ABSTRACT

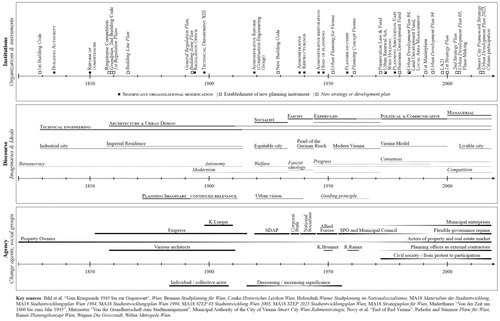

This paper presents a periodized overview of two centuries of urban planning in Vienna, providing an entry point for scholars approaching the city from an historically informed perspective. It begins with introducing a way of systematizing and periodizing stable formations and transitions of a time- and place-specific configuration of urban planning. Combining the ASID heuristic with an Historical-Institutionalist and Strategic-Relational-Institutionalist perspective, it depicts the following planning phases in Vienna: Capitalist Land Management (1829–1858), Urban Design (1858–1919), Social Planning (1919–1934), Fascist Planning (1934–1945), Modernist Expert Planning (1945–1972), Comprehensive Planning (1972–2000), and Strategic Management (since 2000). To conclude, the paper debates the value of periodized planning history for planning research, planning practice, and comparative planning history.

Introduction: why systematization, periodization and place matter in urban planning history

Encouraged by the growing recognition of evolutionary perspectives in planning,Footnote1 researchers increasingly turn to history when trying to make sense of the places they are approaching. Historically contextualizing urban development can be a challenging task though, since urban history usually comprises a vast and unsystematic body of literature that is hard to survey – not to mention language barriers often hindering a deep dive into the matter.Footnote2 This is particularly true for urban planning history, since historic studies generally have a tough job in the future- and practice-oriented discipline of planning.Footnote3 Past land management decisions, long-gone developments, and prior institutional changes are usually not exhaustively reviewed or systematically analyzed. Mostly, the urban planning historiography of a certain city comprises a wide-ranging but fragmented collection of studies with a bias towards those phases or policy areas the city is widely recognized for.Footnote4 This, in turn, makes the general aspiration of historically informed approaches to planning research a game of chance.

Systematic, periodized urban planning history matters for several reasons. First, comprehensive overviews to place-specific urban planning histories are still significantly underrepresented in the field.Footnote5 Yet, they can be vital to ‘addressing the interrelation between “episodes” of governance and the broader socio-economic and political context.’Footnote6 Simply put: By illustrating the big picture of when, how and why certain forms of planning evolved in reaction or anticipation to changing development conditions, such systematized overviews can add considerable explanatory value to how urban planning and urban development relate. Moreover, they can make potential case studies of urban transformation more approachable, providing entry points to all types of historically informed analyses of urban development, since, ‘[h]istory can help practitioners understand why they do what they do by highlighting the contingent nature and historical origins of planning institutions and practices.’Footnote7

Second, developing a theory-led framework for unraveling the place-and time-specific evolution of urban planning takes the recurring claim of going ‘beyond empirical and narrative-driven research’Footnote8 seriously. Periodized urban planning history can aid further comparative analyses aiming at detailing the similarities and differences between a global disciplinary history and a geographically and culturally delimited planning system with its distinct historic paths. It herewith addresses the call ‘[…]to rethink and critique the idea of an “objective” history of urban planning practice and to challenge the very notion of a monolithic reading of urban planning history.’Footnote9

Third, with reference to Collingwood, ‘[t]he attempt to distinguish periods in history is a mark of advanced and mature historical thought, not afraid to interpret facts instead of merely ascertaining them.’Footnote10 This is particularly important considering that planning has played divergent roles in shaping the history of cities ever since.Footnote11 One can expect these roles to entail different impacts on urban development in the respective time. Knowledge about place- and time-specific planning histories thus contributes to some of the core endeavours of urban development and planning research, such as better assessing the performance or failure of plan-making and implementationFootnote12 or insights on the role of planning in differing urban and regional development trajectories.Footnote13

Agency, structure, institutions, discourse: periodizing past formations of the planning-development relation

To date, studies making periodization their subject of discussion have yet to cover urban planning histories. Recent research either deals with larger spatial scales,Footnote14 focuses on very specific urban issues,Footnote15 or refers to urban plans as sole instances of historic periodization.Footnote16 This paper takes a relational perspective that aims at periodizing place- and path-sensitive urban planning histories by pointing to historically specific, stable formations of urban planning in a given city vis-à-vis its respective structural development conditions at the time being. It defines urban planning as a strategic state project – a mode of regulating a city’s urban development path – that is constantly contested by competing actors’ interests and influenced by super- and subordinate planning levels, other policy areas and socio-economic development at large.Footnote17 The agency-structure-institutions-discourse heuristic (ASID), a model for analyzing the modes of regulating socio-economic development at different spatial scales,Footnote18 thus constitutes a well-suited framework for its conceptualization and contextualization.

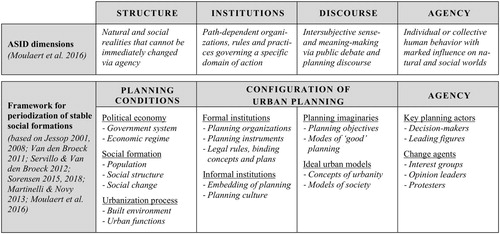

ASID offers a clear initial definition of its four major dimensions: Simply put, structure constitutes the relatively stable development circumstances. Institutions refers to a constraining or facilitating ensemble of organizations, rules and practices established for governing specific policy fields. Agency, then, comprises the totality of influential human action, whereas discourse subsumes the process of meaning making.Footnote19 The applicability to an analysis of the planning-development relation is apparent. Structure comprises those material development factors that ‘heavily condition trajectories’.Footnote20 City size, socio-economic structure, and in- and exclusion,Footnote21 the model of society, and the government systemFootnote22 together form the ‘planning conditions’ that frame the constitution and transformation of urban planning. The institutional dimension describes the arrangement of all organizations, practices and instruments related to the field of planning. It distinguishes formal institutions, such as planning organizations, legal rules, instruments, binding concepts and plans, and informal institutions, such as the role of planning in society and the ‘rules of the game’, i.e. a planning culture.Footnote23 Agency refers to the key actors ‘doing’ planning, as well as the opinion leaders and change agents inducing counter-hegemonic movements.Footnote24 Discourse refers to ‘how actors simplify a complex natural and social world by distinguishing what is important for them’.Footnote25 Planning is one arena of complexity reduction, where imaginaries of urbanity, society and planning itself are being negotiated. Public and political debate are thus significant discursive elements.

However, ASID is a place- and time-sensitive model emphasizing the territorial embedding and historical specificity of socio-economic development paths. Analyses would fail if they simply organized historic events according to the ASID dimensions. They attain significance only upon an historically and territorially contextualized identification of interrelated events within and between the ASID dimensions, hence pointing to stable formations.Footnote26 A sound historical synopsis of the interplay of planning and development – the persistence and transience of urban planning in anticipation of or reaction to context, strategic agency, discursive logics and competing institutional orders – is key. It allows accentuating distinct planning phases and their interrelation with urban development paths, points to significant characteristics of and differences between periods, and hints at explanations for the current path-dependent configuration of urban planning.

The heuristic thus needs to be enriched with middle-range perspectives on the evolution and interlinkages of the constituents of the planning-development relation to offer sufficient criteria for periodization. Due to their foundation in the same habitat of institutional theory as ASID, recent institutionalist studies of planning meet these requirements, thus deserving a more thorough exploration.Footnote27 Two noteworthy approaches stand out: Historical Institutionalism (henceforth HI) and the Strategic-Relational-Institutionalist Approach (henceforth SRI).

HI largely employs a political science perspective on institutions.Footnote28 While topics span from energy transitionFootnote29 and planning culturesFootnote30 to European spatial development,Footnote31 applying HI to historical analyses of institutional change in planning makes particular sense, since ‘planning history can be told as a history of institution-building’.Footnote32 Herewith, HI also responds to criticisms of empirical and narrative-driven planning historiographies.Footnote33 As Sorensen elaborates, it provides a theoretical foundation to ‘the analysis of patterns of continuity and change in urban governance’,Footnote34 thereby tackling two core questions: Why did certain modes of regulating city building develop the way they did, and how did planning impact cities?Footnote35

Building on Jessop’s state theory and strategic-relational approach,Footnote36 the SRI has made a similarly valuable contribution to the scholarly debate on the constituents of urban planning. The theoretical depth of Jessop’s body of work, its curiosity with the emergence, contestation, replacement, and selectivity of systems, and the related dialectic between the material world and its interpretation make it a powerful research perspective.Footnote37 A range of studies has already exemplified its applicability in planning researchFootnote38, including explanations of the social construction of planning systems.Footnote39

HI and the SRI share an interest in the relational nature of complex social formations and trajectories and what causes them to endure or transform. Thus, they offer a variety of valuable analytical elements to add to ASID, aiding a thorough periodization of time- and place-specific planning histories. ASID conceptualizes development trajectories as determined by different social fields and related institutional orders, each established to tackle a specific social problem.Footnote40 Planning is one such field. The SRI refers to planning systems as the arrangement of all rules, competences and practices necessary to steer spatial dynamics.Footnote41 HI defines planning as ‘a multifaceted system of decision rules, shared understandings, codes, and organizations charged with regulating city building’.Footnote42 Hence, urban planning serves as an important constraining or facilitating force in the regulation and reproduction of space, making the governance of spatial development a key variable of urban and regional development as well as a significant area of analysis regarding socio-economic development, path-shaping and path-dependency.

