ABSTRACT

Managed retreat is increasingly advocated as a means to promote resilience and adaptation to climate change. However, there are various uncertainties and challenges associated with the impacts of displacement and attachments to place. In this context, it is useful to study past examples of relocation to understand how these challenges have been addressed. This paper draws on a case study relocation scheme which took place in Ireland following major flooding in 1954. This represented a radical and comprehensive approach to relocation which sought to address the root causes of vulnerability. The analysis shows that this comprehensive approach was made possible through a connection between managed retreat and land reform. The scheme also faced opposition linked to attachments to place and property. This led to compromises and a failure to fully address the effects of flooding on livelihoods but contributed to resilience through ensuring that family and community ties remained intact. The paper’s distinctive contributions are its analysis of the requirements of transformative approaches to adaptation and relocation, its identification of challenges associated with place and property even in the context of such transformative approaches, and its adding of historical depth to contemporary debates on climate adaptation.

Introduction

Over the last decade, resilience has gained currency within planning theory and practice to address a heightened sense of risk and crises including climate change, the global economic collapse of 2008/09, and more recently the Covid-19 pandemic. The concept is often used to explore how communities, institutions and societies respond to environmental crisis and risks such as those posed by climate change and flooding.Footnote1 In the context of flooding, resilience is often used to evoke strategies which involve system-wide transformation to reduce vulnerability, rather than engineered flood defences. The literature on resilience advocates a paradigm shift towards a strategic, holistic and long-term approach characterized by accepting and adapting to the effects of more frequent and intense flooding. It demands adaptation strategies which respond to the specific requirements of different settings and significant changes in dominant cultural framings of flooding and the forms of expertise involved in its management.Footnote2

One particular flood risk management strategy which resonates with a resilience perspective is that of managed retreat. This refers to the strategic relocation of housing, infrastructure and/or entire communities in the face of flooding.Footnote3 In principle, retreat offers opportunities for a wide range of socio-economic and ecological benefits alongside long-term risk reduction and moves beyond resisting hazards towards longer-term transformative action.Footnote4 However, there are important challenges including the frequently harmful impacts of displacement on health, well-being and employment/livelihoods.Footnote5 In response, recent research identifies a need for comprehensive additional supports for those undergoing relocation such as ensuring access to employment and housing, which demands integrated planning, a high level of institutional capacity and significant resources.Footnote6 There are, however, few case studies of managed retreat where such supports have been provided and little understanding of how such comprehensive approaches might be realized in terms of issues such as governance and political context.

There are further challenges for relocation associated with place attachment. This is generally defined as a sense of belonging and connection to a particular place, including both its social and physical features.Footnote7 Place attachment is a key topic in the broader literature on climate adaptation and has been demonstrated to function as both a motivator and barrier to adaptation.Footnote8 Managed retreat is a sector of adaptation in which place attachment is particularly important because relocation can disrupt the social, economic and psychological connections between people and place.Footnote9 Such impacts are particularly acute in cases where place is deeply linked to individual and/or collective identity.Footnote10 It has also been suggested that in Ireland, particularly in rural areas, managed retreat may be challenging to implement due to historically embedded attachments to place and land.Footnote11 In response to these issues, researchers argue that there is a need for place attachment to be centred in relocation planning through greater engagement with those affected,Footnote12 but there are few studies of how this has been achieved. It is also important to note that place attachment is a complex phenomenon which is often interrelated with the significance and economic value of property.Footnote13 This raises questions regarding the origins of place attachment in specific instances and to what extent this actually stems from attachments to property. This is important because negative impacts on property might be necessary and justified in some instances, for example in the case of coastal holiday homes.Footnote14

The paper is also situated within the existing literature on flooding Ireland. Within this field, researchers have demonstrated that a diversity of strategies, besides engineered flood defences, have been used successfully in the past.Footnote15 However, these were gradually superseded by a shift towards large-scale engineering works which were primarily intended to prevent the flooding of agricultural land.Footnote16 This reliance on engineered defences has persisted despite policies which advocate a shift towards strategies aligned with a resilience perspective such as improved land-use planning, non-structural defences and wetland restoration.Footnote17 Research has also demonstrated a lack of community participation in decision-making and attention to questions of place attachment.Footnote18

In addition, while attention and investment was historically centred on rural flooding in Ireland, since the 1980s protecting agricultural land is no longer a priority and the focus has shifted to urban centres.Footnote19 It has been argued that this has created significant uncertainties regarding responsibility for rural flooding and contributed to a sense that rural areas have been abandoned.Footnote20 Research also suggests that, in some cases, farmers’ concerns regarding the impact of flooding on their livelihoods have not been adequately considered.Footnote21 Notably, there have been a series of small-scale managed retreat or ‘household relocation’ projects in rural areas in Ireland since the mid-1990s. These have essentially functioned as a stop-gap measure where no other approach to managing flooding was thought to merit investment and, correspondingly, have had negative impacts for many of those involved.Footnote22 More generally, managed retreat is often recommended as a flood risk management strategy in rural areas due to the lower cost of land and lower number of assets at risk. Such utilitarian arguments imply that economic value should be the primary metric for decision-making and arguably risk missing other impacts and costs of displacement which are not easily quantifiable.Footnote23 In response, there is a need to identify alternative models of managed retreat, including those which consider the connections between land use and livelihoods which are likely to be particularly important in rural areas.

This paper also builds on recent literature which has highlighted the value of historical studies of adaptation and the need for more research of this type.Footnote24 While this literature emphasizes that it is important to avoid understating differences between historical hazards and coping strategies and challenges faced in the present, it is widely argued that the study of past responses to extreme events can provide lessons to guide contemporary climate adaptation if the implications of these differences are accounted for.Footnote25 More specific advantages of historical studies of adaptation include the potential to add historical depth to current debates by rediscovering approaches which have been forgottenFootnote26 and by ‘particularizing adaptation’ through in-depth studies of the environmental, social and political context in which certain strategies have been effective.Footnote27 The recent historical literature on adaptation includes studies of the impacts and responses to specific environmental changes and hazards,Footnote28 of changing perceptions of hazards and the implications for how they are managed,Footnote29 and of the evolution of key concepts such as vulnerability, resilience and adaptation.Footnote30

There is a limited historical literature on managed retreat including studies of analogous phenomena such as planned resettlements to accommodate urban or industrial development.Footnote31 It is also acknowledged that unsupported migration has historically been an important adaptation strategy.Footnote32 There are a small number of studies of past examples of managed retreat in response to flooding which have highlighted both successes in managing flood risk alongside issues such as inadequate compensation, delays in planning processes and negative socio-economic impacts.Footnote33 However, these studies focus almost exclusively on the specific context of the USA and have not addressed issues of place attachment.

