ABSTRACT

Attention on children and young people’s (CYP) wellbeing has increased internationally over the past two decades, particularly in the context of education. This small scale, preliminary study was conducted across four state-funded schools in England (two primary; two secondary) amidst a time of policy change that saw the introduction of Mental Wellbeing Support Teams in schools, and the mandating of statutory Health Education curricula. The study investigated whether psycho-informed lessons could be developed aligned to curriculum guidelines, and how pupils would engage with this learning content. Drawing on Positive Education (PE) theory, and Self-Determination theory (SDT) the researchers worked collaboratively to co-develop and deliver lessons to CYP (aged 9–11 years, and 14–15 years). This paper describes the theoretical underpinnings of the lessons, learning activities used, and critically reflects on pupils’ engagement. Implications for practice are considered and recommendations made regarding possible future teaching of mental wellbeing in England.

Introduction

Attention on children’s and young people’s (CYP) psychological wellbeing has increased internationally over the past two decades in the context of education (Layard & Dunn, Citation2009; Rappleye et al., Citation2019). The attention in England can be attributed to evidence pointing towards a decline in mental health (The Children’s Society, Citation2019; Vizard et al., Citation2021), and emphasis on positive education (PE) arising from the science of positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihaly, Citation2000). Furthermore, COVID-19 challenges faced by CYP (Stavridou et al., Citation2020) sharpened the focus of educators on the need for schools to prepare CYP to live in an ‘unpredictable’ future (Ergas et al., Citation2022).

Schools have a powerful role not only in nurturing CYP’s wellbeing, but explicitly teaching them what it means to be well (Winship & MacDonald, Citation2018). Schools are responsible for equipping CYP with knowledge about how to live fulfilled lives, including how to look after their wellbeing, why it is important, what might hinder it, and knowledge, skills, and the confidence to know when and how to seek help. Increasingly, a symbiotic approach of wellbeing for learning and learning for wellbeing (Crow, Citation2008) is advocated by psychologists and government (Bonell et al., Citation2014; Department for Education, Citation2014). Yet some academics engage in a ‘dangerous’ discourse (Clarke, Citation2020) pitting wellbeing against other educational goals, arguably undermining its value.

Questioning boundaries between education and social care, Health Committee evaluations (for example, Citation2014) underline the ‘siloed’ conceptualisation of education services as separate from mental health (MH). Consequently, government introduced two policies acknowledging CYP’s wellbeing as imperative. First, the introduction of Health Education as part of statutory National Curricula (Department for Education, Citation2018). The research reported herein presents an investigation into how this new curriculum can be targeted using appropriate learning objectives (LOs) and research-informed activities, with critical reflection to inform future teaching and curriculum development (Lendrum and Humphrey, Citation2012). Second, government created Education Mental Health Practitioner (EMHPs) roles with the responsibility of helping schools deliver psychoeducation and promoting CYP’s wellbeing (Ellins et al., Citation2021).

Educational psychologists (EPs) and EMHPs are integral to the whole-school delivery of comprehensive MH provision. However, for EPs/EMHPs to effectively support CYP, services need to be targeted in ways attuned to CYP’s daily school experiences. Having an awareness of each school’s MH provision, its policies, curricula, and ethos, is essential for EPs in understanding CYP’s experiences within that school. Skilled EPs/EMHPs may integrate curriculum knowledge into their practice to deliver cohesive, intersectoral MH support (Tamminen et al., Citation2022).

Literature review

Defining CYP’s mental wellbeing

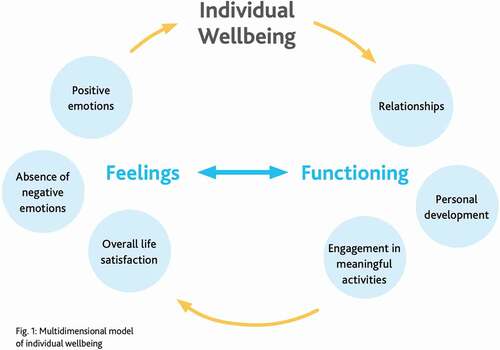

Wellbeing has been defined according to two overlapping forms of experience: hedonic (feelings) and eudaimonic (functioning; Huppert & So, Citation2011). Initially, the first wave of positive psychology was concerned with the former, hedonia, conceptualised as comprised of three facets forming one’s overall ‘subjective wellbeing’ (SWB); the presence of positive emotions, absence of negative emotions, and one’s overall life satisfaction (Diener et al., Citation1999). The second wave expanded the wellbeing construct, accounting for its multidimensionality and eudaimonic wellbeing (EWB) component and described individuals’ personal development, sense of purpose, and fulfilment in life (Lomas et al., Citation2020). The difference between SWB and EWB? The former maximises momentary experiences of ‘happiness’, while the latter favours the ‘greatest fulfilment in living’ (Waterman, Citation1993). Within positive psychology, CYP’s wellbeing is regarded as no less complex than adults’ (Dinisman & Ben-Arieh, Citation2016), yet research is characterised by an over-focus on hedonia at the neglect of eudaimonia (Casas & González-Carrasco, Citation2021; Witten et al., Citation2019), in spite of findings from a systematic review suggesting eudaimonic experiences are most pertinent to CYP’s development (Avedissian & Alayan, Citation2021).

Towards positive education (PE)

In recent decades educators have questioned the purpose of education (Biesta, Citation2009) and whether it serves a new generation of post-modern beings (Inglehart, Citation1997). Ideas of ‘knowledge rich’ curricula (Young and Muller, Citation2013), providing ‘powerful’, ‘academic’ foundations, remain pervasive in England. However, many regard this agenda as short-changing pupils who require a more all-encompassing school experience (White, Citation2016). Parallel to this, psychology as a discipline was rethought through the science of positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihaly, Citation2000) which sought to understand humans’ flourishing as opposed to suffering (Lomas et al., Citation2020). These two pursuits, that is, the broadening of education to encompass the whole-child, and the reimagining of psychology to encompass the whole-individual, are combined in positive education (PE). EP/EMHPs’ roles to support CYP’s social, emotional and mental wellbeing (Lyonette et al., Citation2019) suggest PE theory and evidence are relevant to their practice to enhance the MH support CYP receive.

Embracing positive education (PE)

PE focuses on cultivating individual traits, both hedonic and eudaimonic, such as happiness, wellbeing, intrinsic motivation, resilience, and mindset (Arguís-Rey, Citation2021). In line with the second wave of positive psychology, PE focuses on teaching CYP about feelings alongside their wider functioning in life. PE’s dual emphasis on hedonia and eudaimonia aligns with health research findings that YP’s wellbeing constitutes more than the presence of pleasure (Avedissian & Alayan, Citation2021). Indeed, over-emphasising hedonia overlooks evidence suggesting eudaimonia predicts longer-term wellbeing benefits (Huta & Ryan, Citation2010) and is positively associated with both CYP’s broader wellbeing (Gentzler et al., Citation2021; Ruini & Cesetti, Citation2019). In addition, eudaimonia is positively predictive of CYP’s attainment (Boncquet et al., Citation2020; Clark & Teravainen-Goff, Citation2018), while hedonia is negatively predictive (Marquez, Citation2021).

