ABSTRACT

In Malate, a district of Manila, flooding is a frequent occurrence. This paper draws on in-depth interviews with Malate inhabitants to approach urban floods as more than discrete disastrous episodes which interfere with a pre-existing normality. The paper employs a Levebvrian conceptualisation of rhythm and entrainment, while also offering reflections on the limits of its relevance to global South cities. Theorised from Malate, urban floods point to the mutual constitution of the social-technical-natural relations of urban infrastructures, and the on-going disruptive rhythms of floodwater. We argue that the rhythms of floodwater can be glimpsed at the intersections of different yet interrelated urban infrastructures. We focus on the infrastructures identified by research participants as pertinent to flood risk in Malate: drainage, waste management, and mobility. By tracing the spatial intersections and temporal rhythms of infrastructurally mediated urban floods, this paper contributes to scholarship on the situated hydrosocial relations of everyday life.

Introduction

Flooding in densely populated urban areas can severely undermine life, health, and livelihoods, with the most vulnerable groups typically most severely affected. Definitions of floods, including urban floods, typically refer to excesses of water which disrupt a pre-defined normality. However, framing floods as discrete and extraordinary disastrous events can lead to critical omissions, such as underappreciation of “minor” floods. Such floods may not meet quantitative definitions of disaster but be frequent and disruptive enough to give rise to recurring or continuous risk and hardship. In this paper, we draw on rhythmanalysis to conceptualize the infrastructural, intersections of frequent urban flooding. Infrastructural intersections are defined, following Carse (Citation2012) and Krause and Strang (Citation2016), among others, as the interactive and co-constitutive relations of the social, technical, and natural systems of urban life. We argue that, given the likelihood that flooding in many urban areas will increase in both frequency and severity as a result of climate change (Ajibade et al., Citation2013; Wilby, Citation2007), there is a pressing need to develop conceptualisations of urban flooding which better reflect its complex temporalities and interactions.

The paper aims to theorize urban flooding specifically as it is experienced in the low-income areas within Malate, a district of Manila, the Philippines. First, we seek to demonstrate that (a) urban floodwater is locally specific to the infrastructural relations of a place, in this case Malate, and (b) there are wider benefits of theorizing flood risk for and from specific urban locales that have remained less visible to Anglophone urban geography (Anand, Citation2017). We draw on ideas of rhythm, pace-making, and entrainment (Lefebvre, Citation2004; Parkes & Thrift, Citation1979), which allow us to trace floodwater through interconnected urban flows, and thus to demonstrate the spatial and temporal interlacing of everyday life and flood-related disruption. Approaching flooding through a processual lens, which brings to the fore simultaneity and intersection, provides an alternative to quantitative distinctions between absence of floodwater, minor floods and disastrous events. In spatial terms, we aim to demonstrate that flooding is not an external object only occasionally present in the “normal” intersections of urban infrastructures, entangled as it is in their materiality, shaping it and being shaped by it in turn. The paper contributes to a growing body of research in hydrosocial relations, which frames urban flooding as a phenomenon linked to but exceeding hydrology, highlighting the mutual constitution of social and hydrological relations (Batubara et al., Citation2018; Wesselink et al., Citation2017). Finally, the paper interrogates and extends the relevance of a rhythmanalysis framework to the political and spatial–temporal dimensions of urban flooding.

The next section summarizes existing work on flood risk, hydrosocial relations, and rhythmanalysis, on which we draw. We then provide an introduction to the research area and methods. In the three sections that follow, findings on the flood-affected rhythms of drainwater, domestic waste, and transport, are discussed in turn. The paper concludes with a discussion of the findings and their broader implications.

Theorising urban floods

Urban floods are often understood in generic and quantitative terms such as frequency, severity, number of people affected, and economic cost. Favored in disciplines such as hydrology and engineering, this perspective advances causes such as recording data, mobilizing aid, and international/historical comparison. However, many authors (e.g. Dunn et al., Citation2016; Linton & Budds, Citation2014; Pregnolato et al., Citation2017) have also suggested that this perspective limits conceptualisations of both cities and flooding. Not only does it privilege understandings of cities as containers in which floods happen, it also tends to compartmentalize floods into individualized and quantifiable events that may differ in the extent of disaster and disruption vis-à-vis some presumed “normal.”

At stake is a dual risk of underappreciation of how (urban) floods generate socially and spatially differentiated experiences and consequences, and an unhelpful dependence on dualistic conceptualisations such as normalcy versus disruption. Regarding the first issue, there is an extensive literature on/from cities of the global South which emphasizes the profound urban inequalities along lines of gender, income, race, age and disability in how vulnerabilities to, and experiences of, flooding are continuously constituted in social-technical-natural relations (e.g. Adger, Citation1999; Ajibade et al., Citation2013; Batubara et al., Citation2018; Sultana, Citation2010). For Metro Manila, Zoleta-Nantes (Citation2002, Citation2007) has explored the ways in which different social groups’ vulnerability to various hazards is highly uneven, reflecting differentiated underlying sensitivity and resources. In attending to differentiated flooding experiences in Malate, where many live on very modest and uncertain incomes, we further follow the work of Anand (Citation2011) in aiming to avoid rigid distinctions between the “haves” and “have-nots” of urban water management. As Anand demonstrates, such binaries undermine efforts to think relationally about the mutual constitutions of floodwater and urban infrastructural relations. Relatedly, we draw on research on subaltern urbanisms in our effort to explore flood-related phenomena which are experienced as a result of, or are amplified by, poverty, without trivializing flood risk through celebrations of the resilience and ingenuity of urban dwellers (see also Roy, Citation2011). There are similarly sound reasons to be sceptical of a normalcy versus disruption dualism. Sultana’s (Citation2010) research on the gendered implications of flooding in Bangladesh already highlighted the importance of problematizing the separation of disruption from normality. In the context of the Philippines, a study by Delfin and Gaillard (Citation2008) on flooding and volcanic activity on Luzon Island has demonstrated that for many inhabitants the distinction between calamitous and everyday events is unhelpful. The authors argue that focusing instead on their connectedness allows research to highlight the way particular hardships are amplified in the presence of disruptive forces.