This paper responds to this series of issues and questions through its analysis of a distinctive and comprehensive approach to managed retreat which occurred in Ireland following major flooding in 1954, within which attachments to place and property played an important role. The paper’s overall aim is to enrich debates on adaptation, flooding and managed retreat (both Irish and international) through bringing to light a relatively successful past example of relocation and exploring the historical and political context in which this arose. The objectives are, first, to understand how the harmful impacts of displacement can be addressed including the political context for more strategic and comprehensive approaches to relocation and, second, to understand the relationship between attachments to place and property and opposition to managed retreat, and how such concerns might be addressed.

In terms of its structure, the paper first outlines the sources and methods used to develop an in-depth understanding of responses to flooding of the Shannon and the historical and political context in which these were situated. It then provides a brief overview of the case study relocation scheme and its development. Following this, the paper presents the results of the analysis structured in terms of two key issues. These are, first, the choice of retreat (rather than engineered defences) as a response to flooding and the origins of the comprehensive approach thereto. Second, it discusses attachments to place and property and their relationship to opposition to relocation. A discussion section then relates the findings to contemporary literature on adaptation and managed retreat and identifies insights which are relevant to contemporary debates.

Methods

The paper is based on archival materials, namely records of parliamentary debates (38), newspaper articles (35) and planning and policy documents (3). These were identified through relevant searchable databasesFootnote34 using broad search terms such as ‘relocation’ and ‘migration’ where these occurred in conjunction with ‘flooding’. As an understanding of the case study developed, these terms were refined to include references to particular people and places identified as significant. The scope of inquiry in the case of parliamentary debates extended from the first available records in 1919 to the final discussion of the case study in 1965. The detailed search of newspaper archives was narrower (due to the volume of results), extending from 1950 to 1965, although a small number of articles which exceeded this timeframe were included because they provided important additional information. The majority of relevant articles were from local newspapers, in particular, the Offaly Independent and Westmeath Independent. A small number of planning/policy documents were also included in the analysis, most importantly a report commissioned by the Irish government by an American engineer, known as the ‘Rydell Report’, which discussed the perceived advantages and disadvantages of managed retreat.Footnote35 All of these sources were collated in NVivo and analysed using qualitative thematic analysis.Footnote36 A list of the historical sources which are directly cited in the text is given in below.

Table 1. Primary sources cited directly in the text.

It is also important to acknowledge the limitations associated with using historical data, in particular the fact that the majority of sources relied upon in this paper reflect the perspectives of relatively influential actors such as politicians, journalists and others whose views were deemed worthy of inclusion in newspaper articles. This is similar to the methodological challenges faced in other historical studies of environmental transformation and adaptation.Footnote37 It means that it is difficult to gain a detailed understanding of the extent to which relocation was supported or otherwise by those affected and to what extent support varied between different groups within the local community. These limitations have been partially addressed through consultation of secondary sources such as works by local historian Rosaleen Fallon who has written about the legacy of the relocation scheme from a community perspective.Footnote38 Fallon’s work also provides valuable insights into the historical and social context in which the relocation scheme was situated.

Case study outline

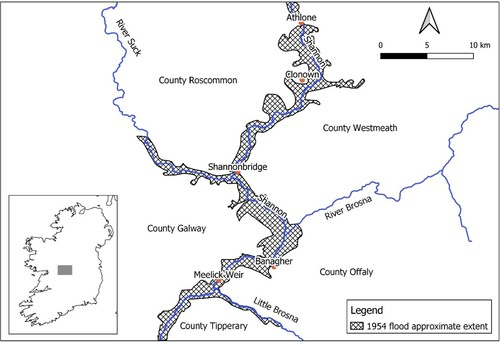

The case study discussed in this paper is an instance of flood-related relocation which took place following major flooding in 1954 in areas surrounding the River Shannon in Ireland between the town of Athlone in Co. Westmeath and Meelick Weir on the borders of Counties Galway, Tipperary, Offaly and Westmeath. At the time, this area was generally referred to as the ‘Shannon Valley’ but is now more commonly described as the ‘Shannon Callows’, with the term ‘callows’ referring to frequently flooded grassland along the river.Footnote39 The term Shannon Callows is used throughout this paper to describe the area in which the relocation scheme took place. provides a map of the case study area.

This area was (and continues to be) subject to regular summer and winter flooding with recorded floods in 1931, 1932 and 1938.Footnote40 In 1945 the Irish government, following the passage of the Arterial Drainage Act, began a large-scale programme of building flood defences along major rivers to prevent flooding of agricultural land.Footnote41 There were demands for flood defences along the Shannon including a motion brought by the opposition parties in 1952 which called on the government ‘to relieve the great plight of the many landowners who cannot use their lands’.Footnote42 However, the cost was judged to be far greater than the value of the agricultural land which would be protected and, therefore, the government decided against flood defences. This conclusion continued to be contested but also led to the consideration of managed retreat as an alternative approach to managing flood risk.

In late 1954 the area between Athlone and Meelick was subject to severe flooding. Records indicate that the flood levels experienced in 1954 were not surpassed until 2006,Footnote43 while local historian Rosaleen Fallon writes that the 1954 flood ‘is the benchmark by which all subsequent floods have been measured’.Footnote44 According to newspaper reports and parliamentary debates, it caused the inundation of approximately 25,000 acres of agricultural land, affecting approximately 2000 households and causing the direct flooding of 97 houses.Footnote45 This led to debates regarding how future flooding could be managed including through the relocation of flooded houses and farms. In June 1958, the government announced a relocation scheme, termed the ‘Shannon Valley Flood Relief Scheme’ which was carried out over the following seven years. Under this scheme, six households were relocated to new farms outside the Shannon Callows area while a further 60 households were provided with new homes on higher ground within their local communities and retained their existing farms.

Notably, the relocation scheme was planned and implemented by the Irish Land Commission (ILC), a state agency responsible for the division and redistribution of agricultural land from large landowners to smallholders and tenants, which operated from Independence in 1922 until Ireland joined the European Community in 1973. As discussed below, the role of the ILC, and the broader political and social context of land reform in early to mid-twentieth century Ireland, were decisive influences on the emergence of relocation as a flood risk management strategy and, more specifically, the particular comprehensive model of managed retreat whereby households were provided with new houses and, in some cases, with larger farms outside the flooded areas. It is also important to note that the final relocation scheme was less ambitious than what had been originally proposed by key political figures who advocated the relocation of all (approximately 100) flooded households to areas outside the Shannon Callows, including to other counties, and the abandonment of land subject to recurrent flooding. This was due to opposition arising from attachments to place and property, topics which are also discussed in detail below.

