ABSTRACT

New York Public Library, Drexel MS 4175 has long been of interest to scholars of early modern music. Titled “Songs vnto the violl and lute” and inscribed “Anne Twice, Her Booke”, The manuscript contains a collection of songs for a woman’s musical practice and performance in the 1620s. It also, however, contains five poems that have received no attention, including one of outstanding interest: a previously unnoticed poem in praise of Katherine Philips. “Presenting a Book to Orinda” draws liberally on the work of Restoration satirist John Oldham, and likely dates from the early 1680s. The co-presence in the manuscript of Twice’s songs and the poem on Philips calls attention to continuities between air singing and poetic exchange as cultural practices engaging women and men across the seventeenth century. This article reconsiders Drexel MS 4175 as a site of lyric collaboration, compilation, and exchange from the 1620s to the 1680s.

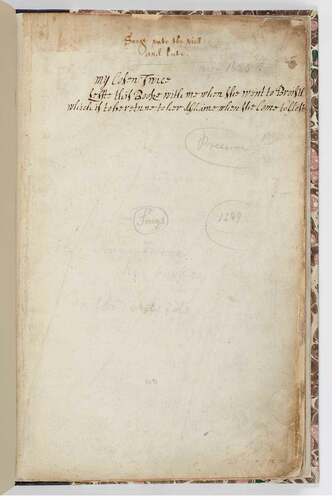

Anne Twice is a name familiar to scholars of early modern music, especially those interested in songs associated with Jacobean drama and in women’s engagement with song culture in the earlier seventeenth century. A manuscript in the Drexel collection in the New York Public Library, with the title “Songs vnto the violl and lute”, is marked on its original cover “Anne Twice, Her Booke”.Footnote1 Twenty-eight songs are collected in the manuscript’s opening folios, in musical settings for either bass viol or lute (and in some cases, in two separate settings, one for each instrument). In addition, a “Table” of contents at the end of the manuscript, compiled at the same time as the song collection, indicates that the volume once contained a total of 58 songs, most of which can be identified by the titles given. Anne Twice herself remains a very sketchy figure, the only biographical indication in the manuscript being an inscription suggesting that she lived in Gloucester, and that her book was at one time borrowed by her cousin while she travelled to Bristol: “my Cosen Twice Leffte this Booke with me when she went to Broistl which is to be returne to her AGhaine when she Come to Glost” (fol. 1r).Footnote2 Ian Spink, writing on the manuscript in the 1960s, surmises from its contents that Twice “was probably quite an accomplished singer, able to accompany herself on the lute, and her music master was evidently a man of taste”.Footnote3 Twice’s manuscript volume has, then, been located in the context of musical tuition of young women in domestic settings, and the sharing of the book with her cousin (whether female or male) is a common form of collective use for documents of this kind.

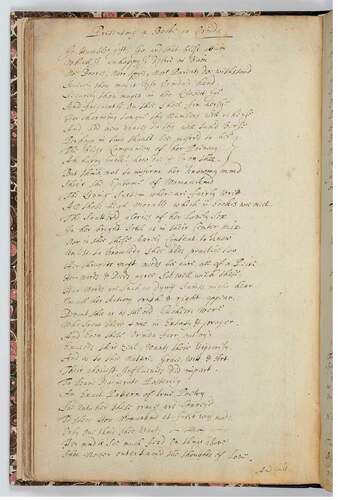

Twice’s song collection has attracted some sustained and detailed analysis, in most part for its inclusion of several songs associated with Jacobean dramatic culture.Footnote4 But the manuscript contains three other discrete sections of material, each in a different hand or hands, that have been added later in the seventeenth century and that have, to date, been noted by scholars only in passing. There is a group of five poems, which appear to date from the late 1670s to the mid 1680s; and a series of recipes written into the manuscript in reverse from the back. One final page, following the “Table” of song contents, contains accounts dated December 1699; this appears to be the last addition to the volume. Such reuse of a manuscript volume by later owners is completely commonplace, but it is unusual that these additions have received no scholarly attention, especially given the close connections in recent years between scholarship on early modern women’s literary writing and that on recipe books and on song.Footnote5 It is particularly surprising because the section of poems in the middle of the manuscript contain an item of outstanding interest to the fields of early modern women’s writing: a previously unnoticed poem addressed to the mid-seventeenth century’s preeminent woman poet, Katherine Philips, “The Matchless Orinda”. “Presenting a Book to Orinda” is a fifty-line encomium, a new addition to the known corpus of poems in praise of Philips, and one that further extends our sense of her afterlife as a poet and a paragon in manuscript compilations of the later seventeenth century.Footnote6

We explore in this article the musical and lyric content of “Anne Twice, Her Booke”, orienting ourselves in particular to the song collection and the hitherto unexplored cache of five poems in which the poem to Philips appears. (These five poems, annotated, are reproduced in the Appendix.) “Presenting a Book to Orinda” is the most notable poem of the five, and is likely to be penned by or emerge from the circle of John Oldham, the Restoration poet who died in December 1683. The poem addresses Orinda in admiration, and very much as if she were alive, and in doing so it reuses and repurposes multiple phrases from Oldham’s early encomia to women at court and in his local community. None of the other four poems have obvious connections to Oldham – one echoes significantly Thomas Creech’s translation of Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura, published in 1682 – but they seem to form a coherent collection, with four of the five poems copied in the same hand. The five poems raise more questions than, at present, can be answered, but these questions themselves extend the significance of a manuscript traversed to date only by musicological scholars. While the poems seem to have been added to the volume later than the song collection compiled by or for Anne Twice, they nonetheless reinforce the close association of airs and air singing and lyric poetry in household contexts and their material records, and the especial importance of this nexus for early modern women and consideration of their cultural praxis. Just as Katherine Philips herself is closely linked to the air culture and musical circles of Henry Lawes, a composer whose early work is represented in Twice’s song collection and who later set at least four Philips poems to music, so this newly uncovered poem written to her emerges out of a rich record of early modern women’s intertwined lyric and musical practice in seventeenth-century England.

Anne Twice’s “Songs vnto the violl and lute”

The song collection associated with Anne Twice illustrates the extensive practices of lyric and song compilation and commonplacing in which girls and women engaged, even in provincial settings, in the 1620s, as they learned, practised, and performed lyric poetry in song form. The manuscript “Table” at the end of the manuscript, compiled at the same time as the collection, lists 58 songs, of which 28 are still in the volume; among the 58, ten are duplicates, each occurring once in a setting for soprano voice and bass viol, and once for soprano voice and lute. The 28 songs present in the manuscript and the further 30 listed in the “Table” include a wide range of popular airs from the period, many of them connected to Jacobean dramatic culture, and others drawn from the manuscript and print circulation of free-standing airs and part-songs. Such a manuscript of “Songs vnto the violl and lute” is a relatively commonplace artifact of the early seventeenth century, when the craze for air singing permeated the households of upper and, increasingly, middling-class families, and the education of girls and women as well as boys and men.Footnote7 Twenty-nine books of airs were published in London between 1597 and 1622, overtaking the poetical miscellanies of the late sixteenth century as the preeminent source of lyric verse circulating among men and women in the period.Footnote8 While these poetical miscellanies had themselves collected lyrics that were frequently sung, air culture extended the affiliations of lyric and music into a large corpus of amorous and sacred lyric songs.Footnote9 Anne Twice’s book includes a representative range of airs popular in the repertoire of the period, such as “Like to the damask rose” (Song xliii), the lyric likely to be originally by Francis Quarles, in a lute setting that is believed to be by Henry Lawes. The same lute setting also occurs in Lawes’s own autograph manuscript, and as Elise Jorgens Bickford notes, if musicological scholars’ dating of the Drexel manuscript’s song collection to c. 1620 is correct, this would indicate that “Lawes’s prominence began a good decade earlier than most sources would indicate”, at the age of twenty-four.Footnote10 While this dating, and the attribution itself, has been the subject of debate, the setting also occurs in the songbook of Elizabeth Davenant, the Oxford-based sister of the playwright William, whose volume is a close comparator to Anne Twice’s book, and is dated 1624.Footnote11