As regards change, critical junctures, i.e. ‘bursts of activity during moments of political opportunity’Footnote43 can be key indicators. Hence, processes and events pointing to the emergence, selection, retention, contestation, or replacement of certain arrangements and hegemonic projects are important.Footnote44 Yet, the self-reinforcing dynamics of the planning configuration can endure trajectories and rigidify paths and planning phases, explaining their potential resistance to such critical junctures or changing planning conditions. Attention should also be payed to the co-evolution and mutual influence of scales and other subsystems or policy areas – particularly major institutional, discursive and agential developments on super- and subordinate planning levels.Footnote45

According to the HI- and SRI-enriched ASID heuristic, the planning-development relation thus can be conceptualized as follows: The duality of structural planning conditions and individual and collective action is mediated by the discursive and institutional configuration of urban planning (cf. ). In terms of periodization, only a relatively stable formation of these constituents over a longer period points to coherent planning phases.

Empirically, the points made above imply that the periodization of urban planning history has to be considered an iterative endeavour of collecting and contextualizing, relating and interpreting, re-examining and re-interpreting historic facts and events as part of a multi-scalar, time- and place-specific trajectory.Footnote46 The following tripartite approach describes a reasonable empirical path to this end:

By drawing on local archives and primary sources from public administration, urban development and planning, as well as secondary sources from urban history and planning studies, significant historic events of the local planning-development nexus can be gathered. Systematically organizing these events along the abovementioned HI- and SRI-enriched ASID dimensions (cf. ) allows generating an initial, multidimensional chronology of events.

Based on this outline, stretches of relative stability in urban planning can already be identified to delineate phases signifying settled configurations as opposed to times of transition. Starting with an interpretive review of the structure dimension, i.e. the local planning conditions, might point to some critical junctures or ‘big changes, such as during political revolutions or major economic crises’Footnote47 that, in combination with transformative events in the planning system, indicate significant transformation and, thus, a transition of phases.

Extending the spectrum of abovementioned sources then allows expanding on discerned structural alterations, institutional changes, influential agency, discourse formations and, importantly, their respective interrelations. This, again, enables an iterative delimitation of major planning phases and a more substantiated perspective on change in urban planning history.

In the following section, I present the results of conducting these steps for the case of Vienna, describing seven historically distinct formations of the planning-development relation.

Historic phases of urban planning in Vienna

Vienna’s urban history is a vastly researched field. The knowledge spectrum on its evolution from the 2.000-years old Ancient Roman settlement at the Empire’s limes to the networked Central European metropolis of today is hard to survey. A few studies on the ‘modern’ Austrian capital’s development since its industrial heydays stand out though, together drawing up an extensive historiography of roughly 200 years.Footnote48 As concerns urban planning, Vienna is an equally well-debated case study and an esteemed and often-cited example of ‘good planning’.Footnote49 Yet, studies at the intersection of these two exhaustive discourses are limited to a comparably small number. To date, only two pieces give an overview of Vienna’s urban planning history: MatznetterFootnote50 describes the evolution of urban planning in Vienna in analogy to Albers’ four planning phases.Footnote51 And Pirhofer & Stimmer reflect on planning in Vienna based on the major development strategies issued post-1945.Footnote52 The latter call for a deeper analysis of the city’s planning history and systematic confrontation with distinct planning phases themselves: ‘A more thorough study would need to analyze the historic transitions and breaks in the urban and spatial value system. This would not just contribute to a more scientifically substantiated history of planning and its long-term results, but to a better assessment of its future development.’Footnote53

These studies, as well as the present paper, refer to the municipality of Vienna as their object of analysis, i.e. those organizations, instruments and discourses largely devised to shaping urban development within the administrative boundaries of the city. However, the areas of competence on different planning levels as defined in Austrian Spatial Planning Law,Footnote54 and structural forces such as state form, the division of power, or the city’s boundary-crossing functional ties of course demand a multi-scalar perspective going beyond the municipality in analytical terms.

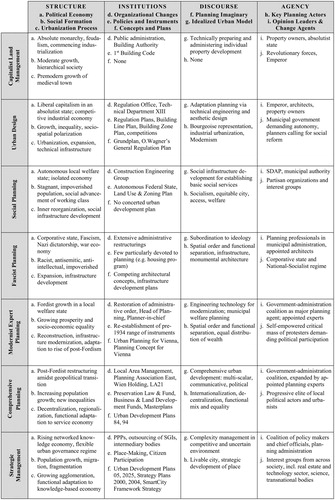

Thus, it is reasonable to start the effort of periodizing urban planning history with an interpretive review of structural planning conditions, as these might already point to big changes and critical junctures with influence on urban planning. The overview begins with the 1820s, when modern planning history starts taking shape in Vienna.Footnote55 It points to World Wars I and II as the most impactful historic caesurae that imply overarching changes to the political, social and economic dimension of urban development. In addition, the categories’ characteristics convey an initial fourfold division of the analyzed timespan (cf. ):

Before 1918: Liberal capitalism in an imperial state, rapid industrialization, population growth, increasing density, growing urban problems, polarized class society

Interwar years: Autonomous local welfare state in newly formed Republic, political upheaval, stagnating industrial economy, poverty, shrinking population, settlement growth

1945–1980s: Fordism, local welfare state, prosperous and homogenous society, stagnating population, settlement growth, inner differentiation, suburbanization

After 1980s: Post-Fordism, eroding welfare state, flexible governance, diversity and fragmentation, population growth, re-urbanization

Figure 2. Transforming planning conditions: Vienna’s political economy, social formation, and urbanization process, 1820–2020.

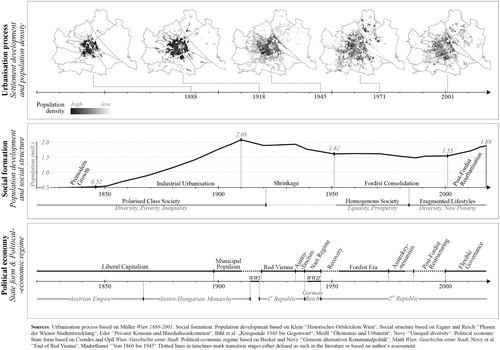

A similar overview of significant events influencing the configuration of urban planning – institution building and formative discourses – and of important individual and collective change agents complements the review of the city’s structural development history. The timelines are equally indicative of unique formations (cf. ). In terms of agency, three things stand out: (1) The dominant imperial state of the nineteenth century and Vienna’s budding municipal autonomy at the turn to the twentieth century, (2) a strong partisan influence on city planning in the first half of the twentieth century, and (3) an increasing diversity of actors since the 1970s. Planning discourse is characterized by (1) the imperial and industrial vision of nineteenth century Vienna and the increasing influence of reformist concepts, (2) ideologically permeated imaginaries and ideals in the first half of the twentieth century, and (3) the post-war succession from technocratic modernization to considerate communicative urban politics and strategic governance in a competitive globalized environment. Regarding significant institutional modifications at critical junctures, prominent events are: (1) The newly established instruments and regulatory plans enabling concerted physical planning after 1858 respectively 1893, (2) the new municipal bylaws (‘Geschäftsordnung des Magistrats’) expanding the area of influence of urban planning in 1920/21, and (3) the plethora of organizational and instrumental innovations of the 1970s.

Figure 3. Changing configurations of urban planning: Influential agents, discursive and institutional formations, 1820–2020.

