Abstract

The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior (IPTS) posits that suicide stems from a motivation to die by suicide, emanating from perceived-burdensomeness and failed belongingness, and a capacity to kill oneself. We propose a bridge between IPTS and dissociation theory/research via a recent reformulation of Melanie Klein’s notion of the depressive position, as comprised of three elements: Demeaning affect, compensatory affect-regulatory maneuvers, and mental representation of self-as-deficient and others as judgmental/punitive and at times seductive. This position is formed in childhood, proceeds to adulthood, and is projected into the future with the hope of finding respite from criticism. This hope is then thwarted by the sufferer’s interpersonal action leading to interpersonal strife. We posit that, in the Basic Level, a trauma-based, dissociative structure is formed, whereby the reformulated depressive position disengages from benign and benevolent mental processes, in turn creating interpersonal havoc. In the Advanced Level, dissociative mechanisms are utilized to assist the now depressed-suicidal position to succeed in its mission: Killing the self. A chilling case illustration of this pattern is presented and discussed. Clinically, we recommend a routine measurement of both dissociation and suicide risk, and appraisal of the psychodynamic connecting dissociation and suicidality.

The purpose of this article is to propose a conceptualization that ties together three bodies of literature: The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS [Joiner, Citation2005; Van Orden et al., Citation2010]), dissociation theory and research, and psychoanalytic object-relations theory, with a particular focus on social-cognitive reformulations of this theory. Guiding this integrative framework is a case illustration of an adult psychotherapy patient attempting a serious, near-lethal suicide attempt. The patient, treated by the first author (GS), is described below, followed by the proposed theoretical viewpoint.

1. ‘Nirity’: a case illustrationFootnote1,Footnote2

‘I would like to hug Nirity of twenty-one years ago and ten years ago’. This is how Nirit’s suicide letter starts. It continues as follows: ‘Unfortunately, Niriti is 49 years old (in two days, if I live that long) and she is exactly at the same place she was then, with the very same regrets, insights, anguish, and self-reproach, What a waste of life. Perhaps, if I wasn’t a physician. Perhaps if my mother would really love me. Or if I had not married an emotionally crippled thief’.

The letter then continues extensively. Twenty-one pages of sorrow, reproach for self-and-others, poignant reflections of life, expression of love for her children, guidelines to close friends as to what to do with her property, and how to take care of her children after she kills herself. All of this is juxtaposed against unbelievably witty utterances completely in synchrony with the pertinent political period (e.g., to her younger son: ‘Always vote Meretz [a left-wing party, GS] and never to Bibi! [Binyamin Netanyahu, the right-wing prime minister of Israel]’). The same wit, sense-of-humor, and sparkling intelligence that has made her an adored star among her peer physicians, a role model for her residents, and a much-feared threat among her supervisors.

Nirit did not kill herself, albeit not for lack of trying. During the weekend where she spent time alone in her house, intermittently writing her suicide letter, watching TV, and texting with family members, she also tried several times to hang herself. When this did not work, she tried swallowing a wide array of pills. For an experienced physician to not complete the task of ending a human life is noteworthy. But something within her – or someone – stubbornly kept her alive, and we will get to know that someone later in this article. Eventually, Nirit texted a family member that she is about to die by suicide. The text was immediately circulated around to other family members, who rushed to her house and stormed in, finding her half-conscious and taking her to a general hospital on the other side of the country, to protect her confidentiality. There, after a very brief hospitalization and medical stabilization, Nirit was discharged to the care of her family members. Two weeks later, she was at my (GS) office, examining me suspiciously while at the same time making me laugh using her stand-up-comedian-like quips.

We therapists all have a certain patient – if we are lucky more than one but never numerous – the encounter with whom is going to transform our lives forever. I am one of those fortunate therapists, and Nirit is one of those ‘transformational objects’ (Bollas, Citation1979), changing the way I think and feel about my creed and life. The change continues. Nirit has been in therapy with me for the past 4 years now, and counting. During which time, a lot has happened, enabling me to learn a great deal about the potentially tragic fate of physicians, both worldwide and especially in Israel, particularly the most conscientious and successful ones (Shahar, Citation2021a). But Nirit also introduced me to something very unique about suicide attempts, and arguably suicide death: The potential, always formidable, presence of dissociation in the unfolding of this horrendous undertaking. This is what we – the three authors of this article – are attempting to unpack.

Nirit was a little child when her parents immigrated from the former Soviet Union to Israel. She was the eldest of two brothers and one sister. As immigrants, the parents were economically disadvantaged, managing to make do but always with huge efforts, and always in the face of the kind of discrimination directed against ‘Russians’. The family was close-knit, and Nirit was viewed, from early childhood, as a rising star, both intellectually and physically. Her appearance was adorable, her tenacity fierce, and her intellectual powers highly apparent. She excelled in everything she did, in and out of school. While exhibiting a passion for literature and creative writing, Nirit ultimately focused on biology and the life sciences, with the aim of becoming a physician.

Despite these favorable descriptions made by Nirit of her childhood, she also alluded – hesitantly at first but gradually more forcefully – to very tumultuous relationships between her and her parents. The latter’s parental style was authoritarian, clashing with Nirit’s independence and reactance. This has led to countless quarrels, during which Nirit described instances that could only be defined as consistent with emotional and physical maltreatment. As is frequently the case, these altercations co-existed with the admiration and care Nirit continued to receive from her parents, leaving her (also quite customarily) confused, often feeling aggrieved and downright betrayed. Her recollections of these childhood incidents suggest that it was then that the seeds of depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms were planted.

As a teenager and then a young woman, Nirit was considered very attractive, and she was intensely sought out by young men. Nevertheless, she was quite selective in her romantic choices. After completing an illustrious mandatory army service, Nirit immediately applied to medical school and was accepted, thus embarking on the intensely long and hard journey of becoming an Israeli physician. Overall, things went very well for her. She excelled in medical school and was accepted into a very competitive residency, fell in love with a man her age and got married, had two adorable children, and – further down the road – applied and was admitted to a top-notch clinical and research fellowship in Europe. It was during the fellowship that her marital relationships went sour. She got divorced, completed the fellowship (again, with distinction), and went back to work at her ‘Alma Mater’ hospital in Israel. In this hospital, which she considered as ‘her home and second family’, she quickly rose within the ranks to become the head of an innovative medical unit treating high-risk patients.

It was then, at the peak of her career, that her mental health began to deteriorate. The clear triggers were work-related: Agreements made with the hospital for personnel and resources were not fulfilled, propelling Nirit to feel betrayed by her ‘second family’, as she had been by the original one. Worse for Nirit was her increasingly growing conviction that the medical services that she and her team are providing are actually substandard, and that she is in fact responsible for several patients’ fatalities. Repeated attempts made by her to force the hospital leadership to fulfill the agreements have failed, in turn increasing her distress and alienation. She experienced nightmares and a severe loss of appetite, and was completely burned out.

2. The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide

Suicide is, and has been, a severe global public health concern (World Health Organization, Citation2021). Over 700,000 people each year die by suicide (World Health Organization, Citation2021). Although all aspects of suicidality (suicidal thoughts, suicidal behaviors, death by suicide) are relatively rare, they are, in principle, preventable. As such, there is urgency in understanding factors that may explain suicide; dissociation may be one such factor, facilitating process, or condition that enables lethal suicide attempts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2022; Orbach, Citation1994).

Theories in the late 70s interlaced psychopathology and social processes (e.g., Abramson et al., Citation1978; Brown et al., Citation2012) presenting a heavily interpersonal lens into understanding why people suffer and why they die by suicide. The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS) further refined this view by presenting the first ideation-to-action theory, interacting with four essential constructs: thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness; a sense of hopelessness towards changes regarding the two prior factors; and capacity for suicide (Joiner, Citation2005; Van Orden et al., Citation2010).

