ABSTRACT

This paper considers the urban consequences of failing to host Olympic Games. Using the example of Paris and its unsuccessful bids to hosts the Olympic Games of 1992, 2008 and 2012, the paper analyses the pre- and post-bid status of key projected ‘Olympic’ sites within the context of urban plans and aspirations of the city of Paris. The French capital attracts special attention because of the rapid succession of submissions that proved to be outbid by those presented to the IOC by the cities of Barcelona (1992), Beijing (2008) and London (2012). The paper will briefly outline the reasons for failing to attract the Games but will devote most of its space for an analysis of the siting of the planned Olympic Villages, which often form the most lasting of legacies of Olympic Games in host cities.

In the ongoing history of the Games, arguably no city holds as prominent a place as the city of Paris. It was in the city that the modern Games were reborn when in 1894 the first Olympic Congress inaugurated the Olympic Games of the modern era and awarded the right to host the first of these under the auspices of the International Olympic Committee (itself founded in 1894) to Athens, Greece. One of the key personalities involved in this Olympic revival, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, was born in Paris in 1863, and was instrumental in Paris becoming the second city to host the revived Games in 1900. The Summer Games returned to Paris in 1924 (and have since been immortalized in cultural memory as a result of the 1981 film Chariots of Fire) before a century would have to pass before the Games would return to the French capital. A century of privation and absence if not from France – the award of the 1992 Winter Olympics to Albertville would see to that – but from Paris nonetheless left deep psychological and, as we shall see, material alterations and a plethora of re-worked plans in the city. For it was not for want of trying to secure the Games that the city had to wait for a century before the global spectacle named after its ancient Greek place of origin would return. The city presented its candidacy to host Summer Games of 1992 in 1986, losing to Barcelona in the last round of voting. In 2001, it lost to Beijing for the right to host the Games of 2008 before suffering the same fate in 2005 to London, who would go on to host the 2012 Summer Games.Footnote1 Small wonder, then, that a recent doctoral thesis analysing these bids in the context of political and administrative decisions, refers to these years with reference to the Olympic symbol as ‘anneaux horribilis’ – horrible rings.Footnote2 The award, in 2017, to host the Games in 2024 therefore felt like justice delayed, even if the withdrawal of Budapest, Hamburg and Rome from the competition and the novel decision to award the subsequent 2028 Games to Los Angeles, the only remaining competitor for the 2024 Games, rendered the victory a foregone conclusion at the time; in the process Paris will have joined London and Los Angeles amongst cities who will have hosted the Games three times and will have evaded the fate of Istanbul’s five unsuccessful bids since 2000.Footnote3

Whatever about national pride and an increasingly irrelevant bidding process, the process that would result in failure more than once during the period 1986 to 2017 has arguably changed the urban morphology and the life in the city of Paris more than any success could have managed to achieve. If the much-discussed success of being a host city had changed the city of Barcelona – the first city to which Paris lost out during the period in question – it is to the botched bids that Paris arguably owes some of its current success as a city capable of attracting inwards investment, talent and tourist income.

In this, Paris is not alone. Nor is it the only city whose lack of success has attracted academic interest: Analyses of ‘failure’ in attempts to win the right to host Olympic Games have become the subject of a surprisingly rich tapestry of publications over the course of last decade since the publication of Masterman’s inaugural paper,Footnote4 Torres’ unpublished paperFootnote5 and my own modest inroads into this topic.Footnote6 Oliver and Lauermann’s 2017 book,Footnote7 alongside the longue durée engagements of John and Margaret GoldFootnote8 on the topic must count as a singular achievement in this context, with its attention to policy and rescaling. John Lauermann in particular has contributed substantially to our understanding of the interplay between ‘success’ and ‘failure’ in the context of Olympic bids. In much of his work, he rightly questions the idea of linear times being at work in the delivery of urban futures.Footnote9 Instead, temporary visions, however short-lived (as for instance successfully delivered but temporally bounded cultural eventsFootnote10), or un-successful they may be can leverage even failure to ‘to construct long-term development agendas’.Footnote11 Here, Lauermann contends, ‘the definition of the durable evolves through iterations of the temporary’.Footnote12 Such plans often form part of a competitive agenda driven by neo-liberal urban development, with its often-noted investment in ‘creative’ and highly visual, indeed glossy urban configurations at the expense of social or public housing or the delivery of basic amenities. As this literature contends, a considerable overlap furthermore exists between successful and un-successful bids in that both deploy the bid process to present and familiarize a wider public with ambitions emanating from city halls involved in such processes. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the context of transportation infrastructure, which can be presented as a necessary requirement for successfully delivered Games while offering alluring post-Game urban futures, functionalities and legacies.

Not surprisingly, given the IOC’s own shift towards sustainable urban engagements as part of the bidding and evaluation process, a lot of these engagements centre around notions of ‘heritage,’ ‘legacy’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘future-making’. The IOC itself deploys the nomenclature of ‘legacy and impact’ in its adjudicating literature. Often criticized for delivering the Games at the cost of creating ‘white elephants’ that do not contribute toward sustained urban development, the IOC changed the criteria according to which Games were awarded following the disappointing legacy of the Games in Athens in 2004, which were awarded in 1997. Discounting the following, politically motivated Beijing Games, the London Games of 2012 with their overt embrace of using the legacy of the Games to bring about urban regeneration in London’s neglected Eastern burroughs arguably inaugurated a new set of pages in the annals of Olympic history. In fact, the IOC itself extended the issue of legacy explicitly to include the legacy of ‘unsuccessful’ bidding processes in their ‘Candidate Acceptance Procedure’ for the 2020 Olympic Games.Footnote13 Not that ‘urban planning’ and ‘regeneration’ were absent from all previous bids – Munich 1972 redesigned an old, post-war Schuttberg or rubble mountain in the city’s Northern perimeter to create a new urban landscape that still astonished while Rome in 1960 was arguably the first city to design an Olympic Village and an ‘urban quarter’Footnote14 – but it now became de rigeur to include demonstrable strategies for post-Games urban legacies in every bid to host Olympic Games. In addition to questions attaching to the legacy of the Games, their environmental impact increasingly became a criterion against which to evaluate bids.

