ABSTRACT

Primary objective

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a signature wound of recent Unites States military conflicts. The National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE) has demonstrated that interdisciplinary care is effective for active-duty military personnel with TBI and related psychological health conditions. This paper details how the Marcus Institute for Brain Health (MIBH), established in 2017 as an Integrated Practice Unit (IPU), is founded on the NICoE model and is dedicated to interdisciplinary care for Veterans with persistent symptoms due to TBI and psychological comorbidities.

Research design

A highly integrated group of clinicians from diverse disciplines combine their expertise to offer comprehensive evaluation, intensive outpatient treatment, and program outcomes evaluation.

Methods and procedures

The role of each discipline in the provision of care, and the regular interaction of all clinicians, are delineated. A strong connection to academic medicine is maintained so that clinical research and education complement patient care.

Main outcomes and results

Over three hundred veterans and family members have received treatment at the MIBH. Program evaluation is underway.

Conclusions

As the understanding of TBI and related psychological conditions continues its rapid evolution, the expert interdisciplinary care at the MIBH has great promise as a Veteran counterpart of the NICoE

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI), a major health problem around the world, has been termed a “signature wound” of recent military conflicts (Citation1). Between 2000 and 2019, over 413,000 United States service members were identified as having at least one service-related TBI, the vast majority of which (82%) were considered mild or mTBI (Citation2). These injuries can occur from the impact of a head striking a fixed object, an object striking the head with or without skull penetration, a whiplash effect injury, or a blast. Blast injury is unique in that, in addition to the primary damage caused by the force of the blast wave, there can be secondary (airborne debris) as well as tertiary (transposition of the body or structural collapse) injuries (Citation3). As there are currently no biomarkers that can reliably identify TBI, the diagnosis is founded on report or observation of the injury event. Specifically, the event must include at least one of the following: loss of consciousness of less than 30 minutes, post-traumatic amnesia of less than 24 hours, or an alteration of consciousness (Citation4). Common persistent post-concussion symptoms (PPCS) following mTBI include physical complaints (e.g., headache, dizziness, sleep disturbance, and fatigue); cognitive deficits (e.g., inattention, poor concentration, impaired memory, and executive dysfunction); and behavioral change(s) and/or alterations in degree of emotional responsivity (e.g., irritability, disinhibition, and emotional lability). These symptoms cannot be accounted for by a psychological reaction to physical or emotional stress alone (Citation5).

Recovery rates from mTBI are typically reported as 80–90% (Citation6), and the prescription for a positive recovery trajectory includes reduced stimulation (auditory and visual) and physical and mental rest with gradual return to life activities as symptoms subside (Citation7). However, mTBI in military populations is complicated by the fact that patients may not report the injury or seek treatment and, even if they do, treatment may not be available. Furthermore, there is often no opportunity for a full recovery period. In addition, it is quite common for Veterans of this era to have multiple mTBIs, sometimes in very close temporal proximity (Citation8). These types of injuries regularly occur during deployment, but a significant number also take place in training. In an attempt to address PPCS in these patients, a novel practice model, organized within the National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE), has demonstrated proof of the concept that interdisciplinary care is effective for active duty military personnel with TBI and related psychological health conditions (Citation9,Citation10). The success of the NICoE has suggested that a similar program might be feasible to serve the Veteran population.

Methods

Over the decade before 2017, an extensive series of discussions was held regarding the application of the NICoE model to the Veteran population. In parallel with these discussions, relevant literature was reviewed in preparation for the inauguration of a novel civilian TBI treatment program. As philanthropic funding was secured, the Marcus Institute for Brain Health (MIBH) took shape as a practice model that could be implemented to serve the needs of Veterans with mTBI whose symptoms persist for months or years after active duty. A strong affiliation with an academic medical center was a central consideration so that patient care could be complemented by clinical research and education to facilitate the discovery and dissemination of new information on the care of TBI and related health conditions.

A critical aspect of MIBH development was a detailed consideration of how the institute would interact with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which organizes the largest health care system in the United States and serves as the primary federally-supported source of health care for Veterans. Eligible Veterans have access to medical care for TBI and related psychological health conditions through VA clinics and hospitals, and many MIBH personnel were in fact being recruited because they had years of experience in the VA system and/or the military. However, some Veterans develop complex clinical issues after TBI that remain unresolved despite many encounters at the VA. From the earliest discussions, the MIBH expressed its commitment to supporting the value of the VA system while offering services as a force multiplier to address the exceptional clinical problems of selected TBI patients.

