ABSTRACT

The planning system in England is regarded as a key mechanism for the delivery of housing but is also seen by some as a brake on its supply. In this context, the introduction of neighbourhood planning in 2011 has been promoted as a mechanism to reduce opposition to new housing and aid housing growth. This paper focuses on how this policy tool has been implemented with a view to mobilising communities to assist in the allocation of housing sites. The paper draws on empirical data to illustrate the role, motivations, and response to neighbourhood planning and its impact on the delivery of housing.

Introduction

Many recent reforms to planning in England have been driven by the aim of increasing the supply of development sites and in particular the delivery of housing (Barker, Citation2008; Tait & Inch, Citation2016). Recent policy proposals published by the UK Government argued that ‘the planning process … fails to deliver enough homes where they are needed’ (MHCLG, Citation2020, para. 6). While debates have continued about such assertions, reforms introduced since 2010 have focused on ‘fixing’ the system, on the grounds that local planning represents an obstacle to growth. Reforms over the past decade in England include the introduction of the National Planning Policy Framework in 2012, the revocation of regional spatial strategies, increasing de-regulation through the expansion of permitted development rights, and a range of measures to ensure local planning authorities (LPAs) are delivering for their projected housing need. Furthermore, emphasis has been placed on the neighbourhood scale as a key site of policy delivery via the devolution of power and responsibility to communities in the service of growth goals (Gallent et al., Citation2013; Lord & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2014, Citation2018; Wargent, Citation2021).

In this paper, we discuss the aspirations of the UK Government towards neighbourhood planning (NP) and critically assess its claimed role in aiding housing delivery since its inception in 2011. The main contribution of this paper is to set out the most comprehensive analysis of the role of neighbourhood development plans (NDPs) in promoting housing growth through an assessment of residential site allocations in NDPs. From this, we illustrate the inadequacies of assessing the contribution of NP to housing supply policies at a national scale through quantitative analysis alone. We highlight associated housing policies in NDPs completed by 2020 and emphasise the contingencies involved in assuming that site allocations, or apparently positive housing policies in NDPs, equate automatically to net additional growth or actual completion of housing units.

The paper thereby provides evidence supporting wider arguments that planning policy tools should not be evaluated in isolation, but as part of an interdependent bricolage of actors, tools, policies, and institutions that shape the success of a given initiative or policy goal (Cleaver, Citation2017). The findings highlight how neighbourhood planning should be seen as part of a complex planning system, made up of multiple – sometimes conflicting – policy tools, which together are responsible for allocating potential development sites and shaping planning decisions. This leads to challenges when asserting NDPs contributions towards housing delivery through the allocation of sites and also highlights the importance of considering the contribution of broader policies in influencing the location and quantum of development. Therefore, claims made about the direct impact of NDPs on housing numbers need to be treated with caution. Efforts to understand impacts of individual policy mechanisms in isolation have been regarded as problematic, since:

Any attempt to augment quantitative models with planning indicators must be based on an appreciation of the scope of planning activities and on recognition of the potentially varied impacts of different dimensions of planning policy. (Jackson & Watkins, Citation2005, p. 1466)

As such, the paper argues that interdependencies lie within planning policy, as well as being contingent on factors beyond planning systems (e.g. Berisha et al., Citation2021) and efforts to isolate the role of NDPs in housing delivery belie the complex of factors that influence development in the English planning system and indeed internationally (see Healey, Citation1992).

Neighbourhood planning and housing

Neighbourhood planning, formalised through the Localism Act 2011 and amended under the Neighbourhood Planning Act 2017, provided, for the first time, the right for communities in England to prepare a statutory development plan for their locality. Once made, NDPs would be used in the determination of planning applications, alongside other relevant planning policies set at local and national levels. The policy was conceived as a tool to ‘nudge’ people into accepting more development

It is hoped that this will lead to behavioural change in such a way as to make local communities more predisposed to accept development. As a result, it is anticipated that greater community engagement, coupled with financial incentives, could lead to an increase in development. (DCLG, Citation2011, p.16).

When NP was first proposed, it was accompanied by a supporting rhetoric of empowerment (Wargent, Citation2021). Communities were to be provided with the right to decide how their area was to be developed via the production of a Neighbourhood Development Plan (NDP), a Neighbourhood Development Order (NDO) or a Community Right to Build Order (CRtBO) (Locality, Citation2016). This narrative can be seen within the definition and purposes of NP set out in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), as first iterated in 2012

…communities direct power to develop a shared vision for their neighbourhood and deliver the sustainable development they need. Parishes and neighbourhood forums can use neighbourhood planning to set policies through neighbourhood plans to determine decisions on planning applications…Neighbourhood planning provides a powerful set of tools for local people to ensure that they get the right types of development for their community. (DCLG, Citation2012, para. 184)

A similar sentiment has been maintained in revisions to the NPPF in 2018, 2019 and 2021. The accompanying impact assessment produced in advance of the NPPF in 2011 makes visible the wider objectives and purposes of NP

… resistance from local Neighbourhood Planning communities to proposals for housing and economic development within their neighbourhood is partly related to communities’ lack of opportunity to influence the nature of that development … [NP will] help communities to become proponents of appropriate and necessary housing and economic growth (DCLG, Citation2011, p. 2).

The underlying assumption was that communities would be more likely to accept development if incentivised and given the opportunity to plan for their area themselves (Gallent et al., Citation2013; Ludwig & Ludwig, Citation2014), with those opposed to development and pejoratively labelled ‘NIMBYs’ (representing the view ‘not in my back yard’) (see Inch, Citation2012) transformed into ‘responsible’ citizens and homebuilders (Matthews et al., Citation2015; Tait & Inch, Citation2016). Despite this being a key driver behind the policy, attempts to assess the actual role of NP in shaping housing supply, through an assessment of allocation of sites for housing development, have been limited (DCLG, Citation2015, Citation2016; Lichfields, Citation2018), often leaving more questions than answers, largely due to methodological flaws and limited sample sizes (Bradley & Sparling, Citation2017). It has also been seen as challenging due to the discretionary nature of UK planning, with numerous matters that can legitimately influence actual development – compounded by perpetual rounds of reform in the UK planning system (Parker et al., Citation2019).

This paper provides a detailed assessment of what housing has actually been allocated through NP, drawn from an extensive study of NDPs completed in 2020. This assessment deepens our understanding of the contribution of NDPs on planning for housing supply, including how many include housing targets, how many allocate sites, and their wider role in aiding sustainability agendas, for example by assessing the type of houses they are promoting. It identifies a need for a more nuanced approach when assessing NDP contributions towards housing supply, one that extends beyond a quantitative assessment of site allocations to include assessment of the broader suite of policies that influence the location and quantum of housing as well as the role of NDPs in decision-making. Furthermore, it highlights the complexities of measurement and isolating causality in a complex and changing system (see Parker et al., Citation2018), where local plans, housing allocations, and forecast need have all been in flux since 2011. Given this apparent policy bricolage, a series of questions are raised about: definitive claims regarding the added value of NDPs, who has meaningful control over housing delivery within any given area, what policy tools are active, and the cumulative effect of a continually shifting planning policy hierarchy and policy environment.

