Abstract

Background: Inpatient rehabilitation with patients who have sustained an acquired brain injury (ABI), including traumatic brain injury (TBI), focuses on improving performance in activities of daily living (ADLs). Although not studied to date in patients with ABI/TBI, Task Analysis (TA) integrates assessment and the prompting/cueing levels required to complete various tasks, with the goal to achieve effective skill acquisition and rehabilitation planning. TA has demonstrated efficacy in teaching life skills in individuals with developmental disabilities and in this study is applied to teaching ADL skills in ABI/TBI rehabilitation.

Primary objective: To validate the use of TA in measuring progress in teaching ADLs by comparing it with three common ADL measures: Functional Independence Measure, Barthel Index and Klein-Bell.

Methods: Twenty-four inpatients were administered the Functional Independence Measure (FIM), Barthel Index (BI) and the Klein-Bell ADL Scale (KB) TA within 72 hours of admission, at 4 weeks and within 72 hours of discharge, for showering and dressing tasks. A repeated measures ANOVA compared scores across the four measures, at three time points, for both tasks.

Conclusion: Concurrent validity of TA in measuring improvements in the ADL tasks was established. Improvements were associated with reductions in supervision and disability levels. TA was shown to be an effective evaluation and teaching strategy during rehabilitation, with demonstrated reductions in disability and supervision levels.

Introduction

As a significant cause of mortality and disability around the world, acquired brain injuries (ABI), including traumatic brain injury (TBI), affect over 500 000 individuals each year [Citation1]. The cognitive and behavioural deficits associated with ABI/TBI can affect many activities of daily living (ADLs) including dressing, showering, cooking, shopping and budgeting, etc., requiring retraining of basic independent living skills [Citation2–Citation5]. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment and treatment approach is required to promote a greater understanding of the underlying functional difficulties experienced by patients with ABI/TBI and to teach strategies that will improve functional independence and reduce care needs [Citation6].

Measuring the changes made in ADL performance is important for developing individualized treatment programmes and supervision requirements which can involve considerable resources for ongoing care and future treatment. Several assessment tools exist for evaluating ADL performance, including a variety of standardized measures, namely the Functional Independence Measure (FIM), Barthel Index (BI) and the Klein-Bell ADL Scale (KB) which have established reliability and validity [Citation7–Citation10]. The general purpose of these measures is to evaluate performance on a specific task and to track any changes over the course of treatment which can help in planning the amount of resources a patient may require upon discharge. Among the standardized ADL measures, FIM and BI are currently the most widely used in all areas of rehabilitation and they assess the degree of physical assistance an individual requires to perform an ADL task [Citation11–Citation13]. Alternatively, KB provides the total percentage of independence an individual demonstrates in completing six specific ADL tasks.

The application of task analysis (TA) to ADL tasks was done to incorporate the positive attributes of standardized measurement into an assessment and treatment protocol, using a methodology that would provide information regarding the level of cueing patients required during each step of any particular task so that instructional rehabilitation strategies could be developed. This methodology takes into account more of the behavioural and cognitive sequelae that often accompany patients with ABI/TBI. FIM, KB and BI use rating systems that heavily favour physical disabilities, which does not reflect the typical reason that individuals with ABI/TBI often show difficulties performing ADL tasks as their deficits tend to reflect cognitive and behavioural limitations [Citation7,Citation10,Citation13].

TA shares several similarities with FIM, KB and BI. Scores are weighted using methods similar to that of KB and BI. TA breaks down tasks into component steps like KB, as well as incorporates a functional grading scale similar to FIM. However, unique to the TA method is the ability to capture not only the physical impairments but detailed cognitive deficits, as well as to describe the level of prompting/assistance required to complete a specific step. This process requires intense observation, measurement construction or the systematic development and use of cueing levels, breaking down the task by components, as well as evaluating the individual while performing the particular task and how they are progressing throughout treatment [Citation14]. Task analysis has been used extensively with individuals who have developmental disabilities to teach a number of functional life skills including reading, cooking, adaptive behaviours, personal-care, as well as social skills [Citation15–Citation19]. The common process in applying task analysis (TA) to various activities is to break down a complex behaviour and then teach the component parts as a chain of responses. Therefore, TA is the process of breaking down any task into a sequence of manageable steps, then assessing the level of independence to perform each step, and finally to use the steps to train increased independent completion of the task [Citation15]. The levels of cueing or response prompts required to complete or train each step follow a behavioural prompting sequences from independent to physical guidance [Citation20].

