ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to investigate the main effect and moderating effect of intergroup behaviours on the relationship between daily life stressors and emotional symptoms. Data was collected from 628 school going adolescents using the Daily Life Stressor Scale, emotional symptom subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Behaviours from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes - Treatment scale. Data showed that emotional symptoms and daily life stressors were common especially among girls. Daily life stressors, active harm and passive facilitation predicted increased emotional symptoms. However, contrary to the study hypothesis, active and passive harm, and active and passive facilitation did not moderate the relationship between daily life stressors and emotional symptoms. School based interventions focusing on reducing academic and interpersonal related daily life stressors should be considered in order to reduce emotional symptoms and improved wellbeing among school going adolescents.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO)’s definition of health includes mental and psychosocial wellbeing. According to WHO, mental health conditions account for 16% of the global burden of disease and injury in people aged 10–19 years (WHO, Citation2019a). Against this backdrop, world leaders through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), have committed to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. Specifically, Target 3.4 spells-out that by 2030, countries should reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention, treatment and promotion of mental health and well-being (WHO, Citation2019b; Dybdahl & Lien, Citation2017). In addition, more than one-third of SDGs targets reference young people explicitly or implicitly, with a focus on empowerment, participation and/or well-being (Bokoyeibo, Citation2018). Lack of empowerment, quality participation and good well-being are a source of stress and a precursor of different emotional problems among young people.

Emotional symptoms and stress

Emotional symptoms are common particularly among school-going adolescents (Sears & Milburn, Citation1990; Verma, Sharma & Larson, 2002; Sripongwiwat, Bunsterm & Tang, 2018) are a source of poor well-being among adolescents. For instance, in Zambia the setting for the current study, 16.3% of school-going adolescents without any clinical conditions reported severe depressive symptoms (Hapunda et al., Citation2015) and in Egypt 14.2% reported depressive symptoms among students attending high school (Ekundayo et al., Citation2007) compared to 17.2% among adolescents in the UAE (Shah et al., Citation2020). Emotional disorders as measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) has been documented in Africa also. For instance, 2% of 6–12-year old Egyptians reported emotional symptoms (Elhamid, Howe, & Reading, Citation2009) while in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the mean score for the emotional scale (somatic complaints, worries, unhappy, clingy and fears) on the SDQ was 2.6 ± 2.2 for boys and 2.4 ± 2.2. for girls as rated by teachers (Kashala et al., Citation2005, Citation2006). Elsewhere, girls than boys tend to report more emotional symptoms (Ha, et al., 2019; Mosksnes, Espness & Haugan, 2013). Further, reduced capacity to down regulate emotions heightens negative effects common to both anxiety and depression among young people (Young et al., Citation2019).

There are several factors that predispose adolescents to emotional symptoms including those related to school (e.g. bullying and victimization by peers, problems with teachers and academic difficulties, negative classroom climate etc.,) and interpersonal relationships (e.g. conflicts or problems with parents, peers and siblings etc.,), social class (Meilstrup et al., Citation2015; Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, Citation2008), discrimination and stigma especially in countries with high sexual abuse, HIV and orphanhood like Zambia. These factors are collectively called stressors. Krohne (Citation2002) argues that external forces that impinge on one’s body are stressors. Predominantly, daily life stressors have greater impact than major life events on individuals particularly adolescent’s quality of life because these events are more frequent, psychologically proximal and predict present and future psychological symptoms (Kearney et al., Citation1993). Stress can trigger emotional reactions but emotional symptoms can also be a source of stress. Thus, there is a bidirectional relationship between stress and emotional symptoms.

