?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

When individuals cannot make up their mind, they sometimes use a random decision-making aid such as a coin to make a decision. This aid may also elicit affective reactions: A person flipping a coin may (dis)like the outcome, and thus decide according to this feeling. We refer to this process as catalysing decisions and to the aid as catalyst. We investigate whether using a catalyst may not only elicit affect but also result in more affect-based decision making. We used different online studies that examine affect-driven decisions by investigating scope insensitivity (indirect behavioural measure) and self-reported weight given to feelings versus reasons in hypothetical donation decisions. Study 1a showed that a catalyst (a lottery wheel) lead to more scope insensitive (i.e. affect-driven) donations. Study 1b included several changes and did not replicate these results. Study 2 (preregistered) examined scope insensitivity but did not replicate previous results; Study 3 (preregistered) looked at the weight given to feelings versus reason. Although catalyst (compared to control) participants descriptively reported relying more on feelings, this difference did not reach significance. In contrast to lay beliefs, results do not indicate support for the hypothesis that using a catalyst results in more affect-based hypothetical donation decisions.

Individuals are faced with many decisions every day. Some are clear-cut, but for others, individuals need to consider many alternatives and take their time to think through each option. To support decision-making, individuals sometimes use aids or procedures that produce random outcomes, such as a coin toss or games like rock-paper-scissors. For instance, Francis Pettygrove and Asa Lovejoy once tossed a one-cent coin to decide on the name of a site, now called Portland, Oregon. In this case, the coin’s outcome determined the decision (Orloff, Citation2019). Yet, when the coin flip is not used as a fair means to end a discussion between two parties but for private decisions, individuals do not always end up following the aid’s suggestion. For instance, in one of our studies, a participant described being undecided about whether or not to attend a party. She decided to flip a coin, and the coin suggested going to the party. The participant then described having an affective reaction – she strongly disliked the outcome – and suddenly knew that she did not want to go. Apparently, our participant was considering both options before (otherwise she would not have needed the help of a random decision-making aid). However, after using the aid, she suddenly knew what she wanted – which was the opposite of what the coin flip suggested. We refer to this process as catalysing decisions and to the aid as a catalyst, as it causes important changes in the decision-making process (Cambridge University Press, Citationn.d.). This manuscript aims to investigate the phenomenon of catalysing decisions to better understand what happens when individuals use a random decision-making aid to make a decision, in particular whether a catalyst may increase affect-based decisions.

So far, there is little research investigating the effects of random decision-making aids. Some research has investigated the willingness to use coin flips (e.g. Keren & Teigen, Citation2010) and how this willingness may depend on individual or situational cues such as the decision’s importance (Keren & Teigen, Citation2010), individuals’ indecisiveness or perceived indifference (Dwenger et al., Citation2019), or specific topics such as a prosocial requests (Lin & Reich, Citation2018) and moral dilemmas (Gordon-Hecker et al., Citation2017; Gordon-Hecker & Olivola, Citation2019). Other research has also shown that when studying the use of random decision-making aids (such as a coin flip), the assignment of one choice option to the prominently labelled cue (e.g. heads) may provide information about individuals’ preferences for this option (Morvinski & Amir, Citation2018). Further research has investigated the impact of coin flips on choice behaviour in moral decisions (Batson et al., Citation1997), donation behaviour (Zhang & Zhong, Citationn.d.), and importantly on choice and well-being in personal decisions (Levitt, Citation2020). Most examples, however, study the coin flip as a decider, meaning that its suggestion should be considered as binding. In contrast, little empirical research grants insight into situations in which a coin flip or other decision-making aid does not determine the decision, but elicits an affective reaction that may guide subsequent behaviour (see Douneva et al., Citation2019; Jaffé et al., Citation2019; Jaffé & Greifeneder, Citation2021). This lack of research is surprising given the ease with which many individuals relate to the catalysing phenomenon. Our manuscript suggests a critical step forward to overcome this gap and to better understand the impact of decision-making aids on individuals’ judgments and decisions.

Theoretical considerations on the catalysing phenomenon

Let us go back to the initial example of a participant flipping a coin to decide whether or not to attend a party. She flipped a coin and the outcome suggested to go out. However, when she looked at the outcome, she presumably felt that she disliked the suggestion and decided to stay home instead. The coin functioned as a catalyst and aided the decision-making process.

On the level of psychological processes, we argue that flipping a coin and looking at the outcome renders the decision quasi-factual, that is, as if decided. Out of all possible outcomes, a choice has been made, which is not binding, but nevertheless can feel very real and close. As a result of this reduction in hypotheticality, and therefore, psychological distance (Liberman & Trope, Citation2008; Trope & Liberman, Citation2010), decision options may be imagined more vividly and with more detail, and therefore, elicit stronger affective reactions. For instance, prior research has shown that closeness leads to stronger affective reactions when reading an embarrassing self-disclosure (Williams & Bargh, Citation2008). Addressing the same notion from the opposite perspective (distance leads to less vividness), Bandura (Citation1999) points out that individuals distance themselves from atrocities or other severe actions by reducing vividness, for example, by relying on euphemisms or dehumanising measures.

Consistent with the notion that a random decision aid may reduce psychological distance, thereby increasing vividness and affective reactions, prior research on consumer choices has documented that flipping a coin or rolling a die and then receiving a suggestion leads to stronger feelings of satisfaction/dissatisfaction (Jaffé et al., Citation2019). Stronger affect, in turn, is likely to be more salient and thus stands a higher chance of influencing judgment and decision making (Albarracín & Kumkale, Citation2003; Loewenstein & Lerner, Citation2003; Raghubir & Menon, Citation2005). Generally, findings suggest that feelings are used in decision-making and may even constitute a critical ingredient (Bechara et al., Citation1997; Clore, Citation1994; Clore et al., Citation2001; Kahneman, Citation2011; Schwarz, Citation2012), particularly when they are salient (Albarracín & Kumkale, Citation2003; Pham, Citation1998; Exp. 1). The feeling-as-information account, for example, holds that feelings, just like facts and figures, can be used as information to make decisions (e.g. Pham, Citation2008; Schwarz et al., Citation1990). For instance, individuals might ask themselves how-do-I-feel-about-it? (similar to the situation where one assesses one’s own satisfaction with the coin flip’s outcome) and rely on this feeling to decide (I feel so good about the decision object, I seem to like it; see Pham, Citation2008).

In support of this chain of arguments, Hsee and Rottenstreich (Citation2004) showed that providing more vivid information (e.g. pictures vs. text) leads to more affect-driven judgments. Additionally, Greene and colleagues (Citation2001) argue that judgments in moral dilemmas differ depending on the potential to engage individuals’ emotions. When dilemmas are described as more “up close and personal” (p. 2106), they become more emotionally engaging. This results in faster acceptance of deontological compared to consequentialist solutions, meaning that emotional reactions lead to more deontological responses (Greene, Citation2007). Vividness may thus result in stronger reliance on feelings in judgments and decisions.Footnote1 These results suggest that random decision devices – as investigated in the present research – may not only increase vividness and strengthen feelings, but potentially increase the role of affect in the decision-making process.

To summarise, decision aids that produce random outcomes may render the decision as if it has already been made, which reduces psychological distance. As a result, feelings are strengthened and their impact on judgments is increased. Going back to our initial example, receiving a suggestion to attend the party may have rendered the decision real and vivid, which may have strengthened feelings. The experienced dislike then guided the final decision of staying at home.

Previous research has shown that using a coin flip as a catalyst strengthens feelings (Jaffé et al., Citation2019), but the downstream consequences on individuals’ decisions remain unknown and are the focus of this manuscript. Against the theoretical background, we hypothesise that participants using a coin flip as a catalyst compared to participants without a catalyst show judgment and decision-making behaviour that is indicative of reliance on feelings.

