ABSTRACT

Data is variably imagined and practiced according to values, behaviors, and norms fashioned over an extended temporal register, meaning data initiatives are not only influenced by contemporary technological and structural conditions, but also by the forces of history and culture. This claim is advanced by situating Cape Town’s smart city plans in a national historical context, highlighting how desires to be a “global city” driven by data, evidence, and openness come up against a data culture largely incompatible with these goals. A genealogy of South Africa’s politicized history of recordkeeping, biometrics, databases, and information sharing reveals the roots and legacy of an ambivalent data culture, which poses a considerable challenge to today’s data ambitions. Through this example, the paper makes two contributions to critical understandings of urban data. First, it advances the notion of data cultures – the values, behaviors, and norms ascribed to data by groups or organizations that together shape practices of data collection, management, use, and sharing. Second, it draws attention to the multi-scalar production of smart cities, when global data imaginaries meet national-scale characteristics at local places. These findings present a new lens for understanding the relative success or failure of (urban) data initiatives.

Introduction

This organisation will be driven by data and evidence, focusing relentlessly on our customers: the people of Cape Town. (Patricia de Lille, in Abrahams, Citation2016)

A few recent studies have highlighted obstacles to realizing the smart city vision in Cape Town (Boyle, Citation2019; Ni Loideain, Citation2017; Odendaal, Citation2016). Here, barriers mirror the experience of many global South cities aiming to be smart – lack of technical education and skills, inadequate basic services, limited digital infrastructure, and socioeconomic inequality (Aurigi & Odendaal, Citation2021; Watson, Citation2015). As Han and Hawken (Citation2018) argue, however, a preoccupation in the wider literature with structural and technological conditions forecloses other ways of understanding smart city successes and failures – notably the role of cultural variation. In addressing this research gap, the present study contributes to a small but emergent literature on data cultures within communities of practice, organizations, and geographic locations (Albury et al., Citation2017; Bates, Citation2017; Currie & Hsu, Citation2019; Stark & Hoffmann, Citation2019). Limited attention to data cultures is somewhat surprising when considered against both the long-term “cultural turn” in the social sciences, and the recent elaboration of myriad high-level conceptual frames used to understand data-in-the-world, including (inter alia) data politics (Bigo et al., Citation2019), data power (Kennedy & Bates, Citation2017), data justice (Dencik et al., Citation2016), data colonialism (Thatcher et al., Citation2016), and data publics (Mörtenböck & Mooshammer, Citation2020). Yet, attentiveness to data cultures is important because data is variably imagined and practiced according to diverse values, behaviors, and norms (Tarantino et al., Citation2019).

This paper also contributes to a broader push to temporalize the smart city (Kitchin, Citation2019). Notably, scholars have identified how future-focused smart city initiatives have present-day affordances – the imaginaries they produce about future urban life present an opportunity to intervene in the present (Datta, Citation2019; Leszczynski, Citation2016; White, Citation2016). Similarly, researchers have looked to the recent past to help explain how smart cities come into being (Mora et al., Citation2017), including in Cape Town (Odendaal, Citation2016). However a key contention guiding this paper is that smart city discourses and those that actually exist (Shelton et al., Citation2015) can be profitably examined by tracing their roots much further back in time (see also Cugurullo, Citation2018; Datta, Citation2015; Yang, Citation2020). Doing so reveals how smart cities are often continuities of larger scale processes of urbanization, governance, economy, and culture, as opposed to the idealized corporate – government imaginary which is “often deeply decontextualised and strangely ‘placeless’” (Datta & Odendaal, Citation2019, p. 388). Beyond the globally circulating models of smart urbanism lie diverse cities with unique histories and contexts, which require systematic analysis in order to understand their influence on current smart city discourses and materialization (Kitchin, Citation2015).

Through placing the contemporary Cape Town smart city in a national historical perspective, this article demonstrates how the city’s data-driven ambitions, despite being modeled on global ideas, come up against a data culture shaped more substantially by local – national dynamics. This argument adds additional weight to recent evidence on the local variations of global smart urbanism (e.g. McFarlane & Söderström, Citation2017; Sadowski & Maalsen, Citation2020), yet it does so through highlighting the agency of an intermediate scale – the national. But rather than acting as a mere intermediary between global ideas and local implementations, this paper shows how national characteristics have considerable material force in shaping city-level smart initiatives. This argument is based on empirical research into contemporary Cape Town smart city policies, initiatives, and wider data environment, drawing on interviews with stakeholders in government and civil society, document analysis, and participant observation. This is complemented by a genealogical reading of the technopolitical histories of data and data technologies in South Africa, to problematize current contestations over urban data management, use, and sharing over a longer temporal frame. Genealogy has been used widely in urban studies as a way to reveal the provenance of urban ideas and discourses (Barnett, Citation2020; Lawton, Citation2020; Weaver, Citation2017), and in the case of smart urbanism specifically, it presents a powerful method of critique for assembling various threads of development and fragments of meaning coalescing in the smart city present (Yang, Citation2020). In this paper, genealogy reveals the longer trajectory of Cape Town’s smart ambitions, connecting the challenges of Cape Town’s contemporary data initiatives to national level 20th and twenty-first century South African technopolitics. The legacy of the apartheid regime’s data-driven white supremacy looms large here, but this story touches down at various moments of Cape Town and South Africa’s history – from the colonial period (early 1900s to 1948), to the apartheid era (1948–1994), the transition to democracy (1990–1994), and into the present democratic period (1994 onward).

This paper is structured as follows. The next section briefly traces the recent history of smart urbanism in Cape Town, covering the period from 2000 to the present. The subsequent main section reconstructs a smart urban prehistory (extending the temporal frame back to the early 1900s), via three urban data imaginaries central to the city’s contemporary smart ambitions – the desire to be driven by data, evidence, and openness – as concisely revealed in the paper’s epigraph by the ex-Mayor of Cape Town. In connecting these “urban fantasies” (Watson, Citation2014) to South Africa’s politicized history of recordkeeping, biometric identification, databases in governance, and practices of information sharing, this prehistory not only extends the temporal register, it also widens the terrain for interrogating urban data within and beyond smart urbanism (Leszczynski, Citation2016). The final section summarizes the findings and develops a more general theorization of the two main contributions of the paper – the notion of data cultures, and the scalar intersection of the local and the national in smart city materialization.

