ABSTRACT

This article examines how sub-national policy is applied in consenting decisions for major wind energy infrastructure. The study focuses on the Welsh tier of governance and the perspective of the public, building on existing work on ‘territorial politics’ and public participation. It looks explicitly at the regulatory stage of decision-making, which is critical to understanding multi-level governance contexts for energy infrastructure. Two cases of ‘Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects’ (NSIPs) in the UK are assessed and findings show how conflict is fuelled by the ways in which different tiers of policy and regulation interact.

1. Introduction

Climate change strategies increasingly rely on the delivery of major energy infrastructure (Marshall, Citation2013), and research into the different levels of government that are involved has frequently used a multi-level governance (MLG) framing (Sovacool & Brown, Citation2009). However, as explained below, MLG needs to look beyond policy and give an account of the regulatory aspect of decision-making. Planning research has typically focused on societal goals within energy governance systems, including the construction of strategy and barriers to success. A policy can provide rules designed to shape infrastructure but in practice regulation will vary for each project. In the UK, regulation is procedurally separate from strategy, and policy is applied on a case-by-case basis. In such systems, a regulator’s assessment of any development applications centers on what Janin Rivolin terms the ‘performance’ (Janin Rivolin, Citation2008, Citation2017) of strategies at different governance levels. This article builds on the existing body of energy governance research, by looking explicitly at regulation. In light of recent research, it pays particular attention to sub-national level policy and the perspective of the public.

The study addresses the debates over the ‘scalar appropriateness’ of the sub-national tier of governance for major renewable energy infrastructure. In the European planning context, the scale of governance is a central concern (Marshall, Citation2014), and there are great conflicts of ‘territorial politics’ over the role of sub-national scale (Cowell et al., Citation2017). For decisions on renewable energy infrastructure, public response is an especially important factor (Cowell, Citation2010). The article offers an empirical study of the Welsh tier of governance in two decisions to consent major wind farms in Wales. Findings suggest that conflict is fuelled by interpretations of how policy and regulatory aspects of the wider system governance interact.

At the same time, the study offers insights into public perspectives on decision-making at the regulatory stage. This is an important facet of the research, as views on processes inevitably feed into ‘social acceptance’ as has been demonstrated for wind farms decisions (Bell et al., Citation2013). In addition, where the public is participating in decision-making and perceives processes not to be meaningful it poses a direct challenge to the legitimacy of planning (Natarajan et al., Citation2018), which ought to be considered in debates over governance. Significant steps have been taken to bring the public into decision-making at different governance levels, including into ‘Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects’ (NSIPs) in the UK (Lee et al., Citation2018; Rydin et al., Citation2015). The success of different types of participation is a matter of continued debate, including in this journal which has provided critiques of participation in planning (Brownill & Parker, Citation2010), including specifically for policy-making (Wilker et al., Citation2016) and regulatory stages (Sheppard et al., Citation2015). This article examines public perspectives where the public is involved in a particularly complex system of decision-making at different governance levels.

Following this introduction, this article considers NSIPs regulation of onshore wind farms in Wales. Two cases of ‘Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects’ (NSIPs) from 2012 and 2013 are examined. These consist of the decision-making on development applications for major new wind energy infrastructure in Wales, and public perspectives on these processes. The empirical data comes from archive material and Focus Groups with people who had been involved in the regulatory processes established by the Planning Act 2008. The study starts with a discussion of Welsh wind energy governance ‘level’ and public perspectives, focusing on the time of the case work. It then conceptualizes the multiple levels of decision-making for renewable energy infrastructure in the UK for that same period, and then discusses public perspectives. The rest of the article surrounds the empirical work, presenting the methodology and discussing the findings before pulling together conclusions and their theoretical and practical implications.

2. Governance and Perspectives on Welsh Wind Energy

The scalar appropriateness of different governance tasks for wind energy infrastructure has repeatedly come under question in the UK. As a result, the levels of the system for making decisions are continually being reworked. The implications of the resulting policy instability continue to be debated (Cowell, Citation2017) and this article adds to those debates with a study of the regulatory stage of decision-making. This section sets the scene, drawing on recent literature on energy governance. It considers multi-level governance and issues for Wales in particular, and it discusses the ways in which critical public perspectives are a prominent consideration.

Energy infrastructure is fundamentally a network phenomenon, characterized by physical interconnectedness and the involvement of multiple actors, and consequently it makes a specific call on governance at several regulatory levels (Goldthau, Citation2014). Thus, the ‘organising perspective’ offered by multi-level governance (Bache & Flinders, Citation2004) can help to explain dispersal of authority, and consider the strengths and weaknesses of the system. MLG literature stemming from studies of governance in late 20th Century Europe (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2003) offers a conceptualization of the distribution of authority at multiple levels of policy and an assessment of how this may or may not help move towards sustainability goals (Kates & Wilbanks, Citation2003). MLG has helped build an understanding of the ‘the complex web of interwoven jurisdictional boundaries’ (Bache & Flinders, Citation2004) and areas where concerns might be anticipated. As set out here, lessons from Hooghe & Marks’ study of the EU’s integration goals (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2003) continue to have relevance and inform more recent works in relation to systems of energy governance. However, they tend to emphasize policy-making and give relatively little attention the regulative aspects of infrastructure planning and their implications for the realisation of policy.

MLG examinations of dispersed authority challenge any presumption of dominant centralized power, because they explain governance capacity in terms of the ability to control and steer decisions at different scales. They move discussion away from the effects of supposedly linear hierarchies to the political powers at different points in complex systems and the influence of their associated actors (Bache & Flinders, Citation2004). The case for higher level policy continues to be made internationally, for instance in relation to difficulties in moving towards climate change objectives experienced in federal systems due to a lack of comprehensiveness in strategy (Ohlhorst, Citation2015), or a lack of leadership at local levels as seen for instance in New Zealand (Harker et al., Citation2017). However, MLG studies emphasize the essential inefficiency of policy at the higher scales, as national and international strategies do not necessarily in themselves produce delivery on their goals (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2003). This is particularly so for the field of energy infrastructure (Ringel, Citation2017) and environmental protection (Lockwood, Citation2010), as projects must be evaluated and implemented at ‘lower level’ scales. Examining diverse tiers of authority, therefore, gives fuel to hopes of subsidiarity, whereby authority would sit at the sub-national scales that relate to a range of governance tasks and thus be closer to citizens or require more direct engagement of stakeholders.

