ABSTRACT

The idea of “defensible space” was/is to give residents control of public spaces they feel they have no control over. If they gained control, they would defend these spaces, care for them, and protect them (and their property) from crime. The pandemic required a rapidly retrofitted public space – emergency cycle lanes, widened pavements, or play streets. The practices of negotiating public space to take permitted exercise or queue for essential groceries forced us all to rethink ideas of territoriality and safe encounter. Closer to home, domestic territories were also altered. Walking past terraced homes’ front gardens onto housing estates, or past high-density blocks and fenced-off playgrounds, we realized how valuable leftover “wasted spaces” had become. Courtyards became spaces to sit out amongst abandoned cars. Doors and windows were left open, renegotiating senses of privacy and ownership. People appropriated what would have been thought of as the public realm for social[ly distanced] activities. Wandering strangers were often waved through, acknowledged with a nod if their mask obscured a smile of greeting, the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us that social ritual can overcome confused territoriality, and that some indefensible spaces can be remodeled.

Introduction: London lockdown walks

As soon as lockdown rules allowed walks, ostensibly for “exercise”, we escaped the house. But it was our minds that needed the workout, so while we drifted, our talk spanned buildings, places, the minutia of city life, as well as large unanswerable urban issues, emulating Michael Sorkin’s (Citation2013) description of the walk between his Manhattan flat and studio.

The local park felt too full of joggers and buggies avoiding each other, so we turned and started walking in nearby streets, past terraces and housing blocks.Footnote1

Now we saw an altered landscape, front gardens with flowers supplanted by vegetable planters, bike shelters built from salvaged materials, a squeezed in shed converted to a workplace, windows full of rainbow posters, people reading the paper on their front step, kids playing on the asphalt. Neighbours had time to talk over fences (where fences still remained; by the summer front garden walls were dismantled and replaced by planters facilitating chats with passersby.) And as more people took to walking the streets – so we turned off the main roads, following cut-throughs – across carparks, courtyards and onto the pathways across housing estates.

COVID-19 has caused us to develop a more nuanced appreciation of open space’s social and therapeutic potential, such as access to better air quality and more physical activity, among other benefits … . Safety and security now takes on an entirely different meaning, one that goes well beyond Oscar Newman’s Defensible Space theory. (Brumfield & Cubillos, Citation2020)

Prompted by our experiences out walking during the pandemic (especially in the first big lockdown), this paper focuses on territoriality, which underpins and connects the two clusters of characteristics to consider the mechanisms that facilitate defensible space, and how space use altered during the lockdown. We explore the need for more, not less, confused space, for greater softening of edges and boundaries, to encourage fluidity in the way spaces are used, extending and questioning classical understandings of defensible space.

New concepts of safety, security, and control during COVID-19

During COVID-19, with public spaces essential to public health for access to air, sunlight, exercise, to see people (if not engage at close range) (PHE, Citation2020), a different interpretation of safety and security emerged. Our security fears shifted from safety against personal attack, vandalism, or property damageFootnote2 to the invisible transgression and communication of disease.Footnote3 The visible fortressing and physical gating and barricades, which exemplify Secure by Design and CPTED (Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design), seemed less important to safeguarding health than a clear definition of personal territory. Security during COVID-19 became maintaining a self-contained bubble of private space within public settings.

The pandemic also highlighted the social and spatial inequalities of space standards or limited access to private outside space (Resolution Foundation, Citation2020), being confined to our homes highlighted the inequitable distribution of domestic space, revealing those who were and indeed still are struggling, living in a few, overcrowded rooms. Activities began to concentrate in/on private spaces like roof terraces, balconies, and gardens ():

Balconies and roofs are reimagined as new alternatives to the urban piazza, becoming sites where it is possible to communicate, make new friends, flirt, sing, dance, exercise, all from a ‘safe distance’. (Alcocer & Martella, Citation2020, p. 6)

Figure 1. A man sits on his window sill in Islington, London, during the 2020 Covid-19 lockdown. (Photograph: Dylan Martinez. Permission: Reuters).