A short, two-decade history of the Cape Town smart city (2000 to the present)

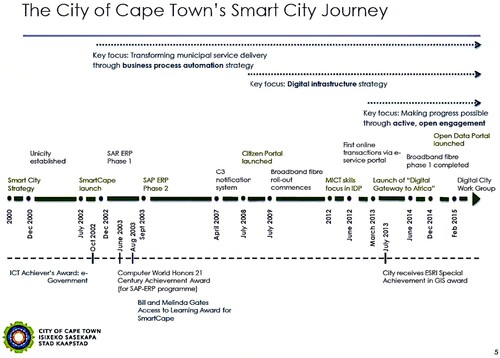

Insofar as their use of the term “smart city”, the City of Cape Town is unquestionably a global innovator in smart urbanism. The term has been used since 2000 when the “Smart City Strategy” was initiated, the same year that the “Unicity” of Cape Town was established amalgamating six contiguous but separate municipalities. In reflecting on their “smart city journey” between 2000 and 2015, the City divided this 15 year period into three phases (see ; Stelzner, Citation2015). In Phase 1, the Unicity project presented an opportunity to develop a foundational digital architecture to automate and streamline internal processes towards the goal of “e-government”. Phase 1’s first key initiative, the 2001 investment in an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system from the vendor SAP, promised substantially improved digital recordkeeping, reporting, and data sharing across City departments, and to this day the system remains the “digital backbone of the organisation and its smart city aspirations” (Boyle & Staines, Citation2019, p. 10). As Phase 1’s second key initiative, the 2002 SmartCape Access Project installed free-access computers in libraries within disadvantaged township areas. Through these two investments the City of Cape Town advanced two framings of the smart city several years before they became central tropes of smart urbanism around the world – smart as digitally enabled, and smart in the sense of human knowledge and capabilities. Writing at the time, Valentine (Citation2004) explains how Cape Town’s “public officials set out to build a ‘smart city’, where informed people could connect to the world and to each other by the technology of the information age”.

Figure 1. The city of Cape Town’s ‘smart city journey’, 2000–2015. From Stelzner (Citation2015).

Phase 2 meanwhile focused on digital infrastructure, notably the launch of an ongoing project to link municipal facilities across the city through fiber broadband. This project was designed to enhance internal communication and e-service capacity, but it also provided the networked infrastructure for a future free public Wi-Fi hotspot initiative. With the back-end ERP database/process management system and broadband infrastructure in place, the city’s retrospective take identified Phase 3 as a turn toward “active, open engagement” between citizens and the city, marked in particular by the January 2015 launch of an open data portal, the first of its kind at the municipal level in Africa.

With its genesis in globally circulating ideas about data-driven urbanism, the flagship open data project is emblematic of the City’s post-2015 smart city strategy. A renewed focus shifted the City’s priorities from its previous digital enablement and smart citizenry objectives, towards investing in data and digital technology for global competitiveness, entrepreneurialism, and to drive evidence-informed decision making (Boyle, Citation2019; Ni Loideain, Citation2017). The open data portal emerged around the time the City updated their smart city framework in 2015 with the launch of the Digital City working group, while also renaming their official smart city framework the “Digital City Strategy”. The new strategy includes 4 pillars: Digital Government with a focus on enabling operational transparency and using technology to improve service delivery and citizen engagement; Digital Inclusion, to close the digital divide through access and skills training; Digital Economy, to create an enabling environment for technology-enabled economic development; and Digital Infrastructure, the strengthening of technology systems and infrastructure to enhance the potential success of digital initiatives in the public and private sectors (Abrahams, Citation2016).

As an initiative that cuts across the four pillars, the open data portal evolved from the very top of the city’s governance hierarchy, as a pet project of ex-Mayor Patricia de Lille who also championed many smart city initiatives during her 2011–2018 tenure. In pursuing open data and other smart city policies, the mayor was heavily influenced by global North cities. As she put it:

Mayor Bloomberg … told me that he wanted to make New York City the digital city in the USA. I replied by saying that I would make Cape Town the digital city on the continent of Africa … We try to put the bar very high and not compete with Johannesburg and Durban. We live in a global village. And to be competitive you must compete with cities like Singapore, Vancouver, New York and Sydney. (in The Worldfolio, Citation2014)

The recent phase’s focus on global competitiveness has met with some success; the City has been awarded honors as a leading smart city in Africa (Lindwa, Citation2019). Yet, attention from global think tanks and technology companies belies substantial barriers to developing, implementing, and benefitting from data – and technology-driven solutions. More critical voices highlight the limited applicability of generic models of smart urbanism in a context defined by resource constraints, the need to redress the social and spatial inequities of apartheid, and a unique constitutionally-mandated focus on developmental local governance (Odendaal, Citation2016). Boyle’s analysis foregrounds three limiting factors: “the digital divide, the current institutional and leadership limitations of The City of Cape Town, and the political complexities of local government in South Africa” (Citation2019, p. 20)

Similar structural and technological barriers are evident in many cities, but what has received much less attention, here and elsewhere, is the role of culture in mediating urban smart ambitions (Allam & Newman, Citation2018; Han & Hawken, Citation2018). In a comprehensive review of the literature on culture and information technology (IT), Leidner and Kayworth (Citation2006) call for more empirical attention to two topics of particular relevance here. First, the authors contend that more research is needed on the interaction between organizational and national level cultures in shaping technology practices because “culture, at any level, needs to be studied within the context of how particular outside cultural dynamics may be influencing the culture of the group under study” (p. 381). Second, more research is needed into the notion of an IT culture itself, “defined as general values people have about information technology” (p. 381), rather than the dominant focus in this literature on the impact of culture on IT. Transposing these two research gaps to the case of data-driven smart urbanism, the following section outlines the historical shaping of a data culture in South Africa, which I argue has implications for data initiatives at the organizational level of the City of Cape Town. Following Choo et al. (Citation2008) I define data culture as the values, behaviors, and norms ascribed to data within social groups, organizations, or settings, which together shape practices of data collection, management, use, and sharing.

