Abstract

Comparative housing studies traditionally focus on housing systems and social or economic policy, only rarely considering design issues. Through an examination of subsidized housing and its design in 20 countries, this paper explores how design research can benefit cross-national housing studies. Subsidized housing is essential to delivering decent and affordable homes, underpinning the right to housing. To relate design dimensions to housing systems, the analytical focus is on regulatory instruments, technical standards, and socio-spatial practices as well as housing providers, tenures, and target groups. Design research benefits the contextualization of housing systems and design outcomes in several ways. It reveals the contextual and contingent nature of regulatory cultures and instruments, socio-technical norms and standards, and socio-cultural expectations and practices that shape housing solutions. The paper concludes by considering productive ways architectural design research might contribute to an interdisciplinary housing research agenda by offering new means of theorization and analysis beyond traditional housing system typologies.

Introduction: subsidized housing, design research, and comparative perspectives

This paper proposes an interdisciplinary research agenda with an architectural design-focused analytical framework to capture contextual differences in cross-national subsidized housing comparisons and to overcome problems of transferability in housing systems analysis. It compares standard subsidized housing design controls and design outcomes in relation to analytical categories used in comparative housing studies. The discussion explores possible intersections between architectural design research and comparative housing studies.

'Subsidized housing' is a term used to refer to a diversity of public and private sector housing that is 1) financially supported by a subsidy, 2) rented or sold below market rates, and 3) allocated based on social welfare and political criteria. It also tends to be built at scale using standardized designs. Subsidized housing includes widely accessible 'public housing', which is a large sector in places like Hong Kong (46%) and Singapore (81%), while in Europe it is predominantly associated with post-war social welfare policies and state-led mass-housing programmes. It also includes special-access 'social housing' that emerged with the exclusion of vulnerable and low-income groups or those with special housing needs from the new housing markets created since the 1980s (Hansson & Lundgren, Citation2019; Levy-Vroelant, Citation2010; Palm & Whitzman, Citation2019; Parsell et al., Citation2019). It further relates to the more recent term 'affordable housing', which recognizes extensive housing marketization and challenges of affordability (Stone, Citation2006) and has required mitigating state intervention through subsidies (Crook & Whitehead, Citation2019; Friedman & Rosen, Citation2020; Galster & Lee, Citation2021; Preece et al., Citation2019).

Functioning across distinctions between private- and public-sector housing provision, subsidized housing plays an essential role in all housing markets in the delivery of 'adequate, safe, and affordable housing', an essential objective to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goal 11 on sustainable cities and communities. With housing widely understood as a fundamental right, especially subsidized housing is a key social welfare provision underpinning this right. It is an important driver of social change and mobility, economic growth (Wardrip et al., Citation2011), and urban development (Hu & Wang, Citation2019). Subsidized housing brings together social, economic, and political agendas, and its standardized form spatializes shared socio-cultural norms related to common lifestyles, habits, home use, and housing expectations (Ravetz, Citation2001).

While issues of affordability and access dominate discussions of subsidized housing, analyzing its design is critical to assessing whether it is adequate and safe – or according to the UK government 'decent' and compliant with minimum design standards (Department for Communities and Local Government, Citation2006). Covid-19 and the climate crisis have revealed significant shortcomings in housing design, with the pandemic exacerbating inequalities around dwelling size, usability, and location (Buffel et al., Citation2021; Preece et al., Citation2021; Sun et al., Citation2021). This calls into question if current environmental, spatial, and functional requirements are sufficient. Studies of housing design and control are thus instrumental to understanding problems in housing delivery, usability, and maintenance at the dwelling scale.

Many countries use standardized design solutions, mandatory design requirements, and voluntary good practice guides to control housing design (Gallent et al., Citation2010). Design regulations include technical housing standards to control the provision of space and amenities, overcrowding, functionality and usability, health and safety, structural and material performance, environmental comfort, and maintenance, which are all essential aspects of decent housing provision. While technical standards might be based on universal principles, many also relate to contextual and historical housing problems as well as socio-cultural expectations.

The central role of design and regulatory controls – mandatory requirements (regulations) and voluntary good practice (standards) – in determining subsidized housing outcomes is largely overlooked by academics, as is the potential of studying regulations and standards for more detailed and contextual cross-national housing comparisons. There is limited discussion in housing studies on how housing systems and policy approaches inform design regulations, standards, dwelling size, and housing quality (Hoekstra, Citation2005; Kemeny, Citation1991). Equally, despite a focus on housing design, architectural and planning studies rarely engage with wider policy contexts and housing system characteristics that determine how homes are procured (Branco Pedro, Citation2009; Foster et al., Citation2020; Ishak et al., Citation2016; Madeddu et al., Citation2015; Rowlands et al., Citation2009; Roy & Roy, Citation2016; Tervo & Hirvonen, Citation2019). The value of exploring the connections between standard housing solutions and housing systems, policy, and regulations remain a significantly understudied interdisciplinary problem in design research and housing studies.

Comparative housing studies

Harking back to the welfare typologies first proposed by Esping-Andersen (Citation1990) and applied to housing by Kemeny (Citation1995), traditional Western housing system typologies are defined in relation to social welfare typologies, with the expectation that they have distinct differences in housing procurement and tenure. The two established main typologies are 'dualist' or 'integrated' (unitary) rental systems, characterized by different governance approaches and relationships between subsidized and market housing (Kemeny, Citation1995). Theoretically, integrated rental systems produce higher housing quality standards through forced competition between private and public providers.

A fundamental criticism of using welfare typologies in housing studies is that assumed correlations between housing and welfare systems are weak due to the specificity of housing among other social welfare benefits such as healthcare and education (Kemeny, Citation2001; Malpass, Citation2008). The widespread deregulation and financialization of housing in Europe have further weakened this link or made it obsolete (Blessing, Citation2012, Citation2016; Schwartz & Seabrooke, Citation2008; Stephens, Citation2020). In addition, a growing number of comparative housing studies focusing on post-communist (Chen et al., Citation2013; Hegedus et al., Citation2013; Tsenkova, Citation2009; Wang & Murie, Citation2011) or East Asian (Doling & Ronald, Citation2014; Forrest & Lee, Citation2003; Lee, Citation2003; Renaud et al., Citation2016) and Latin American (Molina et al., Citation2019; Murray & Clapham, Citation2015; Neto & Arreortua, Citation2019) regions suggest that typologies developed in the twentieth century in a Western welfare-state context are not transferable to emerging markets or transitioning housing systems, thus necessitating more region-specific methodologies.