Grasping the societal, political, and technological implications of how calamitous and everyday events are interconnected requires a relational understanding of their enactment. We offer this by drawing on an expanding body of research on hydrosocial relations. Its growing importance, in dialogue with socio-hydrology, has made visible the ways in which people, watery matter and local environments continuously shape and reshape each other (Di Baldassarre et al., Citation2013; Krause & Strang, Citation2016; Ross & Chang, Citation2020). The hydrosocial framework generally conceptualizes infrastructures and water as mutually constitutive within complex social, political, technical and natural relations, a definition we also follow for the purposes of this paper. This approach has informed analyses of social-technical-natural practices, from agricultural policy-making to dam construction, as integral to hydrological cycles (Nüsser & Baghel, Citation2017). Applied to flood risk, the study of hydrosocial relations has highlighted the extent to which individuals and groups in a flood-prone area continuously respond to the material and discursive dimensions of floodwater, while water and infrastructures are themselves active and interconnected agents with specific local characteristics (Krause, Citation2013, Citation2016; Krause & Strang, Citation2016). For instance, from one day to the next or between adjacent areas, floodwater can shapeshift, from a menace to a beneficial resource to be captured for food growing (Cousins, Citation2017).

In the study of rural floodplains, there are long-standing traditions of differentiating between regular seasonal flooding which is beneficial to agriculture, and disastrous flooding events (see Sultana, Citation2010). Developing a more nuanced understanding of urban floodwater brings together research on floods as heterogeneous, with political ecology research on diverse types of urban water (Anand, Citation2012; Bakker, Citation2013; Cousins & Newell, Citation2015; Ekers & Loftus, Citation2008; Gandy, Citation2004, Citation2008; Misra, Citation2014). The resulting framing of urban floodwater emphasises the role of the locally specific, dense, interconnected and infrastructurally mediated relations of urban flooding. While there are many urban infrastructural networks relevant to flood risk, three in particular featured prominently in our interviews with local inhabitants: household waste disposal; drainage; and transport. The main part of the paper is therefore structured around these three themes.

Bringing together flood-related disruption and the intersection of infrastructures in our conceptual framework requires close attention to both the spatial and the temporal aspects of flooding and everyday life. The temporal dynamics of flooding can be conceptualized in terms of on-going hazards, repeated inundations, and individual events. However, local social, technical, and hydrological relations do not pre-date flooding events; floodwater is ever-present, whether as substance, or through the practices local inhabitants undertake in anticipation of, or in response to, flooding. As noted by Walker et al. (Citation2011), floods are emergent before they are emergencies. A relational conceptualisation of urban floods thus requires moving away from binary views of temporality such as daily life/flood, and rejecting the assumption that each is defined by the absence of the other (for a related argument in the context of other forms of disruption, see Ranganathan, Citation2015; Trovalla & Trovalla, Citation2015). Rhythmanalysis offers one possible conceptual vocabulary, as it uses rhythms to draw attention to the way diverse social, natural and technical elements can coalesce or clash in the constitution of everyday life (Cresswell, Citation2010; Edensor, Citation2010; Gibert-Flutre, Citation2021; Lefebvre, Citation2004; Reid-Musson, Citation2018). Importantly, rhythms are made up through repetition, but also contain within them the uniqueness of each rhythmic element, which changes at the same time as it repeats, with change and repetition making up an indivisible whole (Blue, Citation2017; Lefebvre, Citation2004; Schwanen et al., Citation2012). This approach allows us to highlight the recurring nature of urban floods in the study area, but also the ways in which each flooding event, from the disastrous to the “minor,” has particular characteristics, producing different impacts and requiring continuous adjusting of preparedness and response. As part of the polyrhythmia of an urban area, repeated and different excesses of floodwater can be thought of in terms of the now famous Lefebvrian metaphor of the sea tide, in which small waves share and reinforce an overall orientation towards the shore, but also always differ and deviate from it (Blue, Citation2017; Lefebvre, Citation2004). Thus, the rhythms of flooding are not simply a sequence of presences and absences – floodwater keeps coming back but is never the same, and its disruptive rhythms penetrate the urban infrastructural rhythms even in dry times.

Lefebvre’s work, which itself builds on Gaston Bachelard’s earlier writings on rhythmanalysis, is embedded in the historical context of industrial capitalism in twentieth century France. We are therefore wary of its wholesale transplant to a different locale and set of concerns, and especially of the ethical and political implications of overstating its explanatory power in a contemporary urban global South context. At the same time, we are sympathetic to Gibert-Flutre’s (Citation2021, page 14) suggestion that rhythmanalysis can contribute to the development of “cosmopolitan theoretical framework[s] from the perspective of the “Southern turn”” in urban theory. This is why we adopt the notion of floodwater as a pacemaker (Parkes & Thrift, Citation1979) shaping social and political arrangements, technical systems, and hydrological flows in Malate. This is also why we draw on ideas and concepts associated with rhythmanalysis to investigate the interconnectedness of flooding and everyday events in Malate, the politics and power dynamics involved, and the social inequalities that are thus consolidated or created.

Research area and methods

The discussion presented below is based on data collected during September 2016 in Malate, one of the six districts of the city of Manila in the National Capital Region of the Philippines (Metro Manila). Malate has been growing and densifying through natural population growth and internal migration, reaching 77,513 in 2010, or approximately 5% of the total population of the City of Manila (National Statistics Office of the Philippines, Citation2010). The total population of the capital metropolitan region is estimated to be around 12 million.

The part of Luzon Island where Metro Manila is located is exposed to significant risk of flooding throughout the rainy part of the year, influenced by the East Asian monsoon (May to October). Along with climate, the topography of the metropolitan area and its infrastructural fabric shape flood risk in Metro Manila (Abad et al., Citation2020; Bankoff, Citation2003; Jha et al., Citation2012). Tropical cyclones are a frequent occurrence, with run-off from less intensive storms representing another significant flood risk. This is exacerbated by the location of the urbanized area on the isthmus between Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay, a large floodplain, which is criss-crossed by several rivers and modified streams known as esterosFootnote1 (Bankoff, Citation2003; Lagmay et al., Citation2017). Thus, flood risk is the result of the interaction of natural, social, and technical systems, with national and city-level policies often leading to a worsening of flood risk, due to over-reliance on purely engineering-based strategies or short-term disaster responses (Rodolfo & Siringan, Citation2006; Zoleta-Nantes, Citation2002).

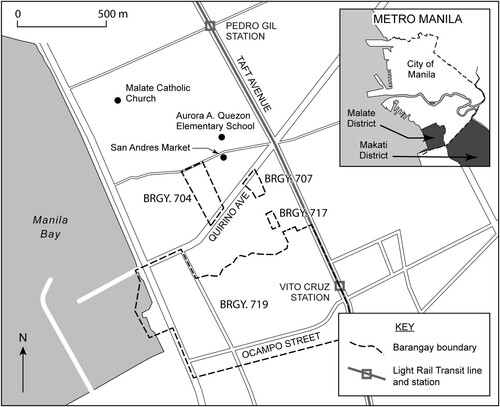

The district of Malate is a diverse area, with housing ranging from new apartment condominiums housing university students and middle-income inhabitants to neighborhoods constructed by lower-income households with own efforts on previously vacant land (). As part of a wider research project focused on the impact of flood risk on the everyday mobilities of older women,Footnote2 we conducted 32 interviews with long-term inhabitants of lower-income parts of Malate, which are also the areas most heavily affected by flooding. All research participants were women, had lived in Malate for 20 years or more and had extensive knowledge of the area’s exposure to flooding. Many shared distressing accounts of destroyed houses and evacuation, notably during the major flood caused in 2009 by tropical storm Ondoy.Footnote3 Despite the limitations and omissions of researching only with locally living women, this focus has enabled us to gain in-depth insight into the impact of flood risk across paid work, unpaid domestic work, and childcare (see also Ajibade et al., Citation2013).

