ABSTRACT

In response to narratives of the mass movement of people triggered by climate change, a number of “managed retreat” models have been proposed as policy options, especially for densely populated urban areas in the Global South. Reviewing a case study from Mongla, a secondary city in southwestern Bangladesh, we argue that a “crisis narrative” unhelpfully informs current discourses of “climate migration”, and oversimplify complex realities, creating the risk that urban policy makers design managed retreat interventions that are poorly informed and maladaptive in that they may be accepted too uncritically, take overly technical forms, and may exacerbate rather than reduce the risk faced by those they are purportedly intended to assist.

Introduction

Climate change is increasingly predicted to trigger millions of people to move away from their homes (Clement et al., Citation2021), threatening a future of humanitarian crises, political violence, and strife (Lustgarten, Citation2020). The “managed retreat” of those most at risk of displacement is often proposed as a policy response, especially for densely populated urban areas in the Global South where services and infrastructure are already overstretched. We argue that such models of “managed retreat” are overly technical, carry significant risk for those they are purportedly intended to assist, and are accepted too uncritically. Drawing on the concept of the “crisis narrative” and associated insights from the anthropology of policy (Lewis, Citation2010), this paper critically examines a specific form of managed retreat: the relocation model of the “migrant-friendly climate resilient city” proposed by Khan et al. (Citation2021). Our intervention draws on recent field research in Mongla, a key secondary city in Bangladesh, where the model is being piloted.

Climate migration and managed retreat

The issue of “climate migration” is now a core feature of the urban agenda, prompting ideas and action by urban policy makers to address regarding the “human cost of forced and unmanaged migration created by the climate emergency” (Khan & Islam, Citation2021). The Mayors’ Migration Council and the C40 Initiative launched a Task Force on Climate and Migration in 2021 with a mandate of “accelerating local, national and international responses to the challenges of climate and migration” (Khan & Islam, Citation2021).

Accordingly, “managed retreat”, the purposeful relocation of people, infrastructure, homes, and businesses from hazard-prone areas and their resettlement to relatively safer locations, is increasingly discussed as a means of averting mass displacements and reducing vulnerability (Ajibade et al., Citation2022; Hino et al., Citation2017).

Several managed retreat and relocation models have emerged, including planning destination regions to be migrant-friendly (Khan et al., Citation2021), large-scale relocations, making space for retention ponds, designing floating cities (Mach & Siders, Citation2021), and voluntary buyout of vulnerable properties (Mach et al., Citation2019). In the US, for example, the resettlement of Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana is the first federally funded, comprehensive grant for a climate-driven voluntary community resettlement. It has aimed to proceed with high levels of community engagement to define the shape of the relocation (Simms et al., Citation2021).

The idea of climate driven managed retreat is relatively new and there are few empirical data available. However, as noted in a recent study of climate adaptation and mitigation initiatives in C40 cities, there is evidence that most of these initiatives focus on infrastructure and technology, with only a few engaging in more socially transformational measures (Heikkinen et al., Citation2019). In presenting a case study of Mongla, we draw attention both to the speculative nature of the climate migration discourse and to the role of crisis in providing the rationale for designing measures such as managed retreat.

Crisis narratives

While the urbanisation of climate migration discourse is a welcome development, we argue that the crisis narrative that informs it is problematic. A crisis narrative implies an urgent demand for action, serving to justify immediate decision making in the face of a looming danger. In contexts of an uncertain futures, such narratives serve to stabilise policy-making processes, renew the authority of policymakers, and foster decisive solutions to unpredictable events. However, a key problem with crisis narratives is that they tend to come at the expense of complexity (Roe, Citation1995).

