ABSTRACT

Research on second language learning by children with DLD has mainly focused on naturalistic L2 acquisition with plenty of exposure. Very little is known about how children with DLD learn foreign languages in classroom settings with limited input. This study addresses this gap and targets English as a foreign language (EFL) learning by Russian-speaking children with DLD. We ask whether learners with DLD benefit from a later onset of EFL instruction because older children are more cognitively mature and have more developed L1 skills. The second aim of this study is to determine whether EFL learners with DLD benefit from positive L1 transfer in vocabulary learning. We administered a receptive vocabulary test to younger (Grade 6, n = 18) and older (Grade 10, n = 15) children with DLD matched on the amount of prior EFL instruction. The younger group started EFL instruction in Grade 2 and the older group in Grade 6. The performance of the two groups was compared after four and a half years of English lessons. Half of the words in the test were English-Russian cognates and half were noncognates. Contra to our hypothesis, the results showed no difference between younger and older children. Both groups equally benefitted from cognate vocabulary suggesting that positive cross-language transfer is available to children with DLD, irrespective of their age and onset of EFL instruction.

Introduction

The ability to speak at least one foreign language is considered to be a crucial skill that children need to acquire. Traditionally, children with learning disabilities, and particularly learners with developmental language disorder (DLD), were less likely to participate in foreign language (FL) classes and to receive out-of-school exposure to FLs because they already have a lot of difficulty acquiring their mother tongue and a new language might become an additional burden on their shoulders (Arnett et al., Citation2014; Marinova-Todd et al., Citation2016). At the same time, there is a growing awareness that insufficient FL knowledge, especially knowledge of English as a foreign language (EFL), will place students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage for academic careers and employment (Scherba de Valenzuela et al., Citation2016). Following the world-wide tendency towards an early start of EFL instruction, many children with DLD now start EFL lessons already in primary school, even though very little is known about how children with DLD learn FLs and how they can be supported in doing so.

The ample research on second language (L2) acquisition by children with DLD has focussed almost exclusively on language development in naturalistic settings with plenty of exposure (e.g. learning English in the US). Research along these lines generally shows that children with DLD can become bilingual if they acquire the target language in the country where it is spoken (Genesee, & Fortune, Citation2014; Genesee, & Lindholm-Leary, Citation2013; Paradis, Citation2016) or in immersion programmes (Bruck, Citation1982). It remains to be seen whether the findings obtained in naturalistic and immersive settings can be generalised to FL instruction in a classroom with minimal exposure to the target language (30–90 minutes a week).

Henceforth, we use the term L2 to refer to naturalistic second language acquisition with plenty of exposure, whereas the term (E)FL is used with reference to language learning in instructed settings with limited classroom exposure. The distinction between L2 acquisition and FL learning is particularly relevant in the context of DLD because children with DLD need more exposure to the target language (and hence more time) in order to acquire the same language phenomena that children with typical language development (TLD) acquire with less input (Evans et al., Citation2009). Since FL exposure in school settings is extremely limited, it is plausible to ask whether such reduced input in the classroom is sufficient for input to become intake. Put differently, it is not clear whether children with DLD can learn anything at all if their exposure to a FL is confined to input provided in the classroom.

This paper focuses on the performance of Russian-speaking EFL learners with DLD on English vocabulary. Children who participated in this research grow up in Siberia, with very little informal exposure to English outside of the classroom. All media in Russia are dubbed rather than subtitled and contact with languages other than Russian is largely limited to English songs and computer games. This setting gives us an opportunity to explore the effects of formal EFL instruction in a fairly pure instructed setting. The present study aims to determine whether EFL vocabulary knowledge can be predicted by starting age of EFL instruction and by cross-linguistic similarities between words in the first language (L1) and in the FL.

Foreign language learning by children with DLD

To the best of our knowledge, only two prior studies have targeted FL learning by children with DLD (Tribushinina et al., Citation2020; Zoutenbier & Zwitserlood, Citation2019). Zoutenbier and Zwitserlood (Citation2019) measured EFL proficiency in primary-school children with DLD in the Netherlands, where English became a mandatory subject in special education primary schools in 2012. The results demonstrated that children with DLD perform below age norms on the four basic EFL skills, even though Dutch children usually get plenty of exposure to English outside of the classroom.

Tribushinina et al. (Citation2020) traced the development of EFL skills in a group of Russian-speaking children with DLD and a comparison group of children with TLD. After one year of English lessons there were no significant differences between children with and without DLD on English receptive vocabulary and grammar. However, children with TLD showed significant improvement in both vocabulary and grammar after 1.5 and 2 years of English lessons, whereas this was not the case for the DLD group. These results demonstrate that EFL learners with DLD can make progress in both vocabulary and grammar (as evidenced by their performance after one year of EFL instruction), but very slowly. Another noteworthy finding was that older children with DLD had an advantage over their younger peers in the acquisition of EFL vocabulary. This result is consistent with the literature on FL learning by children with TLD demonstrating that children who start English lessons later attain the same proficiency level as early starters despite a shorter length of instruction (Goriot, Citation2019; Jaekel et al., Citation2017; Larson-Hall, Citation2008; Muñoz, Citation2006, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Pfenninger, Citation2014, Citation2017; Pfenninger & Singleton, Citation2016). Hence, the ultimate attainment advantage of younger L2 learners attested in naturalistic L2 acquisition (Genesee & Lindholm-Leary, Citation2013; Krashen et al., Citation1979) disappears in instructed FL learning with limited classroom exposure. Older children have a learning rate advantage because age is positively associated with cognitive maturity, but also because older children have a more developed L1 and benefit more from positive cross-language transfer (Muñoz, Citation2006).

