ABSTRACT

In 1925, the Central Market of Rabat was built at the outskirt of the medina (the old city) by French Colonial powers (1912-1956). Despite being the only element displayed in colonial maps of the medina, and one of Rabat's current landmarks, the history of the market is still unknown. Drawing on the National Moroccan archives and on colonial postcards, the article explores the historical and urban significance of the Central Market for Rabat colonial and postcolonial history. It argues that the market constitutes a unique architectural and urban case for Rabat as it both challenged and reinforced the colonial agenda. Planning principles like the policy of association, the ‘image of the city' and the ‘dual city' were not only defied by the market, but also by the demolition of the part of the wall in front of it. This revealed the inconsistencies and lack of homogeneity of the colonial approach. Moreover, without the wall, the medina became penetrable by the ‘Ville Nouvelle' (New Town). Engaging with the Central Market is significant for the history of colonial planning, but also for today’s Rabat identity construction, inscribed in 2012 in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites and elected cultural capital in 2022.

Introduction

The construction of a market hall on the edge of Rabat’s medina (traditional or ‘indigenous’ city) in 1924, named the Central Market, may seem somewhat ordinary and uncontentious. However, the story of this market hall and its creation opens up some important discussions about French colonial planning objectives in Morocco (1912–1956) as the process triggered a major controversy among the colonial officials. Besides constructing a new space, the project planned to demolish part of the old Medina wall to make way for the new market, but as we shall see, the decision was not unanimous and instead we observe cracks within the imperial mission and agenda.

This paper investigates the role of Rabat’s Central Market in the colonial and postcolonial history of Morocco. It considers how the market both reinforced and challenged the colonial agenda, making it a unique architectural and urban case for the city of Rabat, the country of Morocco and the colonial doctrines in general.

Rabat was elected the cultural capital of the Islamic world in 2022 by the Islamic World Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.Footnote1 Indeed, Rabat rediscovered and rebuilt a new identity through the project ‘Rabat, City of Light, Moroccan Capital of Culture’ (2014–2018) aimed at enhancing its urban and touristic development.Footnote2 This project revolves around seven main axes, one of them being the enhancement of the cultural and civilizational heritage of the city. This heritage is what allowed Rabat to be inscribed in 2012 in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites, as ‘Rabat, Modern Capital and Historic City: a Shared Heritage’.Footnote3 ‘Shared’ in this context means the exchanges between Western modernism with French colonial urbanism (1912–1956) and Arabo-Islamic principles with Moroccan architecture. This dialogue of the two cultures created a unique city.

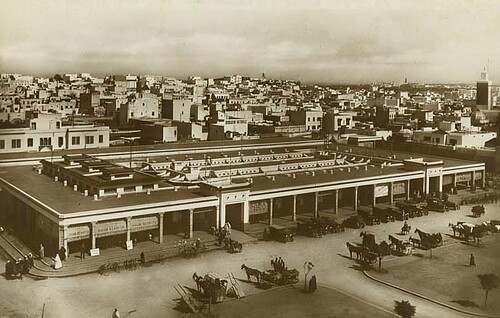

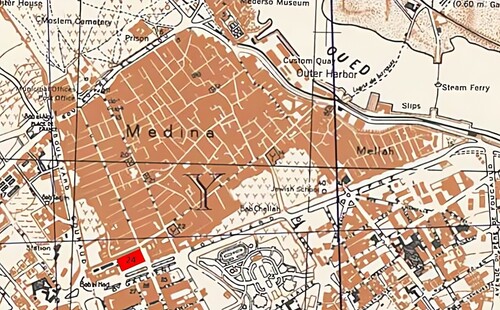

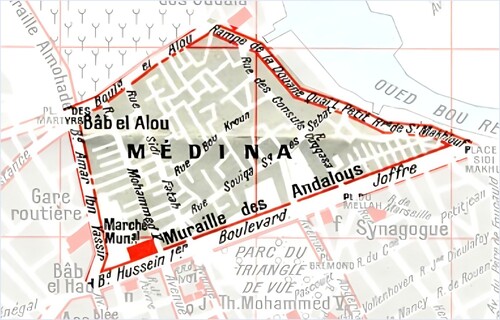

However, this individual colonial and architectural story symbolizing the concept of shared heritage, the Central Market (Marché Central), is still unknown. In Le guide bleu,Footnote4 a French touristic guide to Morocco, published in 1956 (the year of Moroccan Independence), the medina is illustrated as a compact whole, not detailed. Yet, the only distinct element, appearing in red, is the Central Market, showing it as an example of French architecture overseas, and a worthwhile discovery for tourists ().

Figure 1. Map of the medina highlighting the Marché Central.: Source: Le Guide Bleu, 1956, modified by author.

The Market-type is an important architectural form, being an urban public building with strategic heritage significance and social, economic and touristic values. In spite of its importance, research into this space is still new and scarce.Footnote5 But this article is not just part of the literature on markets, it also informs a growing interest in colonial modern heritageFootnote6 and colonial planning practices and ideologies.Footnote7 It aims at giving some nuance to the literature through a specific case study, showing that exceptions existed in these ideologies (which were sometimes presented in a binary manner). Studies on the colonial history of Rabat reveal some curious omissions. They have either focused on the idea of strict separation between the French and Moroccan inhabitants and urban orders,Footnote8 or on the dichotomy between strict preservation of the medina and development of the new colonial districts.Footnote9 There is a clear research gap on the zones of porosity between the medina and the colonial city, therefore, the Central Market seems even more unusual. Only MoulineFootnote10 raised the issue of the relationship between the medina and the colonial city that is yet to be considered.

Equally, no studies have been undertaken on the history of specific architectural buildings for Rabat. The literature focused exclusively on the general urban planning and transformations of the city, through many lenses. It was either the founding role of the landscape in the creation of RabatFootnote11 or the architectural evolution of the colonial district.Footnote12 And it was also the economic and social history of Rabat and its influence on planning,Footnote13 or the history of the city through postcards.Footnote14 Today’s impact of colonial policies on Rabat has also been discussed, but with a broader view of the colonial influence, reminding us of the importance of revisiting colonial history to better understand the current state of the capital city of Morocco.Footnote15

This research draws on data from The National Moroccan Archives, located in Rabat, and from colonial-era postcards from the author’s collection. An archival file is specifically devoted to the Central Market: Box D199. It contains four types of documents: meeting reports or letters from and for various colonial services, extracts from newspapers, architectural and urban plans from the municipality, letters for the General Resident from various bodies. The two services that are mainly present in the archives’ files are the ones involved in urban planning and building of the city, including the medina. The Service des Antiquités, Beaux-Arts et Monuments Historiques (hereafter Service of Antiquities), created in 1912 with the aim to preserve and classify monuments with a very pronounced historical and aesthetic character. The Service des Contrôles Civils et du Contrôle des Municipalités (the Municipal Service), created in 1917, ensured the general maintenance of the medina and its organisation, imposing strict urban regulations to not alter the character of the place. They both supplanted the traditional institutions, of which there are no archival records. There is also a third administrative agency involved in building and planning: Service d’Architecture et d’Urbanisme. However, it focused strictly on the building of the Ville Nouvelle (the ‘New Town’ or colonial city), thus it does not have a role in Central Market’s history, nor a document present in its archives.

Despite the available material in the archives, the history of the market has not been researched. The information was difficult to reconstitute for two main reasons. First, some gaps in knowledge existed for the history before the construction of the market, and data from many places were gathered, such as archives, postcards and interviews with experts in the archives, as the information was scattered. Secondly, reconstituting the documents inside the main files at the archives was time-consuming and delicate, as the story took time to be revealed. Finally, to really understand the uniqueness of the Central Market, the urban principles of French Colonial Morocco needed to be considered. For that, documents from and about the two main protagonist of the first period of colonial Morocco were used: Marshal Hubert LyauteyFootnote16 (1854–1934), the first General Resident in Morocco between 1912 and 1925, and Henri ProstFootnote17 (1874–1959), first urban planner of Morocco between 1913 and 1923.

Firstly, the article identifies the architectural characteristics of the Market and how it attempted to follow the policy of protection established by Lyautey. Then, it reveals that, in fact, the Market breached this same policy, favouring the image of the city instead. Secondly, the debate on the Andalusian wall and the implication of its destruction will be discussed. Finally, the article examines the reasons that led to the market being an exception in French Colonial planning and its policy of association, as it created porosity between the medina and the Ville Nouvelle, or new town.

