Abstract

Despite time being a key element in the theories on international migrants’ socio-spatial mobility, it has not been sufficiently addressed in empirical research. Most studies focus on discrete transitions between different types of neighbourhoods, potentially missing theoretically important temporal aspects. This article uses sequence analysis to study the residential trajectories of international migrants in Sweden emphasising the timing, order, and duration of residence in neighbourhoods with different poverty levels. It follows individuals of the 2003 arrival cohort during their first 9 years in the country. Results show that 81% of migrants consistently reside in the same type of neighbourhood; 60% consistently live in a deprived area and mere 12% follow a trajectories starting at deprived and ending at middle-income or affluent neighbourhoods. Thus, spatial assimilation is neither the only nor the most frequent trajectory followed by migrants in Sweden. Lastly, there are persistent differences in neighbourhood attainment between immigrant groups, suggesting either place stratification or ethnic preference.

Introduction

Immigrants’ settlement patterns and residential mobility in their host country is a growing research field in Europe (Catney & Finney, Citation2012). Researchers’ interest in the topic coincides with widespread concerns over high levels of residential segregation among international migrants (henceforth referred to as ‘migrants’) in many European cities (Tammaru et al., Citation2016). In political debates, the lack of social interaction with the majority population in high ethnic concentration neighbourhoods is considered to hamper migrants’ integration in their host country. Segregation is a prominent issue in political and academic debates in Sweden, not least because of the country’s unprecedented immigration levels during recent years. Since the turn of the 21st century, Sweden has received an average of 100,000 new immigrants every year, resulting in foreign-born individuals now amounting to a sixth of the Swedish population (Statistics Sweden, Citation2018). Levels of residential segregation have been consistently high in Sweden during the last decades. Studies have found that income-based segregation has increased, while ethnic segregation has remained stable or even slightly decreased (Amcoff et al., Citation2014; Andersson & Kährik, Citation2016; Andersson & Turner, Citation2014; Andersson et al., Citation2018; Malmberg et al., Citation2018; Niedomsyl et al., Citation2015; Nielsen & Hennerdal, Citation2017). Although ethnic and socioeconomic segregation cannot be equated, they tend to correspond, as socioeconomically deprived areas are also likely to have a high concentration of foreign-born individuals (Biterman, Citation2010). Several anti-segregation policies have been implemented in Sweden since the 1970s, albeit with limited success. They include a refugee dispersal policy introduced in the mid-1980s and area-based urban programmes which targeted high poverty areas from the 1990s onwards (see Andersson et al., Citation2010 for a detailed overview).

The spatial assimilation theory is an essential reference in the literature on migrants’ socio-spatial mobility. Developed as an extension of the Chicago School assimilation theory (Gordon, Citation1964; Park & Burgess, Citation1921), spatial assimilation contends that international migrants initially settle in rather deprived and immigrant-dense neighbourhoods and, over time, as their socioeconomic situation improves, they relocate to more affluent areas (Massey & Denton, Citation1985; Massey & Mullan, Citation1984). While spatial assimilation focuses on the role played by individual differences in socioeconomic resources, other theories stress the importance of formal and informal discriminatory barriers (e.g. Alba & Logan, Citation1991), and preferences for co-ethnic residence (Clark, Citation2002). Despite time being a key element in the theories on migrants’ residential mobility, the temporal dimension is not sufficiently addressed in empirical research. Usually, the time perspective is incorporated by including the duration of residence in the host country as a predictor in the analysis. Some studies further account for time by analysing the duration until a certain mobility event (using event history models; e.g. Alm Fjellborg, Citation2018; Andersen, Citation2016; Kadarik, Citation2019; Nielsen, Citation2016; Vogiazides, Citation2018). The bulk of the literature on residential mobility, however, focuses on discrete transitions between different types of neighbourhoods. Such an approach may miss theoretically important temporal aspects. First, it overlooks periods of stationarity preceding and succeeding a mobility event. This in turn can result in equating substantially different residential experiences. For example, a move away from a deprived area may occur soon after settlement in that area but also many years later. Similarly, such a move may be followed by a long period of residence in a more affluent neighbourhood or succeeded by a prompt return into a similar type of neighbourhood. The same type of transition may thus be part of residential pathways that give support to different theoretical assumptions. Furthermore, the focus on a specific type of transition, namely from a segregated to a less segregated area, can detract the attention from other types of residential trajectories, such as trajectories that are either characterized by a lack of transition or by a transition going in the ‘opposite’ direction.

Until recently, the possibility to fully capture temporal aspects in residential mobility research was limited by the scarcity of longitudinal data and a lack of accessible methodological tools (Coulter et al., Citation2016). The growing availability of longitudinal data, particularly in the Nordic countries, coupled with recent developments in sequence analysis techniques represents an unprecedented opportunity to incorporate temporal aspects in residential mobility research. Although still low, the number of sequence analysis-based studies on residential mobility is steadily growing. Sequence analysis has been used to describe residential trajectories across regions with different levels of population density in the US (Stovel and Bolan, Citation2004) and the interplay between mobility desires and mobility behaviour in the UK (Coulter & van Ham, Citation2013). The method has also been employed to investigate individuals’ long-term neighbourhood histories in the US (Lee et al., Citation2017), the Netherlands (Kleinepier et al., Citation2018), Sweden (van Ham et al., Citation2014) and Norway (Toft, Citation2018). Finally, a Swedish study applied the method to explore the relationship between housing pathways and housing wealth (Wind & Hedman, Citation2018). To our knowledge, only one study (Kleinepier et al., Citation2018) has so far applied sequence analysis to test spatial assimilation and related theories. This study compares the neighbourhood income trajectories of ethnic minority children and native children in the Netherlands.

Adding to this growing body of literature, this article applies sequence analysis to analyse migrants’ long-term residential mobility in Sweden in a holistic way. It draws inspiration from the time geographical perspective to emphasize patterns of timing, order and duration. The paper analyses migrants’ residential mobility in the light of three theoretical perspectives: spatial assimilation, place stratification and ethnic preference. Its aim is twofold. The first aim is to provide a detailed description of migrants’ typical residential careers across neighbourhoods with different levels of deprivation in Sweden. In this way, the paper addresses the following question: (1) What are the most typical residential trajectories among migrants in Sweden; and how frequent are the patterns of mobility and immobility that support the theories of spatial assimilation, place stratification and ethnic preference? The second aim is to assess how the identified trajectories are predicted by socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. This leads to two research questions: (2) How are migrants’ socioeconomic resources associated with the probability of following an upward residential mobility trajectory, in line with the spatial assimilation theory? (3) Do the probabilities of following advantageous or disadvantageous residential trajectories differ between migrants from different ethnic backgrounds, as postulated by the place stratification and ethnic preference approaches?

The results of this study show that spatial assimilation is neither the only nor the most frequent trajectory followed by migrants in Sweden. Instead, the majority of migrants experience consistent neighbourhood deprivation. In line with previous studies, the empirical findings suggest a combination of spatial assimilation, place stratification and ethnic preference.

Theoretical framework

This study draws inspiration from time geography in order to investigate the residential mobility patterns of international migrants in Sweden.

