ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the writing of Black activists, planners, and critics to reconcile two opposing perceptions of the Model Cities Program: an initiative known for its elevation of Black elected officials and a program that used the guise of citizen participation to stifle more radical forms of dissent. In 1966, Model Cities emerged in part from the call for a domestic Marshall Plan for Black Americans. Yet as the program began making incremental changes to the country’s neighbourhoods from 1967 to the early 1970s, participants and critics instead began to see Model Cities’ relationship to Black Americans as a new form of colonialism. To determine how this shift occurred, this paper analyses this critical commentary against the archival evidence of Model Cities implementation in the cities in which it appeared. Situating these authors’ arguments within the parallel emergence of Black studies and participatory planning as well as within larger Cold War diplomatic history, planning history, and African American intellectual history reveals how visions of revolution turned into a program of representation. Meanwhile, the plans these figures produced as part of Model Cities point to what a revolutionary program might yet be.

Introduction

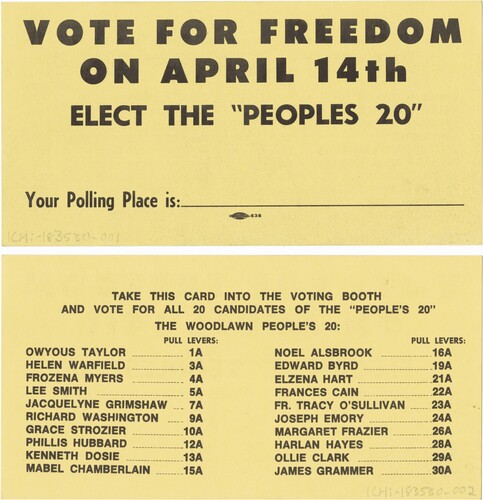

When the Lyndon B. Johnson administration convened the 1965 Task Force on Metropolitan and Urban Problems to design a program targeting poverty and racial conflict in America’s cities, it asked UAW President Walter Reuther to suggest potential members. Reuther’s focus was poverty, so to tackle the problem of race, he suggested National Urban League Executive Director Whitney M. Young Jr.Footnote1 In 1964, Young had published To Be Equal, a national call for a domestic Marshall Plan for Black Americans ().Footnote2 To a greater extent than the other plans brought to the task force table, Young’s domestic Marshall Plan detailed the targeted investments in education, employment, healthcare, welfare, and civic leadership that ultimately distinguished the Model Cities legislation from all federal urban renewal programs that preceded it.Footnote3 These unique similarities call for a reappraisal of the erasure of Young in Model Cities historiography in order to better understand the visions of racial justice that Black activists, critics, and planners brought to the program. Meanwhile, the key distinctions between Young’s domestic Marshall Plan and Model Cities point to how the Johnson administration's anti-poverty framework both prevented Model Cities from becoming a true program of racial redress and nonetheless still provided Black activists, critics, and planners with a path to demand, and to an extent achieve, limited gains in neighborhoods across the United States.Footnote4

Figure 1. The original book jacket of To Be Equal, cover design © Lawrence Ratzkin. Source: Whitney M. Young Jr., To Be Equal, McGraw-Hill, 1964.

Positive evaluations of Model Cities have argued that the program trained a generation of local leaders of colour, while others have discredited Model Cities and other citizen participation-based programs for stifling dissent.Footnote5 Following Young’s vision through to the implementation of Model Cities reveals Black activists and planners who did question the program’s merits but nonetheless commandeered its mandate for citizen participation to claim civic power. From Young’s conceptual foundation, this article follows the political trajectories of two Model Cities critics whose articles in the Journal of the American Institute of Planners (JAIP) and The Black Scholar (TBS) illuminated both the dangers and potentials participants saw in the program. In March 1969, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee member and planning student Kwame Leo Lillard published ‘Model Trains, Model Airplanes, Model Cities,’ in JAIP while chairing the Model Cities Housing and Urban Planning Committee of East New York, after which he became a revered city councilman in Nashville, Tennessee. In April 1970, Black Power-aligned student activist Ralph Metcalfe Jr. published ‘Chicago Model Cities and Neocolonization,’ in TBS based on his familiarity with Chicago’s South Side and Democratic machine, the latter of which he later helped topple. A close reading of these articles against the local implementation of their Model Cities plans reveals how Lillard and Metcalfe Jr. simultaneously drew on varied forms of internationalist discourse, local programs, and activist backgrounds to demand accountability not only from Model Cities but from planning’s larger turn towards participation.Footnote6 Bringing Black planning criticism to the fore reveals just how activists, critics, and planners achieved their limited civic gains, while the plans they produced outline a path towards a true program of racial redress based in the built environment.

Model Cities and a domestic Marshall Plan

In 1975, Johnson aide Charles Haar highlighted Reuther while obscuring Young in the first major summary of Model Cities, Between the Idea and the Reality, and no histories of Model Cities have since revisited his assessment.Footnote7 Haar places the start of Model Cities in May 1965, when Reuther and his collaborator, the architect Oskar Stonorov, sent a memo to the president advocating for a ‘crash program’ to rebuild a series of cities as ‘demonstrations’ of the Great Society’s potential for aiding the ‘poor and racially discriminated.’Footnote8 However, the internal legislative background history produced by other Johnson aides reveals a far more crowded field of actors whose presence explains the differences between Reuther ‘s memo and the Model Cities Program’s final legislative form.Footnote9 The two topics of the first task force meeting that October were ‘Reuther’s Plan’ and an already unattributed ‘Marshall Plan for Cities.’Footnote10 The task force report that merged these plans dictated the direction of the program tasked with coordinating the vast funds of the War on Poverty in America’s neediest neighbourhoods. Young’s Marshall Plan provides insight into the calls for full Black citizenship that informed this program and how frames of poverty and the built environment limited its field of vision from the start.

Whitney M. Young Jr.’s domestic Marshall Plan

Young maintained that a domestic Marshall Plan would correct centuries of oppression by providing a ‘special effort’ across every aspect of Black American life: housing, education, employment, healthcare, welfare, and leadership development.Footnote11 By tackling discrimination from every such angle, the plan would provide both the opportunity for equality and the training in ‘the responsibilities of citizenship’ that Young felt the assimilation of past immigrant groups had lacked.Footnote12 He did not frame the plan as planning criticism at the time, but provided as evidence his observation of the poor conditions for Black residents of ‘nearly every city of twenty-five thousand or more in the country.’Footnote13 Young reasoned that an unequally weighted scale would not even out with the application of equal weight; only the addition of unequal resources would bring balance. However, he strategically framed this reparative gesture against white America’s perception of the Marshall Plan as a period of generosity it could elect to continue. The Marshall Plan had also been temporary, and Young further emphasized speed with terms like ‘crash program’ and ‘demonstration’: ten years of aid to repay three hundred years of struggle.Footnote14 Perhaps given that Young based his call more in altruism than in indictment, scholars are divided on his inclusion in the history of reparations.Footnote15 At the time however, this framing received wide acclaim from white liberal readers, The New York Times calling it ‘required reading for every corporation executive and government official.’Footnote16 Proponents of Black Power criticized this relationship, but with it and the support of many working class and integrationist Black Americans, Young helped insert the issue of racial discrimination in some of the country’s largest domestic programs to date.Footnote17

Still, divergent definitions of disenfranchisement among civil rights leaders and white liberals often relegated race to the fine print of programs for the disenfranchised. The differences between Reuther’s memo and Young’s plan make this clear. Reuther called for redeveloping urban areas but provided little social context to the conditions he sought to fix. With respect to Young’s demand for righting the country’s exploitation of Black Americans and other minority groups, Reuther made one broad overture to the ‘poor and racially discriminated,’ but largely eschewed racial language.Footnote18 Instead, Reuther preferred terms like ‘urban’ and cities’ and focused on transforming ‘ghettos’ of ‘hand-me-downs’ rather than the systems that created them.Footnote19 In a nod to Young’s ‘special effort,’ the task force’s January 1966 report ultimately brought ‘the special problem’ of racial discrimination back into focus while introducing the full range of Young’s social programs to Reuther’s demonstration areas.Footnote20

However, the Model Cities Program’s place as the hallmark of the new Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) placed both race and poverty in an agency whose ‘urban’ priorities were still in formation. Young and task force member Bureau of the Budget Director Kermit Gordon registered this concern in the only dissent to the task force report, arguing that the Department of Health, Education and Welfare’s social strengths made it a more appropriate home than HUD.Footnote21 Hiding racial equality in urban programs carried over into the erasure of Black contributors more broadly. Young and inaugural HUD Secretary Robert Weaver both later admitted feeling slighted in attributions of support for the program.Footnote22 The legislative need for Southern support also chipped away at the program’s power over desegregation.Footnote23 The decision to define ‘the urban problem’ around concepts like poverty and the built environment obscured calls for racial equality while limiting the kinds of solutions that programs could provide.

