ABSTRACT

Recent research has provided compelling evidence that children experience the negative counterfactual emotion of regret, by manipulating the presence of a counterfactual action that would have led to participants receiving a better outcome. However, it remains unclear if children similarly experience regret’s positive counterpart, relief. The current study examined children’s negative and positive counterfactual emotions in a novel gain-or-loss context. Four- to 9-year-old children (N = 136) were presented with two opaque boxes concealing information that would lead to a gain or loss of stickers, respectively. Half of the children chose between two keys that matched each box, whereas the other half were compelled to select one box because only one of the two keys matched. After seeing inside the alternative, non-chosen box, children were significantly more likely to report a change in emotion when they could have opened that box than when they could not have. The effects were similar for children who lost stickers and won stickers, and neither effect varied with age. These findings suggest that children may become capable of experiencing regret and relief around the same time, although their expression of these counterfactual emotions may vary with actual and counterfactual gains and losses.

The emotions of regret and relief arise when we judge that an alternative choice in the past would have led to a more or less appealing version of the present, respectively, than the actual present (Epstude & Roese, Citation2008; Weisberg & Beck, Citation2012). For example, if you procrastinated while studying and revised content only hours before sitting an exam, you may feel regret if you narrowly fail the exam (and realise you could have studied more), and relief if you narrowly pass the exam (and realise you could have studied less). Regret and relief thus involve counterfactual thinking; mentally undoing an actual past event and imagining an alternative version of that event (Beck & Riggs, Citation2014; Gautam, Suddendorf, Henry, & Redshaw, Citation2019; Rafetseder & Perner, Citation2012).Footnote1 Counterfactual emotions such as regret and relief support learning and enable more adaptive decision-making in the future (McCormack, O'Connor, Cherry, Beck, & Feeney, Citation2019; Redshaw & Ganea, Citation2022; Zeelenberg & Pieters, Citation2007). After feeling regret or relief about narrowly failing or passing an exam, for instance, you may learn to spend more time studying to avoid failing exams in the future.

The development of regret and relief in children is typically measured with a two-box choice task (Amsel & Smalley, Citation2000). In this task, children are presented with two boxes concealing prizes and are told to choose one box. After seeing inside their chosen box, children are asked to rate how they feel about its content (e.g. a sticker). Critically, the experimenter then reveals the content of the unchosen box – which is either better or worse than that in the chosen box – and children are again asked how they feel about the content of their chosen box. Studies typically find that children begin to report a negative change in emotion after seeing a better alternative prize around age 5–6, and a positive change in emotion after seeing a worse alternative prize around age 7–8 (O’Connor et al., Citation2012, Citation2015; Van Duijvenvoorde et al., Citation2014; Weisberg & Beck, Citation2010, 2012). These findings have been interpreted as evidence that children experience regret and relief much like adults. However, a general limitation of these studies is that children may not be mentally undoing their past choices when reporting negative and positive emotion changes. It is possible that children may instead be experiencing simpler, non-counterfactual emotions after seeing the alternative prize (e.g. frustration when seeing the better prize: “I want the better prize”, or excitement when seeing the worse prize: “I’m glad I have the better prize”). Indeed, in an alternative paradigm, 3- to 10-year-olds could spin one of two “wheels of fortune” that each had alternative outcomes, and children were shown either just the outcome of their selected wheel or the outcomes of both wheels (Guerini et al., Citation2020). In this case, the strength of children’s emotions did not vary as a function of whether the outcome of the counterfactual (non-selected) wheel was revealed, which is inconsistent with a genuine experience of regret or relief.

