?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Studies have showed that being bullied by peers in adolescence is strongly and consistently associated with decreased sense of well-being that may be expressed in emotional, physical and behavioural effects. Yet, there are personal variables that might mediate the relationships between bullying victimization and low levels of well-being. In this study, we have examined the possible moderating effect of resilience and self-concept that were found to be connected to bullying and to well-being among Israeli adolescents. 507 middle school Israeli students, aged 11–16, fulfilled Bullying victimization, well-being, self-concept and resilience questionnaires. A mediation model analysis have revealed that the hypothesized mediation model was accepted in full and both high self-concept and resilience mediates this relationship. Specific directions and recommendation are discussed for further insights into intervention and prevention programmes for adolescents, in order to optimize existing programmes as well as to create an infrastructure for new intervention programs.

Introduction

Bullying victimization among youth

Youth interpersonal violence may be manifested in various ways, for example, severe physical assault, minor physical assault (e.g. punching, kicking), verbal aggression (e.g. yelling, teasing), indirect or relational aggression (e.g. rumour spreading, stealing), and bullying and cyberbullying (V. L. Marsh, Citation2018; Vivolo et al., Citation2011). Most researchers agree that bullying includes not only physical aggression, but also verbal aggression, spreading rumours, social rejection, boycotting, and social isolation, which are repeated over a continuous period of time and include an intention to harm and to cause fear and distress to the bullying victim (Olweus, Citation1993). Although the phenomenon of bullying among youth has been put under scientific scrutiny, defining it is still a controversial issue (Lines, Citation2008). The most agreed-upon definition includes three main criteria: (1) intentionality (goal of causing harm and/or humiliation), (2) repetitiveness, and (3) power imbalance (socially or physically) between the bully and the victim (Bouman et al., Citation2012; Olweus, Citation1993, Citation2013). Bullying behaviours occur both directly and indirectly in various interfaces, including online, which is referred to as cyberbullying (Smith et al., Citation2008). Dan Olweus, who has studied the bullying phenomenon for many years, stated that ‘being bullied by peers represents a serious violation of the fundamental rights of the child or youth exposed’ (Olweus, Citation2013, p. 770). In 1996, the World Health Assembly recognized bullying as an international public health concern (Menesini & Salmivalli, Citation2017).

The prevalence rates of bullying vary considerably between countries (10%–30%) (V. L. Marsh, Citation2018; Solberg & Olweus, Citation2003). A meta-analysis of 80 studies (both bullying perpetrators and bullying victims) among 12 – to 18-year-old students reported a mean prevalence rate of 35% for traditional bullying involvement (Modecki et al., Citation2014). In 2019, according to the National Center for Educational Statistics (2019), one out of every five (20.2%) students reported being bullied (13% were insulted, made fun of, called names; 13% were the subject of rumours; 15% were pushed, tripped, or spit on; and 15% were excluded from social occasions). Heiman, Olenik-Shemesh, and Eden (2014) found that out of 1,094 adolescents, 49% were bullied face to face and 27% were cyberbullied. Benbenishty, Khoury-Kasbari, and Astor (2006) found almost all students were exposed to verbal bullying within the past month, about half of whom were victims of moderate violence and one in five of whom reported being victims of severe bullying. Bullying incidents tend to increase throughout the elementary years, peak during early adolescent middle school years, and decline somewhat during later adolescent high school years, indicating bullying is most prevalent during middle school (V. L. Marsh, Citation2018; Rios-Ellis et al., Citation2000). The incidents also are not associated with a specific culture and appear to be a universal human behaviour.

In this study, we address bullying victimization as consisting of four factors: harm perception, intent, frequency, and power differential. In line with Skrzypiec et al.’s (Citation2019) study, the perception of harm is a key element when evaluating bullying. Thus, not all peer aggression is perceived as harmful. However, an individual may become a victim when peer aggression is intentionally harmful. Indeed, harm perception is subjective (Donoghue & Raia-Hawrylak, Citation2016) and depends on various aspects within peer relationships, such as whether the bully is someone familiar or strange (Daniels et al., Citation2010), the kind of context in which it occurs, the different types of aggression, and differences in personalities and in socio-economic status and culture (Bergmüller, Citation2013; Skrzypiec et al., Citation2019). Considering how the victim perceives the harm might provide an authentic picture of the victim experience and the impact of the bullying experiences on the victim’s well-being.

Bullying and well-being

A cross-cultural study conducted by the Children’s World Survey explored the relation between children’s experiences of bullying victimization (and kind) and their sense of well-being (SWB; Savahl et al., Citation2019). The study indicated the combined influence of physical and psychological bullying contributes significantly and negatively to SWB across age groups and geographical, cultural populations. Moreover, bullying has negative emotional, physical, and behavioural effects on victims’ well-being (Saiz et al., Citation2019; Skrzypiec et al., Citation2019; Varela et al., Citation2020). More specifically, studies have shown being bullied by peers is strongly and consistently associated with several mental health problems, such as personal distress and depressive mood, anxiety, increased fear, diminished sense of belonging, social isolation, low self-esteem, school avoidance, social anxiety, and psychoactive substance abuse (Fitzpatrick & Bussey, Citation2011; V. L. Marsh, Citation2018; Olweus & Breivik, Citation2014; World Health Organization – WHO, Citation2012). Hinduja and Patchin (Citation2010) and Garay et al. (Citation2013) showed that adolescents who are victims of bullying and cyberbullying are more likely to have suicidal thoughts or suicidal attempts, whereas adolescents who bully others are more likely to develop problems related to delinquency and higher dropout rates.