The Irish Land Commission: land reform and managed retreat

The objectives of this paper include understanding the choice of managed retreat as a strategy to manage flooding of the Shannon and, in particular, the comprehensive approach thereto.

They further include ‘particularizing’ adaptation by providing an in-depth historical and political understanding of these issues. As discussed below, the analysis shows that this relates to the ongoing process of land redistribution in post-Independence Ireland and the particular pre-existing model of ‘migration schemes’ whereby farming households were provided with new homes and larger and/or better-quality farmland.

As described by Dooley, the so-called ‘land question’ or ‘the struggle for land … dominated the social and political life of Ireland from the 1880s’ until at least the mid-twentieth century, becoming bound up with national identity and independence as well as being a basic resource for survival in an overwhelmingly agricultural society.Footnote46 After Ireland achieved independence in 1922, one key government response to this issue was the programme of land reform and redistribution carried out by the ILC. Thereafter, the ILC played a central role in political and social life until the early 1970s, being responsible for the acquisition, division and redistribution of approximately 20% of the agricultural land in the Republic of Ireland.Footnote47

The ILC’s activities arose from a range of overlapping policy objectives including providing employment, preventing emigration and boosting agricultural production. There was a particular commitment to improving the socio-economic conditions of small farmers who were both an influential political constituency and key to Irish national identity.Footnote48 Importantly, there was an accepted connection between these objectives and the management of flooding because, as demonstrated by the documentary analysis, flooding was regarded as a key threat to the livelihoods of small farmers. There was, in particular, a perceived link between deprivation, hardship and saturated or flood-prone farmland, especially in the poorest Western counties. Flooding was therefore understood as a key threat to the livelihoods and well-being of farming households and to require comprehensive state intervention. This intervention took different forms including what were termed ‘migration schemes’, an approach to land reform which provided the basis for managed retreat in response to flooding of the Shannon in 1954.

These ‘migration schemes’Footnote49 were one distinctive aspect of the ILC’s activities which involved assisting farming households to relocate from impoverished areas in the West of Ireland to larger farms and better-quality land in the East. Between 1937 and 1978 approximately 14,500 households were relocated through such means.Footnote50 Throughout the lifetime of the ILC, there were different models of migration including one, particularly dominant in the 1920s, which entailed the migration of large landowners from poorer Western counties to the East to facilitate the redistribution of their lands amongst local smallholders. Later models pursued in the 1930s-40s entailed the collective relocation of groups of farming households to the Eastern counties.Footnote51 These schemes involved the provision of a comprehensive range of supports including houses, farming equipment and training. They were voluntary and from the 1930s onwards were generally enthusiastically taken up due to the prospect of additional land and the availability of generous subsidies.Footnote52 Group migration therefore required significant investment and this was the source of opposition from fiscally conservative political actors, ultimately leading to a shift away from this model in the 1940s and 1950s.

Importantly, the analysis demonstrates that the idea of migration came to be understood as a key strategy to address the impacts of flooding on welfare and livelihoods. These points are illustrated by the following quote from Joseph Blowick, a future Minister for Lands with responsibility for the ILC, in a discussion of the conditions of farmers in Newport, Co. Mayo in 1947:

Most of these houses were erected hastily in 1846 and 1847 after the great evictions. In eight of these houses, several people have died with tuberculosis … . Most of the tillage land is submerged at times by flooding … What I suggest should be done is that, no matter what the cost, a sufficient number of people should be migrated out of these villages, so that, in these mountainous districts, a valuation of at least £10 will be given to those left behind, with decent houses, decent roads and proper sanitary accommodation.Footnote53

Tenants who live within the flooded area should be removed to the grasslands which are so plentiful in other parts of the county … If moved in groups there would be little difficulty in inducing the tenants in this portion of the county to migrate to better lands and more healthful conditions.Footnote54

The Shannon Valley Flood Alleviation Scheme: material benefits and political support

This pre-existing connection between flooding, welfare and migration/relocation provided the basis for the debates regarding relocation which followed the Shannon flood in 1954. Thus, rather than arising in isolation, this drew on the institutional and political frameworks of land reform and migration. Accordingly, although this paper predominantly uses the terms ‘managed retreat’ and ‘relocation’, the Shannon relocation scheme was consistently described in political debates and newspaper sources using the terminology of ‘migration’.

As noted above, between 1954 and 1958 different models of relocation were proposed in parliamentary debates. The more ambitious of the two models discussed, although it was not the one ultimately implemented, bore clear parallels with ILC group migration schemes. This would have entailed the collective relocation of all approximately 100 households directly affected by flooding to areas outside the Shannon Callows in a manner similar to other ILC group migration schemes of the 1930s-40s. In addition, this was envisaged both as a means to address the direct impacts of flooding and also to provide improved access to agricultural land, and thus enhanced prosperity and quality of life. For example, during a parliamentary debate on the flooding of the Shannon in 1958, John McQuillan, the representative for County Roscommon, asked:

I want to know if, even at this stage, people in that locality may take as certain that the present Minister will implement a scheme this year to remove from Clonown those men whose lands and houses are flooded? Will he be prepared to utilise the good land on the far side of the Shannon which is available to facilitate those unfortunate men who have asked for removal over the years?Footnote55

Ultimately, for reasons discussed below, this more comprehensive model was not implemented. However, although the final relocation scheme was less ambitious than previously proposed, there were still clear continuities between it and ILC migration schemes in the sense that it offered tangible benefits for those involved and sought to improve welfare and socio-economic conditions. For example, evidence from parliamentary debates suggests that the scheme followed the broader model of ILC migration schemes whereby new houses and land were provided on favourable terms through a mixture of low-interest loans and direct grants.Footnote58 The circumstances of brothers Denis and John Hughes, two of the six landowners who took up offers to relocate to areas outside the Shannon Callows under the Shannon Valley Flood Relief Scheme, provide further insight into the material benefits of relocation. Their original farms were 18 acres and 40 acres respectively at a time when the government’s definition of an ‘economic holding’, or one which could support a household in reasonable comfort, was 35 acres. Through the Shannon Valley Flood Relief Scheme, they were provided with new, adjoining farms near Moate in Westmeath with a combined size of 100 acres.Footnote59 Their example thus highlights the tangible benefits of relocation, which were likely key to farmers’ willingness to participate.