The various submissions to the IOC emanating from the city of Paris, the subject matter of this paper, arguably reflect this shift well enough. Somewhat ironically given that the two cities would compete in 2005, the city’s 1986 ill-fated submission arguably invented the rule book deployed successfully by the city of London in that year: as a pivot towards traditionally neglected urban neighbourhoods and areas in each of the city’s Eastern parts. The inclusion of existing infrastructures furthermore became a central fulcrum in those bids. The 2008 and 2012 submissions in particular benefitted from the existence, since the 1998 Football World Cup, of the State de France: a 80,000+ seating stadium in Paris’ Northern suburbs. Its inclusion in all subsequent plans allowed for the city of Paris to anchor the bids that succeeded the 1986 loss to Barcelona in cost-efficient and sustainable solutions; nonetheless, two more engagements had to fail at the hurdle of an intractable voting process before Paris was invited to translate plans into reality. In what follows, this paper will outline the geographical embedding of the bidding process within ongoing urban transformations before turning its attention to the three plans that failed to gather a sufficient number of votes in the period in question. The concluding parts will briefly outline the move towards a bid that succeeded in securing the 2024 Games before speculating about the spatial conditions of possibility underlying the bidding process more generally.

Finding space for the games: the Parisian context

Bidding for and sometimes hosting Olympic Games pivots around the availability of space to allocate sporting infrastructures and an ‘Olympic Park’ into which an Olympic Village that provides a home for thousands of athletes for the duration of the Games can be inserted.Footnote15 The latter configuration holds special pride of place for the IOC given that the Olympic idea revolves around notions of non-professionalism, friendship, peace and youth. For this to translate into concrete practice, athletes (and functionaries) need to be provided with non-competitive spaces of encounter – the notion of a ‘Park’ fits that bill.

But it does so only in a not-too obviously compromised manner if a spatial configuration can be found or constructed – the difference will be discussed in the conclusion to this paper – that is contiguous and sizeable enough. And while this necessity poses problems in most cities capable of hosting events like the Olympic Games, it was always destined to present additional problems in Paris, a city known for its compact shape and relatively small urban footprint. This latter was limited by the political geography of Paris, a stable spatial entity since its establishment during the nineteenth century Second Empire. The creation, in 1860, of the well-known ‘spiral’ of 20 arrondissements and 80 Quartiers was contained within a defensive structure, the ‘Enceinte de Thiers’ (named after the French Prime Minister who advanced its construction between 1841 and 1846). The Thiers Wall was gradually dismantled during the 1920s and replaced with, on its Parisian side, with a series of social housing projects while the outer part, known as the ‘zone’ and occupied by migrant populations and rag-pickers, was to become a ring road in the post-war period. Completed in 1973, the Boulevard Périphérique effectively sealed the fate of Paris as a political entity: within its 35km circumference – often still referred to as the Paris intra muros (‘within walls’) – was the Paris of lights, history and magnificence while outside was the banlieu, an everyday Paris that lacked glamour and was the preserve of the petit bourgeoisie and large housing estates alongside expansive economic spaces housing logistics, garages and small-scale entrepreneurial activities.

This mattered in the context of the Olympic Games because the allure of Paris as a bidding city was considerably tied to its intra muros standing within and towards a global audience. But space within that configuration was difficult to realize post 1945 and became increasingly impossible to attain because of urban renewal projects that preceded or accompanied the bidding process. The dismantling of the central ‘Halles’ district during the early part of the 1970s was always destined to remain a space dedicated to commerce and, below ground, mobility-enhancing infrastructures. Space nominally vacated by the abandonment of the two municipal abattoirs during the 1970s was reactivated in the form of two urban parks in a city largely devoid of ‘green’ spaces: the Parc Georges Brassens (opened in 1985) in the 15th Arrondissement and the Parc de la Villette (opened in 1987) in the 19th Arrondissement. Of these, only the latter could conceivably have offered a surface sufficient to install an Olympic Park. Similarly, the 24 hectares vacated by the 1975 relocation of Citroën’s remaining automobile production facility at the confluence of the Périphérique and the Seine in the 15th Arrondissement offered not enough space to suit Olympic ambitions and became the Parc André Citroën instead (it opened in 1992). Congruent with the above ‘infill’ of the city of Paris went a transition characterizing the planning instruments available to urban planners. If the 1965 Schéma directeur d’aménagement et d’urbanisme de la region de Paris had set the tone towards the creation of a thoroughly modern Paris, complete with surrounding ‘villes nouvelles’ (Welch 2018), it was the transition from using larger scale ‘priority urbanization zones’ (‘zone à urbaniser enprioriaire’ or ZUP, these existed between 1958 and 1993) towards smaller-scale and considerably more flexible ‘concerted development zones’ (‘zones d’aménagement concerté or ZAC, these were created in 1967 and continue to exist) that mirrored the difficulties analysed in this paper.

If thus categorically vacant spaces – spaces no longer embedded within a clearly articulated economic or social logic – could no longer be used to anchor a bid for any of the Games since the 1980s, spaces needed to be identified that could reasonably be anticipated to offer the required opportunities. It is to these ‘negotiated’ spaces that we will now turn our attention.Footnote16

1986–1992: Reconfiguring the East: Bercy and Tolbiac

Of the three bids that failed to secure the Games, it was arguably the first that felt most directly like a lost opportunity. After all, it would have been 68 years after Paris had last hosted Olympic events and those early Games paled in terms of size and mediated importance with what they had become. In addition, the candidature was based on a celebration of the 100 years that had eloped since de Coubertin had first floated the idea of a re-birth of the ancient Games in modern times in a talk he gave at the Sorbonne in 1892.Footnote17 After the decision in favour of Barcelona had been announced, it was – of course! – the machinations of Juan Antonio Samaranch y Torelló, the reigning President of the IOC at the time and a proud Barcelonan, who secured the Games for the Catalan capital. Equally important, however, was the award to the Winter Games to French region and city – Savoie and Albertville – which preceded the voting on the summer Games at the 91st session of the IOC in Lausanne in 1986. Although not technically ruled out by IOC statues, it was not since the ill-fated 1936 Olympic Games that both the summer and the winter events – their temporal separation was to be decided at the same session in 1986 – had been held in one country. At the time, the bidding process was still deeply embedded in lobbying attempts and official site visits to Olympic candidature cities by nominated members of the IOC were common practice – a practice soon to be outlawed. Paris’ mayor at the time, the later President of France Jacques Chirac, actively encouraged such practices indicating the need to pick up foreign IOC members and their families, even on repeat visits, by helicopter from the airport.Footnote18 The IOC subsequently changed the rules and entrusted the ‘fact finding’ part of the bidding process to an evaluation commission. Its members would, from hence, visit all candidature cities together and produce a joint report to the IOC general session.

