Abstract

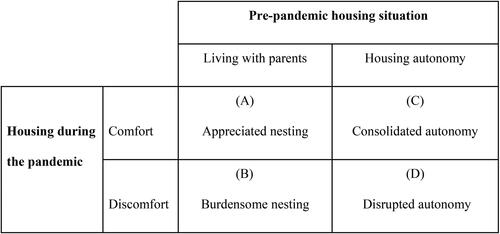

Research on housing transitions consistently points out the significance of housing autonomy and stability in young adults’ lives. While the pandemic has arguably exacerbated the already unfavorable conditions in the housing market (in terms of unaffordability and inaccessibility of quality dwellings), it is important to see how young people navigate the challenges of co-residing with parents, leaving home, and establishing housing autonomy, especially with regard to how housing transitions are embedded into broader processes of transitions-to-adulthood. Based on a qualitative study (n = 35) of young adults (ages 18–35) in Poland, the article covers the two dimensions of housing transitions in the COVID-19 era. Specifically, it accounts for the pre-pandemic housing situation (living with parents vs. housing autonomy) and the subjective housing situation during the pandemic (comfort vs. discomfort). The analysis reveals four types of (A) Appreciated nesting, (B) Burdensome nesting, (C) Consolidated autonomy, and (D) Disrupted autonomy, thus offering a new ‘ABCD’ typology for investigating housing transitions and housing paths during the crisis.

Introduction

Satisfactory housing remains one of the key anchors for the sense of safety in the modern world (Jones, Citation1995). Yet, with the concurrent increase of rental prices and the declining capacity for home ownership for the youngest generations, housing careers (spanning one’s housing mobilities and property ownership over the life-course) have become increasingly chaotic and often precarious (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017; Jones & Grigsby-Toussaint, Citation2021; Furlong & Cartmel, Citation2006; Severson & Collins, Citation2020). The complexity of housing transitions reflects the characteristics of contemporary transitions-to-adulthood: many young adults veer and glide through bouts of co-residing with parents, renting with friends, cohabitating with significant others, and other scenarios in-between (e.g., Cairns, Citation2011; Goldscheider & Goldscheider, Citation1996; Scabini et al., Citation2006). As argued by Furlong and Cartmel (Citation2006, p. 60), young people can more actively—compared to the older generations—negotiate ‘new living arrangements that fit with the complexity of their lives’.

The issue of leaving home connects housing transitions and transitions-to-adulthood, remaining one of the most important triggers or markers of gaining independence (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, Citation1996; Holdsworth & Morgan, Citation2005; Scabini et al., Citation2006). However, various trends in the housing market—particularly those linked to austerity and instability—make housing aspirations less attainable for today’s young adults in Europe and beyond (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017). Moreover, obstacles for housing transitions have been exacerbated by the ongoing crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic (Jones & Grigsby-Toussaint, Citation2021), contributing to young people feeling ‘like their life has been placed on hold’ (Vehkalahti et al., Citation2021, p. 400).

Drawing on the large-scale multi-component project, which tracks transitions-to-adulthood in Poland during social crises intergenerationally (cf. Pustulka et al., Citation2021a), this article reports on the findings from 35 individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) conducted with young men and women (ages 18–35) from different socioeconomic backgrounds, all living in large cities. Using the data from IDIs conducted in the framework of the ULTRAGEN study between May and November 2021, we showcase implications of the pandemic for young adults’ housing transitions, positioning them in the broader contexts of transitions-to-adulthood. The article seeks to answer the following research questions: How are the housing transitions of young adults in Poland affected by the pandemic? What are young Poles’ housing experiences under new circumstances? To assess these issues, we account for stability and changes in housing situations and their evaluations.

Contemporary housing transitions

In the era of dynamic shifts befalling the housing landscape, one of the seminal typologies of housing transitions by Ford et al. concludes that ‘in rare cases will a particular housing biography coincide perfectly with one of the ideal-type pathways’ (Citation2002, p. 2463). Nevertheless, the authors’ comprehensive proposal of housing trajectories entails a chaotic pathway, an unplanned pathway, a constrained pathway, a planned (non-student) pathway, and a student pathway. Three dimensions of the capacity to plan one’s move, family resources, and structural constraints (i.e., the state of the local housing market) are interlaced with the housing career under a given path. This typology adds to what Gierveld et al. (Citation1991) proposed in terms of young people engaging in housing transitions out of the parental home in order to (1) live with a partner, (2) pursue educational or occupational chances, or (3) establish independence. Heath and Cleaver (Citation2003), as well as Holdsworth and Morgan (Citation2005), underscore that housing pathways in young adulthood are always underpinned by (un)intentionality and choice (e.g., differentiating between an unwelcome co-residence due to financial strain vs. a scheduled and anticipated move to a dormitory during university education).

Crucially, both the macro-structure of the given welfare regime (or ‘transition regime’ in Walther, Citation2006) and the meso-level of the kinship network operationalized as resources available in the parental homes of young adults (Cohen Raviv & Lewin-Epstein, Citation2021; Furlong & Cartmel, Citation2006; Pustulka et al., Citation2021b), represent the key determinants of residential paths. Intergenerational factors of housing transitions retell one’s family background (i.e., socioeconomic status [SES] and family relations) (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, Citation1996; Holdsworth & Morgan, Citation2005; Scabini et al., Citation2006) and conditions on the housing market. We will now discuss these two contexts separately, followed by focusing on the Polish context, and then finalizing the section with a presentation of emerging research on the COVID-19 effects on young people’s housing transitions.

Figure 1. The ABCD typology of housing situations among young adults during the pandemic. Source: Own analysis.

Housing transitions & family

The family home typically offers a ‘safety net’ as a place where young adults can live and develop (Scabini et al., Citation2006) during ‘emerging adulthood’ as a period of exploration from the age of 18 to the mid-20s (Arnett, Citation2000). However, living with parents can be seen as both a kind of a privilege (Worth, Citation2021) and ‘an imposed lifestyle, a last resort when faced with an inaccessible housing market’ (FEANTSA, Citation2021, p. 34). A useful concept tying family-driven and societal aspects of housing transitions is the ‘privatization of welfare’ (Jones, Citation1995), which signifies that contemporary state regimes ‘outsource’ housing problems to families, so that parents are expected to sponsor independent housing of their offspring long into adulthood (Druta et al., Citation2019), possibly even after marriage (Cairns, Citation2011). Following their analysis of homeownership regimes and class inequalities in Europe, Cohen Raviv and Lewin-Epstein (Citation2021) confirm the importance of intergenerational family assistance (consisting of both financial support and transfers of assets) for the young adults’ housing outcomes. As they state, “as long as disposable incomes from labor fail to keep up with housing price inflation and alternative housing opportunities are not available to or affordable for young adults, the family will play a growing role in structuring homeownership inequality” (Citation2021, p. 20).