The first three constructs address suicidal desire (i.e., suicidal ideation). Thwarted belongingness encompasses the internal perception of societal detachment and its correlates (e.g., isolation; loneliness). Perceived burdensomeness includes the belief that others would benefit from one’s death. Hopelessness about the first two facets of IPTS creates a sense of despondency (cf. helplessness) and a worldview that one’s life is a series of fatalistic failures (cf. negative expectancy (Abramson et al., Citation1989; Beck, Citation1967)). Finally, an important contribution of IPTS was the distinction between those who contemplate suicide compared to those who enact it; the theory suggests there are biological (i.e., genetic) and experiential (i.e., habituation) differences (Joiner, Citation2005). Accordingly, when a desire to die is combined with capacity (i.e., fearlessness towards death and dying; considerable tolerance for physical pain; and an applied and accessible knowledge surrounding the prepared method [e.g., firearm familiarity; Joiner, Citation2005; Klonsky & May, 2015], the theory predicts a lethal or near-lethal suicide attempt (see Van Orden et al., Citation2010 for a full review)).

2.1. IPTS in Nirit’s case

Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness were very prominent in Nirit’s suicide attempt. With those friends and family members she actually met, Nirit refrained from revealing her turmoil. As a consequence, she was incredibly lonely when she reached that weekend. Perceived burdensomeness was apparent in her conviction that she was providing substandard medical services, in turn convincing her that her patients were better off if she were dead. The logic proceeded as follow: If she is dead, her hospital will have to shut down the unit. When this happens, her patients will be referred to a hospital elsewhere in Israel, where physicians and patients enjoy safer working conditions not supplied by her own hospital. In hindsight, Nirit felt that she was better off either leaving the hospital and moving to another, or renouncing her medical career altogether. However, Nirit maintained that these two alternatives were highly unfeasible at the time because ‘you don’t leave a family’ and ‘I couldn’t fathom myself not being a doctor’.

3. Dissociative processes in suicidality

Dissociation includes a constellation of clinical presentations, evoking some empirical and clinical controversy (e.g., Dalenberg et al., Citation2012; Lynn et al., Citation2014). Historical definitions of dissociation range, such as defining it as a lack of integration of two or more mental processes or defining it as a separation between the mind and the body (Calati et al., Citation2017; Cardeña, Citation1994; Orbach, Citation1994). The DSM-5 defines dissociation as a combination of the above: ‘disruption of and/or discontinuity in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behavior’ (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). Clinically, it presents as a spectrum of severity including symptoms of depersonalization (i.e., self-detachment and/or significant alterations to the sense of self and/or identity), derealization (i.e., loss of perception of one’s surroundings as real), and amnesia (i.e., inability to recall memory; Mitra & Jain, Citation2023; Rabasco & Andover, Citation2020; Rossi et al., Citation2019).

Current research has divided dissociative symptoms into two predominant domains: compartmentalization and detachment (Holmes et al., Citation2005; Rabasco & Andover, Citation2020; Rossi et al., Citation2019). Compartmentalization (i.e., dissociative amnesia and conversion disorders) is characterized by an inability to maintain cognitive agency and voluntary motor control (Holmes et al., Citation2005; Rabasco & Andover, Citation2020; Rossi et al., Citation2019). Detachment (i.e., depersonalization and derealization) is characterized by a transmutation of the consciousness, or an ‘alienation’ of the self, others, or the world. Self-detachment can manifest as a blunting of emotion (e.g., flat affect), alteration of bodily sensations (e.g., numbing or out-of-body experiences), or the loss of tangibility of one’s environment (e.g., dreamlike states; Holmes et al., Citation2005; Rabasco & Andover, Citation2020; Rossi et al., Citation2019). Detachment has been reported across a variety of mental states (e.g., under the influence of illicit substances, during states of fatigue and sleepiness, and during the occurrence of trauma) and holds clinical relevance as a diagnostic subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022).

There is further evidence suggesting dissociative detachment may be transdiagnostic, relevant in a host of other types of psychopathology (e.g., substance abuse, borderline personality disorder, eating disorders, and depression (Lyssenko et al., Citation2018; Scalabrini et al., Citation2017; Soffer-Dudek, Citation2014)). Each of the aforementioned disorders shares a heightened risk for another, particularly grave outcome: suicide (Andover et al., Citation2005; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2022; Shahnaz & Klonsky, Citation2021; Smith et al., Citation2018). Thus, dissociative detachment may, additionally, be particularly informative when understanding suicide risk.

Orbach (Citation1994) hypothesized that suicide attempts, especially distinctly violent ones, may be marked by dissociation presenting as an insensitivity to physical pain and bodily indifference (Orbach, Citation1994). When differentiating between the two modes of dissociation (i.e., compartmentalization and detachment), detachment through depersonalization and derealization most aligns with Orbach’s theory and may be the more likely to impart suicide risk (Caulfield et al., Citation2022; Holmes et al., Citation2005). Joiner’s (Citation2005) interpersonal theory of suicide (IPTS) – which, though it did not emphasize dissociation, nonetheless owes an intellectual debt to Orbach (Citation1994)—proposed one aspect of capacity, i.e., a heightened ability to inflict lethal injury, helps explain critical differentiations between those who contemplate and those who enact lethal suicide attempts (Joiner, Citation2005; Van Orden et al., Citation2010). An integration of Orbach’s (Citation1994) theory and IPTS would suggest that dissociation may increase the threshold for pain, decrease bodily sacredness, and increase a fearlessness towards death. Additionally, Joiner and colleagues suggest that diminished eye blink rate – an indication of fearlessness – may serve as a non-specific biobehavioral marker of imminent suicidality (Duffy et al., Citation2022; Joiner et al., Citation2016; Rubin et al., Citation2017). This marker may be one observable manifestation of dissociation.

Indeed, some research supports such claims: higher self-reported dissociative experiences associate with painful and lethal methods of suicide attempts (e.g., stabbing, falling, and hanging compared to drug overdose; Fakhry, Citation2015). Furthermore, in a meta-analysis conducted by Calati et al. (Citation2017), dissociative symptoms or disorders remained a transdiagnostic risk factor for lifetime history of suicide attempts in psychiatric patients (Calati et al., Citation2017). Five of the studies in that meta-analysis specifically compared symptoms of dissociation, independent of a disorder, using the Dissociative Experiences Scale (Bernstein & Putnam, Citation1986), and found high scores differentiated between suicide-attempting and non-suicide-attempting psychiatric patients (Hedges’ g = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.32–0.72; Calati et al., Citation2017).

When experimentally assessing relationships between dissociation, pain tolerance, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts, respectively, dissociation and suicidal ideation, but not pain tolerance, were significantly cross-sectionally associated with an increased number of past suicide attempts (Rabasco & Andover, Citation2020). The three-way interaction of dissociation, physiological pain tolerance, and suicidal ideation was significantly related to an increased number of past suicide attempts such that those high in suicidal ideation and dissociation, but low pain tolerance, had more attempts (Rabasco & Andover, Citation2020). Pachkowski et al. (Citation2021) examined two samples and found that dissociation cross-sectionally differentiated individuals with a history of suicide attempts from those with ideation alone (d = 0.28; d = 0.46; ps = 0.01) in both samples, and pain tolerance did not explain the association (see Study 2; importantly, associations diminished when including clinical covariates) (Pachkowski et al., Citation2021). Conversely, among clinical samples of patients with borderline personality disorder, researchers have found a relationship between dissociation and pain tolerance (Bekrater-Bodmann et al., Citation2015; Ludäscher et al., Citation2007). Finally, Levinger et al. (Citation2015) found that adolescent inpatients with suicide attempts reported higher levels of mental pain, in combination with a lower tolerance for the accompanying symptoms, in conjunction with a greater sense of physical dissociation, compared to non-suicidal adolescent inpatients and nonclinical participants (Levinger et al., Citation2015). Taken together, these findings may suggest that mental pain and physical dissociation (e.g., out-of-body experiences) relate to suicide risk, while mental dissociation (e.g., self-detachment) may affect the relationship between physical pain tolerance and suicide risk. Further research is needed to examine the role of dissociation in the interplay between it, pain tolerance, and suicide attempts.