The ‘space–time trajectory’ (or path) is a core concept in time geography, developed by Swedish geographer Hägerstrand (Citation1985).1 This trajectory is a representation of entities within a continuous and indivisible trajectory over space and time. In this perspective, residential mobility is not conceived as a discrete transition from one neighbourhood to another, but rather as a long-term process across space and time. A trajectory approach allows to analyse residential trajectories as long-term processes where both the timing of mobility and the order of different residential states are of importance. Moreover, by shifting the attention away from discrete moves, this re-conceptualization of mobility also implies a re-valorisation of residential immobility, providing a greater flexibility to uncover the variety in individuals’ residential pathways. Thus, the focus does not only lie on the transition from a segregated to a non-segregated area but also its timing and the duration of stationarity periods that precedes and succeed it. This holistic view of residential careers as space–time trajectories makes this framework particularly useful when evaluating the theories described below.2

A first theoretical explanation of immigrant residential attainment (and the lack thereof) is spatial assimilation, which posits that migrants who initially settled in rather deprived and immigrant-dense neighbourhoods will later relocate to more affluent and native-dominated areas as they assimilate in their host society and their socioeconomic situation improves (Massey & Denton, Citation1985). At the core of the theory is the idea that residential segregation is explained by differences in socioeconomic status between ethnic groups. Thus, the concentration of newly arrived migrants in (often poorer) less desirable neighbourhoods, and the resulting segregation at the aggregate level, is explained by their socioeconomic status being too low to allow them to live in the more desirable neighbourhoods where the majority population tends to reside. The spatial assimilation theory makes two key temporal assumptions. First, it assumes that upward residential mobility occurs after a period of time spent in the host country. Migrants need time in order to accumulate socioeconomic resources that enable them to relocate into more affluent neighbourhoods. According to this view, those residing in deprived and immigrant-dense neighbourhoods have yet to accumulate enough socioeconomic resources in order to progress in the neighbourhood hierarchy. Second, the theory presupposes that migrants’ residence in a non-deprived neighbourhood is preceded by a residential state in a (more) deprived area. Spatial assimilation should therefore be understood as a long-term process where both the timing of mobility and the sequential ordering of different residential states are key elements.

A central criticism of the spatial assimilation theory relates to its inability to explain the long-term segregation of certain ethnic groups, notably African Americans in the US. Two theoretical arguments have emerged to provide competing explanations for the persistence of segregation over time: place stratification and ethnic preference. Developed by Alba and Logan (Citation1991) the place stratification theory argues that structural constraints impede certain ethnic groups from achieving spatial assimilation. Cultural prejudice of the majority population and discriminatory practices in the housing market hinder the possibility of certain minority groups to convert socioeconomic gains into a more advantageous residential situation (Ibid.). In contrast, the ethnic preference approach, argues that a long-term residence in ethnically segregated neighbourhoods may be a voluntary choice.3 Surveys of residential preferences by ethnic group in the US have shown that most people prefer to live in neighbourhoods with significantly large proportions of their own ethnic group (e.g. Clark, Citation2002). For migrants, the preference for ethnic neighbourhoods can be motivated by the availability of certain social networks and ethnic institutions (Peach, Citation1996; Wilson & Portes, Citation1980).

Spatial assimilation and related theories have mainly been tested in the North American context, but the number of European studies on the subject is growing (e.g. Bolt & van Kempen, Citation2010; Feng et al., Citation2014; Kleinepier et al., Citation2018; Lersch, Citation2013; Schaake et al., Citation2014; Silvestre & Reher, Citation2014; Andersen, Citation2010, Citation2016; Nielsen, Citation2016; Turner & Wessel, Citation2013; Valk & Willaert, Citation2012; Wessel et al., Citation2017). Research on migrants’ residential mobility shows evidence of the coexistence of spatial assimilation, place stratification and ethnic preference. Simultaneous support for multiple theories has been found by studies in the US (Krysan & Crowder, Citation2017; Logan et al. Citation2002; Pais et al. Citation2012; Wright et al., Citation2005), the Netherlands (Bolt & van Kempen, Citation2010; Kleinepier et al., Citation2018; Schaake et al., Citation2014;), the UK (Zuccotti, Citation2018), Germany (Lersch, Citation2013) and Sweden (Bråmå, Citation2008; Vogiazides, Citation2018).

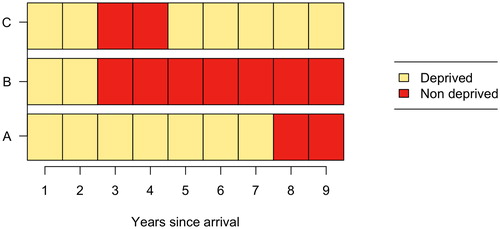

Despite being a central component of the theory, time is often overlooked in empirical research on spatial assimilation. Most studies solely control for the duration of stay in the host country as an independent variable in their models, while focusing on the role of socioeconomic characteristics. Moreover, the vast majority of spatial assimilation studies consider residential mobility in terms of discrete transitions between different types of neighbourhood. However, such an approach runs the risk of equating qualitatively distinct residential careers and experiences. Let us use an example. illustrates three residential careers involving an upward residential move. In scenario A, the person moves away from a deprived neighbourhood after seven years of residence in such a neighbourhood. In scenario B, the person experiences a similar move after only two years spent in the deprived neighbourhood. Finally, in scenario C, the person also relocates to a non-deprived neighbourhood after two years, but she later moves back to a deprived area. The same upward transition can thus be part of distinct residential careers. From a theoretical perspective, scenario A may be considered as a classic case of spatial assimilation, whereas scenario B could be qualified as ‘early spatial assimilation’. Finally, whether scenario C constitutes spatial assimilation can be subject to debate. Applying a trajectory perspective allows us to differentiate between significantly distinct residential experiences and take temporal aspects into account when testing spatial assimilation. Furthermore, by shifting our attention away from single mobility events, we are able to emphasize residential careers characterized by long-term immobility.

Empirical design, data and methods

The study employs sequence analysis to identify typical residential trajectories of international migrants between neighbourhoods with different poverty levels in Sweden. It then uses multinomial regression analysis to estimate the effects of various individual socioeconomic and demographic characteristics on the probability of following each type of trajectory.

Sequence analysis is a set of statistical techniques for the description and classification of data comprised of consecutive discrete states (sequences). It does so by assigning such sequences to clusters, each representing an ideo-typical trajectory in terms of timing, order and duration (the defining features of the study’s trajectory approach to migrants’ residential mobility). Sequence analysis is well suited for describing and analysing migrants’ long-term residential trajectories (Coulter et al., Citation2016) because it takes the entire residential history into account, classifying people based on when, in which order, and for how long they lived in each type of neighbourhood. It therefore allows us to examine the temporal assumptions in the theories of migrants’ socio-spatial mobility, notably the timing of upward neighbourhood transitions, predicted by spatial assimilation, and the duration of immobility in deprived areas preceding such transitions.

This study analyses the residential trajectories of migrants in Sweden over a 9-year period. It uses Swedish register data from the ASTRID database, a database of the entire Swedish population compiled by Statistics Sweden containing longitudinal, annually updated and individual-level data. The database includes a wide range of variables, such as demographic, socioeconomic and housing characteristics. Our study population consists of all international migrants that arrived in Sweden in 2003, who were aged between 25 and 55 and were not living in their parental home at the time of arrival. The exclusion of migrants who lived with their parents aims to ensure that the migrants in the study made their own decisions regarding their housing career. Migrants at retirement age are excluded because their residential mobility is likely to be related to the life-course event of retirement, something that would add further confounding factors to the analysis. The dataset consists of 15,095 individuals whom we followed over a 9-year period, from 2004 to 2012.4

A sequence starts the year after the individual arrives in Sweden5 and ends after 9 years. There are three possible sequence states, each representing a type of neighbourhood according to the poverty level in the neighbourhood of residence. Neighbourhoods are ranked based on their proportion of households at risk of poverty. Risk of poverty in this study corresponds to the EUROSTAT definition of living at 60% of the national median equivalized household income.6 The top third neighbourhoods in terms of proportion of households at risk of poverty are classified as deprived, the bottom third is considered as affluent, and the remaining third is assigned to the middle-income category.

In this study, neighbourhoods are defined using a k-nearest neighbours approach, where each household in Sweden is assigned an individualized neighbourhood composed of the k nearest other households (which may also include both native and foreign-born individuals). Individualized neighbourhoods are computed using the Equipop software based on 100 square metre coordinate grids representing individuals’ residential addresses. This approach has the advantage of avoiding the modifiable areal unit problem, which is a source of statistical bias affecting any geographical analysis based on arbitrarily defined aggregations of geographical areas (Amcoff, Citation2012; Openshaw, Citation1984; Östh et al., Citation2014).7 We set k = 200 when calculating neighbourhoods’ poverty level based on household income. Individualized neighbourhoods were calculated for each year of the follow-up period. It should be noted that the socioeconomic level of individualized neighbourhoods can change over time, due to the selective mobility of the focal individual’s neighbours or changes in the neighbours’ earnings.8 However, as the theories dealt with in this study refer to factors influencing individual mobility behaviour, it is important to ensure that the observations of residential spells are not confounded by contextual changes in the neighbourhoods where the migrants live. Therefore, we have recorded only the changes in neighbourhood type that are due to individuals’ own mobility when measuring individuals’ residential trajectories. The other factors altering the socioeconomic level of a person’ neighbourhoods of residence are beyond the scope of this study.

