ABSTRACT

In January 1966, US President Lyndon Johnson proposed the Model Cities programme to ‘improve the quality of urban life’ in the nation’s poorest areas through comprehensive action and citizen participation. That same month, John Lindsay became mayor of New York with a platform to create a more equitable city. Toward this end, Lindsay’s administration rejected earlier urban renewal approaches, prioritizing infill construction on vacant sites and reusing existing buildings, all while including local communities in the planning process. Eugenia Flatow spearheaded this ‘vest-pocket and rehabilitation programme’ as a ‘head start’ to future Model Cities funding. As she commissioned Raymond & May, Walter Thabit, Jonas Vizbaras, and Fisher/Jackson with housing plans for Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Harlem, she was acutely aware of the resulting tension between a desired democratic process and the timely delivery of the product. A close reading of archival materials reveals how these planners responded in very different ways to the prompt. The governmental programme had created a space of possibility for rethinking the relationship of product and process in planning through the specificity of housing design. The plans also highlighted the paradox in attempting to effect socio-economic change through housing supply, one that still resonates today.

Introduction: an appointment letter, November 1966

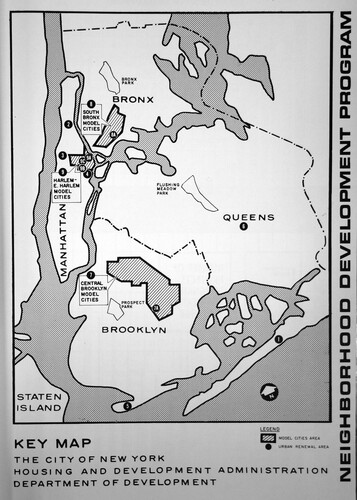

On 30 November 1966, almost exactly one month after President Lyndon Johnson had signed the Model Cities programme into law, New York City Mayor John Lindsay sent identical appointment letters to five planning consultants with a very precise task. These firms were to work with residents of so-called vest-pocket housing and rehabilitation study areas to site 1600 units of housing.Footnote1 Rather than large-scale slum clearance, which had come under significant political pressure, the idea was to promote infill construction on vacant sites together with the reuse of existing buildings. In addition, citizens of these areas were to be involved in the planning. Federal funding for the low- and moderate-income housing had already been allocated and a plan approved by the Board of Estimate in June 1966. A motivator for four of these five studies was to get a ‘head start’ on Model Cities planning.Footnote2 Lindsay’s administration was in the process of designating three ‘Model Cities Neighborhoods’ in Central Brooklyn, the South Bronx, and Harlem-East Harlem (). The vest-pocket housing studies were to be a small prelude to later, more comprehensive planning efforts there.

Figure 1. Map locating the three Model Cities Areas in New York, published in Community Development Program: A Progress Report, 1968. Source: NYC Municipal Library.

President Johnson had proposed Model Cities as a part of his Great Society agenda in January 1966, just as Lindsay assumed office as mayor. Johnson’s goal was to counteract a wave of racial unrest with a programme that would be ‘more comprehensive, more concentrated, than any that has gone before.’Footnote3 Coordinated investment in social and physical programmes in ‘Model Cities Neighborhoods’ could, so the theory went, resolve their socio-economic problems within five years. The newly created Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) would administer grants covering 80% of programme costs, the rest matched by municipalities. How the money would be spent – whether on physical development, education, healthcare, job training, sanitation, or the arts, to name just some options – was to be decided by local residents. Model Cities was an attempt to move beyond urban renewal, which had over-emphasized the role of the physical environment, toward a more holistic approach to fighting poverty. By giving mayors the lead in how the programmes would be structured in their cities, Model Cities was also a corrective to the 1964 Community Action Programme which had channelled federal funding directly to community groups. The new federal programme aligned philosophically with Mayor Lindsay’s agenda and promised to inject substantial funding into its implementation.

To catalyze a programme deliberately conceived as ‘comprehensive’ with housing construction was a contradictory endeavour, however. Lindsay likely hoped that new dwellings would create tangible results and trust in new governmental initiatives. The lack of affordable and adequate housing accessible to all of the city’s racial groups was a persistent concern amidst New York’s rapidly changing economy in the post-war years, and the city was nationally at the forefront of creating new housing programmes.Footnote4 But housing construction was slow and expensive as urban renewal had shown; even if federal funding had already been allocated, planning with residents would take time, land would have to be acquired, some residents relocated, bids obtained, construction managed – and ultimately the new housing would serve only a few households. If the goal was to create trust in a new planning process, betting on the product of housing to get there bore a certain risk.

Lindsay’s appointment letter to the selected consultants articulated an awareness of this fundamental tension in the vest-pocket housing approach and by extension the larger Model Cities undertaking in New York: how to balance ‘product’ and ‘process,’ or speed in the production of tangible results, on the one hand, while, on the other hand, adequately involving the residents of the city’s most impoverished and disinvested areas. In an attempt to balance competing demands, the city gave the planners only 90 days to work with local residents and deliver their recommendations, and another 90 days to publish a report. At the same time, it stressed that planners needed to give ‘the community maximum opportunity to review and influence’ the recommendations. A ‘preamble’ outlining this tension between product and process emphasized the desire to achieve ‘reasonably broad local consensus’ while avoiding ‘necessarily false finality and definiteness.’ Likely written by Eugenia Flatow, at the time assistant administrator in the new Housing and Development Administration (HDA), in consultation with her boss, Jason R. Nathan, and Donald Elliot, chairman of the City Planning Commission, the letter stressed that planners were to seek ‘early consensus only with respect to the recommendations dealing with the low-rent [public] and 221d3 [moderate-income] housing,’ and avoid considering other forms of housing or other programmes.Footnote5 Many other aspects of the task were also precisely defined: planners were to conduct surveys of existing conditions, articulate ‘planning objectives’ in conjunction with the community, and to designate sites. Others were left surprisingly open: how neighbourhood participants would be selected or what form the process would take was not spelled out. What was clear: even if this was to be a novel participatory process, nothing was to delay delivery of a predetermined product.

Lindsay appointed consultants with unusually diverse approaches to the question of product and process in housing: Raymond & May Associates, a planning firm with a long track record of urban renewal and suburban planning; Jonas Vizbaras, an architect with expertise in high-end residential and new town design; advocacy planner Walter Thabit, well-known for his work with residents opposing urban renewal plans; and Fisher/Jackson, a practice with expertise in industrialized construction and computational design. How this seemingly eclectic line up came together is unclear. But the result was that the city, prompted by the advent of Model Cities, promoted very different planning philosophies in a way that was rarely seen before or perhaps since. Model Cities’ vest-pocket and rehabilitation programme thus created a space of possibility in which to debate the conflicting demands of process and product in planning through the specificity of architecture.

This article provides a close reading of the four vest-pocket housing and rehabilitation studies conducted for future Model Cities neighbourhoods between November 1966 and June 1967. The analysis is based on archival materials found primarily in Eugenia Flatow’s papers, contextualized by reports in the contemporary press, interviews with surviving protagonists, as well as recent scholarship on the period. The focus of the analysis is on the space of possibility created by the planning effort: it is concerned with the plans themselves, not the implementation stage that followed. Doing so is an attempt to avoid the success-or-failure, idea-and-reality narratives that have characterized much Model Cities scholarship to date.Footnote6 Instead, I argue that a plan itself, even if not implemented in the way it was proposed, is a viable deliverable in a governmentally initiated and funded planning project. In fact, all four planners involved in the vest-pocket housing studies pushed the envelope on what constitutes a deliverable. In doing so, they articulated the inevitable trade-offs between process and product in ways that helped the city and citizens understand what was at stake.

The article contributes to planning history in two ways. First, the studies’ diversity complicates linear narratives of post-war urban renewal and associated housing development in the United States. These narratives often sketch a chronology from a top-down ‘urban renewal order’ of which large-scale public-sector housing was one problematic part, to a bottom-up process of small-scale housing production demanded by community-based and private-sector actors.Footnote7 These plans reveal that large, governmental programmes like Model Cities were in fact essential in creating the incremental form of housing design and development that still characterizes planning policy fifty years later.