Walter Reuther, the Johnson Administration, and a Marshall Plan for cities

Even for those who preferred to focus on poverty and cities over race, the Marshall Plan was still a popular example of large-scale aid. Prior to his more well-known memo, Reuther sent another to Johnson advocating for ‘democratic national economic planning’ as modelled by the Marshall Plan in Western Europe.Footnote24 The labour leader spoke from experience, as he had served as a representative of the United States tasked with convincing European unions to accept American aid. Reuther’s presence had shown European social democracies wary of American capitalism that labour endorsed the plan’s promised union between labour and management.Footnote25 Reuther also continued visiting recipient countries as the plan commenced and tested out Marshall Plan-like development in his own Detroit.Footnote26 In 1954, Reuther retained Stonorov, Victor Gruen and Associates, and Leinweber, Yamasaki, & Hellmuth to master plan a public housing demonstration, Gratiot-Orleans, as an example of citizen-designed, integrated, mixed-income housing.Footnote27 By the time Model Cities began working in the surrounding neighbourhoods fifteen years later however, the project, renamed Lafayette Park and executed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilberseimer, and Alfred Caldwell, was an island of relative whiteness and affluence in an increasingly poor and Black city, an example the local Model Cities councils sought to avoid.Footnote28 Reuther’s work, though also influenced by the Marshall Plan, yielded an outcome much different than either Young or Model Cities envisioned.

Even if Reuther deemphasized racial discrimination over poverty and the built environment, the Johnson administration framed its new ‘Marshall Plan for Cities’ as the solution to the racial uprisings spreading across the nation when it presented Model Cities to Congress in 1966 and to the American public after its passage that November. In 1967, Vice President Hubert Humphrey advocated for a ‘Marshall Plan for Cities’ at the Democratic Mayors Conference in New York and again at the National Association of Counties in Detroit just one week after the country’s largest uprising up to that point roiled the city.Footnote29 News media broadcast this call to a wider public; The New York Times held two special interviews with Humphrey and Weaver that August while Parents Magazine ran Young’s reflection on how his once improbable domestic Marshall Plan was now wildly popular.Footnote30 Then in 1968, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders gave another crucial endorsement, naming structural inequality as the root of unrest and Model Cities as the ‘minimum start’ for addressing it.Footnote31 That same year, Young gave a keynote at the American Institute of Architects National Convention that is now considered a turning point in the profession.Footnote32 Even if Young had not intended the domestic Marshall Plan as planning criticism, the uprisings’ unique spatiality and the framing of race as an urban issue made Young a key commentator on the urban future.Footnote33

Comparison to the Marshall Plan made political sense, as post-war American public opinion of the program remained high and Model Cities appropriations were small in comparison by programmatic design.Footnote34 The Johnson administration intended Model Cities to serve as ‘glue money’ concentrating much of the larger War on Poverty funds in specially-designated neighbourhoods.Footnote35 The roughly $200 million provided for first-year planning grants and the roughly half billion provided yearly for the program’s five-year remainder did not come close to Marshall Plan funding when spread across over 150 locations, but access to far greater funds made large scale change possible in the right contexts.Footnote36 The program thus promised to direct Marshall Plan-scale change largely through already appropriated funds. Yet, as Model Cities’ critics later made clear, aid programs revealed power imbalances between grantor and grantee. Many European governments bristled at American impositions, with even conciliatory governments like the Netherlands maintaining its social welfare state while existing powers, like Britain, found themselves transformed into clients or tourist destinations for the United States.Footnote37 Latin American governments also felt slighted by the plan’s European focus given their wartime contributions.Footnote38 Within the United States, the Marshall Plan also worried critics of European colonialism. Black newspapers argued for making aid contingent on decolonization while National Association for the Advancement of Colored People President Walter White argued for sending Marshall Plan aid directly to former colonies.Footnote39 These criticisms anticipated concerns about colonial control when aid turned inward.

In arguments over the Marshall Plan there existed unanswered questions concerning the meaning of aid. Dissonance between calls for racial justice and white liberals’ frames of understanding reflected larger debates on the scope of structural inequities, the scale of aid required to fix them, whom should control this aid, and to what extent. Those who sought to shape the planning profession in response placed Model Cities at the centre of their discourse.

Planning criticism and a model-sized Marshall Plan

While Young’s role in the National Urban League influenced planning on a conceptual level, other civil rights activists entered the profession itself. In 1960, Kwame Leo Lillard was participating in some of the earliest lunch-counter sit-ins as a young member of the Nashville Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.Footnote40 In 1969, he was pursuing a Master of City Planning at Hunter College, planning a vast overhaul to East New York’s housing stock for Model Cities, and calling for greater support in JAIP, a multi-pronged practice he later applied to elected office in Nashville. Lillard was not alone; mid-century cultural revolution had crashed through professional planning, producing new calls for participation and attention to social issues. After experiencing the ‘explosion of planning’ of 1946–1960, the profession attempted to adapt to its newfound relevance.Footnote41 In 1959 the American Institute of Planners (AIP) outlined anti-oppression as an aim, in 1967 it organized a Committee on Minority Relations, and in 1974 it developed an advocacy planning program.Footnote42 New groups, most notably Planners for Equal Opportunity (PEO), split off from AIP to centre social problems and advocate for participatory planning with marginalized groups. The War on Poverty’s maximum feasible participation mandate created manifold opportunities to test these processes and report on their results.

Planning’s progressive voices used JAIP to express concern about planning’s scope and its understanding of participation. Denise Scott Brown wrote in the JAIP issue that followed Lillard’s that architects who confronted social issues ‘often abandon both architecture and urban design, frustrated by their irrelevance.’Footnote43 In the same issue, Ford Foundation staffer John Friedmann called for a redirection in planning education to accommodate the economic, social, and political work that planners often undertook without training.Footnote44 In the issue after that, Sherry Arnstein published ‘The Ladder of Citizen Participation,’ now a foundation of participatory planning discourse, which used Model Cities projects across the country to illustrate nearly all of her nine rungs of participation.Footnote45 The meetings she described revealed that few authorities offered true participation outright, but many local residents demanded it. Critics who could connect such local struggles to global concerns, as Lillard would, shaped Model Cities’ legacy long afterwards.

‘Models are for little boys … we’re men’

It was in this arena that Lillard published his JAIP article ‘Model Cities, Model Airplanes, Model Trains,’ in March 1969. As chairman of the East New York Housing and Urban Planning Committee, Lillard had helped develop East New York’s contribution to the housing plan for Central Brooklyn’s Model Cities Program. In ‘Model Cities, Model Airplanes, Model Trains,’ Lillard criticized the lack of bureaucratic and financial support for the recipients of Model Cities funding, likening the development program to hobby toys for white children. Lillard argued that ‘Models are for little boys,’ serving well for ‘pre-exposure and child development,’ but failing ‘when the people are real.’Footnote46 He pointed to the elements of the program’s local implementation that seemed unserious: no dedicated staff nor space, indifference from city agencies, and just two years into implementation, an already unclear future. Like Young, he looked to Europe, suggesting that the contrast between domestic spending and foreign aid demonstrated that white America feared Black power’s threat to white dominance more than the country it had just fought in war:

After World War II, it took very little time for the U.S. to restore Germany so that it could resume its role as an industrial ally. The U.S. did not decide that what Germany needed was ‘Demonstration Factories,’ or ‘Model Highways’ or ‘Experimental Economic Exhibitions’ … When it comes to ghettos, the hobby shop mentality prevails, and all the ‘Band-Aid,’ ‘Cool ‘em Off,’ ‘Throw a Crumb’ programs, personalities, and politics again descend upon the dissatisfied … Footnote47