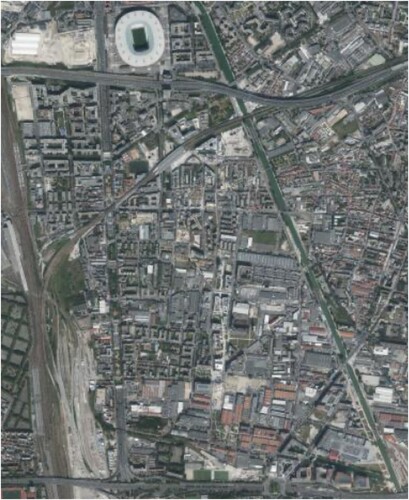

The bid itself was partially based on the perceived success of the Grands Projets that accompanied the Mitterand presidency in Paris, reconciling, in the words of Gérard Garoff, a sports functionary seconded to support the bid in the Mairie de Paris, ‘cultural heritage and modernity’.Footnote19 More importantly, it was consciously designed as an instrument of urban recalibration from the moment of its first inception in 1983.Footnote20 The Eastern part of the city, every local planner agreed, had largely been neglected by decades of urban interventions and required infrastructural investment. What is more, an existing set of material arrangements in Tolbiac (railway and milling infrastructures) and in Bercy (wine storing and decanting activities) was widely regarded as having outlived its welcome in situ.Footnote21 Luckily, urban restructuring and the previous decision to allocate a multi-sports arena, the Palais Omnisport de Paris-Bercy (today’s Accor Arena; the building opened in 1984)Footnote22 towards the North-Western edge of the area afforded those designing the bid with opportunities in the East around Bercy and Tolbiac, on the left and right bank of the Seine where it entered the city of Paris proper (see ). The nature of these ‘opportunities’ bears repeatingFootnote23 because its strategic engagement with an essential requirement for the bidding process was decided before and during the candidacy phase in a manner that would set the tone for future bids. This concerns the identification and presentation of space that was available for the construction of Olympic sites, most prominently including the Olympic Village but also the construction of an Olympic pool and a new stadium in 1984.Footnote24 The identification of urban space for larger-scale development purposes is a complex undertaking in any context. Competing visions, different forms of capital, contextual planning rules and regulations, including zoning attributions, political ambitions and local forms of resistance all add up to form a knotty overlay of opportunities and restrictions. But whatever may emerge in a particular site, that site has to be conceptualized as a possible site, ideally: as a site awaiting – and thus benefitting from – some kind of development. For this to make sense, for some space to enter into the realm of possible development, it has to appear to be vacant. We will consider the implications of this condition of possible development in the concluding section of this paper. Here and now, suffice it to point towards the declaration of the French organizing committee towards the need for urban interventions on both sides of the Seine as a rationale for the siting of Olympic structure there. In hindsight, it is therefore easy to pronounce the plans submitted for the 1992 Games as a ‘precursor project for the future ZAC Paris-Rive Gauche’Footnote25 established in 1990. Equally noteworthy is the fact that the urban engagement for the Games in Bercy and Tolbiac built itself on plans to use the area to stage a World’s Fair in 1989 to commemorate 200 years of the French Revolution (and thus, however implicitly, 100 years of the construction of the Eiffel Tower) underneath the grandiose banner of ‘The Paths of Liberty: A Project for the Third Millennium’. These plans were abandoned in 1983 following an extended power play between the then French President François Mitterand and the Mayor of Paris, Jacques ChiracFootnote26 – but left a legacy of abandoned plans that nonetheless were subsequently reworked into fresh proposals.

As we know all too well, the placement of the Olympic pool in Tolbiac and the main part of the Olympic Village in Bercy was not to come. The site of the Olympic pool is nowadays occupied by the National Library, the Bibliothèque Francois Mitterand, whose design replaced the depths of a pool with a sunken forest.Footnote27 As for Bercy, its past as an entry point for wine entering the French capital has provided endless opportunities effectively to riff on its bygone days in a series of commemorative choices within the new Parc de Bercy and its adjoining spaces. An interesting note to the never-to-be history of Olympic Games at Bercy and Tolbiac is the fact that the emplacement of these two key sites was initially reverse but changed at the suggestion Camille Cabana, who referred to the original emplacement as a ‘massacre’ due to the presence of a large number of old trees that would have to be sacrified. Chirac’s handwritten comment on Cabana’s note simply states ‘impossible’. At the same, the alternative placing of an Olympic-sized pool at Tolbiac equally appeared to be far from ideal in Cabana’s eyes – it will be ‘comme un cheveu sur la soupe’.Footnote28 No surprise, therefore, that in the immediate aftermath of the decision in favour of Barcelona, the idea of placing aquatic infrastructures at Tolbiac was dropped despite the stated need for within Paris in the official candidature document.Footnote29

2001–2008: A changed northern urban frontier

The bid for the 2008 Summer Games shifted the focus from the well-known Paris made up of Haussmann’s 20 Arrondissements as the primary location for sportive activities towards the ‘the north-eastern zone which is presently a relatively run-down housing and industrial area’.Footnote30 It was here, in close proximity of the Stade de France, that the Olympic Village was to be constructed and serviced by a new tramway in addition to existing rail and subway lines. Crucially, the plans for the Olympic Village were presented as part of an existing Master Plan for the area in question, effectively subsuming the Games within the continuous process of regional urban ambitions, a practice that was noted by the IOC in its evaluator report: ‘There is,’ it noted, ‘a challenge in producing and operating an Olympic Village as part of an urban redevelopment in a City centre Games’.Footnote31 As such, the bid altered the earlier submission centred in Paris’ East from inner-city redevelopment to the creation of the image of a ‘post-industrial Paris’.Footnote32 ‘Dépolluer’ or depollute, cleaning up, was a key catchword in the bidding process.Footnote33

The siting of the proposed Olympic Park articulated the attempt to eliminate a key part of the rupturing of the relationship between Paris and its northerly neighbouring communes, while also maximizing a potential proximity to the Stade de FranceFootnote34 it was for these reasons that an early suggestion of the Batignolles site, although applauded for its spaciousness, was not pursued any further in the early parts of the new millennium. The Olympic Village itself, the candidature material proudly proclaimed would create ‘a vast garden city’ filled with low-density housing, ‘designed for athletes and intended for the future’.Footnote35 Crucially, the future anticipated by the document included 2 new university complexes, along with student housing and office space.

Anyone visiting the area that was to become the Olympic Village for the 2008 Games today will encounter a space that is largely unrecognizable from its previous material and economic state when the Olympic ambitions were formulated but fully congruent with the ambitions that informed the bid. Extending from the Péripherique towards the State de France is a set of institutional and commercial buildings, some old and repurposed, some new, furnishing sites for educational, media-related and housing purposes. The frontier between this state-led urban regeneration and, frankly, urban extension will soon be marked by the RER B line to the North, the Canal Saint-Denis to the East and the A1 motorway towards the West – especially when the planned-for redevelopment of the Périphérique to undo its monstrous impact in favour of more permeable access towards Aubervilliers will be executed (see ). These spaces are organized around the Front Populaire Métro stop, part of an extension of the 12 line towards the northern suburbs of the French capital that opened in 2012 and extended, by 2022, towards Marie d’Aubervilliers, a future stop on the new, circumnavigational Métro line 15 scheduled to be completed by 2030. Fittingly, the organizational headquarters for the 2024 Games are presently located towards the southern end of the square that gave the Métro station its name.