The dynamics of such privatized parental support are contingent on both family structure and social class. On the former, Aquilino (Citation1990) examined the parent-child housing dependencies and found that not only own marriage but also parental divorce is positively correlated with leaving home. Murphy and Wang (Citation1998) further point to the household composition in terms of numbers of children, stating that the order of birth renders oldest siblings the earliest-leavers, given that their move reduces household overcrowding. Expectations towards children moving out also increase with their age, as the parents increase pressure on housing independence for those in their late 20 s and 30 s (Avery et al., Citation1992). In the latter, social class is interlaced with age in a particular manner. Better-off parents may dissuade premature housing transitions, given that teenage pregnancy or early marriage would be misaligned with their class habitus (Avery et al., Citation1992; Furlong & Cartmel, Citation2006).

Generally, there is a U-shaped relationship between resources and age in leaving home (Berrington & Murphy, Citation1994). This means that wealthiest and most disadvantaged youths leave home earliest, either since working-class young adults are expected to fend for themselves or because well-off parents are able to fully fund independence by additional property acquisitions or financing young people’s residential needs linked to education (i.e., paying for boarding schools or university accommodation). In middle-classes, a relatively stable situation might lead to a longer stay at the parental home at a younger age, while parents’ resources later on can be used to find comfortable housing (Avery et al., Citation1992) during adult children’s attempts at cohabiting with a partner or sharing rented flats with friends/peers (e.g., Gillespie & Lei, Citation2021; Holdsworth & Morgan, Citation2005). Negotiating housing transitions in middle-class households revolves around setting up a ‘joint enterprise’ (Scabini et al., Citation2006) in which parents and young adults together decide on the ‘right reasons’ and the ‘right time’ for housing independence (Cairns, Citation2011; Holdsworth & Morgan, Citation2005). Simultaneously, young people from less central regions are likely to experience greater ‘push’ factors in relation to leaving home earlier in connection with university studies or work (Furlong & Cartmel, Citation2006). Thereby, they might achieve semi-autonomy through separate living arrangements when being away from the origin locality (e.g., Jones, Citation1995; Pustulka et al., Citation2021b), albeit that does not necessarily translate into housing stability.

Furthermore, the ideology of ‘emerging adulthood’ (Arnett, Citation2000) is not universally adopted in Poland. Krzaklewska (Citation2017) demonstrated that parents attributed young people’s prolonged co-residence to personal ineptness rather than structural factors. Pustulka et al. (Citation2021b) further examined leaving home as a function of parents’ capital. In their typology, the authors pointed out that young adults from middle-class backgrounds could ‘safely land’ in the housing market thanks to their parents financing rents and contributing to property investments. On the contrary, working-class young adults who could not count on parental capital either engaged in undesirable prolonged co-residence or needed to create their paths autonomously without family backing, often undergoing periods of housing instability.

As a result of social and economic disruptions, housing instability and insecurity tally with economic crisis and austerity-driven welfare cuts (e.g., Cairns, Citation2011). They set apart today’s European young adults from previous generations, rendering them unable to ‘settle down’ and/or benefit from having a safe home (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017). Understood as a situation in which individuals live in (and are able to maintain) an affordable place that meets their needs, housing stability is somewhat contradictory to the phenomena of both prolonged co-residence (e.g., Cairns, Citation2011) and ‘boomeranging’ (Berngruber, Citation2015), which are often viewed as ‘failures’. Thus, ‘reversed transitions’ (Furstenberg, Citation2010) are especially indicative of housing instability and biographical destabilization wherein previously achieved housing independence of the formerly launched offspring must be pursued anew (Gillespie & Lei, Citation2021). Financial independence and stable romantic relationships (esp. marriages) decrease the likelihood of prolonged co-residence and moving back home, whereas high unemployment rate, personal debt, or the dissolution of a union (i.e., separation or divorce) have an opposite effect on young adults’ trajectories (Berngruber, Citation2015; Pustulka et al., Citation2021b).

Delayed, reversed, and unsuccessful housing transitions might negatively affect prospective housing careers in relation to homeownership (Mulder, Citation2003; Worth, Citation2021). In contrast, stability can be achieved through owning a flat (also via mortgage payments) or being settled with a partner in his/her apartment and is less rarely acknowledged on the basis of cohabitation (Frederick et al., Citation2014). Similarly, boomeranging goes hand in hand with both structural and relational aspects: SES and the quality of intergenerational bonds determine the likelihood of return, which is higher for less-wealthy families, young adults with better relationships with their parents, and those who have children (Gillespie & Lei, Citation2021).

Housing regime in Poland

Although studies on young adults leaving their parental home in Poland are relatively scarce, broader changes in transition-to-adulthood need to be taken into account to understand the context. Following the end of communism (1989) and the EU accession (2004), transitions became more hybrid, including ‘old’ (sequential) and ‘new’ (prolonged/emerging) patterns (Pustulka et al., Citation2021a; Szafraniec et al., Citation2017; Sarnowska et al., Citation2018).

In comparison to young adults in other European countries where the average age of leaving home is 26.4, Polish adults transition late, namely at the age of 28.1 according to EUROSTAT data (Citation2021). In 2018, 36% of young Poles aged 25–34 lived with at least one of their parents and had not yet started their own family (GUS, Citation2020a). As recent data shows, the pandemic could have contributed (at least temporarily) to the percentage of young Poles co-residing with their parents. The rates of co-residence grew from 88.4% in 2019 to 93.6% in 2020 for the younger age cohort (18–24) and from 43.9% (2018) to 47.5% in 2020 (Eurostat, Citation2022) for the older cohort (25–34), respectively.

Various relational and structural factors are at play in housing transitions in Poland. Firstly, education lasts longer and–depending on the distance between the young adults’ family homes and educational institutions—students can decide to continue co-residing with their parents during this time. The majority of Polish university students lived off financial support from their parents, indicating a preponderance for what Goldscheider and Goldscheider (Citation1996) call ‘semi-autonomy’, that is, young people reaching residential but not financial independence (Pustulka et al., Citation2021b). Secondly, the increasing age at first marriage can influence the prolonged transition to independent living: the median age for newlyweds has risen from 24.7 for men and 22.8 for women in 1990 to 30.3 and 28.2, respectively, in 2019 (GUS, Citation2020b). Thirdly, living together as a couple might not be a realistic goal in relation to young people’s financial struggles: 60% of the young adults aged 25–34 living with parents either had no income or their average monthly income was below the minimum wage (GUS, Citation2020a). Fourthly, Poland represents a ‘north-eastern’ housing regime, marked by ‘outstandingly unfavorable opportunity structures in terms of all components of the welfare mix—market conditions (…), underdeveloped private rented sector, and seriously retrenched expenditure for social protection’ (Mandic, Citation2008, p. 632). For the latter, a significant factor is the limited availability of housing in Poland, which is caused by high prices of real estate for sale and an unregulated (private) rental market with high prices and often short-term leases, as well as weak social rental housing. Together, these conditions make young people’s housing independence challenging (cf. Szelągowska, Citation2021). While there are governmental initiatives aimed at improving the housing situation in Poland, neither previous efforts nor programs scheduled for 2022 and beyond (e.g., the National Housing Program), address the challenges of contemporary housing policy in a comprehensive, agile or young-people-centered manner (cf. Szelągowska, Citation2021). The dynamic economic reality (inflation, rising prices, energy crisis) renders the programs insufficient.Footnote1

To clarify, it is relevant to note that Poles—by and large—prefer homeownership over renting (Bryx et al., Citation2021; cf. Cohen Raviv & Lewin-Epstein, Citation2021). Thus, about 84% of Polish households live in a property they own, whereas the rental sector is relatively small and dominated by individual owners. Among those who rent, only four per cent do so via private or institutional owners, another four per cent live in social housing, and seven per cent occupy other forms of accommodation (CBRE, Citation2021). Renting is typically seen as a temporary (or forced) housing choice, which results from insufficient financial resources or lack of creditworthiness. Against this backdrop of social attitudes to housing, the prices—of the properties to buy and to rent—have been increasing. For instance, among Central European capitals, Warsaw is currently the most expensive, with a 15.1 EUR/sqm/month rental price level. Juxtaposed with the wages, rents outside the city-centre are estimated to consume around 41%Footnote2 of monthly incomes (Sękowski, Citation2022).