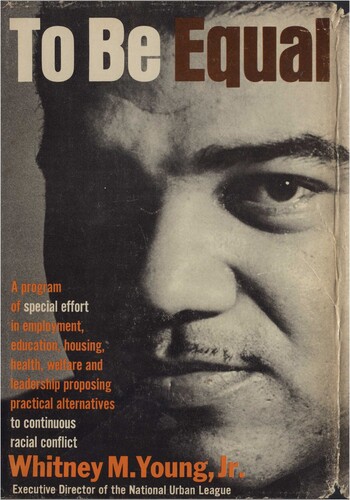

Amid Lillard’s indignance at the limits placed on the East New York Housing and Urban Planning Committee’s ambitions, his writing in JAIP demonstrated great pride in a plan he called ‘clear proof of what a ghetto can do.’Footnote49 He proclaimed the promise of 789 public housing units, 406 middle-income units, 950 rehabilitated units, a two-acre park, a 40,000 square-foot health centre, a pool, a library, playground additions, and the neighbourhood-wide transfer of inadequately maintained housing to community control. This plan, developed with the assistance of PEO co-founder Walter Thabit, was one of three submitted to the Central Brooklyn Model Cities Program, along with equivalent plans for Brownsville and Bedford-Stuyvesant (). The news reported that though New York’s three target areas of Central Brooklyn, the South Bronx, and Harlem-East Harlem had received a shared $65 million dollars from Model Cities alone to get such projects started in the first year, it had already bungled distribution.Footnote50 With planning underway but funding uncertain, Lillard called out the foolishness of attempting society-scale change on a toy-scale budget. However, rather than indict Model Cities in its entirety, he argued for expanding power and funds to Black neighbourhoods.Footnote51

Figure 2. Map of the Central Brooklyn Model Cities neighbourhood target area, with East New York at far right. Source: City of New York Demonstration Cities Program Draft Summary of Proposal, 1967, New York Public Library.

Outside of housing, Central Brooklyn hosted programs that likewise felt the effects of unstable funding. A Model Cities-Brooklyn Public Library bookmobile brought books straight to the neighbourhood but could not pay staffers for several weeks.Footnote52 A Brooklyn Museum-sponsored education program shut down less than three months in when Model Cities funds did not materialize.Footnote53 Amid a garbage crisis in 1970, Central Brooklyn Model Cities administrator Horace Morancie requested $2.4 million for sanitation programs.Footnote54 Two years later, the office staff had resorted to picking up litter themselves.Footnote55 Less vulnerable programs managed small-scale improvements. The Brooklyn College Television Center operated a program that trained forty five residents in television and radio broadcasting.Footnote56 A Community Fire Safety Education program paid thirty resident trainees to educate neighbours on fire prevention techniques during the day while receiving tutoring for high school diplomas and the city’s civil service examination at night.Footnote57 Model Cities sent fourth, fifth, and sixth graders to summer day camp in New Rochelle.Footnote58 A Community Defender Office offered free legal support to residents.Footnote59 Unlike in post-Marshall Plan West Germany, such successes were often intangible or when visible, quite limited in scale. From the view of a housing and planning critic, Model Cities looked like a Marshall Plan in miniature.

Between frustration and opportunity

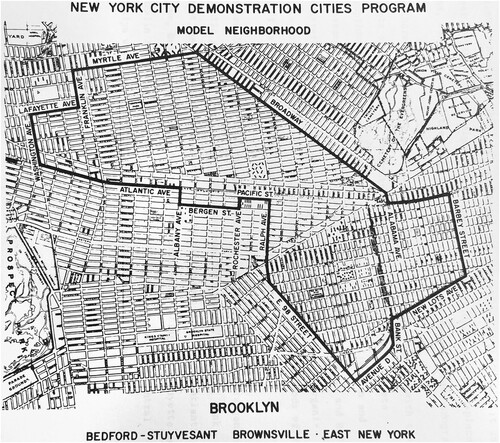

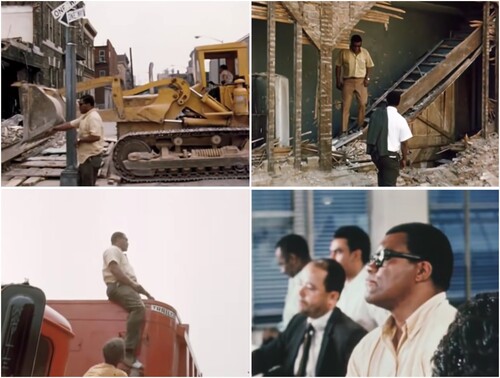

At the same time, local officials did attempt to capture small successes on film. In Between the Word and the Deed, a film commissioned by Model Cities but not shown at the time, participation gets heated as dozens of residents, Lillard included, shout at each other and at government officials ().Footnote60 However, another documentary entitled What Is The City But The People? followed a single man, Joe White, who rose from a kitchen helper to the owner of a demolition company. ‘Model Cities gave him the chance. His own drive kept him pushing,’ claims the narrator as White walks through a Model Cities demolition site, sits atop some machinery, and attends a Model Cities evening business course ().Footnote61 The selection of Model Cities anecdotes could reveal either frustration or opportunity among the program’s participants.

Figure 3. Film stills from Between The Word and The Deed depicting confrontational community meetings in the Central Brooklyn Model Cities Program; Leo Lillard pictured in bottom left. Source: Gordon Hyatt, New York City Model Cities Program, 1970.

Figure 4. Film stills from What Is The City But The People? depicting demolition company owner Joe White at work in the Central Brooklyn Model Cities target area and in night classes paid for by the program. Source: John Peer Nugent and Gordon Hyatt, New York City Department of Planning, 1969.

These small successes bore a remnant of the special effort Whitney M. Young Jr. had envisioned. Lillard similarly concluded that the main challenge of Model Cities was to ‘maximize the benefits out of the small amount of resources,’ and noted his appreciation for how even the testiest committee deliberations made ‘better people’ out of the multi-ethnic coalition in the room.Footnote62 Thabit also later suggested that small cities with more manageable projects found more success.Footnote63 Paralleling this prediction, Lillard returned to Nashville shortly after his work in Model Cities, where he joined the Metro Council, advocated for preserving historic Black neighbourhoods and against the building of a new police headquarters in North Nashville, founded the city’s African American Cultural Alliance, and organized yearly celebrations of Juneteenth, Kwanzaa, and the city’s African Street Festival.Footnote64 The experience of working with meagre funds in the nation’s largest metropolis undoubtedly provided significant training for his accomplishments in Nashville. Stories like that of White and Lillard demonstrated the impact of Model Cities, albeit on an individual, rather than society-wide scale.

Even still, the pressures of mandatory participation crossed by the crunch of insufficient funding yielded widespread distrust among residents even as it provided opportunities to some of their neighbours. Thabit argued that the Model Cities Program’s key detriment was the widespread distrust of authorities, including those like himself; Morancie meanwhile felt his constituents perceived him as not an ‘Uncle Tom,’ but a ‘Super Tom.’Footnote65 As critical as these authorities were of Model Cities themselves, others perceived their professional affiliations as too compromising. As Ralph Metcalfe Jr.’s criticism of Model Cities in Chicago would show, even more hostile relationships between local government, Model Cities staff, and residents prompted other critics to question Model Cities’ very intent.

Black studies, Model Cities, and neo-colonialism

While Lillard came to planning criticism from the civil rights protests of the early 1960s, Ralph Metcalfe Jr. came to understand Model Cities through the revolutionary politics of the decade’s end. He became attracted to Black Power when he attended the 1968 conference convened by Nathan Hare, a co-founder of the journal The Black Scholar (TBS) in which Metcalfe Jr. would publish a blistering critique of Model Cities two years later.Footnote66 Ralph Metcalfe Sr., a machine-appointed congressman, gave his son insight into one of the most city-controlled iterations of Model Cities and, amid Model Cities’ local contradictions, together they later broke from the machine. The field of Black studies had also emerged in this period as a curricular movement to parallel calls for more Black student and faculty representation and in 1969, Hare and Robert Chrisman founded TBS to provide the field a platform for addressing issues both within and outside of the academy.Footnote67 To do so, the journal’s authors brought together the first generation of Black studies faculty from universities across the United States, a range of civic leaders, and some of the Black freedom movement’s most audible activists.Footnote68 This professional breadth brought varied perspectives onto topics critical to Black freedom at the time.