In order to identify a typology of trajectories, we first calculate the pairwise dissimilarity between all individual sequences in the data. We use the Dynamic Hamming Distance, a dissimilarity measure that accounts for both state type (type of neighbourhood of residence) and the time at which the state occurs; thereby accurately capturing differences in terms of the timing of transitions between the sequences (Lesnard, Citation2010). This was done using the package TraMineR in R (Gabadinho et al. Citation2011). Using these dissimilarities, the sequences are clustered based on a combination of partition around medoids (PAM) and Ward’s hierarchical clustering algorithms. In this procedure, we use the medoids from a hierarchical clustering solution as the starting point for the PAM algorithm in order to obtain a better cluster classification (Studer, Citation2013). The number of clusters was determined following the average silhouette width (ASW) criterion proposed by Rousseeuw and Kaufman (Citation2005) while striving to obtain theoretically meaningful clusters.9 The resulting classification consists of six clusters.10

In a second stage, we use multinomial logit regression to estimate the effect of different individual socio-demographic variables on cluster membership. Both time-constant and time-varying variables are included in the analysis. Categorical time-varying variables such as employment are measured by the proportion of the 9-year sequence that an individual belongs to each category of the variable. Numerical time-varying variables are represented either by the (within individual) mean value (e.g. for income) or by the count of occurrences (e.g. for number of moves) in the 9-year period.

Following spatial assimilation theory, we anticipate that increased socioeconomic resources will lead to a higher neighbourhood attainment. Employment status is a key factor, since integration into the labour market is held to be an important step in the process of assimilation (Massey & Denton, Citation1985). We distinguish three different employment statuses: employed, unemployed and inactive. Employed people include both those employed and self-employed, that is, who appeared in the registers as reporting income and having either a job or a business.11 Unemployed people were those who had neither a job nor a business, but who were receiving unemployment benefits and otherwise taking part in training programmes for the unemployed. Inactive subjects were those who had no employment and no business, and who also did not appear in the registers as receiving unemployment benefits or training, for example full-time students, unemployed people receiving parental benefits or sick benefits. From a spatial assimilation perspective, having a tertiary degree is a measure of human capital, another resource that can be converted into residential attainment (Massey & Denton, Citation1985). Finally, the continuous time-varying variable Income is represented by individuals’ average income over the follow-up period.

The place stratification theory would predict that informal and institutionalized discriminatory practices in the housing market lead to persistent differences in residential mobility patterns between ethnic groups, with the most stigmatized groups (for instance migrants from Africa or the Middle East) being less likely to convert their socioeconomic gains into a more advantageous residential location. On the other hand, the ethnic preference approach would predict a similar outcome due to in-group preferences and benefits from residing near co-ethnics. Therefore, we include a variable Proximity to co-ethnics representing the average proportion of individuals from the same region of birth among the person’s 1600 nearest neighbours. The variable distinguishes 18 regional categories which is the most detailed classification available in the data.12

Following the literature (Ellis et al., Citation2006; South et al., Citation2005; White & Sassler, Citation2000), we also control for having a spouse from the majority group (a Swedish-born spouse).13 Intermarriage is indeed considered to be associated with higher neighbourhood attainment. One reason can be that mixed couples are less vulnerable to discrimination in the housing market. This trend could also reflect a preference from the part of the majority-group spouse to reside among co-ethnics (White & Sassler, Citation2000).

The variable Type of region distinguishes five types of geographical areas—(a) Stockholm, (b) Gothenburg, (c) Malmö (the three metropolitan regions), (d) large city regions, (e) small city/rural regions—which may influence migrants’ residential trajectories.14 The model also controls for the average number of local moves and the average number of inter-regional moves over the follow-up period, since more mobile individuals may have more opportunities for neighbourhood attainment. Finally, the model includes a number of demographic variables such as the time-constant age at arrival and sex, as well as the proportion of time spent with children in the household.

While sequence analysis has a strong descriptive power, it is less suited to causal inference, compared to methods such as event history analysis and panel econometrics (Eerola & Helske, Citation2016). There is a trade-off between being able to make a detailed description of temporal patterns in residential states and making strict causal inferences about predictors. Given that our interest is in having a holistic picture of migrant long-term residential patterns, we favour the descriptive power of sequence analysis over causal estimation capabilities of other methods. A major advantage of our approach is that it allows us to evaluate the relative prominence of different types of residential pathways. More specifically, it informs us on the prevalence of spatial assimilation trajectories in comparison to trajectories of consistent deprivation.

In order to ensure that the classification of sequences reflects temporal patterns in residential mobility, rather than differences in sequence length, we only include migrants who continuously lived in Sweden for a 9-year period. Two issues may potentially arise from this choice. First, it is possible that migrants who remained in Sweden over 9 years may differ from those who emigrated soon after arrival or who spent a year or more abroad in terms of both observed and unobserved characteristics. Such a dataset may not be representative of migrants in general, but only of those migrants who live in the country uninterruptedly. The longer the follow-up, the more selective the sample would be. Yet, it is the residential mobility and immobility of these long-term settlers that is the subject of the theories considered in this article, so we are justified in not including very short trajectories or trajectories that have long spells abroad. Second, conversely, a 9-year period may be too short for migrants to realize the kind of residential attainment that would support spatial assimilation theory, something that may explain why recent studies only find limited support for that theory (e.g. Wessel et al., Citation2017). However, if migrants follow the same patterns as the general population, one may argue that a longer window of observation may not necessarily allow us to observe different mobility patterns, as mobility decreases dramatically with age (Fischer & Malmberg, Citation2001). We believe that a 9-year duration is a good follow-up length, as it allows for some spatial assimilation to happen while minimizing selection due to out-migration or spells of residence abroad. In addition, issues of compatibility between income measurements may also arise when longer time spans are analysed.

Characteristics of the neighbourhood typology

Before turning to the results of the sequence analysis, the present section offers a closer examination of the characteristics and geographical distribution of the three neighbourhood types—deprived, middle-income and affluent—used in the analysis of migrants’ residential trajectories.

The first panel in compares the proportion of each neighbourhood type, by the type of region for two selected years. A first observation is that the proportion of individualized deprived neighbourhoods—i.e. individuals with more than 66% of their closest 200 households being at risk of poverty—is substantially higher in Malmö compared to the rest of Sweden. For instance, it reaches 41% in Malmö in 2012 while it is <20% in Stockholm and Gothenburg. Large city regions and small city/rural regions lie in between with about 36% of individualized deprived neighbourhoods. In addition, over half of the neighbourhoods in Stockholm and Gothenburg belonged to the affluent category in 2012. It is also evident that the distribution of neighbourhood types by region remained relatively stable between 2004 and 2012. The most dramatic change concerns a 3% decrease in the proportion of deprived individualized neighbourhoods in Gothenburg and a 4% decrease of affluent neighbourhoods in Malmö.

Table 1. Proportion of neighbourhoods in each level of poverty by type of region and average neighbourhood characteristics at two selected time points.

The second panel in describes the characteristics of the three categories of neighbourhoods in terms of immigrant density and prominence of rental housing.15 It shows that deprived neighbourhoods have on average a higher proportion of immigrants in general and non-Western immigrants in particular. For instance, in 2004 deprived neighbourhoods over the entire country had on average 3.4% non-Western immigrants, against 2.3% in affluent neighbourhoods. By 2012 those figures were 6.2% and 3.3%, respectively. This confirms that ethnic and socioeconomic segregation tends to co-occur. Although the proportion of immigrants also increased in middle-income areas, its increase was larger in deprived areas. Another clear pattern is that the rental housing is more common in poorer areas. Indeed, in 2012, the proportion of rental dwellings was four times larger in deprived areas compared to affluent ones.