In consequence, these events and their interrelations allow carving out the following formations of the planning-development nexus for Vienna:

Capitalist Land Management: regulating industrial growth (1829–1858)

Nineteenth century Vienna was characterized by the city’s transformation from small medieval town to multi-ethnic industrial metropolis. Burgeoning growth called for order and routine in urban development. The enactment of the first building code in 1829 thus judicially institutionalized urban land management in Vienna and specified general rules for property development in the manorial system.Footnote56 Six years later, in 1835, the Building Authority (‘Stadtbauamt’) was established to oversee all related technical and legal matters.Footnote57 In 1849/50, in the aftermath of the bourgeois revolution and amidst ongoing urban growth, planning competencies were reformed and redistributed between private land owners and the municipality. However, local authorities were still limited to administering development decisions made by property owners respectively the Austrian Empire. Industrialization fuelled large infrastructure projects that drastically changed the city’s physical and functional organization, such as the establishment of an extensive railroad network from the 1840s on.Footnote58 The municipality though had no say regarding the configuration of those projects in the bureaucratic, absolutist state.Footnote59 While in the first half of the nineteenth century Viennese administration was thus restricted to land management, the incremental formation of these first regulatory instruments still laid an important foundation for the establishment of urban planning.

Urban Design: physical planning for representation, growth, and reform (1858–1919)

In an era of liberal capitalism, Vienna thrived as the core of a competitive economy based on industrial production.Footnote60 The city saw a constant rise in industrial sites and kept on attracting workforce from the Crown lands of the Austro-Hungarian monarchyFootnote61 to reach over 2 mill. inhabitants in 1910.Footnote62 This created three problems, each affecting the configuration of planning: (1) Accommodating growth in a city that had already incorporated its suburbs in 1850 but was again growing too small,Footnote63 (2) adapting the medieval and rural settlements to industrial needs,Footnote64 and (3) handling increasing socio-economic and socio-spatial polarization between inner city aristocratic wealth and suburban working-class poverty.Footnote65

Since Vienna’s fortifications had become obsolete and the surrounding area (‘Glacis’) was ‘unbuilt land waiting to be exploited’,Footnote66 the Emperor and the Ministry of Interior launched a master plan competition for the area’s development into a boulevard surrounding the inner city in 1958, from which the Ringstraße and the adjacent building blocks would emerge in subsequent decades. To safeguard the realization of this unprecedented urban reconstruction project, in 1859 Vienna’s building code was revised by the State to clarify the municipality’s and property owners’ rights and obligations, and a development plan (‘Grundplan’) based on the competition’s outcome was ratified by the Emperor.Footnote67 While mainly serving the representation of the Empire and Viennese aristocracy and generating revenue through land development, the Ringstraße project spurred the emergence of competitions and plans for the city’s physical adaptation to population growth and industrialization. The Building Line Plan of 1866 and the first regulation plans published in the 1860s by Ludwig Förster and August Siccard von Siccardsburg symbolize the institutionalization of planning as urban design for adapting the built city – most notably Vienna’s suburbs – to industrial needs.Footnote68

However, the municipality had yet to gain autonomy in shaping the city’s physical constitution and greater urban development path. In a phase of Municipal Populism led by mayor Karl Lueger from 1898 to 1910, local government started communalizing a number of privately operated infrastructures that had been erected during the phase of industrialization – most notably gas and electricity and the tram network – to gain political autonomy through revenue.Footnote69 A step towards local planning sovereignty was the Building Zone Plan (‘Bauzonenplan’) of 1893, the first city-wide ruling for building heights and densities that was issued in response to the incorporation of Vienna’s outskirts the year before, by which the urban area tripled.Footnote70 The formation of the predecessor of today’s Municipal Urban Planning Department, Technical Department XIII (‘Fachabteilung XIII’) in the Building Authority in 1898, furthered the organizational establishment of municipal urban planning in Vienna. Yet, at the time it was overburdened by growth and pressing social problems that would have demanded comprehensive concepts it was not equipped for by the liberal State.Footnote71 This is despite the fact that reformist social ideals had already begun to take centre stage, challenging the hegemony of those land management instruments solely serving capitalist interests.Footnote72 Otto Wagner’s Regulation Plan (‘Generalregulierungsplan’) of 1893 best illustrates the increasing interest in visionary plans that anticipate future development and the growing significance of social reform through progressive urban design.Footnote73 Importantly, it largely focused on the development of urban centres and transport planning – two areas of municipal competence.Footnote74 The Regulation Office established in 1894 should oversee its incremental implementation.Footnote75 However, halted urban growth and the outbreak of WWI impeded the plan’s realization. Thus, while facilitating the rapid extension of a city meeting high technical standards, early planning in Vienna ultimately failed to tackle corresponding social problems. This became particularly severe during war, when all planned municipal infrastructure developments and private housing construction stopped immediately, while the city’s population kept on growing.Footnote76 Hardship and poverty were striking in a city that had lost its economic base and had largely been cut off from food supply. To reduce rising social unrest, the State unwillingly established new welfare-oriented departments in the municipal authority and instated social policies – such as a Rent Act securing thousands of tenants from eviction – that urban politics would pick up after war.Footnote77

Social Planning: social infrastructure development for an equitable city (1919–1934)

Poverty and a weakened economy framed the interwar period in the capital of the newly founded, small Austrian Republic.Footnote78 Yet, the end of imperial heteronomy, the municipal electoral victory of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP) in 1919, and the city’s newly achieved status as autonomous federal state in 1922 marked the onset to a period of Municipal Socialism: ‘Red Vienna’. The propagating Socialist idea, a stagnant population, and an overly dense but technically well-equipped city facilitated a refocused political approach in the 1920s.Footnote79 The following infrastructure programme and multi-faceted policies targeting working class needs symbolize the origin of the local welfare state in ViennaFootnote80 and a transformed role of planning. After half a century of physical planning for capitalist industrialization, a period of social infrastructure development for social well-being set in.

Wide-ranging institutional rearrangements came along with the changed planning self-conception. To put its policy on the ground, Social-Democratic leadership adopted the new municipal bylaws in 1920/21 that clustered land management, infrastructure- and construction-related matters in a construction-engineering group (‘Gruppe Bautechnik’). Planning henceforth consisted of setting up basic services as politically devised.Footnote81 The building code of 1929 introduced land use (‘Flächenwidmungsplan’) and zoning plan (‘Bebauungsplan’) as new preparatory land management instruments,Footnote82 complementing the institutional arsenal of an increasingly powerful local state that aimed at regulating the city’s spatial development. Backed by public administration and a majority of citizens all pursuing the shared Austro-Marxist imaginary of equality, access and welfare,Footnote83 the SDAP established a planning configuration for social infrastructure development that amalgamated politics and planning and made the Party the major planning agent in interwar Vienna.

However, The Austro-Marxist labour movement never truly managed to tackle the latent ideological polarization of Vienna’s population.Footnote84 The increasing tensions leading to civil war, a ban of the SDAP and the proclamation of the Austro-fascist state in 1934 thus put Red Vienna to a rough end and ultimately segued into Austria’s annexation to the Third Reich in 1938.Footnote85

Fascist Planning: spatial order and ideological representation (1934–1945)

The Austro-Fascist state immediately withdrew Red Vienna’s social housing programme, curtailed the city’s autonomy and exploited planning as its ideological medium by relegating it to the implementation of technical infrastructure for job creation. The support of single-family housing for the elites in suburban areas best symbolizes the radical departure from Social Planning, the retrograde urban imaginary, and the hierarchical social ideal of the corporative state.Footnote86

With Nazi takeover in 1938, the ambivalence of Fascist planning between the obsessive disparagement of Socialist, Modernist and culturally diverse Vienna and the city’s glorification as ‘The Pearl of the Third Reich’ became evident.Footnote87 In October of 1938, the National-Socialist regime instantly decided to incorporate 97 surrounding municipalities to form ‘Groß-Wien’ – a symbolic act that should hint at Vienna’s increased significance in the Third Reich.Footnote88 Since the regime regarded the physical city and urban social life as key expressions of ideology,Footnote89 Vienna’s Gauleiter Baldur von Schirach appointed the architect Hanns Dustmann in 1940 to develop a monumental architectural concept for Groß-Wien.Footnote90 It included, among other things, a military parading axis that would have run through one of the districts with the highest shares of Jewish population and the makeover of Heldenplatz and the city hall.Footnote91 Due to constant disputes between the regime and well-established local architectural and planning experts of the municipal administration regarding planning and design matters, this and most of the other concepts developed during National-Socialist rule never came to fruition.Footnote92 However, the regime heavily transformed the institutional formation of planning. The administrative restructurings of 1938 and 1940 reduced the role of planning from foresight and development to a subordinate instrument for preparing the megalomaniac physical representations of power and an ideologically overloaded model of society.Footnote93 The subordination of planning to Nazi ideology was further enforced by the replacement of civil servants with those loyal to the regime, the withdrawal of planning professionals’ contracts, and the consequent displacement and deportation of intellectuals.Footnote94 The culmination of Fascism in war lastly was a caesura in Vienna’s urban development history. Yet, as concerns the configuration of urban planning, post-war changes concerned the municipal institutional order rather than the people involved and the knowledge applied in urban planning. As studies unveil, several planning professionals who had been installed by the NS regime, survived the denazification process, suggesting that Nazi ideology was not fully eradicated from Viennese planning after 1945.Footnote95 Also, these professionals of course had been advocating a Rational Planning Model, modernist urban design principles, and the adaptation of city life to technical innovation (e.g. motorized private transport) before, during, and after Fascist rule, as the following phase would reveal.Footnote96