In addition, and in line with previous research (Juvonen et al., Citation2000; Smith et al., Citation2004), Hellfeldt et al. (Citation2016) found that participants who had never been victims of bullying reported significantly higher levels of well-being. Individual variation in underlying psychosomatic distress may be one explanation for why certain school children are at risk for bullying victimization (Saarento et al., Citation2013). Difficulties in children’s lives may be both a consequence of and partial explanation for bullying victimization (Hellfeldt et al., Citation2016). Moreover, interpersonal behaviour styles and psychosocial factors may interact to create a vicious cycle in which children place themselves at risk, which might explain the reduced well-being reported among victims.

Yet, research is limited regarding the personal factors that affect this connection and mediate the relationship between bullying victimization and low levels of well-being.

Several studies have investigated the personal factors related to high levels or low levels of bullying victimization, for example, one’s capacity for resilience, self-perception (Analitis et al., Citation2009; Saiz et al., Citation2019), a positive/negative sense of self, self-regulation, and decision-making skills (Gaspar et al., Citation2014; Lazaro-Visa et al., Citation2019). Most of them, however, do not address possible mediating personal factors in this link. Understanding the mediation effects in this model enables the study of factors that are involved in this process at both the theoretical and practical level. Detecting their effect in this relationship may contribute to a deeper understanding of this link and assist in the design of more accurate programs for the treatment and prevention of bullying among adolescents. Additionally, recognizing their effect can help in planning intervention programs to foster positive aspects in individual behaviours and characteristics, in line with theresearch literature (V. L. Marsh, Citation2018; Menesini & Salmivalli, Citation2017).

In this study, we examined the possible moderating effect of two major personal variables connected to bullying as well as to well-being among youth – resilience and self-concept – with the aim of examining their potential meditation effect in the relationship between bullying victimization and SWB. More specifically, we hypothesize that this relationship is mediated by self-concept and resilience, which recent studies show are highly linked to being bullied and to one’s SWB.

The mediating effect of self-concept and resilience

Self-concept. Many studies indicate bullying victims have a negative view of themselves and their situation, resulting in diminished self-concept. They may experience depression and anxiety because of their poor global self-esteem. Additionally, they may look at their lives as a sequence of failures and disappointments, and feel ashamed, weak, and unattractive (Garay et al., Citation2013; Olweus & Breivik, Citation2014). A vicious circle may therefore be created such that students with low self-concept will be more victimized, further damaging their self-esteem and leading to suicidal ideation and self-injurious behaviour (Garay et al., Citation2013; Olweus & Breivik, Citation2014; World Health Organization – WHO, Citation2012). Several cross-sectional studies have pointed out links between being bullied and low self-esteem (Gendron et al., Citation2011; Hawker & Boulton, Citation2000; O’Moore & Kirkham, Citation2001), leading to reduced life satisfaction (Flashpohler et al., Citation2009), fewer friends (Eslea et al., Citation2003), depression (Hawker & Boulton, Citation2000), feelings of loneliness (Eslea et al., Citation2003), and symptoms of psychosomatic distress (Hellfeldt et al., Citation2016).

High levels of self – concept are related to a positive evaluation of one’s self-worth and one’s sense of competence and are considered contributors to one’s overall SWB and, specifically, a buffer against depressive symptoms (Sowislo & Orth, Citation2013; Steca et al., Citation2014).

Resilience. Another variable that may mediate the examined relationships is resilience. Resilience is described as (a) a protective process, (b) the interaction of protection and risks, and (c) a conceptual tool within predictive models (Elias et al., Citation2006; Moore & Woodcock, Citation2017). The operational definition of resilience varies and has included hardiness, optimism, competence, self-esteem, social skills, achievement, and the absence of pathology in the face of adversity (Prince-Embury, Citation2007). It is a complex construct that is typically defined as the attainment of positive outcomes, adaptation, or developmental milestones in spite of significant adversity, risk, or stress (Goldstein & Brooks, Citation2006; Kaplan, Citation2006; Naglieri & LeBuffe, Citation2006).

A study that have explored the links between bullying and resilience have revealed that, in general, students with high levels of resilience are less likely to engage in any aggressive behaviours or be bullied (Donnon, Citation2010) and that bullying appears to decrease if resilience is improved, especially through emotional-regulation strategies and sharing the harm experience with others (Bowes et al., Citation2010; Lisboa & Killer, Citation2008).

Moore and Woodcock (Citation2017) examined the relationship between bullying factors and resilience subfactors: (1) Mastery (optimism, self-efficacy and adaptability); (2) Relatedness (trust, support, comfort and tolerance); (3) Emotional reactivity (sensitivity, recovery, and impairment). The authors found that higher levels of all subfactors can help protect against depression and anxiety, that individuals with poorer resilience are more likely to be harmed in bullying episodes (Donnon, Citation2010; Moore & Woodcock, Citation2017), that people exhibiting lower levels of resilience subfactors are more likely to be victims of bullying than perpetrators (no gender differences) (Moore & Woodcock, Citation2017). In addition, lower levels of mastery and relatedness indicate poorer self-concept and feelings of depression but not social anxiety. These results support previous research showing improved relationships with primary caregivers, including warm familial relationships and positive home environments, are associated with increased resilience to bullying effects (Bowes et al., Citation2010).