Empirical support for the catalysing phenomenon

To examine whether our theoretical considerations dovetail with individuals’ experiences and lay theories, we conducted a pretest via Prolific. In this pretest (referred to as Pretest 1), we introduced participants to a short scenario in which a fictitious person named Alex receives a cinema voucher as a birthday gift and would like to redeem it. Scrolling through the program, Alex finds two movies that sound fascinating. To make a decision, Alex decides to flip a coin but is disappointed by the outcome. Alex, therefore, decides to go to the other movie, the one the coin did not point to.

Ninety-five participants (61 female, 34 male, Mage = 37.91, SDage = 12.61) completed the study and agreed to their data being used. We asked them as how realistic they perceived the scenario to be and whether they or somebody they knew had previously experienced a similar situation. We also asked whether a coin flip might help people find out about their preferences, what they really want, and whether it may aid in listening to one’s gut feeling. All items, descriptive results, and tests against the scale mean are summarised in .

Table 1. Means and standard deviations as well as answer proportions for questions in Pretest 1.

Overall, participants found the scenario reasonable: Flipping a coin, having an emotional reaction towards the outcome, and doing the opposite of what the coin suggests were judged as realistic. Furthermore, about 83% of participants had experienced something similar themselves and 80% knew somebody who did. Participants also agreed that flipping a coin could help to find out more about one’s preferences, what one really wanted, and that it could help in listening to one’s gut feelings.

These results suggest that participants’ personal experiences and/or lay theories resemble the catalysing process described above. Individuals’ beliefs seem to reflect that using a coin flip allows for a clearer view on (gut) feelings, which may then influence subsequent decisions. All in all, these results suggest that individuals are well acquainted with the catalysing phenomenon.

The present studies

To test our hypothesis that decision aids such as coin flips increase the impact of feelings in decision processes, we build on a paradigm introduced by Hsee and Rottenstreich (Citation2004), which investigates individuals’ donation behaviour. In general, many would agree that donating money for a good cause is an admirable behaviour, but there remains some uncertainty regarding the precise amount of money that should be donated versus kept for oneself. In situations where there are no clear guidelines on what a “good” choice is, such as donations, a catalyst might be particularly effective and beneficial by strengthening feelings and increasing their impact on decision making. The realm of donations, therefore, seemed promising for our research.

Hsee and Rotenstreich’s paradigm (Citation2004) investigates donation behaviour and allows to indirectly differentiate whether a decision outcome is reached via rational calculation or affect-based valuation (see also Hsee et al., Citation2005). In particular, when asked how much a specific object is worth, individuals can look at the facts and figures describing the object (a more rational approach), but they can also assess their feelings towards the object (how-do-I-feel-about-it?). To differentiate between these two pathways, Hsee and Rottenstreich (Citation2004) asked participants how much they would donate for endangered animals (e.g. pandas). Taking the rational approach, individuals may look at the quantitative aspect or scope and consider how many pandas they are being asked to donate money for. In this case, they determine value by calculation, and four pandas should receive a larger donation than one panda. Alternatively, taking the affect-based approach, individuals may consult their feelings towards the target – how much do they like pandas? Here, they determine value by affect and may, therefore, donate a similar amount irrespective of the number of endangered animals.

Hsee and Rottenstreich (Citation2004) provided participants with either vivid (pictures) or abstract (dots) information about the number of endangered pandas. They observed valuation by affect for pictures of pandas (i.e. similar donations for four vs. one panda), but valuation by calculation when pandas were represented as dots in a table (i.e. higher donations for four vs. one panda). Our first two studies are based on this work and mimic Hsee and Rottenstreich’s (Citation2004) abstract dot condition to show valuation by calculation in the control group. Because catalysts strengthen feelings (Jaffé et al., Citation2019), we reasoned that catalyst participants are likely to show valuation by affect. As a result, catalyst participants should display a lower sensitivity towards numbers (i.e. a smaller difference between donation amounts for one vs. four animals, scope insensitivity) – just as Hsee and Rottenstreich’s (Citation2004) picture group did – compared to control participants. We, therefore, investigated donation behaviour as a proxy for whether valuation by affect or valuation by calculation took place. We report the results from two non-registered studies (Studies 1a and 1b, which were based on a preliminary study) and an additional registered Study 2 with this paradigm.

Hsee and Rottenstreich’s (Citation2004) indirect approach to study reliance on feelings is attractive as it reduces the impact of normative thoughts on the outcome measures. The downside of this indirect approach is that reliance on affect needs to be deduced from behaviour. To complement this indirect approach, we conducted an additional registered Study 3 in which participants are directly asked to what extent they based their decision on affect and/or reason. Pretest 1 (reported above) suggests that individuals can report on experiencing affective reactions when flipping the coin (see also Jaffé et al., Citation2020). We do not know, however, whether individuals think that these affective experiences have downstream consequences for their decision making. We note that this direct question harbours the downside that the indirect approach circumvents: Even if individuals think that affective experiences elicited by the coin toss have downstream consequences, they may not report these for normative reasons. But should the direct and indirect approaches result in converging support, this would be all the more compelling. We also note that it is not clear whether individuals have the capacity to accurately introspect on the impact of feelings. Prior research suggests that individuals can report on the use of feelings in judgment (Avnet et al., Citation2012; Chang & Pham, Citation2013; Inbar et al., Citation2010); other research, however, is sceptical about introspection capabilities more generally (Nisbett & Wilson, Citation1977; see also Pronin, Citation2007). The suggested Study 3 may prove of interest to this ongoing debate, too. For this Study 3, we again use donation decisions as a setting, but vary organisations instead of number of animals in need. We ask participants how they made their decision and thereby test whether individuals indicate that they relied more on feelings when using a catalyst for donation-related decisions.

Throughout all studies, we report all measures, manipulations, and exclusions.

Study 1a

Building on Hsee and Rottenstreich’s (Citation2004) abstract dot condition, we provided participants with information on four different endangered animals for which they could indicate their willingness to donate money. In the catalyst condition, we then introduced a random device – in this case, a lottery wheel. We opted for a lottery wheel instead of a coin, as the lottery wheel allows continuous and not just binary suggestions. Catalyst participants were asked to spin the lottery wheel before donating and to consider the outcome. Before running Study 1a, we conducted a preliminary study, which however, included a high proportion of participants that had psychological knowledge that might have affected the results. For reasons of transparency, we therefore, describe the preliminary study but do not draw strong conclusions from it.

Preliminary study

Method

Participants and design. The study was advertised as a study on Endangered Animals on the German platform “Forschung Erleben” which informs about recent psychological research. Forschung Erleben recruits mostly students to join their mailing list to learn about but also participate in psychological research. Members of this mailing list thus generally participate because they are interested in psychological research.

We aimed for 40 participants per cell. One hundred and seventy-three individuals participated (47 male, 124 female, 2 other; Mage = 27.74 years, SDage = 8.08). A sensitivity analysis conducted with G*Power (Faul et al., Citation2007, Citation2009) indicated that this setup (N = 173, α = .05, power = .80, correlation among repeated measures 0.5) would allow to detect minimum effect sizes of f = 0.11. Participants could participate in a lottery for online retail vouchers as compensation.

We used a 2 (condition: catalyst vs. control wheel) × 2 (scope: one vs. four endangered animals) × 4 (animals: pandas vs. dolphins vs. elephants vs. polar foxes) mixed design, with the factor animals as repeated measures. The dependent variable was the amount of money donated for the animals. As the outcome is a continuous dependent variable and not a binary one, we used a lottery wheel as a catalyst with 51 options (for possible donations between 0 and 50€).

Materials and procedure. Participants gave informed consent and learned that we were interested in donation behaviour regarding different animals. Catalyst and control wheel participants then learned about the lottery wheel as a critical ingredient of the study which they would be asked to spin before making a decision. Catalyst participants were told that the resulting number might elicit a helpful gut feeling. Wheel control participants were told that they should remember the resulting number as we would be asking them about it later on. All participants were informed that we were interested in their donation behaviour and would be asking them how much they would donate for one (four) exemplar(s) of different endangered species.

