?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Prior research has shown that narrative coherence is associated with more positive emotional responses in the face of traumatic or stressful experiences. However, most of these studies only examined narrative coherence after the stressor had already occurred. Given the outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease COVID-19 in March 2020 in Belgium and the presence of data obtained two years before (February 2018), we could use our baseline narrative coherence data to predict emotional well-being and perceived social support in the midst of the pandemic. In a sample of emerging adults (NT1 = 278, NT2 = 198), higher baseline coherence of narratives about positive autobiographical experiences predicted relative increases in emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the relation between the coherence of positive narratives and emotional well-being was partially mediated by perceived social support. These findings suggest that narrative coherence could be an enhancement factor for adaptive emotional coping with stressful situations, in part by evoking more supportive social reactions. This study demonstrates the importance of researching cognition (narrative coherence) and emotion (well-being) to shed light on pressing societal matters such as the global COVID-19 pandemic.

The extent to which individuals narrate coherently about their autobiographical memories has been shown to reflect and predict their emotional adjustment (e.g. Adler et al., Citation2016; Waters & Fivush, Citation2015). Narrative coherence can be defined as the extent to which either full life narratives (i.e. global coherence; Habermas & Bluck, Citation2000; Habermas & de Silveira, Citation2008; Habermas & Reese, Citation2015; Köber et al., Citation2015) or single-event narratives (i.e. local coherence; Baerger & McAdams, Citation1999; Reese et al., Citation2011) make sense to a naïve listener and are able to convey the content and meaning of the described events in a structurally and thematically cohesive manner.

Narrative coherence is commonly thought of as a multidimensional construct, albeit defined and used across a variety of disciplines in slightly distinct manners (Adler et al., Citation2018). In this study, we adhered to the “Narrative Coherence Coding Scheme” (NaCCS) by Reese et al. (Citation2011). These authors define coherence as a general cognitive-developmental skill, needed to structure narratives about high-impact positive or negative memories (i.e. high points and low points), that develops over time and in relation to event-processing (Fivush et al., Citation2017; Reese et al., Citation2011; Waters et al., Citation2019). According to the NaCCS, coherence consists of three dimensions: context, chronology and theme (Reese et al., Citation2011). More specifically, a narrative is coherent to the extent that (1) the context of the described event is defined, consisting of specific time and place indications, (2) the event is structured in a logical and chronological order using time indication words (e.g. thereafter, next, …), and (3) the event is elaborated on not merely factually, but also emotionally, and includes a resolution, closure, a link to other important events, or to the self (Reese et al., Citation2011).

Previous research has focused on the role of narrative coherence in the face of traumatic or very stressful memories (e.g. Booker et al., Citation2020; Tuval-Mashiach et al., Citation2004; Waters et al., Citation2013), assessing the relation between coherence and psychological outcomes or emotional well-being. Specifically, these studies have measured the coherence of the traumatic memories themselves, and therefore, necessarily measured coherence after the occurrence of the stressful/traumatic event, to assess concurrent or subsequent emotional responses. The theoretical rationale is that it is coherence of the traumatic experience itself that is critical in how the individual processes the event emotionally.

Obviously, it is important to investigate how narrative coherence of traumatic memories (or coherence measured during stressful times) predicts emotional well-being, but we argue that it is equally important to investigate whether coherence, when assessed prior to adversity in an unrelated narrative, can predict future emotional adjustment to adversity. In other words, in this study, we investigate if coherence can be conceptualised as a more general cognitive skill that not only indicates adaptive processing of a specific traumatic event, but also more broadly reflects and predicts resilience in the face of life’s challenges.

We were afforded the opportunity to investigate this question in the course of an ongoing longitudinal study that began before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, we were able to examine if the coherence of an autobiographical narrative of a significant experience unrelated to the stressor and assessed even before the stressor has taken place, related prospectively to emotional responses in times of stress. To our knowledge, there is not much known about the predictive value of baseline narrative coherence of a significant, though not necessarily stressful event, for future emotional adjustment to a stressful situation. Some preliminary evidence suggests that baseline narrative coherence predicts future emotional coping with the stressful experience of failing on exams; Vanderveren et al. (Citation2020b) found that students who displayed higher baseline narrative coherence reported less subjective distress after failing on exams, as compared to students with low baseline narrative coherence.

In the present study, we had the opportunity to put these ideas to the test, due to the availability of data obtained two years ago and the sudden rise of stressful circumstances. The outbreak of COVID-19 and the related quarantine/social isolation measures that were taken to prevent further spreading are known to evoke serious stress responses, even in healthy individuals (Brooks et al., Citation2020; Vanaken et al., Citation2020b). Hence, we could investigate the relations between baseline narrative coherence and emotional well-being during the pandemic. We expected that higher baseline narrative coherence would be related to relative increases in emotional well-being over a two-year interval, during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Moreover, we aimed to extend previous preliminary findings by investigating a possible mediator underlying the relation between narrative coherence and future emotional adjustment during stress. Little is yet known about the mechanisms that explain the relation between narrative coherence and emotional well-being. However, there is some suggestion that narrative coherence is related to perceived social support as well as emotional well-being.