It has to be noted, however, that the 2008 bid was ambiguous and tentative. The summary engagement with the plans presented by Paris’ Urbanism Agency APURFootnote36, while weighing different options for embedding the Games within the urban fabric of Paris and environs, deploys the notion of a ‘trial run’ for the 2012 candidature repeatedly; the invocation of ‘Batignolles’ as a possible site for the Games also features prominently in the report in the form of a ‘Case B’ scenario for the placement of the Olympic Village in the event of ‘technical difficulties’ rendering the Plaine-Saint-Denis an impossibility.Footnote37

2005–2012: Transforming the North-West: Batignolles

In hindsight, the third unsuccessful submission to the IOC shares with its two predecessors an unambiguous embedding within urban development plans, this time aiming to use the construction of the Olympic Village to transform a 50-ha site in the North-Western 17th arrondissement blighted by increasingly redundant railway infrastructures and a generally neglected feel once a casual visitor had left the old parts of Batignolles. If the Village was to provide the anchor, the main activities were designed to take place in two clusters, both built around existing sporting infrastructures in ‘sites located at the Gates of Paris’Footnote38: a Western Cluster around the Parc de Princes and the Roland Garros tennis infrastructures in the 16th arrondissement, including space in the adjoining Bois de Boulogne, while a Northern cluster continued the ethos of the previous bid by being centred in the Plaine de Saint Denis, between the Périphérique and the Stade de France. Supported this time by President Jacques Chirac, the bid document was heavily indebted to the language of cost-controlling measures and sustainability, emphasizing the re-use and further development of existing infrastructures and the post-Games legacy of the new urban quarter that was to emerge through the construction of the Olympic Village. Then, as well as retrospectively, the fact that until the last moment Paris was deemed to be the odds-on favourite to win the right to host the Games in 2012 does not surprise.Footnote39 In its submitted form, the bid clearly presages a lot of the ideas that came to structure the IOC’s reactive ‘Agenda 2020’, with its overt encouragement of the use of existing material structures in the bidding process.Footnote40

Here, then, the parallels to the 1986 bid are obvious: like Tolbiac before, Batignolles formed a largely neglected, peripheral part of the Parisian morphology, even if the Western part of Paris in general could not lay claim to having been side-lined by urban development. A closer look at this part of Paris, however, reveals that since its incorporation in 1860, the hosting 17th had always been a rather strange mélange of Haute Bourgeoisie urban morphologies in the West and considerably more modest working-call, immigrant housing stock in the North. Firmly separating these two was the deep cut of the railway line linking the Saint-Lazare railway station with its Hinterland towards Rouen, Le Havre and beyond. The separation was arguably augmented by the existence of logistic and warehousing infrastructures to the West of the rue Cardinet: on its Eastern side and well connected with the centre of Paris was Batignolles, a bohemian outpost of the adjoining affluent 8th arrondissement, an area that came to a sudden halt there. If on the Eastern side of the street was the old ‘sanctuary of the petit-bourgeoisie’, erstwhile a refuge for Belle Époche dropoutsFootnote41, crossing the rue Cardinet entailed encountering a terrain not entirely dissimilar to Tolbiac some twenty years earlier: old and somewhat neglected railway infrastructures abounded and framed the site while also filling it with activities (see ). In 2004, the city of Paris and the French Olympic Committee erected a viewing platform on the site – not to view the admittedly dreary site itself but to establish visual relations towards other sites that were part of the bid and towards Paris ‘proper’. The site itself featured prominently in the 2006 Plan Local d’Urbanisme (PLU), a newly developed holistic planning instrument, in the form of a future ‘green quartier’ extending beyond the separating line of the old Ceinture ring railwayFootnote42 towards the storerooms of the Opéra Comique and the ‘Berthier’ performance space of the Odéon Theatre.

But London won the Games with a not altogether dissimilar bid, mentioning the Games as a ‘catalyst for the redevelopment’ of parts of London forcefully in its official candidature submission. The part of Paris that lost out ultimately benefitted for the abandoned plans for the 2012 Games yielded just what the Games had promised: a thriving set of high- and medium-rise apartment blocks surrounding the newly created Parc Clichy-Batignolles Martin Luther King. In typical French fashion, a new anchor was positioned towards the Western edge of the area in what was once the ‘zone’ just beyond Thiers’ fortification (still materially present here in the form of an ancient bastion) in the newly built Tribunal Judiciaire de Paris, a 28-storey, 160m high courthouse designed by Renzo Piano visible from many parts of Paris.

Post 2012

The three bids to host the Summer Games failed for a variety of reasons, not all of them related to the quality of the submissions. Geopolitics, hitting the nerve of the time with a presentation, or the unfair pitching of stiff politicians against a multi-ethnic children’s choir were all in play in denying Paris the desired Games. The net result, as we have seen, in a densely populated city with no space to spare was a series of forced decisions that ultimately benefitted the city more than hosting the Games could have probably achieved. Of course, such an assessment is speculative, but the results, as we have seen, largely speak for themselves.

In keeping with the logic developed in this paper, it is no surprise to see the largely nominal but successful bid to host the Games of 2024 scale up the approach adopted towards the location especially of the Olympic Village. In 2006 President Nicolas Sarkozy had launched an initiative to create a larger metropolitan council for Paris. The idea was initially to bolster plans for extending the public transportation network in and around the French capital as well as providing a vision to address the causes of the 2005 urban riots in Paris. The Métropole du Grand Paris was finally established in 2016 with a decidedly regional ethos.Footnote43 Small wonder, given the successful translation of previous unsuccessful bids into flourishing new urban quarters, the 2024 documents extend that logic towards the banlieu. Intra muros, within the area of the old fortifications that had existed between the 1840s and 1920s, it had become impossible to find space for the installation of large-scale venues or an Olympic Village. The decision was taken to position the 2024 Olympic Village in Saint-Denis overlooking the Seine and adjacent to the Cité du Cinéma which had been established in a redundant power plant in 2012. This was congruent with an ethos that sought to recalibrate the relationship between a wealthy urban core and a largely neglected banlieu that made its presence felt through periodic eruptions of violent unrest. In this location, the Athlete’s Village could be in walking distance of the Stade de France and the newly emerging Aquatic Centre were it not for an impossibly dense network of different traffic modes and intersections.Footnote44 The Aquatic Centre is a case in point emphasizing the continuity of urban ambitions across bids: promised by Chirac as a key ‘deliverable’ for Saint-Denis as part of the 2012 Games, it became ‘a signature legacy project that affirms goals of Agenda 2020 while satisfying a currently unfulfilled and regionally significant deliverable’.Footnote45