The present study will contribute to the literature on age effects in FL learning by comparing EFL vocabulary levels in learners who started EFL lessons at different ages. We further focus on one specific capacity that has been shown to underlie the learning rate advantage of older learners: the ability to use L1 knowledge in learning a new language. For example, if a child already knows the word аэропорт/aeroportFootnote1 in Russian, they will find it easier to learn the English counterpart airport. The advantage of cross-linguistic similarity interacts with age because older children know more words in the L1, but also have more developed metalinguistic skills that allow them to notice patterns in cross-linguistic similarities (Bosma et al., Citation2019, Citation2022; Kelley & Kohnert, Citation2012).

Cross-linguistic transfer in DLD

Even though there is plenty of evidence that EFL learners with TLD benefit from positive L1 transfer (e.g. Mulder et al., Citation2019; Siu & Ho, Citation2015; Sparks et al., Citation2008), relatively little is known about cross-language transfer in DLD and the available results are controversial. Some studies suggest that L2 learners with DLD rely on their knowledge of typologically similar L1s, particularly in the domain of vocabulary (Grasso et al., Citation2018; Kambanaros et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Blom and Paradis (Citation2013) report that L2 English learners who have already acquired verb morphology in their inflectional L1 (e.g. Spanish) have an advantage over L1 speakers of isolating languages (e.g. Mandarin) in the acquisition of L2 English verb inflections, and this advantage equally holds for L2 learners with TLD and DLD (Blom & Paradis, Citation2013). In contrast, Blom and Paradis (Citation2015) demonstrate that only L2 learners with TLD displayed an advantage of an inflectional L1, which seems to suggest that positive cross-language transfer may be less available to children with DLD. In a similar vein, Govindarajan and Paradis (Citation2019) and Petersen et al. (Citation2016) argue that transferability of narrative skills might be negatively affected by DLD. It is possible that positive transfer is less available to children with DLD because their L1 knowledge does not offer sufficient basis for transfer (Ebert et al., Citation2014) or because transfer mechanisms as such are negatively affected by the disorder (Blom & Paradis, Citation2015).

It has also been suggested in the literature that cross-language transfer may be only partially available to children with DLD. For instance, some studies report positive cross-language relationships between language-control skills (e.g. phonological awareness, rapid automatic naming), but lack of transfer at the level of vocabulary and grammar (Ebert et al., Citation2014; Verhoeven et al., Citation2012). Tribushinina et al. (Citation2020) suggest that that DLD may selectively affect the mechanisms of positive cross-language transfer in the vulnerable domain of morphosyntax. In their study, L1 vocabulary and grammar predicted the respective EFL skills in the TLD group. In contrast, in the DLD group positive cross-language relationships were only attested in vocabulary but not in morphosyntax. Based on this pattern of results, Tribushinina et al. (Citation2020) suggested that transfer may be less available in the morphosyntactic domain, which is the area of core difficulty in DLD (Leonard, Citation2014). On the other hand, transfer in the lexical domain appears relatively intact, presumably because vocabulary learning largely relies on declarative memory that is supposedly spared in DLD (Lukács et al., Citation2017; Ullman & Pierpont, Citation2005).

Notice, however, that Tribushinina et al. (Citation2020) take positive cross-language relationships between L1 vocabulary size and EFL receptive vocabulary, measured with standardised vocabulary tests such as PPVT, as evidence of positive transfer. However, cross-language correlations in vocabulary sizes present only indirect evidence of positive transfer (Bosma et al., Citation2022). It is plausible that children who know more words in Russian also know more words in English because they recognise similar words (cognates), which accelerates vocabulary learning. However, it is also possible that such correlations are due to an underlying ability (e.g. phonological awareness) that facilitates vocabulary learning in both languages (Sparks et al., Citation2008). In this case, we can still speak of transfer, but not at the level of vocabulary knowledge but at the level of language-control skills. Furthermore, standardised vocabulary tests such as PPVT appear less suitable for research in FL settings because they were designed to measure vocabulary knowledge in the L1. In addition, standardised vocabulary tests were not designed to measure knowledge of cognates. In order to test transferability of word knowledge directly, we need a new task that would take the specific properties of the language pair into account and compare knowledge of cognates and noncognates in this specific language combination. The present study will do just this.

It has been repeatedly shown in the literature that bilingual speakers benefit from their knowledge of cognates, i.e. etymologically related words that are similar in form and meaning (aeroport-airport). Cognates are recognised and retrieved more rapidly (Costa et al., Citation2000; Rosselli et al., Citation2014) and they are also learned and retained more easily than noncognates (e.g. Mulder et al., Citation2019; Sheng et al., Citation2016). To the best of our knowledge, only three studies have so far targeted the ability of children with DLD to use their knowledge of cognates without explicit instruction (Grasso et al., Citation2018; Kambanaros et al., Citation2017; Kohnert et al., Citation2004).

Kohnert et al. (Citation2004) used a picture selection task to compare the ability of monolingual English-speaking children with and without DLD to identify the meaning of words in a new language (Spanish) based on phonological overlap with the English counterparts (e.g. elephant-elefante). The performance of both groups was equally affected by changes in phonological similarity, suggesting that children with DLD also rely on their knowledge of English cognates in learning new words in Spanish. In a similar vein, Grasso et al. (Citation2018) show that English-Spanish bilinguals with DLD were outperformed by their typically-developing bilingual peers in a picture naming task, but the cognate advantage was the same in both groups.

Kambanaros et al. (Citation2017) report a single-case study testing the effects of a cognate therapy on vocabulary development of a trilingual child with DLD. The 8-year-old girl acquired Bulgarian and Cypriot Greek at home and English at an immersion school. She received phonological-based naming therapy on English-Bulgarian-Greek cognates. Even though the intervention only targeted English words, word retrieval in the non-treated languages also improved, about half as much as in English. However, there was no significant improvement in Bulgarian and Greek on cognates that had not been treated in the intervention. These results seem to suggest that positive transfer is available but limited, which might be due to a larger typological distance between English and Greek/Bulgarian and the fact the three languages use different scripts. To explore these possibilities more research on typologically distant languages is warranted.