Gender differences

Gender may play a role in the relationships depicted above. Statistics on bullying among children and youth show that a higher percentage of female students report being bullied at school than do male students (24% vs. 17%), and a higher percentage of boys report being physically bullied (6% vs. 4%). By contrast, a higher percentage of girls report being the subjects of rumours (18% vs. 9%) and excluded from social activities (7% vs. 4%) (National Center for Educational Statistics, (U.S. Department of Education), Citation2019). A study held in the Netherlands found boys more often report being bullied than do girls (Olweus & Breivik, Citation2014). Tiliouine (Citation2015) explored bullying episodes among children ages 8–12 and found boys engage more in direct forms of bullying and are more likely to be victims of physical and aggressive forms of bullying, whereas girls are more frequently victimized in general and more often subjected to more indirect, verbal forms of bullying and cyberbullying (Heiman et al., 2014; Hellfeldt et al., Citation2016; Monks et al., Citation2009). On the other hand, some studies indicate boys are somewhat more often victims as well as perpetrators, because the relationships between boys are tougher and more aggressive than between girls (Archer, Citation2004).

When interviewing children, researchers have associated indirect bullying with girls and physical bullying with boys (Giles & Heyman, Citation2005; Gini & Pozzoli, Citation2009), but indirect acts are sometimes not defined as bullying or are seen as less harmful (Forsberg et al., Citation2014).

In addition, the effects of bullying may differ across gender. Ledwell and King (Citation2015) found bullying results in stronger internalizing of problems among girls than boys, and Warner and Boulton (Citation2016) found girls appear to (1) be significantly more optimistic regarding bullying, (2) experience more anxiety about bullying, and (3) have more difficulty recovering from being bullied. However, the observed effect sizes for these differences are small. Yet, in Moore and Woodcock (Citation2017) study, gender did not appear to be a key variable in resilience and bullying.

Because the findings regarding gender differences are not conclusive, and yet gender may have an effect when we examine the mediation model, we have included in the present study a reference to this variable as well.

The current study

The current study explored the mediating effect of self-concept and resilience in the relationship between bullying victimization and SWB among adolescents. Accordingly, we assumed self-perception and resilience mediate these relationships.

Methods

Sample. The sample consisted of 507 Israeli middle school students who completed all the questionnaires’ parts. We excluded 37 participants from the analyses because they did not complete the whole questionnaire. Of the participants included in the sample, 53% were boys and 47% were girls, ages 11–16, from two public schools geographically situated in the centre of the country. Before the beginning of the study, we obtained formal consent from the ministry of education, the school principals, and the ethics committees of the university, in addition to approval from the students themselves. Students at the recruited schools were then invited to participate in class groups. They received a letter explaining the purpose and the procedure of the study. They were informed of the anonymity and the fact they could cease the study at any stage. They completed the questionnaires during one school hour. The mean age in the sample was 13.25 with a standard deviation of 0.86 (males, M = 13.28, S = 0.84; females, M = 13.21, S = 0.89). Furthermore, 28.5% of the sample was in year 7 in middle school, 36.5% were in year 8, and 35% were in year 9.

Measures

The Student Aggression and Victimization Questionnaire (SAVQ – Skrzypiec, Citation2015).

This questionnaire comprised 20 questions, each with 10 sub-questions inquiring about aggression victimization. Participants answered questions regarding bullying they had experienced during the last three months (a school term). Ten items covered bullying and aggression experiences such as ‘another person(s) spread rumours (false stories) about me,’ ‘I got hit, kicked or pushed around,’ ‘Someone was mean to me,’ and online bullying (cyberbullying). When a participant answered ‘yes,’ he/she was asked to answer a series of other questions about this act or experience, specifically, to provide information about the following: (1) harm perception – ‘how harmful was it to you?’ – on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not harmful at all to 5 = extremely harmful); (2) intent – ‘Did they deliberately intend to do this?’ – on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not intentional at all to 5 = absolutely intentional); (3) frequency – ‘During the last 3 months, how often did they do this?’ – on an 8-point Likert-type scale (1 = never to 8 = more than 3 times a week) and (4) power differential – ‘How powerful (important, liked, strong) are you compared to the person(s) concerned?’ – on a 5-point Likert type scale (1 = much less powerful to 5 = much more powerful, including a central ‘about the same’ point). If a participant answered ‘no,’ he/she was asked to move to the next question at the end of the questionnaire. They were also asked to provide demographic details. The structure and reliability of factor items about harm, intent, frequency, and power differential were tested using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with MPlus v8 and Hancock and Mueller’s coefficient H. Because it accounts for the weight of factor loadings and is not as reliant on the number of items, we deemed coefficient H (whose values are interpreted the same as Cronbach’s alpha) to be more accurate than Cronbach’s alpha. Each factor (harm, intent, frequency, and power differential) fitted well with the data and showed good reliability with a value of coefficient H > 0.800.