When seen through an MLG lens, Wales sits at the ‘regional’ tier, i.e. between smaller ‘local’ tiers and that of the UK as a whole. This article uses the terms ‘regional’ and ‘sub-national’ to distinguish it from the national UK tier, but with the significant caveat that Wales is properly referred to as a nation as can be seen in documentation from every scale of UK government. This already points to problems of territorial politics found at this level of governance. More instrumental questions persist aboutthe reservation of decision-making to the UK tier, i.e. in terms of delivering change on the ground. It is asked for instance whether a lack of legal agency on the part of the Welsh Assembly Government to plan for large projects resulted in delays to delivery (Muinzer & Ellis, Citation2017). More importantly here, MLG work suggests that inter-tier conflict will arise where regional actors have a role in delivering a transition to wind energy, and that the tensions are not wag limited to relationships with the centre, i.e. between the Welsh Government and Westminster (Bache & Flinders, Citation2004). Further, accounts of devolution in Wales suggest energy policy at the regional level is embroiled in territorial politics.

Much attention has been paid to the political construction of the territorial reach of energy policy (Bridge et al., Citation2013; Cowell, Citation2017). There has been a rich seam of work on the Welsh level of wind energy policy, which appeared within the NSIPs decision-making system (detailed in the next section). Welsh strategies were bound up with devolution and the associated political reworkings of relationships in the UK. Research into the UK’s ‘energy constitution’ portrays sub-national energy policy as part of going devolutionary ‘struggles’ (Muinzer & Ellis, Citation2017). For the most part, as Cowell et al. point out, devolution ‘represents a transfer of who exercises powers at a given level, for a territory, rather than necessarily a redistribution of powers to or from that level’ (Cowell et al., Citation2015). A rare but important exception is the locational policy ‘Technical Advice Note 8ʹ (TAN 8). This gives guidance for siting wind farms within Wales and provides seven strategic site areas (SSAs), as preferred sites for wind farms. It aims to create differences at the local tier of local planning practice, and therefore merits particular attention.

The argument has been well made that the Welsh Government has been seeking creative approaches to influence energy matters for some time (Jenkins, Citation2005). These approaches appear within spatial planning at the subnational tier (Jenkins, Citation2014). For the period of this study, energy matters were not devolved to Wales, but a line of accountability to the Welsh Government had been created by connecting energy policy to economic policy. For instance, the Welsh Energy Policy Statement insisted that, ‘we will ensure that this transition to low carbon maximizes the economic renewal opportunities for practical jobs and skills, strengthens and engages our research and development sectors, promotes personal and community engagement and helps to tackle deprivation and improve quality of life.’ (p.5). This has led to a particular type of scepticism over Welsh energy strategy, which is cast as part of a trend of neoliberalization on the basis that it effectively puts energy governance at the service of capital (Haughton et al., Citation2010).

Little research exists on the regulatory performance of sub-national wind energy strategy, which might demonstrate its effectiveness in substantive terms. It is self-evident that in order to achieve the wider goal of energy transition, individual projects must be delivered. In this study, granting consent for ‘rule compliant’ wind farms indicates the application of wind energy policy in real terms. As described in the next section, the system of decision-making for major infrastructure in the UK has a distinct regulatory stage, with a planning examination where policy can be considered and applied to projects. Given that the very notion of an ‘all-Wales view’ on wind farms can be seen as a political judgment (Cowell, Citation2007), difficulties can be anticipated. As already indicated, claims to nationhood for the ‘region’ of Wales are writ large across Welsh policy narratives (Harris & Hooper, Citation2004), but highly contested in terms of authenticity (Cowell, Citation2010). In addition, the legitimacy of stakeholder representation has been challenged (Cowell et al., Citation2015).

Lower tiers have increasingly been influencing the shape of decision-making systems for wind farms, including a recent downwards shift in the regulatory processes within Wales. In contrast to earlier strengthening of top-down mechanisms (Cowell, Citation2007) there is a trend of localization in the UK (Cowell, Citation2017). Research has shown that this is partly on account of public responses to the procedural and substantive outcomes of energy governance. In Wales upper development limits were placed on TAN 8’s strategic site areas (Cowell, Citation2017). In England and Wales onshore wind decisions are, at the time of writing, devolved to local planning (Lee, Citation2017). Most recently, all wind energy projects in Wales or Welsh Waters are decided by the Welsh Government,Footnote1 who seek further changes in the form of a ‘one-stop shop’ for Wales. They argue that this will help in addressing issues of concern to local communities and make the system more easily comprehensible to the general public.Footnote2

Public perceptions of decision-making on wind farms have primarily been studied in relation to siting decisions, but in system-oriented research views about policy also need to be addressed. There has been work on the substance and process of decisions on siting. Social acceptance studies most often present local communities as a source of opposition in particular instances of development (Fast, Citation2013). In recent work on the NSIPs system, the weak position of evidence from the public is contrasted to the extremely powerful professional actors promoting wind farm projects (Rydin et al., Citation2018a). However, siting decisions bring out issues of ‘territoriality’, i.e. the exercise of social and political powers over space (Brenner, Citation2004), and public responses to these. Studies of energy systems suggest that views on project siting decisions are inextricably bound up with views on governance; controversies ‘relate to wide reproduction of systems of provision’ (Cowell, Citation2017), rather than being ‘problems to solve’ (Aitken, Citation2010a). Studies of decision-making on wind farms in Wales has demonstrated how conflict around landscape issues co-constructs notions of justice (Mason & Milbourne, Citation2014) and critiqued attempts at consensus or ironing out of contestation (Stevenson, Citation2009; Cowell, Citation2007). Concerns surround the participatory processes for the development of spatial policy (Stevenson, Citation2009; Cowell, Citation2007) and consequent empowerment of tiers of Welsh actors due to the strength of focus on developing a policy stakeholder community (Haughton et al., Citation2010) and consequent involvement of non-government actors and professionalization of processes (Healey, Citation2008; Harris & Thomas, Citation2009). This raises doubts over the sensitivity of Welsh tier to lower tiers of governance and communities, which is an important consideration of this article.