Figure 1. Location of barangays 704, 707, 717, and 719 within Malate and Manila. The map indicates key roads and destinations within Malate, as well as the adjacent district of Makati to which many Malate inhabitants travel regularly.

Interviews were conducted in four of Malate’s 57 barangaysFootnote4 selected through the outreach office of De La Salle University. As partners on the wider research project and due to their location in Malate and extensive community outreach work, our colleagues from the De La Salle University Engineering Department played a critical role in selecting the research sites, recruiting participants and generating relationships of trust between the research team and participants. The four barangays we visited vary in their size, connections to transport and facilities, and prevalence of permanent versus temporary house-building materials. However, all can be considered “popular neighbourhoods”, populous centres of social life at the economic margins in a city where lower-density living in more expensive dwellings is out of reach for the vast majority (McFarlane & Silver, Citation2017). All also trace their origins to inhabitants’ home-building mobilisations on previously vacant land, which started in response to severe shortages of affordable housing in the 1970s. While the social and economic status of inhabitants of the same barangay can vary widely, these four areas represented the relatively poorer part of the district, and faced shared challenges such as a recent surge in drug-related crime, often intensified rather than quelled by the clandestine police operations forming part of President Rodrigo Duterte’s violent crackdown on narcotics (Thompson, Citation2016). In addition, the four barangays had experienced high population growth, leading to widespread residential overcrowding and reduction of public spaces (see Bicksler, Citation2019, on flood risk and infill development in Chiang Mai). The barangays are governed by an elected council charged with managing the area’s modest budget provided by central government, and responsible for tasks such as organising street cleaning and flood prevention and response.

A total of seven interviews were conducted in Barangay A, 10 in each of Barangays B and C, and 5 in Barangay D. Additional interviews were conducted with people with a professional stake in issues of flooding, including five barangay council members (this included the two women in the main sample who were also working as councilors), and one civil engineer from De La Salle University. Interviews were conducted in Tagalog and English, with field assistants from De La Salle University interpreting and providing subtle direction whenever they felt our sensitivity to local cultural specificities could be improved. In the rest of the paper, pseudonyms are used to identify participants, and the capacity in which they were interviewed is indicated.

The rhythms of drainwater

The barangay was founded in the late 1970s or early 1980s. Before, there was no drainage. Can you imagine what it was like? Flooding! I experienced my first floods in the 1970s, right here. Neck-deep!Footnote5 And you could see people using wooden kayaks. We don’t experience that now. (Ferdinand, barangay council member in Barangay A)

Flooding in Malate is frequent, but the spatial and temporal extent of flooding events can vary greatly even within this small area of approximately 3 km2. Floodwater may reach only specific streets, or sections of streets; enter some homes in an area, but not others; subside within 30 min in one barangay, and linger for days as stagnant pools in the adjacent one. These differentiated spatial and temporal patterns of flooding reflect the uneven and unpredictable rhythms created by drains and their flows. Wastewater in Malate, a mix of local and regional run-off rainwater and domestic sewage, flows in rhizomatic ways, and not as the disciplined streams envisaged by municipal engineers, moving along drains into Manila’s estero system and ultimately into Manila Bay. Just like the houses and neighborhood facilities at ground level, the drains beneath Malate reflect a history of incremental, often improvised expansion. A patchwork rather than an integrated network, the drainage combines small-scale solutions implemented over decades in adjacent neighbourhoods, in response to newly arising problems and using scarce resources.

The first drains were installed by the inhabitants in the 1970s and 1980s, when each barangay had to organize to connect their own drains to the larger drainpipes in Malate’s main roads:

In the 1970s, there was already drainage in [Quirino Avenue], but we had to build our own and connect it. The government financed it through the barangay budget. [At that time], we had a little less than 2,000 people; now it’s 7,000. (Ferdinand, barangay council member in Barangay A)

While frequent flooding in Malate is often attributed to heavy rainfall during the monsoon, floodwater is not simply an excess of rainwater. The materiality of what becomes experienced as floodwater is formed when it first fills local drains, and then overwhelms them. As the mix of rainwater and drainwater is forced up into the street, both water and street are changed. As summed up by one local resident, “[floodwater] comes out of the ground, and it’s dirty.” The color and contents of floodwater reflect the disrupted flows of the drainage, and are defined by the mixing with waste inside overwhelmed drains:

I went to the market, and suddenly the rain poured and there was flood. The water was pitch-black. It was really dirty. I had no other choice but just to go [through it]. (Liliana, Malate homemaker)

As the opaque mix of rainwater and drain water rises in a street, anyone having to traverse it faces risks beyond drowning, e.g. infectious disease, sharp objects such as nails, unsecured electric cables, and open manholes. One way, then, through which heavy rain and flooding entrained the rhythm of everyday life – that is, impelled and inflected it to follow the water’s spatiotemporal dynamics (Parkes & Thrift, Citation1979) – consisted in the frequent navigation of the risks of watery streetscapes.

Flood-related health risks in Malate followed a diverse set of hydrosocial rhythms, of which the surge and subsidence of floodwater is but one. For instance, health risks and their management were also constituted in connected, but separate institutional rhythms (Blue, Citation2017). An important example of these were the cyclical rhythms of metropolitan authority and public health NGOs awareness-raising campaigns, often taking the form of leptospirosis awareness workshops. Leptospirosis is a bacterial infection the spread of which is often linked to rats and other rodents, particularly around stagnant water (Bharti et al., Citation2003). The symptoms can range from mild to severe, and levels of associated mortality can also vary substantially. The institutional focus on leptospirosis meant many research participants described it as the principal flood-related health risk. In addition, participants often had detailed knowledge of its symptoms and officially endorsed prevention measures such as avoiding floodwater and washing hands. The rhythms of health promotion were thus part of the social-technical-natural rhythms of flooding, shaping local inhabitants’ practices around floodwater, but also giving rise to additional frictions within these rhythms. A main reason for this were the disjunctions between the official advice and the functioning of Malate’s multiple, intersecting, and often over-stretched, infrastructures. For example, clean water for hand washing was often scarce in the presence of floodwater. Similarly, many inhabitants had no choice but to continue working and performing care duties, and thus entered flooded areas despite knowing the associated risks. The resulting dangers to health were also amplified by diurnal rhythms, since many of the jobs available to Malate inhabitants involved returning home after dark, when traversing floodwater was even riskier:

I got stranded at work, so I had no choice but to walk through the flood. Before going to work, the water was just above the ankle. However, during the day, the water went up and reached waist-deep. So I had no choice but to walk home in waist-deep water. (…) Every time I made a step, I did it very slowly, checking where I was stepping. This was at 10pm. It was completely dark. There were a lot of people in the street, a lot of workers, because many got stranded. (Jasmine, currently homemaker in Malate, previously clerk in an employment agency in Makati)

Thus, a process of reciprocal entrainment emerged, with flooding disrupting and modifying the rhythms of what may otherwise be thought of as “normalcy”, which in turn shaped the rhythms of encountering floodwater. These intricate hydrosocial relations reflected to some extent the presence, absence, and condition of drainage in different Malate streets, but this relationship was neither singular nor stable. One reason for this was that the rhythms of the drainage network itself, its capacity and flows, frequently underwent adjustments through local flood management strategies that sought to inflect water flows and runoff. For instance, aiming to reduce contact with dirty and hazardous drainwater, some Malate residents blocked the holes of the drain covers outside of their homes. This practice ensured that the area surrounding the home, while still flooded and potentially more so, would not be filled with sewerage water. One barangay official explained:

On the side streets, you are supposed to see holes in the gutters, and these holes are supposed to lead to the drainage. Some people in the other barangays have blocked these holes already, because sometimes due to excessive water inside the drainage, the water coming from Quirino Avenue can come up through these holes and cause more flooding in the barangays.

So, the water would rise very fast. Because these holes are supposed to lead the flood water to the drain, but at the moment it is working in reverse – there is too much water inside, so the water is coming out. But it also means the holes are blocked and there is no way for the rainwater to drain. (Daniel, barangay council member in Barangay B)

In the quote above, the speed with which water rises is a critical factor, reiterated by many of the research participants in their interviews. People who had lived in Malate for an extended period of time tended to have detailed and embodied knowledge of flood speeds in specific areas. They were, for example, able to judge how quickly the water was likely to rise above knee-level in a particular street, by observing the rainfall on the day. The most distressing and dangerous situations often reflected not just the depth of the water or the total amount of rainfall, but floodwater depths increasing at a different speed to what was expected. The repetitive rhythms of flooding were thus also rhythms imbued with difference. Their negative impacts on daily life were consequence not only of the material properties of floodwater, but the interplay of recurrence, learning and unexpectedness which defined frequent flooding.

The barangay official quoted above may have framed the deliberate blocking of drains as the disruption of the intended functioning of drainage infrastructure by local inhabitants. From the perspective of many households, however, floodwater was a disruptive rhythm which amplified, and rendered hazardous, the already-disrupted rhythm of unreliable drainage flows. For those inhabitants sealing the holes of drain covers, it was the drainage that posed a problem. From their perspective, preventing drain water from mixing with surface-level water constituted an effective local flood management strategy. As argued by Krause (Citation2016) in the case of flood-affected Gloucestershire in the United Kingdom, one household’s defences against floodwater often exacerbates the problem for another, especially for those living further downstream, provoking them to act, in turn, in ways which modify the landscape and flood risk. While local officials in either Manila or Gloucestershire may be inclined to read such practices as selfishness or ignorance, those engaging in them often do so in circumstances of peril and shortage of alternatives. The next section explores this argument further in relation to the disposal of household waste in Malate.

Accumulation and removal of household waste

Intentionally blocking the flow of runoff water through obstructing drain holes had divided opinions in Malate in terms of its impact on flooding. What residents and local experts tended to agree on was that, for the most part, drains were not blocked intentionally, but rather became obstructed through gradual accumulations of household waste (see also Bernardo, Citation2008). Despite the consensus on the link between discarded domestic waste and flood risk, rubbish continued to find its way into the drains in large quantities. In response to our questions on household and collective waste management practices, some of our interviewees pointed to a perceived unwillingness to dispose of unwanted objects “correctly”:

The garbage is the main reason for flooding here. There are people who just throw the garbage everywhere. (Maria, Malate street vendor)

AP: So why do people throw their garbage in the drain?

Ferdinand: I don’t know. Filipino style. Laziness and not thinking about the surroundings. (Ferdinand, barangay council member in Barangay A)

In other cases, the clogging of drains with domestic waste was blamed not on an overall Filipino attitude, but on the carelessness of specific ethnic groups and recent migrants from rural areas. However, we found these explanations doubtful. Firstly, it was clear that blocked drains were recognized as a flood risk by all inhabitants with whom we spoke irrespective of their background. Secondly, previous research on life in densely populated low-income areas in the Philippines has mostly found a strong spirit of interdependence, mutual help, and responsibility for community concerns (Asis, Citation2006; Peterson, Citation1993). Instead, examining the rhythms of interdependent infrastructural floodwater rhythms in Malate pointed to specific social-technical-natural processes of entrainment between waste accumulation and overflowing water.

Residential waste in Malate was collected by municipal trucks at designated points along the main roads. In parts of the area, the waste collection timeslot had recently been shifted from 7am to anytime between midnight and 5am. While wealthier parts of Malate were able to pay a private company to organize waste disposal, the limited economic means of households in the study areas meant the free nocturnal service of the Municipality was the only available option. At the same time, municipal regulations required that local inhabitants took out their household’s waste upon the arrival of the truck and not in advance:

It’s at 3 o’clock at night that the garbage truck drops [by]. When the truck arrives, the barangay rings a bell to announce to the people that there will be garbage collection and people go take their garbage. (…) While the people are asleep, the bell rings and they get woken up to take their garbage. (Rose, barangay council member in Barangay C)

The rhythm of listening out for the waste truck bell, and getting up to take out the garbage, was in itself a disruptive intervention in diurnal cycles. But for many people in Malate, these rhythms were also defined by very long working hours and extremely long commuting times. The latter were frequently associated with Manila’s notorious traffic congestion, in which a jeepneyFootnote6 could take hours to travel a relatively short distance, for instance to employment opportunities in the nearby wealthy Makati area. While we explore transport in more detail in the final empirical section, it is important to highlight here the ways in which the problematic rhythms of commuting and waste collection combined to direct domestic waste towards Malate’s drains.