A prehistory of the Cape Town smart city (early 1900s to the present)

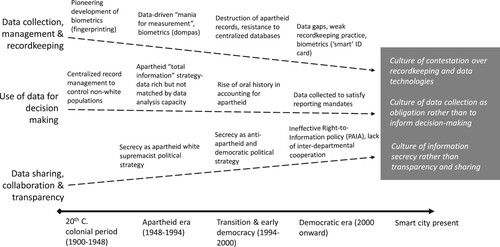

Extending the temporality of smart cities beyond their “approximately 20-year history” (Angelidou, Citation2017, p. 3; Mora et al., Citation2017), this section steps backwards from the ostensible year-2000 origin point to expose the longer historical traces of Cape Town’s smart city present. Beginning in the early twentieth Century colonial period, and then touching down in the apartheid era, the transition to democracy, and the democratic period (see ), a genealogical approach is used to contingently piece together fragments of history relevant to the contemporary juncture. Genealogy provides a way to “intervene, engage, [and] open up new avenues for productive reflection”, rather than present a causal, deterministic, or linear tracing of history and its impact on the present (Gray, Citation2014, p. 3). The genealogical threads of a South African data culture are abstracted into three symbolic urban imaginaries of the city’s contemporary data-driven ambitions. The Databased City subsection examines issues of data collection, management, and recordkeeping. The Evidence-Based City considers the use and analysis of data to produce knowledge for decision-making. The Open City focuses on data sharing, collaboration, and the promotion of transparency.Footnote1 In drawing attention to values, behaviors, and norms that comprise the data culture, I expose a tension between the global ambitions embodied in these imaginaries and the realities of local – national dynamics.

Figure 2. The city of Cape Town’s smart city prehistory: A genealogical approach connects the Cape Town smart city present to national data histories from the colonial period, the apartheid era, the transition to democracy, and into the democratic era.

The databased city

As explained above, a key aspect of Cape Town’s smart city ambitions is the strengthening of data collection and records management capacity across City departments. The quote in the paper’s epigraph illustrates the desire to be data-driven, yet the city has faced considerable barriers to the production and management of data and digital documents across the organization. A municipal employe noted how better documentation and data management will be required to realize smart ambitions:

As we move to an electronic environment, I don’t think we are keeping track of different versions of documents, and making sure documents are retained. This is a focused area of the department as a whole … because right now, people just kind of dump the documents. there’s no structure in terms of folders, etc. (Information manager, City of Cape Town)

This section shows that the Databased City ambition recalls earlier data-driven desires; it rests uneasily against a long history of contestation over recordkeeping, databases, and data technologies in South African society. Historians of technology in South Africa have documented how these technologies must be understood as technopolitical artifacts in this context, given their predetermined intention to enact political goals under colonialism and apartheid. In particular, Breckenridge’s (Citation2005a, Citation2005b, Citation2014) work forensically details the roots of data technologies in the early twentieth Century colonialist desire to identify, categorize, and control non-white populations in South Africa, a campaign that would become further embedded in the digitized biometrics of the apartheid (1948–1994) and democratic (1994-present) eras.

The genesis of biometrics in colonial South Africa provided a basis for what Posel (Citation2000) calls the “mania for measurement” that defined the country’s apartheid era, in which computers and digital databases provided by the likes of IBM (AFSC, Citation1982) made possible the techniques of white minority rule – policing, racial classification, identification, and restriction of movement (Breckenridge, Citation2014). As explained by activists at the time in the book Automating Apartheid, the state’s “data systems make up apartheid’s automated memory bank, giving the minority regime a degree of control that is unrivalled throughout Africa” (AFSC, Citation1982, p. 14). This sentiment was echoed contemporaneously by apartheid officials who conceded the country would “grind to a halt without them” (Edwards & Hecht, Citation2010, p. 631) given the complex and byzantine bureaucracy that defined the regime’s racially-based Keynesianism (Posel, Citation1999).Footnote2 Meanwhile, apartheid-era resistance to data and recordkeeping was symbolized by contestation over the so-called dompas, a sort of “domestic passport” (or more commonly, “dumb pass”) for Black South Africans in use between 1952 and 1986.Footnote3 The dompas included personal data such as the carrier’s photograph, fingerprints, employment details, race classification, and permitted areas of work and travel (Crush, Citation1992). The eventual linkage of the dompas with the centralized national population register database provided the white minority regime with new capacity to identify and enforce mobility restrictions on the Black majority, making it the most hated symbol of apartheid within the country as well as “the outstanding global metaphor for violent white supremacy” (Breckenridge, Citation2014, p. 139; Edwards & Hecht, Citation2010).

A recently-introduced “Smart ID” card (with advanced biometrics) linked to the national population database neatly embodies the intransigence of an ambivalent resist/embrace logic inherent to the South African data culture. A rather direct lineage can be traced between colonial-era fingerprinting, the apartheid-era dompas, and the Smart ID (see ), however, the technology has ostensibly been repurposed for progressive ends, to enable the provision of social services and voting privileges. This points to, as Breckenridge explains, “a certain irony in the fact that these coercive technologies are now being applied to the task of hastening the distribution of benefits to those they were originally designed to subjugate” (Citation2005a, p. 271). Introduced on Nelson Mandela’s 95th birthday in 2013 (he was the symbolic first recipient), then-president Jacob Zuma urged citizens to apply for the Smart ID card in time for the next general election: “by the time you vote next year, you must be a smart South African”, and Deputy President Kgalema Motlanthe added, “[e]very citizen must have an ID, it’s not wrong to have an ID, but of course it was wrong to carry a dompas” (Government Printing Works, Citation2013). Although universally pushed by leaders in the democratic age, biometric technologies are alternately embraced by the public as an appropriate measure to ensure fairness in social program delivery (Donovan, Citation2015), or stridently resisted. A 2017 female-led protest march against Smart ID cards to the Department of Home Affairs offices in Pretoria (Kgosana, Citation2017) evoked a similar march to the same offices by 20,000 women in 1956 to protest against the dompas (SAHO, Citation2019). Now, as then, the considerable affordances of biometric and database technologies are seen as an affront to privacy and autonomy. In particular, there is concern about the potential for surveillance creep if the technology is repurposed (i.e. returns to its original oppressive purpose) for policing, border control, marketing, and debt collection (Kgosana, Citation2017). As an organizer of the protest told me, “I don’t have a problem with the Smart Card, but the problem that I have is how they [might] use this new system” (Employee, access to information organization).