Second, the article foregrounds several little-known or largely forgotten professionals who were instrumental in advancing the debates around product and process in planning, contributing to a better understanding of how Model Cities played out on the ground. Primary among them are Eugenia Flatow and Barry Jackson. Both were trailblazers in their fields in the mid-1960s: she as a white woman in a cabinet-level position, he as an entrepreneurial Black architect working in practice and academia. Despite being outsiders, they were both committed to change from within. Unlike her contemporary Jane Jacobs, Flatow embraced government to promote affordable, racially integrated, and better designed housing.Footnote8 Jackson, at the highpoint of Black separatism, was never politically radical; he embraced education and entrepreneurship as paths for social mobility. Flatow and Jackson thus embodied a key tenet of Model Cities and vest-pocket housing: they sought reform, not revolution. A focus on their work thus also illuminates the promises and paradoxes of the Model Cities programme itself.

The article proceeds in five sections. After discussing origins of the vest-pocket housing idea a section each is devoted to the four plans, organized from approaches prioritizing the physical product to those stressing the primacy of process. Jackson’s proposals receive most attention given their radicality. The article concludes with a reflection on what occurred once the plans were adopted in June 1967 and the space of possibility they described.

Eugenia Flatow and the case for vest-pocket housing

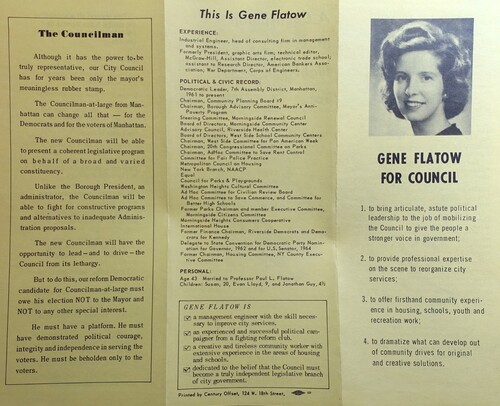

Eugenia Flatow was uniquely suited to take on the challenge of turning the multiple ideas that had been circulating around vest-pocket housing into a governmental programme. In early 1966, Lindsay, a newly elected liberal Republican, tapped the reform Democrat to help reorganize the city’s housing agencies. She had run unsuccessfully for an at-large city council seat that fall. An industrial engineer by training, a mother, manager of a print shop by day and active in local politics by night, her views on housing and urban development were already well articulatedFootnote9 (). A campaign pamphlet outlined a comprehensive view in six main areas – Jobs, Code Enforcement, Civil Rights, Schools, Urban Renewal, and Parks – with a particular focus on the centrality of physical space. Of urban renewal she demanded:

Slow down all demolition of structurally sound buildings that does not increase family housing supply until relocation burden is eased. Develop new tools for rehabilitating dwellings … Build on vacant land. … Relax income restrictions to stabilize project tenancies. Liberalize entrance requirements for public housing.Footnote10

Figure 2. Eugenia Flatow, pamphlet produced for her candidacy for an at-large seat in New York’s City Council, 1965. Source: NYHS.

Vest-pocket housing was not a new idea. Who coined the term in urban planning is unclear; the reference to a small pocket applied to men's shirts or women's jackets emerged to describe parcels smaller than a full block.Footnote12 Considering such infill sites as viable for development was a major departure from the theory underlying urban renewal which stressed that improving housing conditions would never be effective on a parcel-by-parcel approach.Footnote13 By 1966, the vest-pocket concept was well-established and embraced by a variety of players toward different ends. First and foremost, there was the economic argument. Working with small, irregular sites rather than full blocks could significantly lower the cost and time for the acquisition and assembly of large, contiguous sites. This pragmatic approach was first used by the Housing Authority in 1955 for public housing;Footnote14 by 1962, a third of its developments, most as high-rise construction, were built on vest-pocket sites.Footnote15

Over time, the vest-pocket approach began to pair new construction with rehabilitation. Again, this was to lower cost, but also to come to terms with the pressing issue of how and where to relocate the residents of demolished buildings. The 1960 Panuch Report, commissioned by Lindsay’s predecessor, Democrat Robert F. Wagner, Jr., advocated for saving ‘structurally sound buildings,’ as well as ‘the systematic development of vest-pocket housing … to house relocated families as well as welfare clients who now must be herded in substandard but expensive housing.’Footnote16 In other words, already in 1960, the city recommended infill construction and the reuse of existing as a preferred strategy to meet resident needs.

Within a few years, advocates saw the promise of vest-pocket housing not just to generate housing in a less costly way, but to improve entire neighbourhoods. One of the first such large-scale applications was the West Side Urban Renewal Area in Manhattan. Designated in 1962, the plan encompassed an array of strategies renovating existing late-nineteenth century brownstones along side streets for both public housing and for individual homeownership; building new high-rise rental and cooperative housing along the avenues; and siting new buildings on infill sites where available.Footnote17 The strategy was not without critics: an older generation of reformers including Edith Wood and Albert Mayer continued to argue that wholesale, comprehensive planning was the only way to counter the deleterious interests of multiple private property owners.Footnote18 And yet the process of vest-pocket development on the Upper West Side was considered so successful that its application spread to other urban renewal areas in New York, including West Farms, the Bronx and Far Rockaway, Queens.

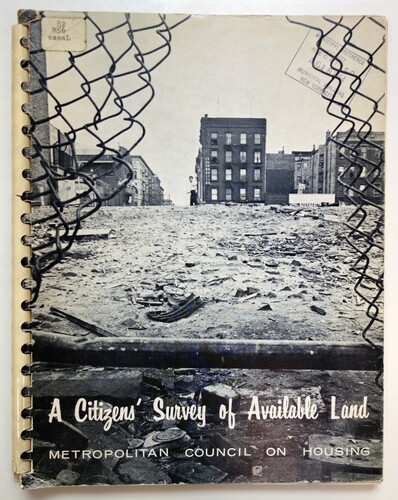

By the mid-1960s, the vest-pocket argument expanded even further to prioritize racial and economic integration. In 1964, the Metropolitan Council on Housing, an alliance of civic organizations, made that case in A Citizens’ Survey of Available Land (). The publication opened with a multi-pronged critique:

This report is a direct challenge to New York City's housing and planning bureaucracies. It exposes their traditional approaches to the housing problem, their stereotyped, unimaginative and ineffective ways of dealing with today’s problems. It underlines their indifference to the needs of low-income and minority groups, their scandalous unwillingness to undertake a real vest-pocket programme—the one programme which could rebuild local communities for the people who now live in them.Footnote19

Figure 3. Metropolitan Council on Housing, A Citizens’ Survey of Available Land, 1964, cover. Source: NYC Municipal Library.

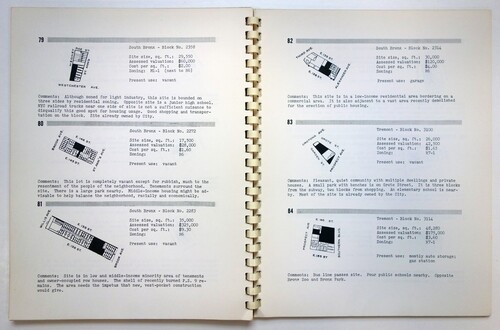

Figure 4. Metropolitan Council on Housing, A Citizens’ Survey of Available Land, 1964, spread showing South Bronx sites later selected in the Mott Haven vest-pocket study. Source: NYC Municipal Library.