Typical migrant residential trajectories

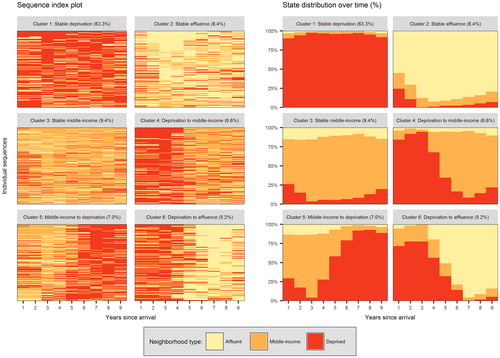

The clustering process identified six types of residential trajectories across neighbourhoods of different poverty levels that are experienced by the migrants who arrived in Sweden in 2003. These six clusters are depicted in . Each neighbourhood category is represented by a colour: red for deprived neighbourhoods, orange for middle-income neighbourhoods and yellow for affluent ones. The horizontal axis denotes the years of residence in Sweden. The left pane shows all individual residential sequences stacked along the y-axis. The y-axis on the right pane shows the proportion of the cluster population residing in each type of neighbourhood. presents descriptive statistics of the principal independent and control variables in our dataset, for the whole study population and by type of residential trajectory.

Figure 2. Sequence index and state distribution plots of migrants’ residential trajectories by cluster.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for the immigrants arriving in Sweden in 2003 (2004–2012; N = 15,095).

A first important result is that stable residential trajectories are far more common than trajectories involving a long-lasting change of neighbourhood status. Over 80% of migrants in the study follow a trajectory characterized by consistent residence in neighbourhoods with the same level of poverty over a 9-year period (Clusters 1–3). A second important finding is that spatial assimilation is neither the only nor the most frequent residential trajectory followed by migrants. In fact, the two clusters that involve an upward residential shift (Clusters 4 and 6) only comprise 12% of the migrants in the study. Cluster 4 involves a transition from a deprived to a middle-income neighbourhood, a shift that occurs after about 4 years. Among the individuals in this cluster, <20% are residing in a deprived area after 5 years. The second type of spatial assimilation trajectory (Cluster 6) consists of a direct ascension from deprived to affluent neighbourhoods (at around year 5), with <20% still residing in other types of neighbourhood at the end of the follow-up period. Consistent with the spatial assimilation theory, migrants following a trajectory of upward mobility have an employment and tertiary degree during a larger portion of the follow-up period compared to those following a trajectory of persistent neighbourhood deprivation. They also have a higher average income and are overrepresented in Stockholm ().

The most frequent residential trajectory, experienced by 63% migrants in the study, is stable neighbourhood deprivation (Cluster 1). Migrants from Africa and the Middle East are overrepresented in this cluster. Migrants in the stable deprivation cluster also reside in Malmö to a larger extent. This is not surprising since the proportion of deprived neighbourhoods is also higher in that region ().

The second most common trajectory is stable residence in a middle-income neighbourhood (Cluster 3), followed by stable neighbourhood affluence (Cluster 2). These trajectories involve 9% and 8% of the migrants, respectively. These clusters thus comprise significantly fewer migrants compared to the ‘stable deprivation’ cluster which involves nearly two-thirds of the migrants. The descriptive statistics in show that migrants in these clusters spend, on average, a larger proportion of their trajectory with a Swedish-born spouse. These two trajectories are also more common among women. Moreover, individuals consistently residing in middle-income or affluent neighbourhoods are less mobile—both over short and long distances—than individuals in the ‘stable deprivation’ cluster.

Finally, Cluster 5, which concerns 7% of individuals, involves a downward residential shift from middle-income to deprived areas after a 5-year period. By year 6, nearly 80% of the migrants in this cluster are living in a deprived area. This trajectory can be characterized as ‘spatial counter-assimilation’ as it goes in the opposite direction than hypothesized by the spatial assimilation theory.

The sequence analysis is not only informative for the clusters that it reveals but also for the residential trajectories that do not appear. For instance, we did not find any cluster where the defining characteristic is the presence of back-and-forth transitions between deprived and middle-income or affluent neighbourhoods, although oscillation between types of neighbourhoods is common in all clusters. Neither does any cluster involve a very early transition away from a deprived neighbourhood, as most transitions out of deprivation occur after 4–5 years on average.

Determinants of migrant residential trajectories

After identifying migrants’ typical residential trajectories in Sweden with sequence analysis, we estimated a multinomial logit model to assess how socioeconomic and demographic characteristics explain those trajectories. Average marginal effects were calculated based on the estimated multinomial logit coefficients and are presented in .

Table 3. Multinomial logit regression of typical residential trajectories in Sweden (2004–2012), average marginal effects and standard errors (N = 14,486).

As predicted by the spatial assimilation theory, we found that a worse socioeconomic status was associated with lower probabilities of upward residential mobility. For example, individuals who were unemployed for their entire residential career were 4.2% less likely to experience upwards mobility from deprived to affluent areas than those who were employed for their entire career. Likewise, unemployment increased the probability of experiencing long-term neighbourhood deprivation. Being unemployed during the entire residential sequence was associated with a 19.9% higher probability of membership in the ‘stable deprivation’ cluster.16 A higher income implied a greater probability of upward residential mobility and a lower probability of consistent residence in deprived neighbourhoods. A 10,000 SEK (about 1100 USD) increase in annual income decreased the probability of stable neighbourhood deprivation by 0.4%. Immigrants with a higher education were more likely to follow residential careers with an upward mobility shift from deprived to affluent neighbourhoods. Having a tertiary degree also seems to steer immigrants away from careers characterized by long-term residence in deprived areas. For example, those who held a tertiary educational degree for the entirety of their trajectory were 6.5% less likely to be in the ‘stable deprivation’ cluster.

While the findings for the socioeconomic variables give support to the spatial assimilation theory, the results point to considerable differences in the likelihood of upward residential mobility between migrant groups, after controlling for socioeconomic and demographic differences. Relative to migrants born in EU15 and Nordic countries, migrants from other regions had a higher probability of persisting neighbourhood deprivation. Migrants from North Africa and the Middle East, for example, had an 18.6 percentage-points higher probability of continuous neighbourhood deprivation. They also had a 3.6 percentage-points lower probability of experiencing an upward transition from a deprived to a middle-income neighbourhood. Migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa showed the same pattern. Considerable inter-migrant group differences in the probability of belonging to more advantageous residential trajectories were also found. For example, compared to EU15 and Nordic migrants, all other migrant groups had a lower probability of stable residence in a middle-income neighbourhood (with the exception of citizens from other OECD countries). The fact that inter-group differences in the probability of following advantageous trajectories remain after controlling for differences in socioeconomic and demographic characteristics suggests evidence of place stratification.

However, the results also provide some support for the idea that the lack of residential attainment by some migrant group may result from a preference for living close to co-ethnics. Indeed, controlling for everything else, a 1% increase in the average proportion of co-ethnics (among the individual’s 1600 closest neighbours) during the residential career, increases the probability of stable residence in a deprived neighbourhood by 6.9%. Nevertheless, proximity to co-ethnics may be a consequence of discrimination in the housing market, rather than a voluntary choice.

When compared to being single for the entire follow-up period, the advantages conferred to immigrants by having a Swedish-born spouse seem to be larger than those of having a foreign-born spouse for the same period. First, migrants with a Swedish-born spouse had a 19.5% lower probability of consistently residing in a deprived neighbourhood, while there is no statistically significant effect of having a foreign-born spouse on that probability. Second, while migrants with a Swedish-born spouse had a 4.1% higher probability of consistent residence in affluent neighbourhoods, that same probability for migrants with a foreign-born spouse was, in contrast, 2.3% lower.

The model controlled for the proportion of the residential career spent in different types of regions in order to adjust for possible housing market differences. Relative to migrants who spent their entire residential career in Stockholm, migrants who consistently resided in other regions have a higher probability of experiencing consistent neighbourhood deprivation. For example, migrants who reside in Malmö during the 9-year follow-up period were 11.7% more likely to follow a trajectory of stable deprivation compared to migrants in Stockholm. The corresponding figure was 10.1% for long-term residents in small city or rural regions. With the exception of Gothenburg, Stockholm is also the region associated with the highest probability of following a trajectory of stable neighbourhood affluence. These results are not surprising since the proportion of affluent areas is highest in these two regions ().