At the same time, negative trends characterize homeownership. Compared to the pre-pandemic year (2019), prices of residential units increased by 10.5% in 2020, namely surging by 6.2% on the primary market (new dwellings bought from developers) and by 13.8% on the secondary market (previously owned dwellings) (GUS, Citation2021). Importantly, the COVID-19 crisis has only accelerated the increase in prices already observed since 2015. Overall, compared to 2015, average prices of housing units in 2021 were higher by 49.3% (GUS, Citation2022). Thus, young Poles face difficulties in both insufficient financial resources for buying a flat or a house, even in the case of mortgaged homeownership. In order to buy a property financed with a mortgage, a young adult must have his or her own contribution of at least 10–20% of the property value (Bryx et al., Citation2021). Accumulating such capital seems especially challenging for young people, meaning that—similarly to other countries—the chance of homeownership is greater with parental support (cf. Coulter, Citation2018). Moreover, mortgages involve other potential constraints such as soaring inflation and interest rates, and the new forecast about housing shortages caused by the influx of Ukrainian refugees (Trojanek & Gluszak, Citation2022) renders the financial and housing situation more vulnerable for young adults in Poland.

The above-described structural challenges (and deficits) together with the individuals’ housing aspirations can translate into, firstly, deepening social inequalities (cf. Walther, Citation2006; Worth, Citation2021) and secondly, growing potential for social frustration (mostly) among young people. As the increase in prices and mortgage interest rates touch everyone who is planning (or has) to change a place of living, an availability of family financial or material support differentiates the situation of young adults depending on their class background (cf. Scabini et al., Citation2006; Furlong & Cartmel, Citation2006).

Housing transitions during COVID-19

While adverse housing conditions and worsening housing inequalities apply to all age-groups in the pandemic (Jones & Grigsby-Toussaint, Citation2021), it has been argued that ‘the disruption to young adults may feel especially heavy, however, because they do not yet have a long history of experience or accumulated resources to fall back on as they rework life goals or adapt to life’s disappointments’ (Bristow & Gilland, Citation2021, p. 44). The reasons behind the COVID-19 housing challenges are interlaced with worsened economic situations (e.g., lack of job opportunities, especially in the service sector), poor housing or its unaffordability, and systemic challenges within education (e.g., quality of online lectures, postponed graduations) (Vehkalahti et al., Citation2021).

Luppi et al. (Citation2021) specifically examined delayed transitions in terms of the ‘leaving home’ marker across five countries. Both objective conditions of the restrictions or lockdown and pessimistic visions of the future overlap in the revisions of the housing-related life-plans of young people in the pandemic context. In this study, young adults largely postponed their decisions to live independently, with around half of all participants making that choice (Luppi et al., Citation2021). The findings were differentiated by the welfare regime and the impact of the pandemic on the resources in the respondents’ family homes.

Qualitative longitudinal research into emerging adulthood by Vehkalahti et al. (Citation2021), which began in Finland before the pandemic and focused on rural youth, recorded greater propensity for boomeranging behaviors due to larger-scale spatial rearrangements. Reflecting the dominance of the cultural (Scandinavian) models of early independence, young adults who started living with their parents again due to the COVID-19 crisis experienced negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, or frustration.

From an intergenerational perspective, findings from a German survey reported by Walper and Reim (Citation2020) linked the subjective experiences of the crisis with the pre-pandemic family climate. It confirmed that the ‘temperature of relationships’ shapes outcomes of positive versus negative evaluation of young adults’ housing. Moreover, Timonen et al. (Citation2021) claimed that young people felt inclined to focus on their own immediate circumstances, which signified attempts at bettering relationships with parents. Apart from cohabitants (parents, partners, peers), material resources available in individuals’ homes must also be considered relevant in the COVID-19 reality. For instance, having enough space, one’s own room, and an undisturbed place were reported as differentiating factors behind youth well-being at home during lockdowns (Lips, Citation2021).

In summation, there is a dearth of research pertaining to, on the one hand, housing transitions in Poland examined with broader transitions-to-adulthood in mind and, on the other hand, housing transitions during COVID-19. Thus, this article seeks to fill this research gap by presenting the narratives around housing (in)stability and housing evaluations from the perspective of Polish young adults transitioning amidst the crisis.

Methodology

The data is derived from the first wave of an intergenerational Qualitative Longitudinal Research (QLR) study conducted in the frame proposed by Neale (Citation2020) and implemented as one of the subprojects (WP2) within the multi-component study titled Becoming an adult in times of ultra-uncertainty: intergenerational theory of ‘shaky’ transitions (acronym: ULTRAGEN).Footnote3 The broader research project, started in the pandemic context, investigates the impact of social crises on transitions-to-adulthood, treating the ongoing pandemic as the lens for tracking social change in the making.

Subsampling from the first wave of this Qualitative Longitudinal Research,Footnote4 which took place from May to November 2021, this article draws on 35 interviews with Polish young adults (ages 18–35). Given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic’s unpredictability, digital research methods were implemented, and in-depth, individual interviewing techniques were adapted to an online research setting. Before fieldwork commenced, the project was approved by the relevant Research Ethics Committee. Comprehensive project ethics information package and online informed consent forms were sent to participants prior to each interview.

Participant recruitment followed a purposeful qualitative sampling and accounted for several criteria. First, all interviewed young adults had to reside in large cities. Second, heterogeneity and balance guided the selection process for gender, education, and age, with two cohorts ultimately delineated as 18–25 (emerging adults, EA) and 26–35 (settling adults, SA). Sixteen men, eighteen women, and one non-binary person took part in the study. Twenty-one were younger than 25, while the average age stood at 24.2. During Wave 1, in terms of education, seven persons were finishing secondary schools, nine were enrolled in Bachelor-level programs, and twelve were in pursuit of further (Master’s or PhD) degrees. Another seven had exited education with a secondary school or vocational diploma and were not continuing education. Fifteen persons were working full-time; nine had temporary, part-time, or odd jobs; one had an internship; and ten people were not active in the labour market.