Conclusion

The use of the word ‘failure’ to the title of this paper is an obvious provocation. Those critical of the Games, their impact on host cities, their increasingly obvious genuflection on the altars of commercialization or of their pretended distance from world politics would instantly claim that not becoming a host city should be cherished, rather than lamented.Footnote46 But the fact remains that until fairly recently, a stiff form of competition surrounded the bidding process and successful cities celebrated victory quite publicly. Perhaps such is the nature of competitions – and in this context, becoming say a European Capital of Culture is no different from winning the right to be a host city for Olympic Games.Footnote47 But marketing apart, cities can profit from the process of presenting themselves ready to host the Games or any large-scale festival or event.Footnote48 As this paper argued, the sheer effort that goes into identifying sites, finding a vision, developing infrastructures, convincing adjoining communities, realizing and allocating capital is bound to yield results. And while Paris does provide a special lens through which to approach this issue, it is by no means unique. Even abandoned bids like the one to host the 2024 Games developed in the early to mid 2010s by the city of Hamburg yielded an entire new mixed-use neighbourhood near the city centre alongside a series of surprisingly vocal forms of civic engagement.Footnote49

If ‘failure’ is thus a misnomer, the research around non-successful or even abandoned bids points into another, potentially fruitful area of creative and critical engagement that analyses the relationship between ‘present’ and ‘absent’ urban infrastructures. As this paper has argued throughout, it is the designation of sites especially for an Olympic Village that is of primary importance in this regard by virtue of its relatively extensive demand for space. If earlier Games could afford to embed their choice of sites within a quasi-colonial context of ‘military servitude, the situation has changed to the programming of location strategies even affecting changes in use and new urban functions’.Footnote50 Today, no city anywhere has such space available if it is conceptualized as ‘empty’ space – other than towards a current, often remote, urban-rural fringe. Such sites are of no interest in the context of Olympic Games given that they would, in the event of Games being based on their realization, present considerable logistical problems. Within the urban footprint, ‘vacancy’ does not exist, least of all in the form of areas ready to be turned into Olympic Villages. What does exist are spaces conceived of or designated as ‘empty’ as a result of economic transformations and subsequent political decisions. The plans submitted for the 1992 Games are indicative in this regard. On both sides of the Seine, as I have argued in an earlier paperFootnote51 ‘vacancy’ was construed with reference not to buildings but functions. In particular the Bercy part of the area in the 12th Arrondissement north of the Seine was in the process of economic transformation: the function of the ‘Entrepôts de Bercy’ as a point of contact for the delivery of wine into the city (primarily from Burgundy), which dated back to the early eighteenth century when the area was firmly outside the boundary of Paris, had become obsolete because of technological change, economies of scale and changes to the structure of the viticultural retail and wholesale sector. The resulting creation of an opportunity justified the decisions that informed both the bid and its aftermath. Such ‘creations’ are always fabricated and are often realized despite – and occasionally against – the continued existence of material and social structures and cultural memories. The material structures – or parts thereof – and remnants of cultural memories often survive in commercialized form – as exemplified by the Bercy Village shopping mall that refurbished the sole remaining and suitably protected remnants of the ancient ‘Entrepôts’ of Bercy in the late 1990s, inclusive of railway tracks and alleyways. As for a previously existing social fabric, not being incorporable into the urban capitalist economy often leads to its disappearance.

Instructive in this context is a statement by Léo Fauconnet, at the time Head of Governance at the Institut Paris Région, about the ambitions informing the placement of the Olympic Village and Park for the 2012 Games: ‘We were looking for 150 hectares. We knew very well that we did not have 150 hectares in Paris’.Footnote52 This ‘having’ – the availability of (an adequate amount of) space – is an obvious determinant in any hosting of mega-events; what’s less apparent is how space or spaces are made to be available. This paper has argued that ‘availability’ emerges through protracted, multi-layered processes involving negotiations and the repeated, indeed layered envisioning of urban futures. These latter especially work with and through declarations of vacancy as much as through actual, visible vacancies. Placing an Olympic Park demands extraordinary creativity – and no less municipal power – to see vacancies and imagine opportunities for and beyond the hosting of the Games. The fact that ‘[t]he IOC encourages cities to submit bids that develop legacy goals that align with broader urban development objectives’Footnote53 invites speculation to what extent the Parisian bids from 1986 onwards were primarily designed around longer lasting urban ambitions to which the bidding engagement added a veneer of visibility, prestige and urgency.Footnote54 Interwoven into such envisionings are questions of site ownership: the site in Tolbiac, for instance, that was so centrally involved in the bid for the 1992 Games, provided an opportunity for the city of Paris to wrestle space from the SNCF, an objective that required the candidature process for it to succeed.Footnote55 Equally important are relative engagements with space, referring to existing uses as ‘under-utilised’ and in the process rendering any such space ‘coveted’.Footnote56 In the process, the declaration of effective, if not actual vacancy gained remedial urgency through the demonstration of possible futures, the rhetoric and visual mastery of which makes any pre-existing urban materiality pale by comparison: these latter suddenly seem out of place despite having shaped local practices for a considerable amount of time. Some of this process is simply a recognition of economic change, much like the relocation of the previously mentioned old ‘Halles’ district in the centre of Paris (Émile Zola famously referred to it as the ‘belly of Paris’ in his 1873 novel Le Ventre de Paris) towards Rungis in the Southern suburbs of Paris. This owed its motivating logic to technological and economic change – chief amongst which we must count the invention of and subsequent uptake in refrigerated trucks. The Olympic process thus inserts an element of urgency and desirability into what would otherwise be a considerably less necessary – and therefore contested – process of spatial redesignations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ulf Strohmayer

Ulf Strohmayer teaches geography at the University of Galway in the West of Ireland, where he is currently a professor in the School of Geography, Archaeology and Irish Studies. A native of Germany, he studied and taught in Sweden, France, Pennsylvania and Wales before settling in Ireland. His interests are rooted in social philosophies, and historical geographies of modernity and are connected to urban planning, with a particular emphasis on the geographies and histories of the French capital. His publications include a series of books edited with Georges Benko (Geography, History and Social Science, 1995; Space and Social Theory. Interpreting Modernity and Postmodernity, 1997; Human Geography: A Century Revisited, 2004 and Horizons Géographiques, 2004), a jointly authored book, Key Concepts in Historical Geography (2014) and 50 papers in journals and edited volumes. He is currently writing a book on vacant urban spaces for Routledge.

