ABSTRACT

Adolescents are a population particularly at risk of body dissatisfaction, namely body dysmorphic disorder. The most recent literature has begun to increasingly examine muscularity as a critical element of body image. The drive for muscularity is recognized in both sexes as a risk factor for muscle dysmorphia. The present study aimed to investigate the roles of attachment to parents and gender on the association between parental criticism and muscle dysmorphia symptomatology. This study included 1062 participants (49.9% female) with an average age of 17.44 years (SD = 1.14). Path analysis modeling yielded significant results show that parental criticism appears to predict body dysmorphic concerns via parental alienation in both genders. and in males in particular it is associated with a greater drive for muscularity, in accordance with the male aesthetic model of physical appearance. Limits, future directions for research and practical implications are discussed.

Introduction

Body dysmorphic concerns in male and female adolescents

Probably due to sociocultural factors and influences, body appearance is a central feature of adolescents’ self-concept (Longobardi et al., Citation2020, p. 2021). Adolescents are a population at particular risk for body dissatisfaction, with females tending to report more dissatisfaction with their appearance than males (Esnaola et al., Citation2010; Marengo et al., Citation2018). Body dissatisfaction is a central feature of a debilitating psychopathological condition, namely body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). BDD is characterized by a persistent preoccupation with perceived deficiencies or flaws in one’s appearance that cannot be perceived by others, causing distress and interfering with social functioning (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). The onset of the disorder is in adolescence, and the development of dysmorphic symptoms at a young age tends to be associated with poorer outcome, higher comorbidity, and suicide attempts in later years (Bjornsson et al., Citation2013). Older adolescents appear to be more at risk, while there is no consensus on gender as a risk factor (Longobardi, et al., Citation2021;Schneider et al., Citation2017). Some evidence suggests gender differences in the areas in which adolescents are dysmorphically concerned. For example, females report more concern about their eyes, hips, thighs, and abdomen, while males appear to be more concerned about their muscularity (Schneider et al., Citation2017). These gender differences seem to primarily reflect differences in cultural patterns of body image and male and female ideals of beauty. Given the close association between masculinity and muscularity in Western societies (Badenes-Ribera et al., Citation2019; Fabris et al., Citation2020, Citation2018), it is intuitively conceivable that male adolescents are more concerned about their musculature than females of the same age.

However, recent literature has increasingly examined musculature as a critical element of female body image due to increased societal and interpersonal pressures on adolescents and young female adults to achieve a lean, yet toned and muscular figure (Hoffmann & Warschburger, Citation2019). The pursuit of muscularity is recognized as a risk factor for muscle dysmorphic disorder in both genders (Robert et al., Citation2009), a particular subtype of BDD (Phillips & Diaz, Citation1997; Pope et al., Citation2005). Individuals with muscle dysmorphic symptoms are characterized by the perception that their bodies are not sufficiently lean and muscular (Phillips & Diaz, Citation1997; Pope et al., Citation2005). They tend to spend much of the day thinking about their own muscularity. They constantly monitor their appearance and exhibit important avoidance behaviours (Cafri et al., Citation2008; Dèttore et al., Citation2020; Olivardia, Citation2001; Phillips & Diaz, Citation1997). High levels of muscle dysmorphic symptomatology are associated with high levels of psychopathology (Badenes-Ribera et al., Citation2018; Citation2019; Longobardi et al., Citation2017), and preoccupation with muscle leads these individuals to engage in unhealthy behaviours such as excessive exercise, inappropriate dieting, and the use of anabolic steroids (Dèttore et al., Citation2020; Longobardi et al., Citation2017; Müller, Citation2020; Settanni et al., Citation2018).

Muscle dysmorphic symptomatology in adolescents

The literature on muscle dysmorphia seems to focus mainly on the adult male population of communities and in particular on populations that participate in sports, such as bodybuilders (Fabris et al., Citation2018; Rubio‐Aparicio et al., Citation2019). Despite the critical period for onset of MD, estimated to be late adolescence, similar to other forms of BDD (Fabris et al., Citation2018; Olivardia, Citation2001; Pope et al., Citation2005), few papers have examined the prevalence and risk factors of MD symptomatology in adolescents (Orrit, Citation2019; U. Pace et al., Citation2019). Schneider et al. (Citation2017) found that 44% of adolescents with BDD symptoms had muscle concerns, indicating a high risk for MD. Male adolescents are more affected by dysmorphic muscle concerns than females (Schneider et al., Citation2017) and have a strong desire for muscularity (Schneider et al., Citation2017). Male and female adolescents who participate in sports appear to be at greater risk for muscle dysmorphia, and for both genders, the pursuit of muscularity and associated appearance concerns increase the risk for unhealthy behaviours such as inappropriate dieting, overtraining, and doping (Eik‐Nes et al., Citation2018).

Given the strong impact on psychological and social functioning and the associated distress in the form of muscle dysmorphic symptomatology (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), it is important to investigate the risk factors associated with the onset of the disorder and to expand our knowledge in a particularly vulnerable sample, such as late adolescents.

Parental criticism as a risk factor for muscular dysmorphic disorder

The investigation of possible factors involved in the aetiology of MD is rather scanty in the literature. However, some evidence seems to suggest that parents have an influence on adolescents’ attitudes towards their bodies (Ricciardelli & McCabe, Citation2001; Rodgers & Chabrol, Citation2009), including satisfaction with their physical appearance in general and concern about their own muscularity (Readdy et al., Citation2011; Ricciardelli & McCabe, Citation2001). Some evidence suggests that pressure, comments, and experiences related to teasing by parents may promote greater striving for muscularity and more muscle dysmorphic symptoms (Dryer et al., Citation2016; Readdy et al., Citation2011).