Social support is crucial for our emotional well-being, as is shown by a large body of evidence on the positive relation between social support and mental health (Harandi et al., Citation2017; Ozbay et al., Citation2007). Intriguingly, social support has also shown some relations to narrating and narratives in ways that might help us better understand how narratives are related to emotional well-being. For example, Waters and Fivush (Citation2015) observed that narrative coherence was positively associated with the quality of personal relationships. Also, Burnell et al. (Citation2010) showed, in a sample of veterans, that narrative coherence was positively related to pleasant communication with their family and that the more incoherent veterans were, the more they found communication to be unsatisfactory. Finally, there is recent experimental evidence that speakers who narrate coherently receive more positive social responses from listeners (like social support), in comparison to incoherent narrators (Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020; Vanaken et al., Citation2020a). However, in one study, this effect emerged only for narratives about positive life experiences (high points), whereas for negative narratives (low points) there was no difference in social support depending on the coherence of the narratives (Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020). Still, there is emerging evidence that social support garnered form narrating coherently to others may play a role in how narrative coherence leads to better emotional outcome.

Hence, in this study, we built on previous research by investigating perceived social support as a possible mediator in the relation between coherence and emotional responding. We expected that the relation between narrative coherence and emotional well-being would be mediated by perceived social support. Specifically, we predicted that the more coherently one narrates, particularly about positive life events, the more positive the social response would be. In turn, feeling socially supported would be positively related to emotional adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic (Harandi et al., Citation2017). Conversely, narrating more incoherently, again particularly in positive narratives, might be associated with fewer positive social reactions, and might cause the social network to progressively withdraw (Coyne, Citation1976; Vanaken et al., Citation2020a). This lack of social support would in turn relate to the risk for the development or the worsening of emotional disorders, especially when stress is heightened (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Brooks et al., Citation2020).

In sum, in the present study, we expected that baseline narrative coherence would predict relative increases in emotional well-being over a two-year time period during which a highly stressful and challenging world event occurred. Furthermore, we predicted that the longitudinal relation between narrative coherence and emotional well-being would be mediated by perceived social support. Thus, we predicted to see both a direct relation between narrative coherence and emotional adjustment, as well as an indirect relation between narrative coherence and emotional adjustment, mediated via perceived social support.

Methods

Participants

A total of 278 first-year psychology students, of whom 248 (88.3%) were women and 30 (10.7%) were men, participated at T1. Participants were between 17 and 22 years old, with an average age of M = 18.46, SD = 0.78. The sample that took part at T2 consisted of 198 participants, of whom 24 were male (12.1%) and 174 were female (87.9%). At T2, their ages were in between 19 and 24, averaging at M = 20.61, SD = 0.87. The gender distribution of the group that took part at T1 was not significantly different from the one at T2, p > .05.

We conducted a post-hoc power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., Citation2007), based on the mean explained variance from our regression analyses (R2 = .27) as an effect size estimate, with a critical alpha of 0.05, and showed that our sample was sufficiently large, reaching a very good power of .99.

Material and measures

Narrative coherence

Online writing task

In a computerised narrative coherence writing task, participants were instructed to write for a minimum of 5 min about an autobiographical high and low point in their life (in counterbalanced order across participants). Participants were encouraged to take their time to think and write about impactful events, as no maximum time to do so was given. The specific instructions were as follows: “I would like for you to write about your most positive/negative experience of your life. This should be an extremely emotional event that has affected you and your life. You may include the facts of the event, as well as your deepest thoughts and feelings. All of your writing will be kept confidential. Do not worry about spelling, sentence structure, or grammar. There is no time limit on your writing; you may write about this event for as long as needed. However, we ask you to spend a minimum of 5 min on this task, to make sure you spend enough time thinking about and writing out the event.”

Coding system

The written/typed memories were coded manually according to the Narrative Coherence Coding Scheme (NaCCS; Reese et al., Citation2011). Using this coding scheme, each narrative was assigned a total score from 0 to 9, consisting of the sum of the scores on the 3 dimensions that the scheme entails, namely context (0–3), chronology (0–3), theme (0–3). The narrative is scored on context by evaluation of the presence and specificity of indications of time and place in the narrative. Chronology is assessed based on the logical and chronological order in which the events are described, as well as the usage of time indication words that structure the narrative. Theme is scored according to the emotional interpretation and evaluations of the events, elements of resolution and closure, as well as causal and autobiographical links. Specific scoring details can be found in Supplementary Material 1 (adopted from Reese et al., Citation2011, p. 436). Total narrative coherence (0–9) at each time point was calculated by taking the mean of the scores for positive (0–9) and negative (0–9) narratives. However, based on previous work suggesting differences between positive and negative narratives (Baker-Ward et al., Citation2005; Fivush et al., Citation2003, Citation2008; Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020; Vanderveren et al., Citation2019), not only total coherence but also the coherence of positive and negative narratives were taken into account separately. Thirty percent of narratives at T1 were independently scored by two trained coders of whom one was the first author. Data showed that good inter-rater reliability was achieved, ICCcontext = .83; ICCchronology = .94; ICCtheme = .96. The remaining 70 percent of the narratives at T1 were coded by the first author. All narratives at T2 were coded by the first author, based on the NaCCS (Reese et al., Citation2011).