Conflicting perspectives on relocation: place attachment and opposition to land reform

A key objective of this paper is to understand the relationship between attachments to place and opposition and/or support for managed retreat, including how such concerns can be addressed. The objectives further include understanding connections between attachments to place and the economic value of land and property. In the case study, these issues are closely related to debates regarding different models of relocation. As noted above, the final relocation scheme (although it was a significant achievement) represented a scaled-down version of what was proposed by figures such as McQuillan and the Minister for Agriculture, James Dillon. While it had been proposed that all flooded householders would be relocated to areas outside the Shannon Callows, under the final scheme only six households relocated to other counties while the majority relocated within their local area to new houses on higher ground and did not get access to additional land. Importantly, this shift was due to opposition from both sections of the local community and key political actors and interests, related both to place attachment and opposition to state interference with property rights.

Due to the nature of the historical sources used, which primarily reflect the views of politicians and journalists, it is difficult to precisely ascertain the level of community support and/or opposition for relocation. There is evidence of both and that, in the case of those opposed, this was linked to strong attachments to place and community. For example, an article in the Offaly Independent from 1951 reported on a meeting of local farmers from townlands near Athlone, where ‘twenty-four were in favour of discussing with the government the question of the purchase of their holdings, whilst twenty-one were in favour of continuing their agitation for the drainage of the Shannon’.Footnote60 However, the author continued to note that farmers from other areas nearby were firmly against relocation due to their attachment to place and property. In addition, according to parliamentary records, a survey of the flooded area was conducted by the ILC soon after the flooding of 1954 and found that many people did not want to relocate. According to James Dillon, the Minister for Agriculture, such opposition was because ‘there are certain sentimental ties that attach everyone to his hearthstone, the place where he was bred, born and reared’.Footnote61

Opposition to relocation also drew on the idea that this would lead to the total disintegration of the community. This is apparent in the debates at a public meeting in January 1955 as reported in the Westmeath Independent, during which a parish priest linked relocation to emigration and rural decline stating that the area would become ‘a valley of death and silence’ if wholesale relocation took place.Footnote62 The Minister for Lands, Joseph Blowick, described how, at the same meeting, he ‘began to feel like an arch-criminal … with a plan to migrate the people from the [Shannon] Valley and leave it barren and deserted’.Footnote63 This was, moreover, a powerful narrative which gestured to contradictions between the migration scheme and the fundamental objectives of the ILC and land redistribution. These included preventing emigration and rural depopulation and, as set down in the Irish Constitution, ‘establishing on the land in economic security as many families as in the circumstances shall be practicable’, principles to which the idea of migration was, from one perspective, antithetical.Footnote64

The position adopted by one local group, the Shannon Farmers’ Protection Association (SFPA), is of particular interest due to the mixture of cultural and material motivations underlying their opposition to relocation, including a perception of unwelcome state interference with private property rights. This is illustrated by the discussion at a meeting in March 1951 where one attendee suggested that, under a relocation scheme, farmers would receive £35 per acre, and is reported to have continued as follows:

He would ask them to consider carefully before giving away their rights for £35 an acre. ‘Remember what Parnell said to the farmers of Ireland—keep a tight grip on your holdings’.Footnote65

Opposition amongst politicians

There was also significant opposition to relocation amongst national politicians who cited the reservations of sections of the community as a primary justification. Importantly, there is evidence that cultural and emotional attachments to place were recognized by politicians as legitimate concerns.Footnote66 However, considering the broader social and political context in which the Shannon relocation scheme arose, it is likely that some politicians’ reservations arose from opposition to land redistribution itself. Specifically, there was, at this time, growing opposition to the continuation of the ILC’s programme of land redistribution and migration due to its financial costs, perceived negative economic effects and the challenge to property rights which it presented. What one critic described as the ‘lavish state expenditure’ required for the ILC to carry out large-scale group migration schemes had led to a shift away from this model during the 1940s.Footnote67 In addition the increasing price of land in the post-War period meant that the budget for buying and redistributing land was increasingly strained. Correspondingly, an editorial in the Offaly Independent in 1957 recognized that the high price of land would be a key challenge to implementing the Shannon relocation scheme.Footnote68

There was also growing concern about the long-term economic effects of land redistribution. From the 1940s onwards, key political figures advocated scaling back land distribution and developing the agricultural economy through the consolidation of large-scale commercial holdings using modern farming methods.Footnote69 This represented a conflict between the traditional welfare agenda of land redistribution and the growth imperative of increasing productivity and agricultural exports. There was also a Fine Gael-led coalition government between 1954 and 1957, a party which had ‘traditionally represented and upheld the interests of big farmers, which it saw as threatened by land distribution’.Footnote70 In conjunction, these issues are likely to have played a role in the lack of practical steps to progress a relocation scheme between 1954 and 1958 and the shift to a scaled-back model thereof.

Advocates of relocation, such as McQuillan, also noted a connection between the willingness of government figures to emphasize people’s attachments to place, and the underlying context of opposition to land redistribution. McQuillan argued that the local community’s supposed reluctance to relocate provided a pretext for the government’s inaction and argued that this reluctance had been overstated. For example, during a parliamentary debate in 1958, McQuillan stated that:

I know many people would not leave, but many of those whose houses and lands were flooded were not asked if they would like to leave. These people are neither vocal nor organised and they would not get up and demand that they should be removed. They were not asked if they would leave.Footnote71

Limitations of the revised relocation scheme

Against this backdrop, the smaller-scale approach to relocation likely represented a pragmatic response to the various pressures upon the ILC and politicians including community opposition, financial pressures and concerns regarding the economic impacts of land redistribution. However, it also attracted significant criticism including that that the number of households included was insufficient. This was attributed by successive government ministers to the unwillingness of local farmers to relocate, but it was argued by others that this was merely an excuse for government inaction. For example, in response to the idea that offers of relocation had been refused, a local farmer was quoted in the Offaly Independent stating that ‘he could supply a list of the people who were not asked’.Footnote73 Thus, this represents a continuation of the debate regarding whether a lack of progress could be attributed to intransigence on the part of the local community or to state inaction.

