ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to ascertain how to advertise healthy eating to adolescents in a bid to respond to global childhood obesity. Using an interpretivist research design, a three-year, bi-national study was conducted with English and Swedish participants aged 12–14. Creative research methods explored their relationship to food advertising, consumer self-perception and their own creative recommendations. By taking the adolescents’ perspective, the paper reports on creative strategies likely to increase their receptiveness to healthy food advertising, e.g. use of visual statistics, branding and a departure from the healthy-versus-unhealthy dichotomy. The paper recommends additions to social cognitive theory, an underutilised theory within marketing, by infusing the model with a social marketing orientation intent upon increasing its utility when advertising healthy eating to adolescents.

Introduction

Global childhood obesity is reaching epidemic level and there are calls to restrict the advertising of unhealthy foods but insight into other fresh ways to respond should also be sought. Bublitz and Peracchio (Citation2015) infer that part of the answer might lie in adopting appropriate creative strategies in healthy food advertising and call for research into how marketing strategies to promote healthy products work differently for adults, adolescents and children. This paper responds by reporting an investigation into how to advertise healthy eating to adolescents. Phipps et al. (Citation2013, p. 1227) identify social cognitive theory (SCT) (Bandura, Citation2004) as an ‘underutilised theory’ within marketing. Outcomes of research described in this paper suggest extensions to SCT, specifically within the context of childhood obesity debates, infusing the original model with a social marketing orientation. This involves the adoption of marketing principles, designed to encourage behavioural change to improve the welfare of individuals and society (Andreasen, Citation1994).

This paper reports on a three-year study with English and Swedish participants aged 12–14. This age group was selected due to their increasing independence from the home environment and engagement in discretionary food purchases, i.e. low-value purchases for their own consumption (Chan et al., Citation2011; Scully et al., Citation2012). England was selected due to high childhood obesity levels, whereas Sweden has obesity levels that are less severe. A variety of research methods were adopted including discourse analysis following Spotswood and Nairn (Citation2016) proposal that more researchers adopt this approach to access young consumers’ voices.

The paper presents literature reviews on adolescents as consumers, food advertising, SCT and social marketing, followed by an account of the research methods used. The findings of the research are discussed within a framework of social marketing principles and extensions to Bandura’s (Citation2004) SCT model are proposed. Implications for food advertising policy and practice are outlined. Finally, limitations of the study are recognised and recommendations for future research are set out.

Literature review

What are the key characteristics of adolescents as food consumers?

Understanding how food marketing influences adolescents is important as they frequently have disposable income (McNeal, Citation1992) and make independent purchase decisions (Scully et al., Citation2012). Additionally, for many, physical activity declines during adolescence (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2016), compounding the risk of increasing weight. Kline (Citation2011) argues that the lifestyle risks associated with exposure to advertising are mostly related to ‘discretionary snacking choices’ (p. 85) with adolescents’ ‘discretionary power’ (p. 150) expressed in their individual purchases. This power is countered by parental restrictions, modelling and explanation to help them to make healthy choices. Kline (Citation2011) argues that, despite knowledge that a healthy diet and regular exercise represent appropriate lifestyle decisions, most adolescents are ‘discretionary risk-takers’ (p. 209) and fail to follow such practices.

Roedder John’s (Citation1999) conceptual framework of consumer socialisation progresses through three sequential stages, each displaying major cognitive shifts from pre-school to adolescence. These are: perceptual stage (3–7 years); analytical stage (7–11 years) and reflective stage (11–16 years). The reflective stage is characterised by more complex, nuanced knowledge about marketplace concepts such as pricing and branding. Adolescence brings awareness of social meanings and the underpinnings of the marketplace, accompanied by reflective thinking and reasoning. Heightened social awareness involves recognition of other people’s perspectives, with influences from group expectations. Roedder John (Citation1999) suggests that important progress takes place during adolescence involving increased understanding of advertising tactics, types of bias and social context. However, Harris et al. (Citation2014) maintain that whilst adolescents may understand marketing’s persuasive intent, they are not immune to its influence and remain vulnerable to unhealthy food marketing (also see Pechmann et al., Citation2005).

In the realm of food consumption, family and friends are the most powerful agents of socialisation, including socialisation for food preference (Ekström, Citation2010; Gunter et al., Citation2005; Young et al., Citation2003). Studies have shown parents to be the most important socialisation agents for healthy eating, with unhealthy options being consumed in peer settings away from home (Chan et al., Citation2009a, Citation2009b). In an ethnographic study with young consumers from the Nordic countries, Johansson et al. (Citation2009) found that rather than thinking in terms of healthy and unhealthy foods, they placed foods on a continuum between the two. The literature also highlights barriers to young consumers practising healthy eating, among them a perceived lack of urgency about personal health (Neumark-Sztainer et al., Citation1999).

What are the characteristics of healthy foods advertising and how might this work?

Puggelli and Bertolotti (Citation2014) describe differences between advertising for healthy and unhealthy foods, the latter associated with foods high in fat, salt and/or sugar (HFSS). HFSS food advertisements often feature school-age children, but adults appear more frequently in advertisements for healthy foods. This echoes food socialisation research, which regularly positions parents as the most important socialisation agents for healthy eating (Ekström, Citation2010). Unhealthy foods tend to be consumed in social contexts (Chan et al., Citation2009a) and peer pressure may discourage healthy eating (Hesketh et al., Citation2005). Puggelli and Bertolotti (Citation2014) claim that healthy food advertisements frequently feature cognitively complex stimuli (e.g. detailed product features), whereas HFSS food advertisements use attention-grabbing vivid imagery and sound. Additionally, Vilaro et al. (Citation2017) show that food advertisements targeting young consumers tend to use a larger number of persuasive techniques compared to adult-targeted food advertisements.

Healthy food advertising tends to use an emotional tone associated with care, control and dependence. Chan et al. (Citation2009a) found news and threat appeals are also effective in promoting healthy eating. Charry and Demoulin (Citation2012) found that this may be due to threat appeals achieving increased attention and recall. Dooley et al. (Citation2010) showed health benefits to be effective in encouraging healthy eating intention in adolescents.

These communicative formats/appeals appear consistent with dual process models of persuasion. Consequently, healthy food advertisements often employ the central route to persuasion within the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). The ELM model is designed to highlight the influence of personal relevance upon the extent of the cognitive processing of advertisements. HFSS food advertisements generally employ peripheral routes to persuasion using peripheral message cues, including visual and musical effects.

Goldberg and Gunasti (Citation2007, p. 169) argue that persistent HFSS advertising creates a perception of frequent consumption, validating and encouraging increased consumption. (Also see Dixon et al., Citation2007; Tarabashkina et al., Citation2017) When it comes to considering creative approaches for advertising healthy eating, the literature does not offer commonly agreed approaches. Bublitz and Peracchio (Citation2015, p. 2484) propose that marketers of healthy foods should learn from the marketing of ‘hedonic foods’ (i.e. HFSS options) and suggest a marketing communications framework of available strategies, including the aspects of product positioning and emotional appeals. Their framework involves a ‘dual message strategy’ (p. 2489) where a cognitive approach involving health benefit education is supplemented with a focus on taste or sensory experiences. Emphasising sensory food dimensions (emotional appeals) triggers an affective response, positively shaping attitudes towards the advertisement/brand (product positioning) and increasing consumption.

Can social cognitive theory be used to inform adolescent behavioural change?

Substantial research has been conducted to develop an understanding of attitude and behavioural change. Bandura’s (Citation1986) work on SCT is of specific relevance to this project. SCT is a well-established behavioural change theory (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014), but it has limited recognition within marketing (Phipps et al., Citation2013). SCT discusses how consumer behaviour is determined by both individual and environmental factors. Building on social learning theory, Bandura (Citation1977) posits that learning occurs via a process of reinforcement. By receiving reinforcements, or observing others doing so through modelling, or adopting behaviour through imitation, new behaviours can be encouraged.

