ABSTRACT

This article examines the surprisingly prevalent incidence of contemporary handstamps impressed upon the final leaf of Restoration playbooks. These are all circular and contain either individual letters or are bisected and contain a combination of letters and numerals. As they are demonstrably not part of the printing process, they have not attracted the attention of textual editors; but as this article shows, neither are they markers of ownership that would interest scholars researching provenance. We identify the marks as being the stamps of letter receivers; in particular, receivers (James Magnes and Richard Bentley) who were also stationers involved in the publishing of the plays we examined. The presence of these stamps suggests that Magnes and Bentley served not only as publishers and booksellers, but as distributors of the playbooks they produced. The presence of these stamps thus has implications for the distribution of Restoration playbooks through the English postal system.

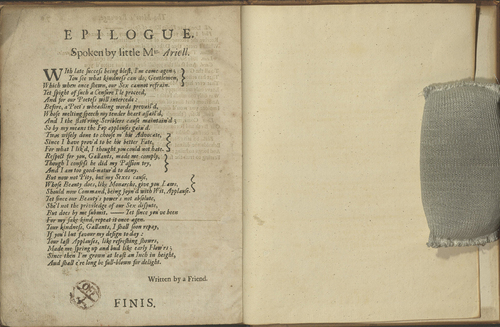

A curious post-publication phenomenon associated with Restoration playbooks is illustrated by the extant copies of Aphra Behn’s Abdelazer, or The Moor’s Revenge (LONDON, Printed for J. Magnes and R. Bentley, in Russel-street in Covent Garden, near the Piazza’s, 1677).Footnote1 The final leaf (which contains the Epilogue) of the copies held by the National Library of Scotland and the University of Edinburgh bears a circular ink stamp containing the letters ‘BE’; meanwhile, the four copies of the quarto held by the Folger Shakespeare Library, the British Library, the Beinecke Library at Yale and by the University of Akron also have a circular ink stamp in the same location, but theirs is a bisected circle featuring ‘OFF’ above the line and the numeral 4 below (see , below). Each example of the stamp is oriented and placed slightly differently on this same final page of Behn’s play, and is thus clearly stamped by hand (with differing degrees of inking), rather than printed. There are at least twenty-five extant copies of the Abdelazer quarto: the English Short Title Catalogue lists 22 copies but Cambridge actually has two (Brett-Smith.52 and Brett-Smith.53), as does the Bodleian (Mal. B 182 and 4° C 94 Art.; these are in addition to Worcester College’s copy), and the National Trust has a copy at Sissinghurst Castle & Garden. The presence of stamps in six of the twenty-five surviving copies exceeds coincidence, and requires explanation.

Figure 1. ‘OFF 4’ stamp in Aphra Behn, Abdelazer, or The Moor’s Revenge (London, 1677). Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

That no scholars of early modern drama have commented on these marks is unsurprising. There is no reason why such stamps should have attracted the attention of the New Bibliographers, whose interest in how physical evidence from the printing process could inform textual scholarship (in particular editorial theory) did not extend its focus to post-publication additions to published texts.Footnote2 Consequently, textual editors would have no cause to linger over the presence of these stamps, even if (as in the present case) there is a healthy representation of such stamps amongst the early textual witnesses being collated for an edition. For scholars interested in provenance and user marks, the ‘BE’ stamp (for example) might initially read, tantalisingly, as if corresponding to an owner’s initials – indeed, the ‘OFF 4’ stamp has attracted precisely this kind of attention, featuring in the Provenance Online Project’s ‘Monday Mystery’ blog post for 11 May 2015 with an appeal ‘about who owned these plays’.Footnote3 There is, however, no overlap in provenance amongst the copies of the play bearing identical stamps. Nor is it likely that the marks pertain to licensing: plays were licensed for performance prior to printing, and playbooks from this period frequently feature a record of the licensing date and the name of the Licenser of the Press, Robert L’Estrange (until 1679). Equally unlikely is the possibility that the stamps could be import marks: although undoubtedly some paper stock was imported to England, stamping the blank paper (rather than its wrapper or cover) would fundamentally decrease its utility.