As a result of the unsociable hours of waste collection, some households defied regulations and took out rubbish bags in advance. By the time the truck arrived, waste left in the street had been sorted through by the poorest local residents looking for sellable recyclable materials. Any rubbish which got dispersed in the process was not collected by the municipal waste trucks.

An additional disruption to waste collection rhythms was created by the requirement for households to separate waste into compostable, recyclable, and non-recyclable materials (Aquino et al., Citation2013). For many Malate households, this requirement came up against an unsurmountable problem of residential overcrowding:

The [waste] segregation is hard to commit [to], because there is limited space, so it’s hard to segregate. (Karen, Malate homemaker)

In recent years, Malate households with limited incomes had found themselves sharing more and more restricted living spaces. There were acute shortages of available home space, with multiple adverse implications for livelihoods and well-being, one of which was that collecting recyclables in a separate receptacle could become an impossibility (also discussed by Bernardo, Citation2008, in her study of household waste practices in Sampaloc, north-east of Malate). As waste truck drivers could refuse to collect domestic waste which had not been separated, unwanted objects ended up in the drains, and not as a result of a careless attitude. Together with sleep deficits and truck schedules, the challenges of waste segregation pointed to a complex entanglement of infrastructural rhythms. Notably, poverty shaped, and was itself further entrenched, within these polyrhythmic assemblages, as the households’ limited options for dealing with domestic waste amplified its disruptive impact on hydrosocial relations, which in turn intensified flooding-related hazards.

The low local tax base accounted to some extent for the limited involvement of the city government in the cleaning of drains. Each Malate barangay council received funding approximately twice per year to carry out drain declogging campaigns. Carrying out these two interventions was an obligation which the barangays we visited diligently fulfilled:

We have two declogging projects every year. We clean the drainages – we buy some sacks, we open the covers and some people would clean out the drainage, including the soil and the garbage. Then they would dump the garbage. They use a shovel. All the drainage system. (Ferdinand, barangay council member in Barangay A)

According to both local council representatives and residents, the efforts made by barangays to clean the drains made a substantial difference. However, in the declogging programmes organized by local barangays, just like in the case of residents blocking drain covers to prevent drainwater from rising, the significance of spatial and temporal frictions within hydrosocial relations once again emerged. Each barangay carried out its own declogging programme as and when funds were disbursed to them, and not in coordination with adjacent neighbourhoods. Thus, while the rhythms created by domestic waste and floodwater exceeded administrative boundaries, drain cleaning was a bundle of a-synchronous institutional rhythms constrained within barangay borders (see Blue, Citation2017 on the entrainment of rhythms into institutions):

This is actually what we would like to happen. We want the declogging to occur simultaneously in different barangays. Because even after we clean our drainage, the garbage from their barangays will go down to our barangay. [However] we cannot tell them what to do. (…) The budgets do not get released at the same time. Sometimes the city government will give us our budget – “Ok, now you can do a declogging.” The other barangay is still waiting for their budget. (Daniel, barangay council member in Barangay B)

So far, we have identified three sets of rhythms, or three pace-makers (Parkes & Thrift, Citation1979), which act in a discordant manner to produce a treacherous interconnection between household waste and dangerous water: unsynchronized declogging programmes; struggling to separate recyclable waste at home; and the problematic timings of otherwise regular municipal waste collection. This is not a case of either household waste or rainfall “disrupting” a normality of floodwater absence; we argue that these relations are more helpfully understood in terms of co-constitution and on-going interrelatedness. Following Gibert-Flutre (Citation2021, page 14), we have also seen how the rhythms of declogging and garbage collection have “political underpinnings” and are both constitutive and reflective of social inequalities in Malate and Manila. The final empirical section extends these arguments to the rhythms of mobility and transport.

Flood-prone human mobilities

For the inhabitants of Malate, commuting to workplaces located in the rest of Manila could often take two hours each way. For example, the neighbourhood of Makati is both nearby and wealthy, and thus an important source of employment opportunities in the retail, catering and cleaning sectors (City Government of Makati City, Citation2013). However, the roads which link the two districts of Malate and Makati were often overwhelmed by traffic. Thus, for the inhabitants of the research area who had been able to find paid work, everyday mobilities were not either unobstructed or obstructed, but represented a diversity of modes of being slowed down, with lengthy, exhausting and quite unpredictable journeys even in dry weather:

I used to ride a jeepney to work [in Makati]. With traffic, it’s about one hour. The traffic is really bad. My workplace was very difficult to get to, because it was on the way to Makati. So I was often late (…). Sometimes, when I travelled by jeepney, the traffic in Taft Avenue was so crazy, that I would just get off the jeepney and walk. (Jasmine, currently homemaker in Malate, previously clerk in an employment agency in Makati)

For those working in Makati, a small flood along the roads did not interrupt the rhythms of the daily commute but acted to amplify frictions already present. Local trips within Malate were also affected by floodwater in various ways, especially if they involved use or crossing of the main arteries of Taft Avenue, Quirino Avenue, and Ocampo Street. During heavy rain, the major roads were among the first areas to be inundated, and were the most likely to experience deep floods which lasted for many hours. Major inundations brought the rhythms of traffic along the main roads to a complete standstill, but “minor” accumulations of water generated various effects. Smaller floods modified some journeys (e.g. where jeepneys deviated from their routes in search of passage), slowed down others, particularly those of pedestrians, but also amplified yet others (e.g. for modes such as pedicabs, seen by many as a flood-resistant alternative to motorized vehicles). Yet exacerbated congestion was a common cumulative consequence:

Flooding causes traffic. Especially for [our grown-up] children, who [attend De La Salle University] in Taft Avenue. The normal time they arrive [home] is 7pm, [when there is flood] they arrive at 9pm, because it’s so hard to [board] a jeepney. (Alyssa, school clerk and Malate inhabitant)

In this context, crossing or moving along Malate’s main roads on dry days and days of “minor” floods did not constitute fundamentally different experiences, but interrelated and mutually constitutive ones.

Nonetheless, the entrainment of road rhythms was experienced differently for different road users, times, and activities. For instance, the nocturnal waste collections took place along the neighbourhood’s main roads: Taft Avenue, Quirino Avenue, and Ocampo Street (). Many of these roads suffered from severe traffic congestion from early morning to late evening. According to local barangay officials, the rescheduled waste collection was part of the city authority’s efforts to free up road space for daytime traffic. Similarly, flooding in Malate was mostly seen as a pressing issue by city authorities because of the disruption to main-road traffic it caused. In times when one or several of the major roads were flooded, traffic congestion on the rest of the road network became even more severe than usual, causing discontent among car drivers and the elected officials who relied on their votes. Recurrent floods were thus one pace-maker of the on-going disrupted rhythms of slow traffic, which in turn determined the priorities of official responses to flood risk. This was illustrated in the account of a recent project to lay a higher capacity drainpipe, nominally intended to alleviate flooding in one of the barangays:Footnote7

The old drainage is still here … [The new drainage] was a project of a Congressman.Footnote8 One new large pipe, one meter in diameter, going through the neighbourhood. It’s made of concrete. The new drainage was just laid on top of the old pipes. In fact, I think the old drainage is even better than the new drainage … After the new drainage was put in, that’s when it started flooding in this area. Before that it didn’t really flood … But now, if it rains just a few minutes, we will already see a little bit of flood … Maybe they [put in the new pipe] just in order to solve the flooding in Quirino Avenue, so that the water from there can flow down to the estero.