Traditional comparative housing studies rely on quantitative and descriptive measures such as tenure composition, subsidies, and housing supply and outcomes in their analysis. However, this approach is questioned by calls for more nuanced, theoretically grounded, and qualitative studies of housing systems (Haworth et al., Citation2004; Stephens & Norris, Citation2014). Already Kemeny & Lowe (Citation1998) highlighted the need for cultural, ideological, and political perspectives to better understand differences in housing systems. Some recent studies particularly emphasize the dependence of current housing policy on past policy decisions, proposing a historically grounded analysis based on dynamic classifications (Bengtsson & Ruonavaara, Citation2011; Blackwell & Bengtsson, Citation2021; Blackwell & Kohl, Citation2019; Suttor, Citation2011). Others have proposed qualitative perspectives (Haworth et al., Citation2004) or adopted methods from other disciplines (Ronald, Citation2011), such as discourse analysis (Hastings, Citation2000) and ethnographic studies (Wetzstein, Citation2019), but note the difficulty of conducting fieldwork necessary to achieve nuanced comparison. Acknowledging the need for new approaches, this paper explores a contextual reading of housing systems through the analysis of design controls, regulations, and outcomes, and their value for more granular comparative housing studies.

Housing design and controls from a comparative perspective

Design controls are shaped by knowledge of, or assumptions on, household compositions, daily routines, user needs, and wider social and cultural expectations that determine what housing is deemed adequate. Thus, existing housing conventions or norms and procurement preferences are reinforced by the housing that gets built. Housing outcomes, especially in the subsidized sector, are sensitive to two related drivers: 1) socio-cultural housing expectations or norms and 2) political and economic contexts. However, these are often studied in isolation.

An extensive body of literature from architectural humanities discusses how housing forms are shaped by socio-cultural factors (e.g. Lawrence, Citation1983; Murphy, Citation2015; Rapoport, Citation2000). Accordingly, Lawrence (Citation1981) in a comparison of Australian and English dwelling layouts discusses how they are directly informed by culturally encoded domestic practices. Comparing the UK and Japan, Ozaki (Citation2002) similarly finds that cultures of privacy have a strong impact on common house forms. Studying 'regulatory regimes' of housing design in the European Union, Karn & Nystrom (Citation1998) likewise argue for the non-transferability of design controls between countries on the grounds of cultural specificity.

Socio-cultural factors are closely linked to housing systems and policies. Gallent et al. (Citation2010) in their study of space standards in Italy and England observe that the creation and implementation of space standards are path-dependent and contingent on political, planning, and market contexts. Susanto et al. (Citation2020), Roy & Roy (Citation2016), and Sendi (Citation2013) argue that socio-cultural, political, and economic factors are inseparable from how housing standards are determined in Indonesia, India, and Slovenia respectively. Appolloni & D'Alessandro (Citation2021) even propose a classification based on the formulation of space standards: market-oriented (England and Wales), prescriptive (Italy), and functionality-oriented (Netherlands). Branco Pedro & Boueri (Citation2011), when comparing space standards for subsidized housing in Portugal and São Paulo, explain differences through contextual factors such as housing deficit, income, policy aims, and subsidized housing systems including tenure and target group. Hoekstra (Citation2005) further argues for a correlation between housing type preferences and welfare typologies. How standards and housing quality are determined thus greatly varies between countries (McNelis, Citation2016). This emphasizes the extent to which specific historical events, culturally determined expectations of the home, its use, household composition, regulatory cultures, and economic developments determine local housing solutions. It gives importance to housing design and regulations when comparing differences or similarities between subsidized housing systems and design outcomes.

In support of practice- and design-based studies of housing systems, this paper proposes an interdisciplinary research agenda that connects architectural design research, housing studies, and policy studies and contributes to mainstream comparative housing systems literature. It suggests subsidized housing outcomes and the regulation of design as an important area of research defined by both socio-cultural housing norms and political and economic contexts. This is explored through two linked questions:

How can design research enhance the theorization and improve the contextualization of subsidized housing studies to advance a comparative research agenda?

What is the added analytical and methodological value of incorporating housing design research into comparative studies of housing systems?

Studying these cross-disciplinary questions, a tentative research agenda for a cross-national comparison of subsidized housing systems and practices is proposed. This is developed through a discussion of how regulatory instruments, technical standards, and socio-spatial reasoning can promote greater contextual analysis and a greater emphasis of the social aims and determinants of subsidized housing.

Methods

While much research, especially since the 1980s, has focused on European and Western housing systems – often employing an empiricist 'juxtapositional analysis' or generalizing 'convergence' perspective – there is a growing call for 'divergence', 'middle range', and non-European perspectives to highlight contextual differences (Hoekstra, Citation2010; Kemeny & Lowe, Citation1998; Wang & Murie, Citation2011). The value of comparing housing systems through the proposed architectural design research lens (Fraser, Citation2013; Luck, Citation2019) – practice-led research focused on architectural design practice and thinking – lies in its potential to improve contextual readings of how subsidized housing is conceptualized and analyzed. It also serves to strengthen underrepresented architectural research practices in housing studies. The proposed cross-disciplinary methodology integrates traditional categories of housing analysis such as tenure, provider, and target group found in studies of housing systems (Hansson & Lundgren, Citation2019; Kemeny, Citation2001; Scanlon et al., Citation2014) with that of design controls and drivers more common to architectural design research. Housing regulations are, for example, related to issues of housing tenure, providers, and target groups, as they are based on generalizable and normative notions of housing, which are translated into functional requirements specific to particular housing systems, sectors, and standards (Hoekstra, Citation2005). Studies of housing design and its regulation through technical standards can thus present tangible evidence of differences between housing systems.

Technical standards are enforced through regulatory instruments – of which the analyzed space standards and building regulations are typical examples – to ensure basic housing usability and quality. This is conventionally assessed in design terms through the analysis of dwelling plans. The study of subsidized housing benefits from the sector having more onerous regulations to safeguard minimum housing standards, whereas other sectors might be deregulated and thus difficult to compare in this respect. While there is a large range of housing design regulations, this tentative study is limited to the analysis of space standards and their effect on typical housing layouts.