Parental criticism has been linked to a range of psychological symptoms (Ammerman & Brown, Citation2018; Horowitz et al., Citation2015; Yates et al., Citation2008), including behaviours associated with eating disorders and dysmorphic concerns (Readdy et al., Citation2011; Rodgers & Chabrol, Citation2009). In addition, children whose parents have high expectations of them and criticize them when they do not meet these expectations, or whose parents have a particular parenting style (characterized by criticism and strict and controlling behaviour), tend to develop perfectionistic traits (Flett et al., Citation2002), which are strongly associated with MD (Dryer et al., Citation2016).

In this context, U. Pace et al. (Citation2019) have shown that parental psychological control tends to increase the level of pathological worry in adolescents, which in turn tends to increase muscle dysmorphic symptoms. The authors therefore hypothesize that MD is an adaptive response by adolescents to feelings of anxiety and insecurity associated with the exercise of parental psychological control that limits and frustrates their need for independence and autonomy. However, if the survey of risk factors for MD in adolescence is scanty, there is even less data on the possible role of family variables and, in particular, in relation to the relationship with parents (Fabris et al., Citation2018; U. Pace et al., Citation2019). A contribution in this regard is made by Fabris et al. (Citation2018), who found an association between MD symptoms and insecure attachment in a sample of bodybuilders. There appears to be an association between parental attachment and the quality of the parent-child relationship and body image disturbance (Cash et al., Citation2004; Fabris et al., Citation2018). According to attachment theorists (Bartholomew, Citation1990; Bowlby, Citation1973, Citation1982), the child builds models for the representation of self, other, and the relationships between the two in their relationships with their caregivers. Fabris et al. (Citation2018, p. 274) summarize, ‘When a caregiver appropriately responds to a child’s emotional needs, the child will develop a positive self-image. It perceives itself as lovable and perceives others as trustworthy, benevolent, and emotionally accessible when its needs are met. In contrast, when a caregiver is not supportive and accessible, the child develops negative models of self and others.’ Several studies indicate a link between body image disturbance and insecure attachment (Cash et al., Citation2004; Fabris et al., Citation2018). It is possible that the development of a negative self-presentation as inadequate or unworthy of love is reflected in the way the subject perceives his or her own image, which fuels feelings of inadequacy and fear of abandonment (Fabris et al., Citation2018) or reinforces anxiety about one’s physical appearance. Thus, adolescents with insecure attachment may develop feelings of low self-esteem, insecurity, vulnerability, and fear of rejection by others, which may be reflected in body image by activating dysmorphic concerns and associated risky behaviours aimed at counteracting emotional distress and perceptions of rejection. In other words, adolescents may believe that a positive body image can reduce the risk of abandonment or rejection. However, previous attachment experiences and the feelings of inadequacy and insecurity they have instilled in self-presentation may cause the subject to be very sensitive to the issue of physical appearance and activate a persistent sense of inadequacy or imperfection.

Several lines of evidence suggest that, among adolescents, perceptions of a high-quality relationship with parents, characterized by high levels of trust and communication and low levels of alienation from parents, tend to be protective factors for body image disturbance and eating disordered behaviours (Cortés García et al., Citation2019; Pelletier Brochu et al., Citation2018), the latter of which is related to MD (Badenes-Ribera et al., Citation2019). Although there is some evidence for a role of parental influences in muscularity seeking, as mentioned previously, and although there is also evidence for a possible link between MD and insecure attachment, no study has examined the relationship between attachment to parents and muscular dysmorphic symptomatology in adolescents.

Parental criticism and attachment to parents

Parental criticism could influence the risk of MD by affecting the quality of the relationship with parents. Parental criticism typically characterizes a devaluing and rejecting caregiving environment that negatively affects the quality of the relationship with parents and causes adolescents to feel alienated (Fonagy et al., Citation2000; Yates et al., Citation2008). There is some evidence in the literature of a relationship between parental criticism and perceptions of parental alienation (Yates et al., Citation2008). In this context, parental criticism may contribute to the development of a negative self- and other-image, the development of positive relationships, and the ability to regulate emotions and live a reciprocal and emotionally supportive relationship (Yates, Citation2004; Yates et al., Citation2008). In this context, according to the authors (Yates et al., Citation2008), adopted children would be led to turn to their own selves and bodies rather than others when distressed, thus adopting coping strategies based on Sè and their own bodies. These considerations reflect some theoretical observations that consider muscular dysmorphic symptomatology as a strategy developed by individuals to counteract a sense of insecurity and fragility that they probably acquired in their own evolutionary experiences in relationships with significant figures (Badenes-Ribera et al., Citation2019b; Fabris et al., Citation2018). However, perceived alienation has been identified as a mediating factor between parental criticism and a range of outcomes such as non-suicidal self-harm and antisocial behaviour (Yates et al., Citation2008). However, to our knowledge, no study has examined the quality of the relationship with parents in a population of adolescents as a mediating factor between parental criticism and muscle dysmorphic symptomatology in either gender.

The purpose of this study

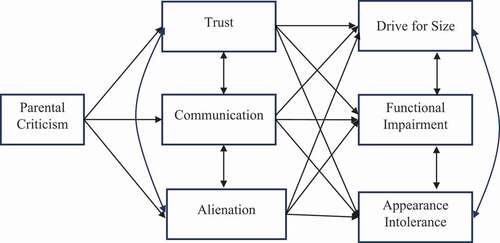

Based on the above theoretical framework, the purpose of this article was to analyse the relationship between parental criticism and MD symptomatology mediated by attachment to parents. Therefore, this study focuses specifically on the pathway by which parental criticism leads to low attachment to parents, which in turn leads to MD symptoms, as shown in .

Figure 1. Hypothesized indirect effect model: the relationships between Parental Criticism and Muscle Dysmorphia symptomatology mediated by the Attachment to Parents

This model was based on both previous empirical findings and theoretical considerations. The main hypotheses were as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Parental criticism will be associated with attachment.