A further, important critique, linked to the partial disconnection between flood relief and land redistribution, was that the scheme would fail to comprehensively address the risks of flooding because farmland and agriculture would continue to be affected. As reported in the Offaly Independent in 1959, a representative of the SFPA observed that:

Whilst the people whose houses were subject to flooding might get new houses, they still had to earn their living and pay rates from running their farms.Footnote74

In terms of its local legacy, the implications for the local community in Clonown in Co. Roscommon have been discussed by local historian Rosaleen Fallon. From one perspective, she argues that the scheme meant that ‘Clonown was deprived of several families who had been there for generations’.Footnote77 It is, however, worth noting that, without the ILC’s involvement, such outmigration is likely to have taken place in a less coordinated manner. For example, an article in the Shannonbridge Star from 1980 describes the decline and loss of population from the abandoned village of Corrigeen in Co. Offaly, across the Shannon from Clonown, described by the author as a place ‘where man has fought the Shannon and lost’.Footnote78 Fallon also notes that since 1954, flooding has not generally caused the same devastation in Clonown, both because there are fewer houses situated on low-lying land adjacent to the Shannon and due to new opportunities for employment aside from agriculture.Footnote79 However, there is evidence that houses built by the ILC as part of the Shannon Valley Flood Relief Scheme were flooded during winter storms in 2015/16 in a manner which illustrates the difficulty of long-term planning for managed retreat and resilience in an era of rapid climate change.Footnote80

Discussion

The Shannon relocation scheme offers important insights for contemporary literature on resilience, climate adaptation and managed retreat. While managed retreat resonates with resilience perspectives and may offer an effective means of reducing flood risk alongside other co-benefits, it is widely regarded as unpopular and difficult to implement.Footnote81 It is thus useful to understand how, in different social and historical contexts, it has come to be a viable flood risk management strategy and viewed as preferable to conventional engineered flood defences. Thus, similar to other historical literature on adaptation both in Ireland and internationally, the paper challenges narratives of engineered defences as the only possible strategy.Footnote82 Although the concept of resilience is relatively new, the paper highlights the past use of strategies which align with what would now be understood as a resilience-based approach.

In the context of the Shannon scheme, this had diverse origins including, but not limited to, the high cost of engineered defences. In addition, as discussed in previous historically-informed literature on adaptation, the framing of floods and other hazards has varied significantly over time, generating new ‘situational contexts’ in which particular responses are seen as desirable.Footnote83 Importantly, the strategy of relocation as a response to flooding in mid-twentieth century Ireland, through its connection to the ILC’s migration schemes, was linked to a particular understanding of rural flooding as indicative of poor-quality land, deprivation and hardship and, crucially, as the product of inequitable land distribution. It thus went beyond the usual reductive framing of flooding as a wholly ‘natural’ phenomenon by incorporating an understanding of the social and political origins of vulnerability thereto. Notably, this perspective resonates with recent literature in the fields of political ecology and environmental justice which similarly traces inequitable exposure to flooding to historical patterns of land ownership and livelihood opportunities.Footnote84 In terms of its practical outcomes, this framing is important because it led to a recognition of the need for a comprehensive response, in the form of relocation, rather than an immediate technical fix premised solely on engineering expertise.

One key limitation of many forms of climate adaptation is that there is an overriding focus on addressing problems of biophysical exposure to environmental hazards without considering the social and historical context in which adaptation strategies are embedded.Footnote85 Likewise, managed retreat initiatives frequently seek to address immediate problems of exposure to flooding through relocation without considering its long-term negative consequences.Footnote86 Whether or not financial compensation is provided, negative consequences can arise due to a lack of support and/or planning of the relocation process and a consequent inability to find alternative employment, adequate housing and disruption to family and community ties.Footnote87 This is particularly the case where there are close associations between land use and livelihoods such as in the case of rural land and agriculture.Footnote88 There have also been a series of household relocation schemes since the mid-1990s in rural areas in Ireland, in cases where the costs of other flood management strategies have been deemed unjustifiable. These have involved the provision of financial assistance but minimal additional oversight or planning and there is evidence that they may have ultimately exacerbated the vulnerability of those involved.Footnote89 These harmful effects are part of the reason why managed retreat is often opposed by those involved and why it is such a difficult adaptation strategy to implement.Footnote90

The Shannon relocation scheme offers a stark counterexample to these limited forms of adaptation and retreat through the provision of new houses and, in some cases, larger farms and better-quality land. The focus on providing for livelihoods based on farming likely remains relevant in many rural contexts, including in Ireland where the impact of flood management policy on agriculture is an important source of conflict.Footnote91 Similar to the case of Valmeyer, an early example of managed retreat in the USA, the case study provided opportunities for ‘a fresh start’ and ‘a better collective future’.Footnote92 Further, due to offering tangible material benefits and enhanced socio-economic prospects, it garnered support from many (if not all) of those involved and from influential political actors. However, as in the case of other historical analogies for climate adaptation, the similarities between different historical contexts should not be overstated. The precise requirements in terms of additional supports in the present will, in many instances, differ from a context where agricultural land was the key resource for securing one’s livelihood. However, at the level of principle, the case supports the idea put forth in recent literature that retreat should offer opportunities for enhanced community well-being and development,Footnote93 and also illustrates that this could serve to generate political support.

Perhaps one of the most important contributions of the analysis in this paper is to highlight that this comprehensive model of retreat, the material benefits which it provided and the political support which it enjoyed, was a product of the connection between relocation and land reform. This meant that relocation was effectively subsumed within a larger radical, redistributive political project. It is telling, for example, that Wisner et al.’s seminal study of the socio-political origins of vulnerability to environmental hazards categorizes land reform as one of the most radical and transformative approaches to managing vulnerability, albeit without recognizing how this might converge with managed retreat.Footnote94 There are also important parallels with contemporary ideas of ‘transformative adaptation’ referring to ‘radical reform of the economic and political systems’ which challenges the political-economic basis of vulnerability, in this case the unequal distribution of land.Footnote95 It seems clear that equally radical and transformative approaches to adaptation are required to provide meaningful and collective responses to contemporary climate change-related hazards.

Attachments to place, property and land

A further compelling aspect of the case study is the complex and ambiguous role of attachments to place, property and land therein. This is related to the transition from a more wholesale to a scaled-down model of relocation. This further represents a core contribution of the paper, namely to explore the significance of retreat in the context of these attachments and thus to locate or ‘particularize’ retreat in a specific social and historical context.Footnote96 Similar to the findings of previous literature on place, property and retreat,Footnote97 these forms of attachment were tightly interrelated in a manner which reflects the interlinked economic, social and cultural significance of land ownership in twentieth-century Ireland. In a manner which parallels previous literature on place attachment and adaptation,Footnote98 these attachments can also be understood as having acted as both a motivator (through the prospect of acquiring more land) and an obstacle to relocation (through a reluctance to lose one’s home, community and property). This is important in the context of present attempts to envisage positive models of relocation which would offer tangible material benefits because it suggests that these will nevertheless need to account for powerful emotional attachments to place. In response, authors have highlighted the need to centre place in discussions of climate adaptation and to involve communities in decision-making regarding if and how they retreat.Footnote99

