Abstract

Against the background of the current housing affordability crisis, a new wave of ‘collaborative housing’ (CH) is developing in many European cities. In this paper, CH refers to housing projects where residents choose to share certain spaces and are involved in the design phase. While many authors point to the alleged economic benefits of living in CH, the (collaborative) design dimension is rarely mentioned in relation to affordability. This paper seeks to fill this knowledge gap by identifying design criteria used in CH to reduce building costs, increasing this way its affordability. We carry out a comparative case study research, where we assess the design phase of 16 CH projects in different European cities. Findings suggest that collaborative design processes increase the chances of improving housing affordability, mainly due to the often-applied needs-based approach and the redefinition of minimum housing standards.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.2009778 .

1. Introduction

New models and institutions have emerged to tackle the housing affordability crisis over the past decades. These comprise innovative hybrid arrangements, where public agencies and private and not-for-profit actors collaborate (Czischke & van Bortel, Citation2018; van Bortel & Gruis, Citation2019). These collaborative processes include the citizens’ involvement in the provision of their housing and are increasingly encouraged due to their alleged benefits.

In line with the above, collaborative housing (CH) has been (re)gaining momentum in the past years in many European countries and referred to as a ‘new wave’ (Sandstedt & Westin, Citation2015, p. 134) or ‘third wave’ (Williams, Citation2005, p. 202). Despite the lack of reliable statistics on the number of people living in CH in the countries under study, studies estimate a growing demand for these housing types, particularly amongst seniors and young families (Lang et al., Citation2019).

Scholars define CH as including a wide range of housing forms, such as cohousing, residents’ cooperatives, self-building initiatives, among others (Fromm, Citation1991; Lang et al., Citation2019; Vestbro, Citation2010). These forms are often collectively self-organised and based on ‘a significant level of collaboration amongst (future) residents, and between them and external actors and stakeholders, with a view to realizing the housing project (Czischke et al., Citation2020). Additionally, the shared intention of the users to live together (Vestbro, Citation2010) is usually reflected in the housing layout, where private units are complemented by collective spaces (Fromm, Citation2012; Jarvis, Citation2011; Vestbro, Citation2010). In short, in this paper, CH refers to projects characterised by resident participation and collaboration with professionals in the design phase, aimed at creating housing projects in which residents intentionally share spaces.

Examples of CH initiatives seeking affordable and sustainable solutions include Baugruppen in Germany and Austria, Habitat Participatif in France, Community Land Trusts (CLTs) in England, Belgium and more recently in France (called ‘Organismes Foncieres Solidaires’- OFS), and new residents’ cooperatives in Spain or Switzerland (Czischke, Citation2018). In recent years, a new scholarly strand has developed within the CH field, mainly ‘focused on emerging CH models and their innovative and radical potential to address the lack of affordable housing options.’ (Lang et al., Citation2019, p. 13). Research alleging the economic benefits of providing CH mainly focuses on how certain approaches can contribute to reducing costs through co-production (Czischke, Citation2018), innovative land access or acquisition (Aernouts & Ryckewaert, Citation2017; Cabré & Andrés, Citation2017; Chatterton, Citation2013; Engelsman et al., Citation2018; Paterson & Dunn, Citation2009), collective ownership (e.g. cooperatives) (Archer, Citation2020; Cabré & Andrés, Citation2017) and collective self-management and -governance (Archer, Citation2020; Jarvis, Citation2011; Williams, Citation2005). However, little attention has been paid to how the design of CH influences affordability, notably due to its potential to reduce building costs.

High building costs are widely acknowledged as posing severe challenges to the provision of affordable housing (Pittini et al., Citation2017; Wetzstein, Citation2017). Woetzel (Citation2014, p. 5) suggests that ‘developing and building housing at lower cost’ and ‘operating and maintaining properties more efficiently’ are possible approaches to narrow the current affordability gap. However, building low-cost housing is not enough to provide affordable housing. In the past, design approaches such as Existenzminimum (minimum dwelling) showed that certain design criteria helped deliver affordable housing by reducing building costs while improving its quality. Today, a renewed interest in Existenzminimum is expressed in innovative minimum dwelling solutions as a way to provide affordable housing and increase social interaction (Brysch, Citation2019; Ruby & Ruby, Citation2011), combining small and less-equipped private units with collective and flexible spaces.

CH often shares these spatial features, with the difference that design decisions are taken collectively, reflecting the specific needs and demands of the residents’ group. This collective design process may in itself indirectly affect final costs due to factors such as in-kind investment by future residents and the redefinition of roles due to its self-organisation. Thus, under specific conditions, the design phase in CH is likely to play an important role in reducing building costs and – consequently – increasing affordability. Building costs are understood here as expenditures incurred during the design and construction of a housing project.

In this paper, we assess affordability at a project-level and in line with a recent research strand committed to broadening the concept by including other values that transcend the economic focus, such as quality, sustainability, and community building (Mulliner et al., Citation2013). Indeed, the concept of affordability is concerned not only with prices or rents and incomes but also with quality standards (Haffner & Heylen, Citation2011; Maclennan & Williams, Citation1990). This does not imply that affordability could no longer be assessed, but rather it cannot be accurately measured and compared. At the same time, our understanding of housing goes beyond the market-driven and capitalist perspective that considers it purely an object, an asset. We follow Turner’s premise that housing is both a product (object, a noun) and a process (subject, a verb) (Turner, Citation1972), inseparable from each other. Accordingly, we look at both factors that influence building costs related to the design outcome (‘the building as a product’) and the design process.