In early 1966, then, several conditions aligned to pair vest-pocket housing with Model Cities: broader aesthetic and social ideas of what vest-pocket housing could accomplish, already allocated funding for low-income public as well as moderate-income Section 221d3 rental housing, and a promise of forthcoming Model Cities money. In addition, vest-pocket housing dovetailed with Lindsay’s aim to insert low-income housing into higher-income areas, a strategy that became known as ‘scattered site housing.’Footnote21

The Administration’s housing programme has two objectives: to help rebuild and redevelop existing slums and to open housing opportunities in sound, predominantly white, middle-income neighborhoods for those now confined to the City's ghettos.Footnote22

Plan 1: Raymond & May’s ‘modular’ housing type for Bedford-Stuyvesant

Hiring the White Plains-based ‘urban renewal and planning’ firm Raymond & May for one of two study areas in the future Central Brooklyn Model Cities Neighborhood was not a surprising move. The firm had significant experience with the urban renewal establishment.Footnote23 In the years immediately before their hire, however, founding partner George M. Raymond had begun to question the city’s planning policies.Footnote24 As chair of Pratt Institute’s planning programme, he co-founded the Pratt Center for Community Improvement in 1963 to establish working relationships with local organisations in Brooklyn.Footnote25 To Flatow, Raymond must have embodied the perfect balance between a dedication to product, while increasingly looking at process.Footnote26

In 1966, ‘Bedford-Styuvesant’ was a large and loosely defined neighbourhood, majority Black and economically diverse. It was home to a Black middle-class who owned their homes, mainly brownstones, and were represented by well-organized block organisations, and to poorer residents of public housing, perceived by the homeowners as a threat. Community organisers had long forwarded innovative proposals to rehabilitate existing, rather than building new housing.Footnote27 Raymond, who took the lead in the process, met weekly between October 1966 and February 1967 with the ‘Bedford-Stuyvesant Better Housing Committee,’ whose members drew from various existing organisations.Footnote28 In its site selection, the committee chose to avoid public housing, urban renewal, or code enforcement areas, deciding instead on ‘protecting the areas of sound housing from surrounding blight.’Footnote29 Sites were thus clustered along seven blocks of a main avenue, siting low- and moderate-income housing on separate blocks. New housing was to provide large family-units enhanced with community facilities, such as libraries and schools.

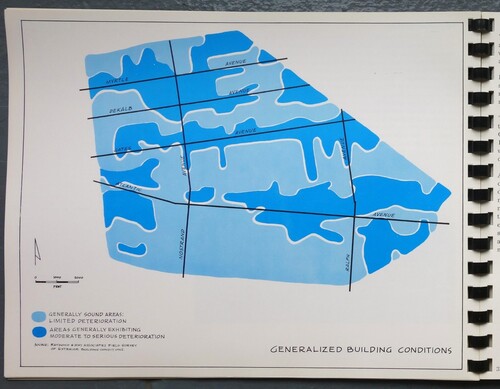

The report – 78 landscape-format, spiral-bound pages – makes maximum use of bold colours and modern typefaces.Footnote30 The full-page analytical maps are printed in two-tone cyan, and the abstracted organic shapes situate the study area within the city’s larger networks and highlight issues such as deterioration (). Photographs convey either the beauty of brownstone-lined streetscapes or the deleterious effect of vacant sites. Proposed interventions are presented in black and white sketches drawn at street level, while full-color renderings show in aerial view the hoped-for results in the aesthetic of a modern townscape (). The visual similarity between this proposal and a new town on Staten Island that Raymond & May was simultaneously working is likely not a coincidence in the quest to address middle-class sensitivities.Footnote31

Figure 5. Raymond & May, Vest Pocket Housing in Bedford-Stuyvesant, 1968, two-tone map indicating level of deterioration in the study area. Source: NYHS.

Figure 6. Raymond & May, Vest Pocket Housing in Bedford-Stuyvesant, 1968, full-colour aerial view of proposed new low- and midrise housing, community facilities, and parking. Source: NYHS.

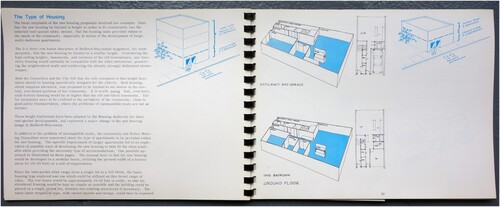

The report stresses homeownership of brownstones as the area's strongest asset. As a result, Raymond posits the predominant housing type as the main vehicle for community coherence. His recommendations involve a single product: a ‘modular’ housing type ‘utilizing the width of a brownstone lot (18–25 feet) as the unit of organization.’Footnote32 Easily legible axonometric diagrams explain possible variations of the new two-family rowhouses: the ground floor could either contain a studio apartment with a garage and a four- or five-bedroom apartment above; or a larger one- or two-bedroom unit below (). The only exception to the stipulated four-story-maximum height are six-story elevator buildings for the elderly.

Figure 7. Raymond & May, Vest Pocket Housing in Bedford-Stuyvesant, 1968, one of several spreads explaining possible configurations of the ‘modular’ housing type. Source: NYHS.

Raymond & May’s process had thus provided already well-organized residents the chance to advance their vision of their neighbourhood through a product they knew. A replicable housing type was to guarantee middle-class amenities, including individual parking garages, as well as beloved architectural features, like the bay window. As Raymond put it to Flatow,

This programme has been truly innovative on at least two broad levels: in conducting a planning program with the people … [and] in pioneering a new concept in … housing, based on respect for the existing scale of a community and the provision of a housing type geared to the hopes and wishes of the neighborhood itself.Footnote33

Plan 2: Jonas Vizbaras’s ‘block action’ for Mott Haven

For the Mott Haven study area in the South Bronx, the city engaged Jonas Vizbaras. The architect’s expertise was in building design; how he was selected is unclear. From 1962 to 1966, Vizbaras was associate partner of Whittlesey & Conklin, a firm known for private apartment buildings in Manhattan, but also as master planners of Reston, Virginia, the much-celebrated so-called first new town in the United States, for which he was a lead designer.Footnote35 This background would show in his approach to his study area.

Mott Haven was the smallest and most clearly bounded of the four study areas, characterized by multi-family rental housing including rowhouses and old-law and new-law tenements, as well as four large public housing developments. It was home to a rapidly changing population of immigrants; most recently, Puerto-Ricans had become the dominant group. Vizbaras began meeting weekly with a newly constituted ‘Mott Haven Plan Committee’ in February 1967, although which existing organizations it drew on is unclear.Footnote36 In contrast to Raymond’s report, Vizbaras’s does not reveal what was debated by committee members or how decisions were made. Archival records are missing. There is only the report to go by.

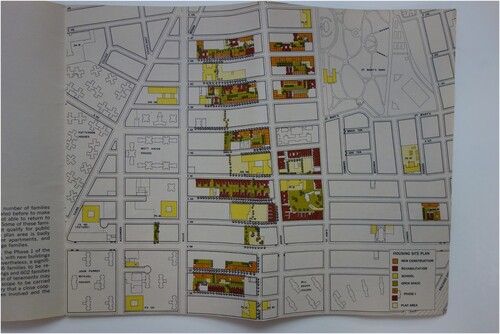

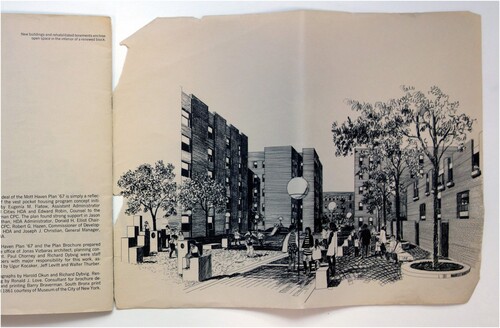

The 24-page, 9 by 12 inch brochure lets its author’s modernist sensibilities shine through. The minimalist white cover features just the lower-case, sans-serif words ‘mott haven plan/67.’ The interior alternates spreads dedicated to analytical maps and site selection coded in yellow, red, and brown earth tones (). Full-bleed black-and-white photographs include boys clamouring to be in the picture, grinning, laughing, pushing; a view, likely from an open window above, of men crowding around two tables set up for card playing on the sidewalk below; a frontal view of a large vacant site, the dark silhouette of the remaining buildings as backdrop for tiny human figures climbing over the piles of rubble. These images reveal a distinct interest in the human experience. Even if the community members’ voices are not discernible in this report, their presence is felt.

