ABSTRACT

In India, gender inequalities have deleterious effects on reproductive health outcomes among women and girls. This study used an interactive storytelling game as a qualitative data collection approach to learn about adolescents’ experiences and societal norms regarding gender. Eight sessions were conducted with a total of 30 girls and 10 boys (ages 15–17). Participants created characters, themes, and locations for the stories and shared experiences about gender through their characters. Sessions were recorded, transcribed, translated, and analysed for emergent themes. Themes included: interest in and prevalence of romantic relationships among adolescents, stigma associated with adolescent relationships and its influence on individual norms, and girls’ experiences of harassment. Findings suggest that the use of a qualitative storytelling game is one way to understand the experiences of adolescents around sensitive issues such as gender. They also suggest a need for interventions focused on improving gender attitudes among adolescents, fostering parent–child communication, and strengthening the policy response to girls’ harassment.

Introduction

Gender inequalities contribute to poor reproductive health outcomes. For example, gender inequalities are associated with limited access to reproductive health care for women, and increased sexually transmitted infections for both men and women (Banda et al., Citation2017; Namasivayam et al., Citation2012). Globally, women and girls bear the burden of poor reproductive health outcomes, including early pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and sexual violence (Morris & Rushwan, Citation2015). Gender roles are established early in life and are often reinforced in puberty, leading to lifelong patterns of gender-prescriptive behaviours and unequal access to resources (Kagesten et al., Citation2016). The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal #5, achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls, highlights the importance of advocating for gender equity over the life course (UN General Assembly, Citation2015). Recently, adolescence has emerged as a critical time point that is particularly amenable to social interventions.

To design effective social interventions for adolescents, it is crucial to understand gender within the sociocultural contexts that adolescents live in (Barker et al., Citation2010). However, there are numerous challenges to obtaining information from adolescents about their experiences. For instance, adolescents may be disengaged with research and view participation as a chore or boring task (Bassett et al., Citation2008; Tilbury et al., Citation2008; Yeatman & Trinitapoli, Citation2011). Perceived power differentials with researchers can also cause discomfort and limit open expression (Drew et al., Citation2010).

Participatory, narrative-based research methods are one approach to overcome these challenges. These methods make the research process more enjoyable for adolescents, build trust, and mitigate power differentials (Drew et al., Citation2010; Flanagan et al., Citation2015; Mmari et al., Citation2017). To that end, games are emerging as a desirable tool for conducting adolescent health research. Games are engaging, informal, and fun, while providing a loose structure for interaction (Bochennek et al., Citation2007; de Freitas, Citation2018). Previous research has shown the potential of using games as a data collection tool. Structured games have been used as quantitative assessment tools (Maclachlan et al., Citation1997). Games have also been used in group settings for qualitative data collection (Long et al., Citation2015; Yonekura & Soares, Citation2010).

This study describes the use of a storytelling game as part of a qualitative data collection approach with adolescents from Uttar Pradesh (UP), India to learn about their experiences with gender. Nearly one-fifth of India’s adolescent population resides in UP (Census of India and United Nations Population Fund- India, Citation2011), making it an important site for exploring their experiences. Furthermore, gender inequities among adults in this region are stark: only 45% of women are literate compared to three-quarters of men (International Institute for Population Sciences, Citation2017), and only 15–27% of women participate in the labour force, compared to 78–82% of men (World Bank, Citation2016). Over the past decade, the Indian government has increased efforts to improve the status of adolescent health. In 2014, India launched a national health strategy to improve adolescent health, including their reproductive health (Welfare, Citation2014). In light of these developments, it is essential to conduct research to understand the social context that contributes to gender disparities and subsequent reproductive health outcomes among Indian adolescents.

Methods

Game development

We developed a storytelling game as part of the parent project Kissa Kahani, a research study that explores sexual and reproductive health issues among Indian adolescents using both quantitative and qualitative methods. The storytelling game was developed to learn how Indian adolescents experience gender-based discrimination in their context.