Whether or not Twice’s collection is quite as early as 1620, its contents accord broadly with a 1620–1630 dating. The Petrarchan and pastoral amorous lyrics of early seventeenth-century air culture abound, including “Cloris sighed and sung and wept”, a lyric possibly written by William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, the musical setting of which is usually attributed to Alfonso Bales.Footnote12 “Cloris sighed” circulated widely in manuscript, in variations from either one stanza only – in which Cloris sighs, sings, and weeps for “Amintas that was slain” – to two or four stanzas. In the two-stanza version, Cloris’s opening complaint is set in dialogue with one from Amintas, whose death has been only a “false report”, and who comes across her in a Romeo and Juliet-like scenario; in the full four stanzas, both lovers are revived, showing that “true love hath soul and life”. Twice’s collection contains only the first stanza, rendering it an affective female-voiced complaint, in which Cloris’s sighs and tears are set to falling notes punctuated by rests, creating veritable musical sighs.Footnote13 It is impossible to know whether the transcription of only the first stanza in Twice’s collection is a feminocentric choice, taking Cloris’s point of view as a female speaker, and crafting a straightforwardly female-voiced love complaint out of the dialogue poem for a woman’s soprano practice and performance. It is perhaps significant that Elizabeth Davenant’s collection also contains only this first stanza, as does the virginals book of Elizabeth Rogers, although other manuscripts reproducing only the first stanza have no clear association with women as transcribers, compilers, or users of the song collections.Footnote14

As Scott Trudell has observed, composers of airs in the early seventeenth century experimented increasingly with the performance of gender, and set over 30 “female persona” lyrics to music.Footnote15 “Cloris sighed and sung and wept” is one such lyric, as is another lyric once shared by Twice (now in the “Table” only) and Davenant, “Shall I weep or shall I sing?”, an anonymous lyric later published as “A Maiden’s Complaint” in Wits Interpreter (1655). These aside, however, Twice’s song collection is catholic in its selection of male- and female-persona lyrics, as well as those in which the persona is of indeterminate gender. Its compilation of amorous lyrics shows little evidence of prioritizing representations of female eloquence or a female point of view, and it is consistent in this with other women’s song collections from the period. Compilation practices in manuscript songbooks associated with women seem in this way to accord with Erin McCarthy’s findings on women’s compilations of John Donne’s poetry: that early modern women’s selections of poems and genres “are broadly consistent with men’s”.Footnote16 Anne Twice’s book, indeed, once contained a musical setting of Donne’s “Sweetest love, I do not go” (now in the Table only, as Song xxxvii).Footnote17 Other male persona love lyrics in her volume include “Wrong not, dear empress of my heart” (as Song xxviii), later printed in Wits Interpreter (1655) with the title “To his Mistresse by Sir Walter Raleigh”;Footnote18 and John Dowland’s “Rest awhile, you cruel cares” (as Song xl), a thoroughly Petrarchan lyric in which the speaker addresses Laura, “queen of my delight”. Alongside such male-persona lyrics are existential complaints of a kind also prevalent in the repertoire of early seventeenth-century airs, in which the speaker has no markers of gender. “Down, afflicted soul, and pay thy due” (Song xlvi), for example, is a woeful evocation of worldly sinfulness with an evocatively descending and melancholy setting.Footnote19 Another song in this vein is “As life, what is so sweet?” (Song xii, now in the “Table” only), a devotionally-inflected lyric evoking the deaths of a wounded hart, a worm, a dove, and a swan, set to music by William Webb; this lyric and setting also occur in Elizabeth Davenant’s collection.Footnote20

Alongside the stand-alone airs, Drexel MS 4175 has proven to be a key source for songs connected to Jacobean dramatic and masquing culture. “Anne Twice, Her Booke” was one of three musical commonplace books acquired by the New York Public Library from the musicologist Edward Francis Rimbault in June 1877; all three are important sources for early seventeenth-century dramatic songs.Footnote21 Drexel MS 4175 contains “Come away, Hecate”, the song from Thomas Middleton’s The Witch that influenced Shakespeare’s Macbeth but was not printed until William Davenant’s operatic rewriting of it in 1673/4.Footnote22 The song is one of many in the manuscript certainly or almost certainly by Robert Johnson, who was writing for theatre productions and court masques between about 1607 and 1623. Other Johnson (or likely Johnson) settings in the collection are: “Oh, let us howl some heavy note”, the madman’s song from Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi (1613); “Dear, do not your fair beauty wrong” from Thomas May’s The Old Couple (1615); “Tell me, dearest, what is love”, from Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Captain (c. 1611); and “Have you seen the bright lily grow?” from Jonson’s The Devil is an Asse (1616).Footnote23 Dramatic songs in the manuscript that are not by Robert Johnson are: “Get you hence, for I must go” from Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale (1610/11), rearranged from a three-voice part song into a solo air; “Cupid is Venus’ only joy”, from Thomas Middleton’s A Chaste Maid in Cheapside (1613) and More Dissemblers Besides Women (1615); and “Heare ye, ladies that despise”, from John Fletcher’s Valentinian (1614). Of these, “Cupid is Venus’ only joy” and “Have you seen the bright lily grow?” were originally present in the Drexel collection in two copies, one for viol accompaniment, one for lute.

It is these dramatic songs that have received most attention, and been the focus of discussion so far of what the manuscript reveals about a young woman’s cultural engagements. How Anne Twice acquired her songs is unknown, but Ian Spink expressed surprise in 1962 at “a musical up-to-dateness and discernment that one does not, even today, associate with young ladies of Gloucester”.Footnote24 The comparable collection of Elizabeth Davenant indicates that a keen interest in and access to the songs of Jacobean dramatic culture was not unprecedented for young women compilers.Footnote25 Davenant also has “Have you seen the bright lily grow?” from Jonson’s The Devil is an Asse; this song, along with “Like to the damask rose”, “Cloris sung and sighed and wept”, “As life, what is so sweete?”, and “A Maiden’s Complaint”, is the repertoire that the two manuscripts have in common. Davenant includes a different song from John Fletcher’s Valentinian (1614), “Care-charming sleep, thou easer of all woes”, and her manuscript also contains “Woods, rocks, and mountains”, a female persona complaint that has in recent years been claimed for Shakespeare and Fletcher’s now-lost play, Cardenio.Footnote26 One further dramatic lyric compiled by Davenant is “Go, happy hart, for thou shalt lye”, John Wilson’s setting of the lyric from Fletcher’s The Mad Lover (1617). We have biographical information for Elizabeth Davenant that gives context to the compilation of her book: her pedigree is theatrical, as the sister of the playwright William, and perhaps more importantly, the daughter of a father who was “an admirer and lover of plays and playmakers”, according to Anthony Wood.Footnote27 Elizabeth Davenant was living at her father’s home, the well-known Tavern at Cornmarket in Oxford, at the time of his death in 1621/2, and Oxford was no doubt the centre of far more manuscript circulation than Anne Twice’s provincial Gloucestershire. But Elizabeth Davenant and Anne Twice are two women who collected – or had collected for them – the theatrical songs and up-to-the-minute airs of their day, and who are likely to have done so as unmarried girls.Footnote28

Most of the detailed musicological work on Drexel MS 4175 that enables us to identify Anne Twice’s songs dates from the 1950s to 1980s, and focuses on its connections to the theatre; Cutts suggests that “undoubtedly the chief interest of the manuscript will always lie” in the dramatic songs it preserves.Footnote29 The tides of scholarly change, however, mean that it is now of greatest interest as a woman’s song book: for what it tells us about girls’ and women’s engagement with air culture as compilers, collectors, pupils, practitioners, and performers – even, at times, as writers and composers. The inscription of Twice’s name on the book suggests her agency in at least one and quite likely many of these capacities, whether or not it is transcribed in her own hand.