The explanation in fact lies somewhere between production and reception, and relates to the publishers: James Magnes and Richard Bentley. Expanding our purview to incorporate other playbook titles issued by the same publishers in the 1670s yields a number of additional examples of quartos whose final leaf bears comparable ink stamps. Even a preliminary survey of Magnes and Bentley playbooks (conducted via inspection of digital images and through consultation with relevant librarians and archivists) shows, for example, that the OFF/4 stamp appears in copies of John Crown’s The Countrey Wit (1675) held by the British Library, the Newberry Library, the Beinecke Library, and Cambridge University Library. It also appears in at least two copies of Nathaniel Lee’s Sophonisba (1676): Cambridge’s copy and the Folger Shakespeare Library’s copy. The copies of Behn’s Abdelazer (1677) that have the OFF/4 stamp are the British Library, the Folger, the Beinecke and the University of Akron; the copies with the BE stamp, noted above, are both in Scotland. In addition, we see a circular stamp containing the letter ‘M’ in copies of Thomas D’Urfey’s The Fool Turn’d Critick (1678) at the Staatsbibliothek Bamberg in Germany and the British Library; the Early English Books Online digital facsimile of the Huntington Library’s copy is unclear but looks as though it just might contain the remnants an M stamp also. An M stamp also appears in the British Library’s copy of D’Urfey’s Squire Oldsapp (1679). Another D’Urfey play, The Virtuous Wife, printed by T[homas]. N[ewcomb]. for R[ichard]. Bentley and M[ary]. Magnes (James Magnes’s widow) in 1680, has a comparable circular stamp featuring the letter ‘B’ (this copy is held by the British Library), as does one of the Huntington’s copies of Thomas Otway’s The Orphan (1680), printed for R. Bentley and M. Magnes. The University of Michigan’s copy of Nahum Tate’s The History of King Lear (London: Printed for E. Flesher and sold by R. Bentley and M. Magnes, 1681) has ‘MB’ (as a ligature) with three dots above and three dots below, within the circle. In the course of surveying the playbook holdings of a number of libraries, Claire Bourne reports having observed such stamps in copies of several further Bentley and Magnes playbooks: Wycherley’s The Plain Dealer (1677), Bancroft’s The Tragedy of Sertorius (1679), Dryden’s The Mistaken Husband (1675) and The Kind Keeper (1680), Crown’s The Misery of Civil War (1680), Behn’s The Town Fopp (1677), and D’Urfey’s A Fond Husband (1677) and Madam Fickle (1677).Footnote4

Intriguingly, such stamps can also be found on letters posted during this period: Bodleian MS Locke c.19, for example, includes a letter from Sir Thomas Stringer in London to John Locke in Montpellier, dated 10 February 1675/6, that features the OFF/4 stamp (ff.118-19). Wolf Hess reproduces an example dated 9 August 1674 in his contribution to the London Postal History Group’s magazine, Notebook, in Citation1990, where he also explains that these are in fact letter receivers’ stamps.Footnote5 In a selection of notes prepared by Barrie Jay in the course of writing his The British County Catalogue of Postal History, Volume 3 – London (Citation1983), a further example (not included in Jay’s book itself) is reproduced: a letter from London to Ecton, 1675, with the OFF/4 stamp, included as an example of General Post receiving house stamps.Footnote6 Why, though, would such receivers’ stamps be present in playbooks?

The stamps in question were only in use for a very limited period. The Royal Mail was established in 1635 and Letter Receiving Houses by 1652/3.Footnote7 Following the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, the postal service was briefly discontinued and then re-established, with Colonel Henry Bishop appointed as the first Postmaster General in June 1660.Footnote8 Bishop is perhaps best known for the introduction of date stamps, known as Bishop marks (bisected circles featuring an abbreviated form of the name of the month in one half, and the numerical date in the other half: e.g. NO/7 for November 7). Recording the date on which a letter was received by the General Post Office was intended to demonstrate that postal delivery was not delayed. In 1661, Bishop also appointed general post letter receivers, who accepted mail at local offices and conveyed it to the General Post Office, in Bishopsgate Street (until March 1678, when it moved to Lombard Street).

These letter receivers also marked mail they accepted with a stamp identifying their office as a letter’s point of origin. Such stamps originally identified the office by number, consisting of either a bisected circle containing the letters ‘OFF’ and a numeral, or simply a numeral.Footnote9 The OFF/4 stamps found in the playbooks listed above are a perfect match for the Office stamp reproduced in Barrie Jay’s study of the postal history of London and in Hugh Feldman’s more recent (and comprehensive) study of the letter receivers of London.Footnote10 Jay indicates that the stamp was known to be in use between 1671 to 1676, while Feldman gives similar date ranges (1671–1675 on page 12; 1671–1676 on page 13), and notes that it is ‘the most common’ surviving handstamp.Footnote11 The appearance of the stamp in Abdelazer, printed in 1677, slightly extends this 1671–76 date range.