Weisberg and Beck (Citation2012) attempted to differentiate regret and relief from other emotions by manipulating the responsibility children had over a positive or negative outcome. In their study of 5- to 8-year-olds (Experiment 2), some children had complete control over their choice between two cards (which concealed a better or worse outcome), some had to roll a die to determine the selected card, and some had the experimenter roll a die to determine the selected card. Results showed that the more responsibility children had over the outcome, the more likely they were to experience a negative or positive change in emotion after seeing the alternative outcome (also see O’Connor et al., Citation2015). And because responsibility over the outcome reliably increases the intensity of counterfactual emotions in adults (Zeelenberg et al., Citation1998), the implication is that children may begin to similarly experience counterfactual emotions during this age period. Nonetheless, it is important to consider that even when children had less or no responsibility over the outcome, Weisberg and Beck’s (Citation2012) task still entailed a salient counterfactual event that would have led to the alternative outcome (i.e. children might have readily thought that the die could have landed otherwise). A more direct test of the role of counterfactuals in children’s emotional experiences would manipulate the presence of a counterfactual path to the alternative outcome within the constraints of the task. In this case, children with responsibility over the outcome might be inclined to consider the relevant counterfactual path to the alternative outcome (i.e. the path in which they chose differently), whereas children with no responsibility over the outcome might be unlikely to imagine any counterfactual path to the alternative outcome.

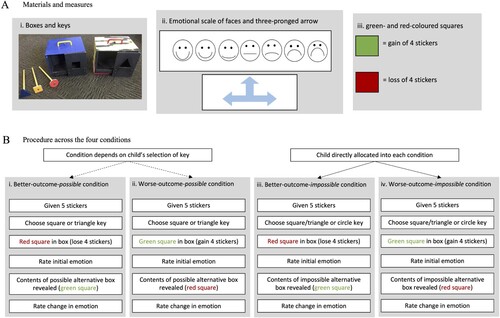

To provide such a direct test, Gautam et al. (Citation2022) introduced 4- to 9-year-old children to a novel version of the two-box task: one box with a triangle-shaped keyhole and one box with a square-shaped keyhole, which concealed a small or large number of stickers, respectively. In two of the four conditions, children were presented with two keys that matched the boxes (i.e. a square and triangle key), such that they had a genuine choice between the boxes. In the “better-outcome-possible” condition, aimed at eliciting regret, the box that children selected was revealed to have the smaller prize, and children subsequently found out that the alternative box had the larger prize. In the “worse-outcome-possible” condition, aimed at eliciting relief, the box that children selected was revealed to have the larger prize, and children subsequently found out that the alternative box had the smaller prize. In the two corresponding control conditions, by contrast, children were presented with one matching key (either the triangle or square key) and one non-matching key (a circle key), such that they were compelled to select the only box with the matching key. Children in these “better-outcome-impossible” and “worse-outcome-impossible” conditions therefore could not have possibly received the alternative prize by selecting the alternative key. That is, although some of these children may have imagined counterfactuals such as “if only the experimenter had offered me a different key”, they critically had no direct means to open the alternative box within the constraints of the task.

Gautam et al. (Citation2022) found that children in the better-outcome-possible condition were significantly more likely to report a negative change in emotion after seeing the alternative prize than children in the better-outcome-impossible condition, consistent with a genuine experience of regret. However, children in the worse-outcome-possible condition were not significantly more likely to report a positive change in emotion after seeing the alternative prize than children in the worse-outcome-impossible condition, inconsistent with a genuine experience of relief. The authors suggested that the lack of evidence for relief may be due to the aforementioned developmental lag between the emergence of regret and relief. Theoretically speaking, however, such a lag would be difficult to explain, because if both of these emotions fundamentally depend on counterfactual thinking then one might expect them to show similar developmental trajectories.

Across the developmental literature, including in Gautam et al.’s (Citation2022) study, two-box tasks are typically implemented in a gain context, whereby children will always receive a (smaller or larger) prize no matter which box they choose. One possibility is that, in these situations, children who receive the larger prize may not feel particularly strongly about avoiding the smaller prize, and therefore not show evidence of relief even if they are capable of experiencing this counterfactual emotion in principle. Indeed, among adults, relief is instead strongly associated with “near miss” experiences, in which we experience a positive or neutral outcome but could have experienced a negative outcome (Sweeny & Vohs, Citation2012). In the exam example introduced earlier, you may feel relief because you nearly failed the exam.