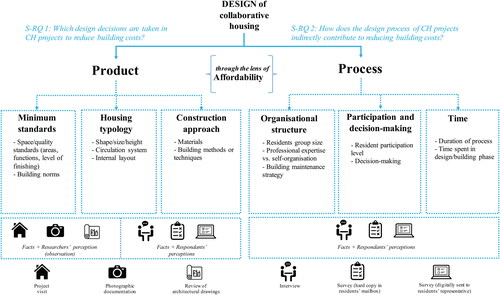

The aim of this paper is to identify the design criteria that may reduce building costs in CH projects and, consequently, increase affordability. The main research question ‘Which design criteria are used in CH to increase affordability?’ is followed by two sub-questions, namely ‘Which design decisions are taken in CH projects to reduce building costs?’ and ‘How does the design process of CH projects indirectly contribute to reducing building costs?’. Our method consists of an international comparative case study, where we assess the design phase of 16 recent CH European projects in which affordability has been referred to as a key driver. To this end, we developed an analytical framework to evaluate the factors that influence building costs in CH. We employed this to refine the operational questions we formulate throughout Section 3 for the analysis of the empirical findings from the case studies.

Fieldwork was carried out between May and July 2018 and April and August 2019 in 12 European cities. Primary and secondary data provided factual data about the project (product and process-wise) as well as perceptions on the affordability of the project. Findings, therefore, combine survey-respondents and interviewees’ perceptions with researchers’ observation and review of the literature and architectural plans.

This paper is structured as follows: first, we describe our methodological approach and list the selection criteria of the case studies. We then propose an analytical framework to identify the design criteria that may influence building costs in CH. This is followed by a section where we present and discuss our findings, after which we conclude by outlining further steps for our research.

2. Methodological approach

This research adopted an international comparative case study approach to provide an overview of the design process of recently built CH projects in 12 European cities, namely Stockholm and Malmö (Sweden), Helsinki (Finland), Odense and Albertslund-Copenhagen (Denmark), Berlin and Hamburg (Germany), Amsterdam (The Netherlands), Vienna (Austria), Lyon (France), Milan (Italy), and Barcelona (Spain).

Despite their different geographies, all these countries are bound by the same EU directives in environmental sustainability (e.g. Energy Efficiency Index, integration of environmental aspects into European standardisation, etc.) and base their housing provision on regulations for space and quality (minimum) standards. While in some countries, CH initiatives have long-established practices (Sweden and Denmark are the birthplaces of some models), in others, CH has recently developed to tackle the housing affordability crisis (e.g. Spain, France). By covering 16 projects located in the south, central and north Europe, the study sought to bring together a rich diversity of cultural, geographical, and housing systems. The criteria used to select the cases were the following:

Be the result of a collaborative design process (i.e. a collaboration between residents and professionals);

Combine private units with collective spaces;

Be a recently completed project (after 2000);

Be referred to as having affordability as (one of) the project’s main driver(s).

The cases were identified through literature review, internet websites, and personal contacts. Fieldwork took place between May and July 2018 and April and August 2019. It consisted of project visits, photographic documentation, a (web-)survey (average duration of 15–20min) sent to the residents of the projects, and interviews (average duration of 1 h) or informal conversations with residents, architects, and facilitators involved in the design phase. In parallel, secondary sources were reviewed, such as architectural drawings and websites of the respective projects. Appendix 1, Supplementary material lists the selected cases and the data collection methods applied to each case.

Residents’ and architects’ input was relevant to a) uncovering physical features undetectable through the review of the architectural drawings, visits, and photographic documentation; and b) grasping the residents’ perceptions regarding the suitability of the project to their needs and expectations and their notion of minimum quality. Input from architects, facilitators, and residents involved in the design phase was useful to a) gather both information and impressions about the design process (participation level, time, decision-making methods); and b) identify which design factors were perceived as the most influential in affecting the affordability of the project.

The interviews (input from 33 individuals; see Appendix 1, Supplementary material for break-down by case) followed two formats. In 2018, the interviews were conducted according to a more conventional semi-structured approach. In 2019, the respondents were presented with four ‘flashcards’ at the beginning of the interview, each of them related to a pre-defined key theme: (1) design & construction process, (2) final outcome, (3) affordability, and (4) setbacks. They were asked to comment on these topics and answer open-ended questions regarding the housing projects they were involved. This strategy framed and guided the whole interview, avoiding deviations from the subject and allowing a more natural narrative.

The survey was translated into English, German, French, Italian and Spanish and distributed accordingly to the residents either digitally (web-survey) or as a hard-copy (letter in the mailbox) during the project visits. The survey questions were mainly multiple-choice and were related to the abovementioned four key topics. Out of the questionnaires sent to the 16 cases (a total of 845 households: 134 as hard-copy and 11 digitally sent to the contact person, who would forward it to the residents), we received 84 responses (see Appendix 1, Supplementary material for break-down by case). The survey is (statistically) not representative, as the responses are scarce and uneven from case to case. Yet, it provides relevant input for the research: for instance, it uncovers that not all residents had participated in the design process, as they joined the project at a later stage. Moreover, input from the 84 residents that replied to the survey is useful to assess findings related to the product. In contrast, information from residents involved in the design process that replied to the survey, 50 out of 84, is considered to analyse process-related findings. In each project (except for two cases), at least one resident claims no cost savings by living there.

3. Analytical framework: identifying the design criteria influencing building costs in collaborative housing

This paper seeks to provide a theoretical and qualitative assessment of affordability in CH, focusing on the design phase and its impact on building costs. We propose an analytical framework to understand affordability at a project-level from the perspective of the design process (subject/social level) and the consequent product (object/spatial and technical level) as inseparable parts of a whole: housing. Building on Brysch (Citation2019), who analyses housing affordability in relation to design through the concept of Existenzminimum, we consolidate the framework through a literature review on building costs, participation, and self-organisation in housing.