Figure 8. Jonas Vizbaras, Mott Haven Plan 67, plan of the study area showing new construction and rehabilitation as well as pedestrian connections between blocks. Source: NYC Municipal Library.

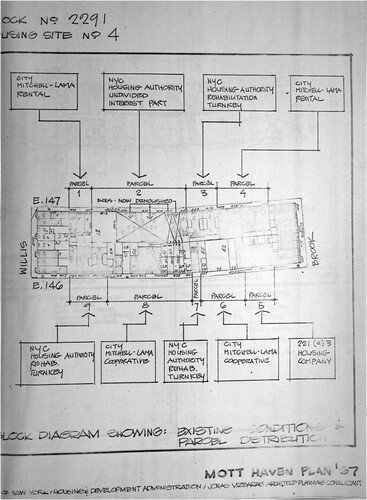

Vizbaras proposed the block – not the street, lot size, ownership structure, or building type – as the basic unit of analysis and operation. He numbered each of the eight blocks being considered for renewal; within in each block, he numbered the parcels (). The block was the scale at which to achieve a carefully orchestrated architectural mix of rehabilitated and newly constructed buildings. ‘Rehabilitated tenements’ meant combining adjacent buildings consisting of railroad apartments, to three larger apartments per floor. ‘New apartment buildings,’ with up to 50 apartments per building and up to six stories in height, would offer variously sized apartments. The block also provided a convenient measure of progress: once proposed Phase I and Phase II were enacted, an area could be considered renewed, the ‘Block Action Completed.’Footnote37 Vizbaras conceived of the block as a social unit; individual backyards would be grouped together to form a common open space. He imagined this space framed by new three- to five story brick structures, as well as old tenements, populated with people, play structures, and globe lights. () The courtyards would be connected by pedestrian-only paths, allowing children to walk traffic-free to and from school. Accordingly, site selection clustered in two main areas.

Figure 9. Jonas Vizbaras, plan showing the proposed mix of housing programmes in new and rehabilitated buildings on one block in Mott Haven, 1967. Source: NYHS.

Figure 10. Jonas Vizbaras, Mott Haven Plan 67, view of a courtyard created by combining adjacent properties on a block interior. Source: NYC Municipal Library.

What the ‘village’ was to a new town like Reston, then, the block was to be for old Mott Haven: neither focused on the street as argued by Jacobs, nor focused on the superblock as advanced by Wood or Mayer, but rather celebrating the idiosyncracies of existing buildings while moving beyond the constraints of individual parcels. In his pursuit of a carefully calibrated diversity, Vizbaras ignored Flatow’s admonishment to focus only on public and moderate-income housing only; for a second phase, he proposed a broader range of tenancies including cooperative homeownership through the Mitchell-Lama programme. As he envisioned it, ‘garden-style walk-ups’ and ‘two-family row houses will provide a variety of housing types and … offer a wider range of choices.’Footnote38 Vizbaras thus pushed the product of vest-pocket housing further than Raymond & May by explicitly proposing the alternate financial models Raymond had only alluded to. Paradoxically, although he was keenly aware of phasing and process, Vizbaras’s drawings showed a study area disconnected from the larger city, jobs, or employment, highlighting only housing and schools. Vizbaras’s conception of process, ultimately, was limited to getting the housing built.

Plan 3: Walter Thabit’s ‘development framework’ for East New York

Within the future Central Brooklyn Model Cities Neighborhood was East New York, a smaller vest-pocket study area for which Flatow engaged Walter Thabit. Like Raymond, Thabit was a known entity, but not an insider. Rather, he was an activist who supported residents who opposed city plans. Thabit was active in Planners for Equal Opportunity, had served in public office, and had consulted on the Metropolitan Council’s Report on Available Land.Footnote39 To Flatow, winning over Thabit for a city-sponsored planning effort bought credibility for the vest-pocket housing and Model Cities programmes.

East New York was developed later than Bedford-Stuyvesant, characterized by low-rise structures interspersed with high-rise public housing developments. The study area was markedly smaller than Bedford-Stuyvesant. Its main issue was rapid demographic change, increasing poverty, and a lack of continuity of civic organizations: the population had shifted from 85% Italian, Irish, and Jewish in 1960, to 80% Black and Puerto-Rican in 1967. Forty percent of households were on welfare, and the average family stayed in the area for only 16 months.Footnote40 The city had launched several initiatives – from code enforcement to multi-services – in previous years, but none seemed to be able to stabilise the area socially or physically.

Thabit thus had far less organized residents to work with than Raymond. And yet he considered the initial planning phase to be a success, describing it at length in his report, prepared with Walter Stoloff. To Thabit, the fact that a middle-aged, Jewish, female teacher and a young, African-American male activist – Leo Lillard, portrayed in Jeremy Wolin’s article in this issue – co-chaired the local committee spoke to the inclusiveness of the effort.Footnote41 What he heard from the residents was they were only marginally concerned with new housing. Instead, they demanded low-interest loans to allow current homeowners to renovate their homes, as well as adequate health care and education. The findings of the process thus challenged the core assumptions underwriting Flatow’s prompt, namely the nature of the product itself.

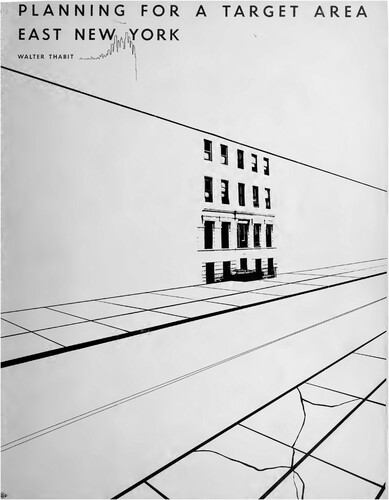

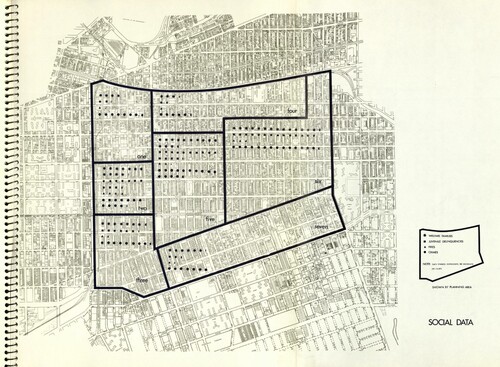

Not surprisingly, Thabit’s report spoke an entirely different language, and made very different recommendations than Raymond & May’s or Vizbaras’s.Footnote42 Printed in black and white on letter-size paper, half of the 122 pages were dedicated to survey data presented in single-spaced text, tables, or fold-out maps. The rest was pure text. There were no photographs of streetscapes or people, no renderings of an envisioned future. This was about socio-economic conditions as they played out on the ground. The maps, in relating, among other issues, the location of Welfare Families, Juvenile Delinquencies, Fires, and Crimes, are reminiscent of Charles Booth's poverty maps of late-nineteenth century London, even though Thabit’s goal was not to provide a justification for demolition, but the oppositeFootnote43 ().

Figure 11. Walter Thabit, Planning for a Target Area, East New York, 1967, plan showing social data. Source: NYHS.

Only half-way through the document did Thabit advance a proposal: a ‘Development Framework’ consisting of eight ‘action items.’ Only the first of these was a direct response to the brief he was given – siting units. His main goal was to promote a new form of ownership and stewardship of housing which he called ‘group management’ or ‘community management.’ In this way, ‘poorly operated properties are to be made livable’ and ‘[locally established] companies should be organized to train and use local labor.’Footnote44 The idea was a rebuke to both the public and non-profit sponsored rental model at the heart of the vest-pocket programme. In its place, Thabit advanced a vision of locally controlled cooperatives that would provide not only housing, but job training and employment. Thabit went further than Vizbaras in questioning Flatow’s prompt by proposing an open-ended process for a resident-controlled product.