Literature and policy review

The literature on NP has burgeoned since 2011 (see Wargent & Parker, Citation2018). Here, we focus on outputs related to NP’s role in housing supply specifically. When the policy was introduced, the focus was on the right for communities to shape the development of their area. This is described by Tait and Inch (Citation2016) as the initial promotion of ‘Big Society’ localism. Within this narrative, NP was presented as a means of generating a more positive approach to development, in line with the priorities of economic growth and local autonomy (Wargent, Citation2021). As such, NP represents a more considered approach to incentivising local support of development than concurrent attempts to govern opposition to development via a purely economic rationality (see Inch et al., Citation2020).

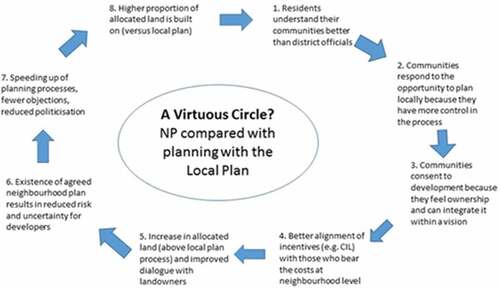

It was assumed that a key reason people objected to development was a response to concerns over the top-down manner in which decisions were reached in planning, with insufficient involvement of local communities (Sturzaker, Citation2011; Gallent et al., Citation2013; Ludwig & Ludwig, Citation2014). The logic therefore followed that resistance to development could be overcome by involving local people in decision-making and to ‘responsibilise’ communities (Pill, Citation2022). This in turn would provide greater certainty to both developers and communities, thereby delivering additional development over and above the local plan process. This is illustrated in the ‘virtuous circle’ conceptualised by DCLG (Stanier, Citation2014 and ).

Figure 1. Neighbourhood planning’s virtuous circle policy model, Source: Stanier (Citation2014, p. 113).

Local communities were also incentivised to take-up NP and allocate land for development (through amendments to the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL)Footnote1 which is a charge levied by LPAs on new development in their area). At the same time, certain boundary conditions were established within which groups had to operate (Bradley, Citation2015; Parker et al., Citation2015) providing a legal framework against which NDPs would be assessed at independent examination. These served to ensure NDPs did not counteract national growth priorities (Smith & Wistrich, Citation2016; Lord & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2018) and included the requirement for NDPs to be ‘positively prepared’, that is, they could not deliver less growth than indicated in the adopted local plan and must be in ‘general conformity’ with the strategic policies in that local plan and the NPPF.

The ‘virtuous circle’ model is conceptual and it is based on a number of untested assumptions, including the hypothesis that allocating sites in a neighbourhood plan can provide greater certainty for developers and reduced politicisation. The assumption being that this will in turn lead to a higher number of homes being built. The relationship between plan policies, site allocation and actual build-out is known to be complex with an entanglement of issues likely to be relevant (see Doak & Karadimitriou, Citation2007; Letwin, Citation2008). Furthermore, the policy model omits consideration of the wider structural inefficiencies of housing delivery. It isolates NP from local plan-making and crucially how housing numbers are calculated and distributed locally. This latter point is of particular importance as the model skirts over methodological challenges associated with determining housing numbers, consideration of the political nature of housing targets and challenges in disaggregating numbers to the local level (see Harris et al., Citation2018; Sgueglia & Webb, Citation2021).

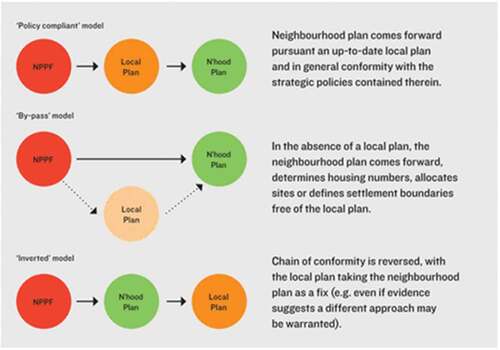

Furthermore, in reality, housing can be allocated by both the LPA and the community – that is, both tiers of the system are provided with the opportunity to identify sites as suitable for development and determine an indicative number of houses considered appropriate. It should also be noted that NDPs can be completed in advance of a local plan, which has implications for determining strategic priorities, including housing delivery. Lichfields (Citation2016a) argued that NDPs might ‘bypass’ the local plan or produce an ‘inverted’ model () whereby NDPs are made prior to the adoption of a local plan and thus shape its preparation and strategy, or conversely, that an emergent local plan may render NDPs in the area obsolete (or undermine its influence on decisions) once a local plan is adopted. Indeed, both things may occur; leaving identification of the role of either the NDP or local plan and the provenance of specific housing numbers and locations somewhat opaque.

Figure 2. The models of neighbourhood plan conformity, Source: Lichfields (Citation2016a, pp. 2-3).

The evidence suggests that many NDPs that are being prepared in advance of an up-to-date local plan may be seeking to fill a policy gap. In both 2016 and 2019, 29% of NDPs which passed referendum were in areas with no up-to-date local plan (Parker & Salter, Citation2017; Parker et al., Citation2020). Preparing an NDP in this way is challenging as the parameters within which the NDP must be prepared are likely to change as the local plan strategy emerges (Parker, Citation2012). Furthermore, many local plans experience problems at their examination by an appointed qualified examiner (Parker et al., Citation2016; Boddy & Hickman, Citation2018), including an increase in housing targets after submission (Lichfields, Citation2016b). This sets up the potential for NDPs to have a limited lifespan as their policies may then be superseded by the more recently adopted local plan – thus undermining community efforts (Bogusz, Citation2018).

More widely, NP is also influenced by broader central Government priorities and reforms of the planning system, which are increasingly directed towards pro-housing and pro-growth agendas (Slade et al., Citation2019). This includes the introduction of (and possible revisions to) a standardised methodology for assessing housing need, and secondly a presumption in favour of sustainable development in instances where an LPA cannot demonstrate a five year supply of deliverable housing sites2. These policy changes at LPA level often directly impact NDPs as development may be approved outside of the plan-led system, thus undermining the strategy and approach taken within the NDP (see Lees & Shepherd, Citation2015; NALC, Citation2018).

