ABSTRACT

This paper argues that metaphorical formulations around genetic categories have important implications for individuals’ experiences of their at-genetic-risk bodies vis-à-vis the market for prevention. Drawing on Jacques Derrida’s concept of usure, our findings unpack three central biomedical metaphors that shape the ways in which ‘previvor’ women with the BRCA gene mutation manage and experience their (risky) body-in-transition against the market for prevention. These are the metaphors of: the container, the omnipresent danger, and battle and journey. Our discussion unravels the processes of the de/re-stabilisation of the (risky) body-in-transition, as well as the reconfiguration of individuals’ rights and duties in the market for prevention to become a good genetic citizen. Moving beyond a discussion of ‘consumer sovereignty’, we contribute to developing a contextually nuanced understanding of the complex relations between the lived experiences of ‘losing control’ and the consumption of prevention.

Introduction

Consumer researchers have long been interested in the role of the body in driving individuals’ consumption decisions and experiences (Arnould & Price, Citation1993; Askegaard et al., Citation2002; Liu, Citation2019; Roux & Belk, Citation2019; Ruvio & Belk, Citation2018; Scaraboto & Fischer, Citation2013; Schouten, Citation1991; Scott et al., Citation2017; Takhar, Citation2020). We argue this is especially the case with the body-in-transition, that is, the transitioning body that is going through some form of transformation. For example, Schouten (Citation1991) and Askegaard et al. (Citation2002) examined the consumption of aesthetic plastic surgery for bodily transformation and how it facilitates people’s rites of passage and identity reconstruction. Here, plastic surgery is perceived as a means of ‘exercising control over one’s body and one’s destiny’, and the body-in-transition is presented as relatively risk-free or a path to desirable interpersonal outcomes (Schouten, Citation1991, p. 418). The body-in-transition is also central to Arnould and Price (Citation1993) and Scott et al. (Citation2017) seminal work on extraordinary consumption experiences such as river rafting trips and Tough Mudder.Footnote1 Both studies focused on the phenomenology of embodiment, where the magic is experienced and operates as regenerative escapes from the burdens of self-awareness. For example, Tough Mudder participants subject their body to many different kinds of pain in search of an escape or a temporary relief from the worries of everyday life (Scott et al., Citation2017). Here, the body-in-transition is depicted as risk-laden, painful (e.g. bruises and injuries), yet sensational and freeing, at least from the perspective of the inner self.

In summary, prior consumer research has treated the body-in-transition as either relatively risky or risk-free. Still, the risks are typically framed as rewarding or worth enduring for positive self-transformation. More recently, investigating tattooed bodies, Roux and Belk (Citation2019) conceptualised the body as the ultimate place we must live in. Here, the body-in-transition or body modifications are about achieving ‘personal transformations whereby people (re)invest in their ultimate living place’ (Roux & Belk, Citation2019, p. 500). Risks, while being considered as negative and requiring careful management, remain in terms of social acceptance and the extent to which one may be subjected to pain (also see Ruvio & Belk, Citation2018). In effect, earlier consumer theorists have privileged voluntary risk-taking and the concept of ‘control’ over one’s own body through means of consumption, emphasising consumer sovereignty and not the potential involuntary risks in the process of body-in-transition such as the high-risk, low-outcome experience of in vitro fertilisation and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (Takhar, Citation2020).

As a result, we know less about the involuntary risk management side of the body-in-transition that is, the experience of ‘losing control’ of one’s own body and how consumption may come into play to manage this sense of loss of control and its inherent risks to the subject. Following previous consumer and marketing literature that has demonstrated the actual and potential contribution of metaphor to marketing theory and practice (Belk et al., Citation1996; S. Brown & Wijland, Citation2018; Fillis & Rentschler, Citation2008; Fournier, Citation1998; Hirschman, Citation2007), our study seeks to address this knowledge gap by centring our inquiry around a priori theme: how do individuals experience their at-genetic-risk bodies through metaphors vis-à-vis the market for prevention? The ‘previvor’Footnote2 narrative generally considers at-genetic-risk bodies as being out-of-control and requiring careful management. It focuses on the transitional state of betwixt and between with the seemingly healthy/cancerous body. The role of preventative healthcare consumption, such as genetic testing, double mastectomy and reconstructive surgery, is to manage this transitional state and the risks associated with it.

Using a linguistically driven analysis, our findings unpack three biomedical metaphorical formulations that drive the ways in which women with the BRCA gene mutationFootnote3 manage and experience their (risky) body-in-transition. We show how the notion of risks is embedded in the metaphors that motivate the deliberations on and felt tensions around their preventative healthcare consumption. To ground our empirical analysis, in the sections that follow, we first start with articulating the appropriateness and usefulness of metaphors in understanding consumption experiences, especially from a Derridean perspective. Next, we offer a brief overview of our research context on the notion of risk as it relates to the responsibilisation of at-genetic-risk bodies. Following this, we detail the methodology used to guide and unfold our data analysis. We conclude by discussing the theoretical and marketing implications of our findings.

Metaphors

Beyond aesthetic embellishment, critical marketing scholars have recognised the crucial role that metaphors play in marketing and consumer discourses and practices (Belk et al., Citation2003, Citation1996; S. Brown, Citation1994; S. Brown & Wijland, Citation2018; Hirschman, Citation2007; Karanika & Hogg, Citation2020; O’Malley et al., Citation2008; Zaltman et al., Citation1982; Zaltman & Zaltman, Citation2008). They are said to provide for ‘fresh, and previously nonexistent, insights into the reality of marketing by offering a hypothesis of the dynamics and identity of a marketing phenomenon’ (Cornelissen, Citation2003, p. 211). For example, Belk (Citation1988) deploys the metaphor of marketplace products and possessions as the extended self to highlight their centrality to consumer identity formations. Fournier’s (Citation1998) seminal work uses the metaphor of human relationships to shed light on consumers’ lived experiences with their brands. Belk et al. (Citation2003) present fire as a metaphor to develop a phenomenological account of consumer desire. More recently, Roux and Belk (Citation2019) view the human body as a metaphorical projection of ‘the place’ we are trapped in to theorise self-transformation in contemporary consumption.

Indeed, metaphorical formulations have critical functions in shaping identities and practices. As Holmes (Citation2011, p. 263, emphasis in original) put it: ‘We live within metaphoric constructions at least as often as we live by them’. The study of metaphorical formulations and their effects is important, as they are intertwined with ideological systems. As Lakoff and Johnson (Citation2003, p. 23) put it ‘values are not independent but must form a coherent system with the metaphorical concepts we live by’. Marketers use metaphorical formulations to gauge consumer behaviours and attitudes to their products, services and brand positionings (Cornelissen, Citation2003; Fournier, Citation1998; Zaltman & Zaltman, Citation2008). Consumers deploy metaphorical narratives to assign symbolic meanings to marketplace offerings (Hirschman, Citation2007). In this study, we draw on Jacques Derrida’s (Citation1982) work on metaphors to show how biomedical metaphorical formulations shape individuals’ experiences and perceived responsibilities of their (risky) bodies-in-transition vis-à-vis the market for prevention.

Derrida and the usure of metaphors

In his essay ‘White mythology’, Derrida (Derrida, Citation1982; Derrida & Moore, Citation1974) coins the term ‘usure’ to describe the death of a living metaphor. This death is metaphorical itself, and describes how sharp and novel metaphors become ordinary and indistinct through constant usage (Billig & MacMillan, Citation2005). However, no matter how mundane they become, metaphorical systems still carry ideological meanings and perform specific rhetorical functions. Put in other words, ‘worn-out’ metaphors acquire a more ‘universalised’ status, while still carrying traces of lost meanings that perform specific functions. For example, both the corporate ‘identity’ and marketing ‘relationship’ metaphors have become part of the taken-for-granted everyday vocabularies in the field of marketing (Cornelissen, Citation2003, pp. 221–222). Today, marketing academics and practitioners investigate the corporate as literally having identity expressions and brands as relationship partners, thereby highlighting how metaphorical formulations contribute to the shaping of the field and the practices around it.