Modernist Expert Planning: ideal urban systems in the Fordist welfare state (1945–1972)

The consequences of war left Vienna in uncertainty.Footnote97 In 1945, local politics re-established the pre-1934 institutional order and the city’s new municipal boundaries that are still in effect today, although Russian allies would only consent to both in 1954.Footnote98 The experts’ commission for the city’s reconstruction (‘Enquete für den Wiederaufbau’), instated by local politics in 1945, favoured a functional makeover of the bombed city that would match the urban ideal of spatial order and functional separation (‘Die gegliederte und aufgelockerte Stadt’) of the time.Footnote99 But a lack of resources and political uncertainty about the future of occupied Vienna made rebuilding the historically evolved urban structure seem more realistic.Footnote100

Recovery only accelerated in the mid-50s by virtue of Fordist growth and increasing prosperity, which were soon followed by economic restructuring and wealth-induced suburbanization in the 60s and 70s.Footnote101 For the first time in Viennese history, socio-economic equality, political stability and prosperity characterized the city.Footnote102 Fordism and a zeitgeisty belief in progress induced a catch-up process in infrastructure modernization that put engineering technology at the forefront of planning debate and implementation in the 50s and 60s. Large-scale housing estates in prefabricated construction and the decision to establish a subway system were two among many representations of a triumphing technocratic planning imaginary.Footnote103 The modernist urban concepts issued at that timeFootnote104 only encouraged the realization of such substantial interventions. The projects and plans were backed by the handover of wide-ranging planning sovereignty to appointed experts Karl Brunner (1948–1952), respectively Roland Rainer (1958–1963) – a consolidation of expert-driven technical modernity.Footnote105 Yet, the municipal council relocated all planning agendas to the municipal authority in 1963, as it deemed the experts’ envisioned modernization pathways incompatible with the prevailing Social-Democratic ideal.Footnote106 This illustrates the all-encompassing planning power of the government-administration coalition during that planning phase. The municipality was a major property owner and, due to its ongoing social housing construction activity, also the biggest property developer of the time being.Footnote107 Due to its double role as both municipality and federal state with its own planning laws, the municipal authority was also an undisputed discourse-shaping force and the sole decision-maker in urban development.Footnote108 At the turn to the 1970s though, the coalition’s increasingly reckless modernization approach evoked civic protest,Footnote109 leading to a reinterpretation of planning that was amplified by the dawning crisis of Fordism.

In summary, economic upsurge and efforts of dissociating urban planning from ideology leveraged a phase of technocratic expertise in Vienna’s post-war planning. Infrastructure development and urban expansion reflected growing prosperity and the two competing modernization imaginaries of expert-driven engineering technology and the caring state’s welfare planning (‘sozialer Städtebau’). Both yielded to a self-empowered critical mass commanding political participation, which translated into a heavily changed approach thereafter.

Comprehensive Planning: considerate and communicative urban development for all (1972–2000)

The 1970s heralded a period of socio-economic and physical restructuring. With production relocating to the surrounding region, Vienna’s outskirts converted into residential and service sector areas. While some of them slowly turned into urban sub-centres of the new post-Fordist functional pattern,Footnote110 inner-city areas had not changed much in the past century and thus did not meet modern expectations anymore. Yet, a self-empowered critical mass of citizens took issue with the radical modernization approach of past decades. Their argument was reinforced by ecological goals and preservative measures entering planning discourse and planning law in most Austrian Federal States in the early 1970s.Footnote111 In Vienna, the Preservation Law (‘Altstadterhaltungsgesetz’) and Preservation Fund (‘Altstadterhaltungsfonds’) for the historic centre were thus established in 1972.Footnote112 But only following the Federal Urban Renewal Act of 1974, protesters’ calls for more considerate planning were heard. The municipal authority implemented measures of soft urban renewal (‘sanfte Stadterneuerung’) that aimed at considerately upgrading low quality nineteenth century housing structures. Due to their success, they were carried over into the Local Area Management (‘Gebietsbetreuung’) in 1984 – one of the institutional cornerstones of the ‘Vienna Model’ of soft urban renewal.Footnote113

Meanwhile, increasing planning complexity was met with other significant changes in political thinking and administrative attitudes, most notably the mayor’s decision to draw up the first-ever comprehensive urban development plan in 1976.Footnote114 In less than a decade, the dominant planning imaginary turned from ‘modernization at all costs’ to comprehensive, multi-scalar, communicative and political process.Footnote115 Two examples of a correspondingly changing institutional landscape put this on display: the 1974-established Wien Holding indicating the increasing amalgamation of urban and economic development policy, and the Eastern Austrian Planning Association (‘Planungsgemeinschaft Ost’), which enshrined urban-regional coordination in 1978.Footnote116

As supply-oriented location policies increasingly replaced demand-driven approaches,Footnote117 the service sector, consumerism, tourism, and culture consolidated as major urban industries from the mid-1980s on.Footnote118 At about that time, migration became key to recommencing population growth, social diversity, and the self-image of an internationalizing city.Footnote119 However, inequality increased as well, as continuously growing average household incomes alongside rising unemployment rates in the 1980s showed.Footnote120 The two Urban Development Plans of 1984 and 1994 illustrate the resulting challenge indicative of late twentieth century planning in Vienna: an increasingly unmanageable diversity of policy fields, scales and interests, and a balancing act between scientific expertise and political process, between perpetuating welfare planning and adopting a competitive development model.Footnote121 The Fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 and Austria’s imminent accession to the European Union in 1995 though aided the prevalence of the competition-oriented, pro-active approach, which was also favoured by the progressive elite of municipal political actors and urbanists.Footnote122 The later rejected plans to host an EXPO in 1995Footnote123 and Vienna’s first-ever master-planned and privately developed large-scale project, the DonauCity, already hinted at the successive policy shift at the turn of the century.Footnote124 Until then, the government-administration coalition remained the undisputed driving force and change agent in regulating the fortunes of urban planning.

Strategic Management: Anticipating change in a competitive, complex world (since 2000)

The new millennium marks the beginning of the current planning phase and the triumph of the strategic management ideal over the proven comprehensive approach.Footnote125 New EU policies and narratives of interurban competition played a major part in establishing the ‘new conventional wisdom’Footnote126 of strategic planning for opportunity and image at the time. The ESDP of 1999 and the Lisbon Strategy of 2000 heavily influenced urban planning with their calls for sustainable, yet competitive territorial development and ‘dynamic, attractive and competitive cities’.Footnote127 Local politicians and chief officials understood the potential a fast-growing population and knowledge economy and the imminent EU expansions held for establishing Vienna as a competitive Central European hub.Footnote128 The Strategy Plans of 2000 and 2004, issued to put Vienna on the map of global competitors for human and investment capital, were immediate replies to the new development context.Footnote129 The determination of themed Target Areas of Urban Development (‘Zielgebiete der Stadtentwicklung’) in the Urban Development Plan of 2005, and the assignment of associated Target Area Managers for each of themFootnote130 further pointed to the adoption of a strategic management model in urban planning. The bureaucratic method of treating urban development duties in accordance with the institutional order of a rigid political-administrative system was herewith increasingly substituted by the managerial mode of strategically promoting distinct potentials and places for competitiveness.Footnote131 In consequence, PPPs became a significant development modelFootnote132 and intermediaries that were closely linked to the political-administrative system, such as the Vienna Tourism Agency, gained force as discourse-shaping actors in the new flexible governance regime.Footnote133 Other notable institutional departures from the well-established twentieth century welfare-planning regime were the outsourcing of formerly municipal organizations providing services of general interest,Footnote134 as well as the re-structuring of the city’s housing market.Footnote135 Moreover, planning discourses increasingly involved ostensibly non-spatial matters such as digitization,Footnote136 novel participatory practices,Footnote137 and diversity instead of equality as the envisioned social model.Footnote138 Together, these made twenty-first century urban development discourses and policies more open and flexible, yet arbitrary at the same time.

The result was a historically distinct formation characterized by a flexible urban governance regime that adopted a managerial stance to strategically approach urban development under the ambivalent conditions of urban growth, resource scarcity, and multiple crises.Footnote139 The power of public discourse and struggles for opinion leadership became obvious now that actors and interest groups from across society infused, expanded or replaced the once undisputed government-administration coalition, making urban planning the political arena for negotiating an increasingly contested urban development path.Footnote140 While this entailed new inclusive, bottom-up, and emancipatory practices, the flipside was a noticeable shift to strategic development and liberal governance.Footnote141

Conclusion: advancing periodized urban planning history

In this paper, I presented an approach for periodizing urban planning history, aiming at making the time- and place-specific evolution of urban planning and distinct urban development paths more accessible to researchers and practitioners. Employing the ASID heuristic and enriching it with empirical categories from HI and SRI approaches to planning research, it was possible to put urban planning in its place within the ASID logic, define agency, structure, institutions and discourse as elements of the planning-development relation, and develop an understanding of how these elements and their interrelations influence the evolution of stable planning phases.