Housing delivery

Despite the intention for NDPs to deliver housing, there is little empirical evidence of their role in shaping housing supply through the allocation of sites. The main data published comprise two reports from DCLG (Citation2015, Citation2016) and a study by the planning consultancy Lichfields (Citation2018). These studies agree that NDPs that allocate sites for development are contributing towards housing supply and ostensibly delivering housing above the local plan target: in 2015, DCLG reported an increase of 11% and 10% in 2016, with the Lichfields (Citation2018) study identifying a lower contribution, with only 2.9% of NDPs delivering housing above the local plan target.

Caution is needed in comparing these figures as they are based on different methodologies and assumptions. For instance, the DCLG reports are based on a small sample where housing need is identified from adopted and emerging local plans, as well as wider sources such as strategic housing land availability assessments, and whether the sites already have planning permission is not considered (DCLG, Citation2015, Citation2016). Conversely, the Lichfields (Citation2018) study assesses housing delivery in areas with an adopted local plan only and where site allocations are ‘new’ (i.e. no extant planning permissions or existing local plan allocations).

While these studies illustrate that NDPs that allocate sites contribute positively towards the process of delivering housing, they also show that many NDPs are choosing not to do so by means of allocation. According to Lichfields (Citation2018), 60% of NDPs made by October 2017 did not include site allocations. Many reasons have been suggested for this, including caution from groups not wanting to launch debates they know to be conflictual (Vigar et al., Citation2012), a tendency for NDPs to repeat local plan policies rather than creating innovative and value-adding policy (Brookfield, Citation2017), the adoption of conservative positions to successfully navigate the NDP through the process (Parker et al., Citation2017), and the increased technical burdens associated with site allocations (Parker et al., Citation2014). Lichfields (Citation2018) conclude that part of the reason why NDPs rarely make ‘new’ allocations for housing is due to the slow local plan process, with a majority of NDPs coming forward ahead of their respective local plans.

This further highlights the broader complexity of isolating the contribution of NP towards housing delivery from the wider plan-making processes. Challenges include determining the objectively assessed need (OAN) for the neighbourhood area (LPAs have to make an objective assessment of the need for market and affordable housing and are directed by national policy to provide land to meet those needs insofar as they have sustainable capacity to do so), how many houses are to be allocated, and whether these are ‘new’ site allocations. These challenges are exacerbated in areas without an up-to-date local plan, leading Lichfields (Citation2018, p. 8) to conclude that whether ‘through absence or lack of up-to-datedness and clarity local plans are not effectively setting the agenda for neighbourhood planning and it makes the task of communities to identify “how much” all the more difficult.’

Place-making

While research which seeks to establish the quantity of housing putatively delivered by NDPs through site allocations is relatively limited, there has been wider academic interest in exploring the broader relationships between NDPs and housing delivery. Bailey (Citation2017) identified that whilst larger urban areas may identify suitable locations – and therefore allocate sites – for development to meet prescribed housing targets in the local plan, others provide general housing policies that seek to influence the type of development that will come forward. These policies typically relate to conditions to fulfil local needs, for example: the need for affordable housing, local occupancy conditions, housing for older people, and live/work units (Bailey, Citation2017; Field & Layard, Citation2017) leading Bradley and Sparling (Citation2017, p. 116) to conclude that some NDPs have ‘authored a spatial practice of housing delivery that resonated with the passion for place at the core of the localism agenda’ as groups aim to balance the ‘imperatives of house-building with the priorities of place identity, heritage and environmental protection’. This also includes small-scale custom-build housing (Bradley & Sparling, Citation2017) and opportunities for community-led housing (Field & Layard, Citation2017).

Thus, for some, the incentive for creating an NDP is not necessarily to guide where or how much development can take place (in terms of housing allocations per se), but to influence the type of development and to ‘shape’ their area based on their passion for place (Bradley & Sparling, Citation2017). Bradley (Citation2017) asserts that developments are more likely to win community support because they are based on a local vision of place and belonging. According to Bradley, it is this place-identity frame against which policies are evaluated and decisions made regarding the ‘specific sites for housing, the specification of the size of development and policies regarding the mode of delivery, its affordability and in relation to local need’ (Bradley, Citation2017, p. 244). The place-making and empowerment narrative has therefore provided NDPs space to support housing delivery which reflects local motivations and aspirations and in turn to promote a different ‘type’ of housing from the dominant market (Bradley & Sparling, Citation2017; Field & Layard, Citation2017). This clearly relates to the motivations of groups engaging in NP identified by Parker et al. (Citation2014).

However, in other areas, anxiety regarding development may be driving community activity. Brookfield (Citation2017), who reflected on the experiences in Leeds, called for a more nuanced assessment of NDP policies and consideration of their overarching intention and impact on development. Furthermore, Lichfields (Citation2012; Citation2018) and Turley Associates (Citation2014) also cautioned that many of the earlier NDPs were inherently protectionist and used as a tool to prevent or frustrate development, or to cause uncertainty to developers. Brookfield (Citation2017) reports that in some areas the threat of development may have prompted some areas to develop a NDP as a mechanism to protect their area, which may not align with pro-growth sentiments and agendas. Similarly, Parker and Salter (Citation2016, p. 186) caution that the combination of policies in an NDP could actually serve to ‘deter or frustrate development while appearing to be development friendly’ pointing to a need to assess the suite of policies within an NDP to determine their potential impact on housing delivery. This highlights the importance of the independent examination, as emergent NDPs are assessed against the legal framework established to ensure national growth priorities are not counteracted (Smith & Wistrich, Citation2016; Lord & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2018) and indeed the consistency and standards that are upheld at that stage of NDP production (Parker et al., Citation2016).

Neighbourhood development plans can affect the future development of housing in less direct ways, for instance, by designating sites as ‘Local Green Spaces’, including policies that shape settlement boundaries, and producing criteria-based policies. The inclusion of such policies may influence the delivery of prospective site allocations and housing delivery within the locality.

Methods

This remainder of this paper is based on the comprehensive review of the impact of NP commissioned by MHCLG (see Parker et al., Citation2020). It involved the evaluation of all NDPs that had passed referendum and allocated sites for housing between mid-2014 and mid-2018. In total, 141 NDPs qualified, representing 24.7% of all NDPs that passed referendum during this time-period (n = 571). In terms of their geography, the eligible NDPs are located within 56 LPAs across England, with the majority in South East England (40%), and a significant proportion in the East Midlands (19%), South West (14%) and West Midlands (18%). A significant majority of the NDPs were in Parished areas (n = 136) with only 5 NDPs progressed by Neighbourhood Forums (i.e. in unparished areas), reflecting the broader trends in NP take-up (Parker & Salter, Citation2017). The date range for this sample was carefully selected: experiences prior to mid-2014 have been well researched (see Parker et al., Citation2014), whilst insufficient time had passed at the time of the research for NDPs made post mid-2018 to have had meaningful impact on development.