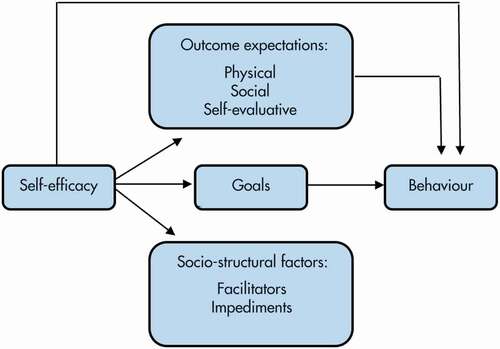

SCT specifies a core set of determinants (Bandura, Citation2004): An individual’s knowledge represents a precondition for change, yet self-efficacy, the ability to control one’s health habits, facilitates adoption and maintenance of new lifestyle habits (Bandura, Citation2009). Behavioural intention is affected by expected outcomes. Physical outcomes relate to increasing/decreasing health, while social outcomes relate to social approval/disapproval. Self-evaluative outcomes relate to an individual’s health behaviour/status, incurring self-approval or self-disapproval. Personal goals represent a source of motivation, but personal impediments interfere with healthy behaviour. Other impediments reside in the immediate environment and include the direct influence of family, friends, and the local community. The wider social context plays a role too, delivering indirect influence linked to social mores, economic conditions and cultural norms. depicts the structural paths of influence, where perceived self-efficacy affects health behaviour directly through its impact upon goals, outcome expectations and socio-structural factors (Bandura, Citation2004).

Figure 1. Bandura’s SCT model (Bandura, Citation2004, p. 146)

Advertising transfers knowledge, influences self-efficacy and establishes outcome expectations, ultimately facilitating behavioural change. Bandura (Citation2004) demonstrates how adopting SCT can strengthen public health campaigns through ‘dual paths of influence’ (p. 150). In the direct pathway, media advertising promotes changes by informing, modelling, motivating and guiding personal changes. In the socially mediated pathway, media links participants to social systems, providing collective efficacy, which provides personalised guidance, incentives and support for change (Bandura, Citation2004, Citation2009).

Several studies have reported on the use of SCT modelling in healthy eating promotion to adolescents. Ball et al. (Citation2009), Szczepanska et al. (Citation2013), and Pedersen et al. (Citation2015) confirm the impact of self-efficacy on fruit and vegetable consumption. Tarabashkina et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated the validity of the direct (e.g. advertising) and socially mediated pathways (parents, peers, social norms) in explaining consumption of HFSS foods. The research reported by the current authors is the first to recommend additions to SCT by infusing it with a social marketing orientation to increase its utility when advertising healthy eating to adolescents.

Could social marketing thinking enhance SCT?

Andreasen (Citation1994, p. 110) defines social marketing as providing ‘adaptation of commercial marketing technologies to programs designed to influence the voluntary behaviour of target audiences to improve their personal welfare and that of the society of which they are part’. To deliver effective social impact through the application of marketing concepts (Lefebvre, Citation2013), the social context around issues demands a collective orientation (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014). This thinking concurs with Bandura’s (Citation2004) ideas around collective efficacy supported by the immediate and wider social context. This cohesion, and the fundamental aim of social marketing to improve personal and societal welfare through behavioural change, highlights that social marketing principles can enhance SCT.

Social marketing is informed by several fundamental elements including consumer orientation and exchange theory. Consumer orientation involves a consumer perspective, seeking to understand those whose behaviour needs to change (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014). Exchange theory proposes that people ascribe value to behavioural options and select the one offering the greatest benefit (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014). To achieve a mutually beneficial exchange, Hastings and Domegan (Citation2014) prescribe a flexible offering, as compromise increases openness to change. Accordingly, rather than condemning a snack unequivocally, the social marketer assists the selection of a healthier snack (Cronin et al., Citation2014). Long-term effort is required to change behaviour; adopting a healthy diet involves lifestyle changes, not an isolated behaviour (Hastings & Saren, Citation2003). Emphasis is placed upon the maintenance of change (Donovan & Henley, Citation2010), lending importance to relationship marketing thinking (Hastings & Saren, Citation2003). Consequently, social marketing campaigns aim to achieve their objectives over time, since behaviour change may not take place simultaneously with the communication (Antonetti et al., Citation2015). Finally, behavioural change faces competition, indirect/passive competition from current behaviours (beliefs, attitudes, intentions) and social systems (family, friends, the immediate environment). HFSS advertising provides direct/active competition. Finally, a creative orientation adds essential, motivating elements of imagination and innovation.

Advertising on its own cannot resolve the obesity epidemic. However, taking a systemic approach (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014) where advertising is one of several tools used to address this issue, and given the uncertainty within the literature regarding effective advertising appeals, this study has explored new approaches to healthy food advertising in the context of adolescents. This literature review has also highlighted social marketing with its behavioural change agenda as a possible extension to SCT. The research reported below explores potential creative orientations for advertising healthy eating, considering two objectives: (1) how to advertise healthy eating in ways that will resonate with adolescents and (2) how the findings relating to a suitable creative orientation inform SCT theory. To address these objectives, fieldwork set out to answer three questions:

From their perspective, how do English and Swedish adolescents perceive themselves as consumers?

What are their dominant discourses relating to food advertising/healthy eating?

What message formats and advertising appeals do they propose for promoting healthy eating/foods to adolescents?

Methods

Recognising young people as primary stakeholders in the childhood obesity challenge (Mehta et al., Citation2010), the research design aimed to give them a voice (Bucknall, Citation2014), acknowledging ‘voice’ not only as verbal (Spotswood & Nairn, Citation2016) but also shared through visual and audio forms. Adopting an interpretive perspective, the research identified young people as social actors creating meaning through interacting with their peers (James et al., Citation1998) awarding them research status as ‘co-creators of knowledge’ (Kellett, Citation2010, p. 24). Chan et al. (Citation2009b) maintain that perceptions of healthy eating are context and age group specific, making an interpretive approach with a focus on understanding and interpretation important. Common to all three stages was the group context and the opportunity for participants to express themselves by creative and vocal means (Banister & Booth, Citation2005). This approach was supported by adopting social marketing principles calling for a shift away from individually focused interventions to thinking in terms of group/systems effects (Donovan & Henley, Citation2010).

Sample

Within the food advertising literature, many studies are cross-sectional (Bridges & Briesch, Citation2006) providing a ‘snapshot’ at a point in time (Saunders et al., Citation2016, p. 201). The research design underpinning this study sought detailed and nuanced insight into issues associated with food advertising. It followed English and Swedish participants aged 12–14 in three stages over a three-year period. Investigating social norms in adolescent healthy eating, Pedersen et al. (Citation2015) recognised that the cultural context and changes over time are important aspects of socialisation processes, favouring cross-cultural and longitudinal studies. The rationale for the sample’s age group was based on their increasing independence from the home environment and their ability to make low-cost food purchases (Chan et al., Citation2011). England was selected due to high levels of childhood obesity (35% of 11–15-year-olds are overweight [NHS Digital, Citation2015]). Sweden was included as a comparator, where obesity levels are less severe (20% of boys and 11% of girls aged 13 are overweight [WHO, Citation2013]).

Secondary-schools, in similarly sized towns with equivalent cultural environments, in southwest Sweden and northwest England were recruited to participate. summarises key sample characteristics associated with each of the three stages. There were about 12 months between each fieldwork stage. Guided by the need to select methods suited to young consumers’ diverse and age-related competencies (Greene & Hill, Citation2005), gradually more challenging research techniques were adopted, allowing insight into consumer development of participants over the span of the research stages. Interpretive research tends to use multiple methods to understand how young consumers experience consumption (Davis, Citation2010). Differing research objectives guiding each stage also required varied methods. A small number of participants chose not to participate in all stages, but replacements were recruited from the same school year group. Each stage of the research was granted ethical approval. Information leaflets explaining the research and the participants’ rights underpinned the process of gaining informed consent from participants and their parents (Heath et al., Citation2009). Recognising the importance of ‘ongoing consent’, consent was re-sought for each stage (Kellett, Citation2010, p. 25).