Well-being questionnaire, Keyes’ short form of the mental health continuum (MHC-SF) (Citation2006). The MHC-SF measures participants’ SWB in terms of flourishing and languishing. The scale consists of 14 items that were chosen as the most typical items representing the construct definition for each facet of well-being. Each of the 14 items can be scored between 0 and 5, so the total score may range from 0 to 70. Higher scores indicate a higher level of emotional well-being. Three items represent emotional well-being, six items represent psychological well-being, and five items represent social well-being. Individuals can be classified as flourishing or languishing in regard to emotional well-being. To be flourishing, individuals should report experiencing at least seven of the symptoms ‘every day’ or ‘almost every day,’ and to be ‘languishing,’ individuals must report that experiencing at least seven of the symptoms ‘never’ or ‘once or twice.’ The scale showed excellent internal consistency (> .80) and discriminant validity among adolescents (ages12-18). Cronbach’s alpha was .93 for this study.

Resilience scale (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) (Connor & Davidson, Citation2003). This scale provides an indication of the state of resilience among participants. Participants rated a shortened version of 10 items on a 5-point scale (0 = not true at all, 4 = true nearly all of the time), with higher scores representing higher resilience. The scale measures resilience as an accumulation of personal strengths and positive adaptation to stressful events and has demonstrated a significant inverse relationship with indices of psychological distress and positive correlations with measures of well-being. Sample items include ‘I can adjust myself to changes in my life,’ ‘I can cope with most of the challenges,’ and ‘Failure does not easily hurt my perseverance and determination.’ The scale showed high construct validity with α ranging from .87 to .95. Cronbach’s alpha was .87 for this study.

Self-concept scale (H. W. Marsh, Citation1990). The global self-concept scale measures the amount of time participants feel good about themselves and consists of 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always). Participants were asked to rate declarative statements such as ‘Overall, most things I do turn out well’ and ‘I have a lot to be proud of.’ The scale showed good psychometric properties, and Cronbach’s alpha was .76 for this study.

Results

Pearson’s correlations were analysed between all research variables in order to conduct an initial test of the research hypothesis. Descriptive statistics and the correlations are presented in

Initially, we analysed the levels of the examined variables among the participants. indicates that, in general, the study participants reported moderate levels of bullying victimization and relatively high levels of well-being, self-concept, and resilience.

Table 1. Pearson correlations, descriptive statistics, and cronbach’s alpha coefficients between the study variables

An examination of the Pearson correlation revealed initial support for the research hypotheses. Specifically, bullying victimization has a significant, negative correlation with well-being such that as bullying victimization increases, one’s SWB decreases. Additionally, we found bullying victimization is significantly negatively correlated with self-concept and resilience, so as bullying victimization increases, the levels of self-concept and the levels of resilience decrease. We also found SWB is significantly positively correlated with both self-concept and resilience. More specifically, as levels of self-concept increase, so does well-being, and as levels of resilience increase, so does SWB. In addition, we found self-concept and resilience are positively and significantly correlated. We found no significant correlations between the age of the participants and the research variables.

To examine the research hypotheses regarding the mediating role of both self-concept and resilience in the relationship between bullying victimization and well-being, we performed a mediation model analysis (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986), using the PROCESS add-on to SPSS 25 (Hayes, Citation2009, model, p. 4). To calculate the indirect effect of the mediators, we estimated the regression coefficients as suggested by Hayes (Citation2018). Specifically, Path a was estimated as the unique effect of the independent variable on the mediators. Path b, however, was estimated as the unique effect of the mediator on the dependent variable while controlling for the independent variable. Lastly, we estimated the indirect effect through a bootstrapping procedure of 5,000 subsamples. Full mediation model statistical results are presented in .

Table 2. Direct and indirect effects of bullying victimization, self-concept, and resilience on well-being

indicates the total effect of bullying victimization on well-being is significant, and for every unit increase in harm, well-being decreases significantly (a significant C path). It was found that for every unit increase in bullying victimization, self-concept decreases significantly (a significant A1 path). Similarly, for every unit increase in bullying victimization, resilience decreases significantly (a significant A2 path). Lastly, when including the independent and both mediator variables in a regression model to predict well-being, we found that for every unit increase in self-concept, well-being increases significantly (a significant B1 path). Similarly, for every unit increase in resilience, well-being increases significantly (a significant B2 path). Bullying victimization, however, was not found to have a significant effect on well-being, while controlling for the mediators (a non-significant C path), indicating a full mediation effect for the mediators.

To examine the significance of the mediation effects, we used a bootstrapping procedure to test the indirect effects (A*B paths). Results indicate a significant indirect effect through self-concept ( and a significant indirect effect through resilience (

. presents the described model.

In addition, we examined the research hypotheses regarding the mediating role of both self-concept and resilience in these relationships, along with the moderating role of gender in these relationships. A moderated mediation model analysis was performed using the PROCESS add-on to SPSS (Hayes, Citation2009, model, p. 59). Full-model statistical results are presented in .