Caulfield et al. (Citation2022) also found significant cross-sectional associations between lifetime dissociation and past year suicidal ideation, and past suicide attempts (Caulfield et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, symptoms of dissociation, particularly derealization and depersonalization, increased a participant’s likelihood of selecting suicide in a virtual reality paradigm (though statistical significance dissipated when controlling for other correlated factors; Caulfield et al., Citation2022). Thus, there appears to be some connection between dissociation, suicide attempts, and capacity. Nevertheless, research has yet to investigate if dissociation impacts one’s psychological and physical proximity to pain and methods, other facets of capacity that may impact the lethality of a suicide attempt (Rogers et al., Citation2019).

Dissociation was the strongest correlate of suicide attempts among Israeli high schoolers, more so than experiences of trauma including emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect (Zoroglu et al., Citation2003). Findings here have been clinically replicated, as those with dissociative subtypes of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD-D) have reported significantly more current suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts; moreover, symptoms of depression in the past month and lifetime suicide attempts significantly predicted PTSD-D (Mergler et al., Citation2017). Longitudinally, severe dissociation was predictive of future suicide attempts among those with borderline personality disorder (BPD; n = 290) 16 years later, albeit the increase in risk was marginal (Wedig et al., Citation2012). Therefore, dissociation appears to be relevant in suicide risk across a variety of clinical diagnoses (e.g., PTSD-D and BPD, though see conflicting evidence: Lieberman et al., Citation2023).

3.1. Dissociation and suicidal ideation

More recent efforts, though preliminary, have begun to assess and parse through the role that dissociation plays in suicidal ideation (see Caulfield et al., Citation2022; Mergler et al., Citation2017; Pachkowski et al., Citation2021; Rabasco & Andover, Citation2020). As noted above, this work is predominately cross-sectional (see Caulfield et al., Citation2022; Mergler et al., Citation2017; Pachkowski et al., Citation2021; Rabasco & Andover, Citation2020); nevertheless, dissociation differentiated between those with prior suicide attempts and those with lifetime suicidal ideation (Pachkowski et al., Citation2021). Therefore, though research on causation is warranted, there may exist an important distinction between dissociation’s relationship to suicidal ideation vs. to suicide attempts.

Thoughts and behaviors surrounding suicide can cause significant distress and impairment in their own right and warrant clinical attention and intervention (Jobes & Joiner, Citation2019). To our knowledge, there is a dearth of research to date studying the theoretical relationships (i.e., see the IPTS above) between dissociation and the interpersonal facets of suicidal ideation. One study, among a clinical sample of bulimia nervosa participants, found that dissociation did not share zero-order correlations with suicidal ideation, but did with self-hatred (i.e., a proxy of perceived burdensomeness), a proxy of thwarted belongingness, and capability (Lieberman et al., Citation2023). Therefore, additional research is warranted to determine if depersonalization and derealization relate to thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Theoretically, depersonalization results in blunted emotions, and can display externally as a flat affect, which may impede an individual’s ability to socially connect to others (Holmes et al., Citation2005). Additionally, depersonalization may result in feeling disconnected from one’s community, described as if one was separated by a glass wall (Holmes et al., Citation2005). Derealization, on the other hand, can alter one’s perception into a dreamlike state, with full awareness of this environmental alteration, furthering experiences of social disconnection (Holmes et al., Citation2005). This dreamlike state may further disrupt perceptions of time and impact ability to complete tasks, relevant to perceived burdensomeness. This imprisonment of the mind may drive a desire to die as an unfortunate method to awaken from the dream state that is dissociation. Those who experience dissociative states, in both episodic and continued intervals, may find it particularly challenging to recollect uninterrupted periods of time (e.g., memories) without states of distress. This may create tension within the self between a desire towards life and a calling to death as a means to escape. This simultaneous process of planning life while planning death has been noted in past accounts of lethal suicide attempts (Jamison, Citation1995; Joiner, Citation2005); thus, further understanding dissociation’s role in suicidal ideation may be a critical direction forward in understanding the suicidal mind.

Given that dissociation is defined by disruptions in memory, bodily connection, and integration of consciousness, it follows that dissociative symptoms should result in cognitive dysfunction. Indeed, a review of the literature suggests that dissociation and cognitive dysfunction may share psychological mechanisms and their neurobiological bases, resulting in dissociation impacting cognitive performance relating to attention, executive functioning, memory, and social cognition (McKinnon et al., Citation2016). Therefore, there may be neurobiological similarities between dissociation and suicide (Comparelli et al., Citation2022; Fernández-Sevillano et al., Citation2021). However, it is cautioned against generalizing neurobiological findings in suicide risk across all clinical diagnoses, as stronger associations between executive dysfunction and suicidality have been found in depressive disorders more so than in bipolar or psychotic disorder samples (Bredemeier & Miller, Citation2015). Nevertheless, these preliminary cognitive associations appear to mirror theoretical and empirical support towards associations between detachment dissociation and suicide (rather than compartmentalization [e.g., memory] and suicide, though see [McKinnon et al., Citation2016]).

3.2. Clinical implications

Taken together, dissociative tendencies, particularly detachment, may aid in the facilitation of suicide. Work to date has linked dissociation to suicide attempts; clients are safest when embracing their bodily awareness and experiencing life with lethal means secured far away (Rogers et al., Citation2019). Dissociation interferes with many components of this safety (e.g., bodily and life awareness, sacredness of self) and while simultaneously impacting capability (e.g., fearlessness about death and pain), this hinges the safety of a higher suicide risk client upon securing lethal methods. Moreover, dissociation has been associated with poorer therapeutic outcomes, nonadherence, and dropout rates in a variety of clinical diagnoses (Bae et al., Citation2015; Kleindienst et al., Citation2011; Rufer et al., Citation2005). On the other hand, a review assessing treatment outcomes for dissociative disorders has shown neighboring reductions in suicidal ideation and attempts (Brand et al., Citation2009; Brand & Stadnik, Citation2013).

As dissociation has been associated with more violent suicide attempts (Fakhry, Citation2015; Orbach, Citation1994), and global suicide deaths oftentimes involve methods that are more violent (e.g., self-poisoning through pesticides, ligature, and firearms [World Health Organization, Citation2021]), accurate assessment of dissociation symptoms may help inform treatment protocols. The Brief Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-B) is an 8-item measure which assesses an individual’s frequency of dissociation within the past week, where higher sum scores indicate a greater severity of dissociative experiences (C. Dalenberg & Carlson, Citation2010). This scale has shown strong 10-week test–retest reliability and good validity (Kira et al., Citation2022). Incorporating routine measurement of dissociation, in conjunction with gold standard measurements of suicide risk (see Batterham et al., Citation2015; Gutierrez et al., Citation2019), may help clinicians assess for heightened suicide attempt risk.

3.3. Dissociative experiences in Nirit’s suicide attempt

Nirit remembers talking to herself loudly during the entire weekend proceeding her suicide attempt. She remembers a very stormy dialogue between two self-aspects. The first she called The Terminator, which pushed her repeatedly to kill herself, ridiculing her in the face of her ‘failures’ to do so. The second was ‘Niriti’, a cute little girl ‘who did not want to die’. As therapy progressed, and with the occurrence of two additional dissociative episodes getting Nirit closer to suicide attempts, it became clear that each self-aspect had a different role in Nirit’s inner world. The Terminator was in charge of summoning the courage to cross daunting challenges, including the maltreatment she had suffered during her childhood (i.e., courage which could have manifested as a reduction in blink rate, a sign of imminent suicide risk (Duffy et al., Citation2022; Rubin et al., Citation2017)). Niriti, on the other hand, was in charge of relationships: With romantic partners, her children, and – of course – with me in therapy: An affectionate, caring but concurrently highly sensitive and vulnerable – protagonist that represents what Blatt (Blatt, Citation2004; Blatt, Citation2008) would label as anaclitic-dependent needs: The need to be nurtured, protected, and supported, so that she could stay alive. Upon discovering and delineating the two self-aspects, Nirit was particularly alarmed – not by their presence – but by the fact that they are so disconnected in their daily experience. Which brings us to Melanie Klein’s notion of positions, and particularly the depressive-suicidal one.