The MIBH was inaugurated in 2017 as an interdisciplinary evaluation and treatment program for Veterans and other adults who experience PPCS and related behavioral health problems. At the heart of this program are many clinical modalities, each uniquely contributing to the diagnostic evaluation, clinical understanding, and subsequent treatment of patients who present with a wide array of symptoms requiring a comprehensive approach. Patients who seek out the MIBH often express frustrations with the traditional medical model of individual outpatient clinic visits without a coordinated plan of care. Such a model is fraught with logistical, communication, and emotional challenges when there are many interwoven comorbidities in a high-risk population. The MIBH seeks to avert these frustrations by offering integrated treatment from multiple disciplines co-located in a comprehensive program.

The population served at MIBH consists primarily of post-9/11 United States combat Veterans. Whereas military service and deployment in any era are intense experiences, post-9/11 military service is unique in several ways. This era is the first in modern military history in which an all-volunteer military served multiple combat deployments with minimal dwell time in between (Citation11). The stress of military deployment (e.g., reduced privacy, poor sleep, lack of comfort, being away from family and friends) and combat (e.g., life threat, wartime killing, death of comrades) can result in depleted internal resources and increased allostatic load (Citation12). In such a context, service members are more vulnerable to both physical injury and psychological distress. Trauma of these types is dose dependent (Citation13,Citation14), such that repeated deployments result in increased risk of physical injury and stress reactions. Most MIBH patients have had multiple TBIs and all suffer with PPCS. In addition to the common features of PPCS such as headache, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and memory loss, many patients also experience balance and oculomotor deficits as well as auditory and communication dysfunction. A unique feature of recent post-9/11 military service is the high frequency of blast injuries, which are thought to result in prominent vestibular dysfunction (Citation15).

In addition to TBI, MIBH patients typically manifest one or more psychiatric comorbidities including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, panic, and substance use disorders. Following discharge from the military, many patients struggle with identity difficulties and the challenges of adapting to civilian and family life. Patients often experience grief regarding loss of status, respect, meaningful work, life structure, and the physical and emotional vigor of younger, healthier years. Advances in protective gear and medical technology have improved survival from injuries that would have previously been fatal (Citation16,Citation17), and polytrauma with chronic pain from physical injuries often exacerbates psychiatric dysfunction (Citation18,Citation19). Each of these psychosocial factors impact the potential for recovery, and all are considered in the clinical approach to each patient.

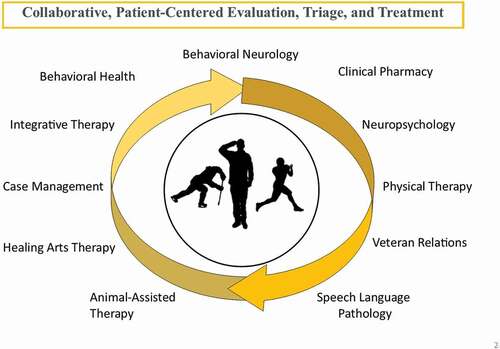

To optimally treat patients seeking help, the MIBH is founded on the concept of an Integrated Practice Unit (IPU) with a highly integrated and co-located team of providers (Citation20,Citation21). The MIBH interdisciplinary team consists of Behavioral Neurology, Physical Therapy, Neuropsychology, Speech-Language Pathology, Behavioral Health, Integrative Therapies, Art Therapy, Case Management Social Work, Clinical Pharmacy, Animal-Assisted Therapy, and Veteran Relations.

Results

The discussions informing the organization of the MIBH led to a broad consensus about the clinical model to be employed and the disciplines that would be represented. The NICoE served as a foundation for building this consensus, but it was also recognized that substantial differences between patient care in an active-duty setting and civilian life required that the MIBH incorporate distinctive features that would most directly address the needs of the Veteran population. A foundational aspect of planning was the understanding that knowledge of and sensitivity to military culture are crucial for effective treatment of Veterans adjusting to life after military service.

To address the question of treatment effectiveness for the complex problems related to TBI and co-morbid psychological conditions in this population, the MIBH adopted and implemented clinical outcome metrics similar to the NICoE which had been selected from the medical literature (see 3.3 Outcome Metrics). Outcome data collected from the time of application through two-year follow-up intervals are currently being analyzed.