The present study

The first aim of the present study is to compare the performance of younger and older EFL learners with DLD on English receptive vocabulary. As explained above, typically-developing children learn a FL faster if they start FL lessons at an older age. There is some evidence that older children with DLD also have a learning rate advantage both in naturalistic L2 acquisition (Blom & Paradis, Citation2015; Govindarajan & Paradis, Citation2019) and in classroom FL learning (Tribushinina et al., Citation2020). Studies of age effects in FL learning have commonly used two types of designs: Older and younger starters can be matched either for the length of instruction (e.g. Muñoz, Citation2006; Tribushinina et al., Citation2020) or for chronological age at testing (e.g. Jaekel et al., Citation2017; Pfenninger & Singleton, Citation2016). Both designs have inevitable confounds (Muñoz, Citation2008b). In the former case the younger group is at a disadvantage because older children are more cognitively mature and have more developed test-taking skills. In the latter case, the older groups are at a disadvantage because younger children have had more years of EFL instruction. In the present study we match participants on the amount/length of prior EFL instruction, which means that the older group is older at the moment of testing. In addition, research on age effects can focus either on differences in the learning rate (e.g. Tribushinina et al., Citation2020) or on ultimate attainment after a certain amount of instruction (e.g. Muñoz, Citation2006). The present study focusses on the latter.

The context in which the present study was conducted gives us a unique opportunity to investigate age effects in EFL learning by children with DLD. In 2015, English lessons became mandatory in special education schools in Russia and were introduced into the curricula of all grades (starting in Grade 2). We compare the performance of two groups: (i) children who started English lessons in Grade 2 and (ii) children who started English instruction in Grade 6. The two groups were matched on length and intensity of EFL instruction so that we can compare the performance of early and late starters who have had the same amount of instruction in English. We predict that the older group will outperform the younger group because older children have more advanced cognitive skills and more developed L1 skills (Muñoz, Citation2006).

The second objective of this research is to determine whether children with DLD speaking an L1 that is typologically quite distant from English benefit from cognate relationships in recognising English words. Russian and English represent different branches of the Indo-European language family (Slavic and Germanic respectively). Russian uses a number of English loan words (e.g. компьютер/kompjuter), but there is also a number of cognates of going back to Proto-Indo-European roots (e.g. mother-мать/mat’) or reflecting later borrowings from Latin (e.g. author-автор/avtor) or Greek (e.g. monastery-монастырь/monastyr’). We predict that our participants will perform better on cognates than on noncognates, based on prior studies that found cognate effects in English-Russian bilinguals (Sherkina-Lieber, Citation2004; Temnikova & Nagel, Citation2015), as well as research demonstrating cognate effects in children with DLD (Grasso et al., Citation2018; Kohnert et al., Citation2004). This said, cognate relationships between Russian and English may be concealed by the fact that the two languages use different scripts (Cyrillic and Latin respectively), which is likely to make the task of cognate recognition more demanding (Helms-Park & Perhan, Citation2016). Therefore, all stimuli in this study will be presented orally.

Finally, this paper aims to establish whether age of EFL onset interacts with cognate effects. Research with typically-developing children shows that older children are more likely to benefit from cross-linguistic similarities because they have more advanced L1 skills but also because metalinguistic awareness and the ability to recognise patterns in cross-linguistic similarities and differences improve with age (Bosma et al., Citation2019, Citation2022; Kelley & Kohnert, Citation2012). Since no research has investigated the interaction of age effects and cross-linguistic overlap in children with DLD, no specific hypothesis can be formulated at this stage. To summarise, this research addresses three research questions:

Do older children with DLD outperform younger learners with DLD on English receptive vocabulary after the same amount of EFL instruction?

Do EFL learners with DLD perform better on cognates than on noncognates?

Does the hypothesised cognate advantage increase with age?

Method

Data collection was approved by the institutional review board of the Kuzbas Centre for Psychological, Educational, Medical and Social Child Support.

Participants

Thirty-three monolingual Russian children with DLD participated in this study. There were 18 Grade 6 students (3 female) and 15 Grade 10 students (5 female). All children attended the same special residential school for children with speech and language disorders in the Kemerovo region (Siberia). Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participating children.

The mean age of the 6th graders was 13;05 (range 12;03–15;11); these children were 8–9 years of age when they started their English lessons in 2015. The mean age of the 10th graders was 17;10 (range 16;11–18;8); these children were between 12 and 14 years of age when they started their English lessons. All participants had received four and a half years of English lessons (90 minutes a week, 68 hours per school year) and were tested halfway through their fifth year of English instruction (in Grade 6 and 10 respectively). Hence, the younger group was tested in Grade 6 (after four and a half years of EFL learning), whereas the older group started their English lessons in Grade 6. The older group were in their final year of secondary school when the test was administered.

The participants had been independently diagnosed for DLD based on a clinical evaluation by a multidisciplinary assessment committee consisting of a speech language therapist, a paediatrician, a child psychologist, a psychiatrist and a neurologist. In Russia children with mild language disorders usually attend mainstream schools, and pupils with more severe DLD attend specialist education facilities, like the school participating in this study. For privacy reasons, we were not given access to the diagnostic results. The teachers were asked to select participants based on the following criteria: absence of neurological impairments; no severe visual or auditory problems (based on the yearly medical checks at school); absence of any other known disorder such as autism; lower-than-expected language performance, operationalised as at least two standard deviations below age-appropriate scores of receptive and expressive language on the Fotekova–Akhutina test (Citation2002), including a receptive subtest (comprehension of phonologically similar nouns, receptive vocabulary, comprehension of grammatical constructions) and an expressive subtest (expressive vocabulary, narrative production and retelling, sentence production, sentence repetition, sentence completion, preposition use, inflection and derivation production). In line with recently adopted guidelines, the participants were included in the study if their non-verbal IQ was ‘neither impaired enough to justify a diagnosis of intellectual disability nor good enough to be discrepant with overall language level’ (Bishop, Citation2017, p. 679). The participants had been followed by the second author of this paper, a certified speech language therapist, during their entire school career.