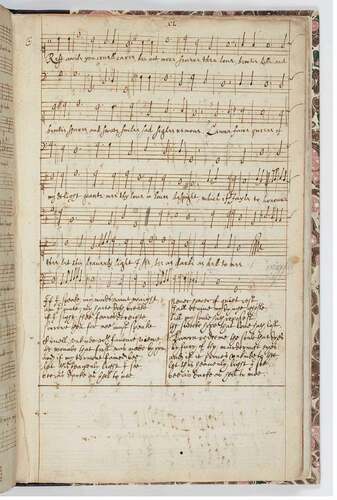

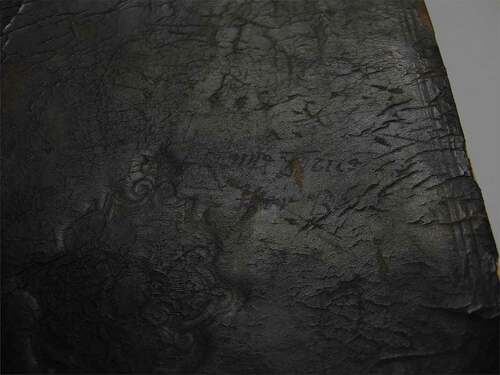

We do, however, think it is reasonably likely that her hand is represented. The song collection is in two hands. Up until Song xxix, all of the songs’ first stanzas, written in-line, and any additional stanzas written under the staves, are in a secretary hand that we have labeled Hand B. Songs xxx-xxxix are now missing from the manuscript, but when the extant songs resume at Song xl, many of the in-line lyrics are in a tidy italic hand that we have labelled Hand A. Any additional stanzas written below the staves, however, continue always to be in the secretary hand. This means that some transcriptions from Song xl onwards are collaborations, with the first verse in-line, in Hand A, and the subsequent stanzas in Hand B (see : Song xl). The italic hand is, in our reading, the same as that of the title “Songs vnto the violl and lute” on the manuscript’s first folio; hence Hand A (see ). It is tempting to surmise that Hand A, the tidy italic of a kind commonly used by women, is Anne Twice’s own, and that her secretary-handed collaborator is a male music tutor: it would make sense for such a common context for songbook compilation to be materialized on the page. Neither Hand A nor Hand B is responsible for “Anne Twice, Her Booke” on the original outside cover of the volume ().Footnote30 This, we believe, is the hand of Twice’s cousin, she or he who has also written inside the volume, “my Cosen Twice Leffte this Booke with me when she went to Broistl which is to be returne to her AGhaine when she Come to Glost” (see ).Footnote31 The “her book” formulation is most commonly used by book owners themselves to mark their possessions, referring to themselves in the third person; however, in this instance, it seems to be an acknowledgement of another’s ownership, likely to have been made at the same time as the more detailed description of the lending scenario on the first page.

Within the Drexel manuscript’s song collection alone, then, there are several participants, their hands evincing the sociality of song compilation and performance within the sphere of domestic music-making and tuition, compilation, and exchange. These intertwined lyric and music practices are echoed in other women’s songbooks of the period, from the 1620s, when the career of a composer such as Henry Lawes was young, through to at least the 1650s, when Lawes presided over music meetings in republican London, and set several Katherine Philips lyrics to music. Elizabeth Davenant’s songbook is marked by another woman user: in the margins of “Cloris sighed and sung and wept”, the first song in her collection, a note records that “Kath: Low: May ye 6th 1663 began my excerpts” (fol. 1r). A. B. Pearson has conjectured that “Kath Low” may be the daughter of Edward Lowe, the organist at Christ Church, Oxford, from 1630, who was himself responsible for several manuscripts of early seventeenth-century songs.Footnote32 The songbook of the Scottish gentlewoman Lady Margaret Wemyss, dating from the 1640s, also illustrates the communal nature of song compilation, practice, and exchange. Wemyss compiled her songbook from the age of 12 in 1643, until her death at the age of 18 in 1649; that is, during her girlhood, and most likely in association with a music tutor. At the bottom of one page, she notes that “all the Lesons behind this are learned out of my sisteres book” (fol. 42r) .Footnote33 Wemyss’s songbook was preserved in the papers of her sister Jean’s marital family, suggesting that the same sister from whom she copied her lessons took possession of Margaret’s music book after her death.Footnote34 Each of these examples, including Twice’s, attests to domestic contexts of music tuition, practice, performance, and exchange – and to women’s multiple engagements in these activities. All of these extend into the later decades of the seventeenth century, in which Katherine Philips and her friends were active in circles of lyric and musical exchange.

The song collection in Anne Twice’s manuscript can, then, be seen to evince an earlier version of the circulation and compilation of lyric and song, together, that marks the 1650s coteries, circles, and networks of Katherine Philips. Henry Lawes, whose very early composition “Like to the damask rose” is in the Twice and Davenant manuscripts, was employed as a music tutor to the Bridgewater family in the 1630s, schooling their daughter Alice Egerton alongside her sisters and brothers (and writing as a result the songs for Milton’s Comus, in which Alice played The Lady). After a hiatus from 1622 to 1652 (broken only by Walter Porter’s Madrigals and Ayres in 1632), the print publication of English books of airs resumed in the 1650s, including Henry Lawes’s first book of Ayres and Dialogues (1653), which he dedicated to Alice and her sister Mary, both then married, as Alice, Countess of Carbery and Mary, Lady Herbert of Cherbury and Castle-Island. Lawes’s dedication looks back to his years of employment by their parents as precisely the kind of music tutor that Anne Twice may have had: “no sooner I thought of making these Publick, than of inscribing them to Your Ladiships, most of them being Composed when I was employed by Your ever Honour’d Parents to attend Your Ladishipp’s Education in Musick; who (as in other Accomplishments fit for Persons of Your Quality) excell’d most Ladies, especially in Vocall Musick”. And in the 1650s, during the years of Cromwell’s rule, Lawes presided over music meetings in London in which Katherine Philips may have taken part, and set at least four of Philips’s poems to music.Footnote35 Lyric and musical practices – written and unwritten poetry – are intertwined in these contexts, in which girls and women were highly active, and in which, by the pinnacle of Philips’s career, women took on agency as writers and composers.Footnote36 Women’s songbook compilation and practice in the 1620s is part of a continuum with the lyric coteries and song performance circles of the 1650s, with recreative practices of selection, transcription, adaptation, and performance connecting the two.Footnote37 Certainly, Philips’s musical connections and the possibilities of lyric performance seem to be among the qualities celebrated in the previously unnoticed lyric in the middle of the Drexel manuscript that celebrates her, “Presenting a Book to Orinda”. Whoever penned the poem, it speaks to later seventeenth-century circles of lyric exchange in manuscript and song that are prefigured by Anne Twice’s collection earlier in the volume.

“Presenting a Book to Orinda” and other poems

Following the end of the songbook comes a small verse miscellany that consists of five poems in two different hands.Footnote38 Neither of these hands are identifiable, nor do they match those in the songbook, though the main hand represented in the verse miscellany may also have written the recipes that follow it, reversed, in the manuscript. The verse miscellany is the beginning of the “much later seventeenth-century material” that Cutts notes, but sets aside, in his musicological inquiry into the manuscript.Footnote39 The poems appear to date to the 1680s or possibly to the late 1670s. Alongside the recipes and account book towards the end of the manuscript, the verse miscellany might seem an expedient use of spare paper, disconnected in person and place from Anne Twice’s songbook. In spite of their temporal remove, however, each collection reflects the nexus between amorous lyric and song that existed in domestic contexts and in which women were active participants. The fourth poem in the miscellany, “Presenting a Book to Orinda”, especially calls us to attend to the complementarity of these sections. This undiscovered reception of Katherine Philips – probably the most prominent seventeenth-century woman poet writing in English – depicts her at the heart of overlapping networks of poetry and musical performance.