This interview quote highlights a particular politics of risk management: the involvement of the Congressman in organising the installation of a new pipe had little to do with alleviating flooding inside the residential area, instead constituting an attempt to reduce the impact of flooding on traffic in Quirino Avenue. It was, in other words, a deliberate attempt to immunize the privileged rhythms of a main road by decoupling them from the rhythms of the surrounding barangay. The barangay was not a community to be served by better drainage, but a territory to be crossed by a pipe: “higher priority” floodwater would fill the pipe at Quirino Avenue even before it reaches the barangay (see also Mustafa, Citation1998, for a related discussion of infrastructure initiatives in Punjab, Pakistan, which have redistributed flood risk instead of alleviating it). This intervention made visible not only the political underpinnings of the rhythms of intersecting infrastructures in Malate but also the frictions between the various, complex and often contradictory modes of state intervention in the flood risk in the area (see Neves Alves, Citation2021; Ranganathan & Balazs, Citation2015 on the co-constitution of water infrastructures and government water management practices). Floodwater may be pervasive but its rhythms affect constituencies and sites differently and in ways that consolidate broader power dynamics. Its displacement from a major road to a local neighbourhood followed, and amplified, a broader history of displacement. This has included the razing of low-income housing for condominium development; violent over-policing in the so-called “war on drugs” of Duterte; and repeated efforts to free up road space for cars by removing “unsightly” pedicabs (Choi, Citation2016; Clapano, Citation2016).

Hydrosocial relations in Malate thus took a particular shape when considered from the perspective of the rhythms of the district’s main roads. Directing attention to those rhythms – and the humans, vehicles, waste collection trucks, domestic waste, pipes, and floodwater, implicated in them – allows us to foreground three relationally constituted conditions for everyday life in Malate. These are the frictions of hydrosocial entanglement which cannot be reduced to normalcy punctuated by intermittent inundation; the ways in which floodwater created, modified, and fragmented the intersections of infrastructural systems; and the politics of prioritizing some rhythms and livelihoods at the expense of others.

Discussion and conclusion

Framing the rhythms of floodwater as integral to intersecting infrastructures contrasts with notions of urban infrastructural systems as defined by continuous and predictable, if heterogeneous, rhythms. To acknowledge that disruptive rhythms are not external to urban infrastructures is to render visible specific questions on the governance of vulnerable urban systems. For instance, by tracing the interdependent social-technical-natural processes through which recurrent urban flooding is continuously constituted in Malate, we have shown how floodwater is a near-constant menace. Barangay officials and inhabitants are acutely aware of this and manage floodwater accordingly, with its governance high on the agenda even when floodwater is minimal or absent. One example of this are the collective operations to declog drainage channels and the blocked drainage holes discussed above. It is an obvious point that metropolitan- and national-level authorities could support declogging programmes, particularly in poor barangays, with more frequent cash transfers. However, the discussion of rhythms has highlighted the importance of also synchronizing the release of funds between barangays, in order to increase the effectiveness of their declogging programmes. Similarly, the timing of waste collections and promotion of politically salient drainage upgrading projects may be complex issues where multiple agendas and priorities clash; but their role in exacerbating frequent flooding could be made much more visible. Qualitative and contextual conceptualisations of the impact of flooding on urban populations of the kind developed in this paper can be used to empower citizens in popular neighbourhoods and to put pressure on authorities in cities like Manila where a “largely decentralized and privatized urban governance regime is perpetuating a fragmented and unequal city, which may undermine urban climate resilience” (Meerow, Citation2017, p. 2647).

Bringing together ideas and concepts on rhythms, hydrosocial relations, and infrastructural intersections, this paper has sought to demonstrate that flooding extends beyond discrete events with disastrous consequences to affect most spheres of everyday life in flood-prone urban areas. In Malate, floodwater can amplify the flow of drainwater or disrupt it, interfere with traffic congestion, and impact the way domestic waste is managed, while at the same time defining the flows which render these rhythms visible, palpable, and knowable. In turn, the rhythms of waste, drains and transport can entrain, amplify, modify, or obstruct the flow of floodwater, changing the social and spatial distribution of flood risk. In other words, floodwater impacts in locally specific ways and interacts with social-technical-natural systems, which it changes while itself becoming changed.

Our focus on the place-specific interplay of floodwater and the intersecting infrastructures of drainage, domestic waste and transport functioned as a means to achieve a dual end. On one hand, we have sought to demonstrate the necessity for situated conceptualisations of urban flooding which have relevance to the experiences of local inhabitants. On the other hand, we have intended this engagement with floodwater in Malate as a contribution towards urban theory which speaks to the governance of intensifying hazards globally, while maintaining an orientation towards specific urban areas in the global South. Theorising from local experiences of flooding aims to address the blind spots arising from binaries such as normalcy-disruption, dominant as they are in contemporary research on infrastructural intersections (cf. a recent special issue edited by Monstadt & Coutard, Citation2019; see also Schwanen & Nixon, Citation2019). Thus, while our discussion is limited to those types of social-technical-natural interactions which are especially pertinent to Malate, the paper invites further work on the locally specific hydrosocial rhythms of flood-prone urban areas.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the research participants and the field assistants who guided us in the development of these ideas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Esteros are rivulets which were modified into canals during Spanish colonial rule. Over 30 esteros were constructed to provide flood defence and transportation. However, the functions of many Manila esteros have changed more recently with the city’s poorest residents using their banks for housing construction. As the flow of water has gradually become obstructed, esteros are now more likely to contribute to urban flooding than to alleviate it.

2 The everyday mobilities of older women, particularly older women with lower incomes, no access to a private car, and/or living in the global South, remain understudied. For more information on how this research project conceptualised and studied them, see Plyushteva and Schwanen (Citation2018).

3 Tropical storm Ondoy, known internationally as Typhoon Ketsana, caused a total of 715 deaths in 2009, of which 501 in the Philippines (Asian Disaster Reduction Centre 2011).