A desktop study was undertaken to ascertain key quantitative data including the number of sites allocated, types of housing policy, types of housing to be delivered, and other housing-related policies designed to influence the shape of development (e.g. design and density policies). Data was also collected about the relevant LPA and wider planning policy framework (e.g. type and status of local plan being progressed and OAN for the neighbourhood area).

The OAN was identified from the adopted or emerging local plan. The housing requirement figure was derived after completions, sites in the planning pipeline and existing local plan allocations had been taken into account; thus, it considers ‘effective’ OAN (i.e. the numbers remaining to be allocated in the NDP) rather than the ‘pure’ OAN considered within the Lichfields study (Lichfields, Citation2018). This reflected the requirements at the time the NDP was being prepared rather than any final figure following changes through an emerging local plan process. As a result, this reflects the position communities were in when preparing their NDPs. Furthermore, the specific site allocations in the NDP were also analysed in order to determine whether they were ‘new’ allocations or were sites with existing planning permission or local plan allocations – these were derived from analysis of the local plan, cross-checked with data in the neighbourhood plan or via direct correspondence where necessary.

In a number of instances, the housing need for the neighbourhood area could not be ascertained – these included areas where an overarching housing number was provided for all NDPs (e.g. not area specific) and cases where the local plan was adopted in 2013/2014 and is silent on NDPs. Hence, assessment of whether the NDPs met the OAN was based on a smaller sample of 89 areas (as discussed below). This approach reflects aspects of the method adopted by both DCLG (Citation2015, Citation2016) with the inclusion of areas without an adopted local plan and Lichfields (Citation2018) in considering whether site allocations can be considered ‘new’.

The desk-based study was supplemented with a questionnaire to community members engaged in NP (n = 100) and LPAs supporting NP (n = 43). Nine case studies were also undertaken to deepen the understanding of local experiences towards NP. Case studies were populated by desk-based research and interviews with community members and local planning officers (in both planning policy and development management) (for further information see Parker et al., Citation2020).

Findings

This section reports the research findings across four topics: allocation of land for housing; wider development impacts; role of NDPs in decision-making; and impact of the wider planning system.

Allocation of land for housing

The findings suggest that the 141 NDPs which allocated sites sought to accommodate 24,741 dwellings across 480 sites. Of these, 18207 can be considered ‘new’ allocations, that is, those that are not allocated in a local plan or do not have planning permission. However, these numbers still need to be treated with caution as the site may otherwise have come through the local plan in any event (see Bailey, Citation2017). The average size of site allocations was for 51 units, which indicates NDPs are focusing on small to medium sites. However, not all NDPs specified the number of units to be delivered on the allocated sites, leading to further uncertainty. An average of four sites were allocated per eligible NDP ().

Table 1. Site allocations in neighbourhood plans.

Assessing whether these NDPs met the OAN was challenging. This could only be calculated for 89 areas. In the remaining NDPs (n = 52), the LPA provided a figure across a number of settlements based on their position in the settlement hierarchy or a district-wide OAN not broken down to neighbourhood level. Furthermore, only 19% of NDPs based their housing requirements on an adopted or examined local plan, with a high likelihood that the housing numbers would subsequently change (Lichfields, Citation2018). Of the NDPs provided with the OAN/housing number specifically for their neighbourhood, 23 plans (26%) allocated fewer than their requirement. However, on closer examination, 11 of these included a windfall allowance and a further two had ‘reserve sites’, meaning these can be considered to meet their OAN. This left 10 NDPs ‘under-delivering.’

In contrast, 38% of NDPs (n = 31) can be considered to have exceeded their OAN, delivering a total of 2,149 dwellings above their cumulative requirement. However, of these, 18 were examined in advance of an up-to-date local plan and this may therefore reflect an attempt by groups to future-proof their NDP against an emerging local plan.

Further analysis highlights that the situation in a particular LPA area can have a considerable impact and influence on the headline figures of NDPs. For instance, in many areas where the NDP was considered to be ‘under-delivering’, the NDPs were only slightly below the OAN (less than 10), with the shortfall easily addressed through a supportive approach to windfall. Many of these were also in areas with emerging local plans and it is possible that as the local plan emerged there were late adjustments to the OAN resulting in the NDP moving from meeting its requirement to underdelivering. In other areas, the OAN for the neighbourhood area is considered inflated due to the presence of a strategic (large) site allocation and indeed six NDPs accounted for 59% of the total dwellings above the OAN requirement.

Overall, the data suggests that NP’s contribution to housing supply through the allocation of sites can be significant. However, it also highlights the challenges in segregating the effects of NP from local planning policy, and the importance of considering the context within which the NDP was being prepared. The local plan context for each district at the time the NDPs were emerging is distinctive, as is the context for different types of NDP (for instance, rural NDPs with low OAN requirements versus NDPs in larger settlements where the OAN is higher and complicated by the relationship with strategic development sites). What emerges is a highly complex picture in which housing allocations are made, how many units are allocated, and the relationships between the numbers in NDPs and local plans. This means that any headline data needs to be interpreted carefully.

Wider development impacts

Two main reasons were provided by communities that did not allocate sites for development. First, the additional technical burdens associated with this process (reflecting findings in Parker et al., Citation2014), and second, concerns regarding potential community conflict and accusations of impropriety. Furthermore, the motivation for many to engage in NP is not necessarily to allocate sites for development but more broadly to ‘shape’ the development of their area. For example, 89% of respondents to the community questionnaire indicated that their NDP sought to improve quality of development – typically through design policies or a comprehensive design guide – and to tailor development to local needs (again reflecting earlier findings). Communities in the case study areas also discussed their involvement as a means to influence the type, location and relationship of new development to existing settlements, and to maintain or enhance local character and distinctiveness. They were motivated by previous experiences where development was considered to be ‘foisted’ on communities without having meaningful input, with the resultant development deemed to not respect local needs.

These broader place-based motivations are reflected in the type of housing-related policies included within the NDPs. All but two of the NDPs that allocated sites for housing established specific requirements for the site allocations. The most common type related to housing mix, followed by housing to meet local needs and the needs of older people ().

Table 2. Housing-related requirement of site allocation policies.

Furthermore, the NDPs also included an average of three policies that sought to address broader housing matters with a strong emphasis on promoting sustainable housing (e.g. green and renewable technologies), and influencing the character and design of new developments ().

Table 3. Housing policy in neighbourhood development plans.

The more stable or added value of NDPs may therefore lie in their broader place-making role with the inclusion of policies on local specificity, adding nuance and detail that is not possible at the local plan level, whilst providing the opportunity for communities to understand local housing needs

People can and do relate to planning at a neighbourhood level. Plan preparation brings communities together and transforms views to recognise the benefits of development of an appropriate type and quality in locations preferred by the community. (Community Q.55)

The study also found some evidence where development was considered more acceptable by communities by the inclusion of policies on design, affordable housing and meeting local needs. However, in as much as plan preparation can be influenced by the broader planning hierarchy, so can plan implementation. It is to this matter which we now turn.