Derrida’s concept of ‘usure’ deconstructs the binary distinction between literal and metaphorical discourses. Rather than studying metaphorical formulations as imperfect alternatives to explicit literal ones, thereby reducing their function to being an embellishment for pure logical argument, Derrida treats them as constitutive of the argument itself (Hepburn, Citation2000). The concept of usure is itself a metaphorical play on the double bearing of the French word ‘usure’. On the one hand, it can be translated to ‘wear and tear’, and refers to the state of becoming worn out. On the other hand, it can be translated to ‘usury’, and refers to usurious economic generation through the production of surplus-value (Derrida, Citation1978). Thus, the concept of usure plays on the dual meaning of both ‘using up’ and ‘usury’ – the former referring to the deterioration through (excessive) usage, and the latter to the accumulation of too much (unlawful) interest. That is, while the former meaning describes the ‘worn-out’ status of metaphors that leads to their generalisation, the latter refers to the surplus value that the metaphoric trait charges the ‘original’ usage as well as the widespread use of this surplus-value which can overshadow the initial meanings. For instance, the metaphorical formulation of corporate ‘identity’ not only refers to ‘selfhood’ but also prompts thinking around how to speak of ‘a singularity of collective action’ (Cornelissen, Citation2003, pp. 214–216). As Derrida (Citation1982, p. 210) put it:

Abstract notions always hide a sensory figure. And the history of metaphysical language is said to be confused with the erasure of the efficacy of the sensory figure and the usure of its effigy. The word itself is not pronounced, but one may decipher the double import of usure: erasure by rubbing, exhaustion, crumbling away, certainly; but also the supplementary product of a capital, the exchange which far from losing the original investment would fructify its initial wealth, would increase its return in the form of revenue, additional interest, linguistic surplus value, the two histories of the meaning of the word remaining indistinguishable.

The displacement of meaning from its previous locations allows the prevalence of an idealised and universalised form of meaning. The withdrawal or ‘retrait’ requires the metaphor to come forth and to generalise with surplus-value in a process that Derrida (Citation1978) describes as ‘quasi-catachrestic violence’. However, the traces of the previous locations are never entirely erased, thus invoking a multivocal meaning. In a sense, the new meaning dominates by virtue of the presence of the other, and not its erasure. The remnants and traces of the lost meanings resurface to disrupt meaning and being, and therefore take part in the bringing into being of new entities. In these terms, metaphors are reproduced, developed and mobilised through speech and practice. They may facilitate certain ways of being, thinking or consuming (Belk et al., Citation2003; Fournier, Citation1998; Roux & Belk, Citation2019). With this in mind, we study the metaphorical formulations and their effects in the context of preventative healthcare consumption.

Biomedical metaphors and the body-in-transition

Metaphorical formulations are also ubiquitous within biomedical sciences and healthcare discourses (e.g. going on ‘war’ against a disease). On the one hand, they can help us make sense of our bodies, by ‘materialising what increasingly feels immaterial and disembodied as it is reinforced by the multiple immaterialities of the contemporary world’ (Holmes, Citation2011, p. 270). On the other hand, they participate in obstructing certain avenues for exploring the body and reinforce dominant biomedical regimes (Takhar & Houston, Citation2021).

To illustrate the role of metaphorical formulations in shaping the experiences and responsibilities of bodies-in-transition, this paper focuses on the market for preventive solutions for breast and ovarian cancers. We emphasise prevention in the context of genetic propensity for these illnesses. The footprint of genetics is strongly visible across the area of health and illness. Through the discovery of disease-causing genes, science claims that we can anticipate and prevent the occurrence of these diseases for both the carrier of the ‘faulty’ gene, as well as their progenies. In this paper, we analyse such cases of genetics’ metaphors in use, and their performative effects in shaping identities and practices of at-genetic-risk subjects. Our empirical material focuses on women who have been identified as carrying a BRCA gene mutation, which is associated with a higher risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. They are generally conceived as the target of the market for prevention.Footnote4

At-genetic-risk bodies: risk, control and responsibilisation

According to Lupton (Citation1999), the loss of control over our bodies is one of the factors that create anxiety, constituting the symbolic basis of our uncertainties. We argue that at-genetic-risk bodies are closely linked with the sense of loss of control, as one engages in ongoing deliberations around what to do and how to feel about their seemingly healthy/cancerous body. From the cultural/symbolic perspective (Douglas & Wildavsky, Citation1982; Lupton, Citation1999), risk is a political concept that is implicated in matters of attribution of accountability, responsibility and blame. Such a perspective highlights how risk may be utilised to ‘establish and maintain conceptual boundaries between self and other’ and how the human body may be used ‘symbolically and metaphorically in discourses and practices around risk’ (Lupton, Citation1999, p. 25). For example, there has been ongoing ambivalence towards women’s contraceptive pills for beliefs that they will pose significant health risks, including the risk of developing cancer (Lupton, Citation2012, p. 145). At the same time, women are made to feel responsible for making choices ‘between use of the pill and the choice of a career over motherhood’ (Lupton, Citation2012). The management of risk in the market for prevention is supposedly bound up with the rhetoric of individual choice (Beck-Gernsheim, Citation2000; Douglas, Citation1992; Lupton, Citation2012; Peterson & Lupton, Citation1996).

Lupton (Citation1999, p. 30) argues that ‘risk’ constitutes a work-in-progress, negotiated reality, which forms part of the ‘assembledges of meanings, logics and beliefs cohering around material phenomena, giving the phenomena form and substance’. Indeed, the concept of risk in modern society is becoming increasingly scientifically reconfigured, emphasising statistics and mathematical calculations to support individual decision-making and increase individuals’ sense of control in their lives. With regards to our study subjects – women with the BRCA gene mutation – individual choice can be located at the core of the logic of controlling genetic risk. That is, beyond merely following and executing doctor’s orders, they are generally deemed as responsible for deciding whether to consume preventative healthcare and to what extent based on the genetic information/counselling offered, as well as the possibility of choice of a genetic ‘future’. Thus, the BRCA mutation becomes ‘not only central to the political economy of hope but takes on a more materialist nature as it becomes as embodied practice that moves in and beyond the the clinic’ (Therond et al., Citation2020, p. 449). The primary assumption here is that with sufficient medical data and lab results, individuals are able to take the rational course of action when navigating around the market for prevention (Kerr, Citation2004). For example, Schneider-Kamp and Askegaard (Citation2021, p. 419) explore how consumers navigate ‘the liminal space between expert authority and consumer autonomy’. They highlight the intricate connections between consumer choice, consumer empowerment, and consumer resistance in healthcare. Their study uncovers how different healthcare discourses (commercial and public) bring into being self-disciplined consumers.

The responsibilisation (Foucault, Citation2008; Giesler & Veresiu, Citation2014) of at-genetic-risk individuals yields important implications for the market of healthcare prevention, as it is geared towards the control of degeneracy. We use the term ‘responsibilisation’ to refer to the transfer of responsibility from the state to the individual under the banner of freedom of choice (Foucault, Citation2008; Garland, Citation1996; Shamir, Citation2008). Within this study, we take a broadly constructionist stance to unpack the processes that lead to the responsibilisation of (risky) bodies-in-transition vis-à-vis the market of prevention. Previous consumer research has drawn on cultural perspectives on risk, and particularly the work of Deborah Lupton, to investigate the (risky) body-in-transition, such as the influence of restitutive narrative in breast cancer screening and treatment (Wong & King, Citation2008), consumer choice in healthcare and its ambivalent role in consumer empowerment (Schneider-Kamp & Askegaard, Citation2020), and the construction of health risk in natural childbirth communities (Thompson, Citation2005). Our context of study focuses on genetic risk. In particular, we focus on how the metaphorical formulations surrounding the genetic risk narrative shape the (risky) body-in-transition experiences as lived. We detail the methodology that guides our inquiry next.

Methodology

In order to explore the role of metaphorical formulations in shaping the experiences of bodies-in-transition vis-à-vis the market for prevention, we examine the narratives of women who are at-genetic-risk for breast and ovarian cancers. Our focus on hereditary breast and ovarian cancers lead us to focus primarily on a specific set of genes labelled the BRCA genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2), which are associated with an increased risk of female breast and ovarian cancer.