The paper is based on a broad international scan of housing systems, design controls, and exemplary housing plans in 20 countries, following a three-stage review and selection process.

First, to capture the variety of existing housing systems, a review of literature on subsidized housing was conducted. Using the keywords 'affordability', 'social housing', and 'public housing', the Scopus, Web of Science, and British Library databases were searched for literature on housing studies. This included international housing reports and comparative studies. While there was much information on Europe, North America, Australia, East Asia, and Latin America, little could be found for Africa, Central and South Asia, and the Middle East (with notable exceptions of Bredenoord et al., Citation2014; Mafico, Citation1991; Roy & Roy, Citation2016; Towry-Coker, Citation2012), limiting their inclusion in the review. The keyword search returned sufficient records for 35 countries, with 116 records reviewed in detail to classify housing models in each country according to main tenure, provider, and target groups – categories commonly found in comparative housing studies (Hansson & Lundgren, Citation2019; Kemeny, Citation2001; Scanlon et al., Citation2014).

Second, for each of the 35 countries, a search for housing policy on national and regional government websites was undertaken, which included the collection of building regulations, codes, and standards applicable to subsidized housing (). The scope was limited to design controls determining the interior dwelling layout and size. Although many countries have additional guidelines for the design of neighbourhoods, estates, and housing blocks that can affect internal housing layouts, these were not considered. For countries such as Colombia, Brazil, and China, major housing programmes like Minha Casa Minha Vida were included in the study as representing the main source of subsidized housing supply. In countries with federal states and varying housing providers and regulations, such as Australia, Austria, Canada, Switzerland, and the United States, only selected regional regulations were reviewed. For Hong Kong and Singapore, the design controls used by housing agencies who are the main subsidized housing providers were analyzed.

Third, typical dwelling plans were collected for the 35 countries from large subsidized housing developments by searching the online databases of major providers in every country. For comparability, this was limited to two-bedroom dwellings, the most common unit size found across all analyzed countries ().

From the initial list, only countries with clearly defined housing provision systems and complete online data on design controls and standard dwelling plans were selected, resulting in a revised list of 20 countries for a detailed comparison, including a review of 52 articles. While this sample does not fully capture all possible housing systems, design controls, and context variations, it was deemed sufficient for a study not intended to generalize. For this final list, links between housing design and housing systems were analyzed by iteratively comparing design controls to typical housing designs and the three attributes of provider, tenure, and target group to assess the extent of their correlation with different housing systems (). In addition, national classifications of housing systems and design outcomes were compared to those found in literature not specific to the analyzed 20 countries to further contextualize observed repetitions and differences. This clarified the extent to which housing designs reflect contextual factors and local dimensions

Table 1. Subsidized housing systems in 20 countries.

Tentative framing of comparative subsidized housing studies through design research

In the following, the benefits of architectural design research to comparative studies of subsidized housing systems are discussed in relation to three interrelated empirical categories and analytical frameworks offered by it: regulatory instruments, technical standards, and socio-spatial reasoning or practices. Based on this, possible benefits to a comparative housing research agenda that emerge from each design research aspect are proposed.

Regulatory instruments

Differentiated and universal design controls

In the countries surveyed, mandatory controls are used to regulate the design of new dwellings except in South Korea and Poland.Footnote1 Two distinct approaches to the control of subsidized housing relative to other sectors are observed that reflect on regulatory cultures. First, countries with 'differentiated' design controls that have separate or additional requirements for subsidized housing (Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, England, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Scotland, and Singapore) and second, countries with 'universal' design controls that equally apply to all housing sectors (Austria, Finland, France, Ireland, and Sweden).

Although no common target group, form of tenure, or provider characterizes countries with differentiated or universal controls, in Western countries, differentiated design controls correspond to dualist rental systems and universal controls to integrated rental systems as defined by Kemeny (Citation1995). In integrated rental systems, subsidized housing is widely accessible, not only to vulnerable or disadvantaged households. Countries such as Austria, Finland, France, and Sweden, which have the lowest homeownership rates in Europe (Housing Europe, Citation2017), use universal design controls that are meant to result in fewer differences between private and social housing design. In dualist rental systems such as Australia, Canada, England, the Netherlands, and Scotland, which have high owner-occupancy rates, differentiated design controls are observed and greater differences between private and social housing are expected.

In dualist countries, subsidized housing functions as a 'safety net' (Boelhouwer, Citation2019; Lau & Murie, Citation2017; Stephens, Citation2019). State intervention is limited, often to the support of vulnerable and disadvantaged groups, in an attempt to balance adequate housing standards against minimum levels of disposable income (Blessing, Citation2016). Vulnerability and disadvantage – apart from income, disability, or health risks criteria – are commonly defined in spatial and design terms such as overcrowding or fitness of dwellings for occupation and assessed against housing and space standards (Levy-Vroelant, Citation2010).

In non-Western countries where traditional rental and housing system typologies do not apply, universal design controls are rare. Often reliant on direct government involvement, instead differentiated controls are frequently the result of developmental challenges related to urban planning, social welfare provision, or construction sector-based economic growth. For example, in China and Singapore, state intervention in the housing market is particularly high, coinciding with structural changes in the relationship between welfare and subsidized housing systems (Chen et al., Citation2014; Chua, Citation2014; Ronald & Doling, Citation2010). In Colombia and Brazil, subsidized housing programmes support homeownership for the most disadvantaged communities and play a key role in economic growth (Murray & Clapham, Citation2015; Neto & Arreortua, Citation2019; Sengupta, Citation2019). Due to the typical large scale of subsidized housing developments as part of government-led national and regional development efforts, an economy in construction is achieved through the repetition of standard block and dwelling plans.

Benefit to comparative housing research: design control approaches offer a means of comparison beyond the limitation of traditional housing system typologies

The study of regulatory instruments reveals evident relationships between how subsidized housing is conceptualized, provided, and its design regulated. The comparison of approaches to subsidized housing design control provides an added analytical and explanatory framework complementing traditional housing system typologies but also overcomes their limitation when studying emerging markets and transitioning housing systems. It offers a wider range of possible comparisons between countries and regions by taking into account social, political, and economic histories or transformations that are otherwise not captured by housing systems based on Western welfare-state models. In particular, it reflects the regulatory culture and role of subsidized housing in a housing market at specific moments in time.