PE approaches like Positive Youth Development (PYD; Romer & Hansen, Citation2021) are grounded in the Aristotlean principles of eudaimonia (Aristotle, Citation1985); seeing individuals as having the capacity to be active agents in their lives. PYD positions positive feelings as the motivator of personal development. Others propose curricula that harmonise hedonia and eudaimonia; teaching CYP how to understand and manage their emotions alongside how to care for themselves and others and contemplate their unique contribution to the world (Coleman et al., Citation2011; Layard & Dunn, Citation2009). Two different approaches to implementing PE in schools are the explicit, ‘taught’ curriculum, and the implicit, ‘caught’ curriculum, whereby wellbeing is experienced at a whole-school level (Green et al., Citation2021). Hoare et al. (Citation2017) reflect on the effectiveness of delivering whole-school wellbeing programmes, proposing an iterative four-step process: learn it, live it, teach it, and embed it.

The focus of this study is on the first step, ‘learn it’; the process of teaching wellbeing through taught curricula since, as PE advocates, CYP require taught curricula devoted to wellbeing (Formby & Wolstenholme, Citation2012). While whole-school wellbeing promotion provides CYP with critical reinforcement, without equipping individual CYP with foundational knowledge and understanding of wellbeing, the extent to which wellbeing can be ‘lived’ and ‘embedded’ is questionable.

Teaching mental wellbeing: what, how and who

Following agreement that wellbeing should be explicitly taught, though this is not unanimous (see, Smith, Citation2008), are questions of what, how and who should teach it. To the question of what, the authors argue that CYP should be taught about both hedonia and eudaimonia. Relevant eudaimonic wellbeing topics include how to develop meaningful relationships, engage in worthwhile activities in free time, and find fulfilment in life (Brighouse, Citation2006). Yet whereas PE emphasises teaching eudaimonia and hedonia, the approach in statutory National Curricula seemingly favours hedonic conceptions. Curriculum guidelines describe teaching children about the ‘range’ and ‘scale of emotions’, ‘how to recognise and talk about their emotions’, ‘how to judge whether what they are feeling’ is ‘appropriate’ (Department for Education, Citation2021).

Although one learning objective (LO) pertains to the impact of ‘activities’ on wellbeing, the eudaimonic essence of PE; living ‘worthwhile’ lives, ‘fulfilment’, ‘meaning’, ‘goals’, and ‘mindsets’ is comparatively absent. Altogether, National Curricula suggest teaching CYP that their wellbeing is something to be ‘managed’, whereas PE champions wellbeing as something to be nurtured. Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, Citation2000; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000) best articulates this through its acknowledgement of individuals’ innate psychological needs, to feel competent, autonomous and related to others. What is lacking in existing curricula is articulation of CYP’s needs, and a mandate for teachers/EPs/EMPHs to enable CYP to question how their needs are met.

How should wellbeing be taught? According to SDT, it should be taught in ways that brings CYP’s awareness to their needs and uses pedagogy to meet them. Autonomy-supportive classrooms use learning to maximise pupil involvement while minimising teacher-controlled actions (Wehmeyer et al., Citation2021). Collaborative group work also supports pupils’ need for autonomy and relatedness. Oades and colleagues (Oades et al., Citation2021) further underline the importance of providing CYP with ‘wellbeing literacy’, allowing them to communicate their wellbeing and recognise the wellbeing of others. Such vocabulary provides CYP with the tools (competence) to understand their feelings and experiences and engage in communication about wellbeing with others (fostering relatedness).

While research suggests that many teachers struggle to see their responsibilities as extending beyond ‘academic’ domains, or that wellbeing is even teachable (Waters, Citation2021), evidence demonstrates the effectiveness of teacher-led wellbeing curricula. Nationwide interventions delivered by trained teachers, for example, Healthy Minds, documented significant improvements in pupils’ wellbeing (Lordon & McGuire, Citation2019). Other teachers acknowledge the need to teach wellbeing as part of mainstream curricula (Baxter, Citation2019), yet express concerns that they will become ‘the therapist’ (Shelemy et al., Citation2019). Some teachers worry that their responsibilities will seep into the realm of MH practitioner; a valid concern, given the accountability pressures teachers face, impacting their own wellbeing (Brady & Wilson, Citation2021). Yet the idea that teachers are not responsible for educating CYP about wellbeing jars with the role that teachers are invited to play in PE, and their responsibility to deliver statutory Health Education; with initial teacher training recommended to cover the foundations of CYP’s emotional development (Carter, Citation2015). Not all children have access to emotionally attuned adults at home, therefore schools are integral ‘seedbeds’ for lifelong wellbeing (Music, Citation2017). However, attuned teachers require education systems that value them as whole individuals with emotional lives, capacity, or (in)capacity.

The current research

The utility of ‘outside agencies’ in offering critical support for schools in fostering CYP’s wellbeing (Department for Education, Citation2018; PSHE Association, Citation2019), with research in primary schools finding the effectiveness of teaching wellbeing depended on using external expertise (Stirling & Emry, Citation2016). In addition to their experience as a researcher working in schools, the lead researcher of the present study delivers wellbeing interventions to children (aged 8-11) for a local children’s charity. The second author is an experienced former teacher and PSHE expert working for a local authority (LA). Together, the authors harnessed their shared knowledge and skillsets to design wellbeing lessons, delivered by the lead researcher in collaboration with the schools.

Research aims

The present study was undertaken as part of a wider mixed, multi-method research project with the aim of understanding children and adolescents’ experiences of wellbeing in England’s state-funded schools. The project was conducted during the Green Paper consultation on Transforming CYP’s Mental Health Provision (Department of Health & Department for Education, Citation2017). The quantitative phase of the project remotely examined the relationship between pupils’ wellbeing, mindsets, goals, and attainment in 21 Primary and seven Secondary schools. The qualitative phase involved a nested sample (two Primary and two Secondary schools) to delivery wellbeing lessons as part of Health Education, and follow-up group interviews with 27 children and 30 adolescents. For further information, see the pre-registrations for the quantitative and qualitative phases of the project via the Open Science Framework (OSF Citation2022a; Citation2022b).

The current paper documents part one of the qualitative phase that aimed to investigate the feasibility of designing psycho-informed lessons aligned to new ‘mental wellbeing’ and ‘emotional health’ components of Health Education, and how pupils would engage with the learning content. To this end, the present article:

Describes the development of new wellbeing lessons for primary and secondary pupils, their basis in psychological theory, and alignment to Health Education curricula,

Describes specific learning activities trialled,

Critically reflects on how learners engaged with learning content and activities, and

Makes recommendations to improve outcomes of teaching wellbeing within mainstream schools, underlining the relevance and role of EPs/EMHPs to reinforce curricula.

Methodology

Participating schools

Four state-funded schools (two Primary; two Secondary) participated from an English county that performed within the worst 20% (Social Mobility & Child Poverty Commission, Citation2016; ).

Table 1. Pupil demographics for participating schools compared to national averages.

Table 2. Percentage of pupils with a SEN/EHCP compared to same-age peers at the national-level.

Schools expressing an interest in taking part in this phase of the project (wellbeing lessons) at initial recruitment (email to headteachers) were invited to participate following phase one (where all schools participated). Five Primary and three Secondary schools expressed initial interest in participating. Subsequently, two Primary and two Secondary schools participated due to either lack of response to follow-up invitations or unavailability of the remaining schools. At project’s culmination, all participating schools were provided with bespoke research reports, lesson plans, and a teacher training webinar.