Emotional well-being

Emotional well-being was measured using the Flourishing Scale (FS: Diener et al., Citation2009; Dutch translation: Van Egmond & Hanke, Citationn.d.). This instrument consists of 8 items to assess the respondent’s self-perceived psychosocial prosperity and has shown to be related to the full version of the psychological well-being scales that Ryff (Citation1989) developed. It is a brief measurement that provides a single score of well-being, which has shown to be reliable, Cronbach’s α = .86, and highly temporally stable, r = .71 (Diener et al., Citation2009). Example items are for instance: “I lead a purposeful and meaningful life”, or “I am optimistic about my future”.

Perceived social support

We assessed perceived social support with the Dutch Social Support List – Interactions (SSL-I, 34 items). The SSL-I has proven to have good construct validity, high internal reliability (.90 ≤ Cronbach’s α ≤ .93) and high test-retest stability (r = .77) (Van Sonderen, Citation2012). Example items for are: “People confide in you”, “People are affectionate towards you”, and “People ask you to join in”. Importantly, note that this questionnaire measures the general perceived social support (i.e. the general quality of relationships), and not specific social reactions to specific narratives. The assessed perceived social support is thus a general measure of the social environment of participants and does not assess concrete social responses of a concrete situation in which the assessed narratives were shared.

Procedure

The first measurement (T1) took place in February 2018.Footnote1 The second measurement (T2) was in March 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic in Belgium. Individuals who participated at T1 were invited through the Experiment Management System of the university to participate in a follow-up measurement. Procedural elements and instructions were kept identical at both times, as the entire procedure was computerised and consisted of the same online writing task and questionnaires. This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and approved by the Social and Societal Ethics Committee of the KU Leuven (G-2018 10 1357). Before conducting the second wave of measurements, our key variables, questions and hypotheses were pre-registered on AsPredicted (http://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=nc88fs).

Data-analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 26. Descriptive statistics were calculated to get insight into the means and standard deviations of our variables and to investigate whether measures at T1 differed from measures at T2. Pearson correlations at T1 and at T2 were calculated to examine the relations between narrative coherence, perceived social support and emotional well-being. Prospective regression analyses were run with narrative coherence at T1 as predictor and emotional well-being at T2 as the criterium. The predictive value for emotional well-being was assessed over a 2-year time interval, after controlling for emotional responding at T1. Two different series of regression analyses were conducted. In the first series (1a), total coherence was inserted as predictor, whereas in the second series (2a), positive and negative narrative coherence were predictors. In addition, extra regressions (1b, 2b) were run in which perceived social support was added to the model in order to test the mediation hypothesis. Afterwards, additional mediation analyses using Hayes’ PROCESS macro were run to further investigate if the relation between narrative coherence and emotionalwell-being was mediated via perceived social support. An alpha level of .05 was set for all analyses.

Results

Descriptives

In , the descriptive statistics, including the minimum scores, maximum scores, means and standard deviations for all variables at T1 and T2 are presented. Paired sample t-tests indicated that scores changed over the two-year time period for most variables. Total narrative coherence, as well as the coherence of positive but not negative narratives, increased from T1 to T2. At T1, negative narratives were more coherent than positive narratives, t(197) = 2.17, p = .03, however at T2 there was no difference, t(197) = 0.18, p = .86. These results were followed-up with exploratory analyses to investigate if the change in coherence was related to the event type (see Supplementary Material 2). Furthermore, emotional well-being and perceived social support were significantly lower at T2, during the midst of the pandemic, as compared to T1.

Table 1. Descriptives at T1 and T2.

Pearson correlations among narrative coherence, perceived social support and emotional well-being are presented in . Both at T1 and at T2, emotional well-being was significantly positively associated with perceived social support. The measures of narrative coherence were mostly unrelated to well-being and social support at both timepoints, however; at T1, the coherence of positive narratives was significantly positively associated with emotional well-being. The narrative coherence scores, as well as the emotional and social variables showed significant associations of a medium magnitude over the two-year time span, indicating moderate stability over time.

Table 2. Pearson correlations between narrative coherence, perceived social support and emotional well-being.

Regression analyses

Prospective regression analyses (1a, 2a; ) were run to investigate if narrative coherence could predict relative changes in emotional well-being over a 2-year time span. Additionally, regression analyses (1b, 2b) were run in which perceived social support was added to the model, in order to test the hypothesised prospective mediations. In series 1a, total narrative coherence was inserted as a predictor, but was found not to be a significant predictor of changes in emotional well-being over time. The addition of perceived social support as a predictor in series 1b caused a significant improvement in the total explained variance, with an R2change of .07. Perceived social support, but not total narrative coherence, was a significant positive predictor of emotional well-being at T2, again after controlling for emotional well-being at T1.

Table 3. Prospective regression analyses predicting emotional well-being at T2.

In series 2a, the coherence of positive and negative narratives were inserted as predictors. The coherence of positive but not negative narratives at T1 was observed to significantly positively predict emotional well-being at T2, after controlling for emotional well-being at T1. The addition of perceived social support in series 2b caused a significant improvement in the total explained variance, with an R2change of .06. Perceived social support was observed to be a significant positive predictor of relative increases in emotional well-being, but also positive narrative coherence remained a significant positive predictor, although to a lesser extent than in series 2a. This suggests that the feeling of being socially supported partially mediated the prospective relation between the coherence of positive narratives and emotional well-being.