Feldman notes that ‘[b]y 1673 receiving houses started to make use of handstamps which carried one or two letters’ and which ‘displaced the use of the Office Number types’.Footnote12 The letters corresponded to the initials of the receivers themselves, rather than their offices. John G. Hendy appears to have been the first modern scholar to attempt to associate specific stamps with their owners, but he seems not to have known about the brief period in which office number stamps were used.Footnote13 It is not quite as simple as positing that office number stamps were superseded by receiver initial stamps though, for as Feldman observes, ‘[i]t is unclear as to what caused office numbers 3 and 4 to continue using these types after the initial types had been adopted’.Footnote14 Feldman posits that the handstamps consisting of a numeral above the line and a letter below, or of a numeral only, were issued by General Post Office, while the receivers’ initials handstamps were likely procured by the receivers themselves.Footnote15 He is notably silent on the origin of the OFF/4 stamp, which is something of an anomaly, being the only known stamp to reverse the position of the letters and numeral. This may suggest (to answer Feldman’s own question about the persistence of office stamps in the age of receivers’ initials stamps) that it was obtained by the receiver rather than issued by the General Post Office.Footnote16

There can be little doubt that the stamps present in the copies of plays published by Magnes and Bentley named above are letter receivers stamps. We know that Magnes was a letter receiver because he was named amongst the five initial receivers appointed by Bishop. The announcement of the official letter receivers was published in a number of broadsheets in 1661. An advertisement in the Kingdomes Intelligencer for 29 April to 6 May 1661, for example, names the five letter receivers appointed by the Postmaster General, the third of which is ‘Covent Garden. Mr. Magnes Stationer in Russel-street’, the others being two grocers (Mr Parker and Mr Roberts), another stationer (‘Mr. Place Stationer at Grays-Inn-gate’ in Holborn), and another man (Mr Eales) of unspecified trade.Footnote17 Magnes and Bentley’s imprint on the playbooks’ titlepages explicitly identifies their location as ‘at the Post-Office in Russel-street, in Covent-Garden’ (The Countrey Wit; The Fool Turn’d Critick) and ‘in Russel-Street, near the Piazza, at the Post-house’ (The Virtuous Wife).

Until now, and as Hugh Feldman states, ‘because of the general lack of senders’ addresses included in letters sent at this period, it has not been possible to determine which office numbers were associated with each of the receiving houses existing at that period’.Footnote18 With the benefit of the information provided above, we can now confidently identify Magnes as the letter receiver for Office 4, thus shedding light on the origin of mail of that period bearing the OFF/4 stamp.

Surprisingly little is recorded about James Magnes, whom Henry R. Plomer described simply as a publisher of plays and novels.Footnote19 When Magnes died in 1678, Richard Bentley, who had been apprenticed to him from March 1659, continued the business – including publishing and selling plays – jointly with Magnes’s widow, Mary until her death in 1682, and then with Magnes’s daughter, Susanna. In 1684 Bentley was made free of the Stationer’s Company and could register titles under his own name. Bentley is also recorded as a letter receiver from at least 1682 (with a salary of £13 per annum).Footnote20 It is also very possible that he was the ‘Robert Bentley’ Feldman identifies as using a ‘B’ stamp from 1679.Footnote21 It is striking that this sequence of changes in the staffing of the business is consistent with the dates of the stamped playbooks listed above: the OFF/4 stamp was in use until 1677; the BE stamp not before 1677; the ‘M’ stamp (which is not attested to in Feldman’s list of recorded receivers’ initials handstamps) appears in plays printed in 1678 and 1679; the B stamp in 1680; and the ‘MB’ stamp in 1681. On this evidence it would be plausible to conjecture that when James Magnes died in 1678, the OFF/4 stamp was retired and superseded by the stamps with individual initials, as Feldman notes had been the case for other letter receivers from 1673.Footnote22 If the M stamp signified Mary Magnes, we might expect further research to yield additional examples in playbooks up until 1682, when she died. Feldman posits that the ‘MB’ stamp was in use between 1680 and 1682 and belonged to a probable receiver whom he calls ‘M. Bentley’, but it is not clear who an ‘M. Bentley’ would be. We know it cannot be Richard’s wife (who was named Katherine, and whom he did not marry until 1690). Might MB refer to (Mary) Magnes and (Richard) Bentley?Footnote23