The Central Market and its architecture: a hybrid creation, a meeting of two worlds

On 13 December 1924, the construction of the market officially began with the pouring of the concrete.Footnote18 Its realization required the development of 63 shops that opened in the summer of 1925.

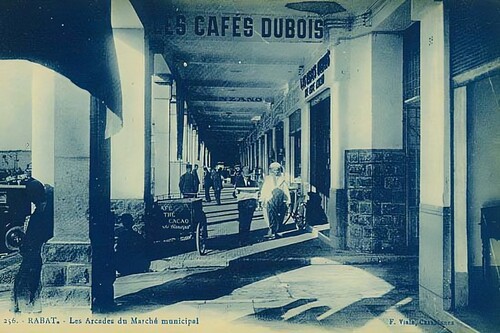

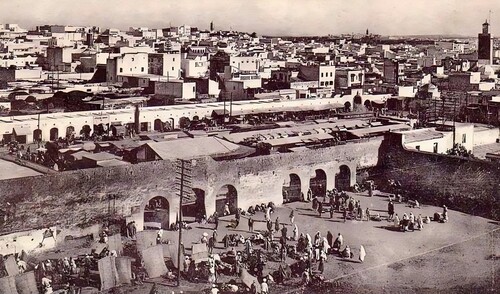

The general aim was to ‘compose an architectural ensemble to reconcile the appearance of the medina’,Footnote19 with an Arabo-Moorish architecture. The Central Market was designed under conditions clearly delimited by the ‘Arrêté du Directeur General de l’Instruction Publique, des Beaux-Arts et des Antiquités relative à l’ordonnance architecturale des immeubles du terre-plein de la place du Marché de Rabat’.Footnote20 A series of strict design rules were imposed, stipulating that the facades had to ‘include a continuous portico running on the public highway […] similar in all respects and in shape, colouring and material […] to the high portico on the long side of the market, towards Souk-Zamara street’. As seen in the postcard (), the portico is prominent, with more than 20 columns on the façade of Boulevard Galliéni. The height of the market did not exceed 6 m, to respect the neighbouring Andalusian wall. The appearance of the market was uniform: the woodwork of the openings had to be painted in green over the entire extent of the facades, the plaster of the walls was painted with whitewash and the wooden fronts of the stores as well as the metal shutters were painted in blue. Inscriptions or signs were only authorized when placed under the porticoes, and lettering had to be white. The regulations for the constructions in the medina of Rabat, adopted in 1919, also influenced the architecture. They were formulated on January the 8th in 1919, in the Article 5 of ‘The General Road and Construction Regulations of the City of Rabat’. The old and new buildings were only permitted to have two floors in addition to the ground floor, for reasons of hygiene and/or aesthetics. The design rules extended beyond the public buildings and set out parameters for housing too. For example, vestibules and outbuildings of the houses, and oblique views of the courtyards were prohibited. The facades had to stay bare, blind and white. The terraces should be cemented and whitewashed, or covered with green tiles.Footnote21 The aim of the rules was to respect a particular and imagined spirit of the idealized medina.Footnote22

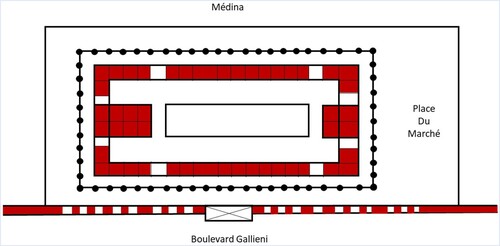

The ‘Place du Marché’ (Market place) is the main entrance (). The facades and the plan represent a blend of two styles: the French Halls (fresh food market) and the Moroccan Qysariya, earning it the name of ‘European Qysariya’ in the press.Footnote23 A Qysariya is defined variously as ‘a public place in which the market is held’, or ‘a square building containing chambers, storerooms, and stalls for merchants’.Footnote24 The French defined it as a collection of shops set up around a large courtyard.Footnote25 The market follows the same functions. As for the European touch, the rectangular shape and covered colonnaded building recall the French Halls. This will to blend the local/indigenous architecture with the architectural principles of the colony was first experimented with by the British. A good example is the Crawford Market in Mumbai, built in 1869, blending Victorian gothic architecture with Indian elements.Footnote26 Lockwood Kipling’s embellishment of the market was essential, with its recognizable decorated inscription and semi-circular bas-reliefs.Footnote27

The Central Market and the policy of association

The architecture of the Market wanted to portray a concern for local culture and architecture, one of the political strategies of Lyautey in Morocco. Indeed, in North Africa, from the conquest of Algeria in 1830 to that of Morocco in 1912, the policy of the countries colonized by France evolved. This development is characterized by a change in attitude towards the native population, which is reflected in the cities. The transition and maturation of urban practices took place in Morocco, with Lyautey, where urban planning has been reformed to move from a ‘style of conqueror’ to a ‘style of protector’.Footnote28 In other words, it went from the ‘policy of assimilation’ to the policy of association.Footnote29

The former represented European cultural dominance with its language, laws and architectural style. In Algeria and Tunisia, this policy demonstrated colonial military prowess and force through the demolition and adaptation of indigenous towns to Europeans needs.Footnote30 In Morocco, Lyautey did not want to repeat these mistakes. ‘It is obvious that nothing has been more fatal for the originality and charm of Algerian cities, of so many cities in the East, than their penetration by modern European installations’.Footnote31

Essential to the colonial ideology in Morocco, the policy of association was an opportunity for the French to trial a new strategy, seen as radical and as a major turning point in French colonial history.Footnote32 The experiment’s main aim was to be conducive to the ‘respect’ and preservation of local culture and ‘indigenous’ society. Lyautey was aware of the political danger posed by the alteration of the essence of the Moroccan way of life after the Algerian and Tunisian cases. The policy of the ‘protector’ served two main purposes. At a national level, Lyautey hoped that it would peacefully ensure the maintenance of France in this territory placed under its domination. The aim was to influence the locals and avoid any revolt on their part. The protectorate wanted to portray a secure population, reflecting the image of a France projecting ‘the protective shadow of its flag’.Footnote33 By being active in the restoration and protection of their culture and their living environment, Lyautey wanted to establish himself as a ‘father figure’. He knew that the European presence was deeply problematic for the Moroccans, and this approach was a symbolic gesture towards placating Moroccan resentment of this invading power. However, it allowed the French to institute an unequal relation with Moroccans. The locals were seen at a distance as the ‘Other’, in a ‘need for their protection’, like children or ‘primitives’, who must be looked after and treated as vulnerable people, unable to manage themselves.

Figure 3. Map of the Central Market. Source: Author, Reconstitution from the map of the National Moroccan Archive, Box D199.

The policy of association was also intended for an international public, to win the French population and government’s support and as a response to the detractors of the Protectorate. Lyautey wanted to show that this new system was a formula of superior domination, erasing the errors of past occupation. This cultural imagery and symbolism of the ‘protection’ was seen by art critic Léandre Vaillat (1876–1952), as an important factor of the colonial presence to make it more acceptable, even more popular for Europeans and more bearable to the locals.Footnote34 Nevertheless, the protectorate was still perceived as a play on words, a shift in vocabulary, or even worse, a label used to mask intentions of selfish conquest. The criticisms addressed to Lyautey are numerous.Footnote35 He was often described as ‘a skilful director, excelling in the art of indoctrinating his visitors, of giving them the illusion of appearances to which reality does not correspond’.Footnote36

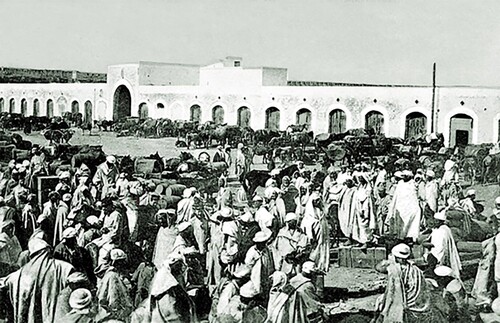

and include people from Rabat, the Rbatis, who are deliberately in these images of the Central Market to portray a sense of French paternalism in bringing modernity to the ‘undeveloped’ medina. But these postcards can also be seen as an exhibition of the exotic: the Moroccans were part of the stage set, fulfilling the role of the ‘primitives’. These images also reveal the admiration that Lyautey had for the ‘exoticism’ of the traditional North African cities.