All of the interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. At the level of processing the entire dataset, interpretivist paradigms, and inductive approaches—i.e., proceeding from micro/individual-level to generalizations—guided the data analyses (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). The analysis began with open, inductive coding of the collected material. Based on this stage, a coding tree was designed, developed and revalidated during a team workshop when a selection of excerpts were collaboratively discussed and coded for intersubjectivity. Subsequently, all interviews were manually coded in the MAXQDA software by experienced qualitative researchers. Although the created coding system served as a main guideline for the process, invivo codes, and code-merging were fostered to improve the processing of the collected material. Moreover, extended interview summaries and analytical memos were created for each transcript.

For this article, an additional and dedicated analysis of the interviewees’ narratives pertinent to housing situation was completed. From the coding system, the following codes and subcodes were selected: housing situation, moving out of a family home, housing independence/lack of housing independence, mobility, pandemic and its influence on housing situation. After a case-by-case analysis, short descriptions of each interviewee’s experiences in the housing realm were input into a framework grid (Neale, Citation2020) in an Excel spreadsheet, with relevant quotations included. Since it was assumed that the housing situation should be seen in a broader biographical context (e.g. relations, family, work), the analytical memos describing each individual (case) served here as complementary material. Subsequently, the analysis entailed cross-case comparisons (i.e., contrasting individual cases) on the emergent and saturated (i.e., prominently featured and repeating) categories. Based on similarity of experiences and patterns found in the interviews during the analysis—four types of pandemic housing situations were created and described.

Pandemic and housing situation of young adults

Two dimensions having an impact on the housing situation of young adults were identified. The first is the pre-pandemic housing situation, which spanned main scenarios of either living with parents (with or without plans to move out; this category is referred to as ‘nesters’ due to remaining in the family home/nest) or living independently (with and without long-term housing stability). The second dimension reflects the evaluation of the housing situation (comfort vs. discomfort) in the context of the pandemic. While comfort was an umbrella term for situations in which individuals appreciated their housing situation and felt no need to change it, discomfort was conversely linked with undesirable (im)mobility. Based on data analysis, four types of pandemic housing situations were distinguished and formed an ‘ABCD’ typology of (A) Appreciated nesting, (B) Burdensome nesting, (C) Consolidated autonomy, and (D) Disrupted autonomy (). Importantly, these are non-exclusive types, meaning that the informants could shift between them over time (cf. Patton, Citation1990).

Appreciated nesting: Enjoying the comforts of being looked after

The first type (type A) broadly signified happy co-residence with parents. Interviewees with no plans to move out from their parental homes in the near future usually belonged to the younger age cohort of emerging adults (18–24). They were high-school or university students who might picture their moving out, but this plan was vague and non-immediate. Importantly, the interviewees emphasized comfort drawn from staying in the family home:

I’m thinking about [moving out], but it’d be a joint decision between me and my girlfriend. All in all, I think that it will happen rather after graduation when I change my place of residence and, maybe, I will live somewhere with my girlfriend. For now, living with my mom is comfortable and I don’t have additional expenses, […] I can buy what I want, rather than focus on the fact that I have to pay bills, rent […]. When I finish my studies, I will probably move out, this will be my goal in the next five years. By the way, it’s also not such a big plan that I have to do it for sure, but I think I will be willing to make that decision. (Mateusz, 21)

In the case of university students, staying at their parents’ place was possible when they continued education in their hometowns. Pondering the decision to move out alluded to being financially self-sufficient or having a stable job, thus revealing the significance of structural factors and means for independent living:

I’m now a third-year student and slowly more and more of my friends are moving out. I know that it’s not worth it, it’s not for me right now. Moving out would mean having a longer way to the university because I live really close to it now, [I’d also have] to pay rent, which I don’t do right now, [I’d need to] deal with food and take care of everything at the same time. It just doesn’t make sense for me right now. […] I think I’ll look into it once I have a permanent job and can afford to pay for all of it. (Kamila, 21)

Appreciated nesting was indicative of not being ready for the ‘uncomfortable’ challenges of managing one’s own household (cf. Holdsworth & Morgan, Citation2005). The young adults felt like they were being looked after and provided for; hence, they did not need to worry about either finances or chores.

The level of housing comfort during the pandemic depended on family relations and spatial aspects. The latter were usually related to remote education, especially when online activities simultaneously involved multiple household members: the young adults, their parents, and/or siblings. Some respondents specifically mentioned incurring short-term challenges in the beginning of the first lockdown, yet many problems could be resolved over time:

We had to change the Internet provider because there was a huge problem with it. The Internet was either cut for me, or [for my brother], or, alternately, for both of us as there was no Internet at all. It was definitely frustrating, […] everyone was annoyed a little bit with each other at home and everyone was fed up. Well, there were also situations where I had my microphone on, I was saying something [during the classes] and then suddenly it turned out that someone was coming into my room, or someone was shouting at home […] This is the dark side of remote learning. (Eliza, 21)

Expectedly, one’s own room has become a marker of a comfortable housing situation during the COVID-19 crisis (cf. Lips, Citation2021):

I’m a kind of a person who likes to be alone with myself, so I got through it [the pandemic] relatively calmly without any stress. Especially since I live more in the countryside now, I have lots of nice areas to explore nearby, to relax. I also have my own room upstairs and my own world […]. No brother or sister to be crowded by. (Anita, 18)

Appreciated nesting envelopes household-level consequences of social change in Poland, particularly in the way of middle-class families being able to provide material conditions for a prolonged co-residence during early adulthood (cf. Cairns, Citation2011; Goldscheider & Goldscheider, Citation1996; Scabini et al., Citation2006) Despite turning 18, the interviewees whose family homes were spatially comfortable and emotionally (relationally) unobtrusive tended to enjoy continued co-residence during the pandemic. Resultantly, this group was—in spite of the COVID-19 crisis—neither interested in what was happening on the housing market nor in their own housing transitions.

Burdensome nesting: Facing challenges with moving out

As the second type (B) shows, not all young adults felt as comfortable when co-residing with their parents. Notably, a wish to leave home was more commonly associated with the subjective views and objective markers of becoming an adult, rather than indicative of problems in parent-child relationships. In other words, views on housing transitions were motivated by romantic relationships and cohabitation readiness. However, the interviewees observed that the pandemic has caused an increase in prices in the housing market and perceived their standing in the labour market as weakened. Without sufficient savings or due to losing their jobs during the pandemic, young adults found themselves in the state of ‘waithood’ or even ‘being caught in a situation where it is possible only to ‘think about the future’ in abstract terms, without actually amassing concrete personal experience (cf. Bristow & Gilland, Citation2021; Luppi et al., Citation2021). This was especially hard for young adults who could not count on their parents to partake in the cost of housing transitions:

I would like to move out as soon as possible. It’s obvious, I mean maybe there are people who don’t want to move out but I would really like to live with my woman. She also wants to. But, as you know, the prices of the apartments are sky-high, so, for now, I’m putting money aside as much as I can. I still have a long way to go before I can move to my own [place]. (Eryk, 23)

Contrary to potentially short-term influences in type A (quality of living temporarily affected by lockdowns), the structural challenges were in the foreground in type B. Housing transitions specifically stalled, whilst the omnipresent uncertainty and worsening circumstances on the housing and labour markets could have psychological consequences in the form of a growing frustration:

Both my partner and I have to find jobs. We have been together for three years and I have a strong need to move in [together]. In order to move out [from home], the two of us have to earn at least the minimum wage to rent anything and that is really difficult. […] The pandemic certainly delayed job searches and also made me feel that we have to deal with such an invisible force, which is absolutely impossible and irrational. All these initial assumptions I had about what the housing market looks like, how easy or difficult it would be to rent an apartment, none of them turned out to be true. My intuitions or common sense were somewhere else than reality. I have this feeling of a constant struggle with this reality, which is absolutely not rational. One has to constantly fight against the front wind in order to be able to live a normal life. (Bartek, 24)

The parental homes served as stable yet concurrently heavy ‘anchors’ during the pandemic, where immobility was justified as a route to wait and ‘weather the storm’. Both the pandemic and the economic situation have disrupted the previously planned housing (and broader) transitions for those who have lost the financial capacity to create autonomous households. Young adults with lower SES and no work stability had no way of keeping their lives (and housing) plans in place during the crisis.

