori, 35–50. Farnham: Ashgate, 2009.

- Phokaides, Petros. “Rural Networks and Planned Communities: Doxiadis Associates’ Plans for Rural Settlements in Post-independence Zambia.” The Journal of Architecture 23, no. 3 (2018): 471–497.

- Porvali, Harri. Evaluation of the Development Cooperation Between the United Republic of Tanzania and Finland. Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Department for International Development Cooperation, 1995.

- Rist, Gilbert. The History of Development: From Western Origins to Global Faith. London: Zed Books, 1997.

- Siitonen, Lauri. Aid and Identity Policy: Small Donors and Aid Regime Norms. Turku: Turun yliopisto, 2005.

- Soikkanen, Timo. Presidentin ministeriö: Ulkoasiainhallinto ja ulkopolitiikan hoito Kekkosen kaudella. 2, Uudistumisen, ristiriitojen ja menestyksen vuodet 1970–81 [President’s Ministry: The Governance and Management of Foreign Policy During the Era of Kekkonen 2, Years of Reformation, Contradiction and Loss 1970–81]. Helsingissä: Otava, 2008.

- Stanek, Łukasz. “Architects from Socialist Countries in Ghana (1957–67). Modern Architecture and.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 4 (2015): 416–442.

- “Suomen ja Tansanian kehitysyhteistyö” [Development cooperation between Finland and Tanzania], Kehitysyhteistyö 2: (1972). Helsinki: The Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland.

- Swantz, Marja-Liisa. Transfer of Technology as an Intercultural Process. Helsinki: Finnish Anthropological Society, 1989.

- The Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland (MFA). Lindi Region: Integrated Development Plan for 1975/76–1979/80: 24th February 1975, Lindi, Tanzania. Helsinki: Finnplanco, 1975.

- MFA. Mtwara Regional Integrated Development Plan 1975–1980. Volume I Main Report. Helsinki: Finnconsult, 1975.

- MFA. Lake Zone Regional Physical Plan: Main Report I, Structure Plan 2000. The United Republic of Tanzania. [Place of publishing unknown]: Tanzanian-Finnish Planning Team, 1982.

- MFA. Lake Zone Regional Physical Plan, Main Report III, Urban Land Use. The United Republic of Tanzania. [Place of publishing unknown]: Tanzanian-Finnish Planning Team, 1982.

- MFA. Tanzania: Regional and Physical Planning Projects. Report of the Evaluation Mission. Report 1982:1. The Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. Helsinki, 1982.

- The Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland Archive (MFAA). Kyösti Venermo’s resumé, Research proposal, 19th November 1985. Sansibarin maankäytön suunnittelu 1984–1987, KYO.

- MFAA. Irma-Liisa Perttunen’s project description, 20th June 1977. Uhuru Corridor -projekti 1977–1978. 12.R Tansania.

- MFAA. Jaakko Kaikkonen’s Project Plan, 30th June 1975. Uhuru Corridor -projekti 1977–1978. 12.R Tansania.

- MFAA. Tauno Kääriä’s Letter, 9th May 1977. Uhuru Corridor -projekti 1977–1978. 12.R Tansania.

- MFAA. I.J. Mtiro’s Letter, 19th August 1977. Uhuru Corridor -projekti 1977–1978. 12.R Tansania.

- MFAA. Letter from the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development to Finnida, 6th November 1982. Aluesuunnitteluhankkeiden evaluaatio 1982. 12 R Tansania.

- MFAA. Zanzibar Integrated Regional Economic Land Use Plan, project proposal, October 1986. Sansibarin maankäytön suunnittelu 1984–1987, KYO.

- MFAA. Consulting Agreement, 30th July 1986. Sansibarin maankäytön suunnittelu 1984–1987, KYO.

- MFAA. Heikki Ravila’s Summary and Evaluation of the Uhuru Corridor Plan, August 1978. Uhuru Corridor -projekti 1977–1978. 12.R Tansania.

- MFAA. Evaluation by Architect Pekka Rantanen, 10th October 1983. Järvialueen suunnitteluprojekti 1980 III. 12.R Tansania.

- United Republic of Tanzania. Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development, and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan: Main Report I, Structure Plan 1995. Hki; Dar es Salaam: [Republic of Finland]: [United Republic of Tanzania], 1978.

- United Republic of Tanzania. Ministry of Lands Housing and Urban Development, and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan: Main Report III, Urban Land Use. Hki; Dar es Salaam: [Republic of Finland]: United Republic of Tanzania, 1978.

- United Republic of Tanzania. Ministry of Lands Housing and Urban Development, and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. Uhuru Corridor Regional Physical Plan: Sectoral Studies I, Socio-economic Activities. Hki; Dar es Salaam: [Republic of Finland]: United Republic of Tanzania, 1978.

- Van Bilzen, Gerard. Development of Aid. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015.

- Vuolajärvi, Niina. “Rotu etnisten suhteiden tutkimuksessa.” [Race in Ethnical Relations’ Studies] In Muokattu elämä: teknotiede, sukupuoli ja materiaalisuus, edited by Sari Irni, Mianna Meskus, and Venla Oikkonen, 264–301. Tampere: Vastapaino, 2014.

- Wakeman, Rosemary. “Rethinking Postwar Planning History.” Planning Perspectives 29, no. 2 (2013): 1–11.

- Ward, Stephen V. “Transnational Planners in a Postcolonial World.” In Crossing Borders: International Exchange and Planning Practices, edited by Patsy Healey, and Robert Upton, 47–72. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2010.

- Wright, Gwendolyn. The Politics of Design in French Colonial Urbanism. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1991.