4. The Reformulated Object Relations Theory (RORT) and the reformulated suicidal-depressive position

A central tenet of this article is that the underlying dissociative processes are relatively stable, i.e., structural, representations of self-and-others, characterized by a particular affective tone and specific ways to regulate such affect (i.e., defense mechanisms and coping strategies). The combination of mental representations, affect, and affect-regulation conforms to Melanie Klein’s (Citation1935) notion of positions (Thieberger, Citation1991). Over approximately two and a half decades of theoretical work Shahar and colleagues have attempted to reformulate psychoanalytic object-relations theory in general and Klein’s notion of positions in particular (Klein, Citation1928, Citation1935, Citation1940, Citation1945; Klein et al., Citation1993) with the aim of freeing these important intellectual and professional bodies of literature from what is often deemed an idiosyncratic, stifling jargon (e.g., ‘bad breast’) that is highly unappealing to thinkers both within and outside psychoanalysis (Shahar, Citation2004, Citation2006a, Citation2006b, Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2015a, Citation2016, Citation2021a, Citation2021b, Citation2023; Shahar, Cross, et al., Citation2004; Shahar et al., Citation2003; Shahar & Davidson, Citation2009; Shahar & Schiller, Citation2016). Another important aim of this theoretical work is to inform object-relations theory and the notion of Kleinian positions with extant, up-to-date findings from psychological and neuropsychological work focusing on emotions and the self. As repeatedly acknowledged, this theoretical work stands on the shoulders of earlier pioneers integrating psychoanalysis and empirical research (Blatt, Citation2004; Blatt, Citation1974; Fonagy, Citation1995; Kemberg et al., Citation2008; Westen, Citation1991, Citation1998). The products of this extensive theoretical work are the Reformulated Object-relations Theory (RORT) and the reformulated depressive (−suicidal) position. Both will be summarized succinctly below.

4.1. RORT and a new definition of positions

Shahar and Schiller (Citation2016) posit that the central content of the psychodynamic unconscious conforms to what Klein labeled as position: An amalgamation of – in her terms – object-relations, anxiety, and defense mechanisms. Readers of this journal hardly need to be taught about the two positions featuring in Klein’s theory, namely, the schizoid-paranoid position and the depressive position. The former, more ‘primitive’ (developmentally younger) position consists of a polarized experience of the world as split between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ segments, including self and others (‘objects’). The corresponding anxiety is that of annihilation of the good by the bad, and the principal defense mechanisms geared to regulate this very dramatic anxiety operate on the basis of a split, sharp divide, between good and bad. As long as good is kept away from bad, the former is relatively secure, although it is constantly threatened. With the accumulation of positive (pleasurable and nurturing) experiences, the more developmentally advanced, depressive position germinates. In this position, self and others are multifaceted, namely, they include both ‘good’ and ‘bad’ aspects. This paves the way to an entire plateau of hitherto unexperienced emotions such as sadness, guilt, regret, and ambivalence, and to a type of anxiety very different from the schizoid-paranoid one: An anxiety about one’s own ability to destroy the ‘good’ within the object via my own ‘bad’ (aggressive) aspects. Defense mechanisms utilized in this position are much more moderate, conforming to the descriptions of Sigmund and Anna Freud of ‘neurotic defenses’. Instead of erasing vast segments of experiences, such defenses obscure circumscribed experimental aspects, namely, impulses, thoughts, and emotions (Greenberg & Mitchell, Citation1983; Ogden, Citation1992). As elaborated on by Klein and her followers, positions are different than stages in that they co-exist within the same person at the same period of time, in turn accounting for rapid oscillation between primitive and advanced levels of personality organization and behavioral maturity.

Shahar and colleagues applauded numerous aspects of Klein’s notion of positions, including (1) its depiction of psychological development as characterized by increasing cognitive-affective complexity (see Blatt, Citation1995), (2) avoiding common fallacies committed by stage theories (e.g., such as Piaget’s and Freud’s) via emphasizing the co-existence positions, and (3) describing personality as a dynamic structure in which various components work in tandem. This latter strength is paramount, because it allies Klein’s notion of positions with similar theories, both within and outside psychoanalysis, that view personality as a dynamic (dis)equilibrium of numerous forces (Beck, Citation1996; Block, Citation2002; Horowitz, Citation1998; Kelly, Citation1955; Kernberg, Citation1984; Mischel & Shoda, Citation1995). On the other hand, Shahar and colleagues note two major flaws of Melanie Klein's theory: (1) the above-noted use of the idiosyncratic jargon and (2) Its seclusion of key findings from psychological and neuroscientific research. Both flaws are addressed by reformulating the notion of positions, and hence object-relations theory itself, using social-cognitive nomenclature, which is clear, empirically testable, and encourages integration between psychoanalysis and empirical science (Blatt et al., Citation1997; Bornstein, Citation2001; Westen, Citation1991, Citation1998).

Specifically, the following are several empirically supported principles that Shahar and colleagues incorporated into their reformulated version of object-relations theory (RORT) and, by extension, Kleinian positions:

Instead of a sole emphasis on anxiety as the affective ‘prime mover’ of personality, RORT emphasizes the importance of a nuanced perspective on emotions. Particularly, RORT acknowledges that numerous negative emotions may fuel the dynamic interplay between personality components, and that negative and positive affect – which are largely orthogonal – are likely to each independently impact personality.

Instead of embracing the idea of a thick ‘repressive line’ clearly separating unconscious and (sub)conscious material, RORT adopts research findings that attest to the continuous nature of consciousness: Material can go in and out of awareness depending on individuals’ goals and developmental tasks (for empirical support, see Erdelyi, Citation2006; Green et al., Citation2009; Sedikides & Green, Citation2009; Shahar, Citation2006a); for a similar theoretical view within psychoanalysis, see (Eagle, Citation2011; Stolorow et al., Citation1987). Perhaps, the biggest advantage of this modification is that it allows treating both defense mechanisms (hitherto considered ‘unconscious’) and coping strategy (previously considered ‘conscious’) as equal manifestation of ‘affect regulatory maneuvers’ (Shahar, Citation2021b, 2023).

Instead of focusing on past and present as the focal tenses impacting personality, RORT elevates the role of the future in the psyche. Specifically, drawing from both early (Sullivan, Citation1953) and recent (Summers, Citation2003) developments in psychoanalytic theory, as well as from voluminous research on the effect of future representations on human cognition, affect, and behavior (Amati & Shallice, Citation2007; Austin & Vancouver, Citation1996; Gilbert & Wilson, Citation2007; McDaniel & Einstein, Citation2007; Seligman et al., Citation2013), Shahar and colleagues highlighted the centrality of the future as ‘an object of desire’: People project themselves into the future in order to become what they think they might be and ought to be (Shahar, Citation2011).

Instead of the Kleinian tendency to focus mostly on intrapsychic processes (e.g., fantasy), Shahar and colleagues extract the only interpersonal aspect of Klein’s theory – projective identification. As is probably obvious to readers of this journal, projective-identification is a split-based, interpersonal defense mechanism whereby individuals force significant others in their lives to behave in a way that is consistent with segments of their personality which they (the initiators) unconsciously disown: I am full of hatred, thus I will force you – e.g., through a wide array of provocations – to behave in a hateful manner toward me. The Kleinian notion of projective identification is not only consistent with numerous other ideas within psychoanalysis (e.g., Joseph Sandler’s role responsiveness (Sandler, Citation1976), Karen Horney’s externalization and the vicious cycle (Horney, Citation1936)), but also with ideas propagated in cognitive, behavioral, and family-systems schools of psychopathology, according to which individuals, propelled by their personal characteristics, create the very social environment that lead to their distress (e.g., Coyne, Citation1976a, Citation1976b; Depue & Monroe, Citation1986; Hammen, Citation1991; Joiner, Citation1994, Citation2000; Shahar, Citation2006b).