The question at hand is how Welsh powers around wind energy decision-making might become manifest within a context of multiple levels, where public perceptions of legitimacy are paramount. The decision-making context comprises the making and application of policy, including planning strategies and consenting decisions. Regulation is key as it shapes the delivery of policy. As noted in the introductory section, consenting decisions may be steered by policy but the ‘steering’ is not always performed within the policy itself but (as is the case in the UK) on its application (Janin Rivolin, Citation2008, Citation2017). Yet regulation has been almost invisible in the MLG and Welsh policy literature. This article examines the NSIPs system in operation in Wales, and in the next section it unpacks the actors and processes involved in the tiers of policy and regulation.

3. The NSIPs Regime, Wind Energy in Wales

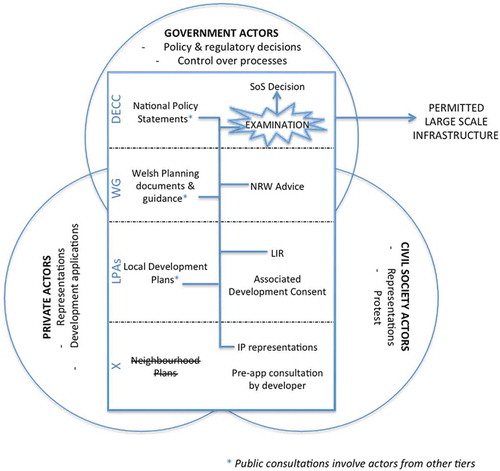

This section presents the ‘Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects’ (NSIPs) system of decision-making for major infrastructure projects in England and WalesFootnote3 introduced through the Planning Act 2008, and reflects on the interlocking sets of policy and regulatory decisions. The NSIPs regime has a complex set of national and subnational policies and regulatory processes, depicted in . Guided by multi-level governance studies, the actors at central, regional, local and community level tiers are considered. Infrastructures permitted under the system include energy, transport, waste, water, wastewater and business and commercial projects, but the focus here is wind energy. As noted earlier, systems suffer from instability and the NSIPs regime has been variously reworked for energy decisions since its introduction and this description is limited to 2012/2013 (when the two cases being studied were consented).

Considering first the national level of the NSIPs system, National Policy Statements (NPSs) are key. The NPSs relevant for wind farms are EN-1 on energy (Citation2011b) and EN-3 on renewables (Citation2011a) provided by the Department for Energy and Climate ChangeFootnote4 (DECC). Generating capacities are used to define which energy projects are NSIPs. At the point of this study EN-3 was the point of reference and set the threshold at 100 Mw for offshore and 50 Mw for onshore wind energy projects. The Climate Change Act 2011 imposed binding targets of carbon reduction, thus firmly rooting renewable energy infrastructure (REI) decision-making in the mission of energy transition emanating from the EU and national tiers of governance. The resulting strength of presumption in favour of REI raised questions about the nature of public input to decisions on projects, i.e. if debate was in effect limited to ‘how’ and not ‘whether’ to consent developments (Rydin et al., Citation2015). This reflected the challenges to planning the wider UK level context, where regulation was seen as a barrier to REI as noted particularly in the rhetoric of DECC and the Committee on Climate ChangeFootnote5 (Lee et al., Citation2013).

Consenting powers for NSIPs reside with the Secretary of State (SoS) for DECC as per the Planning Act 2008 (TSO, Citation2008), amended by the Localism Act (TSO, Citation2011). The SoS receives guidance and a reasoned recommendation from the National Planning Inspectorate (PINS), via a report from a planning examination. The examination is conducted by an Examining Authority (ExA), consisting of an individual planning inspector or panel of inspectors appointed by PINS, and can last up to six months. The ExA must refer to the NPSs and planning documents at all tiers, and consult with statutory and non-statutory parties, including the nature conservation bodies (i.e. Natural Resources Wales for projects proposed within Wales). Interactions happen mainly through the exchange of documents and written questioning but also through oral representations at hearings. Previous work has shown that Statements of Common Ground between parties and in-person representations at hearings are particularly important (Rydin et al., Citation2018b).

At the regional tier, Welsh policy had importance for energy infrastructure during the study period, as discussed above. The first Government of Wales Act (TSO, Citation1998) established a legislature in the devolved National Assembly for Wales and the second such Act (TSO, Citation2006) created an executive body in the Welsh Assembly Government (WAG), although the UK Parliament remained sovereign. The Welsh strategies were more spatially explicit than the NPS, since they were cemented in planning and locational guidance. The key documents were Planning Policy Wales (PPWFootnote6), the Wales Spatial Plan (Citation2008) and Technical Advice Note 8 (TAN 8), which established guidance on the potential and capacity for wind farm development for seven Strategic Search Areas (SSAs). The WAG’s renewable energy aspirations (articulated in Energy Wales: A Low Carbon Transition 2012) were highly ambitious and intended to go beyond international commitments.

The Welsh Government (WG) had a secondary role at the regulatory stage of NSIPs decision-making. Welsh planning documents were a material consideration in the PINS examination and ExAs also communicated directly with the WAG asking questions. However, the NPS were very vague on how Welsh planning policy and advice should be applied, They stated simply that for projects in Wales, they ‘will provide important information to applicants’ (EN-3, p.7) and the ExA should ‘have regard’ to it (ibid).