There was another motive which had never been manifested by any civil or military governor: the desire to preserve the particular aesthetic of the indigenous towns of a country which had reached the 20th century without having been influenced by modern civilization.Footnote37

This policy of the ‘protector’ is the manifestation of a fantasy for the exotic, that should be kept intact, unless it did not fit into the curated image and narrative of the city wanted to be projected by the French. This theme is developed in the next paragraph.

The Central Market and the image of the city

‘European-style buildings [were] prohibited from the medinas, to prevent compromising the picturesqueness of the native quarters’.Footnote38 As Henri de La Casinière, Head of the Service des Contrôles Civils et du Contrôle des Municipalités, explained clearly. And yet, the Central Market is an exception to this rule, and to the policy of Association in general. It was unusual for the French to build a structure at the edge of the Moroccan medina (, under the number 24). This exception needs further examination: what did the market replace? What allowed this exception? And for whom?

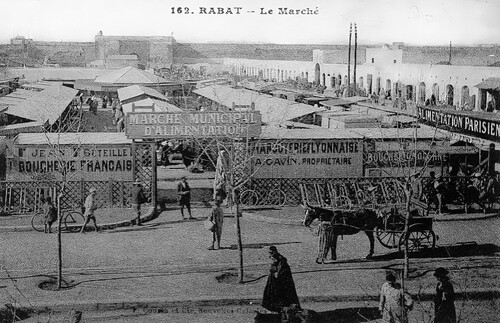

Before the Central Market, the site was occupied by a commercial plaza, called l’Oussaa (‘vastness’ in Arabic), located between the Andalusian wall in the south-west and the series of small arcaded shops belonging to the Hubus of Bab Tben (). The Hubus are an institution of Muslim law that manages the legal acts by which real estate or movable property, donated by the state or by individuals, is put to the benefit of a charitable work or of public utility. One of the few public places in the medina of Rabat, l’Oussaa was used for the ancient practice of ‘the open souk’, an essential activity for the social and economic life of inhabitants, and the gathering space between cities and rural areas. All kinds of animals were sold in ‘Souk Bab Tben’: oxen and sheep on Saturdays, horses and mules auctioned on Sundays; donkeys sold every day, from noon (). Beyond these commercial functions, the open souk (Arab market or bazaar) can also be a space of intangible cultural practices, a place for gatherings and to discuss the social and political life of Rabat. Seen as a threat to the protectorate, these types of open souks were displaced, and even erased, going against the promise of protection of all types of culture cited by Lyautey:

Yes, in Morocco, and it is to our honor, we conserve. I would go a step further, we rescue. We wish to conserve in Morocco Beauty – and it is not a negligible thing. Beauty – as well as everything which is respectable and solid in the institutions and traditions of the country … All of your researches conserve and save, whether it be a question of antiquities, fine arts, folklore, history, or linguistics. We found here the vestiges of an admirable civilization, of a great past. You are restoring its foundations.Footnote39

Figure 7. The Oussaa Plaza with the Hubus shops behind. Source: Postcard, 1910 (Author’s collection).

We can see in the postcard below () the coexistence of these two commercial practices. The angle is the same as the Postcard seen in , showing a clear contrast of the before/after.

But it was only a temporary solution for this place, as the 30th of September, 1922, Henri de La Casinière thought of a competition project for the establishment of a central market. With the expected growth in population, the project was seen as important to answer the city’s needs, ‘without it being too big to ruin the city’s finances’.Footnote40 The city’s inhabitants, rejoiced by this idea, wanted a market ‘worthy of the city of Rabat’, naming it Market of Bab Tben.Footnote41 However, it was not without objection, as the shop tenants in the municipal market protested against its construction, circulating a petition in March 1923, fearing that their jobs were being threatened.Footnote42

Despite the petition and a failed architectural competition,Footnote43 the municipality thought of two solutions to finance and build the market. First, there was a proposal to demolish Dar El Baroud (the Gunpowder Market) to have more space on which to build. The Hubus would then make the site available, to construct 32 shops and run the market with the municipality for a fixed period. The second solution was to use private funding: individual applicants were to construct the shops and pay a fixed service fee, with the lease returning to the city after 20 years. At that time, the European population was increasing and because, it was financially wealthy, the municipality sought to exploit the potential financial gains. The second solution was seen as more fruitful. After numerous meetings in the Secrétariat Général, confronting plans, specifications, reorganizations and discounts on the trade, the municipality was looking for a private entrepreneur. This second proposal failed because the city did not have enough money to build, and private investment from individuals was also limited.Footnote44

Despite the numerous setbacks, the municipality still insisted on the construction of the Central Market, revealing that it was not just for the purpose of reaping financial benefits. The image of the city was of a primordial importance to the French: Morocco was intended to be designed as ‘a matched set of historical and contemporary monuments that together displayed the progress of France’.Footnote45 Modernity and preservation were the two concepts that the country ‘should’ illustrate.

However, the plaza Oussaa, with its bazar, did not fit the ideal picturesque image that the medina should have, according to the French. Even worse, it was seen as disturbing, especially contrasting with the opposite side, Boulevard Gallieni, and its modernity:

Boulevard Gallieni offers itself wide, spacious, endowed with a finished tarring, but when the eye suddenly lands on the left, a sudden and significant blot is the obligatory reflex to sight jumbles of ragged natives, chouaris, donkeys, straw, withered vegetables, smelling full of dirt and lice. In the afternoon, it’s the snake charmers, the storytellers surrounded by the colourful crowd of an undeniable local colour but deeply displaced within the framework of an acute modernism.Footnote46

Preservation of local culture and architecture was not applied when it went against the ‘picturesque image’ that the medina ‘should have’ according to the French Orientalist views, and for two reasons. First, the image of the city was of primordial importance to colonialism: ‘Often conducted under the guise of science and progress, French colonial urbanism was designed to project the authority and power of France in North Africa’.Footnote49 In the interwar period, awakening a patriotic pride was essential, through making French people aware of the ‘merits’ of France overseas. It explains why the ‘Congrès International De L'urbanisme Aux Colonies Et Dans Les Pays De Latitude Intertropicale’Footnote50 was organised in 1932. The preservation of the medina was needed so that the contrast with the new town can be highlighted, showing France colonial power and ingenuity, but also ‘interest’ to preserve the picturesque. Secondly, the outsider gaze, through the European settler and especially through the tourist, was a chief interest in colonies.

These conditions for spatial developments were partly driven by an imagined consumer of le patrimoine marocain [Moroccan’s cultural heritage]: the European settler and tourist, who would appreciate both the historicity of preserved Morocco and the progress of French modern Morocco.Footnote51

The medina was then presented for consumption by the orientalist gazes. The fantasy and curiosity for the Orient, represented with tourism, was perceived as a great source of income. Also, the attraction generated by this ‘image of the city’ allowed Europeans to want to settle in Morocco.

The original architecture of the Central Market was even attractive to Lyautey, who announced, ‘This is a very nice set’. He was pleased to recognize the beautiful arrangement which harmonized with the buildings of Boulevard Gallieni and Avenue Dar El Maghzen.Footnote52 The latter avenue had a symbolic value as it grouped all the administrative activity of the city, being the main avenue of the Ville Nouvelle. This is to show that Lyautey, the precursor of the association policy in Morocco, agreed and was even pleased by this construction which is an exception in the medina.