Beyond biometric fantasies, the apartheid regime’s ability to govern pivoted on an ambitious wider “total information” strategy (Breckenridge, Citation2005b), which was, like present-day data, a contradictory mixture of rhetoric and reality. The apartheid bureaucracy was meticulous, however; “racial classification, employment, movement, association, purchase of property, recreation and so on, all were documented – usually in a multi-layered process – by thousands of state offices across the country” (Harris, Citation2000, p. 31). Yet, the apartheid gaze had gaps and inconsistencies, which produced unintended consequences (Dominy, Citation2012). Unexpectedly, new database technologies actually weakened local bureaucratic recordkeeping practice. Breckenridge explains how the introduction of the dompas (and other identity documents for non-Blacks) and its centralized management served to erode careful documentation and reporting practice in local public administration, leaving “a societal debt that all South Africans are still paying today” (Citation2005b, p. 105).

Contemporary evidence indeed points to a challenging data management landscape (Donovan, Citation2015; Ngoepe & Ngulube, Citation2013). A landmark report on the state of post-apartheid public sector recordkeeping, archiving, and data management paints a dismal picture of “woefully inadequate” practices undergirded by a “culture of poor record-keeping” (The Archival Platform, Citation2015, p. 87,89). The report traces the current dilemma to several key historical moments. Under apartheid, the act of person enumeration and recordkeeping in the segregated “Black Homelands” was directly linked with the oppressive regime (Moultrie & Dorrington, Citation2012), which has served to establish these practices to this day “in the minds of many, as an instrument of racist division, control and authority” (The Archival Platform, Citation2015, p. 23). Later, in the final years of apartheid and the transition to democracy (1990–1994), the state engaged in wholesale destruction of records to cover-up the regime’s crimes (Harris, Citation2000, Citation2002), leaving not only gaps in the historical record but also an indifferent attitude towards record preservation in the present day. But ironically even attempts to erase history were met with apartheid bureaucracy; as an interviewee explained:

We’ve even found some documents that document the destruction of documents … if you wanted to send a whole range of boxes or anything, you had to create a new file, you kept a record of everything that was sent to the furnaces. (Researcher, right to information organization)

Returning again to the current juncture, emerging from these historical traces is a vastly differentiated landscape of municipal level data capacity and availability, with obvious implications for any desire to be data-driven. An interviewee explained the challenges of compiling a database on various social issues: “we were putting this database together for the Cities Network, the biggest gaps were in health and education and transport, three of the most critical sectors in South Africa” (Employee, urban research organization), while another explained how data on property development in cities is generally better quality and more easily accessible because of its importance to private sector developers (Employee, activist organization). A further interviewee sums up the situation: “It’s a real paradox, you get feast and famine – there are loads of data you don’t even know are available, you keep discovering new ones, and then there are key datasets that are missing from our landscape” (Employee, urban research network). The key point here is that the desire to be data-driven depends on the availability of relevant data, which itself is shaped by documentation and recordkeeping practices. However, the figure of the Databased City – symbolizing a place in which every action and moment is recorded and made available in aggregate digital form – is merely the foundation of a desire to be data-driven. Attaining “smart” status requires putting data into use – analyzing it to produce knowledge and make informed decisions – which presents another facet of the data culture that the paper now turns to.

The evidence-based city

The inclusion of the word “evidence” alongside “data” in the epigraph suggests an understanding of data and evidence as separate but related concepts. In this interpretation, evidence is something that is acquired through data analysis, an intermediary step between “raw” data collection and the production of knowledge for decision making (Kitchin, Citation2014). By tracing the genealogical threads through the apartheid era into the present, this section demonstrates that like the Databased City, the figure of the Evidence-Based City – in which vast data sources are mined to produce knowledge and drive informed decisions – is similarly challenged by data-related behaviors and norms developed over a long historical register in South Africa. In contemporary times, efforts to be evidence-based are being upended not only by weak data collection and management practice as illustrated in the previous section, but also by a modest culture of data use. A comment by an employe of the City of Cape Town sums up the barriers to be being evidence-driven when the capacity for data analysis is limited:

there is still a lot to be done, especially around the use of the data. With this development and transformation program [to digital government], the intention is to shift to analytics, there is still a lot of exploitation of data that can take place. (Information manager)

These present-day challenges in converting data into evidence and knowledge resembles a similar paradox of the apartheid era. Despite their “mania for measurement”, a deficiency of skills challenged the regime’s ability to know the full spectrum of South African society. Posel explains the data rich but knowledge poor reality of the apartheid state:

“Bureaucrats engaged in rituals of often absurdly detailed quantitative measurement in their continuous efforts to count and classify the population”, however “a paucity of statistical expertise within the civil service at large might account for the amateurish ways in which several departments presented and compiled their statistical data, typically as raw data, with little by way of statistical interpretation”. (Citation2000, p. 116, 135)

Lack of data analysis capacity by the apartheid state produced knowledge absences and voids, a reality of the past that has lingering effects in present day South Africa (Breckenridge, Citation2014), including in the desire for evidence-driven knowledge in the contemporary Cape Town smart city. Several recent investments in data analysis capacity acknowledges this skills and knowledge gap, notably a new cross-department data science team tasked with “exploiting” available data resources. However, despite considerably upgrading skills in the City, discrepancies in data management and standardization and uneven levels of buy-in between municipal departments has resulted in minimal success (Boyle, Citation2019). Boyle’s (Citation2019) evaluation of the barriers to data analysis in the City of Cape Town largely focused on structural and technological factors, however it briefly touches on the role of values and behaviors:

[w]hat is needed is a data culture within The City where there is an intrinsic understanding of the value of data and how it needs to be collected and stored … This needs to happen before advanced data analysis can take place on a broader scale. (Citation2019, p. 17)

data are generated at a local level … through monitoring and collection, through the billing systems, and it will be a requirement for national reporting. All the data is generated purely to fill in national indicator spreadsheets, to satisfy national M&E [monitoring and evaluation] systems. (Employee, urban research organization)

Interestingly, the recent growth of evidence-based activism in Cape Town suggests the emergence of an opposite trend at the grassroots level. Through a collaboration between civil society organizations and local residents, new initiatives to collect and analyze data on service provision in informal settlements usually highlight a gap between what is budgeted and what exists on the ground. However, grassroots evidence-based actions are highly contested and usually ignored outright by civic officials (Cinnamon, Citation2020). With such resistance, the city not only refuses to embrace clear evidence of resource needs in areas of the city they have little information about – despite claims about being driven by data and evidence – they also stake claim to the ability to produce actionable knowledge in the(ir) Evidence-Based City. Meanwhile, for activists and local residents, these efforts demonstrate a moment of embracing data, which itself sits uneasily against a longer trajectory of grassroots resistance to data (as illustrated in the previous section). This example demonstrates how data is alternatively embraced and resisted, not only by South African governments but also in civil society. Further, it alludes to a more general separation of municipal governments from other smart city stakeholders (residents, civil society organizations, private sector, other levels of government), which the paper considers below.