A primary objective of the game was to reduce participant discomfort associated with discussing difficult topics like gender. We developed the storytelling game as a qualitative data collection approach and a participatory way to operationalize the best-friend report method, wherein adolescents answer questions about their best friend (Yeatman & Trinitapoli, Citation2011). In addition, it included aspects of a focus group discussion as occasionally the facilitator provided prompts as ways to probe for content. The game play was adapted from Rumour Mill, a popular storytelling game within the United States wherein players tell stories using real or fictional characters.

The game was developed in a University-based game development lab in the United States, pilot tested and refined with Indian adolescents, and translated into Hindi. The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board approved all protocols and procedures for this study.

Game participants

Girls and boys aged 15–17 years residing in the urban slums of Lucknow city, capital of UP, were recruited with support from local NGOs. Parental consent and participant assent were obtained. Game sessions were conducted at a local public school and participants were compensated for their time.

Game sessions

Game sessions involved five players of the same gender and one gender-matched local facilitator. Facilitators were trained by University researchers.

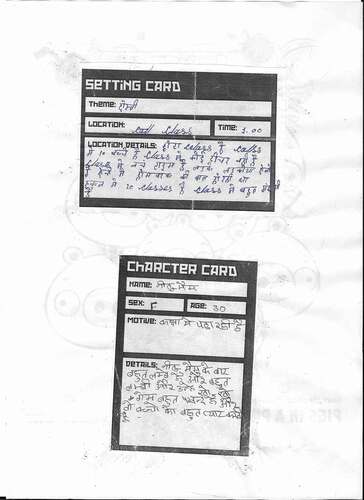

Players participated in the storytelling game as described in . Each game round was stopped after 15–20 minutes. Once gameplay finished, facilitators led guided discussions in which players were asked to explain why they created particular characters, or took certain actions (e.g. why did your character miss school or why did she not tell her mother that she was going to meet her boyfriend? See ).

Table 1. Storytelling game setup and rules

Table 2. Storytelling game discussion questions

In sessions where players struggled with creating characters or taking actions connected to the game theme, facilitators created example character cards, and at times took actions to introduce gender-related topics, similar to the use of narrative prompts by facilitators in focus groups. Game sessions in which the facilitator made such suggestions were noted. Furthermore, as the topic of sexual harassment arose in several of the early games, the facilitator suggested sexual harassment as a possible theme in subsequent sessions in order to further explore this topic with adolescents.

Data analysis

Session discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed, translated into English, and de-identified. The India-based team verified all transcribed and translated documents for accuracy.

Data analysis was conducted manually by Chicago- and India-based research team members. One team member was of Indian origin and had reading and writing-level proficiency in Hindi.

All of the game assets, including the setting, theme, and character cards; action tracking sheets; and discussion transcripts were included in the analysis. Since this dataset was small, the team analysed the data without the use of qualitative analysis software. To begin the narrative analysis, team members reviewed all assets in English (Reissman, Citation1993). The team members with Hindi language skills also reviewed assets in Hindi. Next, team members met to discuss their initial observations of the data. Data fell into six broad categories using a variety of data sources: salient topics (game and discussion transcripts); use of gender in creating characters (game); decisions made regarding game settings (game); actions taken by players (action tracking sheet); emergent themes and supporting quotations (action tracking sheets). Each research team member then took assets from two to three game sessions and organized the data for each session according to the above categories. Organizing the data in categories allowed the team to compare and contrast data within and across the sessions and to identify patterns in the data.

Next, each team member wrote an analytic memo describing the main findings related to gender based on their in-depth analysis of the organized assets for their two-three assigned game sessions. These memos were circulated among the research team including field staff in India to make further additions and check data accuracy.

The team met once more to resolve any disagreements and clarify gaps in their understanding about the memos before finalizing the analytic memos.

Results

Eight game sessions were conducted from April-July 2016. Forty adolescents, 30 girls and 10 boys, ages 15–17, participated (). A significant majority of the participants were Hindu, unmarried, and belonged to the scheduled caste.

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of Kissa Kahani storytelling game participants, April-July 2016, by gender

Each game session lasted approximately three hours including the post-game discussion. Six of eight game sessions generated stories related to gender and relationships (five out of these six sessions received some input from the facilitators). provides a summary of emergent themes and descriptions of locations and characters created by participants. Two sessions (sessions 3 and 7) that were on bullying were dropped from final analysis since they were not related to gender and relationships.