Role of NDPs in decision-making

Responses to the LPA questionnaire suggest that site allocations were seen as a powerful tool in decision-making, particularly in terms of directing development to desired locations and steering it away from undesirable locations (with the allocation of sites in many, but not all, cases treated in decision-making to imply, ceteris paribus, a presumption against significant development outside of allocated sites), reducing speculative development pressure, and as a necessary condition for reducing the requirement for a five year supply of housing land to three years. Furthermore, LPA respondents remarked that sites allocated in NDPs may be more acceptable to the local communities, with 23.3% (n = 10) reporting that NDPs had reduced opposition to housing. However, 49% of LPA respondents (n = 21) did not see evidence of this. Overall, this was not regarded as a failing of the policy since new development is almost always contentious.

Eight LPA respondents reported a faster development process where site allocations were present in NDPs

… this has provided more certainty to developers and applications have been submitted with more confidence. (LPA Q.43)

The main advantage in this respect is that developers can understand issues that apply in that area and so tailor their proposals accordingly; this may then smooth the process for getting planning permission. (LPA Q.26)

This sentiment was also expressed by some communities

[There is …] empowerment through seeing the ‘bigger picture’ on new homes and being able to comment on and influence proposals has meant a community finally willing to accept and champion new home development. (Community Q.43)

I believe the community gained some basic knowledge about development and the role of the local authority and the role of the Parish Council. Even people who neighbour the nominated development sites have recognised the plan provisions (and policies to try to mitigate the effect of the nominated development on neighbours), so it has been accepted even by people who naturally would have voted against when it proposes a housing site next door. (Community Q.31)

However, in other areas, it was reported that NDP site allocations did not necessarily lead to a smoother decision-making process

In our recent Local Plan consultation events, we still see hostility to new housing development proposals in Neighbourhood Planning areas, and our Development Management colleagues still find many objections to new housing developments, even if they are the chosen site by the Neighbourhood Planning group. (LPA Q.17)

Furthermore, some LPAs identified that groups were engaging with NP with a view to restricting development

… [there can be] an upsurge in groups embarking on Neighbourhood Plans because they see applications from local landowners and developers (speculative or otherwise) coming forward in their parish and NDPs are perhaps still being perceived as a mechanism for subtly blocking further development or, as a minimum, are agreeing to accept the status-quo by only allocating sites which already benefit from some form of planning permission. (LPA Q.32)

We have concerns that many Neighbourhood Plans are introducing additional protectionist policies without a sufficiently positive strategy towards future housing development. Given the housing crises, it is a concern that significant officer time and resources are being directed towards Neighbourhood Plans that don’t necessarily bring forward the houses needed. (LPA Q.40)

A more positive attitude towards development was reported in areas that did not include site allocations or a housing target. For some, engagement in NP led to increased appreciation of how the planning system works, leading to less contention and more propensity to compromise. For instance, development management (DM) officers in one case study reported that objections were more policy driven and in another case study that communities were using NDPs as a basis to comment on planning applications, further adding value to the development management process. However, this was not a universal finding.

The findings also suggest that the broader strength of NDPs in decision-making is influenced by policy wording. Across the board, ‘robust’ NDP policies were considered to be of most use where they could add local specificity – detail that would not be possible at local plan level, for instance, local character assessments that underpinned design policies or guides. Local planning officers reported that this enabled them to use NDP policies to drive up the quality of development by refusing permission where the design specifications in the NDP were not met

The main considerations in decision-making on planning applications are set out in the Local Plan, rather than neighbourhood plans. Neighbourhood plans generally have most influence on the detail, for example design and character of new developments. (LPA Q.19)

It was reported that where NDP policies add value to local plan policies, they provide the DM officers with ‘an extra layer of confidence in certain areas and an ability to negotiate … a better, stronger case that we feel more confident with’ [Case Study 2]. They can also provide a greater degree of clarity to developers about what is acceptable for particular sites, perhaps going some way towards speeding up the decision-making process.

Unsurprisingly, where NDPs were considered to add little to local plan policies, lacked local specificity or were less clear, they were considered to have less impact in decision-making. For instance, one planning officer reported that the ‘majority of the plans do not have anything in them over and above what the development plan has, therefore they do not have that much impact’ [Case Study 7], while another remarked that there are ‘too many NDPs out there that aren’t that useful and haven’t achieved what communities would have hoped’ [Case Study 8].

Six LPA respondents also indicated that NP could slow down the development process by adding ‘additional policy complication’ (LPA Q.5)

… there is an additional set of policies for all parties to consider, along with the additional consideration of the weight to be given to each level of relevant policies in light of any differences in policy approach, inconsistencies and the different dates of adoption. (LPA Q.19)

It is important to remember that NDPs do not exist in isolation and their use in decision-making is part of a complex entanglement that includes relevant local plan policies and national policies. Four LPA respondents noted that NDPs are rarely ‘singularly determinative’, suggesting that the local plan is more influential

… relevant neighbourhood plan policies are rarely the main determining factor in the LPA decision and have generally repeated ones in the Local Plan, with a small amount of extra detail. (LPA Q.19)

Reference to neighbourhood plans has been made alongside the Local Plan in a couple of cases, but the neighbourhood plan has not been singularly determinative in the appeals in question, rather it has supplemented the reasons for refusal drawn largely from the Local Plan. (LPA Q.20)

The added value of NDPs can thus be in the detail, particularly where they ‘bolster’ decisions with local nuance – rather than significantly altering decision-making. Even where robust policies were in place, the effectiveness of NDPs was sometimes seen to result more from an ‘alignment of the stars’; being dependent on timing, and the willingness of communities and developers to engage, rather than the mere existence of NDP policies. This highlights the need for further research on the actual use of NDPs in decision-making and their role in the planning application process.

The effectiveness of neighbourhood planning as a policy tool may also be influenced by the response of the local planning authority and their attitude towards neighbourhood planning. Variations have been reported in the willingness of LPAs to respond to the agenda (Parker et al., Citation2014; Brownill, Citation2017; Salter, Citation2018, Citation2022) with LPAs enabling and shaping neighbourhood planning in different ways. This includes instances where the LPA may deliberately, or not, seek to frustrate neighbourhood plan progress (Parker et al., Citation2014) or ‘deflect’ communities from neighbourhood planning (Salter, Citation2018, Citation2022). In other areas, LPAs are displaying a ‘reactive’ approach and are not proactive in their offer of support whilst in others LPAs have embraced the opportunities provided by neighbourhood planning and are encouraging take-up in order to assist with delivery of the local plan (Salter, Citation2022).