The open city

The inclusion of the phrase “focusing relentlessly on our customers: the people of Cape Town” in the epigraph not only reveals a city immersed in neoliberal logics of governance, it also suggests a genuine desire to be more open, collaborative, and transparent. Like the Databased City and Evidence-Based City, this section shows how the figure of the Open City – in which practices are transparent and all stakeholders have a seat at the table – represents an imaginary in conflict with the cultural reality. Specifically, in the present as in the past, a desire to be open is significantly challenged by a culture of secrecy.

Beginning with current data ambitions, an examination of the city’s open data policy document highlights how making data available is perceived as an opportunity to promote transparency and public engagement:

The City generates a significant amount of data that is useful to citizens. However, this information is often hidden from view … The open data portal will assist citizen engagement with the City by making it easier for members of the public to access data. Enhancing transparency will empower citizens to hold the City to account. (City of Cape Town, Citation2014, p. 4)

Transparency is a normative goal in democratic South Africa, yet an undercurrent of secrecy entrenched under apartheid remains a reality throughout the country’s levels of government, public and private institutions, and wider civil society. An interviewee explains how a history of secrecy in public sector institutions resonates into contemporary data sharing cultures:

[under apartheid] we created these massive national state owned entities, ESKOM [gas corporation] etc., that were centralized and controlled and authoritarian, and that history, some of that hasn’t changed in the way they generate data – and a lot of them are like ‘why must we share with anyone else and what possible value can they get from it? We still want to maintain our control’. (Employee, urban data research organization)

Designed to counter state-sanctioned secrecy, the 2000 Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) was embraced as one of the world’s most progressive pieces of right to information (RTI) legislation. PAIA legislates

access to any information held by the State and any information that is held by another person and that is required for the exercise or protection of any rights … – recognising that – the system of government in South Africa before 27 April 1994 … resulted in a secretive and unresponsive culture in public and private bodies which often led to an abuse of power and human rights violations. (Republic of South Africa, Citation2000)

It’s quite a progressive piece of legislation, the problem is in practice it is a nightmare … It’s weird, it’s kind of perverting that law, because the law actually allows them then to not give you stuff. But more than just blocking it … it is actually used to subvert your access to information. (Interviewee)

Secrecy remains not only in the disconnect between the embrace of open data and wider resistance to information sharing in government. What is also evident is a lack of cooperation and trust between different levels of government, between municipal departments, and between the municipality and the wider public. One interviewee explained the animosity between local and national government on data issues:

they [local government] can’t access the data, or they get charged for it which is quite bizarre … the data becomes a currency, a power bargaining tool rather than the knowledge and the ability to engage on issues. Its symptomatic of the distrust, the disconnect between spheres of government and departments. (Employee, urban data research organization)

To summarize, the key point made in this section is that Cape Town’s desire to tap into global notions of data openness, transparency, and cooperation are met by a pervasive and intransigent national culture of secrecy. As a final example of this contradictory impulse, Boyle (Citation2019) explains how, despite the hype and rhetoric from public officials, even the City’s own smart city policy document (The “Digital City Strategy”) is not publicly available, and had to be accessed through informal channels. When even basic government documents and datasets are acquired “through cajoling and through relationships and through horse trading, you know!” (Interviewee, data advocacy organization), the notion of an Open City – where citizens, governments, and other stakeholders share data, expertise, and effort – thus emerges as perhaps the most improbable data imaginary.

Conclusion

In any country seeking to distance itself from the legacy of the past, actions in the present are carefully scrutinized against that history. In the case of smart urbanism in Cape Town, this study surfaces how contemporary data desires are affected by a broadly-shared and historically-produced data culture – revealed here as a tacking back and forth between resisting and embracing data, evidence, and openness. Clearly the “demented data-gathering obsessions” (Breckenridge, Citation2005a, p. 276) of apartheid casts a shadow over present day data-driven ambitions, representing yet another instance of what Antina von Schnitzler has called “apartheid’s debris”, the regime’s “less evident but more durable remainders that at times come back alive in the present” (Citation2016, p. 92). Yet linking that period to the present condition is incomplete and unsatisfactory. Tracing the threads of meaning from the colonial period, via apartheid, to the democratic transition and into the present day, this paper touches down at various moments of importance to the production of an ambivalent data culture. In the case of the Databased City imaginary, a contemporary data-driven vision comes up against the reality of data-related values, behaviors, and norms. As an interviewee bluntly put it: “I think it’s about the culture. From my experience, people, they don’t value data” (Data manager, right to information organization). To attain status as an Evidence-Based City, data must be analyzed to produce knowledge and inform decision making, but a limited culture of data use is endemic. Put simply, data production is generally undertaken for “ceremonial and compliance purposes” rather than to advance knowledge production and evidence-based decisions (Ngoepe & Ngulube, Citation2013, p. 7). Finally, achieving an Open City is an aspiration at odds with a widespread culture of secrecy that strongly curtails contemporary data sharing and transparency objectives. As Harris sums up, “[i]n my reading of where we are, South Africa is confronted by a conjunction of cultures antithetical to freedom of information and conducive to gatekeeping” (Citation2009, p. 211).