Additional mediation analyses

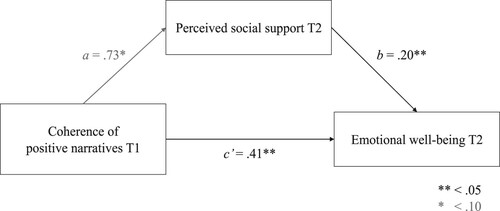

Additionally, a mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro 3.4.1 in SPSS (Hayes, Citation2013) was conducted to further investigate whether the relationship between positive narrative coherence at T1 (predictor) and emotional well-being at T2 (outcome) was mediated by perceived social support at T2 (mediator). As illustrated in , there was a positive relationship between the predictor and the outcome variable, when controlling for the mediator, b = .41, t(196) = 2.01, p = .045. Subsequently, the relation between the predictor and the mediator was also positive b = .73, t(196) = 1.84, p = .067, but did just not reach .05 significance levels.Footnote2 Finally, the mediator did significantly predict the outcome variable, b = .20, t(196) = 5.28, p < .001. In other words, there was a significant positive relation between the coherence of narratives about positive events at T1 and emotional well-being in a stressful time period two years later, of which 34% was mediated through perceived social support experienced at T2 (IE = .14).

Figure 1. The association between the coherence of positive narratives at T1 and emotional well-being at T2, partially mediated by perceived social support at T2.

Note: The path coefficients (a, b, c′) that represent the strength of the associations are estimated by unstandardised regression coefficients.

Discussion

In the present study, baseline narrative coherence was examined as a predictor of emotional well-being two years later, in the midst of the stressful COVID-19 pandemic in Belgium. Individuals who were more coherent about positive autobiographical experiences unrelated to the COVID-19 pandemic, reported relatively higher emotional well-being during the stressful circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic two years afterwards. Furthermore, individuals who were more coherent at baseline also reported relative increases in perceived social support two years afterwards, even when social isolation measures were strictly implemented.

Given the descriptive results indicating a sample-wide decrease in emotional well-being and perceived social support from T1 to T2, our results can likely be interpreted as narrative coherence predicting a relatively less severe decrease in emotional well-being and perceived support during the pandemic. Thus, individuals who were more narratively coherent two years prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, were generally less negatively affected in their emotional well-being and in their feeling of being socially supported during the stressful and isolated times of the pandemic.

Our data were, to a certain extent, in line with the expected mediation model, in which the coherence of positive narratives predicted emotional well-being two years later, and this prediction was significantly better when adding in social support to the model. In other words, individuals who were able to narrate coherently about positive personal experiences that were unrelated to the future stressful events, experienced relatively better emotional well-being in the stressful time period two years later and this may be partially due to their coherent narration evoking more supportive social reactions over time.

However, since additional mediation analyses indicated that the relation between the coherence of positive narratives was only borderline predictive of relative changes in social support over the two-year time window, these findings need to be interpreted with caution. Likely, the strict social isolation measures during the pandemic hindered individuals in receiving the social support that they would normally. Therefore, the relation between narrative coherence and social support might have been weaker in this study than has been observed previously. Prior longitudinal research, although over a shorter time interval of 5 months (Vanaken et al., submitted), as well as prior experimental research (Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020; Vanaken et al., Citation2020a) provides convincing empirical evidence for the idea that narrative coherence predicts and may even lead to more social support.

Our findings on the event valence of the narratives are in line with prior research on the interplay between emotion, language and autobiographical memory (Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020; Vanaken et al., Citation2020a). Previously, it has been observed that incoherence in positive event narratives was reacted to significantly more negatively by listeners compared to coherently narrated positive events (Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020). Incoherence for negative event narratives, by contrast, did evoke social reactions that were not significantly different from the reactions that followed coherent negative event narratives. It seems that listeners react more negatively when narratives of positive events are incoherently told than when narratives of negative events are incoherently told. We suggest that listeners may be more tolerant towards incoherent narrators when they are talking about a negative life event, since they might assume that incoherence is inherent to the cognitive-emotional processing of the event, or that the individual is still in the act of creating meaning out of the event. Research findings suggest that negative emotional content, and especially traumatic content, can disturb the coherence of autobiographical memories (Bisby et al., Citation2018; Brewin, Citation2001; Brewin et al., Citation1996; Tuval-Mashiach et al., Citation2004).

Our results can also be interpreted in the context of literature on interpersonal and social emotion regulation. It is suggested that listeners could be more habituated towards incoherent negative stories, since the help of loved ones is often sought after when going through a difficult event: for compassion reasons (Duprez et al., Citation2015) or in order to co-construct a coherent narrative (Fivush & Sales, Citation2006; Pasupathi, Citation2001; Pasupathi & Billitteri, Citation2015). Hence, there might be fewer negative social reactions when the level of coherence is lower in negative stories, compared to in positive stories.

In addition, our findings can be understood within the literature on emotional sharing and the motivations for sharing positive event experiences. Mainly positive experiences are shared with others to develop social bonds, as well as to maintain or improve them. In contrast, negative event experiences are often shared for ventilation or compassion purposes (Duprez et al., Citation2015). Sharing positive event memories, and the concomitant positive emotions, may lead to capitalisation, a term created by Langston (Citation1994). Communicating positive emotion with others through sharing narratives may lead to the enhancement of positive affect far beyond the actual positive effect of the event. Narrating these events coherently may allow both teller and listener to better understand and capitalise on the positive emotion in the act of sharing.