Just as scholars have argued that TBS offered a venue for emergent subfields like Black sociology and Black media studies, the first issues of TBS demonstrate that it also provided planning critics the chance to reach a new audience specifically attentive to the interplay between planning and Black freedom.Footnote69 Sociologist Joyce Ladner and policymaker Walter Stafford jointly published in both JAIP and TBS in the span of 1969–1970 and each journal’s respective audience informed their discussion of racism, planning, and Model Cities. Their JAIP article, ‘Comprehensive Planning and Racism,’ offered a careful explainer of how racism interacted with the planning profession specifically for ‘planners who accept this premise.’Footnote70 Meanwhile, their TBS article, ‘Black Repression in the Cities,' assumed their readers already trusted that racism was ‘structurally imbedded’ within organizations like centralized planning.Footnote71 Likewise, while Ladner and Stafford pointed to specific flaws in Model Cities implementation in JAIP, they did not shy from totalizing claims in TBS. In JAIP, the two found specific fault in Chicago’s ‘conclusively racist’ reliance on city council-determined racial balances for housing site selection and its patronage system, both of which hindered actual neighbourhood control.Footnote72 In TBS however, Ladner and Stafford expanded their criticisms out from Chicago, writing that Model Cities was so divorced from neighbourhood control that the programs had ‘no significant local identity.’Footnote73 While JAIP offered a platform for teaching planners to identify racism in city-specific problems, TBS prompted the question of whether Model Cities and planning represented larger systems of control.

This question reflected the theme of TBS volume 1, number 6, to which Metcalfe, Ladner, and Stafford contributed: ‘Black Cities: Colonies or City States?’ TBS was well-positioned to have this discussion, as it had already published the writings of several city officials and international political leaders.Footnote74 Many authors in the issue contextualized the plight of Black people in the United States within global anticolonial struggle by drawing parallels between American domestic policy and military engagement, such as Eugene B. Redmond, in the poem, ‘barbequed cong: OR we laid MY LAI low’:

i lay down my life for My Lai and Harlem.

i lay down my burden in Timbuctu and Baltimore.Footnote75

‘A program for the neocolonization of nonwhite human capital’

Ralph Metcalfe Jr.’s place in the urgent protests of the late 1960s set his written criticism of Model Cities apart from Young’s and Lillard’s. While Young wrote the domestic Marshall Plan as the National Urban League’s leader and Lillard published in JAIP after his Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee involvement, Ralph Metcalfe Jr. published in TBS while active in Columbia University’s Society of Afro-American Students (SAS) and a new proponent of Black Power. Metcalfe Jr. had led large protests of the school’s proposed Morningside Park gymnasium, Vietnam War ties, and lack of Black studies courses.Footnote79 Threads of these campus concerns carried through into Metcalfe Jr.’s searing evaluation of Model Cities.

In ‘Chicago Model Cities and Neocolonization,’ Metcalfe Jr. argued that without tackling segregation first, Model Cities would solidify new American neo-colonies: inner city areas where concentrated Black labour would keep cities operational while white wealth saturated the suburbs. He warned:

Deprived even of land, black people are to form the backbone of all urban labour, thus enabling the devil oppressor to move to suburbia where, free from the hustle and bustle of the city, he can enjoy peace of mind while oppressing and exploiting the majority of the people living on the face of the earth.Footnote80

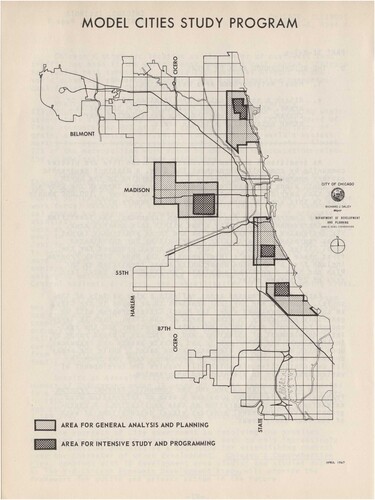

Following Nkrumah’s argument that neo-colonialism operated through civil servants, Metcalfe Jr. referred to the Black machine-backed politicians who supported Chicago’s Model Cities projects as a traitorous, white-controlled petty bourgeois class.Footnote81 This included Metcalfe Jr.’s father, alderman-turned-congressman Ralph Metcalfe Sr., and while accusing officials like his father of treason may not have recognized the complexity of attempting change through bureaucracy, Chicago Model Cities offered a unique case of white control.Footnote82 In the absence of strict HUD rules, Mayor Richard J. Daley had packed each forty-person neighbourhood council with twenty of his own appointees.’Footnote83 In the Uptown, Lawndale, and Near South model neighbourhoods, additional Democratic Party-picked slates swept even the elected seats ().Footnote84 This misrepresentation drastically redetermined planning priorities. Model Cities staff and residents disagreed over housing needs, with officials downgrading it even though residents designated it most important.Footnote85 Despite resident wishes for new parks and recreational centers, the Department of Human Resources instead opted for community-scale experiments, establishing Leisure Time Councils to design group activities for ‘building community strength.’Footnote86 Metcalfe Jr. had rightly called out the white establishment’s power grab.

Figure 5. Maps of Chicago Model Cities Study Program Areas, showing from top to bottom, Uptown, Lawndale, Grand Boulevard (Near South), and Woodlawn. Source: The Chicago Approach to Model Cities, 1967, New York Public Library.

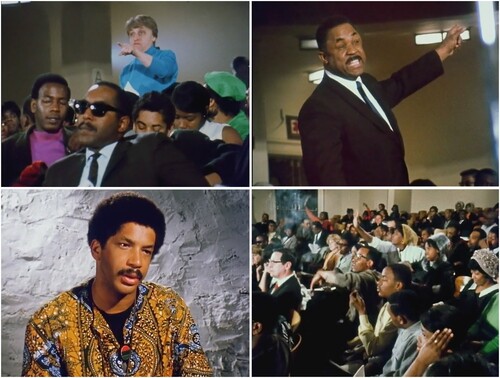

At the same time, not all those who confronted Daley’s actions eschewed Model Cities entirely. The Woodlawn Organization (TWO) campaigned widely throughout its model neighbourhood to designate a full twenty-person slate, whom they dubbed ‘The Woodlawn People’s Twenty.’ TWO distributed literature to explain election procedure and lay out its stakes.Footnote87 Their flyers, printed loudly with the words ‘VOTE FOR FREEDOM ON APRIL 14th,’ represented the potential they saw in retaining even just half of their council ().Footnote88 While becoming the only neighbourhood to control all of their elected seats, TWO also devised their own Model Cities plan in collaboration with the University of Chicago Centre for Urban Studies. Their 145-page plan included a guaranteed income, a neighbourhood health insurance plan, a system of flexible outreach offices to administer social services, and a career vocational institute.Footnote89 Nixon’s HUD administration ultimately selected the more piecemeal plan that Daley’s neighbourhoods devised, but TWO’s organizing provided its neighbourhood with greater voice over how Model Cities implemented these programs in Woodlawn and a record of what the neighbourhood prioritized from the beginning.

Opportunity for whom?

As TWO’s efforts demonstrated, a fine line separated a reparative approach to physical and social redevelopment from repression. Metcalfe Jr. likewise worried that Model Cities sought to direct the lives of residents, in his words, ‘not in their own best interests, but toward the aim of socializing them to accept their role in the neocolonial situation.’Footnote90 This criticism questioned whether examples like Central Brooklyn’s Joe White supported Black opportunity or pacified dissent. However, Metcalfe Jr.’s radical critique was in many ways just that, as other commentators lauded the network of opportunities that Model Cities sowed across the city.

Chicago’s merger of Model Cities with its Community Action-era Chicago Committee on Urban Opportunity, known together as MC-CCUO, encouraged education, childcare, and healthcare programs to double Model Cities neighbourhood needs with Community Action-style job training. In education, MC-CCUO built up parallel networks of childcare centres and schools that also offered adult education and employment. A parent–child centre offered a location where parents could learn skills or take classes while Model Cities staff provided childcare.Footnote91 Cooperatively Planned Urban Schools, or ‘CO-PLUS’ schools, offered education to 6,500 pupils in flexible classrooms, while school-homes, or ‘schomes,’ provided around 800 children with pre-school education in prefabricated units that resembled home environments.Footnote92 Both relied on 1,500 residents who worked as school aides during the day and attended classes in the same rooms at night. For healthcare, a set of four Model Cities outpatient health clinics located across the target areas offered both low-cost care and workshops that the Chicago Defender lauded for helping residents take advantage of the growth in healthcare fields at the time.Footnote93 Broadly categorizing Model Cities as neocolonization anticipated the continuation of inequality if reform ended at the neighbourhood boundary. Yet, the neo-colonial critique overlooked the chance that neighbourhood programs might provide residents with the skills to personally transgress such boundaries later on.