Table 4. Emergent themes from all storytelling game sessions

A majority of the stories were set in school, based on conversations that adolescents have when the teacher is not in class (during lunch break or between classes). Analysis of the post-game discussions showed that most participants created characters that were inspired by individuals in real life – peers at school, neighbourhood and family members, or friends.

Data on gender led to the realization of three main themes: interest in and pursuit of romantic relationships, presence of strong social taboos against romantic relationships and their subsequent influence on individual norms, and harassment of girls on the streets and via social media.

Indian adolescents are interested in romantic relationships

Adolescent romantic relationships were discussed in multiple game sessions. In one session, female players discussed romantic relationships while creating a story about school friends. Topics included the right age for getting a boyfriend, the credentials of a good boyfriend, and the importance of marriage in a girl’s life. Below are a few actions that were taken in this session:

Kajal says that to make a boyfriend is very easy. And he should be nice, handsome, good in studies, should be loving.

Meena says oh that’s okay but we are 15 do we need to have a boyfriend?

Meena says I would like to have a boyfriend because later we get married

Meena asks do I have to marry the one who is my boyfriend?

Shayestha says it is up to you at what age you have to have a boyfriend

Arachana says but I will marry my boyfriend. But he should be of my age, my caste, so that parents have no problem.”

During the post-game discussion, a girl from this session shared her observation of actions taken by other girls in real life to draw the attention of boys at school events:

But there are some girls who like it when boys hear their conversation. When we go in some rally, where many other schools also participate then girls ask for boys contact numbers. In our school mobile phones are not allowed but girls still brings on mobile phone. And before leaving the school they get ready, they wear makeup, and fold their skirts up so that they look like short skirts. When school time is over you can see so many boys standing outside and waiting for girls.’

In another post-game discussion, participants described secret ways in which adolescents meet each other:

[…] Like when we go on school picnic, many girls inform their boyfriends/friends in advance. So they also arrive at the picnic spot. And girls also say hello to unknown boys while sitting in school bus.’

Descriptions of romantic relationships that emerged during the game play and post-game discussions, like in the above examples, reveal how romantic relationships are of interest to adolescents.

Adolescent interactions are socially proscribed

Sessions also revealed difficulties faced by boys and girls in interacting with each other. Some participants believed characters in the game, especially girl characters, would face severe negative consequences from parents and other family members for being involved in romantic relationships. Perceived consequences of being romantically involved with boys included losing access to education or reduced freedom of movement. Players shared that being seen with a boy by a family or community member could also be an antecedent to early marriages. In one discussion, girls described the pathway that leads to early marriage:

Because of this, girl get married at early age also. Like at the age of 14 or 15 if they have a boyfriend and their family comes to know about this, so they are scared that she may elope and thus they get her married at an early age.

In other words, romantic relationships among adolescent are a source of shame and fear for families. In response, parents may decide to marry their daughters at a young age to a partner selected by the family.

In the post-game discussion, several girl players described romantic relationships as a source of personal shame, echoing beliefs about relationships held by family and community members. They voiced their concerns about boys being casual in their attitude towards relationships. Girls in one session noted that it was important for a girl not to have sex with her boyfriend, as he would lose respect for her if she agreed and choose not to marry her later on:

They [boys] get into a relationship but they are not serious and then later they marry someone else. They only do time pass with girls.’

Here, boys, despite their own interest in relationships, suggest that girls who date are not marriageable:

Would the boy agree to marry the girl if her parents didn’t scold him?

No.

He will refuse thinking that when she is doing bad things with him, in future she might do the same with some other person and that would in turn spoil his life.

What do you mean by doing bad things?

Bad things like meeting, kissing.”

Thus, despite their interest in relationships, adolescents sometimes express similar views as adults around them that relationships are a source of shame and stigma, particularly for girls.

Girls commonly experience harassment

In other game sessions, girls created stories about another potential danger in relationships – the harassment of young women by boys via social media. In one post-game session, a participant described her neighbour’s encounter with online harassment:

“Sometimes girls make their profiles on social networking sites such as Facebook or Whatsapp, but boys can trap them by using fake id’s and photographs, and they can also misuse girls’ photographs.[…] there was a girl in my neighborhood, her boyfriend used to blackmail her that if you will not come to my room then I will show your pictures to your parents, she was forced to go to his room to meet him.”