Notes

1 Hayes, “What Happens When Olympic Bids Fail?”

2 Morteau, Le consensus Olympique, 92.

3 Leopkey, Salisbury, and Tinaz, “Examining Lagacies”.

4 Masterman, “Losing Bids”.

5 Torres, “On the Merits”.

6 Strohmayer, “Non-events”.

7 Oliver and Lauermann, Failed Olympic Bids.

8 Gold and Gold, Olympic Cities; Gold and Gold, “Olympic Cities: Regeneration”.

9 Lauermann, “Temporary Projects”.

10 See Collins, Cawley, and Mulligan, “Using and Event”.

11 Lauermann, “Temporary projects,” 1885.

12 Ibid., see also Bason and Grix, “Planning to Fail?”, who make a similar point but emphasise resource activation as a key driver

13 Torres, “On the Merits”.

14 de Morgas, Llinés, and Kidd, Olympic Villages; see also Muñoz, “1908–2012,” 115.

15 Olympic Villages emerged as a temporary feature of the Games in 1932 in Los Angeles and became a staple of the Games after the Helsinki Games in 1952. Only the 1984 (Los Angeles) and 1996 (Atlanta) Games made use of student dormitories (see Muñoz, “1908–2012”).

16 See Lion.

17 Boucher, Le candidature de Paris.

18 See Archives de Paris AP 1861W87/554 and 555; 2214W348/07788; Boucher (Le candidature de Paris, 34) also laments ‘excessive’ visits by IOC members to the French capital where they lodged at the Ritz.

19 Archives de Paris 2214W348-07788, note de Garoff; see also Morteau, Le consensus olympique.

20 Archives de Paris 1861W48/F892 – which is the earliest official reference to the 1992 Games I could find to date.

21 On the recalibration of Paris towards the East, see Paris Project 27.-28.

22 Prier, “Bercy, Opéra Omnisport”.

23 In what follows, I draw in parts from Strohmayer, “Non-events”.

24 Reflections pour 1992, 1984,which even though favouring the Olympic Stadium to be built in the Bois de Vincennes already mentions the Plaine Saint Denis as an alternative site.

25 Felix and Moutarde, “Pourquoi pas le Jeux de 2012?” 21.

26 see Dionne, “France Drops Plans”; documents relative to the abandonment of the plans for the ‘Expo ‘89’ can be found in the Archives de Paris 15514W137-8; see also the dossier contained in Architecture d’aujourd’hui 238 (1985), 48–54.

27 Perrault, Bibliothèque National de France.

28 Archives de Paris 1436W187 for all facts supporting this part of the paper. Bulletin Municipale Officiel 10, 3rd December 1986, reporting on the meeting of City Hall on the 27th October. A comprehensive dossier of the debates surrounding the placement of the Aquatic Centre can be found in Archives de Paris 2135W205/02592.

29 Bulletin Municipale Officiel 10, 3rd December 1986, reporting on the meeting of City Hall on the 27th October. A comprehensive dossier of the debates surrounding the placement of the Aquatic Centre can be found in Archives de Paris 2135W205/02592.

30 IOC, Report, 33.

31 Ibid., 34.

32 Cohen, 2008, 95.

33 Cambau and Moutarde, “Paris dans la course Olympique,” 58.

34 Quinze Sites.

35 Oui Paris 2008, Vol. 2, 339.

36 APUR, “Convention”; see also the sport-centred newspaper L’Équipe on 17th mai 2000.

37 the invocation of ‘technical difficulties’ can verbatim be found in Le Parisien 19th April 2000.

38 Paris 2012, 26.

39 Marteau, Le Consensus Olympique, 95. Marteau further describes how the attempt to secure the Games for 2012 was supported by many of the people who had previously delivered the successful bid for the Albertville Winter Olympics in 1992.

40 IOC 2014; see also Jones and Pozini, “Mega-events”.

41 Durand, “La Bourgeoisie”.

42 See Strohmayer, “Performing Marginal Space”.

43 Geffroy et al., “Projecting the Metropolis”.

44 Enright, “The Political Topology”.

45 Geffroy et al., “Projecting the Metropolis,” 6.

46 Barney, Wenn, and Scott, Selling the Five Rings.

47 Clopt and Strani, “European Capitals”; Collins, “And the Winner is … ”

48 Ryan and McPherson, “Legacies of Failure”.

49 Hippke and Krieger, “Public Opposition”; Lauermann and Vogelpohl, “Fragile Growth Coalitions”.

50 Muñoz, “Historical Evolution,” 47.

51 Strohmayer, “Non-events”.

52 as quoted in Geffroy et al., “Projecting the Metropolis,” 4.

53 Oliver and Lauermann, Failed Olympic Bids, 88.

54 Ibid., 148 arrive at a similar conclusion.

55 see Archives de Paris 2214W348/07788 and 2135W205 where this question surfaces repeatedly in exchanges within City Hall.

56 Pelloux, “Clichy-Batignolles,” 110.

Bibliography

- Albers, Heike. “Berlin's Failed Bid to Host the 2000 Summer Olympic Games: Urban Development and the Improvement of Sports Facilities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33, no. 1 (2009): 502–516.

- Andranovich, Greg, Matthew Burbank, and Charles Heying. “Olympic Cities: Lessons learned from Mega-Events.” Journal of Urban Affairs 23, no. 2 (2002): 113–131.

- APUR. Convention pour l’année 2000: JO de 2008. Paris: APUR, 2000.

- Barney, Robert, Stephen Wenn, and Scott Martyn. Selling the Five Rings: The International Olympic Committtee and the Rise of Olympic Commercialism. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2002.

- Bason, Tom, and Jonathan Grix. “Planning to Fail? Leveraging the Olympic Bid.” Marketing Intelligence and Planning 36, no. 1 (2017): 138–151.

- Beriatos, Elias, and Aspa Gospodini. ““Glocalising” Urban Development: Athens and the 2004 Olympics.” Cities 21, no. 3 (2004): 187–202.

- Berkowitz, Pere, et al. “Brand China: Using the 2008 Olympic Games to Enhance China’s Image.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 3 (2007): 164–178.

- BMC (Bulletin Municipal Officiel, Ville de Paris: Débats, Conseil Municipal). “Observation sur l’ordre du jour à l’échec de la candidature de Paris aux Jeux Olympiques de 1992.” BMC 10, no. 3 décembre (1992): 419–432.

- Boucher, Véronique. La candidature de Paris aux Jeux Olympiques de 1992 et sa promotion. Paris: Université de Paris I, DESS de communication politique et sociale, 1986.