Just as the selection of subjects in New York’s Model Cities documentaries produced alternate evaluations of the program, varied opinions among Chicago’s news outlets demonstrated that the media itself also mattered in making these distinctions. While Metcalfe Jr. had cautioned that machine politicians would use the new jobs ‘to entice citizens to work for that machine,’ the Chicago Defender chose to focus on the people themselves, such as the unemployed veterans that a truck driving certification program put back to work.Footnote94 Coverage showed the same residents first as trainees and then as trainers, such as Weader Lynch, shown graduating from the Model Cities Health Aides Program in the Chicago Tribune in 1970 and teaching a health workshop one year later in the Defender.Footnote95 In 1972 however, the Tribune published a more mixed nine-part evaluation. It deemed CO-PLUS schools and schomes successes but termed the businesses who received Model Cities contracts as a ‘“Who’s Who” of the local Democratic establishment.’Footnote96 The Tribune found that these contractors did not prioritize model neighbourhoods either. One housing contractor had refused to work next to rundown buildings and proceeded to construct homes outside the target areas instead. Claiming it could not conduct economic development without new housing, the Chicago Economic Development Corporation had followed suit, but not before already providing four times the aid for businesses outside the target areas as for those inside of it.Footnote97 While Metcalfe Jr. feared that Model Cities’ neighbourhood focus would continue inequality, the work of some local Model Cities contractors threatened to exacerbate it.

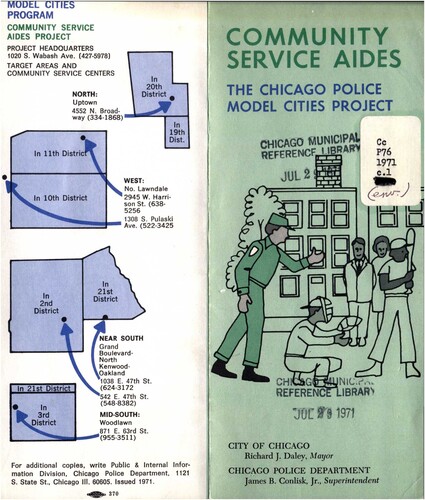

While these programs spread aid outside the target areas, MC-CCUO’s Community Service Aides Program embodied the danger of investing in opportunity without reforming racially discriminatory organizations. Under this program, Model Cities employed 1,600 model neighbourhood residents to work as what it called the ‘listening ear’ of the Chicago Police Department ().Footnote98 These agents did not carry weapons, could not make arrests, did not need to meet the department’s age or physical qualifications, and operated out of MC-CCUO’s community service centres instead of police precincts. The project intended for agents to aid in the everyday trials of city life, such as investigating garbage pick-up delays or finding lost pets, issues the police often ignored while criminalizing Black and Brown Chicagoans’ everyday activities. However, such criminalization did not stop. Rather, as Johnson’s War on Poverty evolved into a War on Crime, law enforcement infiltrated all aspects of life. Even an MC-CCUO acting class entitled ‘Acting Is the Art’ had young Black children act out scenes where they misused money, committed burglary, and stole money from a purse while others called the police.Footnote99 The community service aides were also never fully separate from existing police operations; Model Cities staff championed how the program would ‘free the policemen to take care of following up crimes.’Footnote100 Metcalfe Jr. made the same point more bluntly in TBS, warning that this allowed the police to further antagonize demonstrators and dissidents.Footnote101

Figure 7. Front and back cover of a brochure explaining the role of the Community Service Aides. Source: Municipal Reference Collection, 1971, Chicago Public Library.

Beyond even Metcalfe Jr.’s warnings, policing undermined MC-CCUO’s attempt to bolster a Black professional class when police officers brutalized not demonstrators, but rather two Black dentists, Drs. Herbert Odom and Daniel Claiborne, during traffic stops on Chicago’s South Side in spring 1972. Within a month, Ralph Metcalfe Sr., Odom’s friend, held hearings that marked a final split between Metcalfe Sr. and the Daley machine.Footnote102 The exhaustive report that they produced, ‘The Misuse of Police Authority in Chicago,’ listed out the titles of Black and Brown Chicagoans who had experienced police violence – a postal employee, a teacher, father of four, mother of five – titles that described model citizens. The report also revealed that the only people in Chicago not expected to be model citizens were the police themselves. Two police psychologists testified that the police department sent officers found to have ‘emotional and personal defects’ to ‘high crime areas’ in order to ‘make or break them.’Footnote103 Metcalfe Sr.'s report revealed that the very police force that had received more than ten percent of Model Cities’ budget up to that point had widely abused the program’s intended beneficiaries, undermining the potential of educational models, jobs, or health improvements made even in Chicago’s particularly constrained version of Model Cities.

Metcalfe Sr.’s split from Daley brought him and his son back together while encouraging him to take on an opposition mindset both in Chicago and as part of the Congressional Black Caucus. Together, the Metcalfes protested President Richard M. Nixon’s decision to let Model Cities end; new political independence meant little if there was no aid with which to enact change.Footnote104 Meanwhile, Metcalfe Jr. returned to Chicago to pursue a master’s degree in political science at Northwestern University and to campaign for his father and other local opposition candidates.Footnote105 One of these, Harold Washington, took over the mayor’s chair [historical correction] in 1983 after briefly filling Metcalfe Sr.’s congressional seat.Footnote106 Though Metcalfe Jr. did not attain the same political success as his father, he later became an archivist of Chicago blues and of his father’s legacy.Footnote107 Other critics also turned into supporters as Model Cities’ end neared. Despite his protests against the Model Cities-funded police department, Odom also organized a group of fifty medical professionals to oppose the end of Model Cities health funding.Footnote108 The Chicago Defender noted that while Model Cities had not improved the lives of many impoverished Chicagoans, its closure threatened the livelihoods of a newly-made middle class, including all 1,600 community service aides that the police department fired once Model Cities funding ended.Footnote109 In stark contrast to the Tribune’s earlier criticisms, the Defender argued for saving Model Cities as ‘among the most efficiently and judiciously administered agencies’ in Chicago.Footnote110 Throughout the operation of Model Cities in Chicago, commentators hotly debated the merit of its programs, actors, and intent, but no matter their earlier concerns, agreed that its absence would be much worse.

The legacies of Model Cities criticism

Recent evaluations of the Model Cities Program point to its elevation of people of colour into positions of local power through its citizen participation mandate, not unlike a scaled-down version of Young’s goal for a domestic Marshall Plan.Footnote111 As the Metcalfes and Harold Washington show, his trend did not stop at Model Cities staffers either. Likewise, if Model Cities provided political opportunities for those who balanced criticism with cooperation, less conciliatory actors like Metcalfe Jr. or TWO demonstrated the importance of external voices for keeping government officials accountable and for highlighting possibilities others could not yet see. These examples of Black planning criticism reveal that the elevation of Black political power through Model Cities happened hardly by programmatic design but rather through highly dynamic processes of political struggle that relied on local people claiming power promised to them in theory but not necessarily given in practice. Scholars must not mistake these contentious forms of participation as an indictment of aid programs but rather as the debates which separate participation from pacification, reparation from repression. Young, Lillard, and Metcalfe Jr. called for greater aid and greater control, but used limited resources to produce plans for revolutionary change. The plans that they and other Model Cities participants produced demonstrated the revolution that this new leadership may have accomplished if only aid had expanded along with them.

These critics also called for a more honest reconciliation of racial discrimination than government officials wanted to undertake at the time. Indeed, Model Cities paralleled a much wider racial awakening than a single article solely devoted to three works of Black planning criticism can reveal. Widening the geographic frame even slightly beyond New York’s Brooklyn and Chicago’s South Side reveals the Puerto Rican residents of the Bronx and East Harlem, New York and the Japanese American and Indigenous groups resettled in Uptown, Chicago who used the Model Cities Program to their own aims. Widening the frame further reveals the dozens of small cities and towns where limited aid had more impact. With these histories in hand, perhaps even the most improbable plans could yet still become reality.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Jay Cephas, Alison Isenberg, the referees, and the members of this section for their guidance on this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jeremy Lee Wolin

Jeremy Lee Wolin is a PhD candidate in History and Theory of Architecture at Princeton University. His dissertation examines how the concept of ‘human renewal’ evolved from the contributions that architects, planners, activists, and government administrators made to War on Poverty initiatives like the Model Cities Program. At Princeton, he is a Black Architects Archive research fellow and co-organizes the Asian American Studies Faculty-Graduate Reading Group and Lecture Series.

