ABSTRACT

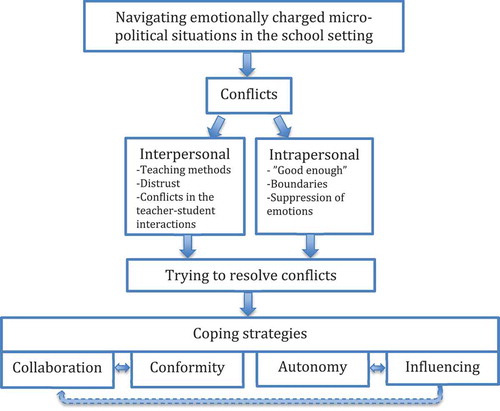

The aim of the present study was to use the narratives of beginning teachers to investigate the emotionally challenging situations they face, with a focus on how their perspectives and definitions of such situations guided their actions and made coping possible. A short term longitudinal qualitative interview study was adopted. Twenty participants were interviewed at the outset of their last year of teacher education and then followed up with an interview at their first year of teaching. In between self-reports were written in addition to the interviews. The material was analysed using constructivist grounded theory tools. The findings show that new teachers experienced conflicts that were both interpersonal (with students, parents and colleagues) and intrapersonal (being ‘good enough’; establishing boundaries related to time and engagement; suppression of emotions) as they started out in teaching. In order to cope with these challenges, the beginning teachers used various strategies including collaboration, conformity, influencing and autonomy.

Introduction

Several studies have reported that new and less experienced teachers face complicated socialisation processes and collegial situations in the beginning of their careers (Caspersen & Raaen, Citation2014; Jokikokko et al., Citation2017; Kelchtermans and Ballet Citation2002), which are affected by micro-political contexts. The school setting is often full of conflict, tensions and rivalry as well as opportunities for collaboration and coalition, all of which influence the practice of new teachers. Beginning teachers have to engage in understanding the setting and establish themselves within it (Kelchtermans and Ballet Citation2002), even though some schools have been found to give little or no support for beginning teachers to develop coping strategies (Le Maistre and Paré Citation2010). Micro-political tensions may arise from, among other things, interactions with colleagues. Success in building mutual trust with colleagues has been found to reduce beginning teachers’ turnover intentions. Other issues related to turnover intentions include emotional commitment and experiencing role conflicts concerning contradictory elements such as enhancing student influence and being responsible for students results (Tiplic, Lejonberg, and Elstad Citation2016). A fair amount of research has been carried out on the topic of challenges beginning teachers face. However, Jokikokko et al. (Citation2017) have noted that much of this research has been directly related to classroom practice, with less focus given to micro-political situations, socialisation and power relations in interactions with other actors in school settings.

The present study focuses on the narratives of beginning teachers at the end of their first year of work and is the continuation of an analysis of longitudinal data presented and discussed in Lindqvist et al. (Citation2018). The overall aim was to contribute to filling the aforementioned gap in research concerning socialisation into the teaching profession and to make two specific contributions to the existing literature on the process of starting to teach. First, we aimed to explore the perspectives of beginning teachers on the issues concerning the emotionally challenging situations they face. Secondly, we sought to investigate the socialisation process of beginning teachers with a qualitative longitudinal data and a grounded theory methodology. The aim of the study was to use the narratives of beginning teachers to investigate the emotionally challenging situations they face, with a focus on how their perspectives and definitions of these situations guided their actions and made coping possible.

Micro-political perspectives on starting to teach

The micro-political perspective focuses on how power relations influence a specific school setting, which involves relationships between various actors (Ehrich and Millwater Citation2011). Blase (Citation1988) described the concept of power as used either to influence others or as self-protection in the school setting. Blase (Citation1988) also distinguish between reactive and proactive coping strategies of teachers. Reactive strategies aim at maintaining a situation, and serve as protections from change and proactive strategies, on the other hand, strive to change situations and conditions.

Micro-politics includes how teachers act towards students and each other in collaboration (Achinstein Citation2002), and new teachers need to develop a micro-political literacy to disentangle the traditions and cultures of the particular school they start working in (Kelchtermans and Ballet Citation2002). The micro-political lens of starting to teach involves focusing on relationships, values and power relations that exist in schools (Shapiro Citation2010). Shapiro (Citation2010) argues for enhanced awareness of teachers to counteract that their emotional experiences leads to actions that focus on the technical aspects of the teaching profession, instead of the personal connections between student and teacher. When working as a teacher, relationships are important to consider through a micro-political lens, as relational aspects are a central part of the teaching profession; meeting multiple actors in everyday school. According to Kelchtermans and Ballet (Citation2002) beginning teachers desired working conditions include relational aspects that operate as a political dimension: ”Through micropolitical actions teachers will strive to establish the desired working conditions, to safeguard them when they are threatened or to restore them when they have been removed” (Kelchtermans and Ballet Citation2002, 756). The desired working conditions involves relationships with colleagues, and when relationships with colleagues are experienced as negative Kelchtermans and Ballet (Citation2002) show how a positive relation with a principal can alleviate feelings of frustration. Teachers’ work involves emotional rules (Zembylas Citation2005) regarding whether emotions should be controlled or expressed. Emotional rules are defined as dependent on the context of a specific school, as well as being historical contingent and in part controlled by the teacher. One example of emotional rules involved caring and sympathy as thought to be favourable and anger as not being preferable (Isenbarger and Zembylas Citation2006; Lindqvist et al. Citation2018). Caring is a central theme of preferable action in the teaching profession (O’Connor Citation2008). As well as the technical and practical side of the work, teaching involves maintaining a number of relationships. For this reason, emotions are a structural condition of the school setting (Kelchtermans Citation2005).