Labeling a situation as a “crisis” helps focus attention and mobilises resources, but it also risks sidelining alternative ideas and responses, as crisis narratives are often constructed by powerful policy actors to advance particular interests (Jessop, Citation2018; Kuhl, Citation2021; Meagher, Citation2022). There are three inter-related effects. First, crisis narratives oversimplify, allowing policymakers to rely on solutions that are more sellable to their various constituencies. For example, they have informed the ways that colonial regimes deployed neo-Malthusian discourse to portray local production practices as “unsustainable” (Hartmann, Citation2010). They remain central to today’s portrayal of island nations as being in crisis and requiring evacuation, rendering local counter-discourses and contestation less visible (Koslov, Citation2016). Second, they foster ahistorical thinking by focusing on the present as a basis for action, rather than on understanding the past as a source of useable lessons. This contributes to “policy amnesia”, where decision makers downplay the past in order to justify and expedite immediate policy preferences (Lewis, Citation2010). Third, crisis narratives tend to reinforce calls for immediate solutions that are predominantly “technical” in nature, rather than ones informed by political or contextual factors, in line with anthropologist James Ferguson’s idea of the “anti-politics machine” (Ferguson, Citation1994).

These factors combine to produce other effects. For example, in the context of global climate migration, crisis narratives may fuel racist, nationalist agendas and shape xenophobic policy responses (Baldwin, Citation2022; Chaturvedi & Doyle, Citation2015). And by obfuscating policy and management failures of the past, they may render precarious the very people the proposed policies are now claiming to assist (Baldwin, Citation2022). In the context of managed urban retreat, a crisis narrative is produced at several levels. The climate policy world – for example in the form of the IPCC and the Mayors Migration Council – reinforces such narratives, through for example the latter’s alarmist prediction that the population in Freetown is expected to double in ten years “due in great part to climate migration from across Sierra Leone” or claims that “an estimated 2,000 people arrive in Dhaka daily, having migrated from other cities along a coastline that is increasingly affected by storms and rising sea levels” (MMC, Citation2021).

The media has also played a part in feeding the crisis narrative around “climate refugees”. For example, The Guardian newspaper recently described Bangladesh as an “internal migration pressure cooker”, while underplaying the multicausal reasons for migration among those living in rural areas (Ahmed & Choat, Citation2022). The New York Times has used the ominous headline “the great climate migration”, suggesting that “people are already beginning to flee” (Lustgarten, Citation2020). These constructed narratives of crisis oversimplify, contributing to a policy climate in which decision makers are drawn to rapid, short-term technical and managerial solutions that pay insufficient attention to local participation, social justice and rights. Each of these factors helps to explain the global rise of techno-managerial retreat programs.

There is a long history in Bangladesh of powerful policy actors deploying crisis narratives in the context of environmental resource management and flood control interventions to advance their own institutional and political agendas by pushing infrastructural solutions (Lewis, Citation2010). One consequence of this has been the emergence of forms of “climate reductionism” (Hulme, Citation2011) in which development activities are increasingly framed around donor climate policies (Dewan, Citation2023). This reductionism is particularly visible within contemporary discourses of “climate migration”, where it is unhelpfully implied that climate change is causing people to break with past behaviors, instead of recognizing important continuities within local adaptations that build on and intensify existing livelihood strategies. In short, the crisis narrative obscures the fact that, in a country like Bangladesh with its age-old unstable yet dynamic ecological systems and fragile livelihoods, people have long undertaken forms of short- or long-term relocation (Lewis, Citation2010; Paprocki, Citation2021).

Mongla as a “migrant-friendly” city

The “climate resilient migrant-friendly” city model is based on the idea of transforming urban areas through the “building of resilient hardware, such as low-cost housing, industries for employment generation, and other infrastructure; software, such as legal, policy, and institutional frameworks; and “heart-ware” – the promotion of awareness, reflecting values and ethics” (Khan et al., Citation2021, p. 1291). Attracting migrants to secondary cities is key, since these usually-ignored locations are now seen as uniquely positioned to pilot new approaches that can facilitate “safe and orderly movement for migrants ensuring employment, social protection, access to education, housing, health services, utilities etc.” (Khan et al., Citation2021, p. 1,291). Not only is the “climate resilient, migration-friendly cities” model said to be beneficial for migrants, it also promises to alleviate pressures on space and infrastructure in primary cities (Khan et al., Citation2021). Such a narrative also reframes the discourse on climate migration as a national/domestic problem, as opposed to a transnational one, and therefore a problem governable within national policy regimes.