However, the question remains: why would James Magnes (and later Mary and Susanna) and Richard Bentley be receiving (for the post) copies of plays that they themselves had published? It is far more likely that they, being not only publishers but involved in the postal business, sent stock to a distributor or bookseller across town or regionally: that is, Magnes and Bentley served as publisher, bookseller and distributor. This is a matter that has long eluded scholars, especially in the context of regional readers: as Paul Morgan provocatively asked in his seminal study of the then relatively unknown female book-collector from the English Midlands, ‘Where did Frances Wolfreston obtain this lighter literature?’Footnote24 Morgan notes that booksellers ‘were well established in the larger towns in the neighbourhood of Statfold by the mid-seventeenth century’, but does not comment on how those sellers received their goods from London.Footnote25 The stamp phenomenon under investigation here constitutes important evidence of playbook distribution by mail, including the role of playbook publishers in mail logistics. Frustratingly, of the numerous examples of stamped playbooks cited above, none (to our knowledge) bears evidence of original ownership. However, there is a kind of absence of evidence that is at least consistent with our working hypothesis. The Sissinghurst Castle copy of Abdelazer, which does not have a stamp, was owned by Captain Edward Agberowe, twenty of whose books (seventeen of them plays) have been located.Footnote26 Agberowe divided his time between London and Ludlow, Shropshire, and seemed to have been in the habit of purchasing his playbooks whilst in London. It is unsurprising, then, that his copy is not stamped: it would have been acquired in person rather than posted.

Given that these plays appear to have been posted, a conspicuous and consistent feature of all the examples listed above is the complete absence of a recipient address. The fact that none of them has an address is significant, as it implies that including an address proximate to the stamp was not conventional. What, then, is going on here? Examination of surviving letters from the period provides the first clue. Letters that took the form of a single sheet of paper were folded over and sealed to ready them for post and to keep the contents private; whilst the address of the intended recipient would feature prominently on one side, the receiver’s stamp typically appeared on the reverse (sealed) side. Evidently, then, co-location of address and stamp was not an intrinsic requirement during the period. In all of the playbook examples given above, the receiver’s stamp is placed on the verso of the final leaf, which typically contains the Epilogue – but The Countrey Wit is different: that playbook has a blank final page, and its receiver’s stamp is placed there, by itself, where there is ample room to include a postal address if one was required. The logical conclusion is that although the receiver’s stamp had to be placed somewhere visible (yet discreet: on the final leaf, not the titlepage), inscribing an address on the playbook itself was never the intention of the sender. Yet it seems unlikely that Magnes and/or Bentley would use the post stamp – which had an official status – for business unconnected to the post (e.g., for inventory purposes).

An account of the work of the post office, written ca. 1677 and printed in 1898 from the manuscript owned by Lord Dartmouth, offers a second clue to what might be happening:

To every Letter Receiver is appointed a different stamp to distinguish their Letters from one another, Least when wee come to examine their parcells, and finding paid Letters, mix’t with unpaid Letters under Rated and the like they pretend ignorance of such Letters, to the prejudice of the Office and sometimes to the owners of them.Footnote27

The use of receiver stamps served to distinguish between items of mail legitimately and illegitimately included in parcels.Footnote28 The consistent absence of an address in any of the copies of the playbooks, even when there was a blank final leaf that could easily accommodate one, suggests that the most likely scenario is that the publisher was sending multiple playbooks to their distributors (booksellers across London or regionally), and that the parcel of plays would have had a wrapper bearing the recipient’s address.Footnote29 The individual plays included in the parcel would each have been stamped as evidence of their legitimate inclusion in the posted parcel.

