?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

COVID-19 led to the implementation of containment measures including social distancing and lockdowns which negatively impacted people’s mental and psychological well-being. To weaken the adverse outcomes associated with these containment measures, governments worldwide implemented several policies to provide financial, and non-financial assistance to people. In Australia, the government implemented COVID-19 support payments to provide financial relief to its citizens. In this study, we examine the impact of five different COVID-19 support payments on the subjective well-being of Australians. We do this for the general population, and across key groups by using econometric strategies while measuring subjective well-being with overall life satisfaction. Our results show that the five different COVID-19 support payments are associated with an increase in the wellbeing of Australians. This effect is larger for males, individuals over 40, and those without bachelor’s degrees.

1. Introduction

Subjective well-being (SWB) refers to how people generally evaluate their life satisfaction. The evaluation comprises reactions to life events; gratification from important areas of life, such as work, friendships, and marriage; as well as depending on factors such as personality (Diener Citation1984; Diener et al. Citation1999). Sustainable development goal three highlights the importance of promoting the well-being of individuals. As a result, improving the well-being of individuals has become an important policy focus in both developed and developing countries. Indeed, several development economists and policy analysts have suggested that it is important for the government to focus on implementing policies that improve the standard of living, happiness, quality of life, and overall well-being of its people rather than implementing policies that are geared towards improving macroeconomic indicators like gross domestic product (GDP). A survey conducted by Hamilton and Rush (Citation2006) in Australia shows that 77% of the Australian adult population believes that the government should not focus on maximising wealth but rather focus on maximising the happiness of its citizens. This belief makes sense because the well-being of individuals has been linked with numerous positive outcomes such as productivity, innovation, creativity, good physical health, higher income, and others which promote economic development (Dimaria, Peroni, and Sarracino Citation2020; Sjøgaard et al. Citation2016; Wang, Yang, and Xue Citation2017; Wrosch and SCheier Citation2020). Intuitively, when the government implements policies to improve the well-being of its citizens, it will consequently lead to economic development.

Many people have been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, with current estimates by the World Health Organization standing at 6,988,679 deaths as at the ending of 2023 (WHO Citation2023). Besides, leading to deaths and prolonged diseases, COVID-19 generated an epidemic of mental health problems (Bradbury‐Jones and Isham Citation2020). For instance, the National Study of Mental Health and Well-being in Australia reported that 15% of Australians aged 65–85 years experienced psychological distress during the COVID-19 lockdowns (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] Citation2021). The mental effect of COVID-19 can linger long after the pandemic. Also, there is increasing evidence of emotional distress and anxiety associated with COVID-19 (Folayan et al. Citation2021; Moreno et al. Citation2020; Santomauro et al. Citation2021). For example, Panchal et al. (Citation2020) find that about four in 10 adults reported symptoms of depression and anxiety in the US. In the United Kingdom, Groarke et al. (Citation2020) found that COVID-19 increased psychological distress. The pandemic-related distress and anxiety are caused by factors including economic hardship, fear of getting the illness, and uncertainty about the real effect of COVID-19 (Moreno et al. Citation2020). Physical distancing, lockdown, and school and business closure linked with COVID-19 also led to multiple social problems including social isolation, loneliness, and decreased family and social support, especially for vulnerable and older people (Qian and Fan Citation2020; Sepúlveda-Loyola et al. Citation2020; Szkody et al. Citation2021). Also, COVID-19 caused a downturn in many economies leading to higher levels of poverty, unemployment, financial crisis, loss of income, and food insecurity, which impeded quality of life (Blustein et al. Citation2020; Chen and Yeh Citation2021; Pereira and Oliveira Citation2020). The adverse health, economic and social consequences associated with COVID-19 have spurred the interest of policymakers, yielding several policies designed to improve the well-being of people whose lives were severely impacted by COVID-19. In Australia, the government implemented COVID-19 support payments to provide financial assistance to Australian citizens (DHHSV Citation2022).

Australia reported its first COVID-19 case on NaN Invalid Date, in Victoria. The virus started spreading across other Australian states, and on NaN Invalid Date, Australia reported over 11,350,000 cases with 11,330,000 recoveries, and 19,265 deaths (VC Citation2023). This compelled the Australian government to adopt the ‘containment measures’, designed to limit the transmission of the virus between individuals (Hoffman et al. Citation2021; Payne, Morgan, and Piquero Citation2020). These containment measures included social distancing of 1.5 metres between two people, a ban on non-essential indoor gatherings of 100 or more people, outdoor gatherings of 500 or more people, lockdowns, and others (Payne, Morgan, and Piquero Citation2020). These measures limited human movements and interactions leading to social and economic issues such as income and job loss, reduction of social connections, and unemployment, changing people’s everyday life in Australia (Rossell et al. Citation2021). For example, Brindal et al. (Citation2022) find that COVID-19 restrictions reduced life satisfaction and social restriction worsened the well-being of Australians.