Intergroup behaviour and emotional symptoms

The relationship between stress and emotional symptoms may be buffered or exacerbated by intergroup behaviours (Gunnar, Citation2017; Hostinar et al., Citation2014) depending on the nature and degree of the intergroup behaviour. Intergroup relations refer to the way in which people who belong to social groups or categories perceive, think about, feel about, and act towards and interact with people in other groups (Hogg, Citation2013). These interactions can be positive or negative. For instance, adolescents’ perception of peer prejudice at school is associated with feeling of alienation and unhappy at school (Benner et al., Citation2015). The work of Sibley (Citation2011) and Cuddly et al. (Citation2007) discusses subjective frequencies of different classes of harm and facilitating behaviours that people encounter in their day to day intergroup relations. They categorize intergroup prejudice into dimensions – directiveness (active vs. passive) and outcomes (harm vs. facilitation). Thus, their work identified four different ways of acting towards or treating people based on their perceived group membership – active harm, passive harm, active facilitation and passive facilitation. Cuddly et al. (Citation2007) defines active harm as representing those behaviours that are intentionally directed towards an outgroup and its members with the goal of harming or otherwise causing damage or negative experience and consequences. It includes behaviours such as attacking, threatening, fighting with or making others feel unsafe (Sibley, Citation2011). On the other hand, passive harm is defined as reflecting classes of behaviour where one demeans or distances other groups by diminishing their social worth through excluding, ignoring or neglecting. Both passive and active harm has been documented to have negative outcomes such a depression, binge eating, smoking, loneliness and others negative emotion reaction such as self harm and suicidal ideation (Garnett et al., Citation2014; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., Citation2016; Mulvey et al., Citation2018; Shin et al., Citation2011; Striegel-Moore et al., Citation2002). Passive facilitation is defined as reflecting classes of behaviours that are proactive to help or aid members of an outgroup in reaching their goals (Cuddly et al., Citation2007). This involves protecting members of the outgroup, and thus help them achieve goals of safety and security, as well as more overt desires related to sharing the behaviour or other people to enact desired behaviour, as well as inhibit undesired behaviour (Sibley, Citation2011). The work of Brewer (Citation2007) also highlights the importance of ingroups relations in promoting security and survival. The author argues that security and survival depend on inclusion in stable, clearly differentiated social groups which promote comradeship, independence and cooperation without which humans cannot survive outgroups (Brewer, Citation2007). On the other hand, passive facilitation is defined as reflecting a class of behaviour, where one acts with outgroups members to achieve one’s own goals and in such cases accept obligatory association or convenient cooperation with a group (Sibley 2010; Cuddly et al., Citation2007). Such actions are meant to save one’s goals especially a good public reputation or perception. As such, Allport (Citation1954) argued that intergroups can only have positive effects when individuals have equal status, common goals, cooperation and support from authority and customs.

Therefore, active and passive harm behaviours could exacerbate emotional symptoms while active and passive facilitation could buffer emotional symptoms depending on their directiveness and outcomes.

The stress transactional framework

Emotional problems can be draining and a source of stress. Conversely, a stressor can also cause different emotional reactions (Krohne, Citation2002). Stress is caused by perceived aversive environmental stimuli. Therefore, stress is a transaction between the person and the environment that a person evaluates as significant to his/her wellbeing (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1986). According to Lazarus (Citation1999 see also Matthieu & Ivanoff, Citation2006) transaction is when an individual’s cognitive focus is on the relationship between the person and the environment, such as thinking about events in one’s life and deciding if one has the personal resources to handle those threat evoking events. Thus, for an external force such as treatment bias (support, care, discrimination, victimization, bullying etc.,) to be considered a buffer or exacerbator of stress or emotional symptoms, therefore a threat, an individual has to appraise it as such (Krohne, Citation2002). Appraisal is an individual’s evaluation of the significance of what is happening for their wellbeing and in which the demands tax or exceed available coping resources (Krohne, Citation2002; Lazarus, Citation1993). Coping is the individual’s effort in thought and action to manage specific demands also known as stressors (Lazarus, Citation1991).

Thus, from the definition of stress, three processes/reactions – cognitive appraisal, coping and perception are central moderating variables (Krohne, Citation2002; Lazarus, Citation1999). The later is dependant on actual expectancies that persons manifests with regards to the significance and outcome of a specific encounter (Krohne, Citation2002; Lazarus, Citation1991). The interpretation of a psychosocial stressor such as treatment bias determine the magnitude of a stressor, the emotions generated and how a person will respond (Matthieu & Ivanoff, Citation2006). Therefore, stress may or may not be perceived as stressful or harmful by every individual. Based on one’s cognitive appraisal, a stressor is perceived hazardous to one’s wellbeing if the duration and magnitudes evoke different negative emotional symptoms. These vary on a continuum from pleasantness – unpleasantness, tense-relaxation and excitement to calm. The degree to which the emotional response reflects these dimensions, depends also on how a person appraises a changing relationship with the environment (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Thus, we can argue that the appraisal of intergroup behaviours can moderate (buffer or exacerbates) the relationship between stress and emotional symptoms.