Children aged 9–11 (n = 45) in two primary schools, and young people aged 14–15 (n = 100) in two secondary schools participated. Primary pupils were split into year groups to participate; delivered to groups of 15–20 pupils. Secondary pupils participated in lessons in mixed ability classes of approximately 28 same-age pupils. The institution where the first author was based granted ethical approval for school visits between April – May 2021, with lessons delivered on two consecutive days for primary and over two consecutive weeks for secondary schools. Parental written consent and pupil assent were obtained. Prior to school visits, the researcher met with teachers for a briefing to discuss the lesson content and requirements of vulnerable pupils or those with additional needs or disability, and pupils (either virtually or in-person) to deliver a short informative presentation about the research. The lead researcher had up-to-date training, through the children’s charity for which they work, in safeguarding, conducting suicide risk assessments, and CYP’s wellbeing; this provided the skills and knowledge required to deliver lessons alongside teachers (present throughout).

Data collection

Lesson plans, field notes, audio recordings of the lessons, and photographs of pupils’ work guided the authors’ critical reflections. Additionally, a small amount of qualitative data from group interviews with pupils, undertaken as part of the wider project, was utilised. Specifically, pupils’ responses to one interview question: ‘To what extent do you feel it is or is not important to have lessons on mental wellbeing at school?’ and a follow-up: ‘Why do you/don’t you think mental wellbeing are/aren’t important?’ provided CYP insights. Interviews were, however, conducted to answer wider research questions from the project; a full analysis is not presented here.

Pupils were invited to participate in semi-structured group interviews at the culmination of the second lesson. The researcher verbally communicated the interview aims, assurance of their anonymity, how their responses would be used, and selected 27 children (12 females; 15 males) and 30 adolescents (15 females; 13 males; 2 non-binary) to participate based on their different levels of engagement in the lessons (for example, to ensure interviewees included a mix of pupils who spoke up more/less in lessons) and demographic backgrounds (to ensure interviewees included pupils with/without SEND/EHCPs, of different ethnicities, and those eligible/ineligible for FSM). Interview groups of three were organised by teachers using their professional judgement of social dynamics that would be most conducive to all pupils feeling comfortable speaking, and school timetabling. Children were interviewed alongside same-gender peers.

Designing the wellbeing lessons

The authors scrutinised the learning objectives (LOs) in national Health Education guidelines for ‘mental wellbeing’ and ‘emotional health’, which outline what Primary- and Secondary-aged pupils ‘should know’ by the end of school. Existing curricula targeting PE topics were reviewed, including from the LA’s PSHE Service and children’s charities, to gauge approaches to teaching wellbeing and their theoretical underpinnings.

Based on initial scoping, theories informing the pedagogical approach and curriculum-content for lessons were decided. Pedagogy used to teach PSHE was an important consideration as OfSTED (Citation2005) has raised concerns about teachers relying on tangible, ‘traditional’ approaches which do not actively engage CYP to challenges their thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes. A socio-cultural approach to learning, where pupils are actively engaged in decision-making and discussion, was utilised (Daniels et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, the researchers designed activities that enabled CYP to creatively express their ideas as they provide ways to safely explore their internal worlds (Deboys et al., Citation2017) which can be difficult to articulate. Providing CYP with opportunities to engage creatively in learning, using crafts and visual forms, personalises the learning experience, making it more memorable for pupils (Skills & Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services, Citation2010).

Positive educationalists underline the importance of making learning-content relatable and applicable to the people and situations in CYP’s lives (Arguís-Rey, Citation2021). The authors designed activities that were content- and context-focused, centred on CYP’s experiences of wellbeing in school specifically. Further, self-determination theory (SDT) served as a guide for ensuring CYP were introduced to their innate psychological needs, evidenced as critical to healthy child development (Benita, Citation2020; Diseth et al., Citation2012). SDT also informed pedagogy, maximising CYP’s autonomy by inviting their ideas in ways most meaningful to them (for example, drawings, writing, speaking), and relatedness was promoted using group work. PSHE encourages teachers to use small group work to facilitate learning through breakout discussions separate from the whole class (PSHE Association, Citation2018) in order to mitigate pupils feeling exposed or ‘put on the spot’; exploring topics generally and collectively, rather than individually.

However, SDT’s eudaimonic focus, to meet the learning objectives (LOs) in the statutory National Curriculum pertaining to emotional wellbeing, it was necessary to explicitly target hedonia. While social wellbeing theory (SWB) purports that maximised positive emotions, minimised negative emotions, and overall life satisfaction (Diener et al., Citation1999) constitute high wellbeing, such approaches are potentially simplistic and potentially harmful to teach CYP. The idea that individuals should minimise negative emotions was perceived as unhelpful, as managing all emotions is a necessary part of daily life. An alternative SWB theory proposed by neuropsychologists (Damasio, Citation2021; Immordino-Yang & Damasio, Citation2007), positioning emotions as providing individuals with important information about how to manage life and regulate their needs, was instead used.

After solidifying guiding theories, the researchers pinpointed LOs from National Curriculum Lesson one, focused predominantly on ‘feelings’ wellbeing; lesson two would focus on ‘functional’ wellbeing, while seeking connections between the two. As requested by teachers, lessons lasted between 60-90 minutes for children and 50-60 minutes for young people. First drafts, developed by the lead researcher, were reviewed by the second author, and second drafts were reviewed by two primary and one secondary teacher, and a senior researcher at the university where the lead researcher was based, with all feedback leading to the redesign of final lesson plans.

Lessons began by establishing and reminding pupils of the ground rules for engagement, including pupils’ ‘right to pass’, and safeguarding procedures. PowerPoint presentations guided pupils through each lesson, highlighting key terms (for example, emotional vocabulary) and reinforcing complex ideas discussed through visuals (for example, a diagram presenting different wellbeing components).

Findings

Primary school wellbeing lessons

Lesson one’s LO: To explore what it means to look after the wellbeing of ourselves and others in school; elicited pupils’ ideas about what it might mean to feel good at school, the comfortable and uncomfortable emotions they might experience, and how to take care of their wellbeing. Pupils were first asked to think of some ‘good’ and ‘less good’ feelings, written on the board, and then presented with a feelings grid to elaborate, with any unfamiliar emotions clarified. The grid served as a reference for pupils in both lessons to scaffold learning. The starter activity was a guided meditation to music, following Bethune’s (Citation2018) advice on how to effectively teach children mindfulness, which asked children to ‘walk’ through a typical school day, asking them to imagine experiencing it with a friend who was ‘feeling good’ and then ‘feeling they were doing well’. Afterwards, pupils were invited to share the feelings and experiences imagined, forming the basis of a class discussion about what it means to feel good and feel they are doing well at school. Pupils’ ideas were written on the board, organised into emotions and experiences. Examples of the experiences that made pupils feel good at Silver Birch included:

Getting a good grade

Playing with friends

Helping others

Interacting with peers (being ‘active’) during lessons

Getting things right in lessons

Getting compliments

Seeing their schoolwork on display/getting public acknowledgement/ ‘credit’

Pupils at Oak Wood highlighted additional experiences:

Getting ‘dojo’ points for good behaviourFootnote1

Having people to play with at breaktime

Having opportunities to be creative (e.g., doing art or story writing)

Doing physical exercise (e.g., team sports or running)