Consolidated autonomy: it is good to have one’s own place

Some of the study participants had started to live independently from their parents before the pandemic. They might boast both financial and housing autonomy, or have already moved out but still receive monetary assistance from their parents in the semi-autonomy scheme (e.g., Goldscheider & Goldscheider, Citation1996). Consolidated autonomy, as such, covers those who achieved their housing stability prior to the pandemic, as well as those who were able to smoothly continue their pre-pandemic housing transitions.

The interviewees who settled in autonomous dwellings before the COVID-19 outbreak seemed generally satisfied with their housing transitions:

I live [in a rented flat] close to [the city], in the countryside. I wouldn’t like moving. I am close enough that if I need something or want to go somewhere, [I can do it]. I have a lot of friends in [the city], so if I want, we can meet up for a house party or something. Then I sleep at their place. […] I love this life, peace and quiet, and I am not far from [the city], but don’t have the urge to live in the city. (Gosia, 29)

Besides reporting satisfaction with their places of residence from the spatial perspective, the interviewees also underlined feeling good about their relational choices, that is, the people with whom they lived. The pandemic did not significantly affect their sense of housing stability:

[My husband and I] have our own apartment, or we actually have a mortgage, so it’s not really ours. Still, we feel at home here. We have all creature comforts here and we feel safe with each other in all that is [happening outside]. […] I have this general feeling of being in the right place and on the right path. (Zofia, 29)

Sharing similarity with appreciative nesters, some informants living independently experienced pandemic-related short-term discomfort in their housing situations. These spanned problems with space-sharing whilst studying or working remotely:

It was like being tied up with something. The two of us here on thirty square meters, both [me and my partner] working remotely. So it was hard. […] At work there was turmoil […], too. This winter was really so hard. (Luiza, 28)

Simultaneously, Luiza’s housing situation was quite stable overall: she lived in her partner’s apartment, and they were planning to move to a bigger flat that her girlfriend already owned. Luiza furthermore decided to invest in her own flat during the pandemic and planned to acquire passive income from renting it out. Paradoxically, the pandemic could be a trigger for seeking more housing stability.

Doing well regardless of the crisis gave certain interviewees a boost in terms of self-confidence, fostering a conviction about being an autonomous adult. This was illuminated by the narratives of fulfilling pre-pandemic housing plans despite the unsettling circumstances. For Dominika, it meant moving forward with building a house alongside already owning a flat:

I live with my fiancé, who was supposed to be my husband, but we postponed our wedding plans because of COVID. We live in an apartment in [the city]; we bought it and are paying the mortgage. It is a small two-bed-apartment. We are building a house now in the countryside. (Dominika, 30)

In a slightly different scenario that contained bouts of boomeranging (Berngruber, Citation2015; Pustulka et al., Citation2021b), Adela started living in her own flat during the pandemic. In this housing transition, the apartment was acquired with her mother contributing to the down payment and mortgage:

I moved out several times. The first time was when I went abroad. Later I came back, but I already had a partner, so I lived for a short while between my parents’ place and my partner’s place because he was renting a room […]. Sometimes I slept here, other times there, until I moved in with him when he rented an [entire] apartment. I have lived with him ever since. Later there was a moment when we lived temporarily at my mom’s place, just before [she took out] the loan [for buying my flat…]. We’ve now been living at my place for a year. (Adela, 26)

As the informants’ stories showed, the possibility of consolidating one’s autonomy despite the pandemic hinges on both the pre-pandemic housing situation and the accumulated/family capital. For successful housing transitions during the crisis, structural conditions like personal, financial, and employment stability needed to be paired or aligned with support from others, primarily parents.

Disrupted autonomy: facing new circumstances

The final ideal-type describes those who lived independently pre-pandemic but had no housing stability or full financial autonomy. In other words, disrupted autonomy meant housing transitions were upended by the COVID-19 crisis. Contrary to the forced prolonged co-residentiality experienced by some of the Burdensome nesters, a number of the interviewed young adults had to transition back to the parental home or remained in a state of ‘flux’ when it came to housing during the pandemic. These unplanned changes were caused by remote education, disrupted employment, broken romantic relationships, or several of these problems overlapping:

Actually, the most intuitive option for me is to stay in [the city], […] try to develop somewhere professionally, or think about my own business [and] live at home in peace, which is also important to me, as my relationship with my parents has finally improved after years. (Klara, 19)

Klara had to navigate remote education and the end of a (toxic) relationship, deciding to go back to her parents’ home located in a smaller town. In her case, the lockdown meant a kind of reunion, with boomeranging actually ameliorating intra-family relations. Klara represented a type of reversed transition, but, as she moved out relatively early (for secondary school), the pandemic-related return home has made her consider staying with her parents longer.

Another interviewee, Mirek, left his parents’ house a few years ago and lived with his fiancée. As both of them lost their jobs during the pandemic and faced problems with paying the loan they took out to start their own business, they felt they had been caught by the COVID-19 problems with their backs to the wall. This resulted in seeking support from Mirek’s father and moving in with him:

We lived [at my dad’s place] for six months. During the pandemic I broke up with my fiancée, who went to live with her parents, and we were left with a loan to pay back. I couldn’t stand it mentally and after about two months I moved out of my dad’s house again. I’ve been living alone for some time now; I’m renting an apartment. (Mirek, 27)

Mirek’s housing trajectory was marred by the concurrent end of an engagement and being laid off with financial problems, yet he ultimately bounced back. He found a new job and decided on a housing transition to independent living once more. Similarly to the consolidated autonomy type, the story of disruption also accentuated the significance of family support for young adults’ resilience during housing (and broader) transitions.