Katherine Philips’s career made visible and thinkable the category of the “woman writer”, serving as template and temple for the women who saw themselves as following in her footsteps.Footnote40 In his Theatrum Poetarum (1675), Edward Phillips describes her as “the most applauded, at this time, Poetess of our nation, either of the present or former Ages”, and singles out her ability to appeal in a “style suitable to the humour and Genius of these times”.Footnote41 Similarly Richard Baxter in his Poetical Fragments (1681) names her one of the “Excellent Poets” of “These Times”.Footnote42 But the “times” each refer to are not those of Katherine Philips herself, who had died of smallpox years earlier, in 1664. Philips gained prominence towards the end of her life for Pompey, her translation and adaptation of Pierre Corneille’s La Mort de Pompée that was performed in Dublin in February 1663 and published in Dublin and London later that year. In 1664, a collection of her poems was published, probably without her authorization. But for many of her admirers her influence was a posthumous one. Philips’s reputation continued to grow, peaking in the 1670s and 1680s after the 1667, 1669, and 1678 reissues of her poetry. It is to these later decades that “Presenting a Book to Orinda” belongs, and as in Edward Phillips’s description in Theatrum Poetarum, the poem situates her work and life in in the present tense of Orinda’s enduring legacy.

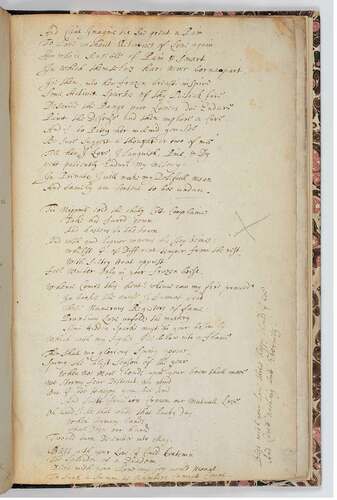

“Presenting a Book to Orinda” (see ) is a significant addition to the corpus of poems written in praise of Katherine Philips. The posthumous Poems (1667) is prefaced by seven commendatory poems: four that date from earlier in Philips’s career, by the earls of Orrery and Roscommon, Abraham Cowley, and Philo-Philippa; and three that clearly postdate her death, by Abraham Cowley (again), Thomas Flatman, and James Tyrrell.Footnote43 Her poetry was lauded by James Gardiner and Henry Vaughan in the 1660s, by Edward Phillips in 1675 and “Ephelia” in 1679, and by Richard Baxter in 1681; others praised her piety and virtue.Footnote44 Anne Killigrew and Jane Barker are among the women poets who celebrated Philips in verse, as did John Oldham, as we discuss below.Footnote45 Foremost, and fittingly for Philips’s reputation, the new poem in Drexel MS 4175 captures a moment of textual circulation: gifting a book of verses. Katherine Philips circulated her works widely in manuscript among her network of acquaintances; many of her poems involve, or construct, intimate addresses between her circle of friends, and she is often recognized today as a writer of friendship poems.Footnote46 Even before the print publication of her poems, she was acknowledged in Jeremy Taylor’s A Discourse of the Nature, Offices and Measures of Friendship (1657) as “you who are so eminent in friendships”.Footnote47 “Presenting a Book to Orinda” speaks to this established reputation, as the speaker hopes the eponymous book will become “prifer’d” as “The blest Companion of her Privacy”. The poem is flirtatious in its hopes that the gifted book “mayst kiss Orinda’s hand” and “mayst in her Closett lye”, but these images also reflect the speaker’s – and writer’s – desire to be included in the kind of exclusive network through which Philips and her coterie exchanged their writing. Philips’s “privacy” was crucial to maintaining her reputation, as in her repudiation of the 1664 printing of her poems where she describes herself as “that unfortunate person that cannot so much as think in private, that [I] must have my imaginations rifled and exposed”.Footnote48 “Presenting a Book to Orinda” balances its aspirations to enter into Philips’s “private” sphere against an approval for her careful, and carefully modest, management of her public reputation. The speaker’s desire to “kiss Orinda’s hand” may be “in vain”, but via the envoy of the gifted book the speaker nevertheless hopes to participate in the kind of intimate literary network Philips had come to represent.

The Drexel manuscript poem’s reception of Philips as a coterie poet is intriguing considering its dating and possible authorship. “Presenting a Book to Orinda” finds significant parallels in the early work of the satirist John Oldham (1653–1683). Oldham’s short poetic career began with a series of poems for local families in Shipton Moyne, in Gloucestershire, the same county in which the Drexel manuscript’s inscription tells us Anne Twice lived. In 1674, Oldham returned home from Oxford without a degree. He wrote an elegy to a local widow upon the death of her daughter, titled “On the death of Mrs. Katharine Kingscote a Child of Excellent Parts and Piety”. In 1675, he wrote another, much longer elegy on the death of his university friend, Charles Morwent. And, in 1676, “cherishing hopes of notice at Court”, he wrote “Presenting a Book to Cosmelia” to an attendant of Princess Mary who was, according to the poem’s full title, “responsible for Princess Mary’s hair”.Footnote49 As the edition in the Appendix to this article shows, these three poems are echoed extensively in “Presenting a Book to Orinda”, aligning with Oldham’s “habit of repeating turns of thought and phrase from earlier compositions in later ones, particularly if the earlier were unpublished”.Footnote50 None of these three source poems were published in Oldham’s lifetime, pointing to exactly the culture of manuscript circulation in which “Presenting a Book to Orinda” is also to be found.Footnote51

It is possible, then, that “Presenting a Book to Orinda” is an undiscovered Oldham poem in which he reprises previous works, perhaps in response to the new edition of Philips’s poems published in 1678. If so, it would not be the only Oldham poem to praise Philips. In his poem “Bion” (published in 1681), he styles her as “soft Orinda whose bright shining name/Stands next great Sappho’s in the ranks of fame” at the end of a list of greats including Chaucer, Milton, Cowley, and Denham.Footnote52 Moreover the editors of Oldham’s collected works, Harold F. Brooks and Raman Selden, identify multiple references to works memorializing Philips in his other poems, including from Cowley’s “On the death of Mrs. Katherine Philips” and “On Orinda’s Poems” and Thomas Flatman’s “To the Memory of the Incomparable Orinda”.Footnote53 Though not definitive, then, there is sufficient evidence to posit that Oldham, who approved of Philips (and the poets who praised her), might also be the author of the poem in Drexel MS 4175. This would make it somewhat earlier than the other dateable poem in the miscellany, “To a Lady who say’d there was noe Such thing as Love”, which uses lines from Thomas Creech’s Lucretius translation, first published in 1682.Footnote54 If Oldham is the Orinda poem’s author and if he wrote it in the late 1670s or early 1680s, it would seem to reflect his own ambitions and circumstances. At this time he had returned from Oxford to rural Gloucestershire and was a jobbing tutor writing poems to possible patrons. “Presenting a Book to Orinda” then evokes through the figure of Philips the kind of literary and cultural network to which Oldham was aspiring; indeed its primary antecedent, “Cosmelia”, was intended to ingratiate him with just such a network.

It is also possible that the author of “Presenting a Book to Orinda” was simply a close reader of Oldham’s poems. The three source poems would likely have circulated among friends and neighbours in the 1670s. However, there is no evidence that those poems were circulated together and each address what appear to be discrete audiences (local families, his Oxford set, the court). If Oldham is not the author, it seems more likely that the poem was written by an attentive reader of the posthumous 1684 edition of The works of Mr. John Oldham, together with his Remains, the first publication to contain all three source poems. This would fit the mid-1680s dating of “To a Lady who say’d there was noe Such thing as Love”. Interestingly, the presence of catchwords (‘And Can’t) at the end of folio 19v suggests “Presenting a Book to Orinda” was transcribed from elsewhere, either from a draft or from another source, possibly suggesting the poem is not unique to Drexel MS 4175. Oldham is best known for his satires, but if he is not the author, then it suggests at least one of his contemporaries found his early works compelling.