In response to the adverse outcomes associated with the COVID-19 containment measures, the Australian government designed several support funds to provide financial assistance for Australian citizens. Some of these support funds include Job seekers’ support payments, COVID-19 quarantine support payments, COVID-19 workers support payments, COVID-19 rent relief payments, COVID-19 stimulus payments, COVID-19 disaster support funds, and others. The first stimulus package was introduced on 12 March 2020 and was expanded on 22 March 2020 (Andrew et al. Citation2020). Regarding the job seekers’ support payments, the Australian government realised a total of $35.4 billion to support eligible businesses (DHHSV Citation2022). All eligible businesses received between $10,000 and $50,000 tax-free cash payments to keep all these businesses from collapsing (DHHSV Citation2022). Thus, the Australian government pursued an explicit policy of ‘business hibernation’ during the COVID-19 lockdown period (Norman Citation2020). Nearly, 70% of the first two stimulus packages were used to support businesses because government restrictions led to the closure of several businesses for at least six months leading to loss of profit. COVID-19 worker support payment also provided a $1,500 payment to financially support Victorian workers, including guardians or carers, and close contacts of confirmed cases of coronavirus (COVID-19) who have been instructed by the Department of Health and Human Services to isolate (DHHSV Citation2022). The COVID-19 workers’ support payment aimed at helping workers to isolate to avoid community transmission and prevent further cases of COVID-19. All these support funds provided financial assistance to all eligible Australians during the intense periods of COVID-19 which, in turn, may influences their well-being.

Yet, despite the importance of these COVID-19 support payments (CSP) for the quality of life in Australia during the intense period of COVID-19, much less is known about how CSP influence the subjective well-being of the Australian adult population. CSP is expected to improve the well-being of Australians in several ways. First, many people lost their job during the COVID-19 lockdown leading to a significant drop in their earnings (Noble, Hurley, and Macklin Citation2020). Many people, therefore, sort to financial, and non-financial assistance from the government to support their livelihood which is likely to influence their well-being. Second, CSP provided financial relief to people during the lockdown which is expected to reduce financial stress. A reduction in financial stress is associated with a decline in physical and mental health problems such as depression or anxiety (Choi Citation2009; De Miquel et al. Citation2022), which increases the well-being of people (Choi et al. Citation2020; Friedline, Chen, and Morrow Citation2021; Montpetit, Kapp, and Bergeman Citation2015). Third, a lack of money or financial support leads to relationship problems (Cameron Citation2014; Papp, Cummings, and Goeke‐Morey Citation2009). Therefore, providing financial assistance through CSP may reduce relationship problems which in turn improves the well-being of people (Muir et al. Citation2017; Xie et al. Citation2020). Fourth, CSP may also induce income effects for those that were still working during COVID-19 lockdown to improve their well-being. Those that were still working and at the same time received CSP may experience an improvement in income or a reduction in expenditure. This is because they may allocate less income to expenses like rent, electricity and gas bills which means that more income will be available for wellbeing-enhancing activities. For example, an individual who receives rent relief payment may have extra money to buy gas to heat his or her home to improve wellbeing because most people were at home during the COVID-19 period. Furthermore, Melbourne, Victoria’s capital city with a population of about 5.5 million people had more lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic than other cities in the world (Macreadie Citation2022). Specifically, the city of Melbourne was locked down for 262 days which severely affected education, sports, arts, events, tourisms, jobs, healthcare utilisation, and others (Macreadie Citation2022). During this period, many households in Melbourne rely on the Victorian government financial support to cope with income loss. Given that Melbourne had the longest lockdown, Melburnian are more likely to rely on the CSP for longer period than Other Australian cities including Sydney, Brisbane, Perth, Darwin, Townsville and the Gold Coast that were also locked down during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, we expect the CSP to improve the wellbeing of Australians living in Melbourne compared to other cities.

In this study, we seek to answer the following question: How does CSP influence the subjective well-being of Australia’s adult population and across other key groups? To answer this question, we use two waves of panel data drawn from the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. Given the endogenous nature of the relationship between CSP and subjective wellbeing, our identification strategy is to instrument for CSP using total COVID-19 cases per each state in Australia obtained from Victorian COVID-19 data. However, the instrument turns out to be a weak instrument after utilising it. Therefore, we sort to an alternative instrumental identification strategy, Lewbel (Citation2012) 2SLS which builds an internal instrument by exploiting heteroskedasticity in the data. After, addressing endogeneity using these techniques, we find consistent evidence of the five different CSP improving the subjective well-being of the Australian adult population.

This study contributes to two different strands of the literature. First, we contribute to the broader literature that has examined the antecedents of the well-being of people. This literature has identified income, trust, social capital, fuel poverty, culture, and religion, unemployment, among others as the main factors that influence the subjective well-being of people (Churchill, Smyth, and Farrell Citation2020; Diener and Oishi Citation2000; Prakash, Churchill, and Smyth Citation2020; Winkelmann Citation2009; Zhang and Zhang Citation2015). Although these studies have improved our understanding of the factors that influence subjective well-being and thus the results from these studies have been useful in policy implementations, none of them have examined how CSP influences subjective well-being. This presents a significant shortcoming in this strand of the literature when policymakers are increasingly interested in understanding the link between subjective well-being and policies implemented to curb the spread of COVID-19.