Although evidence from both government and civil society is presented, care should be made not to claim the universality of such a data culture (cf. Milan & Treré, Citation2019). Indeed, some practices suggest other cultures of data production, use, and sharing, especially within civil society. Within the City of Cape Town, the issues highlighted here are not unbeknownst to those pushing smart city agendas. Some interviewees in government specifically highlighted the need to adjust data-driven ambitions to the local-national context rather than global models. Certain arms of the national government meanwhile have made considerable advancements in data use and sharing. Produced in collaboration with OpenUp, a Cape Town-based open data and civic technology organization, the National Treasury’s “Muni Money” website provides open data, interactive maps, and infographics on municipal level finances held at the national level (https://municipalmoney.gov.za/). These examples hint at an evolving data culture, however realizing smart ambitions will require more investigation of how the local data culture affords or constrains effective action (Han & Hawken, Citation2018; Tarantino et al., Citation2019).

These findings suggest the need for further conceptual development of data cultures from a critical social science perspective, as an additional framework to examine datafication beyond the structuralism of data power/politics/justice/colonialism lenses. This is not to say that culture in any way stands alone, however; indeed, the previous analysis traces the development of a contemporary data culture shaped through technological, political, and social histories. As a conceptual basis with which to investigate data cultures, the more established area of “information culture” provides some limited, if largely uncritical, guidance. At the intersection of organizational behavior and information science, this field examines how cultural values impact overall IT strategies, and the development, adoption, use, and outcomes of IT systems (Leidner & Kayworth, Citation2006; Wright, Citation2013). The key requirement needed, according to Curry and Moore, is

[a] culture in which the value and utility of information in achieving operational and strategic success is recognised, where information forms the basis of organizational decision making and Information Technology is readily exploited as an enabler for effective Information Systems. (Citation2003, p. 94)

In summarizing recent work on “variegated smart urbanism”, Sadowski and Maalsen (Citation2020, p. 2) argue that “the reality of a particular smart city is shaped by the interplay between its political economy (whose interests) and urban geography (what places)”. This is an important observation, but as the present study shows, it offers an incomplete analytical and geographic framework. Extending their point in two ways, the present study highlights a further dimension (culture), and calls for nuance in how the local geographies of smart cities can be understood (informed by global imaginaries, and further shaped by local-national dynamics). A few other studies have come to similar conclusions. Yang’s (Citation2020, p. 1) “cultural history of the smart city” of Songdo, South Korea linked historical moments of societal transformation to the city’s data-driven present, including periods of industrialization urbanization, globalization, and militarization. Hoyng (Citation2020, p. 5) traced a disconnect between globally influenced aspirations of data openness in Hong Kong with an intransigent “governmental culture of relative secrecy”. For Datta (Citation2015), utopian visions behind the Dholera smart city are inextricably linked to the longer history of urban planning in India, and represent a model to scale up nationally through India’s “100 smart cities” ambition. More recently, Datta (Citation2019) linked modernist notions of progress to present smart city conditions in India; and similar to the present study, connects practices and outcomes at the city scale with national level culture. Evidence from the present study suggests that the City of Cape Town cannot escape national technopolitical data regimes, despite attempts to bypass the national context and tap straight into global smart urbanisms. Thus, while Joss et al. (Citation2019, p. 23) identify an “an inherent tension between the smart city’s local, material grounding and its expansive, global reach”, these findings suggest that, in addition to the need to territorialize global smart urban imaginaries through a careful consideration of local context and capabilities, the impact of local-national dynamics requires further specific attention. More broadly, this work contributes to an “extended geographies” of smart urbanism that shows how the “where” of smart cities is better understood as relationally-produced over multiple geographies in and beyond municipal administrative boundaries (Fard, Citation2020; Söderström et al., Citation2021).

To conclude, a genealogical reading of data’s technopolitical histories combined with a contemporary empirical analysis provided a basis for rejecting the ahistorical and placeless imaginaries of smart urbanism in “Africa’s Digital City”. This created an opening to make visible the role of culture, at the intersection of the local organization and the nation, in shaping the success of data ambitions. An interesting next step would be to conduct a similar study of eThekwini (Durban metropolitan area), Tshwane (Pretoria metropolitan area) or Johannesburg, to see how the urban data culture changes when the national level touches down in a different yet similar city shaped by its own particular technopolitical regime. Understanding that data is cultural, and that data cultures vary between places, organizations, and groups, presents a powerful standpoint for interrogating the relative success or failure of any data ambitions, which can work in complement with research on more commonly-cited technological and structural forces.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the peer reviewers and editor for their helpful suggestions, and to research participants for their time and insight. A portion of the research for this article was conducted during a visiting fellowship at Wits University in Johannesburg, which was funded by the South African National Research Foundation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 These symbolic urban imaginaries riff off the city’s own structure for their 5-year Integrated Development Plan, which includes; The Opportunity City, The Safe City, The Caring City, The Inclusive City, and the Well-Run City (City of Cape Town, Citation2014).

2 Further parallels might be made here between the propping up of apartheid by IBM and other computer manufacturers, and the contemporary influence of IBM and other companies on the corporatized smart city.

3 Identity documents used to afford or restrict movements have a much longer history in South Africa, dating to at least 1760 in the Cape colony (Savage, Citation1986).

References

- Abrahams, R. (2016). The city of Cape Town’s digital journey: Towards a smarter future. City of Cape Town.

- AFSC. (1982). Automating Apartheid: US computer exports to South Africa and the arms embargo. American Friends Service Committee.

- Albury, K., Burgess, J., Light, B., Race, K., & Wilken, R. (2017). Data cultures of mobile dating and hook-up apps: Emerging issues for critical social science research. Big Data & Society, 4(2), 1–11.

- Allam, Z., & Newman, P. (2018). Redefining the smart city: Culture, metabolism and governance. Smart Cities, 1(1), 4–25.

- Alvarez León, L. F., & Rosen, J. (2020). Technology as ideology in urban governance. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 110(2), 497–506.

- Angelidou, M. (2017). The role of smart city characteristics in the plans of fifteen cities. Journal of Urban Technology, 24(4), 3–28.

- Aurigi, A., & Odendaal, N. (2021). From “smart in the box” to “smart in the city”: Rethinking the socially sustainable smart city in context. Journal of Urban Technology, 28(1-2), 55–70.

- Barnett, C. (2020). The strange case of urban theory. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 13(3), 443–459.

- Bates, J. (2017). Data cultures, power and the city. In R. Kitchin, T. Lauriault, & G. McArdle (Eds.), Data and the city. Routledge.