The scaled-down model of relocation which was ultimately implemented after 1958 can be understood as a form of such engagement with community concerns in the sense that it emerged in response to opposition arising from place attachment, amongst other factors. It reflected a degree of institutional learning and responsiveness to external pressure on the part of decision-makers and demonstrates that, by incorporating and responding to information from those affected, it was possible to arrive at an effective model of managed retreat which was generally, if reluctantly, accepted. While the revised approach did not wholly address the risks of flooding for livelihoods linked to agriculture, it likely contributed to maintaining the stability of the local community to a greater extent than wholesale retreat. This may have ultimately increased community resilience by leaving intact family and community ties which can be relied upon in times of crisis.Footnote100 Indeed, contemporary accounts of rural Ireland illustrate the continued importance of social and family ties in coping with a crisis and reducing place-based or household vulnerability.Footnote101 From this perspective, the outcome contrasts favourably with recent, ill-conceived examples of managed retreat which have disrupted valuable social networks and thus ultimately undermined resilience.Footnote102

However, it should also be acknowledged that, to some extent, opposition to relocation arose from its transformative character and the fact that it posed a challenge to property rights. This has also been identified as a key obstacle to managed retreat and authors have begun to discuss in what circumstances such challenges might be justified, for example where they concern beachfront second homes owned by the economic elite.Footnote103 In the context of the Shannon scheme, concerns regarding state interference with property rights underlay the opposition of some local farmers and also that of key national political figures given that this scheme occurred at a time when the ILC’s land reform programme was increasingly being questioned including because of the threats which it posed to the interests of large landowners.Footnote104 This further suggests that transformative models of adaptation which seek to redistribute resources and power, such as new progressive approaches to managed retreat, are likely to face resistance from those whose interests they challenge.

Last, a final important point highlighted by the case study is the ambiguous role of discourses of place attachment therein, in the sense that the emphasis on local attachments to place amongst some politicians arguably served as a pretext for opposition to land reform and a means to justify government inaction. This is also relevant to contemporary debates. For example, there is evidence of contemporary demands for financial support for relocation where people have suffered repeat flooding in Ireland, which the national government has been reluctant to provide.Footnote105 This has been justified through powerful narratives regarding attachment to place. When questioned about the limited availability of supports for relocation in Ireland in 2018, the Minister responsible reverted to emphasizing place attachment and community opposition, stating that ‘it is a major issue for people to hand over the keys of their houses and not live where their sons and daughters were reared. Some people do not want to go’.Footnote106 Similarly, evidence from New York post-Hurricane Sandy highlights the deployment of powerful narratives regarding the resilience of New Yorkers and their supposed unwillingness to ‘give up’ as a pretext by those who are opposed to managed retreat due to the loss of opportunities for urban development.Footnote107 Overall, this highlights a need to consider the different functions that ideas and discourses of place attachment can perform and whose interests they serve in different contexts.

Conclusions

The challenges of adapting and building resilience to the effects of climate change, including through large-scale resettlement, pose almost unprecedented societal and political challenges. Managed retreat, amongst available adaptation strategies, is almost uniquely disruptive and its successful coordination demands the marshalling of extensive knowledge and resources to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. In this context, it is useful to explore available historical precedents. Learning from history is a crucial aspect of developing a repertoire of potential responses to climate hazards.Footnote108 Likewise exploring the historical and social contexts in which specific approaches to adaptation and/or retreat have been effective is crucial to challenging the idea of singular, universally applicable adaptation strategies. Although arising in a very different social and political context, the Shannon relocation scheme provides a series of valuable insights regarding the need to build institutional capacity to effect large-scale, collective responses to environmental hazards and to ensure that retreat can offer opportunities for improvements in wellbeing while recognizing the challenges posed by attachments to place. It further highlights that radical and transformative approaches to adaptation are required to fundamentally challenge the root causes of vulnerability, rather than technical fixes which often only alleviate its immediate expression.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers whose insightful and constructive comments contributed to significantly improving the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fiadh Tubridy

Dr Fiadh Tubridy is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the School of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Policy, University College Dublin. Their research focuses on environmental politics and the role of communities in environmental management and planning. Their current project is on co-production and participatory planning in the context of coastal climate adaptation in Ireland while previous projects have focused on green regeneration, public space and infrastructure. Email: [email protected]

Mark Scott

Mark Scott is Professor and Dean in the School of Architecture, Planning & Environmental Policy, University College Dublin. His research is focused on the environmental and sustainability dimensions of spatial planning in both urban and rural environments. His current research projects include work on climate change and coastal communities, built environment climate adaptation and green space and health. Email: [email protected]

Mick Lennon

Dr Mick Lennon researches and teaches in the School of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Policy and the Earth Institute at University College Dublin, Ireland. His work focuses on the intersections between planning and environmental policy with a particular emphasis on green-blue infrastructures, sustainable communities and cultivating resilience in the context of climate change. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Adger, “Social and Ecological Resilience”; Davoudi et al., “Evolutionary Resilience”.

2 Scott, “Living with Floods”.

3 Siders et al., “The Case for Strategic and Managed Climate Retreat”.

4 Ibid.

5 Dannenberg et al., “Managed Retreat”.

6 Siders et al., “The Case for Strategic and Managed Climate Retreat”; Lynn, “Who Defines Whole?”.

7 Devine-Wright, “Think Global”; Clarke et al., “Place Attachment”.

8 Jeffers, “Saving Cork City”.

9 Agyeman et al., “Close to the Edge”.

10 Burley, “Place Attachment”.

11 Devoy, “Coastal Vulnerability”.

12 Agyeman, “Close to the Edge”.

13 O’Donnell, “Don’t Get Too Attached”.

14 Cooper and McKenna, “Social Justice”; Hardy, “Racial Coastal Formation”.

15 Jeffers, “Environmental Knowledge”.

16 O’Neill, “Expanding the Horizons”.

17 Devitt and O’Neill, “The Framing of Two Major Flood Episodes”.

18 Clarke et al., “Place Attachment”; Jeffers, “Saving Cork City”.

19 O’Neill, “Expanding the Horizons”.

20 Anonymized for review.

21 Revez et al., “Risky Policies”.

22 Anonymized for review.

23 Mach et al., “Managed Retreat”.

24 Carey, “Science, Models and Historians”.

25 Parsons and Nalau, “Historical Analogies”.

26 Carey, “Science, Models and Historians”.

27 Adamson et al., “Re-thinking the Present”.

28 Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts.

29 Mitchell, “Looking Backward”.

30 Bankoff, “Remaking the World”.

31 MacAdam, “Historical Cross-Border Relocations”; Wilmsen and Webber, “What Can We Learn”.

32 Rohland, “Adapting to Hurricanes”.

33 David and Mayer, “Comparing Costs”; Greer and Binder, “A Historical Assessment of Home Buyout Policy”; Tobin, “Community Response”; Perry and Lindell, “Principles for Managing Community Relocation”.

34 The newspaper database used was https://irishnewsarchive.com. This provides access to digitized national and local newspapers beginning in the 1700s.

35 Other relevant reports included one produced by the Electricity Supply Board on flooding and hydroelectricity and another by the Office of Public Works on flooding of agricultural land.