Subsequently, we asked all participants to imagine that a team from the local zoological institute discovered some exemplars of an endangered species in a remote region. Half of the participants were then offered the possibility to donate for one exemplar of this type of animal, the other half for four exemplars. Remodelling Hsee and Rottenstreich’s (Citation2004) valuation by calculation condition, the number of animals was indicated by either one or four dots in a table. Catalyst and wheel control participants then spun the wheel and learned about the outcomes. Repeating the initial instruction, catalyst participants were told that they may use this number as a recommendation and to check their gut feeling. Wheel control participants were asked to memorise the number. All participants then again saw the table with the animal type and the number of endangered animals, and were asked to indicate how much they would donate on a scale from 0€ to 50€ (in 5€ intervals, following the scale used in Hsee & Rottenstreich, Citation2004). Wheel control participants were asked to enter the number that they had memorised before in a text box.

The above sequence of events was repeated four times, once for every animal type. The first trial contained pandas, the second dolphins, the third elephants, and the fourth polar foxes. At the end of the study, wheel control participants learned how many numbers they had memorised correctly and we assessed basic demographic information (gender, age, language proficiency, and education). We further asked about actual donation behaviour for charities in general and for animals in particular during the last 12 months. Participants were thanked and offered to participate in a lottery as compensation.

Results

Five participants asked for exclusion of their data. The remaining 168 participants donated between 0 and 50€ for the different animals, with a grand mean of 19.44€ (SD = 14.81). To test the hypothesis that catalyst compared to control participants are more scope insensitive, we calculated a 2 (condition: catalyst vs. control wheel) × 2 (scope: one vs. four animals) × 4 (animals) mixed ANOVA with condition and scope as between factors and animals as a within factor. Donation behaviour was the dependent variable. We observed a significant main effect of animals, F(2.69, 441.15) = 3.49, p = .020, = .02, indicating that donation behaviour differed for different animals: Mean donations for pandas were 19.02€ (SD = 15.85), for dolphins 19.49€ (SD = 15.93), for elephants 20.71€ (SD = 16.39), and for polar foxes 18.54€ (SD = 15.30). We also observed a significant main effect of scope, F(1, 164) = 17.12, p < .001,

= .10, showing that, overall, participants donated more for four animals than for one animal, M = 23.84, SD = 16.25, versus M = 15.34, SD = 12.03; respectively. An interaction between condition and scope was observed, F(1, 164) = 11.31, p = .001,

= .07, suggesting that scope sensitivity differed between conditions. Opposing our predictions, control wheel-participants were less scope sensitive than catalyst participants: Catalyst participants donated more money for four compared to one animal, M = 29.05, SD = 16.75; M = 12.83, SD = 10.82; F(1, 164) = 27.14, p < .001,

= .14, but there was no significant difference for control wheel-participants, M = 20.26, SD = 15.04; M = 18.59, SD = 12.87; F(1, 164) = 0.31, p = .578,

= .00, respectively. All other main or interaction effects were not significant, all Fs < 1.

Further analyses and discussion. We analysed participants’ spontaneous comments about what they considered the study’s purpose to be. As described above, our sample consists of individuals interested in psychological research and 157 out of 168 participants had finished their A-levels or even completed a university degree. Next, 39.3% of our sample spontaneously mentioned some version of anchoring or numeric priming (impact of the lottery wheel on their donation behaviour) as the study’s purpose. Given that this was an open format response box, it is unclear how many more participants had similar thoughts but did not spontaneously mention these. These suspicions (even if wrong) might lead to second-order cognitions such as reactance (e.g. not wanting to follow the instructions and being especially critical of the catalyst condition) or supportive behaviour (e.g. trying to follow the instructions really well), both of which might result in a more calculation-driven approach, especially in the catalyst condition. We are, therefore, uncertain about the interpretation of these results and identify the need to investigate our research question with participants less knowledgeable about psychological research.

Study 1a

Different from the preliminary study, in Study 1a we implemented two control conditions. In one control condition, participants were also shown the lottery wheel, but were just asked to remember the suggested number (wheel control). In the other control condition, participants were not shown a lottery wheel at all (standard control). This design allowed us to test whether introducing a random device that is associated with the decision (catalyst) will lead to more affect-driven decisions about donations for endangered animals compared to having no device (standard control) or a random device that is not associated with the decision (wheel control). The original and the translated materials are accessible here: https://drive.switch.ch/index.php/s/vZZIv2secGP1ma6. Study 1a was further conducted via the platform Workhub to reduce the chances of high numbers of participants who are knowledgeable about psychological research (e.g. a student sample).

Method

Participants and design. We advertised this experiment as a study on endangered animals on the German online platform Workhub. Not knowing the effect sizes in this combination of paradigms, we aimed for 40 participants per cell. Two hundred and twenty-six individuals completed the study (139 male, 84 female, 1 other, 2 no answer; Mage = 32.76 years, SDage = 12.17). A sensitivity analysis with G*Power (Faul et al., Citation2007, Citation2009) indicated that this setup (N = 226, α = .05, power = .80, correlation among repeated measures = 0.5) allows to detect minimum effect sizes of f = 0.19. Participants took about four minutes to complete the study and received 0.60€ (approximately US$ 0.68) as compensation.

We used a 3 (condition: catalyst vs. control wheel vs. standard control) x 2 (scope: one vs. four endangered animals) × 4 (animals: pandas vs. dolphins vs. elephants vs. polar foxes) mixed design, with the factor animals as repeated measure to investigate the stability and generalisability of potential effects across different animals. The dependent variable was the amount of money participants would donate for each of the four types of animals. As the dependent variable is continuous and not binary, we used a lottery wheel as the catalyst with 51 options (referring to possible donations between 0 and 50€).

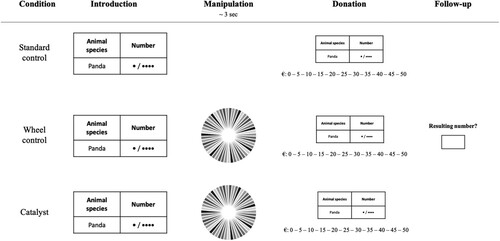

Materials and procedure. Materials were similar to the ones described in the preliminary study but additionally included the standard control condition. Standard control participants did not see a lottery wheel and simply learned that some pages might take some time to load and were asked to be patient (the loading time was fixed to the time the other groups needed to spin the lottery wheel). During the time where the lottery wheel was shown in the other conditions, standard control participants simply saw a blank screen. illustrates the different conditions.

Results

No exclusions were preregistered for Study 1a. To be consistent throughout the manuscript, however, we excluded all participants who indicated that there had been reasons to exclude their data (n = 11). The remaining 215 participants indicated donating between 0 and 50€ for the different animals, with a grand mean of 14.37€ (SD = 11.40). To test the hypothesis that catalyst compared to control participants are more scope insensitive, we calculated a 3 (condition: catalyst vs. wheel control vs. standard control) × 2 (scope: one vs. four animals) × 4 (animals) mixed ANOVA with condition and scope as between factors and animals as within factor. Donation behaviour was the dependent variable. We observed a significant main effect of animals, F(2.87, 600.62) = 2.93, p = .035, = .01, indicating that donation behaviour differed between animals (see Appendix A for further details). We also observed a significant main effect of scope, F(1, 209) = 6.30, p = .013,

= .03, showing that participants overall donated more for four animals than for one animal.