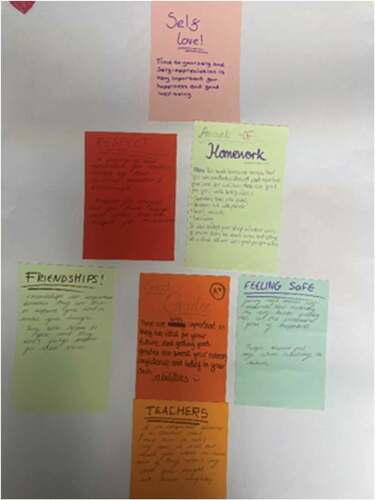

Having established pupils’ school-specific wellbeing experiences, the main activity involved pupils working in groups (4–5) to create a ‘Good Advice Box’ for an imaginary friend in another school who was not feeling very good (specifically they were feeling sad, angry, and lonely). Pupils were invited to use ideas from the meditation to construct their advice and provided sentence starters and connector words for different ability levels to help structure their writing (Graham et al., Citation2005). Scrap paper was provided for pupils to practice writing their pieces of advice before deciding on their ‘final’ wording to go into their boxes (). Examples of pupils’ advice included:

‘Do things that make you happy’

‘Tell somebody you trust your worries’

‘Play your part when your friends need you’

‘Try your best’

‘Don’t give up when it gets hard’

‘Remember that you look good today!’

‘’If you are angry get a bit of paper just write your feelings and then scrunch the paper up and put it in the bin’

‘My advice to you when you feel angry, think of a birthday cake and blow out the candles and your anger with it, repeat 5x’

Central to this activity was pupils working as a team, assigning roles to each member (manager, timekeeper etc) and share the responsibilities of creating their boxes. Pupils had 30 min to create their boxes, and once completed, a show-and-tell was facilitated as a plenary activity. To sustain pupils’ learning and encourage them to ‘live it’ beyond the classroom (Hoare et al., Citation2017), lesson one concluded by asking the class what they would like to happen to their boxes after the lesson. Pupils suggested ideas including sending the box to a different school; pupils at Silver Birch decided they wanted to send a box to Oak Wood, whereby those with pupils used ideas as inspiration for creating their own.

Lesson two’s LO: To understand how we can achieve our learning goals whilst also feeling good at school, extended pupils’ learning by focusing on experiences of eudaimonia at school (working towards goals) and associated emotions. The starter invited pupils to think of role models in their life currently working towards long-term goals. The difference between short- and long-term goals were discussed, and pupils completed worksheets illustrating who their role model was in relation to them, their long-term goal, and how they might be feeling whilst working towards it (using the feelings grid). For example, one pupil wrote:

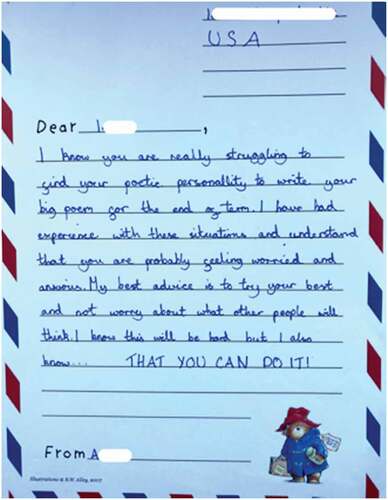

The main activity extended pupils’ thinking about and sharing the experience of working towards a goal in relation to one of their own short-term, school-related goals. Pupils chose one of the examples to write a letter of encouragement for a friend (real or imaginary) working towards that specific goal who was not feeling good about their progress. In their letters, pupils were asked to: express empathy for their friend (naming emotions they might be feeling), offer them help, suggest ways their friend can take care of their self while working towards their goal, and encourage them. The purpose of this activity was to bring together the experiences of feeling and functioning by asking pupils to consider the emotions experienced when striving towards goals. The plenary activity consisted of volunteers reading their letters aloud (often directly to a peer) and a volunteer played ‘post person’ to collected everyone’s letters (). Pupils were asked what they would like to happen to their letters. Suggestions included giving them to the recipient to keep or putting them on display.

Figure 2. Example of a letter to a friend written by a Year 6 pupil. Letter illustrations by R.W. Alley (Citation2019).

Secondary school wellbeing lessons

Lesson one’s LO: To understand the feelings and experiences that contribute to the wellbeing of ourselves and others in school, helped pupils understand what influences their wellbeing, and what wellbeing feels like. The starter activity involved using a ‘washing line’ to present pupils’ ideas. In groups of 2-3, pupils were invited to imagine someone who is feeling good at school and write three feelings they experience, and three things that make them feel good. Pupils pegged their papers onto the washing line and these were shared with the class.

The Secondary-level statutory Curriculum includes LOs whereby pupils must understand how particular experiences contribute to their overall wellbeing (for example, being connected to others, community participation and service-based activities). Following the starter, a diagram was used to consolidate learning and ensure pupils were given a comprehensive idea of what wellbeing constitutes ().

Figure 3. wellbeing overview used in secondary school lessons; reproduced with permission from Cambridge Assessment International Education (2020).

The washing line was left up for pupils to use as a resource for the main activity, a ‘priorities setting’ exercise, involving pupils working in groups of 4-5. The researcher reminded pupils about the aim of the research project: to better understand CYP’s experiences of wellbeing at school. This exercise therefore fed into the research agenda: to enable adults to understand CYP’s priorities when it comes to nurturing their wellbeing at school. The task for pupils was to present the top seven aspects/experiences of school they regarded most important for wellbeing in the form of a poster. Then, they were invited to rank their priorities in order of importance, following which they were given seven coloured cards to display each. Pupils were provided with large sheets of paper, coloured pens, and glue sticks to present their hierarchy of priorities with the most important at the top of a diamond shape and ‘least’ important at the bottom; an effective method used to help pupils organise their ideas (Niemi et al., Citation2015; ). They were asked to ensure their posters clearly communicated each priority with explanations of what the priority meant to them, and why they considered it important for wellbeing. The most common priorities were:

Being able to trust teachers and friends, and having social support

Good relationships with others

Feeling safe and comfortable in school

Getting good grades

Positive teacher–pupil relationships

Lesson two’s LO: To understand how the goals we aspire to achieve in school can be balanced alongside our wellbeing needs, focused on pupils’ eudaimonic wellbeing (personal development and engaging in meaningful activities) and helping pupils understand how to take care of their wellbeing whilst pursuing goals. Pupils were reminded of the experiences that constitute wellbeing using the diagram from lesson one () and top priorities. To start, pupils were invited to think individually about someone in their life who accomplished a goal, considering the steps this person took to achieve it, and how they might have felt while pursuing it. The main activity extended this learning, asking pupils to think about the purpose of school, and personal school-related goals they were working towards. In groups of 4-5, pupils created Good Advice Posters for a friend working towards one of their school-related goals.

Discussion and limitations

Reflections on primary school lessons

Altogether, young pupils appeared to grasp not only the hedonic aspects of wellbeing but also more complex eudaimonic elements that are often neglected in curricula. Pupils’ own reflections from interviews undertaken suggested the lessons made them feel cared for and provided an important space for them to understand their emotions.

Why do you think these lessons are important?