Second, we contribute to a small body of literature that has started examining the implications of CSP in Australia. To the best of our knowledge, only two studies have examined the implications of CSP in Australia. The first study is by Adabor (Citation2023) who examines the link between CSP, and gambling and find that COVID-19 support payments increase gambling participation in Australia. The second study is by Watson and Buckingham (Citation2023) who examine how COVID-19 business support payments influence the profit of businesses that received it. The study finds that COVID-19 business support payments increased the profit and savings of the business that received it as well as improve the wages of the workers in such a bussiness. We differ from these studies because we focus on how CSP influences the subjective well-being of the Australian adult population.

2. Data and variables

The study uses nationally representative longitudinal data from the HILDA survey that commenced in 2001 and has since produced 21 waves. The survey collects information on the Australian adult population aged 15 and above annually. Specifically, the HILDA survey collects information on health, income, gambling, subjective well-being, labour market dynamics, energy expenditure, and others. The recent two waves (i.e. waves 20 and 21 ‘collects’) contain information on covid-related issues including CSP, social distancing, and others. In this study, we use the recent two waves given that information on COVID-19 support funds are available only in these waves. Thus, the analysis of this study is restricted to the recent 2 waves because they contain information on subjective well-being and COVID-19 support funds.

2.1. Subjective well-being

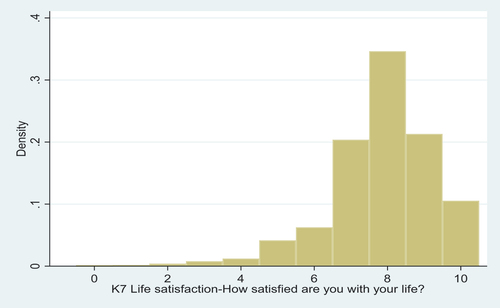

Following previous studies (Awaworyi Churchill and Smyth Citation2020; Prakash, Churchill, and Smyth Citation2020), we measure subjective well-being using the overall life satisfaction of respondents from responses to a single-item question. Specifically, the HILDA survey poses the question: ‘All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life?’ On a scale of 0–10, in which zero is ‘totally dissatisfied’ and 10 is ‘totally satisfied’, respondents were asked to select their score or responses to this question. shows the distribution of responses on overall life satisfaction. The responses do not reflect the experience of pleasant or stable emotions, rather it reflects the satisfaction obtained from life. Although few past studies (Fujita and Diener Citation2005) have criticised the use of single-item scales because they may not be valid measures of subjective well-being, overall life satisfaction is a valid and reliable measure of subjective well-being (Diener and Oishi Citation2000; Diener et al. Citation1999). As a result, economists, and psychologists have used questions of this sort as a typical measure of subjective well-being given its reliability, validity, and availability on a large-scale survey. As shown in in the Appendix, the average life satisfaction for an Australian is 7.83 on a scale of 1–10 which is in line with norms in Western adult samples (Cummins Citation1995) and other studies conducted in European countries (Delhey and Dragolov Citation2016; Huebener et al. Citation2021).

2.2. COVID-19 supports payments

The measure of CSP in this study reflects whether respondents received any form of funds or payments from the Australian government. Data on CSP in the HILDA data was collected in waves 20 and 21 as part of questions related to COVID-19 pandemic. The specific question asked: Have you received any form of CSP in the last 12 months? The responses to this question are on a scale of 1–5, where (1) indicates ‘received COVID-19 Job seeker’s support payment’, 2 indicates ‘received quarantine support payment’, 3 indicates ‘received COVID-19 rent relief payment’, 4 indicates ‘received COVID-19 stimulus payment’ and 5 indicates ‘received other COVID-19 support payment’. Based on these responses and following approaches utilised in previous studies we create and label five binary indicators as (1) ‘job seeker’s payment [JSP]’, (2) ‘rent relief payment [RRP]’, (3) ‘quarantine support payment [QP]’, (4) “stimulus payment [SP] and (5) ‘other COVID-19 support payment [OSP]’.

2.3. Control variables

Based on existing studies, we control for possible factors that influence subjective well-being (Awaworyi Churchill and Smyth Citation2020; Kumar et al. Citation2023; O’connor et al. Citation2021). These control variables include household, and individuals’ characteristics that influence subjective well-being. Thus, we include age, household size, total children, marital status, employment status, debt servicing, and education in our regression model as control variables. All these variables are described in in the Appendix.

3. Empirical method

To examine the impact of CSP on subjective well-being, we estimate the following empirical model:

Where is the measure of subjective wellbeing of individual i at time t;

captures the five different forms of CSP received by respondents in the past 12 months, and

is a vector of covariates utilized as control variables.

and

indicate time and individual fixed effects, respectively. Also,

is the error term.

We first estimate EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) using an ordinary least square approach while controlling for time and state fixed effects that account for time-invariant and differences across state that are typically unobservable. This constitutes our baseline estimates. However, endogeneity is likely to be an issue in the bassline results because of omitted variables and measurement issues. Measurement errors occur because of inaccurate responses from respondents whereas omitted variable problem occurs because of our inability to control all factors that influence CSP and subjective well-being. For instance, the measure of CSP are based on those who receipt them but do not capture the specific amount received. An individual who received more amount of CSP is likely to be happier compared to an individual who received less, and this can introduce biases in our estimates. Even if we assume that the amount people received are equal, an individual who received more than one CSP may have more money than an individual who received only one. This could also bias our estimates. On omitted variable bias, we unable to control for anxiety cause by COVID-19 which is likely to influence people’s wellbeing during the intense period of COVID-19.