However, because incoherent narratives are more difficult to understand, the positive benefits to teller and listener may be attenuated. Indeed, people report that the sharing of positive events serves social functions, and that socially shared memories are dominated by positive emotion (Alea et al., Citation2013; McLean & Lilgendahl, Citation2008; Rasmussen & Berntsen, Citation2009). The positive response of others increases feelings of interpersonal closeness and intimacy, thereby enhancing social integration and relationship satisfaction (Gable et al., Citation2004; Reis et al., Citation2010). However, when narration is incoherent in positive narratives, positive social reinforcement could decline (Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020), reducing feelings of belonging to a supportive social network, which yields severe implications for emotional well-being in the long run (Alea & Bluck, Citation2003; Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Coyne, Citation1976; Harandi et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the incoherent narration of positive experiences in particular might be detrimental to the individual’s well-being, via direct (no capitalisation) as well as via indirect (no social integration) pathways.

Perhaps most notable, our findings replicate and extend the results of Vanderveren et al. (Citation2020b), by showing that coherence assessed prior to adversity in an unrelated narrative, can predict future emotional adjustment to adversity. In other words, results from this study confirm the idea that coherence can be conceptualised as a general skill (i.e. about narratives of all kinds of autobiographical experiences) that does not only indicate the adaptive processing of a specific traumatic event, but also more broadly reflects and predicts the ability to create coherence out of emotionally challenging experiences, thus facilitating emotional well-being.

Furthermore, this conceptualisation of coherence as a broader cognitive-developmental skill is supported by our descriptive results indicating a moderate stability of coherence over time. In part, coherence is likely to reflect a stable narrative style, that is based on, for instance, the individual’s cognitive abilities/skills (modest relation to general verbal abilities and memory retrieval abilities: Reese et al., Citation2011; Williams et al., Citation2007), and his/her social learning history (mother–child reminiscing: Fivush et al., Citation2006). Nonetheless, as the moderate (not high) stability scores indicate, coherence is not fixed within the individual. It also reflects variable elements that include, for example, the individual’s developmental period (coherence increased in this study over time in a group of emergent adults and the increase was not dependent on repetition of the same event, see also literature on cognitive maturation: Bohn & Berntsen, Citation2008; Köber et al., Citation2015; Reese et al., Citation2011), the event-processing time (coherence was higher for events that were concluded compared to ongoing events, see also Fivush et al., Citation2017; Waters et al., Citation2019), particular event characteristics (valence: coherence is often higher for narratives about negative events, see also: Vanderveren et al., Citation2019; event type: Banks & Salmon, Citation2013), and specific characteristics of the social context (listener’s behaviour, social reinforcement: Bavelas et al., Citation2000; Pasupathi, Citation2001; Pasupathi & Rich, Citation2005). Summarised, this study provides support for the idea that there is a combination of an intra-individual stability as well as variability component to coherence, rather than coherence being either a characteristic of only the specific event or only the individual (Adler et al., Citation2018; Fivush et al., Citation2017; McLean et al., Citation2017; Pasupathi et al., Citation2020; Waters et al., Citation2019).

In addition, our study demonstrates practical relevance by showing how narrative coherence could possibly be a resilience factor in coping with a stressor like the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, this study had some limitations. First, even though our findings do point to a certain direction of the relation between coherence, perceived social support and emotional adjustment, no causal interpretations can be drawn from this longitudinal design. The absence of a control group that did not experience the stressful event is thus to be considered as a limitation, since it challenges the interpretation that coherence might be a protective factor against stressful experiences and favours the interpretation that coherence might be an enhancement factor for positive emotion, even when difficult circumstances arise. Still, the work of Vanderveren et al. (Citation2020b), provides preliminary evidence that coherence could be a protective factor against the impact of negative life experiences on emotional adjustment.

Future experimental work is recommended to further investigate the causal relationship between narrative coherence and emotional responding, as well as to uncover different underlying mechanisms. In that sense, one interesting route would be to develop an experimental form of training to investigate whether coherence can be improved, and if so, whether this improvement brings about increased emotional and social adjustment. If coherence is an enhancing factor for positive emotion or possibly a protective factor against negative emotion, we would not have to wait until after a traumatic event has occurred to offer people therapeutic assistance. Rather, we could have a more preventative approach to training people in becoming more coherent in general, especially those in vulnerable positions, to protect their well-being against possible future adversity.

A second limitation concerns the fact that, although the focus of this study was on perceived social support as a possible explanation for the relation between coherence and well-being, this explanation is not mutually exclusive with other candidate mediators. Until now, research on candidate mechanisms has predominantly been stemming from clinical and cognitive perspectives, suggesting several possible mediators, like emotion regulation, meaning making, working memory, rumination, avoidance etc. (Boals et al., Citation2011; Klein & Boals, Citation2001; Main, Citation2000; Schank & Abelson, Citation1995; Vanderveren et al., Citation2020a). Future studies could examine this question more fully and create a broader picture on how and why coherence and well-being are related.