In the micro-political school setting, emotions are not only private but also constructed between the teacher and the working conditions of the school. Uitto et al. (Citation2015) have argued that the micro-political context is at the heart of the teacher’s identity, with a beginning teacher moving between contradictory emotions created in the school setting. For example, being part of several relationships within a school can still be experienced as lonely in a culture of silence (Uitto et al., Citation2015). Kelchtermans and Ballet (Citation2002) have been influential in establishing the micro-political perspective as potent in disentangling the experiences of beginning teachers in the complex process of socialisation. Beginning teachers are to be involved in existing issues of power, organisational interest and strategies to deal with tensions.

Conflicts when starting to teach

Previous research on the first years of teaching has depicted this period as one of struggle for many teachers. For example, it has been discussed that they may experience transition shock or practice shock as they leave teacher training (cf. Caspersen and Raaen Citation2014). Veenman (Citation1984) discussed the similar issue of reality shock more than 30 years ago, and concluded that ‘this concept is used to indicate the collapse of the missionary ideals formed during teacher training by the harsh and rude reality of everyday classroom life’ (p. 143). Zhu et al. (Citation2018) concluded that the socialisation process starts when student teachers undertake work placement education, and depicted the process as fragile and uncertain, among other things in relation to conflicting commitments and responsibilities. Starting to teach is fraught with emotions that add to the difficulty of navigating the conflicts often encountered in this period (Lindqvist et al. Citation2017).

Some of the areas of conflict highlighted in research on new teachers include classroom management (Veenman Citation1984), finding an emotional balance with relationships at work (Richardson, Watt, and Devos Citation2013), constantly negotiating appropriate actions and thinking (Jokikokko et al. Citation2017), and not receiving support because of a lacking vocabulary with which to express concerns (Caspersen and Raaen Citation2014). In a study of the induction period for beginning teachers, McCormack and Thomas (Citation2003) described several areas of tension regarding socialisation, including: (1) negative attitudes and work ethics from older, long-term staff; (2) lack of communication between staff, faculties and school executive; (3) negative public perception of teachers; (4) lack of support from the executive to try new things and develop teaching styles; and (5) dealing with school politics and staffroom power struggles (McCormack and Thomas Citation2003, p. 132–133). Hong (Citation2012) showed how new teachers who stayed in the profession after the first years created emotional boundaries that helped them avoid making their perceived professional problems as personal. Beginning teachers often experience a mixture of positive and negative interactions with students, and there is a positive correlation between problems in student-teacher interactions and turnover intentions (Heikonen et al. Citation2017). This illustrates the importance of a micro-political lens. For example, teacher-student interactions are influenced by the traditions and values of the school setting. In this study, our objective was to contribute to the existing literature of beginning teachers emotionally challenging situations. We contribute with beginning Swedish teachers’ perspectives on starting to teach through the use of longitudinal qualitative data and a grounded theory methodology.

Methodology

The transformation from student teacher to beginning teacher involves interactions with multiple agents, but also perceived conflicts of starting to work as a teacher. A qualitative design was chosen to study the teachers’ perspectives and their perceived emotionally challenging situations.

In line with a constructivist version of grounded theory, we viewed social reality as constructed and as a part of an ever-changing process. Symbolic interactionism was adopted as a theoretical framework (Blumer Citation1979; Charmaz Citation2014; Charon Citation2007). An important aspect is how actors are interacting and make interpretations in social processes and how different interpretations are constructed out of social interactions (Blumer Citation1979; Forsberg and Thornberg Citation2016), and the beginning teachers’ perspectives are useful in the attempt to understand the emotionally challenging situations they experience.

In accordance with symbolic interactionism, the actions and processes of the study participants require that there is an upheld construction and maintenance of meaning (e.g. Blumer Citation1979). In line with the pragmatist view (e.g. Charmaz Citation2014) we consider knowledge as constructed through action and reflection. The negotiated and renegotiated social order of a teacher’s development was seen as constructed in the interactional process in schools (Strauss Citation1978). The social ordering of being a beginning teacher is full of meaning construction and the struggle to understand the complexity of the job, where a social position is inevitable among colleagues and students in the micro-political setting (Kelchtermans and Ballet Citation2002; McCormack and Thomas Citation2003; Uitto et al., Citation2015).

Participants and data collection

A short-term longitudinal qualitative interview study was adopted. The longitudinal data comprise a starting interview that has been analysed and described in Lindqvist et al. (Citation2018), and another interview after a year of teaching. Over two years, we collected three written self-reports from each participant as they progressed from student teachers to new teachers. All 25 participants took part in the first self-report, 24 participants in the second and 19 participants in the third self-report. The reduced number of participants over time was due to different reasons, for example maternity leave. The two first self-reports were collected while the participants were student teachers and the third after they had started teaching. At the end of their first year as teachers, another interview was conducted with 20 of the 25 participants. As student teachers they were trained to teach in Swedish compulsory schools for children aged ten to sixteen. The training consisted of two different programmes: the student teachers studied either to teach grades four to six (ages ten to twelve) or grades seven to nine (ages thirteen to sixteen). When starting work, three teachers who had studied to teach grades seven to nine started teaching in another grade than the one they had studied for.

Seven of the participants were male, seventeen were female and one identified as non-binary. Their ages spanned from 22 to 56 years old (see ). The participants were recruited from six teacher-training programmes in Sweden through e-mail contact. The data consisted of 68 self-reports and 20 interviews. The interviews were performed after the beginning teachers concluded their first year of teaching.

Table 1. Participants

The study was given ethical approval from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Dnr 2014/1088–31/5). The participants gave informed consent and were informed about confidentiality and the right to decline their participation at any point in the research process. The interview material constituted a large part of the data. The aim was to create an open, non-judgmental atmosphere during the interviews. This included using probing questions, as well as follow-up questions (Hiller and Diluzio Citation2004; Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2009).