Table 3. Direct, indirect and interactions of bullying victimization, self-concept, resilience, and gender on well-being

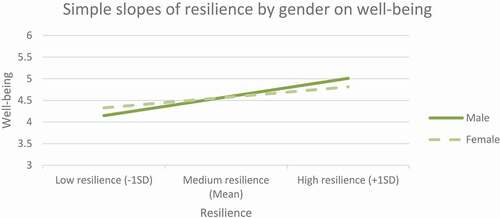

indicates that as bullying victimization increases, self-concept decreases significantly (significant a1 path), with no gender differences in self-concept. the effect of bullying victimization on self-concept was not found to be moderated by gender. Similarly, it was found that as bullying victimization increases, resilience decreases significantly (significant a2 path). Yet, boys and girls were found to have similar levels of resilience, and as in the case of self-concept, gender does not moderate the effect of bullying victimization on resilience was not found to be moderated by gender. Lastly, both self-concept and resilience were found to have significant and positive effects on well-being (significant b1 and b2 paths). The effect of bullying victimization on well-being was found to be non-significant (non-significant c’ path), indicating a full mediation effect. Likewise, we found gender has no effect on well-being (no difference in well-being between females and males). Nevertheless, gender was found to moderates the effect of resilience on well-being. A simple slope analysis of the significant interaction effect revealed that for boys, resilience has a positive effect on well-being (), and a positive, though weaker, effect on well-being for girls (

). Therefore, except for this difference no gender differences were found in the examined mediation model.

The simple slopes of the interaction are presented in .

To test for the significance of the indirect effects of each mediator, we analysed the indirect effects for both genders on each variable independently. Specifically, the results indicate a significant indirect effect through self-concept for boys (, as well as for girls

. The difference between the conditional indirect effects of gender are significant

. Furthermore, the results indicate a significant indirect effect through resilience for boys (

, as well as for girls

. The conditional indirect effects of gender are also significant

.

Discussion and practice implications

The current study explored the relationship between bullying victimization and well-being in adolescents, focusing on the mediating personal factors: self-concept and resilience. We hypothesized that the relationship between bullying victimization and well-being in adolescents is mediated by self-concept and resilience. The hypothesized mediation model was accepted in full; thus, both high self-concept and resilience mediate the relationship between bullying victimization and SWB. Little research attention has been paid to the role of high/low levels of resilience and self-concept among bullied students in relation to their SWB (Sapouna & Wolke, Citation2013). The findings of the current study help illuminate the mechanisms through which peer victimization is associated with well-being, providing insight into the process through these psychological variables have an effect on the link. Specifically, high levels of self-concept and resilience might buffer against a decrease in well-being associated with bullying victimization.

As noted above, the current literature implies that nurturing positive variables among victims may be most effective in prevention and intervention efforts; therefore, in this study we focused on the mediating effect of two positive variables. The results imply that any efforts among adolescents to prevent bullying in general and damage to victims’ SWB in particular should address both resilience and self-concept. Moore and Woodcock (Citation2017) suggest the most important elements of resilience that should be improved in intervention programs are optimism, trust, tolerance, and sensitivity. Their research also suggests resilience-based bullying interventions should focus on developing a sense of relatedness in students, which may have a broader positive outcome for mental health and SWB (Moore & Woodcock, Citation2017). According to Brehm et al. (Citation2005), relatedness is one of three factors associated with SWB (along with a sense of utility and good health) and may not only decrease bullying, but also increase well-being and self-esteem (Brehm et al., Citation2005; Lisboa & Killer, Citation2008). Identifying more protective factors that promote resilience to bullying victimization could lead to improved intervention strategies (Bowes et al., Citation2010; Moore & Woodcock, Citation2017).

Our results join the results of a large-scale study by O’Moore and Kirkham (Citation2001) indicating children who were involved in bullying as victims, bullies, or both had significantly lower global self‐concept than children who had neither bullied nor been bullied. Yet, the results were stronger regarding children who were bullying victims: the more frequently they were victimized, the lower their global self‐concept. High self‐esteem may therefore protect children from involvement in bullying, especially as victims. Thus, the authors recommend that intervention programs among children and adolescents should prioritize reducing feelings of poor self‐concept and low self-worth that are also significantly connected to a diminished SWB. Darney et al. (Citation2013) found similar results among young adults.

Nevertheless, in examining various bullying interventions to find out ‘what works, what doesn’t, and why,’ V. L. Marsh (Citation2018, p. 18) found most of the successful programs were whole-school approaches. Although all forms of bullying may not occur primarily on school grounds, especially cyberbullying, which can occur everywhere, schools can help regulate bullying behaviours by modifying the variables mentioned. Marsh concluded with the recommendation that interventions programs should take into account the school context, student demographics, and school-specific bullying prevalence and work to develop positive personal characteristics and behaviours among students. Marsh also argued that intervention programs promoting pro-social behaviour must be aligned with research rather than anecdotal solutions, which are more prevalent in school intervention efforts.

By the same token, intervention programs should also seek to foster students’ SWB in school environments, including their safety and welfare in and out of the classroom, which were found to be risk factors for persistent victimization (Aldridge & Machesney, Citation2018; Brendgen et al., Citation2016; Loukas & Pasch, Citation2013). One’s SWB at school may serve as a first indicator of later internalizing symptoms; thus, teachers could further inquire about these symptoms when talking with victims, either at their own initiative or in response to students who have been bullied and approached them (T. M. L. Kaufman et al., Citation2018). Education policy should also focus on promoting positive mental health through developing students’ well-being in school (Greco et al., 2019).

A variety of intervention models have been proposed to reduce or prevent bullying (Cantone et al., Citation2015; Gaffney et al. (Citation2019). Some of them have focused directly on the students involved, whereas others have focused on change of the broader social climate. Yet, in their extensive systematic and meta-analytical review of the effectiveness of bullying prevention programs, Cantone et al. (Citation2015) as well as Gaffney et al. (Citation2019), argues that no specific variables that make a programme effective and replicable are well established. The researchers also argue most of the intervention programs are effective in changing the opinion on bullying among students but are less effective in actually changing the dynamics of bullying. Our study adds specific individual variables that are recommended for inclusion in intervention programs, and thus may increase the effectiveness of future programs.