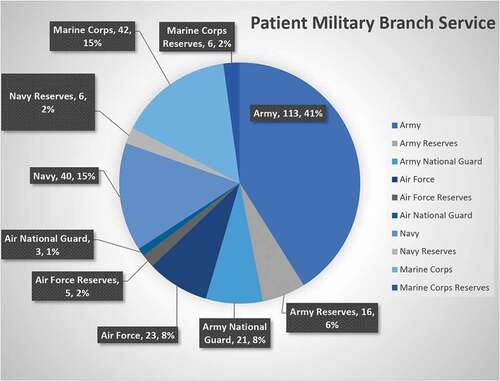

Preliminary data are available that will provide a foundation for the evaluation of clinical outcomes. As of March 2020, the MIBH had screened 599 applicants and conducted 235 comprehensive evaluations. Among those evaluated, most (82.8%) were Veterans and a high percentage (88%) were male. portrays the representation of the branches of military service among the Veterans seen at the MIBH. Over 27% were former members of the Special Forces and 47% were Colorado residents. The average age of all patients evaluated was 42 years (range 24–72). The majority had mTBI (86.4%) as measured by the Ohio State University Traumatic Brain Injury Identification Method (Citation22), and the majority (73.3%) reported multiple mTBIs. Patients with moderate (8.5%) and severe (5.1%) TBI were in the minority. Of those who completed the evaluation, 103 patients went on to complete the three-week treatment program.

Clinical model

In the IPU model, patients come to the MIBH for a three-day evaluation, beginning with an interdisciplinary meeting called the “Fishbowl,” during which patients can “tell their story” once to the entire clinical team. A provider from each discipline then conducts a one-on-one evaluation with the patient to gather information related to diagnosis and treatment planning. A core principle of the MIBH is that interdisciplinary communication is crucial to the success of an IPU. This kind of team interaction begins prior to the patient’s first contact during the evaluation phase to review the case history, during the Fishbowl, and again when the entire interdisciplinary team meets for a diagnostic case conference to share examination findings and treatment recommendations. Selected team members then meet with the patient to review and discuss this information.

After considering the team’s recommendations, many patients return for three weeks of treatment, designated as the Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP). During the IOP, patients are engaged in up to eight hours of treatment (individual and group) each weekday, and Equine Therapy on Saturdays. Interdisciplinary communication occurs daily, focusing on patients’ treatment process, progress, and barriers to improvement. These meetings occur either in 15-minute Huddles (three mornings per week) or one-hour Rounds (twice weekly). In addition, communication between team members takes place frequently and spontaneously in the co-located treatment setting. Family members participate in specific family programming during the last three days of the IOP (see section 3.2.12 Family Involvement below). At the conclusion of the IOP, all staff, patients, and involved family members are invited to participate in a commencement ceremony.

Disciplines

A wide array of expert practitioners is involved in the work of the MIBH. shows the various disciplines and how they interact with each other in collaborative, patient-centered evaluation and treatment.

Behavioral neurology

A key component of the evaluation week is a thorough neurobehavioral assessment conducted by a behavioral neurologist, or general neurologist with ready access to the subspecialist. Building on the patient’s history obtained from extensive medical record review and the information gathered from the fishbowl, this assessment begins with additional history-taking to clarify clinical data. Then follows a complete neurological examination, including detailed mental status testing. The clinical impression obtained from this evaluation is then considered together with the other assessments completed during the week, contributing to the final group decision about the suitability of the patient for the IOP. The role of behavioral neurology during the IOP involves regular medical contact with the patients as they receive treatment from all the MIBH professionals involved in interdisciplinary care. In addition, behavioral neurology expertise is available throughout the week for prompt consultation on any medical issue that may arise, including the supervision of any medical care that may be required, either within the MIBH or in the University of Colorado Health system at the Anschutz Medical Campus.

Physical therapy (PT)

Among the most often reported symptoms of PPCS in the MIBH patient population are dizziness, balance, and visual disturbances. In affected individuals, chronic impairments in postural control and related sensory integration and processing contribute to compromised responses to sensory input and reduced threshold for maintenance of physical and emotional stability (Citation23). Furthermore, the effects of TBI may include difficulties with efficiently reweighting sensory input (Citation24). For these reasons, vestibular PT is a central element of the evaluation and treatment of Veterans at the MIBH.

Physical Therapy evaluation includes a comprehensive physical examination focusing on the assessment of vestibular end organ function, vision, sensory organization, and postural control, and the evaluation of other primary physical functions (sensory integration, ocular motor control, vision-motion sensitivity). Other important considerations include secondary outcomes (such as fatigue, dizziness, headache, irritability), the potential for participation in treatment, and quality of life. Intervention consists of nine individual sessions across the three-week IOP. A multifaceted visual-vestibular rehabilitation approach is used, consisting of balance, ocular motor, and optokinetic training throughout the program, and each session is tailored to the individual.