Hypothesis 2: Attachment to parents will have a direct influence on muscle dysmorphic symptomatology. Specifically, participants with lower attachment to their parents will exhibit more symptoms of delusions of grandeur, functional impairment, and intolerance of appearance.

Hypothesis 3: The attachment to parents will mediate the relationship between parental criticism and the indicators of muscle dysmorphia symptomatology.

Finally, our study aims to investigate the role of gender as a moderator of the relationship between the constructs under investigation. We hypothesize that both males and females will show an association between parental criticism and MD. However, considering the subscales of the Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory, we expect females to report a lower or no association between parental criticism and the urge for muscularity subscales. In addition, we hypothesize that higher drive for size will be related to higher intolerance of appearance in males, but not in females.

Method

Participants

A convenience sample of 1062 participants with a mean age of 17.44 years (SD = 1.14, min = 15, max = 21) was recruited from four high schools in North-Western Italy. Of the 1062 participants, 49.9% were females, 49.6% were males, 0.4% were of another gender, and 0.1% did not report this information. Moreover, approximately 24% of the participants were in the third year of high school, and 33.2% and 42.7% were in the fourth and fifth years, respectively, whereas 0.2% of the participants did not report this information.

Instruments

Socio-demographic characteristics

Participants completed a questionnaire inquiring about their age, gender, and education level.

Parental criticism

This was assessed using the parental expectation and parental criticism subscales of the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS; Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, Citation1990Citation1990; Italian version: Lombardo, Citation2008). The Italian version of the MPS is a multi-dimensional self-report measure designed to measure perfectionism. It contains 35 items and includes 4 dimensions of perfectionism: concern over mistakes and doubts about actions (13 items) (i.e. ‘If I fail at work/school, I am a failure as a person’), personal standards (7 items) (i.e. ‘I set higher goals than most people’), parental expectations and parental criticism (9 items) (i.e. ‘As a child, I was punished for doing things less than perfectly’), and organization (6 items) (i.e. ‘organization is very important to me’). The PE and PC scales reflect the belief that one’s parents set very high goals and are overly critical. Good internal consistency and convergent validity with other measures of perfectionism have been demonstrated for the MPS (Lombardo, Citation2008). In this study, the internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the PE and PC scales was good (α = .82 for all sample, α = .81 for males, and α = .84 for females).

Attachment to parents

This was assessed using the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, Citation1987; Italian version: C. S. Pace et al., Citation2011). The IPPA is a 53-item scale designed to assess affective and cognitive dimensions of relationships with parents and close friends. It consists of two scales: the first scale measures the attachment to parents and consists of 28 items on a Likert-type scale, and the latter measures the attachment to peers and consists of 25 items on a Likert-type scale. Both provide an indication of the perceived level of security in relationships with specific attachment figures (e.g. parents and peers). This level is calculated by using dimensions such as the quality of communication and the extent of anger, alienation, and/or hopelessness resulting from an unresponsive or inconsistently responsive attachment figure. The Italian version of the IPPA has been used in a number of studies, and its reliability and validity have been shown to be satisfactory (Li et al., Citation2015; C. S. Pace et al., Citation2011). In the current sample, the internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was good; specifically, it was .87 for parent trust (α = .85 for males, and α = .89 for females), .85 for parent communication (α = .84 for males, and α = .88 for females), and .83 for parent alienation (α = .80 for males, and α = .85 for females).

Muscle dysmorphia symptomatology

This was assessed using the Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory (MDDI; Hildebrandt et al., Citation2004; Italian version: Santarnecchi & Dèttore, Citation2012). The MDDI is a multi-dimensional self-report measure to measure the risk of MD. It is composed of 13 items structured around three dimensions: desire for size (5 items) (i.e. ‘I wish I could get bigger’), appearance intolerance (4 items) (i.e. ‘I am very shy about letting people see me with my shirt off’), and functional impairment (4 items) (i.e. ‘I pass up social activities with friends because of my workout schedule’). The desire for size (DFS) subscale consists of questions regarding thoughts about being smaller, less muscular, and weaker than desired, or the desire to increase one’s size and strength. The appearance intolerance (AI) subscale consists of questions addressing negative beliefs about one’s body and the resulting appearance anxiety or body exposure avoidance. Finally, the functional impairment (FI) subscale consists of questions about behaviours related to maintaining exercise routines, interference of negative emotions when deviating from exercise routines, or the avoidance of social situations because of negative feelings and preoccupations about one’s body. Item response categories are on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always.’ The Italian version of the MDDI has been used in a number of studies, and its reliability and validity have been shown to be satisfactory (e.g. Longobardi et al., Citation2017; Santarnecchi & Dèttore, Citation2012). In this study, the internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was good; specifically, it was .80 for the DFS (α = .79 for males, and α = .72 for females), .87 for FI (α = .83 for males, and α = .86 for females), and .75 for AI subscales (α = .74 for males, and α = .77 for females).

Procedure and ethical considerations

The data were collected from secondary schools in North-Western Italy in 2019. In compliance with the ethical code of the Italian Association for Psychology (AIP), the participants and their parents/legal guardians were asked to sign written informed consent forms describing the nature and objective of the study. In addition, the school principals gave their consent for the students to participate in the study. In addition, ethical approval to conduct research was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Turin (protocol no. 481,729). The forms stated that data confidentiality would be assured and that participation in the study was voluntary. Participants were asked to fill in a questionnaire using paper and a pencil.

Data analysis

Exploratory analyses were first conducted to examine the normality of the distribution of the continuous variables and missing values. All values for univariate skewness and kurtosis for all variables analysed were satisfactorily within the conventional criteria for normality (−3 to 3 for skewness and −10 to 10 for kurtosis) according to the guidelines proposed by Kline (Citation2015), so the data were considered normally distributed. In addition, a maximum of 4.5% of the cases per variable were missing. Since the missing values for each of the variables were less than 5%, they are not considered to cause bias in the estimates (Graham, Citation2009). Therefore, no adjustments were made to the values for the variables measured in our study.