At the local tier, Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) are the key statutory actors and their role is mainly to provide a steer on ‘local detail’ in areas where development is proposed. LPAs develop Local Plans and participate in consultations on policy at other tiers. In Wales, the LPAs (County, County borough and City Councils) also participate in consultations on Welsh energy policies, and are expected to ‘undertake local refinement within each of the SSAs in order to guide and optimise development within each of the areas.’ (TAN 8, p.5). Secondly in consenting decisions, LPAs are expected to provide a Local Impact Report (LIR) for the examination. These LIR explain the local planning context, including the relevant planning documents, and how a proposed development will impact the locality. In Wales, during the study period LPAs also held responsibility for ‘associated development’, such as NSIP sub-stations and connections to the national energy grid. Thus, the UK Parliament retained control over the generating stations, but authority over local detail sat at the local tier.

The final level in the NSIPs system is the neighbourhood tier. In England, communities have statutory Neighbourhood Planning powers (see Wargent & Parker, Citation2018 for a critical discussion of current practice). While few Neighbourhood Plans had been developed at the point of the cases, the system nonetheless provided for these to be considered at the regulatory stage. However, these powers did not exist in Wales, which was a matter of concern to local communities (as discussed in the next section). Other opportunities for community involvement in NSIPs exist through participation in consultations on national energy policy and involvement in NSIPs examinations. A pre-application consultation is run by the prospective NSIP applicant. Local people are encouraged to participate and it is hoped that concerns can be dealt with prior to the examination. Further, members of the public who live, work or have an interest in the locality of the proposed development can, and often do (Natarajan et al., Citation2018), make written and oral representations in the examination, after registering as an Interested Party (IP).

On reflection, the NSIPs system as operating in 2012/2013 for wind farm development in Wales was fundamentally centralized. Decision-making powers sat with the UK government, which retained control over both energy policy and major development decisions. The regional tier in Wales was aspirational, consisting primarily of policy and leaving the specifics of project details to local policy and national regulation. Its rules were to be implemented by regulatory processes at the central and local tiers. This article now moves on to examine two empirical cases, with particular attention to the regional tier and perspectives from local communities on the system.

4. Methods

The study draws on two empirical cases of NSIPs, which were consented by the SoS for DECC in light of the reasoned recommendation from PINS. Archive material from the planning examinations was used to examine how the Welsh strategies were operationalized. Focus groups provided data on public perspectives, which as discussed earlier is critical to issues of stability and accountability in energy governance systems. The following text describes the sources, means of analysis and limitations of these empirics.

The archive data used for the two cases comes from the publicly available ExA reports, from the PINS websiteFootnote7 as part of an ESRC-funded research project,Footnote8 along with 10 further REI cases of other infrastructures in Wales and England. All of the cases in the ESRC research were consented, except for Navitus Bay application for an offshore wind farm in the English Channel. The ExA reports contained significant volumes of material including the development consent order, in-depth consideration of representations from the actors involved, and structured reasoning on the recommendation given to the SoS. They were qualitatively coded using the NVivo software with a framework created inductively under five macro-codes (actors, impacts, evidence, processes and mitigation) and cross-checked for accuracy independently by two researchers. Text that was coded for Welsh actors and processes were brought into this analysis, which examined the reasoning of the ExA with reference to the role of the Welsh tier.

The focus groups data was also taken from the ESRC-funded research. These discursive research events were held for a sub-set of the cases, in order to provide data on views on the regulatory processes. Participants were Interested Parties (IP) from communities in the localities of the infrastructure projects, who were identified on the PINS website and responded to an invitation to attend a focus group, held near to them. The sample was built purposively to include individuals from the types of IP found in the records of the examination, i.e. with representatives of local businesses, local interest groups and individual residents, as well as male and female participants. The eventual sample across the two cases had 4 residents, 1 business person and 14 local interest groups, including amenity, environment and ad hoc campaigning groups. The discussions were audio recorded, transcribed and anonymized before analysis. A qualitative codeframe was developed by two members of the team and applied across all transcripts. Codes cut across different aspects of participation including resourcing, community relationships, examination experiences and text coded for evaluation of the decision-making were brought into the analysis.

The rest of the ESRC-funded study data that was not used in this article has been reported on in other publications (Lee, Citation2017; Natarajan et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Rydin et al., Citation2018b, Citation2017, Citation2018c; Lee et al., Citation2018; Rydin et al., Citation2018a). The findings indicated strong dissatisfaction amongst the public, including concerns over the representation of different interests (Rydin et al., Citation2018b, Citation2018c) and acknowledgement of spatial distribution impacts (Natarajan et al., Citation2019), which supports the present line of enquiry.

Two caveats need to be recognized in relation to the selected focus of this data, as described above. Firstly, the study is by definition limited to the national regulatory context for large-scale infrastructure at the time of the cases. It, therefore, cannot deal with issues around decision-making on other smaller scale infrastructure, although other work suggests these will be different (Graham et al., Citation2009; Aitken, Citation2010b), due to the different size and ownership models. While the NSIPs system continues for other infrastructures, the processes for deciding onshore wind energy infrastructure across England and Wales have been further devolved to LPAs and the Welsh Government. We consider implications of the findings for the devolved context in the concluding section. Secondly, the perspectives on the regulatory interface with policy are particular to those who remain involved at the regulatory stage and by definition the study looks at concerns that are not handled before then. It is important to recognize that other concerns will have been raised and dealt with, through mitigation secured at the pre-application consultation stage. Focus group participants all expressed concern in relation to the impacts of the development, as was expected due to their involvement in the examination. So it should be noted that the views of people whose concerns had been resolved might be very different (Firestone et al., Citation2012).

5. Findings and Discussion

This section deals with the two empirical cases, the Brechfa Forest West Wind Farm and the Clocaenog Forest Wind Farm (Brechfa and Clocaenog for brevity from here on). It presents first the ExA reports, then the focus groups transcripts. Quotations from the focus groups indicate the type of participant, i.e. whether the person speaking identified themselves as a local resident, business representative or from a local group.