Materials and procedure

To assess word knowledge in English we designed a receptive vocabulary test. The test contained 40 items: 20 Russian-English cognates and 20 noncognates. Cognates were defined as etymologically related words that are semantically and phonologically similar. Some of the cognates were exact translations of each other (equivalent cognates, 13 cases), as in cat – кот/kot. And in several cases the words were clearly semantically related but had a different meaning (non-equivalent cognates, 7 cases). For example, the Russian word фамилия/familia means ‘family-name’ rather than ‘family’ and the Russian грунт/grunt means ‘soil’ rather than ‘ground’.

A measure that is often used to determine the extent of cross-linguistic overlap between cognates is Levenshtein distance; it captures the number of deletions, insertions and substitutions required to transform a word in one language into its cognate in the other language. However, we could not use this measure, since it is based on orthographic transformations, and English and Russian use different alphabetic scripts. Instead, we created a measure of phonological overlap that counted the number of sound substitutions, deletions and insertions. We used the Levenshtein distance between the English word and its Russian counterpart transliterated into the Latic script as a starting point and corrected for significant phonological differences. Since virtually all phonemes in English are different from their Russian counterparts in quality and/or quantity, we disregarded such differences as word-initial aspiration (only present in English) and vowel length (Russian does not have phonemic vowel length contrasts). For instance, the word-initial /t/ in television and телевизор/televizor were treated as overlapping, even though it is aspirated in English and not in Russian. Similarly, the vowel in sport /spɔːt/ and спорт /sport/ was also categorised as overlapping despite the fact that it is long in English and short in Russian. In this way, the phonological distance between cook /kʊk/ and кок /kok/ was coded as 1 (ʊ > o), irrespective of the difference between the word-initial /kh/ and the word-final /k/. All cognates included in the study were non-identical cognates: The minimum number of transformations was 1 and the maximum number was 3 (M = 1.85, SD = 0.88).

The word characteristics are summarised in . The frequency of the words was derived from the CELEX lexical database of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics; it was determined by requesting the occurrence of the lemma in one million words in the COBUILD database for the English words. If the English word could be a noun or a verb (e.g. dance), cumulative frequencies were calculated. There was no significant difference between cognates and noncognates on word length, as measured in letters (t(38) = 1.40, p = 0.17) and syllables (t(26.2) = 1.98, p = 0.06). Most of the words were one-syllable words (13 cognates, 17 noncognates). There were 6 2-syllable words (3 cognates and 3 noncognates). In addition, there were 4 3-syllable words, which were all cognates.

Table 1. Word characteristics (in English), means (SDs).

The noncognates were on average more frequent than cognates (t(24.2) = −2.35, p = 0.03). This difference is mainly due to three high-frequency English words in the noncognate group: man (1629), year (1420) and ask (817). The difference in frequencies also reflects the fact that many English-Russian cognates are Latin-based academic words (e.g. athlete, camera, student) and therefore constitute a less common layer of vocabulary compared to the core vocabulary of Germanic/Slavic origin (e.g. man – человек/čelovek, year-год/god, read-читать/čitat’, hand-рука/ruka). Similar asymmetries in frequencies have been reported for English-Spanish cognates, where Latin-based cognates are usually low-frequency academic words in English (Ramírez et al., Citation2013).

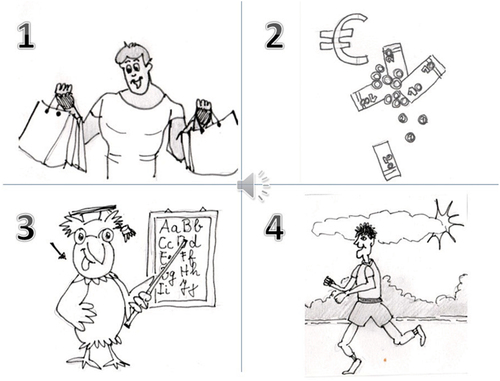

The test items were presented using PowerPoint. On each slide the participants saw four pictures (one target picture and three foils) and heard a target word pronounced with a British English accent. The pictures were black-and-white drawings created specifically for this test (see sample stimulus in ). The participants were asked to point to the picture (or indicate its number) corresponding to the word they heard. The position of the target picture was counterbalanced across trials.

The test started with two practice trials: tree and ear. The participants were given feedback on the correctness of their response on these two trials. After that, the main test started. The recordings were played only once, but the participants were allowed to take as long as necessary to provide an answer. The experimenter noted the number of the picture selected by the participant on the scoring form.

After the test the participants were asked whether they had any extracurricular exposure to English. None of the participants watched or listened to English-spoken programmes, and none had contact with English-speaking foreigners. Exposure to written English outside of the classroom was limited to homework.

Data analysis

The responses were coded as correct (1) or incorrect/missing (0). This study implemented multilevel modelling because this statistical approach takes into account that individuals that share the same environment (e.g. classroom) have more in common than those who do not (Hox et al., Citation2017). The participants of the present study were nested in different grades and classes. The 6th graders came from two different classes (12 from class 6A and 6 from class 6B) and the 10th graders also came from two different classes (8 from class 10A and 7 from class 10B). The data were analysed using multilevel logistic regression in R (Bates et al., Citation2013). Item and Participant nested in Class (Class:Participant) were included as random effects.

Results

The performance of the younger group and the older group on cognates and noncognates is presented in . Overall, the proportion of correct responses was 0.66 (SD = 0.47), which is well above chance (0.25). Visual inspection of the data suggests similar performance across the two groups and higher scores on cognates than on noncognates. To test our hypotheses we created a model with Grade (Grade 6; Grade 10), Word Category (Cognate; Noncognate) and their interaction as main effects. The performance of Grade 6 on cognates was taken as the baseline. Age was included as a covariate to control for variation at the time of testing. Item and Participant nested in Class (Class:Participant) were included as random effects. The model estimates are presented in .