The effects of another set of control variables, the numbers of inter- and intra-regional moves, were also mostly as one would expect. Mobility was generally associated with a higher probability of experiencing a long-lasting change in neighbourhood type. This is not surprising since we constrained sequence states to only change if the person moved. Mobility was also associated with a lower probability of following stable trajectories in middle-income and affluent neighbourhoods. An interesting exception to that trend (and also relevant in relation to our finding that long-term deprivation is prevalent), is the fact that intra-regional mobility did not decrease the probability of belonging to the ‘stable deprivation’ cluster. Indeed, the effect of this variable was not significant, which means that people in the ‘stable deprivation’ cluster were not particularly more mobile than people in any other cluster. Less intuitive, however, is the fact that the number of inter-regional moves increased the probability of persistent neighbourhood deprivation. Previous research shows that international migrants who lack an employment and receive social benefits are more likely to undergo inter-regional mobility (Andersson, Citation2012). Their disadvantaged position could explain why they tend to remain in deprived neighbourhoods.

Finally, demographic variables also had strong effects on migrants’ residential trajectories. Women had a higher chance of consistently residing in affluent or middle-income neighbourhoods and a lower chance of persisting neighbourhood deprivation. Having a child in the household also appeared to be an advantage. Individuals with children were more likely to be in an affluent area at the end of the follow-up period and less likely to experience a downward neighbourhood shift (compared to individuals who did not have children in their household during their entire residential career). Finally, age at immigration also influences residential careers. Compared to migrants who were in the youngest age group (aged 25–34) upon arrival, older migrants were more likely to belong to the ‘stable affluence’ cluster. Yet, they were also less likely to follow a trajectory of upward residential mobility.

We conducted robustness checks with different neighbourhood definitions, different follow-up lengths and with different sequence clustering methods (i.e. optimal-matching and optimal-matching with transition-specific costs). Our results are robust to changes in neighbourhood definition and follow-up lengths. While changing the sequence clustering method leads to changes in the clusters obtained, the method employed in the paper provides the best cluster quality statistics and the best defined clusters of all methods tested.

Conclusions

Discussion

This paper combines a time-geography-inspired conception of residential careers as trajectories with the method of sequence analysis, which is capable of distinguishing temporal patterns that are implied in the theories. Consistent with previous research, the results point to the coexistence of the three main theoretical explanations of migrants’ socio-spatial mobility. However, the paper also provides a number of new insights.

A first important finding based on the sequence analysis is that immigrants’ residential trajectories are mostly characterized by stability in terms of neighbourhood type, with over 80% of immigrants consistently residing in neighbourhoods with the same socioeconomic status. The predominance of stable neighbourhood trajectories is in line with previous sequence analysis-based research (Kleinepier et al., Citation2018; Toft, Citation2018). For example, Kleinepier et al. (Citation2018) similarly found stable neighbourhood trajectories to be the most frequent ones in the case of descendants of immigrants in the Netherlands. Other sequence analysis studies have shown that neighbourhood advantage or disadvantage is transmitted across generations (Toft, Citation2018; van Ham et al., Citation2014). Focusing on the case of Sweden, van Ham et al. (Citation2014) found that individuals who resided in high poverty neighbourhoods during their childhood were very likely to reside in equally poor areas as adults, especially if they belonged to an ethnic minority group.

A second important finding is that the classical spatial assimilation path where migrants move out from deprived neighbourhoods after a certain period of time is a relatively rare residential career (Research question 1). In fact, only 12% of migrants in the study follow an upward residential trajectory, at least within their first 9 years in Sweden. Despite the fact that very few residential trajectories involve a progression towards non-deprived neighbourhoods, the regression analysis provides support for the spatial assimilation theory as a higher socioeconomic position was found to increase the probability of leaving deprived areas.

Third the study shows that the residential careers of the vast majority of newly arrived migrants in Sweden mostly consist of residence spells in deprived neighbourhood (Research question 1). Indeed, over 60% of migrants consistently reside in a deprived area during their first decade in the country.

Fourth, although ‘stable deprivation’ is by far the most dominant trajectory, the sequence analysis also highlighted a certain diversity in the residential trajectories experienced by migrants in Sweden. For instance, it showed two different patterns of spatial assimilation, one going from deprived to middle-income neighbourhoods and another going directly from deprived to affluent neighbourhoods. The sequence analysis also revealed a less-expected trajectory of downward neighbourhood mobility going from middle-income to deprived areas. This trajectory could be characterized as ‘spatial counter-assimilation’ and, just as the trajectories of ‘stable affluence’ and ‘stable middle-income’, it is largely ignored in theoretical discussions. Indeed, a downwards trajectory is not predicted by spatial assimilation theory, neither do socioeconomic resources explain membership in that cluster.

Finally, the sequence analysis highlighted some interesting temporal patterns regarding migrants’ residential trajectories. First, it informed us about the timing of transitions between neighbourhoods with different poverty levels, showing that transitions away from a deprived area (either to middle-income area or an affluent one) typically occur after 4 years of residence in Sweden. Downward shifts from middle-income to deprived areas also take place after the same number of years. Moreover, based on our results, neighbourhood upgrading seems to be long-lasting. Indeed, mobility away from deprived neighbourhoods is not generally followed by a subsequent return to such neighbourhoods (at least not within the time span of the study).

The results of the multinomial logistic regression analysing the determinants of the typical residential trajectories identified in the sequence analysis are consistent with the findings of previous cross-sectional studies of neighbourhood attainment. Indeed, the results provide evidence of each of the three main theories on migrants’ socio-spatial mobility—spatial assimilation, place stratification and ethnic preference—which is a common conclusion in the literature, including in the case of Sweden. Answering our second research question, we found that migrants with a higher socioeconomic position (in the form of income, employment and tertiary education) have a higher probability of following a trajectory involving a lasting neighbourhood upgrading. They are also more likely to experience a trajectory of stable neighbourhood affluence and less likely to experience persistent neighbourhood deprivation. The results thus confirm the main tenets of the spatial assimilation theory and are in line with previous Swedish studies (Andersson, Citation2013; Andersson & Bråmå, Citation2004; Bråmå, Citation2008; Kadarik, Citation2019; MacPherson & Strömgren, Citation2013; Vogiazides, Citation2018). We also found that having a Swedish-born spouse significantly decreases the probability of following the ‘stable deprivation’ trajectory while increasing the probability of membership in the ‘deprived to affluent’ cluster. The positive association between having a Swedish-born spouse and a more advantageous neighbourhood outcomes had been previously documented in other Swedish studies (MacPherson & Strömgren, Citation2013; Vogiazides, Citation2018). These results could be interpreted as a sign that migrants can use their native partners to counter discrimination in the housing market. Indeed, it is reasonable to assume that for mixed couples it is the Swedish-born spouse who takes the lead in the housing search process, being the prime interlocutor with actors such as rental housing companies or bank loaners, thereby reducing risks of discrimination.

Answering the third research question, the study documented considerable differences in residential trajectories between different migrant groups, which remain even after controlling for differences in socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Migrants from Africa and the Middle East are the most likely to experience persistent neighbourhood deprivation and least likely to undergo a transition from a deprived to a middle-income area. Similar between-group differences in neighbourhood attainment were also established in previous research (Andersson, Citation2013; Bråmå, Citation2008; Kadarik, Citation2019; Vogiazides, Citation2018). According to the place stratification theory, this could signify that these relatively stigmatized migrant groups are subject to formal and informal discriminatory practices that keep them from accomplishing upward residential mobility. From an ethnic preference perspective, however, a prolonged residence in deprived, and typically immigrant-dense, neighbourhoods could be the by-product of migrants’ deliberate choice to reside in proximity to other migrants (especially co-ethnics). In line with this explanation, the study finds that immigrants who had a higher exposure to co-ethnics over the follow-up period were more likely to belong to the stable neighbourhood deprivation trajectory. Although this can be an indication of ethnic preference, we need to be careful in our conclusions. First, we use a crude measurement of ethnic groups based on an aggregation of countries of birth, while research in Sweden shows that residential segregation patterns are very sensitive to the aggregation levels used for that variable (Jarvis et al. Citation2017). Second, Swedish research (Hedman Citation2013) has found that the presence of family members is a strong determinant of neighbourhood choice among non-Western migrants. This result suggests that what is interpreted as a preference for proximity to co-ethnics may denote a preference for residing close to family. Furthermore, survey or interview data are needed to better understand individuals’ neighbourhood preferences and reasons for neighbourhood selection (Krysan & Crowder Citation2017).