Secondly, descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were computed on the study variables, both in the overall sample gender (males or females). Then, independent samples t-tests were performed to investigate whether there were differences between the males and females regarding the investigated variables. A measure of effect size (Cohen’s d) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also reported for between-group comparisons (Cohen, Citation1988; Cumming & Calin-Jageman, Citation2017).

Moreover, in order to get an overall view of the relations among the variables in the model for males and females, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed on the measures. Descriptive and correlation analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 for Windows.

Additionally, a path analysis model was hypothesized, tested, and evaluated using Mplus 7.4. The estimation method was maximum likelihood with robust corrections for the estimates to accommodate nonnormality and the ordinal nature of the data. Full information maximum likelihood is used to deal with missing data: a procedure adequate for data missing completely at random and missing at random, this is the most recommended method for structural models (Finney & Di Stefano, Citation2013). The goodness of fit for each model was assessed with several fit indexes (Kline, Citation2015; Tanaka, Citation1993), specifically, (1) the χ2 statistic, which is a test of the difference between the observed covariance matrix and the one predicted by the specified model; (2) the comparative fit index (CFI), which assumes a non-central chi-square distribution with cut-off criteria of .90 or more (ideally over .95; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999) indicating adequate fit; (3) The Tucker-Lewis fit index (TLI); (4) the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% confidence interval, and (5) the standard root mean residual (SRMR). An χ2 value with a probability value greater than 0.05 indicates good fit; nevertheless, this statistic is affected by several limitation assumptions (dependence on sample size, multivariate normality, using the correct model) and is very restrictive. Therefore, other indices less affected by sample size and model complexity (Kline, Citation2015) were used. Values higher than 0.90 for the CFI and TLI or lower than 0.08 in the RMSEA and SRMR are considered a reasonable fit (Kline, Citation2015; Marsh et al., Citation2004), although values of .95 for the CFI and of .06 for the RMSEA are considered to be an appropriate model fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). In addition, confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the indirect effect. Mplus computes the bias-corrected CIs using a bootstrap resampling method to estimate these intervals. Such procedures are recommended as the best method for generating the required sampling distributions for indirect effects testing (MacKinnon & Fairchild, Citation2009). If the CI does not include zero, the indirect effect is declared statistically significant.

To test the moderating effect of gender, a multigroup analysis was conducted with two groups: Women and Men. For the multigroup analysis (for women and men), two models were examined, namely the unrestricted (freely estimated) model and the fully restricted model. The unrestricted model is the model in which the estimated parameters are freely estimated in both groups, while the fully constrained model is the model in which all estimated parameters must be the same in all groups (Byrne, Citation2012). The unconstrained model (which is freely estimated in each individual sample) serves as a baseline model against which the fit of the more constrained models can be compared. The fit of the models was comparatively assessed. Specifically, the chi-square difference test was used to test for differences in fit between nested models (Byrne, Citation2012). In addition, the fit of the comparative model was also assessed using the differences between the CFI values (ΔCFI) to determine if they were equivalent (Little, 1197). As a rule of thumb, if the difference between the CFI of the two models being compared (unconstrained and fully constrained models) is greater than 0.01, this is indicative of a moderating effect (Cheung & Rensvold, Citation2002). All statistical tests were interpreted assuming a significance level of 5% (α = .05), using two-tailed tests.

Results

Preliminary analysis

presents descriptive statistics of the study variables for both the whole sample and the gender groups. It also shows the results of independent t-tests on the study variables. Results from mean comparisons revealed statistically significant differences between males and females in all variables except parental criticism (p = .722) and parental communication (p = .264). Specifically, males showed higher scores than females on parental trust (p < .001), drive for size (p < .001), and appearance intolerance (p < .001). And, females presented higher scores than males on parental alienation (p < .001) and functional impairment (p < .001).

Table 1. Mean (SD) scores for whole sample and as a function of gender on all variables and T test

shows the correlations among all the variables under study for males and females. As can be seen in , while for males higher parental criticism was statistically associated with greater drive for size (r = .12, p = .008) and higher parental communication was statistically correlated to drive for size (r = .13, p = .003), these correlations were not observed among females (p = .981 and p = .528, respectively).

Table 2. Bivariate correlations for all variables as a function of gender

However, for females, higher parental criticism was statistically associated with appearance intolerance (r = .12, p = .009), and lower drive for size was statistically correlated to functional impairment (r = −.11, p = .016), but these correlations were not noted among males (p = .342 and p = .100, respectively).

The role of attachment to parents in the relationship between parental criticism and muscles dysmorphia symptomatology

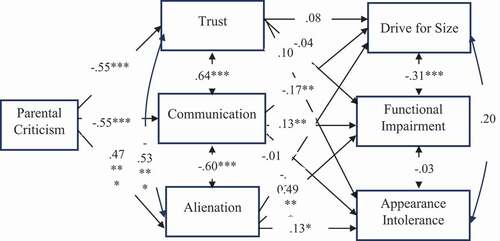

shows the standardized coefficient of the hypothetical model in the total sample. The hypothetical model tested showed an acceptable fit: (χ2 (3) = 11.335, p = .010, CFI = 0.995, TLI = 0.962, RMSEA = 0.052 [90% CI = 0.022, 0.086], SRMR = 0.019). As expected, parental criticism had a negative and significant effect on the trust and communication subscales of attachment to parents and a positive and significant effect on alienation, supporting hypothesis one.