Figure 2. Estimated probability of correct responses, by Grade and Word Category (the error bars represent SE 95% CI).

Table 2. Model coefficients for the effects of grade and word category.

The results of the statistical analysis demonstrate that there was a significant effect of Word Category: Scores on cognates were higher than scores on non-cognates. There was no effect of Grade, and no significant interaction between Word Category and Grade.

As described in the Method section, there were two types of cognates: equivalent cognates (which were exact translations) and non-equivalent cognates (semantically related words with a different meaning). An anonymous reviewer suggested that the results for these two categories might be different, with the non-equivalent cognates being more difficult than the equivalent cognates. Therefore, we ran a model in which the factor Word Category had 3 levels: Noncognate, Equivalent Cognate, and Non-Equivalent Cognate. The performance of Grade 6 on noncognates was taken as the baseline. The model is presented in , and the mean scores are presented in . The model shows that the cognate advantage was entirely due to the equivalent cognates, for which the performance was better than for the noncognates. There was no significant difference in performance between the noncognates and the non-equivalent cognates. The equivalent cognate advantage was the same for both age groups, as evidenced by the non-significant interactions between Grade and Cognate Type.

Figure 3. Estimated probability of correct responses, by Grade and Cognate Type (the error bars represent SE 95% CI).

Table 3. Model coefficients for the effects of grade and cognate type.

Discussion

This study contributes to the scarce literature on FL learning by children with DLD in a classroom setting. The aims of this study were two-fold: (i) to compare the performance of early and late starters on English receptive vocabulary after four and a half years of English lessons in special education, and (ii) to determine if EFL learners with DLD capitalise on cognate vocabulary and whether this capacity is age-dependent. These questions will be discussed in order.

No effect of starting age and age at testing

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found no differences between the early-start group and the late-start group. Based on classroom research with typically-developing EFL learners, we predicted that older children would outperform younger children due to their more advanced cognitive and linguistic skills. Research in which early and late starters are matched on age at testing but differ in the hours of instruction generally shows no differences between the two groups by the end of secondary school despite the fact that early starters have had more years of FL instruction (Pfenninger, Citation2014, Citation2017; Pfenninger & Singleton, Citation2016). These findings suggest that older children make faster progress and attain the same proficiency level in a shorter period of time. Also studies that match early and late starters on the length of instruction but not on biological age at testing, as in the present study, report a learning rate advantage of older children, as evidenced by higher scores in the older cohorts (Muñoz, Citation2006). In our results of the EFL learners with DLD we do not find this effect in the domain of vocabulary. Research on naturalistic L2 acquisition by children with DLD has demonstrated positive effects of a later age of L2 onset in the domain of morphosyntax (Blom & Paradis, Citation2015) and narrative skills (Govindarajan & Paradis, Citation2019). Age effects may be less strong in instructed settings because differences in, for example, procedural learning ability are levelled off through explicit instruction (Erlam, Citation2005).

It might also be the case that the differences were evident in the initial stages, but the early starters were able to catch up. The longitudinal study by Tribushinina et al. (Citation2020) found that age of onset was positively associated with the rate of vocabulary learning by EFL learners with DLD in the first two years of EFL instruction. The younger group in our study were 8–9 years old when English lessons were introduced to the curriculum, whereas the older group was between 12 and 14 years of age. However, at testing the younger group was already above age 12. Prior research with typically-developing EFL learners reveals that the gap between early and late starters starts to close when early starters enter puberty (around age 12) and reach a comparable level of cognitive development as later starters at the time they started their English lessons (Muñoz, Citation2006). In the light of these results, it is possible that we did not capture any differences after four and a half years of instruction because they had already vanished prior to our study.

Our findings also reveal that early FL instruction is not harmful to children with DLD. Hypothetically, it is possible that an early start may be disadvantageous because younger children learn slowly and may become demotivated, which, in turn, may negatively affect their FL performance (cf., Jaekel et al., Citation2017). However, we did not find any differences between early starters in Grade 6 and late starters in Grade 10 (final year). This means that the early starters still have more than four years to improve their EFL skills and it is plausible to assume that they will exceed the EFL level of the older group by the end of secondary school.

Cognate effects

As predicted, the participants performed better on cognates than on noncognates, and this effect was equally strong in Grade 6 and Grade 10. This shows that children with DLD benefit from positive L1 transfer in the acquisition of EFL vocabulary, which is in line with three earlier studies that demonstrated a cognate advantage in L2 acquisition by children with DLD (Grasso et al., Citation2018; Kambanaros et al., Citation2017; Kohnert et al., Citation2004). This study extends this finding to instructed FL settings and demonstrates that children with DLD are able to use their L1 vocabulary knowledge even if their L1 is typologically quite distant from English and uses a different script.

In contrast to previous research on bilinguals with typical language development (Kelley & Kohnert, Citation2012), we did not find stronger reliance on cross-linguistic similarities in older children. One explanation of age effects in cognate facilitation is that older typically-developing children have developed metalinguistic awareness that allows them to recognise patterns, especially if cognates show relatively little phonological overlap (Bosma et al., Citation2019). It might be the case that we did not see a similar pattern in our DLD group because children with DLD have lower levels of metalinguistic awareness (Kamhi & Koenig, Citation1985) and/or because they are less good at recognising patterns due to procedural learning deficits (Ullman & Pierpont, Citation2005).