I conceptualized urban planning as an institutional and discursive mode of regulating an urban development path by means of adaptations to the built environment and social and economic processes in space. Changing planning conditions, i.e. multi-scalar structural forces, influence urban development and the configuration of urban planning and agency, too, in this regard. The relational conception of urban planning is in line with Schubert’s claim that planning history has to consist of more than the mere analysis of plans.Footnote142 Using ASID and institutionalist planning theory allows conceptualizing a framework that takes the mutual structure-agency relations and the intermediary discourses and institution-building processes into account as relevant dimensions of the planning-development relation.

I have exemplified the approach with the case of Vienna, a well-researched city in terms of its social, economic and political history that is lacking equally comprehensive studies on its urban planning history. The analysis has allowed the demarcation of historically distinct planning phases in Vienna – each characterized by a time- and place-specific, yet scale-sensitive formation of governing spatial development as such and socio-economic development in space (cf. for a condensed overview). Herewith, the paper has added substantial knowledge to the locally distinct evolution of urban planning in Vienna.

However, one might argue that comprehensive historiographies like the one presented above leave out key historical facts or lengthy discussions of causal relations, thus oversimplifying planning history. Indeed, it is imperative to point out that ‘[a]ny periodization […] relating to a particular sector such as planning will always amount to a heuristic given the multiple threads of evolving and overlapping policy, time lags, and the need to generalize across space and scale.’Footnote143 It is still of value, since periodization is ‘a heuristic device to help make sense of a messy world.’Footnote144 It is an important step in complexity reduction to make a sometimes unsystematic body of knowledge accessible to students, scholars, and practitioners who are in search of such entry points to urban development and planning history. However, the definite temporal division between clear-cut planning eras neither implies that paradigmatic changes have taken place at the transition of two planning phases, nor does it by contrast suggest that all of the above transitions have been subject to incremental change in the configuration of urban planning. If anything, the discerned phases build on one another in the sense of a ‘cumulative knowledge of planning’Footnote145 that is mirrored by an institutional landscape and a planning-political discourse of ever-increasing complexity. Which individual factors, critical junctures, and strategic-relational formations actually informed the transition between stable regulation phases and how these went about in detail thus has to be regarded a question for future research on Vienna’s planning history.

The paper though still highlights those features constituting time- and place-specific stable planning phases and the progression of urban planning in that city. This opens up new prospects for inquiries, such as in-depth analyses of institution building processes. Studies on the role of strategic agency in adapting planning institutions could be a valuable expansion in this regard.Footnote146 Multi-scalar linkages have also proven to be influential with regard to the historic transformation of urban planning. In particular, this holds true for the influence of critical shifts on national and supranational level on local development and planning. As the analysis unveiled, while often ‘externalized’, such critical moments and transitions can have discourse-shaping power, influencing local planning action, institutions and planning conditions. The influence of disciplinary advancements on the configuration of planning is another relevant point in this regard. Hence, both the time- and place-specific institutional formation of ‘the right way of planning’ and the power of discourse in establishing local development imaginaries vis-à-vis trans-local change could be worthy fields of future research for planning history.

In summary, the proposed approach aids researchers and practitioners in their endeavours to ‘make sense’ of local development and planning phenomena, both past and present. Moreover, periodized planning history can help advancing comparative analyses of planning history that uncover the similarities and differences between certain time- and place-specific, path-dependent formations of planning.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to my colleagues Justin Kadi, Walter Matznetter and Alexander Hamedinger as well as the reviewers of Planning Perspectives for their feedback on an earlier version of the text.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Johannes Suitner

Johannes Suitner is a trained spatial planner with expertise in Urban and Regional Development, Transition Studies, and Planning Theory. He has been working both in academia and practice and currently holds a PostDoc position at the Institute of Spatial Planning at TU Wien. His recent research deals with transformative climate governance, the role of agency, institutional work, and social innovation in regional energy transition, and the institutionalization of disciplinary knowledge in planning. Suitner is a published researcher on regional energy transition, metropolitan development, planning cultures, urban imaginaries, and Vienna's historical and cultural transformation.

Notes

1 Moulaert “Institutional Economics and Planning”; Mehmood “Evolutionary Metaphors in Planning” and Duehr “Europe of ‘Petite Europes’”.

2 Ward et al., “The ‘new’ planning history”, 236.

3 Hein “What, Why and How of Planning History”, 2.

4 Ward “Cities as planning models”.

5 Ward et al., “The ‘new’ planning history”, 241.

6 Healey, “Collaborative Planning in Perspective”, 115.

7 Fischler, “Linking Planning Theory and History”, 234.

8 Hein, “What, Why and How of Planning History”, 5.

9 Kramsch, “Tropics of Planning Discourse”, 164.

10 Collingwood, The Idea of History, 53.

11 Marcuse, “Three Historic Currents of City Planning”.

12 Hopkins, “Plan Assessment”.

13 Pike et al., “Local and Regional Development”; Martinelli and Novy, “Urban and regional trajectories”.

14 Nedović-Budić and Dabović, “Serbian spatial planning legislation”; Allmendinger and Haughton, “Evolution and Trajectories of English Spatial Governance”; Duehr, “Europe of ‘Petite Europes’”; Faludi, “A historical institutionalist account of European spatial planning”

15 Aalbers, “The great moderation”.

16 Orhan, “Reading vulnerabilities through urban planning history”.

17 Jessop, State Power; Schubert “Cities and plans”; Servillo and Van den Broeck “Social Construction of Planning”.

18 Moulaert et al., “Agency, structure, institutions, discourse”.

19 Ibid., 169.

20 Martinelli and Novy, “Urban and regional trajectories”, 305.

21 Ibid.

22 Servillo and Van den Broeck, “Social Construction of Planning”, 49.

23 Martinelli and Novy, “Urban and regional trajectories”, 301; Servillo and Van den Broeck, “Social Construction of Planning”, 44.

24 Martinelli and Novy, “Urban and regional trajectories”, 299.

25 Moulaert et al., “Agency, structure, institutions, discourse”, 176.

26 Martinelli and Novy, “Urban and regional trajectories”, 292ff.

27 See for instance Van den Broeck, “Analysing Social Innovation”; Servillo and Van den Broeck, “Social Construction of Planning”; Sorensen “Taking path dependence seriously”; Sorensen, “Critical junctures in planning”; Sorensen, “Planning History and Theory”.

28 Sorensen, “Critical junctures in planning”, 617; Sorensen, “Planning History and Theory”, 38.

29 Lockwood et al., “Politics of energy transitions”.

30 Taylor, “Rethinking planning culture”.

31 Faludi, “A historical institutionalist account of European spatial planning”.

32 Sorensen, “Taking path dependence seriously”, 19.

33 Ward et al., “The ‘new’ planning history”, 244; Hein, “What, Why, and How of Planning History”, 7.

34 Sorensen, “Taking path dependence seriously”, 19.

35 Ibid.

36 Jessop, “The Strategic-relational Approach”; Jessop, State Power.

37 Jessop, State Power.

38 Lagendijk, “Accident of the region”; Servillo, “Territorial Cohesion Discourses”; Van den Broeck, “Analysing Social Innovation”.

39 Servillo and Van den Broeck, “Social Construction of Planning”.

40 Moulaert et al., “Agency, structure, institutions, discourse”, 172.

41 Servillo and Van den Broeck, “Social Construction of Planning”, 43.

42 Sorensen, “Taking path dependence seriously”, 19.

43 Ibid, 31.

44 Jessop, State Power.

45 Sorensen, “Planning History and Theory”, 41.

46 Moulaert et al., “Agency, structure, institutions, discourse”.

47 Sorensen, “Critical junctures in planning”, 618.

48 See particularly Csendes and Opll, Wien. Geschichte einer Stadt; Czeike Historisches Lexikon Wien; Brunner and Schneider, Umwelt Stadt; Eigner and Resch, “Phasen der Wiener Stadtentwicklung”.