Table 1. Sample characteristics (primary data)

Research design

Stage 1: focus group-led

Stage 1 was focus group-led and formative for the subsequent stages, aiming to explore participants’ understanding and perceived importance of healthy eating. Hackley (Citation1998) maintains that meaning is a social construction, rather than constructed on a private, cognitive level and that the sense of meaning/reality is discursively constructed through language. Moisander and Valtonen (Citation2006) similarly maintain that meaning is constructed discursively in social interaction using text, talk, sounds, images and signifying practices, making focus groups appropriate for this stage. The focus groups took place in Sweden and England with participants aged 12. They were administered in classrooms and audio recorded. Data quality was optimised as both English and Swedish participant cohorts used their first language (Irvine et al., Citation2008). (For reference, one of the authors is a bilingual speaker of Swedish and English.) A semi-structured interview guide directed activities including: the meaning of healthy and unhealthy foods, the influence of socialisation agents and participants’ use of YouTube. This video-sharing site was relevant due to expected frequent usage and high exposure to advertisements.

Stage 2: workshops

Stage 2 workshops took place in Sweden and England, a year later, with participants now aged 13, aiming to allow participants to profile their age group in terms of their characteristics as young consumers. The design and analysis of this stage was influenced by Wetherell and Maybin (Citation1996) argument that the self is socially constructed. Language and discourse provide important raw materials for the construction of the self, with our identities, in part, discursive products. Collages, or ‘visual artwork’ (Saunders, Citation2009, p. 23), were constructed jointly by groups using magazine images. Moisander and Valtonen (Citation2006, p. 96) maintain that ‘collaborative and reflexive use of visuals’ gives participants increased voice and collages are acknowledged as producing rich research data (Colakoglu & Littlefield, Citation2011) and enhanced engagement (Havlena & Holak, Citation1996). Magazines were selected to ensure availability of a wide variety of images. Participants were tasked with constructing collages using images and words to describe ‘a typical 13-year-old consumer’ (boy and girl). Prompts sought to establish their interests, aspirations, attitudes, opinions and relationships with food brands.

Stage 3: multi-methods

Stage 3 took place in both Sweden and England, a year after stage 2. It involved analysis of selected television advertisements, a medium which provides opportunities to comment upon both visual narrative and audio. Insight was collected from the 14-year-old participants using focus group discussions captured via Padlet (www.padlet.com), a research tool which allows contributors to share their thoughts via an online wall. Questions explored participant reactions to advertisements and the messages they saw within them. Workshops followed where participants designed advertisements promoting healthy eating to their own age group. This stage had two aims: (1) to gain insight into 14-year-olds’ reactions to advertisements promoting healthy eating/a healthy lifestyle, and (2) to allow participants to devise communication strategies appropriate for advertising healthy eating/foods to their own age group by designing their own advertisements. This approach recognised the value of having consumer insights frame and direct creative work (Hackley, Citation2003) and was consistent with the work of Nelson (Citation2016), whose research on developing children’s media literacy featured their interpretation and creation of advertising messages.

Data analysis

All data were transcribed verbatim. Data analysis focused upon verbal and visual language. In stage 1, the central unit of analysis (Eyal & Te’eni-Harari, Citation2016) was focus group discussion, with analysis informed by Brown and Yule (Citation1983) discussion of ‘topic and the representation of discourse content’ (p. 68), with ‘topic’ understood as ‘what is being talked about’ (p. 71). The analysis sought to identify topics in recognition of Brown and Yule’s claim of a connection between ‘discourse topic’ and ‘discourse content’. The analysis employed the terms ‘theme’ (equivalent to discourse topic) and ‘discourse’ (equivalent to discourse content). Accordingly, the transcribed text was used to identify dominant themes, which in turn were analysed to establish discourses of healthy eating and food advertising. The analytical process considered the social and cultural contexts relevant to the participants and their discussion (Paltridge, Citation2012). Appendix provides an illustration of the coding process on a fragment of focus group transcript.

In stage 2, the central unit of analysis (Eyal & Te’eni-Harari, Citation2016) was consumer collages. Their analysis followed the concept of the hermeneutic circle, exploring images and words in relation to each other and the overall context. Accordingly, ‘parts’ referred to single collage elements (images and words), whereas the ‘whole’ referred to the collages in their entirety and the context in which they were constructed (Pachler, Citation2014). The first analysis stage used categorisation to map the ‘parts’. Units of data, images and words, were classified as representing a more general category (Spiggle, Citation1994), each of which received a label. The visual images were not analysed in their own right, but allowed a means for the participants to communicate aspects of their lives, experiences and identities (Emmison et al., Citation2012). As such, the collages were seen to represent visual language to be read as a visual cultural story (Moisander & Valtonen, Citation2006). The emerging themes, verbal and visual, were analysed using the principles of discourse analysis as described for stage 1 (Brown & Yule, Citation1983).

In stage 3, the central units of analysis (Eyal & Te’eni-Harari, Citation2016) were the Padlets and the participant-designed advertisements. The analysis of the Padlets sought ‘discourse content’ (Brown & Yule, Citation1983, p. 71), or discourses, following a format similar to that described by Simunaniemi et al. (Citation2012) in their analysis of fruit and vegetable-related weblog texts. Accordingly, the analysis began by reading the postings on the discussion wall with an open mind to identify recurring patterns in the data. Preliminary themes were identified and coded into thematic categories. In the second reading phase, the preliminary themes were crystallised into themes. In the third stage, the themes were categorised into main discourses.

The advertisements designed by the participants varied in their presentation from posters to simple films. Consequently, for the verbal elements, the same approach to discourse analysis was employed as for stage 1 (Brown & Yule, Citation1983; Paltridge, Citation2012). The images were thought of as ‘like language’ and were ‘read’ in order to interpret their meaning in a similar way to the advertising copy (Hall, Citation1997, p. 5). In common with Emmison et al.’s (Citation2012, p. 113) principles, ‘manifest themes’ were sought across images, whilst also exploring the social aspects displayed. The analysis then used Emmison et al.’s (Citation2012) approach to visual social science inquiry. The visual data were approached ‘sociologically’ with the aim of investigating how it served as ‘sources of concrete visual information about the abstract concepts and processes which are central to organising everyday social life’ (p. 63). The analysis was also informed by Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation2006) grammar of visual design, concentrating on how visual elements combine in visual statements into meaningful wholes, with attention paid to representational, interactive and compositional patterns. The resulting visual structures refer to interpretations of experience and forms of social interaction.

Findings and discussion

This section presents findings from the three stages of the fieldwork. It specifically addresses the first study objective of establishing how to advertise healthy eating in ways that will resonate with adolescents. To remind the reader, the fieldwork aimed to find out how the participants’ discourses are relating to food advertising/healthy eating (stage 1), how they perceive themselves as consumers (stage 2) and what message formats/advertising appeals they propose for promoting healthy eating/foods to adolescents (stage 3).

Stage 1: focus group-led

Stage 1 was concerned with participants’ understanding and perceived importance of healthy eating/food advertising and addressed the second research question posed following the literature review:

Research question two: What are adolescents’ dominant discourses relating to food advertising/healthy eating?

The discourse analysis identified eight discourses present to varying degrees in the focus groups, these being: consumer socialisation; advertising literacy; scepticism towards food advertising; discourse associated with food/food advertising; discourse concerning fast food/soft drinks; health literacy; food/drinks brands and retail brands; and social consumption of advertising. These will be reported using Hastings and Domegan (Citation2014) social marketing dimensions, i.e. consumer, competitive, collective and creative.