Literature on mainstream housing mainly connects building costs with typological issues, namely the building configuration, and with construction approaches. Simple shapes with 5 to 6 storeys are less expensive to build (Belniak et al., Citation2013; Chau et al., Citation2007; Seeley, Citation1983). Prefabrication and standardisation are widely described as cost-savers, as they are based on low production costs and speed in assembling (Brysch, Citation2019; Seeley, Citation1983). Flexibility also can positively impact final costs (De Paris & Lopes, Citation2018; Slaughter, Citation2001). The choice of materials also influences building costs, considering their quality and their sustainability level. Minimum quality standards, established to guarantee dignified housing, prevent building situations under the set limits. Besides regulatory standards (e.g. have at least one bathroom with a bathtub, or parking lots), ‘socially-acceptable’ minimum standards are also considered to meet mainstream cultural expectations (e.g. include laundries in private units). Architectural design plays, therefore, an essential role in providing housing solutions where costs and quality do not compromise each other (Brysch, Citation2019).

Current research on the development and design of CH focuses on resident ‘participation’ and collective ‘self-organisation’ (Czischke, Citation2018; Ruiu, Citation2016), where residents often take on roles of housing professionals (Duncan & Rowe, Citation1993; Palmer, Citation2019). This collective process raises the issue of ‘time’, not only spent on voluntary tasks but also on issues related to the level of participation, decision-making, and conflict (Jarvis, Citation2011; Williams, Citation2005), which affects the duration of the whole process and influences the final product.

Our framework distinguishes six factors that might influence building costs in CH: (1) minimum standards, (2) housing typology, (3) construction approach, (4) organisational structure, (5) participation and decision-making, and (6) time. While the first three are linked to the product, the last three are related to the collaborative design process. Yet, they are all interconnected and often overlap. The general approach to ‘minimum (quality) standards’ influences the building configuration (‘typology’), which is then materialised through a certain ‘construction approach’. These factors apply to housing in general, but their link to a collaborative design process makes them specific to CH, as residents’ ‘participation’ is the crucial factor determining the final decisions on those product-related factors. The ‘organisational structure’ of the process, based on collective self-organisation, includes the voluntary execution of tasks by the residents, for instance, self-building, creating a link with the ‘construction approach’. The ‘time’ that is dedicated or offered (i.e. spent in working hours) by the residents in the design phase may impact the level of ‘participation’, which then influences final design decisions (at product level) and associated costs. Therefore, rather than ‘quantifying’ the relevance of each factor, we aim at identifying the factors that, in combination with each other, create an impact on building costs.

Other project-level factors that may indirectly influence design decisions are land acquisition costs, financial mechanisms, or tenure types. Examples include subsidies to build energy-efficient buildings or land lease agreements that reduce the financial burden, allowing more design options. However, this study focuses on the factors immediately linked to the design process.

Next, we discuss these six factors in more detail and derive operational questions concerning their potential impact on building costs in the specific case of CH. outlines the proposed analytical framework and illustrates the applied methods to provide input to each one.

3.1. Minimum standards

Within the legal possibilities - or sometimes contesting them -, residents themselves define their own minimum ‘threshold’ in CH projects concerning space and quality standards (areas, domestic functions, level of finishing). According to the values they prioritize, residents also define their own set of ‘socially-acceptable’ standards. In this sense, CH contrasts with mainstream housing, where housing is delivered as a finished product according to conventional standards and established expectations. First, the built form of CH reflects the decisions that are (collectively) made during the design process to accommodate the exact required space as a direct result of their needs and aspirations. Second, residents of CH often move into an unfinished building, with spaces and surfaces to be completed later. Third, in CH, it is common to ‘strip all nonessential or infrequent space needs out of the individual dwelling’ (Jarvis, Citation2011, p. 567) and reduce the area of the private units (Jarvis, Citation2011; Williams, Citation2005) to the (legally accepted) minimum. This allows to include collective spaces without an increase in construction costs (Vestbro, Citation2008). However, the simple reduction and ‘transference’ of a private area to a bigger collective one do not necessarily reduce costs since the higher costs are usually at the infrastructure and services level (Hellgardt, Citation1987). It is the number of appliances or in the private sphere that needs to reduce to save costs.

So, the question arises: How are space and quality standards perceived and applied in CH, and how do they affect building costs?

3.2. Housing typology

In a similar way to mainstream housing, the building costs of CH are also influenced by the configuration, shape, and height of the building. The internal layout of CH is often based on small private units combined with collective spaces (sometimes also made available to the wider neighbourhood. Also, many CH examples are based on the high flexibility and adaptability of spaces to allow different uses. Circulation systems such as interior cores (staircase and elevator) are usually chosen due to their compact and effective spatial distribution. Yet, galleries are also often used as a design strategy to compensate for the reduced areas of private units without increasing the overall surface area. They are occasionally merged with ‘private’ balconies and assume the function of meeting spaces. Therefore, a correct balance between private and collective is relevant to keeping costs under control and promoting values such as social interaction, sharing and community building.

This leads us to the question: What kind of (typological) design decisions and compromises are made in CH to reduce final building costs?

3.3. Construction approach

In CH projects, the building is often not considered a finished product but rather an ongoing process, as the end-users can change and expand their housing units. These approaches resonate with the concepts of open building (Habraken & Teicher, Citation1972), further developed by Frans van der Werf, and incremental housing (Aravena & Iacobelli, Citation2012). Unfinished surfaces, unpainted walls, unassembled kitchen cabinets and window blinds are examples of construction elements to be completed by the residents upon their arrival through ‘self-building’ and DIY (Do-it-yourself) or DIT (Do-it-together) processes (Brysch, Citation2018). Duncan and Rowe (Citation1993) point to the potential of self-provision and self-building in reducing costs due to labour savings in construction works and white-collar tasks and the absence of speculative profit. In this paper, the term self-building is used to describe hands-on construction tasks carried out by some residents. On the other hand, CH is often characterised by its ‘custom-made solutions’ (Tummers, Citation2016, p. 2024) and decisions about materials or are often made to achieve higher environmentally-friendly and energy-efficiency standards (Tummers, Citation2016).