While a late dating for “Presenting a Book to Orinda” fits with what we know about Philips and her enduring reputation, it does make somewhat unusual the poem’s present-tense courtly flattery. While Flatman’s elegy announces “ORINDA’s Dead” and Cowley’s begins “Cruel disease!”, the Drexel manuscript poem instead appears to situate itself in the height of Philips’s living fame in the early 1660s. Here Philips is not only alive but her future is yet to be determined – and the speaker is determined that it should involve “a thought or two of mee”. In its honeyed tone the poem most closely resembles the similarly titled “Presenting a Book to Cosmelia”, even when it takes images from the elegy on Katharine Kingscote, its other major source. Borrowings from that elegy, such as the phrase “Epitome of Womankind”, are redirected from memorial to blandishment. Lines from both “Cosmelia” and the elegy to Charles Morwent, such as those that describe “The scatter’d glories of her lovely sex/In her bright soul as in their Center mix”, demonstrate just how compatible the rhetorical strategies of elegy and encomium can be. There are also echoes of Philips’s “Lucasia”, which reads: “So vertue, though in scatter’d pieces ‘twas’/Is by her mind made one rich usefull masse”.Footnote55 “Presenting a Book to Orinda” elaborates the courtly mode of “Cosmelia”, using the specifics of Katherine Philips’s career to give a finer point to that more formulaic effort. But it is striking that her career is presented as a live concern; even a decade after her death, Philips’s must have felt relevant enough to address in an entreating present tense.

If, then, Orinda lives on in this poem, what is she like? The speaker praises her religious zeal, her gifts of “nature Grace, Witt & Art” but also the “Exact Pattern of true Poetry” she leaves to “Degenerate Posterity”. These flatteries are conventional, and like so many encomia of the period, the poem appeals not to the actual addressee but to other readers who might approve their rhetorical performance. Part of that performance here is the careful acknowledgement of Katherine Philips’s literary and intellectual achievements. The eponymous book acts as envoy for the speaker’s petition (“Tell her I love, I Languish, Pine & Dy”), but here, without the male writer’s usual monopoly on poetic mastery, its success is in doubt. “But think not to inform her knowing mind”, the speaker warns, predicting that his gift will elicit correction as much as compliment: “Her charming tongue thy numbers will reherse/And add new graces to thy well tun’d verse”. Philips is received in this poem not only as a “saint” (as Paul Salzman characterizes her reputation), nor only as a poet, but also as a musician.Footnote56 When the speaker imagines her “rehers[ing]” its “numbers” out loud, he evokes not only prosody on the page – the mental recitation of metrical feet – but musical rhythm and harmony in the performance of a “charming tongue”. The gifted book is already “well tun’d” but Orinda’s performance will improve it. This section has no precedent in Oldham’s other poems – it was written specifically in praise of Philips. These lines suggest that more than a decade after her death, Philip’s legacy was not only ascendant, but nuanced.

The appearance of “Presenting a Book to Orinda” alongside the musical compilation in Drexel MS 4175 is particularly striking because Philips, too, lived at the intersection of poetic and musical culture. Not only did she engage directly with song lyrics herself, adapting French court airs to mark the acts of Pompey and translating at least one Italian song, but her poetry was often received by way of its many musical settings, most famously by Henry Lawes.Footnote57 This poem is not the first appearance of Philips’s coterie in the Drexel manuscript; not only does the songbook contain Lawes’s setting for “Like to the damask rose” but he would later provide an alternate setting to another, “Fi fi fi what doe you”.Footnote58 “Presenting a Book to Orinda” bridges the chronological gap between the songbook and the verse miscellany, as well as the gap scholarship has perceived between musical and poetic culture; these were intersecting spheres in which women like Philips and Twice participated alongside men like Lawes and, perhaps, Oldham.

Though only “Presenting a Book to Orinda” suggests a possible attribution to John Oldham, the other four poems in the Drexel MS 4175 verse miscellany are very much in keeping with it. Like most of the songs compiled in the first part of the manuscript, the verse miscellany is a collection of love lyrics. Three of the five poems feature a character called “Silvia”, a commonplace pastoral name popularized by Torquato Tasso’s play Aminta, first published in 1573. The name then appears in several ballads and poetry collections where she is the subject of male praise, petitions, and laments. Tasso, and by extension Silvia, enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1670s and 80s. This fits with the most direct evidence of dating in the miscellany, namely the reference in the first poem to Thomas Creech’s translation of Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura, which was first published in 1682, and broadly with the period in which John Oldham or an admirer could have written “Presenting a Book to Orinda”. The verse miscellany therefore appears to offer a zeitgeist of lyrics from the 1670s and 80s just as the songs do for the 1620s and 30s.

This first poem, “To a Lady who say’d there was noe Such thing as Love”, initially follows Creech’s translation of Lucretius’s invocation to Venus and describes Love as the generative principle of the universe, “To whose kind power all Creatures owe their birth”. Lucretius invokes Venus because sex is an apt analogy for his atomistic description of the nature of things; the conjunction of atoms brings forth matter just as intercourse brings forth offspring. In “To A Lady”, however, that philosophical discourse is instead used to encourage the addressee, “Dear Silvia”, to accept the speaker’s attentions. What “some Call passion by too nice a name” is, he argues, merely the “proper use” of man’s “Appetite”, which “[i]s borne with us and therefore naturall”. Illicit sex is naturalized, too by the description of “Active Spirits” entering through the eye to the heart and inflaming the blood when the “Lovely object comes in View”. This Galenic depiction of sight offers a nod to the didactic purpose of Lucretius’s poem but again buttresses the speaker’s suasive strategy. If she would only drop her unscientific objections, Silvia could cure the speaker’s affliction by requiting his love.

The narrative appears to continue in the following poem, “A New yeares Gift”, where the addressee “Dear Silvia” becomes “Dear Cruell Silvia”. The speaker heralds the new year with well wishes for his beloved – in so far as she in turn treats him well. As in “Orinda”, the beloved here is indifferent to romantic love (“For Love with her’s a pure lambent flame”). Silvia’s love “mounts towards the Heaven whence it came”, just as Orinda’s “mind is soe much fix’d on things above”. But that does not stop the speaker wishing it were otherwise. In this context the speaker’s desire for her to experience “untasted joys”, “new blisse” and “blessings [to] Equalize her Innocence” take on a somewhat sinister tone and align closely with the seduction strategy in the preceding “To a Lady”. What he wishes for is “Pleasure refin’d from the Allay of Smart”, but as the only smarting described is the speaker’s rejection, the titular “Gift” appears to be one the speaker seeks to elicit from, rather than give to, Silvia. Dubious of his prospects, though, the speaker ultimately comforts “wretched me” that no other mortal could obtain the “transcendent Happiness” of her love either.

The third poem is written in a different hand, but it continues the narrative of the preceding poems, suggesting a collaborative poetic practice. The male speaker is absent, perhaps because he has now obtained his goal; instead we see “Relenting Silvia” in pastoral surroundings, repenting her loss of chastity. The turn to Silvia’s perspective at this moment coincides with a change in scribes, suggesting an attempt to imagine the consequences of those amorous appeals. Male pleading is replaced by female complaint tropes of regret and reputational injury that resemble texts from the songbook that reckon with unchecked male desire, like “Fi fi what doe you”. Silvia does not directly blame herself or her lover, but inveighs against other women, “each beautious shee”, who was able to successfully guard their chastity with hearts “remorseles as these Rocks”. And yet it is these rocks that she then elects as her “monitors of constancy” while she herself pledges to become a “myrroir of chast Love”. “Presenting a Book to Orinda” follows this triplet of poems and, as we have suggested, revises their themes of amorous petition but situates them in relation to Philip’s particular person and her career. The last, untitled poem returns to the conventional as it looks forward to the “glorious Spring” where the speaker’s feelings will be reciprocated by the unnamed beloved.