After the theme of girls’ harassment arose in several sessions with the girl players, to elicit further information, facilitators asked boys in one session (session 4) to use the theme of harassment. Boys in this session took game actions concerning the harassment of girls in public places, ways in which girls deal with street-level harassment, and possible actions that those standing nearby might take. Below are examples of actions that were taken in this session:

: Akash saw to Mamta on the fruit shop, he intentionally touched his body with Mamta.

Mamta is saying to Akash walk carefully, you are misbehaving.

Akash starts arguing with Mamta.

Mamta is trying to make Akash understand, actually she wants to avoid conflict. The shopkeeper also started to scold to Akash.”

The post-game discussion from this session surfaced information on boys’ views of harassment. Boys expressed a strong disapproval of harassment and suggested strategies for girls to use in response, including shouting for help, calling the police, and using physical force.

Mamta could not face him physically, whatever she can do, she can do only verbally, she was abusing him verbally.

If someone is harassing a girl and she can’t raise her hand on him, I mean she can’t physically face him, then what she can do?

She can shout or call someone for help. Or she can make a phone call and inform someone that someone is harassing me. She can take these actions.

She can also call the police. She can also slap that boy.”

In this instance, boys may have imagined that girls have more control and authority in these situations than is typical. In the post-game discussion for another session, girls described being rather powerless in harassment situations. For example, a participant described how her efforts to solicit help from her school and the police for addressing harassment were ignored.

What happens then? Does your school take any action?

No didi, nothing happens.

Have you ever complained about this (harassment)?

Yes, we have complained several times but no one listens. Like we have also complained to the police but they say, never mind, you go home and do not pay attention to them.”

Discussion

In India, prevailing gender norms that uphold son preference, male superiority, and unequal access to resources, have negative effect on various aspects of women and girls’ lives, including their sexual and reproductive health (Nanda et al., Citation2014). Gender inequities often emerge and are reinforced in adolescence (Basu et al., Citation2017; Kagesten et al., Citation2016; Mmari et al., Citation2017). These initial inequalities can lead to lifelong inequity. Specifically, gender inequities result in women and girls lacking autonomy in family planning decision-making and experiencing gender-based violence (Morgan et al., Citation2017; Peitzmeier et al., Citation2016; Rahman et al., Citation2013). As such, eliciting information from adolescents about their experiences with gender and relationships is essential for early intervention. However, obtaining information from adolescents can be challenging given the sensitive nature of these topics (Bassett et al., Citation2008).

The use of a storytelling game as a qualitative data collection method elicited adolescent experiences around gender and relationships and provided important insights into hidden moments of young people’s lives. Players described sexual harassment experiences and the complexities of romantic relationships in a conservative Indian context. Previous research on adolescents in India describes romantic relationships between boys and girls as stigmatized or forbidden, but they are nonetheless happening (Alexander et al., Citation2006; Hindin & Hindin, Citation2009; Santhya et al., Citation2011). Romantic relationships were a common theme in our game sessions. We found that in spite of social taboos against romantic relationships, they do occur among adolescents. Participants may have been more forthcoming about these stigmatized issues because the game allowed them to discuss sensitive subjects in the third person, as friends or characters. This finding about the game aligns with other research that has identified the best friend method as a potentially more reliable way to get data on sensitive subjects from adolescents (Yeatman & Trinitapoli, Citation2011).

As in the current study, other studies on romantic relationships also found that there are more serious consequences for girls involved in romantic relationships than boys (Abraham, Citation2002; Hindin & Hindin, Citation2009). Some researchers have connected the double standard and obligate secrecy to risky sexual behaviours among boys (Nahar et al., Citation2013).