Sendra and Sennett (Citation2020) argue that the drive to install order, control and security over public spaces has suppressed the city’s liveliness; defensible space is seen as indicative of societies’ desire to suppress the disorder. Sennett has criticized spaces on housing estates as “places with no public life” (Sendra, Citation2016, p. 4), a consequence of Newman and Coleman’s strictly applied defensive boundaries restricting free access and deterring chance encounters. When meetings are limited, any strangers are unexpected or feared. Sendra’s (Citation2016) design interventions aim to counter this fear through “infrastructures for disorder” that readjust the relationship between formal and informal urban spaces. Increasing visibility and permeability on the boundaries of housing fosters greater diversity of users, enabling residents to become more tolerant of difference and better prepared to face the unexpected. COVID-19 has tested our tolerance of strangers, meanwhile the loosening up of spatial uses and increased “informal disorder” have offered unique opportunities for strange encounters.

Territoriality in council housing estates

In his 1973 book, Defensible Space: People and Design in the Violent City, Newman explained how territoriality arises from interconnected actions:

designating clearly defined areas under the influence and control of inhabitants;

establishing a sense of ownership for legitimate users of the space;

and encouraging familiarity with neighbors or passers-by.

Three mechanisms work to foster territoriality and extend defensible space:

using objects to mark areas under control (applying tactical urbanism);

concentrating or diffusing activities into “wasted space” (inhabiting pavements, car parks, or underused green areas);

recognition/legitimacy of presence (knowing who belongs in a space).

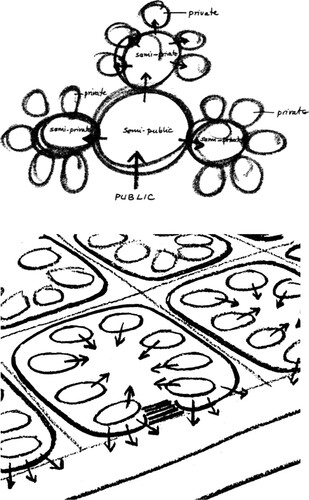

Newman’s bubble diagrams for the flowerlike relationship among private, semi-private, semi-public, and public spaces are well-known. Interior spaces within flats were clearly private and streets were public. Lobbies, stairs, or shared internal spaces were semi-private spaces, and communal grounds or gardens within the housing estate were semi-public. However, depending on the design and layout, lifts and other internal circulation areas, such as walkways or access decks, could be considered semi-public.

In Newman’s diagrams () or cellular social model (which Knoblauch, Citation2014, likens to foam), individual domestic cells are connected by shared ownership of space or an opening in a wall, a door, or window, with obvious divisions and symbolic thresholds creating a safer society. The nested groups of eight homes focus inward on their semi-private space, protected by a defensive boundary (Knoblauch, Citation2014). But the pandemic has hardened the dividing membrane between private domestic cells, as we have learnt to see the inside of our home as safe and the outside as dangerous. It has also affected the interaction between groups of cells and households in semi-private/semi-public spaces.

Figure 2. Newman’s territorial hierarchy and requirements for natural surveillance. (Source: Newman (Citation1973). Permission: Kopper Newman).

Jan Gehl (who endorses the value of defensible space in his book Life Between BuildingsFootnote5) similarly recommends the positive subdivision of housing into smaller more manageable units:

the clear structure strengthens natural surveillance, helps inhabitants know which people ‘belong’ and improve the possibility for making group decisions concerning shared problems. (Gehl, Citation2003, p. 61)

Osmosis and permeability of people and things

Gehl’s quote underlines the importance of “permeability” to defensible space, allowing or limiting access to those who “belong”. In urban design, greater permeability and pedestrian accessibility have long been desirable traits for safe places (e.g. Hillier, Citation1988). Thinking at a cellular level, substances move into and out of cells across a permeable membrane. The movement mechanisms are diffusion (the movement of dissolved solutes, such as oxygen and CO2 in the lungsFootnote6) or osmosis (the diffusion or movement of water from a solution of greater concentration into a less concentrated one). These concepts of flow, concentration, diffusion (as the movement of things), and osmosis (going from intense concentrations of people and activities to dispersed) are a new and useful way to consider how defensible space works.