Impact of the wider planning system

While the plan-led system requires that planning applications should ‘normally’ be determined in accordance with the relevant development plan (made up of the local plan and, where present, an NDP), in practice, a wider set of factors govern the weight that a decision-maker is likely to give to particular policies or whether the presumption in favour of sustainable development applies.Footnote2 In instances where the presumption does apply, this effectively reduces the weight that can be given to NDP policies by introducing a tilted balance in favour of applications. This can create frustrations with communities, as can the granting of permission for applications that conflict with emerging NDPs.

Throughout this process, the LPA retains the role of decision-maker at planning application stage. Several communities reported that their policies were not being interpreted in the way intended and some were concerned that their NDP had been overlooked or that higher tier policies were afforded more weight

The response of the LPA to policies in the NDP has been disappointing … the NDP has not been given enough weight. (Community Q.69)

… they are not worth the considerable time and expense either to the government or to the community. If no local plan is in place and no five-year housing land supply, they are basically meaningless. (Community Q.19)

There were also calls for more consistency and transparency in how decisions were made

Sometimes the planning officers accept our objection, sometimes not. This lack of consistency is difficult to understand. The NDP is part of the local plan and none of our policies conflict with that plan. Therefore, the fact that the [Parish Council’s] policy-based objections have been rejected on occasion, is a cause of some confusion and dismay. Better communication would undoubtedly help. (Community Q.6)

Our main issue is that planning officers should apply policies consistently and communicate openly when policies are either ignored or when proper weight is not given to the NDP. (Community Q.66)

The reliance of NDPs on these external conditions for their effectiveness may help to explain discrepancies between LPA and community perceptions of the effectiveness of NDPs: whilst the majority of DM officers believed that NDPs were effectively influencing decisions, many groups did not share this confidence. This reflects a broader frustration from communities that NP provides far more limited power than many had been led to believe by central government discourse (Wargent, Citation2021), with their role within the broader planning policy hierarchy subordinate to the influence of external factors

The NP process is a charade. It is not about identifying and improving local issues, it’s about agreeing with national policy. A waste of time, money and effort. (Community Q.81)

Permitted development rights are having a damaging effect on development and in particular are producing sub-standard development especially in change of use housing … You cannot produce a meaningful neighbourhood plan if it is constantly undermined. (Community Q.92)

Importantly, the different experiences of the practice of NP influences broader attitudes towards development. Resentment can be generated if what is delivered does not reflect the wishes of those engaged in NP, with groups feeling frustrated and even excluded from decision-making. Conversely, those who have had a positive experience of engaging with the planning system tended to display significantly more positive attitudes towards planning and development more broadly.

The key message from community respondents was the need to strengthen the influence of NP in decision-making so that its practice was more in line with governmental discourse

Respect and enforce Neighbourhood Plans; be very cautious about overriding them, especially when you seem to be doing so in the interests and at the behest of developers. (Community Q.30)

The development of [an NDP] takes a lot of hard work and dedication from communities. The process requires the final policies to be well thought through and supported by robust evidence … These efforts and outcomes should be respected and recognised. It is also important that developers and local authorities are not allowed to override/ignore the NDP policies when the plan is made. (Community Q.40)

The disparity between LPA and community perspectives highlights the need for better communication of how NDPs are considered in decisions. There is an important role for central government to share best practice and support LPAs in the development and implementation of NDP policies. In the words of one respondent, NP ‘is a long game, it’s not just about preparing a plan, it’s about what needs doing afterwards’ [Case Study 2].

Discussion and conclusion

The research illustrates the complexities involved in isolating the contribution of NDPs to overall housing supply, and the danger of attributing policy outcomes to one policy tool. The findings suggest that many communities have responded positively to the opportunity to allocate sites for development, and thereby attempt to contribute towards housing supply. In areas for which the OAN could be calculated, the vast majority were meeting or exceeding the numbers at the time of NDP preparation, through a combination of site allocations, reserve sites, and a ‘windfall’ allowance. However, only 19% of the NDPs based their housing requirements on an adopted or examined local plan, with a likelihood that the housing numbers would later change.

The timing of NDP preparation against timing of the local plan plays a significant part in decision-making, acting to shape the numbers achieved. In many areas, the OAN for the neighbourhood could not be ascertained as the LPA did not provide figures at this scale. This presented not only methodological challenges, but also reveals the difficulty for neighbourhoods to identify the housing need for which they should plan (Lichfields, Citation2018). In some instances, NDPs did not identify the number of dwellings to be delivered on their allocated sites, thus creating further uncertainty in terms of net or likely additionality.

The complexity of the neighbourhood plan – local plan relationship, and the considerable factors that influence decisions about whether or not to allocate sites in the NDP, and indeed whether a site is then actually developed out, results in a mixed picture in terms of net additionality. The study highlights challenges in attributing a particular quantum of housing to be delivered to a NDP and emphasises the importance of attention to policy implementation. It cannot be assumed that allocated sites will subsequently be developed and that housing completion is attributable in any significant way to a given NDP.

Indeed, the allocation of sites for development is not necessarily a motivation for many communities who saw their role as involving broader place-shaping. In that context, the research suggests that NDPs are able to contribute to an environment that is more responsive to local character and needs, whilst also driving up sustainability standards in terms of affordable housing, housing for elderly people, and renewable energy. In turn, there was incipient evidence that such responsiveness was resulting in a more positive approach towards development on behalf of some communities on those terms.

However, in as much as it is challenging to isolate the role of NDPs in net additional allocation or delivery of housing, it is insufficient to consider the inclusion of housing-related policies as an indicator of a more positive approach towards development per se.

Elsewhere it has been reported some that NDPs are reportedly seeking to promote anti-development sentiments (e.g. Parker & Salter, Citation2016; Brookfield, Citation2017) and may in other areas therefore act to reduce numbers of housing units delivered. This requires further study as this can only be verified after some time has elapsed and actual influence can be ascertained. Moreover, added value in policy terms is also questionable where NDPs alternatively double-up on existing local policies, rather than adding local specificity or value (Brookfield, Citation2017). Equally, a lack of clarity in wording of policy can lead to challenges in implementation anyway (Parker et al., Citation2015), reflecting the need to consider the suite of NDP policies holistically (Parker & Salter, Citation2016) and assess their contribution to decision-making as part of a skein of institutional interdependencies. This calls for longitudinal research to discover development effects over time and to include an assessment of whether sites allocated in NDPs are subsequently developed (or not), the influence of the wider suite of NDP policies (both housing and non-housing) on housing delivery and the role of neighbourhood plan examination in ensuring NDPs are positively prepared.