Regarding the consumer orientation, the focus groups of both nationalities demonstrated a discourse of reasonable health literacy in terms of knowledge about the importance of a healthy diet (physical outcome expectations [Bandura, Citation2004]), for instance: ‘What is in the food circle is healthy’ (male Swedish participant); ‘eating your five-a-day’ (female English participant). Asked whether food advertising guides healthy choices, a discourse of scepticism towards food advertising emerged, as illustrated by this statement by a Swedish male participant: ‘Almost all advertising is unhealthy, [for] junk [food]’. An English female participant stated: ‘There’s not really a lot of, er, fruit and veg adverts. It’s more like biscuits and all that when the adverts are on.’ This finding chimes with Te’eni-Harari and Eyal’s (Citation2020) research with similarly aged adolescents who expressed comparable scepticism. The Swedish discourse contained references to organic produce (e.g. the Swedish KRAV organic certification), locally sourced produce and physical exercise. These aspects were absent from the English discourse, apart from a reference to free-range eggs attracting a price premium. Overall, the participants appeared to possess the skills-set of reflective consumers as outlined by Roedder John (Citation1999). Accordingly, a discourse associated with advertising literacy emerged. Both nationalities demonstrated scepticism towards food advertising, claiming perfect-looking advertising imagery does not truthfully represent the actual product: ‘ … in the advertising it looks like this … layers, really nice, like this … And then when you get it, it’s like squashed together … ’ (Swedish female participant on the mismatch between the portrayal of McDonald’s burgers in advertisements and their actual presentation upon purchase). However, a discourse of still developing advertising literacy was discernible. Accordingly, statements about advertising tended to be one-dimensional recognising only the selling intent (Carter et al., Citation2011), when a more advanced understanding would recognise its multi-faceted role. For instance, the statement by a Swedish male participant ‘I don’t think that they should advertise. Everyone already knows what Marabou [a Swedish chocolate brand] is’, does not recognise such advertising functions as brand image building, reminder advertising and new consumer recruitment.

Relating to the competitive orientation (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014), the analysis discerned a discourse of advertising for core foods (those recommended for a healthy, balanced diet) that was characterised by a lack of enthusiasm for both nationalities, as demonstrated by this statement by a female Swedish participant: ‘You don’t tend to, like, think about food advertising. It has to, like, look fun’. Health literacy notwithstanding, their discretionary food purchases were exempt from health concerns. Both nationalities appeared to fit Kline’s (Citation2011, p. 209) description of ‘discretionary risk-takers’; adolescents whose risky lifestyle choices neglect their ‘five-a-day’ and exercise. Te’eni-Harari and Eyal’s (Citation2020) research with adolescents highlighted a ‘paradox’ in relation to food and peers. Although diets were a central conversation topic with friends, social outings would often involve consuming ‘junk food, pizza and ice-cream’ (Te’eni-Harari & Eyal, Citation2020, p. 887). Social pressure to consume unhealthy food reflecting Bandura’s (Citation2004) social outcome expectations was evident. For instance, an English female participant stated: ‘You know, when you go out with your mates, you can’t buy an apple. That’s why you buy crisps and sweets.’ This statement suggests that a peer-initiated socialisation process (Williams & Littlefield, Citation2018) guides the participant’s purchase behaviour, as non-conformance may lead to social exclusion. Furthermore, such purchases appeared to be a manifestation of consumer independence, often constituting a treat. For some English participants, visiting a fast food outlet with friends delivers the value proposition of a social experience (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014). For example, an English female participant explained: ‘It’s the taste to McDonald’s and it’s nice, everybody eats it.’ ‘On the adverts, they appeal to us more than they would an adult because, you know, children have got to go out with their friends and then go “oh, let’s go to McDonald’s”.’ This statement also suggests the importance of taste, peer influence and advertising in encouraging discretionary spending.

In this context social norms make HFSS foods acceptable, which is also noted by Tarabashkina et al. (Citation2017). This fits with research by Williams and Littlefield (Citation2018), who found that a process of peer socialisation is used to both encourage the use of correct (i.e. popular) fashion brands and discourage the use of incorrect ones. There is evidence of a similar process in this study in relation to the recreational consumption of food away from home, with unhealthy options the correct/popular choice. The researchers identified a positive discourse associated with fast food/soft drinks among both nationalities with references to several brands (e.g. McDonald’s, Burger King and Coca-Cola).

It seemed the English adolescents felt pressurised to be healthy, as conveyed by this English female participant: ‘They’ve put a big push on us of this day and age to eat healthy food.’ Here, they may learn from the Scandinavian ‘just-enough ideal’: Johansson et al.’s (Citation2009, p. 47) ethnography found Scandinavian children perceive food along a continuum, rather than as either healthy or unhealthy. The Swedes in this study used similar discourse as shown by this statement by a Swedish female participant: ‘Healthy food, I think, is when you eat like this … a sensible amount [use of Swedish word “lagom”, meaning “not too much, not too little, just right”] and you have lots of vegetables’. Interestingly, the Swedes reported feeling no peer pressure to consume healthy/unhealthy foods and demonstrated robust self-efficacy in healthy meal choices (Bandura, Citation2004).

Concerning the collective orientation (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014) a discourse of consumer socialisation emerged, wherein family especially, but also friends (as reported above), represented influential socialisation agents for both nationalities. Extending the findings of Te’eni-Harari and Eyal (Citation2020), this study identified the social function of food, but noted additionally that friends tend to be less healthy influencers than family. Using a card sorting activity, all focus groups of both nationalities identified family as the most important socialisation agent, supported by statements such as: ‘They [parents] buy the food. And then they want it to be good food’ (Swedish female participant). Brennan et al. (Citation2010) found adolescents in their survey perceived family and friends to be an important, highly trustworthy source of health and nutrition information. Te’eni-Harari and Eyal’s (Citation2020) study identified family as providing robust, positive nutritional health socialisation (also see Chan et al., Citation2011). Additional socialisation agents featured in the Swedish discourse, namely, school, sports clubs and the dental health service. Widespread involvement with a long-running advertising campaign of Swedish food retailer ICA indicated retailers’ potential as socialisation agents. The Swedes were highly involved with the storytelling of ICA’s advertising: ‘But, I mean, ICA’s, it’s so … They haven’t just made it into an advert. They have made it into like a story’ (female participant). The participants were familiar with the storyline and knew the names of the characters. A discourse of social consumption of advertising emerged, whereby the adolescents consumed the ICA advertisements as a form of cultural product independent of the products advertised (Ritson & Elliott, Citation1995, Citation1999). The English participants lacked the same fascination with food retailers, although names of these featured widely in their discourse.

Regarding the creative orientation (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014), food advertising in general was perceived as uninteresting, with messages that resonate with adolescents required, as demonstrated by an English female participant: ‘If I saw an advert about Tesco and their fruit and veg, then I might leave the room or something, because it’s not good enough.’ A strong discourse of food and drinks brands emerged among both nationalities with emphasis on brands belonging to the ‘Big Five’ (Office of Communications[Ofcom], Citation2004), breakfast cereal, soft drinks, confectionery, savoury snacks and fast food outlets, that tend to be energy-dense with powerful branding. Consequently, despite Sweden’s ban on television advertising targeting the under-12’s (Swedish Radio and Television Act, Citation2010) and the UK’s ban on HFSS advertising targeting the under-16’s (Ofcom, Citation2007), the adolescents’ discourse mirrored the type of (unhealthy) products generally advertised on television. Unsurprisingly, this suggests that adolescents are exposed to such advertisements (also see Fleming-Milici & Harris, Citation2018) and demonstrates the effectiveness of such advertising. Such brands enthused participants and the Swedes especially, who demonstrated familiarity with advertising campaigns by spontaneously introducing slogans such as ‘The taste you never forget’, ‘Mmm … Marabou (long-standing slogans of Swedish chocolate brand Marabou) and ‘I’m loving it’ (McDonald’s). These slogans and longer sections of familiar advertisements were acted out by the Swedes, using advertising discourse, theatrical voices and song. The multitude of brands in the adolescents’ discourse highlighted an opportunity to use branding to develop an identity for healthy foods. Over time, such brands could establish themselves as substitutes for heavily branded, unhealthy foods. In the context of an obesity prevention intervention, Venturini (Citation2016) shows how a brand can establish itself as a respected and trusted voice in a market characterised by competing messages and efforts. Elliott (Citation2014) similarly recognises the potential of personality attributes of unprocessed foods to encourage healthy eating among adolescents, since foods are rarely selected simply on nutritional quality. The role of healthy food branding and its potential to influence adolescents’ food choice in steering away from HFSS foods deserves future research attention.

Stage 2: collage workshops

Stage 2 addressed the first research question framed following the literature review:

Research question one: From their perspective, how do English and Swedish adolescents perceive themselves as consumers?