TA is broken up into two phases. The first phase is the assessment phase, which emphasizes rational and empirical analyses in order to rigorously observe and categorize performance [Citation14]. In a dressing task the sequence of steps required for completion is broken down into its component steps and then the individual’s level of independence in completing each step is evaluated according to the cue or prompt required to complete the task. For example, the individual may be able to slip on their shoe independently and then require specific verbal cues for the step of tying up their shoe. The second phase is the validation phase, which emphasizes ‘hypothesis testing, group design and statistical evaluation to validate the model and relate process to outcome’ [Citation14]. These phases as used in this study are outlined in , which demonstrates how the task is broken down and how the cueing required to complete the task is quantified, which then becomes the basis for rehabilitation programming/teaching. Information on specific task components as well as types and levels of assistance required are necessary for clinical applicability of an assessment measure in ABI/TBI treatment [Citation8]. The rehabilitation team benefits from such information by allowing them to target intervention, track improvements and treatment efficiency, communicate patient’s functional status to family and team members and aid in development of discharge plans. Teaching patients compensatory strategies is a major part of the ABI/TBI rehabilitation process [Citation21].

Table I. Prompting descriptions for dressing Task Analysis and Composite Scores.

The purpose of the current study was 2-fold. First, to establish the concurrent validity of TA in measuring ADL tasks in a population of ABI/TBI inpatients, which has not been examined to date. This was achieved by comparing TA for showering and dressing with three other assessment tools with established validity (FIM, BI, KB). Task Analyses has been developed to assess over 24 ADL and IADL tasks, but, for the purpose of this study, only showering and dressing were used, because they are consistently performed by all inpatients. It was hypothesized that the TA methodology would show concurrent validity in the measurement of showering and dressing tasks consistent to that of FIM, BI and KB in an ABI/TBI inpatient population. The second purpose was to evaluate whether changes in showering and dressing skills would affect the level of disability and burden of supervision required by inpatient’s with ABI/TBI as this affects decisions related to resource planning upon discharge, given the significant utilization and cost issues related to this patient population [Citation22,Citation23]. The Supervision Rating Scale (SRS) and the Level of Disability Sub-scale from the Disability Rating Scale (DRS) were used to assess disability level and supervision requirements.

Material and methods

Subjects

Participants in the study were successively admitted inpatients to the Acquired Brain Injury Programme (ABIP) at the Regional Rehabilitation Centre, a part of Hamilton Health Sciences (HHS). Individuals are typically admitted to this programme either following completion of acute medical care or from the community. The programme has divisions that include a transitional living unit where patients who have sustained a moderate-to-severe head injury involving primarily cognitive deficits are admitted, with an average stay of 8–12 weeks. Another part of the programme includes a behavioural rehabilitation unit for patients who display primarily complex behavioural sequelae consequent to moderate and severe ABI/TBI. Both units use a trans-disciplinary model of care in which regulated health professionals delegate treatment in co-ordination with rehabilitation therapists trained to work with ABI/TBI patients. The inpatients that participated in this study had sufficient physical capacity to be assessed and taught showering and dressing skills. Consent was obtained from the patients or their substitute decision-maker. Only 2% of participants who were asked to participate in the study declined. Patients and/or their substitute decision-maker were informed of the study upon admission to the unit and were given the option to participate, while clarifying that their choice would not affect their treatment stay.

Twenty-four consecutively admitted patients to the inpatient rehabilitation programme and who provided consent or for whom consent was provided, participated in the study. Ethics approval for this study was obtained through The Research Ethics Board of HHSC and McMaster University. All research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Of the 24 participants in the study, 20 (83%) were from the transitional living unit and four (17%) were from the behavioural programme. The study group was comprised of a total of 17 males and seven females. The mean age of the sample was 40.71 years (SD = 15.43), with an average education of 12 years. Based on available Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) data (n = 12), the mean rating for the study group was 8. The majority of participants were single (48%), while the remaining were married (24%), divorced (12%), separated (8%) or in common-law relationships (4%). The type of injury ranged from Traumatic Brain Injury (44%), Cerebral Vascular Accident (CVA) (16%), Aneurysm (16%), Anoxia (8%), to Encephalitis (8%). Race was not accounted for in this study. The in-patients who participated in this study were primarily within the post-acute stages of recovery with the mean time from injury to participation being 14 months (SD = 5 months).