The Central Market and the ongoing debate on the Andalusian Wall

But the breach in the policy of association did not cease in the construction of the market. To display it to the rest of the city, the municipality decided to demolish the part of the medina’s wall in front of it. However, this plan met with opposition. A constant ideological battle took place between two parties, those in favour of the demolition and those against. The former is represented by the Head of the Service des Contrôles Civils et du Contrôle des Municipalités along with the Europeans shop owners. The latter is mainly defended by one figure: Joseph Borely, the Head of the Service des Antiquités, Beaux-Arts et Monuments Historiques,Footnote53 who advocates for Lyautey’s idea of preservation. The dilemma presented by the wall can be summarized by the sentence: ‘If the maintenance of the Andalusian wall presents real advantages for the artistic safeguard of the medina of Rabat, this measure could not be taken without raising certain difficulties’.Footnote54 Demolition, which will have a length of 80 m, equal to the market, should have been completed no later than February 1st, 1925. But due to various circumstances relating to the execution of the work company, like the moving of the telegraph and telephone wires from the wall, the demolition was delayed.Footnote55 Borely then took the opportunity to submit a proposal advocating for the conservation of the wall.Footnote56 Its examination was the subject of a meeting that took place under the chairmanship of the Service du Contrôle des Municipalités on June 5, 1925. He gave three main arguments. First, the destruction constitutes a serious attack on the principle of separation of the medina and the new towns. Secondly, both the identities of the medina and the colonial city would be violated:

The aesthetic effect produced by the disappearance of the ramparts will not be the happiest: the appearance of the market, thus placed in view on the side of the boulevard Gallieni, will destroy the picturesque point of view born of the contrast between the buildings of the new town and the veining of the ramparts of the medina.Footnote57

The Service du Contrôle des Municipalités and the Service du Contrôle des Habous (Hubus Control) in turn presented several objections to the adoption of Borely’s proposals, each with a financial basis. According to them, the maintenance of the wall will devalue the 15 shops facing Boulevard Gallieni: hence a loss in the total return of the market, which must be supported by the budget of the city of Rabat (approximately 50,000 francs per year). Additionally, the contractor’s specifications provide for the use of the rubble from the wall to level the platform surrounding the new construction. The entrepreneur, deprived of these materials, will therefore be obliged to seek land for backfill which will increase the costs of his business, hence the possible demand for compensation.Footnote59

Borely considered these issues as easily solvable: an agreement with the contractor for the execution of the work, in the hypothesis of maintaining the wall, was the only element needed. As for the devaluation of the shops on Boulevard Gallieni, it would be partially compensated by the relative valuation of the shops located on the other facades, in particular, those which will be on the facade of the ‘Place du marché’. The Head of the Municipal Services still expressed his reservations: shop owners have already discounted this measure for the realization of some commercial projects, and the population was already aware of the destruction.

Citizens joined the ongoing debate: the delay in the work of the market due to the wall angered public opinion, and instilled doubt about a new market for them.Footnote60 The Service des Beaux-Arts, as well as Borely, were highly criticized:

This unstoppable Service considers indeed, it seems, that the wall of the Boulevard Gallieni must be maintained to preserve in Rabat the ‘local colour’. Thus decided a civil servant who one day discovered the qualities of an architect and the talent of an artist.Footnote61

Finally, the Syndicat Francais du Commerce et de l’Industrie (French Syndicate of Commerce and Industry) joined the debate, unanimously announcing: ‘all traders without exception protest against the new project’.Footnote63 They used economic and hygiene arguments: ‘This non-demolition would certainly prevent the rental of part of the shops, and that on the other hand it would not sufficiently ventilate the market installed in a low fund’.Footnote64 Finally, they considered that not only that ‘the part of the wall to be demolished has no artistic cachet’, but that ‘the wall is in such a state of disrepair that it threatens ruin. That accidents for which the administration would carry full responsibility are to be feared’.Footnote65

The wall and the final decision

Under all this pressure, Borely maintained his position: ‘It’s not the architect of the market [M. Michaud] who wants the wall in front of this building to be demolished, it’s the European merchants, […]. Their goal is to make both sides of Boulevard Gallieni a European district’.Footnote66 For him, not only was demolition costly and unnecessary, but unfortunate to the market, and for many reasons. The financial gain is not enough to ‘break the enclosure in which the medina appears like a painting in its frame’. This frame by the walls stayed untouched, and its aesthetic value is undeniable: ‘The design of the old city remains clear, and it is a rather pleasant spectacle that of this Moroccan city contained by a cord of curtains and bastions in all its extent’. He even considers the gaze of the outsider, and the appeal that the separation medina/new town can provide:

The foreigner who visits Rabat, having reached the end of Dar El Makhzen avenue, in this way where European trade is in full swing, can take in a glance a historical view, clear and clear, of the two cities. It is an attraction which, if we know how to keep it, will only gain, in contrast, year after year.Footnote67

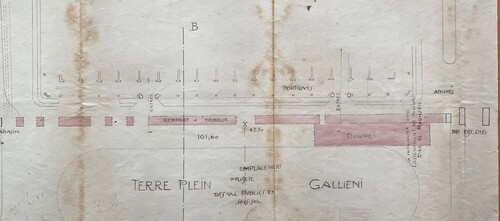

The Service des Beaux-Arts and the Service du Contrôle des Municipalités never came into an agreement, and the solution adopted was the middle way, as seen in the plan below.

The wall (in pink in ) will be developed: it will first be cleaned from the shower baths to the left of Bab Tben, and doors will be pierced in the axis of the market lanes. Even the architect of the project joined the idea, explaining that the wall won’t interfere with pedestrians or cars, once the doors are placed in line with the roads of the market.Footnote70

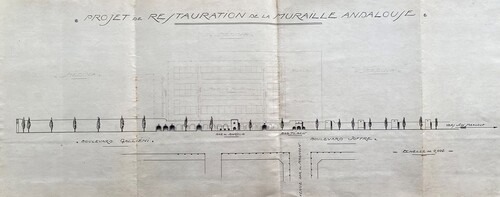

However, in wanting to pierce the door to serve the west alley of the market, the wall collapsed.Footnote71 Borely never gave up, and found a new solution to restore the wall (): the work would take three months, transform the wall into a portico, and the General Secretary granted the funds.Footnote72

Figure 11. Restoration project of the Andalusian wall. Source: National Moroccan Archives, Box D199.

However, this attempt to salvage the old wall failed:

since the old wall that the Resident General would have liked to keep has partly crumbled, when we tried to make openings in it to give air and light to the new market, it is advisable to proceed to its demolition up to Bab Tben.Footnote73

The symbolism of the Wall

The destruction of a part of the Andalusian Wall, alongside its two gates, Bab Tben and Bab Jdid, represents more than just the disappearance of a tangible heritage. As we shall see here, the walls have a high symbolic nature for the medina and its people. Thus, its destruction goes beyond an issue of cultural protection. Moreover, it also goes against the protectorate ideology of the ‘dual city’.

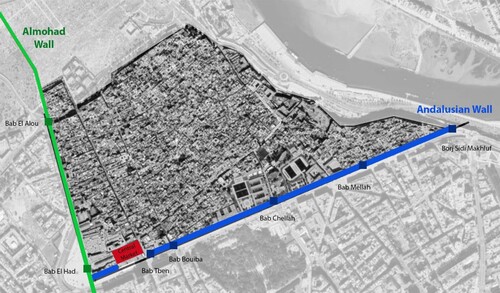

Before the protectorate, the walls were part of the Hubus goods. They surrounded the entire medina and formed an urban rampart materializing the limits between the city and the rural world.Footnote74 In Rabat, two walls surround the medina: the Almohad and the Andalusian, from two specific dynasties (). Their history is significant for the communities. The Almohades, a dynasty of Berber origin, founded by Ibn Toumert, governed both the Maghreb and Al-Andalus between 1121 to 1269. The Andalusian Wall is located between Bab El Had and Borj Sidi Makhlouf, and built in the beginning of the seventeenth century, with the arrival of the Hornacheros and the Moriscos, expelled from Spain after refusing converting to Christianity.

Within the protectorate, the wall represents the clear separation between the medina and the colonial city, materialization of Lyautey’s urban policy: the dual city. Guillaume de Tarde, former General Secretary of the French protectorate in Morocco, summarized it, thus: ‘A European city far enough from the native city not to absorb it, but close enough to it to live in some extent’.Footnote75 For Lyautey: ‘The main thing, on this crucial point, is that there is as little merging as possible between the two city orders’.Footnote76 Two distinct fabrics are juxtaposed on the plan of the city: the core of ‘indigenous’ life (medina), and near it, the Ville Nouvelle. Henri Prost planned this extension for Europeans according to Beaux-Arts concepts of aesthetic beauty.Footnote77 The most modern rules of town planning were applied, reflecting a modern Europe with its concerns on sanitation, hygiene and health, and with its geometric lines, its standardization and its vast open spaces. In Rabat, the materialization of this separation were the Andalusian wall and the Boulevards Joffre and Gallieni. It explains why Borely insisted on the dual city as its main argument against the wall’s destruction, as it would go against the most essential urban principal of French colonial Urban policy in Morocco.