Third, in this study, we have focused on the relation between narrative coherence and emotional adjustment. However, other properties of narratives have been the topic of investigation in previous research, ranging from motivational and affective variables (e.g. agency, communion, emotional elaboration, redemption, resolution: Adler, Citation2012; Adler & Poulin, Citation2009; Bauer & McAdams, Citation2010; McAdams, Citation2006), to variables focused on meaning-making (e.g. closure, explorative processing, personal growth: Cox, Citation2015; Graci & Fivush, Citation2017; Pals, Citation2006; Waters et al., Citation2013). To date, the literature is quite mixed about what aspects of narratives might be especially relevant in relation to mental health (Adler, Citation2012; Adler et al., Citation2016; Booker et al., Citation2020; Cox, Citation2015; Cox & McAdams, Citation2014; McLean et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it would be useful for future research to consider (dis)similarities between various aspects of narratives and their possibly differential relation to emotional adjustment.

A final limitation of this study concerns the homogeneity of our sample, since most participants were young, white, female, Flemish psychology students. Both narrative constructions, as well as social interactions are gender-, and culture-dependent (Fivush & Nelson, Citation2004; Grysman & Hudson, Citation2013). Since in this study, our sample of men was insufficiently large to run independent analyses on gender, future research is recommended to use a more gender-balanced sample. Furthermore, particularly with regards to the COVID-19 situation, it would also be important to include sufficiently diverse and large samples in future research, in order to be able to generalise the results (London & Kimmelman, Citation2020).

In sum, in this longitudinal study, the coherence of positive narratives was significantly predictive of a relative increase in emotional adjustment two years later during the stressful times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the relation between narrative coherence and positive emotional responding was partially explained by perceived social support. It is suggested that individuals who are generally better able to construct coherent narratives, are more likely to report higher levels of emotional well-being during stressful times, maybe because their coherent narration enables them to evoke more supportive social reactions from their environment. Our findings suggest that narrative coherence can be an enhancement factor for adaptive emotional and social coping with stressful situations. This study demonstrates the importance of researching cognition (narrative coherence) and emotion (well-being) to shed light on pressing societal matters such as the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary_Material

Download Zip (80.3 KB)Data availability statement

Before conducting the second measurement, our key variables, questions and hypotheses were pre-registered on AsPredicted http://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=nc88fs.

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework (OSF): https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BNF9K

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Note that the data of the first wave in this study are part of a larger data set used in Vanaken et al. (submitted). In that respective study, we also used the Dutch version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21: Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995; Dutch translation: De Beurs et al., Citation2001) to investigate symptoms of internalizing psychopathology, and the Social Support List –Negative Interactions (SSL-N), to assess perceived negative social interactions (Van Sonderen, Citation2012). However, since we had no a priori separate hypotheses about these two questionnaires for this study, these questionnaires were not included in our analyses here (Vanaken et al., Citation2021).

2 Using non-parametric bootstrapping procedures, the indirect relation was found to be statistically significant between the 5th and 95th percentile, 90% CI [.0148–.2813]. In sum, the relation between the coherence of positive narratives at T1 and emotional well-being at T2 was partially mediated by perceived social support at T2 at a significance level of = .10.

References

- Adler, J. M. (2012). Living into the story: Agency and coherence in a longitudinal study of narrative identity development and mental health over the course of psychotherapy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(2), 367–389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025289

- Adler, J. M., Lodi-Smith, J., Philippe, F. L., & Houle, I. (2016). The incremental validity of narrative identity in predicting well-being: A review of the field and recommendations for the future. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20(2), 142–175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868315585068

- Adler, J. M., & Poulin, M. (2009). The political is personal: Narrating 9/11 and psychological well-being. Journal of Personality, 77(4), 903–932. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00569.x

- Adler, J. M., Waters, T. E. A., Poh, J., & Seitz, S. (2018). The nature of narrative coherence: An empirical approach. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 30–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.01.001

- Alea, N., Arneaud, M. J., & Ali, S. (2013). The quality of self, social, and directive memories: Are there adult age group differences? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 37(5), 395–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025413484244

- Alea, N., & Bluck, S. (2003). Why are you telling me that? A conceptual model of the social function of autobiographical memory. Memory (Hove, England), 11(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/741938207

- Baerger, D. R., & McAdams, D. P. (1999). Life story coherence and its relation to psychological well- being. Narrative Inquiry, 9(1), 69–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.9.1.05bae

- Baker-Ward, L., Eaton, K. L., & Banks, J. B. (2005). Young soccer players reports of a tournament win or loss: Different emotions, different narratives. Journal of Cognition and Development, 6(4), 507–527. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327647jcd0604_4

- Banks, M. V., & Salmon, K. (2013). Reasoning about the self in positive and negative ways: Relationship to psychological functioning in young adulthood. Memory (Hove, England), 21(1), 10–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.707213

- Bauer, J. J., & McAdams, D. P. (2010). Eudaimonic growth: Narrative growth goals predict increases in ego development and subjective well-being 3 years later. Developmental Psychology, 46(4), 761–772. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019654

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong. Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human emotion. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Bavelas, J. B., Coates, L., & Johnson, T. (2000). Listeners as co-narrators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 941–952. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.941

- Bisby, J. A., Horner, A. J., Bush, D., & Burgess, N. (2018). Negative emotional content disrupts the coherence of episodic memories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000356

- Boals, A., Banks, J. B., Hathaway, L. M., & Schuettler, D. (2011). Coping with stressful events: Use of cognitive words in stressful narratives and the meaning-making process. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(4), 378–403. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2011.30.4.378

- Bohn, A., & Berntsen, D. (2008). Life story development in childhood: The development of life story abilities and the acquisition of cultural life scripts from late middle childhood to adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 44(4), 1135–1147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1135