5.1. ExA Reports

In these reports, the ExAs gave a full record of the examination of the REI application, including their considerations of different tiers of policy. Analysis centred on the reasoning for the application of Welsh policy in the case and deliberations around that.

Welsh policy was considered ‘relevant’ by the ExAs, as stipulated by national policy (EN-03), and said to hold weight. Most notable was the use of Strategic Search Areas (SSAs) for Wind Farm development in Wales TAN 8, as the proposed sites of both the wind farms fell within SSA boundaries. The ExAs made positive statements about TAN 8, arguing that it ‘should be given considerable weight’ (Clocaenog p.21) and defending its validity when local actors challenged its substance. In Clocaenog, interested parties (IP) suggested Tan 8 was not sufficiently detailed or up-to-date. However, the ExA argued that, ‘technical work [behind TAN 8] accords with the approach required in NPS EN-1 and EN 2 [and] relevant policy guidance is set out in the adopted local development plans for both [Local County] Councils’ (Clocaenog p.31). Similarly in Brechfa, IP wanted a review of TAN 8 in light of the debates over SSA capacity limit that were being generated at that time by the level of interest being expressed by potential developers. A review was not considered, and the extant policy was applied.

While Welsh policy was rhetorically defended, it was attributed low significance in the reasoning. This meant that although it was applied, it was primarily used as an adjunct to UK policy. ExAs argued that Welsh policy wasn’t essential to their eventual judgement, stating for instance in Clocaenog, ‘EN-3 also states that whether an application conforms to the guidance or targets will not in itself be a reason for approving or rejecting an application’ (p.31). In effect Welsh policy was called on, but only where there was alignment between the regional and national tiers. This was seen for instance in both cases in relation to the typically contentious (Lee, Citation2017) issue of landscape impacts, which were deemed acceptable on the basis of the NPS EN-03 with TAN 8 to back it up (Clocaenog, p. 36, and Brechfa p.29).

It is of no surprise that national policy should dominate, given the hierarchy described in the previous section and research reporting on its strength (Rydin et al., Citation2015). However, in these two cases the regional tier appears to be in an overly subservient position. The strength of devolved planning policy, within this regulatory context, derived almost exclusively from national policy. Welsh policy arguably performed national policy, adding to its strength and supporting its objectives rather than providing a strong delivery of Welsh objectives. Further, national policy lent support to Welsh policy when it was called into question by local actors within Wales.

There were some exceptions to the ‘weak performance’ of Welsh policy, where National policy was silent. For some matters only fleshed out in Welsh policy, it was applied in its own right, for example, where PPW provided guidance on landscape assessment for Clocaenog (p. 34). More notably, the technical detail on the siting of wind turbines, regional policy was upheld over local policy. For turbines near to residential property, advice from the WG that stated ‘a rigid minimum separation distance could unnecessarily hinder the development of renewable energy projects in Wales’ (Brechfa, p.68). This was used against Carmarthenshire County Council’s argument that ‘large-scale wind power proposals should be located a minimum of 1500m away from the nearest residential property’ (Brechfa, p.15).

However, it was clear that planning considerations at the Welsh tier could be outweighed by national energy policy. In Brechfa, limits were proposed for the intensity of development in each SSA, both in TAN 8 and in a letter from the Welsh Minister for Environment and Sustainable Development. ExA argued that these could be breeched due to the ‘national need’ for energy. ‘While TAN8 is a relevant material consideration the main policy considerations are the national policy statements (NPS EN-1 and NPS EN-3) which identify the need for additional capacity’ (Brechfa, p.90). In Clocaenog, PPW’s line on ‘good neighbourliness’ was overruled by the ‘top tier’. ‘With the weight of national policy in favour of the project, I find that the wider public interest marginally outweighs the risk of harm to residential amenity.’ (Clocaenog, p.134)

In conclusion, the decision-making remained strongly centralized, and affected the rules offered in the Welsh policy and plans. In regulatory action more emphasis was placed on UK energy policy than Welsh planning, and national policy could override Welsh policy even where it offered no position on the matter at hand. In addition, energy strategy could eclipse (devolved) planning powers, and thereby ‘squeeze out’ potentially protective aspects of spatial strategy. Consequently, the devolved line of regional accountability for planning was blurred at the regulatory stage.

5.2. Focus Groups

The findings from the focus groups centre on participants’ views of the Welsh policy tier. In both cases, there was a strong relationship with people’s understandings of the wider system.

Respondents from across the two focus groups strongly perceived that consent for the development was a fait accompli. They felt alienated from the regulatory processes and a sense of mistrust and frustration. ‘Everything pointed to “it’s going to happen anyway” … a number of people said ‘there is no point of saying anything… there’s no point of us doing anything cause it’s going to happen anyway’ (Clocaenog, Group) ‘I think all the way through the process, because it’s so complicated and has so many stages, more and more people get to the point of thinking “It has already been decided.”’ (Brechfa, Group) While other aspects of the NSIPs processes, such as the volume of material and the status of lay knowledge, are known to raise concerns over being heard in the NSIPs (Rydin et al., Citation2018a), these challenges were very particular to Wales.

Broadly speaking, the participants were wary of the Welsh context of NSIPs, critiquing the sub-national elements as a means to smoothing the path to consent and avoiding opposition to projects from local people. TAN 8 appeared to be a ‘trump card’ that backstopped against challenge. As one participant put it, ‘as soon as it is covered by TAN 8 it is an automatic presumption in favour of the development.’ (Brechfa, Group). The use of local planning for associated development, which (as noted above) was intended to devolve detail, appeared presumptive. For instance, a participant said ‘there was no agreement on connection…that was to be debated elsewhere, the Grid connection, here we were debating, deciding on wind turbines, no Grid Connection! And that was to be at a separate PINS hearing later on. Well, you are saying, that’s not going to happen?’ (Clocaenog, Group). The missing Neighbourhood Planning tier of government added to the sense of foreclosure on communities. As one participant reported, ‘we got very excited last year with Greg Clark’s statement about “the community would prevail”, and we followed it up with emails to our local AMs [Assembly Members], MPs … and basically doesn’t apply in Wales’ (Brechfa, Group).