The aim of the study was to investigate the main effect and moderating effect of intergroup behaviours on the relationship between daily life stressors and emotional symptoms. The study hypothesized that the relationship between emotional symptoms and daily life stressors is moderated by directiveness (active vs. passive) and outcomes (harm vs facilitation) of intergroup behaviours. More specifically, the study hypothesized that increased daily life stressors will predict increased emotional symptoms in the main effect. Further, this relationship will be exacerbated by the moderating effect of active and passive harm, and passive facilitation while active facilitation will act as a buffer for the relationship between daily life stressors and emotional symptoms.

Methods

Participants

The sample composed of 628 secondary school pupils in grade 10–12 in Lusaka, the capital city of Zambia. Of the 628 pupils, 323 (51%) were male. The average age was 16.94 ± 1.26 and majority were in grade 11(11.33 ± 0.62). The distribution of mothers’ education for these adolescents was 10.5% primary education, 16.9% secondary education and 72.6% tertiary education. For fathers, 8.4% had primary education, 57.9 secondary education and 33.7% secondary education. In addition, 71.4% of these adolescents lived with their parents in a household with an average 6.13 ± 2.13 family members. has details of the sample demographics.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics the participants

Measures

Emotional symptoms: – A subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire was used to measure emotional symptoms. The SDQ is used as a behavioural screening tool and it is relatively short allowing for rapid administration, measures both mental health difficulties and competencies. It has five subscales – conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, emotional symptoms, peer problems, and prosocial behaviour. It consists of 25 items to assess a range of ‘strengths’ and ‘difficulties’ as behavioural markers of potential mental health problems. The items contribute to the five subscales (Goodman, Citation1997). In Africa, the SDQ has demonstrated poor psychometric properties with only about 14.5% of studies only using subscales with good psychometric properties (Hoosen et al., Citation2018). In the current study, the emotional subscale was the only one with relatively good internal consistency of 0.66 as measured by Cronbach Alpha. In other African countries it has ranged between 0.66 and 0.73 overall and on subscales (Hoosen et al., Citation2018). The emotional symptom self-report subscale of the SDQ contains 5 items each with a minimum score of 0 (lowest score) to 10 (highest score). The five emotional items are measured on a 3-point scale:0 ‘not true’, 1 ‘somewhat true’ and 2 ‘certainly true’. The items measures somatic complaints, worries, unhappiness, clingy and fears.

Daily Life Stressor Scale (DLSS): – The DLSS is a 30-item measure designed to assess the severity of everyday stressful life events and aversive arousal encountered by persons above the aged of 7. The scale measures only the severity of negative daily life events and negative affective within the past week. Items are self-rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 0 to 4, with 0 being ‘not at all stressful,’ 1 being ‘a little stressful,’ 2 being ‘some stressful,’ 3 being ‘a lot stressful,’ and 4 being ‘very much stressful.’ Persons are asked to rate each item, after which a total score (from 0 to 120) is computed. Higher scores represent greater stress in current day-to-day situations. If an event did not occur for that day (e.g. doing homework on a Sunday), then a zero would be recorded. It has a moderate but significant test–retest reliability over a period of one week (Kearney et al., Citation1993). In the current study, Cronbach Alpha was good at 0.86.

Behaviours from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes – Treatment scale (BIAS-TS): – the BIAS-TS is a 32-item questionnaire that assesses the subjective frequency of different classes of harm and facilitation behaviour that people encounter in their day to day lives. It has four subscales with 8 items each with a minimum score of 1 and maximum of 56. A higher score means increased experience of subjective behaviour. These subjective behaviours include active harm, passive harm, active facilitation and passive facilitation. The BIAS–TS was derived from the Behaviours from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes (BIAS) Map (Cuddly et al., Citation2007), and provides reliable, replicable, and stable indexes of different harmful and facilitatory behaviours that people encounter in their day-to-day lives from multiple sources (Sibley, Citation2011). In the current study, Cronbach alpha was 0. 82 for the overall scale, 0.78 for the Active harm scale, 0.70 for the Passive harm; 0.79 for Active facilitation and 0.74 for Passive facilitation subscale.