Measures

The Functional Independence Measure (FIM) is an evaluation tool indicating the assistance individuals require during the performance of various ADL tasks including self-care routines, sphincter management, transfers, locomotion, communication and social cognition [Citation13]. Patients are rated in each area ranging from 1 (total dependence) to 7 (total independence). The scores summed across domains to provide a total score which ranges from 18–126. Only scales related to showering and dressing were used from the FIM and total scores were adjusted accordingly.

The Barthel Index (BI) provides a measure of the assistance a patient requires during 10 ADL tasks: feeding, bathing, grooming, dressing, bowels, bladder, toilet use, transfers, mobility and stairs [Citation9]. Values of 0, 5 or 10 are assigned for each activity, where higher scores are associated with more independent task functioning and only scales related to bathing and dressing were used.

The Klein-Bell ADL Scale (KB) is a 170-item scale in which patients are provided with a percentage score indicating their level of independence on six ADL functions: dressing, elimination, mobility, bathing/hygiene, eating and emergency telephone communication [Citation9]. Lower scores indicate a higher degree of dependence in performing the task, while higher scores are associated with greater independence. Again, only scales related to dressing and bathing/hygiene were used.

The Task Analysis (TA) methodology is applied to well over 24 ADL and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) tasks, but, for the purpose of this study, only two were included; dressing and showering. TA involves a standardized process of breaking down each step of a task and then assigning the level of cueing required to complete each step. A score is assigned to each step and then summed to obtain a total score for the task [Citation24]. There are six levels of cueing with scoring ranging from 1–6 (). A score of 1 reflects the need for total physical assistance combined with specific verbal cueing, while a score of 6 indicates complete independence to complete the specific step of the task ().

Two independent measures were administered to patients to evaluate their level of supervision or care and their level of disability, which included The Supervision Rating Scale (SRS) and the Level of Disability Sub-scale from the Disability Rating Scale (DRS). These measures were used to evaluate whether changes in ADL performance were associated with relative changes in the burden of care and level of disability displayed by patients which would have a direct impact of resource utilization and planning. The SRS is completed by an independent rater to determine the level of supervision required by the patient [Citation25]. Higher SRS scores indicate full-time direct supervision, while lower scores signify no need for supervision resources [Citation25]. The Level of Disability Rating Scale provides a rating of the patient’s functional disability. A maximum score reflects an extreme vegetative state and minimum score reflects no functional disability [Citation26]. For the purpose of this study the relevant sub-scales, including cognitive ability for ‘grooming’, which reflects one’s level of disability in completing dressing tasks; as well as the ‘level of functioning’ scale, reflecting physical, mental, emotional and social level of disability were evaluated.

Procedure

Within 72 hours of admission, participants were administered the Supervision Rating Scale and parts of the Disability Rating Scale (Time 1), as well as administration of TA, FIM, BI and KB were completed which represented Time 1 data. The same staff completed the ADL measures (TA, FIM, BI and KB) at 4 weeks into admission (Time 2 data) and finally, within 72 hours of discharge (Time 3) at which the SRS and DRS were again administered (Time 2). Thus, the ADL measures (TA, FIM, BI and KB) were administered at three time points (admission, 4 weeks into admission and at discharge), while the supervision and disability ratings were obtained at two time points (admission and discharge).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained for each independent and dependent measure over the time points administered. Subsequently, correlations were investigated between FIM, BI, KB and TA, for both showering and dressing tasks. A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to evaluate performance scores on FIM, BI, KB and TA, separately, across the three time points for dressing and showering activities. T-tests were performed for the DRS and SRS scores between admission and discharge to assess change. All statistical analyses were conducted on SPSS (version 15).

Results

Means and standard deviations for all four measures were calculated at all three time points for ADL tasks (showering and dressing) and for the supervision and disability ratings separately, which are displayed in . Overall the results showed a consistent pattern of improvement on the four ADL measures over the course of rehabilitation, as well as a significant decrease in the requirement for supervision and disability over the course of rehabilitation. More specifically, there were concurrent decreases in SRS and DRS scores concomitant to increased scores on standardized ADL measures ().