Because I think young people need to um, feel like people care what they feel like at school (Eric, Age 11)

However, challenges included the language used to introduce emotions. Children understand emotional hierarchies and differentiate between basic emotion families, including superordinate emotions (for example, ‘positive’ versus ‘negative’) (Fischer et al., Citation1990; Grosse et al., Citation2021). The lessons therefore needed to help children differentiate between emotional experiences as a starting point while avoiding labelling emotions as ‘negative’ or ‘positive’ so as to circumvent potential vilification of emotions, or ‘toxic positivity’. Emotions were instead referred to as ‘good’ and ‘less good’. ‘Comfortable’ and ‘less comfortable’ could be used instead, yet pupils’ experiences of comfort and discomfort may differ depending on their lived experiences. Certain patterns of so-called ‘negative’ emotions, for example, those associated with trauma, can be experienced as comforting by individuals (LePera, Citation2021). The language of emotions is thus something for practitioners to further consider; perhaps using colours instead.

Affording pupils’ autonomy in how they learn, advocated by SDT (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000), informed the researchers’ pedagogy. The Good Advice Box activity required pupils to allocate team roles, coordinate the creation of boxes, co-write advice to put inside, and share their decoration. In practice, this amount of freedom proved challenging for many, with some finding it difficult to co-operate. Children perhaps required a more sophisticated level of socio-emotional skills to manage the autonomy provided. Future teaching could allocate pupils to groups/roles in advance, based on teachers’ knowledge of pupils’ sociometric status (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1945), since some found it difficult to share roles. This is an important lesson pertaining to the latent prerequisites required of pupils to engage in autonomy-supportive activities and engage in PE (Green et al., Citation2021). Some schools may have strong class cohesion where pupils can work independently as teams, but others may benefit from prior focused learning around group work, for example, cooperation, listening skills.

Given the over-emphasis in research on CYP’s hedonia (Avedissian & Alayan, Citation2021), the researchers’ lessons sought to make connections between feeling good and functioning well. While pupils demonstrated an understanding of the importance of setting goals in life and having a broader purpose when thinking of influential others, many had difficulty identifying short-term school-related goals. This could be due to a lack of meta-cognitive skill required to engage in goal-setting common among Primary-aged pupils (Sides & Cuevas 2020) yet may also be explained by the context-specific goals pupils were asked to think about.

Children struggle to relate to goals focused on schoolwork if this is not part of existing practice. In accordance with PYD (Romer & Hansen, Citation2021), teaching children about what eudaimonic wellbeing is in isolation (finding purpose in one’s life, setting goals and engaging in meaningful activities) does not actively foster eudaimonia. CYP need to understand the ideas of eudaimonia and be explicitly shown how to engage with them in their own lives. This latter point, the need to explicitly demonstrate to children the steps of goal-setting, is something that needed to be included in the second lesson that could have drawn on graduated response (Department for Education, Citation2014) and Goal-Based Outcomes (GBOs; Law & Jacob, Citation2015). A PowerPoint slide exemplifying to pupils (using animated visuals) the process of goal setting, starting with (1) thinking with teachers/mentors at school first about what they do not want (for example, to be unable to count to 20; starting arguments with friends) to establish a goal, (2) evaluating where they are currently with that goal (on a scale of 0–10), and (3) planning what they can do to make progress. EPs/EMHPs could feed into this, supporting YP as mentors, checking in on their progress at regular intervals and prompting self-evaluation (tracking their progress from 0 to 10).

Meeting CYP’s need to feel competent (as per SDT) requires teachers to pay attention to the multitude of ways CYP might derive this sense of competence at school; thinking beyond narrow ‘academic’ roles imposed by society (Bonell et al., Citation2019). The authors recommend asking pupils to set multiple goals that are not exclusively work-related. Pupils could be encouraged, in conversation with teachers, to set three goals, for example, one in literacy, in Maths, and another related to what feeling good at school means to them. The goal-setting process could be modelled by staff at a whole-school level, exposing pupils to concepts such as motivation and autonomy, central to PE.

A final challenge was that some children’s advice seemingly lacked depth, raising questions about the degree of learning taking place. The brevity of pupils’ advice may have been attributable to either literacy ability or perhaps (for Silver Birch) the higher-than-average proportion of pupils with EAL. However, this is complicated by research demonstrating children’s literacy abilities are strongly associated with their emotion knowledge (Beck et al., Citation2012; Voltmer & Salisch, Citation2017). Pupils with lower literacy competence may lack the emotional understanding required to give wellbeing advice. Consideration is thus needed of pupils’ literacy skills to make this activity accessible. In future teachers could ensure a balance of discussion-based learning with pupils thinking of advice together prior to breaking out into their teams, with scaffolded support provided for particular pupils while writing their advice. Most important is that pupils have a secure knowledge of how to take care of their wellbeing, therefore teachers could consolidate learning by presenting a comprehensive overview of self-care advice. This would additionally cover another statutory LO: pupils’ understanding ‘simple self-care techniques’.

Reflections on secondary school lessons

Adolescence is a complex time when it comes to emotions (Riediger & Klipker, Citation2014) with many young people experiencing difficulties talking openly about emotions, perhaps due to their perceived need for social validation (something pupils themselves noted in the Top Priorities task), also reflecting the SDT need for relatedness. Groupwork was used as a pedagogic tool to foster connection in the lessons. For most adolescents, working in groups with friends facilitated high engagement with the content; perhaps since pupils felt able to talk openly and candidly about wellbeing among those with whom they are at ease. For others, working with friends inhibited learning and was distracting. The researchers’ observations of pupils being easily distracted/not taking the activity seriously when working in groups were, however, different to Primary pupils, who had high engagement with the task but struggled to work collaboratively. Thought should thus be given to the allocation of pupils to groups. Notably though, many pupils valued being given a structured space to discuss wellbeing with friends; comparing this to times they informally tried (and failed) to have meaningful conversations outside the classroom. The opportunities cultivated in the lessons for pupils to share their ideas about wellbeing with peers may have met CYP’s need to feel connected.

To what extent do you feel it is or is not important to have lessons like this at school mental wellbeing?

10 out of 10? Five out of five? Out of whatever, I think it’s really important!

Why?

Because … I’m sure there’s a lot of people who … there are some friends I have that every time I ask them how they’re doing. They’re like, terrible, no … awful. And I’m just like, oh, what’s the matter? And they’re just like, it’s nothing. It’s fine.

I feel like they could benefit. Yeah. And there’s none of this in school. (Zubee and Sara, Age 15)

Some young people struggled to see beyond ‘objective’ or physical wellbeing, providing ideas that suggested their understanding of wellbeing equated to physical health. While the mental-physical health connection is an important separate Health Education LO, the focus of the lessons on psychological wellbeing was made explicit. Pupils seemingly found more holistic experiences of wellbeing challenging to comprehend. Moreover, conceptually some adolescents struggled to understand psychological wellbeing as constituting more than just feeling ‘happy’, suggesting the hyper-focus on hedonia by adults is filtered down to how CYP themselves understand their wellbeing.

The fact that many adolescents reduced their wellbeing to feeling ‘happy’ or not is troubling as it suggests CYP are unfamiliar with eudaimonic notions of what it means to feel good. Given high eudaimonia is significantly predictive of lower depression in adolescence (Kryza-Lacombe et al., Citation2019; Telzer et al., Citation2014), it is critical that CYP are taught about the importance of finding purpose and meaning in their lives. However, lessons were short and eudaimonia requires sustained, in-depth contemplation, given its focus on deeper questions of one’s engagement with personal goals, meaningful activities, and sense of purpose. This is where EPs/EMHPs could add value; helping CYP cultivate meaning in one-to-one work and reinforcing curricula through their services.