Spending longer periods at home during the pandemic, often in closer proximity to family, with increasing intensity and concentration of occupation, the diffusion of work and relaxation activities, as well as chairs and other furniture, out into external spaces was understandable.

Our walks could also be considered a form of osmosis as we moved from close concentrations of people to more diffuse ones. As we got bored/braver, we walked on past no entry private street signs, under gateways, across the communal grass verges, into enclosed gardens, up on to walkways, closely past doors and windows. We noted more open windows and doors ajar, a sign of attitudes to security weakening with people home during the day.

Mechanisms for territoriality: objects as markers of ownership

As the weather improved we saw increasing diffusion of domestic objects into the public realm. Not only watering cans for the plants and tomatoes, but books, half-drunk cups of tea, a paddling pool, tables, cushions and chairs of all types; deckchairs, kitchen chairs, a sofa.

Reoccupying the parking space

As traffic lessened, London streets were given back to people: cars giving over space to pop up bike lanes, both giving way to pedestrians or dog-walkers. This practice of tactical urbanism inhabiting vehicular space extended into estates.

One lockdown shift we observed was cars transformed into street furniture or static play objects. A young mum sitting in an open hatchback, her kids out playing amongst, and even beneath, the surrounding cars. Parking spaces had become homezones and playstreets without the need for formal designation or signs.Footnote7

Knowing who “belongs”

A key mechanism for defensible space is recognition. Hall’s (Citation1966) The Hidden Dimension set precise communication limits distinguishing “social distances” related to human scale and senses.Footnote11 Hall described these as the “invisible bubble of space” that people like to keep between themselves and others, and while many of his ideas seem simplistically deterministic, Gehl’s promotion of them (for example, incorporating them in diagrams that show how little facial expression can be read from a second-floor balcony) ensured their ongoing relevance to designing the urban realm, either to inhibit or promote contact.

Current social distancing practices made us hyper sensitive to these nuanced spectrums and distances. It takes half a minute to walk past someone, normally sufficient time to recognise and acknowledge them. Wearing a mask obscures familiarity, making other signals critical (e.g. the turquoise Deliveroo food delivery bag, as a passport justifying a stranger’s presence).

Soft thresholds to homes

Standing on the doorstep during the ten weeks of the Thursday night NHS ‘clap for carers’, the edges of our homes formed too precise and thin a threshold.

The external, public sphere is merging with the personal, private one, occupying the same space and the same time. (Alcocer & Martella, Citation2020, p. 3)

We notice that balconies and access decks have become more than places to sit, eat, people watch, clap, or places for drying washing and plant pots. These are for relaxation, exterior living rooms, but also temporary offices or studies, as we watched workers and students angling to catch the wifi or avoid the glare on their laptops.

Conclusions: social ritual can overcome confused territoriality

COVID-19 has altered our expectations for domestic privacy. The GLA’s Interim London Housing Design Guide identifies ideal characteristics for home life:

Homes in the city should provide the opportunity to look out on and enjoy surrounding public and shared open spaces. At the same time, the home should be a comfortable, private setting for family and individual pursuits, social interaction and relaxation. Private outdoor space should also offer these qualities. People value highly the opportunity to relax outdoors without being seen by neighbours or passersby. (GLA, Citation2010, p. 64)

Figure 3. A group in Hackney desperate to catch some sun. (Photograph and permission: Shireen Bahmanizad).

Similarly, Secure by Design and CPTED practitioners have called for a reassessment of defensible space, evolving from a primarily exclusionary, crime-focused approach, to one for creating pro-social spaces, designed for the positive encounter (Armitage & Ekblom, Citation2019). Mehta’s (Citation2020) view is that the pandemic and social distancing are generating a new kind of sociable space that is overcoming the limitations of physical design and our historical ways of analyzing it.

Our lockdown dérives accentuated that territoriality and encounter on the edges of domestic settings (particularly within mass post-war housing) and were very different from the flaneur’s saunter amongst (formerly) crowded shopping streets, or the suburban trudge home from the station, past the hedges and fences demarcating individual dwellings. By stripping away the crowds, COVID-19 homed in on those parts of the public realm that continued to be occupied, highlighting the places where domestic activities were extended and concentrated in new and novel ways.