Contextualization of universal regulatory principles

The design of subsidized housing is controlled by three types of regulatory instruments: 1) standards for dwelling sizes, 2) functional requirements such as room sizes, dimensions, and furniture schedules, and 3) standard unit or block plans (). Design controls most commonly include standards for dwelling sizes in combination with either i) additional functional requirements or ii) standard unit plans. Despite following universal principles – as different regulatory instruments might be used in the same country when housing markets change – the way regulatory instruments are combined and specified differs between countries and periods. Thus, regulatory instruments relate to housing market conditions and supply in a specific place and point in time. For example, in England subsidized housing was in the nineteenth century based on so-called philanthropic 'model dwellings' and their standardized plans but in the early twentieth century space standards were introduced that could be applied to different layouts and providers.

Table 2. Comparison of housing design control documents and standards.

In most cases, dwelling size standards are given as minima and combined with functional requirements (). Canada, Australia, and Switzerland determine dwelling size standards according to the number of bedrooms, while in England, Scotland, and Ireland they are based on the number of occupants in a dwelling – with their age and sex serving as criteria for assessing overcrowding and housing allocation. Additional design controls often include minimum bedroom widths and room floor areas.

Countries with large, subsidized housing programmes, including Colombia, Brazil, and Singapore, combine target dwelling sizes with functional criteria (). Often dependent on large private-sector supply, this approach gives greater design flexibility to providers to keep construction costs and subsidies lower. Another example is England, where various providers supply subsidized housing, including housing associations, cooperatives, and local authorities. But functional assessment criteria are very diverse. While Colombia requires a minimum of two bedrooms and widths of 2.7 m, Brazil's housing programme provides a furniture schedule with standard dimensions that each relevant room type must be able to accommodate. In England, where space standards are not consistently adopted, one way of showing compliance with minimum dwelling-size requirements is to demonstrate that a floor plan can fit all required furniture.

Design controls typically specify the amenities and minimum kitchen and bathroom equipment or storage areas in dwellings. Some standards might extend to even specifying materials, finishes, and fixtures, especially for kitchens and bathrooms. In countries, in which the main tenure type is rental, such as Scotland, China, Australia, and Canada, material specifications are based on long-term maintenance criteria.

Dimensional standards are also increasingly determined by accessibility requirements and universal design principles (Milner & Madigan, Citation2004). For instance, the Swedish Standards (Swedish Standards Institute, Citation2006), London Housing Design Guide (Mayor of London, Citation2010), Glasgow Standard (Housing and Regeneration Services, Citation2018) or Queensland Social Housing Design Guidelines (Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy, Citation2017) include minimum accessibility standards, as subsidized housing in these countries prioritizes disabled tenants and the needs of an ageing population.

Finally, subsidized housing programmes in China and Hong Kong use standardized plans. Key housing pilot schemes in Beijing and Shanghai develop standard unit plans for guidance alongside target dwelling sizes (). Hong Kong uses standard unit and block plans, with their design determined by housing needs (dwelling mix and size), site constraints, and, increasingly, modular methods of construction. The Hong Kong Housing Authority has updated its standard block plans almost every decade since the 1950s, with dwelling sizes and amenities improving (Sullivan, Citation2016). Fully repeated standard unit or block plans are indicative of extensive state-led subsidized housing provision, with limited need for formal design regulations.

Benefit to comparative housing research: regulatory instruments in the control of subsidized housing design reflect universal principles but are contextual in their definition

The comparison shows that regulatory instruments – their definition, implementation, and combination – directly relate to national regulatory cultures, procurement models, and housing markets. Therefore, the study of design controls enriches and complements that of housing systems by providing an analytical framework that can integrate a wide range of contextual factors.

Technical standards

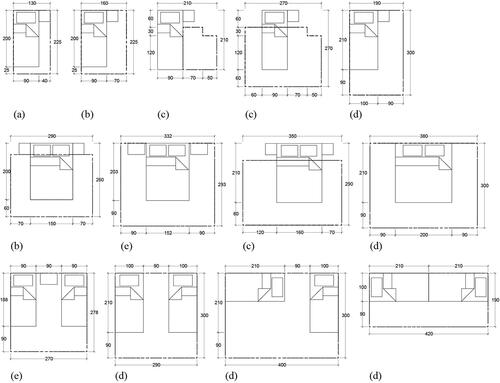

Housing design outcomes are greatly determined by technical standards. Comparing typical dwelling sizes as prescribed by common design controls, 'standards' remarkably differ (). In Hong Kong, the standard unit size for a two-person dwelling is 14–22 m2, in France 28 m2, in Canada 49 m2, and in Australia 55–65 m2. This translates into significant differences in the space available per person, which impacts on dwelling usability and flexibility. Likewise, room standards and required activity zones significantly vary, indicating different furniture standards and cultural expectations or practices of use, which is especially legible in minimum bedroom sizes (). For example, the minimum size of a double bedroom ranges from 9 m2 in France to 12 m2 in Scotland. In Australia, the Queensland Social Housing Design Guide (2017) requires a minimum 90 cm wide movement area next to a bed, the London Housing Design Guide (2010) only 40 cm. These differences in basic design requirements are only partially explained by housing provider, tenure, or target group – especially in countries with universal design controls – but point to economic pressures such as land and development costs and socio-cultural norms that determine them.

Figure 1. Space standards and activity zones for bedrooms. Bedrooms are the most standardized and regulated parts of a home in terms of their size and dimensions. Dashed lines indicate the required movement area around the bed. Differences in size and organization indicate different standard bed sizes, bedroom uses, and users, which have become established as normative socio-spatial practices. Source: Redrawn by authors based on: (a) Building (Scotland) Regulations, Building Standards Technical Handbook: Domestic Buildings (Local Government and Communities Directorate, Citation2017); (b) The Glasgow Standard (Housing and Regeneration Services, Citation2018); (c) Swedish Standards (Swedish Standards Institute, Citation2006); (d) WBS Housing Assessment System (Bundesamt für Wohnungswesen, Citation2015); (e) Queensland Social Housing Design Guide (Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy, Citation2017).