Table II. Mean and standard deviations of scales across time.

Comparison of scores across ADL measures over time

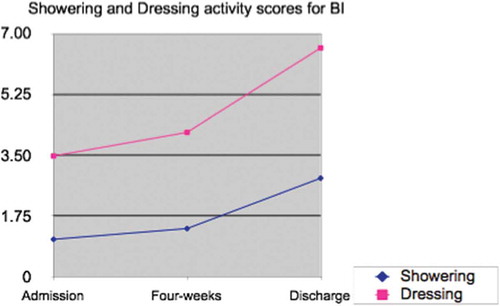

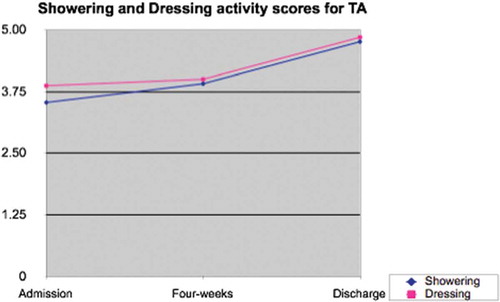

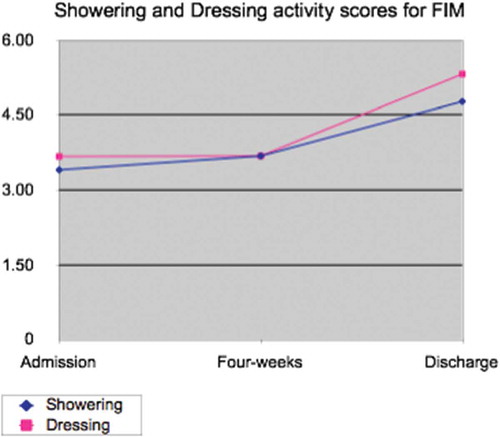

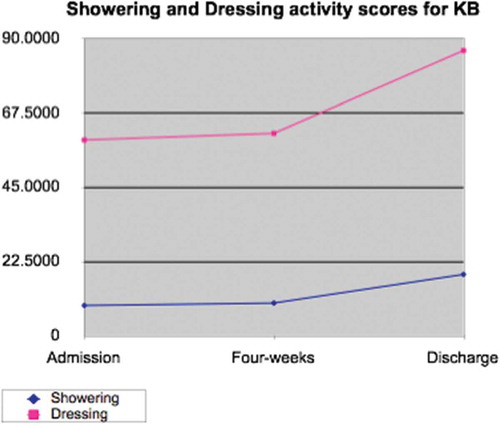

Repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to determine if there were mean differences between the four dependent measures (TA, FIM, BI and KB) between the time of admission, at 4 weeks into admission and at discharge for dressing and showering. For dressing activities, pair-wise comparisons among the four dependent measures revealed a main effect of time between admission and discharge (FIM: M dif = –1.67; BI: M dif = –3.67; KB: M dif = –29.47; TA: M dif = –1.16, p < 0.05), indicating that all patients scored higher, which indicates considerable improvement between admission and discharge (–) in the patients performance on measures of dressing. BI was the only measure that showed a significant mean difference between admission and 4-weeks (M dif = –2.00, p < 0.01), noting that substantial improvements were made between these two time points when using this measure. FIM and BI showed significant mean differences between 4-weeks and discharge (FIM: M dif = –1.07; BI: M dif = –1.67, p < 0.05). Overall, FIM, BI, KB and TA were all associated with statistically significant improvements in dressing scores between admission and discharge (–).

Figure 1. Dressing and showering scores for Functional Independence Measure at admission, 4-weeks and discharge.

Figure 3. Dressing and showering scores for Klein-Bell ADL Scale at admission, 4-weeks and discharge.

For showering, pair-wise comparisons revealed that scores on each of the four measures were considerably different between admission and 4 weeks (FIM: M dif = –0.89; BI: M dif = –0.71; KB: M dif = –4.57; TA: M dif = –0.82, p < 0.05) as well as between admission and discharge (FIM: M dif = –1.57; BI: M dif = –1.96; KB: M dif = –11.36; TA: M dif = –1.17, p > 0.05). Further analysis indicated that BI and KB scores were significantly different at 4-weeks and discharge (BI: M dif = –1.25; KB: M dif = –6.79, p < 0.05). Overall, statistically significant improvements were made in showering scores over the course of inpatient rehabilitation.