Figure 2. Model testing mediation of Attachment to Parents on the relationships between Parental criticism and muscle dysmorphia dimensions in the total sample. For the shake of clarity, standard errors are not shown. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Nevertheless, only communication with parents and alienation had a direct effect on muscle dysmorphic symptomatology, partially supporting hypothesis two. Specifically, participants with less communication with their parents exhibited more delusions of grandeur symptoms and fewer functional impairment symptoms. In addition, participants with more alienation exhibited more symptoms of functional impairment and intolerance of appearance. No effect of trust in parents was found on muscle dysmorphic symptoms.

shows the 95% bootstrap confidence interval of the indirect effect of attachment to parents between the relationship between parental criticism and muscle dysmorphic symptomatology. Specifically, parental criticism had a positive indirect effect of parental alienation on functional impairment (β = .23, 95% CI [0.16, 0.29], p.

Table 3. The bootstrap confidence interval of the mediation model in the total sample

Multigroup analysis for gender

To examine whether the hypothesized model differed by gender, a multigroup analysis was conducted. Prior to the multigroup analysis, the hypothesized model was estimated and tested separately for males and females, and both had excellent fit indices (males: χ2 (3) = 5.386, p = .146, CFI = 0.997, TLI = 0.979, RMSEA = 0.039 [90% CI = 0.00, 0.092], SRMR = 0.015; women: χ2 (3) = 9.376, p = .025, CFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.936, RMSEA = 0.065 [90% CI = 0.020, 0.114], SRMR = 0.028). A multi-group model was then tested where the samples were considered together but the parameters were unconstrained (free estimation in each individual sample), and then a fully constrained model was tested.

The fully unconstrained model (freely estimated) showed a better fit to the data (χ2 (6) = 13.389, p = .037, CFI = 0.995, TLI = 0.965, RMSEA = 0.049 [90% CI = 0.011, 0.085], SRMR = 0.022) than the fully constrained model (χ2 (24) = 54.238, p

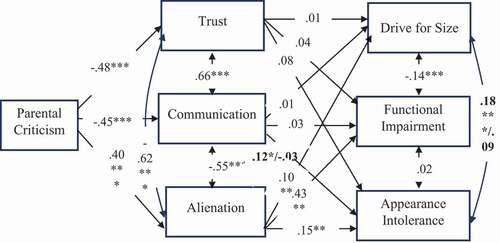

To examine whether there was a moderating effect (or effects) of gender, an analysis strategy based on model comparisons was conducted. In this case, the fully constrained model served as the baseline model against which the fit of the less constrained models was compared, i.e. the models where one constrained parameter was released at a time. This strategy resulted in the best-fitting model shown in , which revealed only two interaction (moderation) effects due to gender (χ2 (22) = 44.124, p = .003, CFI = 0.985, TLI = 0.972, RMSEA = 0.044 [90% CI = 0.025, 0.063], SRMR = = = .076). Specifically, the effect of appearance intolerance on communication with parents and the covariance between size striving and appearance intolerance.

Figure 3. Model testing mediation of Attachment to Parents on the relationships between Parental criticism and muscle dysmorphia dimensions: multigroup path analysis. Moderation effect is marked in black: the parameters on the left refer to males and the ones on the right refer to females. For the shake of clarity, standard errors are not shown. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Discussion

The current study primarily aimed to investigate the role of attachment to parents and gender in the relationship between parental criticism and MD symptomatology. Our data appear to support an association between parental criticism and muscle dysmorphic symptomatology, emphasizing the mediating role of attachment to parents. Parental criticism tends to predict an increase in muscle dysmorphic symptomatology in each of the three scales of the MDDI by increasing parental alienation or decreasing communication, indicating low quality of relationships with parents.In addition, moderator analysis revealed two gender effects: a gender effect on the relationship between parental communication and appearance intolerance, and another gender effect on the association between urges for height and appearance intolerance. For males, these patterns were positive, suggesting that higher parental communication predicts higher appearance intolerance and higher size drive is associated with higher appearance intolerance. However, these relationship patterns were not found in females.

Our study reveals that males are more affected by concerns about muscularity than females, confirming the trend found in the literature that males tend to report a greater drive for muscularity and are therefore at greater risk of receiving an MD diagnosis (Schneider et al., Citation2017). Although females do not appear to be at greater risk of reporting BDD in adolescence, the situation changes when MD is taken into account, with males reporting a higher risk (Schneider et al., Citation2017). These differences could be due to cultural influences related to stereotypical gender images, with females being more inclined to internalize an ideal slimness image, while males are encouraged to achieve lean musculature (Densham et al., Citation2017). Although the theme of muscularity is increasingly emerging in the female gender, it is also possible that the aesthetic pattern references with respect to muscularity between the two genders are different, for example, more tonic in females and more hypertrophic in males (Hoffmann & Warschburger, Citation2019). The combination of masculinity and muscularity detected in Western cultures (Badenes-Ribera et al., Citation2019; Fabris et al., Citation2020, Citation2018) could also make the issue of muscularity more significant in males than in women. In this regard, parental criticism could affect distress and body image concerns in both genders; however, in males it could significantly increase concerns about muscularity, while in the opposite gender, other characteristics of body image. Overall, these data may reflect the fact that while men and women differ in terms of the culture of appearance to which they are exposed and in terms of their beauty ideals and concerns, parental criticism may have a similar impact on body image stress in both genders. Along these lines, evidence suggests that while female adolescents receive more comments and pressure regarding their body image than male adolescents, there is no difference between the two genders in terms of concerns about being rejected for their appearance (Webb et al., Citation2017). Nevertheless, our study only considered MD as a subtype of BDD. Future studies may extend research on both sexes, including dysmorphic concerns about other bodily characteristics. Parental criticism was considered one of the risk factors of MD in adults (Dryer et al., Citation2016; Readdy et al., Citation2011), and our data seem to confirm this trend in adolescents, a sensitive period in terms of the onset of MD and BDD in general (Olivardia, Citation2001; Pope et al., Citation2005). We know that encouragement, comments, and criticism about body image can stimulate a sense of dissatisfaction with one’s own image in adolescents and a rush to adopt strategies to configure themselves to aesthetic standards (Phillips, Citation2017). Our study highlights how parental criticism can contribute to the onset of BDD, especially in males. However, data on the correlation between parental criticism and MD symptoms are scarce, and research is lacking on possible mediation factors involved in the report (U. Pace et al., Citation2019). Parental criticism tends to characterize invalidating and rejecting caregiving environments, associated with an insecure attachment and a perception of alienation towards parents in adolescents (Fonagy et al., Citation2000; Yates, Citation2004; Yates et al., Citation2008). Some evidence has pointed out that parental alienation is a factor of mediation between parental criticism and several negative psychological outcomes in adolescents (Yates, Citation2004; Yates et al., Citation2008), to which our survey adds muscle dysmorphic risk.