The interview questions focused on emotionally challenging situations encountered when starting to teach, as well as the transformation from student teacher to beginning teacher. Also, worries discussed in the initial interview were revisited further on in the study, allowing the participants to reflect on themes from the previous interview. The interviews were recorded and transcribed and fictional names are used. The interviews were performed in various locations, the majority via video link. The length of the interviews ranged from 30 to 90 minutes (m = 66.95; sd = 12.62).

The word count of the self-reports varied from 101 to 2,546 (m = 525.30; sd = 397.11). The first self-report asked follow up questions about the initial interview (reported in Lindqvist et al. Citation2018). The second self-report asked about any worries participants might have about starting to teach and was conducted late in the same term the student teachers graduated. The third and final self-report asked about how the participants had experienced and encountered, and what they felt about starting to teach after six months.

Data analysis

The analysis was guided by a grounded theory approach. As the stressful situations examined were seen as social processes, where meaning is created through interaction that guides actions, grounded theory was considered a suitable choice. The use of grounded theory was a way of staying close to the data and in a flexible manner using tools to put the participants’ perspectives in focus. The use of tools such as coding, constant comparison, memo writing, and memo sorting was important in the research process (Charmaz Citation2014; Glaser Citation1978; Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). The three stages of initial, focused and theoretical coding were carried out, although this was not done in a strictly linear fashion. To be able to be sensitive to the data, the stages of coding were flexible and intertwined, with theoretical and focused coding performed more or less in parallel. The transcription of the first interview was coded with initial coding: word-by-word, sentence-by-sentence, and segment-by-segment (Charmaz Citation2014). The process moved into focused coding with a vast number of codes (Charmaz Citation2014) and the significant and common codes were elevated and guided further data collection and coding. In focused coding, iterative definitions of categories were constructed. Theoretical coding was used and a beginning iterative analysis was elaborated when trying out relationships between the codes (Glaser Citation1978; Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2014).

Memo writing was important in order to try out codes, cluster of codes and further conceptualise working theories when constantly comparing codes, analytical thoughts and models. (Charmaz Citation2014). It is important to consider that in a constructivist grounded theory approach, the researcher is seen as an active part in constructing the interview data. Underpinning this research is a belief that it is impossible to occupy a completely objective position as a researcher – a position that is also rejected in the pragmatist tradition (Biesta and Burbules Citation2003). The collected data is not seen as a complete picture outside of an interpretative framework (Charmaz Citation2014). We used our pre-existing knowledge of theories (micro-political theory of the school setting) as sensitising concepts and analytical tools – not in a forced manner, but rather reflexively and with theoretical agnosticism and theoretical pluralism as guiding principles (Thornberg Citation2012).

Findings

A key part of coping with starting to work as a teacher is to establish boundaries. Boundaries refer to a teacher’s ability to identify the possibilities and restrictions of the teaching profession, and as such use these possibilities and restrictions to cope with demands involved with teaching (Lindqvist et al. Citation2018). Student teachers experienced balancing acts in trying to establish professional boundaries. When starting out, the beginning teachers had to make sense of the boundaries of the role, which they had already started formulating during their training. The beginning teachers processed their previous understanding of the work against the tensions of the context of their school.

I will maintain a low profile as a newcomer, but at the same time I hold strong opinions and I will not be able to not discuss if it is something I have an opinion about. I hope I can be professional and learn from people with experience without learning the wrong methods. (Lotta, self-report 1, 7-9)

Lotta identified that her colleagues might influence her as a newcomer and feared that this influence could lead her to bad practice. The main concern for beginning teachers was how to resolve conflicts in the school setting.

The conflicts encountered in the school context were interpersonal and intrapersonal. When meeting the landscape of a school, the beginning teachers found themselves in conflict with various actors connected to the school (i.e. colleagues, parents, students, principals). They also found themselves in conflict with their own ideals, values and norms regarding being a good teacher. The beginning teachers talked about the conflicts they encountered in emotionally charged language, expressing the emotional strain they felt. The boundaries that the beginning teachers tried against the tensions of their school involved micro-political perspectives with numerous actors in the school setting, with whom the beginning teachers found themselves in conflict with in relation to power struggles (Ehrich and Millwater Citation2011). They also found themselves in conflicts with their own ideals, and with their desired working conditions (Kelchtermans and Ballet Citation2002). Examples of each type of conflict are shown in .

Table 2. Conflicts commonly expressed by the beginning teachers

Intrapersonal conflicts

Intrapersonal conflicts were defined as conflicts that new teachers had with their own teaching ideals when faced with the micro-political context of the school. The participants described having trouble with: (1) their view of being a ‘good enough’ teacher; (2) setting boundaries of time and engagement; and (3) suppressing their emotions.

‘Good enough’

Concerns about being a ”good enough” teacher stemmed from conflicts about values of education. Education centred on teaching subjects, as well as using relationships to develop students’ social progression. Daniel talked about lowering his demands on his teacher performance as a consequence of lack of energy.

During the term I’ve lowered the demands on myself a little. From being high, they were probably very high in the middle, and then now it has been more some sort of survival in what I’ve done. Yeah well, you don’t have the time and because now you don’t really have the energy. (Daniel, interview, 7-9)

Daniel had spent a lot of energy on dealing with conflicts among students. He changed schools during his first year of teaching, but found himself in a similar position at the new school. Lena discussed the importance of being a ‘good’ teacher and concluded that she should not continue as a teacher if she did not think she was doing a good enough job.