Not surprisingly, the rest of Thabit’s action items were not about housing, but the strengthening of local employment, retail, and community facilities, adequate social, health, and educational services. Throughout, he called for the ‘maximization of local participation through successively greater grants of power,’ the gradual transfer of actual decision making and control of funds to the local level.Footnote45 To Thabit and residents, housing as a product was merely an excuse to lay out a process for the comprehensive social and economic renewal of their neighbourhood. As in all plans, however, there needed to be a response to the question of how to site the 1600 units. East New York’s response was the opposite of Bedford-Stuyvesant’s. Rather than protecting already strong assets from further decline, the committee deliberately placed the new buildings in the ‘worst part of East New York’ in order to make it more liveable for all.Footnote46

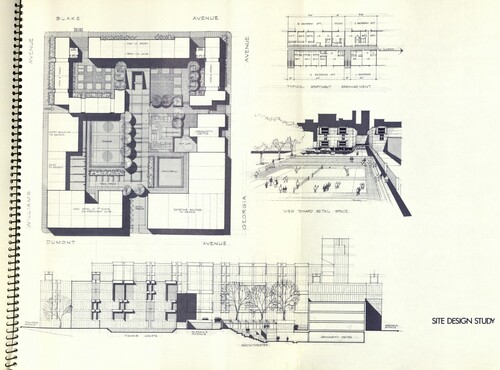

In the entire report, only two visualizations interrupt text, numbers, and maps. The first shows detailed architectural drawings, likely included to prove the feasibility of the proposal. A new superblock is created by closing a street. A multi-level amphitheatre and tennis courts animate a generous park, framed by three- to six-story residential buildings in brick and concrete (). The second visualisation – a vacant, ghostly image – is found on the report’s cover (). A perspectival line drawing outlines buildings and sidewalks on two sides of a street. A photograph of a single building’s facade, five windows wide, four stories high, is montaged into the otherwise empty street front. In the foreground, cracks indicate a damaged sidewalk. The point of this cover image may have been to signal the paradox of trying to save a devastated, underinvested neighbourhood through a smattering of new housing without changing the process of how housing is controlled. To this paradox, the single cover image spoke.

Plan 4: Barry Jackson’s ‘plan for a plan’ for Harlem–East Harlem

The firm Fisher/Jackson, selected for the vest-pocket housing study at Milbank Frawley Circle in Harlem-East Harlem, took a very different approach than their counterparts to both product and process. To engage the community and accelerate housing production, they embraced computation and industrialization. The practice was founded in Berkeley in 1964 by John Sergio Fisher and Barry Jackson. The partners maintained parallel offices there and in Manhattan, and divided projects accordingly.Footnote47

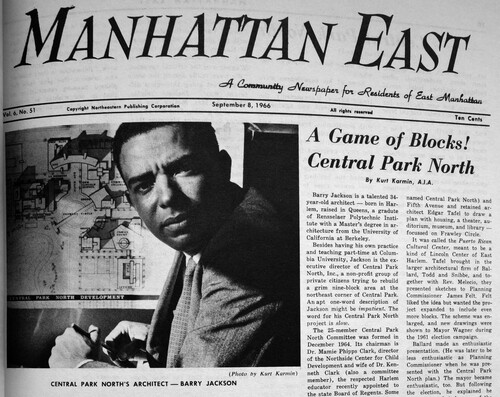

Jackson was the only Black architect engaged by Flatow, likely a strategic choice to navigate Harlem’s contested planning politics.Footnote48 Jackson was born in Harlem, but raised in Queens and was subsequently educated at Rensselaer and Berkeley. He had worked with John Louis Wilson, the Black lead architect of Harlem River Houses, and Edgar Tafel, a Frank Lloyd Wright disciple. Tafel’s recommendation led him to be appointed executive director of Central Park North, Inc., a non-profit organization trying to rebuild a nine-block area at the northeast corner of Central Park; later known as Milbank-Frawley Circle, this area became the centre of the vest-pocket housing study area.Footnote49 Nothing came of this earlier plan, but it put Jackson on the map (). In addition, Jackson taught computer-aided design at Columbia's School of Architecture and lectured and published widely.Footnote50 His avant-garde discourse and technology-driven entrepreneurialism set him apart.

Figure 14. Barry Jackson and his work on Milbank-Frawley Circle prior to the vest-pocket housing study, 1966. Source: NYHS.

Harlem, the centre of the city’s Black culture and political power, had been the testing ground for various large-scale planning efforts since the early twentieth century. These included interwar reform housing schemes as well as postwar high-rise developments.Footnote51 In January 1966, Harlem was once again pitched as testing ground; this time rehabilitation was intended to prevent further racial turmoil after the racial unrest in 1964.Footnote52 The study area, in contrast to these earlier renewal schemes, was limited in scope. The 40 blocks contained a mix of brownstones, old-law tenements, and new-law walk ups, of which the city considered more than 50% ‘dilapidated or structurally unsound.’ The area's 1960 population was estimated to be split halfway (and roughly along Fifth Avenue) between Puerto-Ricans and African-Americans.Footnote53

The best source for information about the vest-pocket planning process in Harlem is not a report Jackson submitted at the time – if there was one, it is lost – but the architect writing decades later.Footnote54 Jackson emphasized the residents’ fears of being displaced; upper Fifth Avenue was seen as choice real estate even then. He described the community’s deep distrust of the city, suspected of ‘always holding a ready-made, rolled-up plan downtown,’ and of which he was suspected to be an agent. Strategically, then, Jackson always attended the meetings of the Milbank-Frawley Housing Committee alone. He left his staff to work on the drawings in his downtown office and allowed committee members do the speaking, in attempt to act ‘purely as a technical adviser.’ Given the animosity between Puerto-Rican residents living east of Fifth Avenue, and the Black residents living west of it, Jackson attended separate meetings so that the groups would not have to mix. The process was more charged and harder to navigate than in the other study areas.

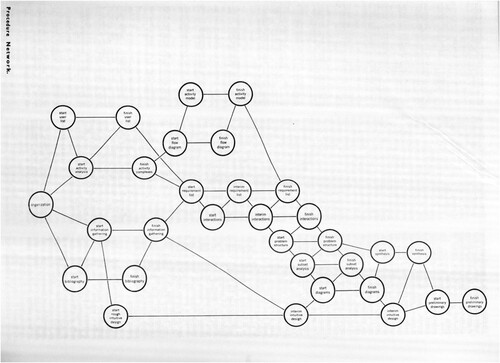

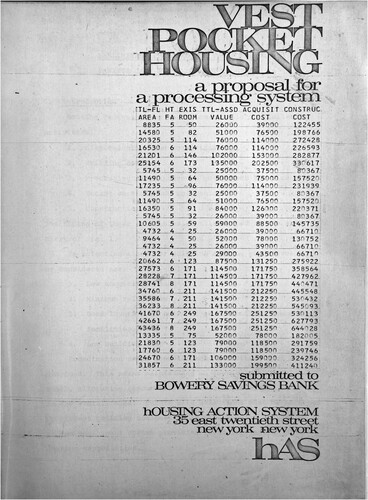

Nonetheless, Jackson spoke of the site selection as being self-evident.Footnote55 Sites were selected not with the intention of clustering for maximum effect, as in the other study areas, but according to the economic data generated by software he had developed. As described in a front-page article in the New York Times, a computer processed data of 1300 lots, taking into account their size, cost, number of existing rooms, and number of rooms allowable under zoning regulation, evaluating ‘about 1,240,000 possible site-building combinations for the ghetto area.’Footnote56 The goal was ‘to calculate the least expensive way of adding the required number of rooms and then judging the relative costs of different forms of construction.’ The president of Policy Management Systems, Inc., on whose hardware the programme ran, described the process as providing merely ‘economic facts’; the actual site selection for the product was to be made by humans according to ‘esthetic and humanitarian considerations.’ This was an extraordinary attempt to pair computational and people power, an effort motivated by a widespread belief in the mid-1960s that systems developed in the defense and aerospace industries could be adapted to address urban problems.Footnote57