It can be argued that good relationships with parents allowed young people to experiment with independent housing and, if necessary, use the safe-base of the family home. However, boomeranging back to the parents’ place was more often than not framed as unwanted. Thus, based on the available resources, some of the interviewees decided to maintain autonomy and looked for alternatives. This meant a decrease in housing expectations (e.g., renting smaller rooms) or ‘waiting the pandemic out’. Mieszko’s story illustrates such a ‘waithood’ practice, which can be seen as a self-imposed housing transition moratorium (cf. Arnett, Citation2000). The interviewee is navigating between the tough conditions of the housing market and his own (financial and social) resources, taking into account that structural aspects fluctuate:

Until June I rented a room [in a flat] with one of my workmates and another girl whom I didn’t even recognize because we just passed each other in the hallway. The rental contract was ending and the prices before the summer went up so much that I asked my friend if I could live with him for two months to wait it out. Thanks to another friend, whose father rents out his [secondary] apartment, I was able to find out [when] one of the tenants resigned. Since he wanted someone familiar, someone he knew, I was able to get it. I moved in on Monday. (Mieszko, 28)

Housing transitions intersected with broader life-paths of young adults affected by the pandemic, as the crisis necessitated alterations of plans in relation to mobility, employment, or romantic relations. One example of this was Laura, who stopped her gap year midway and returned to Poland because of the COVID-19 spread. She did not want to move back to her mother’s place, so she decided to rent a flat. The changes continued to be very dynamic, as she then transitioned to living with her new boyfriend. The interlocking of housing and romantic pursuits created a reversed pattern for Ela whose relationship broke down during the pandemic, requiring her to change flats. Like Laura, she framed changes in work, relationships, and housing as ‘bundled-up’ in her story of striving towards adulthood:

As regards the apartment, I have been living here since March this year, so I moved during the pandemic. At the moment I am very satisfied with the apartment I live in, also because I do not need to commute as I work entirely remotely. Everything was done remotely as well at the university, so the commute was not the key criterion, so to speak, when choosing an apartment. I live here on the outskirts of the city, and actually getting to the city centre is a bit difficult. However, I did not suffer from it because of the pandemic. It was also a move into a slightly bigger apartment […] which makes me happy […] and this is also [possible] due to finances and the job-change. (Ela, 22)

Despite the disruptions, both Laura and Ela have (unexpectedly for them) been settling during the pandemic. Thus, their cases illustrate well the potential overlapping of the four delineated types (see Ford et al., Citation2002; Patton, Citation1990) and possible changes of the individual’s life-paths over the course of the pandemic.

Discussion and conclusions

Based on the analysis, we argue that the scope of the pandemic-related disruptions in the housing situation depends on age, the individual’s economic situation, social support, and pre-pandemic housing (in)stability. On that basis, the types of (A) Appreciated nesting, (B) Burdensome nesting, (C) Consolidated autonomy, and (D) Disrupted autonomy were constructed. On the one hand, the pandemic can be seen as an accelerator of the previously existing structural challenges in the housing market.

The younger cohort of ‘emerging adults’ (18–24) appreciated being looked after by parents and saw their current housing situation as stable and safe (type A). Employing rational and lifestyle arguments, they normalized their nesting and planned to leave home only ‘at the right time’, after reaching other markers of adulthood (e.g., graduation, stable employment) (cf. Holdsworth & Morgan, Citation2005; Arnett, Citation2000). By comparison, the co-residing older cohort encompassed interviewees in their final years of studying or in longer romantic relationships, who generally found co-residence with parents cumbersome (type B). Although family was their ‘safety net’ (Scabini et al., Citation2006), starting an independent life was a primary goal. Despite their subjectively felt readiness to move out, they faced structural and personal challenges (see Jones, Citation1995) which—at the current stage of their lives—reshuffled their capacity for homeownership and resulted in a weakened ability to draw satisfaction from housing (cf. Cairns, Citation2011; Hoolachan et al., Citation2017; Mulder, Citation2003; Severson & Collins, Citation2020). Pandemic-related changes (remote education, disrupted work, increase in housing prices) have deepened their economic insecurity, thus exacerbating their housing instability and delaying their transition plans (cf. Luppi et al., Citation2021).

More broadly, the COVID-19 pandemic affected the (un)intentionality and choice of housing transitions (cf. Heath & Cleaver, Citation2003; Holdsworth & Morgan, Citation2005), with young adults’ paths becoming even more dependent on family support (cf. Cohen Raviv & Lewin-Epstein, Citation2021; Scabini et al., Citation2006). As the results have shown, the continuation of the previous plans of moving out was most likely with intergenerational backing in place (cf. Holdsworth & Morgan, Citation2005; Pustulka et al., Citation2021b).

As some of the young interviewees’ cases in Burdensome nesting and Disrupted autonomy types show, a gap between housing plans and actual individual capacities widens. On the other hand, the collected material indicates that the macro-structural changes are multifariously translated into biographical experiences, particularly being mediated by parental support or the lack thereof (Scabini et al., Citation2006; Pustulka et al., Citation2021b). The pandemic has not altered housing stability of some adults in the A (Appreciated) and C (Consolidated) types significantly: these young adults could continue with the same relational living arrangements (alone, with parents or partners), or even complete the previously planned housing transitions and investments. Any hindrances they experienced had a rather short-term character. While satisfactory employment and financial stability were paramount in conditioning the pandemic-related experiences for type C, type A demonstrated that Polish parents who are able to afford it are ready to support their offspring financially and residentially during early adulthood.

Among the cases of those facing economic and work-related difficulties and disruptions (type D), the negative impact of the pandemic was traced as most extensive and rooted in the ongoing crisis of lacking financial resources and opportunities in the housing market. For this situation to get better, the young adults would need support from parents, meaning that inequalities in parental support determine how long and how extensive the disruptions might be.

Next to the forced prolonged co-residentiality with parents, the type of Disrupted autonomy (D) illuminated the experiences of ‘shaky’ or stalled housing transitions. In relation to the pandemic, this group of young adults was most affected by boomeranging (Berngruber, Citation2015) and ‘reversed transitions’ (Furstenberg, Citation2010). The study hence confirmed emerging findings from Walper and Reim (Citation2020) and Timonen et al. (Citation2021) in a two-fold manner. First, we concur that young interviewees emphasized a renewed importance of housing stability during these difficult times. Second, we found that social support (parents, partners, friends) plays a significant role in how Polish young adults cope with uncertainty regarding housing and their broader lives. As two sides of the coin, Consolidated and Disrupted types demonstrate that relational and financial stability renders young adults either more prone to continued, smooth housing practices and transitions (type C), or makes them more exposed to challenges (type D).

As housing transitions are part of transitions-into-adulthood, it is noticeable that different markers of adulthood intersect. Thus, the unplanned disruptions of the pre-pandemic housing autonomy were often a result of other adulthood markers being upended, for instance in the form of unwelcome job changes and salary cuts or broken relationships. The analysis of the interviews shows that a pre-pandemic stability in these realms was by no means a guarantee, with vulnerability and uncertainty resurfacing among young adults across all domains (cf. Bristow & Gilland, Citation2021), parallel to the unfolding structural consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. In sum, transitions-to-adulthood and housing transitions cannot be analyzed separately: discontinuous transitions-to-adulthood were intertwined with unsettled housing transitions, while housing stability was often a reflection of one’s steadiness in other areas of adulthood—be it at work or in a romantic relationship. Here, the pandemic should not be seen deterministically, but rather as a trigger/accelerator of the previously existing inequalities and advantages. The crisis exacerbated the hybrid nature of transition models in Poland (Szafraniec et al., Citation2017), wherein social acceptance of prolonged co-residence under emerging adulthood increases non-universally, mostly for those from families with higher SES. Supported housing transitions coexist with social pressures on reaching other markers of adulthood, in particular those related to financial and relational autonomy. We argue that romantic ideals about one’s future and relational turbulence might be the underexplored factor in housing transitions (see Ford et al., Citation2002).