I’m very self-critical and it’s like this all of the time, ever since graduation and before graduation, this question: Am I a good teacher. Is this right? Because if I’m not a good teacher then I should not be a teacher because the profession is so important, like that. And then the next question arises: What is a good teacher? Of course. (Lena, interview, 7-9)

Lena questioned her suitability for the profession starting to teach. She was adamant about the importance of competence, and she put pressure on herself in order to meet her ideals about being a teacher.

Limits to time and engagement

The new teachers were required to establish limits concerning time and engagement in regards to their workload. Stefan had experienced problems ‘finding the right balance’, which led to difficulties with sleep and ‘switching off’.

It has been a lot of emotions, like, you have come home some days pretty messed up. Like, what am I doing? I’m not enough, not enough for all students. And that has been tough, I think. I haven’t found the right balance but brought work home and I’ve done that a lot. There’re a lot of emotions you bring home and brood at night and I had a lot of sleeping problems in the beginning. I thought about work 24-7, almost all the time. It was a lot of thoughts about that. But I guess it shows that you’re committed as well, it can be positive. But you have to be able to shut off, and that can be hard in the long run. (Stefan, interview, 7-9)

The beginning teachers often struggled with trying to limit their engagement and leaving work-related thoughts behind when going home. For example, Harriet did not expect that she would meet students with troubling home situations to the extent that she did.

But there have also been a lot more situations with students who have problematic home situations, more than I thought too. That you become, it’s hard to let go, you’re affected by that in a way I couldn’t have imagined. It’s hard letting go of work even if you go home./ … /That’s how I felt this year. (Harriet, interview, 4-6)

In letting go of emotions and establishing boundaries of engagement, sympathy was to be suppressed according to the beginning teachers.

Suppression of emotions

With regards to emotions, the new teachers said that they had to adjust what they felt in their interactions with students, as exemplified by Hannes below. This was also apparent in relation to parents who questioned the new teachers:

/ … /well, they thought that we didn’t get angry, because that was the treatment they were used to all through high school. That you had been angry with them basically, and they tested us as well, they admitted that later, ‘but we tested you’, and we said we understood that was what they did, but like we told them too, it’s not easy all of the time to not be angry, because inside you are angry too. (Hannes, interview, 7-9)

Claire thought she had to suppress her emotions in order to survive in the job: ‘You have to shut off, otherwise you will break’ (Claire, interview, 7–9).

Interpersonal conflicts

Interpersonal conflicts, in other words, conflicts between beginning teachers and other actors, were salient in the participants’ everyday work. Colleagues, parents and students were all described as parties in conflicts. These conflicts involved: (1) teaching methods (colleagues); (2) distrust (colleagues and parents); and (3) student-teacher interactions (students).

Teaching methods

The beginning teachers sometimes had firm beliefs about good teaching methods that occasionally led to conflicts with colleagues. Linn experienced such a conflict when she perceived that the teaching materials available were outdated. She described categorising teachers as either willing to try new approaches or were conservative.

Linn: Well, it’s much more, like I would call them conservative and the other adaptable. Like this, the older generation are very predictable, it’s the same. The students’ work materials are the same as when I went to high school. And that’s a long time ago. And the people who haven’t worked at the same place for as long, they are more –, they dare to try new things and make changes and see how that turns out. They can change some things and like, well, are more focused on solutions and how we can change the structure.

Interviewer: What kind of feelings does this give you, or what types of feelings do you experience from the problems you face?

Linn: Extreme frustration. (Interview, 7-9)

Tuva described encountering teaching methods she considered outdated or completely meaningless for students’ learning. She engaged in this conflict and succeeded in effecting change, but being the enforcer of change led to increased work duties.

Interviewer: What stops it [the change]?

Tuva: Time, experience. When I forced through these changes, trying to make guidelines for grading and having shorter work periods and that just ended with me thinking of changing occupation, since it has been so damn tough. (Interview, 7-9)

For beginning teachers experiencing conflicts around teaching methods, having set ideals about teaching and progress was what separated the ‘good’ teachers from the ‘bad’ teachers.

Distrust

In conflicts with colleagues, the new teachers expressed feeling questioned and distrusted. Marlene described being challenged by a colleague who reported her to the principal and having the principal check up on her.

In the beginning, before summer break it wasn’t good at all. I was always by myself, sat in my office. As soon as I had a break or something or time to plan I was always alone. Not with the others because in my work team I had a person who was very hard on me. A person who was not nice to me from the very first day. She was always there where everyone else was. And I wanted to avoid her, so I was by myself all of the time. And the principal noticed too. But it is better now, because she doesn’t belong to my team anymore. I have the older, she has the younger [students]/ … /And the colleague had even gone and said that Marlene isn’t doing what she should, she isn’t working. (Marlene, interview, 7-9)

Some beginning teachers reported experiences of being questioned. For example, Lena’s grading practices were distrusted and reported to the principal as wrong by a colleague. Catrin described being questioned for not being able to cooperate:

When we sat down [in the teacher team/authors’ note] and evaluated, we talked about how the communication worked. And she said she doesn’t think it was working at all with me, not at all. And that I was the one to be blamed. (Catrin, interview 4-6)

New teachers were also questioned by parents, as discussed by Paul:

Paul: I got an answer back that now I have talked to my son/ … /and we’ve agreed on you being a bad teacher.

Interviewer: Oh, he wrote it exactly like that?

Paul: Yes. There was nothing wrong with his child, but with me as a teacher. (Interview 7-9)

The experiences of being questioned was emotionally challenging for the new teachers.

Teacher-student interactions

The new teachers often experienced conflict in their interactions with students and depicted conflicts as inherent in the job. Conflicts as inherent with working as a teacher was sometimes shocking to the beginning teachers. Sometimes these experiences were physical.