Mongla, a secondary port city in Southwestern Bangladesh, has recently gained media attention as a migrant-friendly, climate-resilient city and as a relocation success story (Ahmed & Choat, Citation2022; Davison, Citation2022; Jazeera, Citation2022). Hidden behind Dhaka and Chittagong, Mongla, like many secondary cities around the world, had until recently received little policy and academic attention either within the country or externally (Ruszczyk et al., Citation2023).

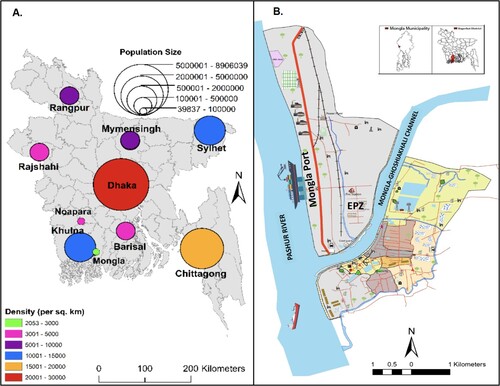

Mongla was selected as a pilot both because it is significantly exposed to climatic impacts (including cyclones and storm surges, sea-level rise and salinity intrusion), and because it carries the prospect of achieving economic growth driven by the recently-opened Padma bridge that connects it with the capital, Dhaka. As a “gateway” to the nearby Sundarbans mangrove forest, Mongla is an emerging symbol of the potential role of secondary cities to offer respite to mega-cities in coping with climate crises, and thus neatly feeds into international narratives on climate migration ().

Figure 1. Mongla population size and density in relation to other selected cities in Bangladesh (Panel A) and map of Mongla port municipality (Panel B). Source: Juel Mahmud, International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD). Map of Mongla created by ICCCAD (used with permission).

The Mongla case is interesting in itself, but it also potentially has wider relevance. If the pilot is judged successful, there are future plans for further secondary cities in Bangladesh to follow its trajectory toward climate resilient migrant-friendly status (Ahmed & Choat, Citation2022; Khan et al., Citation2021). It is also likely to be generalizable given the growing global emphasis on the potential role of secondary cities to stem outward migration flows from rural and coastal areas (UN-Habitat, Citation2022). Even more importantly it could serve as a bellwether of the tensions that cities around the world will face if managed retreat interventions are not sufficiently scrutinised in relation to other contexts.

Mongla’s experience demonstrates how investments in protective infrastructure that address climatic vulnerabilities can enable significant economic growth and transform urban lives. Since 2010, infrastructural transformation has been a priority of both the central and local government. Mongla is now a booming secondary city, home to the second largest seaport in Bangladesh and an export processing zone (EPZ), both of which bring significant employment.

However, the case also raises critical questions. The city’s economic transformation is creating winners and losers among different groups. For example, due to saline intrusion, many residents lack adequate supplies of fresh water. The challenge of meeting soaring demand for water, especially in informal settlements, goes unmentioned in narratives of Mongla’s “success”, as do questions of environmental compliance in the EPZ or the port, or how planned industrial development will affect the mangrove ecosystem. An essentially “techno-optimist” account of transformational adaptation emphasises only infrastructural improvements, job opportunities, and improved public services.

Techn-managerialist versus sustainable approaches

Khan et al. (Citation2021) propose that plans for migrant-friendly cities need to pay attention to the multiple components of hardware, software and “heartware”. However, in line with our argument that crisis narratives oversimply, the presentation of Mongla’s apparent success focuses mainly on hard infrastructure and employment generation. A historical perspective on previous large-scale interventions, such as that illustrated by James Scott’s analysis of “grand plans” (Scott, Citation1999), shows how these have tended to favor those with authority and power, and reproduced existing order and hierarchy. They failed largely because they were unable to account for the mundane relations of human societies, or the complexities of natural systems.