From the perspective of attachment theory, parental criticism can be considered a factor that contributes to the internalization of a relational model characterized by a negative view of oneself and/or the other, fuelling a feeling of insecurity and inadequacy in relationships, related to the risk of being abandoned, rejected, or criticized. In such a relational contest, teenage sororities will prompt them to turn towards the self and the body, rather than to others, in case of distress and difficulty (Yates et al., Citation2008). Parental criticism could stimulate the internalization of pathological worries that can express themselves at the body level, increasing the risk of muscle dysmorphic disorder, especially for male adolescents (U. Pace et al., Citation2019). These reflections seem in accordance with previous theorizations from the work of Fabris et al. (Citation2018), who found an association between the risk of MD and insecure attachment, particularly avoidant attachment, in a sample of bodybuilders. According to the authors, subjects with muscle dysmorphic symptoms may attempt to form, on their bodies, a kind of armour capable of defending themselves from their own feelings of inadequacy, rejection, and vulnerability, by reaching levels of aesthetic perfection (Badenes-Ribera et al., Citation2019; Fabris et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, muscle-oriented behaviour may be considered one that avoids coping with feelings of anxiety and concerns about the perception of one’s body image. However, the authors (Fabris et al., Citation2018) only speculated that such feelings could have come from adverse evolutionary experiences, characterized by criticism and devaluation in the relationships with their parents. Our study seems to go in this direction, trying to extend our knowledge about the possible relationship between insecure attachment and MD, offering an empirical basis to understanding the phenomenon, and evaluating parental criticism as a possible predictive factor.

Of course, our study is far from conclusive when it comes to the ethology of MD. First of all, we have only considered one possible risk factor, relating to the quality of the relationship with one’s parents. The literature identified several factors, at the individual and sociocultural levels, related to the aetiology of BDD and MD as a subtype (Grieve, Citation2007; Phillips, Citation2017). Therefore, from the perspective of developmental psychopathology, future studies will have to consider the relationship between the different recognized factors with respect to the risk of MD. In addition, we took parental criticism into account but did not analyse the areas in which criticism was predominantly expressed in the lives of the subjects. Therefore, future studies may investigate whether criticism in general, or particular forms of criticism, are more involved in predicting the risk of MD in adolescents. Last but not least, parental alienation and parental criticism could be associated with forms of mistreatment and neglect that have not been taken into account here and which, in the future, could enrich the model along with additional variables, such as perfectionism.

In summary, our study suggests that parental criticism may be a risk factor for the onset of MD in adolescence, and that a negative relationship with parents may be a mediating factor. Specifically, it is possible that parental criticism is associated with a more negative and problematic perception of one’s body image, which increases the risk for body dysmorphic problems in both genders. However, gender might have an influence on which body areas might be affected by dysmorphic concerns, in line with cultural stereotypes of aesthetic perfection associated with gender. In this direction, it is therefore possible that parental criticism is a risk factor for MD especially in males, considering the close association between masculinity and muscularity.

Implications

Our study could have implications for both prevention plans and clinical intervention. In terms of prevention, our data encourage the need for interventions to support parenting and family relationships, pointing to parental criticism as a possible topic of intervention. At the clinical level, however, our study suggests carefully considering parental criticism and the quality of the relationship with parents in adolescents who exhibit dysmorphic concerns about their muscles.

Study limitations

Some limitations of the present work should be discussed. It is not possible to generalize the findings to people located in cities or from different cultural backgrounds. A more representative sample from different areas of Italy would have allowed for a better generalization of the results. Thus, the use of other samples in future research would be recommended. Thereby, the generalizability of our findings would be tested in the future.

The data are cross-sectional, and, therefore, it is not possible to draw inferences about cause-and-effect relationships. Although it is conceivable that parental criticism may influence the quality of parental attachment, there is evidence that individuals with insecure parental attachment tend to develop greater sensitivity to criticism (Oldmeadow et al., Citation2013). Future researchers could therefore use a longitudinal design to test the causal relationships between the variables, which could help us understand how the relationships between them develop over time. In addition, future studies might consider measuring some variables, such as parental criticism, through a third observer. Our survey also used self-report instruments, so factors such as social desirability or text comprehension may have played a role. Moreover, several studies have pointed to some biases that can stem from the use of mediation within a cross-sectional framework (Cole & Maxwell, Citation2003; Maxwell et al., Citation2011). Therefore, longitudinal studies and studies with diverse samples (e.g. clinical samples) are encouraged.

Declarations

Ethical Approval. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Availability of Data and Material

Data are available on request.

Ethics approval and Consent to participate

Please consider Ethical and procedure paragraph

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laura Badenes-Ribera

Laura Badene-Ribera, Ph.D, is associate professor Psychometrics at University of Valencia, Spain. Her mail research topic is omosexuality, body image and validation tests.

Claudio Longobardi

Claudio Longobardi, Ph.D, is associate professor at University of Turin, Italy. His main research interest is the study of interpersonal violence and child abuse and neglect, bullying behavior, adolescent social media.

Francesca Giovanna Maria Gastaldi

Francesca Giovanna Maria Gastaldi, is Assistant professor at University of Turin, Italy. Her main research interest are peer relationship and adolescent behavior.