The performance on all cognates was around or above 60% with the exception of three words: ground (33%), beard (45%) and athlete (0%). The former two words represent less transparent cognates with three cross-linguistic transformations. Some children knew the word or could use their cognate knowledge, other children guessed and their erroneous responses were more or less equally distributed across the three foils. For the most difficult cognate athlete, the vast majority of the participants (27/33) chose picture nr. 3 (owl/teacher), see . Our post hoc explanation of this pattern is that the children misinterpreted this word as ‘alphabet’ (алфавит/alfavit) which is phonologically similar to athlete and may be seen as a false friend. Notice that there is an alphabet board behind the teacher in that picture; we were not aware of this limitation when developing the test. The reason why the children chose the false friend is probably because алфавит/alfavit is a very frequent word, especially in the school context, whereas атлет/atlet is a low-frequency word (спортсмен/sportsmen being its high-frequency counterpart). Nevertheless, the fact that the children probably chose the false friend supports the idea that they draw upon their L1 knowledge for learning new words in English.

Overall, the performance of our participants on the receptive vocabulary test was quite good, which shows that children with DLD are capable of making progress in FL learning. Another promising finding is that learners with DLD use their knowledge of cognates in learning EFL vocabulary, even though their vocabulary width and depth tend to be smaller than in TLD (Dosi & Gavriilidou, Citation2020; Leonard & Deevy, Citation2004). Hence, a threshold of L1 vocabulary size needed to support L2/FL learning might be relatively low (cf., D’Angelo et al., Citation2017). This said, the cognate advantage was limited to translation equivalents. The performance on cognates that are semantically related but not exactly equivalent was not different from the performance on noncognates. This finding echoes earlier results demonstrating that the performance of children with and without DLD on cognates increases as a function of phonological overlap (Bosma et al., Citation2019; Kohnert et al., Citation2004) and reveals that gradual performance is also determined by the degree of semantic overlap. The lack of cognate advantage in the non-equivalent category could be related to earlier findings suggesting that semantic networks of individuals with language disorders are less strong and less cohesive (Beckage et al., Citation2011) and that DLD is associated with deficits in semantic processing of vocabulary (Kornilov et al., Citation2015). However, in the absence of a control group of typically-developing participants, this possibility remains speculative.

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that cognate knowledge and cognate awareness are strong predictors of L2 vocabulary and L2 reading comprehension (D’Angelo et al., Citation2017; Dressler et al., Citation2011; Hipfner-Boucher et al., Citation2016; Proctor & Mo, Citation2009). In addition, cognate knowledge mediates positive cross-language transfer of morphological awareness, which is also an important predictor of L2 proficiency (Ramírez et al., Citation2013). Therefore, the capacity of children with DLD to use their L1 knowledge of cognates is likely to have a broader positive impact on L2/FL development. Taken together, there are reasons to assume that children with DLD hold promise to become successful EFL learners, even in settings where exposure to English is extremely limited. This said, it might still be useful to integrate explicit cognate training in FL lessons. Previous work in immersion settings indicates that not all children are equally adept to recognise cognates (Ramírez et al., Citation2013) and that children as young as age 6 are amenable to instruction raising cognate awareness (Hipfner-Boucher et al., Citation2016). In a similar vein, intervention studies demonstrate that L2 learners with TLD (Dressler et al., Citation2011; Helms-Park & Perhan, Citation2016) and DLD (Dam et al., Citation2020) use the cognate strategy more after explicit instruction on similarities and differences in L1 and L2 vocabulary. We support earlier proposals to provide vulnerable L2 learners with explicit cognate instruction and extend these proposals to a FL setting.

Limitations and future directions

The introduction of EFL instruction to special education throughout the whole grade range in 2015 gave us a unique chance to compare the performance of pupils with different onsets of FL lessons. However, research on age effects is always constrained by the method of matching groups of participants (Muñoz, Citation2008b). If early and late starters are matched for chronological age at testing (e.g. Pfenninger & Singleton, Citation2016), older starters may be at a disadvantage because younger starters have had more years of FL instruction. If early and late starters are matched on the number of instruction hours as in this study (e.g. Muñoz, Citation2006), older starters may have an advantage due to their greater cognitive maturity and better test-taking skills. A more rigorous research design where groups would be matched on both age at testing and amount of instruction (but differ on the intensity of instruction) is hardly feasible to implement due to practical constraints in real educational settings.

Another limitation of our study is that the noncognate words were significantly more frequent and (not significantly) longer than cognates. Even though this asymmetry makes the conclusion of the cognate advantage even stronger because children perform worse on less frequent words (Mainela-Arnold et al., Citation2008) and words having more syllables (Archibald & Gathercole, Citation2006), future research would benefit from a more balanced design in which the two groups of words are matched not only on word length but also on word frequency.

Future research will also benefit from comparing the performance of children with and without DLD on the same test to determine whether cognate facilitation and age effects operate similarly in typically-developing populations (cf., Grasso et al., Citation2018).

Finally, our scope was restricted to the lexical domain. Based on a few previous studies on L2/FL learning by children with DLD, it is plausible to assume that cross-language transfer might be more vulnerable in the area of morphosyntax (Blom & Paradis, Citation2015; Tribushinina et al., Citation2020). It will be a matter for future research to compare positive transfer across different language domains in the same learners in order to determine whether DLD selectively affects transfer mechanisms in the most vulnerable domains.

Conclusion

This study has shown that children with DLD can successfully learn foreign vocabulary even in settings where their exposure to the target language is largely limited to the classroom and even if their L1 is a typologically distant language using a different script. Age of EFL onset did not affect performance on English receptive vocabulary, which suggests that an early start of FL instruction may be beneficial for children with DLD because it gives them more time to learn the target language. Vocabulary learning is facilitated by cognate recognition, which is evidence that learners with DLD can benefit from positive cross-language transfer in the lexical domain.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. We also would like to thank the participating school, all children and their caregivers for making this investigation possible. We are very grateful to Angelique Niemann-Jager, Geke Niemann and Gabriëlla Lahdo for making the test materials. This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) under Grant 015.015.061 to the first author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For convenience, we present both the original Russian words and their transliterations throughout the paper.