We draw our data from two sources. Firstly, we focus on a highly influential op-ed published by Angelina Jolie, in The New York Times. Secondly, we extract data from at-genetic-risk women’s interaction in a biosocial community called FORCE, which is predominantly US-based.

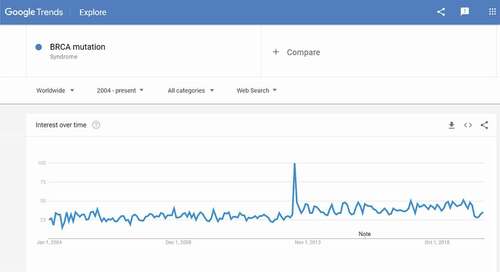

The op-ed from the American actress, film director, screenwriter, and author Angelina Jolie, was published in The New York Times on 14 May 2013, under the headline ‘My Medical Choice’. In it, Angeline Jolie revealed her decision to undertake a double mastectomy following her diagnosis as a faulty gene carrier. shows a significant peak in Google searches of the term ‘BRCA mutation’ in May 2013, directly after the publication of the story in The New York Times. The piece had a huge impact, which came after to be known as ‘The Angelina Effect’ following this term’s usage on the cover of Time Magazine, on 27 May 2013. ‘The Angelina Effect’ was initially used to describe the ‘cultural and medical earthquake’ caused by the star’s revelation. The term has subsequently been used in several epidemiological studies to explain how the frequency of testing for the BRCA gene had approximately doubled in several countries including the UK, Australia and Canada, following the publication of the letter (CBC News, Citation2013; Evans et al., Citation2014; Hagan, Citation2013).

Figure 1. Evolution of interest overtime for the key word ‘BRCA mutation’ – Worldwide.

The second tranche of data we analyse was extracted from at-genetic-risk women’s interactions in an online biosocial community FORCE (Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered). The community also includes women with a strong family history of cancer (but have either not been diagnosed with the faulty gene yet, or tested negative), as well as women who have some other predisposing factors. The community is predominantly US-based. FORCE is a national non-profit organisation in the USA devoted to hereditary breast and ovarian cancers, and was created in 1999. The organisation is involved in support, education, advocacy, awareness, and research specific to genetic propensity for breast and ovarian cancers. We consider FORCE as a ‘biosocial community’ (Rabinow, Citation1992), rather than a medical support group, as it caters to ‘pre-ill’ individuals diagnosed with higher susceptibility to a disease they do not yet have. Rabinow (Citation1992) envisaged that such groups would form around ‘new truths’ produced by the Human Genome Project and outlined the requirements for such movements to materialise. These requirements included the organisation of efforts around specific DNA mutations and the mobilisation of genetic experts, medical specialists, laboratories, diagnostic technologies, narratives, and support groups. Collectively these features allow previvors to ‘understand’ and deal with an almost determined fate of disease development caused by that mutation (Pender, Citation2012).

From a methodological point of view, FORCE constitutes an online assemblage as it operates at ‘the interface of geographical, regional, temporal, linguistic and other boundaries and create the context within which users interact with multiple audiences’ (Georgakopoulou & Spilioti, Citation2016, p. 323). All the extracts copied in this paper from the message board are the property of FORCE (Copyright © FORCE-Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered, Inc., Tampa, Florida. All rights reserved). The researchers, however, obtained permission to use the data for academic purposes from the executive director and founder of FORCE.

Our data sampling followed a very similar method to that elaborated by Holtz et al. (Citation2012). We started by identifying a forum to focus on our data collection. We decided to retrieve our dataset from the ‘young previvors’ forum. There were two main reasons for this choice: first, the title of the forum reserved it to the category of interest in the present research, ie. Previvors. Second, the ‘young previvors’ forum was the most popular forum after the ‘main’ forum in terms of number of topics, posts and replies, which was a sign of a good level of interaction between the participants. We copied the data from the forum’s archives, starting the selection from the beginning of the ‘young previvors’ forum, September 2008; and finishing it in February 2015.Footnote5 We excluded the threads within the last six months prior to the data collection, in order to have well-advanced narratives with sufficient interactions. We excluded all posts that had less than 20 replies in order to focus on rich conversations with an adequate level of interaction, which narrowed down the selection to a relevant corpus of 49 threads from the forum, and a total of 1387 posts.

Analytical procedure

In our analysis, we illustrate our findings by analysing excerpts from the threads from FORCE’s message board. Considering the sensitivity of the research topic, and fully recognising the position of extreme anxiety from which many must contribute, the forum participants’ profiles are completely anonymised, and we assigned pseudonyms rather than use the virtual names from the forum. We treat virtual usernames and pseudonyms with the same respect as a person’s real name, in order to prevent the risks related to the traceability of quotes online and their association with participants’ virtual identity. Particular precautions were taken to reduce the level of risk and safeguard the confidentiality of data. As suggested by the Ethics Guidelines for internet-mediated Research (British Psychological Society, Citation2017), specific strategies to ensure maximal anonymisation have been implemented, such as paraphrasing or combining traceable quotes after the data analysis stage. This helps reduce significantly the risk of traceability of quotes online, and safeguards the confidentiality of data.

Drawing on insights from discursive psychology (Potter & Wetherell, Citation1987; Wetherell, Citation1998), we analyse the speech at the interactional level, and connect it to wider considerations of the social, cultural and historical contexts. We start by identifying the key metaphorical domains used within our dataset in relation to the body-in-transition. We delineate three central metaphorical domains: the container, the omnipresent danger, and the battle and journey. We then investigate the functions of metaphorical formulations within their context of use, and then connect these to the wider contexts. The analysis was an iterative process moving between the data, the social cultural and historical contexts, and linguistics foundations around metaphorical formulations. We present our findings next.

Analysis – metaphors, bodies-in-transition, and responsibilities

We organise our analysis as follows. The first part is dedicated to metaphors of control, with a particular focus on the metaphor of ‘carriage’ and how it frames the BRCA subject as a container. The second part discusses metaphors of omnipresent danger and their effects on destabilising the body. The third part focuses on metaphors of battle and journey, and how they travel from cancerous to pre-cancerous bodies through the geneticisation discourse. We find that these metaphors shape and facilitate not only our informants’ experiences of their (risky) body-in-transition, but also their perceived responsibilities towards engaging with preventative healthcare consumption.

The body-in-transition as a container of a ticking time bomb

I agree with you and Pamela. It is hard to relate to our families and friends sometimes. I have some pretty good days; then I have days when the “tear attacks” come out of nowhere and I can’t stop crying. I think that’s just from holding it in for far too long, trying to keep myself together. People think it should not be that upsetting to know you’re a carrier, but I feel like a ticking time bomb. My fear is not if I’ll get BC, it’s when I’ll get it, it’s always been my biggest fear. I realised not long ago that I’m exactly the same age my aunt was when she died and my kids are the same age as my cousins were then … . and that really shook me up. I just take it one day at a time and I’m so grateful for this group! (emphasis added) Kim – FORCE forum

I have always told them [the children] not to worry, but the truth is I carry a “faulty” gene, BRCA1, which sharply increases my risk of developing breast cancer and ovarian cancer. (emphasis added) Angelina Jolie – New York Times op-ed

Hi! I also have a strong family history of breast cancer (my mother, maternal aunts (two), maternal grandmother, and maternal great-aunt). My mother and I have tested negative for BRCA mutation. We likely have another unidentified mutation. I understand how hard it can be to decide where to go from here. (emphasis added) Tatianna – FORCE forum

In extract (1), Kim describes how being BRCA positive affects her relationship with her relatives and her fears about being sometimes misunderstood. She is thirty-six years old and has recently received her screening results stating that she is BRCA1 positive. Kim has a strong family history as well but is still hesitant as to whether she should undertake the preventive surgery.