- Cambau, R., F. Felix, and N. Moutarde. “Paris dans la course Olympique.” Le Moniteur des travaux publics et du bâtiment 5039, no. 23 June (2000): 58–63.

- Cantelon, Hank, and Michael Letters. “The Making of the IOC Environmental Policy as the Third Dimension of the Olympic Movement.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 35, no. 3 (2000): 294–308.

- Carbonell, Jordi. “The Barcelona ‘92 Olympic Village.” In Olympic Villages: A 100 Years of Urban Planning and Shared Experiences, edited by Miquel Moragas Spà, Montserrat Llinés, and Bruce Kidd, 141–147. Lausanne: IOC, 1997.

- Cashman, Richard. “Olympic Legacy in an Olympic City: Monuments, Museums and Memory.” In Global and Cultural Critique: Problematizing the Olympic Games. Fourth International Symposium for Olympic Research, edited by Robert Barney, 107–114. London, Ontario: The University of Western Ontario, 1981.

- Causevic, Senija, and Renata Tomljenovic. “World Heritage Site, Tourism and the City’s Rejuvenation: The Case of Porec, Croatia.” Tourism 51, no. 4 (2003): 417–426.

- Chalkley, Brian, and Stephen Essex. “Urban Development through Hosting International Events: A History of the Olympic Games.” Planning Perspectives 14, no. 4 (1999): 369–394.

- Clopot, Cristina, and Katerina Strani. “European Capitals of Culture. Discourses of Europeanness in Valette, Plovdiv and Galway.” In Heritage and Festivals in Europe. Performing Identities, edited by Ulrich Kockel, Cristina Clopot, Baiba Tjarve, and Máiréad Nic Craith, 156–172. London: Routledge, 2020.

- Coaffee, Jon. “Urban Regeneration and Renewal.” In Olympic Cities. City Agendas, Planning, and the World’s Games, 1896–2012, edited by John R. Gold, and Margaret Gold, 150–162. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Collins, Pat. “And the Winner is … Galway: A Cultural Anatomy of a Winning Designate.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 26, no. 5 (2020): 633–648.

- Collins, Pat, Mary Cawley, and Emer Mulligan. “Using an Event to Reimage a City and its Port: The 2012 Volvo Ocean Race Finale in Galway.” Event Management 23, no. 3 (2019): 413–425.

- Crowther, Nigel. “The Salt Lake City Scandals and the Ancient Olympic Games.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 19, no. 4 (2002): 169–178.

- Dionne, Eugene J. “France Drops Plans for World’s Fair on Bicentennial of its Revolution.” The New York Times July 6, Section A, 4, 1983.

- Durand, Mathieu. “La Bourgeoisie au Charme Discret.” L’Express 2242 (1994): 87.

- Enright, Theresa. “The Political Topology of Urban Uprisings.” Urban Geography 38, no. 4 (2016): 557–577.

- Essex, Stephen, and Brian Chalkley. “Olympic Games: Catalyst of Urban Change.” Leisure Studies 17 (1998): 187–206.

- Felix, Frédéric, and Nathalie Moutarde. “Pourquoi pas les Jeux de 2012?” Moniteur des travaux publics et du bâtiment 5095 (20 July 2001): 21.

- Fougère, Édouard. Les entrepôts à domicile et les entrepôts reels à Paris. Paris: Berger-Lavrault & Cie., 1905.

- Garcia, Beatriz. “Urban Regeneration, Arts Programming and Major Events – Glasgow 1990, Sydney 2000 and Barcelona 2004.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 10, no. 1 (2004): 103–118.

- Garcia-Ramon, Maria-Dolors, and Abel Albet. “Pre-olympic and Post-olympic Barcelona, a ‘Model’ for Urban Regeneration Today?” Environment and Planning A 32, no. 8 (2000): 1331–1334.

- Geffroy, Damian, R. Oliver, L. Juran, and T. Skuzinski. “Projecting the Metropolis: Paris 2024 and the (re)scaling of Metropolitan Governance.” Cities 114 (2021): 103189.

- Gold, John R., and Margaret Gold, eds. Olympic Cities. City Agendas, Planning, and the World’s Games, 1896–2012. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Gold, John R., and Margaret Gold. “Olympic Cities: Regeneration, City Branding and Changing Urban Agendas.” Geography Compass 2, no. 1 (2008): 300–318.

- Gospodoni, Aspa. “Urban Morphology and Place Identity in European Cities: Built Heritage and Innovative Design.” Journal of Urban Design 9 (2004): 225–248.

- Haugen, Heidi. “Time and Space in Beijing’s Olympic Bid.” Norwegian Journal of Geography 59, no. 3 (2005): 217–227.

- Hayes, Graeme. “What Happens When Olympic Bids Fail? Sustainable Development and Paris 2012.” In Olympic Games, Mega-Events and Civil Societies. Global Culture and Sport, edited by Graeme Hayes, and John Karamichas, 172–191. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Hiller, Harry. “Post-event Outcomes and Post-modern Turn: The Olympics and Urban Transformations.” European Sport Management Quarterly 6, no. 4 (2006): 317–332.

- Hippke, Anna-Sophie, and Jörg Krieger. “Public Opposition against the Olympic Games: Challenges and Considerations in Light of Hamburg’s 2024 Olympic Bid.” Journal of Qualitative Research in Sports Studies 9, no. 1 (2015): 163–176.

- International Olympic Committee (IOC). Report of the IOC Evaluation Commission for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad in 2008. Lausanne: IOC, 2001.

- International Olympic Committee (IOC). Olympic Agenda 2020: 20+ 20 Recommendations. Lausanne: International Olympic Committee, 2014.

- Jones, Zachary, and Davide Ponzini. “Mega-events and the Preservation of Urban Heritage: Literature Gaps, Potential Overlaps, and a Call for Further Research.” Journal of Planning Literature 33, no. 4 (2018): 433–450.

- Lauermann, John. “Temporary Projects, Durable Outcomes: Urban Development through Failed Olympic Bids?” Urban Studies 53, no. 9 (2016): 1885–1901.

- Lauermann, John, and Anne Vogelpohl. “Fragile Growth Coalitions or Powerful Contestations? Cancelled Olympic Bids in Boston and Hamburg.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49, no. 8 (2017): 1887–1904.

- Leopkey, Becca, Paul Salisbury, and Cem Tinaz. “Examining Legacies of Unsuccessful Olympic Bids: Evidence from a Cross-Case Analysis.” Journal of Global Sport Management 6, no. 3 (2021): 264–291.

- Masterman, Guy. “Losing Bids, Winning Legacies: An Examination of the Need to Plan for Olympic Legacies Prior to the Bidding.” In Pathways: Critiques and Discourse in Olympic Research, edited by Robert K. Barney, Michael K. Heine, Kevin B. Wamsley, and Gordon H. MacDonald, 171–178. London, Ontario: The University of Western Ontario, 2008.