Neuropsychology (NP)

The vast majority of patients seen at the MIBH have memory and attention complaints. The objective of the NP evaluation is to assess psychological functioning in addition to the fundamental cognitive domains that are routinely tested. Given the complex presentation of MIBH patients, it is clear that performance on NP assessment is influenced by multiple factors (e.g., sleep disorders, chronic pain, psychological distress, psychiatric symptoms, fatigue). These comorbid conditions add complexity to the interpretation of NP assessment, and in the context of an interdisciplinary evaluation, the detailed assessment of NP function provides unique added value. Conclusions are drawn, and shared with the patient, considering all relevant factors that can impact cognitive function. The feedback provided is in fact a form of intervention and education in itself and aims to help the patient better understand him/herself and demystify the reasons for cognitive and emotional distress.

Speech and language pathology (SLP)

At the MIBH, SLP focuses on evaluation and treatment of limitations in one or more critical social environments (e.g., home, work, school). Evaluation consists of record review, clinical interview, formal speech and language assessment, and hearing screening. The assessment aims to characterize the patient’s auditory functioning, cognitive communication, word-finding, and executive function, as these capacities pertain directly to the fulfillment of role expectations. Interventions include individual and group therapy modalities and are individualized to address each patient’s unique challenges. In keeping with the MIBH functioning as an IPU, SLP providers are aware of and can support patients who want to work on PT or other tasks in addition to SLP tactics during treatment. In turn, the information gathered by SLP can be used by the entire IPU team.

Behavioral health (BH)

Behavioral Health at the MIBH functions under five guiding principles: establishing a therapeutic relationship, providing symptom relief, building resilience, increasing self-efficacy, and restoring hope. Behavioral Health clinicians apply these principles in the context of the individual presentation, focusing on the most pressing and/or debilitating issues identified by the patient or significant other(s), and on patient-identified goals. Behavioral Health clinicians use both individual and group formats and choose from a variety of evidenced-based and evidence-informed therapies to achieve clinical goals with each patient. The complexity of patients’ presentations requires that clinicians remain flexible in their style, choice of treatment target for the day or week, and selection of treatment modalities on an individual patient basis. Operating within the IPU, BH has knowledge of each patient’s progress and struggles in other treatment modalities, allowing insights for other providers as to why a patient may be performing a certain way in his or her therapy setting. These interactions enhance the work the patient is doing in all modalities. For example, an insight developed in an individual BH session might be pursued by SLP providers in a group outing with Animal-Assisted Therapy. Alternatively, a pictorial discovery made in Art Therapy might provide a symbol that could be further explored in an individual psychotherapy session.

Integrative therapies (IT)

The term IT refers to healthcare interventions that promote optimal health and wellness using mental, physical, and spiritual approaches. From an IT perspective, it is important to distinguish between healing the person versus curing the disease, and to focus on the whole person using appropriate therapeutic approaches to promote healing. Integrative Therapies can include established complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) techniques such as yoga, acupuncture, guided imagery, mindfulness techniques, and tai chi. However, IT incorporates CAM techniques into a larger framework of treatment focused on bridging between mind, body, and spirit. In addition, each patient session includes a component of the awareness of internal states, mindfulness in the present moment, befriending and reconnecting with oneself, acceptance, compassion, and self-regulation. Integrative Therapy is conducted in both individual and group formats.

Art therapy (AT)

Art therapy is a psychotherapeutic intervention that addresses a broad spectrum of emotional and cognitive struggles Veterans may experience following TBI (Citation25). Creative arts therapies have been effectively incorporated into treatment for military services members with brain injury for many years (Citation26,Citation27). At the MIBH, AT is a component of both the evaluation and treatment program and is offered in individual and group settings. While some patients are initially skeptical about the usefulness of AT, they are reassured that the process of art making can be therapeutic even if skills and experience are lacking. Introducing the idea of a “flow state” (Citation28) helps the Veteran understand how the process of creative engagement and participation in the arts can be beneficial in enhancing self-regulation and improving mood. In addition, conceptualizing AT in the context of brain function and neuroplasticity can show that creativity is an important contributor to problem-solving, resiliency, and resourcefulness, affirming the relevance of AT to TBI recovery and rehabilitation (Citation29). In addition, insights gained in AT are often beneficial for other therapeutic disciplines involved as patients work toward their goals.