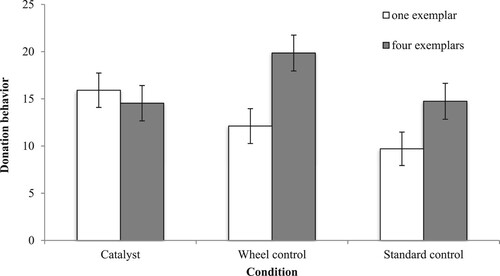

Crucially, we observed the predicted interaction between condition and scope, F(2, 209) = 3.18, p = .044, = .03, suggesting that the conditions differed in regards to scope (see ). Replicating Hsee and Rottenstreich’s (Citation2004) valuation by calculation results, both wheel control and standard control participants donated more money for four compared to one animal, F(1, 209) = 8.52, p = .004,

= .04 and F(1, 209) = 3.75, p = .054,

= .02, respectively. In contrast, catalyst participants were less scope sensitive and donated a similar amount of money irrespective of the number of endangered exemplars, F < 1. The catalyst group thus conceptually mimics Hsee and Rottenstreich’s (Citation2004) valuation by affect group. All other main or interaction effects were not significant, all Fs < 2.32.

Figure 2. Donation behaviour (in €) as a function of condition and scope (error bars reflect standard errors).

Further analyses. As the lottery wheel provides a plausible numeric suggestion, the existence of anchoring effects appears conceivable (consistent with Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1974). We had designed the study to minimise anchoring effects by fixing the outcome of the lottery wheel across conditions – that is, catalyst and wheel control participants saw the same fixed outcome (33 for pandas, 15 for dolphins, 23 for elephants, 29 for polar foxes). Second, we inspected the above-reported ANOVA from an anchoring perspective. Because standard control participants were not provided with a suggestion, they should differ in their donation behaviour from both other groups if anchoring had occurred. However, we observed a non-significant main effect of condition, F(2, 209) = 2.31, p = .102, = .02. Post-hoc comparisons with Tukey HSD revealed a non-significant difference between the catalyst and standard control group, p = .196, the catalyst and wheel control group, p = .938, and between the wheel control and standard control groups, p = .101.Footnote2 Third, our main result holds that the data does not support the assumption that catalyst participants were affected by scope, which appears incompatible with an anchoring effect explanation (but see Appendix A for further analyses).

Participants in the wheel control condition (n = 70) were asked to memorise the suggested number and to report it after deciding on their donation. Sixty participants remembered all suggested numbers correctly, nine remembered three numbers correctly, and one participant only two. Excluding participants from the analyses who did not remember all numbers correctly resulted in the same pattern of results (main effect scope: F(1, 199) = 6.04, p = .015, = .03; interaction effect scope and condition: F(2, 199) = 3.05, p = .050,

= .03).

To investigate potential effects of previous donation behaviour, we included participants’ general and animal-specific donation habits as covariates in the above-described analysis. We checked for redundancy between the covariate and the independent variables (Muller et al., Citation2008) by calculating an ANOVA with condition and scope as between factors and donation habits in general and specifically for animals as dependent variables (Yzerbyt et al., Citation2004). The analysis did not yield significant results (all Fs < 1.34), indicating no redundancy between the covariates and the independent variables. Therefore, we calculated the mixed ANOVA with condition and scope as between factors and animals as a within factor, but included general and animal-specific donation behaviour as two covariates. The main effect of animals was no longer significant, while the main effect of condition was significant, F(2, 207) = 3.36, p = .037, = .03. The main effect of scope and the interaction effect between condition and scope remained significant and effect sizes were of a similar magnitude.

Discussion

Study 1a was designed to test the hypothesis that individuals relying on catalysts use feelings to determine value. To this end, we extended Hsee and Rottenstreich’s (Citation2004) abstract dot condition in which participants determine value by calculation. We reasoned that catalyst participants would show valuation by affect even in the abstract dot condition. As a result, catalyst participants should display a lower sensitivity towards numbers (i.e. a smaller difference between donation amounts for one vs. four animals) compared to control groups. The results of Study 1a support this, as catalyst participants donated a similar amount of money irrespective of the number of endangered animals, whereas participants in both control groups were sensitive to scope and donated more money for four compared to one animal. We conclude from these results that catalysts may not only strengthen feelings (Jaffé et al., Citation2019), but that these feelings may influence decision-making.

Study 1a, however, comes with methodological challenges. Although the catalyst instructions stating that the resulting number might elicit a helpful gut feeling is consistent with our process assumption and with individuals’ lay theories, it likely increased the feeling’s salience by itself. Second, fixing the lottery wheel to certain outcomes could have made the setup less realistic and does not perfectly rule out potential anchoring effects. Study 1b was designed to overcome these challenges.

Study 1b

Study 1b is a replication and extension of Study 1a with three changes. First, as the two control groups in Study 1a showed the same pattern of results, it appeared sufficient to focus on the wheel control condition in Study 1b. Second, we aimed for a more stringent test of our hypothesis by omitting allusions to gut feelings in the catalyst instructions, so that the decision aid alone could act as a catalyst by strengthening feelings. We, therefore, changed the instructions in the catalyst group and explained that the resulting number may serve as an aid for the decision. Third, we let the lottery wheel result in a random number between 5 and 25 (±10 from the grand mean of donation behaviour in Study 1a). Each participant, therefore, saw a different number, which allows to better investigate potential anchoring effects by calculating correlations between the random suggestion and participants’ donations.

Methods

Participants and design

We advertised this experiment as a study on donations for animals on the German online platform Clickworker. One hundred and fifty-six individuals participated (83 male, 71 female, 1 other, 1 no answer; Mage = 35.13 years, SDage = 12.29). A sensitivity analysis with G*Power (Faul et al., Citation2007) showed that this sample size allowed detecting effect sizes of f = 0.21 (small to medium) with standard criteria (alpha = 0.05, power = 0.80, correlation among repeated measures 0.5). Participants took about four minutes to complete the study and received 0.60€ (approximately US$ 0.68) as compensation.

We used a 2 (condition: catalyst vs. control wheel) × 2 (scope: one vs. four endangered animals) × 4 (animals: pandas vs. dolphins vs. elephants vs. polar foxes) mixed design, with the factor animals as repeated measures. The dependent variable was the amount of money participants would donate for the animals.

Materials and procedure

The materials and procedure were identical to Study 1a, except for the three changes detailed above: There was no standard-control group, no reference to consulting gut feelings in the catalyst condition, and the outcome of the lottery wheel was not fixed but randomly ranged from 5 to 25€.

Results

One participant asked for exclusion of their data. The remaining 155 participants indicated donating between 0 and 50€ for the different animals, with a grand mean of 14.87€ (SD = 11.96). To test our hypothesis, we calculated a 2 (condition: catalyst vs. control wheel) × 2 (scope: one vs. four animals) × 4 (animals) mixed ANOVA with condition and scope as between factors and animals as a within factor. Donation amount was the dependent variable. We observed a significant main effect of animals, F(2.56, 386.60) = 5.07, p = .003, = .03, indicating that donation behaviour differed between animals.Footnote3 We also observed a significant main effect of scope, F(1, 151) = 17.94, p < .001,

= .11, showing that participants overall donated more for four (M = 18.73, SD = 12.93) animals than for one animal (M = 10.96, SD = 9.47). However, we neither found a main effect of condition, F(1, 151) = 0.03, p = .855,

= .00, nor the predicted interaction between condition and scope, F(1, 151) = 0.00, p = .952,

= .00. On several levels, the results from Study 1b, therefore, do not replicate the results from Study 1a. All other interaction effects were not significant either, all Fs < 2.18.

Further analyses

We inspected potential anchoring effects by calculating correlations between the donation for each animal and the random lottery wheel suggestion. None of the correlations were significant (r(153) = .10 to r(153) = .11, p = .229 to p = .158). This pattern held when looking at the catalyst condition only. We, therefore, do not find support for anchoring effects in this study.