To address endogeneity issues, we use the Lewbel (Citation2012) 2SLS evident in existing studies (Churchill and Smyth Citation2017; Martey, Etwire, and Koomson Citation2022; Patra et al. Citation2016) that is well suited for resolving endogeneity. This approach constructs an internal instrument by exploiting heteroskedasticity in the data. The approach relies on internal instruments; hence, we do not need to either test or meet the exclusion restriction. The Lewbel (Citation2012) 2SLS technique approach is a precondition on heteroskedasticity which shows that the internal instrument can be obtained from the residuals of auxiliary equations, which are multiplied by the exogenous variables () in a mean cantered form (

(Lewbel Citation2012). The estimation problem can be summarised econometrically as:

Such that is subjective wellbeing; and

is the five different COVID-19 support funds. U reflects the unobserved economic factors that affect five different COVID-19 support funds.

and

are idiosyncratic errors.

is a vector of control variables. In a situation where there is no external instrument, Lewbel (Citation2012) suggested that given some level of heteroskedasticity in the data, the internal instruments (

can be generated as:

Where is the internal instrument;

is exogenous variables; and (

is a mean cantered form of

.

is the error term which has zero covariance with the covariates and represents the vector of the first stage regression residuals of each endogenous covariate on all exogenous regressors. Thus, the means of the internally generated instrument is zero. The Lewbel (Citation2012) 2SLS obtain identification of the reduced form by restriction correlation of

with

. The obtained identification is based on higher moment, and it is useful in applications in a case where there are no traditional external instruments or can be combined with the external instruments to increase efficiency.

4. Results

reports the baseline results for the impact of CSP on subjective well-being. Specifically, columns 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 of reports the effect of job seeker’s payment, quarantine payment, stimulus payment, rent relief payment, and other COVID-19 payment on subjective well-being, respectively. Generally, across all columns, we find that all the different forms of CSP are associated with an increase in life satisfaction. Specifically, the results in columns 1 to 5 show that job seeker’s payment, quarantine payment, stimulus payment, rent relief payment, and Other COVID-19 payments are associated with an increase in life satisfaction by about 0.094, 0.065, 0.076, 0.054 and 0.071, respectively. This suggests that people who received CSP during lockdown experienced an improvement in their well-being relative to those that did not receive them. This is because most people lost their jobs during the lockdown period and thus CSP was a source of income that provided a livelihood for people. Also, CSP provided financial relief for people that receive it, reducing financial stress which is likely to promote their well-being. However, a closer look at the results indicates that the effect of job seekers’ payment on overall life satisfaction is bigger than the other forms of CSP. This suggests that individuals that received the COVID-19 job support payments experienced a higher standard of living or well-being than individuals that received any of the other forms of CSP.

Table 1. COVID-19 support payments and subjective well-being (full baseline results).

4.1. Endogeneity corrected estimates

In , we attempt to address the endogeneity associated with CSP using the Lewbel (Citation2012) 2SLS that generates an internal instrument. The only reasonable assumption that needs to be met for the Lewbel (Citation2012) approach is that there should be heteroskedasticity presence in the data, which can be tested by the Breusch-Pagan test. reports the results for the effect of CSP on subjective well-being using Lewbel’s (Citation2012) 2SLS technique. Results from the Breusch-Pagan test reported at the bottom of both confirm the presence of heteroskedasticity in the first-stage residuals and therefore can be utilised to build an internal instrument. Also, we fail to reject the null hypothesis for the Sargan-Hansen over-identifying restriction tests, indicating that the instruments used in the first-stage regressions were not over-identified. Generally, the results show that all the five CSP are associated with an increase in life satisfaction. However, the Lewbel (Citation2012) 2SLS estimates are bigger than the baseline results in which indicate that endogeneity presence in the baseline results leads to underestimation of the impact of CSP on an individual’s satisfaction with life.

Table 2. COVID-19 support payments and subjective well-being (Lewbel (Citation2012) 2SLS results).

4.2. Heterogeneity

The effect of CSP on subjective well-being could potentially differ across different sub-groups. To examine if our results of the positive impact of CSP varies across different sub-group, we conduct a sub-sampling analysis for different sub-groups based on educational attainment, age, and gender. We consider male and female for gender whereas for age, we focus on those above and below age 40. For educational attainment, we focus on those with at least a bachelor’s degree and those without a bachelor’s degree. reports the effect of CSP on subjective well-being across six different sub-samples. Generally, the results in columns 1–5 across all panels of show that the five different forms of CSP are associated with an increase in life satisfaction. However, the size of the effect differs across the six-different sub-groups. For gender, the effect is more pronounced for males than females whereas for age, the effect is stronger for those above age 40. For educational attainment, the effect is larger for those without a bachelor’s degree than those with at least bachelor’s degree. Although we find consistent evidence of a positive link between CSP and subjective well-being, the size of the effect differs across different groups. This indicates that our result is heterogeneous across different sub-groups.

Table 3. COVID-19 support payments and subjective well-being.