The mechanisms of inhabitation and control we observed on our walks in the Spring and Summer of 2020 were dynamic and fluid; the osmosis of people and activities spilling out from overconcentrated and constrained interiors ebbed and flowed, indeed they continue to do so. Where building membranes were permeable, with diffusion possible through open doorways, or windows, a tide of objects flooded into transitional defensible zones at the edges of homes. As we transition to a “living with Covid” world, these pandemic traces will no doubt remain, chairs and plant pots marking out softer looser territories.

Urbanists, play specialists and health professionals have long admired the relaxed walkable housing blocks of Vauban, Freiberg (Gill, Citation2019), where play and pedestrians’ dominance over cars are signaled by kids’ tricycles and skateboards left on unfenced areas of grass. British home zones or co-housing like Marmalade Lane or Lilac in Leeds share a similar relaxed informality. The pandemic has taught us that with suitable social negotiation, this informal Dutch-style woonerf (living streets) approach to streets and courtyards is manageable in a tight and dense urban context. We should have confidence that spaces on dense (council) housing estates can be reclaimed and shared, placed under collective control. Confidence that design for disorder isn’t a designing-in crime or social unease, that the courtyards and green spaces on housing estates aren’t confused or indefensible space. It may require accepting a slightly messy informal inhabitation of the public realm, but for shared spaces to work as public living rooms, they need to feel suitably domestic, casual, comfortable, and welcoming.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The unreferenced, indented quotations in this paper are taken from our Dérive Fieldnotes over the Spring and Summer of 2020. #105 of Sorkin’s (Citation2018) list Two hundred and fifty things an architect should know is how to dérive. Debord (Citation1958, p. 63) allows a city walk to be a dérive if it prompts “playful-constructive behavior” and departs from “other usual motives for movement”. Our fieldnotes record our attempts to be both playful and constructive under circumstances that were far from usual.

2 Halford et al. (Citation2020) found all crime declined during lockdown before leveling off. Domestic burglary dropped by 25% in the first weeks. Unlike other crimes analyzed, as movement returned, a 1% increase in pedestrian mobility in residential areas (stimulating greater guardianship and surveillance) produced a 1% further decrease in recorded residential burglary.

3 Over a similar time period, UCL’s COVID-19 Social Study measured the prevalence of 16 stress factors. The most common stressor reported was worrying about friends or family outside the household (64% of participants), next, getting food (54.4%), becoming seriously ill from COVID-19 (49.4%) catching COVID-19 (44.7%). 20.8% reported fears for their own safety/security – toward the bottom of the list. Fears that crime would rise again when lockdown eased were the lowest reported concern (Fancourt et al., Citation2020).

4 Half of UCL’s COVID-19 Social Survey respondents felt they lacked control over future plans (Fancourt et al., Citation2020).

5 Danish first edition 1971, English translation, 1986.

6 Osmosis also describes smells travelling around a house or, more symbolically, music through an open window.

8 The soon-to-be-revised Manual for Streets (DCLG & DfT, Citation2007) criticizes parking directly in front of homes as breaking up frontages, obscuring surveillance, while SBD favors locked garages or hard standing with unrestricted views of cars (ACPO and Secured by Design, Citation2019).

11 Intimate distance 0–45 cm; can feel a speaker’s breath on your cheek. Personal distance 45–130 cm; can hear clearly without leaning in. Social distance 1.3–3.7 m; can distinguish a smile from a frown. Public distances above 3.7 m shift from aural to visual, where a nod or wave from across the street replaces verbal communication.

References

- ACPO and Secured by Design. (2019). Secured by design homes 2019: Version 2. Association of Chief Police Officers. https://www.securedbydesign.com/images/downloads/HOMES_BROCHURE_2019_NEW_version_2.pdf

- Alcocer, A. A. Y., & Martella, F. (2020, June 4). Public house: The city folds into the space of the home. The Architectural Review. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/public-house-the-city-folds-into-the-space-of-the-home

- Armitage, R., & Ekblom, P. (Eds.). (2019). Rebuilding crime prevention through environmental design: Strengthening the links with crime science. Routledge.