Robert Darnton’s statement about distribution of books in the eighteenth-century French context – that ‘[l]ittle is known about the way books reached bookstores from printing shops’ – remains surprisingly apposite to the English Restoration context.Footnote30 The stamps discussed in this article offer a glimpse of one way in which English playbooks of the 1670s and 1680s may have been distributed by their own publishers, making use of the postal system that was readily available to them as official letter receivers. The foregoing study has discovered that the post office in Russell Street, Covent Garden, operated by James Magnes and later Richard Bentley, was receiving office number four and used the OFF/4 stamp. The presence of this stamp in a playbook published in 1677 (Behn’s Abdelazer) marginally extends the date range associated with the use of this particular stamp. Interestingly, the presence of a BE stamp in two copies of the Abdelazer quarto suggests not just that the play was mailed at least twice, but (because the stamps seem to have been in use sequentially rather than simultaneously) that a notable period of time had lapsed between mailings – long enough for a new letter receiver to be appointed or at least acquire a new stamp. A final implication of the foregoing discussion is the possibility that this hints at the play still being available for purchase and in demand months or even years after publication: Feldman gives a range of 1684-94 as the date range in which the BE stamp was in use.Footnote31 If Feldman’s dates are accurate, the BE stamp may have been applied to these two copies anywhere between seven years after the play’s first publication or up until one year after the appearance of the second quarto (which was printed in 1693).

This case study has focused on the output of Magnes and Bentley specifically, given that the original impetus for the investigation was the presence of these stamps in multiple editions of Abdelazer; it remains to be explored whether any other stationers/letter receivers utilised comparable distribution arrangements. A further question – perhaps unanswerable unless an addressed example is discovered – persists as to whether playbooks were distributed to individuals on request, or whether they were distributed in packages of multiple copies to provincial booksellers.

Notes

1 The authors wish to thank the following librarians and scholars for generously engaging with the ideas explored in this article and for their time in consulting local copies of the plays discussed: Morex Arai (Huntington), Barry Attoe (The Postal Museum, London), Mark Bainbridge (Worcester College, Oxford), Mary Ellen Budney (Beinecke Library, Yale), Maureen Bell (University of Birmingham), Eleanor Black (Sissinghurst Castle, NT), Mark Bloom (University of Akron), Claire Bowditch (University of Queensland), Elin Crotty (University of Edinburgh), Katy Darr (Beinecke Library), Abigail Fisher (University of Melbourne), Rebecca Flore (University of Chicago), Ian Gadd (Bath Spa University), Jill Gage (Newberry Library), Francesca Galligan (Bodleian Libraries), Elaine Hobby (Loughborough University), Tom Holland (National Library of Scotland), Scott Jacobs (Clark Memorial Library, UCLA), Wallace Kirsop, Rebecca Maguire (Beinecke Library), Fiona McHenry (British Library), Lydia Nixon (Lilly Library, Indiana University Bloomington), David Pearson, Tim Pye (National Trust), Liam Sims (Cambridge University Library), Anthony Tedeschi (Alexander Turnbull Library), Kyle R. Triplett (NYPL), Emily Walhout (Houghton Library), Christian White (Christian White Rare Books), Heather Wiegert (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), and the late William Proctor Williams (University of Akron).

2 The authors’ interest in these stamps arose precisely because McInnis, who is editing Abdelazer for The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Aphra Behn, was confused as to how to account for the presence of these stamps.

3 https://provenanceonlineproject.wordpress.com/2015/05/11/mystery-monday-off-stamp-from-the-folger/.

4 We also thank Claire for bringing to our attention the example of the Folger Shakespeare Library’s copy of Thomas Duffet’s Psyche Debauch’d (1678) (Folger call number D2452): the catalogue description suggests the presence of a stamp with monogram “B.L.[?]”, but an image kindly supplied by Abbie Weinberg reveals a curious cypher: an ornate, circular stamp featuring four five-petalled flowers surrounding a monogram that includes the intertwined letters M, R, T, L, a slanted A and possibly an O (if so, the component letters might spell MORTAL). It is not a receiver’s stamp.

5 See Hess, 21.

6 The undated document is available online here: https://risorse.issp.po.it/dbcollezioni/365_jay.pdf.

7 See Feldman, 1.xi.

8 See Feldman, 1.11.

9 See Jay for a list of some of the handstamps used in receiving houses.

10 Jay, example L66 on p.12; Feldman, also example L66 on p.12 of volume 1.

11 Feldman, 1.13.

12 Feldman, 1.13.

13 See Hendy, 51, where he tentatively assigns the ‘G’ receiver’s stamp to Alice Grone, whose office was situated between the Temple Gates.

14 Feldman, 1.13.

15 Feldman notes that, because the stamps were made of boxwood, ‘the quality of the strike varied considerably, especially when the stamp had been used for a substantial period of time’ (1.16). This also explains the variation we see in the stamps in the playbooks discussed here.