Interviewer: Are there other times you’ve been exposed to hits?

Klara: Yes it happens.

/ … /

Interviewer: What do you think about that?/ … /

Klara: It is not a fun part of the work.

Interviewer: No, but you do think it’s a part of the work?

Klara: Yeah, I have to.

Interviewer: What do you have to do?

Klara: Well, you have to act when it happens. It’s more like you are protecting the others. You don’t think about yourself then. (Interview, 4-6)

As described by Klara, beginning teachers thought of these conflicts as part of their work, a very emotionally challenging part. Daniel concluded that dealing with such conflicts took up all his focus during a school day.

The start of my teaching career has been a lot tougher than I could have imagined. When I think about my work it’s mostly negative thoughts that pop up in my head. This is because I don’t think my work tasks match the training I received. I spend my days solving conflicts, making sure students behave in an appropriate way (not interrupting, wandering off, harassing others or throwing things) and contacting parents. Sometimes I wonder if I have had the time to teach and give the students the education they have a right to get. (Daniel, self-report 3, 7-9)

These conflicts sometimes resulted in feelings of inadequacy and lack of control. In addition, the beginning teachers reported that they did not have the formal competence to deal with conflicts, as described by Ben.

The student can intentionally destroy the lesson, attack several other students or doesn’t care to participate in the lesson content at all. Several times the student has been loud and frivolous to the extent in the classroom that I have had to force the student out of the classroom, because otherwise I can’t guarantee learning that everybody else has a right to. The only recommendation I’ve been given is not to touch the student. This is impossible because the student can mess about in the classroom to the extent that I have to stop him and physically force the student out of the classroom. (Ben, self-report 3, 4-6)

Overall, the beginning teachers discussed a range of strenuous experiences in relation to their initial period of teaching. They also discussed several strategies they used to cope with these challenges.

Coping strategies

Coping strategies refer to action taken to alter, tolerate or reduce the effects of stressful events. The beginning teachers used various coping strategies to deal with the abovementioned conflicts (illustrated in ).

Table 3. Strategies to cope

Collaboration

A prominent way of coping was to form collaborations with colleagues; this has also been found to be a commonly anticipated coping strategy among student teachers (Lindqvist et al. Citation2017, Citation2018). The beginning teachers used three distinct methods of establishing collaboration. The first method was to try to find an ally, with the aim of having one trusted colleague to share adversity with.

And I believe that our communication has been important between us, that we created good cooperation. We pull towards the same end and have some similar thoughts about pedagogy. (Catrin, interview, 4-6)

The second method was to seek support from the team of teachers of which the beginning teacher was a part. No single ally was specified as important, but rather the whole teaching staff was addressed when conflicts needed to be dealt with.

Alice: Because I noticed it didn’t work, I talked to the colleagues here. I told them that I thought it was hard, and that I felt that it became, that it escalated when I interfered. And then they talked to me and gave advice, and said back off a little. We are more people working here. You do not have to do everything.

Interviewer: Did it feel like you did everything?

Alice: Yeah, but in some ways I felt I was responsible here. Now I have to do this.

Interviewer: Well, okay, what do you think about working here with the other teachers, how is the collegiality at the school?

Alice: It works great. They are very supportive and there have been a few times when lessons spiralled out of control [inaudible], you know, complete chaos and everyone is running around and yelling and stuff like that. Then you can call for help and someone will come and help you. Very helpful colleagues, and understanding and who listen when there is something that you want to talk about and that you feel is tough. (Interview, 7-9)

The third collaborative coping strategy was to turn to the principal or other support staff, as described by Harriet below.

I have talked a lot with my colleague. We have close contact. We talk a lot about single students. And I also contacted the school counsellor for support. I’ve asked him for help about how you can think or what you can do in the best way to help this student. And I’ve talked to my principal about it. So I’ve tried to seek help from colleague, people with more experience of how to handle these situations, that’s more like what I’ve done. (Harriet, interview, 4-6)

Collaboration was effective, first and foremost, when the beginning teachers aligned themselves with the values and power relations of the school and did not challenge the school’s system. In engaging in collaboration strategies, the beginning teachers described being accepted as team members, and this had an alleviating impact on Catrin when she found herself in conflict with another teacher. Furthermore, Harriet’s self-efficacy beliefs seemed to be increased through seeking help and guidance from more experienced colleagues. Collaboration is here understood as a proactive strategy (Blasé Citation1988).

Conformity

To use conformity as a coping strategy, beginning teachers had to get to know the school and read the context in order to align with the school setting. Paul exemplified conformity: ‘You have to be a somewhat of a chameleon, so that you blend in a little. I don’t think it would be favourable to come in and run your own race from the beginning’ (Paul, interview 7–9). Anders discussed doing what he was told as a strategy for coping with the all the instructions that comes with being new. Anders did identify the risk of having too much to do over a long period of time, which could mean potential exhaustion or burnout.

I have had that thought, like I told you before, you can’t have this pace forever./ … /I wouldn’t say I’m worried, since when you are new you do what people, and with people I mean the principal, and the one’s deciding, tell you. (Anders, Interview, 4-6).

Another example of conformity as a coping strategy was adjusting to the school administration. The new teachers had different experiences of school leadership. Pia discussed how she conformed to the ideals of her principal.

Now I’ve a great leader for example/ … /. She says it’s not up to her, I think this is bad, but we have to do this. And then you accept it and you work on, and you work together instead of feeling it’s her against us. So that feels great. (Pia, Interview, 7-9)

In relation to principals, other beginning teachers used influencing or autonomous strategies.