Overall, a mixed picture emerges when considering whether NP speeds up the planning process provides greater certainty for developers, or provides net housing allocation additionality. The virtuous circle conceptualised by DCLG (Stanier, Citation2014), perhaps unsurprisingly, does not translate neatly into reality and it does not incorporate or recognise the complexities of planning decisions and implementation. Crucially, NDPs need to be considered as part of a dynamic, complex and changing system (Parker et al., Citation2018), sitting within a broader framework. Reflecting their position in the planning policy hierarchy, many LPAs report that NDPs are effectively influencing decisions, but that they are not singularly determinative. Communities do not necessarily share this understanding, and the research highlights a need for greater awareness between groups relating to policy formulation, planning decision-making and the implementation of plan-led development.

Whilst we can be confident that NDPs can add net additionality to housing supply, the focus on the quantitative metrics is not an adequate measure of the impact of NP as a policy and should not be considered the benchmark of success for NPs (see Wargent & Parker, Citation2018), or a definitive basis to assume actual housing supply.

Moreover, such a focus obscures the wider benefits of community-led planning and turns attention away from the complexity of the planning policy hierarchy and the range of actors, institutions, and interests involved. The potential for community-led planning to result in more positive outcomes – reflecting community needs and delivering strategic objectives – could be supported by shifting the emphasis from their contribution towards housing supply to their broader place-shaping role (whilst still delivering development sensitive to local needs).

Alongside this, NP support needs to extend beyond the plan-making phase with increased help and information for groups on how to effectively engage in decision-making. The research illustrates that good quality NDPs stem from engaged communities – and often the best output of the process lies in having better engagement between communities and the LPA during the plan development phase and in the decision-making process. A focus on the production NDPs in and of themselves is highly limited. It is by focusing on attitudes to change and recognising the complex interdependencies of policy, while ensuring communities feel they are involved in decisions about development, that speed and certainty over development will more likely be achieved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) is a charge levied by local planning authorities on new development in their area. Those communities with a ‘made’ Neighbourhood Plan will receive 25% of the levy revenues; in Parished areas this is paid directly to the Parish and in non-Parished areas the local authority consults with the community over the spending of the CIL monies. This compares to 15% of revenues, capped at £100/dwelling, in areas without a ‘made’ NDP (DCLG, Citation2014).

2. Factors which influence whether the presumption in favour of sustainable development applies include.

a) Whether the local plan is up-to-date (and they can be found to be out-of-date for a wide range of reasons, including age since review, conformity with changing national policy, whether they plan to deliver (changing) nationally assessed housing need)

b) Whether the LPA can demonstrate a five-year supply of easily deliverable housing land, and if not, how large the shortfall is Local and Neighbourhood Plan policies on housing are considered out-of-date if the LPA cannot show a five-year supply of housing land

c) As of 2019, whether enough housing has been built in the LPA area to meet the Housing Delivery Test.

References

- Bailey, N. (2017) Housing at the neighbourhood level: A review of the initial approaches to neighbourhood development plans under the Localism Act 2011 in England, Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 10(1), pp. 1–14. doi:10.1080/17549175.2015.1112299.

- Barker, K. (2008) Planning policy, planning practice, and housing supply, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(1), pp. 34–49. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grn001.

- Berisha, E., Cotella, G., Janin Rivolin, U., & Solly, A. (2021) Spatial governance and planning systems in the public control of spatial development: A European typology, European Planning Studies, 29(1), pp. 181–200. doi:10.1080/09654313.2020.1726295.

- Boddy, M., & Hickman, H. (2018) Between a rock and a hard place”: Planning reform, localism and the role of the planning inspectorate in England, Planning Theory & Practice, 19(2), pp. 198–217. doi:10.1080/14649357.2018.1456083.

- Bogusz, B. (2018) Neighbourhood planning: National strategy for ‘bottom up’ governance, Journal of Property, Planning and Environmental Law, 10(1), pp. 56–68. doi:10.1108/JPPEL-01-2018-0001.

- Bradley, Q. (2015) The political identities of neighbourhood planning in England, Space and Polity, 19(2), pp. 97–109. doi:10.1080/13562576.2015.1046279.

- Bradley, Q. (2017) Neighbourhood planning and the impact of place identity on housing development in England, Planning Theory & Practice, 18(2), pp. 233–248. doi:10.1080/14649357.2017.1297478.

- Bradley, Q., & Sparling, W. (2017) The impact of neighbourhood planning and localism on house-building in England, Housing, Theory and Society, 34(1), pp. 106–118. doi:10.1080/14036096.2016.1197852.

- Brookfield, K. (2017) Getting involved in plan-making: Participation in neighbourhood planning in England, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(3), pp. 397–416. doi:10.1177/0263774X16664518.

- Brownill, S. (2017) Assembling neighbourhoods: Topologies of power and the reshaping of planning, In: S. Brownill & Q. Bradley (Eds) Localism and Neighbourhood Planning: Power to the People, pp. 145–162 (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Cleaver, F. (2017) Development Through Bricolage: Rethinking Institutions for Natural Resource Management (London: Routledge).

- DCLG. (2011) Localism Bill: Neighbourhood Plans and Community Right to Build. Impact Assessment (London: DCLG).

- DCLG. (2012) National Planning Policy Framework (London: DCLG).

- DCLG. (2014) National Planning Practice Guidance: What is the Neighbourhood Portion of the Levy? (London: DCLG).

- DCLG. (2015) Neighbourhood Planning: Progress on Housing Delivery, October (London: DCLG).

- DCLG. (2016) Neighbourhood Planning: Progress on Housing Delivery, October (London: DCLG).

- Doak, J., & Karadimitriou, N. (2007) (Re) development, complexity and networks: A framework for research, Urban Studies, 44(2), pp. 209–229. doi:10.1080/00420980601074953.

- Field, M., & Layard, A. (2017) Locating community-led housing within neighbourhood plans as a response to England’s housing needs, Public Money and Management, 37(2), pp. 105–112. doi:10.1080/09540962.2016.1266157.

- Gallent, N., Hamiduddin, I., & Madeddu, M. (2013) Localism, down-scaling and the strategic dilemmas confronting planning in England, The Town Planning Review, 84(5), pp. 563–582. doi:10.3828/tpr.2013.30.

- Harris, N., Webb, B., & Smith, R. (2018) The changing role of household projections: Exploring policy conflict and ambiguity in planning for housing, The Town Planning Review, 89(4), pp. 403–424. doi:10.3828/tpr.2018.24.

- Healey, P. (1992) An institutional model of the development process, Journal of Property Research, 9(1), pp. 33–44. doi:10.1080/09599919208724049.

- Inch, A. (2012) Creating ‘a generation of NIMBYs’? Interpreting the role of the state in managing the politics of urban development, Environment and Planning C: Government & Policy, 30(3), pp. 520–535. doi:10.1068/c11156.