Case management social work

The role of Case Management (CM) at the MIBH has several facets. To begin, CM act as the point of contact for questions or support and has the responsibility of ensuring that Veterans are welcomed and familiarized with all that the MIBH program encompasses. Assistance offered to patients includes but is not limited to provision of general program orientation, explanation of campus logistics, and coordination of travel. As interactions with the patient expand, the CM team facilitates meetings such as Fishbowls, Rounds, and Debriefs. Finally, the CM team is responsible for aftercare planning with all Veterans who complete the IOP, a process that involves arranging appropriate follow-up for 12 months after completion of the program.

Veteran relations (VR)

Military and Veteran cultural training and sensitivity must be considered as patients transition to civilian healthcare. The VR personnel at the MIBH are military Veterans who provide essential support for both providers and patients to bridge this gap. VR is present at patient orientation, providing an initial touch point of a patient with another Veteran and a sense of camaraderie, familiarity, and understanding. This interaction also ensures that he or she is aware of VR role and its ability to assist with potential resource needs. A VR team member periodically meets individually with each patient to connect them with appropriate resources in their communities. VR personnel also host one afternoon outing (e.g., hiking, bowling) during the IOP to reinforce the cohesion of the cohort, offer a mental and physical break from the clinic setting, and, most importantly, have an enjoyable experience.

Clinical pharmacy (CP)

In the evaluation, CP has several objectives. These include an assessment of the safety and efficacy of all medications, an evaluation of potential substance abuse, and recommendations for mitigation strategies with respect to medications and substances that may interfere with the effectiveness of the IOP. Following a full medication history (with an emphasis on psychotropic medications and drugs that produced adverse reactions), any form of substance use (caffeine, nicotine, cannabis, alcohol, other) is explored to quantify dosing and frequency. Discussions also aim to understand the patient’s knowledge of medication effects and the interactions between medications and other substances used, whether the patient feels the medication(s) are effective, and why other substances are being used. In the IOP, the role of CP primarily focuses on ongoing substance use evaluation and long-term medication considerations.

Animal-assisted therapy

Warrior Canine Connection (WCC) is a nonprofit service dog organization that utilizes its Mission Based Trauma Recovery (MBTR) model as an adjunctive intervention to support Veterans and their families (Citation30). The MBTR model provides a safe, cost-effective, and non-pharmaceutical intervention that offers patients a sense of purpose and the opportunity to engage in a critical military support mission while simultaneously receiving treatment for their own symptoms of TBI, PTSD, and other conditions. Based on the time-honored tradition of Warriors helping Warriors, the patient’s mission is to help train highly skilled service dogs that provide years of mobility and social support to a fellow Veteran with a disability. Whereas one purpose of the WCC is to place Service Dogs, its primary role at the MIBH is to address the patient’s goals and function as an element of the IPU.

Family involvement

Family members play a critical role in the health and wellness of our Veteran patients. Typically, the spouse and children are most directly involved, but the MIBH also honors the important role of parents, siblings, and close friends. In the evaluation phase, a behavioral health provider makes a call to the support person of the veteran’s choice, most often a spouse. During this call, which usually lasts 45 to 60 minutes, information is gathered about strengths and weaknesses in the relationship, significant stressors, and relationships with children. The family member is also asked about major concerns with respect to specific behaviors and symptoms (e.g., self-harm, fatigue, nightmares, impaired sleep). As interdisciplinary evaluations proceed over the next two days, these data are instrumental in building an understanding of the complex issues with which patients may present. Family members are also involved in the three-week treatment phase. During the last week of the IOP, while loved ones continue with therapies, family members are invited to participate in family-only, group programming (e.g., TBI 101, Cognitive Communication, Mindfulness, Art Therapy, Behavioral Health) aimed at offering education and support. In addition, family members often join their loved ones for the final, wrap-up individual sessions with providers from each discipline. Finally, all family and friends are invited to participate in the commencement ceremony at the conclusion of the IOP.