Participants argued that it was necessary to understand the Welsh Government’s (WG’s) position on the matter of Wind Farms in order to understand the NSIPs regime, saying for instance ‘TAN 8 then set the fuse for everything in Wales.’ (Clocaenog, Group) There was a strong suspicion in both cases that the proposed development was effectively a ‘done deal’ and two negative interpretations of the WG’s intentions. Some participants reported that the WG were ideologically driven, and others that the WG was being economically opportunist. The latter point related to WG ownership of forestland and NRW responsibility for forestry work at the sites of proposed development. People said for instance, ‘They cut down forests to replace them with wind farms. It is not a green activity. But is all about how the Welsh Government has manipulated Planning Policy for their own financial gain’ (Brechfa, Business). Both interpretations were used to support the argument that the WG had closed the door to any discussion of local people’s concerns in the particular cases under examination. In the words of one participant, ‘I think that England listens far more than Wales …we would have to like it or lump it’ (Clocaenog, Group).

The examination was a discreet part of the overall decision-making system, but some local stakeholders had been involved in earlier consultations on Welsh policy and appeared frustrated by the multiple interactions. People’s earlier exchanges with other authorities had created mistrust, which fed forwards into the regulatory processes. ‘I think it’s true to say with TAN 8 as well as with the specific wind farm to Brechfa the amount of pre-consultation information that was put out, the fact that TAN 8 was going to come into existence in the first place, was almost a well-kept Government secret’ (Brechfa Group). Decision-making felt ‘slippery’ in how it addressed local people’s concerns since, while many impacts were considered and mitigation provided, participants perceived the examination as yet another forum failing to deliver solutions for their issues. For instance, ‘Denbighshire County Council Hydrology Department said that it was very, very likely that they would lose a supply …This was brought up many, many times … but the only condition [the ExA] put in was that [the developer] was to liaise with Denbighshire County Council full stop.’ (Clocaenog, Resident). These findings suggest the public takes a situated view of decision-making, where there is an ongoing development logic. This echoes the critical distinction in situated planning theories, between ambiguity (where different frames exist) and historically situated disagreement where frames are in fact ‘interactional co-constructions’ (Brugnach et al., Citation2008; Dewulf et al., Citation2005).

In conclusion, interested parties (IP) perceived that there was a single centralized decision-making authority, which was insensitive to local issues. However, they attributed this to the Welsh rather than the UK Government. IP also perceived that the multiple tiers splintered processes, which enabled the avoidance of community concerns about wind farms. Finally, it is noteworthy that IP were attempting to act in a strategic manner, providing a voice on policy at higher tiers rather than conforming to the role of representing an individual interest, or playing out a false NIMBY stereo-type (Devine-Wright, Citation2009). Thus, while there was no neighbourhood planning policy, IPs representations attempted to provide an ad hoc ‘community tier’, albeit without presenting a formal strategy.

6. Conclusion

Multi-level governance studies have considered the tensions within governance systems in relation to interactions between different levels of policy. This study considered the interplay of tiers of policy and regulation. Previous work challenged assumptions about centralization and highlighted a range of actors involved in energy governance. By examining the regulatory stage of major wind energy infrastructure in Wales, this article has demonstrated how dispersed policy powers might not be delivered in practice. When the national, ‘regional’, and local tiers of governance interacted, the sub-national ‘spatial rules’ were substantively reworked. In the two Welsh cases, the NSIPs decision-making was centralized, and privileged the UK over the Welsh tier.

Members of the public who were involved in the national tier planning examination expressed strong views about the Welsh tier of the decision-making system. Their interpretations were rooted in historical conflict over the construction of Welsh energy strategy, and previous research suggested that it might be insensitive to local concerns. In practice UK principles of energy transition overshadowed planning concerns in the two cases. However, the focus groups perceived the Welsh Government to be in a very strong position at the examination stage. As a result the existing concerns about the intentions of Welsh planning actors increased. This also undermined the perceived meaningfulness of public involvement in the national tier processes.

These findings related to a particular point in time, and there have been subsequent changes to the system for deciding major wind energy infrastructure in Wales. At the time of the study campaigning was underway to de-centralize decisions, and since then all onshore wind energy projects in England and Wales with a generating capacity of at least 10 MW have been devolved. In Wales these are currently determined under processes of ‘Developments of National Significance’ (DNS) under the Planning (Wales) Act 2015, which mirror the NSIPs examination processes but with consenting powers devolved to Welsh Ministers. As of April 2019, under the Wales Act 2017 offshore stations up to 350 MW will also be DNS. Thus, the strong power of the Welsh tier within regulatory processes, which IPs anticipated, is now in effect.

In the new context, the relationships between national and Welsh actors are changed, and both regulatory and policy powers sit at the Welsh tier. The energy transition goals of the Welsh Government remain ambitious. The Welsh tier has direct control over how ‘regional’ and local strategies might be applied in decisions on projects, and therefore Welsh planning might have more weight within examinations, i.e. if expectations of subsidiary principles are correct. That is to say that Welsh regulators would be more likely to apply the protections offered by Welsh tier and local plans, such as siting turbines further from properties or limiting the density of development in preferred areas for development. Whether this would change public perspectives over the Welsh tier is less certain, due to the long history of conflict that exists and potential for people to interpret the new powers at the Welsh tier as a ‘fulfilled prophesy’.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the ESRC funding for the study of NSIPs, with the Award No. 164522, which made this work possible. Further details are available at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/nsips

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This is secured by the Planning (Wales) Act 2015 and the Wales Act 2017, with details prescribed in the Developments of National Significance (Specified Criteria and Secondary Consents) Regulations 2016.

2. As set out in the current Consultation Document, Consenting of infrastructure: Towards establishing a bespoke infrastructure consenting process in Wales.

3. As well as those that cross the border to Scotland.

4. This Department was disbanded in 2016 and the functions transferred to the new Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy.