Notes

1 Reuther, “Letter to Richard Goodwin.”

2 Young Jr., To Be Equal, 26.

3 At times also called the Task Force on Urban Problems or on Cities, members also included chair Robert Wood, Walter Reuther, Whitney Young, Edgar Kaiser, William Rafsky, Charles Haar, and later, Ben Heineman, Chester Rapkin, and Kermit Gordon.

4 Robert Beauregard argues that the idea of ‘urban decline’ distracted from more radical criticisms of American social problems and limited possible solutions. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor has also argued that American federal framing of policy explicitly around class rather than race hindered it from effectively dealing with the discrimination at the heart of class inequality. That said, this article thinks with June Manning Thomas' argument that the application of Model Cities to so many Black neighbourhoods alone calls for scholars to revisit Model Cities based on their own local concerns. Beauregard, Voices of Decline, 21–3.; Taylor, Race for Profit, 86, 95.; Thomas, “Model Cities Revisited,” 147.

5 John Sasso and Priscilla Foley’s A Little Noticed Revolution told of the illustrious public service careers of former Model Cities staffers. This tempered earlier criticisms, like M. Christine Boyer’s judgment that the entire period was an attempt to ‘integrate and contain those with the most militant and disrupting demands.’ Sasso and Foley, A Little Noticed Revolution, xi.; Boyer, Dreaming the Rational City, 278.

6 Lillard published as Leo Lillard in JAIP 1969 but added the name Kwame later in life. This article opts to use his chosen name.

7 Haar, Between the Idea and the Reality, 35.

8 Reuther, “Memo to Lyndon B. Johnson,” 1–2.

9 “Notes on Model Cities.”

10 “Issues and Questions, Special Task Force on the Cities.”

11 Young Jr., To Be Equal, 28.

12 Young Jr., 214.

13 Young Jr., 140.

14 Weiss, Whitney M. Young, Jr., and the Struggle for Civil Rights, 150–153.

15 Young’s multidirectional, redistributive approach resonates with scholars like Robert S. Browne and Clarence Lang, while others like Boris Bittker, Randall Robinson, and Raymond Winbush define 1960s discourse on reparations around more direct calls, like James Forman’s “Black Manifesto.” Browne, “The Economic Basis for Reparations to Black America,” 99; Lang, “Reparations as a New Reconstruction”; Robinson, The Debt, 201; Bittker, The Case for Black Reparations, 2–3; Winbush, Should America Pay?, 14.

16 Robinson, “More Is Called For Than Social Protest and Desegregation.”

17 Dickerson, Militant Mediator, 2–3.

18 Young Jr., To Be Equal, 31.; Reuther, “Memo to Lyndon B. Johnson,” 290.

19 Reuther, “Memo to Lyndon B. Johnson,” 2.

20 Haar, Between the Idea and the Reality, 302.

21 Wood, “Letter from Robert Wood to Whitney Young.”

22 Weiss, Whitney M. Young, Jr., and the Struggle for Civil Rights, 154.; Pritchett, Robert Clifton Weaver and the American City, 285.

23 Haar, Between the Idea and the Reality, 73.

24 Reuther, “An Economy of Opportunity,” 8 January 1965.

25 Lichtenstein, Walter Reuther, 336.

26 Lichtenstein, 337.

27 Herrington, “Fraternally Yours,” 377.

28 “Letter from Detroit Model Cities Housing Committee to Southeast Citizens District Council.”

29 Carroll, “Humphrey Asks Marshall Plan for Cities.”; Flint, “Humphrey Urges New Aid to Poor.”

30 Humphrey”s inclusion was a crucial endorsement, as the vice president had been a vocal supporter of the Marshall Plan during its time. “Weaver Foresees Wider Cities Plan”; Tames, “The Cities … ; Humphrey on His ‘Marshall Plan’.” Offner, Hubert Humphrey, 57.; Young Jr., “Untitled Draft for Parents Magazine.”

31 Gillon, Separate and Unequal, 489.

32 Choi, “Podium Perspective: Whitney Young and the Black Architectural Imagination,” 68.

33 Young Jr., To Be Equal, 11.

34 Maier, Marshall Plan and Germany, 1–3.

35 Sasso and Foley, A Little Noticed Revolution, 8.

36 In addition to the Model Cities planning grants it awarded, HUD intended local agencies to carry out their programs by applying to categorical grants located across HUD and the Departments of Health, Education and Welfare; Labor; Agriculture; and Commerce; and the Office of Economic Opportunity and provided them with a guide to all potential funds. HUD also sent out a series of interagency directives that mandated non-HUD agencies set aside large portions of categorical funds specifically for Model Cities awardees. However, the uneven application of these categorical grants across Model Cities makes a total amount of funds used across Model Cities quite difficult to calculate. “Inter-Agency Relationships in Conducting Model Cities Programs.”

37 van den Berk, “The Intermediary Is the Message,” 413.; Grant, “The Tourist Trap,” 868; Vickers, Manipulating Hegemony, 46.

38 Howes, “Latin America and the Marshall Plan.”

39 Anderson, Bourgeois Radicals, 245–50.

40 Interview with Leo Lillard.

41 Birch, “Advancing the Art and Science of Planning Planners and Their Organizations 1909-1980,” 33.

42 Thomas, “Socially Responsible Practice,” 258, 272.

43 Scott Brown, “On Pop Art, Permissiveness, and Planning,” 186.

44 Friedmann, “Intention and Reality,” 187.

45 Arnstein, “A Ladder Of Citizen Participation.”

46 Lillard, “Model Cities, Model Airplanes, Model Trains,” 102.

47 Lillard, 102.

48 Others have argued that the Marshall Plan’s legacy hinged on rehabilitating the country most destroyed by the war. Maier, Marshall Plan and Germany, 3.; Castillo, “Domesticating the Cold War,” 262–63; Grünbacher, “Cold-War Economics,” 708.

49 Lillard, “Model Cities, Model Airplanes, Model Trains,” 103.

50 Shipler, “$65-Million U.S.Slum Aid Snarled in City Red Tape.”

51 Lillard, “Model Cities, Model Airplanes, Model Trains,” 104.

52 “Bookmobiles Aid New Borrowers.”

53 Navaz, “Museum Cancels Program.”

54 Clines, “Refuse Still Deep in Brownsville.”

55 “Metropolitan Briefs.”

56 Ferretti, “‘Call for Action’ Radio Services Are Now Carried in 22 Cities”; “Model Cities Help Is Due In Brooklyn”; “Brooklyn Slum a Backdrop for TV Training.”

57 “Fire Fighting Trainees Teach Safety to Students”; Johnson, “Brooklyn Fire Salvage Corps Gives Members On-Job Civil Service Training.”

58 Greenhouse, “Accord Reached; Day Camp Opens.”

59 Goldman, “In Brooklyn, The Poor Get Special Court Help.”

60 Between the Word and the Deed.

61 What Is The City But The People?

62 Between the Word and the Deed.; Lillard, “Model Cities, Model Airplanes, Model Trains,” 103.

63 Thabit, How East New York Became a Ghetto, 138.

64 Cardona, “Kwame Lillard, Nashville Civil Rights Leader And Former Metro Councilmember, Dies At 81.”

65 Gordon Hyatt, Between the Word and the Deed … ; Thabit, How East New York Became a Ghetto, 140.

66 Fitzgerald, “Metcalfe ‘The Man’ Part II.”

67 Chrisman, “The Black Scholar: The First Forty Years.”

68 Early academic contributors included San Francisco State University Black Studies founding director Nathan Hare, Cornell University Africana Studies founding director James Turner, future Howard University president Joyce Ladner, and Hunter College sociologist Alphonso Pinkney. Activists and public figures included Malcolm X, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Angela Davis, Stokely Carmichael, Bobby Seale, and Imamu Amiri Baraka.

69 Geary, Beyond Civil Rights, 125; Towns, “In Search of the (Black) International.”

70 Ladner and Stafford, “Comprehensive Planning and Racism,” 68.

71 Ladner and Stafford, “Black Repression in the Cities,” 38.

72 Ladner and Stafford, “Comprehensive Planning and Racism,” 71.

73 Ladner and Stafford, “Black Repression in the Cities,” 39.

74 These included Guinean President Sékou Touré and Beninese Minister of Culture Stanislas Adotevi (Issue 1); then first-term Brooklyn congresswoman Shirley Chisholm (Issue 3); and Urban Research Institute founder Dempsey Travis, then urban affairs PhD student Walter Stafford, and Mayor of Gary, Indiana Richard G. Hatcher (Issue 6).

75 Redmond, “Barbequed Cong.”

76 Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism, ix.