Dwelling and room size standards tend to correspond to socially defined space standards (Susanto et al., Citation2020). While presented in quantifiable terms, dwelling usability is shaped by social norms such as the nuclear and working family and its socio-spatial hierarchies and gendered spatial divides. Based on normative ideas on households and daily routines, space standards derive from the dimensions of standard furniture layouts and the activity zones and access spaces needed to use a home. In the UK, space standards still echo research conducted in the second half of the twentieth century, such as the series of Design Bulletins published by the Ministry of Housing and Local Government from 1962 to 1970 based on joint research by architects and sociologists.

Dwelling layouts are arguably a direct translation of design controls. Both give insights into the socio-spatial reasoning behind space standards and assumptions on dwelling use, which determines how rooms are organized and related. While in some countries layouts are highly standardized through the use of prescriptive standard plans and functional criteria, countries that only specify dwelling size and/or dimensional and functional criteria encourage greater design variation.

In Singapore, public housing is reserved for families and thus designed for a typical lifecycle of a nuclear family. Dwellings cater for traditional familial living patterns by providing a master bedroom and en-suite as well as open-plan living areas with an easily separable kitchen. In Colombia, where subsidized housing is for ownership, a planning requirement stipulates that new-built family dwellings must be capable of accommodating the later creation of at least one additional bed space within the existing dwelling envelope. This emphasizes long-term usability and recognizes changes in housing needs.

China's and Hong Kong's standard dwelling plans detail the design of service areas but permit flexibility in internal partitioning, however, due to small dwelling sizes and fixed services locations, little deviation from standard layouts in design guides is possible. Other countries do not rely on standard design solutions but regulate plan organization to maximize design flexibility. In general, greater layout flexibility is more common in countries with integrated rental systems and universal design controls, where subsidized housing is more widely accessed. For instance, the Netherlands permit a 'free layout', only requiring a notional 'living area' that can be provided in any combination of rooms. The Swedish Building Regulations set out common requirements for open-plan layouts, while the Swiss Housing Quality Rating rewards the provision of cluster plans for the flexible living arrangements of large, shared households.

Benefit to comparative housing research: technical standards such as space standards are directly shaped by local socio-cultural norms and economic and political contexts, providing greater contextualization of housing aims, outcomes, and perceptions

Differences in housing design requirements and approaches to defining and implementing design standards partially relate to housing systems and comparative categories such as provider, tenure, or target group, however, the analysis of technical standards offers a reading of contextual and continuously transforming socio-cultural, economic, and political housing determinants not available to traditional housing system studies.

Socio-spatial reasoning

The socio-spatial reasoning of subsidized housing design and the impact of controls are particularly legible in typical dwelling plans. They reflect specific home use expectations and design conventions in each country, which determine dwelling usability and functionality.

In many Western countries, a dedicated circulation space is common, for example, a hall or a corridor, whereas in East Asian countries, the circulation space is often minimized or merged into rooms to permit direct circulation from one room to another. Kitchens might be designed to allow easy functional separation (Uruguay, Singapore, Finland) or combining them with a living room might be the norm (e.g. South Korea or Canada), which is indicative of specific local relationships between home use and occupant (). Differences in the design of circulation and kitchen spaces are, as previous research supports, particularly telling of socio-cultural norms and practices of use, privacy, and hierarchy. For instance, Ozaki (Citation2002), observed that different cultural understandings of privacy inform how internal partitions between kitchen and living areas are positioned or the location of bedrooms in relation to other functional areas.

Figure 2. Typical two-bedroom dwelling plans organized according to different design strategies (separate/combined kitchens or corridors). Differences in size and organization indicate layout efficiency strategies (combined kitchens and corridors producing smaller dwellings than separate kitchens and corridors) and different conceptualizations of home use and users. Source: Redrawn by authors based on public information from local authorities, housing associations, and housing cooperatives.

Immediately related to dwelling organization in small dwellings are universal design strategies to maximize usable floor areas, such as eliminating dedicated circulation spaces, combining corridors and rooms (China, South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong), and combining kitchens with living areas (Finland, Canada, the Netherlands, France, Sweden) (). As subsidized housing is constrained by subsidies, the construction and land acquisition cost of housing in relation to usable floor areas, number of dwellings, and housing quality have to be reconciled, often resulting in minimum permissible dwelling sizes. Unsurprisingly, the analyzed typical dwelling plans have floor areas close to the permitted minimum. For example, two-bedroom dwellings recently completed in Vancouver, Canada, are approximately 65 m2 and comparable social rent units in Scotland 60 m2. Despite the economization of floor areas, the translation of social into spatial forms remains legible in dwelling layouts.

Benefit to comparative housing research: the socio-spatial reasoning of typical dwelling plans necessitates local translations of universal design principles, which provide rich contextual understandings of housing

Although housing design strategies are in principle universal, plan solutions also spatialize socio-culturally specific practices, histories, norms, and expectations while expressing economic constraints and local housing policy and regulations, which together inform dwelling usability and functionality. The analysis of socio-spatial relationships thus provides another framework for contextual readings of subsidized housing, especially emphasizing interactions between social and spatial practices that are often overlooked in traditional housing systems studies.

Towards an interdisciplinary design research agenda in comparative subsidized housing studies

The exploration of subsidized housing through architectural design research perspectives and cross-national data on housing systems, design controls, and dwelling plans highlights the value of design research to comparative housing studies by enhancing the differentiated analysis of contextual characteristics and social aspects of housing. This provides a clarification of the two guiding questions of this paper around 1) the enhanced theorization and improved contextualization of subsidized housing and 2) the added analytical and methodological value that design research offers to subsidized housing comparisons (). It also suggests the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to cross-national studies at the intersection of architectural design research, housing studies, and policy studies to promote shared research questions and enquiries ().

Table 3. Benefits of framing comparative subsidized housing studies through design research.

Table 4. Potential interdisciplinary research agenda for comparative subsidized housing studies.

The analysis of data on international subsidized housing systems and practice identifies relationships between traditional housing study approaches and wider housing design issues, through which a comparative housing research agenda can be further advanced. It demonstrates the benefit of design research in overcoming current limitations to compare the way subsidized housing is systematized across mature, emerging, and transitioning housing markets but also to studying contextual problems and solutions. Incorporating design research improves contextualization, emphasizes social agendas and drivers, and fosters richer interdisciplinary analysis.