5. The non-departmental public body with responsibility for reporting and advising on progress towards targets.

6. Edition 4 (Citation2011) is the relevant version for the empirical study and the original Planning Policy Wales of 2002 was revised eight times between 2010 and 2016. Edition 9 is in force at the time of writing.

References

- Aitken, M. (2010a) Why we still don’t understand the social aspects of wind power: A critique of key assumptions within the literature, Energy Policy, 38(4), pp. 1834–1841. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2009.11.060.

- Aitken, M. (2010b) Wind power and community benefits: Challenges and opportunities, Energy Policy, 38(10), pp. 6066–6075. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.05.062.

- Bache, I., & Flinders, M. (2004) Multi-level governance and the study of the British state, Public Policy and Administration, 19(1), pp. 31–51. doi:10.1177/095207670401900103.

- Bell, D., Gray, T., Haggett, C., & Swaffield, J. (2013, September) Re-visiting the ‘social gap’: Public opinion and relations of power in the local politics of wind energy, Environmental Politics, 22, pp. 115–135. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.755793.

- Brenner, N. (2004) New State Spaces (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Bridge, G., Bouzarovski, S., Bradshaw, M., & Eyre, N. (2013) Geographies of energy transition: Space, place and the low-carbon economy, Energy Policy, 53, pp. 331–340. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.10.066.

- Brownill, S., & Parker, G. (2010) Why bother with good works? The relevance of public participation(s) in planning in a post-collaborative era, Planning Practice and Research, 25(3), pp. 275–282. doi:10.1080/02697459.2010.503407.

- Brugnach, M., Dewulf, A., Pahl-Wostl, C., & Taillieu, T. (2008) Toward a relational concept of uncertainty: About knowing too little, knowing too differently, and accepting not to know, Ecology and Society, 13(2), pp. 1–30. doi:10.5751/ES-02616-130230.

- Cowell, R. (2007) Wind power and ‘the planning problem’: The experience of Wales, European Environment, 17(5), pp. 291–306. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0976.

- Cowell, R. (2010) Wind power, landscape and strategic, spatial planning-The construction of ‘acceptable locations’ in Wales, Land Use Policy, 27(2), pp. 222–232. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.01.006.

- Cowell, R. (2017) Decentralising energy governance? Wales, devolution and the politics of energy infrastructure decision-making, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(7), pp. 1242–1263.

- Cowell, R., Ellis, G., Sherry-Brennan, F., Strachan, P. A., & Toke, D. (2015) Rescaling the governance of renewable energy: Lessons from the UK devolution experience, Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 35(70), pp. 1139–1155.

- Cowell, R., Ellis, G., Sherry-Brennan, F., Strachan, P. A., & Toke, D. (2017) Sub-national government and pathways to sustainable energy, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(7), pp. 239965441773035.

- DECC. (2011a) National Policy Statement for Renewable Energy Infrastructure (EN-3) (London: HMSO (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office)).

- DECC. (2011b) Overarching National Policy Statement for Energy (EN-1) (London: HMSO (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office)).

- Devine-Wright, P. (2009) Rethinking NIMBYism: The role of place attachment and place identity in explaining place-protective action, Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 19, pp. 426–441. doi:10.1002/casp.1004.

- Dewulf, A., Craps, M., Bouwen, R., Taillieu, T., & Pahl-Wostl, C. (2005) Integrated management of natural resources: Dealing with ambiguous issues, multiple actors and diverging frames, Water Science and Technology, 52(6), pp. 115–124. doi:10.2166/wst.2005.0159.

- Fast, S. (2013) Social acceptance of renewable energy: Trends, concepts, and geographies, Geography Compass, 7(12), pp. 853–866. doi:10.1111/gec3.12086.

- Firestone, J., Kempton, W., Lilley, M. B., & Samoteskul, K. (2012) Public acceptance of offshore wind power: Does perceived fairness of process matter? Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 55(10), pp. 1387–1402. doi:10.1080/09640568.2012.688658.

- Goldthau, A. (2014) Rethinking the governance of energy infrastructure: Scale, decentralization and polycentrism, Energy Research and Social Science, 1, pp. 134–140. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2014.02.009.

- Graham, J. B., Stephenson, J. R., & Smith, I. J. (2009) Public perceptions of wind energy developments: Case studies from New Zealand, Energy Policy, 37(9), pp. 3348–3357. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.12.035.

- Harker, J., Taylor, P., & Knight-Lenihan, S. (2017) Multi-level governance and climate change mitigation in New Zealand: Lost opportunities, Climate Policy, 17(4), pp. 1752–7457. doi:10.1080/14693062.2015.1122567.

- Harris, N., & Thomas, H. (2009) Making Wales, in: S. Davoudi & I. Strange (Eds) Conceptions of Space and Place in Strategic Spatial Planning, pp.43–70(London: Routledge).

- Harris, N., & Hooper, A. (2004) Rediscovering the ‘Spatial’ in public policy and planning: An examination of the spatial content of sectoral policy documents, Planning Theory & Practice, 5(2), pp. 147–169. doi:10.1080/14649350410001691736.

- Haughton, G., Allmedinger, P., Counsell, D., & Vigar, G. (2010) The New Spatial Planning. Territorial Managent with Soft Spaces Andfuzzy Boundaries (Abingdon: Routledge).

- Healey, P. (2008) Knowledge flows, spatial strategy making, and the roles of academics, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 26(5), pp. 861–881. doi:10.1068/c0668.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2003) Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance, American Political Science Review, 97(2), pp. 233–243.

- Janin Rivolin, U. (2008) Conforming and performing planning systems in Europe: An unbearable cohabitation, Planning Practice and Research, 23(2), pp. 167–186. doi:10.1080/02697450802327081.

- Janin Rivolin, U. (2017) Global crisis and the systems of spatial governance and planning: A European comparison, European Planning Studies, 25(6), pp. 994–1012. doi:10.1080/09654313.2017.1296110.

- Jenkins, V. (2005) Environmental law in Wales, Journal of Environmental Law, 17(2), pp. 207–227. doi:10.1093/envlaw/eqi017.