Like Primary pupils, adolescents also found it difficult to make connections between their schoolwork and wellbeing, with some making a clear delineation between working on achieving school goals and their MH.

I think they’re very important because it’s kind of showing you that like, your mental health is important, as well as your schoolwork, because you can’t just continuously do schoolwork and not focus on yourself as well. Because you can get to that point where you’re just doing work. And it’s, you forget that you need to like do other things as well as that. (Ash, Age 15)

This further illustrates the limited opportunities pupils are provided to feel competent at school; meaning school is seen as a force in opposition to CYP’s sense of wellbeing and feeling good. Ash’s description of doing ‘schoolwork’ as not focusing ‘on yourself’, and the disassociation described between learning as something separate from her wellbeing may reflect how CYP conceptualise what it means to be well at school. Educating CYP about eudaimonia could help them understand how school goals pursued might be an integral part of wellbeing as opposed to long-term goals being something separate to their sense of wellbeing,

For others, like Ava, the lessons laid clear foundations for them to contemplate themselves and begin to grasp the essence of eudaimonia.

It helps you get to know yourself? I think most people have actually taken this thing serious and they’ve actually … started to maybe feel like from the questions you’ve been asking about, like, how do you feel in school, maybe some people have actually gone home and thought about it, and maybe got some time to think about everything and how school is going for them or like how they’re feeling at school and the problems they have at home and everything, I think it … might have helped some people to think about who they really are and … what they can achieve and what they can’t … stuff like that? (Ava, Age 15)

Altogether, notions of eudaimonia were unfamiliar to adolescents and proved difficult for them to engage with. wellbeing Therapy (WBT) teaches eudaimonia in schools and has demonstrated efficacy in reducing adolescents’ MH difficulties, including anxiety and depression (Ruini et al., Citation2009). Using activities such as those used in WBT which stimulate ideas of finding meaning and purpose and providing space for CYP to contemplate their individual skills, abilities, and goals are of utmost importance if schools are to truly promote CYP’s wellbeing.

Realistically, activities whereby pupils applied their knowledge of wellbeing required more time; raising questions about the purpose of learning and how the ‘taught’ can become the ‘caught’ curriculum (Green et al., Citation2021). Can lesson activities be designed with the intention of incorporating pupils’ completed work at the whole-school level? Pupils could present advice to younger peers in an assembly. One strength of the researchers’ input was that pupils’ work was considered as having a life beyond the lessons. For example, pupils’ priorities posters were given to teachers to decide how and where to present them and the researchers amalgamated pupils’ priorities into lists presented to Senior Leadership. Allowing the learnt wellbeing principles to reverberate throughout the whole school through acknowledging pupils’ work and weaving their ideas into school policies or practices is to truly embed pupils’ wellbeing into school culture (Hoare at al., Citation2017). Thinking beyond the individual school-level, pupils’ work could be sustained through a ‘pen pal’ programme where schools share pupils’ ideas to inspire change across LAs (for example, sending Good Advice Boxes or letters to a friend to local schools, digitally or physically); providing further opportunities to meet CYP’s need for interpersonal connectedness.

Recommendations for practice

Notwithstanding the limitations noted of this being a multi-site case study conducted in only four schools, two recommendations can be made based on the authors’ experiences of developing and delivering wellbeing lessons. First, although teachers are significant custodians of children’s MH (Winship & MacDonald, Citation2018), the deployment of new EMHPs in schools, in addition to specialist EPs in LAs, presents opportunities for wellbeing lessons to be co-designed and delivered. Such partnerships would align with EPs/EMHPs job descriptions, as the EP remit is to nurture CYP’s wellbeing, and EMHPs are trained in psychoeducation. The PSHE Association (Citation2019) suggests schools should utilise such skilled ‘visitors’ to support teaching, yet historically less than 3% of staff in England’s schools utilised MH specialists, including EPs, to support teaching (Vostanis et al., Citation2013).

A decade later, schools are now acknowledged as critical ecosystems for the promotion of CYP’s wellbeing (Howarth et al., Citation2019); presenting new terrain for multi-professional working. EPs and EMHPs have an essential role in advancing the ‘caught’ curriculum beyond the ‘taught’ curriculum delivered by teachers (Green et al., Citation2021) which involves reinforcing the principles of PE at individual- and whole-school levels. Multi-agency partnerships face barriers of time, resources, and leadership, but are advocated internationally as the strongest and most efficient way of promoting wellbeing in schools (Department of Health & Department for Education, Citation2017; Langford et al., Citation2017).

Support from leadership at school- and LA-levels could enable this collaborative partnership, with Senior Mental Health/PSHE Leads in schools ensuring teachers and EPs/EMPHs have ring-fenced time for lesson planning, incentives for collaboration, and reinforcement of curriculum content at the whole-school level. Utilising EPs/EMHPs as co-teachers of wellbeing could alleviate teachers’ concerns about their own lack of psychoeducational expertise (Shelemy et al., Citation2019) whilst simultaneously addressing MH practitioners’ experiences of feeling ‘separate from’ the school communities they serve (Granrud et al., Citation2019). In this vein, Senior Mental Health Leaders would need to fully embrace EPs/EMHPs as integral members of school staff to foster interprofessional working and coordinate efforts to deliver wellbeing curricula that is fit for purpose (Symons, Citation2020).

Second, is the need for Health Curricula to support CYP to become ‘fully functioning persons’, providing them with understanding of what it means to live a fulfilled life and opportunities to engage in the process of being and becoming their selves (Rogers, Citation1963, p. 22). wellbeing curricula should be inclusive of eudaimonia and hedonia. Hedonic conceptions alone offer a limited education; equating wellbeing to ‘happiness’ or short-term feelings. Such messages do a disservice to CYP who require space, time and expertise to learn about how they might derive lasting fulfilment in life, develop their true Self, and flourish (Kristjánsson, Citation2017).

To conclude, England’s introduction of statutory wellbeing curricula has good intentions but requires refining to (1) incorporate the science of positive psychology, and (2) coordinate efforts of teachers and MH practitioners to enable the co-delivery of psychoeducation. Wellbeing curricula are no different than any other kind of curricula; they require both a tight script and skilled actors to connect with and alter the lives of their audience.

Ethics statement

This research was granted ethical approval by the ethics committee at the University of Cambridge, Faculty of Education.

Declarations of interest

none

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the teachers and children who devoted their time to participate in this project. We would also like to thank Dr Ros McLellan for her review of the first draft of this article, Cathy Murphy at Cambridgeshire PSHE Service, Ruth Platt, Katy Huett, and Adam Roberts for their review of the first draft of the lesson plans.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Dojo points are rewards earnt by pupils via a popular e-learning application in the UK

References

- Arguís-Rey, R. (2021). Positive education in practice. In L. Kern Margaret, & L. Wehmeyer Michael (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 49–74). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Aristotle. (1985). Nicomachean ethics. Hacket Publishing Company.

- Avedissian, T., & Alayan, N. (2021). Adolescent well-being: A concept analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(2), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12833

- Baxter, R. (2019). MindEd: A whole-school strategy on wellbeing—Tackling mental health stigma and promoting positive wellbeing in secondary schools. Education and Health, 37(2), 40–42. https://sheu.org.uk/sheux/EH/eh372rb.pdf

- Beck, L., Kumschick, I. R., Eid, M., & Klann Delius, G. (2012). Relationship between language competence and emotional competence in middle childhood. Emotion, 12(3), 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026320

- Benita, M. (2020). Freedom to feel: A self-determination theory account of emotion regulation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 14(11), e12563. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12563

- Bethune, A. (2018). Wellbeing in the primary classroom: A practical guide to teaching happiness. Bloomsbury Education.