The widespread harassment of girls in public places by men and boys described by participants in our study is also consistent with other studies on harassment of girls in public space across India (Akhtar, Citation2013; Chakraborty, Citation2016; Talboys et al., Citation2017; Tripathi et al., Citation2017). In addition to being psychologically distressing (Betts et al., Citation2018; Davidson et al., Citation2016), the harassment of girls in public spaces can lead to curtailed mobility and limited educational attainment, which affects their access to health services (Borkar, Citation2017; Chakraborty, Citation2016). Our data, like other Indian studies, finds that victims perceive the police and other formal avenues of prevention and redress as unhelpful (Bhatla et al., Citation2013; Bhattacharyya, Citation2016). The pervasive nature of gender-based harassment in public spaces coupled with the inadequacy of current systems demands a robust, national-level response.

Stories shared by study participants about online harassment of girls’ mirror those described in other Indian studies on cybercrimes (Halder & Jaisankar, Citation2010). Based on their findings, Indian girls are often unaware of the potential risks posed from sharing personal information on online chat platforms (Halder & Jaishankar, Citation2013). In addition, female victims hesitate to report incidents of harassment due to fears about dishonouring their family and hurting their likelihood of getting married (Saha & Srivastava, Citation2014; Umarhathab et al., Citation2009). Further investigation into online harassment of girls and development of suitable interventions to support girls is urgently needed.

This study has certain strengths and limitations. The potential for a storytelling the game to tap into stories about risky or stigmatized behaviours among young people that may be otherwise hard to obtain is a strength. Additionally, providing adolescents with the opportunity to participate in an interactive research activity may have helped with shifting some of the power and control traditionally held by the research team over to the participants. Doing so may also have increased participants’ interest and engagement. Finally, the game successfully engaged boys in conversations about gender.

With regards to limitations, the open format of the game made it difficult to ensure that each game session connected to the research question without facilitator input. Thus, in hindsight, introducing increased structure at the outset by setting the topic for each game session to ensure relevance to research questions may have been prudent.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a storytelling game can serve as a qualitative data collection tool to elicit sensitive information on gendered experiences in an engaging manner. This method may have reduced the level of stress experienced by study participants when compared to using traditional research methods to explore sensitive issues (Elmir et al., Citation2011).

This study also adds to the body of research that suggests that Indian adolescents are entering into romantic relationships despite a lack of support from family and community members, and that harassment of women is a pervasive issue in India. Combined, these findings shed light on prevailing gender norms and help to understand the process of gender socialization in India. They illuminate the role of the environment – family, media, and community – in shaping young people’s attitudes and beliefs about themselves and about gender, and offer important insights for developing suitable interventions.

Our findings suggest that interventions for adolescents should be tailored towards challenging and shifting inequitable and restrictive gender norms, equipping adolescents with healthy relationship skills, and preventing harassment by young men. Male participants in this study expressed strong disapproval of girls’ harassment which suggests that boys can be allies in preventing harassment against girls and their involvement must be encouraged in programmes that aim to reduce harassment.

Simultaneously, changing attitudes of parents towards youth interactions and encouraging greater parent–child communication on relationship topics is needed to foster gender-equitable attitudes among adolescents. In addition, structural interventions that strengthen the response from law and order to protect girls from all forms of harassment must be implemented immediately.

Author disclosure

The authors of this paper have no competing research or financial interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for funding this study and the project partner, Operation Asha, in India.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Suchi Bansal

Suchi Bansal, MPH is the Senior Research Specialist at Ci3 at the University of Chicago. Bansal researches adolescent sexual and reproductive health issues in South and South East Asia and has authored several publications on gender disparities and sexual and reproductive health outcomes in the regions. Bansal completed her MPH from Columbia University and her Bachelor's degree in Economics and International Relations from Knox College.

Ellen McCammon

Ellen McCammon, MPH is the Research Specialist II at Ci3 at the University of Chicago. McCammon conducts research on games, storytelling, and adolescent health in the U.S. and other countries. McCammon completed her MPH from Columbia University and her bachelor's degree in Folkore and Mythology from Harvard University.

Luciana E. Hebert

Luciana E. Hebert, PhD is an Assistant Research Professor at the Institute for Research and Education to Advance Community Health (IREACH) and the Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine at Washington State University. Previously, Hebert was the Senior Research Specialist at Ci3 at the University of Chicago. She is an adolescent and women’s health researcher with expertise in family planning, maternal and child health, and sexual and reproductive health. She has formal training in demography and expertise in qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis.