- Jenkins, V. (2014) The proposals for the reform of land use planning in Wales, Journal of Planning & Environment Law, 10, pp. 1063–1080.

- Kates, R. W., & Wilbanks, T. J. (2003) Making the global local responding to climate change concerns from the ground, Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 45(3), pp. 12–23.

- Lee, M. (2017) Knowledge and landscape in wind energy planning, Legal Studies, 37(1), pp. 3–24. doi:10.1111/lest.12156.

- Lee, M., Armeni, C., de Cendra, J., Chaytor, S., Lock, S., Maslin, M., Redgwell, C., & Rydin, Y. (2013) Public participation and climate change infrastructure, Journal of Environmental Law, 25(1), pp. 33–62. doi:10.1093/jel/eqs027.

- Lee, M., Lock, S. J., Rydin, Y., & Natarajan, L. (2018) Decision-making for major renewable energy infrastructure, Journal of Planning and Environment Law, 5, pp. 507–512.

- Lockwood, M. (2010) Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: A framework, principles and performance outcomes, Journal of Environmental Management, 91(3), pp. 754–766. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.10.005.

- Marshall, T. (2013) The remodeling of decision making on major infrastructure in Britain, Planning Practice & Research, 28(1), pp. 122–140. doi:10.1080/02697459.2012.699255.

- Marshall, T. (2014) Infrastructure futures and spatial planning: Lessons from France, the Netherlands, Spain and the UK, Progress in Planning, 89, pp. 1–38. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2013.03.003.

- Mason, K., & Milbourne, P. (2014) Constructing a ‘landscape justice’ for windfarm development: The case of Nant Y Moch, Wales, Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 53, pp. 104–115. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.02.012.

- Muinzer, T. L., & Ellis, G. (2017) Subnational governance for the low carbon energy transition: Mapping the UK’s ‘Energy Constitution’, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(7), pp. 1176–1197.

- Natarajan, L., Lock, S. J., Rydin, Y., & Lee, M. (2019) Participatory planning and major infrastructure: experiences in renewable energy regulation, Town Planning Review, 90(2).

- Natarajan, L., Rydin, Y., Lock, S. J., & Lee, M. (2018) Navigating the participatory processes of renewable energy infrastructure regulation: A ‘local participant perspective’ on the NSIPs regime in England and Wales, Energy Policy, 114, pp. 201–210. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.12.006.

- Ohlhorst, D. (2015) Germany’s energy transition policy between national targets and decentralized responsibilities, Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences, 12(4), pp. 303–322. doi:10.1080/1943815X.2015.1125373.

- Ringel, M. (2017) Energy efficiency policy governance in a multi-level administration structure — Evidence from Germany, Energy Efficiency, 10(3), pp. 753–776. doi:10.1007/s12053-016-9484-1.

- Rydin, Y., Natarajan, L., Lee, M., & Lock, S. J. (2017) Artefacts, the gaze and sensory experience: Mediating local environments in the planning regulation of major renewable energy infrastructure in England and Wales, in: M. Kurath, M. Marskamp, J. Paulos, & J. Ruegg (Eds) Relational Planning: Tracing Artefacts, Agency and Practices, pp. 51–74 (Cham: Palgrave Mcmillan).

- Rydin, Y., Lee, M., & Lock, S. J. (2015) Public engagement in decision-making on major wind energy projects, Journal of Environmental Law, 27(1), pp. 139–150. doi:10.1093/jel/eqv001.

- Rydin, Y., Natarajan, L., Lee, M., & Lock, S. (2018a) Black-boxing the evidence: Planning regulation and major renewable energy infrastructure projects in England and Wales, Planning Theory & Practice, 19(2), pp. 218–234. doi:10.1080/14649357.2018.1456080.

- Rydin, Y., Natarajan, L., Lee, M., & Lock, S. (2018b) Local voices on renewable energy projects: The performative role of the regulatory process for major offshore infrastructure in England and Wales, Local Environment, 23(5), pp. 565–581. doi:10.1080/13549839.2018.1449821.

- Rydin, Y., Natarajan, L., Lee, M., & Lock, S. J. (2018c) Do local economic interests matter when regulating nationally significant infrastructure? The case of renewable energy infrastructure projects, Local Economy, 33(3), pp. 269–286. doi:10.1177/0269094218763000.

- Sheppard, A., Burgess, S., Croft, N., Sheppard, A., Burgess, S., & Croft, N. (2015) Information is power: Public disclosure of information in the planning decision-making process, Planning Practice & Research, 30(4), pp. 443–456. doi:10.1080/02697459.2015.1045225.

- Sovacool, B. K., & Brown, M. A. (2009) Scaling the policy response to climate change, Policy and Society, 27(4), pp. 317–328. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2009.01.003.

- Stevenson, R. (2009) Discourse, power, and energy conflicts: Understanding Welsh renewable energy planning policy, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 27(3), pp. 512–526. doi:10.1068/c08100h.

- TSO. (1998) Government of Wales Act 1998 (London: TSO (The Stationery Office)).

- TSO. (2006) Government of Wales Act 2006 (London: TSO (The Stationery Office)).

- TSO. (2008) Planning Act 2008 (London: TSO (The Stationery Office)).

- TSO. (2011) Localism Act 2011 (London: TSO (The Stationery Office)).

- Wargent, M., & Parker, G. (2018) Re-imagining neighbourhood governance: The future of neighbourhood planning in England journal, Town Planning Review, 98(4), pp. 379–402. doi:10.3828/tpr.2018.23.

- Welsh Assembly Government. (2008) People, Places, Futures: The Wales Spatial Plan (2008 Update) (Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government).

- Welsh Government. (2011) Planning Policy Wales, 4thed (Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government).

- Wilker, J., Rusche, K., & Rymsa-Fitschen, C. (2016) Improving participation in green infrastructure planning, Planning Practice & Research, 31(3), pp. 229–249. doi:10.1080/02697459.2016.1158065.