4.3. Robustness checks

In this section, we aim to examine the sensitivity of our results using Welsch and Biermann (Citation2017) approach. Welsch and Biermann (Citation2017) measure subjective well-being as a binary variable in which one indicates life satisfaction scores of 6–10 as ‘satisfied’ and zero indicates scores of ‘0–5’ as ‘not satisfied’. reports the results of the impact of the five different forms of CSP on subjective well-being using the Welsch and Biermann (Citation2017) approach. Welsch and Biermann (Citation2017) measure subjective well-being as a binary indicator, hence, we use the probit model to estimate the effect of CSP on subjective well-being. The results in columns 1–5 of show that the five different forms of CSP are associated with an increase in the likelihood that people will be satisfied with life. This suggests that individuals that received any form of funding from the government during the COVID-19 period were relatively satisfied with life which is consistent with the baseline results in .

Table 4. COVID-19 support fund and subjective well-being (Welsch and Biermann cut-offs).

In , we use an alternative estimation strategy to examine the sensitivity of our results. Specifically, we examine the impact of CSP on subjective well-being using the ordered probit model. Using the ordered probit model is suitable because our measure of subjective well-being which is overall life satisfaction is measured on a scale of 1–10, where increasing from 1 to 10 suggests an increasing level of life satisfaction. Intuitively, the outcome variable, life satisfaction is orderly measured. reports the results from the ordered probit model for the effect of the five different forms of CSP on subjective well-being. The results show that the five different forms of the CSP are linked with an increase in life satisfaction, consistent with the baseline results in .

Table 5. COVID-19 support payments and subjective well-being-ordered probit.

5. Discussion

Overall, we find consistent evidence of the five different CSP increasing the subjective well-being of people. Precisely, the five different CSP, namely job seeker’s payment, quarantine payment, stimulus payment, rent relief payment, and Other COVID-19 payments increases overall life satisfaction in . The main economic intuition behind the positive impact of the five different CSP is that CSP reduces financial stress because it provides financial relief. Reducing financial stress decreases physical and mental health problems such as depression or anxiety (Choi Citation2009; De Miquel et al. Citation2022), which is likely to increase the wellbeing of people (Choi et al. Citation2020; Friedline, Chen, and Morrow Citation2021; Montpetit, Kapp, and Bergeman Citation2015). Also, CSP is likely to induce income effect allowing those that were working during COVID-19 periods to allocate less income to daily expenses, which means that more income will be available for wellbeing-enhancing activities like buying gym equipment to exercise in the house. However, out of the five different COVID-19 support payments, we find that the positive effect of CSP is more pronounced for job seeker’s payments in . Thus, job seeker’s payment better improves the well-being of people than others. This could be attributed to the fact that most people either lost their jobs or worked for fewer hours during the COVID-19 lockdown periods and thus the COVID-19 worker’s support payment was one of the main sources of income to support their livelihood.

One issue that is common in an empirical analysis is endogeneity. This issue occurs because of human errors or measurement errors. Also, it occurs because of the inability of researchers to control for all factors that influence an outcome variable. In , we resolve the endogeneity issue using an econometric strategy that utilises internal instrument. After addressing endogeneity, we find consistent evidence of CSP increasing overall life satisfaction across all the five different CSP. However, the endogeneity estimates were statistically higher than the baseline results in . This suggests the endogeneity slightly reduces the baseline in leading to downward bias.

We also find heterogeneity across different sub-groups in . When we disaggregated our sample into educational attainment, age, and gender sub-groups, we find a positive relationship between CSP and life satisfaction for all the sub-groups. However, the size of the effect differs across the sub-groups. For gender, the positive effect of CSP on life satisfaction is more pronounced for males than females. For educational attainment, the effect is larger for those without a bachelor’s degree than those with at least bachelor’s degree. Although most jobs closed during the lockdown, many computer-based jobs were still ongoing. Such jobs are done by individuals with higher degrees and thus these individuals were still making income during the lockdown periods. Hence, the effect of CSP on their well-being is relatively low because they were still making high income during the lockdown. For age, we find that the positive effect of CSP on overall life satisfaction is greater for those above 40 years of age, indicating that older people depend on government financial assistance to support their livelihood.

There are several economic and policy implications from these findings. First, our findings are consistent with an emerging literature that policies implemented to provide financial assistance to people during the COVID-19 lockdown are important because they improve the well-being of people (Kennelly et al. Citation2020; Toffolutti et al. Citation2022). Specifically, our findings suggest that it is important for the government to provide financial and non-financial support to its citizens during pandemic/catastrophic periods. The Australian government’s initiative of providing financial assistance such rent relief support for its citizens has been extremely beneficial and thus has improved the well-being of its citizens during the COVID-19 period. Therefore, this study encourages other developed and developing countries to adopt similar strategies or policies to help improve the well-being of their citizens in difficult times. Second, our heterogeneity results suggest that more attention or support should be given to females, an individual below age 40, and those with at least a bachelor’s degree. Specifically, the results point to the need for policymakers to take these groups into account when devising policies to improve the well-being of people in periods of severe economic crisis. Fourth, the findings from this study are important given the limited studies that examine how policies adopted to halt the spread of COVID-19 influence subjective well-being. Precisely, the findings from this study will be important for developed countries with similar demographic and socioeconomic characteristics like Australia. Thus, this study will be relevant beyond Australia’s boundaries.