Like the collection of songs that precedes it, then, this miscellany offers a cohesive set of primarily amorous lyrics. The two different hands entail not a divergence in mode or interest, but collaboration and experimentation in the literary performance of gender. The verse miscellany is of a piece with the songbook that immediately precedes it; both are characterized by the shifting amorous perspectives drawn from Petrarchan and pastoral traditions that were popular in the writing and performances of men and women across the seventeenth century. While the recipe book that follows is reversed and runs from the back of volume, the first two sections of the manuscript – Anne Twice’s song collection and the five-poem verse miscellany – are in the same orientation, suggesting they may have been seen as contiguous or complementary to each other. While the verse miscellany reaches backwards in time through the address to Katherine Philips, the songbook reaches forward by capturing an early work of Lawes, who would become one of her key collaborators. We are, then, able to read the first two sections of the Drexel manuscript in ways suggested by Adam Smyth, building on the work of Joshua Eckhardt, according to “a hermeneutics of compilation-effects”. Even though two sets of hands and two time periods are at play, the diachronic compilation of the manuscript volume “creates new sequences whose effects need to be understood on their own terms” and that, in this case, reveal much about lyric and song culture, its actors and agents, and continuities in its practice and performance from the 1620s through to the 1680s.Footnote59

Paying attention to the five poems at the centre of Drexel MS 4175, and their diachronic relationship to the manuscript’s song collection, recasts the ways in which the volume documents seventeenth-century lyric culture, at the same time as it presents a striking new poem in praise of Katherine Philips. In both its material form and its content Drexel MS 4175 calls us to attend to the nexus between lyric poetry and air singing and to how that nexus persisted in early modern household contexts as an enduring site of cultural praxis for both men and women. The song collection that has been associated with Anne Twice, dating from the 1620s, is not only an important source for airs from Jacobean dramatic culture, but provides an intimate insight into practices of song selection by or for young women, drawing on a diverse range of popular songs circulating in manuscript and print. “Presenting a Book to Orinda” adds further to our sense of Katherine Philips’s already extensive posthumous poetic reputation, depicting her as the “Exact Pattern of true Poetry” and placing her at the heart of overlapping networks of poetry and musical performance. Philips’s engagement with her Society of Friends, the musical circles of Henry Lawes, and the Dublin theatre community in which she undertook her translations of Pompey are well documented. So, too, is the esteem in which John Oldham held her, and the “new” poem suggests a poetic afterlife in ongoing circles of poetic manuscript exchange involving Oldham and his readers in the 1670s and 1680s. If the poem is indeed by Oldham, it is a notable addition to his known oeuvre.

More work remains to be done on this intriguing manuscript and its documentation of seventeenth-century cultural life and women’s worlds. Most obviously, the recipes and accounts remain for the most part unexamined. The volume’s reuse for multiple purposes, across several decades, echoes what we know of many domestic manuscript books from the period. Receipt books, or books containing receipts, are frequently diachronic and multi-modal, passed from one generation to another.Footnote60 As Wendy Wall describes, they are “indispensable tools for refining our understanding of early modern science, medicine, food, labour, women’s history, material book studies, social networks, and women’s writing”.Footnote61 Just as the verse miscellany and its celebration of Katherine Philips does for the volume’s representation of lyric and song culture, so the remaining contents of Drexel MS 4175 have the potential to refine further our understanding of the intersections between household spaces and women’s intellectual and practical lives, their modes of knowledge and enquiry, social networks, and recreative engagement with cultures of transcription and commonplacing, household manufacture, and performance.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elizabeth Hageman and Paul Hammond for their generous comments on drafts of this article. All errors are of course our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. New York Public Library, Drexel MS 4175. A facsimile edition is available in Jorgens, ed., English Song, vol. 11 (facsimile) and 12 (texts), and the manuscript has been digitized as part of the The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1620–1630; see <https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8902dfcb-72a8-ed00-e040-e00a18067333>.

2. The manuscript is missing multiple leaves and has not been foliated. We have introduced our own foliation for ease of reference, but follow previous scholars in referring to the songs in the first part of the book according to their original numbering.

3. Spink, “Ann Twice, Her Booke”, 316.

4. The most detailed study of the song collection is Cutts, “‘Songs Vnto the Violl”.

5. On early modern women’s lyric poetry and song, important studies include Larson, The Matter of Song; Dunn and Larson, Gender and Song; and Linda Phyllis Austern’s groundbreaking work, including “The Conjuncture of Word”. On recipes see, for example, DiMeo and Pennell, eds., Reading and Writing Recipe Books; Wall, Recipes for Thought; and Leong, Recipes and Everyday Knowledge.

6. Two other recent studies explore the compilation of poems by Philips in verse miscellanies in the 1680s; see Smyth, “Thinking with Ferrar Papers”, and Challinor, “A New Manuscript Compilation”.

7. See Trudell, “Performing Women”; Larson, The Matter of Song, 79.

8. Trudell, “Performing Women”, 15 and 17; and Doughtie, ed., Lyrics from English Airs, 10.

9. On poetic miscellanies and song, see O’Callaghan, Crafting Poetry Anthologies.

10. Jorgens, ed., English Song, 11:vii–viii.

11. Elizabeth Davenant’s manuscript is Oxford, Christ Church Library, MS 87. A facsimile edition is available in Jorgens, ed., English Song, vol. 7.

12. See Jorgens, ed., English Song, 12:385.

13. Lois Marshall performs the setting at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2HFHISQIVGU> [accessed 22 October 2020]. It is also performed in Ockenden and Eynde, Elizabeth Davenant, Her Songes.

14. Elizabeth Rogers’s virginals book is British Library, Additional MS 10337, fols 21v–22r; and see Jorgens, ed., English Song, vol. 2.

15. Trudell, “Performing Women”, 15 and 17.

16. McCarthy, “Reading Women Reading Donne”, abstract.

17. Another lyric in the manuscript, ‘Wherefore peep’st thou, envious day?’ (Song lvii), has sometimes been attributed to Donne, but his authorship is doubtful; Jorgens, ed., English Song, 12:543.

18. The lyric has been variously attributed to Ralegh, or to the Scottish poet and courtier Robert Ayton; Jorgens, ed., English Song, 12:550.

19. Jorgens, ed., English Song, 12:60 and 12:402. For discussion of the musical setting, see Walls, “‘Music and Sweet Poetry’?”, 248–49.

20. Jorgens, ed., English Song, 12:14 and 12:368. Christ Church Library, MS 87, fol. 7r.

21. The other two manuscripts are now Drexel MS 4257, John Gamble, “His booke, amen 1659”, and Drexel MS 4041. See Cutts, “The Original Music”, 205–6, and “An Unpublished Contemporary Setting”, 86–89.

22. Cutts, “The Original Music”, 205–6.

23. Cutts, “An Unpublished Contemporary Setting”, 86. For the “dismal setting” of the madman’s song from Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi, see Walls, “‘Music and Sweet Poetry’?”, 248–49.

24. Spink, “Ann Twice”, 316.

25. See, however, Jorgens’s sharp warning against assuming a direct connection with the theatre: she argues that Davenant’s manuscript shows “some familiarity with the period’s drama but not necessarily with the music used in dramatic performances”, English Song, 7:vi.