- Batty, M. (2020). The coronavirus crisis: What will the post-pandemic city look like? Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 47(4), 547–552.

- Brumfield, A., & Cubillos, C. (2020). Cities and the public health: Our new challenge in urban planning. https://www.gensler.com/research-insight/blog/cities-and-public-health-our-new-challenge-in-urban-planning

- Coleman, A. (1985). Indefensible space. Building Design, 738, 14–18.

- Debord, G. (1958). Theory of the dérive. In K. Knabb (Ed.), Situationist international anthology (Revised and Expanded ed., 2006, pp. 62–66). Bureau of Public Secrets.

- Department of Communities and Local Government (DCLG) and Department for Transport (DfT). (2007). Manual for streets. Thomas Telford Publishing.

- Fancourt, D., Bu, F., Mak, H. W., & Steptoe, A. (2020, March 27). COVID-19 social study results: Release 1. https://www.covidsocialstudy.org/results

- Gehl, J. (2003). Life between buildings: Using public space (5th ed. Jo Koch, Trans.). The Danish Architectural Press.

- Gill, T. (2019). Widening the bandwidth of child-friendly urban planning in cities. Cities & Health, 3(1–2), 59–67.

- GLA. (2010). Interim London housing design guide. https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Interim%20London%20Housing%20Design%20Guide.pdf

- Halford, E., Dixon, A., Farrell, G., Malleson, N., & Tilley, N. (2020). Crime and coronavirus: Social distancing, lockdown, and the mobility elasticity of crime. Crime Science, 9(1), 11.

- Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. Doubleday.

- Hillier, B. (1988). Against enclosure. In N. Teymur, T. A. Markus, & T. Woolley (Eds.), Rehumanizing architecture (Chap. 5). Butterworths.

- Jacobs, J. M., & Lees, L. (2013). Defensible space on the move: Revisiting the urban geography of Alice Coleman. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), 1559–1583.

- Knoblauch, J. (2014). The economy of fear: Oscar Newman launches crime prevention through urban design (1969–197x). Architectural Theory Review, 19(3), 336–354.

- Lees, L., & Warwick, E. (2022). Defensible space: Mobilisation in English housing policy and practice (RGS-IBG book series). Wiley.

- Mehta, V. (2020). The new proxemics: COVID-19, social distancing, and sociable space. Journal of Urban Design, 25(6), 669–674.

- Newman, O. (1973). Defensible space: People and design in the violent city. Architectural Press.

- Public Health England (PHE) . (2020). Improving access to greenspace: A new review for 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/904439/Improving_access_to_greenspace_2020_review.pdf

- Resolution Foundation. (2020). Lockdown living: Housing quality across the generations. https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/lockdown-living/

- Roberts, M. (1988). Caretaking – who cares? In N. Teymur, T. A. Markus, & T. Woolley (Eds.), Rehumanizing architecture (Chap. 9). Butterworths.

- Sendra, P. (2016). Infrastructures for disorder. Applying Sennett’s notion of disorder to the public space of social housing neighbourhoods. Journal of Urban Design, 21(3), 335–352.

- Sendra, P., & Sennett, R. (2020). Designing disorder: Experiments and disruptions in the city. Verso.

- Sorkin, M. (2013). Twenty minutes in Manhattan. North Point Press.

- Sorkin, M. (2018). What goes up, the rights and wrongs to the city. Verso.

- Warwick, E. (2014). Defensible space as a mobile concept: The role of transfer mechanisms and evidence in housing research, policy and practice [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Kings College London.

- Warwick, E. (2020). Defensible space. In R. Kitchin & N. Thrift (Eds.), International encyclopedia of human geography (Vol. 3, pp. 195–201). Elsevier.

- Webb, M. (2020). New rooms for the new normal. http://interconnected.org/home/2020/04/02/new_rooms

- Young, A. (2021). The limits of the city: Atmospheres of lockdown. British Journal of Criminology, 61(4), 985–1004.