- Booker, J. A., Fivush, R., Graci, M. E., Heitz, H., Hudak, L. A., Jovanovic, T., Rothbaumg, B. O., & Stevens, J. S. (2020). Longitudinal changes in trauma narratives over the first year and associations with coping and mental health. Journal of Affective Disorders, 272, 116–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.009

- Brewin, C. R. (2001). Memory processes in post-traumatic stress disorder. International Review of Psychiatry, 13(3), 159–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260120074019

- Brewin, C. R., Dalgleish, T., & Joseph, S. (1996). A dual representation theory of post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Review, 103(4), 670–686. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.103.4.670

- Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

- Burnell, K., Coleman, P., & Hunt, N. (2010). Coping with traumatic memories: Second world War veterans’ experiences of social support in relation to the narrative coherence of war memories. Ageing and Society, 30(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X0999016X

- Cox, K. (2015). Meaning making in the life story, and not coherence or vividness, predicts well-being up to 3 years later: Evidence from high point and low point stories. Identity, 15(4), 241–262. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2015.1089508

- Cox, K., & McAdams, D. P. (2014). Meaning making during high and low point life story episodes predicts emotion regulation two years later: How the past informs the future. Journal of Research in Personality, 50, 66–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.03.004

- Coyne, J. C. (1976). Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85(2), 186–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.85.2.186

- De Beurs, E., Van Dyck, R., Marquenie, L. A., Lange, A., & Blonk, R. W. B. (2001). De DASS: Een vragenlijst voor het meten van depressie, angst en stress [The DASS: A questionnaire for the measurement of depression, anxiety, and stress]. Gedragstherapie, 34(1), 35–53.

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_12

- Duprez, C., Christophe, V., Rimé, B., Congard, A., & Antoine, P. (2015). Motives for the social sharing of an emotional experience. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 32(6), 757–787. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514548393

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Fivush, R., Berlin, L. J., McDermott Sales, J., Mennuti-Washburn, J., & Cassidy, J. (2003). Functions of parent-child reminiscing about emotionally negative events. Memory (Hove, England), 11(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/741938209

- Fivush, R., Booker, J. A., & Graci, M. E. (2017). Ongoing narrative meaning-making within events and across the life span. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 37(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0276236617733824

- Fivush, R., Haden, C. A., & Reese, E. (2006). Elaborating on elaborations: The role of maternal reminiscing style in cognitive and socioemotional development. Child Development, 77(6), 1568–1588. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00960.x

- Fivush, R., & Nelson, K. (2004). Culture and language in the emergence of autobiographical memory. Psychological Science, 15(9), 573–577. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00722.x

- Fivush, R., & Sales, J. M. (2006). Coping, attachment, and mother–child reminiscing about stressful events. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52(1), 125–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2006.0003

- Fivush, R., Sales, J., & Bohanek, J. G. (2008). Meaning making in mothers’ and children's narratives of emotional events. Memory (Hove, England), 16(6), 579–594. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210802150681

- Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E. A., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 228–245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228

- Graci, M. E., & Fivush, R. (2017). Narrative meaning making, attachment, and psychological growth and stress. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34(4), 486–509. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407516644066

- Grysman, A., & Hudson, J. A. (2013). Gender differences in autobiographical memory: Developmental and methodological considerations. Developmental Review, 33(3), 239–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2013.07.004

- Habermas, T., & Bluck, S. (2000). Getting a life: The emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 748–769. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748

- Habermas, T., & de Silveira, C. (2008). The development of global coherence in life narratives across adolescence: Temporal, causal, and thematic aspects. Developmental Psychology, 44(3), 707–721. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.707

- Habermas, T., & Reese, E. (2015). Getting a life takes time: The development of the life story in adolescence, its precursors and consequences. Human Development, 58(3), 172–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000437245

- Harandi, F. T., Taghinasab, M. M., & Nayeri, D. T. (2017). The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electronic Physician, 9(9), 5212–5222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19082/5212

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Methodology in the social sciences. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Klein, K., & Boals, A. (2001). Expressive writing can increase working memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(3), 520–533. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.3.520

- Köber, C., Schmiedek, F., & Habermas, T. (2015). Characterizing lifespan development of three aspects of coherence in life narratives: A cohort-sequential study. Developmental Psychology, 51(2), 260–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038668

- Langston, C. A. (1994). Capitalizing on and coping with daily-life events: Expressive responses to positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1112–1125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1112

- London, A. J., & Kimmelman, J. (2020). Against pandemic research exceptionalism. Science, 368(6490), 476–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc1731

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation.

- Main, M. (2000). The organized categories of infant, child, and adult attachment: Flexible vs. Inflexible attention under attachment- related stress. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 48(4), 1055–1096. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/00030651000480041801

- McAdams, D. P. (2006). The redemptive self: Stories Americans live by (Rev. And expanded ed.). Oxford University Press.