Contextualization of housing

Subsidized housing systems and design controls are, in principle, universal but their definition, implementation, and combination are shaped by contingency and contextual factors such as regulatory cultures and instruments, housing supply and cost, socio-technical norms and standards, socio-spatial practices, and socio-cultural conventions. Design research provides frameworks for the analysis of these aspects, with housing design instrumental to understanding the contextual and nuanced nature of subsidized housing aims, challenges, and outcomes by providing tangible evidence of housing inequity and successes.

But more studies are needed to understand design differences nationally and cross-nationally, and how these relate to different approaches to housing regulations and changes in housing policy. This requires longitudinal studies of path dependencies and historical contingencies in design controls (Alves, Citation2020). For example, the analysis suggests that in Europe, where subsidized housing has a longer history, and in countries with European influence, the form and aspects of design controls are historically contingent (Blackwell & Bengtsson, Citation2021). In other countries, immediate developmental goals can be major drivers of subsidized housing.

There are also questions concerned with the effectiveness of design controls that need to be studied using larger samples of housing plans for each country and more detailed comparisons of the controls in use. For example, do universal design controls actually result in fewer differences between private and social rental housing? Similarly, how does housing design differ between sectors in countries with differentiated design controls? More generally, what are the benefits or disbenefits of functional requirements compared to space standards or standard plans in relation to housing consistency, flexibility, and quality as well as responsiveness to policy changes? While this study analyzed the main regulatory instruments, most countries also have additional layers of mandatory and voluntary design controls for subsidized housing that should be considered.

Social housing aims and determinants

Central to subsidized housing are social aims. However, the tension of providing long-term decent housing versus affordability, often results in a focus on quantity rather than social agendas and housing quality, usability or functionality. This has resulted in a reliance on technical requirements and performance criteria such as dwelling sizes, occupancy rates, size and functions of rooms, and storage and circulation provisions to evaluate housing performance and the quality of design outcomes. More studies on the relationships between housing design and social values are needed.

While the comparative data suggests that socio-cultural norms significantly shape housing design, an important question for further study is: How are space standards calculated and socio-culturally, economically, or demographically conditioned? How and by whom is housing quality assessed? The relationship between space standards and social standards remains difficult to evaluate or translate in design terms without an interdisciplinary examination of both social and spatial histories and realities but is essential to establishing interdisciplinary housing quality metrics. Standards are often overlooked as having a fundamental impact on housing design and the assessment of housing quality but offer an important explanation of contextual socio-technical differences in housing design.

In addition, social aspects such as lived experience or housing histories need to be considered to fully capture contextual differences between housing systems and their housing production, especially from the perspective of occupants and ultimate beneficiaries of subsidized housing.

There also remains an important question to be asked about the social role of subsidized housing in different countries. As the discussion highlights, a wide range of subsidized housing models exists, some of which do not easily lend themselves to established Western-centric modes of analysis.

Interdisciplinarity research agenda

An interdisciplinary research agenda is not only useful to housing analysis but also to developing effective and responsive housing systems and supply. The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing housing inequalities and created new housing expectations and needs, which cannot be explained or addressed alone at the level of housing systems and are equally rooted in contextual housing design and regulatory problems as well as specific social norms and housing experiences. Questions of usability and quality in subsidized housing have arguably the greatest direct impact on occupants and their long-term housing satisfaction and wellbeing.

A global housing shortage, climate crisis, and demographic changes give urgency to the rethinking of a social housing agenda, which, as proposed, will benefit from an interdisciplinary housing analysis and evidence. This evidence base is valuable to local but also global policymaking, for example, for more holistic yet nuanced understandings of Sustainable Development Goals and post-pandemic housing challenges. The proposed interdisciplinary research agenda for comparative subsidized housing studies is an attempt to foreground socio-spatial problems in housing research to study and resolve design problems that are as formative to existing housing inequalities as are social and economic policy ().

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for their detailed and insightful feedback that greatly helped the development of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Seyithan Ozer

Seyithan Ozer is a Postdoctoral Research Associate (Prosit Philosophiae Foundation) in the Laboratory for Design and Machine Learning at the Royal College of Art.

Sam Jacoby

Sam Jacoby is Professor of Architectural and Urban Design Research, Research Lead of the School of Architecture, and Director of the Laboratory for Design and Machine Learning at the Royal College of Art.

Notes

1 In South Korea, while building layouts and communal areas of subsidized housing are regulated, this does not include the design of dwelling units. In Poland, space standards were abolished in 2015 when a new subsidized housing program was introduced.

References

- Alves, S. (2020) Divergence in planning for affordable housing: A comparative analysis of England and Portugal, Progress in Planning, 156, pp. 1–21.

- Appolloni, L. & D'Alessandro, D. (2021) Housing spaces in nine European countries: A comparison of dimensional requirements, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, pp. 1–19.

- Bengtsson, B. & Ruonavaara, H. (2011) Comparative process tracing in housing studies, International Journal of Housing Policy, 11, pp. 395–414.

- Blackwell, T. & Bengtsson, B. (2021) The resilience of social rental housing in the United Kingdom, Sweden and Denmark. How institutions matter, Housing Studies, pp. 1–21.

- Blackwell, T. & Kohl, S. (2019) Historicizing housing typologies: Beyond welfare state regimes and varieties of residential capitalism, Housing Studies, 34, pp. 298–318.

- Blessing, A. (2012) Magical or monstrous?, Housing Studies, 27, pp. 189–207.

- Blessing, A. (2016) Repackaging the poor? Conceptualising neoliberal reforms of social rental housing, Housing Studies, 31, pp. 149–172.

- Boelhouwer, P. (2019) The housing market in The Netherlands as a driver for social inequalities: Proposals for reform, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 1–10.

- Branco Pedro, J. (2009) How small can a dwelling be? A revision of Portuguese building regulations, Structural Survey, 27, pp. 390–410.

- Branco Pedro, J. & Boueri, J. J. (2011) Affordable housing in Portugal and Sao Paulo municipality: Comparison of space standards and socio-economic indicators, in: COBRA 2011, RICS International Research Conference Construction and Property, Salford, UK.