This article more broadly contributes to the typologies of housing transitions and paths (Ford et al., Citation2002; Gierveld et al., Citation1991), perhaps offering a somewhat easy-to-use or shorthand approach to the dynamic changes we are witnessing in the transitions during the COVID-19 era. Given the fact that a qualitative and ‘local’ study formed a basis for this typology, future work should focus on two issues. First, it would be crucial to verify whether our approach and the resulting ABCD typology with two dimensions—that is, the pre-pandemic housing situation and evaluation of the pandemic’s influence on housing—can be fittingly applied to other qualitative and quantitative work (for instance, Luppi et al., Citation2021; Vehkalahti et al., Citation2021). It would be particularly relevant to see studies dedicated to young people’s housing as not only the pandemic but multiple, other social crises unfold. Second, since Poland represents a particular transition regime (Druta et al., Citation2019; Mandic, Citation2008; Walther, Citation2006), comparative studies are needed to overcome the single-country focus present in contemporary qualitative research on housing. Taking into account the experts’ expectations of further increase in prices of residential dwellings and market rents (Deloitte, Citation2021) further exacerbated by the 2022 refugee influx (Trojanek & Gluszak, Citation2022) and the energy crisis, the affordability of desired housing might become more difficult now than ever before.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Justyna Kajta

Justyna Kajta, PhD, sociologist. Her research interests include youth, political engagement, social inequalities and biographical methods. The author of the works published e.g. in Intersections. East European Journal of Society and Politics, European Review or Qualitative Sociology Review. Post-doc in the ULTRAGEN project.

Paula Pustulka

Paula Pustulka, PhD, is a sociologist working at the intersection of youth, family and migration studies. Her research has been published, among others, in Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Journal of Youth Studies and Journal of Education and Work. She is the Director of the Youth Research Center and Principal Investigator for ULTRAGEN.

Jowita Radzińska

Jowita Radzińska, PhD, is a sociologist and ethicist. Her area of expertise is solidarity and sociology of morality. Her research has been published, among others, in Studia Socjologiczne, Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej, Etyka. Member of ESA, PTS and VOICES (Making Young Researchers’ Voices Heard for Gender Equality). She holds a scholarship in the ULTRAGEN project.

Notes

1 Some of the earlier housing programs introduced by the Polish government, for instance Mieszkanie Plus (Apartment Plus) or Mieszkanie dla Młodych (Housing for the Young), seemingly caused no change to the negative trends on the housing market (cf. Szelągowska, Citation2021). In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Polish government proposed the legislative package of measures intended to counteract the direct economic effects of the crisis. The measures introduced in 2020 included financial benefits for parents caring for children under 8, support for employers to cover wages during reduced shifts or discontinuation of work, and grants for entrepreneurs. Directed primarily towards families with children and established workers/employers, the governmental help focused neither on problems of young adults, nor related to offsetting housing challenges. While it could reduce general economic hardship, it is difficult to see its impact on the otherwise worsening housing market (cf. Szelągowska, Citation2021). Regarding housing in particular, the Polish government introduced a new program called Mieszkanie bez wkładu własnego (Housing without ‘own contribution’) in May 2022. Beneficiaries of this relief program, which is part of the wider ‘Polish Deal’ restoration fund, will receive a government-backed bank guarantee for real estate investments. The guarantee is supposed to be a ‘promise’ that, if the program participant fails to cope with the repayment of the mortgage, the bank will recover part of the debt. According to the announcements, subsidies will also be granted in the form of housing vouchers. Since the program has just begun in May 2022, no data on its take up and effects is available at present.

2 The average monthly cost of renting a one-room apartment outside Warsaw city centre and the average net salary in the city were used to calculate the percentage of salary. Among the studied capitals, Bern (Switzerland) is reported as the city with the lowest (19%), and Valletta (Malta) with the largest (73%) percentage of salary spent on rents.

3 This work is supported by Narodowe Centrum Nauki/National Science Center Poland under the grant number 2020/37/B/HS6/01685.

4 The study will entail two waves of interviews (second wave is planned for autumn/winter 2022) and at least one asynchronous exchange (March-April 2022).

References

- Arnett, J. J. (2000) Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties, The American Psychologist, 55(5), pp. 469–480.

- Aquilino, W. S. (1990) ‘The likelihood of parent–adult child coresidence: Effects of family structure and parental characteristics, Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52(2), pp. 405–419.

- Avery, R., Goldscheider, F. & Speare, A. (1992) Feathered nest/gilded cage: Parental income and leaving home in the transition to adulthood, Demography, 29(3), pp. 375–388.

- Berngruber, A. (2015) ‘Generation boomerang’ in Germany? Returning to the parental home in young adulthood, Journal of Youth Studies, 18(10), pp. 1274–1290.

- Berrington, A. & Murphy, M. (1994) Changes in the living arrangements of young adults in Britain during the 1980s, European Sociological Review, 10(3), pp. 235–257.

- Bristow, J. & Gilland, E. (2021) The Corona Generation. Coming of Age in a Crisis (Washington: Zer0 Books, John Hunt Publishing).

- Bryx, M., Sobieraj, J., Metelski, D. & Rudzka, I. (2021) Buying vs. Renting a Home in View of Young Adults in Poland, Land, 10(11), 1183.

- Cairns, D. (2011) Youth, precarity and the future: undergraduate housing transitions in Portugal during the economic crisis, Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, 66, pp. 9–25.

- CBRE (2021) European Multifamily Housing Report. https://www.cbre.pl/pl-pl/raporty/European-Multifamily-Housing-Report-April-2021.

- Cohen Raviv, O. & Lewin-Epstein, N. (2021) Homeownership regimes and class inequality among young adults, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 62(5), pp. 404–434.

- Coulter, R. (2018) Parental background and housing outcomes in young adulthood, Housing Studies, 33(2), pp. 201–223.

- Deloitte. (2021) Property Index. Overview of European Residential Markets. 10th Edition. Available at https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/at/Documents/real-estate/at-property-index-2021.pdf (accessed 08 March 2022).

- Druta, O., Limpens, A., Pinkster, F. M. & Ronald, R. (2019) Early adulthood housing transitions in Amsterdam: Understanding dependence and independence between generations, Population, Space and Place, 25(2), e2196.

- Eurostat (2021) Age of young people leaving their parental household. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Age_of_young_people_leaving_their_parental_household&oldid=494351 (accessed 01 March 2022).

- Eurostat (2022) Share of young adults aged 18-34 living with their parents by age and sex - EU-SILC survey[ilc_lvps08], Available at http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_lvps08 (accessed 8 July 2022).