Participants in the wheel control condition (n = 78) were asked to memorise the suggested number and report it after deciding on their donation. Seventy-two participants remembered all suggested numbers correctly, five remembered three numbers correctly, and one participant made four mistakes. Excluding participants from the analyses who did not remember all numbers correctly resulted in the same pattern of results (main effect scope: F(1, 145) = 16.82, p < .001, = .10; interaction effect scope and condition: F(1, 145) = 0.02, p = .880,

= .00).

Discussion

Study 1b fails to support the hypothesis that using a catalyst results in more affect-driven decisions. Instead, all participants showed donation behaviour that mirrors the valuation by calculation behaviour in the original study (Hsee & Rottenstreich, Citation2004), as participants donated more for four than for one animal. Study 1b, however, shows that anchoring does not seem to provide an explanation for the observed data pattern.

The results from Study 1b are surprising, as both Study 1a and Pretest 1-participants’ experiences and lay theories point in a different direction. This leaves us in a situation in which lay theories and one study speak for the suggested hypothesis that a catalyst increases affect-based decision making, while one other study does not. The results of both studies are interesting, as one provides support for the hypothesis that a random decision-making aid can result in affect-based decisions in the domain of donations, while the other does not offer support for people’s beliefs and lay theories.

At this point, we suggest two additional studies that will provide a well-rounded picture. Study 2 is based on the same methodological approach as Studies 1a and 1b to test the presence and stability of catalyst effects on decision making in an indirect way. Study 3 relies on a different and more direct setup to provide further information on whether individuals’ lay theories and our theoretical considerations can be empirically supported.

Study 2

When re-evaluating the setup, the attributes of the previous studies, and the changes introduced between Studies 1a and 1b, five of them appear suboptimal in retrospect. We now outline these and explain how we will design Study 2 to provide an optimised test.

First, when we designed Study 1b, we wished to avoid threats to internal validity in the catalyst introduction, and therefore, removed all allusions to gut feelings. The result was a rather abstract instruction that no longer mentioned feelings (reducing one threat to internal validity), but now may have actively hindered participants in considering the random device as an aid (creating a new threat to internal validity). The abstract description in Study 1b might have led participants to perceive the lottery wheel as a decider, and individuals are rather reluctant to use random devices in such a way (Keren & Teigen, Citation2010). In light of this, we reason that we must explain the catalyst effect so that catalyst participants understand the process, but that they will still be making the final decision themselves. While this will result in a more concrete description compared to Study 1b, it will not mention gut feelings, thus avoiding demand effects.

Second, allowing the lottery wheel to randomly suggest a number was important to test for anchoring effects, and Study 1b fulfils this purpose. One downside of this procedure is that participants receive different suggestions that might be more or less realistic, resulting in additional (error) variance. Another downside is that the suggestion of concrete numbers could activate a valuation by calculation mindset among participants. Although Study 1a yielded the hypothesised results despite this potential side effect, it is nevertheless conceivable that it works against the catalyst. Taking these considerations into account, the lottery wheel in Study 2 does not suggest an amount, but is colour-coded. In the catalyst condition, we will explain that darker colours indicate higher, whereas lighter colours indicate lower donation amounts.

Third, we initially chose a lottery wheel as a catalyst because it can provide continuous suggestions. However, a lottery wheel might be far removed from individuals’ lay theories or experiences with catalysts, which are mostly coin flips that provide discrete suggestions. Using a coin flip might, therefore, intuitively make more sense to participants and would increase our study’s ecological validity. We, therefore, vary the catalyst in Study 2 by asking half of the participants to spin the colour-coded lottery wheel and the other half to flip a coin (which in the catalyst condition will suggest donating a lot or little money). To minimise differences between type of catalyst-conditions and to provide discrete suggestions in both conditions, the lottery wheel will be fixed to display a dark colour (resembling the “donating a lot of money” suggestion by the coin) or a light colour (resembling the “donating little money” suggestion by the coin).

Fourth, reading the same scenario for four different types of animals might feel artificial and hypothetical, and might also lead to numbness regarding the animals in need, thereby hindering affective influences. We will, therefore, ask participants about only one animal, namely pandas (as in Hsee & Rottenstreich, Citation2004). We opted for pandas as they are prototypical for animal donation campaigns (e.g. WWF). We will further assess donations by using the full range of the scale between 0 and 50€, without limiting donations to a number that can be divided by 5 as in our previous studies.

Fifth, Studies 1a and 1b followed a preliminary study that we had conducted mainly among psychology students and individuals interested in psychological research. Analyses of the responses from this preliminary study revealed that about one third of the participants spontaneously associated the lottery wheel with anchoring effects, reflecting how well-known Tversky and Kahneman’s (Citation1974) findings on the anchoring heuristic using a lottery wheel are. As assumptions (even if wrong) about the study’s background and associated second-order cognitions may severely alter results, we report the preliminary study but caution about strongly interpreting the findings. Instead, we focus on Studies 1a and 1b, which were conducted with a more general sample outside of the university context. However, to ensure that previous psychological knowledge does not distort the results of the suggested Study 2, we include items to assess previous knowledge about anchoring and exclude participants that report it.

Methods

Participants and design

We advertised Study 2 as a study on endangered animals via Prolific. Based on the effect sizes from Study 1a ( = .03, i.e. d = .35), we aimed to collect data from 469 German-speaking participants residing in Germany to be able to detect small effect sizes (f = 0.15) with a power of .90 (G*Power; Faul et al., Citation2007). We increased the number of participants by 10% while keeping cell sizes balanced to account for potential dropout, participants who ask for data exclusion, or participants who need to be excluded based on the criteria described below. This resulted in an aspired sample size of 516 participants. After applying the exclusion criteria (see below), the resulting sample consists of 412 participants (213 female, 190 male, 8 non-binary, 1 other; Mage = 29.08, SD = 9.44).

We used a 2 (condition: catalyst vs. control) × 2 (scope: one vs. four endangered animals) × 2 (type of catalyst: lottery wheel vs. coin flip) between-participants design. Type of catalyst is considered a control factor as we did not expect to find differential effects for the two catalysts. The dependent variable is the amount of money participants would donate.

Materials and procedure

Materials and procedure were similar to Study 1a, except for the following changes. First, as in Study 1b, we focused on the catalyst and the wheel/coin control group. In the catalyst group, the lottery wheel or coin resulted in a discrete suggestion. In the control group, participants simply saw the lottery wheel/coin spinning. Second, we instructed participants in the catalyst group in the following way:

You will be working on one decision scenario. In this study, we present you with a lottery wheel/coin flip. Some people find it helpful to make a decision by flipping a coin, rolling a die, or spinning a lottery wheel, even if they don’t necessarily follow the suggestion – it helps them to find out what they want. Please take a moment to consider the lottery wheel’s/coin’s suggestion before you indicate your own decision, that is, how much you would be willing to donate.

These instructions were more specific than those in Study 1b and explained that the random aid’s suggestion is not binding, while at the same time refraining from any mention of gut feelings.

Consistent with the control conditions in Studies 1a and 1b, we introduced the lottery wheel/coin flip to control participants as an important component of the study and explained that some people find it easier to make a decision when being briefly distracted, for example, by counting how often the wheel turns/the coin spins. To ensure that participants in the control condition did not use the lottery wheel or coin to make a decision, they only saw the spinning device and no end result. We, therefore, did not ask control participants to remember the outcome, but to simply look at the respective device. The verbatim instructions for all conditions can be found in Appendix B.

We asked for donation intentions on a continuous scale from 0€ to 50€. Participants could choose any number between these endpoints. In line with the setup used in the original study (Hsee & Rottenstreich, Citation2004), we labelled the following points on the continuous scale: 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50€. Participants only made one donation decision in Study 2.

As minor changes, we excluded the question on mother tongue (if not German). To control for participants with knowledge about the anchoring or numerical priming phenomenon (see preliminary study), we asked participants about their naïve conceptions of the investigated research question. We further assessed whether participants had been or are currently enrolled in a university course in psychology or economics. Both questions were be placed at the questionnaire’s end.