In an article for the Italian design journal Zodiac, Jackson explained why he considered computers essential to serving communities. The ‘failure of the designer,’ he posited, resulted from the fact that even in light of ‘the complex array of forces which have impinged upon our environment,’ a designer still ‘fear(s) turning to new tools when the opportunity arises.’ Jackson elaborated:

The two broad areas in which the designer works are: (1) problem analysis and (2) solution synthesis. The key to any design process is feedback, which may be defined as the continually operating modification of the input of a design system by its output. Essentially, the process of design is continuous and it is only the fact that a physical embodiment of the design need emerge that interrupts the process.Footnote58

Figure 16. Barry Jackson, drawing of new vest-pocket housing for Harlem, published in People & Plans, 1967. Source: LaGuardia and Wagner Archives.

On the question of what a plan could and couldn’t accomplish and how this would fit into a necessarily political process, Jackson later wrote:

My preference was to develop a metaplan for Harlem; in other words, a plan for a plan. I was drawn to the idea of a computer model with variable resources as a method for being able to shift the resources as the project moved along. A Master Plan is obsolete the moment it is drawn and it is too easy a target for the opposition. Almost any line drawn on a map at a planning meeting draws opposition. The goal, in planning, is to finesse the opposition, using the old card playing strategies. These were rules everyone in the community knew and enjoyed.Footnote59

Jackson, more than any of the other consultants, stressed the political nature of planning. And yet one paradox of his ‘plan for a plan’ was that it did not, or could not, take into account the politics and related competing planning efforts underway in Harlem at the time. On the one hand, Jackson was being boycotted by a group of Puerto-Rican residents who felt unrepresented in the city’s process; working with Roger Katan, an architect affiliated with Pratt, the group produced a mega-structural counter-proposal.Footnote61 Jackson also did not account for a vest-pocket housing study being conducted by the Architects Renewal Committee of Harlem (ARCH), an organisation that prided itself on empowering Harlemites through architecture.Footnote62 It was not as if Jackson was not engaged on the ground. In fact, Fisher/Jackson was realising innovative adaptive reuse projects for emerging Black organisations. In a former supermarket, they built an open-plan school for the Harlem Preparatory School.Footnote63 In Brooklyn, they transformed a former milk bottling plan into the headquarters of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation.Footnote64 By early 1968, Jackson had turned the vest-pocket housing process itself into a marketable product called ‘hAS: housing Action System’Footnote65 (). And yet he could not overcome the deep political divisions on the ground; as a planner, he was a part of them. Given Harlem’s contested terrain, Jackson’s claim to be providing ‘just information’ was an attempt at rationalising an impossible task.

Conclusion: a summary report, June 1967

In April 1967, the consultants presented their recommendations for vest-pocket housing to the assembled decision makers of New York's planning and housing agencies.Footnote66 In June, the city approved the site selections and submitted its first application for a Model Cities planning grant to HUD; the programme had done its duty as a ‘head start.’ On July 12, the HDA presented its summary report to the public.Footnote67 Titled People & Plans, it described expected costs and benefits of the 14,500 units of housing to be generated: 8000 in the four Model Cities study areas and another 3000 in Twin Parks, exceeding the 1600 originally planned for each. An additional 3500 were to be built on scattered sites in more affluent areas. Together, this approximated the unit count of Co-op City, the large high-rise development being completed at the time in the northern Bronx, considered by many a vestige of the outdated planning philosophies the city was trying to leave behind.Footnote68 In a press conference, Lindsay engaged in superlatives to describe the new product, speaking of ‘the first giant step forward in New York's Model Cities programme – the largest package of new and rehabilitated housing ever assembled.’Footnote69 HDA Administrator Nathan primarily lauded the process: he described the programme as ‘embodying … community participation on an unprecedented scale’ which would lead to, among other benefits, ‘overall improved quality of neighborhood living,’ ‘jobs for residents,’ and ‘stimulation of investment of private capital in the ghetto.’Footnote70

The setting for these optimistic announcements could not have been more tense: 12 July 1967, marked the beginning of one of the largest and most destructive occurrences of urban unrest in the country in nearby Newark. Preceded and followed by unrest in other cities, the violence called into question the effectiveness of Johnson's Great Society. Despite the urgency, however, by late September 1967, the U.S. Congress had still not appropriated any of the $537 million approved for Model Cities by the Senate. This made Lindsay’s plea to increase the city's own contribution to the vest-pocket programme from $15 to $25 million a hard sell – especially since he was still using the term ‘head start’ to make the case. Ultimately, the City Council's finance committee approved his request. But committee members emphasized that they ‘were voting only for housing, not for model cities.’Footnote71 In other words, they were on board with the product, but remained highly sceptical of establishing a new planning process which promised to empower residents.

If and how the plans for vest-pocket housing were subsequently implemented varied greatly. Everywhere, the sites that residents had designated for housing construction were acquired by the city through eminent domain—their choices, articulated in the planning process, had real consequences. This came at a price of $25 million, or equal to the city’s capital appropriation to the programme, however, calling into question – as many residents had done – whether that money would have been better spent in other ways. In Central Brooklyn and the South Bronx, many projects were realized, albeit differently than originally proposed, both in terms of design and development models.Footnote72 In Harlem-East Harlem not a single project was implemented.Footnote73

Housing scholar Nicholas Bloom calls the lack of quantitative delivery resulting from the vest-pocket approach the ‘the price of design reform.’Footnote74 While a focus on the product is one way of evaluating the programme that Flatow had led, the diversity of proposals submitted by the planners she engaged and the resulting debates around the relationship of process and product suggest a different, a qualitative reading. First, by articulating the tension between product and process through specific architectural proposals, the consultants offered the city and its citizens ways to understand what they needed, even if this meant rejecting new housing. This is what Jackson and Thabit helped residents of Harlem and East New York articulate. Second, all four consultants emphasised that Model Cities’ goal to ‘turn around’ disinvested neighbourhoods would not come about through better-designed housing alone. Even Raymond & May, so focused on the benefits of a new housing type modelled on the old, and Vizbaras, convinced the physical unit of the block would create social cohesion, realised that their ideas would be for naught if there was not a simultaneous shift in funding sources and governance structures. Debating these issues through concrete proposals: this was the space of possibility Eugenia Flatow created with New York’s Model Cities vest-pocket housing programme. Fifty years later, such spaces of possibility are again sorely needed.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and to Christina Crawford for concise, last-minute editorial suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Susanne Schindler

Susanne Schindler is an architect and historian focused on the intersection of policy, finance, and design in housing. She holds a PhD from ETH Zurich, where she has been senior scientist and co-director of the Master of Advanced Studies programme in the History and Theory of Architecture since 2019. Schindler is co-author of the book Cooperative Conditions: A Primer on Architecture, Finance and Regulation in Zurich (forthcoming, with A. Kockelkorn and R. Hirschberg) and co-editor of The Art of Inequality: Architecture, Housing and Real Estate – A Provisional Report (2015, with R. Martin and J. Moore).

Notes

1 John V. Lindsay, letters to consultants, 30 November 1966, Flatow papers.

2 The fifth letter went to a group of architects preparing a study for the Twin Parks area in the Bronx which was not intended to be part of Model Cities; for this reason it is not included in this article. For more on Twin Parks, see Schindler, ‘“The institutions must be designed before the buildings”’.

3 ‘Text of President's Special Message to Congress on Improving Nation's Cities,’ New York Times, January 27, 1966, 20.