- Biesta, G. (2009). Good Education in an age of measurement: On the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educational Assessment Evaluation and Accountability, 21, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9

- Boncquet, M., Soenens, B., Verschueren, K., Lavrijsen, J., Flamant, N., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2020). Killing two birds with one stone: The role of motivational resources in predicting changes in achievement and school well-being beyond intelligence. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 63, 101905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101905

- Bond, M., & Illustrated by R.W. Alley. (2019). Paddington’s Post: With real mail to open and enjoy!. Glasgow, Scotland: Harper Collins Children’s Books.

- Bonell, C., Humphrey, N., Fletcher, A., Moore, L., Anderson, R., & Campbell, R. (2014). Why schools should promote students’ health and wellbeing. Bmj, g3078. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3078

- Bonell, C., Blakemore, S.-J., Fletcher, A., & Patton, G. (2019). Role theory of schools and adolescent health. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 3(10), 742–748. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30183-X

- Brady, J., & Wilson, E. (2021). Teacher wellbeing in England: Teacher responses to school-level initiatives. Cambridge Journal of Education, 51(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2020.1775789

- Brighouse, H. (2006). On education. Routledge.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1945). The Measurement of Sociometric Status, Structure and Development. New York: Beacon House.

- Carter, A. (2015). Carter review of initial teacher training (ITT). Department for Education. DFE-00036-2015

- Casas, F., & González-Carrasco, M. (2021). Satisfaction with meaning in life: A metric with strong correlations to the hedonic and eudaimonic well-being of adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 14(5), 1781–1807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09826-z

- The Children’s Society. (2019). The good childhood report 2019.

- Clark, C., & Teravainen-Goff, A. (2018). Mental wellbeing, reading and writing. National Literacy Trust.

- Clarke, T. (2020). Children’s wellbeing and their academic achievement: The dangerous discourse of ‘trade-offs’ in education. Theory and Research in Education, 18(3), 263–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878520980197

- Clarke, T., & McLellan, R. (2022a, July 1). Understanding children’s and adolescents’ lived experiences of wellbeing at school in England using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Open Science Framework (OSF). https://osf.io/vazwq/?view_only=aef7ac2fabca4394959bdb3641fcfb6a

- Clarke, T., & McLellan, R. (2022b, April 26). Investigating the wellbeing-achievement ‘trade-off’ in England’s primary and secondary schools: Incompatible or underexplored? Open Science Framework (OSF). https://osf.io/zarge/?view_only=70d560fa292a45f992cc41f867f41d7d

- Coleman, J., Hale, D., & Layard, R. (2011). CEP discussion papers (no. dp1071; CEP discussion papers). Centre for Economic Performance, LSE. https://ideas.repec.org/p/cep/cepdps/dp1071.html

- Crow, F. (2008). Learning for well‐being: Personal, social and health education and a changing curriculum.Pastoral Care in Education, 26(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643940701848612

- Damasio, A. R. (2021). Feeling & knowing: Making minds conscious (First ed.). Pantheon Books.

- Daniels, H., Cole, M., & Wertsch, J. V. (2007). The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky. Cambridge University Press.

- Deboys, R., Holttum, S., & Wright, K. (2017). Processes of change in school-based art therapy with children: A systematic qualitative study. International Journal of Art Therapy, 22(3), 118–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2016.1262882

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Department for Education. (2014). Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years: Statutory guidance for organisations who work with and support children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities.

- Department for Education. (2018). Mental health and behaviour in schools. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/755135/Mental_health_and_behaviour_in_schools__.pdf

- Department for Education. (2021). Statutory guidance Physical health and mental wellbeing (Primary and secondary). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/relationships-education-relationships-and-sex-education-rse-and-health-education/physical-health-and-mental-wellbeing-primary-and-secondary

- Department of Health, & Department for Education. (2017). Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: A green paper. Cm 9525. Department of Health & Department for Education.

- Diener, E., Suh, E., Lucas, R., & Smith, H. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

- Dinisman, T., & Ben-Arieh, A. (2016). The characteristics of children’s subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 126(2), 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0921-x

- Diseth, Å., Danielsen, A. G., & Samdal, O. (2012). A path analysis of basic need support, self-efficacy, achievement goals, life satisfaction and academic achievement level among secondary school students. Educational Psychology, 32(3), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2012.657159

- Ellins, J., Singh, K., Al-Haboubi, M., Newbould, J., Hocking, L., Bousfield, J., McKenna, G., Fenton, S.-J., & Mays, N. (2021). Early evaluation of the children and young people’s mental health trailblazer programme (Interim Report). National Institute for Health Research.

- Ergas, O., Gilead, T., & Singh, N. C. (2022). . eds. Reimagining education: The international science and evidence based education assessment. UNESCO MGIEP

- Fischer, K. W., Shaver, P. R., & Carnochan, P. (1990). How Emotions Develop and How they Organise Development. Cognition & Emotion, 4(2), 81–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939008407142

- Formby, E., & Wolstenholme, C. (2012). ‘If there’s going to be a subject that you don’t have to do …’ Findings from a mapping study of PSHE education in English secondary schools. Pastoral Care in Education, 30(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2011.651227

- Gentzler, A. L., DeLong, K. L., Palmer, C. A., & Huta, V. (2021). Hedonic and eudaimonic motives to pursue well-being in three samples of youth. Motivation and Emotion, 45(3), 312–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-021-09882-6

- Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & Mason, L. (2005). Improving the writing performance, knowledge, and self-efficacy of struggling young writers: The effects of self-regulated strategy development. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30(2), 207–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2004.08.001

- Granrud, M. D., Anderzen-Carlsson, A., Bisholt, B., & Steffenak, A. K. M. (2019). Public health nurses’ perceptions of interprofessional collaboration related to adolescents’ mental health problems in secondary schools: A phenomenographic study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(15–16), 2899–2910. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14881

- Green, S., Leach, C., & Falecki, D . (2021). Approaches to positive education. In L. Kern Margaret, & L. Wehmeyer Michael (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 21–47). Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grosse, G., Streubel, B., Gunzenhauser, C., & Saalbach, H. (2021). Let’s Talk About Emotions: The Development of Children’s Emotion Vocabulary from 4 to 11 Years of Age. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 2(2), 150–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-021-00040-2

- Health Committee. (2014). Children’s and adolescents’ mental health and CAMHS. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201415/cmselect/cmhealth/342/34211.htm#a42

- Hoare, E., Bott, D., & Robinson, J. (2017). Learn it, Live it, Teach it, Embed it: Implementing a whole school approach to foster positive mental health and wellbeing through Positive Education. Intnl. J. Wellbeing, 7(3), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v7i3.645

- Howarth, E., Vainre, M., Humphrey, A., Lombardo, C., Hanafiah, A. N., Anderson, J. K., & Jones, P. B. (2019). Delphi study to identify key features of community-based child and adolescent mental health services in the East of England. BMJ Open, 9(6), e022936. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022936

- Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2011). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 837–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7

- Huta, V., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(6), 735–762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-009-9171-4

- Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 1(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x

- Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization, postmodernization and changing perceptions of risk. International Review of Sociology, 7(3), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.1997.9971250

- Kristjánsson, K. (2017). Recent work on flourishing as the AIM of education: A critical review. British Journal of Educational Studies, 65(1), 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2016.1182115

- Kryza-Lacombe, M., Tanzini, E., & O’Neill, S. (2019). Hedonic and eudaimonic motives: Associations with academic achievement and negative emotional states among urban college students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(5), 1323–1341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9994-y

- Langford, R., Bonell, C., Komro, K., Murphy, S., Magnus, D., Waters, E., Gibbs, L., & Campbell, R. (2017). The health promoting schools framework: Known unknowns and an agenda for future research. Health Education & Behavior, 44(3), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198116673800

- Law, D., & Jacob, J. (2015). Goals and goal-based outcomes (GBOs): Some useful information (Third ed.). CAMHs Press.