Ratings of supervision and disability

Results of paired sample t-tests for DRS and SRS scores at admission and discharge were found to be significantly different. SRS scores significantly decreased from the time of admission (M = 9.39, SD = 1.16) to discharge (M = 6.57, SD = 2.76; t* 5.39, p < 0.001), indicating that at discharge patients required less supervision. DRS level of functioning sub-scale scores also significantly decreased from the time of admission (M = 3.78, SD = 0.85) to the time of discharge (M = 3.00, SD = 0.92; t* = 4.16, p < 0.001), indicating improved level of functioning across physical, cognitive and emotional domains. Similarly, a significant decrease in DRS grooming scores was found between the time of admission (M = 1.02, SD = 0.90) and discharge (M = 0.83, SD = 1.21; t* = 2.70, p < 0.01).

Correlations between ADL performance and disability/supervision ratings

Scores from all measures were standardized and Pearson-Product correlations were conducted for both showering () and dressing () activities at admission and discharge.

Table III. Correlations among scales for showering (n = 24).

Table IV. Correlations among scales for dressing (n = 24).

From , it can be observed that the DRS and SRS scales had considerable positive correlations with each other. The correlations between the SRS and DRS with the four dependent measures were negative as the SRS and DRS have reversed scales from that of TA, FIM, BI and KB, indicating that improvements in ADL scores were associated with reductions in supervision and disability ratings. All correlations between FIM, BI, KB and TA were significant and positive; indicating that all measures showed similar patterns of scores, reflecting improvement over time.

Interestingly, the correlations between the four measures for showering and the SRS () remained significantly negatively correlated at admission and discharge other than for KB, which showed a non-significant negative relationship at discharge. For the DRS (LOF), significant negative correlations were found at admission for showering FIM, KB and TA and at discharge a similar directional relationship was found, but the correlations were not found to be significant. Therefore, reduction in the supervision level required by patients was more strongly associated with improvements in showering.

The correlations between the dependent measures for dressing and the DRS (cognitive grooming) showed consistently strong negative correlations with the dependent measures at admission and discharge, suggesting a strong sensitivity of this scale to functional improvements in dressing. Alternatively, the SRS showed significant negative correlations with the dependent measures at admission, but showed a decreased level of association with all standardized measures except TA. Overall, BI showed the least strength in association with SRS and DRS used, while FIM and TA showed the strongest and most consistent relationship with the SRS.

Discussion

Results from the current study confirm the hypotheses that the TA methodology provides ratings commensurate to that of standardized ADL measures with established reliability and validity (FIM, BI and KB) and that changes in these ADL activities show concomitant changes in the assessed level of disability and supervision required by the patient or measured burden of care. This means that TA is a sensitive measure of change in the ADL activities of showering and dressing, as demonstrated by the concurrent validity between TA and other ADL measures with established reliability and validity. Furthermore, improvements in showering and dressing are associated with consistent and significant reductions in the level of disability displayed by patients as well as their supervision requirements. In turn, lower levels of supervision were required given the reduction in the level of associated disability, which ultimately reduces treatment costs [Citation22].

The established sensitivity of the TA methodology to ADLs allows for its greater integrated use with patients who have sustained a ABI/TBI. This is of importance because other standardized measures of ADLs (FIM, BI and KB) are rarely used in this population as they do not provide critical information about the cognitive cueing requirements to complete various tasks. Thus, unstandardized observational data is the norm. However, by using TA as a standardized methodology to assess ADL activities, both physical and cognitive barriers to task completion can be quantified more accurately than with traditional measures such as FIM, BI and KB. The descriptive results obtained from TA facilitate rehabilitation planning (i.e. provisions for only general verbal cueing compared to physical assistance) for specific tasks. Thus, in the context of discharge and/or treatment planning, more appropriate resources can be determined balancing both physical and cognitive strategies. For example, a patient evaluated using FIM, who is identified as requiring assistance 50% of the time, frames the entire level of assistance required as physical. The same patient evaluated using the TA methodology would show the need for 50% specific verbal cueing and 25% gestural modelling to complete the same task. There are significantly fewer resources required to assist a patient with cueing and modelling with regards to number of therapists and hours, compared to physical guidance/assistance, than the FIM classification would provide. Therefore, by using the FIM with an ABI/TBI population, there is high risk of inappropriately resourcing the patient, which in the case of the aforementioned example would result in doing tasks for the patient instead of teaching the patient appropriate skills to manage the task more independently (i.e. providing physical assistance when only verbal cueing is required). The descriptors used in the TA provide for greater precision in rehabilitation resource planning as well as more appropriate treatment programming aimed at developing more appropriate treatment plans ().