One exception to this common approach is the aforementioned study by Weisberg and Beck (Citation2012), which implemented both gain and loss contexts in two experiments. In regret initial-win trials, the 4- to 8-year-old children would win some tokens when they could have won a larger amount of tokens, and in regret initial-lose trials, children would lose tokens when they could have won tokens. In relief initial-win trials, children would win tokens when they could have lost tokens, and in relief initial-lose trials, children would lose some tokens when they could have lost a larger amount of tokens. The results suggested that children were experiencing regret in both initial-win- and -lose trials, whereas they were only experiencing relief in the initial-win trials. As outlined earlier, however, this study still entailed a salient counterfactual event that would have led to the alternative outcome.

The current study examined if children would experience both regret and relief in a “gain-or-loss” context, as in Weisberg and Beck’s (Citation2012) regret initial-lose and relief initial-win trials. Critically, however, we also included control conditions where the alternative outcome could not have possibly occurred within the constraints of the task. As in Gautam et al.’s (Citation2022) study, children were presented with two boxes and two keys, and they either had a genuine choice between two boxes with matching keys or were compelled to select a particular box because they only had access to one matching key. Unlike in Gautam et al.’s study, however, children were also given 5 stickers at the beginning of the task. In the better-outcome-possible condition, children lost 4 stickers but could have gained 4 more stickers by selecting the other key, whereas in the better-outcome-impossible condition they lost 4 stickers but could not have possibly gained 4 more stickers by selecting the other key. In the worse-outcome-possible condition, children gained 4 stickers but could have lost 4 stickers by selecting the other key, whereas in the worse-outcome-impossible condition children gained 4 stickers but could not have possibly lost 4 stickers by selecting the other key.

If children experience regret in gain-or-loss contexts, then those in the better-outcome-possible condition should be more likely to report a negative change in emotion after the alternative box is revealed than those in the better-outcome-impossible condition. Likewise, if children experience relief in such contexts, then those in the worse-outcome-possible condition should be more likely to report a positive change in emotion after the alternative outcome is revealed than those in the worse-outcome-impossible condition. Overall, by virtue of the control conditions, this study provides a direct test of the role of possible alternative outcomes in children’s apparent experiences of regret and relief in gain-or-loss contexts.

Method

Participants

We recruited 145 children (75 females, 69 males) ranging from 4 to 9 years of age (M = 6.94 years, SD = 1.73 years, range = 4.00–9.98 years). Children were tested at the Queensland Museum (n = 79), Early Cognitive Development Centre at the University of Queensland (n = 7) or an Out of School Hours Care Centre (n = 59), see Supplementary Materials for descriptions of testing environments. Nine children were excluded from analyses: 8 for failing at least one manipulation check, 1 for attempting to open the box with the incorrect shaped key (i.e. the triangle box with the circle key). Children in the final sample (N = 136) were in one of four conditions: better-outcome-possible (N = 38, 16 males, 22 females, M = 6.93 years, SD = 1.60 years, range = 4.10–9.77 years); better-outcome-impossible (N = 31, 16 males, 15 females, M = 7.15 years, SD = 1.81 years, range = 4.24–9.98 years); worse-outcome-possible (N = 35, 16 males, 19 females, M = 7.00 years, SD = 1.67 years, range = 4.28–9.95 years); or worse-outcome-impossible (N = 32, 13 males, 19 females, M = 6.97 years, SD = 1.93 years, range = 4.08–9.94 years). We conducted a post hoc power analysis based on Gautam et al.’s (Citation2022) effect size (equivalent to f2 = 0.40) between the better-outcome-possible and better-outcome-impossible conditions. With a significance criterion of α = 0.05, the current study’s sub-samples of n = 69 (for the better-outcome-possible and better-outcome-impossible conditions) and n = 67 (for the worse-outcome-possible and worse-outcome-impossible conditions) provided strong chances of detecting effects of this size (both > .99).

Children were directly allocated into the better-outcome-impossible and worse-outcome-impossible conditions (as they were always given the non-functional circle key and the functional triangle or square key), whereas children were allocated into either the better-outcome-possible or worse-outcome-possible condition depending on their outcome based on functional key choice (i.e. whether they selected the functional key that led to gaining or losing stickers). Testing continued until all conditions had 30–40 participants, and all children received 9 stickers and an armband at the conclusion of the study, regardless of condition.