- Inch, A., Dunning, R., While, A., Hickman, H., & Payne, S. (2020) The object is to change the heart and soul’: Financial incentives, planning and opposition to new housebuilding in England, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38(4), pp. 713–732. doi:10.1177/2399654420902149.

- Jackson, C., & Watkins, C. (2005) Planning policy and retail property markets: Measuring the dimensions of planning intervention, Urban Studies, 42(8), pp. 1453–1469. doi:10.1080/00420980500150896.

- Lees, E., & Shepherd, E. (2015) Incoherence and incompatibility in planning law, International Journal of Law in the Built Environment, 7(2), pp. 111–126. doi:10.1108/IJLBE-07-2014-0019.

- Letwin, O. (2008) Independent Review of Build Out. Final Report (London: DCLG).

- Lichfields. (2012) Neighbourhood Planning…the Story so Far (London: Lichfields).

- Lichfields. (2016a) Neighbourhood Plans in Theory, in Practice and in the Future (London: Lichfields).

- Lichfields. (2016b) Early Adopters and the Late Majority. A Review of Local Plan Progress and Housing Requirement (London: Lichfields).

- Lichfields. (2018) Local Choices? Housing Delivery Through Neighbourhood Plans (London: Lichfields).

- Locality. (2016) Neighbourhood Plans Roadmap Guide (London: Locality).

- Lord, A., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2014) Is planning “Under attack”? Chronicling the deregulation of urban and environmental planning in England, European Planning Studies, 22(2), pp. 345–361. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.741574.

- Lord, A., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2018) Getting the planners off our backs: Questioning the post-political nature of English planning policy, Planning Practice & Research, 33(3), pp. 229–243. doi:10.1080/02697459.2018.1480194.

- Ludwig, C., & Ludwig, G. (2014) Empty gestures? A review of the discourses of ‘localism’ from the practitioner’s perspective, Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 29(3), pp. 245–256. doi:10.1177/0269094214528774.

- Matthews, P., Bramley, G., & Hastings, A. (2015) Homo economicus in a Big Society: Understanding middle-class activism and NIMBYism towards new housing developments, Housing, Theory and Society, 32(1), pp. 54–72. doi:10.1080/14036096.2014.947173.

- MHCLG. (2020) Planning for the future. Planning White paper. London: MHCLG.

- NALC. (2018) Where Next for Neighbourhood Plans? Can They Withstand the External Pressures? (London: NALC).

- Parker, G. (2012) Neighbourhood planning: Precursors, lessons and prospects, Journal of Planning & Environment Law, 40, pp. 1–20.

- Parker, G., Lynn, T., & Wargent, M. (2014) User Experience of Neighbourhood Planning in England (London: Locality).

- Parker, G., Lynn, T., & Wargent, M. (2015) Sticking to the script? The co-production of neighbourhood planning in England, The Town Planning Review, 86(5), pp. 519–536. doi:10.3828/tpr.2015.31.

- Parker, G., Lynn, T., & Wargent, M. (2017) Contestation and conservatism in neighbourhood planning in England: Reconciling agonism and collaboration?, Planning Theory and Practice, 17(3), pp. 446–465. doi:10.1080/14649357.2017.1316514.

- Parker, G., & Salter, K. (2016) Five years of neighbourhood planning – a review of take-up and distribution, Town and County Planning, 85(5), pp. 175–182.

- Parker, G., & Salter, K. (2017) Taking stock of neighbourhood planning in England 2011–2016, Planning Practice and Research, 32(4), pp. 478–490. doi:10.1080/02697459.2017.1378983.

- Parker, G., Salter, K., & Hickman, H. (2016) Caution: Examinations in progress-the operation of neighbourhood plan examinations in England, Town and Country Planning, 85(12), pp. 516–522.

- Parker, G., Street, E., & Wargent, M. (2018) The rise of the private sector in fragmentary planning in England, Planning Theory and Practice, 19(5), pp. 734–750. doi:10.1080/14649357.2018.1532529.

- Parker, G., Street, E., & Wargent, M. (2019) Advocates, advisors and scrutineers: The technocracies of private sector planning in England, In: M. Raco & F. Savini (Eds) Planning and Knowledge, pp. 157–168 (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Parker, G., Wargent, M., Salter, K., Lynn, T., Dobson, M., & Yuille, A. (2020) Impact of Neighbourhood Planning in England (London: MHCLG).

- Pill, M. (2022) Neighbourhood collaboration in co-production: State-resourced responsiveness or state-retrenched responsibilisation?, Policy Studies, 43(5), pp. 984–1000. doi:10.1080/01442872.2021.1892052.

- Salter, K. (2018) Caught in the middle? The response of local planning authorities to neighbourhood planning in England, Town and Country Planning, 87(9), pp. 344–349.

- Salter, K. (2022) Emergent practices of localism: The role and response of local planning authorities to neighbourhood planning in England, The Town Planning Review, 93(1), pp. 37–59. doi:10.3828/tpr.2021.7.

- Sgueglia, A., & Webb, B. (2021) Residential land supply: Contested policy failure in declining land availability for housing, Planning Practice & Research, 36(4), pp. 371–388. doi:10.1080/02697459.2020.1867389.

- Slade, D., Gunn, S., & Schoneboom, A. (2019) Serving the Public Interest? The Reorganisation of UK Planning Services in an Era of Reluctant Outsourcing (London: RTPI).

- Smith, D. M., & Wistrich, E. (2016) Devolution and Localism in England (London: Routledge).

- Stanier, R. (2014) Local heroes: Neighbourhood planning in practice, Journal of Planning and Environment Law, 13(OP105), pp. 105–116.

- Sturzaker, J. (2011) Can community empowerment reduce opposition to housing? Evidence from rural England, Planning Practice and Research, 26(5), pp. 555–570. doi:10.1080/02697459.2011.626722.

- Tait, M., & Inch, A. (2016) Putting localism in place: Conservative images of the good community and the contradictions of planning reform in England, Planning Practice & Research, 31(2), pp. 174–194. doi:10.1080/02697459.2015.1104219.

- Turley Associates. (2014) Neighbourhood Planning. Plan and Deliver? (London: Turley).

- Vigar, G., Brookes, E., & Gunn, S. (2012) The innovative potential of neighbourhood plan-making, Town & Country Planning, 81(7/8), pp. 317–319.

- Wargent, M. (2021) Localism, governmentality and failing technologies: The case of neighbourhood planning in England, Territory, Politics, Governance, 9(4), pp. 571–591. doi:10.1080/21622671.2020.1737209.

- Wargent, M., & Parker, G. (2018) Re-imagining neighbourhood governance: The future of neighbourhood planning in England, The Town Planning Review, 89(4), pp. 379–402. doi:10.3828/tpr.2018.23.