Weaving it all together, we arrive at the following, reformulated definition of Melanie Klein’s position:

‘A position is an amalgamation of affect, its regulation, and schemas and scripts of self-in-relationships, with all augmenting each other and forming a distinct and coherent experience of the world. Positions are formed throughout childhood and adolescence and are maintained via interpersonal action. They are projected into the future, representing individuals’ hope and fears, and as such are guiding cognition, motivation, emotion, and behavior. Although all positions strive to be confirmed in the interpersonal arena, some positions, occupying a large space in the psyche, are likely to create a maladaptive social environment that culminates in psychopathology’.

(Shahar, Citation2023).

Building on Shahar (Citation2023), several aspects of this definition need further emphasis:

Affect, its regulation, and schemas and scripts are co-causative.

Positions enable a clear worldview: ‘This is what the world looks like, and I should act accordingly’.

All positions translate into action: people constantly shape social reality in accordance with their worldview. Wachtel titles this vector ‘cyclical psychodynamics’ (see, in particular, [Wachtel, Citation1994]).

All positions are projected into the future. Future representations are thus the pillar of the psyche.

Whereas Klein focused on two ‘super-’ positions, we posit that, in fact, there are likely to be many positions in the psyche. This is in line with other personality theories highlighting the role – and multiplicity – of various components of intertwined affect and cognition, such as Beck’s (Citation1996) modes (see also in Schema Therapy, Lazarus & Rafaeli, Citation2023), and sets, (Lynn et al., Citation2014, Citation2019) and this point is paramount for the understanding of dissociation. In addition to Melanie Klein’s positions, i.e., the schizoid-paranoid and depressive, one may imagine obsessive, somatic, grandiose-manic, playful, humorous, affiliative, and so on. We postulate that each of these positions includes all the elements described above. An important issue concerning personality organization and psychopathology is the extent to which the various positions occupying the psyche of each are interconnected. Arguably, the more positions a person has, and the stronger these positions are interconnected, the greater is a person’s sense of coherence, comprehensiveness, and completeness. Correspondingly, a high number of interconnected positions enable a person a greater repertoire of responses under threat.

In psychopathology, a small number ‘eclipse the others’, in that they occupy a disproportionally large segment of the psyche. When this happens, a concerted effort is made by the individuals to confirm these positions in the interpersonal arena, and this – in turn – is likely to lead to calamitous outcomes.

Each of these points will now be utilized to reformulate Klein’s depressive position.

4.2. The reformulated depressive position

Shahar’s reformulation of the depressive position (Citation2016, Citation2018, Citation2021b, Citation2023) rests firmly on decades of empirical research into the role of personality in unipolar depression. Such research was largely inspired by the theories and studies of Blatt (Citation1974, Citation1998, Citation2004) and Beck (Citation1996). One of the clear patterns emanating from this research is the centrality of self-criticism as a dimension of vulnerability to all types of unipolar depression, as well as to other, related psychopathologies (Shahar, Citation2015b; Werner et al., Citation2019). Self-criticism activates a host of emotions, including sadness, fear, anger, shame, and contempt (Whelton & Greenberg, Citation2005). Self-critics may regulate this pain through maladaptive defense mechanisms such as acting out, undoing, projection, devaluation, denial, isolation, and splitting, and turning against oneself and others (Besser & Priel, Citation2011), as well as more conscious, maladaptive coping strategies such as venting distress to others without attempting to solve the putative problem (Dunkley et al., Citation2003), and highly maladaptive motivational regulative endeavors, namely, attempting to suppress authentic interest in activities (Shahar et al., Citation2003). Some of these defense mechanisms – projection, turning against others, splitting – actually shed light on a very close link – also likely to be reciprocal – between self-criticism and representations of other people. Specifically, self-criticism is shown to be strongly associated with the perception of others as harsh, punitive, and judgmental (Mongrain, Citation1998). Finally, painful affect may feedback, increasing the intensity of self-criticism (Shahar, Blatt, et al., Citation2004; Shahar & Henrich, Citation2019).

Synthesizing such research and substituting it in the above, reformulated structure of Klein’s position, Shahar proposed that a reformulated depressive position includes (a) criticism-based affect; (b) regulatory processes that reinforce this affect; (c) schemas and scripts associated with self-criticism; (d) a time axis that considers past and present influences as well as projections of the self in the future; and (e) interpersonal actions, primarily externalizing self-criticism, which creates a vicious cycle (Shahar, Citation2018, Citation2021b). Allow us to explicate below.

4.2.1. Affect

The most dominant affect in the reformulated depressive position is neither sadness nor fear, but rather a demeaning, criticism-based affect. It consists of emotions such as anger, shame, guilt, contempt, disgust, disappointment, hatred, and envy. The overall affective tone is that of putting down (either self or other) and focusing on deficiencies. Nevertheless, alongside this type of affect, we propose that there also exists a positive one: hope. This hope emanates almost inevitably from the theme of criticism: ‘I am flawed, but I know why. If I correct my flaws, I will be ok’. As we explicate below, this form of hope turns out to be problematic.

4.2.2. Affect regulation

Demeaning, criticism-based affect is defended against using three clusters of affect-regulatory maneuvers: counteracting deficiency, downregulating authenticity, and maintaining hope through ‘prospection’, or compulsive purposefulness. Counteracting deficiency is experiencing oneself consciously, as well as behaving, as if one is actually flawless, in a manner consistent with the Kleinian notion of manic defenses (see also Barrett, Citation2006; Ogden, Citation1992; Winnicott, Citation1958). Downregulating authenticity pertains to one’s tendency to do what is right, instead of what one wishes to do. It is tantamount to an assault on spontaneity, the latter deemed by self-critics as a constant threat because it is so unpredictable. Preparedness, rather than spontaneity, is perceived as an ultimate life demand. Finally, Compulsive purposefulness is an affect-regulatory mechanism espoused in the service of hope: ‘In order to eradicate my flaws, I must constantly self-improve!’.

4.2.3. Schemas and scripts

Schemas/scripts of the self are characterized by self-criticism and schemas/scripts of others as punitive and judgmental (Mongrain, Citation1998). Note, however, that self and others are schematized and scripted in the psyche as acting upon each other (Shahar, Citation2004), what I have labeled previously as ‘agents in relationships’ (AIR; Shahar, Citation2010). The other conveys judgment and disappointment, and the self as actively attempting to shield against these punitive judgments and disappointment in two ways: appeasing the other and protesting against the other. Appeasement is done by way of what Klein calls ‘reparation’ (see [Thieberger, Citation1991]): a fantasy of re-constituting the other as good is accompanied by solicitous behavior. The self is trying ‘to be good’ so that the other deems the self as non-deficient. Protests come to the fore either when the self does not succeed in appeasing the other, or by way of a ‘preemptive strike’: for example, ‘Are you mad at me?’ The tone of this question is angry rather than inquisitive. It is ‘how dare you be mad at me when I am so good!’

In addition, there is a subtle experience of the other as seductive, in an evaluative – rather than erotic – sense: ‘If you only accomplish this or that, or be this or that, then I will cease judging you and will lovingly accept what you are’. Such a seduction is, of course, reciprocally related to the hope that we described earlier, which – also subtly – dwells within the person’s affective spectrum. This is highly consistent with the notion of the ‘exciting object’ coined by Ronald Fairbairn (Citation1944). The exciting object promises a bright future in which the self is accepted, thus summoning love (see, for instance, Celani, Citation1999) and is – we submit – useful to the understanding of the reformulated depressive position.

4.2.4. Time axis

The reformulated depressive position considers the relevance of the past, the present, and the future. The past produces a storage of autobiographical memories from which the person draws the experience of being wronged (maltreated) by the other, but also the possibility of being at least partly responsible to the wrongdoing because the person somehow offended the other (Ferenczi, Citation1988). Hence, ‘You have hurt me. Had I hurt you before?’

In the present, there are active exchanges – both internally and externally, between self and others that revolve around hurt, grievance, and wrongdoing: Someone is always hurting someone else. These schemas and scripts surface, but are also amalgamated, by the aforementioned regulatory maneuvers shifting blame from self to other and vice versa. Thus, ‘You are hurting me. Do I deserve it?’