6. Conclusion

The rapid spread of the ongoing COVID-19 across the world lowered the well-being of millions of people. Whereas millions of people battled with fear, anxiety, psychological distress, mental stress, and health problems associated with COVID-19, millions of people also lost their jobs due to lockdown restrictions adopted to halt the spread of COVID-19. This led to the implementation of several policies and strategies to improve the well-being of people worldwide. In Australia, the government implemented the COVID-19 support payments to provide financial assistance to Australians whose lives, and businesses were severely affected by COVID-19. Although the intended purpose of the COVID-19 supports payment is to improve the well-being of the Australian population, there is little or no evidence of the quantitative effect of COVID-19 support payments on the well-being of the Australian adult population. Therefore, this study fills an important gap in the literature by examining the impact of COVID-19 support payments on the subjective well-being of the Australian adult population. To do this, we use the recent two waves from the HILDA survey that collects information from an average of 17,000 adult Australians every year. After addressing endogeneity using instrumental econometric strategy, we find that various COVID-19 support payments improve the subjective well-being of Australians. However, the positive effect of various forms of COVID-19 support payments on well-being is more pronounced for males, individuals aged over 40, and individuals without bachelor’s degrees.

Our findings contribute to a growing body of literature that examines how various policies implemented during the COVID-19 period influence the mental and psychological well-being of people (Mccartan et al. Citation2021; Toffolutti et al. Citation2022). Although these studies are at the initial stages, there is consensus evidence of various policies implemented during the COVID-19 lockdown improving the well-being of people. This suggests that implementing various policies with a conscious attempt to financially assist individuals during pandemics or economic crisis play a vital role in enhancing their well-being. Also, the outcome from our study and this strand of the literature indicates that increased financial and non-financial assistance from the government during an economic crisis may help achieve the United Nation’s sustainable development goal three of ensuring ‘good health and well-being’.

Although the present study provides better insight into the link between COVID-19 support payments and subjective well-being, it is a country-case study. Therefore, future studies can undertake panel studies given the imperative insights that might emerge from different contexts and the general lack of studies. Also, we discussed that financial stress, and income effect are the channels through which the COVID-19 support payments influence subjective well-being. However, we do not test these channels. Therefore, future studies can use test these channels using appropriate econometric models to examine the validity of these channels and thus can shed better insight into these mediators.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Authors do not have permission to share the data.

References

- Adabor, O. 2023. “Australia’s Gambling Epidemic: The Role of Covid‐19 Support Payment.” Australian Economic Papers.

- Andrew, J., M. Baker, J. Guthrie, and A. Martin-Sardesai. 2020. “Australia’s COVID-19 Public Budgeting Response: The Straitjacket of Neoliberalism.” Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 32:759–770. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-07-2020-0096.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2021. “National study of mental health and welbeing.” ABS External cite opens in new widow, ABS. Accessed March 10, 2023.

- Awaworyi Churchill, S., and R. Smyth. 2020. “Friendship Network Composition and Subjective Well-Being.” Oxford Economic Papers 72 (1): 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpz019.

- Blustein, D. L., R. Duffy, J. A. Ferreira, V. Cohen-scali, R. G. Cinamon, and B. A. Allan. 2020. “Unemployment in the Time of COVID-19: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 119:103436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103436.

- Bradbury‐Jones, C., and L. Isham. 2020. “The Pandemic Paradox: The Consequences of COVID‐19 on Domestic Violence.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 29 (13–14): 2047. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15296.

- Brindal, E., J. C. Ryan, N. Kakoschke, S. Golley, I. T. Zajac, and B. Wiggins. 2022. “Individual Differences and Changes in Lifestyle Behaviours Predict Decreased Subjective Well-Being During COVID-19 Restrictions in an Australian Sample.” Journal of Public Health 44 (2): 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab040.

- Cameron, P. 2014. “Relationship Problems and Money: Women Talk About Financial Abuse.”

- Chen, H.-C., and C.-W. Yeh. 2021. “Global Financial Crisis and COVID-19: Industrial Reactions.” Finance Research Letters 42:101940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.101940.

- Choi, L. 2009. “Financial Stress and Its Physical Effects on Individuals and Communities.” Community Development Investment Review 5:120–122.

- Choi, S. L., W. Heo, S. H. Cho, and P. Lee. 2020. “The Links Between Job Insecurity, Financial Well‐Being and Financial Stress: A Moderated Mediation Model.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 44 (4): 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12571.

- Churchill, S. A., and R. Smyth. 2017. “Ethnic Diversity and Poverty.” World Development 95:285–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.02.032.

- Churchill, S. A., R. Smyth, and L. Farrell. 2020. “Fuel Poverty and Subjective Wellbeing.” Energy Economics 86:104650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2019.104650.

- Cummins, R. A. 1995. “On the Trail of the Gold Standard for Subjective Well-Being.” Social Indicators Research 35 (2): 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01079026.

- Delhey, J., and G. Dragolov. 2016. “Happier Together. Social Cohesion and Subjective Well‐Being in Europe.” International Journal of Psychology 51 (3): 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12149.

- De Miquel, C., J. Domènech-Abella, M. Felez-Nobrega, P. Cristóbal-Narváez, P. Mortier, G. Vilagut, J. Alonso, B. Olaya, and J. M. Haro. 2022. “The Mental Health of Employees with Job Loss and Income Loss During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Perceived Financial Stress.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (6): 3158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063158.