References

- Archibald, L. M. D., & Gathercole, S. E. (2006). Nonword repetition: A comparison of tests. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49(5), 970–983. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2006/070)

- Arnett, K., Mady, C., & Muilenburg, L. (2014). Canadian FSL teacher candidate beliefs about students with learning difficulties. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4(3), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.4.3.447-457

- Bates, D., Maechler, M., & Bolker, B. (2013). Lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes (R package version 0.999999-2). http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4.

- Beckage, N., Smith, L., & Hills, T. (2011). Small words and semantic network growth in typical and late talkers. PLoS One, 6(5), e19348. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019348

- Bishop, D. V. M. (2017). Why is it so hard to reach agreement on terminology? The case of developmental language disorder (DLD). International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 52(6), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12335

- Blom, E., & Paradis, J. (2013). Past tense production by English second language learners with and without language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 56(1), 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0112)

- Blom, E., & Paradis, J. (2015). Sources of individual differences in the acquisition of tense inflection by English second language learners with and without specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 36(4), 953–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S014271641300057X

- Bosma, E., Blom, E., Hoekstra, E., & Versloot, A. (2019). A longitudinal study on the gradual cognate facilitation effect in bilingual children’s Frisian receptive vocabulary. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1254152

- Bosma, E., Bakker, A., & Blom, E. (2022). Supporting the development of the bilingual lexicon through translanguaging: A realist review integrating psycholinguistics with educational sciences. European Journal of Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-021-00586-6

- Bruck, M. (1982). Language disabled children: Performance in an additive bilingual education program. Applied Psycholinguistics, 3(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1017/S014271640000415X

- Costa, A., Caramazza, A., & Sebastian-Galles, N. (2000). The cognate facilitation effect: Implications for models of lexical access. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26(5), 1283–1296. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.26.5.1283

- D’Angelo, N., Hipfner-Boucher, K., & Chen, X. (2017). Predicting growth in English and French vocabulary: The facilitating effects of morphological and cognate awareness. Developmental Psychology, 53(7), 1242–1255. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000326

- Dam, Q., Pham, G. T., Pruitt-Lord, S., Limon-Hernandez, J., & Goodwiler, C. (2020). Capitalizing on cross-language similarities in intervention with bilingual children. Journal of Communication Disorders, 87, 106004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2020.106004

- Dosi, I., & Gavriilidou, Z. (2020). The role of cognitive abilities in the development of definitions by children with and without developmental language disorder. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 49(5), 761–777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09711-w

- Dressler, C., Carlo, M. S., Snow, C. E., August, D., & White, C. E. (2011). Spanish-speaking students’ use of cognate knowledge to infer the meaning of English words. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 14(2), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728910000519

- Ebert, K. D., Pham, G., & Kohnert, K. (2014). Lexical profiles of bilingual children with primary language impairment. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 17(4), 766–783. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728913000825

- Erlam, R. (2005). Language aptitude and its relationship to instructional effectiveness in second language acquisition. Language Teaching Research, 9(2), 147–171. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168805lr161oa

- Evans, J., Saffran, J. R., & Robe-Torres, K. (2009). Statistical learning in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52(2), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0189)

- Fotekova, T. A., & Akhutina, T. V. (2002). Diagnostika reˇcevyx narušenij škol’nikov s ispol’zovaniem nejropsixologiˇceskix metodov (Diagnosis of speech disorders by neuropsychological methods). Arkti.

- Genesee, F., & Lindholm-Leary, K. (2013). Two case studies of content-based language education. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 1(1), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.1.1.02gen

- Genesee, F., & Fortune, T. W. (2014). Bilingual education and at-risk students. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 2(2), 196–209. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.2.2.03gen

- Goriot, C. (2019). Early-English education works no miracles: Cognitive and linguistic development of mainstream, early-English, and bilingual primary-school pupils in the Netherlands [Doctoral dissertation], Radboud Universiteit.

- Govindarajan, K., & Paradis, J. (2019). Narrative abilities of bilingual children with and without developmental language disorder (SLI): Differentiation and the role of age and input factors. Journal of Communication Disorders, 77, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2018.10.001

- Grasso, S. M., Peña, E. D., Bedore, L. M., Hixon, G., & Griffin, Z. M. (2018). Cross-linguistic cognate production in Spanish–English bilingual children with and without Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61(3), 619–633. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_JSLHR-L-16-0421

- Helms-Park, R., & Perhan, Z. (2016). The role of explicit instruction in cross-script cognate recognition: The case of Ukrainian-speaking EAP learners. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 21, 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2015.08.005

- Hipfner-Boucher, K., Pasquarella, A., Chen, X., & Deacon, H. (2016). Cognate awareness in French immersion students: Contributions to grade 2 reading comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 20(5), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2016.1213265

- Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & Van de Schoot, R. (2017). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Jaekel, N., Schurig, M., Florian, M., & Ritter, M. (2017). From early starters to late finishers? A longitudinal study of early foreign language learning in school. Language Learning, 67(3), 631–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12242

- Kambanaros, M., Michaelides, M., & Grohmann, K. K. (2017). Cross-linguistic transfer effects after phonologically based cognate therapy in a case of multilingual specific language impairment (SLI). International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 52(3), 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12270

- Kamhi, A. G., & Koenig, L. A. (1985). Metalinguistic awareness in normal and language- disordered children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 16(3), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461.1603.199

- Kelley, A., & Kohnert, K. (2012). Is there a cognate advantage for typically developing Spanish-speaking English-language learners? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0022)

- Kohnert, K., Windsor, J., & Miller, R. (2004). Crossing borders: Recognition of Spanish words by English-speaking children with and without language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 25(4), 543–564. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716404001262

- Kornilov, S. A., Magnuson, J. S., Rakhlin, N., Landi, N., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2015). Lexical processing deficits in children with developmental language disorder: An event-related potentials study. Development and Psychopathology, 27(2), 459–476. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579415000097

- Krashen, S., Long, M., & Scarcella, R. (1979). Age, rate and eventual attainment in second language acquisition. TESOL Quarterly, 13(4), 573–582. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586451

- Larson-Hall, J. (2008). Weighing the benefits of studying a foreign language at a younger starting age in a minimal input situation. Second Language Research, 24(1), 35–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658307082981

- Leonard, L. B., & Deevy, P. (2004). Lexical deficits in specific language impairment. In L. Verhoeven & H. van Balkom (Eds.), Classification of developmental language disorders: Theoretical issues and clinical implications (pp. 209–233). Erlbaum.