The relative low rates of spatial assimilation in Sweden may be explained by the country’s socio-political characteristics. The more extensive welfare systems in Western European countries, compared to the US, probably temper the relationship between social and spatial mobility (Turner & Wessel, Citation2013). Wessel et al. (Citation2017) argue that, especially in the Nordic countries, generous redistributive policies can have the effect of reducing the need for spatial assimilation. This is because welfare policies reduce inequalities both between individuals and between neighbourhoods. A more egalitarian society can temper the needs for socioeconomic mobility. For instance, the existence of safety nets such as social and housing benefits implies that entering the labour market may constitute a milder upward move in generous welfare states compared to other contexts. In addition, urban regeneration policies can lift the living standards in high poverty neighbourhoods. If residents are satisfied with the physical infrastructure and services in their neighbourhood, they will be less inclined to relocate, hence the large number of migrants remaining in low income areas.

Policy implications and future research

This study leaves a number of questions unanswered, indicating directions for future research. First, it would be interesting to compare migrants’ residential trajectories to those of natives and migrants’ descendants. Second, one could also analyse the effect of individuals’ residential trajectories on subsequent outcomes, such as in the area of education, employment and health. Third, this study has focused on residential trajectories resulting from the focal individual’s own mobility. It is also worth examining other processes that change the socioeconomic status of the neighbourhood, namely the mobility of other neighbours or changes in the socioeconomic situation of non-moving residents. Do individuals’ residential trajectories differ when these factors are also taken into account? Finally, there is a need for qualitative or survey-based research that investigates individuals’ subjective preferences for certain neighbourhood types.

The findings of the study have a number of implications for housing and migrant integration policy in Sweden and beyond. We have shown that the vast majority of migrants settle in a deprived neighbourhood upon arrival in Sweden and a large proportion of them remain in such a neighbourhood over a long period of time. We also demonstrated that migrants from Africa and the Middle East are more likely to follow such a trajectory compared to migrants from other world regions. Migrants’ persisting neighbourhood deprivation is particularly worrisome in in light of the empirical evidence of negative effects of residential income segregation for socioeconomic integration (see, e.g., Hedberg & Tammaru Citation2013; Musterd et al., Citation2008; Wimark, Haandrikman, & Nielsen, Citation2019). Continued policy efforts to counteract segregation are thus essential. Past experiences have shown that there is no such thing as a simple solution and that actions must take place in multiple policy domains and involve actors at various levels of government (Government Offices of Sweden, Citation2018a). Two sets of policy interventions can be distinguished within housing policy: on the hand, policies that aim to support individuals with a vulnerable position in the housing market and, on the other hand, policies that seek to change the structure of the housing market. Housing allowances are a key component of the policy efforts to strengthen the position of low-income groups on the housing market. However, as recently argued by Andersen et al. (Citation2016), migrants’ disadvantaged position on the housing market may not only be due to a lack of economic resources but also to a lack of knowledge about the functioning of housing market in the host society. Sweden’s rental sector, for instance, is characterized by a complicated system of both public and private rental queues (Christophers, Citation2013). Ensuring that information about the functioning of the housing market reaches newly arrived migrants should therefore be a priority. Policy efforts that seek to change the structure of the housing market usually aim to achieve a mix of tenure forms within neighbourhoods. However, for socioeconomic segregation to decrease, it is also important to ensure an ‘affordability mix’ by increasing the offer of affordable housing in affluent and middle-income neighbourhoods (Alm Fjellborg, Citation2018). Another counter-segregation measure that has been proposed by the Swedish government concerns the introduction of restrictions to the freedom of asylum-seekers to settle in certain municipalities with socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Government Offices of Sweden, Citation2018b). Based on our results, such a measure could be beneficial, provided that good housing alternatives are available in more socioeconomically advantaged areas and that municipalities with good integration prospects are prioritized.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lena Magnusson Turner, Anneli Kährik, Mahesh Somashekhar, Karen Haandrikman, Charlotta Hedberg and Kerstin Westin for their valuable feedback. We are also grateful to three anonymous referees for their constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Forskningsrådet om Hälsa, Arbetsliv och Välfärd (Forte) under Grants 2014–1619 and 2016–07105; and Vetenskapsrådet (VR) under Grant 340-2013-5164. Funding for conference travel was gratefully received from Carl Mannerfelts Fond.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Louisa Vogiazides

Louisa Vogiazides is a PhD candidate in human geography at Stockholm University researching residential mobility, integration and segregation of international migrants in Sweden.

Guilherme Kenji Chihaya

Guilherme Kenji Chihaya is a Migration Sociologist whose current research focuses on residential and labor market integration of international migrants.

Notes

1 Since the early days of time geography, the ‘space–time trajectory’ concept has been repeatedly used to illustrate and analyse individuals’ mobility patterns on a variety of temporal and spatial scales, ranging from daily commuting (e.g. Berg, Citation2016; Elldér, Citation2014; Kwan, Citation2000; Lindkvist Scholten et al., Citation2012; Schwanen & de Jong, Citation2008) to international migration (Frändberg, Citation2008).

2 Coulter et al. (2016) have also recently advocated a longitudinal approach in the study of residential mobility but from a perspective grounded on life-course theory.

3 Positive approaches towards ethnic segregation can be found in the literature under a variety of labels, including the ‘ethnic enclave’ (Wilson & Portes, Citation1980), the ‘ethnic community model’ (Logan et al., 2002), the ‘pluralist model’ (Peach, Citation1997), the ‘cultural preference approach’ (Bolt et al., Citation2008) and the ‘multicultural perspective’ (Bråmå, Citation2008). In this paper, we refer to this strand of literature as the ‘ethnic preference’ approach.

4 The follow-up period in this study starts in 2004 because the income variable used to construct neighbourhoods socioeconomic status has been defined in the same way by Statistics Sweden from that year onward.

5 This ensures the completeness of variables such education and income, which are often missing in the first year for immigrants.

6 The calculation of equivalized household income assigns different consumption weights for adults and children. The first adult in the household is assigned full weight, the second adult is assigned a weight of 0.51, subsequent adults are assigned a weight of 0.60. The first minor is assigned a weight of 0.52, and further minors are assigned weights of 0.42. The sum of all incomes in the household (including social transfers) is divided by this weighted household size, resulting in the disposable household income. The variable used in our study comes from the LISA database and is named DispInkPersF04. The current definition of that variable is available from 2004 onwards, which is why our follow-up period starts on that year.

7 One disadvantage of the k-nearest neighbours approach is that the size of individualized neighbourhoods varies based on population density. In sparsely populated regions, the 200 closest households are thus spread over a larger geographical area than in densely populated areas. Yet, this methodological shortcoming is relatively limited because the vast majority of the Swedish population lives in urban areas (85% in 2010), this methodological disadvantage is relatively limited (Statistics Sweden, Citation2019). Moreover, this study focuses on international migrants who are particularly underrepresented in rural areas. Indeed, three-fourths of the migrants in the study never resided in a small city or rural region during the 9-year follow-up period.

8 Selective migration among the person’s neighbours can change the socioeconomic level of a person’s neighbourhood. The neighbourhood can for instance shift to a lower socioeconomic level if the most affluent neighbours move away and new, less economically advantaged residents move in. In addition, a growing body of neighbourhood dynamics literature reveals that changes in the socioeconomic characteristics of non-migrant residents, the so-called ‘in situ changes’, can also alter the socioeconomic level of a neighbourhood (Andersson & Hedman, Citation2016; Bailey, Citation2012).