Outcome metrics

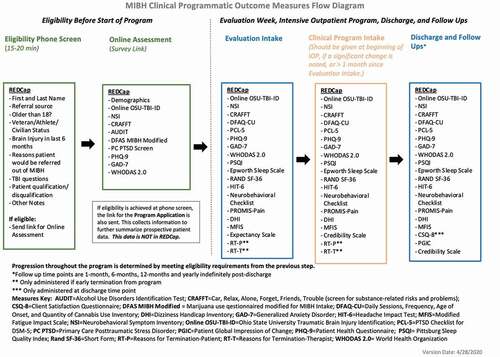

Consistent and accurate gathering of patient-specific data using valid and reliable measures is crucial in formulating treatment plans and assessing treatment efficacy. Outcome measures () are based on the collective experience of MIBH clinicians and a review of the relevant literature. The data collected help to determine the effectiveness of the program and contribute to larger data collection efforts for future needs. Prospective patients complete the first set of surveys before arriving at the MIBH. Surveys are administered again at the start of evaluation, at the beginning of the IOP, at the conclusion of the IOP, 1-month post-discharge, 6-months post-discharge, 1-year post discharge, and then yearly. Data collection and survey administration are both conducted using the HIPAA-compliant software REDCap, a data management tool that can be tailored to fit the needs of the population for which it is used. Surveys completed away from the MIBH (programmatic intake and follow-up) are delivered to a patient via e-mail hyperlinks that are connected to that patient’s REDCap record. Completion of surveys requires 20–45 minutes, and patients can take breaks as needed and return to their surveys without losing progress. While patients are engaged in the evaluation and IOP, surveys are completed on clinic computers with staff on hand to answer questions. Key clinical outcome metrics are extracted from REDCap at each time point and compiled into patient summaries for distribution to providers. Selection of outcome measures and construction of the REDCap database were completed before the first cohort of MIBH patients was seen, and only minor changes have been made to the database since then.

Discussion

The above description of the clinical model highlights the novel approach to the care of Veterans with TBI offered by the MIBH. Based on the success of the NICoE (Citation31), the MIBH has been inaugurated as a parallel civilian program that uses the interdisciplinary IPU model to provide state-of-the-art care to military Veterans after the time of their service. Whereas clinical experience at the MIBH has just begun to analyze clinical outcomes in a formal manner, patient evaluations have been overwhelmingly positive, suggesting that the NICoE model can be implemented to serve Veterans in a civilian setting.

There are important limitations to this report that deserve mention. First, an obvious limitation is the lack of a control group with which the outcomes of MIBH patients can be compared. The intent of this paper is to describe the IPU model used by the MIBH, and outcome data are not yet available to compare with data from a control group. As more patients are seen and outcome data become available, a suitable control group – using, as possible sources, wait list controls or similar Veterans with brain injury who chose not to participate – will be considered. Second, a more general limitation is that the MIBH model is not readily applicable to other settings because of its high costs. Whereas the MIBH financial structure vigorously pursues all reasonable billing from third-party payors, these sources of revenue cannot be expected to sustain the kind of clinical program offered by the MIBH in the current United States health care system. In short, this treatment model would not be possible were it not for the generosity of philanthropic benefactors who support its mission. Nevertheless, the dissemination of the MIBH model is justified as an effort to demonstrate the value of an IPU approach that may be applicable in other medical settings in the event that funding priorities change in the future.

The MIBH closely resembles the NICoE regarding clinical programming as outcome data from the NICoE clearly demonstrated the importance of the interdisciplinary model (Citation9,Citation31). Major differences between the NICoE and the MIBH, however, are the source and extent of funding. The MIBH was established by a philanthropic gift over five years that was the same as one year of NICoE funding from the DoD. As it was immediately apparent that medical billing and reimbursement would be insufficient to fund the MIBH without philanthropic support, an important lesson learned was that financial sustainability would be an ongoing consideration. In particular, CAM treatments (yoga, meditation, mindfulness) are generally non-reimbursable by third-party payors, despite evidence that they are essential components of treatment. Another important difference between the NICoE and the MIBH is that the goal of NICoE treatment is return to military duty whereas those who complete the MIBH program return to society. It is unfortunate that traditional medical billing cannot sustain a model of care such as the MIBH, as it is quite possible that such care will ultimately reduce future health care costs and result in more productive members of society over many years of healthy living. In comparison to the initial cost of treatment, these downstream outcomes may have significant financial implications. Future research is thus warranted to examine whether the high cost of MIBH care actually saves health care and other societal expenditures in the long run.