The above raises the questions: To what extent can these alternative construction approaches reduce the overall building costs in the particular case of CH? What are the design trade-offs to ensure these high standards and keep costs down?

3.4. Organisational structure

Self-organisation is usually a key feature of a CH project. This may impact costs since the residents’ group voluntarily takes on tasks traditionally undertaken by professionals, namely the developer (Palmer, Citation2019) or builders and contractors (Duncan and Rowe, Citation1993). This ‘sweat equity’ of unpaid work implies a redistribution among residents of roles and responsibilities (Czischke, Citation2018). The degree to which residents are capable to (self-)organise and be actively involved in the process may be related to the size of the group, as often ‘small groups are more efficient and viable than large ones’ in taking collective action to achieve a common goal (Olson, Citation1965, p. 3). In addition, by undertaking various management tasks in the housing project, residents can lower service costs regarding maintenance, operation, and administration.

At the same time, the group may also hire other professionals due to the complexity of developing a CH project, thus potentially raising costs. These include project managers (Landenberger & Gütschow, Citation2019), facilitators (to moderate the meetings), and financial or legal advisors.

We, therefore, ask: How does this redefinition of roles affect the costs? And how does the group size influence self-organisation and residents’ participation?

3.5. Participation and decision-making

Manzini (Citation2016) distinguishes expert design (involving the professionals), diffuse design (involving the end-users), and co-design, which is the interaction between professionals and end-users. For Sanders and Stappers (Citation2008, p. 6), co-design refers ‘to the creativity of designers and people not trained in design working together in the design development process.’ In the context of co-production and existing partnerships in CH, Czischke (Citation2018, p. 8) defines a framework for a ‘continuum of user involvement’ in housing provision, ranging from residents’ consultation (lowest level) to the ‘entrepreneurial exit’ level (Gofen, Citation2012), where end-users take full initiative and responsibility in providing housing.

Considering these notions together with the seminal work developed by Arnstein (Citation1969), we define five levels of participation in the design phase (see ): non-participation (no collaboration, 100% expert-led), minor participation, medium participation, high participation (co-design), and full participation (no collaboration, 100% user-led). In cases with a high level of participation, collective decisions range from the overall spatial configuration to the finishing levels. In examples of medium or minor participation, residents are usually asked about their preferences and provide some guidelines, but final design decisions still belong to professionals. In this research, we discard the first and last levels, as all the selected case studies result from a collaboration between residents and professionals.

Table 1. Different levels of citizen/end-user participation (Source: Authors).

In CH, there are different non-hierarchical decision-making techniques, such as dynamic governance or sociocracy (Jarvis, Citation2015), consensus and voting (Jarvis, Citation2011; Ruiu, Citation2016; Williams, Citation2005). Consensus, considered the ideal decision-making technique by Landenberger and Gütschow (Citation2019), is applied in most cases. However, it demands a long time to reach a common agreement (Ruiu, Citation2016). Also, the participation of residents in the decision-making process might increase the level of conflict among residents (Jarvis, Citation2011; Williams, Citation2005), thus delaying the whole process.

Considering the above, we ask: How do the level of participation and decision-making techniques influence building costs?

3.6. Time

While time is a crucial factor when analysing building costs in general (Cunningham, Citation2013), in CH, it acquires an even more prominent position. CH is often characterised by its long initiation phase and decision-making processes (Ruiu, Citation2016) besides the active involvement of the residents’ group in in-kind tasks. Following the capitalist premise ‘time is money’, the amount of time the residents voluntarily dedicate to the project should be factored. This includes not only the carried-out tasks but also the time spent in reaching consensus in the meetings. However, CH is also based on other values, such as community building and internal solidarity (Sørvoll & Bengtsson, Citation2020), where time plays a pivotal role. Therefore, rather than simply translate time into ‘working hours’ to evaluate eventual costs or savings, it is relevant to raise the question ‘How do the involved participants perceive their devoted time and effort?’.

4. Identifying the design criteria influencing building costs in collaborative housing

4.1. Findings

This section describes the empirical findings from the 16 cases (summarized in ) according to the theoretically-derived design factors from our analytical framework. Product-related findings uncover the physical features of the cases, considering both the factors that influence building costs in general and those specific to CH projects (e.g. self-building, alternative layouts). Process-related findings are helpful to understand the impact of participation and self-organisation in the final ‘product’ and evaluate the effectiveness and organisation level of the design process.

Table 2. Summary of the findings applying the analytical framework, related to the 16 selected cases (Source: Authors).

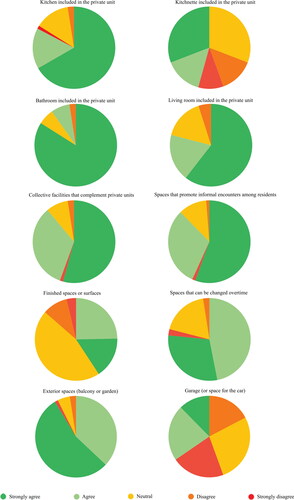

4.1.1. Minimum standards

The responses of the applied survey showed some patterns of what residents perceive as acceptable minimum standards (). While reducing the size of the private areas and the number of partition walls is commonly accepted, some functions within the private unit, such as living rooms and complete kitchens, are not willingly sacrificed. This puts into question the idea that residents in CH progressively reduce their privacy levels (Durret apud Jarvis, Citation2011). Large rooms and high-end materials/finishing are not valued as essential requirements; instead, high energy-efficient standards that increase comfort are considered more relevant.