- McLean, K. C., & Lilgendahl, J. P. (2008). Why recall our highs and lows: Relations between memory functions, age, and well-being. Memory (Hove, England), 16(7), 751–762. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210802215385

- McLean, K. C., Pasupathi, M., Greenhoot, A. F., & Fivush, R. (2017). Does intra-individual variability in narration matter and for what? Journal of Research in Personality, 69, 55–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.04.003

- McLean, K. C., Syed, M., Pasupathi, M., Adler, J. M., Dunlop, W. L., Drustrup, D., Fivush, R., Graci, M. E., Lilgendahl, J. P., Lodi-Smith, J., McAdams, D. P., & McCoy, T. P. (2019). The empirical structure of narrative identity: The initial Big three. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000247

- Ozbay, F., Johnson, D. C., Dimoulas, E., Morgan, C. A., Charney, D., & Southwick, S. (2007). Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa.: Township)), 4(5), 35–40.

- Pals, J. L. (2006). Narrative identity processing of difficult life experiences: Pathways of personality development and positive self-transformation in adulthood. Journal of Personality, 74(4), 1079–1110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00403.x

- Pasupathi, M. (2001). The social construction of the personal past and its implications for adult development. Psychological Bulletin, 127(5), 651–672. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.5.651

- Pasupathi, M., & Billitteri, J. (2015). Being and becoming through being heard: Listener effects on stories and selves. International Journal of Listening, 29(2), 67–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.2015.1029363

- Pasupathi, M., Fivush, R., Greenhoot, A., & McLean, K. C. (2020). Intra-individual variability in narrative identity: Complexities, garden paths, and untapped research potential. European Journal of Personality, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/tbd2e

- Pasupathi, M., & Rich, B. (2005). Inattentive listening undermines self-verification in personal storytelling. Journal of Personality, 73(4), 1051–1086. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00338.x

- Rasmussen, A. S., & Berntsen, D. (2009). Emotional valence and the functions. Memory & Cognition, 37(4), 477–492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.37.4.477

- Reese, E., Haden, C. A., Baker-Ward, L., Bauer, P., Fivush, R., & Ornstein, P. A. (2011). Coherence of Personal narratives across the lifespan: A multidimensional model and Coding method. Journal of Cognition and Development, 12(4), 424–462. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2011.587854

- Reis, H. T., Smith, S. M., Carmichael, C. L., Caprariello, P. A., Tsai, F. F., Rodrigues, A., & Maniaci, M. R. (2010). Are you happy for me? How sharing positive events with others provides personal and interpersonal benefits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(2), 311–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018344

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

- Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (1995). Knowledge and memory: The real story. In R. S. Wyer Jr. (Ed.), Advances in social cognition, Vol. 8. Knowledge and memory: The real story (pp. 1–85). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Tuval-Mashiach, R., Freedman, S., Bargai, N., Boker, R., Hadar, H., & Shalev, A. Y. (2004). Coping with trauma: Narrative and cognitive perspectives. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 67(3), 280–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.67.3.280.48977

- Vanaken, L., Bijttebier, P., & Hermans, D. (2020a). I like you better when you are coherent. Narrating autobiographical memories in a coherent manner has a positive impact on listeners’ social evaluations. PloS one, 15(4), e0232214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232214

- Vanaken, L., Bijttebier, P., Robyn, F., & Hermans, D. (2021). Narrating to belong: An investigation of the concurrent and longitudinal associations between narrative coherence and mental health mediated by social support (Manuscript submitted for publication).

- Vanaken, L., & Hermans, D. (2020). Be coherent and become heard. The multidimensional impact of narrative coherence on listeners’ social responses. Memory & Cognition, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-020-01092-8

- Vanaken, L., Scheveneels, S., Belmans, E., & Hermans, D. (2020b). Validation of the impact of event Scale With modifications for COVID-19 (IES-COVID19). Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 738. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00738

- Vanderveren, E., Bijttebier, P., & Hermans, D. (2019). Autobiographical memory coherence and specificity: Examining their reciprocal relation and their associations with internalizing symptoms and rumination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 116, 30–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.02.003

- Vanderveren, E., Bijttebier, P., & Hermans, D. (2020a). Autobiographical memory coherence in emotional disorders: The role of rumination, cognitive avoidance, executive functioning, and meaning making. PloS one, 15, e0231862. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231862

- Vanderveren, E., Bijttebier, P., & Hermans, D. (2020b). Can autobiographical memory coherence buffer the impact of negative life experiences? A prospective study. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, 30(3), 211–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbct.2020.05.001

- Van Egmond, M., & Hanke, K. (n.d). Flourishing scale.

- Van Sonderen, E. (2012). Het meten van sociale steun met de Sociale Steun Lijst - interacties (SSL-I) en Sociale Steun Lijst - discrepanties (SSL-D): een handleiding. Tweede herziene druk. UMCG / Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Research Institute SHARE.

- Waters, T. E. A., & Fivush, R. (2015). Relations between narrative coherence, identity, and psychological well-being in emerging adulthood. Journal of Personality, 83(4), 441–451. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12120

- Waters, T. E. A., Köber, C., Raby, K. L., Habermas, T., & Fivush, R. (2019). Consistency and stability of narrative coherence: An examination of personal narrative as a domain of adult personality. Journal of Personality, 87(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12377

- Waters, T. E. A., Shallcross, J. F., & Fivush, R. (2013). The many facets of meaning-making: Comparing multiple measures of meaning making and their relations to psychological distress. Memory (Hove, England), 21(1), 111–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.705300

- Williams, J. M. G., Barnhofer, T., Crane, C., Herman, D., Raes, F., Watkins, E., & Dalgleish, T. (2007). Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 122–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122