Results

From the collected sample, we excluded participants who did not complete the study, who mentioned a reason to exclude their data (n = 2), who spontaneously named anchoring or numeric priming as the research question either verbatim or in a clear paraphrase (n = 9), or who indicated being enrolled or having completed studies in psychology or economics (n = 96). The following analyses were conducted with the remaining sample of 412 participants. Participants on average indicated that they would donate 17.09 € (SD = 13.26) for the pandas in need.

We calculated a 2 (condition: catalyst vs. control wheel) × 2 (scope: one vs. four animals) between-participants ANOVA. Hypothetical donation amount served as the dependent variable. Analyses yielded a significant main effect of condition, F(1, 408) = 6.73, p = .010, = .02, reflecting that catalyst compared to control participants would donate more, Mcatalyst = 18.84, SD = 13.84; Mcontrol = 15.44, SD = 12.49. No significant main effect of scope was found, F(1, 408) = 0.27, p = .603,

= .00, indicating that participants would not donate significantly more money for four compared to one pandas in need, Mfour = 17.46, SD = 13.15; Mone = 16.73, SD = 13.38. We did not find the predicted interaction effect, F(1, 408) = 0.79, p = .374,

= .00. Descriptively, participants in the catalyst condition were more scope sensitive than control participants, Mcatalyst&one = 17.89, SD = 13.86; Mcatalyst&four = 19.72, SD = 13.82; Mcontrol&one = 15.67, SD = 12.91; Mcontrol&four = 15.19, SD = 12.10.

We repeated this analysis separately for participants who used a lottery wheel and participants who used a coin. For participants who used a lottery wheel, results indicate a non-significant effect of condition (F(1, 201) = 0.84, p = .362, = .00), of scope (F(1, 201) = 0.00, p = .956,

= .00), and of the interaction between the two factors (F(1, 201) = 0.46, p = .500,

= .00). For participants who used a coin, results indicate a significant main effect of condition (F(1, 203) = 7.85, p = .006,

= .04), reflecting that catalyst participants compared to control participants would donate more, Mcatalyst = 19.65, SD = 14.27; Mcontrol = 14.53, SD = 10.60. We found neither a significant effect of scope (F(1, 203) = 0.57, p = .450,

= .00), nor of the interaction between the two factors (F(1, 203) = 0.15, p = .697,

= .00). Descriptive results can be found in .

Table 2. Descriptive results for Study 2.

We also investigated whether results change when including past donation behaviour as a covariate in the ANOVA. This was, however, not the case. Previous donations for animals (not donations in general) significantly explained variance in hypothetical donations in the study, F(1, 405) = 14.77, p < .001, = .04, and the main effect of condition remained stable, F(1, 405) = 6.32, p = .012,

= .02, yet both the effect of scope and the interaction were still not significant (Fs < 1).

Following the preregistered plan, we next recalculated the ANOVA analysis using a Bayesian approach with JASP which allowed us to provide more information on whether the results support the alternative hypothesis or the null hypothesis that catalyst and control groups do not differ in their donation intentions. The Bayesian ANOVA indicated a Bayes Factor10 of 0.08 when testing the full model (two main effects plus the interaction) against the null model. According to Lee and Wagenmakers (Citation2013), this indicates strong evidence for the null hypothesis.

Discussion

Study 2 was designed as a well-powered replication study to test whether using a catalyst not only results in stronger affective reactions (as observed in previous research), but also increases affect-based decision making. Based on the work by Hsee and Rottenstreich (Citation2004), we deduced the extent to which participants relied on affect when making decisions from their scope insensitivity in their donation behaviour (i.e. whether they were more likely to donate similar amounts for four compared to one animal in need). Previous studies provided mixed support for this hypothesis: In Study 1a, we found the predicted interaction (catalyst participants were more scope insensitive than control participants), indicating that catalyst participants potentially engaged in more affect-based decision making. However, results from Study 1b did not replicate this finding. Study 2 again does not yield support for the hypothesis: Catalyst participants were not more scope insensitive than control participants. This pattern remained when looking at type of catalyst separately (coin vs. lottery wheel) and when including past donation behaviour into the analysis.

The results from Study 2 further differ from the results of Studies 1a and 1b. In both previous studies, we found a significant main effect of scope, showing that in general participants would donate more for four than for one animal in need. This was not the case in Study 2. This could be a random deviation or result from the structural changes that we implemented in Study 2 (e.g. participants did not receive a concrete number as suggestion). Future research could systematically test under which conditions scope sensitivity is generally more (vs. less) likely to occur.

All in all, the indirect approach of testing whether using a catalyst increases affect-based decisions by looking at scope insensitivity in donation behaviour did not provide support for the original hypothesis.

Study 3

Studies 1a, 1b, and 2 assessed scope insensitivity to determine whether using a catalyst results in more affect-based decision-making. This indirect approach has many advantages, including reducing the impact of normative thoughts. In particular, participants might think that using a random decision aid reflects irrational behaviour, and therefore, actively do not want to allow or admit any influence (see Elster, Citation1987; Langer, Citation1975). At the same time, however, the indirect nature of this paradigm only allows to deduce reliance on feelings.

Study 3 complements this indirect test with a direct test. Pretest 1 showed that individuals report experiencing affective reactions, but it is silent on whether individuals think that these affective experiences impact their subsequent choices. This direct question of course harbours the downside that the indirect approach circumvents: Even if individuals think to themselves that affective experiences elicited by the coin toss have downstream consequences, they may not report these for normative reasons. But should the direct and indirect approaches result in converging support, this would be all the more compelling.

Study 3 was thus designed to test whether individuals have insight into the drivers of their catalyst decisions. Building on the results of Pretest 1, we here directly tested whether participants indicate that catalyst decisions are more strongly based on affect. This presupposes that individuals have the capability to introspect, which has not remained undisputed in the literature (Nisbett & Wilson, Citation1977). However, some research suggests that individuals have this insight and should be able to tell us if they relied on feelings in their decisions (Avnet et al., Citation2012; Chang & Pham, Citation2013; Inbar et al., Citation2010).

Pretest 2

Study 3 again focused on donation behaviour for animal welfare organisations. To test whether individuals report that they base their decisions more strongly on affect with versus without a catalyst, we required a decision scenario that allowed for different decision-making strategies (e.g. affect and/or reason-based decision making, see Inbar et al., Citation2010). This ensured that decisions can be more or less strongly based on affect. It should be furthermore normatively acceptable to make the decision based on both affect and reason to allow individuals to comfortably express their approach. To make sure that we met these prerequisites in our donation setup, we conducted a second pretest.

For Pretest 2, we used six fictitious animal welfare organisations and presented participants three times with a choice between two organisations each, asking to which participants would rather donate (six organisations were combined with three decisions in five different ways, resulting in 15 possible combinations of decision scenarios overall). To ensure that the study task did not cue a rational decision mode (i.e. a need to come to a precise and objective evaluation, resulting in a preference to make a rational choice; Inbar et al., Citation2010), the materials describing the welfare organisations contained minimal information only (focus, founding year, and location; see, e.g. Douneva et al., Citation2019; Study 3), but no information on the organisations’ effectiveness. Each description was accompanied by a unique fictitious logo that always included an animal depiction.

We collected data from 100 participants via Prolific. One hundred and one individuals participated in the survey. Of these, we excluded one participant who did not provide informed consent and four participants who indicated reasons to not use their data. The resulting sample consisted of 96 participants (50 male, 45 female, 1 other/no information; Mage = 33.65, SD = 11.61). Participants first made their choice to which animal welfare organisation they would prefer to donate and then indicated to what extent their decision was based on reason, and to what extent their decision was based on feelings (two 7-point Likert scales, 1 = not at all, 7 = very much, adapted from Avnet et al., Citation2012). Participants then indicated how much they would be willing to donate for the chosen organisation using a slider ranging from $0 to $50 before proceeding to the second and third decision scenario. After the third donation decision, participants were asked to describe how they had made their decisions (open text box) and how socially acceptable it was, in their opinion, to generally make a donation decision based on reason and on feelings (two 7-point Likert scales, 1 = not at all acceptable, 7 = very acceptable). Participants then answered questions about demographics and carefulness when completing the study.