36 Braun and Clarke, “Using Thematic Analysis”.

37 Parsons and Nalau, “Historical Analogies”.

38 Fallon, A County Roscommon Wedding; Fallon, “The 1954 Flood”.

39 OPW, “Shannon Catchment”.

40 Mitchell, “Looking Backward”.

41 O’Neill, “Expanding the Horizons”.

42 Finan, Dáil Debates, 20 February 1952.

43 OPW, “Shannon Catchment”.

44 Fallon, “The 1954 Flood”, 82.

45 “Shannon Floods”, Westmeath Independent, Dillon, Dáil Debates, 24 March 1955.

46 Dooley, The Land for the People, 3.

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid.

49 In this paper, the term ‘migration’ is used to refer to land redistribution and resettlement schemes unrelated to flooding carried out by the ILC given that this was how such initiatives were described by those involved and is also the term used in the academic literature on this topic (e.g. Dooley, “The Land for the People”). However, the terms ‘relocation’ and ‘managed retreat’ are used to describe the Shannon case study to align the paper with contemporary literature on flooding and climate change adaptation.

50 Dooley, The Land for the People, 20.

51 Pegley, The Land Commission.

52 Pegley, The Land Commission; Nolan, “New Farms and Fields”.

53 Blowick, Dáil Debates, 6 May 1947.

54 “Shannon Floods”, Freeman’s Journal.

55 McQuillan, Dáil Debates, 5 November 1958.

56 Browne, Against the Tide, 98.

57 Dooley, The Land for the People.

58 Ibid.

59 Fallon, A County Roscommon Wedding, 17, 58.

60 “To Hold Tight to Their Homesteads”, Westmeath Independent.

61 Dillon, Dáil Debates, 24 March 1955.

62 “Migratory Scheme Gets Mixed Reception”, Offaly Independent.

63 Blowick, Dáil Debates, 24 March 1955.

64 Constitution of Ireland, Article 45.2.v.

65 “To Hold Tight to Their Homesteads”, Westmeath Independent.

66 Dillon, Dáil Debates, 24 March 1955.

67 Pegley, “The Development and Consolidation,” 35.

68 “Much to be done”, Offaly Independent.

69 Seth Jones, “Divisions”.

70 Ibid., 104.

71 McQuillan, Dáil Debates, 5 November 1958.

72 “Migratory Scheme Gets Mixed Reception”, Offaly Independent.

73 “Shannon Valley Floods”, Offaly Independent.

74 “All-day Bus Tour of Shannon Valley”, Offaly Independent.

75 Rydell, “River Shannon Flood Problem,” 16.

76 Ó Móráin, Dáil Debates, 4 May 1965.

77 Fallon, “The 1954 Flood,” 88.

78 “The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of”, Shannonbridge Star.

79 Fallon, “The 1954 Flood”.

80 Rosaleen Fallon, email to author, 27 June 2020.

81 Gibbs, “Why is Coastal Retreat So Hard to Implement”.

82 Jeffers, “Environmental Knowledge”.

83 Mitchell, “Looking Backward”.

84 Pelling, “The Political Ecology of Flood Risk”; Walker and Burningham, “Flood Risk”.

85 Gaillard, “The Climate Gap”.

86 Siders, “Social Justice Implications”.

87 Ibid.

88 Dannenberg et al., “Managed Retreat”.

89 Anonymised for review.

90 Gibbs, “Why is Coastal Retreat So Hard to Implement”.

91 Revez et al., “Risky Policies”.

92 Koslov, “The Case for Retreat,” 373.

93 Maldonado, “A Multiple Knowledge Approach”.

94 Wisner et al., At risk.

95 Bankoff, “Remaking the World,” 233.

96 Adamson, “Re-thinking the Present”.

97 O’Donnell, “Don’t Get Too Attached”.

98 Clarke et al., “Place Attachment”.

99 Agyeman et al., “Close to the Edge”.

100 Jeffers, “Double Exposures”.

101 Faulkner et al., “Rural Household Vulnerability”.

102 Siders, “Social Justice Implications”.

103 Hardy, “Racial Coastal Formation”.

104 Seth Jones, “Divisions”.

105 Raleigh, “Buy us Out”.

106 Moran, Seanad Debates, 8 March 2018, Vol.256, No.11.

107 Koslov, “The Case for Retreat”.

108 Marchman et al., “Planning Relocation”.

Bibliography

- Adamson, G. C., M. J. Hannaford, and E. J. Rohland. “Re-thinking the Present: The Role of a Historical Focus in Climate Change Adaptation Research.” Global Environmental Change 48 (2018): 195–205.

- Adger, W. N. “Social and Ecological Resilience: Are They Related?” Progress in Human Geography 24, no. 3 (2000): 347–364.

- Agyeman, J., P. Devine-Wright, and J. Prange. “Close to the Edge, Down by the River? Joining Up Managed Retreat and Place Attachment in a Climate Changed World.” Environment and Planning A 41, no. 3 (2009): 509–513.

- Bankoff, G. “Remaking the World in our own Image: Vulnerability, Resilience and Adaptation as Historical Discourses.” Disasters 43, no. 2 (2019): 221–239.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, no. 2 (2006): 77–101.

- Browne, N. Against the Tide. Dublin: Gill Books, 2007.

- Burley, D., P. Jenkins, S. Laska, and T. Davis. “Place Attachment and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana.” Organization & Environment 20, no. 3 (2007): 347–366.

- Carey, M. “Science, Models, and Historians: Toward a Critical Climate History.” Environmental History 19, no. 2 (2014): 354–364.

- Clarke, D., C. Murphy, and I. Lorenzoni. “Place Attachment, Disruption and Transformative Adaptation.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 55 (2018): 81–89.

- Constitution of Ireland. Dublin: Oifig an tSoláthair, 1937.

- Cooper, J., and J. McKenna. “Social Justice in Coastal Erosion Management: The Temporal and Spatial Dimensions.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 39, no. 1 (2008): 294–306.

- Dannenberg, A. L., H. Frumkin, J. J. Hess, and K. L. Ebi. “Managed Retreat as a Strategy for Climate Change Adaptation in Small Communities: Public Health Implications.” Climatic Change 153, no. 1–2 (2019): 1–14.

- David, E., and J. Mayer. “Comparing Costs of Alternative Flood Hazard Mitigation Plans the Case of Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin.” Journal of the American Planning Association 50, no. 1 (1984): 22–35.

- Davis, M. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World. New York: Verso Books, 2002.

- Davoudi, S., E. Brooks, and A. Mehmood. “Evolutionary Resilience and Strategies for Climate Adaptation.” Planning Practice & Research 28, no. 3 (2013): 307–322.