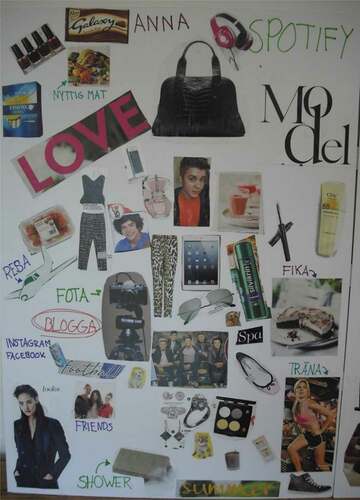

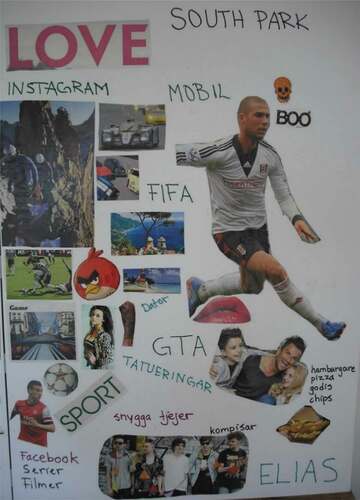

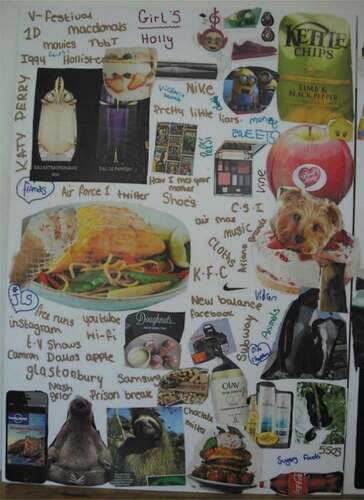

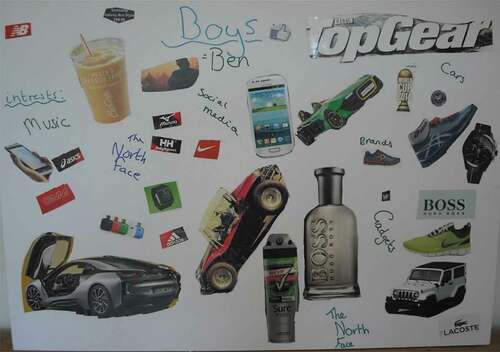

In order to do this, participants profiled ‘a typical 13-year-old consumer’ using collage construction, exploring the consumer dimension of Hastings and Domegan’s (Citation2014) social marketing framework. Categorisation of the visual and verbal language in the collages resulted in lists of themes for each collage. Guided by these themes and close analysis of the participants’ discussions, the researchers wrote consumer stories. The collages and stories introduced 12 consumers, among them AnnaFootnote1 (see ), and Elias (see ), both Swedish, and Holly (see ) and Ben (see ), both English. The analysis identified discourses associated with food, socialisation agents, brands, sports/personal fitness/well-being, and experiences. Discourses associated with food, socialisation agents and brands will be reported on here. Due to word limit constraints, this section addresses the collages, not the stories.

The discourse emerging around food demonstrated limited emphasis upon core foods, which echoes the findings in stage 1. Other studies (e.g. Power et al., Citation2010; Brennan et al., Citation2010) also identified that young consumers’ lack of urgency about personal health presents an impediment (Bandura, Citation2004) to healthy eating. Gender differences were evident. The boys were portrayed as enjoying convenience foods and snacks for the taste, but also for how such foods fit their lifestyles. Heat-up pizzas mean they can share responsibility for mealtimes with their parents and, importantly for young adolescents, emerging independence. Self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation2004, Citation2009), required for healthy eating, was of little relevance to the boys as the concept of healthy eating lacked saliency. Instead, their efficacious behaviour was expressed in sports activities.

The collages portraying girls, feature both core foods and treats. For instance, Anna’s collage contains an image of fresh fruit and vegetables with the hand-written caption ‘nyttig mat’ (English: healthy food). Holly’s collage features nutritious breakfast habits and snacks, as well as a healthy evening meal. This, along with verbal/visual references to family on other collages (e.g. see for Elias’ collage) feed into a discourse of parents’ positive role as food socialisation agents (in common with stage 1), with the home environment providing key socio-structural facilitators (Bandura, Citation2004) for healthy eating, such as family meals and access to core foods. This supports Kline’s (Citation2011) contention of young adolescents’ dependency on their parents for positive food socialisation. However, compared to stage 1, family received fewer mentions and friends featured more prominently (e.g. see for Anna’s collage), indicating further consumer socialisation and developing independence in common with findings of Chan et al. (Citation2011).

A shared feature of the collages is that when spending their own money, these consumers treat themselves to more indulgent options illustrated by the emphasis on such choices. This behaviour may be encouraged by advertising. Holly watches plenty of television. All collages feature social media, meaning these consumers are likely to be exposed to a significant volume of food advertising. Fast food restaurants are important to Holly and Ben and meeting friends for ‘fika’ (Swedish term for a social break with a drink and cake) features on Anna’s collage. These findings illustrate a complex set of socio-structural factors (Bandura, Citation2004) at play, including influence from food advertising, emerging independence and peer influences, that may inhibit healthy eating. As in stage 1, the social function of food and a discourse of how friends tend to be less healthy influencers than family is evident. Further, sharing images of visually appealing indulgent foods on social media is a strategy for accumulating social currency, which in Anna’s case is directly supported by her hobbies of home-baking and photography.

The food discourse demonstrated several functions of food in addition to providing nutrition. Accordingly, fast food restaurant visits offer important social experiences. Especially for the English, there was a lack of concern that fast food is generally unhealthy, with no hesitation in making such foods part of their identity. Their collages suggest that such restaurant visits offer independence, forming part of consumer socialisation. Food enjoyment matters with the promise of a taste experience. For two of the female collage consumers, baking offers creative expression. As found in stage 1, despite evidence of health literacy, the collages portray ‘discretionary risk-takers’ (Kline, Citation2011, p. 209). Tarabashkina et al.’s (Citation2016) research also found older children’s (aged 11–13) consumption of unhealthy foods to be guided by social acceptability and taste evaluations, despite inappropriate nutritional characteristics.

The collages illustrate a fixation with brands in contexts from footwear to fast food. Roedder John (Citation1999) recognises that in the reflective stage (ages 11–16), children develop increased social awareness. This may involve increased reliance on brands for self-expression, as suggested in the collages, but also to safeguard social inclusion within the peer group (Williams & Littlefield, Citation2018). Involvement with brands, also seen in stage 1, signals that there is an opportunity for brand building around healthy foods to challenge the well-entrenched position of HFSS foods. English collage consumers demonstrated a more extensive preoccupation with brands, which together with their appetite for fast food restaurants represented the only real differences to the Swedish collage consumers.

In summary, the collages showed that where food experiences offer immediate benefits (i.e. taste, social, independence, creativity) this poses strong competition to any concern held for long-term health consequences (Pechmann et al., Citation2003). Commensurate with the work of Phipps et al. (Citation2013), which also addressed an area of complex behaviour, i.e. sustainable consumption, stages 1 and 2 demonstrated the suitability within a marketing context of the general framework of SCT. Hence, the behaviour of the individual, and whether to opt for a healthy option, is intricately tied up with both personal factors (e.g. level of self-efficacy) and environmental factors (e.g. family/peer influence).

Stage 3: multi-methods

Stage 3 addressed two of the research questions formulated following the literature review:

Research question two, to identify and characterise discourses surrounding healthy eating/living advertisements, through evaluation of television advertisements by the 14-year-olds. (‘Coca-Cola Grandpa – Living a Healthy Lifestyle’ and ‘Be Food Smart’ from the UK government-led Change4Life campaign encouraging healthy eating/exercise).

Research question three, to explore what message formats/advertising appeals are appropriate for promoting healthy eating/foods to adolescents, by asking the participants to design their own advertisements.