Indeed, the separation was seen as essential, especially for Lyautey, for the following reasons indicated by Prost:

The program, which he (Lyautey) imposed, will characterize them and differentiate them from the cities of our colonies and our protectorates. It includes an essential condition: the complete separation of European and indigenous settlements, and this for political, economic, sanitary, municipal and aesthetic reasons.Footnote78

Seen as having an essential historical and aesthetic character, the walls were classified historical monuments by the Service des Antiquités, Beaux-Arts et Monuments Historiques. Their first action was to legally protect them, alongside their gates, with the Dahir (Regulation) of February 13, 1914, neutralizing all attempts at architectural transformations so long as these had not received prior authorization from the Service of Antiquities. To destroy it, the municipality needed a specific authorization from this latter service and needed first to declassify it. This explains the decisional power that Borely and his peers had, and why protecting the Andalusian wall was seen as a matter of high importance. Then, in 1927, the Service reinforced the Walls with new structure and rehabilitation work, especially their gates.Footnote81

The Central Market and the porosity between medina and Ville Nouvelle

Abu-Lughod used the provocative word ‘Apartheid’ to describe the dual city and the segregation that Moroccans lived, ‘coexisting but not interpenetrating’Footnote82 the Ville Nouvelle. She saw Rabat as even more special than other Moroccan cities as it ‘was the most successful exemplar of French “dual city” planning in Morocco’.Footnote83 The Central Market seems to challenge her view, and in a broader context, to have challenged the colonial mission. It revealed, or even created, porosity between the ‘indigenous’ city and the new town. Wright proclaimed that ‘contact between the races was an inevitable part of colonial life’,Footnote84 but here it is through the story of the Market that we see contact between the two urban orders that was inevitable. With the destruction of the wall, French settlers opened the old city to the new, and the strict separation proclaimed by the French ideology of the dual city was far from being respected. In precedent North African colonies, replacing the inner walls of the medina with European-style buildings was common.Footnote85 But in Morocco, the French wanted a radical change from their precedent urban tactics, which were not respected in the case of the Market. A crack within the policy of association was revealed. Furthermore, an important part of the Ville Nouvelle was present inside the medina through the Market, bringing with it the flow of goods and human resources. Thus, the Central Market constitutes a unique case in French Colonial History in Rabat, even Morocco. The combination of three factors allowed this interpenetration to happen.

First of all, even if Lyautey wanted to convey the image of the protection of the ‘indigenous’ and their culture as the priority, it was colonial capitalism that prevailed. As clearly seen in the debate on the wall, financial arguments were at the heart of the discussion, even for Borely, who militated for its preservation.

The promotion of tourism was the priority for the preservation, as it constitutes an advantageous source of income:

The picturesqueness of the medina in its intact enclosure constitutes a wealth for the tourist economy which it is in our interest not to diminish, it seems that by keeping the wall intact, the city will have to make a good financial operation.

Adding: ‘The economy of tourism here seems to take precedence over the particular interest of a small number of individuals. Should we compromise the architecture of a city to promote a display of goods’.Footnote86 He followed Lyautey’s ideas:

[The preservation of the native towns is] not only a question of aesthetic satisfaction, but a duty of the state. Since the development of tourism on a large scale, the preservation of the beauty of the country has taken on an economic interest of the first order.Footnote87

But with the construction of the market, it was not a question of preserving the native town, as they saw the ‘empty’ space of the Oussaa plaza as an opportunity to build and to earn, rather than seeing it as a space of intangible cultural practices that needed protection. It was quite the opposite: this practice not only allowed for Rbatis’ meetings that was frowned upon, but it went against the valuable image of the city, seen essential by Lyautey for the influence of France overseas:

Since the recent, intense development of large-scale tourism, the presentation of a country’s beauty has taken on an economic importance of the first order. To attract a large tourist population is to gain everything for both the public and the private budgets.Footnote88

Second of all, the debate on the wall revealed the inconsistencies of views and the lack of unanimity between the different departments. This is what weakened the policy of preservation and permitted the destruction of the wall and the interpenetration of the two urban orders. At first, both the Beaux-Arts and the municipality seemed to agree on the strict preservation of the medina:

Not only was new construction separated sharply from the old medinas but also very strict watch was kept by the Service des Beaux-Arts and the Services Municipaux so that nothing would alter the traditional character and coherence of these cities of the Maghrib.Footnote89

Therefore, the destruction of the wall, plus the construction of the market, constituted an exception to this myth of the static and untouchable medina. With the financial help of the Hubus, both the Departments saw an opportunity for economic benefits with the market. But when it comes to the wall, the colonial administration split into half: Borely, representing the Beaux-Arts, and the municipality, represented by the municipal councillors. Prost selectively chose them among French elite society.Footnote93 They privileged financial arguments over the protection of a culture they did not value as much, as commerce was perceived as the primary reason for colonization: ‘Almost all colonies begin with trade: colonization only comes later […] They were conquered because of the outlets they offered’.Footnote94 Borely followed the steps of Lyautey, where preserving the wall is not only a way to respect the culture but a mean to financial benefits as well in the long-term through tourism. Borely emphasized this lack of concern for locals and their history within the debate:

And the Rbatis, the real city dwellers of the medina, are they strangers to the question? If in the extent of the country, we can consider ourselves at home, should we not behave like guests in the old Moroccan cities? Are you certain that, without displeasure, the Rbatis see us taking the initiative to dismantle the wall built by their ancestors for a rather vague reason of mercantile interest which hardly affects them.Footnote95

Finally, the third aspect that allowed the porosity, is the location of the central Market: in the outskirts of the medina, in front of the Ville Nouvelle. In the beginning of the protectorate, in order to mark the separation more clearly, the planners wanted to create a cordon sanitaire around the medina, meaning a greenbelt of non-constructible land. However, they did not succeed as the land had already been bought. With the arrival of Prost, he could establish a zone non-aedificandi of 250 m in width outside the walls, despite the protest of the European purchasers, and justified as being needed for military reasons.Footnote97 Plus, Europeans, mainly shop owners, tended to settle in the medina, despite Prost and Lyautey’s intent to keep the separation strict:

These businessmen were a potential obstacle to our programme’s goal of separating Europeans from Moroccans, and we have had to provide strong incentives to counterbalance [their tendencies to settle inside the walls] … Therefore, it was necessary to set up fast and convenient means of communication between the modern city and the native city on which the former was more or less parasitic.Footnote98

Conclusion

‘Promoting modern improvements without disrupting national tradition’Footnote99 outlines the political strategy of French colonialism. Yet, the Central Market defies it, as it removed a national practice, the souk, to build a modern commercial architecture inside the traditional city, making it the only ‘shared heritage’ inside the medina. The UNESCO World heritage Centre label intended for the city of Rabat and its various dialogues between civilizations can apply as well to this single entity alone. Even its architecture showed a meeting of two worlds, between the French market halles and the Moroccan Qysariya.

Plus, the architecture of the Market aimed to show regard to the ‘local colour’, a characteristic of the policy of association, core of the French colonial ideology in Morocco. Indeed, it entailed the strict preservation of any cultural form of the medina, and if a renovation needed to be completed, it must be in coherence with it. However, the policy of the ‘protector’ was not applied when an aspect of culture did not fit within the ideas of beauty and exoticism of the medina that the French wanted to portray. A great emphasis was placed upon the image of the city as it needed to reflect nationally and internationally the urban principles of hygiene, order and modernity of French colonial urbanism. This explains why the plaza Oussaa, with its souk, was perceived as ‘ridiculous’ and ‘dangerous’.Footnote100 The necessity for its replacement allowed the municipality to persevere for the creation of the market, despite the challenges encountered. In the end, an agreement has been reached between the municipality and the Hubus to finance the construction.