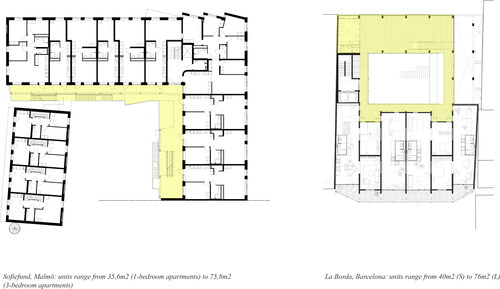

In most cases, this conception is translated into the design of their respective housing: certain collective design decisions include leaving some spaces unfinished (detected in 11 projects), minimizing the area of private units (in at least 8 projects), and reducing - or even excluding - some housing infrastructure (e.g. reduce the number of lifts or staircases in 2 projects, or forego/repurpose the car parking garage in 4 projects). For instance, in La Borda (Barcelona), private units range from 40 m2 (up to 2 residents) to 76 m2 (up to 4 residents); similarly, Sofielund (Malmö) accommodates units ranging from 35,6 m2 (1-bedroom units) to 75,8 m2 (3-bedroom units) (). All this suggests not only a lowering of the building costs but also a shift in the idea of quality or value in housing. As one resident said: ‘people’s expectations have changed, people accept different standards’ (personal communication, July 19, 2019). Nevertheless, outdated building norms tend to hamper this process of redefining standards; La Borda, Barcelona represents a ground-breaking example, as residents refused to build a car parking garage and negotiated the conditions to change the municipal legislation.

4.1.2. Housing typology

We have categorized the layout of the 16 projects into two different typologies: courtyard (organised around a shared courtyard), used in 7 projects, and block (compact rectangular building), applied in 9 projects. Both typologies are adequate for the highly-dense urban fabric in most cases due to their compactness. Accordingly, 11 projects are 5 to 7-storey high. This focus on simplicity and economies of scale help reduce building costs.

All projects combine private units with collective spaces. Laundries, communal kitchens, dining, living, and guestrooms are the most common collective spaces; and are mainly located on the ground floor (in 14 projects) and/or rooftop (in 10 projects). This allowed reducing the infrastructure and surface areas in the private units. These are generally standardised but flexible, with few partition walls (see ). While 9 projects use interior cores (staircase and elevator) as the primary circulation system, 5 adopt exterior galleries. Opening the project to the neighbourhood (neighbours may rent the collective spaces), detected in at least 7 projects, also translates into some economic benefits as ‘it creates some revenue for the group’ (resident, personal communication, July 1, 2018). This decision increases affordability or at least compensates for the eventual extra costs of building collective spaces.

In general, residents agree that there is a correct balance between private and collective spaces. In the cases where residents claimed that they do not save costs by living in their CH project (in comparison to market prices in the same area) they recognize the value of living with such extra facilities and the quality of comfort and convivial time. The following survey excerpts confirm: ‘we get a lot for it’, ‘it is worth all the money’ and ‘we have more benefits due to the much larger common areas’. This highlights the other (sometimes conflicting) values that drive the development of CH and the required trade-offs to accommodate them.

4.1.3. Construction approach

On the one hand, residents from 4 projects mentioned using low-quality materials to save costs. However, over time those materials had to be repaired or replaced. On the other hand, 12 projects adopted environmentally-friendly approaches, and half of the projects are described as having higher energy-efficiency standards than those legally defined. According to the residents, this represented a higher initial investment but compensated long-term by reducing the energy consumption and general maintenance costs. In all cases, there was an effort to define a standard structural scheme for the whole building to rationalise its construction, even in cases where private units are more flexible and customised (in 8 projects).

At least 11 projects are built through a phased construction, leaving some parts to be finished at a later stage, in a clear link with incremental housing approaches. The use of ‘self-building’ or DIY approaches can be seen in at least 9 projects. Examples include hands-on tasks such as finishing, painting, setting up the shared yard, and coordination and support tasks (e.g. cooking for self-builders). Some respondents do not believe that building costs are necessarily lower if self-building is carried out at an individual level; others think that, although time-consuming, self-building contributes to keeping costs under control by reducing the initial investment, saving on labour costs and collectively purchasing the materials. Moreover, according to one resident, the quality of ‘identification’ with the place or ‘sense of belonging’ increases with DIY approaches. However, if the decision to leave spaces unfinished upon moving is imposed in a top-down manner, the residents might not accept it (personal communication, July 19, 2019).

4.1.4. Organisational structure

The size of the resident groups varies significantly: 5 small-size (3–19 households), 7 medium-size (28–54 households) and 4 big-size (61–231 households). There is an apparent relationship between the level of participation and the group size: projects formed by small to medium groups indicate a higher involvement in the design process, while larger groups show a lower participation level. Accordingly, one architect stated that ‘50 to 80 adults have better group dynamics and work more efficiently’ (personal communication, June 14, 2019).

Overall, self-organisation, including in-kind tasks carried out by the residents, was mainly at a coordination/organisational level, namely the planning of meetings, setting up legal status for the group, research, formulation of rules, and at a construction level, as mentioned. 4/50 residents claim they did not include sufficient professional expertise during the process. Partial or total collective self-maintenance of the building (e.g. cleaning, repairing, gardening) was found in at least 12 projects; according to the residents’ testimonials, this resulted in lower costs since the group does the necessary tasks to avoid hiring personnel.

4.1.5. Participation and decision-making

The survey applied to the residents uncovered that participation in the design process was not a feature shared by all since 34/84 respondents joined the project at a later stage. Consequently, the apparent relationship between the size of the group and the level of participation is irrelevant if we ignore the exact number of participants in the design process. Therefore, when a project is ‘ranked’ with a certain level of participation, this may only apply to an initial core group, as sometimes not all residents participate in the design phase. This means that participation is assessed based on the ‘intensity’ of participation of those actively involved in the design phase rather than the number of participants. With this in mind and according to our categorisation system (see ), 10 projects are ranked as ‘high participation’, 4 as ‘medium participation’, and 2 as ‘minor participation’.