- Layard, R., & Dunn, J. (2009). A good childhood: Searching for values in a competitive age. Penguin Books.

- Lendrum, A., & Humphrey, N. (2012). The importance of studying the implementation of interventions in school settings. Oxford Review of Education, 38(5), 635–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2012.734800

- LePera, N. (2021). How to do the work: Recognize your patterns, heal from your past, and create your self (First ed.). Orion Spring.

- Lomas, T., Waters, L., Williams, P., Oades, L. G., & Kern, M. L (2020). Third wave positive psychology: Broadening towards complexity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(5), 660–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1805501

- Lordon, G., & McGuire, A. (2019). Healthy minds: Health outcomes (Evaluation Report and Executive Summary). Education Endowment Foundation and the London School of Economics.

- Lyonette, C., Atfield, G., Baldauf, B., & Owen, D. (2019). Research on the Educational Psychologist Workforce (Research Report). Department for Education.

- Marquez, J. (2021). Does school impact adolescents’ life satisfaction differently for students of different socio-economic status? A comparative study in 33 countries. Education Inquiry, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2021.1930345

- Music, G. (2017). Nurturing natures: Attachment and children's emotional, sociocultural and brain development (Second edition ed.). London: Routledge.

- Niemi, R., Kumpulainen, K., & Lipponen, L. (2015). Pupils as active participants: Diamond ranking as a tool to investigate pupils’ experiences of classroom practices. European Educational Research Journal, 14(2), 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904115571797

- Oades, L. G., Baker, L. M., Francis, J. J., & Taylor, J. A. (2021). Wellbeing literacy and positive education. In L. Kern Margaret, & L. Wehmeyer Michael (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 325–343). Palgrave Macmillan.

- OfSTED.(2005). Pupils’ satisfaction with their school.

- PSHE Association. (2018) . Handling complex issues safely in the PSHE education classroom.

- PSHE Association.(2019). Teacher guidance: teaching about mental health and emotional wellbeing.

- Rappleye, J., Komatsu, H., Uchida, Y., Krys, K., & Markus, H. (2019). ‘Better policies for better lives’?: Constructive critique of the OECD’s (mis)measure of student well-being. Journal of Education Policy, 2(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1576923

- Riediger, M., & Klipker, K. (2014). Emotion regulation in adolescence. In Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed., pp. 187–202). The Guilford Press.

- Rogers, C. R. (1963). The concept of the fully functioning person. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 1(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088567

- Romer, D., & Hansen, D. (2021). Positive youth development in education. In L. Kern Margaret, & L. Mehmeyer Michael (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 75–108). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ruini, C., Ottolini, F., Tomba, E., Belaise, C., Albieri, E., Visani, D., Offidani, E., Caffo, E., & Fava, G. A. (2009). School intervention for promoting psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40(4), 522–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.07.002

- Ruini, C., & Cesetti, G. (2019). Spotlight on eudaimonia and depression. A systematic review of the literature over the past 5 years. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12, 767–792. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S178255

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihaly, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

- Shelemy, L., Harvey, K., & Waite, P. (2019). Supporting students’ mental health in schools: What do teachers want and need? Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 24(1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2019.1582742

- Skills, O., Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services. (2010). No. 080266. Learning: Creative approaches that raise standards.

- Smith, R. (2008). The Long Slide to Happiness. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 42(3–4), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2008.00650.x

- Social Mobility & Child Poverty Commission. (2016). The Social Mobility Index. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/496103/Social_Mobility_Index.pdf

- Stavridou, A., Stergiopoulou, A., Panagouli, E., Mesiris, G., Thirios, A., Mougiakos, T., Troupis, T., Psaltopoulou, T., Tsolia, M., Sergentanis, T., & Tsitsika, A. (2020). Psychosocial consequences of COVID -19 in children, adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 74(11), 615–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13134

- Stirling, S., & Emry, H. (2016). A whole school framework for emotional well-being and mental health. National Children’s Bureau. https://www.ncb.org.uk/sites/default/files/uploads/files/NCB%20School%20Well%20Being%20Framework%20Leaders%20Resources_0.pdf

- Symons, R. (2020). Implementing the Green Paper: The Challenges of multi- disciplinary team collaboration. A review of the evidence. Education and Health, 38(1), 3–7. https://sheu.org.uk/sheux/EH/eh381rs.pdf

- Tamminen, N., Solin, P., Barry, M. M., Kannas, L., & Kettunen, T. (2022). Intersectoral partnerships and competencies for mental health promotion: A Delphi-based qualitative study in Finland. Health Promotion International, 37(1), daab096. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab096

- Telzer, E. H., Fuligni, A. J., Lieberman, M. D., & Galván, A. (2014). Neural sensitivity to eudaimonic and hedonic rewards differentially predict adolescent depressive symptoms over time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(18), 6600–6605. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1323014111

- Vizard, T., Sadler, K., Ford, T., Newlove-Delgado, T., McManus, S., Cartwright, C., Marcheselli, F., Davis, J., Williams, T., Leach, C., & Mandalia, D. (2021). Mental health of children and young people in England, 2020, wave 1 follow up to the 2017 survey. NHS Digital, Health and Social Care Information Centre.

- Voltmer, K., & von Salisch, M. (2017). Three meta-analyses of children's emotion knowledge and their school success. Learning and Individual Differences, 59, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.08.006

- Vostanis, P., Humphrey, N., Fitzgerald, N., Deighton, J., & Wolpert, M. (2013). How do schools promote emotional well‐being among their pupils? Findings from a national scoping survey of mental health provision in E nglish schools. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18(3), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00677.x

- Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 678–691. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.678

- Waters, L. (2021). Positive education pedagogy: Shifting teacher mindsets, practice, and language to make wellbeing visible in classrooms. In L. Kern Margaret, & L. Mehmeyer Michael (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 137–164). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wehmeyer, M. L., Cheon, S. H., Lee, Y., & Silver, M. (2021). Self-determination in positive education. In L. Kern Margaret, & L. Wehmeyer Michael (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 225–249). Palgrave Macmillan.

- White, J. (2016). Education, time-poverty and well-being. Theory and Research in Education, 14(2), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878516656567

- Winship, G., & MacDonald, S. G. (2018). The essential ingredients of counselling and psychotherapy in primary schools: On being a specialist mental health lead in schools. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Witten, H., Savahl, S., & Adams, S. (2019). Adolescent flourishing: A systematic review. Cogent Psychology, 6(1), 1640341. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1640341

- Young, M., & Muller, J. (2013). On the powers of powerful knowledge. Rev Educ, 1(3), 229–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3017