Regarding gender differences in the examined model, the results indicate the only gender difference is the stronger positive effect of resilience on well-being for boys. As presented in the introduction, the gender differences in bullying episodes are inconclusive and apparently complex, both regarding their different roles in bullying acts and in relation to the outcomes (Scheithauer et al., Citation2006; Underwood et al., Citation2001) Gruber and Fineran (Citation2008) argued girls may experience more severe outcomes of bullying than boys, whereas another study indicated bullying might have gender-specific consequences, but only when taking into account both the duration of the bullying and which outcome the bullying is being linked to (Carbone-Lopez et al., Citation2010). In addition, Carbone-Lopez et al. studied two longitudinal datasets covering 1,222 adolescents in 15 schools across the US and found no gender differences in bullying outcomes. Similarly, researchers found no significant gender differences in the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs (Kärnä et al., Citation2011), while Marucci et al. (Citation2020) found teachers are more aware of bullying perpetrated by girls.

The results of the current study add a small contribution to the state of the art regarding gender differences, pointing out at the importance of enhancement of resilience for boys when developing intervention programs for coping with bullying and its effects on the victims.

Despite the slight difference in this issue between genders, note that it is was significant for both genders.

Limitations and future research directions

The data in this study were obtained from self-report questionnaires, which may impair generalization, due to biases such as social desirability, the tendency to respond positively or negatively, the tendency to resist and/or to give unconventional answers, and/or privacy concerns that may lead to participants’ inaccuracies. In addition, the study group may have a socio-demographic bias. Because the sample comprises participants who mostly come from homes with average and above-average socioeconomic status, the generalizability of the study findings may again be impaired. Future studies could include participants from more diverse socioeconomic classes and sectors, in order to strengthen the generalizability and validity of the findings. An in-depth examination of the differences between genders is needed, and it could be done for example, through Examining the model separately for populations of girls and boys.

For a broader, deeper picture of the associations between bullying victimization and SWB among adolescents, future studies should examine the mediation of additional variables so that they can be included in research-based intervention programs. Furthermore, in the current study, we addressed the general concept of well-being. Future studies could address to several dimensions (emotional, cognitive, and social) related to the well-being of adolescents.

Given the significant amount of data on the prevalence of bullying and its harmful effects, and because not many bullying interventions are effective, this study suggests focusing on specific personal positive variables could be valuable when developing youth intervention programs intended to prevent and mitigate the negative impact of bullying experiences on well-being. Such revamped programs could decrease bullying acts and their negative implications for well-being, and thus may lead to more effective accurate research-based interventions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aldridge, J. M., & McChesney, K. (2018). The relationships between school climate and adolescent mental health and wellbeing: A sys- thematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Research, 88, 121–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2018.01.012

- Analitis, F., Velderman, M. K., Ravens, S. U., Detmar, S., Erhart, H., Berra, S., Alonso, J., & Rajmil, L. (2009). Being bullied: Associated factors in children and adolescents 8-18 years old in 11 European countries. Pediatrics, 123(2), 569–577. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008

- Archer, J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic Review. Review of General Psychology, 8(4), 291–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bergmüller, S. (2013). The Relationship between cultural individualism–collectivism and student aggression across 62 countries. Aggressive Behavior, 39(3), 182–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21472

- Bouman, T., Van Er Meulen, M., Goossens, F., Olthaf, T., Vermande, M., & Aleva, E. (2012). Peer and self-reports of lines victimization and bullying: Their differential association with internalizing problems and social adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 50(6), 759–774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2012.08.004

- Bowes, L., Maughan, B., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T., & Arseneault, L. (2010). Families promote emotional and behavioral resilience to bullying: Evidence of an environmental effect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(7), 809–814. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02216.x

- Brehm, S., Kassin, S., & Fein, S. (2005). Social psychology. Houghton Mifflin.

- Brendgen, M., Girard, A., Vitaro, F., Dionne, G., & Boivin, M. (2016). Personal and familial predictors of peer victimization trajectories from primary to secondary school. Developmental Psychology, 52(7), 1103–1114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000107

- Cantone, E., Piras, A., Vellante, M., Preti, A., Daníelsdóttir, S., D’Aloja, E., Lesinskiene, S., Angermeyer, M., Carta, M., & Bhugra., D. (2015). Interventions on bullying and cyberbullying in schools: A Systematic Review. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 11(Suppl 1 M4), 58–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901511010058

- Carbone-Lopez, K., Esbensen, F. A., & Brick, B. T. (2010). Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: Gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 8(4), 332–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204010362954

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

- Daniels, T., Quigley, D., Menard, L., & Spence, L. (2010). “My best friend always did and still does betray me constantly”: Examining relational and physical victimization within a dyadic friendship context. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 25(1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573509357531

- Darney, C., Howcroft, G., & Stroud, L. (2013). The impact that bullying at school has on individual’s self-esteem during young adulthood. International Journal of Education and Research, 1(8), 1–16.