49 Cf. Ward, “Cities as planning models”, 300.

50 Matznetter, “Von der Grundherrschaft zum Stadtmanagement”.

51 Albers, “Wandel im Planungsverständnis”.

52 Pirhofer and Stimmer, Pläne für Wien.

53 Ibid., 180 (author’s translation).

54 Cf. Kanonier and Schindelegger, “Development Phases of Austrian Spatial Planning Law”.

55 Czeike, Historisches Lexikon Wien; Matznetter, “Von der Grundherrschaft zum Stadtmanagement”.

56 Ibid.

57 Pirhofer and Stimmer, Pläne für Wien.

58 Maderthaner, “Von der Zeit um 1860 bis zum Jahr 1945”, 224.

59 Buchmann, “Die Epoche vom Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts bis um 1860”, 89f.

60 Becker and Novy, “Chancen und Grenzen alternativer Kommunalpolitik”, 3.

61 Maderthaner, “Von der Zeit um 1860 bis zum Jahr 1945”.

62 Klein, Historisches Ortslexikon Wien.

63 Czeike, Historisches Lexikon Wien.

64 Maderthaner, “Von der Zeit um 1860 bis zum Jahr 1945”.

65 Maderthaner and Musner, “Outcast Vienna 1900”, 26.

66 Hall, Planning Europe’s Capital Cities, 398.

67 Czeike, Historisches Lexikon Wien; Hall, Planning Europe’s Capital Cities.

68 Czeike, Historisches Lexikon Wien Vol.5, 298; Albers, “Über den Wandel im Planungsverständnis”.

69 Buchmann, “Die Epoche vom Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts bis um 1860”, 89f.

70 Czeike Historisches Lexikon Wien. 299.

71 Pirhofer and Stimmer, Pläne für Wien.

72 Matznetter, “Von der Grundherrschaft zum Stadtmanagement”, 70.

73 Cf. Schweitzer, “Der Generalregulierungsplan für Wien”, 24.

74 Ibid.

75 Czeike, Historisches Lexikon Wien.

76 Eigner, “Die wachsende Stadt”.

77 Pirhofer and Stimmer, Pläne für Wien.

78 Becker and Novy, “Chancen und Grenzen alternativer Kommunalpolitik”, 8.

79 Kadi and Suitner, “Red Vienna”, 1.

80 Matznetter, “Von der Grundherrschaft zum Stadtmanagement”, 70.

81 Weber, “Metropole Wien”, 9ff.

82 Czeike, Historisches Lexikon Wien, 299.

83 Kadi and Suitner, “Red Vienna”, 1.

84 Maderthaner, “ Von der Zeit um 1860 bis zum Jahr 1945”, 429ff.

85 Ibid., 489ff.

86 Czeike, Historisches Lexikon Wien, 299.

87 Holzschuh, Wien. Die Perle des Reiches.

88 Csendes and Opll, Wien. Geschichte einer Stadt.

89 Cf. Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, Das ungebaute Wien.

90 Holzschuh, Wiener Stadtplanung im Nationalsozialismus.

91 Ibid.

92 Holzschuh, Wiener Stadtplanung im Nationalsozialismus, 74f.

93 Maderthaner, “Von der Zeit um 1860 bis zum Jahr 1945”, 518.

94 Holzschuh, Wiener Stadtplanung im Nationalsozialismus, 113f.

95 Holzschuh, Wien. Die Perle des Reiches.

96 Mattl et al., Wien in der nationalsozialistischen Ordnung des Raums.

97 Bihl et al., “Vom Kriegsende 1945 bis zur Gegenwart”, 545.

98 Pirhofer and Stimmer, Pläne für Wien.

99 Ibid.

100 Diefendorf, “Planning postwar Vienna”.

101 Eigner and Resch, “Phasen der Wiener Stadtentwicklung”, 6.

102 Novy, “Unequal diversity”, 244.

103 Pirhofer and Stimmer, Pläne für Wien, 44ff.

104 Most notably, these are Brunner, Stadtplanung für Wien; Rainer Planungskonzept Wien.

105 Weber, Metropole Wien, 9ff.

106 Diefendorf, “Planning postwar Vienna”.

107 Bihl et al., “Vom Kriegsende 1945 bis zur Gegenwart”, 590, 596.

108 Pirhofer and Stimmer, Pläne für Wien, 51.

109 Mattl, Wien im 20. Jahrhundert, 87.

110 Hatz and Weinhold, “Die polyzentrische Stadt”.

111 Kanonier and Schindelegger, “Development Phases of Austrian Spatial Planning Law”, 71.

112 Bihl et al., “Vom Kriegsende 1945 bis zur Gegenwart”, 593f.

113 Feuerstein, “Anfänge der sanften Stadterneuerung in Wien”.

114 Pirhofer and Stimmer, Pläne für Wien.

115 See MA18, Stadtentwicklungsplan Wien 1984.

116 Pirhofer and Stimmer, Pläne für Wien, 142.

117 Meißl, “Ökonomie und Urbanität”, 700ff.

118 Hatz, “Kultur als Instrument der Stadtplanung”; Suitner, Imagineering Cultural Vienna.

119 Kohlbacher and Reeger, “Zuwanderung und Segregation”, 181.

120 Eder, “Privater Konsum und Haushaltseinkommen”.

121 See MA18, Stadtentwicklungsplan Wien 1984, MA18 Stadtentwicklungsplan Wien 1994.

122 Cf. for instance the contributions in Swoboda, Richtung Wien.

123 Ibid.

124 Novy et al., “End of Red Vienna”, 132.

125 Cf. Frey et al., “Rückkehr der großen Pläne”.

126 Gordon and Buck, “Cities in the new conventional wisdom”.

127 European Commission, European Spatial Development Perspective, 22.

128 Cf., among others, Giffinger and Hamedinger, “Metropolitan competitiveness reconsidered”; Giffinger and Suitner, “Polycentric Metropolitan Development”.

129 MA18, Strategieplan für Wien.

130 MA18, STEP 05 Stadtentwicklung Wien 2005, 202.

131 Dangschat and Hamedinger, “Planning Culture in Austria”, 101f.

132 Hatz, “Vienna”.

133 Suitner, Imagineering Cultural Vienna.

134 Weber, Metropole Wien, 9ff.

135 Kadi, “Recommodifying Housing in Vienna”.

136 Municipal Authority of the City of Vienna, Smart City Wien Rahmenstrategie, 20f.

137 Novy and Hammer, “Radical Innovation in the Era of Liberal Governance”, 213, 215.

138 Novy, “Unequal diversity”, 247.

139 Cf. Municipal Authority of the City of Vienna, Smart City Wien Rahmenstrategie.

140 Suitner Imagineering Cultural Vienna; Exner et al., “Smart City Policies in Wien, Berlin und Barcelona”.

141 Cf. particularly the arguments elaborated in Novy et al., “End of Red Vienna”; Seiß, “Wer baut Wien”; Sohn and Giffinger, “Policy Network Approach to Cross-border Metropolitan Governance”.

142 Schubert, “Cities and plans”, 3.

143 Allmendinger and Haughton, “Evolution and Trajectories of English Spatial Governance”, 13.

144 Aalbers, “The great moderation”, 56.

145 Schubert, “Cities and plans”, 18.

146 Cf. for instance Lawrence and Suddaby’s “Institutions and institutional work” for an analytical framework of forms of institutional work for creating, maintaining, or disrupting institutions.

Bibliography

- Aalbers, Manuel. “The Great Moderation, the Great Excess and the Global Housing Crisis.” International Journal of Housing Policy 15, no. 1 (2015): 43–60.

- Albers, Gerd. “Über den Wandel im Planungsverständnis.” In Wohn-Stadt, edited by Martin Wentz, 45–55. Frankfurt and New York: Campus, 1993.

- Allmendinger, Phil, and Graham Haughton. “The Evolution and Trajectories of English Spatial Governance: ‘Neoliberal’ Episodes in Planning.” Planning Practice & Research 28, no. 1 (2013): 6–26.

- Becker, Joachim, and Andreas Novy. “„Chancen und Grenzen Alternativer Kommunalpolitik in Wien – ein Historischer Überblick.” Kurswechsel 2, no. 99 (1999): 5–16.

- Bihl, Gustav, Gerhard Meißl, and Lutz Musner. “Vom Kriegsende 1945 bis zur Gegenwart.” In Wien. Geschichte Einer Stadt. Band 3: Von 1790 bis zur Gegenwart, edited by Peter Csendes, and Ferdinand Opll, 545–650. Vienna: Böhlau, 2006.

- Brunner, Karl. Stadtplanung für Wien. Edited by Stadtbauamt der Stadt Wien. Vienna: Verlag für Jugend und Volk GmbH, 1952.

- Brunner, Karl, and Petra Schneider. Umwelt Stadt. Geschichte des Natur- und Lebensraumes Wien. Wiener Umweltstudien, Vol.1. Vienna: Böhlau, 2005.

- Buchmann, Bertrand Michael. “Die Epoche vom Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts bis um 1860.” In Wien. Geschichte Einer Stadt. Vol. 3, Von 1790 bis zur Gegenwart, edited by Peter Csendes, and Ferdinand Opll, 85–127. Vienna: Böhlau, 2006.