Procedure

A schematic summary of the full procedure is provided in . The experimenter first introduced children to a 7-point scale of emotional faces based on Gautam et al. (Citation2017), and then gave children 5 stickers. Children were then introduced to the two boxes and two keys (the shape of which varied across conditions), but they were never shown the third key in order to minimise the chance that they would imagine a counterfactual in which that key was offered. The experimenter explained that inside the boxes could be green- or red-coloured squares, and that children would win 4 more stickers if they found a green square but would lose 4 stickers if they found a red square. Children were asked memory check questions regarding their understanding of the keys and coloured squares (i.e. “what box does the square/triangle/circle key open?” and “what happens if you open a box that has a green/red square on the inside?”). If children failed these memory checks, the experimenter repeated the instructions and then repeated the questions (no children failed the repeated memory checks). The experimenter then hid the boxes behind a screen and surreptitiously placed a green square in one box and a red square in the other, before offering children a selection of the two shown keys. Across all conditions, children were asked to indicate their initial emotion after opening their chosen box, and then the experimenter revealed the contents of the alternative box and asked children to rate their emotion change using a three-pronged arrow (happier, sadder, or the same) adapted from Weisberg and Beck (Citation2012). We implemented this widely used measure as previous developmental studies have consistently found it to be appropriate for detecting significant effects of interest in children (see Gautam et al., Citation2022; McCormack et al., Citation2020; O’Connor et al., Citation2015). Finally, children were asked if they understood what would have happened if they had chosen the non-chosen key, and to confirm that they remembered which keys had been offered initially.

Figure 1. Experimental materials and procedure across conditions. (Ai) Puzzle boxes and keys: children in the better/worse-outcome-possible conditions selected between the two keys that matched the boxes (i.e. the square and triangle), whereas children in the better/worse-outcome-impossible conditions selected between one matching key and one non-matching key (i.e. the circle). (Aii) Children were instructed that if they opened a box that had a green square on the inside, they would receive 4 more stickers or if they opened a box that had red square on the inside, then 4 of their stickers would be taken away. (Aiii) Scale of faces (from Gautam et al., Citation2017) explained to children from left to right: “This face is extremely happy, this face is very happy, this face is a little bit happy, this face is not happy or sad, this face is a little bit sad, this face is very sad, and this face is extremely sad”. After the contents of the alternative box (the non-chosen box) were revealed, children were asked if they felt “happier, sadder or the same” about the box they had chosen, with assistance of the three-pronged arrow (adapted from Weisberg & Beck, Citation2012). (B) Schematic diagram summarising the procedure for children in each of the four conditions.

Counterbalancing

We counterbalanced which box had the green square and the red square inside the hidden compartment, such that sometimes the green square was in the box with the square hole and sometimes it was in the box with the triangle hole. In addition, for the better/worse-outcome-impossible conditions, we counterbalanced if children had the choice of the triangle and circle key or the square and circle key.

Results

Initial emotion ratings

There was a significant difference between conditions for the initial emotion ratings on the 7-point scale (range from −3 = extremely sad to 3 = extremely happy) after opening the chosen box, F(3, 135) = 36.63, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.31. Children who won 4 stickers initially (worse-outcome-possible and worse-outcome-impossible conditions), M = 2.45, SD = 0.72, reported feeling significantly happier than children who lost 4 of their stickers (better-outcome-possible and better-outcome-impossible conditions), M = −0.14, SD = 1.90, t(132) = 10.33, p < .001, d = 1.80. There was no significant difference in initial emotion ratings between the worse-outcome-possible (M = 2.51, SD = 0.66) and worse-outcome-impossible (M = 2.38, SD = 0.79) conditions, t(132) = 0.39, p = .695, d = 0.18, nor between the better-outcome-possible (M = −0.29, SD = 1.89) and better-outcome-impossible (M = 0.03, SD = 1.94) conditions, t(132) = -0.92, p = .360, d = 0.17. Age was not significantly correlated with initial emotion ratings, r(135) = -.05, p = .576, suggesting older and younger children similarly cared about the sticker prizes.