Lacey (Citation1977) distinguish between different forms of socialisation as dependent on value commitment and behavioural conformity. The definition of conformity used here refers to a process that produced internalised adjustments, where the teacher believes that those in power authority are those who are best capable to interpret situations and therefore accept the constraints this involves for the teacher. Conformity here is understood as a reactive strategy (Blase Citation1988), with trying to conform to protect the teacher from pressures experienced. Beginning teachers often approached the school administration in order to rectify negative situations, such as having less time teaching or better work conditions, as well as getting help with handling complicated student situations.

Influencing

Trying to influence the micro-political school context was a strategy whereby the beginning teachers deliberately tried to enforce changes that aligned with their ideals, and related to a proactive coping strategy (Blase Citation1988). Disa experienced resistance from some of her colleagues to being a part of anything that challenged their way of working. Even so, within her first year Disa was appointed to be team leader and tried to influence the school’s way of meeting the needs of students.

Disa: I was made team leader two months ago.

Interviewer: What do you think about that?

Disa: Being a team leader?

Interviewer: Well, about these groups and being a leader?

Disa: Like, it would be easy being a leader if I knew everyone contributed. (Interview, 7-9)

New teachers who tried to introduce change for the better – for example better teaching methods or better work conditions – experienced the attempt as overwhelming. Disa found her work as a leader and influencer strenuous, and Tuva experienced having too little experience of the teacher occupation. Tuva said that even though using influencing as a strategy meant that teaching might become better in terms of students active learning, it was too much for her to handle.

Yes, exactly, more certain about assessment, more certain when having presentations, and like, more certain of what is good teaching. I still feel, like I have been talking about, it is still, I tried to change and that was so much work, so I have to change it for the better but not creating too much work. (Tuva, interview, 7-9)

Using an influencing strategy meant the beginning teachers also had an autonomous understanding of the teaching profession, since trying to influence included making decisions as well as believing in the own ability to cope.

Autonomy

Autonomy here is understood as having agency to act according to own beliefs, and thus being autonomous in relation to colleagues. Some new teachers refrained from taking part in the collegiality of the school. Marlene described how she rushed to her car at the end of the school day, keeping to herself in the beginning of her role. Katarina described how she used an autonomous position to cope with conflicts within the teaching staff, and how that helped her not to feel affected.

I try to take that with me instead, because I’m not involved in those discussions right now. I feel I want to have a few more years in the profession before I do that. But I’m not affected. I just shrug my shoulders. (Katarina, interview, 4-6)

Ann described how she was able to deal with problems in her student group and listening to colleagues who gave advice. This means she did not copy colleagues work. She developed a tactic from using advice and redesigning the advice into something she could use: ‘Yeah, first some tools and advice from the colleagues, what they do. Then I re-do it, or make up something of my own because I get an idea when they talk’ (Ann, interview 4–6). Another example of using autonomy was creating lessons and using material the new teachers thought was better than what they thought colleagues used. In this way, autonomy meant having the freedom to match one’s ideals of teaching. Even so, sometimes this approach caused trouble with other teachers, as described by Kim.

Kim: / … /in German it is common to use a workbook, and I didn’t like the book so I tried using other stuff than the book. And then I was ordered by my colleagues and the principal to use the book because they’d noticed I spent too much time planning. Or they said, well you have to use the book otherwise you will not be able to do anything else but work.

Interviewer: No.

Kim: And then I tried, and still I lose the will to live teaching from the book. (Interview 7-9).

Kim realised that maintaining autonomy as a strategy was hard. Even though Kim decided to implement her colleagues’ suggestions, she still felt the need to change and to do what felt better. Autonomy differs from an influencing strategy because it has no explicit intention to alter other teachers’ work, even though using an autonomy strategy will have an impact on the school setting despite this not being a primary goal. Autonomy, here understood as taking control and changing the conditions in the classroom, is a proactive strategy (Blase Citation1988) that focuses on change for the individual teacher, without the explicit intent to influence others.

Navigating emotionally charged micro-political situations

When encountering conflicts, both interpersonal and intrapersonal, the beginning teachers used various coping strategies. The relations between the strategies are shown in .

The beginning teachers’ coping strategies were seen as complementary and divided into pairs: collaboration and conformity, and autonomy and influencing. This is due to the fact that the participants who described using an autonomous strategy also tried influencing their surroundings, and trying to influence the surroundings necessarily involved being autonomous. Influencing in the school setting also sometimes led to collaboration, if the parties involved were open to such endeavours. However, there was no symbiotic relationship between influencing and collaboration. The strategies above are seen as part of the continuous process of navigating in the micro-political contexts of different school settings. Furthermore, the emphasis of using a proactive strategy demonstrated the beginning teachers agency and micropolitical power.

The beginning teachers discussed turnover intentions as a micro-political proactive strategy (Blase Citation1988) to protect from emotional challenging situations, using their agency to change school in order to feel that their ideals are matched in the school setting.

Linn: And I think that is exciting and fun. It doesn’t bother me, like, the push forward is like, the more troublesome a student is the more fun it is to find new ways./ … /But this other thing with the organisation and informal leaders and that. It’s really, really tough. That’s what makes me want to change my job.

Interviewer: Yes, informal leaders, you have identified those at your workplace?

Linn: Yes.

Interviewer: Yes, and you don’t agree with what they’re doing, is that how I should interpret that?

Linn: No.

Interviewer: You don’t agree?

Linn: No, we don’t want the same things. (Interview, 7-9)

Linn discussed the idea of changing workplaces as a direct consequence of trying to influence the organisation, and identifying differences in what ‘they want’ with education, and this reflects her micro-political power and agency.