Data analysis

First descriptive statistics including proportions, means and standard deviations were computed on demographic characteristics and our three main variables (emotional symptoms, daily life stressors and intergroup behaviours) in order to understand the pattern of their manifestation in our sample. The main analysis was moderation analysis in SPSS using the add-on Process version 3.4 by Andrew Hayes in Regression. The main effect and moderating effects were conducted with daily life stressors as a predictor variable and emotional symptoms as the outcome variable. The moderating variables were 4 subscales of the BIAS-TS – active harm, passive harm, active facilitation and passive harm. The variables were standardized as Z score before conducting our main analysis. Analysis was done in IBM SPSS version 23.

Results

General findings

The mean for emotional symptoms was 2.87 ± 2.45. There was a statistically significant difference in emotional symptoms between boys (3.11 ± 2.12 and girls (4.68 ± 2.52). In terms of daily life stressor, the mean score was 27.66 ± 16.81. There was also a statistically significant difference in experiencing daily life stressor between boys (25.45 ± 16.96) and girls (30 ± 17.38). With regards to intergroup subjective treatment/behaviour, the mean was 17.42 ± 9.16 for active harm, 27.70 ± 10.32 for passive harm, 35.65 ± 11.32 for active facilitation and 23.78 ± 10.11 for passive facilitation. On all the 4 subscale the difference between boys and girls were not statistically significant. For details see .

Table 2. Psychological outcomes means for boys and girls

Further analysis was conducted for emotional symptoms at item level. The mean scores ranged from 0.58 to 1.10 across the five symptoms. The highest experienced emotional symptoms (i.e. endorsed as ‘certainly true’) were worry (32%) and clingy/nervous (27%). There was a statistically significant difference between boys and girls on all the five items. See for details.

Table 3. Specific emotional symptoms and daily life stressors disaggregated by sex

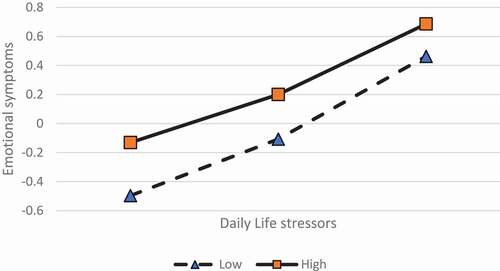

Relationship between daily life stressors and emotional symptoms as moderated by active harm

In step one, the hypothesis – increased daily life stressors will be associated with increased emotional symptoms and active harm will exacerbate this relationship was test. In model 1, data in the basic relationship showed that increased daily life stressors was associated with increased emotional symptoms (β = 0.44, P < 0.001). Further increased active harm was associated with increased emotional symptoms (β = 0.44, P < 0.05). Finally, the interaction term yielded a non-significant beta in predicting emotional symptoms (β = 0.44, P > 0.05). This finding is contrary to our hypothesis therefore we accept the null hypothesis. In Model 2, demographic characteristics were added as covariates to the model. In Model 2, even after controlling for demographic characteristic, daily life stressors (β = 0.44, P < 0.001) and active harm (β = 0.31, P < 0.01) remained significant predicators of emotional stress. Finally, the interaction term yielded a non-significant beta in predicting emotional symptoms. This was further confirmed by the interaction graph. This data is shown in and . Therefore, contrary to the study prediction, the null hypothesis was accepted for the moderation effect. Of the three covariates, only being female was associated with increased emotional symptoms

Table 4. Relationship between daily life stressors & emotional symptoms as moderated by intergroup subjective behaviours

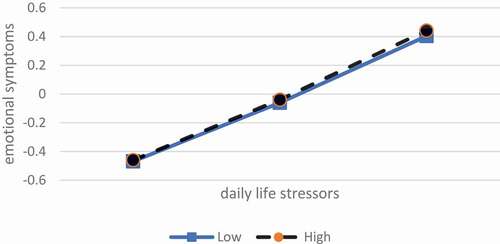

The association between daily life stressor and emotional symptoms as moderated by passive harm