There are several interesting metaphorical formulations in this extract. The first formulation is a pervasive one within biomedical discourses, which yields important implications for consumption practices in the market for prevention: the metaphor of carriage. The formulation ‘carrying faulty genes’ is typical within the genetics discourse, and its usage was widespread across our dataset. For instance, in extract (2), the actress Angelina Jolie positions herself as having a sense of self with regards to the faulty parts within her body in her usage of ‘I carry’. This formulation entails a sense of responsibility for the need to act upon this deficiency. In contrast, she could have used, for instance, ‘I have inherited’, which would have completely reconfigured the attribution of blame. It would have located it within the meaning of inheritance, therefore blaming bad luck or ancestors. As Pomerantz (Citation1978, p. 119) argues, part of the business of blaming involves ‘treating an event, e.g. an “unhappy incident”, as a consequent event in a series. An antecedent action, one which is intendedly linked with the “unhappy incident”, is referenced. The actor of the antecedent action has the status of a candidate blamed party’. The ‘unhappy incident’ (developing breast cancer) becomes a product or a consequence of the embodiment of the subject positionFootnote6 ‘carrier’. This framing of the causal link between the ‘unhappy incident’ and the subject position ‘carrier’ prompts the individual to engage with the market for prevention, such as undertaking genetic/diagnostic testing and/or a preventive surgery.

The BRCA positive individual as a ‘carrier’ is part of the metaphorical system: ‘disease as a possession’. Within this metaphorical system, people catch, pick up, get, have, bring, acquire or contract illnesses (Wallis & Nerlich, Citation2005). Historically, the metaphor of carriage has been associated with infectious diseases and infected bodies within biomedical discourses. Disease as possession is one of the most common metaphorical systems here in both expert and lay speeches. For example, Wallis and Nerlich (Citation2005) describe how the metaphor of HIV/AIDS as a ‘sin’ has been deployed to attribute causality of the infection (divine judgement), moral construction of the affected body (sinner), as well as relevant prescriptive practices (such as repentance, abstinence, and moral education). It is, however, important to note that this metaphorical system does not refer to a passive action – instead, it entails a sense of agency. The carrier catches the infection from another infected body and becomes a host themselves. That is, people can also carry, give or pass on the infection to others (cf. Siegel et al., Citation2007). They morph from being a ‘recipient’ to a ‘container’, and to a ‘transmitter’ of the agent causing the disease.

In this case, the body-in-transition shifts from being qualified as a passive entity that is a victim of the infectious agent, to an active agent who is accountable for the survival and the movement of the infectious agent. ‘Disease as a possession’ emphasises individual responsibility, as the affected person becomes an active agent in her own illness (Beck-Gernsheim, Citation2000; Douglas, Citation1992; Lupton, Citation2012; Peterson & Lupton, Citation1996). The agent is then held accountable for contracting the infection, hosting it, and finally transmitting it into a ‘victim’ that becomes subsequently another host within the narrative. When a ‘victim’ morphs into a ‘carrier’, they become a source of danger or threat, rather than an object of compassion (Wallis & Nerlich, Citation2005). The metaphor of carriage thus conveys a strong ideological meaning and performs critical rhetorical functions (Derrida, Citation1982), by locating the subject’s responsibility in engaging in the market for prevention to contain the source of danger or threat.

Moreover, the discourses of survivorship and previvorship in breast cancer put an additional layer of pressure on women to follow certain practices to preserve the body-in-transition. The movement of subject positions from ‘patient’ to ‘survivor’ and ‘carrier’, and to ‘previvor’ generates moral implications as well. The celebration of the preservation of the body-in-transition entails additional moral expectations for previvors to follow certain practices and make ‘informed’, ‘rational’ decisions. These moral expectations are accomplished through an engagement with the market for prevention to be a good genetic citizen, including: education on risk and risk prevention (through patient leaflets, visits to doctors or geneticists, online searches, and so on), rigorous testing (such as genetic testing, but also mammography, breast self-check, and so on), preventive surgery, and reconstructive surgery.

Genetic citizenship (Kerr et al., Citation2009; Petryna, Citation2004; Rose & Novas, Citation2005) refers to a new kind of citizenship, which emerged with the rapid progress of biomedical research, science of genetics, and biotechnology. This citizenship is shaped by new subjectivities, politics, and ethics (Rose & Novas, Citation2005). Good genetic citizens are ‘courageous, self-responsible, high-order citizens’ (King, Citation2004, p. 489). Good genetic citizens engage with the market for prevention in order to preserve their (risky) bodies-in-transition, as prescribed by biomedical rationalities. Under this conceptualisation, the at-genetic risk subject becomes: ‘genetic citizens, fighting for specific rights while shouldering and contesting concomitant duties and obligations … [involving] social practices and power relations that cut across online and off-line worlds to co-produce genetic knowledge and genetic citizenship in multiple contexts’ (Shaffer et al., Citation2008, p. 145). In a sense, they represent a by-product of responsibilisation (Foucault, Citation2008; Giesler & Veresiu, Citation2014), as a central process to neoliberal governance.Footnote7 As W. Brown (Citation2006, p. 694) put it, responsibilisation in biomedical discourses ‘entails a host of policies that figure and produce citizens as individual entrepreneurs and consumers whose moral autonomy is measured by their capacity for “self-care” – their ability to provide for their own needs and service their own ambitions, whether as welfare recipients, medical patients, consumers of pharmaceuticals, university students, or workers in ephemeral occupations’. The market for prevention and related consumption practices become key socialisation agents shaping the meanings associated with the subject position ‘carrier’. They become both a right and duty attached to the responsibilities of the carrier.

Taken together, the subject position ‘carrier’ represents a stabilised role through processes of iterations of biomedical models (Derrida, Citation1972, Citation1988). The act of consumption results from the temporary stabilisation of this subject position, as it makes a set of rights, duties, rationalities, and practices available for the individuals concerned. Therefore, in order to sustain their category membership within the collective, women with the BRCA gene are compelled to fulfil their duties as a good genetic citizen through engaging with or buying into consumption practices in the market for prevention.

The second noteworthy metaphorical formulation from extract (1) is the gene-as-bomb metaphor in ‘People think it shouldn’t be that upsetting to know you’re a carrier, but I feel like a ticking time bomb’ (emphasis added). Alongside the pervasive gene-as-disease metaphor, the gene-as-bomb was another deterministic metaphorical formulation common in our dataset. This formulation assumes a strong causal link between gene and disease, and suggests that once a genetic mutation has been triggered, the result is inevitable. The formulation of gene-as-bomb is vivid and accentuates the destructive nature of the result – the result being the occurrence of cancer. The visual (metaphorical) representation of cancer as a result of a bomb explosion, emphasises the intense nature of cancer narratives. The representation of the BRCA genes as a ticking-time-bomb signals an inevitable explosion unleashing the ‘deadly’ cancer. Kim stressed this aspect in ‘My fear is not if I’ll get BC, it’s when I’ll get it, it’s always been my biggest fear’ (emphasis added). The use of ‘when’ for the script formulation suggests the quasi-certain occurrence of the condition, and therefore a different approach to the course of action of practices to preserve the body. As the outcome (occurrence of cancer) is depicted as inevitable, the engagement with the market for prevention are assimilated at the same level of urgency as the curative ones, and the at-genetic-risk body is formulated as quasi-ill, or ill in its own way. Another notable aspect is the use of the modal verb ‘will’. Kim’s formulation combining a strong modal verb ‘will’, which in conjunction with the scripting device ‘when’, signals the quasi-certainty of the occurrence of the negative event; therefore, presenting the urgency of the subsequent preventive practices as rational and unquestionable. In other instances, within our data, weaker modal verbs were used such as ‘should’ and ‘might’, where the speaker was contributing in advice-giving, and shaping the decision-making process, while still attributing the responsibility of the final decision to the carrier of the faulty gene. The arrangement of the scripting device ‘when’ alongside the strong model verb ‘will’ therefore functions as a strategy to legitimise certain practices and emphasise the responsibility of the ‘carrier’ to fulfil her duties as a good genetic citizen by consuming the market for prevention. Provided the sense of urgency experienced by the risky body-in-transition, the forum participants described engaging in more frequent check-ups (such as mammography and breast self-check), as well as making arrangements for preventive mastectomy.