- Devine-Wright, P. “Think Global, Act Local? The Relevance of Place Attachments and Place Identities in a Climate Changed World.” Global Environmental Change 23, no. 1 (2013): 61–69.

- Devitt, C., and E. O’Neill. “The Framing of Two Major Flood Episodes in the Irish Print News Media: Implications for Societal Adaptation to Living with Flood Risk.” Public Understanding of Science 26, no. 7 (2017): 872–888.

- Devoy, R. J. “Coastal Vulnerability and the Implications of Sea-Level Rise for Ireland.” Journal of Coastal Research 24, no. 2 (242) (2008): 325–341.

- Dooley, T. ‘The Land for the People’: The Land Question in Independent Ireland. Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2005.

- Fallon, R. “The 1954 Flood.” In A Sense of Place: Clonown, a County Roscommon Shannonside Community, edited by M. Fallon, R. Fallon, P. Murray, and S. Ní Mhuirí, 82–89. Athlone: Clonown Heritage, 2006.

- Fallon, R. A County Roscommon Wedding, 1892: The Marriage of John Hughes and Mary Gavin. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2004.

- Faulkner, J.-P., E. Murphy, and M. Scott. “Rural Household Vulnerability a Decade After the Great Financial Crisis.” Journal of Rural Studies 72 (2019): 240–251.

- Gaillard, J.-C. “The Climate Gap.” Climate and Development 4, no. 4 (2012): 261–264.

- Greer, A., and S. Brokopp Binder. “A Historical Assessment of Home Buyout Policy: Are We Learning or Just Failing?” Housing Policy Debate 27, no. 3 (2017): 372–392.

- Hardy, R. D., R. A. Milligan, and N. Heynen. “Racial Coastal Formation: The Environmental Injustice of Colorblind Adaptation Planning for Sea-Level Rise.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 87 (2017): 62–72.

- Interdepartmental Flood Policy Co-ordination Group. Interim Report to Government. Dublin: Office of Public Works, 2016.

- Jeffers, J. M. “Double Exposures and Decision Making: Adaptation Policy and Planning in Ireland’s Coastal Cities During a Boom—Bust Cycle.” Environment and Planning A 45, no. 6 (2013): 1436–1454.

- Jeffers, J. M. “Environmental Knowledge and Human Experience: Using a Historical Analysis of Flooding in Ireland to Challenge Contemporary Risk Narratives and Develop Creative Policy Alternatives.” Environmental Hazards 13, no. 3 (2014): 229–247.

- Jeffers, J. M. “Saving Cork City? Place Attachment and Conflicting Framings of Flood Hazards.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 103 (2019): 26–35.

- Koslov, L. “The Case for Retreat.” Public Culture 28, no. 2 (79) (2016): 359–387.

- Lynn, K. A. “Who Defines’ Whole’: An Urban Political Ecology of Flood Control and Community Relocation in Houston, Texas.” Journal of Political Ecology 24, no. 1 (2017): 951–967.

- Mach, K. J., C. M. Kraan, M. Hino, A. Siders, E. M. Johnston, and C. B. Field. “Managed Retreat Through Voluntary Buyouts of Flood-Prone Properties.” Science Advances 5, no. 10 (2019).

- Marchman, P., A. R. Siders, K. L. Main, V. Herrmann, and D. Butler. “Planning Relocation in Response to Climate Change: Multi-Faceted Adaptations.” Planning Theory & Practice 21, no. 1 (2020): 136–141.

- McAdam, J. “Historical Cross-Border Relocations in the Pacific: Lessons for Planned Relocations in the Context of Climate Change.” The Journal of Pacific History 49, no. 3 (2014): 301–327.

- Mitchell, J. K. “Looking Backward to See Forward: Historical Changes of Public Knowledge about Climate Hazards in Ireland.” Irish Geography 44, no. 1 (2011): 7–26.

- Nolan, W. “New Farms and Fields: Migration Policies of State Land Agencies 1891–1980.” In Common Ground. Essays on the Historical Geography of Ireland, edited by W.J. Smyth and K. Whelan, 296–320. Cork: Cork University Press, 1988.

- O’Donnell, T. “Don’t Get Too Attached: Property–Place Relations on Contested Coastlines.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 43, no. 3 (2019): 559–574.

- O’Neill, E. “Expanding the Horizons of Integrated Flood Risk Management: A Critical Analysis from an Irish Perspective.” International Journal of River Basin Management 16, no. 1 (2018): 71–77.

- Office of Public Works. Shannon Catchment-based Flood Risk Assessment and Management (CFRAM) Study, 2012.

- Parsons, M., and J. Nalau. “Historical Analogies as Tools in Understanding Transformation.” Global Environmental Change 38 (2016): 82–96.

- Pegley, S. “The Development and Consolidation of the Gaeltacht Colony Ráth Chairn Co. Meath.” Master's thesis, Maynooth University, 2007.

- Pegley, S. The Land Commission and the Making of Ráth Cairn, the First Gaeltacht Colony. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2011.

- Perry, R. W., and M. K. Lindell. “Principles for Managing Community Relocation as a Hazard Mitigation Measure.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 5, no. 1 (1997): 49–59.

- Revez, A., J. A. Cortes-Vazquez, and S. Flood. “Risky Policies: Local Contestation of Mainstream Flood Risk Management Approaches in Ireland.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49, no. 11 (2017): 2497–2516.

- Raleigh, D., “‘Buy us Out’ – Flood-Hit Families Call on Govt to Relocate Them to Dry Land.” Irish Examiner, February 26, 2020.

- Rohland, E. “Adapting to Hurricanes. A Historical Perspective on New Orleans from its Foundation to Hurricane Katrina, 1718–2005.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 9, no. 1 (2018): e488.

- Scott, M. “Living with Flood Risk.” Planning Theory & Practice 14, no. 1 (2013): 103–106.

- Seth Jones, D. “Divisions Within the Irish Government Over Land-Distribution Policy, 1940–70.” Éire-Ireland 36, no. 3 (2001): 83–110.

- Siders, A. “Social Justice Implications of US Managed Retreat Buyout Programs.” Climatic Change 152, no. 2 (2019): 239–257.

- Siders, A., M. Hino, and K. J. Mach. “The Case for Strategic and Managed Climate Retreat.” Science 365, no. 6455 (2019): 761–763.

- Tobin, G. A. “Community Response to Floodplain Relocation in Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin.” Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters 80 (1992): 87–99.

- Wilmsen, B., and M. Webber. “What Can We Learn from the Practice of Development-Forced Displacement and Resettlement for Organised Resettlements in Response to Climate Change?” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 58 (2015): 76–85.