77 Nkrumah, x.

78 Turner’s understanding arose from his own work founding Cornell University’s Africana Studies Research Center, framed around the label ‘Africana’ precisely to frame Black liberation as a global phenomenon. Turner, “Blacks in the Cities,” 9.

79 Columbia Revolt. Bradley, Harlem vs. Columbia University, 113–14. “Blacks Organize Course Reform.” “Midnight Smoker.”

80 Metcalfe, “Chicago Model Cities and Neocolonization,” 25.

81 Metcalfe, 29.

82 Balto, Occupied Territory, 248.

83 Ziemba, “Daley Tells Plans for Offices to Serve 4 Model Cities Areas.”

84 Crimmins and Ziemba, “Democratic Slates Capture 3 Model City Councils.”

85 Negronida and Honchar, “Housing Efforts Feeble, Costly.”

86 In response to requests for more parks and park programs for residents to use as they wished, DHR and its Leisure Time Councils instead purchased equipment intended to build clubs and community groups. Negronida and Honchar, “Model Cities Needy Play By Chicago Rules.”

87 “What Is Model Cities?”

88 “Election Announcement ‘VOTE FOR FREEDOM’.”

89 “TWO’s Model Cities Plan.”

90 Metcalfe, “Chicago Model Cities and Neocolonization,” 27.

91 “The Parent Child Center: Learning Together.”

92 Negronida and Honchar, “Education Main Model Cities Focus.”

93 “Provident Hospital Holds Health Services Workshop.”

94 Metcalfe Jr., “Chicago Model Cities and Neocolonization,” 29.; “Unique Training Programs ’pay’ for Themselves.”

95 “Model Cities Class Trains Residents for Clinical Duties”; “Provident Hospital Holds Health Services Workshop.”

96 Negronida and Honchar, “Patronage, Favoritism Mark Model Cities Here.”

97 Negronida and Honchar, “Model Cities Business Plans Snarled from Start.”

98 “Laud Community Service Aides.”

99 Acting Is the Art.

100 Lacey, “Says Model Cities Aides Helping Police.”

101 Metcalfe Jr., “Chicago Model Cities and Neocolonization,” 29.

102 Balto, Occupied Territory, 247.

103 Metcalfe Sr., “The Misuse of Police Authority In Chicago,” 22.

104 Nixon replaced Model Cities with a system of revenue sharing that withdrew even the Johnson administration’s limited federal mandates while attempting to totally erase mentions of racial discrimination behind the guise of poverty. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor also argues that while Black elected leadership increased during the late 1960s and 1970s, the welfare state did not. “Metcalfe Urges Nixon to Restore Funds Cut for Social Service.”; Taylor, From #Blacklivesmatter to Black Liberation, 248.

105 Fitzgerald, “Metcalfe ‘The Man’ Part II.”

106 Biles, Mayor Harold Washington, 23–35.

107 Muwakkil, “A Father’s Life.”

108 “Medics Protest Cutbacks.”; “Gardner Cites Rising Idleness.”

109 Saunders, “On Peace and Poverty.”

110 “Model Cities Projects.”

111 Sasso and Foley, A Little Noticed Revolution, xi.

References

- Acting Is the Art. Chicago Department of Human Resources, 1970.

- Anderson, Carol. Bourgeois Radicals: The NAACP and the Struggle for Colonial Liberation, 1941–1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Arnstein, Sherry R. “A Ladder Of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35, no. 4 (1969): 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Balto, Simon. Occupied Territory: Policing Black Chicago from Red Summer to Black Power. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

- Beauregard, Robert A. Voices of Decline: The Postwar Fate of US Cities. London: Taylor & Francis, 2002.

- Berk, Jorrit van den. “The Intermediary Is the Message: US Public Diplomacy and the Marshall Plan Productivity Drive in the Netherlands, 1948–52.” Journal of Contemporary History 56, no. 2 (2021): 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009420940027.

- Between the Word and the Deed. New York City Model Cities Program, 1970.

- Biles, Roger. Mayor Harold Washington: Champion of Race and Reform in Chicago. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5406/j.ctvvnhdn.

- Birch, Eugenie Ladner. “Advancing the Art and Science of Planning Planners and Their Organizations 1909–1980.” Journal of the American Planning Association 46, no. 1 (1980): 22–49.

- Bittker, Boris. The Case for Black Reparations. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1972.

- Boyer, M. Christine. Dreaming the Rational City: The Myth of American City Planning. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986.

- Bradley, Stefan M. Harlem vs. Columbia University: Black Student Power in the Late 1960s. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

- Browne, Robert S. “The Economic Basis for Reparations to Black America.” The Review of Black Political Economy 21, no. 3 (1993): 99–110.

- Cardona, Nina. “Kwame Lillard, Nashville Civil Rights Leader And Former Metro Councilmember, Dies At 81.” WPLN News, 21 December 2020. https://wpln.org/post/kwame-lillard-nashville-civil-rights-leader-and-former-metro-councilmember-dies-at-81/.

- Carroll, Maurice. “Humphrey Asks Marshall Plan for Cities.” The New York Times, April 2, 1976.

- Castillo, Greg. “Domesticating the Cold War: Household Consumption as Propaganda in Marshall Plan Germany.” Journal of Contemporary History 40, no. 2 (2005): 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009405051553.

- Chicago Defender. “Gardner Cites Rising Idleness.” March 26, 1973.

- Chicago Defender. “Laud Community Service Aides.” October 12, 1972.

- Chicago Defender. “Medics Protest Cutbacks.” March 12, 1973.

- Chicago Defender. “Metcalfe Urges Nixon to Restore Funds Cut for Social Service.” February 13, 1973.

- Chicago Defender. “Model Cities Projects.” March 27, 1973, sec. In Our Opinion.

- Chicago Defender. “Provident Hospital Holds Health Services Workshop.” November 3, 1971.

- Chicago Defender. “Unique Training Programs ‘pay’ for Themselves.” February 19, 1973.

- Chicago Tribune. “Model Cities Class Trains Residents for Clinical Duties.” November 12, 1970.

- Choi, Rebecca. “Podium Perspective: Whitney Young and the Black Architectural Imagination.” Ardeth (2020): 66–77.

- Chrisman, Robert. “The Black Scholar: The First Forty Years.” The Black Scholar 41, no. 4 (2011): 2–4.

- Clines, Francis X. “Refuse Still Deep in Brownsville.” The New York Times, June 30, 1970.

- Columbia Revolt. Documentary. C-SPAN, 1968. https://www.c-span.org/video/?445109-2/columbia-revolt.

- Columbia Spectator. “Blacks Organize Course Reform.” March 12, 1969, vol. CXIII, no. edition.

- Columbia Spectator. “Midnight Smoker.” April 30, 1969, vol. CXIII, no. 108 edition.

- Crimmins, Jerry, and Stanley Ziemba. “Democratic Slates Capture 3 Model City Councils.” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1970.

- Dickerson, Dennis C. Militant Mediator: Whitney M. Young Jr. 1st ed. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1998.

- “Election Announcement ‘VOTE FOR FREEDOM’.” The Woodlawn Organization, 1970. The Woodlawn Organization Records, Box 7, Folder 3. Chicago History Museum.

- Ferretti, Fred. “‘Call for Action’ Radio Services Are Now Carried in 22 Cities.” The New York Times, January 30, 1970.

- Fitzgerald, Louis A. “Metcalfe ‘The Man’ Part II,” Chicago Defender, January 26, 1976.

- Flint, Jerry M. “Humphrey Urges New Aid to Poor.” The New York Times, August 3, 1967.

- Friedmann, John. “Intention and Reality: The American Planner Overseas.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35, no. 3 (1969): 187–193.

- Geary, Daniel. Beyond Civil Rights: The Moynihan Report and Its Legacy. Reprint ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

- Gillon, Steven M. Separate and Unequal: The Kerner Commission and the Unraveling of American Liberalism. Illustrated ed. New York: Basic Books, 2018.

- Goldman, Ari L. “In Brooklyn, The Poor Get Special Court Help.” The New York Times, July 29, 1973.

- Grant, Mariel. “The Tourist Trap: Great Britain, Postwar Recovery, and the Marshall Plan.” Journal of British Studies 60, no. 4 (2021): 867–889.

- Greenhouse, Linda. “Accord Reached; Day Camp Opens.” The New York Times, July 6, 1972.

- Grünbacher, Armin. “Cold-War Economics: The Use of Marshall Plan Counterpart Funds in Germany, 1948–1960.” Central European History 45, no. 4 (2012): 697–716.