- Beer, D. (2019). The data gaze: Capitalism, power and perception. Sage.

- Bigo, D., Isin, E., & Ruppert, E. (2019). Data politics: Worlds, subjects, rights. Routledge.

- Boyle, L. (2019). URERU smart city series part 3: The opportunities and challenges of smart city development in Cape Town. Urban Real Estate Research Unit, University of Cape Town.

- Boyle, L. (2020). URERU smart city series part 4: The way forward for the city of Cape Town and what it means to be ‘smart’ in Africa. Urban Real Estate Research Unit, University of Cape Town.

- Boyle, L., & Staines, I. (2019). URERU smart city series part 1: Overview and analysis of Cape Town’s digital city strategy. Urban Real Estate Research Unit, University of Cape Town.

- Breckenridge, K. (2005a). The biometric state: The promise and peril of digital government in the new South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 31(2), 267–282.

- Breckenridge, K. (2005b). Verwoerd's bureau of proof: Total information in the making of apartheid. History Workshop Journal, 59(1), 83–108.

- Breckenridge, K. (2014). Biometric state: The global politics of identification and surveillance in South Africa, 1850 to the present. Cambridge University Press.

- Buthelezi, M. (2012). Orality, record keeping and corruption: Is good record keeping un-African? https://web.archive.org/web/20191203075238/http://www.archivalplatform.org/blog/entry/orality_record_keeping_and_corruption_is_good_record_keeping_un-african/.

- Choo, C. W., Bergeron, P., Detlor, B., & Heaton, L. (2008). Information culture and information use: An exploratory study of three organizations. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(5), 792–804.

- Cinnamon, J. (2020). Attack the data: Agency, power, and technopolitics in South African data activism. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 110(3), 623–639.

- City of Cape Town. (2014). Open data policy.

- Crush, J. (1992). Power and surveillance on the South African gold mines. Journal of Southern African Studies, 18(4), 825–844.

- Cugurullo, F. (2018). The origin of the smart city imaginary: From the Dawn of modernity to the eclipse of reason. In C. Lindner, & M. Meissner (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to urban imaginaries. Routledge.

- Currie, M., & Hsu, W. U. (2019). Performative data: Cultures of government data practice. Journal of Cultural Analytics.

- Curry, A., & Moore, C. (2003). Assessing information culture—an exploratory model. International Journal of Information Management, 23(2), 91–110.

- Datta, A. (2015). New urban utopias of postcolonial India: ‘Entrepreneurial urbanization’ in Dholera smart city, Gujarat. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1), 3–22.

- Datta, A. (2019). Postcolonial urban futures: Imagining and governing India’s smart urban age. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(3), 393–410.

- Datta, A., & Odendaal, N. (2019). Smart cities and the banality of power. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(3), 387–392.

- Dencik, L., Hintz, A., & Cable, J. (2016). Towards data justice? The ambiguity of anti-surveillance resistance in political activism. Big Data & Society, 3(2), 1–12.

- Dominy, G. (2012). Overcoming the apartheid legacy: The special case of the freedom charter. Archival Science, 13(2), 195–205.

- Donovan, K. P. (2015). The biometric imaginary: Bureaucratic technopolitics in post-apartheid welfare. Journal of Southern African Studies, 41(4), 815–833.

- Edwards, P. N., & Hecht, G. (2010). History and the technopolitics of identity: The case of apartheid South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 36(3), 619–639.

- Fard, A. (2020). Cloudy landscapes: On the extended geography of smart urbanism. Telematics and Informatics.

- Garrib, A., Herbst, K., Dlamini, L., McKenzie, A., Stoops, N., Govender, T., & Rohde, J. (2008). An evaluation of the district health information system in rural South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 98(7), 549-552.

- Government Printing Works. (2013). The new South African ID - from ‘dumb pass’ to smart card. http://www.gpwonline.co.za/media/Pages/New-South-African-ID.aspx.

- Gray, J. (2014). Towards a genealogy of open data. Paper presented at the General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research, Glasgow.

- Han, H., & Hawken, S. (2018). Introduction: Innovation and identity in next-generation smart cities. City, Culture and Society, 121–124.

- Harris, V. (2000). They should have destroyed more': The destruction of public records by the South African state in the final years of apartheid, 1990-94. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 42, 29–56.

- Harris, V. (2002). The archival sliver: Power, memory, and archives in South Africa. Archival Science, 2(1-2), 63–86.

- Harris, V. (2009). Conclusion: From gatekeeping to hospitality. In K. Allan (Ed.), Paper wars: Access to information in South Africa (pp. 201–213). Wits University Press.

- Hecht, G. (2009). The radiance of France: Nuclear power and national identity after world War II. MIT Press.

- Hoyng, R. (2020). From open data to “grounded openness”: Recursive politics and postcolonial struggle in Hong Kong. Television & New Media.

- Joss, S., Sengers, F., Schraven, D., Caprotti, F., & Dayot, Y. (2019). The smart city as global discourse: Storylines and critical junctures across 27 cities. Journal of Urban Technology, 26(1), 3–34.

- Kennedy, H. (2015). Is data culture? Data analytics and the cultural industries. In K. Oakley, & J. O’’Connor (Eds.), The Routledge companion to the cultural industries (pp. 398–407). Routledge.

- Kennedy, H., & Bates, J. (2017). Data power in material contexts: Introduction. Television & New Media, 18(8), 701–705.

- Kgosana, R. (2017). Pretoria residents protest over smart ID cards. https://citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/1623149/pretoria-residents-protest-over-smart-id-cards/.

- Kitchin, R. (2014). The data revolution: Big data, open data, data infrastructures and their consequences. Sage.

- Kitchin, R. (2015). Making sense of smart cities: Addressing present shortcomings. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1), 131–136.

- Kitchin, R. (2019). The timescape of smart cities. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 109(3), 775–790.

- Lawton, P. (2020). Tracing the provenance of urbanist ideals: A critical analysis of the Quito papers. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(4), 731–742.

- Leidner, D. E., & Kayworth, T. (2006). A review of culture in information systems research: Toward a theory of information technology culture conflict. MIS Quarterly, 30(2), 357–399.