Mongla port’s ongoing large-scale dredging operation in the Pashur river and Mongla-Ghoshiakhali channel, designed to keep the port operational and employment opportunities open, aptly illustrates this point. Driven by specialised experts, and relying primarily on a techno-managerial logic, dredging both contributes to, and diverts attention from, social and environmental challenges. For local communities, the dumping of dredged sand and sediment destroys valuable arable land, damages biodiverse habitats, and weakens the livelihoods of marginal and small farmers. Located downstream of a massive, continental river system, both rivers carry heavy sediment loads, the disruption of which has potentially important implications for agricultural sustainability. In the face of crisis narratives, however, there is a strong incentive for government and other actors to ignore these challenges in favor of simplistic stories of success offered by these kinds of “solutions”.

Despite a legacy of inequitable infrastructure services, Mongla’s physical transformation is promoted as a successful response to the adaptation challenge. For example, construction of ponds which rely on rainwater and associated filtration systems are identified as possible solutions to the water crisis, but these water circulation systems favor established groups, and do little to improve access for disadvantaged communities. In and around Mongla, land prices have skyrocketed, rendering housing increasingly unaffordable, driving future and current migrants into informal settlements. These pressures are leading to the filling in of ponds, further worsening access to fresh water () and creating forms of exclusion best described as “infrastructural violence” (Rodgers & O’Neill, Citation2012). Narratives that declare Mongla as a successful “migrant-friendly city” therefore not only oversimplify but also obscure complex systemic problems.

Figure 2. A pond in Mongla recently filled with dredged sand. Source: Photograph taken by M. Feisal Rahman.

The crisis narrative framing of the “climate refugee” idea therefore obscures the multicausality of household migration decisions, and downplays the complex, systemic nature of livelihoods and resources in Mongla. For example, while dredging has positive implications for keeping the port functional, it also is adversely affecting agriculture-based livelihoods in adjacent areas and may paradoxically drive more migrants to head for Dhaka. As we have argued, crisis narratives ultimately inform and enable forms of “climate reductionism” that tend to favor infrastructural over social interventions (Dewan, Citation2023). This creates potential risks that need to be understood and managed by those advocating managed retreat policies, as our brief case study of Mongla has highlighted.

Conclusion: centering livelihoods and social justice

Critical urban scholarship tells us that responding to climate change is a fundamentally political project (Luque-Ayala et al., Citation2018). There is no reason to suppose that climate relocation policies are any different. Outcomes will reflect the interests of those with more resources and power (Ajibade et al., Citation2022). The brief examples and argument presented here suggest that the design and implementation of equitable retreat policies will require a paradigm shift, away from cost–benefit and efficiency metrics toward ones better informed by values, ethics and social justice that put community livelihoods, human dignity, wellbeing and democratic accountability at the center (Ajibade et al., Citation2022). Holding particular interests accountable can act as a safeguard against the use of crisis narratives to centralise or consolidate existing forms of dominance and social hierarchy.

As the crisis narrative around climate migration gains increasing traction on the urban agenda, city managers will be more attracted by managed retreat policy options. Take, for example, the recent co-authored article by Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London and Mohammad Atiqul Islam, Mayor of Dhaka City North, who state “as chair and vice chair of C40 Cities, a global network of mayors of nearly 100 world-leading cities dedicated to combating the climate crisis, we are taking urgent action to address the causes and devastating human cost of forced and unmanaged migration created by the climate emergency” (Khan & Islam, Citation2021).

By identifying the risks associated with crisis narratives we do not mean to suggest that they are the only drivers of current managed urban retreat initiatives, but that they play a role in oversimplifying complex realities. Urban policy makers will therefore need an informed understanding of both the causes of climate migration and the effects of managed retreat if we are to avoid the kinds of problems that we describe as part of the Mongla case.

Mongla’s ongoing transformation suggests that while improvements to physical infrastructure have an important role to play in reducing risk and enhancing climate resilience, this should not be at the expense of promoting equity, reducing vulnerability, and ensuring environmental sustainability. Inclusive retreat policies will require us to pay closer attention to citizen participation, local decision making, and the importance of local organizations in facilitating community-led processes. While a recent community needs assessment study in Mongla noted a preponderance of a narrow range of political party organizations (Ruszczyk et al., Citation2020), community-led approaches will also require the participation of civil society groups that are both diverse, locally representative and relatively autonomous.