16 Jay (12) and Feldman (1.13) both acknowledge the existence of an (earlier) 4/Off stamp as well as the later OFF/4, which in turn may suggest that the original 4/Off stamp was replaced by the letter receiver (perhaps due to wear?). But this explanation still begs the question as to why a replacement office stamp was obtained rather than a stamp with the receiver’s initials.

17 These details also appear in the announcement Feldman cites from Mercurius Publicus (2 May 1661) and the one he reproduces (1 August to 8 August 1661): see Feldman, 1.11-12.

18 Feldman, 1.12.

19 Plomer, 122.

20 Raguin, 11, citing news bulletin dated November 2–6, 1682.

21 Feldman, 2.56. See also John Alden’s discussion of advertisements for pills that were sold via booksellers in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, in which he suggests that the bookseller named as ‘Robert Bentley’ might in fact be Richard Bentley (24). It is significant that James Magnes was also named in similar advertisements, as was ‘Mrs Bentley, bookseller in Covent Garden’ (25), who Alden suggests was Katherine Bentley, Richard’s widow.

22 Feldman, 1.13.

23 Feldman, 2.56.

24 Morgan, 208.

25 Morgan, 208.

26 See McInnis, forthcoming.

27 ‘The Post Office in 1667’ in St. Martin’s-le-Grand ed. Bennett, 64.

28 Whilst scholars such as Joad Raymond have written about the transportation of books ‘from London to the provinces by chapmen or by carriers’, where ‘they were distributed among friends’, and how (following the introduction of the postal service in the seventeenth century) ‘Metropolitan readers habitually sent pamphlets and newsbooks to their correspondents’, citing seventeenth-century letters being ‘littered with references to enclosed printed material’ (83–84), the stamps investigated in this present article testify to the systemic use of the mail service by publishers themselves for the distribution of playbooks.

29 Although closer physical inspection of the stamped playbooks might reveal pinholes suggestive of an address having been pinned to the front of the playbook, it seems highly unlikely given the potential for a weakly secured address to be separated from the playbook during transportation (to say nothing of its potential to damage the title page).

30 Darnton, 77.

31 Feldman, 2.57.

Bibliography

- Alden, J. ‘Pills and Publishing: Some Notes on the English Book Trade, 1660-1715‘, The Library s5-VIII, issue 1 (March 1952): 21–30. doi:10.1093/library/s5-VII.1.21.

- Darnton, R. ‘What is the History of Books?‘, Daedalus 111, no. 3 ( Summer 1982): 65–83.

- Feldman, H. Letter Receivers of London 1652 to 1857: A History of Their Offices and Handstamps within the General, Penny and Twopenny Posts. 2 vols. Bristol: Stuart Rossiter Trust Fund and the Postal History Society, 1998.

- Hendy, J. G. The History of the Early Postmarks of the British Isles. London: L. Upcott Gill, 1905.

- Hess, W. ‘London: Postmarks of the Inland and local Offices 1661 - 10 January 1840‘, London Postal History Group Notebook 92 (1991): 1–86. https://www.gbps.org.uk/information/downloads/lphg-notebook/92-95%20-%20Dec%201990.pdf

- Jay, B. The British County Catalogue of Postal History. Vol 3, London. [Blackheath, Staffordshire]: R.M. Willcocks, 1983.

- Kingdomes Intelligencer, issue 18, 29 April to 6 May 1661. (Gale Primary Sources: Burney Newspapers Collection, accessed 3 August 2023).

- McInnis, D. ‘“Ed: Agberowe”, seventeenth-century collector of Restoration playbooks’, The Library, forthcoming 2024.

- Morgan, P. ‘Frances Wolfreston and “Hor Bouks”: A Seventeenth-Century Woman Book-Collector‘, The Library 6th series, 11.3 (1989): 197–219.

- Plomer, H. R. A Dictionary of the Booksellers and Printers who Were at Work in England, Scotland and Ireland from 1641 to 1667. London: Bibliographical Society, 1907.

- Raguin, M. M. British Post Office Notices, 1666–1899 Volume 1: Pre–1800. Medford, MA 1991.

- Raymond, J. Pamphlets and Pamphleteering in Early Modern Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- St. Martin’s-le-Grand, vol. 8, ed. Bennett E. London: W. P. Griffith & Sons Ltd, 1898.