- Donnon, T. (2010). Understanding how resiliency development influences adolescent bullyingand victimization. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 25(1), 101–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573509345481

- Donoghue, C., & Raia-Hawrylak, A. (2016). Moving beyond the emphasis on bullying: A generalized approach to peer aggression in high school. Children & Schools, 38(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdv042

- Elias, M., Parker, S., & Rosenblatt, J. (2006). Building educational opportunity. In S. Goldstein & R. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 315–336). Springer.

- Eslea, M., Menesini, E., Morita, Y., O’Moore, M., Mora-Merchán, J. A., Pereira, B., & Smith, P. K. (2003). Friendship and loneliness among bullies and victims: Data from seven countries. Aggressive Behavior, 30(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20006

- Fitzpatrick, S., & Bussey, K. (2011). The development of the social bullying involvement scales. Aggressive Behavior, 37(2), 177–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20379

- Flashpohler, P. D., Elfstrom, J. L., Vanderzee, K. L., Sink, H., & Birchmeier, Z. (2009). Stand by me: The effects of peer and teacher support in mitigating the impact of bullying on quality of life. Psychology in the Schools, 46(7), 636–649. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20404

- Forsberg, C., Thornberg, R., & Samuelsson, M. (2014). Bystanders to bullying: Fourth to seventh grade students’ perspectives on their reactions. Research Papers in Education, 29(5), 557–576. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2013.878375

- Gaffney, H., Farrington, D. P., & Ttofi, M. M. (2019). Examining the effectiveness of school-bullying intervention programs globally: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1(1), 14–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-0007-4

- Garay, R. M., A´vila, M. E., & M´artinez, B. (2013). Violencia escolar: Un an´alisis desde los diferentes contextos de interaccio´n [School violence: An analysis from different interaction contexts]. Psychosocial Intervention, 22(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5093/in2013a4

- Gaspar, T., Gaspar De-matos, M., Ribeiro, J., Pais, L. A., & Albergaria, F. (2014).Psychosocial factors related to bullying and victimization in children and adolescents. Health Behavior and Policy Review, 1(6), 452–459. ראש הטופסתחתית הטופס. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14485/HBPR.1.6.3

- Gendron, B. P., Williams, K. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2011). An analysis of bullying among students within schools: Estimating the effects of individual normative beliefs, self-esteem, and school climate. Journal of School Violence, 10(2), 150–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2010.539166

- Giles, J. W., & Heyman, G. D. (2005). Young children’s beliefs about the relationship between gender and aggressive behavior. Child Development, 76(1), 107–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00833.x

- Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2009). Gender roles and bullying: Behavior and motives in the peer context. In J. H. Urlich & B. T. Cosell (Eds.), Handbook on gender roles: conflicts, attitudes and behaviors (pp. 93–121). New York.

- Goldstein, S., & Brooks, R. (2006). Why study resilience? In S. Goldstein & R. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 3–16). Springer.

- Gruber, J. E., & Fineran, S. (2008). Comparing the impact of bullying and sexual harassment victimization on the mental and physical health of adolescents. Sex Roles, 59(1–2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9431-5

- Hawker, D. S., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(4), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00629

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

- Hellfeldt, H., Gill, E. P., & Johansson, B. (2016). Longitudinal analysis of links between bullying victimization and psychosomatic maladjustment in Swedish schoolchildren. Journal of School Violence, 17(1), 86–98. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2016.1222498

- Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2010). Cyberbullying and suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 14(3), 206–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2010.494133

- Juvonen, J., Nishina, A., & Graham, S. (2000). Peer harassment, psychological adjustment, and school functioning in early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(2), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.349

- Kaplan, H. (2006). Understanding the concept of resilience. In S. Goldstein & R. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 39–48). Springer.

- Karna, A., Voeten, M., Little, T., Poskiparta, E., Kaojonen, A., & Salmivalli, C. (2011). A large-scale evaluation of the KiVa antibullying program: grades 4–6. Child Development,82(1), 311–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01557.x.

- Kaufman, T. M. L., Kretschmer, T., Huitsing, G., & Veenstra, R. (2018). Why does a universal anti-bullying program not help all children. Explaining persistent Victimization during an intervention. Prevention Science, 19(6), 822–832. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0906-5

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2006). Mental health in the CDS youth: Is America’s youth flourishing? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(3), 395–402. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.395

- Lazaro-Visa, S., Palomera, R., Briones, E., Fernansez-Fuertes, A., & Fernández-Rouco, N. (2019). Bullied adolescent’s life satisfaction: Personal competencies and school climate as protective factors. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01691

- Ledwell, M., & King, V. (2015). Bullying and internalizing problems: Gender differences and the buffering role of parental communication. Journal of Family Issues, 36(5), 543–566. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13491410

- Lines, D. (2008). The bullies, understanding bullies and bullying. Jessica Kingsley Publishing.

- Lisboa, C., & Killer, S. (2008). Coping with peer bullying and resilience promotion: Datafrom Brazilian at-risk children. International Journal of Psychology, 43, 711–723. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101810

- Loukas, A., & Pasch, K. E. (2013). Does school connectedness buffer the impact of peer victimization on early adolescents’ subsequent adjustment problems? Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(2), 245–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431611435117.

- Marsh, H. W. (1990). SDQ manual: Self-description questionnaire. University of Western Sydney, Australia.