In this regard, useful lessons could be drawn from the alternative bottom-up approach associated with Shack or Slum Dwellers International (SDI), with its practical collaboration strategy of “co-production”. Here a range of grassroots organizations and federations have successfully engaged with and influenced state institutions and government officials, making it possible “to identify new solutions that support local democratic practice as well as improved services” (Mitlin, Citation2008).

As climate-related migration, displacement, and relocation increasingly become part of urban policy agendas, we need to resist crisis narratives in favor of more complex, nuanced accounts that put local participants, social justice and environmental sustainability at the heart of policies for urban resilience and climate relocation futures. If the past is anything to go by, technocratic approaches to future prosperity will negatively impact vulnerable groups – informal settlers without land tenure, indigenous groups, and subsistence fishing and farming communities – who are less able to influence or resist. Unless their resilience and well-being are made part of planning for managed retreat, a double standard exists as to whose resilience really counts (Shi, Citation2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their encouraging and useful feedback on the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Saleemul Huq for his assistance with the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, K., & Choat, I. (2022). Port in a storm: The trailblazing town welcoming climate refugees in Bangladesh. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/jan/24/port-in-a-storm-the-trailblazing-town-welcoming-climate-refugees-in-bangladesh.

- Ajibade, I., Sullivan, M., Lower, C., Yarina, L., & Reilly, A. (2022). Are managed retreat programs successful and just? A global mapping of success typologies, justice dimensions, and trade-offs. Global Environmental Change, 76, Article 102576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102576

- Al Jazeera. (2022). Photos: The Bangladesh town offering new life to climate migrants. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2022/3/30/photos-bangladesh-town-offering-new-life-to-climate-migrants.

- Baldwin, W. A. (2022). Why we should abandon the concept of the ‘climate refugee’. The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/why-we-should-abandon-the-concept-of-the-climate-refugee-182920.

- Chaturvedi, S., & Doyle, T. (2015). Climate terror: A critical geopolitics of climate change. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Clement, V., Rigaud, K. K., de Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Adamo, S., Schewe, J., Sadiq, N., & Shabahat, E. (2021). Groundswell part 2: Acting on internal climate migration. World Bank. https://humantraffickingsearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Groundswell-Part-II.pdf.

- Davison, C. (2022). Migrant-friendly’ cities offer hope for climate refugees. DW. https://www.dw.com/en/bangladesh-migrant-friendly-cities-offer-hope-for-climate-refugees/a-62781441#:~:text = Bangladesh%3A%20'Migrant%2Dfriendly’,countries%20facing%20climate%2Dinduced%20migration.

- Dewan, C. (2023). Climate refugees or labour migrants? Climate reductive translations of women’s migration from coastal Bangladesh. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2023.2195555

- Ferguson, J. (1994). The anti-politics machine: “Development”, depoliticization, and bureaucratic power in Lesotho. University of Minnesota Press.

- Hartmann, B. (2010). Rethinking climate refugees and climate conflict: Rhetoric, reality and the politics of policy discourse. Journal of International Development, 22(2), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1676

- Heikkinen, M., Ylä-Anttila, T., & Juhola, S. (2019). Incremental, reformistic or transformational: What kind of change do C40 cities advocate to deal with climate change? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1473151

- Hino, M., Field, C. B., & Mach, K. J. (2017). Managed retreat as a response to natural hazard risk. Nature Climate Change, 7(5), 364–370. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3252

- Hulme, M. (2011). Reducing the future to climate: A story of climate determinism and reductionism. Osiris, 26(1), 245–266.

- Jessop, B. (2018). Valid construals and/or correct readings? On the symptomatology of crises. In Bob Jessop, & Karim Knio (Eds.), The pedagogy of economic, political and social crises (pp. 49–72). Routledge.