Careful analysis of the postings on Padlet in response to the two advertisements resulted in lists of preliminary themes, which were distilled into over-arching themes. Repeated re-reading of the postings and reference to the themes, identified emerging discourses for both advertisements. There was overlap between the discourses of the two nationalities, but also some differences. Both nationalities clearly demonstrated characteristics commensurate with the reflective stage of Roedder John’s (Citation1999) consumer socialisation stages. In recognition of the mediated messages of the advertisement, the discussions of both nationalities were characterised by a discourse of healthy living. However, implementing their reasoning skills, both nationalities perceived Coca-Cola’s advertisement as biased, even deceptive, with a discourse of scepticism questioning Coca-Cola’s credibility as a source of health messages, for instance: ‘Think it is bad that Coca-Cola try to sound that healthy with all their various colas. Like, Coca-Cola stop, you are not healthy. Stop trying to trick people about it’ (Swedish participant); ‘Be healthy, drink Coke, those two don’t match’ (English participant). Commensurate with their enhanced processing capacity, motivation and knowledge (Moore & Lutz, Citation2000), the participants were able to integrate their product experiences and their general knowledge of Coca-Cola with the advertisement in providing evaluations. In a discourse of moderation, with a tacit reference to the ‘lagom’ concept, the Swedes recognised occasional soft drink consumption as permissible within an overall healthy lifestyle, as expressed by one participant: ‘You can live healthily and also drink Cola, because remember what we learned in food technology: “Nothing is that healthy that it is the only thing that you can eat and nothing is that unhealthy that you never should [eat it]”’. In a discourse of defiance and a discourse of consumer choice, the Swedish participants declared their entitlement to prioritise health or a taste experience. Equipped with reasonable advertising literacy and health knowledge (Bandura, Citation2004), these ‘discretionary risk-takers’ (Kline, Citation2011, p. 209) rated immediate psychological benefits of taste over elusive, distant benefits of a healthier choice (Hastings & Saren, Citation2003). A parallel can be drawn to Pechmann et al.’s research with adolescents which demonstrated that anti-smoking advertisements emphasising long-term negative health consequences led to greater intentions to smoke. Furthermore, their emotional connection to powerful brands may push scepticism and persuasion knowledge to a lower priority (Kline, Citation2010). Two further discourses emerged among the English, a discourse of time and a discourse of personal relationships: ‘I liked the way it showed family coming together and that even though times have changed some things stay the same like family’ (English participant).

For the Change4Life advertisement, the analysis identified a discourse of well-being, related to a discourse of change for both nationalities, for instance: ‘It makes me realise how much sugar that we consume and how large the quantities are. It makes me want to be healthier. To look after my body’ (Swedish participant): ‘I like the way it shows you real statistics of the amount of sugar and fat in our foods’ (English participant). The English participants recognised that the advertisement offered strategies for behavioural change (a discourse of methods of change), with health knowledge/skills instilling self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation2009), for instance: ‘Eat healthy to stay healthy. It notified the younger audience that to stay alive longer, then you need to eat healthy. It also gives healthy alternatives to eating junk food’ (English participant).

However, both groups resisted attempts at efficacious modelling (Bandura, Citation2009), with peripheral cues (primary colours/animated clay characters within an imaginary world) partly resulting in message rejection, for instance: ‘I hate that it is like clay figures’ (Swedish participant). Despite the animated clay characters being presented as a family unit, neither nationality perceived them as such. Rather, the characters were perhaps perceived as too dissimilar to humans to be perceived as a metaphor for a human family, resulting in a failed attempt at efficacious modelling (Bandura, Citation2009). For the Swedes, the discourse of defiance and the discourse of consumer choice re-emerged: ‘I will still be drinking pop’. Photographic images of sugar cubes and fat (referred to as ‘real statistics’), on the other hand, visualised their danger akin to threat appeals. This easy-to-grasp, visual message expression received approval, for instance: ‘I like the way it shows you real statistics of the amount of sugar and fat in our foods’ (English participant). This confirms the effectiveness of fear-inducing appeals for promoting healthy eating as found by Charry and Demoulin (Citation2012) (also see Chan et al., Citation2009a). The discourse analysis suggests that this target audience is more likely to pay attention to health messages and so persuasion would depend on the quality of the arguments presented. This confirms Livingstone and Helsper’s (Citation2004) hypothesis that within food advertising, adolescents are more likely to be persuaded by the central route of the ELM (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). More specifically, the discourse analysis indicated that both nationalities pay attention to informative advertisements that communicate product values. This concurs with Dooley et al. (Citation2010) who found that current statistics that communicate immediate (rather than distant future) health benefits are effective in creating both interest and involvement with adolescents. McAlister and Bargh’s (Citation2016) study into the utility of the ELM with children also found weak arguments and peripheral cues to dissuade children from thinking positively about a breakfast cereal in a high-involvement condition.

The participants created film and poster advertisements. The advertising appeals used fitted into three categories based on informational and emotional alignments. These were:

health, benefits and achievement,

music, humour, animation and story,

threat appeals.

(1) Health, benefits and achievement: This first category of appeals was used in varying strengths by all advertisements. Most were factual appeals and delivered health-relevant, central arguments to encourage elaboration and persuasion. This confirms Puggelli and Bertolotti’s (Citation2014) evaluation that healthy food advertisements tend to use health appeals. Additionally, the advertisements used benefit appeals by communicating positive outcomes from a healthy lifestyle, as well as achievement appeals by alluding to what a healthy diet can achieve. The achievement and benefit appeals both modelled positive outcome expectations (Bandura, Citation2004), mostly of the social and self-evaluative kind, and may be categorised as incentive appeals (Donovan & Henley, Citation2010). Achievement appeals have previsouly been rated positively by adolescents for use in advertising discouraging soft drink consumption (Chan et al., Citation2009a) and in advertisements for healthy eating (Chan & Tsang, Citation2011).

To exemplify the application of this first category of appeals, what follows is a description of a poster-style advertisement created by a Swedish group of participants: The advertisement presents the target audience with two separate lifestyles, modelled vicariously (Bandura, Citation2009) and delivered as a binary opposition (Emmison et al., Citation2012). The ‘approved’ lifestyle (indicated with a green tick) features healthy food choices (health appeal) fuelling an athletic-looking woman aiming for the top of a hill, the ultimate peak of fitness (benefit appeal). The message is predominently visual. The images combine with the slogan ‘Go for green, because it is a hit to be fit’ into an overall message of health encouragement (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2006). A cloudless sky functions as an index (Emmison et al., Citation2012) that the sky is the limit for a person adopting this lifestyle, with the aim of building the audience’s self-efficacy (Maibach & Cotton, Citation1995). There is an unequivocal message that a diet of low-nutrient foods (the ‘disapproved’ lifestyle marked with a red cross) is likely to result in weightgain and a lack of energy, as modelled by an overweight man asleep in front of the television. A strong nudge (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008) is delivered for the audience to opt for the lifestyle that has received the green tick.

Eyal and Te’eni-Harari (Citation2016) recognise that from a social cognitive perspective, character portrayal in advertisements serves as learning models, especially for young consumers. Consequently, this clear juxtaposition of lifestyles avoids the ‘nutrition confusion’ found by Eyal and Te’eni-Harari (Citation2016) in HFSS advertisements repeatedly featuring thin characters enjoying such foods. The overall creative concept delivers an incentive appeal, where, in addition to cultivating new competencies, the modelling has motivational effects (Bandura, Citation2009). These findings chime with those of Dooley et al. (Citation2010), whose study found public service announcements delivering a health benefit claim accompanied by a strong, simple visual to be effective at encouraging healthy eating plans among adolescents.

The prominence of the informational appeals reported in this paper appear to be at odds with Bublitz and Peracchio’s (Citation2015) proposition that healthy foods would find more success by adopting and giving prominence to affective appeals in preference to more customary cognitive appeals. However, the advertisements designed by the participants in this research deal with healthy living/eating, rather than specific food brands (the targets for Bublitz and Peracchio’s advice). Also, the research reported here is specific to adolescents and employs their perspective, rather than the generalised perspective employed by Bublitz and Peracchio.

(2) Music, humour, animation and story, used in the film advertisements, introduced emotional appeals with a positive note, supporting the substantive health messages. (3) Threat appeals were used in all films and one poster advertisement and introduced stronger, purpose-oriented emotion to create and hold attention, and subsequently encourage behavioural change. The aforementioned appeals are all used within a film advertisement designed by an English group, which can be viewed by scanning the QR code below or by using this link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1nb1aKhV1LqEk4_HZr3sbW4mLDjw8yGO_/view?usp=sharing.