Furthermore, building the market was not the only concern. To enhance it and multiply its profits, colonial administrators destroyed a section of the Andalusian wall in front of it, breaching the policy of association again, for a pure matter of financial interest.Footnote101 The municipality, alongside French shop owners and citizens, campaigned for the opening of the market to the new city. They disregarded the wall as an important entity to be safeguarded, despite its legal protection by the Service des Antiquités, Beaux-Arts et Monuments Historiques. The latter, represented in the debate by Joseph Borely, militated for the protection of the wall, arguing that its destruction constitutes a serious offence on the principle of the dual city. But in the end, both parties have favoured financial benefits, either through the market directly or through the industry of tourism.

The lack of unanimity between the services is one of the factors that allowed the medina to be porous to the Ville Nouvelle, challenging the ‘ideal’ urban planning of the dual city according to French colonizers. The colonial ‘view point’ was neither homogenous nor consistent. The wall was either seen as part of Moroccan beauty to be preserved, and as a symbol of the ‘dual city’, or the wall was perceived as an obstacle to the valuation of the market and the enrichment of its merchants. Two other factors were in play: the location of the Market in the outskirt of the medina, and the willingness of French merchants to work inside the traditional city.

Crossing the history of the ongoing debate on the wall with the history of colonial Rabat/Morocco has made it possible to reveal incongruencies and inconsistencies in the discourse of colonial ideology. Indeed, the article relied on a micro-historical approach, the history on the finest scale, following the scholarship undertaken by GarretFootnote102 and Jelidi.Footnote103 They respectively studied the Central Market of Casablanca and the building of the colonial city of Fez, using archival material to show the day-to-day negotiations between the different local actors that shaped the urban space. This method allows us to discover the reality of colonial practices on the ground. However, the majority of writings on the first period of colonial Morocco (1912–1925) were done on a macro scale, highlighting the work and ideologies of Lyautey and Prost.Footnote104 The macro level of history portrays a colonial urban ideal, reflecting the uniformity and the consistency of the colonial doctrines. Whereas the micro scale is what allows us to reveal the inconsistencies and the exceptions, but this method is still lacking in the colonial literature. For example, Garret showed that the Market of Casablanca revealed the role of private interests in the shaping of the city, despite Lyautey’s rules. But it is still not as unique as that of Rabat: indeed, it was also built in the main boulevard of the colonial city, but on empty land, not inside the medina and, therefore, replacing a space of long-standing traditions, and without demolishing the wall.

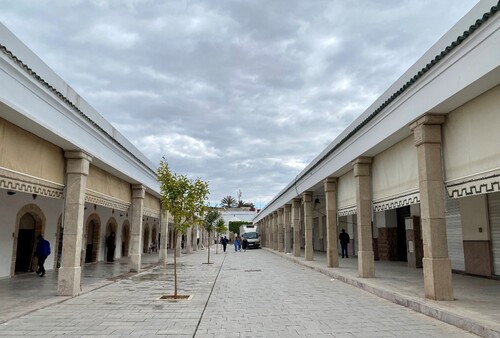

Today, the Central Market has undergone a long process of revitalization from 2018, and it has just reopened in Mars 2022 (). The market was managed from its creation by the municipality. From 2015 onwards, with the new territorial division, the market went under the municipality of Rabat-Sale-Kenitra, under the supervision of the Ministry of the Interior. It has a control office dedicated to the market, managing the commercial activity and controlling the quality of the imported and local goods. However, its renovation was done by an anonymous company, the Société Rabat Région Aménagements, created in November 2014 to ensure the management and execution of ‘Rabat city of light, Moroccan capital of culture’ programme.

A budget of 25 million dirhams (2,3 million dollars) was dedicated for the renovation, both within the market and in the areas surrounding it.Footnote105 Architectural landmark in Rabat, economic institution and the main entry point to the medina, the market is indeed essential. All kinds of food products are sold there, including vegetables, meat and fish. As the Moroccan press outlines:

This century-old building is still a popular destination for everyday shopping or for a singular purchase. The seasons change and the clientele remains loyal, sometimes out of habit, sometimes out of a demand for quality. Everyone is nevertheless in agreement in qualifying the central market as essential.Footnote106

We must once again insist on the need to adopt a dynamic vision with regard to this protection, aiming to integrate our heritage into our development projects and not only embalm it in a vision of sanctification of the past … This requires building solid bridges between this civilizational legacy and the creations of contemporary man, because the heritage of tomorrow is what we invent today. It is therefore imperative to make heritage a shared space for dialogue between civilizations, generations and eras.Footnote107

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, the author wishes to kindly thank her supervisor, Professor Iain Jackson, for his constant guidance throughout the research. The author also wishes to thank the University of Liverpool for funding the research, and the Moroccan National Archives for their precious help and documentation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rim Yassine Kassab

Rim Yassine Kassab is a fully-funded PhD Student at University of Liverpool and a Tutor at the School of Architecture of Manchester. Her research is focused on North African old cities, called medina, and on how the national and international bodies are rethinking them and transforming them. Her interest lies in the alternate narratives at play in the medina, between the lived narratives of the communities and the institutional ones.

Notes

1 ICESCO, “Rabat capitale de la culture 2022.”

2 https://lumierabat.wordpress.com/; Quid, https://quid.ma/a-la-une/rabat-ville-lumiere,-capitale-marocaine-de-la-culture,-une-nouvelle-dynamique-socio-economique.

3 UNESCO, Rabat, capitale moderne et ville historique.

4 Sefrioui and Besancenot, Le guide bleu: Maroc.

5 Martin, “The Pathogenic City”; Dimitrovski and Vallbona, “Urban Food Markets in the Context of a Touristic Attraction”; Home, Of Planting and Planning; and Nettels, “The Place of Markets in the Old Colonial System.”

6 Avermaete, Karakayali, and Von Osten, Colonial Modern; and Demissie, Colonial Architecture and Urbanism in Africa.

7 Njoh, French Urbanism in Foreign Lands; Njoh, Planning Power; Bigon, A History of Urban Planning; and Demissie, Colonial Architecture and Urbanism in Africa.

8 Abu-Lughod, Rabat: Urban Apartheid.

9 Wright, “Tradition in the Service of Modernity”; and Théliol, “Aménagement et Préservation de La Médina de Rabat.”

10 Mouline, “Architecture Métissée et Patrimoine.”

11 Bennani, “Le rôle fondateur du paysage dans la création des villes coloniales marocaines.”

12 Dupont, Architecture et urbanisme à Rabat et Casablanca.

13 Munoz, Monographie historique et économique d’une capitale colonial.

14 Malka, Rabat hier et aujourd’hui.

15 Wagner and Minca, “Rabat Retrospective.”

16 For a recent study on Lyautey’s biography and ideological legacy on Morocco: Minca and Wagner, Moroccan Dreams.

17 For a biography of Prost: Frey, “Henri Prost, parcours d’un urbaniste discret” or for an overview of his work in Morocco: Marrast, “Maroc” in L’oeuvre d’Henri Prost.

18 The Construction of the Market, Journal Article from L’Echo du Maroc, December 13, 1924, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

19 “Order of the Director General of Public Instruction, Fine Arts and Antiquities.”

20 Ibid.

21 Théliol, “Aménagement et Préservation de La Médina de Rabat Entre 1912 et 1956.”

22 Wright, “Tradition in the Service of Modernity,” 304.

23 The Kessaria, October 24, 1923, Journal Article from Le Nord Marocain, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

24 Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa, 350.

25 The Kessaria, October 24, 1923, Journal Article from Le Nord Marocain, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

26 Chopra, A Joint Enterprise.

27 Bryant, “Kipling as a Sculptor,” 82.

28 Béguin, Arabisances.

29 Knight, “French Colonial Policy the Decline of ‘Association’”; Betts, Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory; and Deming, “The ‘Assimilation’ Theory in French Colonial Policy.”