Following Sullivan (Citation1953) and Summers (Citation2003), however, we are highlighting the role of the future. This is where both dread and hope lie. The self yearns for an experience of the accepting other, but dreads a scenario whereby, despite all efforts, the other will remain judgmental and punitive. The tragedy is that the self – via interpersonal action – actually solidifies this punitive judgement by evoking rejections, confrontations, and interpersonal loss.

4.2.5. Interpersonal action

Voluminous research demonstrates compellingly that self-critics create a maladaptive social environment comprising interpersonal life stress (rejections, confrontations, breakups) and a dearth of positive experiences and social support (for a review, see Shahar, Citation2015b). Filling this pattern with psychodynamic depth, Shahar argued that, propelled by the reformulated depressive position, individuals project into their future both their hope for an accepting other and their expectations for a judgmental and punitive one. Their actions, however, automated throughout the years, are more consistent with the latter than the former. In a manner consistent with Klein’s ‘projective identification’ and Sandler’s (Citation1976) ‘role responsiveness’, but also with CitationCoyne’s (Citation1976a, Citation1976b) and Joiner’s (Joiner, Citation1994, Citation2000) research on excessive reassurance-seeking, these individuals’ actions exert pressure on others to react negatively rather than with compassion, ultimately yielding the above-noted interpersonal stress and dearth of positive events and social support.

It should be noted here that the above reformulation of the depressive position not only enhances and upgrades Klein’s description but actually alters this description in fundamental ways. In fact, as Shahar has noted recently (Citation2021b, Citation2023), Klein was not at her best in describing unipolar depression as a clinical entity. She was much more astute in describing the more psychotic psychopathologies, to which ‘her’ paranoid-schizoid position conformed. In describing depression, she either quickly ‘regresses’ into describing paranoia and/or mania (Klein, Citation1935, p.158) or provide an ultra-benign, if not downright favorable, account. This favorable account emphasizes the capacity for integration of good and bad objects and the ability of reparation of the relationships – actual and internalized – with the good object (Thieberger, Citation1991). Integration and reparation both protect the ‘self’ (a term Klein did not use but that was introduced subsequently in object-relations theory) not only as a fundamentally worthy being but also as a historical-narrative being that rests on a relatively cohesive life story. This is probably why Ogden (Citation1992) proposed re-titling ‘the depressive position’ as ‘the historical position’ (Ogden, Citation1992). In a subsequent publication, we hope to elaborate more on the difference between a pathological, genuinely depressive, position, and a favorable, benevolent, ‘historical position’ that tallies with some of Klein’s accounts.

4.4. How does the reformulated depressive position spiral into suicidality?

An enormous mental pain is experienced by depressed individuals when they project their hoped-for self-with-other representations onto the future only to be met with interpersonal stress and a dearth of social support and positive events. The failure to ‘generate’ an accepting other erodes hope and introduces frustration and resultant agitation, and these affects further alienate others, thereby trapping the person in interpersonal turmoil. Others thus are either abandoning, leading to thwarted belongingness, or fiercely accusing, and as such begetting perceived burdensomeness: ‘My mere existence is an offense’. The person is left alone at the mercy of their inner world, which at this point is completely merciless. Because depression ‘locks the person’ into their inner world (depressive rumination), the encounter with this world becomes harsher and harsher. Depressed-suicidal patients in one of our practices (GS) regularly describe their suicidal ruminations as stormy. Often, the person has already burnt all interpersonal bridges and/or realizes that they are likely to invoke hurt in any interpersonal maneuver. The only way to stop the pain is to cease being aware, and the only way to secure this is to die (Baumeister, Citation1990). This state of affairs pertains to what Joiner and colleagues title acute suicidal risk (Rogers et al., Citation2019). Now the sufferer has a new goal, a new sense-of-meaning, a new way to salvage their self-image: They can capably enact death. This is incumbent on two conditions. The first is stealth: If people close to the sufferer knew that they were going to kill themselves, they would interrupt. This is why acute suicide risk may go under clinicians’ radar. The second is fear of death, which requires practice leading to what Joiner and colleagues term capacity. After sufficient practice has occurred, the sufferer is ready to stare death down (Van Orden et al., Citation2010).

4.5. What is the role of dissociation in the above-described descent into suicidality?

We posit that, for the reformulated depressive position to spiral into suicidality, it should not only ‘eclipse’ other available positions but must downright annihilate these positions. Put differently, dissociative mechanisms enable depressed individuals, when they sink into an acute suicide crisis (Rogers et al., Citation2019), to smoothly sail into the tragic faith without interference.

What would such an interference look like? Suicide research is replete with empirical evidence of the ambivalence sufferers are harboring between life and death, often till the very last minute (Joiner, Citation2005; Orbach, Citation1994; Steel, Citation2006). Police negotiation teams are aware of this ambivalence, and when they attempt to dissuade sufferers from jumping off roofs or bridges, they are aiming at this very ambivalence, or, more accurately, at the inner voices within the sufferer who do not wish to die by suicide (Briggs & Mellinger, Citation2015). In the terms advanced here, during acute suicide crisis, there is a mighty struggle between, on the one hand, the reformulated-depressive-position-turned-suicidal, and any other position that is ‘benign’, namely, incompatible with killing oneself. Benign positions are those which include soothing affect (e.g., serenity, curiosity), mature defenses and coping style (humor, sublimation), and representations of self-and-others which include even a modicum of compassion. For the reformulated-depressive-position-turned-suicidal to materialize itself, such benign positions must be moved out of the way.

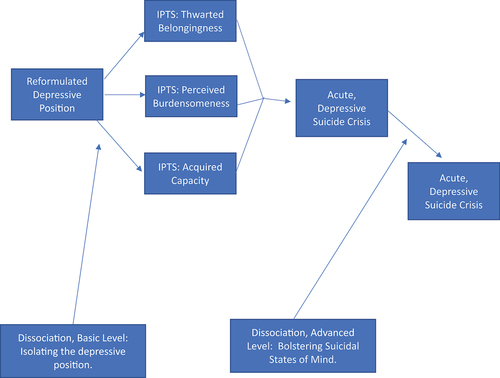

The way these benign positions are neutralized is depicted in . There are two levels in which dissociative mechanisms ‘keep at bay’ benign positions. On a more basic level, throughout development individuals learn to distrust benign positions: They experience them as signaling weakness and as potentially leading to mental injury. Consequently, such positions are either downplayed or downright ostracized (Strenger, Citation1998), whereas positions that promise, seductively and elusively, ‘to toughen up’ are elevated and are acted upon. Ultimately, an isolated depressive position is likely to propel the above-described IPTS-related factor leading to an acute suicidal crisis, in turn descending into suicidal behavior. On the more advanced level, within the acute suicide crisis itself, dissociative mechanisms operate online to banish thoughts, affect, and inner dialogues emanating from the benign positions, leaving the sufferers on their own with the reformulated-depressive-position-turned-suicidal, namely, with the perpetrator. Thus, this advanced level bolsters suicidal states of mind.

Figure 1. Proposed role of dissociation in the progression of the depressive position into suicidality.

Which leads us back to Nirit’s case, and to some speculations as to how she got to where she seriously tried to kill herself, and why she ultimately did not die.