9 An ASW between 0.51 and 0.70 suggests that the clusters represent a reasonable structure (Rousseeuw & Kaufman, Citation2005). Our chosen cluster solution had an ASW of 0.62.

10 Sensitivity analyses using different target populations when calculating neighbourhood income, different numbers of categories, different area units and different cut-offs for defining poverty yielded qualitatively similar cluster solutions, but the one presented here is more stable and better at classifying sequences into relatively homogeneous groups.

11 In Swedish registers, individuals’ employment status is measured every year in November.

12 Admittedly, this measure of co-ethnicity is only an approximation of ethnic groups. As Swedish registers do not contain data on ethnicity, country of birth is used as a proxy for ethnicity. This is not an ideal measure for some ethnic groups, such as Kurds, that span several countries, but it is the commonly adopted approach. In addition, several countries of birth are grouped in the ASTRID database, resulting into 18 groups. This measure was calculated using the 'geocontext' Python script (Hennerdal, Citation2018).

13 Married individuals and individuals who cohabit with a child in common can be observed in the register database as being in a union. Our marital status variable is operationalized by identifying the marriage or cohabitation partners of our subjects and their countries of origin. A caveat of this approach is that cohabiting couples without children cannot be identified, meaning that some of our single subjects may actually be in a union. The consequence of this for our analysis is that the estimated effects are conservative and differences between partnered and single individuals are underestimated.

14 This grouping is based on a 2017 classification of municipalities by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SKL in the Swedish acronym). The boundaries of the three largest metropolitan areas correspond to the so-called Labour Market Areas (Lokal arbetsmarknad), which are annually-constructed by Statistics Sweden based on commuting zones, their size and location. The study uses the classification of 2012. It is worth noting that the Labour Market Area of Stockholm and Malmö include the cities of Uppsala and Lund, respectively.

15 Housing tenure was measured using a combination of ownership status and type of housing, retrieved from the building registers. The variable for prominence of rental housing shows the proportion of the 200 closest households that live in public or private rental dwellings. The two immigrant density variables show the proportion of individuals of non-Western/immigrant background among the 400 closest individuals.

16 Interestingly, we found that inactivity (which includes being a full-time student or on sick leave) did not have the same effects on residential careers as unemployment. Compared to being employed, being inactive decreased the likelihood of experiencing an upward transition from deprived to affluent areas. However, it also increased the likelihood of membership in the more advantageous ‘stable affluence’ and ‘stable middle-income’ clusters. So while inactive individuals are less prone to upward residential mobility, they are also more likely to start their residential trajectory in a non-deprived neighbourhood.

References

- Alba, R.D. & Logan, J.R. (1991) Variations on two themes: Racial and ethnic patterns in the attainment of suburban residence. Demography, 28, pp. 431–453.

- Alm Fjellborg, A. (2018) Residential Mobility and Spatial Sorting in Stockholm 1990–2014: The Changing Importance of Housing Tenure and Income (Uppsala: Uppsala University).

- Amcoff, J. (2012) Hur bra fungerar SAMS områden i studier av grannskapseffekter? En studie av SAMS områdenas homogenitet. Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 19(2), pp. 93–115.

- Amcoff, J., Östh, J, Niedomsyl, T., Engkvist, R. & Moberg, U. (2014) Segregation i Stockholms regionen. Kartläggning med EquiPop. Demografisk Rapport, 2014: 09.

- Andersson, E. K., Malmberg, B., Costa, R., Sleutjes, B., Stonawski, M. J. & de Valk, H. (2018) A comparative study of segregation patterns in Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden: Neighbourhood concentration and representation of non-European migrants. European Journal of Population, 34(2), pp. 251–275.

- Andersson, R. (2012) Understanding ethnic minorities' settlement and geographical mobility patterns in Sweden using longitudinal data, In: N. Finney and G. Catney (Eds) Minority Internal Migration in Europe, pp. 263–291 (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate).

- Andersson, R. (2013) Reproducing and reshaping Ethnic Residential Segregation in Stockholm: The role of selective migration moves. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, 95(2), pp. 163–187.

- Andersson, R. & Bråmå, Å. (2004) Selective migration in Swedish distressed neighbourhoods: Can area-based urban policies counteract segregation processes? Housing Studies, 19, pp. 517–539.

- Andersson, R., Bråmå, Å. & Holmqvist, E. (2010) Counteracting segregation: Swedish policies and experiences. Housing Studies, 25(2), pp. 237–256.

- Andersson, R. & Hedman, L. (2016) Economic decline and residential segregation: A Swedish study with focus on Malmö. Urban Geography, 37(5), pp. 748–768.

- Andersson, R. & Kährik, A. (2016) Widening gaps: Segregation dynamics during two decades of economic and institutional change in Stockholm, in: T. Tammaru, S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham & S. Musterd (Eds) Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities: East Meets West, pp. 110–131 (Oxford: Routledge).

- Andersson, R. & Turner, L.M. (2014) Segregation, gentrification, and residualisation: From public housing to market driven housing allocation in inner city Stockholm. European Journal of Housing Policy, 14(1), pp. 3–29.

- Andersen, H. S. (2010) Spatial assimilation in Denmark? Why do immigrants move to and from multi-ethnic neighbourhoods. Housing Studies, 25(3), pp. 281–300.

- Andersen, H. S. (2016) Spatial assimilation? The development in immigrants’ residential career with duration of stay in Denmark. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 31, pp. 297–320.

- Andersen, H. S., Andersson, R., Wessel, T. & Vilkama, K. (2016) The impact of housing policies and housing markets on ethnic spatial segregation: Comparing the capital cities of four Nordic welfare states. International Journal of Housing Policy, 16(1), pp. 1–30.

- Bailey, N. (2012) How spatial segregation changes over time: sorting out the sorting processes. Environment and Planning A, 44, pp. 705–722.

- Berg, J. (2016) Everyday Mobility and Travel Activities during the first years of Retirement. (Linköping: Linköping University Electronic Press).

- Biterman, D. (2010) Segregationsutveckling i storstadsregioner. [Development of Segregation in Metropolitan Regions] Social Rapport 2010, pp. 177–195 (Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen).

- Bolt, G. & van Kempen, R. (2010) Ethnic segregation and residential mobility: Relocations of minority ethnic groups in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(2), pp. 333–354.

- Bolt, G., van Kempen, R. & van Ham, M. (2008) Minority ethnic groups in the Dutch housing market: Spatial segregation, relocation dynamics and housing policy. Urban Studies, 45(7), pp. 1359–1384.

- Bråmå, Å. (2008) Dynamics of ethnic residential segregation in Göteborg, Sweden, 1995–2000. Population, Space and Place, 14(2), pp. 101–117.

- Catney, G. & Finney, N. (2012) Minority internal migration in Europe: Key issues and contexts, in: N. Finney & G. Catney (Eds) Minority Internal Migration in Europe, pp. 313–327 (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate).

- Christophers, B. (2013) A monstrous hybrid: The political economy of housing in early twenty-first century Sweden. New Political Economy, 18(6), pp. 885–911.

- Clark, W. A. V. (2002) Ethnic preferences and ethnic perceptions in multi-ethnic settings. Urban Geography, 23(3), pp. 237–256.

- Coulter, R. & van Ham, M. (2013) Following people through time: An analysis of individual residential mobility biographies. Housing Studies, 28(7), pp. 1037–1055.

- Coulter, R., van Ham, M. & Findlay, A. M. (2016) Re-thinking residential mobility: Linking lives through time and space. Progress in Human Geography, 40(3), pp. 352–374.

- Eerola, M. & Helske, S. (2016) Statistical analysis of life history calendar data. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 25(2), pp. 571–597.

- Elldér, E. (2014) Residential location and daily travel distances: The influence of trip purpose. Journal of Transport Geography, 34, pp. 121–130.

- Ellis, M., Wright, R. & Parks, V. (2006) The immigrant households and spatial assimilation: Partnership, nativity, and neighbourhood location. Urban Geography, 27(1), pp. 1–19.

- Feng, Z., van Ham, M., Boyle, P. & Raab, G.M. (2014) A longitudinal study of migration propensities for mixed-ethnic unions in England and Wales. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(3), pp. 384–403.