- DHHSV. (2022). “Department of Health and Human Services Victoria ABS.” Accessed 2023. https://www.coronavirus.vic.gov.au/financial-support-and-emergency-relief.

- Diener, E. 1984. “Subjective Well-Being.” Psychological Bulletin 95 (3): 542. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542.

- Diener, E., and S. Oishi. 2000. “Money and Happiness: Income and Subjective Well-Being Across Nations.” Culture and Subjective Well-Being 185:218.

- Diener, E., E. M. Suh, R. E. Lucas, and H. L. Smith. 1999. “Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress.” Psychological Bulletin 125 (2): 276. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276.

- Dimaria, C. H., C. Peroni, and F. Sarracino. 2020. “Happiness Matters: Productivity Gains from Subjective Well-Being.” Journal of Happiness Studies 21 (1): 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00074-1.

- Folayan, M. O., O. I. Ibigbami, I. O. Oloniniyi, O. Oginni, and O. Aloba. 2021. “Associations Between Psychological Wellbeing, Depression, General Anxiety, Perceived Social Support, Tooth Brushing Frequency and Oral Ulcers Among Adults Resident in Nigeria During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” BMC Oral Health 21 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01871-y.

- Friedline, T., Z. Chen, and S. P. Morrow. 2021. “Families’ Financial Stress & Well-Being: The Importance of the Economy and Economic Environments.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 42 (S1): 34–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09694-9.

- Fujita, F., and E. Diener. 2005. “Life Satisfaction Set Point: Stability and Change.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88 (1): 158. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.158.

- Groarke, J. M., E. Berry, L. Graham-Wisener, P. E. Mckenna-Plumley, E. Mcglinchey, C. Armour, and M. Murakami. 2020. “Loneliness in the UK During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Results from the COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study.” Public Library of Science ONE 15 (9): e0239698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239698.

- Hamilton, C., and E. Rush. 2006. The attitude of Australians to happiness and social wellbeing. 21. Australia institute.

- Hoffman, G. R., G. M. Walton, P. Narelda, M. M. Qiu, and A. Alajami. 2021. “COVID-19 Social-Distancing Measures Altered the Epidemiology of Facial Injury: A United Kingdom-Australia Comparative Study.” British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 59 (4): 454–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.09.006.

- Huebener, M., S. Waights, C. K. Spiess, N. A. Siegel, and G. G. Wagner. 2021. “Parental Well-Being in Times of COVID-19 in Germany.” Review of Economics of the Household 19 (1): 91–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09529-4.

- Kennelly, B., M. O’callaghan, D. Coughlan, J. Cullinan, E. Doherty, L. Glynn, E. Moloney, and M. Queally. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic in Ireland: An Overview of the Health Service and Economic Policy Response.” Health Policy and Technology 9 (4): 419–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.021.

- Kumar, P., R. Pillai, N. Kumar, and M. I. Tabash. 2023. “The Interplay of Skills, Digital Financial Literacy, Capability, and Autonomy in Financial Decision Making and Well-Being.” Borsa Istanbul Review 23 (1): 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2022.09.012.

- Lewbel, A. 2012. “Using Heteroscedasticity to Identify and Estimate Mismeasured and Endogenous Regressor Models.” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 30 (1): 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2012.643126.

- Macreadie, I. 2022. “Reflections from Melbourne, the World’s Most Locked-Down City, Through the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond.” Microbiology Australia 43 (1): 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1071/MA22002.

- Martey, E., P. M. Etwire, and I. Koomson. 2022. “Parental Time Poverty, Child Work and School Attendance in Ghana.” Child Indicators Research 1–27. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4098011.

- Mccartan, C., T. Adell, J. Cameron, G. Davidson, L. Knifton, S. Mcdaid, and C. Mulholland. 2021. “A Scoping Review of International Policy Responses to Mental Health Recovery During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Health Research Policy and Systems 19 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00652-3.

- Montpetit, M. A., A. E. Kapp, and C. Bergeman. 2015. “Financial Stress, Neighborhood Stress, and Well‐Being: Mediational and Moderational Models.” Journal of Community Psychology 43 (3): 364–376. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21684.

- Moreno, C., T. Wykes, S. Galderisi, M. Nordentoft, N. Crossley, N. Jones, M. Cannon, C. U. Correll, L. Byrne, and S. Carr. 2020. “How Mental Health Care Should Change as a Consequence of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Lancet Psychiatry 7 (9): 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2.

- Muir, K., M. Hamilton, J. Noone, A. Marjolin, F. Salignac, and P. Saunders 2017. “Exploring Financial Wellbeing in the Australian Context. Report for financial literacy Australia.” Centre for Social Impact & Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

- Noble, K., P. Hurley, and S. Macklin. 2020. “COVID-19, Employment Stress and Student Vulnerability in Australia.”

- Norman, J. 2020. “Government considering radical measures to put economy into hibernation to survive coronavirus.” ABC News 28.

- O’connor, R. C., K. Wetherall, S. Cleare, H. Mcclelland, A. J. Melson, C. L. Niedzwiedz, R. E. O’carroll, D. B. O’connor, S. Platt, and E. Scowcroft. 2021. “Mental Health and Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Analyses of Adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing Study.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 218 (6): 326–333. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.212.