In step two, the hypothesis – increased daily life stressors will be associated with increased emotional symptoms and that this relationship will be exacerbated by increased passive harm was tested. In model 1, data in the basic relationship showed that increased daily life stressor was associated with increased emotional symptoms (β = 0.48, P < 0.001). However, the relationship between passive harm and emotional symptoms was not statistically significant so was the interaction effect. This relationship remained nonsignificant even after covariates were considered. Of the three covariates, only being female was associated with increased emotional symptoms (β = 0.25, P < 0.001). See and for details of the moderation effect. Therefore, contrary to the study prediction, the null hypothesis was accepted for the moderation effect.

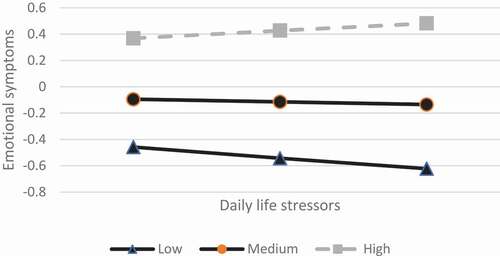

The Association between Daily Life Stressor and Emotional Symptoms as moderated by Active Facilitation

In step three, the hypothesis – increased daily life stressor will be associated with increased emotional symptoms but buffered by increased active facilitation was tested. In model 1, data in the basic relationship showed that increased daily life stressor was associated with increased emotional symptoms (β = 0.49, P < 0.001). The moderator variable (active facilitation) was not a significant predictor (β = 0.01, P > 0.05) and the interaction effect was not significant ((β = 0.06, P > 0.05). In model 2, covariates were introduced to the model. However, only the basic relationship remained significant (β = 0.48, P < 0.001). Of the three covariates, only being female was associated with increased emotional symptoms. See and for details of the moderation effect. Therefore, contrary to our prediction, the null hypothesis was accepted for the moderation effect.

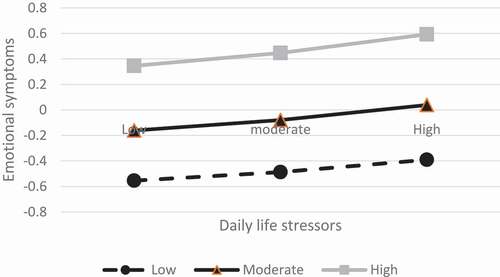

The association between Daily Life Stressor and Emotional Symptoms as moderated by passive facilitation

In step four, the hypothesis – increased daily life stressor will be associated with increased emotional symptoms but exacerbated by increased passive facilitation was tested. In model 1, data in the basic relationship showed that increased daily life stressors were associated with increased emotional symptoms (β = 0.45, P < 0.001) and increased passive facilitation was associated with increased emotional symptoms (β = 0.11, P < 0.05). However, the interaction term yielded a non-significant prediction of emotional symptoms. In model 2, covariates were introduced to the model. Data in the basic relationship showed that increased daily life stressor was associated with increased emotional symptoms (β = 0.43, P < 0.001), but this time the relationship between passive facilitation and emotional symptoms was not significant (β = 0.09, P > 0.05. The interaction term was also not a significant predictor of emotional symptoms. In model 2, none of the covariates were significant predictors of emotional symptoms. Therefore, contrary to the study prediction, the null hypothesis was accepted for the moderation effect. For details see and .

Discussion

The aim of the study was to investigate the main effect and moderating effect of intergroup behaviour on the relationship between daily life stressors and emotional symptoms among school-going adolescents. Generally, the scores on daily life stressor(s) and emotional symptoms were low among adolescents suggesting these two psychological factors were not very much prevalent among this group. However, girls than boys reported high daily life stressors and emotional symptoms. This is consistent with findings by Kearney and colleagues (Kearney et al., Citation1993) in the USA and by Sripongwiwat, Bunstren & Tang (2018) in Thailand. In addition to school and interpersonal stressors, girls than boys tend to experience addition stressors related to household chores and responsibilities such as sibling care (Mooya, Citation2015) in the Zambian context. Data at item level showed that the percentage of girls who reported household responsibilities as daily life stressors was higher than boys. At a general level, most daily life stressors were academic and interpersonal related. In addition, adolescents’ experiences of subjective intergroup behaviours of active harm, passive harm and passive facilitation were relatively low among adolescents. However, active facilitation was reported to be common among adolescents. This result suggests that the majority of adolescents in this study perceived to have been getting help or aid from other members of an outgroup to reach their goals.