Discussion

We would like to start with pointing out that this research corroborates that beginning to teach is complex, full of competing interests among different stakeholders. The isolation new teachers experience when entering the profession is similar to a student teacher’s fragile and uncertain position (Zhu et al. Citation2018), and they seem to sometimes lack strategies of literacy in reading the micro-political setting of a school (Kelchtermans and Ballet Citation2002), creating emotionally challenging conflicts when starting out. Being able to cope with the transition into teaching involves learning to fit into the complex micro-political setting of a school, and this has been shown to be at the heart of the induction period. The analysis demonstrate that the beginning teachers in part adapt proactive coping strategies (Blase Citation1988), with intentions to be a part of changing a schools micro-political setting. McCormack and Thomas (Citation2003) have discussed lack of communication and negative attitudes from veteran teachers as part of the tensions involved in the induction period. The conflicts the participants reported were experienced as emotionally challenging, and looking only to collegiality to solve such issues may be to ignore the fact that colleagues sometimes take action in rivalry, coercion and struggle, as well as in coalition, collaboration and cooperation. Löfgren and Karlsson (Citation2016) have argued that focusing on collegiality only as either good or bad is problematic. The process of consensus and conflict among colleagues has an effect on the course of professional development. Achinstein (Citation2002) describe how teachers supress or embrace differences when being in conflict. This defines the community borders, and conflicts can strengthen communities, as well as create isolation among teachers. The present study confirms the issues of conflict and consensus as being of essence and intertwined in the process of starting to teach.

Strategies for coping with emotionally challenging micro-political situations included relationships with multiple actors that all new teachers had felt unprepared for. The new teachers who took a collaboration and conformity approach experienced receiving more support from colleagues, which made the start of teaching less lonely. The concept of satisficing (LeMaistre & Paré, Citation2010) may be of use in training teachers. Satisficing refers to finding a way of accepting that the action taken is the best possible option in the context of the resources available. Satisficing could be of use for beginning teachers to better respond to the imbalance between the resources available and the demands of intrapersonal and interpersonal conflicts. Beginning teachers could find an acceptable way of taking the best action that is possible at a given moment. Also, using proactive micropolitical strategies as well as learning micro-political literacy could be of use for the beginning teacher. Therefore, we concur with Ball (Citation1987) that micro-politics should be integrated in teacher education. Beginning teachers are sometimes viewed as change agents and innovators in schools (Fullan Citation1993). Lee (Citation2013) has shown how this innovation might be troublesome to achieve, and how conformity is often the end result; innovation was in essence hindered by school policy and the curriculum that needed to be followed (Lee Citation2013). As change agents, beginning teachers need to identify and relate to the micro-political setting of a school, in order for their competence as innovators to be recognized.

Limitations

Some limitations of the study need to be acknowledged. The analysis was based on data from interviews with beginning teachers and written accounts over a period of one and a half years. Thus, there are no observational or performative data included and we rely on the narratives of the participants. It is possible that the participants may have portrayed the emotionally challenging situations in a way that was favourable to them. Even so, the beginning teachers also reported weaknesses, fears and problems they had encountered.

The research reported relies on the experiences and perspectives of the participants. We do not aim to create a complete picture of all the challenging emotions experienced or strategies used. Instead, we present an interpretative picture of the phenomenon (Charmaz Citation2014). Furthermore, grounded theory does not end in a fixed result, but could be open to modification through further data collection and theoretical sampling (Charmaz Citation2014). The differences between the length of the self-reports are also valuable to consider as a limitation. The self-reports, consisting of a small number of words, did not give a great deal of information. Even so, as a whole, the self-reports as a whole built up a substantial amount of rich data.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Annalena Lönn, Håkan Hult, and Astrid Seeberger for support and valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Henrik Lindqvist

Henrik Lindqvist is a PhD student at Education at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linköping University in Sweden focusing on student teachers learning from, and coping with, emotionally challenging situations in teacher education.

Maria Weurlander

Maria Weurlander, PhD, is associate professor of Technology and learning at the unit of Higher Education Research and Development at the school of Industrial Engineering and Management (ITM) at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden. Her main research focuses are on student learning in higher education, and student teachers’ and medical students’ experiences of and dealing with emotionally challenging situations during their training.

Annika Wernerson

Annika Wernerson, PhD, MD, is professor in renal- and transplantation science at the department of Clinical Science, Intervention and Technology (CLINTEC) at Karolinska Institutet, where she also is Dean of higher education. Her research areas in medical education focus on learning in higher education and medical students’ and student teachers´ experiences of and dealing with emotionally challenging situations during their training and early professional life.

Robert Thornberg

Robert Thornberg, PhD, is Professor of Education at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linköping University in Sweden. He is also the Secretary of the Board for the Nordic Educational Research Association (NERA). His main focuses are on (a) bullying and peer victimization among children and adolescents in school settings, (b) values education, rules, and social interactions in everyday school life, and (c) student teachers and medical students’ experiences of and dealing with emotionally challenging situations during their training.

References

- Achinstein, B. 2002. “Conflict amid Community: The Micropolitics of Teacher Collaboration.” Teachers College Record 104: 421–455. doi:10.1111/tcre.2002.104.issue-3.

- Ball, S. 1987. The Micro-Politics of the School: Towards a Theory of School Organisation. London: Methuen.

- Biesta, G. J. J., and N. C. Burbules. 2003. Pragmatism and Educational Research. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Blase, J. 1988. “The Micropolitics of the School: The Everyday Political Orientation of Teachers toward Open School Principals.” Educational Administration Quarterly 25: 377–407. doi:10.1177/0013161X89025004005.

- Blumer, H. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Caspersen, J., and F. D. Raaen. 2014. “Novice Teachers and How They Cope.” Teachers and Teaching 20: 189–211. doi:10.1080/13540602.2013.848570.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Charon, J. M. 2007. Symbolic Interactionism: An Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration. 9th ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Ehrich, L. C., and J. Millwater. 2011. “Internship: Interpreting Micropolitical Contexts.” The Australian Educational Researcher 38: 467–481. doi:10.1007/s13384-011-0035-7.