Extract (3) represents an example of the extension of the metaphor of carriage to other consumption practices. Tatianna has a strong family history of breast cancer. However, both she and her mother’s test results were negative for the BRCA gene mutation. There is also, in this extract, the use of passivisation in ‘have tested negative’. The use of the passive form ‘have tested’ is yet again another pervasive formulation within the current lay population healthcare speech. It represents a shortening of ‘I have been tested and the result is negative’. Neither Tatianna, nor her mother have performed the genetic test themselves. They went through a process of testing and getting results by agents that are deleted within the formulation ‘I have tested negative’. Even in the case of self-testing, the agency is still dispersed: located within the interaction is the testing device, the instructions leaflet, the patient’s education process, and so on; but that would be a completely different case and analysis. This specific formulation (‘have tested’) makes it more likely to locate the blame entirely within the ‘tested’ subject, rather than attributing part of the blame to the agent performing the test. Within the BRCA gene discourse, individuals need to be ‘tested’ when suspected of being a potential ‘carrier’ of a genetic mutation. The initiation of the engagement with the market for preventive solutions starts with diagnostic biotechnologies such as genetic testing.

In the extract of interest, the passivisation functions as a device to turn a process into an entity that is essential to decision-making. The transfer of information, which constitutes the process at the centre of this utterance, is presented as a necessary factor for Tatiana to make an ‘informed’ decision with regards to her risk. In addition, the passivisation functions as a device to delete the agent responsible for the diagnosis procedure and quantification of risk, and to shift the focus on the outcome of diagnosis (negative test) affecting the choice-making rather than a specific agent to be blamed. Thus, passivisation performs critical ideological functions such as deleting agency and reifying process (Fowler, Citation1991; Fowler et al., Citation1979).

Another notable element is that Tatiana translates her negative results for the BRCA mutation into the likelihood of the presence of other genetic mutations that haven’t been identified yet. She makes an implicit causal link between her strong family history of breast cancer, and the (‘likely’) presence of an unidentified mutation. Thus, Tatianna makes sense of her body-in-transition as genetically at-risk body. The negative results were made sense of as a limitation of the field, which transfers part of the blame to a knowledge gap. This has implications for the course of action of preventive consumption practices. The translation of negative results to an unidentified mutation implies more frequent consumption of diagnosis practices such as mammography or breast self-check, as well as the possible engagement with further preventive practices such as mastectomy.

The des/stabilisation of the body-in-transition through metaphors of omnipresent danger

I choose not to keep my story private because there are many women who do not know that they might be living under the shadow of cancer. (emphasis added) Angelina Jolie – New York Times op-ed

I find typing helps. I sort of doing my own little book of past and present type things combined with how I feel about things now and it is helping. I think it’s important for you to have time for yourself to think it through too, i have found going to the gym helps – I hadn’t been for years until recently and am a heavier weight than id like to be so I’m finding combining that with zoning out for a bit helps. It isn’t an easy path, and you won’t automatically wake up the next day knowing 100% what to do. But whatever you feel like on that day we are all here to help each other through it. Like I said if you want to chat, vent or have any questions my email is on last post. Shannah – FORCE forum

We found that the narratives of fear and hope were critical devices for driving engagements with the market for prevention.Footnote8 Fear was a dominant discourse within our dataset. For example, throughout the whole piece, Angelina Jolie appears to be legitimising the concerns about the risk associated with carrying the faulty BRCA gene, developing breast cancer, dying, and not being able to be there for her children. An example of a manifestation of fear within the narrative was the use of the metaphorical formulation ‘living under the shadow of cancer’ (emphasis added). The formulation ‘under his shadow’ can be understood as an instance of a dead metaphor through its ‘usure’ (Derrida, Citation1982). This idiomatic expression of ‘under his shadow’ can suggest a form of protection (or Divine Providence; ie. its original use in the Book of Lamentations), or a danger (through its movement within the healthcare discourse). The sense of danger inherent in the metaphor, ‘under his shadow’, emerges within the genetic reframing of cancer and implies a high causality between the disease and the faulty gene. It shapes the lived experience of the at-genetic-risk individuals by positioning cancer as almost inevitable and omnipresent.

As Fox (Citation2002, pp. 357–358) describes: ‘the cancerous (cancering) body: The body subjects itself to censorship, to moralistic outrage. It appraises itself: “this part is good, it can remain; this part is bad, it must be excised or burnt or poisoned or overcome by positive mental effort”. The body is conservative, it is suspicious of novelty, of otherness: it is a control freak because the worst consequence is to lose control’. The at-genetic-risk body as a ‘control freak’ is an effect of the iteration of narratives of illness (Derrida, Citation1972, Citation1988) that represent the disease as a loss of personal control. However, the effects of these narratives shift from the ill to the pre-ill body. The need to organise and control something frightening and chaotic stems from this sense of loss of control, which may be located in both the pre-cancerous (transitioning) body and the cancerous body. Thus, the body-in-transition ‘living under the shadow of cancer’ is suspicious of its parts ‘carrying’ the faulty genes, and needs to act in order to take back control. This necessitates healthcare/medical consumption that resembles those traditionally applied to the ill body.

Instances of hope were also present within Angelina Jolie’s letter – mainly when discussing the advances of biomedical sciences, whether it concerned preventive procedures such as double mastectomy or body enhancement through post-surgery breast reconstruction. For instance, when Angelina Jolie writes ‘I feel empowered that I made a strong choice that in no way diminishes my femininity’, her utterance performs two functions primarily. First, it links her feeling of empowerment to (1) the freedom of making a choice, and (2) the availability of strong options to choose from. It also connects the choice to a major construct that is associated with breast cancer treatment, which is the loss of perceived womanhood through the removal of breasts. In line with the survivorship discourse, as discussed in the previous section, her statement reinforces the view that breast cancer survivors’ bodies can mirror heteronormative images of the healthy body by making the ‘right’ choice in the market for prevention (eg. breast reconstruction surgery). However, the utterance shifts the argument and consumption focus in time and space, from the ill to the pre-ill body (eg. double mastectomy), which we explore in the next section when discussing metaphorical formulations that perform such spatiotemporal shifts.

There were therefore some obvious connections between the ‘need to take back control’ and the ‘feeling of empowerment’ throughout our dataset (such as in the quotes analysed in this section) – in the delicate dance of fear and hope narratives. The feeling of empowerment, or the creation of the subject position of the ‘empowered risky body’, is intertwined not only with the notion of freedom of choice, but also the freedom to take action (Shankar et al., Citation2006). Thus, the exercise of the freedom to choose becomes synonymous with individual autonomy (Schneider-Kamp & Askegaard, Citation2020). The promotion of values of freedom and the desire of autonomy facilitates the process of responsibilisation of bodies-in-transition to engage with the market for prevention.

Indeed, maintaining hope requires a set of strategies and an engagement with a set of healthcare market solutions. The narrative of ‘BRCA positive and positive’ (ie. testing positive for BRCA, yet maintaining in a positive mindset) across our dataset exemplifies such a mindset. In extract (5), Shannah describes the various strategies she is deploying to deal with her BRCA status and stay positive. Like many other women in the thread of discussion, Shannah is experiencing many challenges after being diagnosed as BRCA positive. It is apparent that Shannah has difficulties with deciding which course of action to undertake for preventive procedures. At the same time, she is worried about how her decision to undertake preventive procedures may impact her romantic relationship. Throughout the thread, Shannah describes various coping strategies such as maintaining diaries, physical activities, diagnostic procedures, food supplements, and prophylactic surgery. When looking closely at the way Shannah performs her descriptions, an aspect that stands out is the frequent use of first-person formulations. Whether it is in ‘I find typing helps’, ‘I sort of doing my own little book … ’., or ‘I have found going to the gym … ’, the description of the various strategies involves the use of the pronoun ‘I’ to signal how she keeps her sense of wellbeing under control.