As hypothesized, the basic relationship between daily life stressor and emotional symptoms was significant. It was observed that increased daily life stressors were associated with increased emotional symptoms. As observed by Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner (Citation2008) and Friso and Eggermont (Citation2015), stress is linked to mental health and behavioural problems. Stressful situations and life events produce harmful stressful outcomes such as emotional symptoms and depression (Signfusdottir et al., Citation2017). Feeling lonely, for example, is linked to social stress (Van Roekal et al., Citation2015). Adolescents in this study showed indicators of loneliness with 23% finding it hard to talk about personal things and to get out with friend, respectively. Overall, adolescents in this study experienced significant emotional symptoms compared to (2.6 ± 2.2 for boys and 2.4± for girls) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Kashala et al., Citation2005, Citation2006). The difference is that the current study focused on adolescents while the DRC study focused on children between 7–12 years old. This finding was not surprising given that it is well-established that adolescence is a period of ‘stress and storm’ compared to any other period of human development.

Active harm and passive facilitation were also found to be significant predictors of emotional symptoms among adolescents. It was expected that feeling or perceiving behaviours of others as intentionally directed towards attacking, threatening or making one feel unsafe (active harm) would cause emotional symptoms (Hong et al., Citation2019; Perren et al., Citation2010). Similarly, perceiving acts of others as crafted to achieve their own goals and not a person in need can be emotional provoking therefore stressful and a trigger of emotional symptoms because of the demeaning face such behaviours tend came with. According to Sibley (Citation2011), benevolent or paternalistic forms of prejudice position the target group as warm and likeable but weak and incompetent, and therefore as deserving of and needing protection from others who know what is best. When such actions are internalized and become part of the person’s internal working model, their behaviour communicates weakness, incompetence and vulnerability. This could perhaps explain why 23% of adolescents said ‘hard to talk about personal things’ was stressful. Taking about personal things can sometimes be misunderstood as being week and deserving help. However, passive harm and active facilitation were not associated with emotional symptoms. It remains unclear why the two did not predict emotional symptoms. Specifically, active facilitation was expected to predict reduced emotional symptoms because of the supportive and caring facets underlying this subscale of BIAS-TS.

Contrary to the study hypothesis, none of the four sub-scales of the BIAS-TS moderated the relationship between daily life stressors and emotional symptoms. It could be that daily life stressors are too aversive therefore the effect of subjective intergroup behaviour (active harm, passive harm, and passive facilitation) have little influence to buffer or exacerbate emotional symptoms. Most importantly, cognitive appraisal and perception of these subjective intergroup behaviours could have not been experienced for a long duration and intensity as suggested by the relatively low mean scores, therefore appraised as less threatening by the adolescents. Therefore, future research should consider duration and intensity of exposure to these subjective behaviours. Further, passive facilitation was common but below the average of the total score for each subscale. This may suggest active facilitation was not adequate enough to buffer emotional symptoms as a result of daily life stressors.

This study has limitations. First, we only used one subscale of the SDQ due to the poor psychometric properties of other subscales. Secondly, we used self-report measures that suffer from response bias. Despite these limitations, to the best of the researcher's knowledge this is the first study to measure emotional symptoms using the SDQ on a non-clinical sample in Zambia. Further, the study assessed moderation in order to identify whether subjective behaviours exacerbates or buffer emotional stress in this sample. Therefore, the study rules out the influence of intergroup behaviours on the association of daily life stressor and emotional symptoms in school-going adolescents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, emotional symptoms and daily life stressors were common in the Zambian sample of adolescents. Daily life stressor, active harm and passive facilitation predict emotional symptoms in adolescents. However, active harm, passive harm, active and passive facilitation do not moderate the relationship between daily life stressors and emotional symptoms in school-going adolescents. Consistent with other studies (Ha, et al., 2019; Mosksnes, Espness & Haugan, 2013), being a girl than being a boy was associated with increased emotional symptoms perhaps because of the additional responsibilities that girls have at home compared to boys. Therefore, school-based interventions that consider daily life stressors such as academic activities and interpersonal relationships should be considered to improve the wellbeing quality of life of adolescents.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Given Hapunda