30 Njoh, French Urbanism in Foreign Lands.

31 Lyautey, “Conférence à l’Université des Annales,” 450.

32 Njoh, French Urbanism in Foreign Lands, 149; and Mouline, “Architecture Métissée et Patrimoine,” 717.

33 Lyautey, “Ouverture de la première conférence Nord-Africaine,” 384.

34 Vaillat, Le périple marocain, 55.

35 Beguin, Arabisances; Knight, Morocco as a French Economic Venture; and Abu-Lughod, Rabat: Urban Apartheid.

36 Lyautey, “Inauguration du grand port de Casablanca,” 387.

37 Henri Prost, “Le développement de l'urbanisme dans le protectorat du Maroc,” 65.

38 De La Casinière, Les Municipalités marocaines, 96.

39 Lyautey, “Speech Delivered at the Congress of Moroccan Higher Education,” 340–1.

40 Competition for the Establishment of a Market in Bab Tben, Official Manuscript of the Head of Municipal Services, September 30, 1922, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

41 Construction of the Kissaria on Boulevard Galliéni in Rabat, Journal Article from Le Nord Marocain, April 12, 1923, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

42 Ibid.

43 Competition Project for the Rehabilitation of the Bab Tben Market, Official Manuscript of the Head of Municipal Services, April 24, 1923, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat; Development Plan for the Kissaria of Boulevard Galliéni, Note for the head of the civil control and municipal control service by the General Secretariat of the protectorate, June 25, 1923, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

44 A Monumental Mistake, Journal Article from L’Echo du Maroc, October 24, 1923, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

45 Wagner and Minca, “Rabat Retrospective,” 3017.

46 First Impressions, Journal Article from La Vigie Marocaine, November 24, 1923, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid.

49 Njoh, French Urbanism in Foreign Lands, 140.

50 Royer, Congrès International De L'urbanisme Aux Colonies.

51 Wagner and Minca, “Rabat Retrospective,” 3017.

52 Note from Lyautey to the Secretariat of the Protectorate, the Head of the Fine Arts and Historic Monuments Department and the Director of the Civil Controls and Municipalities Control Department, September 30, 1925, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

53 For more information, see: Théliol, “Aménagement et Préservation de La Médina de Rabat Entre 1912 et 1956.”

54 Conservation of the Andalusian Wall, Note from the Head of Municipal Services for the Resident General, June 10, 1925. National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

55 Will We Have a Market? Journal Article from Le Nord Marocain, June 7, 1925, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

56 The Planning of Bab Tben’s Market, Note on the meeting of June 5, 1925 at the General Secretariat of the Protectorate by the Head of Municipal Services, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid.

59 The Planning of Bab Tben’s Market, Note on the meeting of June 5, 1925 at the General Secretariat of the Protectorate by the Head of Municipal Services, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

60 Will We Have a Market? Journal Article from Le Nord Marocain, June 7, 1925. National Moroccan Archives, Box D199. Rabat.

61 Ibid.

62 Ibid.

63 Letter from the French Syndicate of Commerce and Industry to the Secretary General of the Protectorate Government, July 31, 1925, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid.

66 Borely, Joseph. 1925. Note on the Andalusian Wall. Box D199. National Moroccan Archives, Rabat.

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid.

69 Ibid.

70 Ibid.

71 Will We Have a Market? Journal Article from Le Nord Marocain, June 7, 1925. National Moroccan Archives, Box D199. Rabat.

72 Note from the Head of the Fine Arts and Historic Monuments Department to the Director of the Civil Controls and Municipalities Control Department, September 2, 1925, National Moroccan Archives, Box D199, Rabat.

73 Note from Lyautey to the Secretariat of the Protectorate, the Head of the Fine Arts and Historic Monuments Department and the Director of the Civil Controls and Municipalities Control Department, September 30, 1925. National Moroccan Archives, Box D199. Rabat.

74 Wilbaux. La médina de Marrakech, 322.

75 De Tarde, “L’Urbanisme au Maroc: Rapport general,” 30.

76 Lyautey, “Conférence à l’Université des Annales,” 453.

77 Njoh, French Urbanism in Foreign Lands, 140.

78 Prost, “Le développement de l’urbanisme dans le protectorat du Maroc, de 1914 à 1923,” 60.

79 Prost, Henri. Habitation et urbanisme en Afrique du Nord, Chapitre C, Dossier 13-02, Cote 343-AA-3/4, Fonds Prost, Archives Chaillot, Paris, 15.

80 Abu-Lughod, Rabat: Urban Apartheid, 175.

81 Ibid.

82 Ibid., 151.

83 Ibid., 155.

84 Wright, “Tradition in the Service of Modernity,” 309.

85 Njoh, French Urbanism in Foreign Lands, 144.

86 Borely, Joseph. 1925. Note on the Andalusian Wall. Box D199. National Moroccan Archives, Rabat.

87 Lyautey, “Conférence à l’Université des Annales,” 450.

88 Ibid.

89 De La Casinière, Les Municipalités marocaines, 96.

90 Vaillat, “L’esthétique aux colonies,” 23.

91 Wright, “Tradition in the Service of Modernity,” 304.

92 Pelletier, “Valeurs foncières et l'urbanisme au Maroc,” 34.

93 Vaillat, Le périple marocain, 39.

94 Chailley-Bert, La France et la plus grande France, 97.

95 Borely, Joseph. 1925. Note on the Andalusian Wall. Box D199. National Moroccan Archives, Rabat.

96 Note from Lyautey to the Secretariat of the Protectorate, the Head of the Fine Arts and Historic Monuments Department and the Director of the Civil Controls and Municipalities Control Department, September 30, 1925. National Moroccan Archives, Box D199. Rabat.

97 Henri Prost, cited in Pelletier, “Valeurs financières et urbanisme au Maroc,” 26.

98 Prost, “Le développement de l’urbanisme dans le protectorat du Maroc, de 1914 à 1923,” 60.

99 Wright, “Tradition in the Service of Modernity,” 315.

100 First Impressions. Journal Article from La Vigie Marocaine. November 24, 1923. National Moroccan Archives, Box D199. Rabat.

101 Section of the Rampart to be Demolished. Note and plans by the Municipal Services, September 29, 1924. National Moroccan Archives, Box D199. Rabat.

102 Garret, “Casablanca Confrontée à l’Etat Colonisateur, Aux Colons et Aux Élites Locales.”

103 Jelidi, Fès, la fabrication d'une ville nouvelle.

104 Marrast, “Maroc”, L’oeuvre d’Henri Prost; Jactel, “Veilles villes et cites modernes au Maroc”; Joyant, “L'urbanisme au Maroc”; Descamps, L'architecture moderne au Maroc; Descamps, “L'urbanisme: L'oeuvre de M. Prost”; Taylor, “Planned Discontinuity: Modern Colonial Cities in Morocco”; Residence Générale de la Republique Francaise au Maroc, La renaissance du Maroc:Dix annees de protectorat, 1912–1922; and Royer, L’urbanisme aux colonies.

105 El Ouad, “Rabat, Marché central: Réouverture après 3 ans d’attente,” https://www.lopinion.ma/Rabat-Marche-central-Reouverture-apres-3-ans-d-attente_a23418.html.

106 Ibid.

107 King Mohammed VI of Morocco, extract from his message at the 23rd session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee in 1999.

108 Mauran, Le Maroc d’aujourd’hui et de demain, 43.

109 Radoine, “Tradition and Myth in the Medina.”

Bibliography

- Abu-Lughod, Janet L. Rabat: Urban Apartheid. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980.

- AlSayyad, Nizzar. Forms of Dominance: On the Architecture and Urbanism of the Colonial Enterprise. Aldershot: Avebury, 1992.

- André-Julien, Charles. Le Maroc face aux impérialismes. Paris: Edition du Jaguar, 1978.

- Avermaete, Tom, Serhat Karakayali, and Marion Von Osten, eds. Colonial Modern: Aesthetics of the Past, Rebellions for the Future. London: Blackdog, 2010.

- Béguin, François. Arabisances: Décor architectural et tracé urbain en Afrique du Nord, 1830–1930. Paris: Bordas Edition, 1993.

- Bigon, Liora. A History of Urban Planning in Two West African Colonial Capitals: Residential Segregation in British Lagos and French Dakar (1850–1930). London: Edwin Mellen Press, 2009.

- Bohbot, Jescie-Lynn. Colonial Space in Morocco. College Park: Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, 2011.

- Brown, L. C. “The Many Faces of Colonial Rule in French North Africa.” Revue de l’Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée 13, no. 1 (1973): 171–191.

- Brunschwig, H. French Colonialism 1871–1914: Myths and Realities. New York: Frederick Praeger, 1964.

- Chailley-Bert, Joseph. La France et la plus grande France. Paris: Revue politique et parlementaire, 1902.

- De La Casinière, Henry-Claude. Les Municipalités marocaines: leur développement, leur législation. Casablanca: Imprimerie de la Vigie marocaine, 1924.