Emotion change ratings

As children could select from three emotion change ratings (happier, sadder or the same) after seeing inside the alternative box, we first examined if their responses significantly differed from an a priori chance level of 33.3% (see Supplementary Material for findings). However, because children may have an inherent predilection to respond in a particular manner after seeing inside the non-chosen box – rather than a predilection to respond at random chance levels – the key analyses were ones that compared children’s responses between the equivalent counterfactual and non-counterfactual conditions (as in Gautam et al., Citation2022). That is, these analyses allowed us to directly examine the influence of a counterfactual alternative on children’s emotion change ratings.

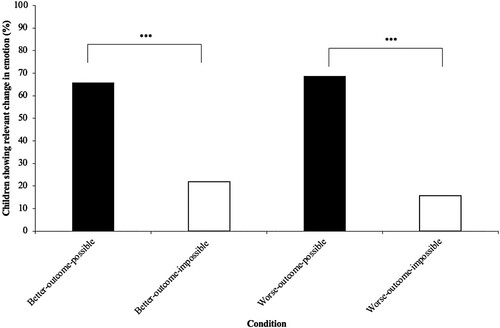

Regret analyses

A logistic regression examined children’s emotion change ratings across the relevant conditions (better-outcome-possible and -impossible) and age. These variables explained 23.5% of variance in children’s responses (Nagelkerke R2). Children were significantly more likely to report feeling sadder in the better-outcome-possible condition than the better-outcome-impossible condition, Wald χ2 (1, N = 69) = 11.78, p < .001, w = 0.41 (see ), suggesting that those in the former condition were genuinely experiencing regret after the alternative outcome was revealed. Age did not predict children’s responses, Wald χ2 (1, N = 69) = 0.02 p = .900, w = 0.01, and there was no evidence that the condition effect varied with age, Age × Condition interaction, Wald χ2 (1, N = 69) = 0.76, p = .383, w = 0.11.

Figure 2. Percentage of children who reported the relevant change in emotion (happier for the better-outcome-possible and better-outcome-impossible conditions, and sadder for the worse-outcome-possible and worse-outcome-impossible conditions). Black bars depict the possible conditions, and white bars depict impossible conditions. ***p < .001.

Relief analyses

An equivalent logistic regression revealed that the variables explained 35.2% of the variance (Nagelkerke R2) in children’s responses in the worse-outcome-possible and -impossible conditions. Children were significantly more likely to report feeling happier in the worse-outcome-possible condition than the worse-outcome-impossible condition, Wald χ2 (1, N = 67) = 16.46, p < .001, w = 0.50 (see ), suggesting that those in the former condition were genuinely experiencing relief after the alternative outcome was revealed. Age did not predict children’s responses, Wald χ2 (1, N = 67) = 0.03, p = .862, w = 0.02, and there was no evidence that the condition effect varied with age, Age × Condition interaction, Wald χ2 (1, N = 67) = 0.72, p = .396, w = 0.10.

Comparing regret and relief

Lastly, a logistic regression (Nagelkerke R2 = 1.4% variance explained) revealed that there was no significant difference in the likelihood of children feeling sadder in the better-outcome-possible condition and feeling happier in the worse-outcome-possible condition, Wald χ2 (1, N = 73) = 0.08, p = .784, w = 0.03. Again, there were no significant differences in these relevant emotion changes across age, Wald χ2 (1, N = 73) = 0.69, p = .406, w = 0.10, and no evidence that the condition effect varied with age, Age × Condition interaction, Wald χ2 (1, N = 73) = 0.02, p = .881, w = 0.02.

Discussion

The current study provided a direct test of young children’s capacity to experience both regret and relief, by manipulating the presence of possible alternative outcomes and examining emotion changes in a gain-or-loss context. Results showed that children in the better-outcome-possible condition were significantly more likely to report feeling sadder after the alternative box was opened than children in the better-outcome-impossible condition, conceptually replicating Gautam et al.’s (Citation2022) finding of genuine regret in a gain-only context. Unlike Gautam et al. (Citation2022), however, results also showed that children in the worse-outcome-possible condition were significantly more likely to report feeling happier after the alternative box was opened than children in the worse-outcome-impossible condition, thus demonstrating that young children can also experience genuine relief.