- Collingwood, Robin George. The Idea of History. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946.

- Csendes, Peter, and Ferdinand Oppl. Wien. Geschichte Einer Stadt. Vol. 3, Von 1790 bis zur Gegenwart. Vienna: Böhlau, 2006.

- Czeike, Felix. Historisches Lexikon Wien, Vol.1-6. Vienna: Kremayr & Scheriau, 1992-2004.

- Czeike, Felix. Historisches Lexikon Wien, Vol.5 Ru-Z. Vienna: Kremayr & Scheriau, 2004.

- Dangschat, Jens, and Alexander Hamedinger. “Planning Culture in Austria – The Case of Vienna, the Unlike City.” In Planning Cultures in Europe. Decoding Cultural Phenomena in Urban and Regional Planning, edited by Jörg Knieling, and Frank Othengrafen, 95–112. New York and London: Routledge, 2009.

- Diefendorf, Jerry M. “Planning Postwar Vienna.” Planning Perspectives 8 (1993): 1–19.

- Duehr, Stefanie. “A Europe of ‘Petite Europes’: an Evolutionary Perspective on Transnational Cooperation on Spatial Planning.” Planning Perspectives 33, no. 4 (2018): 543–569.

- Eder, Franz X. “Privater Konsum und Haushaltseinkommen im 20. Jahrhundert.” In Wien im 20. Jahrhundert. Wirtschaft, Bevölkerung, Konsum, edited by Franz X. Eder, Peter Eigner, Andreas Resch, and Andreas Weigl, 201–285. Vienna: Studien, 2003.

- Eigner, Peter. Die wachsende Stadt: Wien am Vorabend des Ersten Weltkriegs. (2020). https://ww1.habsburger.net/de/kapitel/die-wachsende-stadt-wien-am-vorabend-des-ersten-weltkriegs.

- Eigner, Peter, and Andreas Resch. Phasen der Wiener Stadtentwicklung. Unpublished manuscript (2001). http://www.demokratiezentrum.org.

- European Commission. ESDP. European Spatial Development Perspective. Towards Balanced and Sustainable Development of the Territory of the European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/pdf/sum_en.pdf.

- Exner, Andreas, Livia Cepoiu, and Carla Weinzierl. “Smart City Policies in Wien, Berlin und Barcelona.” In Smart City. Kritische Perspektiven auf die Digitalisierung in Städten, edited by Sibylle Baureidl, and Anke Strüver, 333–344. Bielefeld: transcript, 2018.

- Faludi, Andreas. “A Historical Institutionalist Account of European Spatial Planning.” In Planning Perspectives 33, no. 4 (2018): 507–522.

- Feuerstein, Christiane. “Anfänge der Sanften Stadterneuerung in Wien.” In Wann Begann Temporär? Frühe Stadtinterventionen und Sanfte Stadterneuerung in Wien, edited by Christiane Feuerstein, and Angelika Fitz, 9–60. Vienna and New York: Springer, 2009.

- Fischler, Raphaël. “Linking Planning Theory and History: The Case of Development Control.” In Journal of Planning Education and Research 19 (2000): 233–241.

- Frey, Otto, Donald A. Keller, Arnold Klotz, Michael Koch, and Klaus Selle. “Rückkehr der Großen Pläne?” In DisP – The Planning Review 39, no. 153 (2003): 13–18.

- Giffinger, Rudolf, and Alexander Hamedinger. “Metropolitan Competitiveness Reconsidered. The Role of Territorial Capital and Metropolitan Governance.” Terra Spectra – Planning Studies – Central European Journal of Spatial and Landscape Planning 1, no. 20 (2009): 3–12.

- Giffinger, Rudolf, and Johannes Suitner. “Polycentric Metropolitan Development: From Structural Assessment to Processual Dimension.” European Planning Studies 23, no. 6 (2015): 1169–1186.

- Gordon, Ian, and Nick Buck. “Cities in the new Conventional Wisdom.” In Cities. Rethinking Urban Competitiveness, Cohesion and Governance, edited by Nick Buck, Ian Gordon, Alan Harding, and Ivan Turok, 1–24. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hall, Thomas. Planning Europe’s Capital Cities. Aspects of Nineteenth-Century Urban Development. London: E & FN Spon, 1997.

- Hatz, Gerhard. “Vienna.” Cities 25 (2008): 310–322.

- Hatz, Gerhard. “Kultur als Instrument der Stadtplanung.” In Wien – Städtebauliche Strukturen und Gesellschaftliche Entwicklungen, edited by Heinz Fassmann, Gerhard Hatz, and Walter Matznetter, 299–336. Vienna: Böhlau, 2008.

- Hatz, Gerhard, and Elmar Weinhold. “Die Polyzentrische Stadt: Neue Urbane Zentren.” In Wien – Städtebauliche Strukturen und Gesellschaftliche Entwicklungen, edited by Heinz Fassmann, Gerhard Hatz, and Walter Matznetter, 337–384. Vienna: Böhlau, 2009.

- Healey, Patsy. “Collaborative Planning in Perspective.” Planning Theory 2, no. 2 (2003): 101–123.

- Hein, Carola. “The What, Why and How of Planning History.” In The Routledge Handbook of Planning History, edited by Carola Hein, 1–10. New York and London: Routledge, 2018.

- Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien. Das ungebaute Wien. Projekte für die Metropole. 1800-2000 exhibition catalogue edited by Museen der Stadt Wien, 1999.

- Holzschuh, Ingrid. Wien. Die Perle des Reiches. Planen für Hitler. Zurich: Park Books, 2015.

- Holzschuh, Ingrid. Wiener Stadtplanung im Nationalsozialismus von 1938 bis 1942. Das Neugestaltungsprojekt von Architekt Hanns Dustmann. Vienna: Böhlau, 2015.

- Hopkins, Lewis D. “Plan Assessment: Making and Using Plans Well.” In The Oxford Handbook of Urban Planning, edited by Rachel Weber, and Randall Crane, 803–822. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Jessop, Bob. “Institutional (Re)Turns and the Strategic-Relational Approach.” Environment & Planning A 33 (2001): 1213–1235.

- Jessop, Bob. “Recent Societal and Urban Change: Principles of Periodization and Views on the Current Period.” In Urban Mutations: Periodization, Scale and Mobility, edited by Tom Nielsen, Niels Albertsen, and Peter Hemmersam, 40–65. Aarhus: Arkitektskolen Forlag, 2004.

- Jessop, Bob. State Power. A Strategic-Relational Approach. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press, 2008.

- Kadi, Justin. “Recommodifying Housing in Formerly ‘Red’ Vienna?” Housing, Theory and Society 32, no. 3 (2015): 247–265.

- Kadi, Justin, and Johannes Suitner. “Red Vienna, 1919-1934.” In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies, edited by Anthony M. Orum. London: Wiley Blackwell, 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118568446.eurs0259.

- Kanonier, Arthur, and Arthur Schindelegger. “Development Phases of Austrian Spatial Planning Law.” In Spatial Planning in Austria with References to Spatial Development and Regional Policy edited by Office of the Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning (ÖROK). Vienna: ÖROK (ÖROK Publication Series No. 202).

- Klein, Kurt. Historisches Ortslexikon Wien. Statistische Dokumentation zur Bevölkerungs- und Siedlungsgeschichte (2001). http://www.oeaw.ac.at/fileadmin/subsites/Institute/VID/PDF/Publications/diverse_Publications/Historisches_Ortslexikon/Ortslexikon_Wien.pdf.

- Kohlbacher, Josef, and Ursula Reeger. “Zuwanderung und Segregation in Wien.” In Zuwanderung und Segregation. Europäische Metropolen im Vergleich, edited by Heinz Fassmann, Josef Kohlbacher, and Ursula Reeger, 181–195. Klagenfurt & Celovec: Drava, 2002.

- Kramsch, Olivier. “Tropics of Planning Discourse. Stalking the ‘Constructive Imaginary’ of Selected Urban Planning Histories.” In Making the Invisible Visible. A Multicultural Planning History, edited by Leonie Sandercock, 163–183. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1998.

- Lagendijk, Arnoud. “The Accident of the Region. A Strategic Relational Perspective on the Construction of the Region’s Significance.” Regional Studies 41, no. 9 (2007): 1193–1207.

- Lawrence, Thomas B., and Roy Suddaby. “Institutions and Institutional Work.” In Sage Handbook of Organization Studies, edited by Stewart R. Clegg, Cynthia Hardy, Walter R. Nord, and Thomas B. Lawrence, 215–254. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2006.

- Lockwood, Matthew, Caroline Kuzemko, Catherine Mitchell, and Richard Hoggett. “Historical Institutionalism and the Politics of Sustainable Energy Transitions: A Research Agenda.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35, no. 2 (2016): 312–333.