In addition, Shannah discusses various strategies related to the preservation of the body – ‘I have found going to the gym helps – I hadn’t been for years until recently and am a heavier weight than id like to be so I’m finding combining that with zoning out for a bit helps’. These strategies of bodily preservation consist of physical activities, and Shannah links these to her overall coping mechanisms with her BRCA diagnosis. In ‘I hadn’t been for years until recently and am a heavier weight than id like to be’, the indexicality of morality operates as a mean of ‘pleading guilty’ for Shannah. She makes a causal link between ‘heavier weight’ and the lack of physical activity. This is performed by the combination of the use of the first-person pronoun ‘I’ with the coordinating conjunction ‘and’. In this context, the coordinating conjunction ‘and’ does not only have an ordering function but also operates as a device to attribute causality, as Shannah attributes her ‘heavier weight’ to the fact that she hadn’t been to the gym for years. It seems that she is acknowledging the importance of going to the gym, and by the same token attributing the blame for this weight gain to her own negligence, emphasising the acceptance of herself as a responsible agent for the outcome of this particular condition. Through the acknowledgement, she presents herself as responsible and reflexive, as a consequence of her recent diagnosis.

Cancer as a battle vs. cancer as a journey

I definitely think that you should get genetic counselling and test as soon as possible. It will give you a lot of peace of mind and knowledge. I don’t mean to quote from ‘Schoolhouse Rock,’ but ‘Knowledge IS power!’

However, I do believe you are taking the right steps anyway! Ovarian cancer is nothing to mess around with and it sounds like it’s just rampant in your family. I am BRCA1 positive and was diagnosed with breast cancer in April. I’ll be getting a preventative hysterectomy later this year as well and I have the same fears as you do: that I’ll end up being some sweaty, angry, crazy person that my son doesn’t want to be around. But from what I have read, while there is an adjustment period, it does get better and they may be able to put you on some low-dose hormone therapy for a little while if necessary to get you over the worst of it. (emphasis added) Maureen – FORCE forum

MY MOTHER fought cancer for almost a decade and died at 56. (capitalisation in original) Angelina Jolie – New York Times op-ed

In extract (6), Maureen strongly recommends genetic testing to one of her fellow forum contributors, presenting it as an instrument of knowledge and reinforcing her recommendation by stating, ‘Knowledge IS power!’. Maureen is planning to have a preventive hysterectomy later in the year, even though she shares the same fears as her fellow forum contributor – ending up being some ‘sweaty, angry, crazy person that my son doesn’t want to be around’. The latter statement highlights how the body-in-transition constantly grapples with the fear of increased health risks (such as those associated with surgery-induced menopause) if not ‘managed’ or ‘controlled’ adequately.

It is worth noting that one of the rhetoric devices Maureen uses to recommend genetic testing is the metaphor of ‘rampage’, in her comment ‘Ovarian cancer is nothing to mess around with and it sounds like it’s just rampant in your family’ (emphasis added). Cancer’s spread in the clinical discourse is frequently talked about in terms of movement. Cancer cells are said to be ‘invasive’. They ‘colonise’ the body from the original tumour to far sites. In Semino et al. (Citation2004) study about cancer metaphors, for example, oncologists were using combinations of literal references with metaphorical formulations to describe cancer ‘entering’ the bloodstream. They also refer to parts of the body as ‘sites’ or ‘areas’, or cancer getting ‘dotted around’ in the skeleton and ‘lodging itself’ in the patient’s bones.

With this in mind, the literature on metaphors and cancer tends to delineate two distinct domains that shape cancer metaphors: the domain of fighting, war and battlefield (e.g. Sontag, Citation1978), and the domains of journey and travel (e.g. Semino et al., Citation2015). The domain of battle ranges from labelling the affected individual as a survivor to generating language around cancer treatment. In this domain, the metaphorical framing of the diagnosis is often fatalistic, which in turn shapes how treatment is articulated as fighting against a deadly, insidious enemy (Sontag, Citation1978). This fight is ought to be won by any means possible provided the high societal value placed on ‘health’ (Beck-Gernsheim, Citation2000). Examples of the metaphors of battle within cancer treatment include: ‘bombarding’ areas of the body with radiation, or treatment aiming at ‘killing’ cancer cells. With similarities to linguistic formulations in the HIV/AIDS discourse, metaphors in breast cancer possess an overtly politicised character. The metaphors of war profoundly structure the set of preventive practices recommended to deal with the illness. It shapes the identity of the patient who aspires to become a cancer survivor (or a previvor of its predisposition), and who dares to consume more intrusive healthcare prevention such as pre-emptive surgeries to keep the illness/pre-illness under control. As Annas (Citation1995, p. 68) states: ‘military thinking concentrates on the physical, sees control as central, and encourages the expenditure of massive [available market] resources to achieve dominance’.

Cancer is also mapped as a moving entity in ‘journey’ metaphors. This entity travels within the body from one location to another before spreading to its entirety. It also maps other temporal aspects of movement such as the speed of growth/movement or remission, as well ‘pauses’ in the journey, and so on. Metaphors of war and battle are pervasive within our dataset. For instance, Angelina Jolie started her op-ed in The New York Times ‘MY MOTHER fought cancer for almost a decade and died at 56ʹ (capitalisation in original) (extract 7). Starting with a ‘lost’ battle already positions cancer as a strong ‘enemy’, and calls for engaging with the market for prevention to defeat it. It paved the way for Angelina Jolie to narrate, explain, and legitimise her ‘medical choice’ (the title of her letter).

The metaphor of cancer as ‘rampant’, from extract (6), conceptualises it within both domains: war and journey. A potential final outcome of rampage is the sudden appearance or onset. The word rampant originates from the old French ‘ramper’, which means ‘to crawl’, and describes an insidious movement. Its use in the French language is common within the animal and vegetal realm to describe an insidious crawling movement. ‘Rampant’ metaphors are common in the French military discourse as well, where it describes an insidious movement of the body to surprise the enemy. Whereas in the French language, the word ‘rampant’ has neutral prosody, its use in the English language has negative prosody to describe a movement that is unrestrained, violent, and explosive (Koteyoke et al., Citation2008). Here, the metaphor of rampage goes beyond its understanding as an insidious movement, to illustrate a much more menacing dimension in the domains of both war and journey. Thus, this metaphor entails an inherent loss of control, which contributes to the uncertainties, fears, and self-doubt of the body-in-transition.

The ‘rampage’ of cancer in the pre-cancerous body is performed through the transmission of the faulty genes. While the journey metaphor of cancer traditionally occurs within the body infected by spreading the disease/infection from an organ to another, the genetic narrative shifts the travel through space. By this, we mean how the faulty genes move from one body to another within the family. The faulty genes, in this case, are framed as temporally located within the body’s lifetime, from the onset of the disease. Thus, the rampage occurs when the ‘bad’ copies of the gene ‘travel’ from a body to another through heredity. The genetics narrative also shifts the journey of cancerous cells in time, as the genes travel from one generation to another.

Taken together, the displacement of meaning of the ‘rampage’ metaphor (Derrida, Citation1978) from the ill (cancerous) to the pre-ill (cancer-prone) body organises our thinking around how cancerous cells may travel through the body-in-transition (in terms of journey) and how they should be fought against (in terms of war). The genetic discourse performs a spatiotemporal shift of patients’ rights and duties from the cancerous/ill body to the carrier of the ‘cancer-gene’/pre-ill body. In this case, the set of patients’ rights and duties (e.g. right to access the market for preventive surgery or reconstructive surgery, as well as the right to ‘choice’, but also the duty to preserve the body to engage with these preventive solutions) that are traditionally associated with the ‘ill’ category are shifted to the ‘pre-ill’, urging the ‘pre-ill’ to engage with the market for prevention to ‘kill’ cancer before it appears, takes control of, and overwhelms their genetically risky body-in-transition.

Discussion

Our findings on biomedical metaphors add to prior consumer research on the body-in-transition that has been largely examined in contexts such as extreme sports (Arnould & Price, Citation1993; Scott et al., Citation2017), plastic surgery (Askegaard et al., Citation2002; Schouten, Citation1991) and personal/body adornment (Roux & Belk, Citation2019; Ruvio & Belk, Citation2018). This stream of literature has tended to frame the body-in-transition as relatively risk-free, voluntary and rewarding, and privilege concepts such as ‘control’ and/or ‘consumer sovereignty’ to achieve positive self-transformation. Importantly, it generally conceptualises risk-taking as something exciting or thrilling, rather than something that they struggle to cope with. Our research investigation of at-genetic-risk bodies contributes to an enhanced contextually nuanced understanding of the involuntary risk management side of the body-in-transition and how consumers cope with it. Beyond social acceptance and pain (Roux & Belk, Citation2019; Scott et al., Citation2017), we show how risk-taking may also be bound up with the lived experience of ‘losing control’ and the role of consumption in preventing the body-in-transition from getting out of control.