- May, Vincent. “Environmental Implications of the 1992 Winter Olympic Games.” Tourism Management 16, no. 4 (1995): 269–275.

- McCallum, Katherine, Amy Spencer, and Elvin Wyly. “The City as an Image-creation Machine: A Critical Analysis of Vancouver's Olympic Bid.” Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 67 (2005): 24–46.

- Morteau, Alexandre. “Le consensus Olympique: la construction politique et administrative des grands évènements sportifs internationaux, d’Albertville 1992 à Paris 2024.” PhD thesis in Political Science, Univerite2 de Paris-Dauphine, 2022.

- Mouraux, Lionel. Bercy. Paris: Éditions L.M., 1983.

- Muños, Francesc. “Historical Evolution and Urban Planning Typologies of Olympic Villages.” In Olympic Villages: A 100 Years of Urban Planning and Shared Experiences, edited by Miquel de Morgas Spà, Montserrat Llinés, and Bruce Kidd, 27–51. Lausanne: IOC, 1997.

- Muños, Francesc. “1908–2012. L’Urbanisme des Villages Olympiques.” Quaderns d’arquitectura I urbanisme 245, no. Q5.0 (2005): 110–131.

- Muños, Francesc. “Olympic Urbanism and Olympic Villages: Planning Strategies in Olympic Host Cities, London 1908 to London 2012.” Sociological Review 54, no. supplement 2 (2006): 175–187.

- Nasser, Noha. “Planning for Urban Heritage Places: Reconciling Conservation, Tourism, and Sustainable Development.” Journal of Planning Literature 17, no. 4 (2003): 467–479.

- Nelson, Suzy. “The Nature of Partnership in Urban Renewal in Paris and London.” European Planning Studies 9, no. 4 (2001): 483–501.

- Oliver, Robert, and John Lauermann. Failed Olympic Bids and the Transformation of Urban Space. Lasting Legacies? London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2017.

- Oui Paris. Ville Candidature. Paris: GIP, 2000.

- Paris 2012 Ville Candidature. Official document submitted to the IOC in 2004. https://library.olympics.com/Default/doc/SYRACUSE/28448/paris-2012-ville-candidate-paris-2012-candidate-city-comite-de-candidature-paris-2012.

- Paris Olympiques. 12 projets d’architecture et d’urbanisme pour les Jeux del 2008. Paris: Editions du Moniteur, 2001.

- Paris Projet. Perspectives d’aménagement de l’Est de Paris. Paris: APUR, 1987.

- Paz Balibrea, Mari. “Urbanism, Culture and the Post-industrial city: Challenging the ‘Barcelona Model’.” In Transforming Barcelona, edited by Tim Marshall, 205–224. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Pelloux, Patricia. “Clichy-Batignolles, le renouveau d’une emprise sous-utilisée.” Paris Projet 36/37. Paris: APUR (2005): 110–120.

- Perrault, Dominique. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Basel: Birkhäuser, 1995.

- Prier, P. “Bercy, Opéra Omnisport.” Urbanisme et Architecture 231, no. 2 (1989): 48–49.

- Pyo, Sungsoo, Raymond Cook, and Richard Howell. “Summer Olympic Tourist Market — Learning from the Past.” Tourism Management 9, no. 2 (2002): 137–144.

- Quinze sites recensés pour accueillir le village Olympique aux JO 2008’. Moniteur des travaux publics et du bâtiment 5007, 12 november 1999: 138.

- Roult, Romain, and Sylvain Lefebvre. “Reconversation des heritages olympiques et renovation de l’espace urbain: lec as des stades olympiques.” Géographie Economie Société 12, no. 4 (2010): 367–392.

- Ryan, Annmarie, and Gayle McPherson. ““Legacies of Failure to Win the City of Culture: Liminality, Civicism and Change.” City, Culture and Society 31 (2022): 100488.

- Shoaf, Amanda. “Bercy’s ‘Jardin de la Mémoire’: Landscape as a language of memory.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 11, no. 1 (2007): 25–35.

- Strohmayer, Ulf. “Performing Marginal Space: Film, Topology and the Petite Ceinture in Paris.” (with Jipé Corre providing art work). Liminalities 8, no. 4 (2012): 1–16.

- Strohmayer, Ulf. “Non-events and their Legacies: Parisian Heritage and the Olympics that Never Were.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 19, no. 2 (2013): 186–202.

- Strohmayer, Ulf. “Dystopian Dynamics at Work: The Creative Validation of Urban Space.” In The International Handbook on Spaces of Urban Politics, edited by Andrew Jonas, Byron Miller, Kevin Ward, and David Wilson, 542–554. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Strohmayer, Ulf. “Urban Renewal and the Actuality of Absence: the ‘Hole’ (‘Trou’) of Paris, 1973.” In A Place More Void, edited by Paul Kingsbury, and Anna Secor, 29–47. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2021.

- Toohey, Kristine, and Anthony Veal. The Olympic Games: A Social Science Perspective. 2nd ed. Wallingford: CABI, 2007.

- Torres, Cesar. “On the Merits of the Legacy of Failed Olympic Bids. Paper Written in the Framework of the IOC’s OSC Postgraduate Grant Selection Committee (2011 meeting).” https://soar.suny.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.12648/2531/pes_confpres/4/fulltext%20%281%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Tweed, Christopher, and Margaret Sutherland. “Built Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Urban Development.” Landscape and Urban Planning 83, no. 1 (2007): 62–69.

- Vincent, Amanda. “Bercy’s ‘Jardin de la Mémoire’. Ruin, Allegory, Memory.” Landscape Journal 29, no. 1 (2010): 36–51.

- Waitt, G. “Playing Games with Sydney: Marketing Sydney for the 2000 Olympics.” Urban Studies 36, no. 7 (1999): 1055–1077.

- Waitt, Gordon. “The Olympic Spirit and Civic Boosterism: The Sydney 2000 Olympics.” Tourism Geographies 3, no. 3 (2001): 249–278.

- Weiss, Sean. “Specters of Industry. Adaptive reuse in Paris as Industrial Patrimony.” Journal of Architectural Education 63, no. 1 (2009): 135–140.

- Welch, Edward. “Objects of Dispute. Planning, Discourse, and State Power.” French Politics, Culture & Society 36, no. 2 (2018): 102–125.

- Wenn, Stephen, and Scott Martyn. “‘Tough Love’: Richard Pound, David D’Alessandro, and the Salt Lake City Olympic Bid scandal.” Sport in History 26, no. 1 (2006): 64–90.