- Leszczynski, A. (2016). Speculative futures: Cities, data, and governance beyond smart urbanism. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(9), 1691–1708.

- Lindwa, B. (2019). Cape Town has been named Africa’s leading digital city. https://www.thesouthafrican.com/technology/cape-town-named-africas-leading-digital-city/.

- McDonald, D. A. (2008). World city syndrome: Neoliberalism and inequality in Cape Town. Routledge.

- McFarlane, C., Silver, J., & Truelove, Y. (2017). Cities within cities: Intra-urban comparison of infrastructure in mumbai, Delhi and Cape Town. Urban Geography, 38(9), 1393–1417.

- McFarlane, C., & Söderström, O. (2017). On alternative smart cities: From a technology-intensive to a knowledge-intensive smart urbanism. City, 21(3-4), 312–328.

- Milan, S., & Treré, E. (2019). Big data from the south(s): Beyond data universalism. Television & New Media, 20(4), 319–335.

- Mora, L., Bolici, R., & Deakin, M. (2017). The first two decades of smart-city research: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Urban Technology, 24(1), 3–27.

- Moultrie, T. A., & Dorrington, R. E. (2012). Used for ill; used for good: A century of collecting data on race in South Africa. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35(8), 1447–1465.

- Mörtenböck, P., & Mooshammer, H. (2020). Data publics: Public plurality in an era of data determinacy. Routledge.

- Ngoepe, M., & Ngulube, P. (2013). An exploration of the role of records management in corporate governance in South Africa. SA Journal of Information Management, 15(2), 1–8.

- Ni Loideain, N. (2017). Cape Town as a smart and safe city: Implications for governance and data privacy. International Data Privacy Law, 7(4), 314–334.

- Odendaal, N. (2016). Getting smart about smart cities in Cape Town: Beyond the rhetoric. In S. Marvin, A. Luque-Ayala, & C. McFarlane (Eds.), Smart urbanism: Utopian vision or false Dawn? (pp. 87–103). Routledge.

- Posel, D. (1999). Whiteness and power in the South African civil service: Paradoxes of the apartheid state. Journal of Southern African Studies, 25(1), 99–119.

- Posel, D. (2000). A mania for measurement: Statistics and statecraft in apartheid South Africa. In S. Dubow (Ed.), Science and society in Southern Africa (pp. 116–142). Manchester University Press.

- Ranchod, R. (2020). The data-technology nexus in South African secondary cities: The challenges to smart governance. Urban Studies.

- Republic of South Africa. (2000). Promotion of Access to Information Act, 2000. Government Gazette.

- Ricker, B., Cinnamon, J., & Dierwechter, Y. (2020). When open data and data activism meet: An analysis of civic participation in Cape Town, South Africa. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien, 64(3), 359–373.

- Sadowski, J. (2021). Who owns the future city? Phases of technological urbanism and shifts in sovereignty. Urban Studies, 58(8), 1732–1744.

- Sadowski, J., & Maalsen, S. (2020). Modes of making smart cities: Or, practices of variegated smart urbanism. Telematics and Informatics.

- SAHO. (2019). 20,000 Women march to the union buildings in protest of pass laws. https://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/20-000-women-march-union-buildings-protest-pass-laws.

- Savage, M. (1986). The imposition of pass laws on the African population in South Africa, 1916-1984. African Affairs, 85(339), 181–205.

- Seaver, N. (2017). Algorithms as culture: Some tactics for the ethnography of algorithmic systems. Big Data & Society, 4(2).

- Serlin, D. (2017). Confronting African histories of technology: A conversation with Keith Breckenridge and gabrielle hecht. Radical History Review, 2017(127), 87–102.

- Shelton, T., Zook, M., & Wiig, A. (2015). The ‘actually existing smart city’. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1), 13–25.

- Söderström, O., Blake, E., & Odendaal, N. (2021). More-than-local, more-than-mobile: The smart city effect in South Africa. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences.

- Stark, L., & Hoffmann, A. L. (2019). Data is the new what? Popular metaphors & professional ethics in emerging data culture. Journal of Cultural Analytics.

- Stelzner, A. (2015). City of Cape Town digital city strategy: The next phase of our smart city journey. https://acceleratecapetown.co.za/digital-cape-town-workshop/.

- Tarantino, M., Lokot, T., Moore, S., Rodgers, S., & Tosoni, S. (2019). Urban data cultures in post-socialist countries: Challenges for evidence-based policy towards housing sustainability.

- Thatcher, J., O'Sullivan, D., & Mahmoudi, D. (2016). Data colonialism through accumulation by dispossession: New metaphors for daily data. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34(6), 990–1006.

- The Archival Platform. (2015). State of the archives: An analysis of South Africa's national archival system, 2014.

- The Worldfolio. (2014). Cape Town is one of Africa’s most vibrant city destinations. http://www.theworldfolio.com/interviews/patricia-de-lille-executive-mayor-of-the-city-of-cape-town-south-africa-n3257/3257/.

- Valentine, S. (2004). E-powering the people: South Africa's Smart Cape Access Project. https://eric.ed.gov/?id = ED484726.

- van Wyk, T. (2020). Accessing information in South Africa. In K. Walby, & A. Luxcombe (Eds.), Freedom of information and social science research design (pp. 24–37). Routledge.

- Von Schnitzler, A. (2016). Democracy's infrastructure: Techno-politics and protest after apartheid. Princeton University Press.

- Watson, V. (2014). African urban fantasies: Dreams or nightmares? Environment and Urbanization, 26(1), 215–231.

- Watson, V. (2015). The allure of ‘smart city’rhetoric: India and Africa. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1), 36–39.

- Weaver, T. (2017). Urban crisis: The genealogy of a concept. Urban Studies, 54(9), 2039–2055.

- White, J. M. (2016). Anticipatory logics of the smart city’s global imaginary. Urban Geography, 1–18.

- Willmers, M., Van Schalkwyk, F., & Schonwetter, T. (2015). Licensing open data in developing countries: The case of the Kenyan and city of Cape Town open data initiatives. The African Journal of Information and Communication, 1626–1637.

- Wright, T. (2013). Information culture in a government organization. Records Management Journal, 23(1), 14–36.

- Yang, C. (2020). Historicizing the smart cities: Genealogy as a method of critique for smart urbanism. Telematics and Informatics.