Using the genre of animation (Emmison et al., Citation2012), the advertisement is predominantly light-hearted, but as one character declares their intention to visit McDonald’s, the other gasps and announces the calorie count and negative health effects of a burger. Dramatic-sounding music rhetorically supports the claim that fast food poses a health threat (Scott, Citation1990), delivering a mild threat appeal. The story has a happy ending when the characters mount their horses and, accompanied by saloon music, ride off to the juice bar. The delivery through a humour appeal gives a light-hearted tone to the advertisement and represents a peripheral cue (rather than a substantive health-centred argument). This humorous context increases the liking of the message source and instigates a positive mood, increasing the persuasive effect of the advertisement (Sternthal & Craig, Citation1973; Weinberger & Gulas, Citation1992). The advertisement introduces a mild threat, but demonstrates the possibility of overcoming this with an alternative behaviour in the form of the juice bar visit (a weak health appeal). Manyiwa and Brennan (Citation2012) show how individuals who perceive higher self-efficacy are more likely to change their behaviour in response to fear appeal advertisements. Although their study relates to anti-smoking advertisements, they claim the findings to be relevant for campaigns that seek to reduce consumption of unhealthy foods. Antonetti et al. (Citation2015) claim that physical threats on their own may not be persuasive with young consumers and that the addition of a social threat aids effectiveness. Hence, in this advertisement opting for the healthier option may follow from a desire to fit in with the peer group (Williams & Littlefield, Citation2018).

On the whole, the advertisements tended to deliver a substantive message along the central route to persuasion, a path believed to deliver longer-lasting persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). This message strategy appears appropriate for communications promoting a healthier lifestyle, dependent upon relational thinking to achieve and maintain long-term social change (Hastings & Saren, Citation2003). It is noteworthy that the poster-style advertisement described earlier features chocolate and so invites treats within a balanced diet. The chocolate represents visual vocabulary (Moisander & Valtonen, Citation2006) that allows for a mutually beneficial exchange by introducing compromise (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014) and ties in with the Swedish concept of ‘lagom’.

How do the findings relating to a suitable creative orientation inform SCT theory?

This section addresses the findings in relation to the second study objective of establishing how the findings inform SCT theory. First, four key findings required for the successful promotion of healthy eating to adolescents and with direct relevance to a social marketing orientation will be discussed. Then, extensions to the SCT framework will be proposed to include social marketing principles, adjusting the theory to the context of advertising healthy eating to adolescents. The discussion then turns to identifying implications for policy and practice resulting from the study.

Harnessing socialisation agents for positive influence

Commensurate with the literature (e.g. Ball et al., Citation2009; Pedersen et al., Citation2015; Szczepanska et al., Citation2013), Bandura’s (Citation2004) model fits the context of adolescents and healthy eating, with its components able to explain behaviour. Accordingly, socio-structural factors, immediate and distant, provide facilitators and impediments to healthy living. Unsurprisingly, parents were found to facilitate healthy eating at home, whereas friends encourage consumption of unhealthy foods away from home. There are some noteworthy differences between the two nationalities, which if recognised and addressed, will assist in tackling childhood obesity. Consequently, for the Swedes, schools, sports clubs and the dental health service facilitate positive food socialisation. Their absence from the English discourse suggests opportunities to encourage positive influence from them. Likewise, retailers, including fast food restaurants, feature in the local community where adolescents complete discretionary food purchases. Consequently, research associated with healthy food advertising needs to encompass wider influences, including the socialisation agents i here. These can then be harnessed to encourage behavioural change through establishing popular, healthy social norms (Williams & Littlefield, Citation2018) providing direct competition to those norms portraying HFSS foods as correct/popular.

Triggering healthy eating saliency and relevancy

As for outcome expectations, the research identified that some participants (both nationalities, especially female) were health motivated. For them exercise and healthy eating were associated with physical outcome expectations and self-approval. Although many adolescents speak about long-term health consequences from unhealthy food, healthy eating is given low priority. Food fulfils several functions, with social experiences being especially motivating. Hence, social outcome expectations are significant and unhealthy foods may receive social approval. This finding supports Tarabashkina et al.’s (Citation2017) contention that social norms contribute to the consumption of energy-dense foods (also see Williams & Littlefield, Citation2018). This has implications for Bandura’s (Citation2004) concept of self-efficacy. SCT recognises that knowledge and skills simply represent pre-conditions for change; self-efficacy is required for change to happen. The research reported here suggests yet further complications. Adolescents may believe they possess self-efficacy, but a trigger is required to engage efficacious behaviour. Adolescents’ behaviour towards healthy eating is voluntary (no immediate adverse effects follow from unhealthy foods). The purpose of the trigger would be to increase healthy eating saliency and/or relevancy to provide an environment that boosts individuals’ ability to make healthy choices. The research identified such triggers to include increased share of voice for fruit and vegetables by boosted government advertising, brand building around healthy eating/foods, food advertising rhetoric to reflect the ‘just-enough ideal’ (Johansson et al., Citation2009, p. 47) and visual depictions of, for instance, sugar content.

Adding value through brand development

The Swedish discourse reflected aspects such as organic produce, food miles and home-grown, absent from the English discourse. Both situations suggest brand building potential. For the Swedes, this would happen around concepts of established relevance. For the English respondents, this would involve building relevance around aspects such as ‘locally grown’. In both cases, brand development would add value, with the possibility of building preference (Venturini, Citation2016). Importantly, it would provide a platform for marketing communications. It would also contribute to relationship marketing strategies (Hastings & Saren, Citation2003) and so would add a long-term orientation within a social marketing approach.

Adjusting advertising discourse to a ‘lagom’ approach

Whereas the Swedes perceived food from the ‘just-enough ideal’ (Johansson et al., Citation2009, p. 47) perspective (‘lagom’), the English used a healthy-versus-unhealthy dichotomy. They reported perceiving contradictory expectations. On the one hand, they felt under pressure to be healthy, on the other, peer pressure encouraged consumption of unhealthy foods socially. A social marketing strategy of compromise (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014) by adopting ‘lagom’ within advertising discourse could resonate and offer a more realistic behavioural change proposition.

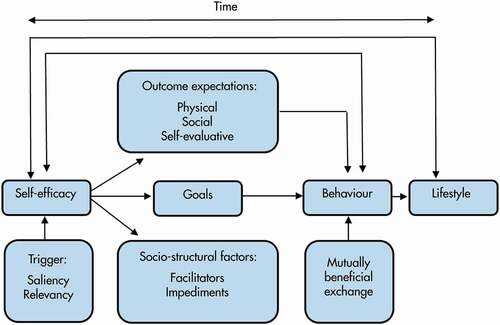

An extended SCT model fit for promoting healthy eating to adolescents

depicts our extended version of Bandura’s (Citation2004) model adapting it to the context of adolescents and healthy eating. The extensions inject social marketing thinking and introduce the additional concepts of saliency and relevancy as ‘triggers’ for self-efficacy. Further, it engenders a consumer orientation (Hastings & Domegan, Citation2014) by recognising the need for a mutually beneficial exchange (Donovan & Henley, Citation2010), offering also a compromise. As indicated by the Scandinavian ‘just-enough ideal’ (Johansson et al., Citation2009, p. 47) and the Swedish participants’ use of the term ‘lagom’, behavioural change that offers flexibility could be more realistic to accomplish and sustain.

Figure 6. Extended model of SCT (adapted from Bandura, Citation2004, p. 146)

Our extended model makes the commitment to strategic marketing thinking explicit. Seeing dietary habits as requiring long-term involvement, it visually introduces relational thinking (Hastings & Saren, Citation2003) and the concepts of time and reinforcement. Hence, over time, successful behavioural change develops into a lifestyle. An efficaciously maintained lifestyle, in turn, strengthens self-efficacy. Additionally, influences are depicted as bi-directional. For instance, successful behaviour verifies and reinforces outcome expectations, raising future goals and associated outcome expectations.

Implications for policy and practice

Analysis of the research findings has resulted in recommendations for advertising and persuasion strategies of relevance to policymakers and advertising practitioners.