Shirley Yan

Shirley Yan, MPH is the Behavior Change Research Manager at Noora Health. Previously, Yan was the Project Manager of Kissa Kahani at Ci3 at the University of Chicago. With experience working in India, Guyana, and the U.S., Yan leverages health health theories to develop services and programs that people want and work.

Crystal Tyler

Crystal Tyler, PhD, MPH is the Executive Director of Ci3 at the University of Chicago, a research center addressing the social and structural determinants of adolescent sexual and reproductive health through design, narrative, play, and policy change. Dr. Tyler has published on topics such as contraceptive safety and use, adolescent sexual and reproductive health, reproductive cancers, birth defects, and infant mortality. Dr. Tyler completed both her PhD and MPH in Epidemiology, at Michigan State and the University of Michigan, respectively, and her Bachelor’s degree in Women’s Studies at Spelman College.

Alicia Menendez

Alicia Menendez, Phd is a Research Associate Professor at the University of Chicago, Harris School of Public Policy and Principal Research Scientist at NORC at the University of Chicago. Dr. Menendez is an economist with more than 20 years of experience conducting evaluation research in education, health, labor markets, and household behavior in developing countries. She has designed and managed numerous experimental and quasi-experimental impact evaluations and overseen surveys with large data collection teams. Dr. Menendez currently serves as the Principal Investigator on USAID’s Reading and Access Evaluation Projects, evaluating impact and cost-effectiveness of USAID-funded projects aimed at improving reading, and at increasing equitable access to education in fragile and conflict-affected environments in over 10 countries. She is also the Impact Evaluation Director of the USAID/Uganda Performance and Impact Evaluation of Literacy Achievement and Retention Activity (LARA) which focuses on literacy and school-related gender-based violence (SRGBV).

Melissa Gilliam

Melissa Gilliam, MD, MPH is Professor of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Pediatrics, founder and director of Ci3, co-PI of the Game Changer Chicago (GCC) Design Lab, and Dean for Diversity and Inclusion of The University of Chicago Medicine and Biological Sciences Division. Dr. Gilliam conducts qualitative and quantitative research and develops innovative interventions to study health outcomes. Her work began by addressing teenage pregnancy, believing it was a critical barrier to academic success for urban youth of color. Yet as teen pregnancy rates have reached their lowest level in decades, clear disparities have persisted due to other limiting factors, from economic to educational to community barriers. Dr. Gilliam thus founded Ci3, the GCC Design Lab, South Side Stories, and now Story Lab to leverage the vast technological and academic resources that can be brought to bear on the more distal antecedents to poor sexual and reproductive health. She has created a host of summer programs, digital storytelling, and game-based learning experiences that attract large cohorts of urban youth of color. In her work with the Section, she has overseen clinical trials, qualitative research, patient care, and a digital media contraceptive choice intervention successfully piloted in the waiting room.

References

- Abraham, L. (2002). Bhai-behen, true love, time pass: Friendships and sexual partnerships among youth in an Indian metropolis. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 4(3), 337–353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050110120794

- Akhtar, C. (2013). Eve teasing as a form of violence against women: A case study of District Srinagar, Kashmir. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 5(5), 168–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5897/IJSA2013.0445

- Alexander, M., Garda, L., Kanade, S., Jejeebhoy, S., & Ganatra, B. (2006). Romance and sex: Pre-marital partnership formation among young women and men, Pune district, India. Reproductive Health Matters, 14(28), 144–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28265-X

- Banda, P. C., Odimegwu, C. O., Ntoimo, L. F., & Muchiri, E. (2017). Women at risk: Gender inequality and maternal health. Women & Health, 57(4), 405–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2016.1170092

- Barker, G., Ricardo, C., Nascimento, M., Olukoya, A., & Santos, C. (2010). Questioning gender norms with men to improve health outcomes: Evidence of impact. Global Public Health, 5(5), 539–553. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17441690902942464

- Bassett, R., Beagan, B. L., Ristovski-Slijepcevic, S., & Chapman, G. E. (2008). Tough teens: The methodological challenges of interviewing teenagers as research participants. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23(2), 119–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558407310733