- Panchal, N., R. Kamal, K. Orgera, C. Cox, R. Garfield, L. Hamel, and P. Chidambaram. 2020. “The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use.” Kaiser Family Foundation 21.

- Papp, L. M., E. M. Cummings, and M. C. Goeke‐Morey. 2009. “For Richer, for Poorer: Money as a Topic of Marital Conflict in the Home.” Family Relations 58 (1): 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00537.x.

- Patra, S., P. Mishra, S. Mahapatra, and S. Mithun. 2016. “Modelling Impacts of Chemical Fertilizer on Agricultural Production: A Case Study on Hooghly District, West Bengal, India.” Modeling Earth Systems and Environment 2 (4): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-016-0223-6.

- Payne, J. L., A. Morgan, and A. R. Piquero. 2020. “COVID-19 and Social Distancing Measures in Queensland, Australia, are Associated with Short-Term Decreases in Recorded Violent Crime.” Journal of Experimental Criminology 1–25.

- Pereira, M., and A. M. Oliveira. 2020. “Poverty and Food Insecurity May Increase as the Threat of COVID-19 Spreads.” Public Health Nutrition 23 (17): 3236–3240. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020003493.

- Prakash, K., S. A. Churchill, and R. Smyth. 2020. “Petrol Prices and Subjective Wellbeing.” Energy Economics 90:104867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104867.

- Qian, Y., and W. Fan. 2020. “Who Loses Income During the COVID-19 Outbreak? Evidence from China.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 68:100522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100522.

- Rossell, S. L., E. Neill, A. Phillipou, E. J. Tan, W. L. Toh, T. E. Van Rheenen, and D. Meyer. 2021. “An Overview of Current Mental Health in the General Population of Australia During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the COLLATE Project.” Psychiatry Research 296:113660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113660.

- Santomauro, D. F., A. M. M. Herrera, J. Shadid, P. Zheng, C. Ashbaugh, D. M. Pigott, C. Abbafati, C. Adolph, J. O. Amlag, and A. Y. Aravkin. 2021. “Global Prevalence and Burden of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in 204 Countries and Territories in 2020 Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Lancet 398 (10312): 1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7.

- Sepúlveda-Loyola, W., I. Rodríguez-Sánchez, P. Pérez-Rodríguez, F. Ganz, R. Torralba, D. Oliveira, and L. Rodríguez-Mañas. 2020. “Impact of Social Isolation Due to COVID-19 on Health in Older People: Mental and Physical Effects and Recommendations.” The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 24 (9): 938–947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1500-7.

- Sjøgaard, G., J. R. Christensen, J. B. Justesen, M. Murray, T. Dalager, G. H. Fredslund, and K. Søgaard. 2016. “Exercise is More Than Medicine: The Working Age Population’s Well-Being and Productivity.” Journal of Sport and Health Science 5 (2): 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2016.04.004.

- Szkody, E., M. Stearns, L. Stanhope, and C. Mckinney. 2021. “Stress‐Buffering Role of Social Support During COVID‐19.” Family Process 60 (3): 1002–1015. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12618.

- Toffolutti, V., S. Plach, T. Maksimovic, G. Piccitto, M. Mascherini, L. Mencarini, and A. Aassve. 2022. “The Association Between COVID-19 Policy Responses and Mental Well-Being: Evidence from 28 European Countries.” Social Science & Medicine 301:114906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114906.

- VC. (2023). “Victorian COVID-19 Data.” Accessed 2023. https://www.coronavirus.vic.gov.au/victorian-coronavirus-covid-19-data.

- Wang, J., J. Yang, and Y. Xue. 2017. “Subjective Well-Being, Knowledge Sharing and Individual Innovation Behavior: The Moderating Role of Absorptive Capacity.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 38 (8): 1110–1127. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-10-2015-0235.

- Watson, T., and P. Buckingham. 2023. “Australian Government COVID‐19 Business Supports.” Australian Economic Review 56 (1): 124–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8462.12504.

- Welsch, H., and P. Biermann. 2017. “Energy Affordability and Subjective Well-Being: Evidence for European Countries.” The Energy Journal 38 (3): 159–176. https://doi.org/10.5547/01956574.38.3.hwel.

- WHO.2023. WHO COVID-19 dashboard.

- Winkelmann, R. 2009. “Unemployment, Social Capital, and Subjective Well-Being.” Journal of Happiness Studies 10 (4): 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9097-2.

- Wrosch, C., and M. F. SCheier. 2020. “Adaptive Self-Regulation, Subjective Well-Being, and Physical Health: The Importance of Goal Adjustment Capacities.” In Advances in Motivation Science. Elsevier.

- Xie, X., M. Xie, H. Jin, S. Cheung, and C.-C. Huang. 2020. “Financial Support and Financial Well-Being for Vocational School Students in China.” Children and Youth Services Review 118:105442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105442.

- Zhang, Z., and J. Zhang. 2015. “Social Participation and Subjective Well-Being Among Retirees in China.” Social Indicators Research 123 (1): 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0728-1.

Appendix

Table A1. Description and summary statistics for all the variables.