- Forsberg, C., and R. Thornberg. 2016. “The Social Ordering of Belonging: Children’s Perspectives on Bullying.” International Journal of Educational Research 78: 13–23. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2016.05.008.

- Fullan, M. G. 1993. “The Professional Teacher: Why Teachers Must Become Change Agents.” Educational Leadership 50: 1–13.

- Glaser, B. 1978. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B., and A. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Heikonen, L., J. Pietarinen, K. Pyhältö, A. Toom, and T. Soini. 2017. “Early Career Teachers’ Sense of Professional Agency in the Classroom: Associations with Turnover Intentions and Perceived Inadequacy in Teacher–Student Interaction.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 45: 250–266. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2016.1169505.

- Hiller, H. H., and L. Diluzio. 2004. “The Interviewee and the Research Interview: Analysing a Neglected Dimension in Research.” CRSA/RCSA 41: 1–26.

- Hong, J. Y. 2012. “Why Do Some Beginning Teachers Leave the School, and Others Stay? Understanding Teacher Resilience through Psychological Lenses.” Teachers and Teaching 18: 417–440. doi:10.1080/13540602.2012.696044.

- Isenbarger, L., and M. Zembylas. 2006. “The Emotional Labour of Caring in Teaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 22: 120–134. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.07.002.

- Jokikokko, K., M. Uitto, A. Deketelaere, and E. Estola. 2017. “A Beginning Teacher in Emotionally Intensive Micropolitical Situations.” International Journal of Educational Research 81: 61–70. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2016.11.001.

- Kelchtermans, G. 2005. “Teachers’ Emotions in Educational Reforms: Self-Understanding, Vulnerable Commitment and Micropolitical Literacy.” Teaching and Teacher Education 21: 995–1006. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.009.

- Kelchtermans, G., and K. Ballet. 2002. “Micropolitical Literacy: Reconstructing a Neglected Dimension in Teacher Development.” International Journal of Educational Research 37: 755–767. doi:10.1016/S0883-0355(03)00069-7.

- Kvale, S., and S. Brinkmann. 2009. Den Kvalitativa Forskningsintervjun. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Lacey, C. 1977. The Socialization of Teachers. London: Methuen.

- Le Maistre, C., and A. Paré. 2010. “Whatever It Takes: How Beginning Teachers Learn to Survive.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26: 559–564. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.06.016.

- Lee, I. 2013. “Becoming a Writing Teacher: Using “Identity” as an Analytic Lens to Understand EFL Writing Teachers’ Development.” Journal of Second Language Writing 22: 330–345. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2012.07.001.

- Lindqvist, H., M. Weurlander, A. Wernerson, and R. Thornberg. 2017. “Resolving Feelings of Professional Inadequacy: Student Teachers’ Coping with Distressful Situations.” Teaching and Teacher Education 64: 270–279. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.019.

- Lindqvist, H., R. Thornberg, M. Weurlander, and A. Wernerson. 2018. “Boundary Work in Coping with Distressful Teacher Education Situations.” Paper presented at the 46th Congress of Nordic Educational Research Association in Oslo, Norway, March8–10.

- Löfgren, H., and M. Karlsson. 2016. “Emotional Aspects of Teacher Collegiality: A Narrative Approach.” Teaching and Teacher Education 60: 270–280. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.022.

- McCormack, A. N. N., and K. Thomas. 2003. “Is Survival Enough? Induction Experiences of Beginning Teachers within a New South Wales Context.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 31: 125–138. doi:10.1080/13598660301610.

- O’Connor, K. E. 2008. ““You Choose to Care”: Teachers, Emotions and Professional Identity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24: 117–126. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.008.

- Richardson, P. W., H. M. Watt, and C. Devos. 2013. “Types of Professional and Emotional Coping among Beginning Teachers.” Advances in Research on Teaching 18: 229–253.

- Shapiro, S. 2010. “Revisiting the Teachers’ Lounge: Reflections on Emotional Experience and Teacher Identity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26: 616–621. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.009.

- Strauss, A. L. 1978. Negotiations: Varieties, Contexts, Processes and Social Order. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley/Jossey-Bass.

- Thornberg, R. 2012. “Informed Grounded Theory.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 56: 243–259. doi:10.1080/00313831.2011.581686.

- Thornberg, R., and K. Charmaz. 2014. “Grounded Theory and Theoretical Coding.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Analysis, edited by U. Flick, 153–169. London: Sage.

- Tiplic, D., E. Lejonberg, and E. Elstad. 2016. “Antecedents of Newly Qualified Teachers’ Turnover Intentions: Evidence from Sweden.” International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 15: 103–127.

- Uitto, M., K. Jokikokko, and E. Estola. 2015. “Virtual Special Issue on Teachers and Emotions in Teaching and Teacher Education (TATE) in 1985–2014.” Teaching and Teacher Education 50: 124–135. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2015.05.008.

- Veenman, S. 1984. “Perceived Problems of Beginning Teachers.” Review of Educational Research 54: 143–178. doi:10.3102/00346543054002143.

- Zembylas, M. 2005. “Discursive Practices, Genealogies, and Emotional Rules: A Poststructuralist View on Emotion and Identity in Teaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 21: 935–948. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.005.

- Zhu, G., H. Waxman, H. Rivera, and L. M. Burlbaw. 2018. “The Micropolitics of Student Teachers’ Professional Vulnerability during Teaching Practicums: A Chinese Perspective.” The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 27: 155–165. doi:10.1007/s40299-018-0374-5.