26. See Cutts, “The Original Music”, 206; Taylor, “The History of The History”, 28–30.

27. Cutts, “‘Mris Elizabeth Davenant 1624’”, 27–8; Edmond, “Davenant [D’Avenant], Sir William”.

28. Elizabeth Davenant married Gabriel Bridges (B.D., fellow of Christ Church, Oxford, beneficed in the Vale of White Horse) at a date that is unknown (Cutts, “‘Mris Elizabeth Davenant 1624’”, 27–8). But her inscription of her maiden name in her book of songs in 1624 indicates that it was least begun as an artifact of compilation and practice within her natal family.

29. Cutts, “‘Songs Vnto the Violl’”, 6.

30. The manuscript has been rebound (in Hewit calfskin with hand-marbled paper slides and vellum corners), but the original covers are preserved with the manuscript.

31. Cutts believes the hand of Anne Twice’s cousin is the same hand that has recorded accounts on fol. 27v at the end of the manuscript, dated December 1699 (“‘Songs Vnto the Violl’”, 77). We do not think these two hands are the same.

32. See Cutts, “‘Mris Elizabeth Davenant 1624’”, 28; and Pearson, “Like to the Damask Rose”.

33. Wemyss’s songbook is National Library of Scotland, Dep. 314/23.

34. Spring, “Lady Margaret Wemyss Manuscript”, 6. MacKinnon, “‘I have now a book”, 45.

35. See Lawes, Second Booke of Ayres, sig. H1v; and Applegate, “An Unrecorded Musical Setting”. Settings for “A Dialogue between Lucasia and Orinda” and “To Mrs M. A. upon absence, 12 December 1650” are at present unlocated.

36. Lawes’s Second Booke of Ayres is dedicated to Katherine Philips’s school friend Mary Harvey, Lady Dering, and celebrates her achievements not only as a performer but also as a composer of airs.

37. See Toft, With Passionate Voice; and O’Callaghan, Crafting Poetry Anthologies.

38. In our foliation, the songbook runs fols. 1r–17v. The verse miscellany runs fols. 18v–20r.

39. Cutts, “‘Songs Vnto the Violl’”, 92.

40. Williamson, Raising Their Voices, 21.

41. Phillips, Theatrum poetarum, 257. On Katherine Philips’s posthumous reputation, see Salzman, Reading Early Modern Women’s Writing, 194–99.

42. Baxter, Poetical Fragments Heart-Imployment, sig. A4r.

43. See Wright, Producing Women’s Poetry, 137–38.

44. Collected Works of Katherine Philips, 1:23–27. Edmund Elys praised her as a pious influence on Cowley, and Robert Gould writes that “Her Verses and her Vertuous Life declare” the noble potential of womankind (ibid., 24–25).

45. Killigrew called Philips “Albions and her Sexes Grace” and wrote that “ev’ry Laurel, to her Laurel, bow’d” (“Upon the saying that my Verses were made by Another”, 1686). Jane Barker wrote that the Muses would help her to “reach fair Orindas height” (“The contract with the muses write on the bark of a shady ash-tree”, 1713). See Burke, “The Couplet and the Poem”, 280.

46. See, for example, the essays collected in Orvis and Paul, eds., The Noble Flame, and Anderson, Friendship’s Shadows. Other critics emphasize Philips’s political poems, such as Barash, English Women’s Poetry; Chalmers, Royalist Women Writers.

47. Taylor, A Discourse of Nature, 2. For more on her association with friendship, see Salzman, Reading Early Modern Women’s Writing, 176–87.

48. Philips, Poems, sig. A1v.

49. Poems of John Oldham, xxix.

50. Ibid., lxxiv.

51. “Presenting a Book to Cosmelia” appears first in Poems and translations by the author of the Satyrs upon the Jesuits (London, 1683). The remaining two poems are published first in the Remains of Mr. John Oldham in verse and prose (London, 1684).

52. Poems of John Oldham, 132.

53. Ibid., 122, 281, and 264 respectively.

54. The other poems in the verse miscellany are discussed in detail later.

55. Collected Works of Katherine Philips, 1:104–5, ll. 49–50.

56. Salzman, Reading Early Modern Women’s Writing, chapter 7.

57. For the French songs, see Cottegnies, “Katherine Philips’s French Translations”; for the Italian translation, see Hageman and Sununu, “New Manuscript Texts”, 203–5. Other musical settings of her poetry have been attributed, with varying degrees of certainty, to Henry Purcell, Charles Coleman, William King, Henry Hall, and the Duke of Monmouth.

58. Cutts, “‘Songs Vnto the Violl’”, 84, footnote 23; the settings are in what is now London, British Library, Additional MS 53723, fol. 7 (formerly B.M. Loan Ms. 35) and Paris Conservatoire, MS. Rés. 2489, fol. 18v.

59. Smyth, “Thinking with Ferrar Papers”, 213.

60. “Handed down to future generations as bequests or presented as tokens of affection, [recipes] were paper registers of bonds between people remote in time or space” (Wall, Recipes for Thought, 3).

61. Wall, “The World of Recipes”.

1 1.4–5] These rework the opening lines of Thomas Creech’s translation of Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura (1682), where the poet invokes Venus: “Delight of all, comfort of Sea and Earth; / To whose kind powers all Creatures owe their birth”.

2 1.7] The phrasing “my tunefull song” is also found in John Dryden’s translation of Lucretius (first published in Sylvae in 1685) though both may echo Creech’s “tuneful Voice”.

3 1.7] Silvia: a pastoral type, perhaps from Torquato Tasso’s Aminta.

4 1.23] mighty: MS reads mighly

5 1.31–2] See Aeneid 4.73, where Virgil compares Dido to a shot hind fleeing through the forest, unaware of her injury, ‘haeret lateri lethalis [h]arundo’.

6 2] Poems 2, 3, and 5 are marked with a cross in the right-hand margin; the ink does not match that of the poems.

7 2.13] See Dryden’s elegy to Anne Killigrew, “Ev’n Love (for Love sometimes her Muse exprest) / Was but a Lambent-flame which play’d about her Brest” (ll. 83–84), and cf. a similar sentiment in Poem 4.

8 2.14] cf. Poem 1, ‘I mount I mount’.

9 3] This poem is in a different hand from the other four.

10 3.4] See Herrick’s “Teares”, “Teares most prevail, with teares too thou mayst move / Rocks to relent, and coyest maids to love”. The asterisks link the later pronoun, “them”, (l. 6) with its referent.

11 3.6] monitors of constancy: the rocks supervise her conduct.

12 4.1] The opening imperatives mirror those in Oldham’s “Presenting a Book to Cosmelia”.

13 4.9-11] The brackets here mark out a tercet.

14 4.13] See Oldham’s “To the memory of my dear friend, Mr. Charles Morwent: A Pindarique” which reads “Teaching her numerous gifts to lie / Crampt in a short Epitome” (ll. 90–91); compare also his “On the Death of Mrs. Katherine Kingscote A Child of Excellent Parts and Piety”, “Never did yet so much Divinity / In such a small Compendium crouded lye” (ll. 28–29).

15 4.14–5] See “Cosmelia”, ll. 5–6, and similar in “Morwent”, “Thou wast a living System where were wrote / All those high Morals which in Books are sought” (ll. 547–48).

16 4.16–7] “Cosmelia” has the same except for “happy Sex” (ll. 21–22). See also similar in “Morwent”, “What Vertues […] /They all did in thy single Circle fall” (ll. 544–45). Katherine Philips’s “Lucasia” includes a similar image, “So vertue, though in scatter’d pieces ‘twas, / Is by her mind made one rich usefull masse” (ll. 49–50).

17 4.18–9] See “Cosmelia”, “She acts what they only in Pulpits prate, / And Theory to Practice does translate” (ll. 11-12).

18 4.20–2] Compare “Kingscote”, ll. 42-6, in particular “No word of hers e’er greeted any Ear, / But what a dying Saint confest might hear” (ll. 43–44).

19 4.24] Euchists: Messalians, members of an ascetic Christian movement originating in the Middle East in the 4th century.