4 Barangay is the smallest administrative unit in the Philippines. They are identified by numbers in Malate, but have been anonymised here.

5 An embodied vocabulary (ankle-deep; knee-deep; waist-deep; chest-deep; neck-deep) is often used in Manila to describe the severity of flooding episodes. While we acknowledge that the great diversity of bodies in terms of age, height and disability is not captured in this lexicon, this vocabulary is particularly helpful in evoking the close entanglements of human-watery relations in Malate.

6 Jeepneys (also jeeps) are minibuses with fixed routes serving the public. Jeepneys can be repurposed military trucks, or custom-made locally using second-hand diesel engines. They are often decorated with distinctive designs.

7 No details about the respondent accompany this quote so as to ensure that they cannot be identified.

8 The Congress of the Philippines is the national legislative body.

References

- Abad, Raymund Paolo B., Schwanen, Tim, & Fillone, Alexis M. (2020). Commuting behavior adaptation to flooding: An analysis of transit users’ choices in Metro Manila. Travel Behaviour and Society, 18(January), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2019.10.001

- Adger, W. Neil. (1999). Social vulnerability to climate change and extremes in coastal Vietnam. World Development, 27(2), 249–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00136-3

- Ajibade, Idowu, McBean, Gordon, & Bezner-Kerr, Rachel. (2013). Urban flooding in Lagos, Nigeria: Patterns of vulnerability and resilience among women. Global Environmental Change, 23(6), 1714–1725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.08.009

- Anand, Nikhil. (2011). PRESSURE: The PoliTechnics of water supply in Mumbai. Cultural Anthropology, 26(4), 542–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2011.01111.x

- Anand, Nikhil. (2012). Municipal disconnect: On abject water and its urban infrastructures. Ethnography, 13(4), 487–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138111435743

- Anand, Nikhil. (2017). Hydraulic city: Water and the infrastructures of citizenship in Mumbai. Duke University Press.

- Aquino, Albert P., Deriquito, Jamaica Angelica P., & Festejo, Meliza A. (2013). Ecological solid waste management act: Environmental protection through proper solid waste practice. Retrieved August 22. http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/files/ap_policy/153/153_1.pdf.

- Asis, Maruja M. B. (2006). Living with migration: Experiences of left-behind children in the Philippines. Asian Population Studies, 2(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730600700556

- Bakker, Karen. (2013). Constructing “public” water: The world bank, urban water supply, and the biopolitics of development. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31(2), 280–300. https://doi.org/10.1068/d5111

- Bankoff, Greg. (2003). Constructing vulnerability: The historical, natural and social generation of flooding in metropolitan Manila. Disasters, 27(3), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7717.00230

- Batubara, Bosman, Kooy, Michelle, & Zwarteveen, Margreet. (2018). Uneven urbanisation: Connecting flows of water to flows of labour and capital through Jakarta's flood infrastructure. Antipode, 50(5), 1186–1205. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12401

- Bernardo, Eileen C. (2008). Solid-Waste management practices of households in Manila, Philippines. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1140(1), 420–424. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1454.016

- Bharti, Ajay R., Nally, Jarlath E., Ricaldi, Jessica N., Matthias, Michael A., Diaz, Monica M., Lovett, Michael A., Levett, Paul N., Gilman, Robert H., Willig, Michael R., Gotuzo, Eduardo, & Vinetz, Joseph M. (2003). Leptospirosis: A zoonotic disease of global importance. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 3(12), 757–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00830-2

- Bicksler, Rebecca. (2019). The role of heritage conservation in disaster mitigation: A conceptual framework for connecting heritage and flood management in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Urban Geography, 40(2), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1534568

- Blue, Stanley. (2017). Institutional rhythms: Combining practice theory and rhythmanalysis to conceptualise processes of institutionalisation. Time & Society, 28(3), 922–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X17702165

- Carse, Ashley. (2012). Nature as infrastructure: Making and managing the Panama Canal watershed. Social Studies of Science, 42(4), 539–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312712440166

- Choi, Narae. (2016). Metro Manila through the gentrification lens: Disparities in urban planning and displacement risks. Urban Studies, 53(3), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014543032

- City Government of Makati City. (2013). Profile of Makati City. Makati City. http://www.makati.gov.ph/portal/main/index.jsp?main = 2&content = 0&menu = 0.

- Clapano, Jose Rodel. (2016). Manila: No more trikes, pedicabs next month, The Philippine Star, 18 September 2016. Retrieved 7 January, 2022, from https://www.philstar.com/metro/2016/09/18/1624916/manila-no-more-trikes-pedicabs-next-month.

- Cousins, Joshua J. (2017). Of floods and droughts: The uneven politics of stormwater in Los Angeles. Political Geography, 60(September), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.04.002

- Cousins, Joshua J., & Newell, Joshua P. (2015). A political–industrial ecology of water supply infrastructure for Los Angeles. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 58(January), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.10.011

- Cresswell, Tim. (2010). Towards a politics of mobility. Environment and Planning D, 28(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1068/d11407

- Delfin, Francisco G., & Gaillard, Jean-Christophe. (2008). Extreme versus quotidian: Addressing temporal dichotomies in Philippine disaster management. Public Administration and Development, 28(3), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.493

- Di Baldassarre, G., Viglione, A., Carr, G., Kuil, L., Salinas, J. L., & Blöschl, G. (2013). Socio-Hydrology: Conceptualising human-flood interactions. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 17(8), 3295–3303. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-3295-2013

- Dunn, G., Brown, R. R., Bos, J. J., & Bakker, K. (2016). Standing on the shoulders of giants: Understanding changes in urban water practice through the lens of complexity science. Urban Water Journal, 14, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/1573062X.2016.1241284

- Edensor, Tim. (2010). Fascinatin’ rhythm(s): polyrhythmia and the syncopated echoes of the everyday’. In Tim Edensor (Ed.), Geographies of rhythm: Nature, place, mobilities and bodies (pp. 83–94). Routledge.

- Ekers, Michael, & Loftus, Alex. (2008). The power of water: Developing dialogues between Foucault and Gramsci. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26(4), 698–718. https://doi.org/10.1068/d5907

- Gandy, Matthew. (2004). Rethinking urban metabolism: Water, space and the modern city. City, 8(3), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360481042000313509

- Gandy, Matthew. (2008). Landscapes of disaster: Water, modernity, and urban fragmentation in Mumbai. Environment and Planning A, 40(1), 108–130. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3994

- Gibert-Flutre, Marie. (2021). Rhythmanalysis: Rethinking the politics of everyday negotiations in ordinary public spaces. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 40(1), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544211020014

- Jha, Abhas K., Bloch, Robin, & Lamond, Jessica. (2012). Cities and flooding: A guide to integrated urban flood risk management for the 21st century. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8866-2.