4 For an overview of the evolution of New York City’s housing policies amidst socio-economic change, see Bloom and Lasner, Affordable Housing in New York.

5 The November appointment letter repeats language of an Interdepartmental Memo from Flatow to Nathan sent on 22 September 1966, suggesting that she wrote the letter. Emphasis in the original. Flatow papers.

6 Accounts of the failed promises of Model Cities abound. With respect to the federal level, see Frieden and Kaplan, The Politics of Neglect; Haar, Between the Idea and the Reality. For New York City, see Thabit, How East New York Became A Ghetto.

7 This narrative underlies, among others, Bloom and Lasner, Affordable Housing in New York; Klemek, The Transatlantic Collapse of Urban Renewal; Zipp, Manhattan Projects.

8 Flatow never identified as a feminist or joined the National Organization of Women. In the words of her son, she ‘liked the company of men and the rough and tumble of politics. … Her thing was urban planning, not feminism.’ Evan Flatow, Zoom conversation with the author, 28 June 2022.

9 Silverman, “Housewife-Engineer is Clubhouse Oracle.”

10 Pamphlet, n.d. [1965], in Eugenia Flatow Papers MS 3175, NYHS Series V, Personal Files, 1940–2007; Offsite Box 39 (Political campaign 1963–65); Box 39, F1, Political (1 of 2), 1963–65.

11 After Lindsay replaced Flatow in 1970, she continued to work in housing and environmental justice in various non-profit, quasi-governmental, and governmental roles. She died in 2015.

12 The vest-pocket idea was simultaneously promoted as a strategy to create more parks and open space. See Mogilevich, The Invention of Public Space.

13 For the arguments in favour of neighbourhood-wide renewal, see Fairbanks, “From Better Dwellings to Better Neighborhoods.”

14 “‘Vest-Pocket’ Housing for City.”

15 “City Plans Housing in Small Projects.”

16 Quotes in Carlyle, “Excerpts from Panuch Report.”

17 See Hock, Political Designs.

18 Wood, The Balanced Neighborhood; Mayer, “Architecture as Total Community.”

19 Metropolitan Council on Housing, A Citizens' Survey of Available Land, 1.

20 Rubinow, “Survey of Housing Sites.”

21 For a later critique of the scattered site programme, see Bellush, “Housing: The Scattered Site Controversy.”

22 New York City Department of City Planning, Newsletter, September 1967, 3.

23 “Renewal Aide Named.”

24 O'Kane, “Aims of Planners Sharply Debated.”

25 O'Kane, “New Center Aids Area Replanning.”

26 Woodsworth chronicles this balancing act, including describing Raymond’s relationship with co-director Ronald Schiffman. See Woodsworth, Battle for Bed-Stuy, 203–7. Raymond was active in planning debates until his death in 2015 at 96.

27 Woodsworth, Battle for Bed-Stuy, 217.

28 This account is based on Raymond & May, Vest Pocket Housing in Bedford Stuyvesant.

29 Raymond & May, Vest Pocket Housing, 48.

30 Ibid.

31 Fried, “City Offers a ‘Model’ Plan for S.I. Area.”

32 Raymond & May, Vest Pocket Housing, 54.

33 Ibid., Cover Letter.

34 Ibid., 73.

35 Sources for Vizbaras' career are the 1970 The AIA Historical Directory of American Architects, Third Edition, 1970; and the author’s conversations with Herbert Mandel, September 2016; Bill Conklin, November 2016; and Andris Vizbaras, March 2017. Vizbaras died in 1977 at age 56.

36 Vizbaras, Mott Haven Plan/67, “Planning Background.”

37 Undated surveys by Jonas Vizbaras. Flatow papers.

38 Vizbaras, Mott Haven Plan/67, “New Apartments.”

39 For an in-depth portrait of Thabit see Reaven, Citizen Participation in City Planning. Thabit was active in planning debates until his death in 2005 at 84.

40 These descriptions are from the introduction to 1967 report, pages 1–3, but appear verbatim in Thabit, How East New York Became a Ghetto.

41 Thabit, How East New York Became a Ghetto, 101.

42 Thabit, Planning for a Target Area, 97.

43 Booth’s maps have been digitized and can be found at LSE, “Charles Booth’s London, Poverty maps and police notebooks,” https://booth.lse.ac.uk/.

44 Thabit, Planning for a Target Area, 65.

45 Ibid., 54.

46 Ibid., 7.

47 The main source for the oeuvre is a CV as part of a Fisher/Jackson office brochure, likely from 1968, which contains press articles and a project list. Flatow papers. Additional context was provided by John Sergio Fisher, telephone conversations with the author, 26 June, 5 July, and 10 July 2023 and a telephone conversation with Tony Schuman, 10 July 2023. Fisher had been Jackson’s instructor at UC Berkeley. The practice dissolved in 1973 for personal and professional reasons. In 1978, Jackson became a professor at NJIT. He died in 2018.

48 Jackson was featured in several accounts highlighting emerging Black architects. Huxtable, “The Black Man and His Architecture”; Haney, “Training of Blacks as Architects Progresses.”

49 Karmin, “A Game of Blocks.”

50 Jackson, “The Relationships between Needs are the Elements of Form”; Jackson, “System Building.”

51 Zipp, Manhattan Projects.

52 Bennett, “Mrs. Motley Acts to Bar Race Riots.”

53 Numbers and descriptions from Whitehouse, “Computer Helps to Plan Renewal.”

54 Jackson, “Model Cities Redux.” All quotes in this paragraph are from this article.

55 Jackson, telephone conversation with the author, 17 March 2017.

56 All quotes from Whitehouse, “Computer Helps to Plan Renewal.”

57 Light, From Warfare to Welfare.

58 Jackson, “The Relationships between Needs are the Elements of Form,” 212.

59 Jackson, “Model Cities Redux,” 380.

60 Jackson, telephone conversation with the author.

61 Katan, Pueblos por el Barrio; Perry, “Vox Populi”; Schindler, “Model Conflicts.”

62 Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem, Housing in Central Harlem. The story of ARCH is chronicled in Goldstein, The Roots of Urban Renaissance. According to Jackson, he was considered for a leadership position at ARCH, which was then given to Bailey, a white architect. As a result, he was not on good terms with ARCH. Jackson, telephone conversation with the author.

63 McGarry and Hix, “‘Learn, not Burn,’” For a history of Harlem Prep, see Goldenberg, Liberation, Learning, and Love.

64 Jackson/Fisher office brochure, Flatow papers. Woodsworth attributes the renovation to a Washington, DC-based firm, The Battle for Bed-Stuy, 298. Architectural Forum identifies the project as Fisher/Jackson’s in Bailey, “RFK’s Favorite Ghetto,” 48.

65 There are three distinct proposals for a hOUSING ACTION SYSTEM (hAS) in Flatow’s papers.

66 The Twin Parks planners were also included in this meeting. Interdepartmental Memo re: Meeting With Planners–Revised Schedule," from Flatow to Messrs. Hazen, Washington, Christian, Elliott, Robin, Ratensky, Kristof, Hardy, 11 April 1967. Flatow papers.

67 New York City, People and Plans.

68 Spertus and Schindler, “Co-op City and Twin Parks.”

69 Lindsay, press release, n.d., Municipal Archives, Box 51, Folder 937.

70 New York City, People and Plans, 2, 3.

71 Bennett, “Mayor's Slum Housing Program Gains.”

72 For projects implemented in Mott Haven, see Schindler, “Model Cities Redux.”

73 For the debates in Harlem, see Schindler, “Model Conflicts.” While construction did not move ahead in Harlem, Fisher/Jackson did realize a 100-unit scattered-site public housing development in modular wood construction in Oakland, California. It is featured in “Building with Boxes: A Progress Report,” 86-87; “Housing as Process”; and on the website of JSFA, Inc., https://jsfarchs.com/project/scattered-site-modular-townhouses/, accessed July 15, 2023.