- Haar, Charles Monroe. Between the Idea and the Reality: A Study in the Origin, Fate, and Legacy of the Model Cities Program. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1975.

- Herrington, Susan. “Fraternally Yours: The Union Architecture of Oskar Stonorov and Walter Reuther.” Social History 40, no. 3 (2015): 360–384.

- Howes, Robert. “Latin America and the Marshall Plan: The Critique from Brazil of Roberto Simonsen.” Journal of Transatlantic Studies 19, no. 4 (2021): 441–464.

- “Inter-Agency Relationships in Conducting Model Cities Programs,” 7 December 1967. Legislative Background Files, Model Cities Box 2, Folder 3. Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Interview with Leo Lillard, 3 January 1985. Eyes on the Prize Collection. Washington University in St. Louis. http://repository.wustl.edu/concern/videos/tm70mw79f.

- “Issues and Questions, Special Task Force on the Cities,” 9 October 1965.: Legislative Background Files, Model Cities Box 1, Folder 4. Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Johnson, Rudy. “Brooklyn Fire Salvage Corps Gives Members On-Job Civil Service Training.” The New York Times, March 25, 1973.

- Lacey, Ted. “Says Model Cities Aides Helping Police.” Chicago Daily Defender, February 19, 1970.

- Ladner, Joyce, and Walter W. Stafford. “Black Repression in the Cities.” The Black Scholar 1, no. 6 (1970): 38–52.

- Ladner, Joyce, and Walter W. Stafford. “Comprehensive Planning and Racism.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35, no. 2 (1969): 68–74.

- Lang, Clarence. “Reparations as a New Reconstruction.” Against the Current 102. January 2003.

- “Letter from Detroit Model Cities Housing Committee to Southeast Citizens District Council,” February 6, 1969. Mel Ravitz Papers, Box 20, Folder 6. Walter Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs.

- Lichtenstein, Nelson. Walter Reuther: The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995.

- Lillard, Leo E. “Model Cities, Model Airplanes, Model Trains.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35, no. 2 (1969): 102–104.

- Maier, Charles S. Marshall Plan and Germany. 1st ed. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 1992.

- Metcalfe Jr., Ralph H. “Chicago Model Cities and Neocolonization.” The Black Scholar 1, no. 6 (1970): 23–30.

- Metcalfe, Ralph H. “Chicago Model Cities and Neocolonization.” The Black Scholar 1, no. 6 (1970): 23–30.

- Metcalfe Sr., Ralph H. “The Misuse of Police Authority In Chicago.” Chicago, Illinois, July 1972. https://chicagopatf.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/metcalfe-report-1972.pdf.

- Muwakkil, Salim. “A Father’s Life.” Chicago Tribune, 18 October 1999, sec. 1.

- Navaz, Shuja. “Museum Cancels Program.” The New York Times, May 12, 1974.

- Negronida, Peter, and Cornelia Honchar. “Education Main Model Cities Focus.” Chicago Tribune, February 23, 1972.

- Negronida, Peter, and Cornelia Honchar. “Housing Efforts Feeble, Costly.” Chicago Tribune, February 24, 1972.

- Negronida, Peter, and Cornelia Honchar. “Model Cities Business Plans Snarled from Start.” Chicago Tribune, February 25, 1972.

- Negronida, Peter, and Cornelia Honchar. “Model Cities Needy Play By Chicago Rules.” Chicago Tribune, February 26, 1972.

- Negronida, Peter, and Cornelia Honchar. “Patronage, Favoritism Mark Model Cities Here.” Chicago Tribune, February 21, 1972.

- Nkrumah, Kwame. Neo-Colonialism. London: Panaf Books, 1963. https://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/nkrumah/neo-colonialism/introduction.htm.

- “Notes on Model Cities,” October 14, 1968.: Legislative Background Files, Model Cities Box 1, Folder 6. Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Offner, Arnold A. Hubert Humphrey: The Conscience of the Country. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

- Pritchett, Wendell E. Robert Clifton Weaver and the American City: The Life and Times of an Urban Reformer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Redmond, Eugene B. “Barbequed Cong: OR We Laid MY LAI Low.” The Black Scholar 1, no. 6 (1970): 53–53.

- Reuther, Walter P. “An Economy of Opportunity,” January 8, 1965. Reel 1, Folder 0364. War on Poverty Papers Microfilm.

- Reuther, Walter P. “Letter to Richard Goodwin,” June 4, 1965. Legislative Background Files, Model Cities Box 1, Folder 4. Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Reuther, Walter P. “Memo to Lyndon B. Johnson,” May 13, 1965. Legislative Background Files, Model Cities Box 1, Folder 6. Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Robinson, Layhmond. “More Is Called For Than Social Protest and Desegregation.” The New York Times, October 11, 1964.

- Robinson, Randall. The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks. Reprint ed. New York: Plume, 2001.

- Sasso, John, and Priscilla Foley. A Little Noticed Revolution: An Oral History of the Model Cities Program and Its Transition to the Community Development Block Grant Program. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Public Policy Press, Institute of Governmental Studies, University of California, 2005.

- Saunders, Warner. “On Peace and Poverty.” Chicago Defender, February 27, 1973.

- Scott Brown, Denise. “On Pop Art, Permissiveness, and Planning.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35, no. 3 (1969): 184–186.

- Shipler, David K. “$65-Million U.S.Slum Aid Snarled in City Red Tape.” The New York Times, January 11, 1971.

- Tames, George. “The Cities … Humphrey on His ‘Marshall Plan’.” The New York Times, August 20, 1967.

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. From #Blacklivesmatter to Black Liberation. 1st ed. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2016.

- Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

- Thabit, Walter. How East New York Became a Ghetto. Revised ed. New York: New York University Press, 2005.

- The New York Times. “Bookmobiles Aid New Borrowers.” March 21, 1971.

- The New York Times. “Brooklyn Slum a Backdrop for TV Training.” May 2, 1971.

- The New York Times. “Fire Fighting Trainees Teach Safety to Students.” May 23, 1971.

- The New York Times. “Metropolitan Briefs.” July 18, 1972.

- The New York Times. “Model Cities Help Is Due In Brooklyn.” June 2, 1970.

- The New York Times. “Weaver Foresees Wider Cities Plan.” August 14, 1967.

- “The Parent Child Center: Learning Together.” Model Cities-Chicago Committee on Urban Opportunity, 1972. Municipal Reference Collection. Chicago Public Library.

- Thomas, June Manning. ‘Model Cities Revisited: Issues of Race and Empowerment’. In Urban Planning and the African American Community, edited by June Manning Thomas and Marsha Ritzdorf, 143–66. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 1997.

- Thomas, June Manning. “Socially Responsible Practice: The Battle to Reshape the American Institute of Planners.” Journal of Planning History 18, no. 4 (2019): 258–281.

- Towns, Armond R. “In Search of the (Black) International: The Black Scholar and the Challenge to Communication and Media Studies.” Communication Theory, 2023. qtad001.

- Turner, James. “Black in the Cities: Land and Self-Determination.” The Black Scholar 1, no. 6 (1970): 9–13.

- “TWO’s Model Cities Plan,” 1969. The Woodlawn Organization Records, Box 5, Folder 9. Chicago History Museum.

- Vickers, Rhiannon. Manipulating Hegemony: State Power, Labour and the Marshall Plan in Britain. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000.

- Weiss, Nancy Joan. Whitney M. Young, Jr., and the Struggle for Civil Rights. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

- “What Is Model Cities?” The Woodlawn Organization, 1970. The Woodlawn Organization Records, Box 5, Folder 9. Chicago History Museum.

- What Is The City But The People? New York: New York City Department of City Planning, 1969.

- Winbush, Raymond. Should America Pay?: Slavery and the Raging Debate on Reparations. Reprint ed. New York, NY: Amistad, 2003.

- Wood, Robert C. “Letter from Robert Wood to Whitney Young,” 29 December 1965. Box 59, Folder 1965–66 Committee Affiliations. Whitney M. Young, Jr. Papers, Columbia University Rare Books and Manuscripts Library.

- Young Jr., Whitney M. To Be Equal. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964.

- Young Jr., Whitney M. “Untitled Draft for Parents Magazine,” January 1968. Box 206, Articles 1963–1970. Whitney M. Young, Jr. Papers, Columbia University Rare Books and Manuscripts Library.

- Ziemba, Stanley. “Daley Tells Plans for Offices to Serve 4 Model Cities Areas.” Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1970.