- FEANTSA (Fondation Abbé Pierre. 6th Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe) (2021) Available at https://www.feantsa.org/public/user/Resources/News/6th_Overview_of_Housing_Exclusion_in_Europe_2021_EN.pdf (accessed 08 March 2022).

- Ford, J., Rugg, J. & Burrows, R. (2002) Conceptualising the contemporary role of housing in the transition to adult life in England, Urban Studies, 39(13), pp. 2455–2467.

- Frederick, T. J., Chwalek, M., Hughes, J., Karabanow, J. & Kidd, S. (2014) How stable is stable? Defining and measuring housing stability, Journal of Community Psychology, 42(8), pp. 964–979.

- Furlong, A. & Cartmel, F. (2006) Young People and Social Change (New York: McGraw-Hill Education).

- Furstenberg, F. F. Jr. (2010) On a new schedule: Transitions to adulthood and family change, The Future of Children, 20(1), pp. 67–87.

- Gierveld, J. D. J., Liefbroer, A. C. & Beekink, E. (1991) The effect of parental resources on patterns of leaving home among young adults in The Netherlands, European Sociological Review, 7(1), pp. 55–71.

- Gillespie, B. J. & Lei, L. (2021) Intergenerational solidarity, proximity to parents when moving to independence, and returns to the parental home, Population, Space and Place, 27(2), e2395.

- Goldscheider, F. K. & Goldscheider, C. (1996) Leaving Home Before Marriage: Ethnicity, Familism, and Generational Relationships (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press).

- GUS (2020a) Pokolenie gniazdowników w Polsce. Available at https://stat.gov.pl/statystyki-eksperymentalne/jakosc-zycia/pokolenie-gniazdownikow-w-polsce,6,1.html (accessed 18 February 2022).

- GUS (2020b) Rocznik demograficzny (Demographic Yearbook of Poland). Available athttps://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/rocznik-demograficzny-2020,3,14.html (accessed 18 February 2022).

- GUS (2021) Obrót nieruchomościami w 2020 r. Available at https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/infrastruktura-komunalna-nieruchomosci/nieruchomosci-budynki-infrastruktura-komunalna/obrot-nieruchomosciami-w-2020-roku,8,4.html (accessed 18 February 2022).

- GUS (2022) Wskaźniki cen lokali mieszkalnych w 3 kwartale 2021 r. Available athttps://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5464/12/13/1/wskazniki_cen_lokali_mieszkalnych_w_3_kwartale_2021_r.pdf (accessed 1 June 2022).

- Heath, S. & Cleaver, E. (2003) Young, Free and Single? Twenty-Somethings and Household Change (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Holdsworth, C. & Morgan, D. (2005) Transitions in Context: Leaving Home, Independence and Adulthood: Leaving Home, Independence and Adulthood (Maidenhead: Open University Press).

- Hoolachan, J., McKee, K., Moore, T. & Soaita, A. M. (2017) ‘Generation rent’ and the ability to ‘settle down’: economic and geographical variation in young people’s housing transitions, Journal of Youth Studies, 20(1), pp. 63–78.

- Jones, G. (1995) Leaving Home (Buckingham: Open University Press).

- Jones, A. & Grigsby-Toussaint, D. S. (2021) Housing stability and the residential context of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cities & Health, 5:sup 1, pp. S159–S161.

- Krzaklewska, E. (2017) W stronę międzypokoleniowej współpracy? Wyprowadzeniesię z domu rodzinnego z perspektywy dorosłych dzieci i ic hrodziców, Societas/Communitas, 2(24), pp. 159–176.

- Lips, A. (2021) The situation of young people at home during COVID-19 pandemic, Childhood Vulnerability Journal, 3, pp. 61–78.

- Luppi, F., Rosina, A. & Sironi, E. (2021) On the changes of the intention to leave the parental home during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison among five European countries, Genus, 77(1), pp. 10–23.

- Mandic, S. (2008) Home-Leaving and its structural determinants in Western and Eastern Europe: an exploratory study, Housing Studies, 23(4), pp. 615–637.

- Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage).

- Mulder, C. H. (2003) The housing consequences of living arrangement choices in young adulthood, Housing Studies, 18(5), pp. 703–719.

- Murphy, M. & Wang, D. (1998) Family and sociodemographic influences on patterns of leaving home in postwar Britain. Demography, 35(3), pp. 293–305.

- Neale, B. (2020) Qualitative Longitudinal Research: Research Methods (London, New York: Bloomsbury Publishing).

- Patton, M. (1990) Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage).

- Pustulka, P., Radzińska, J., Kajta, J., Sarnowska, J., Kwiatkowska, A. & Golińska, A. (2021a) Transitions to adulthood during COVID-19: Background and early findings from the ULTRAGEN project, Youth Working Papers 4/2021, Warsaw: SWPS University – Youth Research Center, doi: 10.23809/14.

- Pustulka, P., Sarnowska, J. & Buler, M. (2021b) Resources and pace of leaving home among young adults in Poland, Journal of Youth Studies, 25(7), pp. 946–962.

- Sarnowska, J., Winogrodzka, D. & Pustułka, P. (2018) The changing meanings of work among university-educated young adults from a temporal perspective, Przegląd Socjologiczny, 67, pp. 111–134.

- Scabini, E., Marta, E. & Lanz, M. (2006) The transition to adulthood and family relations: An intergenerational approach (Hove and New York: Psychology Press).

- Sękowski, O. (2022) Drogi najem w Warszawie? W Europie jest drożej. Heritage Real Estate. Available at https://heritagere.pl/drogi-najem-w-warszawie-w-europie-jest-drozej/ (accessed 25 February 2022).

- Severson, M. & Collins, D. (2020) Young adults’ perceptions of life-course scripts and housing transitions: an exploratory study in Edmonton, Alberta. Housing, Theory and Society, 37, pp. 214–229.

- Szafraniec, K., Domalewski, J., Wasielewski, K., Szymborski, P. & Wernerowicz, M. (2017) eds. Zmiana Warty. Młode pokolenia a transformacje we wschodniej Europiei Azji (Warszawa: Scholar).

- Szelągowska, A. (2021) Wyzwania współczesnej polityki mieszkaniowej, Studia BAS, 2, pp. 9–33.

- Timonen, V., Greene, J. & Émon, A. (2021) We’re meant to be crossing over … but the bridge is broken’: 2020 university graduates’ experiences of the pandemic in Ireland, YOUNG, 29(4), pp. 349–365.

- Trojanek, R. & Gluszak, M. (2022) The War in Ukraine, Refugees, and the Housing Market in Poland, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4086551.

- Vehkalahti, K., Armila, P. & Sivenius, A. (2021) Emerging adulthood in the time of pandemic: the COVID-19 crisis in the lives of rural young adults in Finland, YOUNG, 29(4), pp. 399–416.

- Walper, S. & Reim, J. (2020) Young people in the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from Germany, International Society for the Study of Behavioural Development Bulletin, 2, pp. 18–20.

- Walther, A. (2006) Regimes of youth transitions: choice, flexibility and security in young people’s experiences across different European contexts, Young, 14(2), pp. 119–139.

- Worth, N. (2021) Going back to get ahead? Privilege and generational housing wealth, Geoforum, 120, pp. 30–37.