- Marsh, V. L. (2018). Bullying in school: Prevalence, contributing factors and interventions. Center for urban education success. The Warner School of Education at the University of Rochester. Research Brief: www.recester/edu/warner/cues

- Marucci, E., Oldenburg, B., Barrer, D., Cillessen, A., Hendrickx, M., & Veenstra, R. (2020). Halo and association effects: Cognitive biases in teacher attunement to peer-nominated bullies, victims, and prosocial students. Department of Sociology and Interuniversity Center for Social Science Theory and Methodology, Wiley https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12455

- Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2017). Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge andeffective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(1), 240–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740

- Modecki, K. L., Minchin, J., Harbaugh, A. G., Guerra, N. G., & Runions, K. C. (2014). Bullying prevalence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(5), 602–611. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007

- Monks, C. P., Smith, P. K., Naylor, P., Barter, C., Ireland, J. L., & Coyne, I. (2009). Bullying in different contexts: Commonalities, differences and the role of theory. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.01.004

- Moore, B., & Woodcock, S. (2017). Resilience, bullying and mental health: Factors associates with improved outcomes. Psychology in the Schools, 54(7). Macquarie University. 687-702. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22028

- Naglieri, J., & LeBuffe, P. (2006). Measuring resilience in children. In S. Goldstein & R. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 107–123). Springer.

- National Center for Educational Statistics, (U.S. Department of Education) (2019).

- O’Moore, M., & Kirkham, C. (2001). Self-esteem and its’ relationship to bullying behavior. Aggressive Behaviour, 27(4), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.1010

- Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell.

- Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: Development and some important changes. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 751–780. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

- Olweus, D., & Breivik, K. (2014). Plight of victims of school bullying: The opposite of well-Being. In A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, & J. E. Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being (pp. 2593–2616). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9063-8_100

- Prince-Embury, S. (2007). Resilience scales for children and adolescents: A profile of personal strengths. Pearson.

- Rios-Ellis, B., Bellamy, L., & Shoji, J. (2000). An examination of specific types of Ijime within Japanese schools. School Psychology International, 21(3), 227–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034300213001

- Saarento, S., Kärnä, A., Hodges, E. V., & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Student, classroom, and school-level risk factors for victimization. Journal of School Psychology, 51(3), 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.02.002

- Saiz, M. J., Chacón, R. M., Abejar, M., Parra, S., Larrañaga, M. E., & Yubero, J. S. (2019). Personal and social factors which protect against bullying victimization. Global Nursing, 18(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-018-0325-8

- Sapouna, M., & Wolke, D. (2013). Resilience to bullying victimization: The role of individual, family and peer characteristics. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(2013), 997–1006. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.05.009

- Savahl, S., Adams, S., Montserrat, C., Casas, F., Tiliouine, H., Benninger, E., & Jackson, J. (2019). Children’s experiences of bullying victimization and the influence on tTheir subjective well-being: A multinational comparison. Child Development, 90(2), 414–431. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13135

- Scheithauer, H., Hayer, T., Petermann, F., & Jugert, G. (2006). Physical, verbal, and relational forms of bullying among German students: Age trends, gender differences, and correlates. Aggressive Behavior, 32(3), 261–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20128

- Skrzypiec, G. (2015). The student aggression and victimization questionnaire. School of Education, Flinders University.

- Skrzypiec, G., Wyra, M., & Didaskalou, E. (2019). A global perspective of young adolescents’ peer aggression and well-being: Beyond bullying. Routledge.

- Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 376–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

- Smith, P. K., Talamelli, L., Cowie, H., Naylor, P., & Chauhan, P. (2004). Profiles of non-victims, escaped victims, continuing victims and new victims of school bullying. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74(4), 565–581. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007099042376427

- Solberg, M. E., & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29(3), 239–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10047.

- Sowislo, J. F., & Orth, U. (2013). Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. . Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 213–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028931

- Steca, P., Abela, J. R. Z., Monzani, D., Greco, A., Hazel, N. A., & Hankin, B. L. (2014). Cognitive vulnerability to depressive symptoms in children: The protective role of self-efficacy beliefs in a multi-wave longitudinal study. . Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(1), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9765-5.

- The Swedish National Agency for Education/Skolverket. (2011a). Evaluation of anti-bullying methods (Report No. 353). http://www.skolverket.se/om-skolverket/publikationer/visa-enskild-publikation?_xurl_=http%

- Tiliouine, H. (2015). School bullying victimization and subjective well-being in Algeria. Child Indicators Research, 8(1), 133–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9286-y

- Underwood, M. K., Galenand, B. R., & Paquette, J. A. (2001). Top ten challenges for understanding gender and aggression in children: Why can’t we all just get along? Social Development, 10(2), 248–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00162

- Varela, J. J., Savahl, S., Adams, S., & Reyes, F. (2020). Examining the relationship among bullying, school climate and adolescent well-being in Chile and South Africa: A cross cultural comparison. Child (2020). Child Indicators Research, 13(3), 819–838. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09648-0.

- Vivolo, A., Holt, M., & Massetti, G. (2011). Individual and contextual factors for bullyingand peer ictimization: Implications for Prevention. Journal of School Violence, 10(2), 201–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2010.539169

- Warner, I., & Boulton, M. (2016). Adolescent’s unambiguous knowledge of overcoming bullying and developing resilience. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 9(2), 199–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2016.1162761

- World Health Organization—WHO. (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC). International report from the 2009/2010 survey. http://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0007/167425/E96444_part2_5.pdf