Matteo Angelo Fabris

Matteo Angelo Fabris, Ph.D candidate in the Department of Psychology, University of Turin. His main research interests are the child abuse and neglect, body image risk factor and interpersonal violence and adolescent behavior.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013) . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

- Ammerman, B. A., & Brown, S. (2018). The mediating role of self-criticism in the relationship between parental expressed emotion and NSSI. Current Psychology, 37(1), 325–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9516-1

- Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16(5), 427–454. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02202939

- Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2018). The relationship between internalized homonegativity and body image concerns in sexual minority men: A meta-analysis. Psychology & Sexuality, 9(3), 251–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2018.1476905

- Badenes-Ribera, L., Rubio-Aparicio, M., Sanchez-Meca, J., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2019). The association between muscle dysmorphia and eating disorder symptomatology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(3), 351–371. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.44

- Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7(2), 147–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407590072001

- Bjornsson, A. S., Didie, E. R., Grant, J. E., Menard, W., Stalker, E., & Phillips, K. A. (2013). Age at onset and clinical correlates in body dysmorphic disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(7), 893–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.03.019

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Volume II: Separation, anxiety and anger. In Attachment and Loss: Volume II: Separation, Anxiety and Anger (pp. 1–429). The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

- Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(4), 664. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x

- Byrne, B. M. (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Routledge Academic.

- Cafri, G., Olivardia, R., & Thompson, J. K. (2008). Symptom characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity among males with muscle dysmorphia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(4), 374–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.01.003

- Cash, T. F., Theriault, J., & Annis, N. M. (2004). Body image in an interpersonal context: Adult attachment, fear of intimacy and social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.1.89.26987

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem0902_5

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed. ed.). Erlbaum.

- Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 558–577. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558

- Cortés‐García, L., Hoffmann, S., Warschburger, P., & Senra, C. (2019). Exploring the reciprocal relationships between adolescents’ perceptions of parental and peer attachment and disordered eating: A multiwave cross‐lagged panel analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(8), 924–934. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23086

- Cumming, G., & Calin-Jageman, R. (2017). Introduction to the new statistics: Estimation, open science, and beyond. Routledge.

- Densham, K., Webb, H. J., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Nesdale, D., & Downey, G. (2017). Early adolescents’ body dysmorphic symptoms as compensatory responses to parental appearance messages and appearance-based rejection sensitivity. Body Image, 23(2017), 162–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.09.005

- Dèttore, D., Fabris, M. A., & Santarnecchi, E. (2020). Differential prevalence of depressive and narcissistic traits in competing and non-competing bodybuilders in relation to muscle dysmorphia levels. Psychiatr Psychol Klin, 20(2), 102–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15557/PiPK.2020.0014

- Dryer, R., Farr, M., Hiramatsu, I., & Quinton, S. (2016). The role of sociocultural influences on symptoms of muscle dysmorphia and eating disorders in men, and the mediating effects of perfectionism. Behavioral Medicine, 42(3), 174–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2015.1122570

- Eik‐Nes, T. T., Austin, S. B., Blashill, A. J., Murray, S. B., & Calzo, J. P. (2018). Prospective health associations of drive for muscularity in young adult males. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(10), 1185–1193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22943

- Esnaola, I., Rodríguez, A., & Goñi, A. (2010). Body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressures: Gender and age differences. Salud Mental, 33(1), 21–29. https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/salmen/sam-2010/sam101c.pdf

- Fabris, M. A., Badenes-Ribera, L., Longobardi, C., Demuru, A., Konrad, Ś. D., & Settanni, M. (2020). Homophobic bullying victimization and muscle Dysmorphic concerns in men having sex with men: The mediating role of paranoid ideation. Current Psychology, 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00857-3

- Fabris, M. A., Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., & Settanni, M. (2018). Attachment style and risk of muscle dysmorphia in a sample of male bodybuilders. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(2), 273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000096

- Finney, S. J., & Di Stefano, C. (2013). Non normal and categorical data in structural equation modelling. In G. R. Hancock & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), A second course in structural equation modelling (2nd ed., pp. 439–492). Information Age.

- Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Oliver, J. M., & Macdonald, S. (2002). Perfectionism in children and their parents: A developmental analysis. In G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 89–132). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/10458-004

- Fonagy, P., Target, M., & Gergely, G. (2000). Attachment and borderline personality disorder: A theory and some evidence. Psychiatric Clinics, 23(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70146-5

- Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive therapy and research, 14(5), 449–468. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01172967

- Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 549–576. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530

- Grieve, F. G. (2007). A conceptual model of factors contributing to the development of muscle dysmorphia. Eating Disorders, 15(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260601044535

- Hildebrandt, T., Langenbucher, J., & Schlundt, D. G. (2004). Muscularity concerns among men: Development of attitudinal and perceptual measures. Body Image, 2(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.01.001

- Hoffmann, S., & Warschburger, P. (2019). Prospective relations among internalization of beauty ideals, body image concerns, and body change behaviors: Considering thinness and muscularity. Body Image, 28 (2019) , 159–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.011

- Horowitz, B. N., Marceau, K., Narusyte, J., Ganiban, J., Spotts, E. L., Reiss, D., Lichtenstein, P., & Neiderhiser, J. M. (2015). Parental criticism is an environmental influence on adolescent somatic symptoms. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(2), 283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000065

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1) , 1–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

- Li, J.-B., Delvecchio, E., Lis, A., Nie, Y.-G., & Di Riso, D. (2015). Parental attachment, self-control, and depressive symptoms in Chinese and Italian adolescents: Test of a mediation model. Journal of Adolescence, 43(2015), 159–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.06.006

- Lombardo, C. (2008). Adattamento Italiano della Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) [Italian adaptation of the Multidimensional Perfection Scale (MPS)]. Psicoterapia Cognitiva E Comportamentale, 14(3), 31–46.

- Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., Prino, L. E., & Settanni, M. (2020). The role of body image concerns in online sexual victimization among female adolescents: The mediating effect of risky online behaviors. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 15(1–2) , 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-020-00301-5

- Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., Prino, L. E., & Settanni, M. (2021) . Online Sexual victimization among middle school students: Prevalence and association with online risk behaviors. International Journal of Developmental Science, (Preprint) 15(1–2) , 39–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-200300

- Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Settani, M. (2017). Muscle dysmorphia and psychopathology: Findings from an Italian sample of male bodybuilders. Psychiatry Research, 256(2017), 231–236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.065

- MacKinnon, D. P., & Fairchild, A. J. (2009). Current directions in mediation analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(1), 16–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x

- Marengo, D., Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2018). Highly-visual social media and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: The mediating role of body image concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 82(2018), 63–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.003

- Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cut-off values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s findings. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11(3), 320–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

- Maxwell, S. E., Cole, D. A., & Mitchell, M. A. (2011). Bias in cross sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: Partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(5), 816–841. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.606716

- Mayville, S., Katz, R. C., Gipson, M. T., & Cabral, K. (1999). Assessing the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in an ethnically diverse group of adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 8(3), 357–362. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022023514730

- Müller, R. (2020). Muscle dysmorphia: Appearance, diagnostic approaches, research and treatment. EC Psychology and Psychiatry, 9(2), 01–09.

- Oldmeadow, J. A., Quinn, S., & Kowert, R. (2013). Attachment style, social skills, and Facebook use amongst adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1142–1149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.006

- Olivardia, R. (2001). Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the largest of them all? The features and phenomenology of muscle dysmorphia. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 9(5), 254–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10673220127900

- Orrit, G. (2019). Muscle Dysmorphia: Predictive and protective factors in adolescents. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 19(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.6018/cpd.347981

- Pace, C. S., San Martini, P., & Zavattini, G. C. (2011). The factor structure of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA): A survey of Italian adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(2), 83–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.006

- Pace, U., D’Urso, G., Passanisi, A., Mangialavori, S., Cacioppo, M., & Zappulla, C. (2019). Muscle dysmorphia in adolescence: The role of parental psychological control on a potential behavioral addiction. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01547-w

- Pelletier Brochu, J., Meilleur, D., DiMeglio, G., Taddeo, D., Lavoie, E., Erdstein, J., Pauzé, R., Pesant, C., Thibault, I., & Frappier, J. Y. (2018). Adolescents’ perceptions of the quality of interpersonal relationships and eating disorder symptom severity: The mediating role of low self-esteem and negative mood. Eating Disorders, 26(4), 388–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2018.1454806

- Phillips, K. A., & Diaz, S. F. (1997). Gender differences in body dysmorphic disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185(9), 570–577. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199709000-00006

- Phillips, K. A. (2017). Insight and Delusional Beliefs in Body Dysmorphic Disorder (pp. 103). Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Advances in Research and Clinical Practice.

- Pope, C. G., Pope, H. G., Menard, W., Fay, C., Olivardia, R., & Phillips, K. A. (2005). Clinical features of muscle dysmorphia among males with body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image, 2(4), 395–400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.09.001

- Readdy, T., Cardinal, B. J., & Watkins, P. L. (2011). Muscle dysmorphia, gender role stress, and sociocultural influences: An exploratory study. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 82(2), 310–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2011.10599759

- Ricciardelli, L. A., & McCabe, M. P. (2001). Self-esteem and negative affect as moderators of sociocultural influences on body dissatisfaction, strategies to decrease weight, and strategies to increase muscles among adolescent boys and girls. Sex Roles, 44(3–4), 189–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010955120359

- Robert, C. A., Munroe-Chandler, K. J., & Gammage, K. L. (2009). The relationship between the drive for muscularity and muscle dysmorphia in male and female weight trainers. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(6), 1656–1662. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b3dc2f

- Rodgers, R., & Chabrol, H. (2009). Parental attitudes, body image disturbance and disordered eating amongst adolescents and young adults: A review. European Eating Disorders Review: The Professional Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 17(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.907

- Rubio‐Aparicio, M., Badenes‐Ribera, L., Sánchez‐Meca, J., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2019). A reliability generalization meta‐analysis of self‐report measures of muscle dysmorphias. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 27(1) , e12303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12303

- Santarnecchi, E., & Dèttore, D. (2012). Muscle dysmorphia in different degrees of bodybuilding activities: Validation of the Italian version of muscle dysmorphia disorder inventory and bodybuilder image grid. Body Image, 9(3), 396–403. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.03.006

- Schneider, S. C., Turner, C. M., Mond, J., & Hudson, J. L. (2017). Prevalence and correlates of body dysmorphic disorder in a community sample of adolescents. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 51(6), 595–603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867416665483

- Settanni, M., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2018). Muscle Dysmorphia and anabolic steroid abuse: Can we trust the data of online research? Psychiatry Research, 263(2018), 288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.049

- Tanaka, J. S. (1993). Multifaceted conceptions of fit in structural equation models. In K. A. Bollen (Ed.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 10–39). Sage.

- Webb, H. J., Zimmer‐Gembeck, M. J., Waters, A. M., Farrell, L. J., Nesdale, D., & Downey, G. (2017). “Pretty pressure” from peers, parents, and the media: A longitudinal study of appearance‐based rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 27(4), 718–735. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12310

- Yates, T. M., Tracy, A. J., & Luthar, S. S. (2008). Nonsuicidal self-injury among” privileged” youths: Longitudinal and cross-sectional approaches to developmental process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.52

- Yates, T. M. (2004). The developmental psychopathology of self-injurious behavior: Compensatory regulation in posttraumatic adaptation. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(1), 35–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2003.10.001