5. Back to Nirit’s case: how dissociation led to suicide and how suicide was derailed

5.1. Basic-level Dissociation

Surviving a tumultuous childhood, Nirit learned to disengage from ‘Niriti’, a soft, mellow, arguably anaclitic-dependent position whereby the other is supportive and nurturing, the self is trusting and unguarded, affect is largely pleasant, fueled by affect-regulatory mechanisms aimed at increasing closeness, intimacy, and positive affect more generally (Fredrickson, Citation1998). Instead, ascended to dominance in her inner world was a position elevating performance, sharpness, reactance, and wit. Nirit learned that this position is her road to safety. To the extent that she is governed by it, others will adore and respect her: First her parents, then men in her life, commanders in the army, and ultimately the medical establishment. This dissociated personality structure, where two central positions – a soft, care-based one and a tough, go-getter one – are actively separated – worked well for Nirit for most of her life. Nirit has built what appeared to be a satisfying life on all fronts. Things got more complicated during her fellowship abroad, when her marriage went sour and she got divorced. Returning to Israel and investing all her energy in work, she again ascended to professional heights, only to discover that she is again betrayed, this time by ‘her second family’ – the very medical establishment that embraced her – by denying her the resources and means necessary for her to meet her professional and ethical standards. She was fiendishly trapped. On the one hand, not being the kind of physician she had to be, Nirit felt that she is a burden to her patients. In IPTS terms, perceived burdensomeness has set in. On the other hand, she kept her plight to herself, actively alienating herself from friends and colleagues, in turn propelling – in IPTS terms – thwarted belongingness. Both factors have increased the desire to kill by suicide, bringing her to the weekend where she actually tried to kill herself.

5.2. Advanced-Level Dissociation

The above description of the weekend during which Nirit has made numerous attempts to kill herself (by hanging, swallowing pills) is marred by dissociative elements. Intense depersonalization and de-realization were evident by a dream-like altered consciousness throughout the weekend, a spontaneous, uncontrollable inner-dialogue accompanied by sporadic, seemingly uncontrollable and at times incoherent journaling (including writing the suicide note). There were also out-of-body experiences, motor behaviors that were not fully voluntary (searching for a rope to hang herself) and an intense and massive dissociative amnesia, manifested by inability to recall a lot of what has happened during this weekend. Such dissociative amnesia also transpired in other instances occurring during therapy where Nirit was highly agitated, including one instance in which she was over the phone with GS for almost an hour, threatening to swallow sedatives and eventually dissuaded from doing so, but recalling nothing from this incident. Thus, active and intense cognitive processes conforming to both compartmentalization and detachment were highly operative during this prolonged suicide attempt.

The common denominator of both levels of dissociation, basic and advanced, is – we believe – childhood trauma. After decades of debate within the trauma and dissociation field, a consensus is gradually forming regarding the ability of massive trauma, particularly in childhood, to propel both a dissociative personality structure and dissociative, hypnotic-like mental processes. Interestingly, even scholars suspicious of the most severe and eccentric manifestations of dissociative disorders, such as Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), acknowledge the role of trauma in leading to a fragmented self-organization (van Heugten van der Kloet and Lynn, Citation2020). Similarly, even scholars who emphasize the possibility of dissimulation of dissociation agree that such a dissimulation is difficult to identify (Lynn et al., Citation2019). In Nirit’s case, there was no indication for DID, neither there was any indication of dissimulation. In fact, over time dissociative states became her greatest fear, the outcome she attempted to avoid most.

It was this very fear of dissociation that, we believe, ultimately saved her life. It is our contention that the dissociative personality structure (Basic Level) and dissociative processes (Advanced Level), aimed at keeping The Terminator and ‘Niriti’ at bay were simply not strong enough. ‘Niriti’, the anaclitic-relational position seeking nurturance, comfort, and support, withstood the vicious dissociative attacks, managed to voice herself in via WhatsApp texts to family members, in turn summoning her own evacuation. Fortunately, ‘Niriti’ saved Nirit.

Why was ‘Niriti’ able to survive these attacks? This, we believe, has to do with the presence of love and care in Nirit’s childhood, co-existing alongside the maltreatment and turmoil. It was this love, we believe, that instilled enough positive inner presences (‘good objects’) that enabled Nirit to not only refrain from killing herself but also to embark upon a very profound therapeutic process that allowed her to begin working through both levels of dissociation. This working through is indeed a work in progress, as is our current understanding of the psychodynamics of depression, dissociation, and suicide – a frustration we seemed bound to bear for the foreseeable future. So, we will have to stop here and bear the frustration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. In Hebrew, when the letter ‘y’ is added to a first name (e.g., ‘Golany’), it conveys affection and care by the speaker toward the person addressed. A possible British/American equivalent would be ‘Nirit-dear’.

2. The case description is distorted demographically but faithful clinically. The patient has read and approved this description, and consented to its publication.

References

- Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96(2), 358–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.358

- Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E., & Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87(1), 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.87.1.49

- Amati, D. & Shallice, T. (2007). On the emergence of modern humans. Cognition, 103(3), 358–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COGNITION.2006.04.002

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Andover, M. S., Pepper, C. M., Ryabchenko, K. A., Orrico, E. G., & Gibb, B. E. (2005). Self-mutilation and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and borderline personality disorder. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35(5), 581–591. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2005.35.5.581

- Austin, J. T. & Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychological Bulletin, 120(3), 338–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.120.3.338

- Bae, H., Kim, D., & Park, Y. C. (2015). Dissociation predicts treatment response in eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(1), 112–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.1037039

- Barrett, L. F. (2006). Are emotions natural kinds? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(1), 28–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00003.x

- Batterham, P. J., Ftanou, M., Pirkis, J., Brewer, J. L., Mackinnon, A. J., Beautrais, A., Kate Fairweather-Schmidt, A., & Christensen, H. (2015). A systematic review and evaluation of measures for suicidal ideation and behaviors in population-based research. Psychological Assessment, 27(2), 501–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/PAS0000053

- Baumeister, R. F. (1990). Suicide as escape from self. Psychological Review, 97(1), 90–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.97.1.90

- Beck, A. (1967). Depression. Harper and Row. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1967-35022-000

- Beck, A. T. (1996). Beyond belief: A theory of modes, personality, and psychopathology. In P. M. Salkovskis (Ed.), Frontiers of Cognitive Therapy (pp. 1–25). The Guilford Press.

- Bekrater-Bodmann, R., Chung, B. Y., Richter, I., Wicking, M., Foell, J., Mancke, F., Schmahl, C., & Flor, H. (2015). Deficits in pain perception in borderline personality disorder: Results from the thermal grill illusion. Pain, 156(10), 2084–2092. https://doi.org/10.1097/J.PAIN.0000000000000275

- Bernstein, E. M. & Putnam, F. W. (1986). Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 174(12), 727–735. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198612000-00004

- Besser, A. & Priel, B. (2011). Dependency, self-criticism and negative affective responses following imaginary rejection and failure threats: Meaning-making processes as moderators or mediators. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 74(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2011.74.1.31

- Blatt, S. (2004). Experiences of depression: Theoretical, clinical, and research perspectives. American Psychological Association (APA).

- Blatt, S. J. (1974). Levels of object representation in anaclitic and introjective depression. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 29(1), 107–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00797308.1974.11822616/ASSET//CMS/ASSET/8E9EE78B-6367-423E-8382-A7B38B975FBD/00797308.1974.11822616.FP.PNG

- Blatt, S. J. (1995). Representational structures in psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & S. L. Toth (Eds.), Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology: Vol. 6. Emotion, cognition, and representation (pp. 1–33). University of Rochester Press.

- Blatt, S. J. (1998). Contributions of Psychoanalysis to the understanding and treatment of depression. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 46(3), 723–752. https://doi.org/10.1177/00030651980460030301

- Blatt, S. J. (2008). Polarities of experience: Relatedness and self-definition in personality development, psychopathology, and the therapeutic process. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11749-000

- Blatt, S. J., Auerbach, J. S., & Levy, K. N. (1997). Mental representations in personality development, psychopathology, and the therapeutic process. Review of General Psychology, 1(4), 351–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.1.4.351

- Block, J. (2002). Personality as an affect-processing system: Toward an integrative theory. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Bollas, C. (1979). The transformational object. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 60(1), 97–107. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/457346

- Bornstein, R. F. (2001). The impending death of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 18(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/0736-9735.18.1.2

- Brand, B. L., Classen, C. C., McNary, S. W., & Zaveri, P. (2009). A review of dissociative disorders treatment studies. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(9), 646–654. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0B013E3181B3AFAA

- Brand, B. L. & Stadnik, R. (2013). What contributes to predicting change in the treatment of dissociation: Initial levels of dissociation, PTSD, or overall distress? Journal of Trauma & Dissociation: The Official Journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation (ISSD), 14(3), 328–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2012.736929

- Bredemeier, K. & Miller, I. W. (2015). Executive function and suicidality: A systematic qualitative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 170. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2015.06.005

- Briggs, K. & Mellinger, S. (2015). Guardian of the Golden Gate : Protecting the line between hope and despair. Ascend Books.