74 Bloom, Public Housing that Worked, Chapter “The Price of Design Reform.”

Bibliography

- Archival Records

- City Planning Commission Files, Commissioner H. Goldstone, Municipal Archives of New York.

- Eugenia Flatow Papers, New York Historical Society (NYHS). [Note: Most sources cited in this paper were consulted prior to being catalogued at NYHS and therefore lack NYHS designations.]

- John Vliet Lindsay Subject Files, Municipal Archives of New York.

- Municipal Library of New York.

- New York City Housing Authority Collection, LaGuardia and Wagner Archives.

- New York Times (NYT).

- Published Works

- Architects’ Renewal Committee in Harlem. Housing in Central Harlem: part One, The Potential for Rehabilitation and New Vest Pocket Housing. New York, 1967.

- Bailey, James. “RFK’s Favorite Ghetto.” Architectural Forum, April 1968, 46–53.

- Bennett, Charles G. “Mrs. Motley Acts to Bar Race Riots.” NYT, January 11, 1966, 28.

- Bennett, Charles G. “Mayor's Slum Housing Programme Gains.” NYT, September 29, 1967, 41.

- Bellush, Jewel. “Housing: The Scattered Site Controversy.” In Race and Politics in New York City: Five Studies in Policy-Making, edited by Jewel Bellush and Stephen M. David, 98–127. New York: Praeger, 1971.

- Bloom, Nicholas Dagen. Public Housing That Worked: New York in the Twentieth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

- Bloom, Nicholas Dagen and Matthew Gordon Lasner, eds. Affordable Housing in New York: The People, Places, and Policies That Transformed a City. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- “Building with Boxes: A Progress Report,” Architectural Forum, April 1968, 84-90.

- Carlyle. “Excerpts from Panuch Report to Wagner on Need for New Housing Board.” NYT, March 10, 1960, 34.

- “City Plans Housing in Small Projects,” NYT, April 8, 1962, 81.

- Fairbanks, Robert B. “From Better Dwellings to Better Neighborhoods: The Rise and Fall of the First National Housing Movement.” In From Tenements to the Taylor Homes: In Search of an Urban Housing Policy in Twentieth-Century America, edited by John F. Bauman, Roger Biles, and Kristin Szylvian, 21–42. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000.

- Fried, Joseph P. “City Offers a ‘Model’ Plan for S.I. Area.” NYT, January 22, 1969, 19.

- Frieden, Bernard J., and Marshall Kaplan. The Politics of Neglect: Urban Aid from Model Cities to Revenue Sharing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1975.

- Goldenberg, Barry M. “Liberation, Learning, and Love: The Story of Harlem Preparatory School, 1967-1974.” PhD Dissertation, Columbia University, 2019.

- Goldstein, Brian D. The Roots of Urban Renaissance: Gentrification and the Struggle Over Harlem, Expanded Edition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023.

- Haar, Charles M. Between the Idea and the Reality: A Study in the Origin, Fate, and Legacy of the Model Cities Programme. Boston: Little, Brown, 1975.

- Haney, Lynn. “Training of Blacks as Architects Progresses.” NYT, March 15, 1970, 8.

- Hock, Jennifer. “Political Designs: Architecture and Urban Renewal in the Civil Rights Era, 1954-1973.” PhD Diss. Harvard University, 2012.

- “Housing as Process,” Architectural and Engineering News 10, August 1968, 18–33.

- Huxtable, Ada Louise. “The Black Man and His Architecture,” NYT, May 3, 1970, 121.

- Jackson, Barry. “Model Cities Redux: An Advocate Planner Reprises the Sixties,” Proceedings of the Fifth National Conference on American Planning History. Chicago, 1994, 377–389.

- Jackson, Barry. “System Building: Toward a Protosystem of Unit Generation,” in AIA Architect-Researcher's Conference, Proceedings, Fifth Annual Meeting, Edited by Philip M. Bennett, Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin, September 25–26, 1968, 72–96.

- Jackson, Barry. “The Legacy of the Harlem Model Cities Program,” in The Urban Experience: A People-Environment Perspective, edited by S. J. Neary et al., Proceedings of the 13th Conference of the International Association for People-Environment Studies, Manchester: Taylor & Francis, 1994, 223–238.

- Jackson, Barry. “The Relationships Between Needs are the Elements of Form,” Zodiac 17 (1967), 210–212.

- Karmin, Kurt. “A Game of Blocks: Central Park North.” Manhattan East, September 8, 1966, 10.

- Katan, Roger. Pueblos for El Barrio. New York, December 1967.

- Klemek, Christopher. The Transatlantic Collapse of Urban Renewal: Postwar Urbanism from New York to Berlin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

- Light, Jennifer S. From Warfare to Welfare: Defense Intellectuals and Urban Problems in Cold War America. Baltimore/London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

- McGarry, Marie, and Charles Hix. “‘Learn, not Burn,’” Home Furnishings Daily, March 18, 1968, 6–7.

- Mayer, Albert. “Architecture as Total Community: The Challenge Ahead. Part 2: Public Housing as Community.” Architectural Record, April 1964, 169–182.

- Metropolitan Council on Housing, A Citizens’ Survey of Available Land, New York, 1964.

- Mogilevich, Mariana. The Invention of Public Space: Designing for Inclusion in Lindsay’s New York. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

- New York City Housing and Development Administration, Community Development Program: Progress Report, 1968.

- New York City Housing and Development Administration, Jason R. Nathan, Administrator, People & Plans: Vest Pocket Housing. A First Step in New York’s Model Cities Program, New York, July 12, 1967.

- O'Kane, Lawrence. “Aims of Planners Sharply Debated.” NYT, March 6, 1966, 10.

- O'Kane, Lawrence. “New Center Aids Area Replanning.” NYT, July 31, 1966, 1, 9.

- Perry Berkeley, Ellen. “Vox Populi: Many Voices from A Single Community.” Architectural Forum, May 1968, 58–63.

- Raymond & May Associates. Vest Pocket Housing in Bedford Stuyvesant. A Summary Report to the Community and the City on Some of the First Steps in the New York Model Cities Program. New York: The City of New York, June 1968.

- Reaven, Marci. “Citizen Participation in City Planning: New York City, 1945–1975,” PhD Diss, NYU, 2009.

- Rubinow, Raymond S. “Survey of Housing Sites. Report on Potential ‘Vest Pocket’ Dwelling Areas Backed.” NYT, June 18, 1964, 34.

- Schindler, Susanne. “Model Cities Redux.” Urban Omnibus, October 2016.

- Schindler, Susanne. “Model Conflicts.” e-flux Architecture, July 2018.

- Schindler, Susanne. “‘The Institutions Must be Designed Before the Buildings,’” Perspecta 53: Onus (October 2020), 110–135.

- Silverman, Ira N. “Housewife-Engineer is Clubhouse Oracle.” The Morningsider, November 29, 1962.

- Spertus, Juliette and Susanne Schindler. “Co-op City and Twin Parks: Two 1970s Models of Middle-Class Living in the Bronx,” in Gaia Caramellino and Federico Zanfi, eds., Middle-Class Housing in Perspective. Bern: Peter Lang 2015, 167–190.

- Thabit, Walter. How East New York Became a Ghetto. New York: New York University Press, 2003.

- Thabit, Walter, and David Stoloff. Planning for the Target Area: East New York. New York, 1967.

- “‘Vest-Pocket’ Housing for City,” New York Herald Tribune, March 24, 1955, 24.

- Vizbaras, Jonas. Mott Haven Plan/67. New York, 1967.

- Whitehouse, Franklin. “Computer Helps to Plan Renewal.” NYT, May 7, 1967, 1, 10.

- Wood, Elizabeth. The Balanced Neighborhood. New York: Citizens’ Housing and Planning Council, December 1960.

- Woodsworth, Michael. Battle for Bed-Stuy: The Long War on Poverty in New York City. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Zipp, Samuel. Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.