- Leonard, L. B. (2014). Children with Specific Language Impairment. MIT Press.

- Lukács, Á., Kemény, F., Lum, J. A. G., & Ullman, M. T. (2017). Learning and overnight retention in declarative memory in specific language impairment. PLoS ONE, 12(1), e0169474. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169474

- Mainela-Arnold, E., Evans, J. L., & Coady, J. A. (2008). Lexical representations in children with SLI: Evidence from a frequency-manipulated gating task. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51(2), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2008/028)

- Marinova-Todd, S. H., Colozzo, P., Mirenda, P., Stahl, H., Kay-Raining Bird, E., Parkington, K., Cain, K., Scherba de Valenzuela, J., Segers, E., MacLeod, A. A. N., & Genesee, F. (2016). Professional practices and opinions about services available to bilingual children with developmental disabilities: An international study. Journal of Communication Disorders, 63, 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2016.05.004

- Mulder, E., Van de Ven, M., Segers, E., & Verhoeven, L. (2019). Context, word, and student predictors in second language vocabulary learning. Applied Psycholinguistics, 40(1), 137–166. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716418000504

- Muñoz, C. (2006). The effects of age on foreign language learning: The BAF project. In C. Muñoz (Ed.), Age and the rate of foreign language learning (pp. 1–40). Multilingual Matters.

- Muñoz, C. (2008a). Age-related differences in foreign language learning: Revisiting the empirical evidence. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 46(3), 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1515/IRAL.2008.009

- Muñoz, C. (2008b). Symmetries and asymmetries of age effects in naturalistic and instructed L2 learning. Applied Linguistics, 29(4), 578–596. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm056

- Paradis, J. (2016). An agenda for knowledge-oriented research on bilingualism in children with developmental disorders. Journal of Communication Disorders, 63, 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2016.08.002

- Petersen, D. B., Thomsen, B., Guiberson, M. M., & Spencer, T. D. (2016). Cross-linguistic interactions from second language to first language as the result of individualized narrative language intervention with children with and without language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 37(3), 703–724. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716415000211

- Pfenninger, S. E. (2014). The misunderstood variable: Age effects as a function of type of instruction. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(3), 529–556. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.3.8

- Pfenninger, S. E., & Singleton, D. (2016). Affect trumps age: A person-in-context relational view of age and motivation in SLA. Second Language Research, 32(3), 311–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658315624476

- Pfenninger, S. E. (2017). Not so individual after all: An ecological approach to age as an individual difference variable in a classroom. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 7(1), 16–46. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.1.2

- Proctor, P., & Mo, E. (2009). The relationship between cognate awareness and English comprehension among Spanish-English bilingual fourth grade students. TESOL Quarterly, 43(1), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2009.tb00232.x

- Ramírez, G., Chen, X., & Pasquarella, A. (2013). Cross-linguistic transfer of morphological awareness in Spanish-speaking English language learners: The facilitating effect of cognate knowledge. Topics in Language Disorders, 33(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0b013e318280f55a

- Rosselli, M., Ardila, A., Jurado, M. B., & Salvatierra, J. L. (2014). Cognate facilitation effect in balanced and non-balanced Spanish-English bilinguals using the Boston Naming Test. International Journal of Bilingualism, 18(6), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006912466313

- Scherba de Valenzuela, J., Kay-Raining Bird, E., Parkington, K., Mirenda, P., Cain, K., MacLeod, A. N., & Segers, E. (2016). Access to opportunities for bilingualism for individuals with developmental disabilities: Key informant interviews. Journal of Communication Disorders, 63, 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2016.05.005

- Sheng, L., Lam, B. P. W., Cruz, D., & Fulton, A. (2016). A robust demonstration of the cognate facilitation effect in first-language and second-language naming. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 141, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2015.09.007

- Sherkina-Lieber, M. (2004). The cognate facilitation effect in bilingual speech processing: The case of Russian-English bilingualism. Cahiers Linguistiques D’Ottawa, 32, 108–121. http://clo.canadatoyou.com/32/Sherkina-Lieber(2004)CLO32_108-127.pdf

- Siu, C. T.-S., & Ho, C. S.-H. (2015). Cross-language transfer of syntactic skills and reading comprehension among young Cantonese-English bilingual students. Reading Research Quarterly, 50(3), 313–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.101

- Sparks, R., Humbach, N., & Javorsky, J. (2008). Individual and longitudinal differences among high and low-achieving, LD, and ADHD L2 learners. Learning and Individual Differences, 18(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2007.07.003

- Temnikova, I. G., & Nagel, O. V. (2015). Effects of cognate and relatedness status on word recognition in Russian-English bilinguals of upper-intermediate and advanced levels. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 200, 381–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.082

- Tribushinina, E., Dubinkina-Elgart, E., & Rabkina, N. (2020). Can children with DLD acquire a second language in a foreign-language classroom? Effects of age and cross-language relationships. Journal of Communication Disorders, 88, 106049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2020.106049

- Ullman, M., & Pierpont, M. T. (2005). Specific language impairment is not specific to language: The procedural deficit hypothesis. Cortex, 41(3), 399–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70276-4

- Verhoeven, L., Steenge, J., & Van Balkom, H. (2012). Linguistic transfer in bilingual children with specific language impairment. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 47(2), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00092.x

- Zoutenbier, I., & Zwitserlood, R. (2019). Exploring the relationship between native language skills and foreign language learning in children with developmental language disorders. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 33(7), 641–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699206.2019.1576769