The current findings contrast with several previous studies suggesting that children more readily experience regret than they experience relief (Gautam et al., Citation2022; Guerini et al., Citation2020; O’Connor et al., Citation2012, Citation2015; Van Duijvenvoorde et al., Citation2014; Weisberg & Beck, Citation2010). There are at least two possible (and compatible) reasons for the discrepancy in results. First, previous studies lacked a control condition with no direct path to the alternative outcome (as addressed in Gautam et al., Citation2022), and second, previous studies were presented in a gain-only context (with the exception of Weisberg & Beck, Citation2012), which may not be salient enough to elicit reportable feelings of relief in younger children. Indeed, children, like adults (i.e. Sweeny & Vohs, Citation2012), may be more likely to experience reportable feelings of relief in a “near miss” situation than a gain-only situation because a loss may be more motivating to avoid than a smaller gain. Consistent with this interpretation, research on the development of loss aversion has found that from around age 5 children’s risky choices are associated with the probability of losing rather than the probability of winning (Steelandt et al., Citation2013).

Even though children were not explicitly told that one box would have a green square and the other box would have a red square – and even though they were not shown that there was only one green square and one red square – it is possible that when children opened their chosen box, they already mentally generated the relevant alternative before the contents of the other box were revealed. Specifically, some children may have assumed that if their chosen box had a green square (gain of 4 stickers) then the other box must have had a red square (loss of 4 stickers), and vice versa. Therefore, when the experimenter revealed the contents of the other box, these children may have merely reported their change of emotion in response to seeing the alternative prize, rather than in response to thinking about that prize per se. In either case, it is clear that the presence of a possible past choice leading to the alternative prize significantly increased children’s likelihood of reporting both negative and positive emotion changes. And although our study was limited in that we did not explicitly ask participants about counterfactuals (cf. O’Connor et al., Citation2012), it is likely that the children in the control conditions reported fewer emotion changes because they did not think of a counterfactual manner in which the alternative prize could have been obtained. Our findings thus complement and extend those of Weisberg and Beck (Citation2012), by suggesting that children do indeed experience emotions driven by their responsibility over the outcome and an understanding of what else could have happened.

The primary goal of this study was to examine whether children experienced genuine regret and relief in a gain-or-loss context, rather than to examine the developmental trajectory of these counterfactual emotions per se. Nonetheless, as in Gautam et al.’s (Citation2022) earlier study, we found no significant age effects in children’s reports of regret and relief in a broad sample aged 4–9 years. However, it is important to note that both the current study and that of Gautam et al. (Citation2022) had very limited statistical power to detect age effects, as there were only around five participants of each age within each condition. To conclusively test the developmental trajectory of these emotions, we recommend higher powered studies with appropriate control conditions. Indeed, recent highly powered studies with a similar experimental structure have found critical transitions around age 6 in the effect of counterfactual alternatives on children’s moral judgements (Gautam et al., Citation2023; Wong et al., Citation2023).

In conclusion, our results suggest that children genuinely experienced the counterfactual emotions of regret and relief in a context in which they could have experienced a gain or a loss. Children may acquire the capacity to experience these two emotions concurrently, although their expression of these emotions may vary as a function of whether the actual and counterfactual outcomes involve gains or losses.

Dataset_usedforanalyses_R1.xlsx

Download MS Excel (18.8 KB)Supplementary Material_Regret and Relief_R1.docx

Download MS Word (17.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Queensland Museum, Early Cognitive Development Centre and School Plus for their support on this project throughout the data collection period and the families who participated. Jonathan Redshaw is supported by a Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE210100005) granted by the Australian Research Council.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For current purposes, regret and relief are conceptualised as counterfactual counterparts. However, we acknowledge that there is an alternative, non-counterfactual form of relief, which is experienced at the conclusion of an aversive experience (see Hoerl, Citation2015; Johnston et al., Citation2022; Sweeny & Vohs, Citation2012).