Given Hapunda is a lecturer and researcher of psychology at the University of Zambia, in Zambia. His research for the last 11 years is around emotional regulation and adjustment, child and adolescent health, programme evaluation and parenting outcomes. He is an active member of the International Society for the Study of Behavioural Development (ISSBD) where he is currently saving as the early career scholars representative. He is also a member of the regional research technical team of the Africa Early Childhood Network (AfECN).

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

- Benner, A. D., Crosnoe, R., & Eccles, J. S. (2015). Schools, peers and prejudice in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25(1), 173–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12106

- Bokoyeibo, A. (2018). Youth and sustainable development goals. Atlas Corps. https://atlascorps.org/youth-and-the-sustainable-development-goals/on 3 April, 2020.

- Brewer, M. B. (2007). The importance of being we: Human nature and intergroup relations. American Psychologist, 62(8), 728–738. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.62.8.728

- Cuddly, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2007). Behaviours from intergroup affect and stereotypes: The BIAS maps. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 631–648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631

- Dybdahl, R., & Lien, L. (2017). Mental health is an integral part of the sustainable development goals. Prev Med Commun Health, 1(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15761/PMCH.1000104

- Ekundayo, O., Dodson-Stalworth, J., Roofe, M., Aban, I. B., Kempf, M. C., Ehiri, J. E., & Jolly, P. E. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among high school students in Hanover, Jamaica. The Scientific World Journal, 7, 567–576. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.100/tsw.2007.104

- Elhamid, A.A., Howe, A., & Reading, R.(2009). Prevalence of emotional and behavioural programmes among 6–12 year old children in Egypt. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.007/s00127-008-0394–1

- Friso, E., & Eggermont, S. (2015). The impact of daily stress on adolescents depressed mood: The role of social support seeking through Facebook. Computers in Human Behaviour, 44, 315–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.070

- Garnett, B. R., Masyn, K. E., Austin, S. B., Miller, M., Williams, D. R., & Viswanath, K. (2014). The intersectionality of discrimination attributes and bullying among youths: An applied latent class analysis. Journal of Youths and Adolescence, 43(8), 1225–1239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0073-8

- Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38(5), 581–586. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

- Gunnar, M. R. (2017). Social buffering of stress in development: A career perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(3), 355–373. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616680612

- Hapunda, G., Abubakar, A., Pouwer, F., & Van De Vijver, F. (2015). Diabetes mellitus and comorbid depression in Zambia. Diabetic Medicine, 32(6), 814–818. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12645

- Hogg, M. A. (2013). Intergroup relations. In J. DeLamater & A. Ward (Eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 533). Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6772-0_18.

- Hong, J. S., Espelage, D. L., & Rose, C. A. (2019). Bullying, peer victimization, and child and adolescent health: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(9), 2329–2334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01502-9

- Hoosen, N., Davids, E. L., De Vries, P. J., & Shung-King, M. (2018). Strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) in Africa: A scoping review of its application and validation. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 12(6). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0212-1

- Hostinar, C. E., Sullivan, R. M., & Gunnar, M. R. (2014). Psychobiological mechanisms underlying the social buffering of the HPA axis: A review of animal models and human studies across development. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 256–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032671

- Kashala, E., Elgen, I., Sommerfelt, K., & Tylleskar, T. (2005). Teacher ratings of mental health among school children in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 14(4), 208–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-005-0446-y

- Kashala, E., Lundervold, A., Sommerfelt, K., Tylleskar, T., & Elgen, I. (2006). Co-existing symptoms and risk factors among African school children with hyperactivity-inattention symptom in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 15(5), 292–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-006-0536-5

- Kearney, C. A., Drabman, R. S., & Beasley, J. F. (1993). The trails of childhood: The development, reliability and validity of the daily life stress scale. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 2(4), 371–388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01321232