- Krause, Franz. (2013). Managing floods, managing people: A political ecology of watercourse regulation on the Kemijoki. Nordia Geographical Publications, 41(5), 57–68.

- Krause, Franz. (2016). “One man’s flood defense Is another man’s flood”: relating through water flows in Gloucestershire, England’. Society & Natural Resources, 29(6), 681–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1107787

- Krause, Franz, & Strang, Veronica. (2016). Thinking relationships through water. Society & Natural Resources, 29(6), 633–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2016.1151714

- Lagmay, Alfredo Mahar, Mendoza, Jerico, Cipriano, Fatima, Delmendo, Patricia Anne, Lacsamana, Micah Nieves, Moises, Marc Anthony, Pellejera, Nicanor, Punay, Kenneth Niño, Sabio, Glenn, Santos, Laurize, Serrano, Jonathan, Taniza, Herbert James, & Tingin, Neil Eneri. (2017). Street floods in metro Manila and possible solutions. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 59, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2017.03.004

- Lefebvre, Henri. (2004). Rhythmanalysis: Space, time and everyday life. Continuum.

- Linton, Jamie, & Budds, Jessica. (2014). The hydrosocial cycle: Defining and mobilizing a relational-dialectical approach to water. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 57(November), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.10.008

- McFarlane, Colin, & Silver, Jonathan. (2017). Navigating the city: Dialectics of everyday urbanism. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42(3), 458–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12175

- Meerow, Sara. (2017). Double exposure, infrastructure planning, and urban climate resilience in coastal megacities: A case study of Manila. Environment and Planning A, 49(11), 2649–2672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17723630

- Misra, Kajri. (2014). From formal/informal to emergent formalization: Fluidities in the production of urban waterworlds. Water Alternatives, 7(1), http://search.proquest.com/openview/f9af7e37303f88d29926cfebf2afa550/1?pq-origsite = gscholar&cbl = 1136336.

- Monstadt, Jochen, & Coutard, Olivier. (2019). Cities in an Era of interfacing infrastructures: Politics and spatialities of the Urban Nexus. Urban Studies, 56(11), 2191–2206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019833907

- Mustafa, Daanish. (1998). Structural causes of vulnerability to flood hazard in Pakistan. Economic Geography, 74(3), 289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.1998.tb00117.x

- National Statistics Office of the Philippines. (2010). National Capital Region 2010 Census. http://ncr.popcom.gov.ph/index.php/2015-05-27-06-51-09.

- Neves Alves, Susana. (2021). Everyday states and water infrastructure: Insights from a small secondary city in Africa, Bafatá in Guinea-Bissau. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 39(2), 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654419875748

- Nüsser, Marcus, & Baghel, Ravi. (2017). 20. The emergence of technological hydroscapes in the Anthropocene: Socio-hydrology and development paradigms of large dams. In Handbook on geographies of technology (pp. 287–301).

- Parkes, Don, & Thrift, Nigel. (1979). Time spacemakers and entrainment. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 4(3), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.2307/622056

- Peterson, Jean Treloggen. (1993). Generalized extended family exchange: A case from the Philippines. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55(3), 570–584. https://doi.org/10.2307/353339

- Plyushteva, A., & Schwanen, T. (2018). Care-related journeys over the life-course: Thinking mobility biographies with gender, care and the household. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 97, 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.10.025

- Pregnolato, Maria, Ford, Alistair, Wilkinson, Sean M., & Dawson, Richard J. (2017). The impact of flooding on road transport: A depth-disruption function. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 55(August), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.06.020

- Ranganathan, M. (2015). Storm drains as assemblages: The political ecology of flood risk in post-colonial Bangalore. Antipode, 47(5), 1300–1320.

- Ranganathan, Malini, & Balazs, Carolina. (2015). Water marginalization at the urban fringe: Environmental justice and urban political ecology across the north–south divide. Urban Geography, 36(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1005414

- Reid-Musson, Emily. (2018). Intersectional rhythmanalysis: Power, rhythm, and everyday life. Progress in Human Geography, 42(6), 881–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517725069

- Rodolfo, Kelvin S., & Siringan, Fernando P. (2006). Global sea-level rise Is recognised, but flooding from anthropogenic land subsidence Is ignored around Northern Manila Bay, Philippines. Disasters, 30(1), 118–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2006.00310.x

- Ross, Alexander, & Chang, Heejun. (2020). Socio-hydrology with hydrosocial theory: Two sides of the same coin? Hydrological Sciences Journal, 65(9), 1443–1457. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2020.1761023

- Roy, Ananya. (2011). Slumdog cities: Rethinking subaltern urbanism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35(2), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01051.x

- Schwanen, Tim, & Nixon, Denver V. (2019). Urban infrastructures: Four tensions and their effects. In Tim Schwanen, & Ronald van Kempen (Eds.), Handbook of urban geography (pp. 147–162). Edward Elgar.

- Schwanen, Tim, van Aalst, Irina, Brands, Jelle, & Timan, Tjerk. (2012). Rhythms of the night: Spatiotemporal inequalities in the nighttime economy. Environment and Planning A, 44(9), 2064–2085. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44494

- Sultana, Farhana. (2010). Living in hazardous waterscapes: Gendered vulnerabilities and experiences of floods and disasters. Environmental Hazards, 9(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.3763/ehaz.2010.SI02

- Thompson, Mark R. (2016). Introduction: The early duterte presidency in the Philippines. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 35(3), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341603500301

- Trovalla, Eric, & Trovalla, Ulrika. (2015). Infrastructure as a divination tool: Whispers from the grids in a Nigerian city. City, 19(2–3), 332–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1018061

- Walker, Gordon, Whittle, Rebecca, Medd, Will, & Walker, Marion. (2011). Assembling the flood: Producing spaces of bad water in the city of Hull. Environment and Planning A, 43(10), 2304–2320. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43253

- Wesselink, Anna, Kooy, Michelle, & Warner, Jeroen. (2017). Socio-hydrology and hydrosocial analysis: Toward dialogues across disciplines. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 4(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1196

- Wilby, R. L. (2007). A review of climate change impacts on the built environment. Built Environment, 33(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.33.1.31

- Zoleta-Nantes, Doracie B. (2002). Differential impacts of flood hazards among the street children, the urban poor and residents of wealthy neighborhoods in Metro Manila, Philippines. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 7(3), 239–266. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024471412686

- Zoleta-Nantes, Doracie B. (2007). Flood hazards in metro Manila: Recognizing commonalities, differences, and courses of action. Social Science Diliman, 1(1), http://www.journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/socialsciencediliman/article/viewArticle/36.