References

- Amsel, E., & Smalley, J. D. (2000). Beyond really and truly: Children’s counterfactual thinking about pretend and possible worlds. Children’s Reasoning and the Mind, 22(5), 121–147.

- Beck, S. R., & Riggs, K. J. (2014). Developing thoughts about what might have been. Child Development Perspectives, 8(3), 175–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12082

- Epstude, K., & Roese, N. J. (2008). The functional theory of counterfactual thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(2), 168–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868308316091

- Gautam, S., Bulley, A., von Hippel, W., & Suddendorf, T. (2017). Affective forecasting bias in preschool children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 159, 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2017.02.005

- Gautam, S., Owen Hall, R., Suddendorf, T., & Redshaw, J. (2023). Counterfactual choices and moral judgments in children. Child Development, 94(5), e296–e307. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13943.

- Gautam, S., Suddendorf, T., Henry, J. D., & Redshaw, J. (2019). A taxonomy of mental time travel and counterfactual thought: Insights from cognitive development. Behavioural Brain Research, 374, 112108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112108

- Gautam, S., Suddendorf, T., & Redshaw, J. (2022). Counterfactual thinking elicits emotional change in young children. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 377. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0346

- Guerini, R., FitzGibbon, L., & Coricelli, G. (2020). The role of agency in regret and relief in 3- to 10-year-old children. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 179, 797–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2020.03.029

- Hoerl, C. (2015). Tense and the psychology of relief. Topoi, 34(1), 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-013-9226-3

- Johnston, M., Mccormack, T., Graham, A., Lorimer, S., Beck, S., Hoerl, C., & Feeney, A. (2022). Children’s understanding of counterfactual and temporal relief in others. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 223(1), 105491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2022.105491

- McCormack, T., Feeney, A., & Beck, S. R. (2020). Regret and decision-making: A developmental perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(4), 346–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420917688

- McCormack, T., O'Connor, E., Cherry, J., Beck, S. R., & Feeney, A. (2019). Experiencing regret about a choice helps children learn to delay gratification. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 179, 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2018.11.005

- O’Connor, E., McCormack, T., Beck, S. R., & Feeney, A. (2015). Regret and adaptive decision making in young children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 135, 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2015.03.003

- O’Connor, E., McCormack, T., & Feeney, A. (2012). The development of regret. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 111(1), 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2011.07.002

- Rafetseder, E., & Perner, J. (2012). When the alternative would have been better: Counterfactual reasoning and the emergence of regret. Cognition & Emotion, 26(5), 800–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.619744

- Redshaw, J., & Ganea, P. A. (2022). Thinking about possibilities: Mechanisms, ontogeny, functions and phylogeny. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 377(1866). http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0333

- Steelandt, S., Broihanne, M. H., Romain, A., Thierry, B., & Dufour, V. (2013). Decision-making under risk of loss in children. PloS one, 8(1), e52316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052316

- Sweeny, K., & Vohs, K. D. (2012). On near misses and completed tasks: The nature of relief. Psychological Science, 23(5), 464–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611434590

- Van Duijvenvoorde, A., Huizenga, H., & Jansen, B. (2014). What is and what could have been: Experiencing regret and relief across childhood. Cognition and Emotion, 28(5), 926–935. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.861800

- Weisberg, D. P., & Beck, S. R. (2010). Children’s thinking about their own and others’ regret and relief. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 106(2–3), 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2010.02.005

- Weisberg, D. P., & Beck, S. R. (2012). The development of children's regret and relief. Cognition & Emotion, 26(5), 820–835. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.621933

- Wong, A., Cordes, S., Harris, P. L., & Chernyak, N. (2023). Being nice by choice: The effect of counterfactual reasoning on children's social evaluations. Developmental Science, e13394. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13394

- Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2007). A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1701_3

- Zeelenberg, M., van Dijk, W., & Manstead, A. (1998). Reconsidering the relation between regret and responsibility. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 74(3), 254–272. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1998.2780.