We highlight how claiming membership in the previvor category prompts women with the BRCA gene mutation to subscribe to a set of rights and duties that shape their engagement and coping strategies in the market for prevention. That is, while the BRCA gene mutation destabilises the body by locating it in ‘a liminal category of wellness: neither actually ill (yet) nor fully well’ (Lupton, Citation2012, p. 17), the previvor category re-stabilises it by inferring a set of rights and duties geared to manage/control/cope with the genetic risks inherent in the seemingly healthy/cancerous bodies. Some of the essential rights and duties identified in the present study include consuming healthcare-related education to make an informed choice for risk management, self-care practices to maintain a sense of wellbeing (e.g. dieting, going to gym), and the market for preventive solutions (e.g. diagnosis procedures, double mastectomy and the aesthetic reconstructive surgery) to be a good genetic citizen.

In particular, our findings shed light on the effects of metaphors (Belk et al., Citation1996; S. Brown, Citation1994; S. Brown & Wijland, Citation2018; Cornelissen, Citation2003; Hirschman, Citation2007; Zaltman & Zaltman, Citation2008) – biomedical metaphors around genetic risk in this case – in shaping the lived experiences of the body-in-transition or what Askegaard et al. (Citation2002, p. 811) call ‘tyranny of management’. We discover how the ‘usure’ (Derrida, Citation1982; Derrida & Moore, Citation1974) of certain metaphors renders their ideological, performative functions hard to uncover. The taken-for-granted nature of biomedical metaphors that we outlined in the findings function to attribute responsibility(ies) of managing the faulty genes to the at-genetic-risk subjects and facilitate the ways in which they cope with the risky body-in-transition. Indeed, we note that when using specific metaphorical formulations, such as the carriage for instance, individuals simultaneously reinforce and reproduce the specific ideologies and rhetoric functions inherent in the metaphors (e.g. the agentic expression of ‘I carry’ as in being responsible for the faulty gene). We argue that through the utterance of the biomedical metaphors as noted in this study (e.g. carrier, rampage, ticking-time-bomb etc.), the women in our dataset are indexicating particular commonsensical ideologies (e.g. responsibility, urgency, danger, etc.) to shape the moral locations (i.e. what to do and how to feel and cope with the existential threats of a cancerous body) of their subject positions.

With this in mind, our findings show that the consumption of preventive healthcare is part of the ideological system to fulfil the set of rights and duties attached to each moral location. For example, metaphors of carriage, control, military, and journey function as rhetorical devices that frame subjectivities and their moralities in a specific way, and thus shape our informants’ engagement in the market for prevention to not only ‘prevent’ but also ‘contain’ (anticipated) diseases. As such, the consumption of prevention becomes constitutive of the at-genetic risk subjectivity, and not just an outcome of diagnosis. By engaging with the market for prevention, the subject position ‘previvor’ becomes stabilised (although the stabilisation may only be temporal). In sum, the metaphorical formulations, as examined in this study, shape our informants’ lived experiences and consumer practices of managing/preserving/coping with their risky body-in-transition through their inscription within the ephemeral subject positions. Failure to consume the prescribed practices of prevention and cope with the mental stress and risks of having a ‘faulty’ gene can destabilise one’s sense of membership to the previvor category, causing existential anguish.

Following this thread of our research findings, we conclude that the previvor category facilitated by a range of biomedical metaphors, represents the ephemeral stabilised result of the interaction of various subjective positions, multiple discourses around perceived rights and duties, and the associated consumer coping practices. The metaphors can compete to be realised and actualised in managing the at-genetic-risk body-in-transition. For instance, ‘controlling’ and ‘containing’ the disease are implicated in the carrier metaphor as appropriate coping strategies to tackle the potential or perceived inevitable spread of the disease when considering ways of engaging with preventive healthcare consumption. These coping strategies can be time-bound and carry a sense of urgency when they are further reinforced by metaphorical formulations such as ‘ticking time bomb’ and omnipresent danger. This puts an additional time pressure on the body-in-transition to comply with the various rights and duties individuals must fulfil to be a previvor and take back control of their at-genetic-risk transitioning body.

Moreover, our findings underlined the connection between the ‘need to take back control’ and the ‘feeling of empowerment’ (Schneider-Kamp & Askegaard, Citation2020; Shankar et al., Citation2006). We discussed in our analysis section how the promotion of values of freedom and the desire of autonomy facilitates the process of responsibilisation. Indeed, and as Merry (Citation2009, p. 403) put it: ‘a responsibilised society does not see individuals as socially situated but as autonomous actors making choices that determine their lives’. Through a Foucauldian lens, neoliberal empowerment can be understood as a ‘liberating responsibilisation’ (responsabilisation libératrice) (Hache, Citation2007). The discourse of empowerment enables at-genetic-risk subjects to be liberated from the medical gaze by their freedom to make informed choices, and also the capacity (through education) to read and make sense of genetic information to cope with and be in control of their bodies-in-transition. However, this discourse also has an effect on disciplining at-genetic-risk subjects in terms of their relationship with their bodies and the defectuous organs; through the delineation of available consumption practices to preserve their bodies and cope with the inherent risks, and the knowledge systems surrounding these, as well as the framing of what constitutes a rational/responsible behaviour. What is happening here is a fetishisation of freedom and control, performed by the shaping of risky bodies-in-transition into consumers of prevention. As Rose (Citation1999, p. 262) stated, the at-genetic-risk subject becomes ‘attached to the project of freedom’; and accomplishes this project through consumption strategies of control. The discourse of empowerment – through the promotion of values of education, choice, and autonomy (Schneider-Kamp & Askegaard, Citation2020) – acts as a channel for ‘mainstreaming biomedical rationalities and neoliberal notions of responsibilisation and self-care’ (Beckmann, Citation2013, p. 171). Thus, we argue that the subject position ‘empowered’ is critical to the shaping of the consumption/coping practices of the risky body-in-transition.

Taken together, our study adopted a linguistically-driven approach through the lens of metaphors (Derrida, Citation1982) to better understand consumers’ coping, struggles and uncertainties around managing their risky body-in-transition – a phenomenon that is rarely foregrounded as the focus of investigation in prior consumer research. Our study context also offers important managerial implications for preventative healthcare practitioners and consultants to better appreciate the impact of the often taken-for-granted medical metaphors on their patients’ and clients’ sense of wellbeing and ways of coping with existential uncertainties. We contend that by being aware of the prescribed sets of rights and duties attached to the metaphors outlined in this study, the market for healthcare prevention can develop more compassionate encounters with their ‘customers’ and communicate their offerings in a more inclusive, diverse ways of framing previvorship.

Conclusion

Our research has set out to complement extant consumer research on the body-in-transition by providing a contextually nuanced account of at-genetic-risk bodies through the lens of metaphorical formulations. Metaphors have long been noted to generate crucial insights into marketing and consumer discourses and practices (Belk et al., Citation1996; S. Brown & Wijland, Citation2018; Cornelissen, Citation2003; O’Malley et al., Citation2008; Zaltman & Zaltman, Citation2008). We show how the often taken for granted biomedical metaphors hold important ideological and rhetorical functions in shaping the lived experiences of the body-in-transition vis-à-vis the market for prevention. Importantly, we highlight how the metaphors of container/ticking-time-bomb, omnipresent danger and battle and journey reconfigure the rights and duties of managing/coping with the (risky) body-in-transition in the healthcare prevention marketplace. Despite the felt tensions and struggles to contain and fight the (anticipated) diseases, it is through the fulfilment of these rights and duties that one may be regarded as a good genetic citizen and claim the membership of being a BRCA previvor. The at-genetic-risk bodies and their participation in the market for prevention are as much about acknowledging ‘consumer sovereignty’ (sense of being in control) as questioning how ‘consumer sovereignty’ is limited by biomedical and market narratives (sense of losing control). As Askegaard et al. (Citation2002, p. 811) noted, often under technological/medical advances, ‘the consumer’s body is liberated from the tyranny of fate, only to be submitted to the tyranny of management’. Future research can take a longitudinal approach to further examine the developmental process of the interplay and how consumers and the marketplace may compete and clash in managing the (risky) body consumed.