- Brown, G. W., George, W., & Harris, T. O. (2012). Social origins of depression : A study of psychiatric disorder in women. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Social-Origins-of-Depression-A-study-of-psychiatric-disorder-in-women/Brown-Harris/p/book/9780415510929

- Calati, R., Bensassi, I., & Courtet, P. (2017). The link between dissociation and both suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury: Meta-analyses. Psychiatry Research, 251, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2017.01.035

- Cardeña, E. (1994). The domain of dissociation. In S. J. Lynn & J. W. Rhue (Eds.), Dissociation: Clinical and Theoretical Perspectives (pp. 15–31). The Guilford Press.

- Caulfield, N. M., Karnick, A. T., & Capron, D. W. (2022). Exploring dissociation as a facilitator of suicide risk: A translational investigation using virtual reality. Journal of Affective Disorders, 297, 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2021.10.097

- Celani, D. P. (1999). Applying Fairbairn’s object relations theory to the dynamics of the battered woman. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 53(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.PSYCHOTHERAPY.1999.53.1.60

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Risk and protective factors suicide. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/factors/index.html

- Comparelli, A., Corigliano, V., Montalbani, B., Nardella, A., De Carolis, A., Stampatore, L., Bargagna, P., Forcina, F., Lamis, D., & Pompili, M. (2022). Building a neurocognitive profile of suicidal risk in severe mental disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04240-3

- Coyne, J. C. (1976a). Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85(2), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.85.2.186

- Coyne, J. C. (1976b). Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry, 39(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874

- Dalenberg, C. J., Brand, B. L., Gleaves, D. H., Dorahy, M. J., Loewenstein, R. J., Cardeña, E., Frewen, P. A., Carlson, E. B., & Spiegel, D. (2012). Evaluation of the evidence for the trauma and fantasy models of dissociation. Psychological Bulletin, 138(3), 550–588. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027447

- Dalenberg, C. & Carlson, E. (2010). New versions of the dissociative experiences scale: The DES-R (revised) and the DES-B (brief). Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Montreal, Quebec.

- Depue, R. A. & Monroe, S. M. (1986). Conceptualization and measurement of human disorder in life stress research: The problem of chronic disturbance. Psychological Bulletin, 99(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.99.1.36

- Duffy, M. E., Buchman-Schmitt, J. M., McNulty, J. K., & Joiner, T. E. (2022). Eyes fixed on heaven’s gate: An empirical examination of blink rate and suicide. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2022.2083536

- Dunkley, D. M., Zuroff, D. C., & Blankstein, K. R. (2003). Self-critical perfectionism and daily affect: Dispositional and situational influences on stress and coping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.234

- Eagle, M. N. (2011). Psychoanalysis and the enlightenment vision: An overview. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 59(6), 1099–1118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065111428611

- Erdelyi, M. H. (2006). The unified theory of repression. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29(5), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X06009113

- Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1944). Endopsychic structure considered in terms of object-relationships. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 25, 70–93.

- Fakhry, H. (2015). Dissociative phenomena in attempted suicide. Egyptian Journal of Psychiatry, 36(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.4103/1110-1105.153779

- Ferenczi, S. (1988). Confusion of tongues between adults and the child. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 24(2), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107530.1988.10746234

- Fernández-Sevillano, J., Alberich, S., Zorrilla, I., González-Ortega, I., López, M. P., Pérez, V., Vieta, E., González-Pinto, A., & Saíz, P. (2021). Cognition in recent suicide attempts: Altered executive function. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYT.2021.701140

- Fonagy, P. (1995). Psychoanalytic and empirical approaches to developmental psychopathology: An object-relations perspective (T. Shapiro & R. N. Emde, eds.; pp. 245–260). International Universities Press, Inc.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300

- Gilbert, D. T. & Wilson, T. D. (2007). Prospection: Experiencing the future. Science, 317(5843), 1351–1354. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1144161

- Greenberg, J. R. & Mitchell, S. A. (1983). Object relations in psychoanalytic theory. Harvard University Press.

- Green, J. D., Sedikides, C., Pinter, B., & Van Tongeren, D. R. (2009). Two sides to self-protection: Self-improvement strivings and feedback from close relationships eliminate mnemic neglect. Self and Identity, 8(2–3), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860802505145

- Gutierrez, P. M., Joiner, T., Hanson, J., Stanley, I. H., Silva, C., & Rogers, M. L. (2019). Psychometric properties of four commonly used suicide risk assessment measures: Applicability to military treatment settings. Military Behavioral Health, 7(2), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/21635781.2018.1562390

- Hammen, C. (1991). Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 555–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555

- Holmes, E. A., Brown, R. J., Mansell, W., Fearon, R. P., Hunter, E. C. M., Frasquilho, F., & Oakley, D. A. (2005). Are there two qualitatively distinct forms of dissociation? A review and some clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2004.08.006

- Horney, K. (1936). Culture and neurosis. American Sociological Review, 1(2), 221. https://doi.org/10.2307/2084481

- Horowitz, M. J. (1998). Cognitive psychodynamics: From conflict to character. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(Issue 2). https://doi.org/10.1176/AJP.156.2.331

- Jamison, K. R. (1996). An unquiet mind: A memoir of moods and madness. VIntage.

- Jobes, D. A. & Joiner, T. E. (2019). Reflections on suicidal ideation. The Crisis, 40(4), 227–230. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000615

- Joiner, T. E. (1994). Contagious depression: Existence, specificity to depressed symptoms, and the role of reassurance seeking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.287

- Joiner, T. E. (2000). Depression’s vicious scree: Self-propagating and erosive processes in depression chronicity. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 7(2), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/CLIPSY.7.2.203

- Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press.

- Joiner, T. E., Hom, M. A., Rogers, M. L., Chu, C., Stanley, I. H., Wynn, G. H., & Gutierrez, P. M. (2016). Staring down death: Is abnormally slow blink rate a clinically useful indicator of acute suicide risk? Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 37(3), 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000367

- Kelly, G. A. (1955). The psychology of personal constructs: Vol. 1. A theory of personality. Vol. 2. Clinical diagnosis and psychotherapy. Norton.

- Kemberg, O. F., Yeomans, F. E., Clarkin, J. F., & Levy, K. N. (2008). Transference focused psychotherapy: Overview and update. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 89(3), 601–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1745-8315.2008.00046.X

- Kernberg, O. F. (1984). Severe personality disorders: Psychotherapeutic strategies. Yale University Press, Ed.

- Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H., & Laddis, A. (2022). The linear and non-linear association between trauma, dissociation, complex PTSD, and executive function deficits: A longitudinal structural equation modeling study. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 28(3), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2022.2101734

- Klein, M. (1928). Early stages of the Oedipus conflict. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 9, 167–180.

- Klein, M. (1935). A contribution to the psychogenesis of manic-depressive states. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 15, 145–174.

- Klein, M. (1940). Mourning and its relation to manic-depressive states. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 21, 125–153.

- Klein, M. (1945). The Oedipus complex in the light of early anxieties. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 26, 11–33.

- Kleindienst, N., Limberger, M. F., Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Keibel-Mauchnik, J., Dyer, A., Berger, M., Schmahl, C., & Bohus, M. (2011). Dissociation predicts poor response to dialectial behavioral therapy in female patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(4), 432–447. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.432

- Klein, M., Kupfer, D. J., & Shea, M. T. (1993). Personality and depression: A current view. Guilford press.

- Lazarus, G. & Rafaeli, E. (2023). Modes: Cohesive personality states and their interrelationships as organizing concepts in psychopathology. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 132(3), 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000699

- Levinger, S., Somer, E., & Holden, R. R. (2015). The importance of mental pain and physical dissociation in youth suicidality. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 16(3), 322–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2014.989644