Participants thought it was very socially acceptable to make donation decisions based on reason, M = 6.45, SD = 0.90, but also based on feelings, M = 6.15, SD = 1.09. Across the decision scenarios, choice proportions between the two options varied from 90:10 to 52:48. For all 15 scenarios, we find that participants on average based their decisions both on reason and feelings (all values > 4, i.e. the scale midpoint). For 14 out of 15 scenarios, we find that decisions were descriptively based more strongly on affect compared to reason, but these differences did not reach significance. The detailed summary of the results from Pretest 2 can be found in Appendix C.

The results from Pretest 2 show that the donation decision fulfils the necessary requirements for our main study: Participants base their decisions on both reason and feelings and find it socially acceptable to follow either approach when choosing donation recipients. For the main study, we chose Scenario 5 (see Appendix C), because choice proportions were close to 50:50 and the means for feeling and reason-based decision making were close to the scale midpoint (around 5), leaving room for an increase in affect-based decision making when testing the effects of using a catalyst.

Main study

Methods

Participants and design. We advertised Study 3 as a study on donation behaviour via Prolific. We aimed to detect small to medium effects (d = .30), as effects of this magnitude are typical for social psychological research (Richard et al., Citation2003). We collected data from 382 English speaking participants residing in the UK to achieve power = .90 with alpha = .05 (G*Power; Faul et al., Citation2007). We increased the number of participants by 10% while keeping cell sizes balanced to account for potential dropout or participants asking for data exclusion. This resulted in an aspired sample size of 420 participants.

Four hundred twenty-one participants completed the study and two of the participants asked for the exclusion of their data at the end of the questionnaire. The remaining sample, therefore, consists of 419 participants (140 male, 275 female, 2 non-binary, 2 other; Mage = 37.03, SD = 12.74Footnote4).

We used a between-participants design with condition (catalyst vs. control) as factor of interest. The dependent variable was the extent to which participants indicate that they base their decision on affect when choosing between organisations. We included driver (reason vs. affect) as a further within-participants factor that was analysed exploratorily (see below).

Materials and procedure. We asked participants to choose between two different organisations working to increase the well-being of animals. Participants were asked to read descriptions of the two welfare organisations and to then decide which of the two they would prefer to donate to. Before they indicated their decision, participants in the catalyst condition read the instructions outlined in Study 2 and then flipped a coin. Participants in the control condition read the respective instructions from Study 2 and then watched a coin spin for a fixed time without seeing the result (to avoid that control participants may assign organisations to heads and tails and use the coin as a decision aid). Participants indicated their decision regarding the organisations and were asked to what extent their decision was based on reason and to what extent their decision was based on feelings (assessed via two separate 7-point Likert scales ranging from 1 = not at all to 7 = very much). Participants were then asked how much they would donate using a slider scale from $0 to $50. If using a catalyst increased affect-based decision making, participants in the catalyst compared to the control condition should indicate that their decision was more strongly based on affect.

Results

Drivers of welfare organisation choices. To test whether using a catalyst results in participants indicating more affect-based decision making, we computed a one-sided t-test for two independent groups (catalyst vs. control). Results indicate that the two groups did not differ significantly in the extent to which their decision was based on affect, t(416.14) = 0.98, p = .164, d = 0.10, with the catalyst group displaying descriptively higher values than the control group, Mcatalyst = 5.57, SD = 1.45; Mcontrol = 5.43, SD = 1.49.

In an exploratory fashion, we examined whether differences were only present for affect or whether also a decrease in reliance on reason occurred by computing a repeated-measures ANOVA with condition (catalyst vs. control) as a between-participants factor and type of driver (affect vs. reason) as a within-participants factor. The extent of influence served as the dependent variable. Results indicate no main effect of condition (F(1, 417) = 0.21, p = .650, = 0.00; Mcatalyst = 5.28, SD = 1.50; Mcontrol = 5.23, SD = 1.48). A significant main effect of type of driver occurred (F(1, 417) = 28.61, p < .001,

= 0.06), in that participants reported stronger reliance on affect versus reason when making the decision (Mfeelings = 5.50, SD = 1.47; Mreason = 5.00, SD = 1.46). The interaction between condition and type of driver was not significant (F(1, 417) = 0.95, p = .331,

= 0.00), with cell means being Mcatalyst&feelings = 5.57, SD = 1.45; Mcontrol&feelings = 5.43, SD = 1.49; Mcatalyst&reason = 4.98, SD = 1.49; Mcontrol&reason = 5.02, SD = 1.44.

Exploratory analysis: donation amount. Previous research (Zhang & Zhong, Citationn.d.) shows that flipping a coin can increase donations. In an exploratory fashion, we therefore, examined the impact of condition (catalyst vs. control, contrast coded with −0.5 for control and 0.5 for catalyst), reliance on reason (z-standardised), reliance on feelings (z-standardised), and the interaction terms between condition and reason as well as condition and feelings on the amount that participants would donate using a multiple regression analysis. On average, participants intended to donate 14.58 $ (SD = 11.22). Only the self-reported reliance on feelings significantly predicted the donation amount, b = 1.87, SE b = 0.55, t = 3.41, p = .001. All other predictors and interactions were not significant, see .

Table 3. Results of the multiple regression analysis from Study 3.

Discussion

Study 3 was designed to complement the previous studies by assessing participants’ personal experiences of how much affect played a role when making a decision. We hypothesised that participants in the catalyst compared to the control condition report stronger reliance on affect when making their decision. Such a result pattern could indicate that people do have insight into how a catalyst, such as a coin flip, may work.

All participants reported stronger reliance on affect (vs. reason). However, conditions did not significantly differ in their reliance on affect; in fact, there was only a small descriptive tendency that catalyst (vs. control) participants rely more on affect. Stronger reliance on affect also predicted stronger intentions to donate, which was, however, not qualified by condition. Study 3, therefore, does not provide support for the hypothesis that using a catalyst results in stronger reliance on affect when making decisions. Below we discuss limitations and outline opportunities for further research.

Interestingly, the fact that participants on average reported a stronger reliance on affect compared to reason invalidates our concern that participants may be reluctant to report reliance on feelings for normative reasons in the study. Future research interested in reliance on affect in decision making may, therefore, fruitfully build on the materials developed here.

General discussion

This manuscript investigated whether the use of a catalyst (such as a coin flip or lottery wheel that does not determine the decision but provides a suggestion) results in more affect-based decision making. Previous research showed that using a catalyst results in stronger affective reactions (Jaffé et al., Citation2019; Jaffé & Greifeneder, Citation2021), yet it remained unclear whether these reactions translate to affect-based decisions. We conducted four studies to test this hypothesis; Studies 1a, 1b, and 2 focused on behavioural outcomes, while Study 3 relied on a self-report. All studies were situated in the context of hypothetical donation decisions for animals, following previous research (Hsee & Rottenstreich, Citation2004).

Study 1a provides preliminary support for our hypothesis by showing that participants using a lottery wheel as catalyst showed less scope sensitivity in their donation behaviour compared to conditions in which participants were asked to spin the lottery wheel and remember the number (wheel control) or did not spin a wheel (standard control). Study 1b, that included a few structural changes as well as changes in the instructions, did not replicate this pattern. We preregistered Study 2 with the journal and conducted a well-powered replication study that used both a lottery wheel and a coin flip to make donation suggestions. Results, however, again do not show that using a catalyst results in less scope sensitivity (compared to a control group), thereby not providing support for our hypothesis.