- Krohne, H. W. (2002). Stress and coping theories. International Encyclopaedia of Social Behavioural Sciences, 22, 15163–15170.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1986). Cognitive theories of stress and the issue of circularity. In M. H. Apply & R. Trumbull (Eds.), Dynamics of stress. Physiological, psychological and social perspectives (pp. 63–80). Plenum.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1993). Coping theory and research: Past, present and future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55(3), 245–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199305000-00002

- Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. Springer.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Lorenzo-Blanco, E. I., Unger, J. B., Oshri, A., Baezconde-Garbanati, L., & Soto, D. (2016). Profiles of bullying victimizations, discrimination, social support and school safety: Links with latino/a youth acculturation, gender, depressive symptoms and cigarate use. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000113

- Matthieu, M. M., & Ivanoff, A. (2006). Using stress, appraisal, and coping theories in clinical practice: Assessment of coping strategies after disaster. Brief Treatment and Crisis Interventions, 6(4), 337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/brief.treatment/mhi009

- Meilstrup, C., Ersbøll, A. K., Nielsen, L., Koushede, V., Bendtsen, P., Due, P., & Holstein, B. E. (2015). Emotional symptoms among adolescents: Epidemiological analysis of individual-class and school level factors. European Journal of Public Health, 25(4), 644–649. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv046

- Mooya, H. (2015). Growing up among siblings: Sib care in Zambia. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, 2(8), 570–574.

- Mulvey, K. L., Hoffman, A. J., Gӧnültas, S., Hope, E. L., & Cooper, S. M. (2018). Understanding experiences with bullying and bias-based bullying: What matters and for who? Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 702–711. http://doi:10.1037vio000206

- Perren, S., Dooley, J., Shaw, T., & Cross, D. (2010). Bullying in school and cyberspace: Associations with depressive symptoms in Swiss and Australian adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 4(1), 28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-4-28

- Sears, S. J., & Milburn, J. (1990). School aged stress. In L. E. Arnold (Ed.), childhood stress (pp. 223–246). Wiley.

- Shah, S. M., Al Dhaheri, F., Albonna, A., Al Jaberi, N., Al Eissae, S., Alshehhi, N. A., Al Shamisis, S.A., Al Hamezi, M.M., Abdelraeq, S.Y., Grivna, M., & Betancourt, F.S. (2020). Self-esteem and other risk factors for depressive symptoms among adolescents in United Arab Emirates. Plos ONE, 15(1), e0227483. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227483

- Shin, J. Y., D’Antonio, E., Son, H., Kim, S. A., & Park, Y. (2011). Bullying and discrimination experiences among Korean-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 34(5), 873–883. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.01.004

- Sibley, C. G. (2011). The BIAS-Treatment Scale (BIAS-TS): A measure of subjective experience of active and passive harm and facilitation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(3), 300–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.559389

- Signfusdottir, I. D., Kristjansson, A. L., Thorlindsson, T., & Allegrante, J. P. (2017). Stress and adolescent wellbeing: The need for an interdisciplinary framework. Health Promotion International, 32(6), 1081–1090. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daw038

- Striegel-Moore, R. H., Dohm, F. A., Pike, K. M., Wilfley, D. E., & Fairburn, C. G. (2002). Abuse, bullying and discrimination as risk factors for binge disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(11), 1902–1907. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1902

- Van Roekal, E., Ha, T., Verhagen, M., Kuntsche, E., Scholte, B. H. J., & Engles, R. C. M. E. (2015). Social stress in early adolescents’ daily lives: Associations with affect and loneliness. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 274–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.10.012

- World Health Organisation. (2019a). Adolescent mental health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health 3 April, 2020

- World Health Organisation. (2019b). Mental health. https://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/SDGs/en/on 3 April 2020

- Young, K. S., Sandman, C. F., & Craske, M. G. (2019). Positive and negative emotional regulation in adolescents: Links to anxiety and depression. Brian Science, 9(4), 76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9040076

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Skinner, E. A. (2008). Adolescents coping with stress: Development and diversity. The Prevention Researcher, 1594, 1–5.