The results of this study also demonstrated that significant improvements were made over the course of inpatient rehabilitation by patients with ABI/TBI as measured by reductions in their need for supervision and in their disability ratings. This decreased level of disability and need for supervision was consistent with the improvements patients showed on ADL tasks of showering and dressing. In a sample of patients with moderate-to-severe ABI/TBI involved in a multi-disciplinary inpatient rehabilitation programme, a significant decrease in the need for supervision and level of disability (related to physical, mental, emotional or social functioning) was found from the time of admission to discharge. This further demonstrates that improvements in showering and dressing were associated with the need for less supervision and a reduction in functional disability; thus, allowing for appropriate treatment and resource utilization planning.

The clinical utility of TA is important to patients with ABI/TBI. Previous research has indicated concerns with the use of commonly used standardized ADL measures among the ABI/TBI population, as the level of assistance and resources required are primarily rated based upon physically based impairments [Citation10], which means that patients would not receive appropriate treatment plans and resources because cognitive/behavioural barriers to task completion would not be addressed. The TA methodology was developed specifically to address the cognitive and behavioural requirements in teaching a task, and has greater utility in treatment and discharge planning with this population. This is critical as, with many patients who have ABI/TBI, it is the cognitive and behavioural sequelae that most often result in problems completing specific ADL tasks, and the level of assistance required to complete such tasks requires appropriate cueing strategies with some physical guidance rather than full physical assistance. Therefore, to develop appropriate treatment and resource utilization strategies, a measure is required that uniquely accounts for the cognitive/behavioural and physical impairments. The TA methodology applied to ADLs has the potential to provide a procedure that quantifies performance on a particular ADL task, and also to indicate the cognitive/behavioural strategy required to help the patient successfully complete the task. This helps to ensure greater consistency in the teaching approach used during rehabilitation, so that consistent and appropriate treatment is delivered which will maximize the potential for functional improvement. Thus, the current study is the first to apply TA to an ABI/TBI population and it was found that TA demonstrated concurrent validity in the assessment of ADLs such as showering and dressing with standardized ADL measures that have established reliability and validity. These changes are significantly correlated with concomitant functional changes in supervision and disability and, thus, reliable decisions can be made about treatment and discharge planning.

The TA methodology has been applied to other ADL and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) tasks in the ABI/TBI inpatient unit at Hamilton Health Sciences. It is currently being used to provide quantitative and qualitative information regarding task performance from which the training/rehabilitation steps are developed. This approach integrates an empirical evaluation with training which informs the rehabilitation assistance required to learn various ADL tasks. In the continuum of rehabilitation, using TA would facilitate resource planning so that rehabilitation can progress appropriately into the next environment (). Further research is required to validate the application of task analysis methodology to IADL tasks such as community safety, grocery shopping, budgeting, etc,, as there is a dearth of information regarding standardized procedures by which to assess these various activities. This study is the first known attempt to apply the TA methodology to ADL tasks in patients who have sustained ABI/TBI; where TA has been used extensively to teach a broad range of functional tasks within the population of individuals with developmental disabilities, as previously noted. Although only two ADL tasks were evaluated in the current study, future research should focus on the continued application of this methodology for assessment and teaching of a broad range of functional tasks in this population. Ongoing work will address the validity of measurement and efficacy of teaching additional ADL and IADL tasks.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Brain Injury Association of Canada. Putting the pieces together: Campaign for 2006 [Internet]. [cited 26 Mar 2006]. Available from http://biac.ronforeman.com/National/SponsorBrochure2006RevisedFeb16_2006.pdf

- Campbell M. Rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury: physical therapy practice in context. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

- Labi ML, Brentjens M, Coad ML, Flynn WJ, Zielezny M. Development of a longitudinal study of complications and functional outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 2003;17:265–278.