- Basu, S., Zuo, X., Lou, C., Acharya, R., & Lundgren, R. (2017). Learning to be gendered: Gender socialization in early adolescence among urban poor in Delhi, India, and Shanghai, China. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4, Suppl.), S24–S29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.03.012

- Betts, L., Harding, R., Peart, S., Sjolin Knight, C., Wright, D., & Newbold, K. (2018). Adolescents’ experiences of street harassment: Creating a typology and assessing the emotional impact. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 11(1), 38-46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JACPR-12-2017-0336

- Bhatla, N., Achyut, P., Ghosh, S., Gautam, A., & Verma, R. (2013). Safe Cities Free From Violence Against Women and Girls: Baseline Finding from the “Safe Cities Delhi Programme”.

- Bhattacharyya, R. (2016). Street violence against women in India: Mapping prevention strategies. Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 10(3), 311–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/aswp.12099

- Bochennek, K., Wittekindt, B., Zimmermann, S. Y., & Klingebiel, T. (2007). More than mere games: A review of card and board games for medical education. Medical Teacher, 29(9–10), 941–948. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701749813

- Borkar, G. (2017). Safety first: Perceived risk of street harassment and educational choices of women (Job Market Paper). Department of Economics, Brown University.

- Census of India and United Nations Population Fund- India. (2011). A profile of adolescents and youth in India. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India.

- Chakraborty, K. (2016). Eve-teasing and education mobility: Young women’s experiences in the Urban Slums of India. Identities and Subjectivities, 4, 269–292. Geographies of Children and Young People, Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-023-0_12

- Davidson, M. M., Butchko, M. S., Robbins, K., Sherd, L. W., & Gervais, S. J. (2016). The mediating role of perceived safety on street harassment and anxiety. Psychology of Violence, 6(4), 553–561. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039970

- de Freitas, S. (2018). Are games effective learning tools? A review of educational games. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 21(2), 74–84. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26388380

- Drew, S. E., Duncan, R. E., & Sawyer, S. M. (2010). Visual storytelling: A beneficial but challenging method for health research with young people. Qualitative Health Research, 20(12), 1677–1688. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310377455

- Elmir, R., Schmied, V., Jackson, D., & Wilkes, L. (2011). Interviewing people about potentially sensitive topics. Nurse Researcher, 19(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2011.10.19.1.12.c8766

- Flanagan, S. M., Greenfield, S., Coad, J., & Neilson, S. (2015). An exploration of the data collection methods utilised with children, teenagers and young people (CTYPs). BMC Research Notes, 8, 61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1018-y

- Halder, D., & Jaisankar, K. (2010). Cyber victimization in India: A baseline survey report Tamil Nadu. Center for Cyber Victim Counselling.

- Halder, D., & Jaishankar, K. (2013). Use and Misuse of Internet by Semi-Urban and Rural Youth in India: A Baseline Survey Report Centre for Cyber victim counselling. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1759708

- Hindin, J., & Hindin, M. (2009). Premarital romantic partnerships: Attitudes and sexual experiences of youth in Delhi, India. International Family Planning Perspectives, 35(2), 97–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1363/3509709

- International Institute for Population Sciences. (2017). National Family Health Survey- 4 2015-16, State Fact Sheet: Uttar Pradesh. M. o. H. a. F. Welfare. Mumbia, India: International Institute for Population Sciences.

- Kagesten, A., Gibbs, S., Blum, R. W., Moreau, C., Chandra-Mouli, V., Herbert, A., & Amin, A. (2016). Understanding factors that shape gender attitudes in early adolescence globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS One, 11(6), e0157805. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157805

- Long, J. L., Caruso, B. A., Mamani, M., Camacho, G., Vancraeynest, K., & Freezman, M. C. (2015). Developing games as a qualitative method for researching menstrual hygiene management in rural Bolivia. Waterlines, 34(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3362/1756-3488.2015.007

- Maclachlan, M., Chimombo, M., & Mpemba, N. (1997). AIDS education for youth through active learning: A school-based approach from Malawi. International Journal of Educational Development, 17(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-0593(96)00013-2