The MIBH has been successfully established and shows promise as a Veteran counterpart of the NICoE. The interdisciplinary IPU model can be transferred to civilian practice and serve Veterans whose post-TBI dysfunction can persist for years after military service. Studies now underway will serve to assess the efficacy of MIBH care, using the NICoE data recently published as a benchmark (Citation31). Additional studies using advanced neuroimaging will aim to assess the neurobiological correlates of TBI so that interventions can be guided by knowledge of how the brain responds to treatment. A vital aspect of the MIBH is its strong association with academic medicine, which will facilitate the gathering and dissemination of new information on TBI evaluation and treatment. As the understanding of TBI and related psychological disorders continues its rapid evolution, the MIBH stands well poised to serve the needs of Veterans with complex post-TBI disorders best served by expert interdisciplinary care. Finally, in keeping with the goals of philanthropic support that were clear as the MIBH was being envisioned, the expansion of TBI expertise to other sites around the country is a high priority. As the MIBH matures with the expansion of patient evaluation and care, a core objective is to export its knowledge to network partners that can both expand access to expert TBI care and contribute to large-scale TBI studies that are only possible when many institutions collaborate. In a still larger context, the MIBH model may prove relevant in other areas of medicine, as it is likely that an interdisciplinary IPU model will find application in many settings devoted to complex clinical disorders that require an integrated approach for effective care.

Acknowledgments

The Marcus Institute for Brain Health is a component of the University of Colorado which received generous funding from the Marcus Foundation to provide clinical care for US military Veterans and to disseminate lessons learned to network partners across the country. The authors are employees of the University of Colorado, a public institution of higher education.

Disclosure statement

Traumatic brain injury has been called the “signature wound” of recent military conflicts. Soldiers who sustain an injury of this kind, particularly if repeated many times, can often be obliged to endure a variety of debilitating symptoms that may persist for years after military service. The treatment of persistent post-concussive symptoms is often unsuccessful despite the well-intentioned efforts of the health care system to address the many challenging problems that can follow concussion. In recognition of the need for an integrated approach to this problem, the National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE) was successfully established to address the needs of active-duty military personnel. In this report, a civilian counterpart of the NICoE – the Marcus Institute for Brain Health (MIBH) – is described to highlight the feasibility of caring for traumatic brain injury in Veterans who have completed military service but experience lasting symptoms. A foundational aspect of both the NICoE and the MIBH is the concept of an interdisciplinary Integrated Practice Unit, by which is meant the work of many dedicated professionals who collaborate at a single location to address the myriad of problems Veterans can experience after TBI.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brundage JF, Taubman SB, Hunt DJ, Clark LL. Whither the “signature wounds of the war” after the war: estimates of incidence rates and proportions of TBI and PTSD diagnoses attributable to background risk, enhanced ascertainment, and active war zone service, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2003-2014. MSMR (US Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine, Executive Communications Division). 2015;22( 2):2–11.

- Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. DoD TBI worldwide numbers. 2020. Accessed March 19, 2021. https://dvbic.dcoe.mil/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi.

- Przekwas A, Garimella HT, Tan XG, Chen ZJ, Miao Y, Harrand V, Kraft RH, Gupta RK. 2019. Biomechanics of blast TBI with time-resolved consecutive primary, secondary, and tertiary loads. Mil Med. 184(Supplement_1): 195–205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy344

- Malec JF, Brown AW, Leibson CL, Flaada JT, Mandrekar JN, Diehl NN, Perkins PK. 2007. The Mayo classification system for traumatic brain injury severity. J Neurotrauma. 24(9): 1417–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2006.0245

- Arciniegas DB, Anderson CA, Topkoff J, McAllister TW. Mild traumatic brain injury: a neuropsychiatric approach to diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2005;1(4): 311.

- Katz DI, Cohen SI, Alexander MP. Mild traumatic brain injury. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2015;127: 131–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-52892-6.00009-X

- Silverberg ND, Iaccarino MA, Panenka WJ, Iverson GL, McCulloch KL, Dams-O’Connor K, Reed N, McCrea M, Cogan AM, Park Graf MJ, et al. 2020. Management of concussion and mild traumatic brain injury: a synthesis of practice guidelines. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 101(2): 382–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2019.10.179

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Associations between repeated deployments to OEF/OIF/OND, October 2001-December 2010, and post-deployment illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces. MSMR (US army center for health promotion and preventive medicine, executive communications division). 2011 Jul;18( 7):2–11. eng. Epub 2011/ 08/06. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 21815709.

- DeGraba T, Grammar G, Williams K, Kelly J. Efficacy of an interdisciplinary intensive outpatient program in treating combat-related TBI and psychological health conditions. Ann Neurol. 2016;16;S920(80): S235–S236.doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(75)90016-7.