In at least 4 projects, ranked as ‘high participation’, the adopted design strategy was ‘from the common to the private’: first, residents and architects defined a common concept and the collective spaces; then – aware that many of the facilities were no longer necessary inside the private units – they decided the layout of the individual spaces. This highlights the collective in detriment of the individual and avoids redundant construction and unnecessary costs.

In at least 7 projects, residents decided to make use of ‘architecture working groups’, where a representative number of residents meet regularly (with and without the architects) to discuss design and construction matters. The use of consensus was detected in at least 9 projects, followed by consent in 3 projects. Interestingly, findings also show different perceptions about participation levels among residents of the same project. 12/50 respondents complained that ‘there were many conflicts among the group during decision-making’.

4.1.6. Time

Among the 16 cases, there is an average of 4–5 years from initiation to completion, being the formation of the group the longest stage. More than half of the survey respondents involved in the design claimed to have spent in total less than 50 hours in design meetings. When asked about the general difficulties encountered during the process, 13/50 respondents referred that ‘the process was too long’, 15/50 stated ‘no difficulties, the whole process ran smoothly’ and 16/50: ‘the design process was OK and the problem was more connected to financial or legal issues’.

Finally, findings also confirm the arguments pointed by existing literature on affordability and CH, namely the economic benefits of the collective activities (e.g. shared meals, collective maintenance) and legal-related issues (e.g. non-speculative ownership or leaseholds models). And although these are not necessarily specific to CH, their combination with the design factors may have an additional impact on the project’s affordability. They also provide insight on the (other) reasons that allowed these projects to be considered affordable, raising the question of the actual impact of the design-related ones.

4.2. Discussion

The proposed analytical framework applied to the 16 CH projects proved to be suitable for qualitatively exploring the influence of certain design factors in building costs. Cross-case patterns are most evident at the product level, from space and quality standards to the chosen typology features. Findings related to the process turned out to be subjective and non-consensual: perceptions about time, conflict level, or level of participation differ among participants in the same design process. Nevertheless, we detected some patterns, such as consensus as a decision-making technique, an average of 4–5 years’ process duration, and the type of in-kind tasks carried out by residents.

At the same time, we recognize the methodological challenge of analysing the perceptions of the involved participants in the design phase. They were useful to understand the nuances and the values that dominated the design process and provided factual information about the project that enriched the analysis of the final product. However, the residents’ perception does not entirely reflect the reality, as they may be unaware of the ‘damage’ of some decisions. For instance, none of the residents from La Borda mentioned the implications of not hiring one main contractor; however, the architects regret this decision since it meant extra coordination from their side and possibly some miscommunication during the building process. This and other examples, therefore, prevent us from formulating an accurate idea about the actual effectiveness of the process.

4.2.1. The building as a ‘product’ of a collective ‘process’

Findings related to product demonstrate that the CH cases share many features with more general forms of collective ‘affordable’ housing. Examples include smaller private units combined with collective spaces, the chosen housing typology, spatial flexibility, the choice for low-cost materials, and the general use of standardised and prefabricated construction. This last feature somehow contradicts the general assumption that custom-made layouts are typical features of CH. At least when affordability is at stake, residents agree on defining a standard structural scheme to streamline the construction and therefore keep costs down.

On the other hand, findings also uncover other factors – not usually present in conventional ‘affordable’ housing – that played a decisive role in reducing building costs. For instance, testimonials indicate that hands-on construction approaches may indeed contribute to increasing affordability, as long as they are organised collectively and the time spent is not considered a tiring burden. Findings also point to a redefinition of minimum quality standards, in a combination of factors that include a) the reduction of surface area and infrastructure in private spaces, b) accepting unfinished spaces or surfaces, c) questioning some building norms, and d) valuing concepts such as sustainability and high-energy efficiency. In this sense, groups determined what they would need in reality, often through a two-step process where they first decided about the common concept and then about each private space. All this resulted in needs-based layouts, avoiding duplication of functions or unused spaces.

These features are only possible due to a collaborative design process. Indeed, findings suggest that cases indicating a high level of resident participation correspond to outputs with more efficient use of space: the higher participation (when actual co-design takes place) detected in the small-medium groups is, in most cases, translated into a needs-based design, preserving the quality and the suitability to residents’ needs. The acceptance of smaller units, fewer facilities, and unfinished spaces or surfaces may also result from a high level of resident participation. This study also provides input on how the process itself was organised and carried out. We detected a general lack of consensus about the process setbacks, which is understandable, as we deal with many different personal perceptions. Still, we may derive some assumptions on how process-related factors incur additional costs or, on the contrary, reduce the overall costs. For instance, overall, the processes were not considered too long, with relatively low conflict levels. This goes against the general idea of the long and conflicted decision-making processes in CH and suggests a clear and structured design process. Self-organisation through in-kind work by the residents was said to save costs. However, excluding professional expertise may cause unexpected costs due to delays or building mistakes.

4.2.2. Trade-offs between costs and other values

In principle, additional collective spaces combined with high levels of privacy and higher energy efficiency standards would increase building costs. To avoid this, residents often compromised and showed a high tolerance to ‘lowering’ their standards in other aspects. Examples include the reduction or withdrawal of appliances or infrastructure, the incompletion of spaces upon moving in, and the overall reduction of private surface areas.