- Bredenoord, J., Lindert, P. V., & Smets, P. (2014) Affordable Housing in the Urban Global South: Seeking Sustainable Solutions.

- Buffel, T., Yarker, S., Phillipson, C., Lang, L., Lewis, C., Doran, P., & Goff, M. (2021) Locked down by inequality: Older people and the COVID-19 pandemic, Urban Studies, pp. 1–8.

- Bundesamt für Wohnungswesen (2015) Wohnbauten planen, beurteilen und vergleichen: Wohnungs-Bewertungs-System (Bern: Vertrieb Bundespublikationen).

- Chen, J., Stephens, M., & Man, Y. (2013) The Future of Public Housing: Ongoing Trends in the East and the West (Berlin: Springer).

- Chen, J., Yang, Z., & Wang, Y. P. (2014) The new Chinese model of public housing: A step forward or backward?, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 534–550.

- Chua, B. H. (2014) Navigating between limits: The future of public housing in Singapore, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 520–533.

- Crook, A. D. H. & Whitehead, C. (2019) Capturing development value, principles and practice: Why is it so difficult?, Town Planning Review, 90, pp. 359–381.

- Department for Communities and Local Governmen (2006) A Decent Home: Definition and Guidance for Implementation, June 2006 – Update (London: DCLG).

- Department for Communities, Housing and Digital Economy (2017) Social Housing Design Guideline 2017. Queensland Government.

- Doling, J. & Ronald, R. (Eds) (2014) Housing East Asia: Socioeconomic and Demographic Challenges (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (Cambridge: Polity Press).

- Forrest, R. & Lee, J. (2003) Housing and Social Change: East-West Perspectives (London: Routledge).

- Foster, S., Hooper, P., Kleeman, A., Martino, E., & Giles-Corti, B. (2020) The high life: A policy audit of apartment design guidelines and their potential to promote residents' health and wellbeing, Cities, 96, pp. 102420.

- Fraser, M. (2013) Design Research in Architecture: An Overview (London: Routledge).

- Friedman, R. & Rosen, G. (2020) The face of affordable housing in a neoliberal paradigm, Urban Studies, 57, pp. 959–975.

- Gallent, N., Madeddu, M., & Mace, A. (2010) Internal housing space standards in Italy and England, Progress in Planning, 74, pp. 1–52.

- Galster, G. & Lee, K. O. (2021) Housing affordability: A framing, synthesis of research and policy, and future directions, International Journal of Urban Sciences, 25, pp. 1–52.

- Hansson, A. G. & Lundgren, B. (2019) Defining social housing: A discussion on the suitable criteria, Housing, Theory and Society, 36, pp. 149–166.

- Hastings, A. (2000) Discourse analysis: What does it offer housing studies?, Housing, Theory and Society, 17, pp. 131–139.

- Haworth, A., Manzi, T., & Kemeny, J. (2004) Social constructionism and international comparative housing research, in: K. Jacobs, J. Kemeny, & T. Manzi (Eds) Social Constructionism in Housing Research, pp. 159–177 (London: Routledge).

- Hegedus, J., Lux, M., & Teller, N. (2013) Social Housing in Transition Countries (London: Routledge).

- Hoekstra, J. (2005) Is there a connection between welfare state regime and dwelling type? An exploratory statistical analysis, Housing Studies, 20, pp. 475–495.

- Hoekstra, J. (2010) Divergence in European Welfare and Housing Systems (Delft: Delft University Press).

- Housing and Regeneration Services (2018) The Glasgow Standards: A Design Schedule for Affordable Housing in Glasgow (Glasgow: Glasgow City Council).

- Housing Europe (2017) The State of Housing in the EU 2017 (Brussels: Housing Europe).

- Hu, W. & Wang, Y. (2019) Public housing as method: Upgrading the urbanisation model of Chongqing through a mega urban project, in: Proceedings of 22nd International Conference on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate, CRIOCM 2017, pp. 93–100.

- Ishak, N. H., Ariffin, A. R. M., Sulaiman, R. & Zailani, M. N. M. (2016) Rethinking space design standards toward quality affordable housing in Malaysia, in: MATEC Web of Conferences, 66, pp. 1–11.

- Karn, V. & Nystrom, L. (1998) The control and promotion of quality in new housing design: The context of European integration, in: M. Kleinman, W. Matznetter, & M. Stephens (Eds), European Integration and Housing Policy (London: Routledge).

- Kemeny, J. (1991) Housing and Social Theory (London: Routledge).

- Kemeny, J. (1995) From Public Housing to the Social Market: Rental Policy Strategies in Comparative Perspective (London: Routledge).

- Kemeny, J. (2001) Comparative housing and welfare: Theorising the relationship, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 16, pp. 53–70.

- Kemeny, J. & Lowe, S. (1998) Schools of comparative housing research: From convergence to divergence, Housing Studies, 13, pp. 161–176.

- Lau, K. Y. & Murie, A. (2017) Residualisation and resilience: Public housing in Hong Kong, Housing Studies, 32, pp. 271–295.

- Lawrence, R. J. (1981) The social classification of domestic space: A cross-cultural case study, Anthropos, 76, pp. 649–664.

- Lawrence, R. J. (1983) The comparative analyses of homes: Research method and application, Social Science Information, 22, pp. 461–485.

- Lee, J. (2003) Is there an East Asian housing culture? Contrasting housing systems of Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea, The Journal of Comparative Asian Development, 2, pp. 3–19.

- Levy-Vroelant, C. (2010) Housing Vulnerable Groups: The development of a new public action sector, International Journal of Housing Policy, 10, pp. 443–456.

- Local Government and Communities Directorate (2017) Building (Scotland) regulations, building standards technical handbook: domestic buildings (Scottish Government).

- Luck, R. (2019) Design research, architectural research, Architectural Design Research: An Argument on Disciplinarity and Identity, Design Studies, 65, pp. 152–166.

- Madeddu, M., Gallent, N., & Mace, A. (2015) Space in new homes: Delivering functionality and liveability through regulation or design innovation?, Town Planning Review, 86, pp. 73–95.

- Mafico, C. J. C. (1991) Urban Low Income Housing in Zimbabwe (Avebury).