In the preregistered Study 3, we turned to individuals’ self-report to find out how much they perceived affect to play a role when making decisions. Pretest 1 indicates that participants engage in the lay belief that flipping a coin my help listening to their gut feeling, yet it remained an open question whether participants also report this tendency when actually using it. Participants were asked to decide between two charities and to then indicate to what extent their decision was based on feelings. Participants on average reported high levels of reliance on feelings, yet catalyst and control participants did not significantly differ. Results, therefore, do not support the hypothesis that using a catalyst is associated with higher self-reported reliance on affect when making hypothetical donation-related decisions.

Limitations and directions for future research

Throughout all of our studies, we investigated hypothetical donation decisions. Although we built on previous research when designing the study setup, the decision to donate for animals or for a fictitious charity might still have been rather abstract for participants. Eventually, this may have made the task not very engaging, which could have been particularly unfavourable given that the studies were conducted online. Moreover, the tasks’ abstractness may have lowered the need for or the potential help provided by the catalyst. Future research could implement real, and therefore, more engaging or meaningful decisions to test whether a catalyst impacts reliance on affect or affect-based decisions. This could be achieved by actually donating money to charities based on participants’ choices (either directly, or by deducting a certain amount from a bonus payment awarded to participants). Such changes could result in participants engaging more in the task, render the task more meaningful, and make the decision more difficult, all of which may eventually make the catalyst more powerful.

Another aspect of the study design that could benefit from further exploration is the type of random decision aid used. Throughout our studies, we used two different types of catalysts, a lottery wheel (Study 1a, Study 1b, Study 2) and a coin flip (Study 2 and Study 3). Whereas the lottery wheel can be used to provide a continuous suggestion (e.g. a value between 0 and 50), the coin flip makes categorical suggestions. We limited the range of the continuous outcomes to ensure that all suggestions by the lottery wheel would be rather moderate (see Studies 1a and 1b; future research, however, may explore the differential effects of moderate vs. extreme suggestions). In Study 2, both catalysts make the same categorical suggestion, however, future research may explore individuals’ perceptions of the two aids: Are both considered equally helpful when making a decision? Is the use of one (e.g. the coin flip) eventually more familiar? Are individuals equally willing to use the aids? If differences occur on the level of subjective evaluations, additional studies are required to better understand how the impact of the devices differs and how these differences need to be taken into account when testing the original hypotheses in a rigorous manner.

It should also be noted that all studies have been conducted online with online samples. The preregistered studies followed this approach because the required sample sizes are difficult to collect in the local lab. However, the online study setup comes with less experimental control, meaning that participation is subject to more noise. To illustrate, we looked at study completion time estimates from the Preliminary Study, Study 1a, and Study 1b, in which participants were asked to make four decisions (Study 2 only asked for one decision). Although these estimates are subject to noise (i.e. they not only reflect participation duration, but also the quality of the Internet connection, server response times, etc.), they illustrate certain variability between studies (Preliminary Study: Median = 315.50 s, M = 510.43 s, SD = 1112.49; Study 1a: Median = 226.00 s, M = 276.32 s, SD = 191.38; Study 1b: Median = 247.00 s, M = 287.08 s, SD = 186.09). When dealing with small effects (see, e.g. Study 3), this additional noise could have made it more difficult to find significant results. Future research could choose a lab-based approach to increase experimental control and test whether a change in setting may allow to find support for the hypothesis.

On the conceptual level, the theoretical implications that result from the studies are inconclusive. Previous work has shown that using a catalyst strengthens affective reactions (Jaffé et al., Citation2019; Jaffé & Greifeneder, Citation2021) and our Pretest 1 also highlights that participants do have the lay belief that a catalyst (such as a coin flip) helps listening to their gut feelings. In contrast, Studies 1b and 2 do not provide support for the hypothesis that stronger affect results in more affect-driven decision making. Future research could, therefore, investigate whether there are moderating factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of individuals’ behaviour being driven by affect. One of these moderators could be the decision setting: When creating the study materials, we built on previous research highlighting the association between affective decision making and scope insensitivity (Hsee & Rottenstreich, Citation2004). One notion of this research is that reason-based decision making can be determined from donating more money to more animals in need. Research on the identifiable victim effect, however, highlights that this might not be how people act when donating money (Small et al., Citation2007; Small & Loewenstein, Citation2003). Small and colleagues (Citation2007), for example, showed that participants would donate more money when seeing one child in need, whereas learning about statistics and the overall need resulted in smaller donations. One could speculate that this occurs because helping one person seems feasible, whereas a small donation seems unimportant when being confronted with a huge demand. In our studies, the animals in need were always identifiable (four versus one exemplars), however, the same donation amount might be perceived as more or less important depending on the number of recipients. Scope insensitivity might, therefore, reflect a rational choice, too. Future research could test and control for perceived effectiveness of donations and further investigate the link between affect and scope insensitivity. If this link can be debated, future research should select a different study setup to test whether using a catalyst results in more affect-based decisions.

Future research may also discard our hypothesis and test whether psychological mechanisms different from individuals’ lay beliefs make the use of a catalyst helpful. For instance, a catalyst such as a coin flip could increase individuals’ ability to visualise the outcome, and therefore, ease decision making by allowing for a different perspective. Alternatively, the catalyst may signal a change from a more reflective or deliberative decision mode to the implementation stage of the decision making process (Beckmann & Gollwitzer, Citation1987; Douneva et al., Citation2019; Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, Citation1987). Future research could investigate these different accounts to better understand how using a random aid could impact decision-making processes.

Conclusion

In this manuscript, we investigated whether using a catalyst – a random decision-making aid that does not determine the decision but suggests a decision option – results in more affect-based decision behaviour and higher self-reported reliance on affect. We tested this hypothesis across four studies in the realm of hypothetical donation decisions. Results, however, do not provide support for the hypothesis. Interestingly, this is not in line with individuals’ lay beliefs when being asked about their own experiences – pretest results indicate that participants believe that using a catalyst (e.g. a coin flip) can help them listen to their gut feelings. We outline potential improvements and opportunities for future research studies and speculate that other downstream consequences than reliance on affect may be worth exploring.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (46.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anna-Marie Bertram, Helena Brunt, Jonas Mumenthaler, and Daniela Sutter for their help with creating the study materials. We thank Caroline Tremble for proofreading our manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This influence is neither good nor bad upfront, and governed by highly flexible and adaptive processes (e.g., Huntsinger et al., Citation2014).

2 The results hold when examining each type of animal individually. The main effect of condition was not significant for pandas, F(2, 209) = 2.38, p = .095, dolphins, F(2, 209) = 1.67, p = .190, elephants, F(2, 209) = 1.38, p = .253, or polar foxes, F(2, 209) = 2.55, p = .081. Tukey HSD pairwise comparisons indicated no significant differences between the catalyst and wheel control group, all ps > .802, or the catalyst and the standard control group, all ps > .130.

3 In particular, mean donations for pandas were 14.06€ (SD = 12.51), 15.06€ (SD = 13.34) for dolphins, 16.35€ (SD = 13.26) for elephants, and 14.00€ (SD = 13.14) for polar foxes.

4 One participant indicated 0 as their age, which we coded as a missing.

References

- Albarracín, D., & Kumkale, G. T. (2003). Affect as information in persuasion: A model of affect identification and discounting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.453

- Avnet, T., Pham, M. T., & Stephen, A. T. (2012). Consumers’ trust in feelings as anformation. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(4), 720–735. https://doi.org/10.1086/664978

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

- Batson, C. D., Kobrynowicz, D., Dinnerstein, J. L., Kampf, H. C., & Wilson, A. D. (1997). In a very different voice: Unmasking moral hypocrisy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(6), 1335–1348. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.6.1335