- Ayer L, Farris C, Farmer CM, Geyer L, Barnes-Proby D, Ryan GW, Skrabala L, Scharf DM. Care transitions to and from the national intrepid center of excellence (NICoE) for service members with traumatic brain injury. Santa Monica, (CA): RAND Corporation; 2015. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR653.html

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Associations between repeated deployments to Iraq (OIF/OND) and Afghanistan (OEF) and post-deployment illnesses and injuries, Active Component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2003–2010. 2011. 2-11. 18. (Medical Surveillance Monthly Report).

- Bay E, Donders J. 2008. Risk factors for depressive symptoms after mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 22(3): 233–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050801953073

- Interian A, Kline A, Janal M, Glynn S, Losonczy M. 2014. Multiple deployments and combat trauma: do homefront stressors increase the risk for posttraumatic stress symptoms? J Trauma Stress. 27(1): 90–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21885

- Varga CM, Haibach MA, Rowan AB, Haibach JP. 2018. Psychiatric history, deployments, and potential impacts of mental health care in a combat theater. Mil Med. 183(1–2): e77–e82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usx012

- Akin FW, Murnane OD, Hall CD, Riska KM. 2017. Vestibular consequences of mild traumatic brain injury and blast exposure: a review. Brain Inj. 31(9): 1188–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2017.1288928

- Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, Adamson DM, Metscher KN. Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries. In: Tanielian T, and Jaycox LH, editors. Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation; 2008. p. 3–18.

- Fisher H. A guide to U.S. Military causality statistics: operation freedom’s sentinel, operation inherent resolve, operation new dawn, operation iraqi freedom, & operation enduring freedom. Congressional Research Service; 2015 March 19, 2021. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS22452.pdf.

- Sayer NA, Rettmann NA, Carlson KF, Bernardy N, Sigford BJ, Hamblen JL, Friedman MJ. Veterans with history of mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder: challenges from provider perspective. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(6): 703–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2009.01.0008. Epub 2010/ 01/28. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 20104400.

- Waszak DL, Holmes AM. The unique health needs of post-9/11 U.S. Veterans. Workplace Health Saf. 2017 Sep;65(9): 430–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079916682524. Epub 2017/ 08/30. doi:. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 28849739.

- Williams DV, Liu TC, Zywiel MG, Hoff MK, Ward L, Bozic KJ, Koenig KM. Impact of an integrated practice unit on the value of musculoskeletal care for uninsured and underinsured patients. Healthcare. 2019 Jun 7;7(2): 16–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2018.10.001. Epub 2018/ 11/06. doi:. Cited in: Pubmed; PMID 30391168.

- Porter KE, Lee TH. The strategy that will fix health care. Harv Bus Rev. 2013;91(10): 50–70.

- Lequerica AH, Lucca C, Chiaravalloti ND, Ward I, Corrigan JD. 2018. Feasibility and preliminary validation of an online version of the Ohio State University traumatic brain injury identification method. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 99(9): 1811–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.03.023

- Hebert JR, Forster JE, Stearns-Yoder KA, Penzenik ME, Brenner LA. Persistent symptoms and objectively measured balance performance among OEF/OIF veterans with remote mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018; 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/htr.0000000000000385.

- Slobounov S, Tutwiler R, Sebastianelli W, Slobounov E. 2006. Alteration of postural responses to visual field motion in mild traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery. 59(1): 134–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000243292.38695.2d

- Jones JP, Walker MS, Drass JM, Kaimal G. 2018. Art therapy interventions for active duty military service members with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. Int J Art Ther. 23(2): 70–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1388263

- Howie P. Therapy with military populations: history, innovation, and applications. Taylor and Francis: New York New York; 2017.

- King JL. Art therapy, trauma, and neuroscience. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow. New York: Harper Collins, 1990.

- Hass-Cohen N, Carr R. Art therapy and clinical neuroscience. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2008.

- Yount R, Ritchie EC, St. Laurent M, Chumley P, Olmert MD. 2013. The role of service dog training in the treatment of combat-related PTSD. Psychiatr Ann. 43(6): 292–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20130605-11

- Degraba TJ, Williams K, Koffman R, Bell JL, Pettit W, Kelly JP, Dittmer TA, Nussbaum G, Grammer G, Bleiberg J, et al. Efficacy of an interdisciplinary intensive outpatient program in treating combat-related traumatic brain injury and psychological health conditions. Front Neurol. 2021;11. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.580182.