- Rasquin SM, Verhey FR, van Oostenbrugg RJ, Lousberg R, Lodder J. Demographic and CT scan features related to cognitive impairment in the first year after stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2004;75:1562–1567.

- O’Reily MF, Green G, Braunling- McMarrow, D. Self-administered written prompts to teach home accident prevention skills to adults with brain injuries. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 1990;23:431–446.

- Mateer CA, Sira CS, O’Connell ME. Putting Humpty Dumpty together again: the importance of integrating cognitive and emotional intervention. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 2005;20:62–75.

- Sangha H, Lipson D, Foley N, Salter K, Bhogal S, Pohani G, Teasell RW. A comparison of the Barthel Index and the Functional Independence Measure as outcome measures in stroke rehabilitation: patterns of disability scale usage in clinical trials. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2005;28:135–139.

- Settle C, Holm MB. Program planning: the clinical utility of three activities of daily living assessment tools. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 1993;47:911–918.

- Law M, Letts L. A critical review of scales of activities of daily living. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 1989;43:522–528.

- Shah S, Muncer SJ, Griffin J, Elliott L. The utility of the modified Barthel Index for Traumatic brain injury rehabilitation and prognosis. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy 2000;63:469–475.

- Hajek VE, Gagnon S, Ruderman JE. Cognitive and functional assessments of stroke patients: an analysis of their relation. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 1997;78:1331–1337.

- Eakin P. Assessment of activities of daily living: A critical review. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy 1989;52:11–15.

- Brock KA, Goldie PA, Greenwood KM. Evaluating the effectiveness of stroke rehabilitation: choosing a discriminative measure. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 2002;83:92–99.

- Greenberg LS. A guide to conducting task analysis of psychotherapeutic change. Psychotherapy Research 2007;17:15–30.

- Bancroft SL, Weiss JS, Libby ME, Ahearn WH. A comparison of procedural variations in teaching behaviour chains: manual guidance, trainer completion, and no completion of untrained steps. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis 2011;44:559–569.

- Mechling LC, Gast DL, Fields E. Evaluation of a portable DVD player as a self-promoting device to teach cooking tasks to young adults with moderate intellectual disabilities. The Journal of Special Education 2008;42:179–190.

- Matson JL, Taras ME, Sevin JA, Love SR, Fridley D. Teaching self-help skills to autistic and mentally retarded children. Research in Developmental Disabilities 1990;11:361–378.

- Stokes JV, Cameron MJ, Dorsey MF, Fleming E. Task analysis, correspondence training, and general case instruction for teaching personal hygiene skills. Behaviour Interventions 2004;19:1–15.

- Parker D, Kamps D. Effects of task analysis and self–monitoring for children with autism in multiple social settings. Focus on autism and other developmental disabilities. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 2011;26:131–142.

- Glendenning N, Adams GL, Sternberg L. Comparison of prompt sequences. American Journal of Mental Deficiency 1983;88:321–325.

- Bouwens SF, van Heugten CM, Verhey FR. The practical use of goal attainment scaling for people with acquired brain injury who receive cognitive rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation 2009;23:310–320.

- Dismuke CR, Walker RJ, Egede LE. Utilization and cost of health services in individuals with traumatic brain injury. Global Journal of Health Science 2015;7:156–169.

- Kreutzer JS, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Ripley D, Cifu DX, Rosenthal M, Bushnik T, Zafonte R, Englander J, High W. Charges and lengths of stay for acute and inpatient rehabilitation treatment of traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 2001;15:763–774.

- Yeun HK, D’Amico M. Deriving directions through procedural task analysis. Occupational Therapy Health Care 1998;11:17–25.

- Boake C. The Supervision Rating Scale. The Centre For Outcome Measurement in Brain Injury [Internet]. 2001 [cited 27 June 2008]. Available from http://tbims.org/combi/srs.

- Wright J. The disability rating scale. The Centre for Outcome Measurement in Brain Injury [Internet]. 2000 [cited 25 June 2008]. Available from http://www.tbims.org/combi/drs.