- MA18 [Municipal Department 18 of the Municipal Authority, City of Vienna]. Stadtentwicklungsplan Wien 1984. Vienna: Municipal Authority of the City of Vienna, 1985.

- MA18 [Municipal Department 18 of the Municipal Authority, City of Vienna]. Stadtentwicklungsplan für Wien 1994. Vienna: Municipal Department 18, Municipal Authority, City of Vienna, 1994.

- MA18 [Municipal Department 18 of the Municipal Authority, City of Vienna]. Strategieplan für Wien. Vienna: Municipal Department 18, Municipal Authority, City of Vienna, 2000.

- MA18 [Municipal Department 18 of the Municipal Authority, City of Vienna]. STEP 05. Stadtentwicklung Wien 2005. Vienna: Municipal Department 18, Municipal Authority, City of Vienna, 2005.

- Maderthaner, Wolfgang. “Von der Zeit um 1860 bis zum Jahr 1945.” In Wien. Geschichte Einer Stadt. Vol.3: Von 1790 bis zur Gegenwart, edited by Peter Csendes, and Ferdinand Opll, 175–544. Vienna: Böhlau, 2006.

- Maderthaner, Wolfgang, and Lutz Musner. “Outcast Vienna 1900: The Politics of Transgression.” International Labor and Working-Class History 64 (2003): 25–37.

- Marcuse, Peter. “The Three Historic Currents of City Planning.” In The New Blackwell Companion to the City, edited by Gary Bridge, and Sophie Watson, 643–655. Malden and others: Blackwell Publishing, 2011.

- Martinelli, Flavia, and Andreas Novy. “Urban and Regional Trajectories Between Path-Dependency and Path-Shaping: Structures, Institutions, Discourses and Agency in Contemporary Capitalism.” In Urban and Regional Development Trajectories in Contemporary Capitalism, edited by Flavia Martinelli, Frank Moulaert, and Andreas Novy, 284–315. Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2013.

- Mattl, Siegfried. Wien im 20. Jahrhundert. Vienna: Pichler, 2000.

- Mattl, Siegfried, Gottfried Pirhofer, and Franz J. Gangelmayer. Wien in der Nationalsozialistischen Ordnung des Raums. Lücken in der Wien-Erzählung. Vienna: New Academic Press, 2018.

- Matznetter, Walter. “Von der Grundherrschaft zum Stadtmanagement. Zweihundert Jahre Stadtplanung in Wien.” In Umwelt Stadt. Geschichte des Natur- und Lebensraumes Wien. Wiener Umweltstudien, Vol.1, edited by Karl Brunner, and Petra Schneider, 60–79. Vienna: Böhlau, 2005.

- Mehmood, Abid. “On the History and Potentials of Evolutionary Metaphors in Urban Planning.” Planning Theory 9, no. 1 (2010): 63–87.

- Meißl, Gerhard. “Ökonomie und Urbanität. Zur Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichtlichen Entwicklung Wiens im 20. Jahrhundert und zu Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts.” In Wien. Geschichte Einer Stadt. Band 3: Von 1790 bis zur Gegenwart, edited by Peter Csendes, and Ferdinand Opll, 651–737. Vienna: Böhlau, 2006.

- Moulaert, Frank. “Institutional Economics and Planning Theory: A Partnership Between Ostriches?” Planning Theory 4, no. 1 (2005): 21–32.

- Moulaert, Frank, Bob Jessop, and Abid Mehmood. “Agency, Structure, Institutions, Discourse (ASID) in Urban and Regional Development.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 20, no. 2 (2016): 167–187.

- Municipal Authority of the City of Vienna. Smart City Rahmenstrategie. Vienna: Municipal Authority, City of Vienna, 2014.

- Müller, Daniela. Wien 1888-2001: Zusammenhänge der Entwicklung der Technischen Infrastruktur- und ÖV-Systeme in den Siedlungsgebieten. Bern: Peter Lang, 2008.

- Nedović-Budić, Zorica, and Tijana Dabović. “The Mornings After … Serbian Spatial Planning Legislation in Context.” European Planning Studies 19, no. 3 (2011): 429–455.

- Novy, Andreas. “Unequal Diversity – on the Political Economiy of Social Cohesion in Vienna.” European Urban and Regional Studies 18, no. 3 (2011): 239–253.

- Novy, Andreas, Vanessa Redak, Johannes Jäger, and Alexander Hamedinger. “The End of Red Vienna: Recent Ruptures and Continuities in Urban Governance.” European Urban and Regional Studies 8, no. 2 (2001): 131–144.

- Novy, Andreas, and Elisabeth Hammer. “Radical Innovation in the Era of Liberal Governance. The Case of Vienna.” European Urban and Regional Studies 14, no. 3 (2007): 210–222.

- Orhan, Ezgi. “Reading Vulnerabilities Through Urban Planning History.” Metu Journal of the Faculty of Architecture 33, no. 2 (2016): 139–159.

- Pike, Andy, Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, and John Tomaney. “What Kind of Local and Regional Development and for Whom?” Regional Studies 41, no. 9 (2007): 1253–1269.

- Pirhofer, Gottfried, and Kurt Stimmer. Pläne für Wien. Theorie und Praxis der Wiener Stadtplanung von 1945 bis 2005. Vienna: Municipal Department 18, Municipal Authority, City of Vienna, 2007.

- Rainer, Roland. Planungskonzept Wien Edited by Stadtbauamt der Stadt Wien, Institut für Städtebau an der Akademie der Bildenden Künste. Vienna: Verlag für Jugend & Volk, 1961.

- Schubert, Dirk. “Cities and Plans – the Past Defines the Future.” Planning Perspectives 34, no. 1 (2019): 3–23.

- Schweitzer, Renate. “Der Generalregulierungsplan für Wien (1893-1920).” Berichte zur Raumforschung und Raumplanung 6, no. 14 (1970): 23–41.

- Seiß, Reinhard. Wer Baut Wien? Salzburg: Anton Pustet, 2007.

- Servillo, Loris Antonio. “Territorial Cohesion Discourses: Hegemonic Strategic Concepts in European Spatial Planning.” Planning Theory & Practice 11, no. 3 (2010): 397–416.

- Servillo, Loris Antonio, and Pieter Van den Broeck. “The Social Construction of Planning Systems: A Strategic-Relational Institutionalist Approach.” Planning Practice & Research 27, no. 1 (2012): 41–61.

- Sohn, Christophe, and Rudolf Giffinger. “A Policy Network Approach to Cross-Border Metropolitan Governance: The Cases of Vienna and Bratislava.” European Planning Studies 23, no. 6 (2015): 1187–1208.

- Sorensen, André. “Taking Path Dependence Seriously: an Historical Institutionalist Research Agenda in Planning History.” Planning Perspectives 30, no. 1 (2015): 17–38.

- Sorensen, André. “Multiscalar Governance and Institutional Change: Critical Junctures in European Spatial Planning.” Planning Perspectives 33, no. 4 (2018a): 615–632.

- Sorensen, André. “Planning History and Theory: Institutions, Comparison, and Temporal Processes.” In The Routledge Handbook of Planning History, edited by Carola Hein, 35–45. New York and London: Routledge, 2018b.

- Suitner, Johannes. Imagineering Cultural Vienna. On the Semiotic Regulation of Vienna’s Culture-led Urban Transformation. Bielefeld: transcript, 2015.

- Svensson, Oscar, and Alexandra Nikoleris. “Structure Reconsidered: Towards new Foundations of Explanatory Transitions Theory.” Research Policy 47 (2018): 462–473.

- Swoboda, Hannes. Wien. Identität und Stadtgestalt. Vienna: Böhlau, 1990.

- Taylor, Zack. “Rethinking Planning Culture: A New Institutionalist Approach.” Town Planning Review 84, no. 6 (2013): 683–702.

- Van den Broeck, Pieter. “Analysing Social Innovation Through Planning Instruments. A Strategic-Relational Approach.” In Strategic Spatial Projects. Catalysts for Change, edited by Stijn Oosterlynck, Jef Van den Broeck, Louis Albrechts, Frank Moulaert, and Ann Verhetsel, 70–102. New York and London: Routledge, 2011.

- Wagner, Otto. Die Groszstadt. Eine Studie über Diese. Vienna: Anton Schroll & Komp, 1911.

- Ward, Stephen V. “Cities as Planning Models.” Planning Perspectives 82, no. 3 (2013): 295–313.

- Ward, Stephen V., Robert Freestone, and Christopher Silver. “The ‘New’ Planning History. Reflections, Issues and Directions.” Town Planning Review 82, no. 3 (2011): 231–261.

- Weber, Gerhard. Metropole Wien: Technik - Urbanität - Wandel. Geschichte der Stadtbaudirektion 1986-2006. Vienna: Carl Gerold's Sohn, 2006.