The use of low-quality materials was identified in some cases as another trade-off to allow some cost savings. However, this turned out to hamper affordability in the long term (due to the eventual repair or replacement). On the other hand, the increased initial investment to achieve higher energy efficiency standards is said to compensate in the long run, as they help reduce the monthly energy bills. This ‘new’ idea of minimum standards, valuing quality and the environment, increases building costs, but it also increases affordability in the long term. At the same time, it shows that the apparent conflict between environmental sustainability and affordability becomes less evident over time.

Moreover, to save costs, residents agree to carry out voluntary tasks. This is at the expense of their time and energy. However, quantifying the working hours is less relevant than assessing the actual residents’ perception of their spent time, considering that other values, such as community building and a sense of belonging, justify their dedication. This also relates to the needs-based design, where design approaches that tend to raise building costs are traded off with others to achieve an affordable compromise.

5. Conclusions

This paper underscores the role of architectural design and building costs as key components in the study of housing affordability. By conducting an international comparative case study encompassing 16 CH projects, we argued that collaborative design processes are likely to play an essential role in increasing affordability.

Based on the evidence presented in this paper, we conclude that strategic design decisions and self-organised activities aiming to reduce building costs indeed increase the affordability of the project. These decisions highlight the trade-offs between lowering costs and preserving (or improving) quality in housing, as well as the relevance of the residents’ participation in the design process since they are the ones who have to set the conditions for these trade-offs. These compromises also show that, in CH, the issue of affordability never comes alone: environmental sustainability and community building are other core values in CH, which may clash with each other.

We have identified several design criteria used in CH to increase affordability, namely: a) the adoption of a ‘common concept’ and use of standardised construction; b) the often-applied needs-based approach, where space is designed according to the residents’ actual needs and demands, which is based on c) the redefinition of minimum housing standards by the residents themselves (e.g. accepting smaller, less-equipped and unfinished private units if combined with collective spaces, and valuing environmentally-friendly and high energy-efficiency standards to improve thermal comfort and long-term savings). Our analysis also shows that some design decisions in CH increase affordability even when it results in higher building costs. From a process perspective, some factors that we found influencing collective decisions and positively impacting the affordability of the project are: a) the high level of participation in the design phase; b) the allocation of specific in-kind tasks, together with c) strategic (un)involvement of professionals; and d) structured and time-efficient process. These can avoid time-consuming conflicts, streamline decision-making processes and save on labour and managerial costs.

In sum, while some findings contradict general assumptions associated with CH (e.g. highly customised layouts, low levels of privacy), others uncover the economic benefits of co-design and self-organisation (needs-based design, redefinition of minimum standards, in-kind tasks). By considering product and process as inseparable dimensions of a whole, we demonstrated that building costs are dependent not only on the final physical outcome but also on the way the design process is collectively organised and managed.

This initial study sheds light on how design matters for affordability in CH and can inform and benefit residents’ groups, architects working in CH projects, and other relevant stakeholders. It may complement existing research on more general factors impacting affordability, such as tenure models, land acquisition, and funding mechanisms. Moreover, the proposed analytical framework can assist more quantitative studies linking building costs and collaborative housing. Future research can further explore the existing correlations between perceptions on minimum standards and the actual built form of CH and deepen the understanding of the role of the co-design process in reducing building costs.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a preliminary study presented at the International Conference European Network for Housing Research (ENHR): ‘Housing For The Next European Social Model’ in Athens, Greece, 27–30 August 2019. The research has been possible thanks to the financial support of the Portuguese foundation ‘Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia’ (FCT). The authors would like to thank all the residents who completed the survey and the residents and other professionals who made themselves available to be interviewed and guide the project visits. In addition, the authors are very thankful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aernouts, N. & Ryckewaert, M. (2017) Beyond housing: On the role of commoning in the establishment of a community land trust project, International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(4), pp. 503–521.

- Aravena, A. & Iacobelli, A. (2012) Elemental: manual de vivienda incremental y diseno participativo [Elemental: Incremental Housing Manual and Participatory Design] (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz).

- Archer, T. (2020) The mechanics of housing collectivism: How forms and functions affect affordability, Housing Studies, pp. 1–30. DOI: 10.1080/02673037.2020.1803798

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969) A ladder of citizen participation, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35, pp. 216–224.

- Belniak, S., Leśniak, A., Plebankiewicz, E. & Zima, K. (2013) The influence of the building shape on the costs of its construction, Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, 18, pp. 90–102.

- Brysch, S. (2018) Designing and building housing together: The Spanish case of La Borda. Paper presented at the Collaborative Housing workshop at European Network of Housing Research conference, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Brysch, S. (2019) Reinterpreting existenzminimum in contemporary affordable housing solutions, Urban Planning, 4, pp. 326–345.

- Cabré, E. & Andrés, A. (2017) La Borda: A case study on the implementation of cooperative housing in Catalonia, International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(3), pp. 1–21.

- Chatterton, P. (2013) Towards an agenda for post-carbon cities: Lessons from Lilac, the UK’s first ecological, affordable cohousing community, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37, pp. 1654–1674.

- Chau, K.-W., Wong, S.K., Yau, Y. & Yeung, A. (2007) Determining optimal building height, Urban Studies, 44, pp. 591–607.

- Cunningham, T. (2013) Factors affecting the cost of building work-an overview.

- Czischke, D. (2018) Collaborative housing and housing providers: Towards an analytical framework of multi-stakeholder collaboration in housing co-production, International Journal of Housing Policy, 18, pp. 55–81.

- Czischke, D., Carriou, C. & Lang, R. (2020) Collaborative housing in Europe: Conceptualizing the field, Housing, Theory and Society, 37(1), pp. 1–9.

- Czischke, D. & van Bortel, G. (2018) An exploration of concepts and polices on ‘Affordable Housing’in England, Italy, Poland and The Netherlands, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, pp. 1–21. DOI: 10.1007/s10901-018-9598-1.