20 4.24–5] Almost identical in “Cosmelia” (ll. 33–34) and “Morwent” (ll. 552–53), though both have “holy Hermits” (l. 33; l. 552).

21 4.28–9] See similar in “Morwent”, “So the bright Globe that rules the Skies, / […] Reserves his choicest Beams to grace his Set” (ll. 625-27). Oldham’s “David’s Lamentation for the Death of Saul and Jonathan, Paraphras’d” also has the phrase “with Natures choicest Dainties fed” (l. 164).

22 4.33] “Cosmelia” has “To tell how good the Sex was made at first” (l. 51).

23 4.33–6] Compare “Kingscote”, “Her Thoughts had scarcely ever sully’d been / By the least Foot-steps of Original Sin” (ll. 45–46).

24 4.36] Following this line and at the bottom of the page appears “And Can’t”, presented as catchwords.

25 5.1] Citt: a city-dweller, a term popular in the later seventeenth century (although also current earlier).

26 5.28-9] These last two lines are written rotated in the right hand margin.

Bibliography

- Anderson, P. Friendship’s Shadows. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013.

- Applegate, J. “Katherine Philips’s ‘Orinda upon Little Hector’: An Unrecorded Musical Setting by Henry Lawes”. English Manuscript Studies, 1100-1700 4 (1993): 272–280.

- Austern, L. P. “The Conjuncture of Word, Music, and Performance Practice in Philips’s Era”. In The Noble Flame of Katherine Philips: A Poetics of Culture, Politics, and Friendship, edited by D. L. Orvis and R. Singh Paul, 213–241. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 2015.

- Barash, C. English Women’s Poetry, 1649–1714: Politics, Community and Linguistic Authority. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Baxter, R. Poetical Fragments Heart-Imployment with God and It Self. London, 1681.

- Burke, V. E. “The Couplet and the Poem: Late Seventeenth-Century Women Reading Katherine Philips”. Women’s Writing 24, no. 3 (2017): 280–297.

- Challinor, J. “A New Manuscript Compilation of Katherine Philips: The Commonplace Book of Robert Mathewes”. The Library 17, no. 3 (2016): 287–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/library/17.3.287.

- Chalmers, H. Royalist Women Writers, 1650–1689. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Cottegnies, L. “Katherine Philips’s French Translations: Between Mediation and Appropriation”. Women’s Writing 23, no. 4 (2016): 445–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09699082.2016.1173345.

- Cutts, J. P. “An Unpublished Contemporary Setting of a Shakespeare Song”. Shakespeare Survey 9 (1956): 86–89.

- Cutts, J. P. “The Original Music to Middleton’s The Witch”. Shakespeare Quarterly 7, no. 2 (1956): 203–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2866439.

- Cutts, J. P. “‘Mris Elizabeth Davenant 1624’: Christ Church MS. Mus. 87”. The Review of English Studies 10, no. 37 (1959): 26–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/res/X.37.26.

- Cutts, J. P. “‘Songs Vnto the Violl and Lute’: Drexel MS 4175”. Musica Disciplina 16 (1962): 73–92.

- DiMeo, M., and S. Pennell. Reading and Writing Recipe Books, 1550–1800. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013.

- Doughtie, E., ed. Lyrics from English Airs 1596–1622. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970.

- Dunn, L. C., and K. R. Larson. Gender and Song in Early Modern England. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014.

- Edmond, M. “Davenant [D’Avenant], Sir William (1606–1668)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Hageman, E. H., and A. Sununu. “New Manuscript Texts of Katherine Philips, the ‘Matchless Orinda’”. English Manuscript Studies 4 (1993): 174–219.

- Jorgens, E. B., ed. English Song, 1600–1675: Facsimiles of Twenty-Six Manuscripts and an Edition of the Texts. Vol. 12. New York: Garland, 1987.

- Larson, K. R. The Matter of Song in Early Modern England: Texts in and of the Air. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Lawes, H. Second Booke of Ayres and Dialogues, for One, Two, and Three Voyces. London, 1655.

- Leong, E. Recipes and Everyday Knowledge: Medicine, Science, and the Household in Early Modern England. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

- MacKinnon, D. “‘I Have Now a Book of Songs of Her Writing’: Scottish Families, Orality, Literacy and the Transmission of Musical Culture c. 1500–c.1800”. In Finding the Family in Medieval and Early Modern Scotland, edited by E. Ewan and J. Nugent, 35–48. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008.

- McCarthy, E. A. “Reading Women Reading Donne in Manuscript and Printed Miscellanies: A Quantitative Approach”. The Review of English Studies 69, no. 291 (2018): 661–685. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/res/hgy018.

- O’Callaghan, M. Crafting Poetry Anthologies in Renaissance England: Early Modern Cultures of Recreation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Ockenden, R., and S. V. Eynde. Elizabeth Davenant, Her Songes. Ramée Records, 2011.

- Oldham, J. The Poems of John Oldham. Edited by Harold F. Brooks and Raman Selden. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Orvis, D. L., and R. S. Paul, eds. The Noble Flame of Katherine Philips: A Poetics of Culture, Politics, and Friendship. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 2015.

- Pearson, A. B. “Like to the Damask Rose”. Music & Letters 35, no. 2 (1954): 116–119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/XXXV.2.116.

- Philips, K. Poems by the Most Deservedly Admired Mrs. Katherine Philips, the Matchless Orinda. London, 1667.

- Philips, K. The Collected Works of Katherine Philips: The Matchless Orinda. Edited by Patrick Thomas. 3 vols. Stump Cross: Stump Cross Books, 1990.

- Phillips, E. Theatrum Poetarum. London, 1675.

- Salzman, P. Reading Early Modern Women’s Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Smyth, A. “Thinking with Ferrar Papers 1422: A c. 1681 Verse Miscellany”. The Library 21, no. 2 (2020): 192–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/library/21.2.192.

- Spink, I. “Ann Twice, Her Booke”. The Musical Times 103, no. 1431 (1962): 316. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/948800.

- Spring, M. “The Lady Margaret Wemyss Manuscript”. The Lute 27 (1987): 5–30.

- Taylor, G. “The History of The History of Cardenio”. In The Quest for Cardenio: Shakespeare, Fletcher, Cervantes, and the Lost Play, edited by D. Carnegie and G. Taylor, 11–61. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Taylor, J. A Discourse of Nature. London, 1657.

- Toft, R. With Passionate Voice: Re-Creative Singing in Sixteenth-Century England and Italy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Trudell, S. “Performing Women in English Books of Ayres”. In Gender and Song in Early Modern England, edited by L. C. Dunn and K. R. Larson, 15–29. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014.

- Wall, W. Recipes for Thought: Knowledge and Taste in the Early Modern English Kitchen. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

- Wall, W. “The World of Recipes: Intellectual Culture in and around the Seventeenth-Century Household”. In The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern Women’s Writing in English, 1540-1700, edited by D. Clarke, S. C. E. Ross, and E. Scott-Baumann. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Forthcoming.

- Walls, P. “‘Music and Sweet Poetry’? Verse for English Lute Song and Continuo Song”. Music & Letters 65, no. 3 (1984): 237–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/65.3.237.

- Williamson, M. L. Raising Their Voices: British Women Writers, 1650–1750. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1990.

- Wright, G. Producing Women’s Poetry, 1600-1730: Text and Paratext, Manuscript and Print. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Appendix

The Verse Miscellany in New York Public Library, Drexel MS 4175

Editorial policy: the following transcriptions are unmodernized, with original spelling, capitalization, and punctuation retained. We have silently omitted words or letters that have been scored out, and where capitalization is uncertain on account of indeterminate letter sizes, we have treated them as they would occur in modern sentence case.

[fol. 18v] [1] To a Lady who say’d there was noe Such thing as Love

[2] A New yeares GiftFootnote6

[3]Footnote9

[fol. 19v] [4] Presenting a Book to Orinda

[5]