- Malpass, P. (2008) Housing and the new welfare state: Wobbly pillar or cornerstone?, Housing Studies, 23, pp. 1–19.

- Mayor of London (2010) London Housing Design Guide (London: London Development Agency).

- McNelis, S. (2016) Researching housing in a global context: New directions in some critical issues, Housing, Theory and Society, 33, pp. 1–21.

- Milner, J. & Madigan, R. (2004) Regulation and innovation: Rethinking 'inclusive' housing design, Housing Studies, 19, pp. 727–744.

- Molina, I., Czischke, D., & Rolnik, R. (2019) Housing policy issues in contemporary South America: An introduction, International Journal of Housing Policy, 19, pp. 277–287.

- Murphy, K. M. (2015) Design and anthropology, Annual Review of Anthropology, 45, pp. 1–17.

- Murray, C. & Clapham, D. (2015) Housing policies in Latin America: overview of the four largest economies, International Journal of Housing Policy, 15, pp. 347–364.

- Neto, P. N. & Arreortua, L. S. (2019) Financialization of housing policies in Latin America: A comparative perspective of Brazil and Mexico, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1–28.

- Ozaki, R. (2002) Housing as a reflection of culture: Privatised living and privacy in England and Japan, Housing Studies, 17, pp. 209–227.

- Palm, M. & Whitzman, C. (2019) Housing need assessments in San Francisco, Vancouver, and Melbourne: Normative science or neoliberal alchemy?, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1–24.

- Parsell, C., Cheshire, L., Walter, Z., & Clarke, A. (2019) Social housing after neo-liberalism: New forms of state-driven welfare intervention toward social renters, Housing Studies, pp. 1–23.

- Preece, J., Hickman, P., & Pattison, B. (2019) The affordability of “affordable” housing in England: Conditionality and exclusion in a context of welfare reform, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1–25.

- Preece, J., McKee, K., Robinson, D., & Flint, J. (2021) Urban rhythms in a small home: COVID-19 as A Mechanism Of Exception, Urban Studies, pp. 1–18.

- Rapoport, A. (2000) Theory, culture and housing, Housing, Theory and Society, 17, pp. 145–165.

- Ravetz, A. (2001) Council Housing and Culture: The History of a Social Experiment (London: Routledge).

- Renaud, B., Kim, K.-H., & Cho, M. (2016) Dynamics of Housing in East Asia (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons).

- Ronald, R. (2011) Ethnography and comparative housing research, International Journal of Housing Policy, 11, pp. 415–437.

- Ronald, R. & Doling, J. (2010) Shifting East Asian approaches to home ownership and the housing welfare pillar, International Journal of Housing Policy, 10, pp. 233–254.

- Rowlands, R., Musterd, S., Kempen, R. V., & Kempen, R. V. (2009) Mass Housing in Europe: Multiple Faces of Development, Change and Response (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Roy, U. K. & Roy, M. (2016) Space standardisation of low-income housing units in India, International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 9, pp. 88–107.

- Scanlon, K., Whitehead, C., & Arrigoitia, M. F. (2014) Social Housing in Europe (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons).

- Schwartz, H. & Seabrooke, L. (2008) Varieties of residential capitalism in the international political economy: Old welfare states and the new politics of housing, Comparative European Politics, 6, pp. 237–261.

- Sendi, R. (2013) The low housing standard in Slovenia: Low purchasing power as an eternal excuse, Urbani Izziv, 24, pp. 107–124.

- Sengupta, U. (2019) State-led housing development in Brazil and India: A machinery for enabling strategy?, International Journal of Housing Policy, 19, pp. 509–535.

- Stephens, M. (2019) Social rented housing in the (DIS)United Kingdom: can different social housing regime types exist within the same nation state?, Urban Research & Practice, 12, pp. 38–60.

- Stephens, M. (2020) How housing systems are changing and why: A critique of Kemeny's theory of housing regimes, Housing, Theory and Society, 37, pp. 1–27.

- Stephens, M., & Norris, M. (Eds) (2014) Meaning and Measurement in Comparative Housing Research (London: Routledge).

- Stone, M. E. (2006) What is Housing Affordability? the Case for the Residual Income Approach, Housing Policy Debate, 17, pp. 151–184.

- Sullivan, B. Y. (2016) Inhabiting public housing in Hong Kong, in: W. F. E. Preiser, D. P. Varady, & F. P. Russell (Eds), Future Visions of Urban Public Housing: An International Forum, November 17-20, 1994, (Abingdon: Routledge), pp. 498–507.

- Sun, Y., Hu, X., & Xie, J. (2021) Spatial inequalities of COVID-19 mortality rate in relation to socioeconomic and environmental factors across England, The Science of the Total Environment, 758, pp1–11.

- Susanto, D., Nuraeny, E., & Widyarta, M. N. (2020) Rethinking the minimum space standard in Indonesia: Tracing the social, culture and political view through public housing policies, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 35, pp. 983–1000.

- Suttor, G. (2011) Offset mirrors: Institutional paths in Canadian and Australian social housing, International Journal of Housing Policy, 11, pp. 255–283.

- Swedish Standards Institute (2006) Building design – Housing – Interior dimensions (SS 91 42 21). Swedish Standards Institute.

- Tervo, A. & Hirvonen, J. (2019) Solo dwellers and domestic spatial needs in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area, Finland, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1–20.

- Towry-Coker, L. (2012) Housing Policy and the Dynamics of Housing Delivery in Nigeria: Lagos State as Case Study (Oyo State: MakeWay Publishing).

- Tsenkova, S. (2009) Housing Policy Reforms in Post-Socialist Europe: Lost in Transition (Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag).

- Wang, Y. P. & Murie, A. (2011) The new affordable and social housing provision system in China: Implications for comparative housing studies, International Journal of Housing Policy, 11, pp. 237–254.

- Wardrip, K., Williams, L. & Hague, S. (2011) The Role of Affordable Housing in Creating Jobs and Stimulating Local Economic Development. Center for Housing Policy. Available at https://www.opportunityhome.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Housing-and-Economic-Development-Report-2011.pdf (accessed 22 February 2022).

- Wetzstein, S. (2019) Comparative housing, urban crisis and political economy: An ethnographically based 'long view' from Auckland, Singapore and Berlin, Housing Studies, 34, pp. 272–297.