- De Paris, S.R. & Lopes, C.N.L. (2018) Housing flexibility problem: Review of recent limitations and solutions, Frontiers of Architectural Research, 7, pp. 80–91.

- Duncan, S. & Rowe, A. (1993) Self-provided housing: The first world’s hidden housing arm, Urban Studies, 30, pp. 1331–1354.

- Engelsman, U., Rowe, M. & Southern, A. (2018) Community land trusts, affordable housing and community organising in low-income neighbourhoods, International Journal of Housing Policy, 18, pp. 103–123.

- Fromm, D. (1991) Collaborative communities: Cohousing, central living, and other new forms of housing with shared facilities. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Fromm, D. (2012) Seeding community: Collaborative housing as a strategy for social and neighbourhood repair, Built Environment, 38, pp. 364–394.

- Gofen, A. (2012) Entrepreneurial exit response to dissatisfaction with public services, Public Administration, 90, pp. 1088–1106.

- Habraken, J. & Teicher, J. (1972) Supports: An Alternative to Mass Housing (London: Architectural Press).

- Haffner, M. & Heylen, K. (2011) User costs and housing expenses. Towards a more comprehensive approach to affordability, Housing Studies, 26, pp. 593–614.

- Hellgardt, M. (1987) Martin Wagner: The work of building in the era of its technical reproduction, Construction History, 3, pp. 95–114.

- Jarvis, H. (2011) Saving space, sharing time: Integrated infrastructures of daily life in cohousing, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 43, pp. 560–577.

- Jarvis, H. (2015) Towards a deeper understanding of the social architecture of co-housing: Evidence from the UK, USA and Australia, Urban Research & Practice, 8, pp. 93–105.

- Landenberger, L. & Gütschow, M. (2019) Project management for building groups: Lessons from Baugemeinschaft Practice, Built Environment, 45, pp. 296–307.

- Lang, R., Carriou, C. & Czischke, D. (2019) Collaborative housing research (1990–2017): A systematic review and thematic analysis of the field, Housing, Theory and Society, 37(1), pp. 10–39.

- Maclennan, D. & Williams, R. (1990) Affordable housing in Britain and the United States (York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation).

- Manzini, E. (2016) Design culture and dialogic design, Design Issues, 32, pp. 52–59.

- Mulliner, E., Smallbone, K. & Maliene, V. (2013) An assessment of sustainable housing affordability using a multiple criteria decision making method, Omega, 41, pp. 270–279.

- Olson, M. (1965) The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

- Palmer, J. (2019) Without the developer, who develops?’ Collaborative self-development experiences in Australian Cities, Built Environment, 45, pp. 308–331.

- Paterson, E. & Dunn, M. (2009) Perspectives on utilising community land trusts as a vehicle for affordable housing provision, Local Environment, 14, pp. 749–764.

- Pittini, A., Koessl, G., Dijol, J., Lakatos, E. & Ghekiere, L. (2017) The State of Housing in the EU. Retrieved from www.housingeurope.eu

- Ruby, A. & Ruby, I. (2011) Min to Max: International Architecture Symposium on the Redefinition of the “minimal subsistence dwelling”. Available at http://www.min2max.org/ (accessed 11 July 2019).

- Ruiu, M. (2016) Participatory processes in designing cohousing communities: The case of the community project, Housing and Society, 43, pp. 168–181.

- Sanders, E. B.-N. & Stappers, P. J. (2008) Co-creation and the new landscapes of design, Co-design, 4, pp. 5–18.

- Sandstedt, E. & Westin, S. (2015) Beyond Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. Cohousing life in contemporary Sweden, Housing, Theory and Society, 32, pp. 131–150.

- Sanoff, H. (2010) Democratic design: Participation case studies in urban and small town environments. Available at https://www.academia.edu/8154922/Democratic_Design_Participation_case_Studies_in_Urban_and_Small_Town_Environments. (accessed 12 December 2019).

- Seeley, I. H. (1983) Cost implications of design variables, in: Building Economics, pp. 18–37 (London: Springer).

- Slaughter, E. S. (2001) Design strategies to increase building flexibility, Building Research & Information, 29, pp. 208–217.

- Sørvoll, J. & Bengtsson, B. (2020) Mechanisms of solidarity in collaborative housing–the case of co-operative housing in Denmark 1980–2017, Housing, Theory and Society, 37, pp. 65–81.

- Tummers, L. (2016) The re-emergence of self-managed co-housing in Europe- a critical review of co-housing research, Urban Studies, 53, pp. 2023–2040.

- Turner, J. F. (1972) Housing as a verb, in: J. F. C. Turner & R. Fichter (Eds) Freedom to Build, pp. 148–175 (New York: Macmillan).

- van Bortel, G. & Gruis, V. (2019) Innovative arrangements between public and private actors in affordable housing provision: Examples from Austria, England and Italy, Urban Science, 3, pp. 52.

- Vestbro, D. U. (2008) History of Cohousing - internationally and in Sweden.

- Vestbro, D. U. (2010) Living together-cohousing ideas and realities around the world: proceedings from the International Collaborative Housing Conference in Stockholm 5–9 May 2010: Division of Urban and Regional Studies, Royal Institute of Technology in collaboration with Kollektivhus NU.

- Wetzstein, S. (2017) The global urban housing affordability crisis, Urban Studies, 54, pp. 3159–3177.

- Williams, J. (2005) Designing neighbourhoods for social interaction: The case of cohousing, Journal of Urban Design, 10, pp. 195–227.

- Woetzel, J. R. (2014) A blueprint for addressing the global affordable housing challenge. Executive Summary (McKinsey Global Institute). Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/∼/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/urbanization/tackling%20the%20worlds%20affordable%20housing%20challenge/mgi_affordable_housing_executive%20summary_october%202014.ashx