In terms of strategic initiatives, this paper recommends:

A government-sponsored increase in advertising of fruit and vegetables, and educational messages to boost health literacy among adolescents. Increased advertising voice for fruit and vegetables will validate and increase consumption (Goldberg & Gunasti, Citation2007) and provide competition to HFSS advertising.

Advertising codes to require that food and drink advertisements targeting young consumers use visual stipulation of sugar, salt and fat content (e.g. sugar content in teaspoon measures). This would provide nutritional information required for an accurate understanding of a food product (Wicks et al., Citation2009) and ensure an informed choice.

The UK Change4Life brand should be extended with a sub-brand, specific to adolescents, to assist development of a long-term healthy lifestyle. This approach would exploit insight into concepts of relational thinking and time revealed in the extended SCT model.

High-quality (informative/creative) health-related advertising messages should be used to encourage persuasion through the central route. Central arguments should be complemented with issue-relevant peripheral cues to keep messages ‘fun’ and prevent message rejection, conforming with Bublitz and Peracchio (Citation2015) recommendation of a dual message strategy promoting both cognitive and affective processing. However, unlike in Bublitz and Peracchio’s communications framework, the participants’ creative activities stress the continued prominence of cognitive appeals and so the positioning remains that of ‘healthy eating’.

Easy-to-understand health appeals that translate complex arguments into ‘real’ (visual) statistics with the power to communicate immediately relevant health benefits (Dooley et al., Citation2010).

Advertisers should steer away from the healthy-versus-unhealthy dichotomy. The Scandinavian ‘just-enough ideal’ (Johansson et al., Citation2009, p. 47) (lagom) could potentially be central, providing an alternative message framing commensurate with the concepts of a mutually beneficial exchange and compromise in the extended SCT model.

Conclusion

Using a social marketing perspective, this study has established how to develop a creative orientation for advertising healthy eating to young consumers by consulting adolescents in England and Sweden. The study was guided by the objectives of establishing how to advertise in ways which will resonate with this age group and how these findings inform SCT. The study drew the following primary conclusions:

Wider engagement of socialisation agents supports the development of healthy social norms,

The ‘lagom’ mindset offers a positive approach to constructing an advertising message,

Age-appropriate behavioural triggers are required to invoke efficacious behaviour,

Branding may be used to develop an identity for currently unbranded healthy foods, which in turn may build preference and loyalty.

Based on the findings, development of the SCT model is proposed. In particular, the ‘lagom’ mindset informs the inclusion of the concept of a compromise.

Future research

A potential limitation of this study is that findings are specific to adolescents at the fieldwork sites. Future research should be conducted at fast food restaurants, food stores, cinemas, etc. to boost insight into facilitators and inhibitors of healthy eating where HFSS foods are purchased and consumed by peers (Tarabashkina et al., Citation2017). The extended SCT model (see ) provides a platform within which to frame this research.

Additional motivating triggers for use in advertising campaigns should be identified. The advertising concepts used by adolescents centred on incentive and threat appeals. Research should establish which approach (including combinations) is more effective at realising behavioural change. Insight is also needed regarding the appropriate strength of threat appeals to catch and hold attention to effectively encourage elaboration of a healthy eating message. The longevity of the relevance of threat appeals and associated risk of wear-out need further investigation.

Finally, future research should explore the viability of the extended SCT model in explaining adolescent behaviour in a digital environment, addressing how new media can promote healthy eating. Chang et al.’s (Citation2015) research with a Facebook-based cooking community found ELM factors played an essential role in persuasion through both central and peripheral routes. Online HFSS advertising in the UK is now bound by the same rules as television (CAP, Citation2016), so the online environment offers an opportunity to develop collective efficacy in adopting healthy eating. Using digital platforms, efficacious adolescents could display their goals and achievements publicly to enhance their self-efficacy and inspire others. Howland et al. (Citation2012) demonstrate how establishing social norms within friendship groups potentially supports healthy eating, even away from the friendship context. They identify such norms as a ‘particularly salient and modifiable environmental factor’ (p. 509) to assist long-term healthy weight maintenance. In the context of the extended SCT model, digital environments offer potential to provide triggers of saliency and relevancy. For instance, government advertising for fruit and vegetables could target hard-to-reach audiences, integrating stakeholders such as governments, schools and sports clubs to synergistic effect. Healthy brands could also act as socialisation agents, encouraging dialogue and engagement, even becoming part of the immediate environment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Maria Sherrington

Anna Maria Sherrington is a Senior Lecturer in Marketing at the University of Central Lancashire where she specialises in social marketing, sustainable marketing and marketing management. Her main research interest is advertising to young consumers with an emphasis on topics related to the conflict between healthy eating and fast food advertising. She has worked in a range of marketing communication positions in the UK, Sweden and Germany, within marketing consultancy, manufacturing industry and the not-for-profit sector. Her research mission is to understand how marketing can be used to address the rapidly growing problem of childhood obesity.

Steve Oakes

Steve Oakes is an Honorary Visiting Fellow in Marketing at the University of Liverpool Management School. He has published in various journals including Psychology & Marketing, Journal of Advertising Research, Marketing Theory, Journal of Marketing Management, Applied Cognitive Psychology, Journal of Marketing Communications, The Service Industries Journal, and Journal of Services Marketing, among others.

Philippa Hunter-Jones

Philippa Hunter-Jones is Professor of Marketing at the University of Liverpool Management School and an Academic Scholar with Cornell Institute for Healthy Futures. She is a qualitative researcher interested in service research. Her interests lie at the intersection of health service research and tourism research. Understanding the experiences of children and young people is a particular focus of her work. Her work has been published in journals such as Annals of Tourism Research, Tourism Management, Journal of Business Research and International Journal of Management Reviews.

Notes

1. Anna and the other names are pseudonyms. The research participants were instructed to select names for the consumers depicted in their collages to allow for personas to develop.

References

- Andreasen, A. R. (1994). Social marketing: Its definition and domain. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 13(1), 108–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569401300109

- Antonetti, P., Baines, P., & Walker, L. (2015). From elicitation to consumption: Assessing the longitudinal effectiveness of negative emotional appeals in social marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(9–10), 940–969. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1031266

- Ball, K., MacFarlane, A., Crawford, D., Savige, G., Andrianopoulos, N., & Worsley, A. (2009). Can social cognitive theory constructs explain socio-economic variations in adolescent eating behaviours? A mediation analysis. Health Education Research, 24(3), 496–506. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyn048

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall International, Inc.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall International.

- Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behaviour, 31(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

- Bandura, A. (2009). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In B. Jennings & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects. advances in theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 94–124). Routledge.

- Banister, E. N., & Booth, G. J. (2005). Exploring innovative methodologies for child-centric consumer research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 8(2), 157–175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750510592436

- Brennan, R., Dahl, S., & Eagle, L. (2010). Persuading young consumers to make healthy nutritional decisions. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(7–8), 635–655. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2010.481177

- Bridges, E., & Briesch, R. A. (2006). The ‘nag factor’ and children’s product categories. International Journal of Advertising, 25(2), 157–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2006.11072961

- Brown, G., & Yule, G. (1983). Discourse analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Bublitz, M. G., & Peracchio, L. A. (2015). Applying industry practices to promote healthy foods: An exploration of positive marketing outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 68(12), 2484–2493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.06.035

- Bucknall, S. (2014). Doing qualitative research with children and young people. In A. Clark, R. Flewitt, M. Hammersley, & M. Robb (Eds.), Understanding research with children and young people (pp. 69–84). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- CAP. (2016, December 8). CAP consultation: Food and soft drink advertising to children. Regulatory statement. Retrieved June 16, 2020, from https://www.asa.org.uk/asset/98337008-FA03-481B-92392CB3487720A8/

- Carter, O. B. J., Patterson, L. J., Donovan, R. J., Ewing, M. T., & Roberts, C. M. (2011). Children’s understanding of the selling versus persuasive intent of junk food advertising: Implications for regulation. Social Science & Medicine, 72(6), 962–968. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.018

- Chan, K., Prendergast, G., Grønhøj, A., & Bech-Larsen, T. (2009a). Communicating healthy eating to adolescents. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 26(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760910927000