- Khan, M. R., Huq, S., Risha, A. N., & Alam, S. S. (2021). High-density population and displacement in Bangladesh. Science, 372(6548), 1290–1293. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi6364

- Khan, S., & Islam, M. A. (2021). World leaders must prepare for the climate migration challenge. The New Statesman. https://www.newstatesman.com/spotlight/regional-development/2021/12/world-leaders-must-prepare-for-the-climate-migration-challenge.

- Koslov, L. (2016). The case for retreat. Public Culture, 28(2), 359–387. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-3427487

- Kuhl, L. (2021). Policy making under scarcity: Reflections for designing socially just climate adaptation policy. One Earth, 4(2), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.01.008

- Lewis, D. (2010). The strength of weak ideas?: Human security, policy history, and climate change in Bangladesh. In J.-A. McNeish, & J. H. S. Lie (Eds.), Security and development (1st ed, pp. 113–129). Berghahn Books. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qd68h.10.

- Luque-Ayala, A., Bulkeley, H., & Marvin, S. (2018). Rethinking urban transitions: An analytical framework. In Andres Luque-Ayala, Simon Marvin, & Harriet Bulkeley (Eds.), Rethinking urban transitions (pp. 13–36). Routledge.

- Lustgarten, A. (2020). The great climate migration has begun. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/23/magazine/climate-migration.html

- Mach, K. J., Kraan, C. M., Hino, M., Siders, A. R., Johnston, E. M., & Field, C. B. (2019). Managed retreat through voluntary buyouts of flood-prone properties. Science Advances, 5(10), Article eaax8995. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax8995

- Mach, K. J., & Siders, A. R. (2021). Reframing strategic, managed retreat for transformative climate adaptation. Science, 372(6548), 1294–1299. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abh1894

- Mayors Migration Council (MMC). (2021). Global mayors action agenda on climate and migration. C40 Cities Leadership Group Mayors Migration Council. https://www.mayorsmigrationcouncil.org/c40-mmc-action-agenda.

- Meagher, K. (2022). Crisis narratives and the African paradox: African informal economies, COVID-19 and the decolonization of social policy. Development and Change, 53(6), 1200–1229. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12737

- Mitlin, D. (2008). With and beyond the state — co-production as a route to political influence, power and transformation for grassroots organizations. Environment and Urbanization, 20(2), 339–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247808096117

- Paprocki, K. (2021). Threatening dystopias: The global politics of climate change adaptation in Bangladesh. Cornell University Press.

- Rodgers, D., & O’Neill, B. (2012). Infrastructural violence: Introduction to the special issue. Ethnography, 13(4), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138111435738

- Roe, E. (1995). Except-Africa: Postscript to a special section on development narratives. World Development, 23(6), 1065–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00018-8

- Ruszczyk, H. A., Halligey, A., Rahman, M. F., & Ahmed, I. (2023). Liveability and vitality: An exploration of small cities in Bangladesh. Cities, 133, 104150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.104150

- Ruszczyk, H. A., Halligey, A., Rahman, M. F., Ahmed, I., Selim, S. B., Mity, M., Alam, S. S., Mahmud, J., Razzak, A., Azam, W. N., & Nowrin, J. (2020). Mongla dissemination brief, Liveable Regional Cities in Bangladesh Project. ICCCAD. https://www.icccad.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Mongla-Dissemination-Brief-June-2020.pdf.

- Scott, J. C. (1999). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press.

- Shi, L. (2020). The new climate urbanism: Old capitalism with climate characteristics. In Vanesa Castan Broto, Enora Robin, & Aidan While (Eds.), Climate urbanism (pp. 51–65). Springer.

- Simms, J. R., Waller, H. L., Brunet, C., & Jenkins, P. (2021). The long goodbye on a disappearing, ancestral island: A just retreat from isle de jean charles. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 11(3), 316–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-021-00682-5

- UN-Habitat. (2022). World cities report 2022: Envisaging the future of cities, United Nations human settlements program (UN-Habitat). Nairobi. https://unhabitat.org/wcr