- Mmari, K., Blum, R. W., Atnafou, R., Chilet, E., de Meyer, S., El-Gibaly, O., Basu, S., Bello, B., Maina, B., & Zuo, X. (2017). Exploration of gender norms and socialization among early adolescents: The use of qualitative methods for the global early adolescent study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4), S12–S18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.07.006

- Morgan, R., Tetui, M., Muhumuza Kananura, R., Ekirapa-Kiracho, E., & George, A. S. (2017). Gender dynamics affecting maternal health and health care access and use in Uganda. Health Policy and Planning, 32(suppl_5), v13–v21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx011

- Morris, J. L., & Rushwan, H. (2015). Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: The global challenges. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 131(Suppl 1), S40–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.02.006

- Nahar, P., van Reeuwijk, M., & Reis, R. (2013). Contextualising sexual harassment of adolescent girls in Bangladesh. Reproductive Health Matters, 21(41), 78–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41696-8

- Namasivayam, A., Osuorah, D. C., Syed, R., & Antai, D. (2012). The role of gender inequities in women’s access to reproductive health care: A population-level study of Namibia, Kenya, Nepal, and India. International Journal of Women’s Health, 4, 351–364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S32569

- Nanda, P., Gautam, A., Verma, R., Khanna, A., Khan, N., Brahme, D., Boyle, S., & Kumar, S. (2014). Study on masculinity, intimate partner violence and son preference in India. International Center for Research on Women. https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Masculinity-Book_Inside_final_6th-Nov.pdf

- Peitzmeier, S. M., Kagesten, A., Acharya, R., Cheng, Y., Delany-Moretlwe, S., Olumide, A., Blum, R. W., Sonenstein, F., & Decker, M. R. (2016). Intimate partner violence perpetration among adolescent males in disadvantaged neighborhoods globally. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(6), 696–702. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.019

- Rahman, M., Nakamura, K., Seino, K., & Kizuki, M. (2013). Does gender inequity increase the risk of intimate partner violence among women? Evidence from a national Bangladeshi sample. PLoS One, 8(12), e82423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082423

- Reissman, K. C. (1993). Narrative Analysis. SAGE.

- Saha, T., & Srivastava, A. (2014). Indian women at risk in the cyber space: A conceptual model of reasons of victimization. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 8(1), 57–67. http://www.cybercrimejournal.com/sahasrivastavatalijcc2014vol8issue1.pdf

- Santhya, K. G., Acharya, R., Jejeebhoy, S. J., & Ram, U. (2011). Timing of first sex before marriage and its correlates: Evidence from India. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 13(3), 327–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2010.534819

- Talboys, S. L., Kaur, M., VanDerslice, J., Gren, L. H., Bhattacharya, H., & Alder, S. C. (2017). What is eve teasing? A mixed methods study of sexual harassment of young women in the rural indian context. SAGE Open, 7(1), 2158244017697168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017697168

- Tilbury, F., Gallegos, D., Abernethie, L., & Dziurawiec, S. (2008). ‘Sperm milkshakes with poo sprinkles’: The challenges of identifying family meals practices through an online survey with adolescents. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(5), 469–481. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570701622140

- Tripathi, K., Borrion, H., & Belur, J. (2017). Sexual harassment of students on public transport: An exploratory study in Lucknow, India. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 19(3), 240–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-017-0029-0

- Umarhathab, S., Raj Rao, G. D., & Jaisankar, K. (2009). Cyber crimes in India: A study of emerging patterns of perpetration and victimization in Chennai City. Pakistan Journal of Criminology, 1(1), 51–67. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.477.3981&rep=rep1&type=pdf#page=61

- UN General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. United Nations.

- Welfare, M. O. H. F. (2014). Rashtriya Swasthya Kishor Karyakaram. Retrieved January 18, 2019, from http://nhm.gov.in/rashtriya-kishor-swasthya-karyakram.html.

- World Bank. (2016). India state briefs.

- Yeatman, S., & Trinitapoli, J. (2011). Best-friend reports: A tool for measuring the prevalence of sensitive behaviors. American Journal of Public Health, 101(9), 1666–1667. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300194

- Yonekura, T., & Soares, C. B. (2010). The educative game as a sensitization strategy for the collection of data with adolescents. Revista Latino-americana De Enfermagem, 18(5), 968–974. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692010000500018