- Fischer, P. A. & Malmberg, G. (2001) Settled people don't move: On life course and (im-)mobility in Sweden. Population Space and Place, 7(5), pp. 357–371.

- Frändberg, L. (2008) Paths in transnational time‐space: Representing mobility biographies of young swedes. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 90(1), pp. 17–28.

- Gabadinho, A., Ritschard, G., Mueller, N. S. & Studer, M. (2011) Analyzing and visualizing state sequences in R with TraMineR. Journal of Statistical Software, 40(4), pp. 1–37.

- Gordon, M. (1964) Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion and National Origins (New York: Oxford University Press).

- Government Offices of Sweden. (2018a) Regeringens långsiktiga strategi för att minska och motverka segregation. [The Swedish Government’s Long-Term Strategy to Reduce and Counteract Segregation.] (Stockholm: Regeringskansliet).

- Government Offices of Sweden (2018b) Ett socialt hållbart eget boende för asylsökande [A Socially Sustainable Own Accommodation for Asylum Seekers.] (Stockholm: Regeringskansliet).

- Hägerstrand, T. (1985) Time-Geography. Focus on the Corporeality of Man, Society and Environment. The Science and Praxis of Complexity, pp. 193–216 (Tokyo: The United Nations University).

- Hedberg, C. & Tammaru. T. (2013) ‘Neighbourhood effects’ and ‘City effects’: The entry of newly arrived immigrants into the labour market”. Urban Studies, 50(6), pp. 1163–1180.

- Hedman, L. (2013) Moving Near Family? The Influence of Extended Family on Neighbourhood Choice in an Intra-urban Context. Population, Space and Place, 19, pp. 32–45.

- Hennerdal, P. (2018) geocontext, GitHub repository, https://github.com/PonHen/geocontext.

- Jarvis, B., Kawalerovicz, J., Valdez, S. (2017) Impact of ancestry categorisations on residential segregation measures using Swedish register data. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 45(Suppl 17), pp. 62–65.

- Kadarik, K. (2019) Moving out, moving up, becoming employed: Studies in the residential segregation and social integration of immigrants in Sweden. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Kleinepier T., van Ham, M. & Nieuwenhuis, J. (2018) Ethnic differences in timing and duration of exposure to neighborhood disadvantage during childhood. Advances in Life Course Research, 36, pp. 92–104.

- Krysan, M. & Crowder, K. (2017) Cycle of Segregation. Social Processes and Residential Stratification (New York: Russel Sage Foundation).

- Kwan, M.-P. (2000) Gender differences in space-time constraints. Area, 32(2), pp. 145–156.

- Lee, K. O., Smith, R. & Galster, G. (2017) Neighborhood trajectories of low-income US households: An application of sequence analysis. Journal of Urban Affairs, 39, pp. 335–357.

- Lersch, P.M. (2013) Place stratification or spatial assimilation? Neighbourhood quality changes after residential mobility for migrants in Germany. Urban Studies, 50(5), pp. 1011–1029.

- Lesnard, L. (2010) Setting cost in optimal matching to uncover contemporaneous socio-temporal patterns. Sociological Methods & Research, 38(3), pp. 389–419.

- Lindkvist Scholten, C., Friberg, T. & Sandén, A. (2012) Re-reading time geography from a gender perspective: examples from gendered mobility. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 5, pp. 584–600.

- Logan, J. R., Zhang, W. & Alba, R. D. (2002) Immigrant enclaves and ethnic communities in New York and Los Angeles. American Sociological Review, 67(2), pp. 299–322.

- MacPherson, R. & Strömgren, M. (2013) Spatial assimilation and native partnership: Evidence of Iranian and Iraqi immigrant mobility from segregated areas in Stockholm, Sweden. Population, Space and Place, 19(3), pp. 311–328.

- Malmberg, B., Nielsen, M. M., Andersson, E. K. & Haandrikman, K. (2018) Residential segregation of European and non-European migrants in Sweden 1990–2012. European Journal of Population, 34(2), pp. 169–193.

- Massey, D. & Mullan, B. (1984). Processes of Hispanic and Black spatial assimilation. American Journal of Sociology, 89(4), pp. 836–873.

- Massey, D. S. & Denton, N. (1985) Spatial assimilation as a new socio-economic outcome. American Sociological Review, 50(1), pp. 94–106.

- Musterd, S., R. Andersson, G. Galster & T.M. Kauppinen. (2008) Are immigrants’ earnings influenced by the characteristics of their neighbours? Environment and Planning A, 40(4), pp. 785–805.

- Niedomsyl, T. & Östh, J., Amcoff, J. (2015) Boendesegregationen i Skåne (Kristianstad: Region Skåne).

- Nielsen, M. & Hennerdal, P. (2017) Changes in the residential segregation of immigrants in Sweden from 1990–2012 using a multiscalar segregation measure that accounts for the modifiable areal unit problem. Applied Geography, 87, pp. 73–84.

- Nielsen, R. S. (2016) Straight-line assimilation in home-leaving? A comparison of Turks, Somalis and Danes. Housing Studies, 31(6), pp. 631–650.

- Openshaw, S. (1984) The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (Norwich: GeoBooks.CATMOG 38).

- Östh, J., Malmberg, B. & Andersson, E. (2014) Analysing segregation with individualized neighbourhoods defined by population size, in: C. D. Llyod, I. Shuttleworth & D. Wong (Eds) Social-Spatial Segregation: Concepts, Processes and Outcomes, Ch. 7, pp. 135–161 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press).

- Pais, J., South, S. J. & Crowder, K. (2012) Metropolitan heterogeneity and minority neighbourhood attainment: Spatial assimilation or place stratification? Social Problems, 59(2), pp. 258–281.

- Park, R. E. & Burgess, E. W. (1921) Introduction to the Science of Sociology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

- Peach, C. (1996) Good segregation, bad segregation. Planning Perspectives, 11, pp. 379–398.

- Peach, C. (1997) Pluralist and assimilationist models of ethnic settlement in London 1991. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 88(2), pp. 120–134.

- Rousseeuw, P. J. & Kaufman, L. (2005) Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley).

- Schaake, K., Burgers, J. & Mulder, C. H. (2014) Ethnicity, education and income, and residential mobility between neighbourhoods. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(4), pp. 512–527.

- Schwanen, T. & de Jong, T. (2008) Exploring the juggling of responsibilities with space-time accessibility analysis. Urban Geography, 29(6), pp. 556–580.

- Silvestre, J. & Reher, D. S. (2014) The internal migration of immigrants: Differences between one-time and multiple movers in Spain. Population, Space and Place, 20, pp. 50–65.

- South, S. J., Crowder, K. & Chavez, E. (2005) Geographical mobility and spatial assimilation among U.S. Latino immigrants. International Migration Review, 39(3), pp. 577–607.

- Statistics Sweden. (2018) Immigrations by sex and year. Available at http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101J/Flyttningar97/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=ceb2f2f0-8430-46d5-bc6f-7ed096a1e5a8 (accessed 26 December 2018).

- Statistics Sweden. (2019) Folkmängd och landareal i och utanför tätorter, efter region. Vart femte år 2005-2015 [Population and land area in and outside urban areas, by region. Every fifth year 2005–2015]. Available at http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__MI__MI0810__MI0810A/BefLandInvKvmTO/?rxid=9963b46f-8d43-4df7-89dd-8fd5e4f421c2 (accessed 5 May 2019).

- Stovel, K. & Bolan, M. (2004) Residential trajectories. Using optimal alignment to reveal the structure of residential mobility. Sociological Method and Research, 32(4), pp. 559–598.

- Studer, M. (2013). WeightedCluster Library Manual: A Practical Guide to Creating Typologies of Trajectories in the Social Sciences with R. LIVES Working Papers, 24.

- Tammaru, T., Marcinczak, S., van Ham, M. & Musterd, S. (2016) A multi-factor approach to understanding socio-economic segregation in European capital cities, in: T. Tammaru, S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham & S. Musterd (Eds) Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities: East Meets West, pp. 1–29 (Oxford: Routledge).