In addition, future research could also explore the individualisation and collectivisation dynamics of the organisation of bodies-in-transition in collectives – such as in the case of social movements. For example, Cheded and Hopkinson (Citation2021) explore how the individualisation and collectivisation dynamics in breast cancer social movement narratives participate in both stabilising and disrupting political realities. They argue are that these narratives hold the dual role of mobilising collective action, and disciplining biological citizens. Future research could explore these dynamics in different contexts, in order to document the relationship between collective action and consumer empowerment for bodies-in-transition.

Finally, our findings also suggest how the perceived rights and duties in being a good genetic citizen can frame the ways in which individuals engage in coping strategies such as typing, going to the gym, and accessing the market for preventive/reconstructive surgery, education on risk prevention and so forth. We encourage future studies to investigate how our findings might translate to other risky consumption scenarios. For example, it will be particularly interesting to study the perceived rights and duties of recovering addicts to drugs, smoking and/or alcohol. How do these perceived rights and duties drive their coping strategies during their addiction treatments? Insights into such questions can further advance our understanding of the risky body-in-transition, especially in terms of the interplay between the desired and undesired selves (Liu & Hogg, Citation2017).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mohammed Cheded

Dr Mohammed Cheded is a Lecturer in Marketing at Lancaster University Management School. He is primarily interested in the sociological aspects of consumption, markets, gender, and health. His research takes an interdisciplinary perspective to focus on topics such as inequality, identity construction, and power relations.

Chihling Liu

Dr Chihling Liu is a Lecturer of Consumer Behaviour and Marketing in the Department of Marketing at Lancaster University Management School, UK. She obtained her PhD at Alliance Manchester Business School, UK. Her research activity is predominantly in the area of consumer culture theory, exploring the interrelationships between consumption, self and identity, with a specific focus on improving consumer welfare and subjective wellbeing.

Gillian Hopkinson

Gillian Hopkinson is a professor in Marketing at Lancaster University Management School. She has methodological interests in narratives and discourse which she applies primarily to analyse controversies in the food and grocery sectors. This work has been published in Management Journals such as Human Relations and Marketing Journals including Marketing Theory and Journal of Marketing Management.

Notes

1. According to the official website of ToughMudder.co.uk, Tough Mudder is ‘a series of obstacle and mud runs that will push your physical and mental limits’. The Tough Mudder event promises intense pain that is transforming, emphasising the body-in-transition that will lead to rebirth, personal growth and a new understanding of one’s body and its limits.

2. We develop a thorough analysis of the label ‘previvor’ throughout our investigation. The FORCE (the community we explore in our dataset) website defines the ‘previvor’ as ‘individuals who are survivors to a predisposition to cancer but who haven’t had the disease’ (emphasis added).

3. Without going into complex scientific details, inheriting a mutation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes is linked to an increased risk of female breast and ovarian cancers. BRCA is an acronym for BReast CAncer, and the genes are known as BReast CAncer 1 (BRCA1) and BReast CAncer 2 (BRCA2).

4. We stress that our commitment to conducting a social enquiry on genes does not mean that we discredit any natural dimension of the gene. Nonetheless, we hold that knowledge of genomics is embedded within the social, cultural and historical contexts of genetic discovery and cannot therefore be considered as irrefutable objective entities of nature (Kerr, Citation2004; Latour, Citation1987; Tutton, Citation2012). Our argument is not that genes do not have a very significant and, for many people, life-threatening role. Neither do we aim to diminish, in any way, the very real experiences and fears of those making decisions within the genetic knowledge available to them. Rather, our study aims to shed light on the role of genetic metaphors in shaping individual experiences vis-à-vis the market for prevention.

5. The dataset originated from the first author’s PhD thesis. No significant deviations were observed in the development of the forum narratives since the end of data collection.

6. Our usage of the term ‘subject position’ draws on positioning theory within discursive psychology (Davies & Harré, Citation1990). Within positioning theory, a ‘subject’ refers to ‘the series or conglomerate of positions, subject-positions, provisional and not necessarily indefeasible, in which a person is momentarily called by the discourses and the world he/she inhabits’ (Smith, Citation1988, p. xxxv).

7. Critics from the sociology of health and illness have long discussed the intimate connections between genetics’ focus on the notion of individual choice and the wider connections with neoliberal governance (see for example, Kerr, Citation2004; Rabinow, Citation1992; Rose, Citation2007; Tutton, Citation2016). For many of these critics, the focus on individual choice represents a device to attempt to delineate genetics from eugenics’ modes of intervention on reproduction as a matter of state interference and control.

8. The interplay between fear and hope in the narratives of the BRCA genes has implications beyond individual consumption experiences, to include the organisation of broader ‘patient organisations’ and wider activism. Due to the limited space and scope of this paper, we do not engage with these implications unfortunately – for an in-depth understanding of these matters, please see Gibbon (Citation2007), and Cheded and Hopkinson (Citation2021).

References

- Annas, G. (1995). Reframing the debate on health care reform by replacing our metaphors. In J. W. Glasser & R. P. Hamel (Eds.), Three realms of managed care: Societal, institutional, individual (pp. 67–75). Sheed & Ward.

- Arnould, E. J., & Price, L. (1993). River magic: Extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 24–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209331

- Askegaard, S., Gertsen, M. C., & Langer, R. (2002). The body consumed: Reflexivity and cosmetic surgery. Psychology & Marketing, 19(10), 793–812. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10038

- Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2000). Health and responsibility: From social change to technological change and vice versa. In B. Adam, U. Beck, & J. van Loon (Eds.), The risk society and beyond: Critical issues for social theory (pp. 122–135). SAGE Publications.

- Beckmann, N. (2013). Responding to medical crises: AIDS treatment, responsibilisation and the logic of choice. Anthropology & Medicine, 20(2), 160–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2013.800805

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

- Belk, R. W., Ger, G., & Askegaard, S. (1996). Metaphors of consumer desire. In K. Corfman & J. Lynch (Eds.), Advances in consumer research (Vol. XXIII, pp. 368–372). Association for Consumer Research.

- Belk, R. W., Ger, G., & Askegaard, S. (2003). The fire of desire: A multisited inquiry into consumer passion. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(3), 326–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/378613

- Billig, M., & MacMillan, K. (2005). Metaphor, idiom and ideology: The search for ‘no smoking guns’ across time. Discourse & Society, 16(4), 459–480. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926505053050

- British Psychological Society. (2017). Ethics guidelines for internet-mediated research. INF206/04.2017. Retrieved September, 2019, from www.bps.org.uk/publications/policy-and-guidelines/research-guidelines-policy-documents/researchguidelines-poli

- Brown, S. (1994). Marketing as multiplex: Screening postmodernism. European Journal of Marketing, 28(8/9), 27–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569410067631

- Brown, S., & Wijland, R. (2018). Figuratively speaking: Of metaphor, simile and metonoymy in marketing thought. European Journal of Marketing, 52(1/2), 328–347. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2017-0248

- Brown, W. (2006). American nightmare: Neoliberalism, neoconservatism, and de-democratization. Political Theory, 34(6), 690–714. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591706293016

- CBC News. (2013, October 17). ‘Angelina Jolie effect’ sparks surge in genetic testing: Test referrals up by 80 per cent in Nova Scotia. CBC News. Retrieved August, 2017, from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/angelina-jolie-effect-sparks-surge-in-genetic-testing-1.2101587

- Cheded, M., & Hopkinson, G. (2021). Heroes, villains, and victims: Tracing breast cancer activist movements. In S. Geiger (Ed.), Healthcare activism: Markets, morals, and the collective good (pp. 165–197). Oxford University Press.

- Cornelissen, J. P. (2003). Metaphor as a method in the domain of marketing. Psychology & Marketing, 20(3), 209–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10068

- Davies, B., & Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1990.tb00174.x