- De Lamazière. “Les méthodes coloniales Françaises.” France-Maroc: revue mensuelle illustrée, No5 (05/1920): 103–104.

- De Tarde, Guillaume. “L’Urbanisme au Maroc: Rapport general.” In L’urbanisme aux colonies et dans les pays tropicaux. Vol. 1. La Charité-sur-Loire: Delayance, 1932.

- Demissie, Fassil, ed. Colonial Architecture and Urbanism in Africa: Intertwined and Contested Histories. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009.

- Demissie, Fassil. Colonial Architecture and Urbanism in Africa: Intertwined and Contested Histories. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Dimitrovski, Darko, and Montserrat Crespi Vallbona. “Urban Food Markets in the Context of a Tourist Attraction – La Boqueria Market in Barcelona, Spain.” Tourism Geographies 20, no. 3 (2018): 397–417.

- El Ouad, Achraf. “Rabat/Marché central: Réouverture après 3 ans d’attente.” L’opinion, January 27, 2022. https://www.lopinion.ma/Rabat-Marche-central-Reouverture-apres-3-ans-d-attente_a23418.html.

- Extract from the message of His Majesty King Mohammed VI, May God Assist Him, to participants at the 23rd session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee. Marrakech, 1999.

- Frey, Jean-Pierre. “Henri Prost (1874–1959), parcours d’un urbaniste discret (Rabat, Paris, Istanbul …).” Urbanisme, no 336 Utopie(s), mai-juin 2004.

- Garret, Pascal. “Casablanca confrontée à l’Etat colonisateur, aux colons et aux élites locales: essai de micro histoire de la construction d’une ville moderne.” In La ville coloniale au XXe siècle: d’un sujet d’action à un objet d’histoire, edited by Hélène Vacher, 27–39. Mainsonneuve et Larose, 2005.

- Girardet, R. L’idée coloniale en France de 1871 à 1962. Paris: La table ronde, 1972.

- Gnedash, Chirtina. “Colonial Legacies in Morocco’s Urban Spaces: Policies of Modernization and Preservation.” Capstone Projects and Master’s Theses, 2018.

- Home, Robert. Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Ibn Battuta. Travels in Asia and Africa. Oxon: Routledge, 1929.

- ICESCO. “Rabat proclamée capitale de la culture dans le monde islamique au titre de 2022.” ICESCO, November 5, 2021. https://www.icesco.org/fr/2021/11/05/rabat-proclamee-capitale-de-la-culture-dans-le-monde-islamique-au-titre-de-2022/.

- Jelidi, C. Les villes maghrébines en situation coloniale: XIX–XX siècles. Urbanisme, architecture, patrimoine. Contribution au renouveau historiographique par l’archive, 2010.

- Jelidi, Charlotte. Fès, la fabrication d'une ville nouvelle (1912–1956). Lyon: ENS Éditions, 2012.

- Lyautey, Hubert. “Conférence à l’Université des Annales, Paris, 10 Décembre 1926.” In Paroles d’action: Madagascar, Sud-Oranais, Oran, Maroc (1900–1926). Paris: Librairie Armand Colin, 1927.

- Lyautey, Hubert. “Inauguration du grand port de Casablanca, Rabat, le 4 Avril 1923.” In Paroles d’action: Madagascar, Sud-Oranais, Oran, Maroc (1900–1926). Paris: Libraire Armand Collin, 1927.

- Lyautey, Hubert. “Ouverture de la première conférence Nord-Africaine, Alger, le 6 Février 1923.” In Paroles d’action: Madagascar, Sud-Oranais, Oran, Maroc (1900–1926). Paris: Libraire Armand Collin, 1927.

- Lyautey, Hubert. “Speech Delivered at the Congress of Moroccan Higher Education, Rabat, May 26, 1921.” In Paroles d’action: Madagascar, Sud-Oranais, Oran, Maroc (1900–1926). Paris: Libraire Armand Collin, 1927.

- Marras, Jean. L’oeuvre de Henri Prost. Architecture et urbanisme, Académie d’Architecture. Paris: Imprimerie du Compagnonage, 1960.

- Martin, Samantha. “The Pathogenic City: Disease, Dirt and the Planning of Dublin’s Wholesale Fruit and Vegetable Markets.” Planning Perspectives 37, no. 1 (2022): 149–168. doi:10.1080/02665433.2021.2011775.

- Mauran, Louis. Le Maroc d’aujourd’hui et de demain: Rabat, études sociales, impressions et souvenirs. Paris: H.Paulin, 1912.

- Montagnon, P. Dictionnaire de la colonisation française. Paris: Pygmalion, 2010.

- Morris, Jan. The Stones of Empire: The Buildings of the Raj. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993.

- Mouline, Said. “Architecture Métissée et Patrimoine.” In Old Cultures in New Worlds. 8th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium. Programme Report, 715–722. Washington, DC: USICOMOS, 1987.

- Nettels, Curtis. “The Place of Markets in the Old Colonial System.” The New England Quarterly 6, no. 3 (1933): 491–512. doi:10.2307/359554.

- Njoh, Ambe J. “Colonial Philosophies: Urban Space, and Racial Segregation in British and French Colonial Africa.” Journal of Black Studies 38, no. 4 (March 2008): 579–599. doi:10.1177/0021934706288447.

- Njoh, Ambe J. French Urbanism in Foreign Lands. New York: Springer, 2015. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25298-8.

- Njoh, Ambe J. Planning Power – Town Planning and Social Control in Colonial Africa. London: UCL Press, 2007.

- “Order of the Director General of Public Instruction, Fine Arts and Antiquities Relating to the Architectural Arrangement of Buildings on the Median of the Central Market in Rabat.” Bulletin officiel du Maroc, n° 661 (June 4, 1925): 1081–1082.

- Pabois, Marc. Architecture coloniale et patrimoine: l’expérience francaise. Paris: Somogy editeur d’art, 2005.

- Pelletier, Pierre. “Valeurs financieres et urbanisme au Maroc (I).” Bulletin économique et social du Maroc, no. 19 (1955).

- Platania, M. “L’historiographie du fait colonial: enjeux et transformations.” Revue d’Histoire des Sciences Humaines 24, no. 1 (2011): 189.

- Prost, Henri. “Le développement de l’urbanisme dans le protectorat du Maroc, de 1914 à 1923.” In L’urbanisme aux colonies et dans les pays tropicaux. Vol. 1. La Charité-sur-Loire: Delayance, 1932.

- Radoine, Hassan. “Tradition and Myth in the Madina: Conservation and Change.” Ecology and Anthropology of Traditional Dwellings 246 (2012): 1–32.

- Rivet, D. Le double visage du protectorat: le Maroc de Lyautey à Mohammed V. Casablanca: Editions porte d’Anfa, 2004.

- Rivet, D. Le Maghreb à l’épreuve de la colonisation. Paris: Fayard/pluriel, 2010.

- Royer, Jean. “L’urbanisme aux colonies et dans les pays tropicaux.” Vol. 2 in Communications et rapports du congrès international de l’urbanisme aux colonies et dans les pays de latitude intertropicale. La charité sur Loire: Delayance Editeur, 1932.

- Somé, Maxime. Présence et images franco-marocaines au temps du protectorat. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2003.

- Théliol, Mylène. “Aménagement et Préservation de La Médina de Rabat Entre 1912 et 1956.” Les Cahiers d’EMAM, no. 22 (2014): 47–70. doi:10.4000/emam.548.

- UNESCO. Rabat, capitale moderne et ville historique: un patrimoine en partage. https://whc.unesco.org/fr/list/1401/.

- Vaillat, Léandre. Le périple marocain. Paris: Flammarion, 1934.

- Vaillat, Léandre. “L’esthétique aux colonies.” In L’urbanisme aux colonies et dans les pays tropicaux. Vol. 2. La Charité-sur-Loire: Delayance, 1935.

- Wilbaux, Quentin. La médina de Marrakech. Formation des espaces urbains d'une ancienne capitale du Maroc. Paris: L'Harmattan, 2001.

- Wright, Gwendolyn. “Tradition in the Service of Modernity: Architecture and Urbanism in French Colonial Policy, 1900–1930.” The Journal of Modern History 59, no. 2 (1987): 291–316.

- Wright, Gwendolyn. The Politics of Design in French Colonial Urbanism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991.